User login

The Dermatologist Nose Best: Correlation of Nose-Picking Habits and <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i>–Related Dermatologic Disease

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

Practice Points

- Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of approximately 20% to 80% of humans and can play a large factor in dermatologic disease.

- Staphylococcus aureus decolonization practices for at-risk dermatology patients may overlook the role that nose-picking plays.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation Following Treatment of Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans With Tazarotene Cream 0.1%

To the Editor:

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), or Flegel disease, is a rare keratinization disorder characterized by asymptomatic, red-brown, 1- to 5-mm papules with irregular horny scales commonly seen on the dorsal feet and lower legs.1 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is notorious for being difficult to treat. Various treatment options, including 5-fluorouracil, topical and oral retinoids, vitamin D3 derivatives, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and dermabrasion, have been explored but none have proven to be consistently effective.

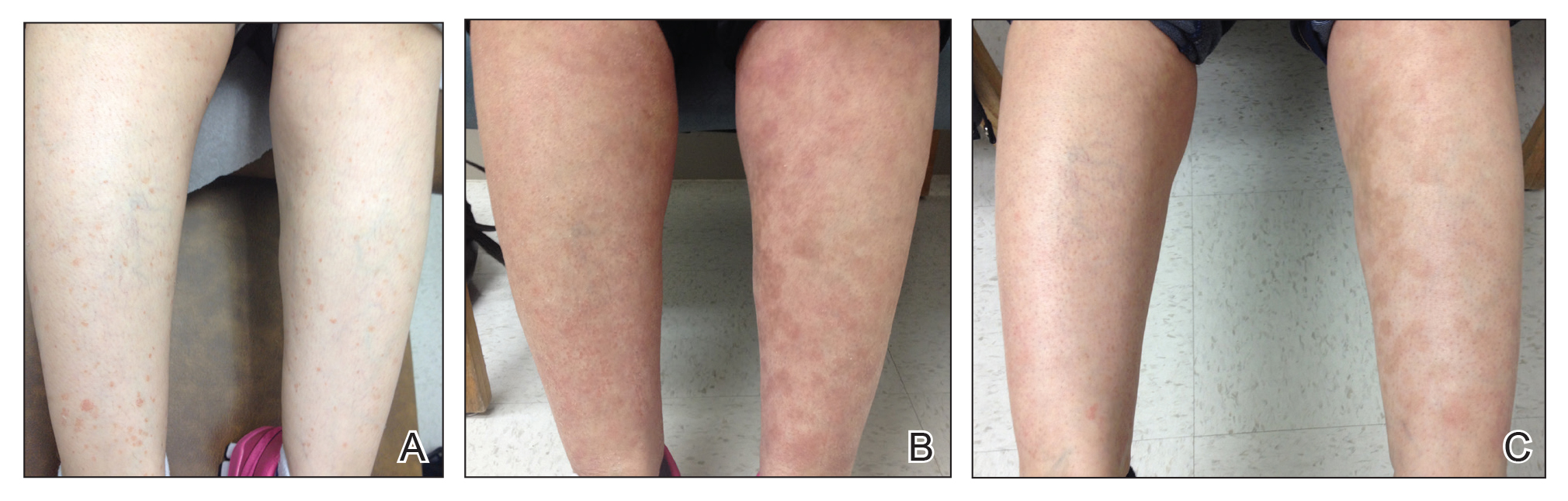

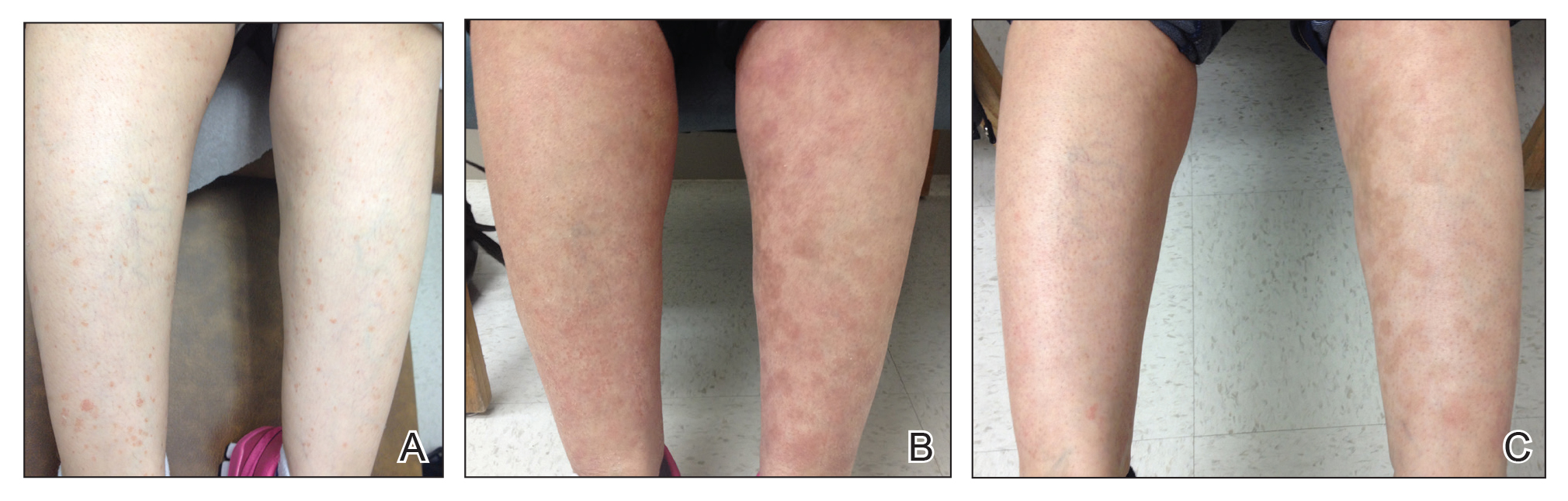

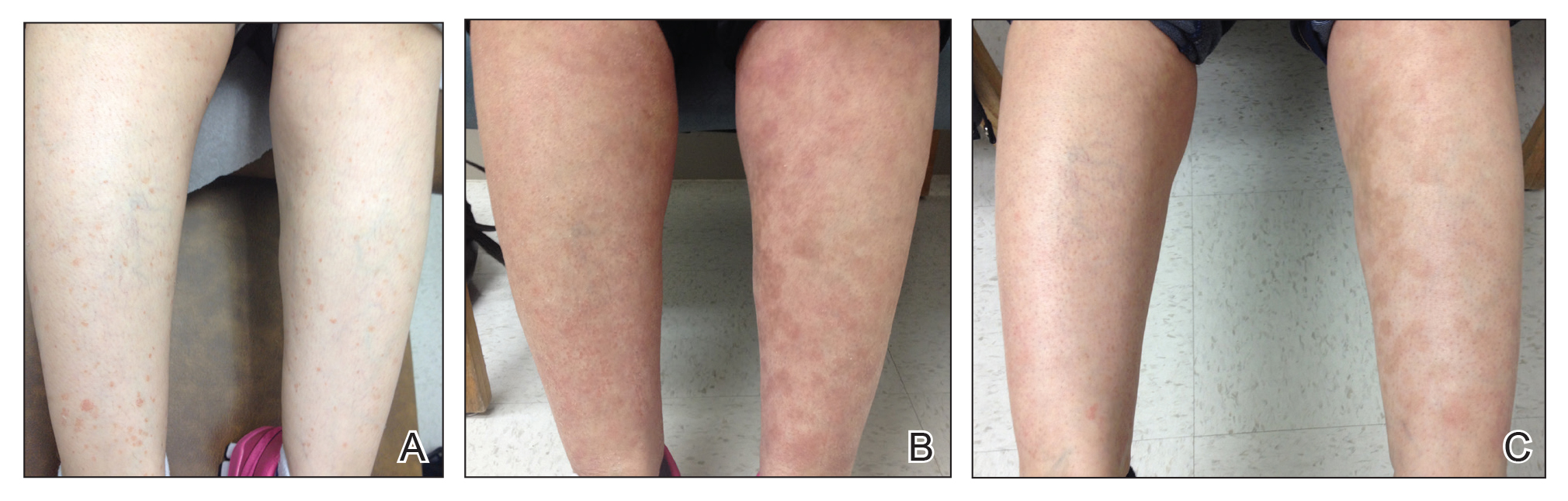

A woman in her 50s presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the legs and thighs that had been present for the last 20 years. She had been misdiagnosed by multiple outside providers with atopic dermatitis and was treated with topical steroids without considerable improvement. Upon initial presentation to our clinic , physical examination revealed a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II with multiple hyperpigmented, red-brown, 2- to 6-mm papules on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and upper thighs (Figure, A). A 3-mm punch biopsy of a lesion on the right upper thigh revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basal layer degeneration and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. The clinical and histopathologic findings were consistent with HLP.

The patient was started on treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream on the right leg and tazarotene cream 0.1% on the left leg to determine which agent would work best. After 9 weeks of treatment, slight improvement was observed on both legs, but the lesions were still erythematous (Figure, B). Treatment was continued, and after 14 weeks complete resolution of the lesions was noted on both legs; however, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) was observed on the left leg, which had been treated with tazarotene (Figure, C). The patient was lost to follow-up prior to treatment of the PIH.

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is an acquired excess of pigment due to a prior disease process such as an infection, allergic reaction, trauma, inflammatory disease, or drug reaction. In our patient, this finding was unusual because tazarotene has been shown to be an effective treatment of PIH.2,3

In PIH, there is either abnormal production or distribution of melanin pigment in the epidermis and/or dermis. Several mechanisms for PIH have been suggested. One potential mechanism is disruption of the basal cell layer due to dermal lymphocytic inflammation, causing melanin to be released and trapped by macrophages present in the dermal papillae. Another possible mechanism is epidermal hypermelanosis, in which the release and oxidation of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and leukotrienes alters immune cells and melanocytes, causing an increase in melanin and increased transfer of melanin to keratinocytes in the surrounding epidermis.4

Treatment of PIH can be a difficult and prolonged process, especially when a dermal rather than epidermal melanosis is observed. Topical retinoids, topical hydroquinone, azelaic acid, corticosteroids, tretinoin cream, glycolic acid, and trichloroacetic acid have been shown to be effective in treating epidermal PIH. Tazarotene is a synthetic retinoid that has been proven to be an effective treatment of PIH3; however, in our patient the PIH progressed with treatment. One plausible explanation is that irritation caused by the medication led to further PIH.2,5

It is uncommon for tazarotene to cause PIH. Hyperpigmentation is listed as an adverse effect observed during the postmarketing experience according to one manufacturer6 and the US Food and Drug Administration; however, details about prior incidents of hyperpigmentation have not been reported in the literature. Our case is unique because both treatments showed considerable improvement in HLP, but more PIH was observed on the tazarotene-treated leg.

- Bean SF. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. a clinical, histopathologic, and genetic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:705-709.

- Callender V, St. Surin-Lord S, Davis E, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- McEvoy G. Tazarotene (topical). In: AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc; 2014:84-92.

- Lacz N, Vafaie J, Kihiczak N, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a common but troubling condition. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:362-365.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) cream [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) gel [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

To the Editor:

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), or Flegel disease, is a rare keratinization disorder characterized by asymptomatic, red-brown, 1- to 5-mm papules with irregular horny scales commonly seen on the dorsal feet and lower legs.1 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is notorious for being difficult to treat. Various treatment options, including 5-fluorouracil, topical and oral retinoids, vitamin D3 derivatives, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and dermabrasion, have been explored but none have proven to be consistently effective.

A woman in her 50s presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the legs and thighs that had been present for the last 20 years. She had been misdiagnosed by multiple outside providers with atopic dermatitis and was treated with topical steroids without considerable improvement. Upon initial presentation to our clinic , physical examination revealed a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II with multiple hyperpigmented, red-brown, 2- to 6-mm papules on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and upper thighs (Figure, A). A 3-mm punch biopsy of a lesion on the right upper thigh revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basal layer degeneration and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. The clinical and histopathologic findings were consistent with HLP.

The patient was started on treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream on the right leg and tazarotene cream 0.1% on the left leg to determine which agent would work best. After 9 weeks of treatment, slight improvement was observed on both legs, but the lesions were still erythematous (Figure, B). Treatment was continued, and after 14 weeks complete resolution of the lesions was noted on both legs; however, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) was observed on the left leg, which had been treated with tazarotene (Figure, C). The patient was lost to follow-up prior to treatment of the PIH.

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is an acquired excess of pigment due to a prior disease process such as an infection, allergic reaction, trauma, inflammatory disease, or drug reaction. In our patient, this finding was unusual because tazarotene has been shown to be an effective treatment of PIH.2,3

In PIH, there is either abnormal production or distribution of melanin pigment in the epidermis and/or dermis. Several mechanisms for PIH have been suggested. One potential mechanism is disruption of the basal cell layer due to dermal lymphocytic inflammation, causing melanin to be released and trapped by macrophages present in the dermal papillae. Another possible mechanism is epidermal hypermelanosis, in which the release and oxidation of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and leukotrienes alters immune cells and melanocytes, causing an increase in melanin and increased transfer of melanin to keratinocytes in the surrounding epidermis.4

Treatment of PIH can be a difficult and prolonged process, especially when a dermal rather than epidermal melanosis is observed. Topical retinoids, topical hydroquinone, azelaic acid, corticosteroids, tretinoin cream, glycolic acid, and trichloroacetic acid have been shown to be effective in treating epidermal PIH. Tazarotene is a synthetic retinoid that has been proven to be an effective treatment of PIH3; however, in our patient the PIH progressed with treatment. One plausible explanation is that irritation caused by the medication led to further PIH.2,5

It is uncommon for tazarotene to cause PIH. Hyperpigmentation is listed as an adverse effect observed during the postmarketing experience according to one manufacturer6 and the US Food and Drug Administration; however, details about prior incidents of hyperpigmentation have not been reported in the literature. Our case is unique because both treatments showed considerable improvement in HLP, but more PIH was observed on the tazarotene-treated leg.

To the Editor:

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), or Flegel disease, is a rare keratinization disorder characterized by asymptomatic, red-brown, 1- to 5-mm papules with irregular horny scales commonly seen on the dorsal feet and lower legs.1 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is notorious for being difficult to treat. Various treatment options, including 5-fluorouracil, topical and oral retinoids, vitamin D3 derivatives, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and dermabrasion, have been explored but none have proven to be consistently effective.

A woman in her 50s presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the legs and thighs that had been present for the last 20 years. She had been misdiagnosed by multiple outside providers with atopic dermatitis and was treated with topical steroids without considerable improvement. Upon initial presentation to our clinic , physical examination revealed a woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II with multiple hyperpigmented, red-brown, 2- to 6-mm papules on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and upper thighs (Figure, A). A 3-mm punch biopsy of a lesion on the right upper thigh revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basal layer degeneration and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. The clinical and histopathologic findings were consistent with HLP.

The patient was started on treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream on the right leg and tazarotene cream 0.1% on the left leg to determine which agent would work best. After 9 weeks of treatment, slight improvement was observed on both legs, but the lesions were still erythematous (Figure, B). Treatment was continued, and after 14 weeks complete resolution of the lesions was noted on both legs; however, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) was observed on the left leg, which had been treated with tazarotene (Figure, C). The patient was lost to follow-up prior to treatment of the PIH.

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is an acquired excess of pigment due to a prior disease process such as an infection, allergic reaction, trauma, inflammatory disease, or drug reaction. In our patient, this finding was unusual because tazarotene has been shown to be an effective treatment of PIH.2,3

In PIH, there is either abnormal production or distribution of melanin pigment in the epidermis and/or dermis. Several mechanisms for PIH have been suggested. One potential mechanism is disruption of the basal cell layer due to dermal lymphocytic inflammation, causing melanin to be released and trapped by macrophages present in the dermal papillae. Another possible mechanism is epidermal hypermelanosis, in which the release and oxidation of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and leukotrienes alters immune cells and melanocytes, causing an increase in melanin and increased transfer of melanin to keratinocytes in the surrounding epidermis.4

Treatment of PIH can be a difficult and prolonged process, especially when a dermal rather than epidermal melanosis is observed. Topical retinoids, topical hydroquinone, azelaic acid, corticosteroids, tretinoin cream, glycolic acid, and trichloroacetic acid have been shown to be effective in treating epidermal PIH. Tazarotene is a synthetic retinoid that has been proven to be an effective treatment of PIH3; however, in our patient the PIH progressed with treatment. One plausible explanation is that irritation caused by the medication led to further PIH.2,5

It is uncommon for tazarotene to cause PIH. Hyperpigmentation is listed as an adverse effect observed during the postmarketing experience according to one manufacturer6 and the US Food and Drug Administration; however, details about prior incidents of hyperpigmentation have not been reported in the literature. Our case is unique because both treatments showed considerable improvement in HLP, but more PIH was observed on the tazarotene-treated leg.

- Bean SF. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. a clinical, histopathologic, and genetic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:705-709.

- Callender V, St. Surin-Lord S, Davis E, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- McEvoy G. Tazarotene (topical). In: AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc; 2014:84-92.

- Lacz N, Vafaie J, Kihiczak N, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a common but troubling condition. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:362-365.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) cream [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) gel [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Bean SF. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. a clinical, histopathologic, and genetic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:705-709.

- Callender V, St. Surin-Lord S, Davis E, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:87-99.

- McEvoy G. Tazarotene (topical). In: AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc; 2014:84-92.

- Lacz N, Vafaie J, Kihiczak N, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a common but troubling condition. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:362-365.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) cream [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2013.

- Tazorac (tazarotene) gel [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

Practice Points

- Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is a rare keratinization disorder that presents with asymptomatic red-brown papules with irregular horny scales on the lower extremities.

- Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Hematoxylin and eosin staining generally will show hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basal layer degeneration and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

- Tazarotene cream 0.1% is a synthetic retinoid sometimes used for treatment of hyperpigmentation, but it also can cause postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Basal Cell Carcinoma Masquerading as a Dermoid Cyst and Bursitis of the Knee

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

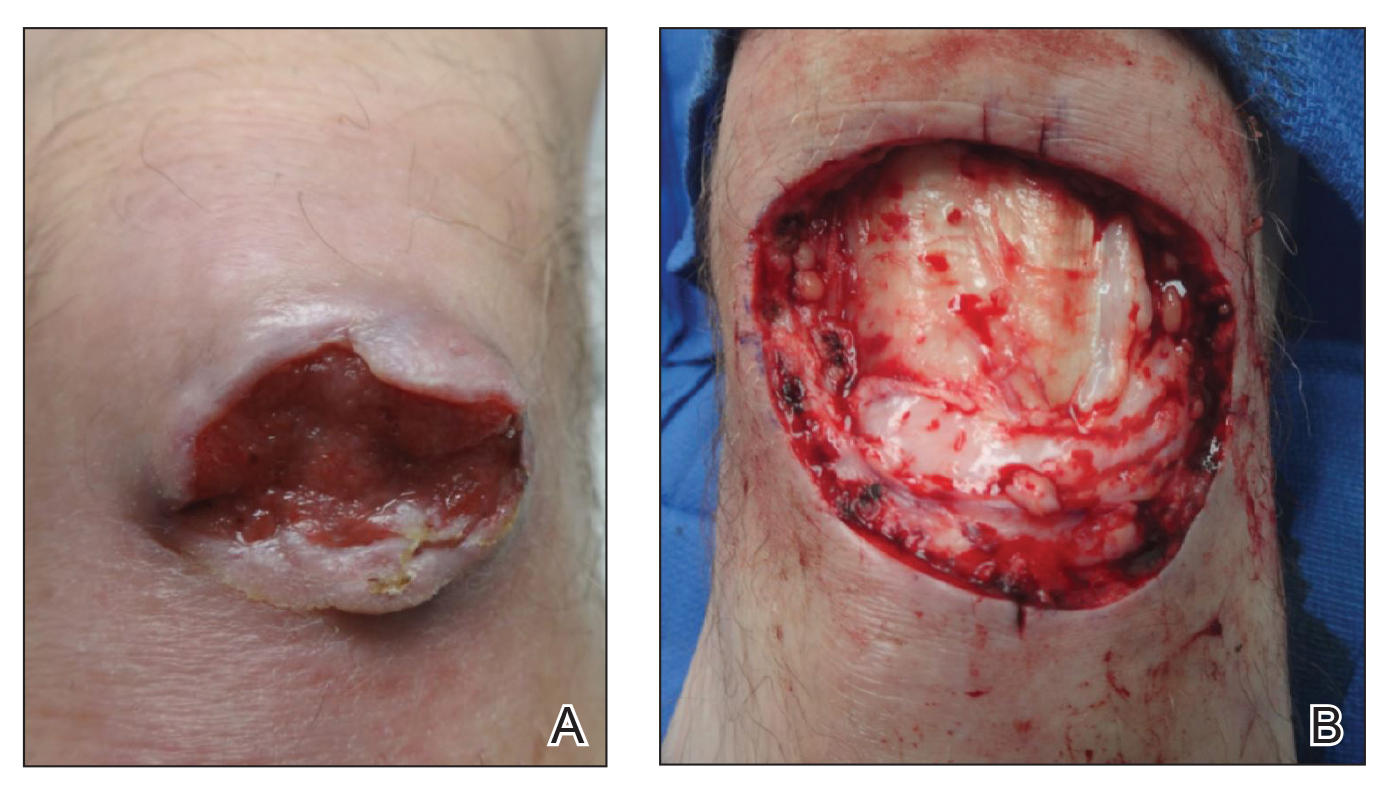

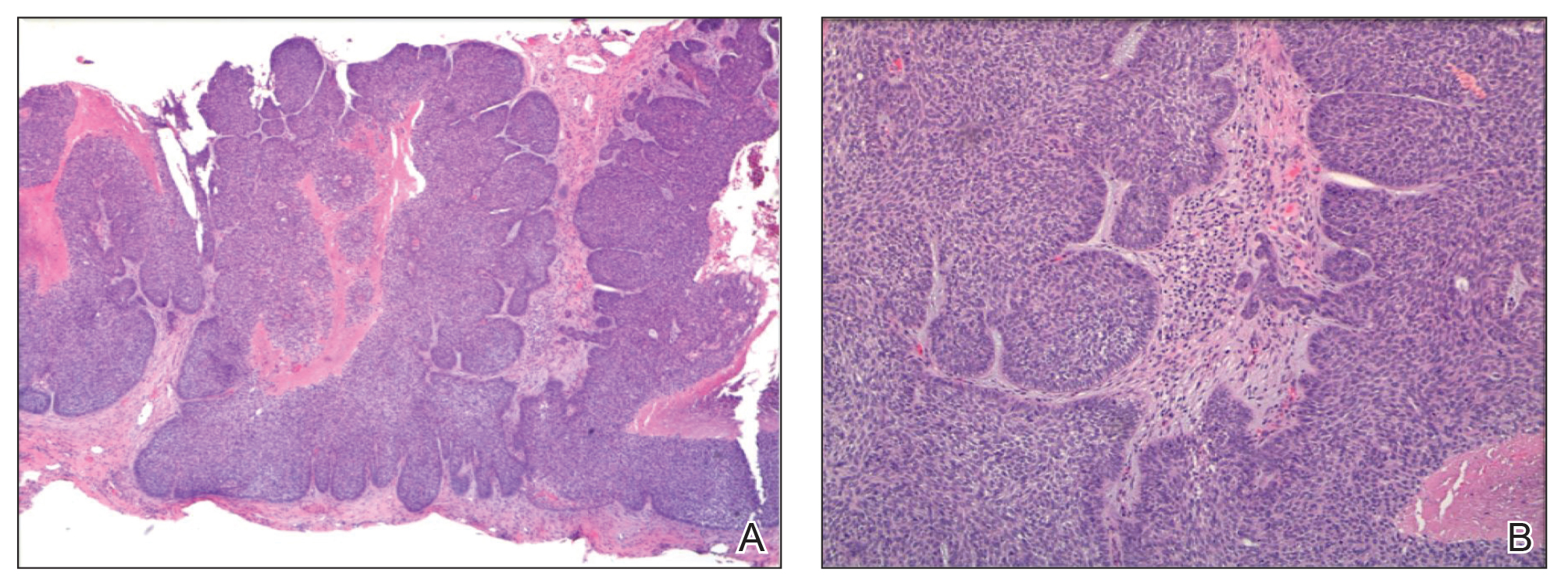

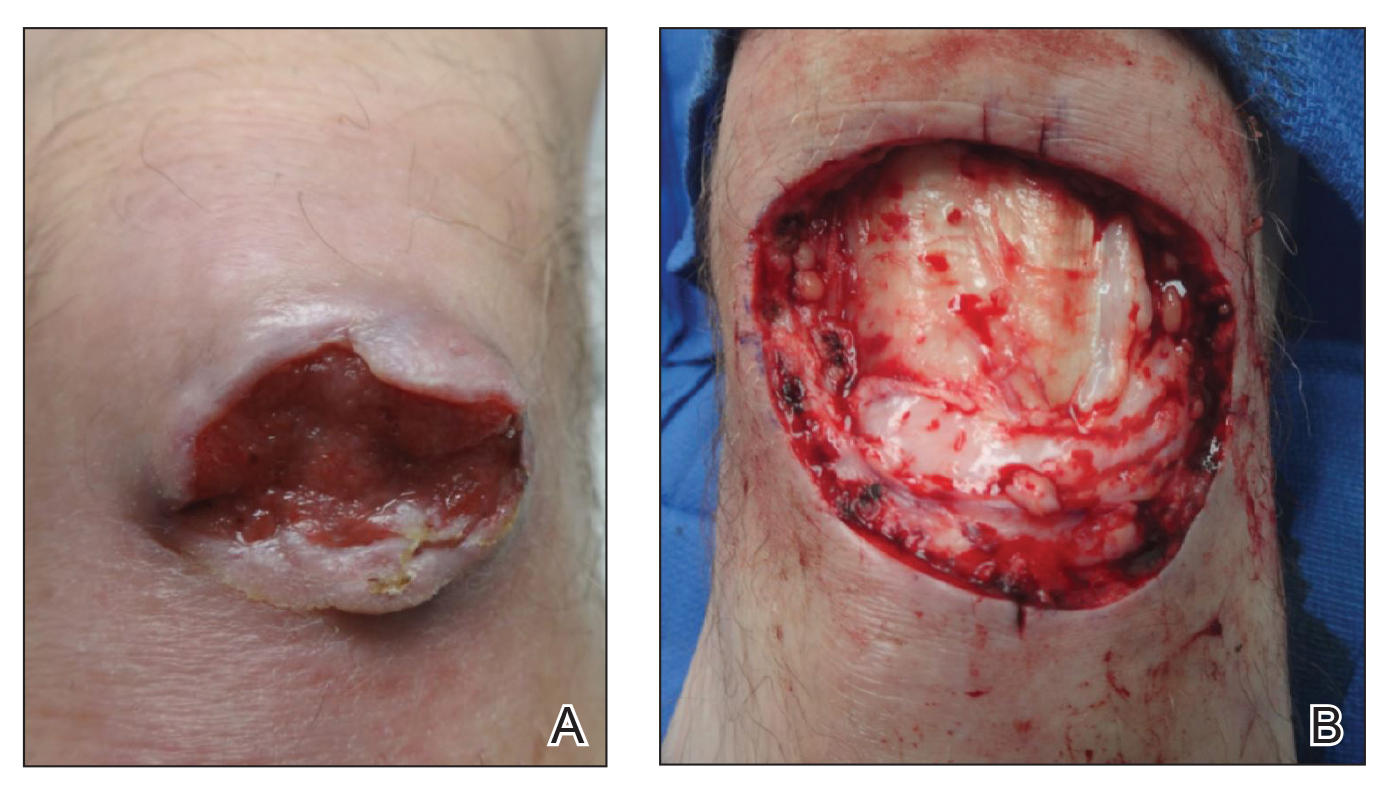

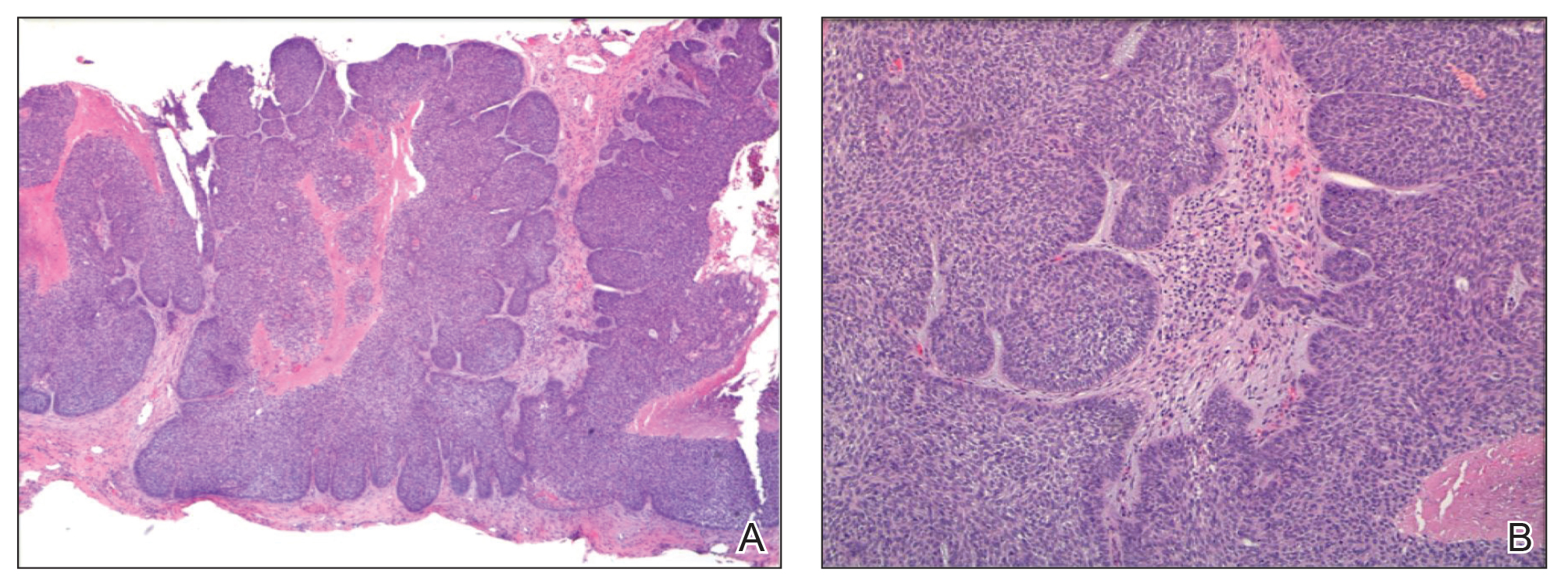

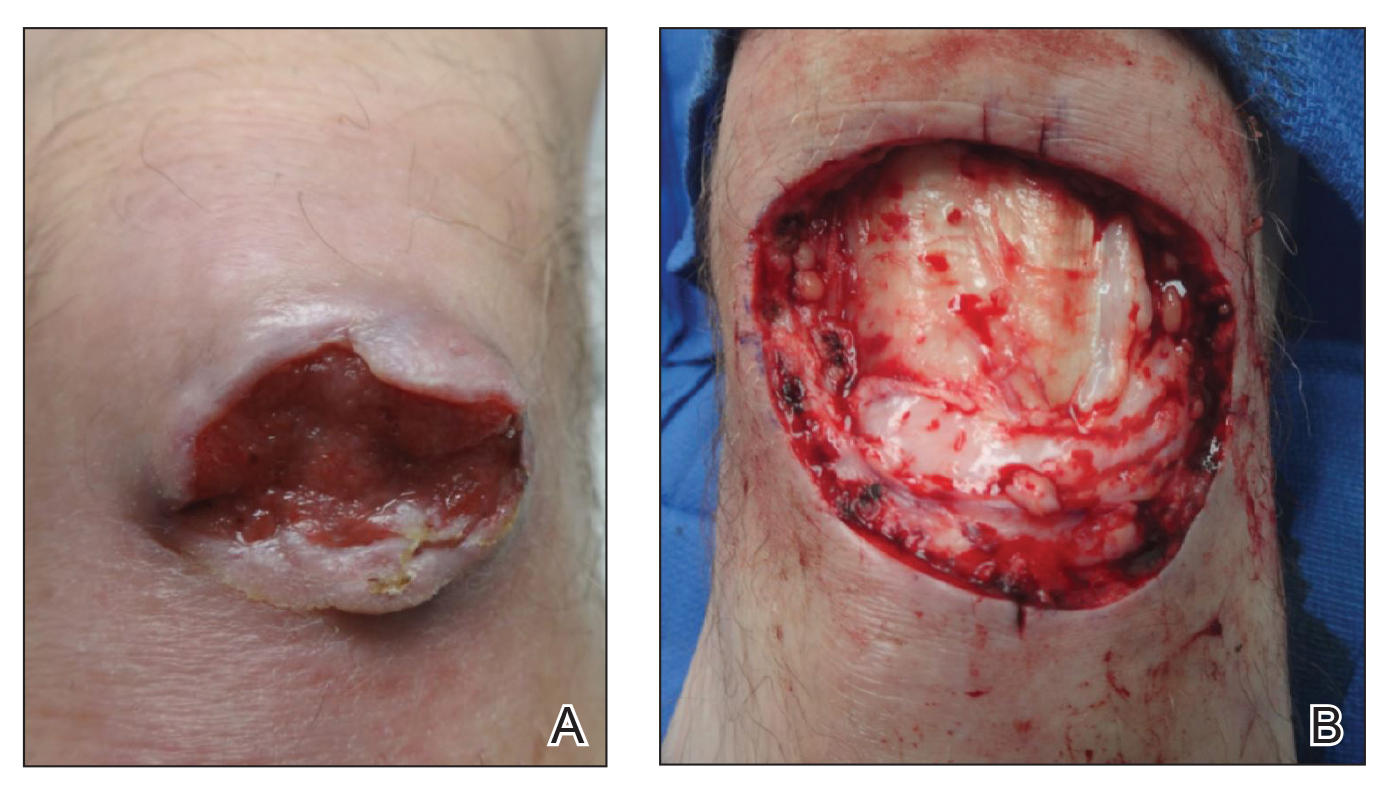

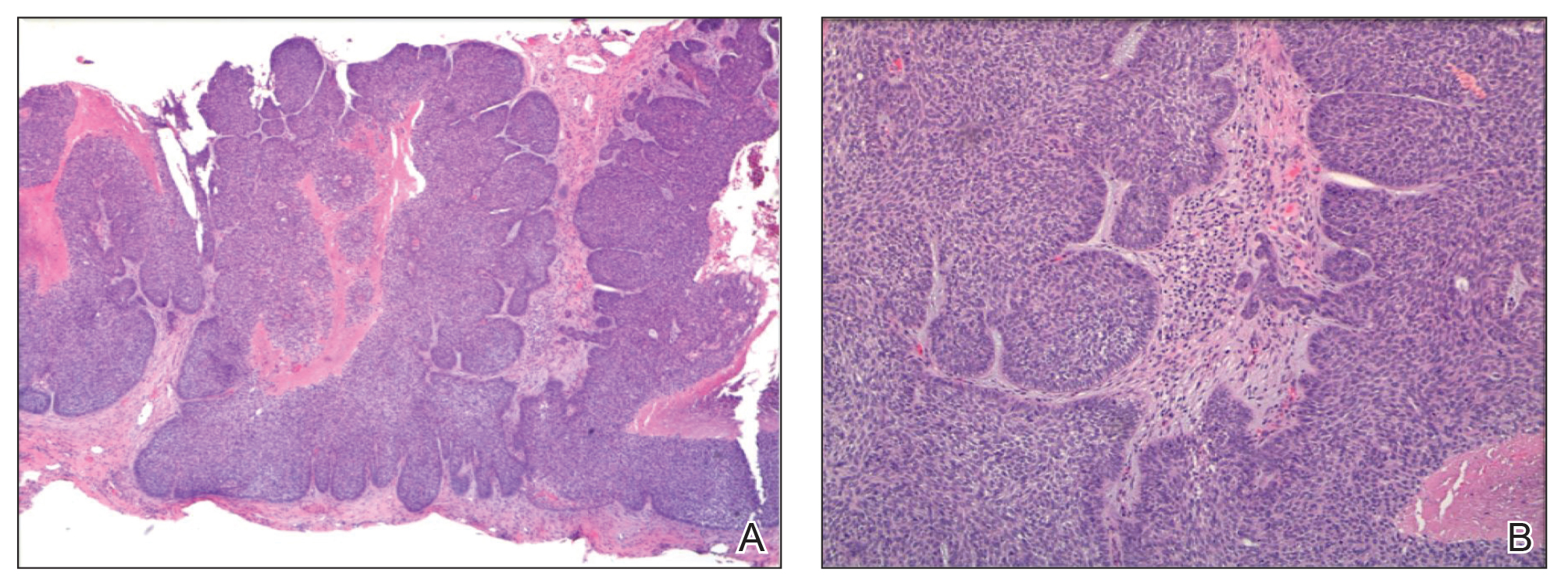

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Practice Points

- This case highlights an unusual presentation of basal cell carcinoma masquerading as bursitis.

- Clinicians should be aware of confirmation bias, especially when multiple physicians and specialists are involved in a case.

- When the initial clinical impression is not corroborated by objective data or the condition is not responding to conventional therapy, it is important for clinicians to revisit the possibility of an inaccurate diagnosis.