User login

What clinical clues differentiate migraine from sinus headaches?

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

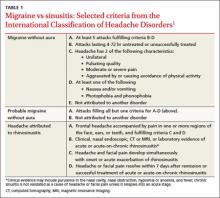

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

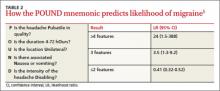

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

Patients with sinus headaches have thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath (SOR: B, cross-sectional study).

The 5 symptoms that are most predictive of migraine are: pulsatile quality, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral location, nausea or vomiting, and disabling intensity (SOR: B, retrospective cohort). As the number of these symptoms increases, so too, does the likelihood that the patient has a migraine (SOR: B, systematic review of retrospective cohort studies).

Most patients diagnosed with sinus headache actually have a migraine headache (SOR: B, 2 cross-sectional studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Clinical signs and symptoms define headache types. The International Headache Society (IHS)’s definition of migraine (which is considered the gold standard) includes many of the same symptoms associated with headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis (TABLE 1).1 In order for a headache to be attributed to rhinosinusitis, the patient must meet the definition of acute rhinosinusitis as defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS). The definition includes purulent discharge, nasal obstruction, and facial pain-pressure-fullness.

Migraine headache symptoms include nasal discharge but not purulent discharge or nasal obstruction. The IHS doesn’t accept chronic sinusitis as a cause of headaches unless the patient meets the criteria for acute rhinosinusitis.1,2

When a “sinus” headache isn’t

A cross-sectional study enrolled 100 patients (78 female, 22 male) 18 to 81 years of age who responded to an advertisement seeking people with self-diagnosed “sinus” headaches.3 A neurologist used the 2004 IHS criteria to classify the correct headache type. In 86% of patients, the investigators reclassified the patients with a migraine or probable migraine. Only 3 patients retained the sinus headache diagnosis. All 3 had at least one of the following: thick nasal discharge, fever, chills, sweats, or abnormally malodorous breath. The remaining 11 patients suffered from other headache subtypes.

The big 5 migraine symptoms

A prospective cohort study of 166 French railway employees evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of individual components of the IHS criteria. Patients enrolled had an average age of 39 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1:2. A neurologist diagnosed the headache type and placed patients into either a migraine or nonmigraine cohort. Researchers asked participants about IHS defined migraine symptoms and then compared the frequency of positive responses from migraineurs vs nonmigraineurs.

Five specific IHS criteria were found to be useful in identifying patients with migraine: duration between 4 and 72 hours (odds ratio [OR]=2.5; P=.02), unilateral location (OR=2.3; P=.03), pulsating quality (OR=2.4; P=.02), disturbance of daily activity (OR=2.5; P=.02), and nausea or vomiting (OR=2.8; P=.009). Any 4 of these features indicated a probability of migraine headache of ≥70%. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia (OR=0.5; P=.11) and aggravation by physical activity (OR=1.7; P=.14) didn’t improve diagnostic accuracy.4

A systematic review of retrospective cohort studies later analyzed the data.5 The authors derived the POUND mnemonic (TABLE 2)5 to aid clinicians in using the 5 clinical features to determine the likelihood of migraine headache. When any 4 of the 5 screening questions are positively, the likelihood ratio (LR) for migraine is 24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-388). Conversely, when 2 or fewer screening questions elicit positive responses, migraine is less likely (LR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.32-0.52).5

Most “sinus” headaches found to be migraine

A multicenter cross-sectional study evaluated 2991 male and female primary care patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who reported at least 6 self-described or physician-diagnosed sinus headaches within the preceding 6 months.6 At baseline, patients reported the following symptoms: pulsing or throbbing pain (89%), pain that worsened with physical activity (85%), sinus pressure (84%), sinus pain (82%), nasal congestion (63%), photophobia (79%), nausea (73%), and phonophobia (67%). Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of migraine, used a triptan, had a radiologic diagnosis of sinusitis, or had purulent drainage or fever.

Using the patients’ headache histories, reported symptoms, and the IHS criteria, researchers reclassified 88% of these “sinus headache” patients as having migraine type headaches.

Recommendations

IHS recommends using strict criteria for diagnosing migraines and headaches attributed to rhinosinusitis.1

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1 suppl):S8-S160.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31.

3. Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The sinus, allergy and migraine study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47:213-224.

4. Michel P, Henry P, Letenneur L, et al. Diagnostic screen for assessment of the IHS criteria for migraine by general practitioners. Cephalagia.1993;13(12suppl):S54-S59.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

6. Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1769-1772.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Rethinking antibiotics for sinusitis—again

Practice Changer

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than OTC remedies alone.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after experiencing fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly

10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his

recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in seven adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

CDC guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last seven or more days, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than seven days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the nonspecific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO–HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within two weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

A previous PURL that was based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO–HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY

Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to receive amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1

To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of seven- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving, or of < 7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past four weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1,500 mg/d, divided into three doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0 = no problem; 3 = severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥ 0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on days 3 and 10. On day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥ 0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a six-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control groups at days 3 and 10. On day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self-

reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, versus 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3 to 34; P = .02) for a reduction in symptoms at day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (< 10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW

Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥ 0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS

Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be

difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Clinicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhinosinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

REFERENCES

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2010. January 2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2012.

3. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007:137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

4. Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al; American Academy of Family Physians; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine; Centers for Disease Control; Infectious Disease Society of America. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults; background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:498-505.

5. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenk OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2008(2):CD000243.

6. Allen G, Kelsberg G, Jankowski TA. Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:714-724.

7. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.

8. Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(4):CD005149.

9. Schumann A, Hickner, J. Patients insist on antibiotics for sinusitis? Here is a good reason to say “no.” J Fam Pract. 2008;57:464-468.

10. Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371:908-914.

11. Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006;38:349-354.

12. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:735-743.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2012 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2012;61(10):610-612.

Practice Changer

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than OTC remedies alone.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after experiencing fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly

10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his

recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in seven adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

CDC guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last seven or more days, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than seven days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the nonspecific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO–HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within two weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

A previous PURL that was based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO–HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY

Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to receive amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1

To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of seven- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving, or of < 7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past four weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1,500 mg/d, divided into three doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0 = no problem; 3 = severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥ 0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on days 3 and 10. On day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥ 0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a six-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control groups at days 3 and 10. On day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self-

reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, versus 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3 to 34; P = .02) for a reduction in symptoms at day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (< 10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW

Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥ 0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS

Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be

difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Clinicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhinosinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

REFERENCES

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2010. January 2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2012.

3. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007:137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

4. Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al; American Academy of Family Physians; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine; Centers for Disease Control; Infectious Disease Society of America. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults; background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:498-505.

5. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenk OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2008(2):CD000243.

6. Allen G, Kelsberg G, Jankowski TA. Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:714-724.

7. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.

8. Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(4):CD005149.

9. Schumann A, Hickner, J. Patients insist on antibiotics for sinusitis? Here is a good reason to say “no.” J Fam Pract. 2008;57:464-468.

10. Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371:908-914.

11. Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006;38:349-354.

12. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:735-743.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2012 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2012;61(10):610-612.

Practice Changer

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than OTC remedies alone.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after experiencing fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly

10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his

recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in seven adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

CDC guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last seven or more days, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than seven days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the nonspecific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO–HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within two weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

A previous PURL that was based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO–HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY

Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to receive amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1

To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of seven- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving, or of < 7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past four weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1,500 mg/d, divided into three doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0 = no problem; 3 = severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥ 0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on days 3 and 10. On day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥ 0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a six-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control groups at days 3 and 10. On day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self-

reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, versus 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3 to 34; P = .02) for a reduction in symptoms at day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (< 10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW

Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥ 0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS

Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be

difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Clinicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhinosinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

REFERENCES

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2010. January 2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2012.

3. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007:137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

4. Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al; American Academy of Family Physians; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine; Centers for Disease Control; Infectious Disease Society of America. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults; background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:498-505.

5. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenk OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2008(2):CD000243.

6. Allen G, Kelsberg G, Jankowski TA. Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:714-724.

7. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.

8. Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(4):CD005149.

9. Schumann A, Hickner, J. Patients insist on antibiotics for sinusitis? Here is a good reason to say “no.” J Fam Pract. 2008;57:464-468.

10. Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371:908-914.

11. Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006;38:349-354.

12. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:735-743.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2012 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2012;61(10):610-612.

Rethinking antibiotics for sinusitis—again

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than over-the-counter (OTC) remedies alone.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012 ;307:685-692.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after suffering from fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly 10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in 7 adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last 7 days or more, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than 7 days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the non-specific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within 2 weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

An earlier PURL based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO-HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY: Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1 To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70 years, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of 7- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving or of <7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past 4 weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1500 mg/d, divided into 3 doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0=no problem; 3=severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at Days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at Day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a 6-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control group at Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self- reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, vs 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3-34; P= .02) for a reduction in symptoms at Day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (<10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW: Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on Day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS: Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Physicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhino-sinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2010. January 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2012.

3. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

4. Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al. American Academy of Family Physians; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine; Centers for Disease Control; Infectious Disease Society of America. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults; background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:498-505.

5. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenk OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000243.-

6. Allen G, Kelsberg G, Jankowski TA. Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:714-724.

7. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.

8. Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD005149.-

9. Schumann A, Hickner J. Patients insist on antibiotics for sinusitis? Here is a good reason to say “no”. J Fam Pract. Jul:2008;57:464-468.

10. Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371:908-914.

11. Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006;38:349-354.

12. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743.

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than over-the-counter (OTC) remedies alone.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012 ;307:685-692.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after suffering from fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly 10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in 7 adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last 7 days or more, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than 7 days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the non-specific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within 2 weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

An earlier PURL based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO-HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY: Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1 To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70 years, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of 7- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving or of <7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past 4 weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1500 mg/d, divided into 3 doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0=no problem; 3=severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at Days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at Day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a 6-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control group at Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self- reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, vs 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3-34; P= .02) for a reduction in symptoms at Day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (<10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW: Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on Day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS: Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Physicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhino-sinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Stop prescribing amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis. It’s unlikely to provide a speedier recovery than over-the-counter (OTC) remedies alone.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single high-quality randomized controlled trial.

Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012 ;307:685-692.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old man comes to your clinic after suffering from fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, and unilateral facial pain for nearly 10 days. Overall, he appears healthy, and you diagnose acute rhinosinusitis. You suggest OTC remedies for supportive care and wonder if a course of amoxicillin would speed his recovery.

Each year, more than 30 million Americans—about one in 7 adults—are diagnosed with sinusitis.2 No more than 2% of these cases are thought to be bacterial.3

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include symptoms that last 7 days or more, with maxillary pain or tenderness in the face or teeth and purulent nasal secretions.4 Patients with symptoms lasting less than 7 days are unlikely to have a bacterial infection. But the non-specific signs and symptoms included in the CDC guidelines limit their usefulness in determining whether the cause of the sinusitis is bacterial or viral on clinical grounds alone.

Most cases of sinusitis spontaneously resolve

In patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guidelines advocate watchful waiting and symptom relief with nasal oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and saline nasal irrigation.3 The rate of spontaneous resolution is high: 80% of patients with clinically diagnosed sinusitis improve without treatment within 2 weeks.1,5

Traditional decongestants and mucolytics have not demonstrated efficacy in resolving sinusitis, although rigorous evaluation is lacking. Other treatments, such as saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids, are of unclear benefit and need further study.6-8

Lack of evidence has done little to curtail antibiotic use

An earlier PURL based on a meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment trials for sinusitis recommended that we stop prescribing antibiotics for adults with acute sinusitis unless their symptoms are severe.9,10 Yet antibiotics remain the mainstay of treatment.

Despite the AAO-HNS guidelines, evidence of spontaneous resolution, and accumulating data on the lack of efficacy of antimicrobials for sinusitis, 81% of patients diagnosed with acute sinusitis were given prescriptions for antibiotics, a study of primary care practices showed.11 Frequent use of antibiotics contributes to high rates of drug resistance, and adverse events related to antibiotic use account for an estimated 142,500 emergency department visits annually.12

STUDY SUMMARY: Little benefit from amoxicillin, even for severe cases

Garbutt and colleagues revisited the issue, randomizing 166 patients from 10 primary care practices to amoxicillin plus symptomatic treatment or placebo plus symptomatic treatment for acute rhinosinusitis.1 To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 70 years, meet CDC diagnostic criteria for acute rhinosinusitis, and have moderate to very severe symptoms that were of 7- to-28-day duration and worsening or not improving or of <7-day duration but had worsened after an initial improvement. Exclusion criteria included complications from sinusitis, a history of allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, antibiotic use in the past 4 weeks, comorbidities that impair immune function, cystic fibrosis, pregnancy, and mild symptoms.

Both groups had similar baseline characteristics, with participants who were predominantly white (79%) and female (64%). All the participants received a supply of symptomatic treatments: acetaminophen, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, and sustained-release pseudoephedrine. The treatment group also received amoxicillin 1500 mg/d, divided into 3 doses; the placebo group received identical-looking placebo pills.

Patients were assessed with the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-16 (SNOT-16), a validated measure that asks patients to assess both the severity and frequency of 16 sinus symptoms. SNOT-16 uses a 0-to-3 rating scale (0=no problem; 3=severe problem), with a clinically important difference of ≥0.5 on the mean score. The test was administered at enrollment and at Days 3, 7, and 10. The disease-specific quality of life at Day 3 was the primary outcome.

There was no statistically significantly difference in SNOT-16 scores between the amoxicillin and placebo groups on Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, there was a small statistically significant improvement in the amoxicillin group, but it did not reach the level of clinical importance (≥0.5) based on SNOT-16’s mean score.

The authors also asked participants to retrospectively assess symptom change since enrollment on a 6-point scale. Those who reported that their symptoms were “a lot better” or “absent” were characterized as significantly improved. The results correlated with the data from the SNOT-16, showing no difference between the amoxicillin and control group at Days 3 and 10. On Day 7, 74% of patients treated with amoxicillin self- reported significant improvement in symptoms since the start of the study, vs 56% in the control group. The number needed to treat was 6 (95% confidence interval, 3-34; P= .02) for a reduction in symptoms at Day 7.

Patients in both groups had similar rates of absenteeism, inability to perform usual activities, relapse and recurrence, and use of additional health care. Satisfaction with treatment was similar, as well.

No serious adverse effects occurred. Both groups reported similar frequencies (<10%) of nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or vaginitis.

WHAT’S NEW: Even severe sinusitis resolves without antibiotics

Previous studies recommended foregoing antibiotics for acute sinusitis, except when symptoms are severe. This study—in which more than half (52%) of patients in each group had symptoms rated severe or very severe—found no benefit to adding amoxicillin to supportive treatments.1 Antibiotics did not shorten the duration of illness, prevent relapse and recurrence, or improve satisfaction with treatment. The researchers found a statistically significant difference between groups on Day 7 of 0.19 points, but no clinically meaningful difference (≥0.5) based on the SNOT-16 mean score.

CAVEATS: Guidelines, risk of complications may give reason to pause

The 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as empiric therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.7 The findings of the study by Garbutt et al—conducted at a time when the incidence of beta-lactamase-producing organisms was low and amoxicillin was the treatment of choice—suggest otherwise.

Serious complications of sinusitis, such as brain abscess, periorbital cellulitis, and meningitis, can occur, however. Patients who deteriorate clinically or develop high fever or severe headache require close follow-up, which may include further diagnostic evaluation or consultation with an otolaryngologist. Evidence is lacking as to whether antibiotics prevent such complications.5

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Managing patient expectations

Many patients with symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis think they need an antibiotic. Managing their expectations and providing instructions about supportive treatments are time consuming and may be difficult.

Nonetheless, we’re optimistic: We think that most patients today are aware of the problems associated with antibiotic resistance and wary of “superbugs,” and will therefore be receptive to this practice change. Physicians can help by reminding patients of the adverse effects of antibiotics and the natural course of rhino-sinusitis, as well as by offering symptomatic treatments.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2010. January 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2012.

3. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1-S31.

4. Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al. American Academy of Family Physians; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine; Centers for Disease Control; Infectious Disease Society of America. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults; background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:498-505.

5. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenk OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000243.-

6. Allen G, Kelsberg G, Jankowski TA. Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:714-724.

7. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.

8. Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD005149.-

9. Schumann A, Hickner J. Patients insist on antibiotics for sinusitis? Here is a good reason to say “no”. J Fam Pract. Jul:2008;57:464-468.

10. Young J, De Sutter A, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for adults with clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2008;371:908-914.

11. Gill JM, Fleischut P, Haas S. Use of antibiotics for adult upper respiratory infections in outpatient settings: a national ambulatory network study. Fam Med. 2006;38:349-354.

12. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743.

1. Garbutt J, Banister C, Spitznagel E, et al. Amoxicillin for acute rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:685-692.