User login

AGA helps break down barriers to CRC screening

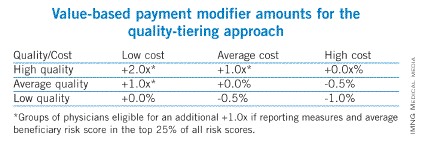

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

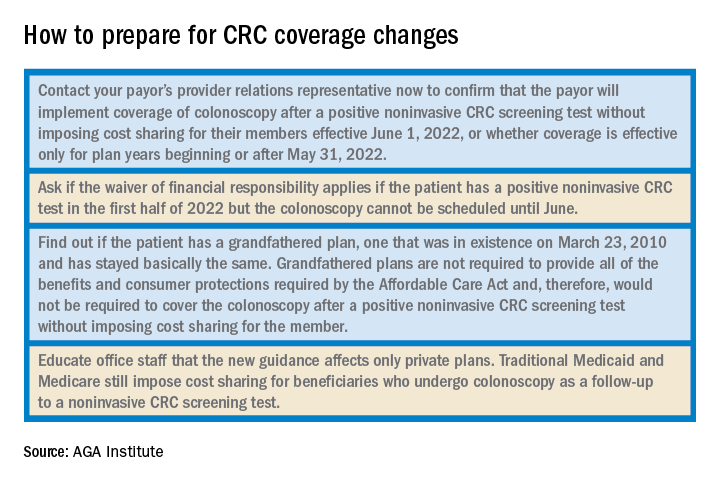

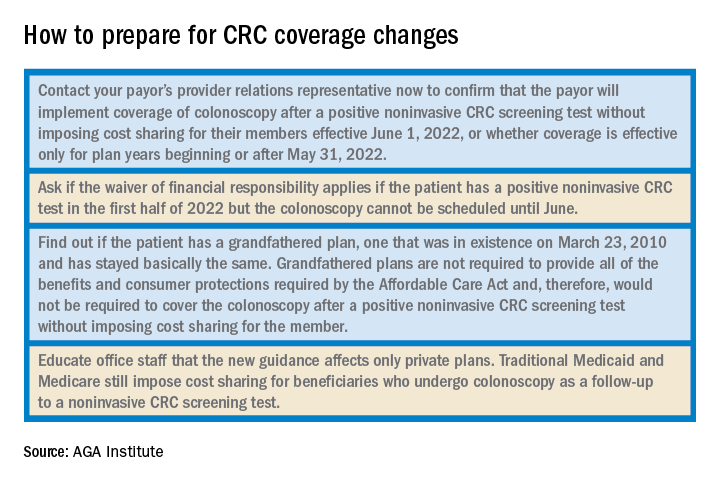

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

Colorectal cancer screening quality measures – beyond colonoscopy

Medicine in the United States is undergoing fundamental changes that will continue despite 2016 presidential election results. Changes include consolidation of provider networks, movement from volume- to value-based reimbursement, demands for price and quality transparency, and a shift from focusing solely on individual physician-patient interactions to a broader triple aim focus that incorporates individual patients, population, health, and cost. In this month’s column, Sameer Saini and colleagues suggest that we broaden our view of colorectal cancer screening quality metrics from a colonoscopy-centric focus to a focus on the bottom line: Do we reduce cancer in the population of patients that we serve? When we extend our view to a population level, we use current colonoscopy registries only as internal process controls. A successful health system will develop a mechanism to assess and demonstrate how well the collective team of providers accomplishes the only outcome that matters to patients: preventing colon cancer.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is one of the most valuable services provided by gastroenterologists. The evidence that screening “works” on a population level is undeniable. But not every screening program is equally effective. Data indicate ongoing underuse of screening, particularly in high-risk, vulnerable, and minority communities.1,2 Other data indicate that screening is overused, particularly in low-risk patients and in those with limited life expectancy.3-5 It is also known that endoscopist skill plays an important role in the effectiveness of screening. In short, there is ample room for improvement in the quality of CRC screening, and payers and the public have taken notice. Unsurprisingly, gastroenterologists are often focused on procedural quality indicators, such as adenoma detection and cecal intubation rates.6 These endoscopic quality measures are important indicators of high-quality colonoscopy, but colonoscopy is the common touch point of a much broader system of care that includes other screening tests and other providers (e.g., primary care providers [PCPs], pathologists, and anesthesiologists). Coordinating care across this system is essential for improving the health of patients. As the stewards of digestive health, we owe it to our patients to take a more comprehensive view of CRC screening quality and move beyond colonoscopy alone.

The complex web of care that comprises CRC screening is shown schematically in Figure 1. Appropriate screening begins with selection of suitable screening candidates. In the United States, where most screening is initiated during a clinician encounter, this important task falls primarily on the shoulders of PCPs. It is typically the role of the PCP to assess the two key patient factors that determine screening benefit: CRC risk (using personal and family history) and life expectancy (using age and overall health status). Once a patient has been deemed an appropriate candidate for screening, an acceptable screening test must be selected. Here, patient and practitioner are faced with a menu of options, including fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), colonoscopy, multitarget stool DNA, and computed tomography colonography. For average-risk screening, the ideal test depends primarily on patient preference and local availability.

If a screening test other than colonoscopy is selected, it becomes critical that a positive test is followed by timely and high-quality colonoscopy. High-quality colonoscopy begins with evidence-based preprocedure education and preparation, including appropriate selection of anesthesia services. Once a patient has been well prepared and adequately sedated, an endoscopist must carefully examine the colonic mucosa and completely resect any suspicious polyps. Unless discarded, resected polyps must be reviewed and categorized by a pathologist, including appropriate identification of serrated polyps. Finally, pathology results must be correctly interpreted by the clinician, with evidence-based follow-up recommendations made and effectively communicated to the patient and the referring provider. Additionally, in the short term, delayed gastrointestinal (GI) and non-GI complications of colonoscopy must be recognized and appropriately addressed. In the long term, the rate of interval cancers must be monitored.

Recognizing the importance of CRC screening, GI specialty societies have proposed a variety of quality measures to ensure that patients receive high-quality and high-value colonoscopy. Several of these measures have been adopted by CMS as part of the Physician Quality Reporting System. Non-GI groups, such as the National Center for Quality Assurance and the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, have also proposed their own CRC screening–related measures.

Despite the proliferation of measures in the domain of CRC screening, current measures fall short in several ways. First, they are largely focused on colonoscopy technical performance, with less attention paid to the important steps that occur before and after colonoscopy. For example, the existing Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure for underuse of CRC screening assesses the proportion of patients in a health plan between the ages 50 and 75 who are up to date for CRC screening. This measure is satisfied if a patient completes FOBT, regardless of the result. But FOBT alone is not sufficient to reduce mortality from CRC. Rather, it is imperative that a positive FOBT test be followed by colonoscopy. Numerous studies suggest a quality gap in this critical referral step.7

Yet, outside of selected clinical settings (e.g., the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System), no existing quality measure focuses on colonoscopy completion after positive FOBT. Other examples of important performance gaps beyond colonoscopy technical performance include appropriate use of monitored anesthesia care (data suggest overuse) and appropriate pathology interpretation (data suggest variation in the interpretation of serrated lesions, some of which are associated with increased risk of CRC).

Second, existing measures fail to consider individual patient factors that are known to be predictive of screening benefit, such as life expectancy and personal or familial cancer risk.8

Returning to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure as an example, this measure relies on age alone to identify patients who are candidates for screening. Yet, it is widely recognized that life expectancy is a critically important factor when considering screening, particularly in older patients. However, existing measures fail to incorporate estimates of life expectancy. As a result, clinicians are encouraged to screen based on age alone. Data suggest that this leads to overuse in older, sicker patients younger than age 75 (the age cutoff suggested by guidelines and incorporated into the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure) and underuse in healthy and unscreened patients older than age 75.9

Furthermore, existing measures fail to systematically consider patient preferences and undervalue shared decision making. Data suggest, for instance, that patients who are offered a “menu” of options for screening rather than a single screening test are more likely to complete a screening test.10

But existing measures do not consider whether a physician assessed a patient’s preferences, or offered more than one screening option. Of course, measuring the quality of decision making is an evolving science that presents challenges and requires creative solutions.11

Finally, existing measures do not capture the collaborative nature of modern health care. For example, most existing measures focus on the performance of gastroenterologists and GI practices. Although such a focus is appropriate for specialty-specific quality improvement efforts, it neglects to capture the important interactions and hand-offs between providers needed for successful completion of screening (and downstream reduction in cancer mortality). As a result, this specialty-focused approach fails to meet the needs of patients, who are increasingly interested in whether the care they receive is improving their health regardless of who provides it. It also fails to meet the needs of payers, who are interested in whether a network of providers is delivering high-value care for its members. Developing measures that capture the collaborative nature of modern health care becomes increasingly important as payers embrace alternative payment models and other value-based reimbursement systems.

Given these challenges with existing measures, we propose the following concepts for consideration as noncolonoscopy quality measures of CRC screening:

1. Appropriateness of referral for CRC screening (PCP): Measures in this domain should incorporate assessment of family history, prior screening history, and/or life expectancy, all of which are predictive of screening benefit and can be extracted from structured electronic health record data.

2. Shared decision making in choosing a CRC screening test (PCP): Currently, measures in this domain are (by necessity) relatively simple, such as assessment of documentation of whether stool testing was offered alongside colonoscopy during a clinic visit.

3. Percentage of individuals with a positive noncolonoscopy CRC screening test who complete a colonoscopy within 6 months (PCP and GI): A measure in this domain can be developed and implemented using existing infrastructure. The Veterans Affairs Healthcare System currently uses such a measure to monitor appropriate follow-up of positive fecal immunochemical tests.

4. Predicted reduction in CRC mortality: This measure, which provides an estimate of the effectiveness and value of a screening program, represents the “bottom line” that is ultimately of interest to both patients and payers. However, composite measures that use projected results require sophisticated statistical approaches and case-mix adjustment. They must also contend with “churn” in the covered population.

Although a more comprehensive view of screening is desirable, operationalizing measure concepts, such as those proposed previously, is challenging for several reasons. First, as we have outlined, CRC screening is truly a “team sport.” The stakeholders in CRC screening include public health, primary care, gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, oncology, anesthesiology, and pathology practitioners. As a result, screening has no natural and obvious steward. Rather, various components of care are adopted by different specialty groups, and this approach leads to unmonitored gaps in care. We believe that gastroenterologists can and should take the lead in developing comprehensive quality measures for CRC screening. Such comprehensive measures will be of value to patients and to payers. Second, assessing quality of care more comprehensively has traditionally been infeasible. For example, incorporating life expectancy into quality measures requires electronic assessment of health status.

Traditionally, such efforts have been hampered by the lack of systematic clinical data collection. However, as meaningful use of electronic health records increases, measures that incorporate such information are likely to become increasingly feasible. Finally, we also need to consider how to make these improvements while avoiding measure proliferation. Proliferation leads to provider fatigue and discourages thoughtful clinical decision making, potentially worsening quality of care. Creative approaches, such as rotating measure sets over time, use of clinical decision support tools, and balancing underuse measures with overuse measures, may be warranted. Additionally, composite measures may prove to be more meaningful and more practical for patients, providers, and payers. Ultimately, a distinction must be made between quality assurance and quality improvement; both are important, but the types of measures and the level of measure sophistication used in each program undoubtedly vary.

In summary, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for high-quality CRC screening that extends beyond simply providing a high-quality colonoscopy. This broader view of quality benefits patients by ensuring that our expertise informs the metrics by which delivery of CRC screening is measured. It also ensures that we hold ourselves and our colleagues to the highest standards across the continuum of care. Additionally, as alternative payment models and value-based contracting are implemented, nonendoscopic screening methods will likely become more commonplace. Advocating for high-quality nonendoscopic screening will help maintain gastroenterologists’ role as the stewards of CRC screening and digestive health. Although operationalizing measure concepts such as those proposed here may be difficult, it is critical if we are to provide the best possible care for our patients.

References

1. Sabatino, S.A., White, M.C., Thompson, T.D., et al. Cancer screening test use – United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:464-8.

2. Anderson, A.E., Henry, K.A., Samadder, N.J., et al. Rural vs urban residence affects risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:526-33.

3. Walter, L.C., Lindquist, K., Nugent, S., et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:465-73.

4. Murphy, C.C., Sandler, R.S., Grubber, J.M., et al. Underuse and overuse of colonoscopy for repeat screening and surveillance in the Veterans Health Administration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:436-44.

5. Mittal, S., Lin, Y.-L., Tan, A., et al. Limited life expectancy among a subgroup of Medicare beneficiaries receiving screening colonoscopies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:443-50.e1

6. Allen, J.I. Quality measures for colonoscopy: where should we be in 2015?. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:10.

7. Fisher, D.A., Jeffreys, A., Coffman, C.J., et al. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:1232-5.

8. Saini, S.D., van Hees, F., Vijan, S. Smarter screening for cancer: possibilities and challenges of personalization. JAMA. 2014;312:2211-2.

9. Saini, S.D., Vijan, S., Schoenfeld, P., et al. Role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1247.

10. Inadomi, J.M., Vijan, S., Janz, N.K., et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:575-82.

11. Writing Committee Members, Drozda, J.P., Ferguson, T.B., et al. 2015 ACC/AHA focused update of secondary prevention lipid performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:558-87.

Dr. Saini is a research scientist at the VA Center for Clinical Management Research and an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Adams is a clinical lecturer in the division of gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, and a research investigator, VA Center for Clinical Management Research; Dr. Brill is the chief medical officer of Predictive Health, Paradise Valley, Ariz., and a clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix; Dr. Gupta is codirector of Digestive Health Center, director of interventional endoscopy, and associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola University Medical Center; Dr. Naveed is a clinical assistant professor in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; Dr. Rosenberg is at Illinois Gastroenterology Group; and Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C. Dr. Saini’s and Dr. Gellad’s research is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Awards (CDA 09-213-2 and CDA 14-158). Dr. Gupta has received research support from Cook Medical, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, and CDx Diagnostics.

Medicine in the United States is undergoing fundamental changes that will continue despite 2016 presidential election results. Changes include consolidation of provider networks, movement from volume- to value-based reimbursement, demands for price and quality transparency, and a shift from focusing solely on individual physician-patient interactions to a broader triple aim focus that incorporates individual patients, population, health, and cost. In this month’s column, Sameer Saini and colleagues suggest that we broaden our view of colorectal cancer screening quality metrics from a colonoscopy-centric focus to a focus on the bottom line: Do we reduce cancer in the population of patients that we serve? When we extend our view to a population level, we use current colonoscopy registries only as internal process controls. A successful health system will develop a mechanism to assess and demonstrate how well the collective team of providers accomplishes the only outcome that matters to patients: preventing colon cancer.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is one of the most valuable services provided by gastroenterologists. The evidence that screening “works” on a population level is undeniable. But not every screening program is equally effective. Data indicate ongoing underuse of screening, particularly in high-risk, vulnerable, and minority communities.1,2 Other data indicate that screening is overused, particularly in low-risk patients and in those with limited life expectancy.3-5 It is also known that endoscopist skill plays an important role in the effectiveness of screening. In short, there is ample room for improvement in the quality of CRC screening, and payers and the public have taken notice. Unsurprisingly, gastroenterologists are often focused on procedural quality indicators, such as adenoma detection and cecal intubation rates.6 These endoscopic quality measures are important indicators of high-quality colonoscopy, but colonoscopy is the common touch point of a much broader system of care that includes other screening tests and other providers (e.g., primary care providers [PCPs], pathologists, and anesthesiologists). Coordinating care across this system is essential for improving the health of patients. As the stewards of digestive health, we owe it to our patients to take a more comprehensive view of CRC screening quality and move beyond colonoscopy alone.

The complex web of care that comprises CRC screening is shown schematically in Figure 1. Appropriate screening begins with selection of suitable screening candidates. In the United States, where most screening is initiated during a clinician encounter, this important task falls primarily on the shoulders of PCPs. It is typically the role of the PCP to assess the two key patient factors that determine screening benefit: CRC risk (using personal and family history) and life expectancy (using age and overall health status). Once a patient has been deemed an appropriate candidate for screening, an acceptable screening test must be selected. Here, patient and practitioner are faced with a menu of options, including fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), colonoscopy, multitarget stool DNA, and computed tomography colonography. For average-risk screening, the ideal test depends primarily on patient preference and local availability.

If a screening test other than colonoscopy is selected, it becomes critical that a positive test is followed by timely and high-quality colonoscopy. High-quality colonoscopy begins with evidence-based preprocedure education and preparation, including appropriate selection of anesthesia services. Once a patient has been well prepared and adequately sedated, an endoscopist must carefully examine the colonic mucosa and completely resect any suspicious polyps. Unless discarded, resected polyps must be reviewed and categorized by a pathologist, including appropriate identification of serrated polyps. Finally, pathology results must be correctly interpreted by the clinician, with evidence-based follow-up recommendations made and effectively communicated to the patient and the referring provider. Additionally, in the short term, delayed gastrointestinal (GI) and non-GI complications of colonoscopy must be recognized and appropriately addressed. In the long term, the rate of interval cancers must be monitored.

Recognizing the importance of CRC screening, GI specialty societies have proposed a variety of quality measures to ensure that patients receive high-quality and high-value colonoscopy. Several of these measures have been adopted by CMS as part of the Physician Quality Reporting System. Non-GI groups, such as the National Center for Quality Assurance and the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, have also proposed their own CRC screening–related measures.

Despite the proliferation of measures in the domain of CRC screening, current measures fall short in several ways. First, they are largely focused on colonoscopy technical performance, with less attention paid to the important steps that occur before and after colonoscopy. For example, the existing Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure for underuse of CRC screening assesses the proportion of patients in a health plan between the ages 50 and 75 who are up to date for CRC screening. This measure is satisfied if a patient completes FOBT, regardless of the result. But FOBT alone is not sufficient to reduce mortality from CRC. Rather, it is imperative that a positive FOBT test be followed by colonoscopy. Numerous studies suggest a quality gap in this critical referral step.7

Yet, outside of selected clinical settings (e.g., the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System), no existing quality measure focuses on colonoscopy completion after positive FOBT. Other examples of important performance gaps beyond colonoscopy technical performance include appropriate use of monitored anesthesia care (data suggest overuse) and appropriate pathology interpretation (data suggest variation in the interpretation of serrated lesions, some of which are associated with increased risk of CRC).

Second, existing measures fail to consider individual patient factors that are known to be predictive of screening benefit, such as life expectancy and personal or familial cancer risk.8

Returning to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure as an example, this measure relies on age alone to identify patients who are candidates for screening. Yet, it is widely recognized that life expectancy is a critically important factor when considering screening, particularly in older patients. However, existing measures fail to incorporate estimates of life expectancy. As a result, clinicians are encouraged to screen based on age alone. Data suggest that this leads to overuse in older, sicker patients younger than age 75 (the age cutoff suggested by guidelines and incorporated into the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure) and underuse in healthy and unscreened patients older than age 75.9

Furthermore, existing measures fail to systematically consider patient preferences and undervalue shared decision making. Data suggest, for instance, that patients who are offered a “menu” of options for screening rather than a single screening test are more likely to complete a screening test.10

But existing measures do not consider whether a physician assessed a patient’s preferences, or offered more than one screening option. Of course, measuring the quality of decision making is an evolving science that presents challenges and requires creative solutions.11

Finally, existing measures do not capture the collaborative nature of modern health care. For example, most existing measures focus on the performance of gastroenterologists and GI practices. Although such a focus is appropriate for specialty-specific quality improvement efforts, it neglects to capture the important interactions and hand-offs between providers needed for successful completion of screening (and downstream reduction in cancer mortality). As a result, this specialty-focused approach fails to meet the needs of patients, who are increasingly interested in whether the care they receive is improving their health regardless of who provides it. It also fails to meet the needs of payers, who are interested in whether a network of providers is delivering high-value care for its members. Developing measures that capture the collaborative nature of modern health care becomes increasingly important as payers embrace alternative payment models and other value-based reimbursement systems.

Given these challenges with existing measures, we propose the following concepts for consideration as noncolonoscopy quality measures of CRC screening:

1. Appropriateness of referral for CRC screening (PCP): Measures in this domain should incorporate assessment of family history, prior screening history, and/or life expectancy, all of which are predictive of screening benefit and can be extracted from structured electronic health record data.

2. Shared decision making in choosing a CRC screening test (PCP): Currently, measures in this domain are (by necessity) relatively simple, such as assessment of documentation of whether stool testing was offered alongside colonoscopy during a clinic visit.

3. Percentage of individuals with a positive noncolonoscopy CRC screening test who complete a colonoscopy within 6 months (PCP and GI): A measure in this domain can be developed and implemented using existing infrastructure. The Veterans Affairs Healthcare System currently uses such a measure to monitor appropriate follow-up of positive fecal immunochemical tests.

4. Predicted reduction in CRC mortality: This measure, which provides an estimate of the effectiveness and value of a screening program, represents the “bottom line” that is ultimately of interest to both patients and payers. However, composite measures that use projected results require sophisticated statistical approaches and case-mix adjustment. They must also contend with “churn” in the covered population.

Although a more comprehensive view of screening is desirable, operationalizing measure concepts, such as those proposed previously, is challenging for several reasons. First, as we have outlined, CRC screening is truly a “team sport.” The stakeholders in CRC screening include public health, primary care, gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, oncology, anesthesiology, and pathology practitioners. As a result, screening has no natural and obvious steward. Rather, various components of care are adopted by different specialty groups, and this approach leads to unmonitored gaps in care. We believe that gastroenterologists can and should take the lead in developing comprehensive quality measures for CRC screening. Such comprehensive measures will be of value to patients and to payers. Second, assessing quality of care more comprehensively has traditionally been infeasible. For example, incorporating life expectancy into quality measures requires electronic assessment of health status.

Traditionally, such efforts have been hampered by the lack of systematic clinical data collection. However, as meaningful use of electronic health records increases, measures that incorporate such information are likely to become increasingly feasible. Finally, we also need to consider how to make these improvements while avoiding measure proliferation. Proliferation leads to provider fatigue and discourages thoughtful clinical decision making, potentially worsening quality of care. Creative approaches, such as rotating measure sets over time, use of clinical decision support tools, and balancing underuse measures with overuse measures, may be warranted. Additionally, composite measures may prove to be more meaningful and more practical for patients, providers, and payers. Ultimately, a distinction must be made between quality assurance and quality improvement; both are important, but the types of measures and the level of measure sophistication used in each program undoubtedly vary.

In summary, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for high-quality CRC screening that extends beyond simply providing a high-quality colonoscopy. This broader view of quality benefits patients by ensuring that our expertise informs the metrics by which delivery of CRC screening is measured. It also ensures that we hold ourselves and our colleagues to the highest standards across the continuum of care. Additionally, as alternative payment models and value-based contracting are implemented, nonendoscopic screening methods will likely become more commonplace. Advocating for high-quality nonendoscopic screening will help maintain gastroenterologists’ role as the stewards of CRC screening and digestive health. Although operationalizing measure concepts such as those proposed here may be difficult, it is critical if we are to provide the best possible care for our patients.

References

1. Sabatino, S.A., White, M.C., Thompson, T.D., et al. Cancer screening test use – United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:464-8.

2. Anderson, A.E., Henry, K.A., Samadder, N.J., et al. Rural vs urban residence affects risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:526-33.

3. Walter, L.C., Lindquist, K., Nugent, S., et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:465-73.

4. Murphy, C.C., Sandler, R.S., Grubber, J.M., et al. Underuse and overuse of colonoscopy for repeat screening and surveillance in the Veterans Health Administration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:436-44.

5. Mittal, S., Lin, Y.-L., Tan, A., et al. Limited life expectancy among a subgroup of Medicare beneficiaries receiving screening colonoscopies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:443-50.e1

6. Allen, J.I. Quality measures for colonoscopy: where should we be in 2015?. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:10.

7. Fisher, D.A., Jeffreys, A., Coffman, C.J., et al. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:1232-5.

8. Saini, S.D., van Hees, F., Vijan, S. Smarter screening for cancer: possibilities and challenges of personalization. JAMA. 2014;312:2211-2.

9. Saini, S.D., Vijan, S., Schoenfeld, P., et al. Role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1247.

10. Inadomi, J.M., Vijan, S., Janz, N.K., et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:575-82.

11. Writing Committee Members, Drozda, J.P., Ferguson, T.B., et al. 2015 ACC/AHA focused update of secondary prevention lipid performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:558-87.

Dr. Saini is a research scientist at the VA Center for Clinical Management Research and an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Adams is a clinical lecturer in the division of gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, and a research investigator, VA Center for Clinical Management Research; Dr. Brill is the chief medical officer of Predictive Health, Paradise Valley, Ariz., and a clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix; Dr. Gupta is codirector of Digestive Health Center, director of interventional endoscopy, and associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola University Medical Center; Dr. Naveed is a clinical assistant professor in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; Dr. Rosenberg is at Illinois Gastroenterology Group; and Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C. Dr. Saini’s and Dr. Gellad’s research is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Awards (CDA 09-213-2 and CDA 14-158). Dr. Gupta has received research support from Cook Medical, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, and CDx Diagnostics.

Medicine in the United States is undergoing fundamental changes that will continue despite 2016 presidential election results. Changes include consolidation of provider networks, movement from volume- to value-based reimbursement, demands for price and quality transparency, and a shift from focusing solely on individual physician-patient interactions to a broader triple aim focus that incorporates individual patients, population, health, and cost. In this month’s column, Sameer Saini and colleagues suggest that we broaden our view of colorectal cancer screening quality metrics from a colonoscopy-centric focus to a focus on the bottom line: Do we reduce cancer in the population of patients that we serve? When we extend our view to a population level, we use current colonoscopy registries only as internal process controls. A successful health system will develop a mechanism to assess and demonstrate how well the collective team of providers accomplishes the only outcome that matters to patients: preventing colon cancer.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is one of the most valuable services provided by gastroenterologists. The evidence that screening “works” on a population level is undeniable. But not every screening program is equally effective. Data indicate ongoing underuse of screening, particularly in high-risk, vulnerable, and minority communities.1,2 Other data indicate that screening is overused, particularly in low-risk patients and in those with limited life expectancy.3-5 It is also known that endoscopist skill plays an important role in the effectiveness of screening. In short, there is ample room for improvement in the quality of CRC screening, and payers and the public have taken notice. Unsurprisingly, gastroenterologists are often focused on procedural quality indicators, such as adenoma detection and cecal intubation rates.6 These endoscopic quality measures are important indicators of high-quality colonoscopy, but colonoscopy is the common touch point of a much broader system of care that includes other screening tests and other providers (e.g., primary care providers [PCPs], pathologists, and anesthesiologists). Coordinating care across this system is essential for improving the health of patients. As the stewards of digestive health, we owe it to our patients to take a more comprehensive view of CRC screening quality and move beyond colonoscopy alone.

The complex web of care that comprises CRC screening is shown schematically in Figure 1. Appropriate screening begins with selection of suitable screening candidates. In the United States, where most screening is initiated during a clinician encounter, this important task falls primarily on the shoulders of PCPs. It is typically the role of the PCP to assess the two key patient factors that determine screening benefit: CRC risk (using personal and family history) and life expectancy (using age and overall health status). Once a patient has been deemed an appropriate candidate for screening, an acceptable screening test must be selected. Here, patient and practitioner are faced with a menu of options, including fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), colonoscopy, multitarget stool DNA, and computed tomography colonography. For average-risk screening, the ideal test depends primarily on patient preference and local availability.

If a screening test other than colonoscopy is selected, it becomes critical that a positive test is followed by timely and high-quality colonoscopy. High-quality colonoscopy begins with evidence-based preprocedure education and preparation, including appropriate selection of anesthesia services. Once a patient has been well prepared and adequately sedated, an endoscopist must carefully examine the colonic mucosa and completely resect any suspicious polyps. Unless discarded, resected polyps must be reviewed and categorized by a pathologist, including appropriate identification of serrated polyps. Finally, pathology results must be correctly interpreted by the clinician, with evidence-based follow-up recommendations made and effectively communicated to the patient and the referring provider. Additionally, in the short term, delayed gastrointestinal (GI) and non-GI complications of colonoscopy must be recognized and appropriately addressed. In the long term, the rate of interval cancers must be monitored.

Recognizing the importance of CRC screening, GI specialty societies have proposed a variety of quality measures to ensure that patients receive high-quality and high-value colonoscopy. Several of these measures have been adopted by CMS as part of the Physician Quality Reporting System. Non-GI groups, such as the National Center for Quality Assurance and the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, have also proposed their own CRC screening–related measures.

Despite the proliferation of measures in the domain of CRC screening, current measures fall short in several ways. First, they are largely focused on colonoscopy technical performance, with less attention paid to the important steps that occur before and after colonoscopy. For example, the existing Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure for underuse of CRC screening assesses the proportion of patients in a health plan between the ages 50 and 75 who are up to date for CRC screening. This measure is satisfied if a patient completes FOBT, regardless of the result. But FOBT alone is not sufficient to reduce mortality from CRC. Rather, it is imperative that a positive FOBT test be followed by colonoscopy. Numerous studies suggest a quality gap in this critical referral step.7

Yet, outside of selected clinical settings (e.g., the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System), no existing quality measure focuses on colonoscopy completion after positive FOBT. Other examples of important performance gaps beyond colonoscopy technical performance include appropriate use of monitored anesthesia care (data suggest overuse) and appropriate pathology interpretation (data suggest variation in the interpretation of serrated lesions, some of which are associated with increased risk of CRC).

Second, existing measures fail to consider individual patient factors that are known to be predictive of screening benefit, such as life expectancy and personal or familial cancer risk.8

Returning to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure as an example, this measure relies on age alone to identify patients who are candidates for screening. Yet, it is widely recognized that life expectancy is a critically important factor when considering screening, particularly in older patients. However, existing measures fail to incorporate estimates of life expectancy. As a result, clinicians are encouraged to screen based on age alone. Data suggest that this leads to overuse in older, sicker patients younger than age 75 (the age cutoff suggested by guidelines and incorporated into the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measure) and underuse in healthy and unscreened patients older than age 75.9

Furthermore, existing measures fail to systematically consider patient preferences and undervalue shared decision making. Data suggest, for instance, that patients who are offered a “menu” of options for screening rather than a single screening test are more likely to complete a screening test.10

But existing measures do not consider whether a physician assessed a patient’s preferences, or offered more than one screening option. Of course, measuring the quality of decision making is an evolving science that presents challenges and requires creative solutions.11

Finally, existing measures do not capture the collaborative nature of modern health care. For example, most existing measures focus on the performance of gastroenterologists and GI practices. Although such a focus is appropriate for specialty-specific quality improvement efforts, it neglects to capture the important interactions and hand-offs between providers needed for successful completion of screening (and downstream reduction in cancer mortality). As a result, this specialty-focused approach fails to meet the needs of patients, who are increasingly interested in whether the care they receive is improving their health regardless of who provides it. It also fails to meet the needs of payers, who are interested in whether a network of providers is delivering high-value care for its members. Developing measures that capture the collaborative nature of modern health care becomes increasingly important as payers embrace alternative payment models and other value-based reimbursement systems.

Given these challenges with existing measures, we propose the following concepts for consideration as noncolonoscopy quality measures of CRC screening:

1. Appropriateness of referral for CRC screening (PCP): Measures in this domain should incorporate assessment of family history, prior screening history, and/or life expectancy, all of which are predictive of screening benefit and can be extracted from structured electronic health record data.

2. Shared decision making in choosing a CRC screening test (PCP): Currently, measures in this domain are (by necessity) relatively simple, such as assessment of documentation of whether stool testing was offered alongside colonoscopy during a clinic visit.

3. Percentage of individuals with a positive noncolonoscopy CRC screening test who complete a colonoscopy within 6 months (PCP and GI): A measure in this domain can be developed and implemented using existing infrastructure. The Veterans Affairs Healthcare System currently uses such a measure to monitor appropriate follow-up of positive fecal immunochemical tests.

4. Predicted reduction in CRC mortality: This measure, which provides an estimate of the effectiveness and value of a screening program, represents the “bottom line” that is ultimately of interest to both patients and payers. However, composite measures that use projected results require sophisticated statistical approaches and case-mix adjustment. They must also contend with “churn” in the covered population.

Although a more comprehensive view of screening is desirable, operationalizing measure concepts, such as those proposed previously, is challenging for several reasons. First, as we have outlined, CRC screening is truly a “team sport.” The stakeholders in CRC screening include public health, primary care, gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, oncology, anesthesiology, and pathology practitioners. As a result, screening has no natural and obvious steward. Rather, various components of care are adopted by different specialty groups, and this approach leads to unmonitored gaps in care. We believe that gastroenterologists can and should take the lead in developing comprehensive quality measures for CRC screening. Such comprehensive measures will be of value to patients and to payers. Second, assessing quality of care more comprehensively has traditionally been infeasible. For example, incorporating life expectancy into quality measures requires electronic assessment of health status.

Traditionally, such efforts have been hampered by the lack of systematic clinical data collection. However, as meaningful use of electronic health records increases, measures that incorporate such information are likely to become increasingly feasible. Finally, we also need to consider how to make these improvements while avoiding measure proliferation. Proliferation leads to provider fatigue and discourages thoughtful clinical decision making, potentially worsening quality of care. Creative approaches, such as rotating measure sets over time, use of clinical decision support tools, and balancing underuse measures with overuse measures, may be warranted. Additionally, composite measures may prove to be more meaningful and more practical for patients, providers, and payers. Ultimately, a distinction must be made between quality assurance and quality improvement; both are important, but the types of measures and the level of measure sophistication used in each program undoubtedly vary.

In summary, gastroenterologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for high-quality CRC screening that extends beyond simply providing a high-quality colonoscopy. This broader view of quality benefits patients by ensuring that our expertise informs the metrics by which delivery of CRC screening is measured. It also ensures that we hold ourselves and our colleagues to the highest standards across the continuum of care. Additionally, as alternative payment models and value-based contracting are implemented, nonendoscopic screening methods will likely become more commonplace. Advocating for high-quality nonendoscopic screening will help maintain gastroenterologists’ role as the stewards of CRC screening and digestive health. Although operationalizing measure concepts such as those proposed here may be difficult, it is critical if we are to provide the best possible care for our patients.

References

1. Sabatino, S.A., White, M.C., Thompson, T.D., et al. Cancer screening test use – United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:464-8.

2. Anderson, A.E., Henry, K.A., Samadder, N.J., et al. Rural vs urban residence affects risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:526-33.

3. Walter, L.C., Lindquist, K., Nugent, S., et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:465-73.

4. Murphy, C.C., Sandler, R.S., Grubber, J.M., et al. Underuse and overuse of colonoscopy for repeat screening and surveillance in the Veterans Health Administration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:436-44.

5. Mittal, S., Lin, Y.-L., Tan, A., et al. Limited life expectancy among a subgroup of Medicare beneficiaries receiving screening colonoscopies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:443-50.e1

6. Allen, J.I. Quality measures for colonoscopy: where should we be in 2015?. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:10.

7. Fisher, D.A., Jeffreys, A., Coffman, C.J., et al. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:1232-5.

8. Saini, S.D., van Hees, F., Vijan, S. Smarter screening for cancer: possibilities and challenges of personalization. JAMA. 2014;312:2211-2.

9. Saini, S.D., Vijan, S., Schoenfeld, P., et al. Role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1247.

10. Inadomi, J.M., Vijan, S., Janz, N.K., et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:575-82.

11. Writing Committee Members, Drozda, J.P., Ferguson, T.B., et al. 2015 ACC/AHA focused update of secondary prevention lipid performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:558-87.

Dr. Saini is a research scientist at the VA Center for Clinical Management Research and an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Dr. Adams is a clinical lecturer in the division of gastroenterology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, and a research investigator, VA Center for Clinical Management Research; Dr. Brill is the chief medical officer of Predictive Health, Paradise Valley, Ariz., and a clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix; Dr. Gupta is codirector of Digestive Health Center, director of interventional endoscopy, and associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola University Medical Center; Dr. Naveed is a clinical assistant professor in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; Dr. Rosenberg is at Illinois Gastroenterology Group; and Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C. Dr. Saini’s and Dr. Gellad’s research is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Awards (CDA 09-213-2 and CDA 14-158). Dr. Gupta has received research support from Cook Medical, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, and CDx Diagnostics.

Cyber insurance and practice compliance – now is the time to get covered

Electronic health record systems have become an essential component of most medical practices. Whether you are working at a hospital, an ASC or in your office, you’re working in a digital world. This will only expand as health information exchanges and patient portals are implemented. In this digital age, practice comes with significant risk of "cyber attack," which could result in a breach of protected health information (PHI) and the associated penalties. As of December 2012, there were almost 500 breaches of more than 21 million patient records. Since July 2011, physician practices have been the most breached organizational type.

Internal processes to prevent breaches of data are imperative for your practice. Do you have a designated HIPAA security professional? Who in your practice is knowledgeable of cyber security? Do you perform background security checks on prospective employees? Are you using cellphones to transmit PHI to other members of your practice?

Physicians are required to develop and maintain a compliance program in their practice under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While the federal government has yet to release guidelines on what these compliance programs should look like, Section 6401 of the ACA requires that all providers and suppliers institute formal compliance programs. New practices will no longer be able to enroll in Medicare or Medicaid without a compliance program in place, and existing practices also will be expected to institute them.

Even the most technologically advanced practices can be vulnerable to a cyber-breach. As part of your compliance program, do you have cyber insurance to protect your practice from this liability? The basic components of cyber insurance are detailed in this table. Contact your liability/medical malpractice carriers to see if you are covered.

Electronic health record systems have become an essential component of most medical practices. Whether you are working at a hospital, an ASC or in your office, you’re working in a digital world. This will only expand as health information exchanges and patient portals are implemented. In this digital age, practice comes with significant risk of "cyber attack," which could result in a breach of protected health information (PHI) and the associated penalties. As of December 2012, there were almost 500 breaches of more than 21 million patient records. Since July 2011, physician practices have been the most breached organizational type.

Internal processes to prevent breaches of data are imperative for your practice. Do you have a designated HIPAA security professional? Who in your practice is knowledgeable of cyber security? Do you perform background security checks on prospective employees? Are you using cellphones to transmit PHI to other members of your practice?

Physicians are required to develop and maintain a compliance program in their practice under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While the federal government has yet to release guidelines on what these compliance programs should look like, Section 6401 of the ACA requires that all providers and suppliers institute formal compliance programs. New practices will no longer be able to enroll in Medicare or Medicaid without a compliance program in place, and existing practices also will be expected to institute them.

Even the most technologically advanced practices can be vulnerable to a cyber-breach. As part of your compliance program, do you have cyber insurance to protect your practice from this liability? The basic components of cyber insurance are detailed in this table. Contact your liability/medical malpractice carriers to see if you are covered.

Electronic health record systems have become an essential component of most medical practices. Whether you are working at a hospital, an ASC or in your office, you’re working in a digital world. This will only expand as health information exchanges and patient portals are implemented. In this digital age, practice comes with significant risk of "cyber attack," which could result in a breach of protected health information (PHI) and the associated penalties. As of December 2012, there were almost 500 breaches of more than 21 million patient records. Since July 2011, physician practices have been the most breached organizational type.

Internal processes to prevent breaches of data are imperative for your practice. Do you have a designated HIPAA security professional? Who in your practice is knowledgeable of cyber security? Do you perform background security checks on prospective employees? Are you using cellphones to transmit PHI to other members of your practice?

Physicians are required to develop and maintain a compliance program in their practice under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While the federal government has yet to release guidelines on what these compliance programs should look like, Section 6401 of the ACA requires that all providers and suppliers institute formal compliance programs. New practices will no longer be able to enroll in Medicare or Medicaid without a compliance program in place, and existing practices also will be expected to institute them.

Even the most technologically advanced practices can be vulnerable to a cyber-breach. As part of your compliance program, do you have cyber insurance to protect your practice from this liability? The basic components of cyber insurance are detailed in this table. Contact your liability/medical malpractice carriers to see if you are covered.

QRUR reports will be key in deciding Medicare pay

The Medicare Physician Feedback Program provides physicians with comparative information about the quality and cost of care delivered to their Medicare fee-for-service patients through feedback reports known as Quality Resource and Use Reports (QRUR).

Why are QRURs important?

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) directed the Health and Human Services Secretary to develop and implement a budget-neutral payment modifier that will adjust Medicare physician payments based on the relative quality and costs of care provided. Quality and cost measures will be risk adjusted, geographically standardized, and should promote systems-based care. The Medicare Physician Feedback Program serves as the foundation for the modifier.

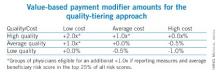

In the 2013 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule published in November of 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first phase toward implementation of the value-based payment modifier. Initially, the value modifier will be applied to group practices of 100 or more eligible professionals – about 1,100 groups nationally. These groups will be able to elect how their payment modifier will be calculated. This will affect payment in 2015 based on 2013 performance. Smaller groups of 2-99 eligible professionals will remain unaffected during the first reporting year. However, CMS is required by statute to apply the modifier to all physicians by 2017. In the future, CMS will be using QRURs to provide all physicians with information about how the value modifier will affect their payment.

The QRURs provide comparative quality and cost data for quality improvement purposes. This is the first time that many physicians will have seen such performance information from CMS. The report previews quality and cost measures that will be used in the value modifier. The report can count as one of the group options to fulfill the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) requirement for group reporting and also for the value modifier.

How will QRURs impact the value modifier?

Groups of physicians with 100 or more eligible professionals will have the option of either zero adjustment, a minus one adjustment, or will elect quality tiering calculation based on their PQRS participation. To be a successful PQRS reporter, groups must have registered and will report at least one measure for the Group Practice Reporting Option (GPRO) Web interface, CMS-approved registries, or the administrative claims option that includes administrative claims performance, quality performance measures that will be calculated by CMS. These groups will have the option of having zero adjustment for the value modifier applied to them or the option to elect a quality tiering calculation in which there would be an upward or a downward adjustment (or no adjustment) based on the quality tiering.

Overview of how CMS will calculate the value modifier

Groups that decide that the amount of downward adjustment is not worth the effort or do not wish to participate in PQRS reporting will be considered non-PQRS reporters. Non-PQRS reporters will be subject to a minus 1% downward adjustment of the value modifier and a minus 1.5% downward adjustment for PQRS; note that the amount of downward adjustment is additive for the two programs.

For the value modifier, physicians elect one of three possible group practice options. One option is the Web-based interface that is largely primary care and preventive measures. The second option is to select measures from a registry. The third option is the administrative claim option calculated by CMS. For the first two options, physicians choose which option for quality measures goes into the quality composite of the value modifier. Physicians who choose the administrative claims method are not allowed to choose which measures will be examined for the value modifier.

How is the value modifier calculated?

The value modifier is calculated at the group or taxpayer identification number (TIN) level. The attribution method focuses on the delivery of primary services through a two-step process. The first step identifies whether a physician is in primary care. Beneficiaries are attributed based on those who have had at least one primary care physician (PCP) in service. CMS then examines whether the PCP(s) delivered the plurality of care. The second step checks if the TIN provided the plurality of the primary care services by nonprimary care physicians.

There are five cost measures grouped into two domains: total overall cost or the total per capita measure. The reports examine the total cost of beneficiaries with specific conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and heart failure. Each measure within each domain is weighted equally and each domain is weighted equally to form a cost composite.

CMS will be tiering the two composites – quality of care and cost of care – based on the group’s standardized performance as compared to national benchmarks. High-cost/ low-quality providers will have a downward adjustment of minus 1% – the same downward adjustment as non-PQRS reporters (see table). High-quality/low-cost, high-quality/average-cost, or average-quality/low-cost providers will have an upward adjustment. As this is a budget-neutral program, until CMS knows how much money is in the pot from those who are not reporting or received downward adjustments, Medicare will not be able to calculate how much money will be distributed for those receiving an upward adjustment.

Groups are eligible for an additional 1% if reporting clinical data for quality measures for an average beneficiary risk score is in the top 25% of all beneficiary risk scores. So, those groups who perform at high levels and have a complex patient population would receive an additional 1% to their value modifier.

I have my QRUR, but how do I read it?