User login

Clinical decision support tools

It is difficult to imagine that practice guidelines, randomized controlled trials, evidence-based medicine, and similar tools of current practice did not exist a generation ago. We now have a rich repository of guidelines, and with the advent of electronic health records, they can be translated into patient care through the use of clinical decision support tools. The AGA understood the importance of its leadership in this area and organized development of such tools within its "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice." In this month’s Practice Management section, Dr Lawrence R. Kosinski, an expert in the field of clinical decision support, shares some of his insights into this segment of The Roadmap.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

"First we build the tools, then they build us"

Marshall McLuhan

Introduction

The field of Information Technology has become imbedded within the practice of medicine. As a result, aspects of our profession that traditionally have been the sole province of human intelligence are now performed by computers with greater precision and at a vastly greater scale and speed. Indeed, this process is already well under way. Every time you send an e-mail or connect a cell phone call, intelligent algorithms optimally route the information. They also automatically detect credit card fraud, fly and land airplanes, guide intelligent weapons systems, assemble products in robotic factories and play games such as chess, routinely defeating humans. We are building tremendous tools and they are now increasing what we can accomplish.

The rise in the use of health care information technology has also come at a very critical point for our profession as the rising cost of health care is no longer sustainable Those who are at risk for the payment of our services are no longer willing to bear it alone and are altering the structure of our health care system so as to transfer the financial risk on to us the providers. Accordingly, providers are going to be responsible for not only the provision of care but also for its quality and expense. To lower our cost and handle the risk of care, we as providers must fulfill the following objectives:

1. Assure that each health care professional is working up to the level of his/her licensure.

2. Facilitate the provision of care down to the lowest level professional capable of providing it.

3. Limit the scope of lower level professionals so that they are able to work at maximum levels.

4. Establish better system-wide communication so that this is all possible.

5. Report all outcomes data to external repositories and registries.

Electronic health records (EHRs) will be essential to accomplishing these objectives, but not without substantial change. The EHR of the future will not be the silo’d version we use today, but rather one whose user interface (UI) is tailored to the clinical experience and whose database is tied to a health information exchange (HIE) that is integrated with multiple outcomes registries.

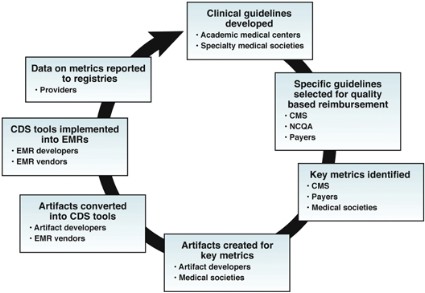

The UI will derive much of its strength and power from judicious use of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) tools: information technology artifacts that create a process for enhancing health-related decisions and actions with pertinent, organized clinical knowledge and patient information, to improve health and healthare delivery.

CDS tools

Most of us are very accustomed to decision support tools like GPS devices that tell us where we are and Internet search engines that help us make choices. CDS tools in health care are the same type of devices but they help us practice higher quality Medicine. We see them regularly as drug-drug Interactions, drug-allergy interactions and dose range checking. Those who have implemented EMRs are utilizing them for orders with standardized evidence-based ordersets and have implemented standardized system-based policies.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describe CDS tools as "health information technology functionality that builds upon the foundation of an EHR to provide persons involved in care processes with general and person-specific information, intelligently filtered and organized, at appropriate times, to enhance health and health care."

The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America makes recommendations for CDS tools. Their third recommendations states: "Accelerate integration of the best clinical knowledge into care decisions. Decision support tools and knowledge management systems should be routine features of health care delivery to ensure that decisions made by clinicians and patients are informed by current best evidence."

These IOM recommendations reflect the value of CDS tools as they: improve quality, maintain safety and decrease cost. Outcomes are also improved by CDS as they:

• Decrease errors of omission and commission.

• Reduce unnecessary, ineffective, or harmful care.

• Promote adherence to evidence-based care.

The Final Rule on Meaningful Use Stage 2 has also raised requirements for CDS tools. In Stage 1, eligible professionals needed only to implement one Clinical Decision Support (CDS) rule relevant to specialty or high clinical priority. In Stage 2, EPs will need to use CDS to:

• Improve performance on five high-priority health conditions.

• Support querying of immunization registries.

• Identify reportable conditions.

Clearly we all must embrace CDS tools.

Building a CDS program

Key elements of a successful CDS implementation include:

• Support for the program comes from all levels of the organization.

• Key stakeholders are involved.

• A clinically oriented champion must guide the effort.

• A multidisciplinary CDS committee.

• CDS goals aligned with organizational strategic goals.

• Ongoing monitoring .

The ultimate goal of a CDS program is to follow Osheroff’s CDS Fiver Rights, which seek to provide: the right information, to the right person, in the right format, through the right channel, at the right point in clinical workflow to improve health and healthcare decisions and outcomes. The ‘CDS Five Rights’ approach is also a framework for setting up and optimizing CDS interventions to address priority objectives.

CDS implementation problems and challenges

It can be challenging to implement an effective CDS program in a clinical practice. Commercially available tools imbedded in EMRs have unreliable alerts and insufficient application of usability standards. These are all inherent problems that limit our ability to create CDS tools that are effective and efficient. Small practices do not have the required personnel to create the templates and deploy them. Most clinical practices do not have sufficient staff to accomplish this.

It would be ideal if CDS tools were standardized and a repository of them existed from which a small practice could pull. Unfortunately, there is a lack of standardization and sharing between and among healthcare organizations with respect to CDS tools. Each of our EMRs is "proprietary" with a unique database that would require customized programming in order to implement a CDS tool. Clearly we need a better solution.

The AGA is proactively trying to lead the way in this endeavor by developing CDS tools and definitions for three clinical service lines (CSLs): colon cancer prevention, inflammatory bowel disease, and management of chronic hepatitis C. We are using or creating updated guidelines, deriving performance measures, and creating standard order sets and clinical management algorithms with grades of evidence for each decision point.

The future of CDS

Clearly CDS tools will mold and shape the practice of medicine in the future. We must succeed in standardizing the process and making the information uniformly available.

This will require the creation of cloud based CDS tools that are no longer proprietary to the EMR. In addition, the providers cannot do this alone. We will need to bring the patient into the process through the development of patient specific "hovering tools" designed to provide us with information about them on a real time basis.

Real CDS tools created by a private practice

The Illinois Gastroenterology Group (IGG) has recently developed a program we call "Project Sonar". It’s an initiative designed to improve our communication with our patients with IBD. We created a cloud based repository of CDS tools that are accessible from our EMR. These are queried by our EMR and provided to physicians and staff. Patients are sent queries on a real time basis that contain an abbreviated CDAI to assess their symptom quotient. These data are then fed into our database where we are developing artificial intelligence to determine the course of action based upon the level and the rate of change in the level.

The value of Project Sonar is that it is scalable to other practices, even using other EMRs. This is the ultimate structure that will move us toward success. There is just not enough band-with in most practices to create them in house.

Conclusion

If we are to succeed and thrive in a future system characterized by acceptance of risk for both outcomes and finances, we will need to efficiently deploy our practice assets and so that we are obtaining the most they can provide. We must increase our return on assets.

In order to minimize risk, we also need to embrace our patients in a way that brings them into the process. This will require the creation of information systems that are replete with CDS tools both for the provider as well as gamefied for the patient.

We are in our infancy in this process and much work is yet to be done. We must collaborate and share knowledge among us so that we retain control in the direction of the development of these tools. The AGA is striving to be a leader in this process.

Dr. Kosinski is managing partner of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Chairman AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Clinical Practice Counselor: AGA Governing Board – term to start in May. He has no conflicts of interest.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead"section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013:11:756-9).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.

It is difficult to imagine that practice guidelines, randomized controlled trials, evidence-based medicine, and similar tools of current practice did not exist a generation ago. We now have a rich repository of guidelines, and with the advent of electronic health records, they can be translated into patient care through the use of clinical decision support tools. The AGA understood the importance of its leadership in this area and organized development of such tools within its "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice." In this month’s Practice Management section, Dr Lawrence R. Kosinski, an expert in the field of clinical decision support, shares some of his insights into this segment of The Roadmap.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

"First we build the tools, then they build us"

Marshall McLuhan

Introduction

The field of Information Technology has become imbedded within the practice of medicine. As a result, aspects of our profession that traditionally have been the sole province of human intelligence are now performed by computers with greater precision and at a vastly greater scale and speed. Indeed, this process is already well under way. Every time you send an e-mail or connect a cell phone call, intelligent algorithms optimally route the information. They also automatically detect credit card fraud, fly and land airplanes, guide intelligent weapons systems, assemble products in robotic factories and play games such as chess, routinely defeating humans. We are building tremendous tools and they are now increasing what we can accomplish.

The rise in the use of health care information technology has also come at a very critical point for our profession as the rising cost of health care is no longer sustainable Those who are at risk for the payment of our services are no longer willing to bear it alone and are altering the structure of our health care system so as to transfer the financial risk on to us the providers. Accordingly, providers are going to be responsible for not only the provision of care but also for its quality and expense. To lower our cost and handle the risk of care, we as providers must fulfill the following objectives:

1. Assure that each health care professional is working up to the level of his/her licensure.

2. Facilitate the provision of care down to the lowest level professional capable of providing it.

3. Limit the scope of lower level professionals so that they are able to work at maximum levels.

4. Establish better system-wide communication so that this is all possible.

5. Report all outcomes data to external repositories and registries.

Electronic health records (EHRs) will be essential to accomplishing these objectives, but not without substantial change. The EHR of the future will not be the silo’d version we use today, but rather one whose user interface (UI) is tailored to the clinical experience and whose database is tied to a health information exchange (HIE) that is integrated with multiple outcomes registries.

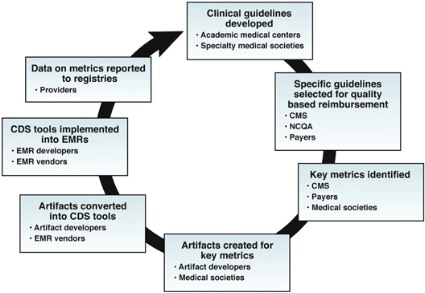

The UI will derive much of its strength and power from judicious use of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) tools: information technology artifacts that create a process for enhancing health-related decisions and actions with pertinent, organized clinical knowledge and patient information, to improve health and healthare delivery.

CDS tools

Most of us are very accustomed to decision support tools like GPS devices that tell us where we are and Internet search engines that help us make choices. CDS tools in health care are the same type of devices but they help us practice higher quality Medicine. We see them regularly as drug-drug Interactions, drug-allergy interactions and dose range checking. Those who have implemented EMRs are utilizing them for orders with standardized evidence-based ordersets and have implemented standardized system-based policies.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describe CDS tools as "health information technology functionality that builds upon the foundation of an EHR to provide persons involved in care processes with general and person-specific information, intelligently filtered and organized, at appropriate times, to enhance health and health care."

The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America makes recommendations for CDS tools. Their third recommendations states: "Accelerate integration of the best clinical knowledge into care decisions. Decision support tools and knowledge management systems should be routine features of health care delivery to ensure that decisions made by clinicians and patients are informed by current best evidence."

These IOM recommendations reflect the value of CDS tools as they: improve quality, maintain safety and decrease cost. Outcomes are also improved by CDS as they:

• Decrease errors of omission and commission.

• Reduce unnecessary, ineffective, or harmful care.

• Promote adherence to evidence-based care.

The Final Rule on Meaningful Use Stage 2 has also raised requirements for CDS tools. In Stage 1, eligible professionals needed only to implement one Clinical Decision Support (CDS) rule relevant to specialty or high clinical priority. In Stage 2, EPs will need to use CDS to:

• Improve performance on five high-priority health conditions.

• Support querying of immunization registries.

• Identify reportable conditions.

Clearly we all must embrace CDS tools.

Building a CDS program

Key elements of a successful CDS implementation include:

• Support for the program comes from all levels of the organization.

• Key stakeholders are involved.

• A clinically oriented champion must guide the effort.

• A multidisciplinary CDS committee.

• CDS goals aligned with organizational strategic goals.

• Ongoing monitoring .

The ultimate goal of a CDS program is to follow Osheroff’s CDS Fiver Rights, which seek to provide: the right information, to the right person, in the right format, through the right channel, at the right point in clinical workflow to improve health and healthcare decisions and outcomes. The ‘CDS Five Rights’ approach is also a framework for setting up and optimizing CDS interventions to address priority objectives.

CDS implementation problems and challenges

It can be challenging to implement an effective CDS program in a clinical practice. Commercially available tools imbedded in EMRs have unreliable alerts and insufficient application of usability standards. These are all inherent problems that limit our ability to create CDS tools that are effective and efficient. Small practices do not have the required personnel to create the templates and deploy them. Most clinical practices do not have sufficient staff to accomplish this.

It would be ideal if CDS tools were standardized and a repository of them existed from which a small practice could pull. Unfortunately, there is a lack of standardization and sharing between and among healthcare organizations with respect to CDS tools. Each of our EMRs is "proprietary" with a unique database that would require customized programming in order to implement a CDS tool. Clearly we need a better solution.

The AGA is proactively trying to lead the way in this endeavor by developing CDS tools and definitions for three clinical service lines (CSLs): colon cancer prevention, inflammatory bowel disease, and management of chronic hepatitis C. We are using or creating updated guidelines, deriving performance measures, and creating standard order sets and clinical management algorithms with grades of evidence for each decision point.

The future of CDS

Clearly CDS tools will mold and shape the practice of medicine in the future. We must succeed in standardizing the process and making the information uniformly available.

This will require the creation of cloud based CDS tools that are no longer proprietary to the EMR. In addition, the providers cannot do this alone. We will need to bring the patient into the process through the development of patient specific "hovering tools" designed to provide us with information about them on a real time basis.

Real CDS tools created by a private practice

The Illinois Gastroenterology Group (IGG) has recently developed a program we call "Project Sonar". It’s an initiative designed to improve our communication with our patients with IBD. We created a cloud based repository of CDS tools that are accessible from our EMR. These are queried by our EMR and provided to physicians and staff. Patients are sent queries on a real time basis that contain an abbreviated CDAI to assess their symptom quotient. These data are then fed into our database where we are developing artificial intelligence to determine the course of action based upon the level and the rate of change in the level.

The value of Project Sonar is that it is scalable to other practices, even using other EMRs. This is the ultimate structure that will move us toward success. There is just not enough band-with in most practices to create them in house.

Conclusion

If we are to succeed and thrive in a future system characterized by acceptance of risk for both outcomes and finances, we will need to efficiently deploy our practice assets and so that we are obtaining the most they can provide. We must increase our return on assets.

In order to minimize risk, we also need to embrace our patients in a way that brings them into the process. This will require the creation of information systems that are replete with CDS tools both for the provider as well as gamefied for the patient.

We are in our infancy in this process and much work is yet to be done. We must collaborate and share knowledge among us so that we retain control in the direction of the development of these tools. The AGA is striving to be a leader in this process.

Dr. Kosinski is managing partner of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Chairman AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Clinical Practice Counselor: AGA Governing Board – term to start in May. He has no conflicts of interest.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead"section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013:11:756-9).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.

It is difficult to imagine that practice guidelines, randomized controlled trials, evidence-based medicine, and similar tools of current practice did not exist a generation ago. We now have a rich repository of guidelines, and with the advent of electronic health records, they can be translated into patient care through the use of clinical decision support tools. The AGA understood the importance of its leadership in this area and organized development of such tools within its "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice." In this month’s Practice Management section, Dr Lawrence R. Kosinski, an expert in the field of clinical decision support, shares some of his insights into this segment of The Roadmap.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

"First we build the tools, then they build us"

Marshall McLuhan

Introduction

The field of Information Technology has become imbedded within the practice of medicine. As a result, aspects of our profession that traditionally have been the sole province of human intelligence are now performed by computers with greater precision and at a vastly greater scale and speed. Indeed, this process is already well under way. Every time you send an e-mail or connect a cell phone call, intelligent algorithms optimally route the information. They also automatically detect credit card fraud, fly and land airplanes, guide intelligent weapons systems, assemble products in robotic factories and play games such as chess, routinely defeating humans. We are building tremendous tools and they are now increasing what we can accomplish.

The rise in the use of health care information technology has also come at a very critical point for our profession as the rising cost of health care is no longer sustainable Those who are at risk for the payment of our services are no longer willing to bear it alone and are altering the structure of our health care system so as to transfer the financial risk on to us the providers. Accordingly, providers are going to be responsible for not only the provision of care but also for its quality and expense. To lower our cost and handle the risk of care, we as providers must fulfill the following objectives:

1. Assure that each health care professional is working up to the level of his/her licensure.

2. Facilitate the provision of care down to the lowest level professional capable of providing it.

3. Limit the scope of lower level professionals so that they are able to work at maximum levels.

4. Establish better system-wide communication so that this is all possible.

5. Report all outcomes data to external repositories and registries.

Electronic health records (EHRs) will be essential to accomplishing these objectives, but not without substantial change. The EHR of the future will not be the silo’d version we use today, but rather one whose user interface (UI) is tailored to the clinical experience and whose database is tied to a health information exchange (HIE) that is integrated with multiple outcomes registries.

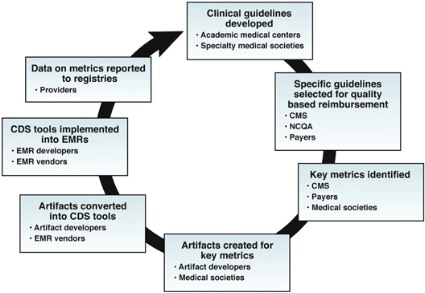

The UI will derive much of its strength and power from judicious use of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) tools: information technology artifacts that create a process for enhancing health-related decisions and actions with pertinent, organized clinical knowledge and patient information, to improve health and healthare delivery.

CDS tools

Most of us are very accustomed to decision support tools like GPS devices that tell us where we are and Internet search engines that help us make choices. CDS tools in health care are the same type of devices but they help us practice higher quality Medicine. We see them regularly as drug-drug Interactions, drug-allergy interactions and dose range checking. Those who have implemented EMRs are utilizing them for orders with standardized evidence-based ordersets and have implemented standardized system-based policies.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describe CDS tools as "health information technology functionality that builds upon the foundation of an EHR to provide persons involved in care processes with general and person-specific information, intelligently filtered and organized, at appropriate times, to enhance health and health care."

The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America makes recommendations for CDS tools. Their third recommendations states: "Accelerate integration of the best clinical knowledge into care decisions. Decision support tools and knowledge management systems should be routine features of health care delivery to ensure that decisions made by clinicians and patients are informed by current best evidence."

These IOM recommendations reflect the value of CDS tools as they: improve quality, maintain safety and decrease cost. Outcomes are also improved by CDS as they:

• Decrease errors of omission and commission.

• Reduce unnecessary, ineffective, or harmful care.

• Promote adherence to evidence-based care.

The Final Rule on Meaningful Use Stage 2 has also raised requirements for CDS tools. In Stage 1, eligible professionals needed only to implement one Clinical Decision Support (CDS) rule relevant to specialty or high clinical priority. In Stage 2, EPs will need to use CDS to:

• Improve performance on five high-priority health conditions.

• Support querying of immunization registries.

• Identify reportable conditions.

Clearly we all must embrace CDS tools.

Building a CDS program

Key elements of a successful CDS implementation include:

• Support for the program comes from all levels of the organization.

• Key stakeholders are involved.

• A clinically oriented champion must guide the effort.

• A multidisciplinary CDS committee.

• CDS goals aligned with organizational strategic goals.

• Ongoing monitoring .

The ultimate goal of a CDS program is to follow Osheroff’s CDS Fiver Rights, which seek to provide: the right information, to the right person, in the right format, through the right channel, at the right point in clinical workflow to improve health and healthcare decisions and outcomes. The ‘CDS Five Rights’ approach is also a framework for setting up and optimizing CDS interventions to address priority objectives.

CDS implementation problems and challenges

It can be challenging to implement an effective CDS program in a clinical practice. Commercially available tools imbedded in EMRs have unreliable alerts and insufficient application of usability standards. These are all inherent problems that limit our ability to create CDS tools that are effective and efficient. Small practices do not have the required personnel to create the templates and deploy them. Most clinical practices do not have sufficient staff to accomplish this.

It would be ideal if CDS tools were standardized and a repository of them existed from which a small practice could pull. Unfortunately, there is a lack of standardization and sharing between and among healthcare organizations with respect to CDS tools. Each of our EMRs is "proprietary" with a unique database that would require customized programming in order to implement a CDS tool. Clearly we need a better solution.

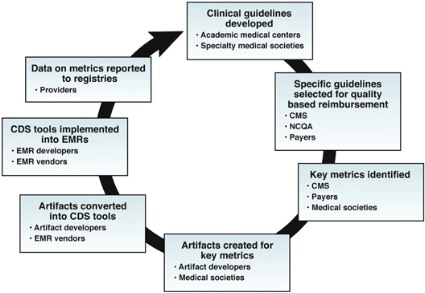

The AGA is proactively trying to lead the way in this endeavor by developing CDS tools and definitions for three clinical service lines (CSLs): colon cancer prevention, inflammatory bowel disease, and management of chronic hepatitis C. We are using or creating updated guidelines, deriving performance measures, and creating standard order sets and clinical management algorithms with grades of evidence for each decision point.

The future of CDS

Clearly CDS tools will mold and shape the practice of medicine in the future. We must succeed in standardizing the process and making the information uniformly available.

This will require the creation of cloud based CDS tools that are no longer proprietary to the EMR. In addition, the providers cannot do this alone. We will need to bring the patient into the process through the development of patient specific "hovering tools" designed to provide us with information about them on a real time basis.

Real CDS tools created by a private practice

The Illinois Gastroenterology Group (IGG) has recently developed a program we call "Project Sonar". It’s an initiative designed to improve our communication with our patients with IBD. We created a cloud based repository of CDS tools that are accessible from our EMR. These are queried by our EMR and provided to physicians and staff. Patients are sent queries on a real time basis that contain an abbreviated CDAI to assess their symptom quotient. These data are then fed into our database where we are developing artificial intelligence to determine the course of action based upon the level and the rate of change in the level.

The value of Project Sonar is that it is scalable to other practices, even using other EMRs. This is the ultimate structure that will move us toward success. There is just not enough band-with in most practices to create them in house.

Conclusion

If we are to succeed and thrive in a future system characterized by acceptance of risk for both outcomes and finances, we will need to efficiently deploy our practice assets and so that we are obtaining the most they can provide. We must increase our return on assets.

In order to minimize risk, we also need to embrace our patients in a way that brings them into the process. This will require the creation of information systems that are replete with CDS tools both for the provider as well as gamefied for the patient.

We are in our infancy in this process and much work is yet to be done. We must collaborate and share knowledge among us so that we retain control in the direction of the development of these tools. The AGA is striving to be a leader in this process.

Dr. Kosinski is managing partner of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, Chairman AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Clinical Practice Counselor: AGA Governing Board – term to start in May. He has no conflicts of interest.

Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead"section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2013:11:756-9).

"Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application: To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.