User login

What clinical clues differentiate migraine from sinus headaches?

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

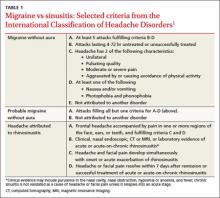

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

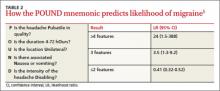

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Weight loss strategies that really work

• Calculate body mass index and diagnose obesity to increase the likelihood that obese patients will take steps to lose weight. B

• Prescribe a low-calorie diet for at least 6 months to help patients achieve a weight loss of at least 5% to 10%; prescribe physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. A

• Review the benefits and risks of bariatric surgery with patients who are severely obese, and provide a referral, when appropriate. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

It’s not only obese patients who are resistant to weight loss strategies. Many physicians contribute to the gap between current practice and optimal management of adult obesity, as well. There are a number of reasons for this—a dearth of knowledge, time, and reimbursement among them.1,2

What’s more, physicians are often pessimistic about how much headway patients can make in their weight loss efforts. That’s not surprising, given that the average weight loss achieved in well-controlled clinical trials tends to be modest and the recidivism rate is extremely high.3 Yet these same trials are cause for optimism, with substantial subsets of patients often achieving clinically meaningful long-term weight loss. The National Weight Control Registry, a long-term prospective study of “successful losers,” is another hopeful indicator: The registry includes approximately 6000 individuals who have lost, on average, more than 70 lb, and kept it off for an average of 6 years.4 (Listen to the audiocast at jfponline.com to find out how.)

Weight loss does not have to be huge to be clinically significant. Even a modest loss (5%-10% of total body weight) can have major health benefits. There’s much you can do to help.

Evidence suggests that patients are considerably more likely to lose weight when they are advised to do so and supported by their primary care physician.5-9 Because there is no way to predict which approach will be most effective for which patient, family physicians (FPs) should offer a variety of evidence-based treatments, including dietary change, increased physical activity, medication for selected patients, and surgery for severely obese adults (TABLE 1).

In 2009, the National Committee on Quality Assurance added body mass index (BMI) to the list of effectiveness-of-care measures that health plans and physicians are rated on.10 That addition, coupled with a recent study indicating that obesity accounts for more than 9% of annual health care expenditures,11 highlights the growing recognition that obesity should be considered a medical condition—not just a risk factor. While patients are increasingly likely to have a weight management insurance benefit that reimburses physicians and dietitians for multiple visits, many health plans still do not cover weight-related treatment. FPs can help by advocating for such coverage—and by taking steps to help patients win the battle against obesity.

TABLE 1

BMI, health risks, and weight loss: Which intervention for which patients?15

| Disease risk | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 (weight status) | Normal waist measurement | Elevated waist measurement | Diet and physical activity | Medication | Surgery |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | Increased | High | 25-26.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 27-29.9: Yes | 25-26.9: NA 27-29.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities | NA |

| 30-39.9 (obese) | 30-34.9: High 35-39.9: Very high | Very high | Yes | Yes | 30-34.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 35-39.9: Yes |

| ≥40 (extremely obese) | Extremely high | Extremely high | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BMI, body mass index; NA, not appropriate. | |||||

2 weight loss tools that can jump-start your efforts

Physicians often cite time as a key reason for not providing weight loss counseling. But physician knowledge—actually, lack of knowledge—may be a bigger barrier. In 1 recent study, 44% of physicians said they did not feel qualified to treat obesity.12 In another, 72% of primary care physicians surveyed said that no one in their practice was trained to deal with weight-related issues.13

As the focus on obesity grows, clinical weight management tools are increasingly available. Two excellent examples are the California Medical Association Foundation’s Obesity Provider Toolkit (www.thecmafoundation.org/projects/obesityProject.aspx) and the clinical tools from North Carolina’s Eat Smart, Move More program (www.eatsmartmovemorenc.com/ESMMPlan/ESMMPlan.html). You can download a toolkit, review the strategies described, and adopt those you think would be most effective in your practice. Doing so needn’t be especially time-consuming; evidence suggests you can provide basic counseling about healthy behaviors in fewer than 5 minutes.14

Review guidelines. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute issued the first evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of adult obesity in 1998.15 Many other groups—the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),16 the American Dietetic Association,17 and the American College of Physicians,18 among them—have followed suit, with guidelines addressing practical weight loss interventions and treatment related to specific comorbidities. The organizations all recommend using BMI to diagnose and classify obesity, assessing readiness to change, and setting realistic goals (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Obesity: Key components of evaluation and treatment

| Assess |

|

| Advise |

|

| Agree |

|

| Assist |

|

| Arrange |

|

| BMI, body mass index. | |

Diagnose obesity without delay

While most patients can report their height and weight with reasonable accuracy, few obese adults consider themselves to be obese.19 And, although the USPSTF 2009 recommendations call for screening all adults for obesity and introducing behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss as needed,20 most obese men and women receive neither a diagnosis nor an obesity management plan.21 Yet both are key components of long-term weight control. Physicians should calculate and document the BMI of all adult patients, and routinely diagnose obesity in patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (TABLE 1).

Get the patient’s perspective

In addition to using BMI and waist circumference measures and identifying comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, it is important to determine whether the patient is motivated to change. You can start by asking whether he or she has previously been told to lose weight; adults who have received weight control counseling in the past are more likely to be in a greater state of readiness.7

Review the patient’s medications. Once you have identified obesity, look for iatrogenic causes—most notably, current use of 1 or more medications that are associated with weight gain or known to affect satiety. If you identify any such drugs, it may be possible to find a suitable alternative (TABLE 3).

Factor in literacy. Patients with low literacy are less likely to fully comprehend the health benefits of weight loss or to report that they are ready to lose weight, as compared with those with higher literacy levels.22 Talking to such patients to determine what will spark their interest and motivation—ie, looking and feeling better, being able to play with children or grandchildren—can help.

Assess the patient’s dietary patterns. This can be done with the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants (REAP), an office-based tool of adequate reliability and validity for nutrition assessment and counseling that can be administered in a few minutes.23

This office-based survey, available at http://bms.brown.edu/nutrition/acrobat/REAP%206.pdf, provides information that can be the basis for an action plan. While there is no direct evidence that having a plan leads to weight loss, receiving advice from a physician is strongly associated with efforts to lose weight.6 Be aware that obese individuals may not be as responsive to weight management counseling from a physician as those who are overweight, so they may require more assistance.21

TABLE 3

Drugs that promote weight gain—and alternatives to consider46,52,53

| Indication/drug class/medication | Alternatives* |

|---|---|

Anticonvulsants/psychotropics Anticonvulsants | Topiramate‡ |

| Antimanic (bipolar) Lithium | Valproic acid,† carbamazepine† |

Antipsychotics Typical: Chlorpromazine, thiothixene, haloperidol | Ziprasidone

|

Antidepressants Tricyclics: Amitriptyline, imipramine |

Nortriptyline, protriptyline, desipramine |

Antidiabetics Sulfonylureas | Gliclazide, metformin, acarbose |

Antihypertensives Beta-blockers Calcium channel blockers | Guanfacine, doxazosin Acebutolol, atenolol, betaxolol, bisoprolol, labetalol, metoprolol, nadolol, pindolol Amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, nicardipine, nifedipine, verapamil |

Anti-inflammatories Corticosteroids | NSAIDs, COX inhibitors |

| COX, cyclooxygenase; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | |

| * Table is not meant to imply equal efficacy for all choices for a given indication. | |

| † Valproic acid and carbamazepine are associated with weight gain, but less than that associated with lithium. | |

| ‡ Topiramate may not be adequate as a single agent. | |

Set a goal, prescribe a food plan

After discussing possible interventions based on the patient’s BMI and weight status (TABLE 1), set a safe and achievable goal to reduce body weight at a rate of 1 to 2 lb per week for 6 months to achieve an initial weight loss goal of up to 10%. Not only does such a target have proven health benefits,15,24 but defining success in realistic and achievable terms helps maintain patient motivation.

Although no single dietary approach has been found to have a metabolic advantage or be most likely to support long-term weight maintenance,15,25-28 energy balance is central. It is critical to induce a negative energy balance—with a deficit of 250 to 500 calories per day to achieve a weight loss of 0.5 to 2 lb per week.

Which diet is best?

Diets emphasizing varying contents of carbohydrate, fat, and protein have generally been found to be equally successful in promoting clinically meaningful weight loss and maintenance over the course of 2 years, although some studies have found specific approaches to encourage initial weight loss.26 Because different strategies have proven helpful to various patients, your best bet is to analyze the patient’s eating pattern and prescribe the diet he or she is most likely to adhere to for at least 6 months.

If the patient has comorbidities, choose the diet expected to have the greatest impact—a low-glycemic diet for an obese patient with diabetes, for example, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) food plan for a patient with hypertension.27 For premenopausal women, diets low in carbohydrates have been found to facilitate weight loss without negative health consequences.25

Offer specific—and actionable—strategies

Most clinically obese patients (63%, according to 1 study) do not receive weight loss counseling from their primary care physician. Often, they are told to lose weight, but not given advice on how to do so. Providing specific strategies can help patients stay motivated.

One set of specific weight-loss messages comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Research to Practice Series.29 Patients are advised to:

- limit eating away from home

- select healthy options when eating out

- eat more fruits and vegetables

- avoid large portion sizes

- eat low energy-dense foods (ie, foods that are high in micronutrients but low in calories per gram).

The CDC also encourages new moms to breastfeed. In addition to helping the women themselves control their weight, breastfed infants appear to be more likely to maintain a normal body weight—an important consideration as overweight children are more likely than children of normal weight to become overweight adults.30 (To learn more about pediatric obesity, see “How best to help kids lose weight”.)

The “5-3-2-1-almost none” plan offers additional advice. Every day, patients should:

- Eat ≥5 servings of fruits and vegetables

- Have 3 structured meals (including breakfast)

- Limit TV/video game use to ≤2 hours

- Engage in ≥1 hour of moderate to vigorous physical activity

- Limit sugar-sweetened drinks to almost none.31

Encourage patients to keep a diary. Suggesting that patients track their food and beverage intake, as well as their physical activity, is another helpful strategy, as self-monitoring creates a sense of accountability and awareness. Patients are likely to need ongoing encouragement to do so, however, because record keeping typically declines with time.32,33

Prescribe physical activity, and sleep

Physical activity guidelines vary for active adults, older adults, and those with disabilities. To attain health benefits, however, the general recommendation is for ≥150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, plus muscle strengthening activities at least twice a week.33,34 Help patients identify strategies that will improve adherence, such as wearing a pedometer to gauge miles walked per day or working out with a buddy.34

Sleep duration, too, may affect weight. Although there is insufficient evidence to support the idea that sleep is an independent risk factor for obesity,35 it appears that those who sleep too much (9-10 hours per night) or too little (5-6 hours) have a 3- to 5-lb weight gain compared with those who sleep for 8 hours. One possible explanation is that there is a disruption in the production of hormones that affects appetite.4 Advise patients that getting enough sleep can help them control their weight.

Consider meal replacement, pharmacotherapy

For select patients, adherence to a low-calorie diet can be facilitated by the use of meal replacement products, as well as by pharmacotherapy. Each approach yields about a 5% to 7% weight loss.36 High-protein, high-fiber calorie-controlled shakes or bars can be particularly helpful for patients who have difficulty with food selection or portion control and can be effectively monitored by a physician or dietitian.37,38 Dietary fiber is also helpful in decreasing food intake and hunger.

Discuss the risks of supplements. Patients are bombarded by advertisements for dietary supplements. You can help by initiating a discussion of the lack of evidence of the efficacy and/or safety of most such products.

The most widely used herbal supplement, ephedrine, was taken off the market in 2006 for safety reasons. The US Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding many over-the-counter dietary products because a significant number of them have been found to contain undeclared active prescription ingredients.39

In general, published trials of dietary supplements are of suboptimal quality. There is limited evidence that caffeine may have a positive effect on thermogenesis and fat oxidation.4 A review of 1 promising dietary supplement, chitosan, found that the effect was minimal and unlikely to be of clinical significance.40 The evidence is weak for meaningful changes in weight or body composition for green tea catechins, conjugated linoleic acid, and chromium picolinate. Dietary calcium appears to aid in weight management, but the magnitude is controversial.41 Preliminary data about amino acids and neurotransmitter modulation are promising, but too little is currently known about these approaches.42 Fiber supplements, unlike most dietary supplements, are recommended, as dietary fiber decreases food intake and hunger.

Pharmacotherapy may boost weight loss. Two types of weight loss drugs—a lipase inhibitor (orlistat [Xenical]) and an appetite suppressant (sibutramine [Meridia])—are on the market. Research shows that pharmacotherapy, when combined with diet or physical activity, may enhance weight loss (usually <11 lb/year) in some adults, although the optimal duration of drug use has not been determined.16,17,43,44 The choice of medication should be based on the expected response to the medication. There is no evidence that either medication promotes more sustained weight loss than the other. In clinical trials, however, sibutramine produced a weight loss of 4.9 lb more than orlistat.44

While patients with hypertension have been found to achieve modest weight loss using either agent, orlistat reduced both diastolic and systolic pressure, while diastolic blood pressure increased with sibutramine.45 Metformin may help prevent excess weight gain associated with short-term use of atypical antipsychotics, although its use for this purpose is off-label.46

When to consider bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery continues to provide greater sustained weight loss and metabolic improvements than other conventional treatments.47 Identify patients who have failed at comprehensive weight loss programs and who are at high risk for obesity-associated morbidity and mortality (TABLE 1), and discuss the benefits (eg, reduction in comorbidities and at least a short-term improvement in health-related quality of life) and risks (eg, pulmonary embolism, anastomosis leakage, procedure-specific problems such as band slippage and erosion [after gastric banding], and possibly even death) of bariatric surgery. Refer potential candidates to an appropriate surgeon and facility.

Be aware, however, that the field of bariatric surgery is rapidly changing in terms of types of procedures, standards for perioperative care, patient selection, and reimbursement policies,48,49 and patients need to check with their insurance company before making any treatment decisions.

Common bariatric procedures include Roux-en Y gastric bypass (the gold standard); adjustable gastric banding; biliopancreatic diversion; and sleeve gastrectomy. Most are done laparoscopically. The sleeve gastrectomy, in which a vertical sleeve is created while much of the stomach is removed, may be useful for patients who are high-volume eaters, or to prepare extremely obese patients for gastric bypass. Patient selection is important, and multidisciplinary care is generally considered essential. After the surgery, the FP will play a key role, monitoring the patient’s medications, nutrition, physical activity, chronic conditions, and overall quality of life.

Adopt a team approach

Encourage your office staff to review the Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation 2010 (www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/obesityvision/obesityvision2010.pdf), which focuses on promoting, modeling, and working with patients to achieve a healthy lifestyle. The Surgeon General advocates a team approach to weight management, and recommends that patients have referrals to dietitians, psychologists, and community services.17,50

Interventions that include not only lifestyle modifications, but also behavioral modifications, such as hypnosis, can also be helpful. Computer-based strategies, such as Internet-based weight management programs and automated messaging, may be useful, as well, to break down barriers resulting from factors such as cost, time constraints, and lack of transportation or child care.51 Even when such programs are in use, however, it is important to remember that patients value—and benefit from—the support of their primary care physician.

Acknowledgement

This work has been presented in various Continuing Medical Education programs to audiences in North Carolina.

CORRESPONDENCE Kathryn M. Kolasa, PhD, RD, LDN, Department of Family Medicine, Mailstop 626, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834; kolasaka@ecu.edu

1. Manson JE, Skerrett PJ, Greenland P, et al. The escalating pandemics of obesity and sedentary lifestyle. A call to action for clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:249-258.

2. Murray J. What others take for granted. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:1677.-

3. Martens IL, Van Gaal LF. Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: the effects of modest weight reduction. Obes Res. 2000;8:270-278.

4. Hill JO, Wyatt H, Phelan S, et al. The National Weight Control Registry: is it useful in helping deal with our obesity epidemic? J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005;37:206-210.

5. Calfas KJ, Sallis JF, Zabinski MF, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a multicomponent program for nutrition and physical activity change in primary care: PACE+ for adults. Prev Med. 2002;34:153-161.

6. Ockene IS, Herbert JR, Ockene JK, et al. Effect of physician delivered nutrition counseling training and an office support program on saturated fat intake, weight, and serum lipid measurements in a hyperlipidemic population (WATCH). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725-731.

7. Simkin-Silverman LR, Gleason KA, King WC, et al. Predictors of weight control advice in primary care practices: patient health and psychosocial characteristics. Prev Med. 2005;40:71-82.

8. Flocke SA, Clark A, Schlessman K, et al. Exercise, diet, and weight loss advice in the family medicine outpatient setting. Fam Med. 2005;37:415-421.

9. Ryan DH, Johnson WD, Myers VH, et al. Nonsurgical weight loss for extreme obesity in primary care settings: results of the Louisiana Obese Subjects Study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:146-154.

10. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Obesity screening measures highlight additions to HEDIS 2009. February 14, 2008. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/662/Default.aspx. Accessed June 7, 2010.

11. Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, et al. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w822-w831.

12. Jay M, Kalet A, Ark T, et al. Physicians’ attitudes about obesity and their associations with competency and specialty: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:106.-

13. STOP Obesity Alliance. STOP Obesity Alliance surveys show doctors, patients share role in weight loss, but ask, now what? March 16, 2010. Available at: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2010-03/cca-soa031510.php. Accessed June 7, 2010.

14. Ferguson C, Langwith C, Muldoon A, et al. STOP Obesity Alliance Research Team, George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services. Improving obesity management in adult primary care. White paper. March 16, 2010.

15. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. North American Association for the Study of Obesity. The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation , and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. 2000. NIH Publication No. 00-4084.

16. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:930-932.

17. American Dietetic Association. Adult weight management evidence based nutrition practice guidelines. Available at: http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com. Accessed September 9, 2009.

18. Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, et al. Clinical efficacy assessment subcommittee of the American College of Physicians. Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:525-531.

19. Truesdale KP, Stevens J. Do the obese know they are obese? N C Med J. 2008;69:188-194.

20. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to clinical preventive services, 2009. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd09/. Accessed March 30, 2010.

21. Bardia A, Holtan SG, Slezak JM, et al. Diagnosis of obesity by primary care physicians and impact on obesity management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:927-932.

22. Kennen EM, Davis TC, Huang J, et al. Tipping the scales: the effect of literacy on obese patients’ knowledge and readiness to lose weight. South Med J. 2005;98:15-18.

23. Gans KM, Risica PM, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Development and evaluation of the nutrition component of the Rapid Eating and Activity Assessment for Patients (REAP): a new tool for primary care providers. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:286-292.

24. Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB, et al. Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41-50.

25. Atkins, Zone, Ornish, or LEARN—which diet kept weight off? J Fam Pract 2007;56:434.-

26. Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:859-873.

27. Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148.

28. Thomas DE, Elliott EJ, Baur L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005105.-

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and overweight for professionals: Resources/DNPAO/CDC. Updated 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/resources.html#R2P. Accessed December 10, 2009.

30. Rowland K, Coffey J. Are overweight children more likely to be overweight adults? J Fam Pract. 2009;58:431-432.

31. Eat Smart, Move More. North Carolina. Prescription for health. Available at: PrescriptionPadColor.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2010.

32. Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, et al. Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss maintenance trial. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:118-126.

33. Burke LE, Swigart V, Turk MW, et al. Experiences of self-monitoring: successes and struggles during treatment for weight loss. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:815.-

34. Cudjoe S, Moss S, Nguyen L, et al. Clinical inquiries. How do exercise and diet compare for weight loss? J Fam Pract. 2007;56:841-844.

35. Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:643-653.

36. Early JL, Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, et al. Sibutramine plus meal replacement therapy for body weight loss and maintenance in obese patients. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:1464-1472.

37. Ashley JM, St Jeor ST, Schrage JP, et al. Weight control in the physician’s office. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1599-1604.

38. Bowerman S, Bellman M, Saltsman P, et al. Implementation of a primary care physician network obesity management program. Obes Res. 2001;9(suppl 4):321S-325S.

39. Kuehn B. Tainted diet drugs. JAMA. 2009;301:817.-

40. Jull AB, Ni Mhurchu C, Bennett DA, et al. Chitosan for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD003892.-

41. Teegarden D, Gunther CW. Can the controversial relationship between dietary calcium and body weight be mechanistically explained by alterations in appetite and food intake? Nutr Rev. 2008;66:601-605.

42. Greenway R, Heber D. Herbal and alternative approaches to obesity. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, eds. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. 3rd ed. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008: 425-443.

43. Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;144:532-546.

44. Neovius M, Johansson K, Rossner S. Head-to-head studies evaluating efficacy of pharmacotherapy for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2008;9:420-427.

45. Siebenhofer A, Korvath K, Jeitler K, et al. Long-term effects of weight-reducing drugs in hypertensive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD007654.-

46. Miller LJ. Management of atypical antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain: focus on metformin. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:725-735.

47. Colquitt JL, Picot J, Loveman E, et al. Surgery for obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003641.-

48. Blackburn GL, Hutter MM, Harvey AM, et al. Expert panel on weight loss surgery: executive report update. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:842-862.

49. Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(suppl 1):S1-S83.

50. Helman T. Weight management by family physicians. Arbor Clin Nutrition Updates. 2002 Feb;116:1-2. Available at: www.arborcom.com/free/116.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2010.

51. Holt J, Warren L, Wallace R, et al. Clinical inquiries. What behavioral interventions are safe and effective for treating obesity? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:536-538.

52. Cheskin LJ, Bartlett SJ, Zayas R, et al. Prescription medications: a modifiable contributor to obesity. South Med J. 1999;92:898-904.

53. Parsons B, Allison DB, Loebel A, et al. Weight effects associated with antipsychotics: a comprehensive database analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;110:103-110.

• Calculate body mass index and diagnose obesity to increase the likelihood that obese patients will take steps to lose weight. B

• Prescribe a low-calorie diet for at least 6 months to help patients achieve a weight loss of at least 5% to 10%; prescribe physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. A

• Review the benefits and risks of bariatric surgery with patients who are severely obese, and provide a referral, when appropriate. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

It’s not only obese patients who are resistant to weight loss strategies. Many physicians contribute to the gap between current practice and optimal management of adult obesity, as well. There are a number of reasons for this—a dearth of knowledge, time, and reimbursement among them.1,2

What’s more, physicians are often pessimistic about how much headway patients can make in their weight loss efforts. That’s not surprising, given that the average weight loss achieved in well-controlled clinical trials tends to be modest and the recidivism rate is extremely high.3 Yet these same trials are cause for optimism, with substantial subsets of patients often achieving clinically meaningful long-term weight loss. The National Weight Control Registry, a long-term prospective study of “successful losers,” is another hopeful indicator: The registry includes approximately 6000 individuals who have lost, on average, more than 70 lb, and kept it off for an average of 6 years.4 (Listen to the audiocast at jfponline.com to find out how.)

Weight loss does not have to be huge to be clinically significant. Even a modest loss (5%-10% of total body weight) can have major health benefits. There’s much you can do to help.

Evidence suggests that patients are considerably more likely to lose weight when they are advised to do so and supported by their primary care physician.5-9 Because there is no way to predict which approach will be most effective for which patient, family physicians (FPs) should offer a variety of evidence-based treatments, including dietary change, increased physical activity, medication for selected patients, and surgery for severely obese adults (TABLE 1).

In 2009, the National Committee on Quality Assurance added body mass index (BMI) to the list of effectiveness-of-care measures that health plans and physicians are rated on.10 That addition, coupled with a recent study indicating that obesity accounts for more than 9% of annual health care expenditures,11 highlights the growing recognition that obesity should be considered a medical condition—not just a risk factor. While patients are increasingly likely to have a weight management insurance benefit that reimburses physicians and dietitians for multiple visits, many health plans still do not cover weight-related treatment. FPs can help by advocating for such coverage—and by taking steps to help patients win the battle against obesity.

TABLE 1

BMI, health risks, and weight loss: Which intervention for which patients?15

| Disease risk | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 (weight status) | Normal waist measurement | Elevated waist measurement | Diet and physical activity | Medication | Surgery |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | Increased | High | 25-26.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 27-29.9: Yes | 25-26.9: NA 27-29.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities | NA |

| 30-39.9 (obese) | 30-34.9: High 35-39.9: Very high | Very high | Yes | Yes | 30-34.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 35-39.9: Yes |

| ≥40 (extremely obese) | Extremely high | Extremely high | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BMI, body mass index; NA, not appropriate. | |||||

2 weight loss tools that can jump-start your efforts

Physicians often cite time as a key reason for not providing weight loss counseling. But physician knowledge—actually, lack of knowledge—may be a bigger barrier. In 1 recent study, 44% of physicians said they did not feel qualified to treat obesity.12 In another, 72% of primary care physicians surveyed said that no one in their practice was trained to deal with weight-related issues.13

As the focus on obesity grows, clinical weight management tools are increasingly available. Two excellent examples are the California Medical Association Foundation’s Obesity Provider Toolkit (www.thecmafoundation.org/projects/obesityProject.aspx) and the clinical tools from North Carolina’s Eat Smart, Move More program (www.eatsmartmovemorenc.com/ESMMPlan/ESMMPlan.html). You can download a toolkit, review the strategies described, and adopt those you think would be most effective in your practice. Doing so needn’t be especially time-consuming; evidence suggests you can provide basic counseling about healthy behaviors in fewer than 5 minutes.14

Review guidelines. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute issued the first evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of adult obesity in 1998.15 Many other groups—the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),16 the American Dietetic Association,17 and the American College of Physicians,18 among them—have followed suit, with guidelines addressing practical weight loss interventions and treatment related to specific comorbidities. The organizations all recommend using BMI to diagnose and classify obesity, assessing readiness to change, and setting realistic goals (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Obesity: Key components of evaluation and treatment

| Assess |

|

| Advise |

|

| Agree |

|

| Assist |

|

| Arrange |

|

| BMI, body mass index. | |

Diagnose obesity without delay

While most patients can report their height and weight with reasonable accuracy, few obese adults consider themselves to be obese.19 And, although the USPSTF 2009 recommendations call for screening all adults for obesity and introducing behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss as needed,20 most obese men and women receive neither a diagnosis nor an obesity management plan.21 Yet both are key components of long-term weight control. Physicians should calculate and document the BMI of all adult patients, and routinely diagnose obesity in patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (TABLE 1).

Get the patient’s perspective

In addition to using BMI and waist circumference measures and identifying comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, it is important to determine whether the patient is motivated to change. You can start by asking whether he or she has previously been told to lose weight; adults who have received weight control counseling in the past are more likely to be in a greater state of readiness.7

Review the patient’s medications. Once you have identified obesity, look for iatrogenic causes—most notably, current use of 1 or more medications that are associated with weight gain or known to affect satiety. If you identify any such drugs, it may be possible to find a suitable alternative (TABLE 3).

Factor in literacy. Patients with low literacy are less likely to fully comprehend the health benefits of weight loss or to report that they are ready to lose weight, as compared with those with higher literacy levels.22 Talking to such patients to determine what will spark their interest and motivation—ie, looking and feeling better, being able to play with children or grandchildren—can help.

Assess the patient’s dietary patterns. This can be done with the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants (REAP), an office-based tool of adequate reliability and validity for nutrition assessment and counseling that can be administered in a few minutes.23

This office-based survey, available at http://bms.brown.edu/nutrition/acrobat/REAP%206.pdf, provides information that can be the basis for an action plan. While there is no direct evidence that having a plan leads to weight loss, receiving advice from a physician is strongly associated with efforts to lose weight.6 Be aware that obese individuals may not be as responsive to weight management counseling from a physician as those who are overweight, so they may require more assistance.21

TABLE 3

Drugs that promote weight gain—and alternatives to consider46,52,53

| Indication/drug class/medication | Alternatives* |

|---|---|

Anticonvulsants/psychotropics Anticonvulsants | Topiramate‡ |

| Antimanic (bipolar) Lithium | Valproic acid,† carbamazepine† |

Antipsychotics Typical: Chlorpromazine, thiothixene, haloperidol | Ziprasidone

|

Antidepressants Tricyclics: Amitriptyline, imipramine |

Nortriptyline, protriptyline, desipramine |

Antidiabetics Sulfonylureas | Gliclazide, metformin, acarbose |

Antihypertensives Beta-blockers Calcium channel blockers | Guanfacine, doxazosin Acebutolol, atenolol, betaxolol, bisoprolol, labetalol, metoprolol, nadolol, pindolol Amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, nicardipine, nifedipine, verapamil |

Anti-inflammatories Corticosteroids | NSAIDs, COX inhibitors |

| COX, cyclooxygenase; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | |

| * Table is not meant to imply equal efficacy for all choices for a given indication. | |

| † Valproic acid and carbamazepine are associated with weight gain, but less than that associated with lithium. | |

| ‡ Topiramate may not be adequate as a single agent. | |

Set a goal, prescribe a food plan

After discussing possible interventions based on the patient’s BMI and weight status (TABLE 1), set a safe and achievable goal to reduce body weight at a rate of 1 to 2 lb per week for 6 months to achieve an initial weight loss goal of up to 10%. Not only does such a target have proven health benefits,15,24 but defining success in realistic and achievable terms helps maintain patient motivation.

Although no single dietary approach has been found to have a metabolic advantage or be most likely to support long-term weight maintenance,15,25-28 energy balance is central. It is critical to induce a negative energy balance—with a deficit of 250 to 500 calories per day to achieve a weight loss of 0.5 to 2 lb per week.

Which diet is best?

Diets emphasizing varying contents of carbohydrate, fat, and protein have generally been found to be equally successful in promoting clinically meaningful weight loss and maintenance over the course of 2 years, although some studies have found specific approaches to encourage initial weight loss.26 Because different strategies have proven helpful to various patients, your best bet is to analyze the patient’s eating pattern and prescribe the diet he or she is most likely to adhere to for at least 6 months.

If the patient has comorbidities, choose the diet expected to have the greatest impact—a low-glycemic diet for an obese patient with diabetes, for example, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) food plan for a patient with hypertension.27 For premenopausal women, diets low in carbohydrates have been found to facilitate weight loss without negative health consequences.25

Offer specific—and actionable—strategies

Most clinically obese patients (63%, according to 1 study) do not receive weight loss counseling from their primary care physician. Often, they are told to lose weight, but not given advice on how to do so. Providing specific strategies can help patients stay motivated.

One set of specific weight-loss messages comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Research to Practice Series.29 Patients are advised to:

- limit eating away from home

- select healthy options when eating out

- eat more fruits and vegetables

- avoid large portion sizes

- eat low energy-dense foods (ie, foods that are high in micronutrients but low in calories per gram).

The CDC also encourages new moms to breastfeed. In addition to helping the women themselves control their weight, breastfed infants appear to be more likely to maintain a normal body weight—an important consideration as overweight children are more likely than children of normal weight to become overweight adults.30 (To learn more about pediatric obesity, see “How best to help kids lose weight”.)

The “5-3-2-1-almost none” plan offers additional advice. Every day, patients should:

- Eat ≥5 servings of fruits and vegetables

- Have 3 structured meals (including breakfast)

- Limit TV/video game use to ≤2 hours

- Engage in ≥1 hour of moderate to vigorous physical activity

- Limit sugar-sweetened drinks to almost none.31

Encourage patients to keep a diary. Suggesting that patients track their food and beverage intake, as well as their physical activity, is another helpful strategy, as self-monitoring creates a sense of accountability and awareness. Patients are likely to need ongoing encouragement to do so, however, because record keeping typically declines with time.32,33

Prescribe physical activity, and sleep

Physical activity guidelines vary for active adults, older adults, and those with disabilities. To attain health benefits, however, the general recommendation is for ≥150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, plus muscle strengthening activities at least twice a week.33,34 Help patients identify strategies that will improve adherence, such as wearing a pedometer to gauge miles walked per day or working out with a buddy.34

Sleep duration, too, may affect weight. Although there is insufficient evidence to support the idea that sleep is an independent risk factor for obesity,35 it appears that those who sleep too much (9-10 hours per night) or too little (5-6 hours) have a 3- to 5-lb weight gain compared with those who sleep for 8 hours. One possible explanation is that there is a disruption in the production of hormones that affects appetite.4 Advise patients that getting enough sleep can help them control their weight.

Consider meal replacement, pharmacotherapy

For select patients, adherence to a low-calorie diet can be facilitated by the use of meal replacement products, as well as by pharmacotherapy. Each approach yields about a 5% to 7% weight loss.36 High-protein, high-fiber calorie-controlled shakes or bars can be particularly helpful for patients who have difficulty with food selection or portion control and can be effectively monitored by a physician or dietitian.37,38 Dietary fiber is also helpful in decreasing food intake and hunger.

Discuss the risks of supplements. Patients are bombarded by advertisements for dietary supplements. You can help by initiating a discussion of the lack of evidence of the efficacy and/or safety of most such products.

The most widely used herbal supplement, ephedrine, was taken off the market in 2006 for safety reasons. The US Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding many over-the-counter dietary products because a significant number of them have been found to contain undeclared active prescription ingredients.39

In general, published trials of dietary supplements are of suboptimal quality. There is limited evidence that caffeine may have a positive effect on thermogenesis and fat oxidation.4 A review of 1 promising dietary supplement, chitosan, found that the effect was minimal and unlikely to be of clinical significance.40 The evidence is weak for meaningful changes in weight or body composition for green tea catechins, conjugated linoleic acid, and chromium picolinate. Dietary calcium appears to aid in weight management, but the magnitude is controversial.41 Preliminary data about amino acids and neurotransmitter modulation are promising, but too little is currently known about these approaches.42 Fiber supplements, unlike most dietary supplements, are recommended, as dietary fiber decreases food intake and hunger.

Pharmacotherapy may boost weight loss. Two types of weight loss drugs—a lipase inhibitor (orlistat [Xenical]) and an appetite suppressant (sibutramine [Meridia])—are on the market. Research shows that pharmacotherapy, when combined with diet or physical activity, may enhance weight loss (usually <11 lb/year) in some adults, although the optimal duration of drug use has not been determined.16,17,43,44 The choice of medication should be based on the expected response to the medication. There is no evidence that either medication promotes more sustained weight loss than the other. In clinical trials, however, sibutramine produced a weight loss of 4.9 lb more than orlistat.44

While patients with hypertension have been found to achieve modest weight loss using either agent, orlistat reduced both diastolic and systolic pressure, while diastolic blood pressure increased with sibutramine.45 Metformin may help prevent excess weight gain associated with short-term use of atypical antipsychotics, although its use for this purpose is off-label.46

When to consider bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery continues to provide greater sustained weight loss and metabolic improvements than other conventional treatments.47 Identify patients who have failed at comprehensive weight loss programs and who are at high risk for obesity-associated morbidity and mortality (TABLE 1), and discuss the benefits (eg, reduction in comorbidities and at least a short-term improvement in health-related quality of life) and risks (eg, pulmonary embolism, anastomosis leakage, procedure-specific problems such as band slippage and erosion [after gastric banding], and possibly even death) of bariatric surgery. Refer potential candidates to an appropriate surgeon and facility.

Be aware, however, that the field of bariatric surgery is rapidly changing in terms of types of procedures, standards for perioperative care, patient selection, and reimbursement policies,48,49 and patients need to check with their insurance company before making any treatment decisions.

Common bariatric procedures include Roux-en Y gastric bypass (the gold standard); adjustable gastric banding; biliopancreatic diversion; and sleeve gastrectomy. Most are done laparoscopically. The sleeve gastrectomy, in which a vertical sleeve is created while much of the stomach is removed, may be useful for patients who are high-volume eaters, or to prepare extremely obese patients for gastric bypass. Patient selection is important, and multidisciplinary care is generally considered essential. After the surgery, the FP will play a key role, monitoring the patient’s medications, nutrition, physical activity, chronic conditions, and overall quality of life.

Adopt a team approach

Encourage your office staff to review the Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation 2010 (www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/obesityvision/obesityvision2010.pdf), which focuses on promoting, modeling, and working with patients to achieve a healthy lifestyle. The Surgeon General advocates a team approach to weight management, and recommends that patients have referrals to dietitians, psychologists, and community services.17,50

Interventions that include not only lifestyle modifications, but also behavioral modifications, such as hypnosis, can also be helpful. Computer-based strategies, such as Internet-based weight management programs and automated messaging, may be useful, as well, to break down barriers resulting from factors such as cost, time constraints, and lack of transportation or child care.51 Even when such programs are in use, however, it is important to remember that patients value—and benefit from—the support of their primary care physician.

Acknowledgement

This work has been presented in various Continuing Medical Education programs to audiences in North Carolina.

CORRESPONDENCE Kathryn M. Kolasa, PhD, RD, LDN, Department of Family Medicine, Mailstop 626, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834; kolasaka@ecu.edu

• Calculate body mass index and diagnose obesity to increase the likelihood that obese patients will take steps to lose weight. B

• Prescribe a low-calorie diet for at least 6 months to help patients achieve a weight loss of at least 5% to 10%; prescribe physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. A

• Review the benefits and risks of bariatric surgery with patients who are severely obese, and provide a referral, when appropriate. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

It’s not only obese patients who are resistant to weight loss strategies. Many physicians contribute to the gap between current practice and optimal management of adult obesity, as well. There are a number of reasons for this—a dearth of knowledge, time, and reimbursement among them.1,2

What’s more, physicians are often pessimistic about how much headway patients can make in their weight loss efforts. That’s not surprising, given that the average weight loss achieved in well-controlled clinical trials tends to be modest and the recidivism rate is extremely high.3 Yet these same trials are cause for optimism, with substantial subsets of patients often achieving clinically meaningful long-term weight loss. The National Weight Control Registry, a long-term prospective study of “successful losers,” is another hopeful indicator: The registry includes approximately 6000 individuals who have lost, on average, more than 70 lb, and kept it off for an average of 6 years.4 (Listen to the audiocast at jfponline.com to find out how.)

Weight loss does not have to be huge to be clinically significant. Even a modest loss (5%-10% of total body weight) can have major health benefits. There’s much you can do to help.

Evidence suggests that patients are considerably more likely to lose weight when they are advised to do so and supported by their primary care physician.5-9 Because there is no way to predict which approach will be most effective for which patient, family physicians (FPs) should offer a variety of evidence-based treatments, including dietary change, increased physical activity, medication for selected patients, and surgery for severely obese adults (TABLE 1).

In 2009, the National Committee on Quality Assurance added body mass index (BMI) to the list of effectiveness-of-care measures that health plans and physicians are rated on.10 That addition, coupled with a recent study indicating that obesity accounts for more than 9% of annual health care expenditures,11 highlights the growing recognition that obesity should be considered a medical condition—not just a risk factor. While patients are increasingly likely to have a weight management insurance benefit that reimburses physicians and dietitians for multiple visits, many health plans still do not cover weight-related treatment. FPs can help by advocating for such coverage—and by taking steps to help patients win the battle against obesity.

TABLE 1

BMI, health risks, and weight loss: Which intervention for which patients?15

| Disease risk | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 (weight status) | Normal waist measurement | Elevated waist measurement | Diet and physical activity | Medication | Surgery |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | Increased | High | 25-26.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 27-29.9: Yes | 25-26.9: NA 27-29.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities | NA |

| 30-39.9 (obese) | 30-34.9: High 35-39.9: Very high | Very high | Yes | Yes | 30-34.9: Yes, for patients with comorbidities 35-39.9: Yes |

| ≥40 (extremely obese) | Extremely high | Extremely high | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BMI, body mass index; NA, not appropriate. | |||||

2 weight loss tools that can jump-start your efforts

Physicians often cite time as a key reason for not providing weight loss counseling. But physician knowledge—actually, lack of knowledge—may be a bigger barrier. In 1 recent study, 44% of physicians said they did not feel qualified to treat obesity.12 In another, 72% of primary care physicians surveyed said that no one in their practice was trained to deal with weight-related issues.13

As the focus on obesity grows, clinical weight management tools are increasingly available. Two excellent examples are the California Medical Association Foundation’s Obesity Provider Toolkit (www.thecmafoundation.org/projects/obesityProject.aspx) and the clinical tools from North Carolina’s Eat Smart, Move More program (www.eatsmartmovemorenc.com/ESMMPlan/ESMMPlan.html). You can download a toolkit, review the strategies described, and adopt those you think would be most effective in your practice. Doing so needn’t be especially time-consuming; evidence suggests you can provide basic counseling about healthy behaviors in fewer than 5 minutes.14

Review guidelines. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute issued the first evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of adult obesity in 1998.15 Many other groups—the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),16 the American Dietetic Association,17 and the American College of Physicians,18 among them—have followed suit, with guidelines addressing practical weight loss interventions and treatment related to specific comorbidities. The organizations all recommend using BMI to diagnose and classify obesity, assessing readiness to change, and setting realistic goals (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Obesity: Key components of evaluation and treatment

| Assess |

|

| Advise |

|

| Agree |

|

| Assist |

|

| Arrange |

|

| BMI, body mass index. | |

Diagnose obesity without delay

While most patients can report their height and weight with reasonable accuracy, few obese adults consider themselves to be obese.19 And, although the USPSTF 2009 recommendations call for screening all adults for obesity and introducing behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss as needed,20 most obese men and women receive neither a diagnosis nor an obesity management plan.21 Yet both are key components of long-term weight control. Physicians should calculate and document the BMI of all adult patients, and routinely diagnose obesity in patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (TABLE 1).

Get the patient’s perspective

In addition to using BMI and waist circumference measures and identifying comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, it is important to determine whether the patient is motivated to change. You can start by asking whether he or she has previously been told to lose weight; adults who have received weight control counseling in the past are more likely to be in a greater state of readiness.7

Review the patient’s medications. Once you have identified obesity, look for iatrogenic causes—most notably, current use of 1 or more medications that are associated with weight gain or known to affect satiety. If you identify any such drugs, it may be possible to find a suitable alternative (TABLE 3).

Factor in literacy. Patients with low literacy are less likely to fully comprehend the health benefits of weight loss or to report that they are ready to lose weight, as compared with those with higher literacy levels.22 Talking to such patients to determine what will spark their interest and motivation—ie, looking and feeling better, being able to play with children or grandchildren—can help.

Assess the patient’s dietary patterns. This can be done with the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants (REAP), an office-based tool of adequate reliability and validity for nutrition assessment and counseling that can be administered in a few minutes.23

This office-based survey, available at http://bms.brown.edu/nutrition/acrobat/REAP%206.pdf, provides information that can be the basis for an action plan. While there is no direct evidence that having a plan leads to weight loss, receiving advice from a physician is strongly associated with efforts to lose weight.6 Be aware that obese individuals may not be as responsive to weight management counseling from a physician as those who are overweight, so they may require more assistance.21

TABLE 3

Drugs that promote weight gain—and alternatives to consider46,52,53

| Indication/drug class/medication | Alternatives* |

|---|---|

Anticonvulsants/psychotropics Anticonvulsants | Topiramate‡ |

| Antimanic (bipolar) Lithium | Valproic acid,† carbamazepine† |

Antipsychotics Typical: Chlorpromazine, thiothixene, haloperidol | Ziprasidone

|

Antidepressants Tricyclics: Amitriptyline, imipramine |

Nortriptyline, protriptyline, desipramine |

Antidiabetics Sulfonylureas | Gliclazide, metformin, acarbose |

Antihypertensives Beta-blockers Calcium channel blockers | Guanfacine, doxazosin Acebutolol, atenolol, betaxolol, bisoprolol, labetalol, metoprolol, nadolol, pindolol Amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, nicardipine, nifedipine, verapamil |

Anti-inflammatories Corticosteroids | NSAIDs, COX inhibitors |

| COX, cyclooxygenase; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | |

| * Table is not meant to imply equal efficacy for all choices for a given indication. | |

| † Valproic acid and carbamazepine are associated with weight gain, but less than that associated with lithium. | |

| ‡ Topiramate may not be adequate as a single agent. | |

Set a goal, prescribe a food plan

After discussing possible interventions based on the patient’s BMI and weight status (TABLE 1), set a safe and achievable goal to reduce body weight at a rate of 1 to 2 lb per week for 6 months to achieve an initial weight loss goal of up to 10%. Not only does such a target have proven health benefits,15,24 but defining success in realistic and achievable terms helps maintain patient motivation.

Although no single dietary approach has been found to have a metabolic advantage or be most likely to support long-term weight maintenance,15,25-28 energy balance is central. It is critical to induce a negative energy balance—with a deficit of 250 to 500 calories per day to achieve a weight loss of 0.5 to 2 lb per week.

Which diet is best?

Diets emphasizing varying contents of carbohydrate, fat, and protein have generally been found to be equally successful in promoting clinically meaningful weight loss and maintenance over the course of 2 years, although some studies have found specific approaches to encourage initial weight loss.26 Because different strategies have proven helpful to various patients, your best bet is to analyze the patient’s eating pattern and prescribe the diet he or she is most likely to adhere to for at least 6 months.

If the patient has comorbidities, choose the diet expected to have the greatest impact—a low-glycemic diet for an obese patient with diabetes, for example, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) food plan for a patient with hypertension.27 For premenopausal women, diets low in carbohydrates have been found to facilitate weight loss without negative health consequences.25

Offer specific—and actionable—strategies

Most clinically obese patients (63%, according to 1 study) do not receive weight loss counseling from their primary care physician. Often, they are told to lose weight, but not given advice on how to do so. Providing specific strategies can help patients stay motivated.

One set of specific weight-loss messages comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Research to Practice Series.29 Patients are advised to:

- limit eating away from home

- select healthy options when eating out

- eat more fruits and vegetables

- avoid large portion sizes

- eat low energy-dense foods (ie, foods that are high in micronutrients but low in calories per gram).

The CDC also encourages new moms to breastfeed. In addition to helping the women themselves control their weight, breastfed infants appear to be more likely to maintain a normal body weight—an important consideration as overweight children are more likely than children of normal weight to become overweight adults.30 (To learn more about pediatric obesity, see “How best to help kids lose weight”.)

The “5-3-2-1-almost none” plan offers additional advice. Every day, patients should:

- Eat ≥5 servings of fruits and vegetables