User login

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

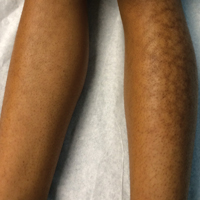

Reticular Hyperpigmentation on the Lower Legs

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

A 13-year-old otherwise healthy adolescent girl presented to the pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the legs. The patient noticed the rash 1 month prior to presentation. The rash initially involved the left shin and gradually spread to involve the shins bilaterally. The rash was asymptomatic with no pain, pruritus, or muscular asymmetry of the legs. She denied recent fevers, chills, or travel. The patient reported using a space heater daily that was directed at the legs, approximately 0.5 m away. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished adolescent girl in no acute distress with reticular hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities located on the left anterior shin and knee, with mild involvement of the right shin. The reticulated hyperpigmented areas were arranged in a rectangular distribution. Lower extremity musculoskeletal examination was symmetric.

Patch of Hair Loss on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

An 11-year-old girl presented for evaluation of a patch of hair loss on the right parietal scalp that had been present and stable for 2.5 years. Physical examination revealed a unilateral area of hair loss that was triangular in shape on the right parietal/temporal region, measuring 2.1×2.2 cm. Dermatoscope examination showed vellus hairs throughout. A hair-pull test was negative and the patient confirmed that the area had never been completely smooth. There were no associated symptoms and no family history of autoimmune disease or hair loss. Prior to presentation, the patient underwent a trial of intralesional steroids and topical steroids to the area without effect.