User login

2020 Update on Menopause

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to the bothersome symptoms and physical findings associated with estrogen deficiency that involve the labia, vestibular tissue, clitoris, vagina, urethra, and bladder.1 GSM is associated with genital irritation, dryness, and burning; urinary symptoms including urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections; and sexual symptoms including vaginal dryness and pain. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) represents a component of GSM.

GSM is highly prevalent, affecting more than three-quarters of menopausal women. In contrast to menopausal vasomotor symptoms, which often are most severe and frequent in recently menopausal women, GSM commonly presents years following menopause. Unfortunately, VVA symptoms may have a substantial negative impact on women’s quality of life.

In this 2020 Menopause Update, I review a large observational study that provides reassurance to clinicians and patients regarding the safety of the best-studied prescription treatment for GSM—vaginal estrogen. Because some women should not use vaginal estrogen and others choose not to use it, nonhormonal management of GSM is important. Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton provides details on a randomized clinical trial that compared the use of fractionated CO2 laser therapy with vaginal estrogen for the treatment of GSM. In addition, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses recent studies that found lower health risks with vaginal estrogen use compared with systemic estrogen therapy.

Diagnosing GSM

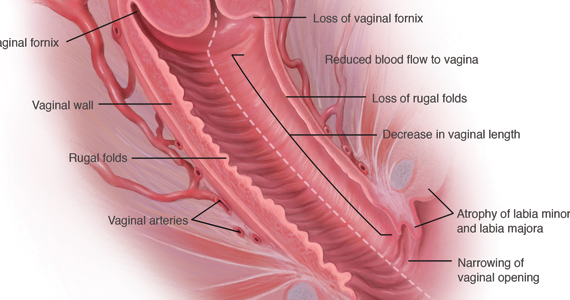

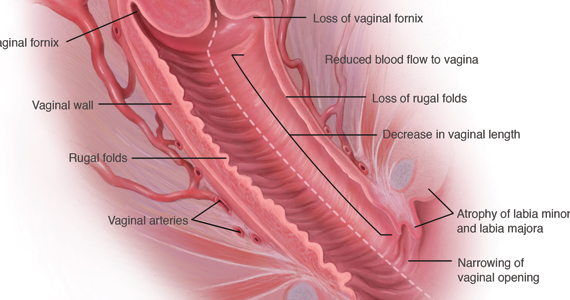

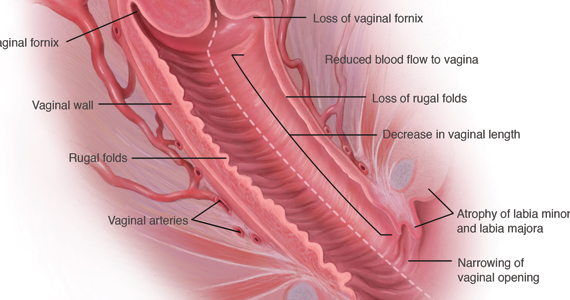

GSM can be diagnosed presumptively based on a characteristic history in a menopausal patient. Performing a pelvic examination, however, allows clinicians to exclude other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, such as lichen sclerosus, Candida infection, and malignancy.

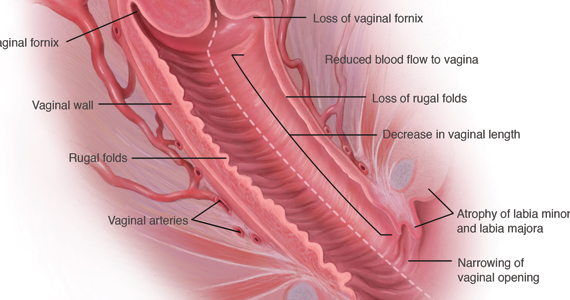

During inspection of the external genitalia, the clinician may note loss of the fat pad in the labia majora and mons as well as a reduction in labia minora pigmentation and tissue. The urethral meatus often becomes erythematous and prominent. If vaginal or introital narrowing is present, use of a pediatric (ultrathin) speculum reduces patient discomfort. The vaginal mucosa may appear smooth due to loss of rugation; it also may appear shiny and dry. Bleeding (friability) on contact with a spatula or cotton-tipped swab may occur. In addition, the vaginal fornices may become attenuated, leaving the cervix flush with the vaginal apex.

GSM can be diagnosed without laboratory assessment. However, vaginal pH, if measured, is characteristically higher than 5.0; microscopic wet prep often reveals many white blood cells, immature epithelial cells (large nuclei), and reduced or absent lactobacilli.2

Nonhormonal management of GSM

Water, silicone-based, and oil-based lubricants reduce the friction and discomfort associated with sexual activity. By contrast, vaginal moisturizers act longer than lubricants and can be applied several times weekly or daily. Natural oils, including olive and coconut oil, may be useful both as lubricants and as moisturizers. Aqueous lidocaine 4%, applied to vestibular tissue with cotton balls prior to penetration, reduces dyspareunia in women with GSM.3

Vaginal estrogen therapy

When nonhormonal management does not sufficiently reduce GSM symptoms, use of low-dose vaginal estrogen enhances thickness and elasticity of genital tissue and improves vaginal blood flow. Vaginal estrogen creams, tablets, an insert, and a ring are marketed in the United States. Although clinical improvement may be apparent within several weeks of initiating vaginal estrogen, the full benefit of treatment becomes apparent after 2 to 3 months.3

Despite the availability and effectiveness of low-dose vaginal estrogen, fears regarding the safety of menopausal hormone therapy have resulted in the underutilization of vaginal estrogen.4,5 Unfortunately, the package labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen can exacerbate these fears.

Continue to: Nurses’ Health Study report...

Nurses’ Health Study report provides reassurance on long-term safety of vaginal estrogen

Bhupathiraju SN, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. Vaginal estrogen use and chronic disease risk in the Nurses’ Health Study. Menopause. 2018;26:603-610

Bhupathiraju and colleagues published a report from the long-running Nurses’ Health prospective cohort study on the health outcomes associated with the use of vaginal estrogen.

Recap of the study

Starting in 1982, participants in the Nurses’Health Study were asked to report their use of vaginal estrogen via a validated questionnaire. For the years 1982 to 2012, investigators analyzed data from 896 and 52,901 women who had and had not used vaginal estrogen, respectively. The mean duration of vaginal estrogen use was 36 months.

In an analysis adjusted for numerous factors, the investigators observed no statistically significant differences in risk for cardiovascular outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism) or invasive cancers (colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, or breast).

Findings uphold safety of vaginal estrogen

This landmark study provides reassurance that 3 years of use of vaginal estrogen does not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer, findings that hopefully will allow clinicians and women to feel comfortable regarding the safety of vaginal estrogen. A study of vaginal estrogen from the Women’s Health Initiative provided similar reassurance. Recent research supports guidance from The North American Menopause Society and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal estrogen can be used indefinitely, if indicated, and that use of concomitant progestin is not recommended in women who use vaginal estrogen and have an intact uterus.6,7

I agree with the authors, who point out that since treatment of GSM may need to be continued long term (even indefinitely), it would be helpful to have data that assessed the safety of longer-duration use of vaginal estrogen.

Results from Bhupathiraju and colleagues’ analysis of data from the Nurses’ Health Study on the 3-year safety of vaginal estrogen use encourage clinicians to recommend and women to use this safe and effective treatment for GSM.

How CO2 fractionated vaginal laser therapy compares with vaginal estrogen for relief of GSM symptoms

Paraiso MF, Ferrando CA, Sokol ER, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the VeLVET trial. Menopause. 2020;27:50-56.

Up to 50% to 60% of postmenopausal women experience GSM symptoms. However, many fewer receive treatment, either because they do not understand that the symptoms are related to menopause or they are not aware that safe and effective treatment is available. Sadly, many women are not asked about their symptoms or are embarrassed to tell providers.

GSM affects relationships and quality of life. Vaginal lubricants or moisturizers may provide relief. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies include low-dose vaginal estrogen, available as a vaginal tablet, cream, suppository, and ring; intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA); and oral ospemifene, a selective estrogen replacement modulator. If women have an estrogen-sensitive breast or uterine cancer, an oncologist should be involved in decisions about vaginal hormonal therapy.

Energy-based devices such as vaginal lasers appear to induce wound healing; stimulate collagen and elastin fiber formation through increased storage of glycogen; and activate fibroblasts, which leads to increased extracellular matrix and restoration of vaginal pH.

These lasers are FDA approved for use in gynecology but not specifically for the treatment of GSM. In July 2016, the FDA issued a safety alert that energy-based devices, while approved for use in gynecology, have not been approved or adequately tested for menopausal vaginal conditions, and safety concerns include reports of vaginal burns.8 Lacking are publications of adequately powered randomized, sham-con-trolled trials to determine if laser therapy works better for women with GSM than placebos, moisturizers, or vaginal hormone therapies.

Recently, investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized, single-blinded trial of vaginal laser therapy and estrogen cream for treatment of GSM.

Continue to: Details of the study...

Details of the study

Paraiso and colleagues aimed to compare the 6-month efficacy and safety of fractionated CO2 vaginal laser therapy with that of estrogen vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal dryness/GSM.

Participants randomly assigned to the estrogen therapy arm applied conjugated estrogen cream 0.5 g vaginally daily for 14 days, followed by twice weekly application for 24 weeks (a low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy). Participants randomly assigned to laser therapy underwent 3 vaginal treatments at a minimum of 6 weeks apart.

Sixty-nine women were enrolled in the trial before enrollment was closed because the FDA required that the sponsor obtain and maintain an investigational device exemption. Of 62 women who completed 6 months’ treatment, 30 received 3 laser treatments and 32 received estrogen cream.

The primary outcome compared subjective improvement in vaginal dryness using the visual analog scale (VAS) between the 2 groups at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included comparisons of the vaginal health index (VHI) and vaginal maturation index (VMI), the effect of GSM on quality of life, the effect of treatment on sexual function and urinary symptoms, and patient satisfaction.

Study findings

Efficacy. Laser therapy and estrogen therapy were found to be similarly effective except on the VMI, which favored estrogen. On patient global impression, 85.8% of laser-treated women rated their improvement as ‘‘better or much better’’ and 78.5% reported being either ‘‘satisfied or very satisfied,’’ compared with 70% and 73.3%, respectively, in the estrogen group, a statistically nonsignificant difference.

On linear regression, the investigators found a nonsignificant mean difference in female sexual function index scores. While VMI scores remained higher in the estrogen-treated group (adjusted P = .02), baseline and 6-month follow-up VMI data were available for only 34 participants (16 laser treated, 18 estrogen treated).

Regarding long-term effectiveness, 20% to 25% of the women in the laser-treated group needed further treatment after 1 year while the estrogen cream continued to work as long as it was used as prescribed.

Adverse effects. The incidence of vaginal bleeding was similar in the 2 groups: 6.7% in the laser group and 6.3% in the estrogen group. In the laser therapy group, 3% expe-rienced vaginal pain, discharge, and bladder infections, while in the estrogen cream group, 3% reported breast tenderness, migraine headaches, and abdominal cramping.

Takeaways. This small randomized, open-label (not blinded) trial provides pilot data on the effectiveness of vaginal CO2 laser compared with vaginal estrogen in treating vaginal atrophy, quality-of-life symptoms, sexual function, and urinary symptoms. Adverse events were minimal. Patient global impression of improvement and satisfaction improved for both vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen therapy.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

To show noninferiority of vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen, 196 study participants were needed. However, after 38% had been enrolled, the FDA sent a warning letter to the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which required obtainment of an investigational device exemption for the laser and addition of a sham treatment arm.9 Instead of redesigning the trial and reconsenting the participants, the investigators closed the study, and analysis was performed only on the 62 participants who completed the study; vaginal maturation was assessed only in 34 participants.

The study lacked a placebo or sham control, which increases the risk of bias, while small numbers limit the strength of the findings. Longer-term evaluation of the effects of laser therapy beyond 6 months is needed to allow assessment of the effects of scarring on vaginal health, sexual function, and urinary issues.

Discussing therapy with patients

Despite this study’s preliminary findings, and until more robust data are available, providers should discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, FDA-approved vaginal hormone therapies (such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone), and systemic therapies, such as hormone therapy and ospemifene, to determine the best treatment for the individual woman with GSM.

In a healthy postmenopausal woman with bothersome GSM symptoms not responsive to lubricants and moisturizers, I recommend FDA-approved vaginal therapies as first-line treatment if there are no contraindications. For women with breast cancer, I involve their oncologist. If a patient asks about vaginal laser treatment, I share that vaginal energy-based therapies, such as the vaginal laser, have not been approved for menopausal vaginal concerns. In addition to the possibility of adverse events or unsuccessful treatment, there are significant out-of-pocket costs and the potential need for ongoing therapy after the initial 3 laser treatments.

For GSM that does not respond to lubricants and moisturizers, many FDA-approved vaginal and systemic therapies are available to treat vaginal symptoms. Vaginal laser treatment is a promising therapy for vaginal symptoms of GSM that needs further testing to determine its efficacy, safety, and long-term effects. If discussing vaginal energy-based therapies with patients, include the current lack of FDA approval for specific vaginal indications, potential adverse effects, the need for ongoing retreatment, and out-of-pocket costs.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

Having more appropriate, evidence-based labeling of low-dose vaginal estrogen continues to be a high priority for The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), and other professional societies.

NAMS and the Working Group on Women’s Health and Well-Being in Menopause had submitted a citizen’s petition to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 requesting modification of the label—including removal of the “black box warning”—for low-dose vaginal estrogen products. The petition was, disappointingly, denied in 2018.1

Currently, the class labeling, which was based on the results of randomized trials with systemic hormone therapy, is not applicable to low-dose vaginal estrogen, and the inclusion of the black box warning has led to serious underutilization of an effective and safe treatment for a very common and life-altering condition, the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). This condition affects nearly half of postmenopausal women. It tends to be chronic and progressive and, unlike hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it does not remit or decline over time, and it affects women’s health and quality of life.

While removal of the black box warning would be appropriate, labeling should include emphatic reminders for women that if they have any bleeding or spotting they should seek medical attention immediately, and if they have a history of breast cancer or other estrogen-sensitive cancers they should talk with their oncologist prior to starting treatment with low-dose vaginal estrogen. Although the text would still inform women of research results on systemic hormone therapy, it would explain the differences between low-dose vaginal estrogen and systemic therapy.

Studies show vaginal estrogen has good safety profile

In the last several years, large, observational studies of low-dose vaginal estrogen have suggested that this treatment is not associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, venous thrombosis, cancer, or dementia—conditions listed in the black box warning that were linked to systemic estrogen therapy plus synthetic progestin. Recent data from the Nurses’ Health Study, for example, demonstrated that 3 years of vaginal estrogen use did not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer.

Women’s Health Initiative. In a prospective observational cohort study, Crandall and colleagues used data from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study to determine the association between use of vaginal estrogen and risk of a global index event (GIE), defined as time to first occurrence of coronary heart disease, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, hip fracture, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, or death from any cause.2

Women were recruited from multiple clinical centers, were aged 50 to 79 years at baseline, and did not use systemic estrogen therapy during follow-up. The study included 45,663 women and median follow-up was 7.2 years. The investigators collected data on women’s self-reported use of vaginal estrogen as well as the development of the conditions defined above.

In women with a uterus, there was no significant difference between vaginal estrogen users and nonusers in the risk of stroke, invasive breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis. The risks of coronary heart disease, fracture, all-cause mortality, and GIE were lower in vaginal estrogen users than in nonusers (GIE adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55–0.86).

In women who had undergone hysterectomy, the risks of the individual GIE components and the overall GIE were not significantly different in users of vaginal estrogen compared with nonusers (GIE adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70–1.26).

The investigators concluded that the risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer were not increased in postmenopausal women who used vaginal estrogen. Thus, this study offers reassurance on the treatment’s safety.2

Meta-analysis on menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk. Further evidence now indicates that low-dose vaginal estrogen is not linked to chronic health conditions. In a large meta-analysis published in 2019, investigators looked at different types of hormone therapies—oral estrogen plus progestin, transdermal estrogen and progestin, estrogen alone, low-dose vaginal estrogen—and their relationship to breast cancer risk.3

Information on individual participants was obtained from 58 studies, 24 prospective and 34 retrospective. Breast cancer relative risks (RR) during years 5 to 14 of current hormone use were assessed according to the main hormonal contituents, doses, and modes of delivery of the last-used menopausal hormone therapy. For all systemic estrogen-only preparations, the RR was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.28–1.38), while for all estrogen-progestogen preparations, the RR was 2.08 (95% CI, 2.02–2.15). For transdermal estrogen, the RR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.25–1.46). In contrast, for vaginal estrogen, the RR was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97–1.23).3

Thus, the analysis found that in all the studies that had been done to date, there was no evidence of increased risk of breast cancer with vaginal estrogen therapy.

The evidence is growing that low-dose vaginal estrogen is different from systemic estrogen in terms of its safety profile and benefit-risk pattern. It is important for the FDA to consider these data and revise the vaginal estrogen label.

On the horizon: New estradiol reference ranges

It would be useful if we could accurately compare estradiol levels in women treated with vaginal estrogen against those of women treated with systemic estrogen therapy. In September 2019, NAMS held a workshop with the goal of establishing reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women.4 It is very important to have good, reliable laboratory assays for estradiol and estrone, and to have a clear understanding of what is a reference range, that is, the range of estradiol levels in postmenopausal women who are not treated with estrogen. That way, you can observe what the estradiol blood levels are in women treated with low-dose vaginal estrogen or those treated with systemic estrogen versus the levels observed among postmenopausal women not receiving any estrogen product.

With the reference range information, we could look at data on the blood levels of estradiol with low-dose vaginal estrogen from the various studies available, as well as the increasing evidence from observational studies of the safety of low-dose vaginal estrogen to better understand its relationship with health. If these studies demonstrate that, with certain doses and formulations of low-dose vaginal estrogen, blood estradiol levels stay within the reference range of postmenopausal estradiol levels, it would inform the labeling modifications of these products. We need this information for future discussions with the FDA.

The laboratory assay technology used for such an investigation is primarily liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry, the so-called LC-MS/MS assay. With use of this technology, the reference range for estradiol may be less than 10 picograms per milliliter. Previously, a very wide and inconsistent range—about 5 to 30 picograms per milliliter—was considered a “normal” range.

NAMS is championing the efforts to define a true evidence-based reference range that would represent the range of levels seen in postmenopausal women.5 This effort has been spearheaded by Dr. Richard Santen and colleagues. Using the more sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS assay will enable researchers and clinicians to better understand how levels on low-dose vaginal estrogen relate to the reference range for postmenopausal women. We are hoping to work together with researchers to establish these reference ranges, and to use that information to look at how low-dose vaginal estrogen compares to levels in untreated postmenopausal women, as well as to levels in women on systemic estrogen.

Hopefully, establishing the reference range can be done in an expeditious and timely way, with discussions with the FDA resuming shortly thereafter.

References

1.NAMS Citizen’s Petition and FDA Response, June 7, 2018. http://www.menopause.org/docs/

2. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA, et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. 2018;25:11-20.

3. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394:1159-1168.

4. Santen RJ, Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women, September 2019, Chicago, Illinois. Menopause. May 4, 2020. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001556.

5. Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, Santoro NF, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women: commentary from The North American Menopause Society on low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Menopause. 2020;27:611-613.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and The North American Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2014;79:349-354.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:859-876.

- Shifren JL. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:508-516.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The women’s EMPOWER survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 Hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA warns against the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal ‘rejuvenation’ or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-warns-against-use-energy-based-devices-perform-vaginal-rejuvenation-or-vaginal-cosmetic. Updated November 20, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Letters to industry. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/industry-medical-devices/letters-industry. July 24, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to the bothersome symptoms and physical findings associated with estrogen deficiency that involve the labia, vestibular tissue, clitoris, vagina, urethra, and bladder.1 GSM is associated with genital irritation, dryness, and burning; urinary symptoms including urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections; and sexual symptoms including vaginal dryness and pain. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) represents a component of GSM.

GSM is highly prevalent, affecting more than three-quarters of menopausal women. In contrast to menopausal vasomotor symptoms, which often are most severe and frequent in recently menopausal women, GSM commonly presents years following menopause. Unfortunately, VVA symptoms may have a substantial negative impact on women’s quality of life.

In this 2020 Menopause Update, I review a large observational study that provides reassurance to clinicians and patients regarding the safety of the best-studied prescription treatment for GSM—vaginal estrogen. Because some women should not use vaginal estrogen and others choose not to use it, nonhormonal management of GSM is important. Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton provides details on a randomized clinical trial that compared the use of fractionated CO2 laser therapy with vaginal estrogen for the treatment of GSM. In addition, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses recent studies that found lower health risks with vaginal estrogen use compared with systemic estrogen therapy.

Diagnosing GSM

GSM can be diagnosed presumptively based on a characteristic history in a menopausal patient. Performing a pelvic examination, however, allows clinicians to exclude other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, such as lichen sclerosus, Candida infection, and malignancy.

During inspection of the external genitalia, the clinician may note loss of the fat pad in the labia majora and mons as well as a reduction in labia minora pigmentation and tissue. The urethral meatus often becomes erythematous and prominent. If vaginal or introital narrowing is present, use of a pediatric (ultrathin) speculum reduces patient discomfort. The vaginal mucosa may appear smooth due to loss of rugation; it also may appear shiny and dry. Bleeding (friability) on contact with a spatula or cotton-tipped swab may occur. In addition, the vaginal fornices may become attenuated, leaving the cervix flush with the vaginal apex.

GSM can be diagnosed without laboratory assessment. However, vaginal pH, if measured, is characteristically higher than 5.0; microscopic wet prep often reveals many white blood cells, immature epithelial cells (large nuclei), and reduced or absent lactobacilli.2

Nonhormonal management of GSM

Water, silicone-based, and oil-based lubricants reduce the friction and discomfort associated with sexual activity. By contrast, vaginal moisturizers act longer than lubricants and can be applied several times weekly or daily. Natural oils, including olive and coconut oil, may be useful both as lubricants and as moisturizers. Aqueous lidocaine 4%, applied to vestibular tissue with cotton balls prior to penetration, reduces dyspareunia in women with GSM.3

Vaginal estrogen therapy

When nonhormonal management does not sufficiently reduce GSM symptoms, use of low-dose vaginal estrogen enhances thickness and elasticity of genital tissue and improves vaginal blood flow. Vaginal estrogen creams, tablets, an insert, and a ring are marketed in the United States. Although clinical improvement may be apparent within several weeks of initiating vaginal estrogen, the full benefit of treatment becomes apparent after 2 to 3 months.3

Despite the availability and effectiveness of low-dose vaginal estrogen, fears regarding the safety of menopausal hormone therapy have resulted in the underutilization of vaginal estrogen.4,5 Unfortunately, the package labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen can exacerbate these fears.

Continue to: Nurses’ Health Study report...

Nurses’ Health Study report provides reassurance on long-term safety of vaginal estrogen

Bhupathiraju SN, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. Vaginal estrogen use and chronic disease risk in the Nurses’ Health Study. Menopause. 2018;26:603-610

Bhupathiraju and colleagues published a report from the long-running Nurses’ Health prospective cohort study on the health outcomes associated with the use of vaginal estrogen.

Recap of the study

Starting in 1982, participants in the Nurses’Health Study were asked to report their use of vaginal estrogen via a validated questionnaire. For the years 1982 to 2012, investigators analyzed data from 896 and 52,901 women who had and had not used vaginal estrogen, respectively. The mean duration of vaginal estrogen use was 36 months.

In an analysis adjusted for numerous factors, the investigators observed no statistically significant differences in risk for cardiovascular outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism) or invasive cancers (colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, or breast).

Findings uphold safety of vaginal estrogen

This landmark study provides reassurance that 3 years of use of vaginal estrogen does not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer, findings that hopefully will allow clinicians and women to feel comfortable regarding the safety of vaginal estrogen. A study of vaginal estrogen from the Women’s Health Initiative provided similar reassurance. Recent research supports guidance from The North American Menopause Society and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal estrogen can be used indefinitely, if indicated, and that use of concomitant progestin is not recommended in women who use vaginal estrogen and have an intact uterus.6,7

I agree with the authors, who point out that since treatment of GSM may need to be continued long term (even indefinitely), it would be helpful to have data that assessed the safety of longer-duration use of vaginal estrogen.

Results from Bhupathiraju and colleagues’ analysis of data from the Nurses’ Health Study on the 3-year safety of vaginal estrogen use encourage clinicians to recommend and women to use this safe and effective treatment for GSM.

How CO2 fractionated vaginal laser therapy compares with vaginal estrogen for relief of GSM symptoms

Paraiso MF, Ferrando CA, Sokol ER, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the VeLVET trial. Menopause. 2020;27:50-56.

Up to 50% to 60% of postmenopausal women experience GSM symptoms. However, many fewer receive treatment, either because they do not understand that the symptoms are related to menopause or they are not aware that safe and effective treatment is available. Sadly, many women are not asked about their symptoms or are embarrassed to tell providers.

GSM affects relationships and quality of life. Vaginal lubricants or moisturizers may provide relief. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies include low-dose vaginal estrogen, available as a vaginal tablet, cream, suppository, and ring; intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA); and oral ospemifene, a selective estrogen replacement modulator. If women have an estrogen-sensitive breast or uterine cancer, an oncologist should be involved in decisions about vaginal hormonal therapy.

Energy-based devices such as vaginal lasers appear to induce wound healing; stimulate collagen and elastin fiber formation through increased storage of glycogen; and activate fibroblasts, which leads to increased extracellular matrix and restoration of vaginal pH.

These lasers are FDA approved for use in gynecology but not specifically for the treatment of GSM. In July 2016, the FDA issued a safety alert that energy-based devices, while approved for use in gynecology, have not been approved or adequately tested for menopausal vaginal conditions, and safety concerns include reports of vaginal burns.8 Lacking are publications of adequately powered randomized, sham-con-trolled trials to determine if laser therapy works better for women with GSM than placebos, moisturizers, or vaginal hormone therapies.

Recently, investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized, single-blinded trial of vaginal laser therapy and estrogen cream for treatment of GSM.

Continue to: Details of the study...

Details of the study

Paraiso and colleagues aimed to compare the 6-month efficacy and safety of fractionated CO2 vaginal laser therapy with that of estrogen vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal dryness/GSM.

Participants randomly assigned to the estrogen therapy arm applied conjugated estrogen cream 0.5 g vaginally daily for 14 days, followed by twice weekly application for 24 weeks (a low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy). Participants randomly assigned to laser therapy underwent 3 vaginal treatments at a minimum of 6 weeks apart.

Sixty-nine women were enrolled in the trial before enrollment was closed because the FDA required that the sponsor obtain and maintain an investigational device exemption. Of 62 women who completed 6 months’ treatment, 30 received 3 laser treatments and 32 received estrogen cream.

The primary outcome compared subjective improvement in vaginal dryness using the visual analog scale (VAS) between the 2 groups at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included comparisons of the vaginal health index (VHI) and vaginal maturation index (VMI), the effect of GSM on quality of life, the effect of treatment on sexual function and urinary symptoms, and patient satisfaction.

Study findings

Efficacy. Laser therapy and estrogen therapy were found to be similarly effective except on the VMI, which favored estrogen. On patient global impression, 85.8% of laser-treated women rated their improvement as ‘‘better or much better’’ and 78.5% reported being either ‘‘satisfied or very satisfied,’’ compared with 70% and 73.3%, respectively, in the estrogen group, a statistically nonsignificant difference.

On linear regression, the investigators found a nonsignificant mean difference in female sexual function index scores. While VMI scores remained higher in the estrogen-treated group (adjusted P = .02), baseline and 6-month follow-up VMI data were available for only 34 participants (16 laser treated, 18 estrogen treated).

Regarding long-term effectiveness, 20% to 25% of the women in the laser-treated group needed further treatment after 1 year while the estrogen cream continued to work as long as it was used as prescribed.

Adverse effects. The incidence of vaginal bleeding was similar in the 2 groups: 6.7% in the laser group and 6.3% in the estrogen group. In the laser therapy group, 3% expe-rienced vaginal pain, discharge, and bladder infections, while in the estrogen cream group, 3% reported breast tenderness, migraine headaches, and abdominal cramping.

Takeaways. This small randomized, open-label (not blinded) trial provides pilot data on the effectiveness of vaginal CO2 laser compared with vaginal estrogen in treating vaginal atrophy, quality-of-life symptoms, sexual function, and urinary symptoms. Adverse events were minimal. Patient global impression of improvement and satisfaction improved for both vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen therapy.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

To show noninferiority of vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen, 196 study participants were needed. However, after 38% had been enrolled, the FDA sent a warning letter to the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which required obtainment of an investigational device exemption for the laser and addition of a sham treatment arm.9 Instead of redesigning the trial and reconsenting the participants, the investigators closed the study, and analysis was performed only on the 62 participants who completed the study; vaginal maturation was assessed only in 34 participants.

The study lacked a placebo or sham control, which increases the risk of bias, while small numbers limit the strength of the findings. Longer-term evaluation of the effects of laser therapy beyond 6 months is needed to allow assessment of the effects of scarring on vaginal health, sexual function, and urinary issues.

Discussing therapy with patients

Despite this study’s preliminary findings, and until more robust data are available, providers should discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, FDA-approved vaginal hormone therapies (such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone), and systemic therapies, such as hormone therapy and ospemifene, to determine the best treatment for the individual woman with GSM.

In a healthy postmenopausal woman with bothersome GSM symptoms not responsive to lubricants and moisturizers, I recommend FDA-approved vaginal therapies as first-line treatment if there are no contraindications. For women with breast cancer, I involve their oncologist. If a patient asks about vaginal laser treatment, I share that vaginal energy-based therapies, such as the vaginal laser, have not been approved for menopausal vaginal concerns. In addition to the possibility of adverse events or unsuccessful treatment, there are significant out-of-pocket costs and the potential need for ongoing therapy after the initial 3 laser treatments.

For GSM that does not respond to lubricants and moisturizers, many FDA-approved vaginal and systemic therapies are available to treat vaginal symptoms. Vaginal laser treatment is a promising therapy for vaginal symptoms of GSM that needs further testing to determine its efficacy, safety, and long-term effects. If discussing vaginal energy-based therapies with patients, include the current lack of FDA approval for specific vaginal indications, potential adverse effects, the need for ongoing retreatment, and out-of-pocket costs.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

Having more appropriate, evidence-based labeling of low-dose vaginal estrogen continues to be a high priority for The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), and other professional societies.

NAMS and the Working Group on Women’s Health and Well-Being in Menopause had submitted a citizen’s petition to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 requesting modification of the label—including removal of the “black box warning”—for low-dose vaginal estrogen products. The petition was, disappointingly, denied in 2018.1

Currently, the class labeling, which was based on the results of randomized trials with systemic hormone therapy, is not applicable to low-dose vaginal estrogen, and the inclusion of the black box warning has led to serious underutilization of an effective and safe treatment for a very common and life-altering condition, the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). This condition affects nearly half of postmenopausal women. It tends to be chronic and progressive and, unlike hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it does not remit or decline over time, and it affects women’s health and quality of life.

While removal of the black box warning would be appropriate, labeling should include emphatic reminders for women that if they have any bleeding or spotting they should seek medical attention immediately, and if they have a history of breast cancer or other estrogen-sensitive cancers they should talk with their oncologist prior to starting treatment with low-dose vaginal estrogen. Although the text would still inform women of research results on systemic hormone therapy, it would explain the differences between low-dose vaginal estrogen and systemic therapy.

Studies show vaginal estrogen has good safety profile

In the last several years, large, observational studies of low-dose vaginal estrogen have suggested that this treatment is not associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, venous thrombosis, cancer, or dementia—conditions listed in the black box warning that were linked to systemic estrogen therapy plus synthetic progestin. Recent data from the Nurses’ Health Study, for example, demonstrated that 3 years of vaginal estrogen use did not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer.

Women’s Health Initiative. In a prospective observational cohort study, Crandall and colleagues used data from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study to determine the association between use of vaginal estrogen and risk of a global index event (GIE), defined as time to first occurrence of coronary heart disease, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, hip fracture, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, or death from any cause.2

Women were recruited from multiple clinical centers, were aged 50 to 79 years at baseline, and did not use systemic estrogen therapy during follow-up. The study included 45,663 women and median follow-up was 7.2 years. The investigators collected data on women’s self-reported use of vaginal estrogen as well as the development of the conditions defined above.

In women with a uterus, there was no significant difference between vaginal estrogen users and nonusers in the risk of stroke, invasive breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis. The risks of coronary heart disease, fracture, all-cause mortality, and GIE were lower in vaginal estrogen users than in nonusers (GIE adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55–0.86).

In women who had undergone hysterectomy, the risks of the individual GIE components and the overall GIE were not significantly different in users of vaginal estrogen compared with nonusers (GIE adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70–1.26).

The investigators concluded that the risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer were not increased in postmenopausal women who used vaginal estrogen. Thus, this study offers reassurance on the treatment’s safety.2

Meta-analysis on menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk. Further evidence now indicates that low-dose vaginal estrogen is not linked to chronic health conditions. In a large meta-analysis published in 2019, investigators looked at different types of hormone therapies—oral estrogen plus progestin, transdermal estrogen and progestin, estrogen alone, low-dose vaginal estrogen—and their relationship to breast cancer risk.3

Information on individual participants was obtained from 58 studies, 24 prospective and 34 retrospective. Breast cancer relative risks (RR) during years 5 to 14 of current hormone use were assessed according to the main hormonal contituents, doses, and modes of delivery of the last-used menopausal hormone therapy. For all systemic estrogen-only preparations, the RR was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.28–1.38), while for all estrogen-progestogen preparations, the RR was 2.08 (95% CI, 2.02–2.15). For transdermal estrogen, the RR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.25–1.46). In contrast, for vaginal estrogen, the RR was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97–1.23).3

Thus, the analysis found that in all the studies that had been done to date, there was no evidence of increased risk of breast cancer with vaginal estrogen therapy.

The evidence is growing that low-dose vaginal estrogen is different from systemic estrogen in terms of its safety profile and benefit-risk pattern. It is important for the FDA to consider these data and revise the vaginal estrogen label.

On the horizon: New estradiol reference ranges

It would be useful if we could accurately compare estradiol levels in women treated with vaginal estrogen against those of women treated with systemic estrogen therapy. In September 2019, NAMS held a workshop with the goal of establishing reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women.4 It is very important to have good, reliable laboratory assays for estradiol and estrone, and to have a clear understanding of what is a reference range, that is, the range of estradiol levels in postmenopausal women who are not treated with estrogen. That way, you can observe what the estradiol blood levels are in women treated with low-dose vaginal estrogen or those treated with systemic estrogen versus the levels observed among postmenopausal women not receiving any estrogen product.

With the reference range information, we could look at data on the blood levels of estradiol with low-dose vaginal estrogen from the various studies available, as well as the increasing evidence from observational studies of the safety of low-dose vaginal estrogen to better understand its relationship with health. If these studies demonstrate that, with certain doses and formulations of low-dose vaginal estrogen, blood estradiol levels stay within the reference range of postmenopausal estradiol levels, it would inform the labeling modifications of these products. We need this information for future discussions with the FDA.

The laboratory assay technology used for such an investigation is primarily liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry, the so-called LC-MS/MS assay. With use of this technology, the reference range for estradiol may be less than 10 picograms per milliliter. Previously, a very wide and inconsistent range—about 5 to 30 picograms per milliliter—was considered a “normal” range.

NAMS is championing the efforts to define a true evidence-based reference range that would represent the range of levels seen in postmenopausal women.5 This effort has been spearheaded by Dr. Richard Santen and colleagues. Using the more sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS assay will enable researchers and clinicians to better understand how levels on low-dose vaginal estrogen relate to the reference range for postmenopausal women. We are hoping to work together with researchers to establish these reference ranges, and to use that information to look at how low-dose vaginal estrogen compares to levels in untreated postmenopausal women, as well as to levels in women on systemic estrogen.

Hopefully, establishing the reference range can be done in an expeditious and timely way, with discussions with the FDA resuming shortly thereafter.

References

1.NAMS Citizen’s Petition and FDA Response, June 7, 2018. http://www.menopause.org/docs/

2. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA, et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. 2018;25:11-20.

3. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394:1159-1168.

4. Santen RJ, Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women, September 2019, Chicago, Illinois. Menopause. May 4, 2020. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001556.

5. Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, Santoro NF, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women: commentary from The North American Menopause Society on low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Menopause. 2020;27:611-613.

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to the bothersome symptoms and physical findings associated with estrogen deficiency that involve the labia, vestibular tissue, clitoris, vagina, urethra, and bladder.1 GSM is associated with genital irritation, dryness, and burning; urinary symptoms including urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections; and sexual symptoms including vaginal dryness and pain. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) represents a component of GSM.

GSM is highly prevalent, affecting more than three-quarters of menopausal women. In contrast to menopausal vasomotor symptoms, which often are most severe and frequent in recently menopausal women, GSM commonly presents years following menopause. Unfortunately, VVA symptoms may have a substantial negative impact on women’s quality of life.

In this 2020 Menopause Update, I review a large observational study that provides reassurance to clinicians and patients regarding the safety of the best-studied prescription treatment for GSM—vaginal estrogen. Because some women should not use vaginal estrogen and others choose not to use it, nonhormonal management of GSM is important. Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton provides details on a randomized clinical trial that compared the use of fractionated CO2 laser therapy with vaginal estrogen for the treatment of GSM. In addition, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses recent studies that found lower health risks with vaginal estrogen use compared with systemic estrogen therapy.

Diagnosing GSM

GSM can be diagnosed presumptively based on a characteristic history in a menopausal patient. Performing a pelvic examination, however, allows clinicians to exclude other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, such as lichen sclerosus, Candida infection, and malignancy.

During inspection of the external genitalia, the clinician may note loss of the fat pad in the labia majora and mons as well as a reduction in labia minora pigmentation and tissue. The urethral meatus often becomes erythematous and prominent. If vaginal or introital narrowing is present, use of a pediatric (ultrathin) speculum reduces patient discomfort. The vaginal mucosa may appear smooth due to loss of rugation; it also may appear shiny and dry. Bleeding (friability) on contact with a spatula or cotton-tipped swab may occur. In addition, the vaginal fornices may become attenuated, leaving the cervix flush with the vaginal apex.

GSM can be diagnosed without laboratory assessment. However, vaginal pH, if measured, is characteristically higher than 5.0; microscopic wet prep often reveals many white blood cells, immature epithelial cells (large nuclei), and reduced or absent lactobacilli.2

Nonhormonal management of GSM

Water, silicone-based, and oil-based lubricants reduce the friction and discomfort associated with sexual activity. By contrast, vaginal moisturizers act longer than lubricants and can be applied several times weekly or daily. Natural oils, including olive and coconut oil, may be useful both as lubricants and as moisturizers. Aqueous lidocaine 4%, applied to vestibular tissue with cotton balls prior to penetration, reduces dyspareunia in women with GSM.3

Vaginal estrogen therapy

When nonhormonal management does not sufficiently reduce GSM symptoms, use of low-dose vaginal estrogen enhances thickness and elasticity of genital tissue and improves vaginal blood flow. Vaginal estrogen creams, tablets, an insert, and a ring are marketed in the United States. Although clinical improvement may be apparent within several weeks of initiating vaginal estrogen, the full benefit of treatment becomes apparent after 2 to 3 months.3

Despite the availability and effectiveness of low-dose vaginal estrogen, fears regarding the safety of menopausal hormone therapy have resulted in the underutilization of vaginal estrogen.4,5 Unfortunately, the package labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen can exacerbate these fears.

Continue to: Nurses’ Health Study report...

Nurses’ Health Study report provides reassurance on long-term safety of vaginal estrogen

Bhupathiraju SN, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. Vaginal estrogen use and chronic disease risk in the Nurses’ Health Study. Menopause. 2018;26:603-610

Bhupathiraju and colleagues published a report from the long-running Nurses’ Health prospective cohort study on the health outcomes associated with the use of vaginal estrogen.

Recap of the study

Starting in 1982, participants in the Nurses’Health Study were asked to report their use of vaginal estrogen via a validated questionnaire. For the years 1982 to 2012, investigators analyzed data from 896 and 52,901 women who had and had not used vaginal estrogen, respectively. The mean duration of vaginal estrogen use was 36 months.

In an analysis adjusted for numerous factors, the investigators observed no statistically significant differences in risk for cardiovascular outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism) or invasive cancers (colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, or breast).

Findings uphold safety of vaginal estrogen

This landmark study provides reassurance that 3 years of use of vaginal estrogen does not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer, findings that hopefully will allow clinicians and women to feel comfortable regarding the safety of vaginal estrogen. A study of vaginal estrogen from the Women’s Health Initiative provided similar reassurance. Recent research supports guidance from The North American Menopause Society and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal estrogen can be used indefinitely, if indicated, and that use of concomitant progestin is not recommended in women who use vaginal estrogen and have an intact uterus.6,7

I agree with the authors, who point out that since treatment of GSM may need to be continued long term (even indefinitely), it would be helpful to have data that assessed the safety of longer-duration use of vaginal estrogen.

Results from Bhupathiraju and colleagues’ analysis of data from the Nurses’ Health Study on the 3-year safety of vaginal estrogen use encourage clinicians to recommend and women to use this safe and effective treatment for GSM.

How CO2 fractionated vaginal laser therapy compares with vaginal estrogen for relief of GSM symptoms

Paraiso MF, Ferrando CA, Sokol ER, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the VeLVET trial. Menopause. 2020;27:50-56.

Up to 50% to 60% of postmenopausal women experience GSM symptoms. However, many fewer receive treatment, either because they do not understand that the symptoms are related to menopause or they are not aware that safe and effective treatment is available. Sadly, many women are not asked about their symptoms or are embarrassed to tell providers.

GSM affects relationships and quality of life. Vaginal lubricants or moisturizers may provide relief. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies include low-dose vaginal estrogen, available as a vaginal tablet, cream, suppository, and ring; intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA); and oral ospemifene, a selective estrogen replacement modulator. If women have an estrogen-sensitive breast or uterine cancer, an oncologist should be involved in decisions about vaginal hormonal therapy.

Energy-based devices such as vaginal lasers appear to induce wound healing; stimulate collagen and elastin fiber formation through increased storage of glycogen; and activate fibroblasts, which leads to increased extracellular matrix and restoration of vaginal pH.

These lasers are FDA approved for use in gynecology but not specifically for the treatment of GSM. In July 2016, the FDA issued a safety alert that energy-based devices, while approved for use in gynecology, have not been approved or adequately tested for menopausal vaginal conditions, and safety concerns include reports of vaginal burns.8 Lacking are publications of adequately powered randomized, sham-con-trolled trials to determine if laser therapy works better for women with GSM than placebos, moisturizers, or vaginal hormone therapies.

Recently, investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized, single-blinded trial of vaginal laser therapy and estrogen cream for treatment of GSM.

Continue to: Details of the study...

Details of the study

Paraiso and colleagues aimed to compare the 6-month efficacy and safety of fractionated CO2 vaginal laser therapy with that of estrogen vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal dryness/GSM.

Participants randomly assigned to the estrogen therapy arm applied conjugated estrogen cream 0.5 g vaginally daily for 14 days, followed by twice weekly application for 24 weeks (a low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy). Participants randomly assigned to laser therapy underwent 3 vaginal treatments at a minimum of 6 weeks apart.

Sixty-nine women were enrolled in the trial before enrollment was closed because the FDA required that the sponsor obtain and maintain an investigational device exemption. Of 62 women who completed 6 months’ treatment, 30 received 3 laser treatments and 32 received estrogen cream.

The primary outcome compared subjective improvement in vaginal dryness using the visual analog scale (VAS) between the 2 groups at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included comparisons of the vaginal health index (VHI) and vaginal maturation index (VMI), the effect of GSM on quality of life, the effect of treatment on sexual function and urinary symptoms, and patient satisfaction.

Study findings

Efficacy. Laser therapy and estrogen therapy were found to be similarly effective except on the VMI, which favored estrogen. On patient global impression, 85.8% of laser-treated women rated their improvement as ‘‘better or much better’’ and 78.5% reported being either ‘‘satisfied or very satisfied,’’ compared with 70% and 73.3%, respectively, in the estrogen group, a statistically nonsignificant difference.

On linear regression, the investigators found a nonsignificant mean difference in female sexual function index scores. While VMI scores remained higher in the estrogen-treated group (adjusted P = .02), baseline and 6-month follow-up VMI data were available for only 34 participants (16 laser treated, 18 estrogen treated).

Regarding long-term effectiveness, 20% to 25% of the women in the laser-treated group needed further treatment after 1 year while the estrogen cream continued to work as long as it was used as prescribed.

Adverse effects. The incidence of vaginal bleeding was similar in the 2 groups: 6.7% in the laser group and 6.3% in the estrogen group. In the laser therapy group, 3% expe-rienced vaginal pain, discharge, and bladder infections, while in the estrogen cream group, 3% reported breast tenderness, migraine headaches, and abdominal cramping.

Takeaways. This small randomized, open-label (not blinded) trial provides pilot data on the effectiveness of vaginal CO2 laser compared with vaginal estrogen in treating vaginal atrophy, quality-of-life symptoms, sexual function, and urinary symptoms. Adverse events were minimal. Patient global impression of improvement and satisfaction improved for both vaginal laser and vaginal estrogen therapy.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

To show noninferiority of vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen, 196 study participants were needed. However, after 38% had been enrolled, the FDA sent a warning letter to the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which required obtainment of an investigational device exemption for the laser and addition of a sham treatment arm.9 Instead of redesigning the trial and reconsenting the participants, the investigators closed the study, and analysis was performed only on the 62 participants who completed the study; vaginal maturation was assessed only in 34 participants.

The study lacked a placebo or sham control, which increases the risk of bias, while small numbers limit the strength of the findings. Longer-term evaluation of the effects of laser therapy beyond 6 months is needed to allow assessment of the effects of scarring on vaginal health, sexual function, and urinary issues.

Discussing therapy with patients

Despite this study’s preliminary findings, and until more robust data are available, providers should discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, FDA-approved vaginal hormone therapies (such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone), and systemic therapies, such as hormone therapy and ospemifene, to determine the best treatment for the individual woman with GSM.

In a healthy postmenopausal woman with bothersome GSM symptoms not responsive to lubricants and moisturizers, I recommend FDA-approved vaginal therapies as first-line treatment if there are no contraindications. For women with breast cancer, I involve their oncologist. If a patient asks about vaginal laser treatment, I share that vaginal energy-based therapies, such as the vaginal laser, have not been approved for menopausal vaginal concerns. In addition to the possibility of adverse events or unsuccessful treatment, there are significant out-of-pocket costs and the potential need for ongoing therapy after the initial 3 laser treatments.

For GSM that does not respond to lubricants and moisturizers, many FDA-approved vaginal and systemic therapies are available to treat vaginal symptoms. Vaginal laser treatment is a promising therapy for vaginal symptoms of GSM that needs further testing to determine its efficacy, safety, and long-term effects. If discussing vaginal energy-based therapies with patients, include the current lack of FDA approval for specific vaginal indications, potential adverse effects, the need for ongoing retreatment, and out-of-pocket costs.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

Having more appropriate, evidence-based labeling of low-dose vaginal estrogen continues to be a high priority for The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), and other professional societies.

NAMS and the Working Group on Women’s Health and Well-Being in Menopause had submitted a citizen’s petition to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 requesting modification of the label—including removal of the “black box warning”—for low-dose vaginal estrogen products. The petition was, disappointingly, denied in 2018.1

Currently, the class labeling, which was based on the results of randomized trials with systemic hormone therapy, is not applicable to low-dose vaginal estrogen, and the inclusion of the black box warning has led to serious underutilization of an effective and safe treatment for a very common and life-altering condition, the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). This condition affects nearly half of postmenopausal women. It tends to be chronic and progressive and, unlike hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it does not remit or decline over time, and it affects women’s health and quality of life.

While removal of the black box warning would be appropriate, labeling should include emphatic reminders for women that if they have any bleeding or spotting they should seek medical attention immediately, and if they have a history of breast cancer or other estrogen-sensitive cancers they should talk with their oncologist prior to starting treatment with low-dose vaginal estrogen. Although the text would still inform women of research results on systemic hormone therapy, it would explain the differences between low-dose vaginal estrogen and systemic therapy.

Studies show vaginal estrogen has good safety profile

In the last several years, large, observational studies of low-dose vaginal estrogen have suggested that this treatment is not associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, venous thrombosis, cancer, or dementia—conditions listed in the black box warning that were linked to systemic estrogen therapy plus synthetic progestin. Recent data from the Nurses’ Health Study, for example, demonstrated that 3 years of vaginal estrogen use did not increase the risk of cardiovascular events or invasive breast cancer.

Women’s Health Initiative. In a prospective observational cohort study, Crandall and colleagues used data from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study to determine the association between use of vaginal estrogen and risk of a global index event (GIE), defined as time to first occurrence of coronary heart disease, invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, hip fracture, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, or death from any cause.2

Women were recruited from multiple clinical centers, were aged 50 to 79 years at baseline, and did not use systemic estrogen therapy during follow-up. The study included 45,663 women and median follow-up was 7.2 years. The investigators collected data on women’s self-reported use of vaginal estrogen as well as the development of the conditions defined above.

In women with a uterus, there was no significant difference between vaginal estrogen users and nonusers in the risk of stroke, invasive breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis. The risks of coronary heart disease, fracture, all-cause mortality, and GIE were lower in vaginal estrogen users than in nonusers (GIE adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55–0.86).

In women who had undergone hysterectomy, the risks of the individual GIE components and the overall GIE were not significantly different in users of vaginal estrogen compared with nonusers (GIE adjusted HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70–1.26).

The investigators concluded that the risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer were not increased in postmenopausal women who used vaginal estrogen. Thus, this study offers reassurance on the treatment’s safety.2

Meta-analysis on menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk. Further evidence now indicates that low-dose vaginal estrogen is not linked to chronic health conditions. In a large meta-analysis published in 2019, investigators looked at different types of hormone therapies—oral estrogen plus progestin, transdermal estrogen and progestin, estrogen alone, low-dose vaginal estrogen—and their relationship to breast cancer risk.3

Information on individual participants was obtained from 58 studies, 24 prospective and 34 retrospective. Breast cancer relative risks (RR) during years 5 to 14 of current hormone use were assessed according to the main hormonal contituents, doses, and modes of delivery of the last-used menopausal hormone therapy. For all systemic estrogen-only preparations, the RR was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.28–1.38), while for all estrogen-progestogen preparations, the RR was 2.08 (95% CI, 2.02–2.15). For transdermal estrogen, the RR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.25–1.46). In contrast, for vaginal estrogen, the RR was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97–1.23).3

Thus, the analysis found that in all the studies that had been done to date, there was no evidence of increased risk of breast cancer with vaginal estrogen therapy.

The evidence is growing that low-dose vaginal estrogen is different from systemic estrogen in terms of its safety profile and benefit-risk pattern. It is important for the FDA to consider these data and revise the vaginal estrogen label.

On the horizon: New estradiol reference ranges

It would be useful if we could accurately compare estradiol levels in women treated with vaginal estrogen against those of women treated with systemic estrogen therapy. In September 2019, NAMS held a workshop with the goal of establishing reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women.4 It is very important to have good, reliable laboratory assays for estradiol and estrone, and to have a clear understanding of what is a reference range, that is, the range of estradiol levels in postmenopausal women who are not treated with estrogen. That way, you can observe what the estradiol blood levels are in women treated with low-dose vaginal estrogen or those treated with systemic estrogen versus the levels observed among postmenopausal women not receiving any estrogen product.

With the reference range information, we could look at data on the blood levels of estradiol with low-dose vaginal estrogen from the various studies available, as well as the increasing evidence from observational studies of the safety of low-dose vaginal estrogen to better understand its relationship with health. If these studies demonstrate that, with certain doses and formulations of low-dose vaginal estrogen, blood estradiol levels stay within the reference range of postmenopausal estradiol levels, it would inform the labeling modifications of these products. We need this information for future discussions with the FDA.

The laboratory assay technology used for such an investigation is primarily liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry, the so-called LC-MS/MS assay. With use of this technology, the reference range for estradiol may be less than 10 picograms per milliliter. Previously, a very wide and inconsistent range—about 5 to 30 picograms per milliliter—was considered a “normal” range.

NAMS is championing the efforts to define a true evidence-based reference range that would represent the range of levels seen in postmenopausal women.5 This effort has been spearheaded by Dr. Richard Santen and colleagues. Using the more sensitive and specific LC-MS/MS assay will enable researchers and clinicians to better understand how levels on low-dose vaginal estrogen relate to the reference range for postmenopausal women. We are hoping to work together with researchers to establish these reference ranges, and to use that information to look at how low-dose vaginal estrogen compares to levels in untreated postmenopausal women, as well as to levels in women on systemic estrogen.

Hopefully, establishing the reference range can be done in an expeditious and timely way, with discussions with the FDA resuming shortly thereafter.

References

1.NAMS Citizen’s Petition and FDA Response, June 7, 2018. http://www.menopause.org/docs/

2. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA, et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. 2018;25:11-20.

3. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394:1159-1168.

4. Santen RJ, Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women, September 2019, Chicago, Illinois. Menopause. May 4, 2020. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001556.

5. Pinkerton JV, Liu JH, Santoro NF, et al. Workshop on normal reference ranges for estradiol in postmenopausal women: commentary from The North American Menopause Society on low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Menopause. 2020;27:611-613.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and The North American Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2014;79:349-354.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:859-876.

- Shifren JL. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:508-516.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The women’s EMPOWER survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 Hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA warns against the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal ‘rejuvenation’ or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-warns-against-use-energy-based-devices-perform-vaginal-rejuvenation-or-vaginal-cosmetic. Updated November 20, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Letters to industry. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/industry-medical-devices/letters-industry. July 24, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and The North American Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2014;79:349-354.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:859-876.

- Shifren JL. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:508-516.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The women’s EMPOWER survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 Hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA warns against the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal ‘rejuvenation’ or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-warns-against-use-energy-based-devices-perform-vaginal-rejuvenation-or-vaginal-cosmetic. Updated November 20, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. Letters to industry. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/industry-medical-devices/letters-industry. July 24, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2020

Does BSO status affect health outcomes for women taking estrogen for menopause?

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?

Dr. Manson: The WHI is the first study to be conducted in a randomized trial setting to analyze the health risks and benefits of estrogen therapy according to whether or not women had their ovaries removed. What we found was that the woman’s age had a strong influence on the effects of estrogen therapy among women who had BSO but only a negligible effect among women who had conserved ovaries. Overall, across the full age range, the effects of estrogen therapy did not differ substantially between women who had a BSO and those who had their ovaries conserved.

However, there were major differences by age group among the women who had BSO. A significant 32% reduction in all-cause mortality emerged during the 18-year follow-up period among the younger women (below age 60) who had BSO when they received estrogen therapy as compared with placebo. By contrast, the women who had conserved ovaries did not have this significant reduction in all-cause mortality, or in most of the other outcomes on estrogen compared with placebo. Overall, the effects of estrogen therapy tended to be relatively neutral in the women with conserved ovaries.