User login

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

Suicide prevention is the leading clinical priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 An average of 18 veterans died by suicide each day in 2021.2 Numerous risk factors for veteran suicide have been identified, including mental health disorders, comorbidities, access to firearms, and potentially lethal medications.3-5 To better understand groups of patients at risk of suicide in medical settings, the authors have previously compared demographic and clinical risk factors between patients who died by suicide by using firearms or other means with matched patients who did not die by suicide (control group) to examine the impact of lack of social support, financial stress,6 legal problems,7 homelessness,8 and discrimination.9 The number of cooccurring risk factors a veteran experiences is associated with a greater likelihood of suicide attempts over time.10 In addition, some risk factors are social and environmental risk factors known as social determinants of health (SDoH), including financial stability and access to health care, food, housing, and education. 11 SDoH may influence health outcomes more broadly and are associated with greater risk of suicide.12,13

The VA offers programming to address suicide risk factors. However, not all veterans are eligible for VA care. Further, some veterans prefer to obtain non-VA services in their communities. Providing veterans with community resources that address risk factors, particularly SDoH, may be a worthwhile strategy for reducing suicide. Such resources have demonstrated success; for example, greater use of housing services was associated with a reduced risk for suicide-related mortality among unhoused veterans.12

The challenges that veterans experience can go beyond the scope of services the VA provides. For example, while the VA provides some services related to homelessness, justice involvement, and assistance with home loans, these services are often limited. Other services for veterans to address SDoH may require access to community resources, including food banks, employment assistance, respite and childcare services, and transportation assistance. Some veterans also may have experienced institutional betrayal, which could be a barrier to VA care and may motivate veterans to address their needs in the community.14 Veterans therefore may need a range of services beyond those within the VA. Leveraging community resources for veterans at risk for suicide is critical, as these resources may help to mitigate suicide risk.

An emerging emphasis of the VA is improving coordination with community partners to prevent veteran suicide. In 2019, the VA launched an improved Veterans Community Care Program, which implemented portions of the VA MISSION Act of 2018 to create additional connection to community care for VA-enrolled veterans. This includes assisting veterans in gaining access to specialty services not offered at a local VA medical center (VAMC), getting access to services sooner, and receiving care if they do not live near a VAMC.15 In addition, the COMPACT Act allows veterans in acute suicidal crisis to receive emergency health care through either VA or non-VA facilities at no cost.16 The VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028 is a 10-year plan to reduce veteran suicide rates that includes initiatives to increase connections between VA and community agencies.17 A suicide prevention community toolkit is available online for health care professionals (HCPs) (and others, including employers) outside of the VA who may be unfamiliar with best practices for working with veterans at risk for suicide.18

The challenge, however, is that there is often a lack of “connectedness” between VA suicide prevention coordinators and community resources to address suicide risk factors and related social determinants of health. These services include, but are not limited to suicide prevention, mental health counseling (particularly no/low-cost services), unemployment resources, financial assistance and counseling, housing assistance, and identity-related supportive spaces. A major stumbling block in connecting resources with veterans (regardless of discharge status) who need them is there is no single, national organization with a comprehensive, community-based network that can serve in this intermediary role.

Community asset mapping (CAM), also known as asset mapping or environmental scanning, is a way to bridge the gap.19 CAM provides a method for identifying and aligning community resources relative to a specific need.20 CAM may be used to build community relationships in service of veteran suicide prevention. This process can help individuals learn about and make use of organizations and services within their communities. CAM also helps connect HCPs so they can network, exchange ideas, and collaborate with an eye toward increasing the availability of services and enhancing care coordination. CAM also allows community members (eg, leaders, organizations, individuals) to identify possible gaps in services that address suicide risk factors and solve these problems.

This article details CAM for suicide prevention, which can be utilized by the VA and community organizations alike. Within the VA, CAM can be used by HCPs and administrators, such as VA community engagement and partnership coordinators, to identify potential partnering organizations. For those who serve veterans outside of the VA, CAM can be used to connect at-risk individuals to resources that can enhance their care. This process can help increase the overall knowledge of, and access to, community resources.

COMMUNITY ASSET MAPPING

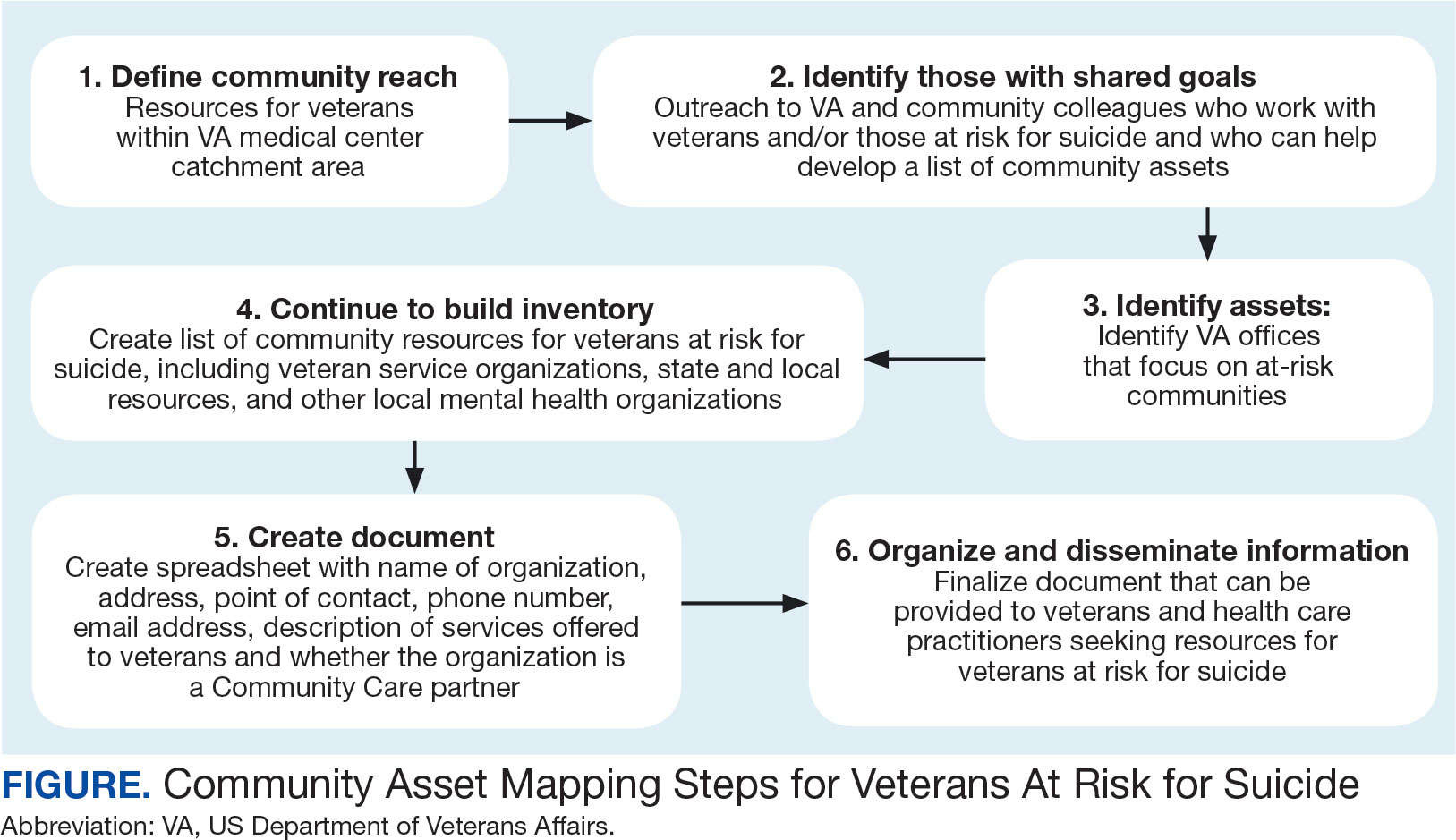

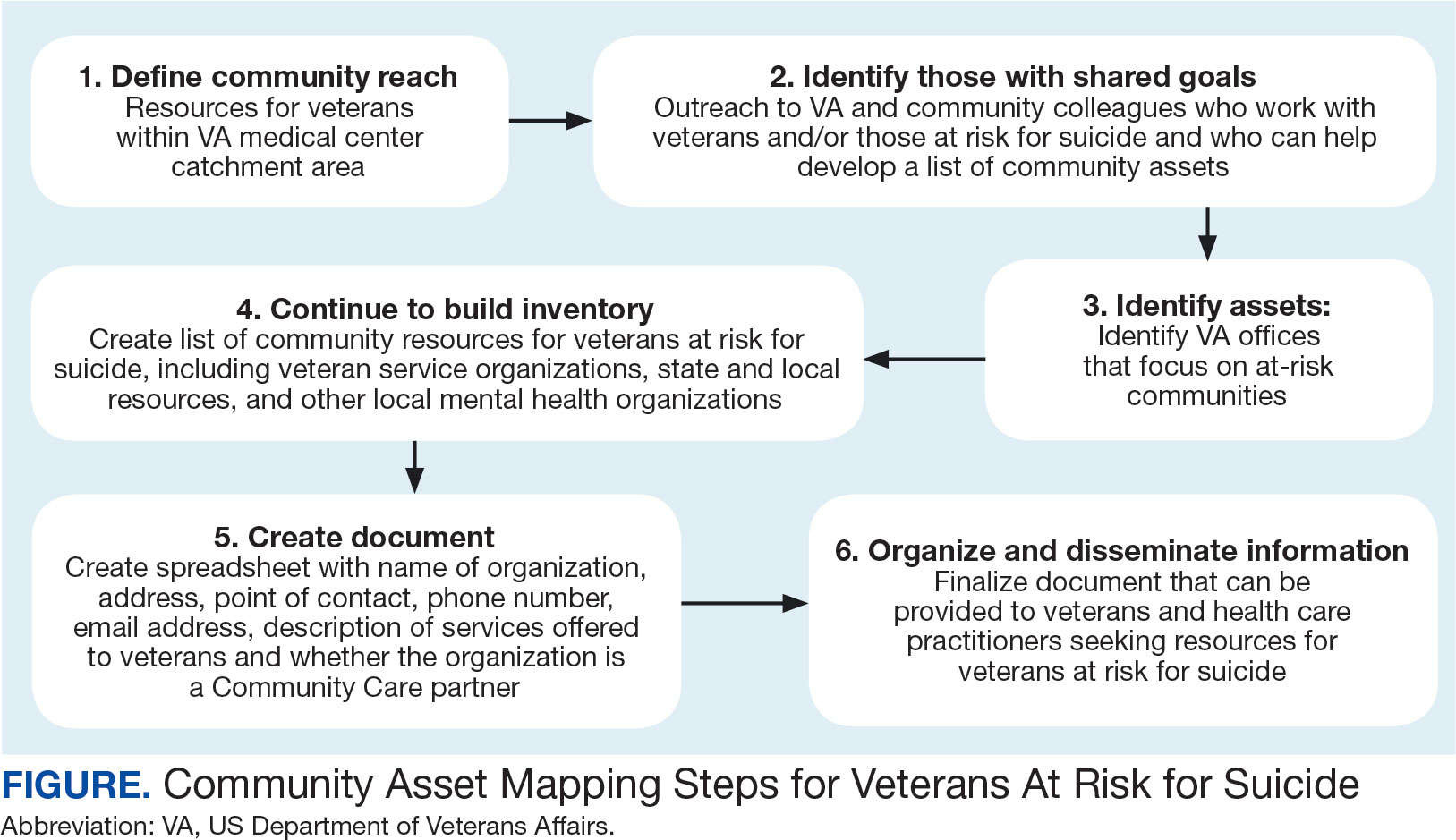

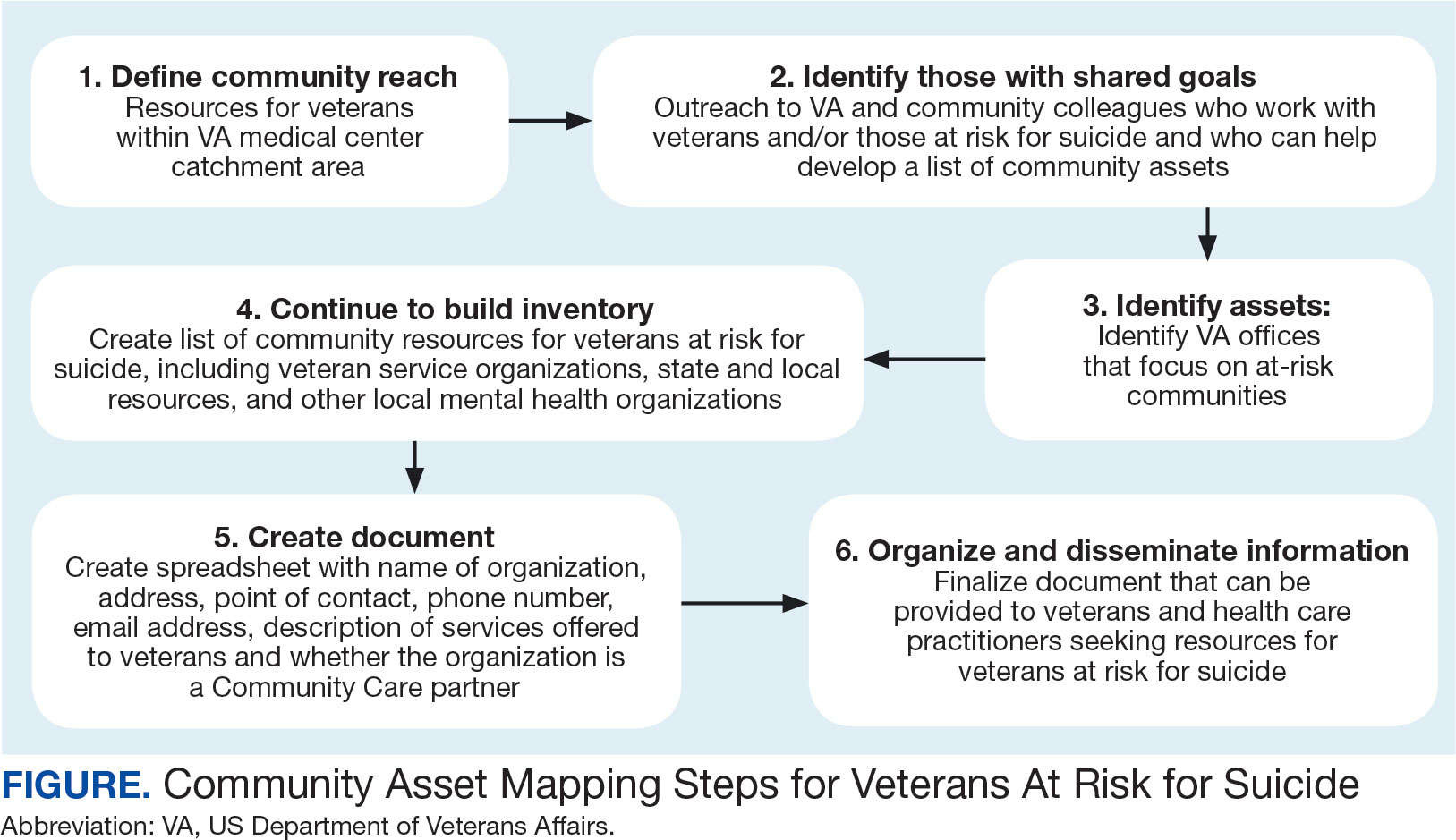

The University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research provides 6 steps for the CAM process.21 These steps include: (1) defining the boundaries of people and places that comprise the community; (2) identifying people and organizations who share similar interests and goals; (3) determining the assets to include; (4) creating an inventory of all organizations’ assets; (5) creating an inventory of individuals’ assets; and (6) organizing the assets on a map. To address the needs of the veteran population, we’ve taken these 6 steps and adapted them to create a CAM for veterans at risk for suicide (Figure). The discussion that follows details how these steps can be implemented to identify community resources that address social determinants of health that may contribute to suicide risk. The goal is to prevent veteran suicide.

Step 1: Define Community Reach. The first step is to identify the geographical boundaries of the community. This may include all veterans within a catchment area (eg, veterans within 60 miles of a VAMC). Defining the geographical parameters of the community will provide structure to the effort so that the resource list is as comprehensive as possible.

Steps 2 and 3: Identify Community Members with Shared Goals; Identify Assets. It is important to identify community members who share similar interests and goals, including people with specific knowledge and skills, organizations with particular goals, and community partners with a broad reach. To begin building a list of referrals, reach out to colleagues within the VA system who are familiar with community resources for those with suicide risk factors. The local VA Transition and Care Management (TCM) office is a resource that connects those transitioning from military to civilian sectors with needed resources, and thus may be a helpful resource while building a CAM. Additionally, each office has a transition patient advocate, who is trained to resolve care-related concerns and may be familiar with community resources.

VA HCPs that can assist include Community Engagement and Partnership Coordinators, Suicide Prevention Coordinators, Local Recovery Coordinators, and substance abuse counselors. In addition, VA patient services, patient safety, and public affairs office staff—as well as VA Homeless Programs—may be good resources. Every VA health care system has care coordinators focused on military sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ care. These care coordinators may be able to provide information on community resources that address social determinants of health (eg, discrimination, violence).

Reaching out to key community resources and asking for recommendations of other groups that provide assistance to veterans can also be productive. You can start by connecting with veterans service organizations (VSOs), Vet Centers, Veterans Experience Offices (VEO), and Community Veterans Engagement Boards (CVEBs). The VEO is an office designed around VA and community engagement efforts. This office utilizes the CVEBs to foster a 2-way communication feedback loop between veterans and local VA facilities regarding community engagement efforts and outreach.22 CVEBs are particularly valuable sources of information because veterans directly contribute to the conversation about community engagement by describing the difficulties and successes they’ve experienced. Veteran feedback about how a particular resource met their needs can inform which community services are prioritized for inclusion in the resource list. In addition, CVEBs may have a listing of local government, military, and/or community resources that provide services for veterans. Consider, too, organizations that are unrelated to an individual’s veteran status, but speak to their race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, spirituality, socioeconomic status, or disability.

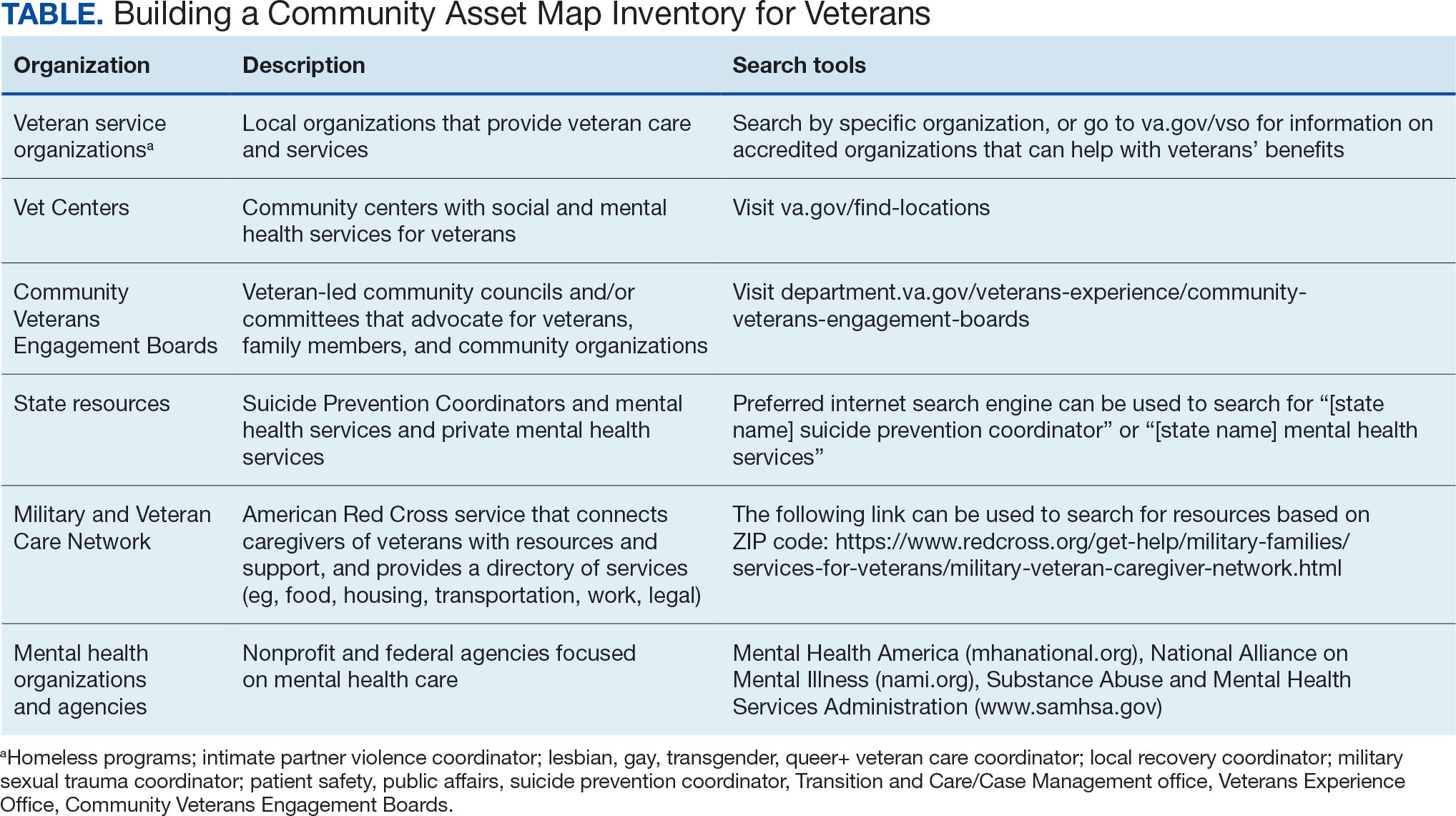

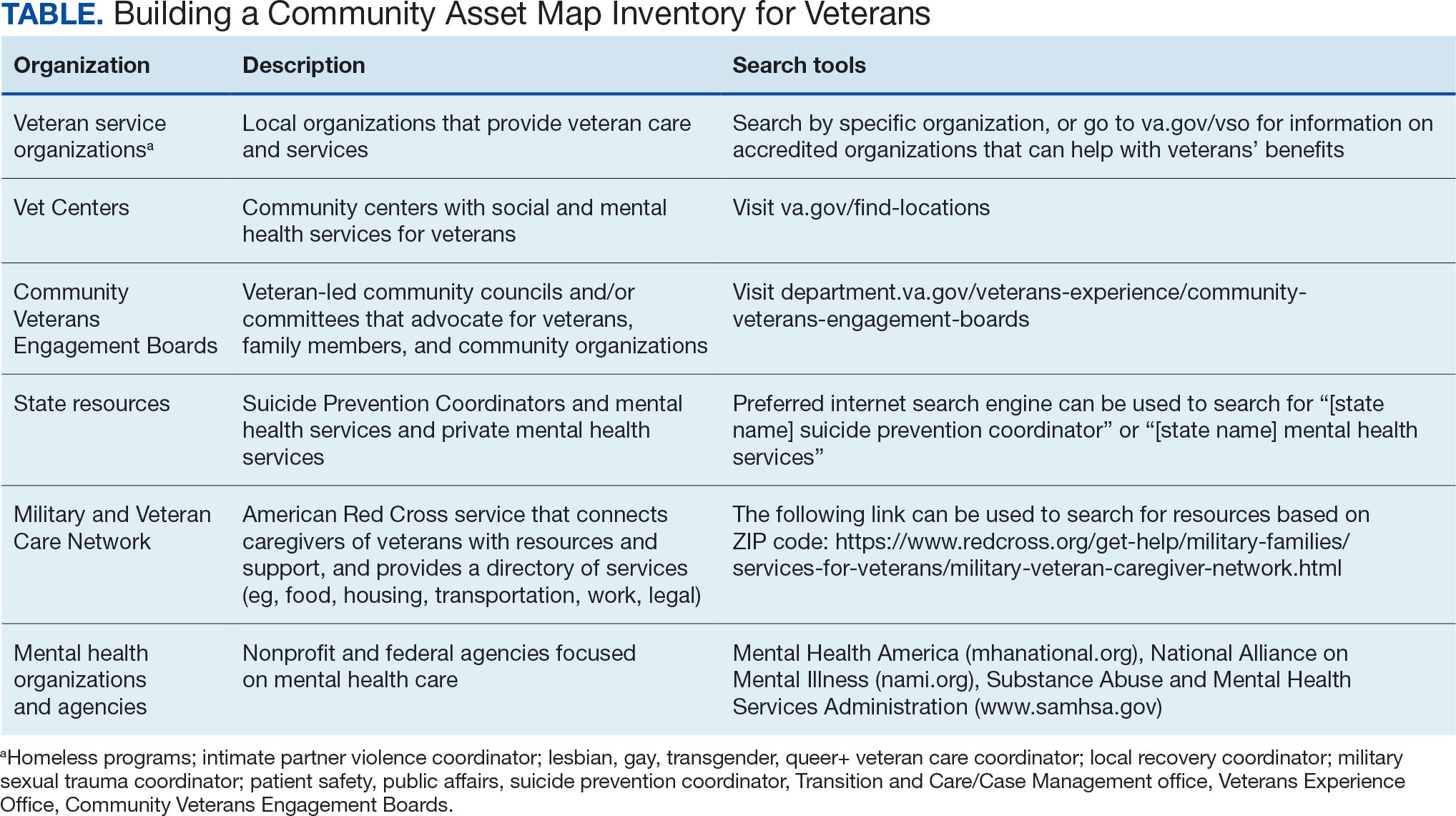

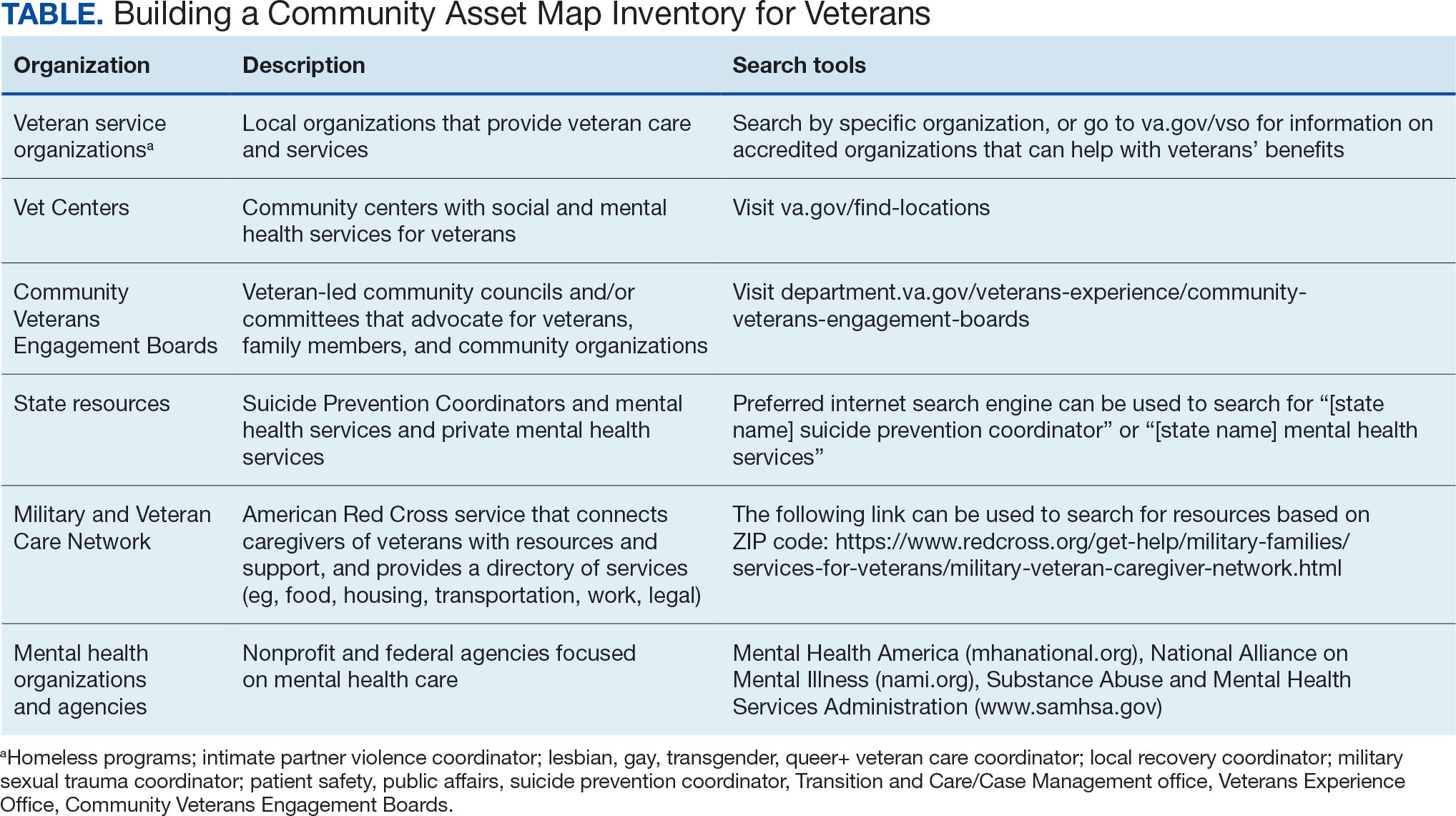

Step 4: Continue to Build Inventory. Use online searches to identify additional resources in the community that are known to have local relationships. These include state suicide prevention coordinators, mental health organizations, and other resources that address social determinants of health (eg, public health and human service organizations, faith-based organizations, collegial organizations). A list of links and search tips are available in the Table.

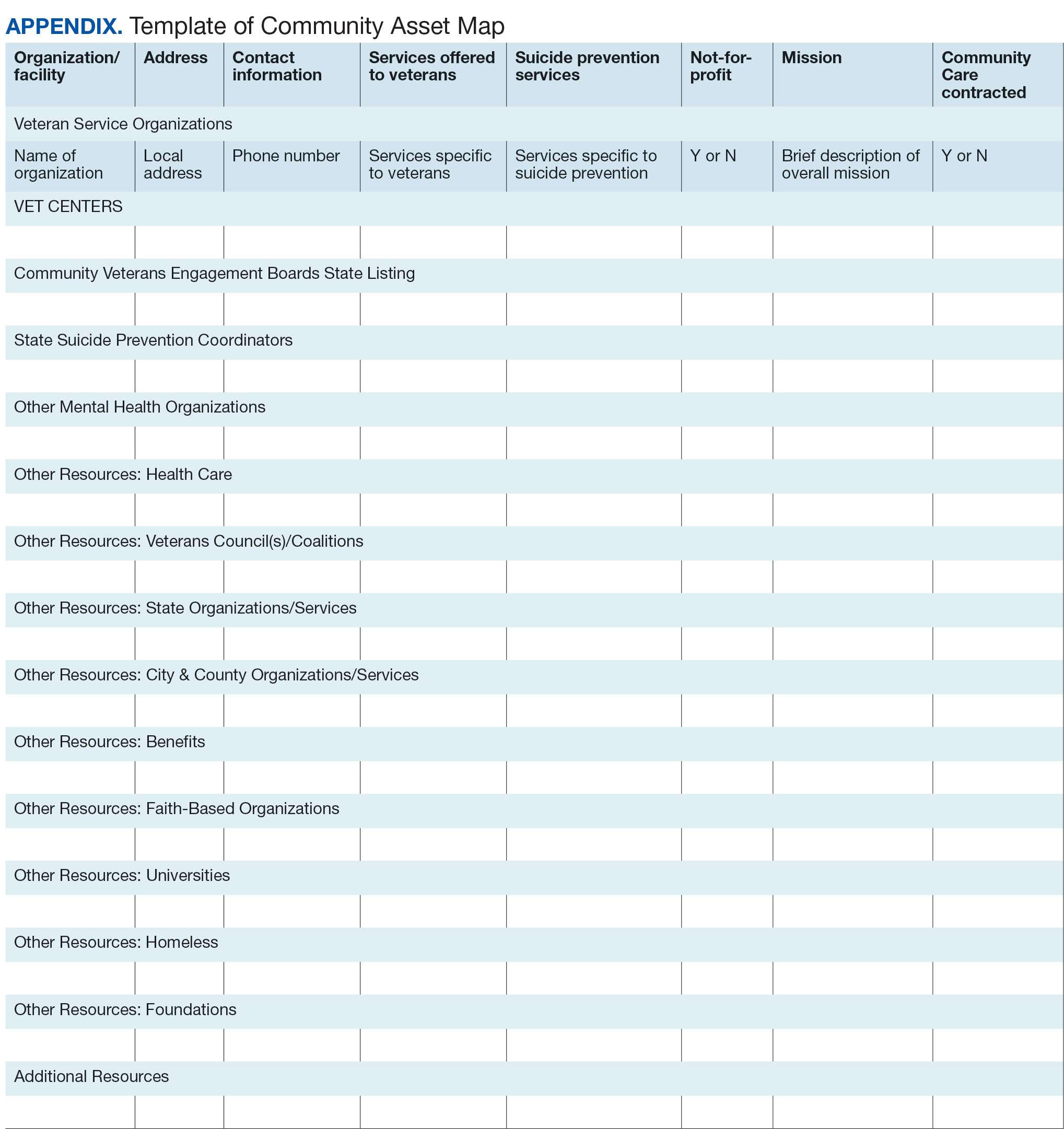

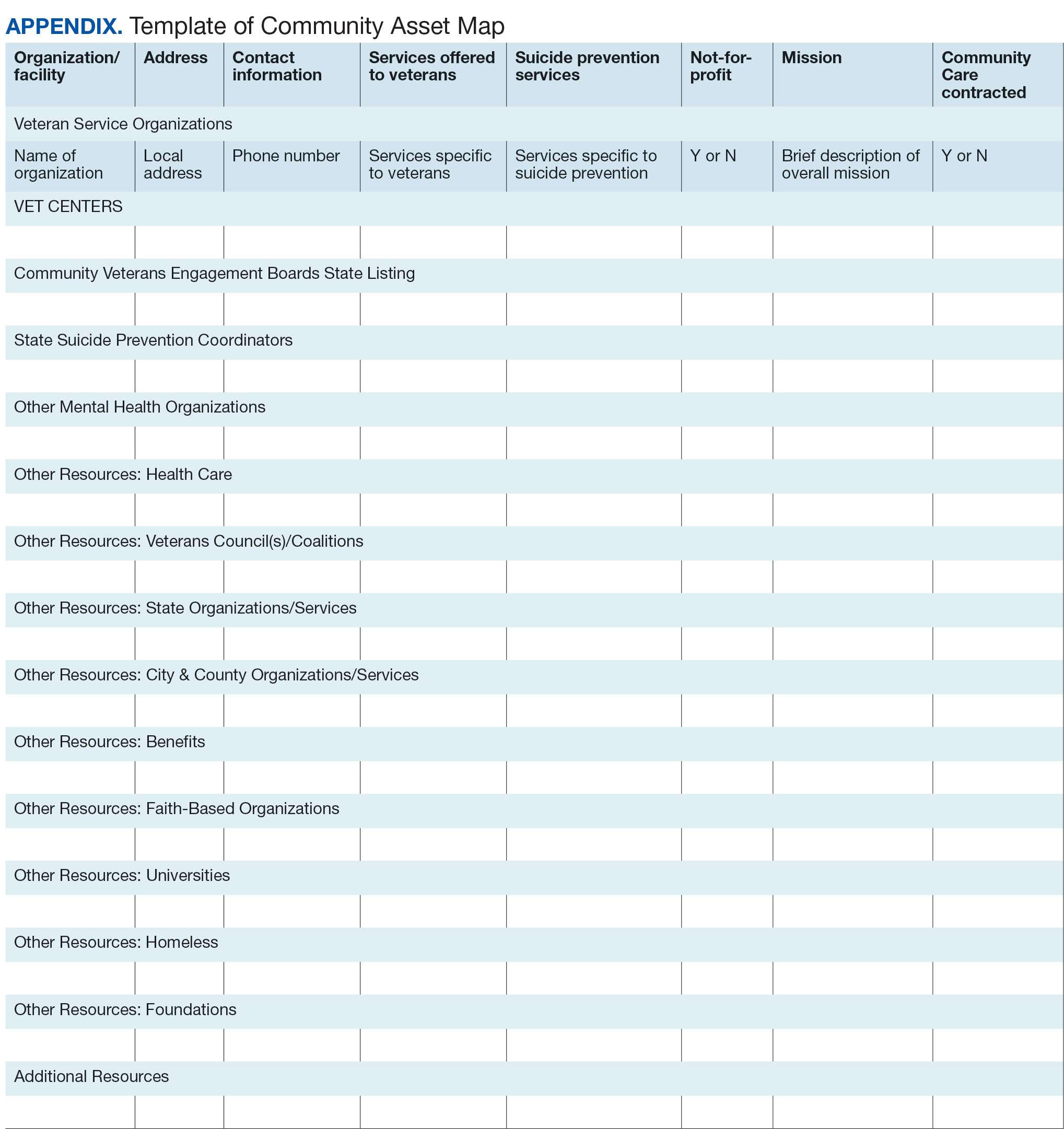

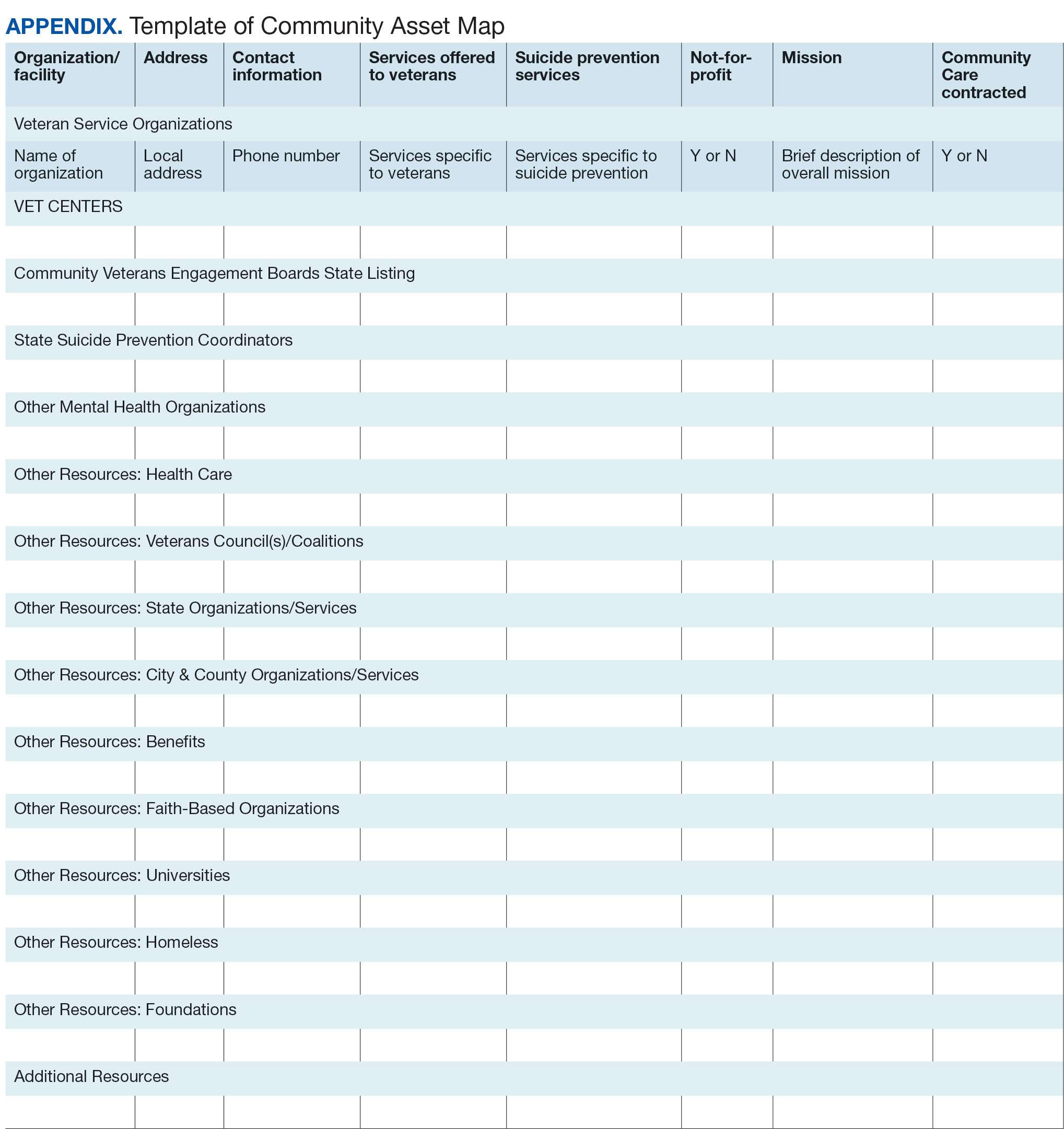

Steps 5 and 6: Create Document; Organize and Disseminate Information. A spreadsheet can be used to document organization information (Appendix). It is critical to record: (1) the name of the organization or individual; (2) the local address and a point of contact with contact information; (3) services offered to veterans; (4) services specific to suicide prevention, or that address risk factors for suicide; and (5) whether the referral organization is partnered with the VA Community Care Network, which is comprised of contracted HCPs who contract with the VA to provide care to veterans.23

Once a document is created, it can be disseminated through VA offices and among community partners who work with veterans at risk for suicide. It should also be stored in a centralized location such as a shared folder so that it can be continuously updated.

Regularly updating the list is vital so the resource list can continue to be helpful in addressing veterans’ needs and reducing suicide risk factors. Continued collaboration with those in the community can help ensure the resource list is up to date with all available services and pertinent contact information. It can also go far in strengthening collaborative bonds.

IMPLEMENTATION

To illustrate the use of CAM for veteran suicide prevention, we offer a case example of CAM conducted by the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry — Suicide Prevention Collaborative (VA PSCI-SPC) team, consisting of 4 team members. A veteran was included as a team member and assisted with the CAM process.

The VA PSCI-SPC sought to identify community services for veterans in Colorado who were not enrolled in VA health care and had risk factors for suicide. Next, the team reached out to colleagues and asked about community organizations that work with individuals at risk for suicide. VA PSCI-SPC outreach resulted in a list of assets that included resources to address mental health, legal concerns, employment, homelessness/housing, finances, religion, peer support, food insecurity, exercise, intimate partner violence, sexual and gender identity needs, and peer support. VSOs and CVEBs were also added to the list.

Next, the team continued to build on the inventory and identified state suicide prevention coordinators; health care systems; regional suicide prevention commissions; Colorado Department of Health and Human Services; program coordinators for Governor’s and Mayor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families; veterans councils; universities (eg, counseling clinics, legal clinics); and foundations devoted to general and veteran-specific suicide prevention within the region.

All the identified resources were inventoried. Details were gathered about each of the organizations, including addresses, points of contact and phone numbers, descriptions of services offered for veterans, descriptions of suicide prevention services offered, whether or not organizations were not-for-profit, the mission of the organizations, and whether or not the organizations were under contract for VA Community Care. Finally, the resource spreadsheet was created and disseminated among stakeholders to be used to enhance veteran suicide care. Stakeholders included social workers, psychologists, and nurse practitioners working with veterans. The list was circulated to VA and community partners as needed.

The VA PSCI-SPC resource document was only 1 benefit of CAM. The asset mapping also resulted in the creation of a learning collaborative comprised of VA and community partners, designed to share knowledge of best practices in suicide prevention and create an established referral network for veterans at risk for suicide.24 Ultimately, the goal of the CAM and the creation of the learning collaborative was to better connect veterans to care in order to decrease suicide risk. A secondary benefit of this community connectedness is that the list of resources produced by CAM became a living document that was, and continues to be, updated as the network became aware of new resources and resources that were no longer available. The VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative met quarterly to discuss implementation of suicide prevention best practices within their organization.

Data from the VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative via CAM revealed that organizations felt more efficacious in implementing suicide prevention best practices, noticed increased connections and collaborations with community organizations with the goal of providing services to veterans, and resulted in staff training that improved services provided to veterans.24 This is supported by other findings of a literature review of suicide prevention interventions, which indicated that programs with an established community support network were more effective at reducing suicide rates.25 CAM therefore may be a process through which greater community connection and increased knowledge of resources may help prevent suicide among veterans.

It seems reasonable that the CAM processes used by the VA PSCI-SPC can be implemented within the regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks to identify assets in a specific geographical area to address challenges with social determinants of health and potentially decrease veteran suicide risk.

CONCLUSIONS

CAM can be used to identify and build relationships with community resources that address the stressors that place veterans at risk for suicide. Six proposed steps to CAM for veterans at risk for suicide include: defining community reach (the map); identifying community members and organizations with shared goals; identifying assets within the community; continuing to build inventory; creating a document; and organizing and disseminating the information (while continuing to update the resources).21

CAM can be used to connect veterans with resources to address needs related to adverse social determinants of health that may heighten their risk for suicide. For example, veterans facing legal challenges can connect with a legal clinic; those having difficulties paying bills can obtain financial assistance; those who need help completing their VA claims can connect with the Veterans Benefits Administration or VSOs to assist them with their claims; and those experiencing discrimination can connect with organizations where they may experience acceptance, safety, and support. Broad community support surrounding suicide risk factors can be critical for effective suicide prevention.25

CAM may also be helpful for HCPs and others involved in veteran health care. For example, community mapping can be utilized by newly hired community engagement and partnership coordinators as a tool for outlining resources available for veterans in their community and as a framework to continually update their resource network. CAM develops community awareness, integrates resources, and enhances service utilization, which may assist in veteran suicide prevention by increasing care coordination.17 Finally, mapping community resources can create awareness of the many resources available to help veterans, even before suicide becomes a consideration.

- Rice L. VA Secretary Robert Wilkie says suicide prevention is his agency’s top ‘clinical’ priority. June 17, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.kut.org/post/va-secretary-robert-wilkie-says-suicide-prevention-his-agencys-top-clinical-priority

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2023 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. November 2023. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Kittel JA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. Psychological inflexibility predicts of suicidal ideation over time in veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(6):627–641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12388

- Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB, Ignacio RV, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129

- Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. A 12-month prospective study of the effects of PTSD-depression comorbidity on suicidal behavior in Iraq/ Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:97–99. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011

- Hoffmire CA, Borowski S, Vogt D. Contribution of veterans’ initial post-separation vocational, financial, and social experiences to their suicidal ideation trajectories following military service. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(3):443- 456. doi:10.1111/sltb.12955

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs suicide prevention among veterans experiencing homelessness workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 2):S103- S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399

- Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social supsupport and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

- Lee DJ, Kearns JC, Wisco BE, et al. A longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7): 609-618. doi:10.1002/da.22736

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH). Accessed January 30, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Montgomery AE, Dichter M, Byrne T, Blosnich J. Intervention to address homelessness and all-cause and suicide mortality among unstably housed US veterans, 2012- 2016. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:380-386. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214664

- Llamocca EN, Yeh HH, Miller-Matero LR, et al. Association between adverse social determinants of health and suicide death. Med Care. 2023;61(11):744-749. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001918

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Schneider AL, et al. Institutional betrayal and help-seeking among women survivors of military sexual trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):814-823. doi:10.1037/tra0001027

- VA launches new health care options under MISSION Act. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. June 6, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5264

- COMPACT Act expands free emergency suicide care for veterans. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 1, 2023. Accessed January 31,2025. https://www.va.gov/poplar-bluff-health-care/news-releases/compact-act-expands-free-emergency-suicide-care-for-veterans/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing Veteran suicide 2018-2028. 2018. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran outreach toolkit: preventing veteran suicide is everyone’s business. A community call to action. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://floridavets.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/VA-Suicide-Prevention-Community-Outreach-Toolkit.pdf

- Crane K, Mooney M. Essential tools: community resource mapping. 2005. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/172995/NCSET_EssentialTools_ResourceMapping.pdf

- Community Tool Box. 2. Assessing Community Needs and Resources. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/assessing-community-needs-and-resources

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Section 1: asset mapping. 2012. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/programs/healthdata/trainings/documents/tw_cba20.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Experience Office. 4th quarter 2018 community engagement news. October 2, 2018. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USVAVEO/bulletins/211836e

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. About our VA community care network and covered services. Accessed February 6, 2025. https://www.va.gov/resources/aboutour-va-community-care-network-and-covered-services/

- DeBeer B, Mignogna J, Borah E, et al. A pilot of a veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative among community organizations: Initial results and outcomes. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(4):628-641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12969

- Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Rihmer Z. Suicide prevention programs through community intervention. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):10–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.009

Suicide prevention is the leading clinical priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 An average of 18 veterans died by suicide each day in 2021.2 Numerous risk factors for veteran suicide have been identified, including mental health disorders, comorbidities, access to firearms, and potentially lethal medications.3-5 To better understand groups of patients at risk of suicide in medical settings, the authors have previously compared demographic and clinical risk factors between patients who died by suicide by using firearms or other means with matched patients who did not die by suicide (control group) to examine the impact of lack of social support, financial stress,6 legal problems,7 homelessness,8 and discrimination.9 The number of cooccurring risk factors a veteran experiences is associated with a greater likelihood of suicide attempts over time.10 In addition, some risk factors are social and environmental risk factors known as social determinants of health (SDoH), including financial stability and access to health care, food, housing, and education. 11 SDoH may influence health outcomes more broadly and are associated with greater risk of suicide.12,13

The VA offers programming to address suicide risk factors. However, not all veterans are eligible for VA care. Further, some veterans prefer to obtain non-VA services in their communities. Providing veterans with community resources that address risk factors, particularly SDoH, may be a worthwhile strategy for reducing suicide. Such resources have demonstrated success; for example, greater use of housing services was associated with a reduced risk for suicide-related mortality among unhoused veterans.12

The challenges that veterans experience can go beyond the scope of services the VA provides. For example, while the VA provides some services related to homelessness, justice involvement, and assistance with home loans, these services are often limited. Other services for veterans to address SDoH may require access to community resources, including food banks, employment assistance, respite and childcare services, and transportation assistance. Some veterans also may have experienced institutional betrayal, which could be a barrier to VA care and may motivate veterans to address their needs in the community.14 Veterans therefore may need a range of services beyond those within the VA. Leveraging community resources for veterans at risk for suicide is critical, as these resources may help to mitigate suicide risk.

An emerging emphasis of the VA is improving coordination with community partners to prevent veteran suicide. In 2019, the VA launched an improved Veterans Community Care Program, which implemented portions of the VA MISSION Act of 2018 to create additional connection to community care for VA-enrolled veterans. This includes assisting veterans in gaining access to specialty services not offered at a local VA medical center (VAMC), getting access to services sooner, and receiving care if they do not live near a VAMC.15 In addition, the COMPACT Act allows veterans in acute suicidal crisis to receive emergency health care through either VA or non-VA facilities at no cost.16 The VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028 is a 10-year plan to reduce veteran suicide rates that includes initiatives to increase connections between VA and community agencies.17 A suicide prevention community toolkit is available online for health care professionals (HCPs) (and others, including employers) outside of the VA who may be unfamiliar with best practices for working with veterans at risk for suicide.18

The challenge, however, is that there is often a lack of “connectedness” between VA suicide prevention coordinators and community resources to address suicide risk factors and related social determinants of health. These services include, but are not limited to suicide prevention, mental health counseling (particularly no/low-cost services), unemployment resources, financial assistance and counseling, housing assistance, and identity-related supportive spaces. A major stumbling block in connecting resources with veterans (regardless of discharge status) who need them is there is no single, national organization with a comprehensive, community-based network that can serve in this intermediary role.

Community asset mapping (CAM), also known as asset mapping or environmental scanning, is a way to bridge the gap.19 CAM provides a method for identifying and aligning community resources relative to a specific need.20 CAM may be used to build community relationships in service of veteran suicide prevention. This process can help individuals learn about and make use of organizations and services within their communities. CAM also helps connect HCPs so they can network, exchange ideas, and collaborate with an eye toward increasing the availability of services and enhancing care coordination. CAM also allows community members (eg, leaders, organizations, individuals) to identify possible gaps in services that address suicide risk factors and solve these problems.

This article details CAM for suicide prevention, which can be utilized by the VA and community organizations alike. Within the VA, CAM can be used by HCPs and administrators, such as VA community engagement and partnership coordinators, to identify potential partnering organizations. For those who serve veterans outside of the VA, CAM can be used to connect at-risk individuals to resources that can enhance their care. This process can help increase the overall knowledge of, and access to, community resources.

COMMUNITY ASSET MAPPING

The University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research provides 6 steps for the CAM process.21 These steps include: (1) defining the boundaries of people and places that comprise the community; (2) identifying people and organizations who share similar interests and goals; (3) determining the assets to include; (4) creating an inventory of all organizations’ assets; (5) creating an inventory of individuals’ assets; and (6) organizing the assets on a map. To address the needs of the veteran population, we’ve taken these 6 steps and adapted them to create a CAM for veterans at risk for suicide (Figure). The discussion that follows details how these steps can be implemented to identify community resources that address social determinants of health that may contribute to suicide risk. The goal is to prevent veteran suicide.

Step 1: Define Community Reach. The first step is to identify the geographical boundaries of the community. This may include all veterans within a catchment area (eg, veterans within 60 miles of a VAMC). Defining the geographical parameters of the community will provide structure to the effort so that the resource list is as comprehensive as possible.

Steps 2 and 3: Identify Community Members with Shared Goals; Identify Assets. It is important to identify community members who share similar interests and goals, including people with specific knowledge and skills, organizations with particular goals, and community partners with a broad reach. To begin building a list of referrals, reach out to colleagues within the VA system who are familiar with community resources for those with suicide risk factors. The local VA Transition and Care Management (TCM) office is a resource that connects those transitioning from military to civilian sectors with needed resources, and thus may be a helpful resource while building a CAM. Additionally, each office has a transition patient advocate, who is trained to resolve care-related concerns and may be familiar with community resources.

VA HCPs that can assist include Community Engagement and Partnership Coordinators, Suicide Prevention Coordinators, Local Recovery Coordinators, and substance abuse counselors. In addition, VA patient services, patient safety, and public affairs office staff—as well as VA Homeless Programs—may be good resources. Every VA health care system has care coordinators focused on military sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ care. These care coordinators may be able to provide information on community resources that address social determinants of health (eg, discrimination, violence).

Reaching out to key community resources and asking for recommendations of other groups that provide assistance to veterans can also be productive. You can start by connecting with veterans service organizations (VSOs), Vet Centers, Veterans Experience Offices (VEO), and Community Veterans Engagement Boards (CVEBs). The VEO is an office designed around VA and community engagement efforts. This office utilizes the CVEBs to foster a 2-way communication feedback loop between veterans and local VA facilities regarding community engagement efforts and outreach.22 CVEBs are particularly valuable sources of information because veterans directly contribute to the conversation about community engagement by describing the difficulties and successes they’ve experienced. Veteran feedback about how a particular resource met their needs can inform which community services are prioritized for inclusion in the resource list. In addition, CVEBs may have a listing of local government, military, and/or community resources that provide services for veterans. Consider, too, organizations that are unrelated to an individual’s veteran status, but speak to their race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, spirituality, socioeconomic status, or disability.

Step 4: Continue to Build Inventory. Use online searches to identify additional resources in the community that are known to have local relationships. These include state suicide prevention coordinators, mental health organizations, and other resources that address social determinants of health (eg, public health and human service organizations, faith-based organizations, collegial organizations). A list of links and search tips are available in the Table.

Steps 5 and 6: Create Document; Organize and Disseminate Information. A spreadsheet can be used to document organization information (Appendix). It is critical to record: (1) the name of the organization or individual; (2) the local address and a point of contact with contact information; (3) services offered to veterans; (4) services specific to suicide prevention, or that address risk factors for suicide; and (5) whether the referral organization is partnered with the VA Community Care Network, which is comprised of contracted HCPs who contract with the VA to provide care to veterans.23

Once a document is created, it can be disseminated through VA offices and among community partners who work with veterans at risk for suicide. It should also be stored in a centralized location such as a shared folder so that it can be continuously updated.

Regularly updating the list is vital so the resource list can continue to be helpful in addressing veterans’ needs and reducing suicide risk factors. Continued collaboration with those in the community can help ensure the resource list is up to date with all available services and pertinent contact information. It can also go far in strengthening collaborative bonds.

IMPLEMENTATION

To illustrate the use of CAM for veteran suicide prevention, we offer a case example of CAM conducted by the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry — Suicide Prevention Collaborative (VA PSCI-SPC) team, consisting of 4 team members. A veteran was included as a team member and assisted with the CAM process.

The VA PSCI-SPC sought to identify community services for veterans in Colorado who were not enrolled in VA health care and had risk factors for suicide. Next, the team reached out to colleagues and asked about community organizations that work with individuals at risk for suicide. VA PSCI-SPC outreach resulted in a list of assets that included resources to address mental health, legal concerns, employment, homelessness/housing, finances, religion, peer support, food insecurity, exercise, intimate partner violence, sexual and gender identity needs, and peer support. VSOs and CVEBs were also added to the list.

Next, the team continued to build on the inventory and identified state suicide prevention coordinators; health care systems; regional suicide prevention commissions; Colorado Department of Health and Human Services; program coordinators for Governor’s and Mayor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families; veterans councils; universities (eg, counseling clinics, legal clinics); and foundations devoted to general and veteran-specific suicide prevention within the region.

All the identified resources were inventoried. Details were gathered about each of the organizations, including addresses, points of contact and phone numbers, descriptions of services offered for veterans, descriptions of suicide prevention services offered, whether or not organizations were not-for-profit, the mission of the organizations, and whether or not the organizations were under contract for VA Community Care. Finally, the resource spreadsheet was created and disseminated among stakeholders to be used to enhance veteran suicide care. Stakeholders included social workers, psychologists, and nurse practitioners working with veterans. The list was circulated to VA and community partners as needed.

The VA PSCI-SPC resource document was only 1 benefit of CAM. The asset mapping also resulted in the creation of a learning collaborative comprised of VA and community partners, designed to share knowledge of best practices in suicide prevention and create an established referral network for veterans at risk for suicide.24 Ultimately, the goal of the CAM and the creation of the learning collaborative was to better connect veterans to care in order to decrease suicide risk. A secondary benefit of this community connectedness is that the list of resources produced by CAM became a living document that was, and continues to be, updated as the network became aware of new resources and resources that were no longer available. The VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative met quarterly to discuss implementation of suicide prevention best practices within their organization.

Data from the VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative via CAM revealed that organizations felt more efficacious in implementing suicide prevention best practices, noticed increased connections and collaborations with community organizations with the goal of providing services to veterans, and resulted in staff training that improved services provided to veterans.24 This is supported by other findings of a literature review of suicide prevention interventions, which indicated that programs with an established community support network were more effective at reducing suicide rates.25 CAM therefore may be a process through which greater community connection and increased knowledge of resources may help prevent suicide among veterans.

It seems reasonable that the CAM processes used by the VA PSCI-SPC can be implemented within the regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks to identify assets in a specific geographical area to address challenges with social determinants of health and potentially decrease veteran suicide risk.

CONCLUSIONS

CAM can be used to identify and build relationships with community resources that address the stressors that place veterans at risk for suicide. Six proposed steps to CAM for veterans at risk for suicide include: defining community reach (the map); identifying community members and organizations with shared goals; identifying assets within the community; continuing to build inventory; creating a document; and organizing and disseminating the information (while continuing to update the resources).21

CAM can be used to connect veterans with resources to address needs related to adverse social determinants of health that may heighten their risk for suicide. For example, veterans facing legal challenges can connect with a legal clinic; those having difficulties paying bills can obtain financial assistance; those who need help completing their VA claims can connect with the Veterans Benefits Administration or VSOs to assist them with their claims; and those experiencing discrimination can connect with organizations where they may experience acceptance, safety, and support. Broad community support surrounding suicide risk factors can be critical for effective suicide prevention.25

CAM may also be helpful for HCPs and others involved in veteran health care. For example, community mapping can be utilized by newly hired community engagement and partnership coordinators as a tool for outlining resources available for veterans in their community and as a framework to continually update their resource network. CAM develops community awareness, integrates resources, and enhances service utilization, which may assist in veteran suicide prevention by increasing care coordination.17 Finally, mapping community resources can create awareness of the many resources available to help veterans, even before suicide becomes a consideration.

Suicide prevention is the leading clinical priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 An average of 18 veterans died by suicide each day in 2021.2 Numerous risk factors for veteran suicide have been identified, including mental health disorders, comorbidities, access to firearms, and potentially lethal medications.3-5 To better understand groups of patients at risk of suicide in medical settings, the authors have previously compared demographic and clinical risk factors between patients who died by suicide by using firearms or other means with matched patients who did not die by suicide (control group) to examine the impact of lack of social support, financial stress,6 legal problems,7 homelessness,8 and discrimination.9 The number of cooccurring risk factors a veteran experiences is associated with a greater likelihood of suicide attempts over time.10 In addition, some risk factors are social and environmental risk factors known as social determinants of health (SDoH), including financial stability and access to health care, food, housing, and education. 11 SDoH may influence health outcomes more broadly and are associated with greater risk of suicide.12,13

The VA offers programming to address suicide risk factors. However, not all veterans are eligible for VA care. Further, some veterans prefer to obtain non-VA services in their communities. Providing veterans with community resources that address risk factors, particularly SDoH, may be a worthwhile strategy for reducing suicide. Such resources have demonstrated success; for example, greater use of housing services was associated with a reduced risk for suicide-related mortality among unhoused veterans.12

The challenges that veterans experience can go beyond the scope of services the VA provides. For example, while the VA provides some services related to homelessness, justice involvement, and assistance with home loans, these services are often limited. Other services for veterans to address SDoH may require access to community resources, including food banks, employment assistance, respite and childcare services, and transportation assistance. Some veterans also may have experienced institutional betrayal, which could be a barrier to VA care and may motivate veterans to address their needs in the community.14 Veterans therefore may need a range of services beyond those within the VA. Leveraging community resources for veterans at risk for suicide is critical, as these resources may help to mitigate suicide risk.

An emerging emphasis of the VA is improving coordination with community partners to prevent veteran suicide. In 2019, the VA launched an improved Veterans Community Care Program, which implemented portions of the VA MISSION Act of 2018 to create additional connection to community care for VA-enrolled veterans. This includes assisting veterans in gaining access to specialty services not offered at a local VA medical center (VAMC), getting access to services sooner, and receiving care if they do not live near a VAMC.15 In addition, the COMPACT Act allows veterans in acute suicidal crisis to receive emergency health care through either VA or non-VA facilities at no cost.16 The VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028 is a 10-year plan to reduce veteran suicide rates that includes initiatives to increase connections between VA and community agencies.17 A suicide prevention community toolkit is available online for health care professionals (HCPs) (and others, including employers) outside of the VA who may be unfamiliar with best practices for working with veterans at risk for suicide.18

The challenge, however, is that there is often a lack of “connectedness” between VA suicide prevention coordinators and community resources to address suicide risk factors and related social determinants of health. These services include, but are not limited to suicide prevention, mental health counseling (particularly no/low-cost services), unemployment resources, financial assistance and counseling, housing assistance, and identity-related supportive spaces. A major stumbling block in connecting resources with veterans (regardless of discharge status) who need them is there is no single, national organization with a comprehensive, community-based network that can serve in this intermediary role.

Community asset mapping (CAM), also known as asset mapping or environmental scanning, is a way to bridge the gap.19 CAM provides a method for identifying and aligning community resources relative to a specific need.20 CAM may be used to build community relationships in service of veteran suicide prevention. This process can help individuals learn about and make use of organizations and services within their communities. CAM also helps connect HCPs so they can network, exchange ideas, and collaborate with an eye toward increasing the availability of services and enhancing care coordination. CAM also allows community members (eg, leaders, organizations, individuals) to identify possible gaps in services that address suicide risk factors and solve these problems.

This article details CAM for suicide prevention, which can be utilized by the VA and community organizations alike. Within the VA, CAM can be used by HCPs and administrators, such as VA community engagement and partnership coordinators, to identify potential partnering organizations. For those who serve veterans outside of the VA, CAM can be used to connect at-risk individuals to resources that can enhance their care. This process can help increase the overall knowledge of, and access to, community resources.

COMMUNITY ASSET MAPPING

The University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research provides 6 steps for the CAM process.21 These steps include: (1) defining the boundaries of people and places that comprise the community; (2) identifying people and organizations who share similar interests and goals; (3) determining the assets to include; (4) creating an inventory of all organizations’ assets; (5) creating an inventory of individuals’ assets; and (6) organizing the assets on a map. To address the needs of the veteran population, we’ve taken these 6 steps and adapted them to create a CAM for veterans at risk for suicide (Figure). The discussion that follows details how these steps can be implemented to identify community resources that address social determinants of health that may contribute to suicide risk. The goal is to prevent veteran suicide.

Step 1: Define Community Reach. The first step is to identify the geographical boundaries of the community. This may include all veterans within a catchment area (eg, veterans within 60 miles of a VAMC). Defining the geographical parameters of the community will provide structure to the effort so that the resource list is as comprehensive as possible.

Steps 2 and 3: Identify Community Members with Shared Goals; Identify Assets. It is important to identify community members who share similar interests and goals, including people with specific knowledge and skills, organizations with particular goals, and community partners with a broad reach. To begin building a list of referrals, reach out to colleagues within the VA system who are familiar with community resources for those with suicide risk factors. The local VA Transition and Care Management (TCM) office is a resource that connects those transitioning from military to civilian sectors with needed resources, and thus may be a helpful resource while building a CAM. Additionally, each office has a transition patient advocate, who is trained to resolve care-related concerns and may be familiar with community resources.

VA HCPs that can assist include Community Engagement and Partnership Coordinators, Suicide Prevention Coordinators, Local Recovery Coordinators, and substance abuse counselors. In addition, VA patient services, patient safety, and public affairs office staff—as well as VA Homeless Programs—may be good resources. Every VA health care system has care coordinators focused on military sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ care. These care coordinators may be able to provide information on community resources that address social determinants of health (eg, discrimination, violence).

Reaching out to key community resources and asking for recommendations of other groups that provide assistance to veterans can also be productive. You can start by connecting with veterans service organizations (VSOs), Vet Centers, Veterans Experience Offices (VEO), and Community Veterans Engagement Boards (CVEBs). The VEO is an office designed around VA and community engagement efforts. This office utilizes the CVEBs to foster a 2-way communication feedback loop between veterans and local VA facilities regarding community engagement efforts and outreach.22 CVEBs are particularly valuable sources of information because veterans directly contribute to the conversation about community engagement by describing the difficulties and successes they’ve experienced. Veteran feedback about how a particular resource met their needs can inform which community services are prioritized for inclusion in the resource list. In addition, CVEBs may have a listing of local government, military, and/or community resources that provide services for veterans. Consider, too, organizations that are unrelated to an individual’s veteran status, but speak to their race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, spirituality, socioeconomic status, or disability.

Step 4: Continue to Build Inventory. Use online searches to identify additional resources in the community that are known to have local relationships. These include state suicide prevention coordinators, mental health organizations, and other resources that address social determinants of health (eg, public health and human service organizations, faith-based organizations, collegial organizations). A list of links and search tips are available in the Table.

Steps 5 and 6: Create Document; Organize and Disseminate Information. A spreadsheet can be used to document organization information (Appendix). It is critical to record: (1) the name of the organization or individual; (2) the local address and a point of contact with contact information; (3) services offered to veterans; (4) services specific to suicide prevention, or that address risk factors for suicide; and (5) whether the referral organization is partnered with the VA Community Care Network, which is comprised of contracted HCPs who contract with the VA to provide care to veterans.23

Once a document is created, it can be disseminated through VA offices and among community partners who work with veterans at risk for suicide. It should also be stored in a centralized location such as a shared folder so that it can be continuously updated.

Regularly updating the list is vital so the resource list can continue to be helpful in addressing veterans’ needs and reducing suicide risk factors. Continued collaboration with those in the community can help ensure the resource list is up to date with all available services and pertinent contact information. It can also go far in strengthening collaborative bonds.

IMPLEMENTATION

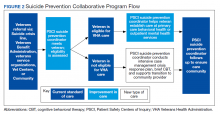

To illustrate the use of CAM for veteran suicide prevention, we offer a case example of CAM conducted by the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry — Suicide Prevention Collaborative (VA PSCI-SPC) team, consisting of 4 team members. A veteran was included as a team member and assisted with the CAM process.

The VA PSCI-SPC sought to identify community services for veterans in Colorado who were not enrolled in VA health care and had risk factors for suicide. Next, the team reached out to colleagues and asked about community organizations that work with individuals at risk for suicide. VA PSCI-SPC outreach resulted in a list of assets that included resources to address mental health, legal concerns, employment, homelessness/housing, finances, religion, peer support, food insecurity, exercise, intimate partner violence, sexual and gender identity needs, and peer support. VSOs and CVEBs were also added to the list.

Next, the team continued to build on the inventory and identified state suicide prevention coordinators; health care systems; regional suicide prevention commissions; Colorado Department of Health and Human Services; program coordinators for Governor’s and Mayor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families; veterans councils; universities (eg, counseling clinics, legal clinics); and foundations devoted to general and veteran-specific suicide prevention within the region.

All the identified resources were inventoried. Details were gathered about each of the organizations, including addresses, points of contact and phone numbers, descriptions of services offered for veterans, descriptions of suicide prevention services offered, whether or not organizations were not-for-profit, the mission of the organizations, and whether or not the organizations were under contract for VA Community Care. Finally, the resource spreadsheet was created and disseminated among stakeholders to be used to enhance veteran suicide care. Stakeholders included social workers, psychologists, and nurse practitioners working with veterans. The list was circulated to VA and community partners as needed.

The VA PSCI-SPC resource document was only 1 benefit of CAM. The asset mapping also resulted in the creation of a learning collaborative comprised of VA and community partners, designed to share knowledge of best practices in suicide prevention and create an established referral network for veterans at risk for suicide.24 Ultimately, the goal of the CAM and the creation of the learning collaborative was to better connect veterans to care in order to decrease suicide risk. A secondary benefit of this community connectedness is that the list of resources produced by CAM became a living document that was, and continues to be, updated as the network became aware of new resources and resources that were no longer available. The VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative met quarterly to discuss implementation of suicide prevention best practices within their organization.

Data from the VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative via CAM revealed that organizations felt more efficacious in implementing suicide prevention best practices, noticed increased connections and collaborations with community organizations with the goal of providing services to veterans, and resulted in staff training that improved services provided to veterans.24 This is supported by other findings of a literature review of suicide prevention interventions, which indicated that programs with an established community support network were more effective at reducing suicide rates.25 CAM therefore may be a process through which greater community connection and increased knowledge of resources may help prevent suicide among veterans.

It seems reasonable that the CAM processes used by the VA PSCI-SPC can be implemented within the regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks to identify assets in a specific geographical area to address challenges with social determinants of health and potentially decrease veteran suicide risk.

CONCLUSIONS

CAM can be used to identify and build relationships with community resources that address the stressors that place veterans at risk for suicide. Six proposed steps to CAM for veterans at risk for suicide include: defining community reach (the map); identifying community members and organizations with shared goals; identifying assets within the community; continuing to build inventory; creating a document; and organizing and disseminating the information (while continuing to update the resources).21

CAM can be used to connect veterans with resources to address needs related to adverse social determinants of health that may heighten their risk for suicide. For example, veterans facing legal challenges can connect with a legal clinic; those having difficulties paying bills can obtain financial assistance; those who need help completing their VA claims can connect with the Veterans Benefits Administration or VSOs to assist them with their claims; and those experiencing discrimination can connect with organizations where they may experience acceptance, safety, and support. Broad community support surrounding suicide risk factors can be critical for effective suicide prevention.25

CAM may also be helpful for HCPs and others involved in veteran health care. For example, community mapping can be utilized by newly hired community engagement and partnership coordinators as a tool for outlining resources available for veterans in their community and as a framework to continually update their resource network. CAM develops community awareness, integrates resources, and enhances service utilization, which may assist in veteran suicide prevention by increasing care coordination.17 Finally, mapping community resources can create awareness of the many resources available to help veterans, even before suicide becomes a consideration.

- Rice L. VA Secretary Robert Wilkie says suicide prevention is his agency’s top ‘clinical’ priority. June 17, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.kut.org/post/va-secretary-robert-wilkie-says-suicide-prevention-his-agencys-top-clinical-priority

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2023 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. November 2023. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Kittel JA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. Psychological inflexibility predicts of suicidal ideation over time in veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(6):627–641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12388

- Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB, Ignacio RV, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129

- Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. A 12-month prospective study of the effects of PTSD-depression comorbidity on suicidal behavior in Iraq/ Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:97–99. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011

- Hoffmire CA, Borowski S, Vogt D. Contribution of veterans’ initial post-separation vocational, financial, and social experiences to their suicidal ideation trajectories following military service. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(3):443- 456. doi:10.1111/sltb.12955

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs suicide prevention among veterans experiencing homelessness workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 2):S103- S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399

- Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social supsupport and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

- Lee DJ, Kearns JC, Wisco BE, et al. A longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7): 609-618. doi:10.1002/da.22736

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH). Accessed January 30, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Montgomery AE, Dichter M, Byrne T, Blosnich J. Intervention to address homelessness and all-cause and suicide mortality among unstably housed US veterans, 2012- 2016. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:380-386. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214664

- Llamocca EN, Yeh HH, Miller-Matero LR, et al. Association between adverse social determinants of health and suicide death. Med Care. 2023;61(11):744-749. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001918

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Schneider AL, et al. Institutional betrayal and help-seeking among women survivors of military sexual trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):814-823. doi:10.1037/tra0001027

- VA launches new health care options under MISSION Act. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. June 6, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5264

- COMPACT Act expands free emergency suicide care for veterans. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 1, 2023. Accessed January 31,2025. https://www.va.gov/poplar-bluff-health-care/news-releases/compact-act-expands-free-emergency-suicide-care-for-veterans/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing Veteran suicide 2018-2028. 2018. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran outreach toolkit: preventing veteran suicide is everyone’s business. A community call to action. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://floridavets.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/VA-Suicide-Prevention-Community-Outreach-Toolkit.pdf

- Crane K, Mooney M. Essential tools: community resource mapping. 2005. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/172995/NCSET_EssentialTools_ResourceMapping.pdf

- Community Tool Box. 2. Assessing Community Needs and Resources. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/assessing-community-needs-and-resources

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Section 1: asset mapping. 2012. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/programs/healthdata/trainings/documents/tw_cba20.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Experience Office. 4th quarter 2018 community engagement news. October 2, 2018. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USVAVEO/bulletins/211836e

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. About our VA community care network and covered services. Accessed February 6, 2025. https://www.va.gov/resources/aboutour-va-community-care-network-and-covered-services/

- DeBeer B, Mignogna J, Borah E, et al. A pilot of a veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative among community organizations: Initial results and outcomes. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(4):628-641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12969

- Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Rihmer Z. Suicide prevention programs through community intervention. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):10–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.009

- Rice L. VA Secretary Robert Wilkie says suicide prevention is his agency’s top ‘clinical’ priority. June 17, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.kut.org/post/va-secretary-robert-wilkie-says-suicide-prevention-his-agencys-top-clinical-priority

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2023 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. November 2023. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Kittel JA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. Psychological inflexibility predicts of suicidal ideation over time in veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(6):627–641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12388

- Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB, Ignacio RV, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129

- Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. A 12-month prospective study of the effects of PTSD-depression comorbidity on suicidal behavior in Iraq/ Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:97–99. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011

- Hoffmire CA, Borowski S, Vogt D. Contribution of veterans’ initial post-separation vocational, financial, and social experiences to their suicidal ideation trajectories following military service. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(3):443- 456. doi:10.1111/sltb.12955

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs suicide prevention among veterans experiencing homelessness workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 2):S103- S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399

- Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social supsupport and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

- Lee DJ, Kearns JC, Wisco BE, et al. A longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7): 609-618. doi:10.1002/da.22736

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH). Accessed January 30, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Montgomery AE, Dichter M, Byrne T, Blosnich J. Intervention to address homelessness and all-cause and suicide mortality among unstably housed US veterans, 2012- 2016. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:380-386. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214664

- Llamocca EN, Yeh HH, Miller-Matero LR, et al. Association between adverse social determinants of health and suicide death. Med Care. 2023;61(11):744-749. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001918

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Schneider AL, et al. Institutional betrayal and help-seeking among women survivors of military sexual trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):814-823. doi:10.1037/tra0001027

- VA launches new health care options under MISSION Act. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. June 6, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5264

- COMPACT Act expands free emergency suicide care for veterans. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 1, 2023. Accessed January 31,2025. https://www.va.gov/poplar-bluff-health-care/news-releases/compact-act-expands-free-emergency-suicide-care-for-veterans/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing Veteran suicide 2018-2028. 2018. Accessed January 31, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran outreach toolkit: preventing veteran suicide is everyone’s business. A community call to action. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://floridavets.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/VA-Suicide-Prevention-Community-Outreach-Toolkit.pdf

- Crane K, Mooney M. Essential tools: community resource mapping. 2005. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/172995/NCSET_EssentialTools_ResourceMapping.pdf

- Community Tool Box. 2. Assessing Community Needs and Resources. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/assessing-community-needs-and-resources

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Section 1: asset mapping. 2012. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/programs/healthdata/trainings/documents/tw_cba20.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Experience Office. 4th quarter 2018 community engagement news. October 2, 2018. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USVAVEO/bulletins/211836e

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. About our VA community care network and covered services. Accessed February 6, 2025. https://www.va.gov/resources/aboutour-va-community-care-network-and-covered-services/

- DeBeer B, Mignogna J, Borah E, et al. A pilot of a veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative among community organizations: Initial results and outcomes. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(4):628-641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12969

- Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Rihmer Z. Suicide prevention programs through community intervention. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):10–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.009

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

The Veterans Affairs Patient Safety Center of Inquiry—Suicide Prevention Collaborative: Creating Novel Approaches to Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Receiving Community Services

Since 2008, suicide has ranked as the tenth leading cause of death for all ages in the US, with rates of suicide continuing to rise.1-3 Suicide is even more urgent to address in veteran populations. The age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate in 2017 was more than 1.5 times greater for veterans than it was for nonveteran adults.2 Of importance, rates of suicide are increasing at a faster rate in veterans who are not connected to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) care.4,5 These at-risk veterans include individuals who are eligible for VHA care yet have not had a VHA appointment within the year before death; veterans who may be ineligible to receive VHA care due to complex rules set by legislation; and veterans who are eligible but not enrolled in VHA care. Notably, between 2005 and 2016, the number of veterans not enrolled in VHA care rose more quickly than did the number of veterans enrolled in VHA care.5,6 Thus, to impact the high veteran suicide rates, an emergent challenge for VHA is to prevent suicide among unenrolled veterans and veterans receiving community care, while continuing to increase access to mental health services for veterans enrolled in VHA health care.

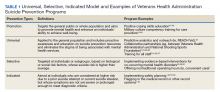

In response to the high rates of veteran suicide deaths, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has developed a broad, multicomponent suicide prevention program that is unparalleled in private US health care systems.4,7 Suicide prevention efforts are led and implemented by both the VHA National Center for Patient Safety and the VHA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Program components are numerous and multifaceted, falling within the broad promotion and prevention strategies outlined by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM).1,8-11 The NAM continuum of prevention model encompassing multiple strategies is also referred to as the Universal, Selective, Indicated (USI) Model.7,8,10 The VHA suicide prevention program contains a wide spread of program components, making it both comprehensive and innovative (Table 1).

Although significant momentum and progress has been made within the VHA, policy set by legislation has historically limited access to VHA health care services to VHA-eligible veterans. This is particularly concerning given the rising suicide rates among veterans not engaged in VHA care.2 Adding to this complexity, recent legislation has increased veterans’ access to non-VHA health care, in addition to their existing access through Medicare, Medicaid, and other health care programs.12-14 Best practices for suicide prevention are not often implemented in the private sector; thus, these systems are ill prepared to adequately meet the suicide prevention care needs of veterans.4,15-18 Furthermore, VHA and non-VHA services generally are not well coordinated, and private sector health care providers (HCPs) are not required to complete a commensurate level of suicide prevention training as are VHA HCPs.16-18 Most non-VHA HCPs do not receive military cultural competence training.19 These issues create a significant gap in suicide prevention services and may contribute to the increases in suicide rates in veterans who do not receive VHA care. Thus, changes in policy to increase access through private sector care may have paradoxical effects on veteran suicide deaths. To impact the veteran suicide rate, VHA must develop and disseminate best practices for veterans who use non-VHA services.

A Roadmap to Suicide Prevention

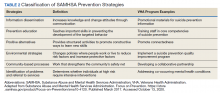

There is significant momentum at the federal level regarding this issue. The President’s Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End the National Tragedy of Suicide (Executive Order 13,861) directs the VHA to work closely with community organizations to improve veteran suicide prevention.20 The VHA and partners, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), are bridging this gap with collaborative efforts that increase suicide prevention resources for veterans living in the community through programs such as the Governor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families. These programs intend to empower communities to develop statewide, strategic action plans to prevent veteran suicide.7,21-24

In addition to partnerships, VHA has built other aspects of outreach and intervention into its programming. A key VHA initiative is to “know all veterans” by committing to identifying and reaching out to all veterans who may be at risk for suicide.22 The VHA has committed to offering “emergency stabilization care for former service members who present at the facility with an emergent mental health need” regardless of eligibility.25 The intent is to provide temporary emergent mental health care to veterans who are otherwise ineligible for care, such as those who were discharged under other-than-honorable conditions while the VHA determines eligibility status.26 However, veterans must meet certain criteria, and there is a limit on services.

Although services are being expanded to reach veterans who do not access VHA health care, how to best implement these new directives with regard to suicide prevention is unclear. Strategic development and innovations to expand suicide prevention care to veterans outside the current reach of VHA are desperately needed.

Program Overview

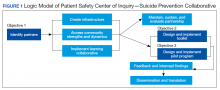

VHA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry-Suicide Prevention Collaborative (PSCI-SPC), funded by the VHA National Center for Patient Safety, aims to help fill the gap in community-based suicide prevention for veterans. PSCI-SPC is located within the VHA Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center in Aurora, Colorado. The overarching mission of PSCI-SPC is to develop, implement, and evaluate practical solutions to reduce suicide among veterans not receiving VHA care. PSCI-SPC serves as a national clinical innovation and dissemination center for best practices in suicide prevention for organizations that serve veterans who receive care in the community. PSCI-SPC creates products to support dissemination of these practices to other VAMCs and works to ensure these programs are sustainable. PSCI-SPC focuses on 3 primary objectives. All PSCI-SPC projects are currently underway.

Objective 1: Growing a Community Learning Collaborative

Acknowledging that nearly two-thirds of veterans who die by suicide do not use VHA services, PSCI-SPC aims to reduce suicide among all veterans by expanding the reach of best practices for suicide prevention to veterans who receive myriad services in the community.27 Community organizations are defined here as organizations that may in some way serve, interact with, or work with veterans, and/or employ veterans. Examples include non-VHA health care systems, public services such as police and fire departments, nonprofit organizations, mental health clinics, and veterans’ courts. As veterans increasingly seek health care and other services within their communities, the success of suicide prevention will be influenced by the capability of non-VHA public and private organizations. Objective 1, therefore, seeks to develop a VHA-community collaborative that can be leveraged to improve systems of suicide prevention.

Current programs in the VHA have focused on implementation of suicide prevention awareness and prevention education campaigns instead of grassroots partnerships that are intended to be sustainable. Additionally, these programs typically lack the capacity and systems to sustain numerous meaningful community partnerships. Traditionally, community organizations have been hesitant to partner with government agencies, such as the VHA, due to histories of institutional mistrust and bureaucracy.28

The PSCI-SPC model for developing a VHA-community collaborative partnership draws from the tradition of community-based participatory research. The best community-based participatory research practices are to build on strengths and resources within the local community; develop collaborative, equitable partnerships that involve an empowering and power-sharing process; foster colearning, heuristics, and capacity building among partners; and focus on systems development using an iterative process. These practices also are consistent with the literature on learning collaboratives.29-31

The premise for a learning collaborative is to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice in health care.31 Figure 1 depicts how this collaborative was developed, and how it supports Objectives 2 and 3. To achieve Objective 1, we developed a VHA-learning collaborative of 13 influential community partners in the Denver and Colorado Springs region of Colorado. The VHA team consists of a learning collaborative leader, a program manager, and a program support assistant. The principal investigator attends and contributes to all meetings. Learning collaborative partners include a university psychology clinic that focuses on veterans’ care, 3 veterans service organizations, a mental health private practice, a university school of nursing, a community mental health center, veterans’ courts, and 5 city departments.

These partners participated in qualitative interviews to identify where gaps and breakdowns were occurring. With this information, the PSCI-SPC team and VHA-learning collaborative held a kickoff event. At this meeting the team discussed the qualitative findings, provided veteran suicide prevention information, and basic information regarding suicide prevention program building and implementation science.