User login

Goodbye, finger sticks; hello, CGMs

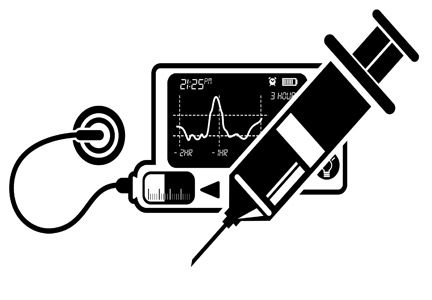

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gestational diabetes: Optimizing Dx and management in primary care

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as new-onset hyperglycemia detected in a pregnant woman after 24 weeks of gestation, affects 4% to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually1 and is a major challenge for health care professionals.2 During pregnancy, the body’s physiologic responses are altered to support the growing fetus. One of these changes is an increase in insulin resistance, which suggests that pregnancy alone increases the patient’s risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, several other factors also increase this risk, including maternal age, social barriers to care, obesity, poor weight control, and family history.

If not controlled, GDM results in poor health outcomes for the mother, such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and maternal T2D.3-5 For the infant, intrauterine exposure to persistent hyperglycemia is correlated with neonatal macrosomia, hypoglycemia, perinatal complications (eg, preterm delivery, fetal demise), and obesity and insulin resistance later in life.4

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are the patient’s main point of contact prior to pregnancy. This relationship makes PCPs a resource for the patient and specialists during and after pregnancy. In this article, we discuss risk factors and how to screen for GDM, provide an update on practice recommendations for treatment and management of GDM in primary care, and describe the effects of uncontrolled GDM.

Know the key risk factors

Prevention begins with identifying the major risk factors that contribute to the development of GDM. These include maternal age, social barriers to care, family history of prediabetes, and obesity and poor weight control.

Older age. A meta-analysis of 24 studies noted strong positive correlation between GDM risk and maternal age.6 One of the population-based cohort studies in the meta-analysis examined relationships between maternal age and pregnancy outcomes in women living in British Columbia, Canada (n = 203,414). Data suggested that the relative risk of GDM increased linearly with maternal age to 3.2, 4.2, and 4.4 among women ages ≥ 35, ≥ 40, and ≥ 45 years, respectively.7

Social barriers to care. Although the prevalence of GDM has increased over the past few decades,1 from 2011 to 2019 the increase in GDM in individuals at first live birth was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic/Latina women than in non-Hispanic White women.8 Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention further suggest that diabetes was more prevalent among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status as indicated by their level of education.9 Ogunwole et al10 suggest that racism is the root cause of these disparities and leads to long-term barriers to care (eg, socioeconomic deprivation, lack of health insurance, limited access to care, and poor health literacy), which ultimately contribute to the development of GDM and progression of diabetes. It is important for PCPs and all health professionals to be aware of these barriers so that they may practice mindfulness and deliver culturally sensitive care to patients from marginalized communities.

Family history of prediabetes. In a population-based cohort study (n = 7020), women with prediabetes (A1C, 5.7%-6.4%) were 2.8 times more likely to develop GDM compared with women with normal A1C (< 5.7%).11 Similar results were seen in a retrospective cohort study (n = 2812), in which women with prediabetes were more likely than women with a normal first trimester A1C to have GDM (29.1% vs 13.7%, respectively; adjusted relative risk = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15-1.89).12 In both studies, prediabetes was not associated with a higher risk for adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes.11,12

Continue to: While there are no current...

While there are no current guidelines for treating prediabetes in pregnancy, women diagnosed with prediabetes in 1 study were found to have significantly less weight gain during pregnancy compared with patients with normal A1C,12 suggesting there may be a benefit in early identification and intervention, although further research is needed.11 In a separate case-control study (n = 345 women with GDM; n = 800 control), high rates of gestational weight gain (> 0.41 kg/wk) were associated with an increased risk of GDM (odds ratio [OR] = 1.74; 95% CI, 1.16-2.60) compared with women with the lowest rate of gestational weight gain (0.27-0.4 kg/wk [OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 0.96-2.14]).13 Thus, it is helpful to have proactive conversations about family planning and adequate weight and glycemic control with high-risk patients to prepare for a healthy pregnancy.

Obesity and weight management. Patients who are overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI > 30) have a substantially increased risk of GDM (adjusted OR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.04-1.81), as seen in a retrospective cohort study of 1951 pregnant Malaysian women.14 Several factors have been found to contribute to successful weight control, including calorie prescription, a structured meal plan, high physical activity goals (60-90 min/d), daily weighing and monitoring of food intake, behavior therapy, and continued patient–provider contact.15

The safety, efficacy, and sustainability of weight loss with various dietary plans have been studied in individuals who are overweight and obese.16 Ultimately, energy expenditure must be greater than energy intake to promote weight loss. Conventional diets with continuous energy restriction (ie, low-fat, low-carbohydrate, and high-protein diets) have proven to be effective for short-term weight loss but data on long-term weight maintenance are limited.16 The Mediterranean diet, which is comprised mostly of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and grains—with a lower intake of meat and dairy—may reduce gestational weight gain and risk of GDM as suggested by a randomized controlled trial (RCT; n = 1252).17 Although the choice of diet is up to the patient, it is important to be aware of different diets or refer the patient to a registered dietician who can help the patient if needed.

Reduce risk with adequate weight and glycemic control

Prevention of GDM during pregnancy should focus on weight maintenance and optimal glycemic control. Two systematic reviews, one with 8 RCTs (n = 1792) and another with 5 studies (n = 539), assessed the efficacy and safety of energy-restricted dietary intervention on GDM prevention.18 The first review found a significant reduction in gestational weight gain and improved glycemic control without increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.18 The second review showed no clear difference between energy-restricted and non–energy-restricted diets on outcomes such as preeclampsia, gestational weight gain, large for gestational age, and macrosomia.18 These data suggest that while energy-restricted dietary interventions made no difference on maternal and fetal complications, they may still be safely used in pregnancy to reduce gestational weight gain and improve glycemic control.18

Once a woman is pregnant, it becomes difficult to lose weight because additional calories are needed to support a growing fetus. It is recommended that patients with healthy pregestational BMI consume an extra 200 to 300 calories/d after the first trimester. However, extra caloric intake in a woman with obesity who is pregnant leads to metabolic impairment and increased risk of diabetes for both the mother and fetus.19 Therefore, it is recommended that patients with obese pregestational BMI not consume additional calories because excess maternal fat is sufficient to support the energy needs of the growing fetus.19

Continue to: Ultimately, earlier intervention...

Ultimately, earlier intervention—prior to conception—helps patients prepare for a healthier pregnancy, resulting in better long-term outcomes. It is helpful to be familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of common approaches to weight management and to be able to refer patients to nutritionists for optimal planning. When establishing a dietary plan, consider patient-specific factors, such as cultural diets, financial and time constraints, and the patient’s readiness to make and maintain these changes. Consistent follow-up and behavioral therapy are necessary to maintain successful weight control.

There are many screening tools, but 1 is preferred in pregnancy

There are several ways to diagnose diabetes in patients who are not pregnant, including A1C, a fasting glucose test, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or random glucose testing (plus symptoms). However, the preferred method for diagnosing GDM is OGTT because it has a higher sensitivity.20 A1C, while a good measure of hyperglycemic stability, does not register hyperglycemia early enough to diagnose GDM and fasting glucose testing is less sensitive because for most women with GDM, that abnormal postprandial glucose level is the first glycemic abnormality.21

When to screen. Blood glucose levels should be checked in all pregnant women as part of their metabolic panel at the first prenatal visit. A reflex A1C for high glucose levels can be ordered based on the physician’s preference. This may help you to identify patients with prediabetes who are at risk for GDM and implement early behavioral and lifestyle changes. However, further research is needed to determine if intervention early in pregnancy can truly reduce the risk of GDM.11

Screening for GDM should be completed at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation20 because it is likely that this is when the hormonal effects of the placenta that contribute to insulin resistance set the woman up for postprandial hyperglycemia. Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the use of continuous glucose monitoring prior to 24 weeks of gestation to identify GDM.20 If persistent hyperglycemia is present before 24 weeks of gestation, it is considered evidence of a pre-existing metabolic abnormality and is diagnosed as “pregestational diabetes.” Treatment should follow guidelines established for women who had diabetes prior to pregnancy.

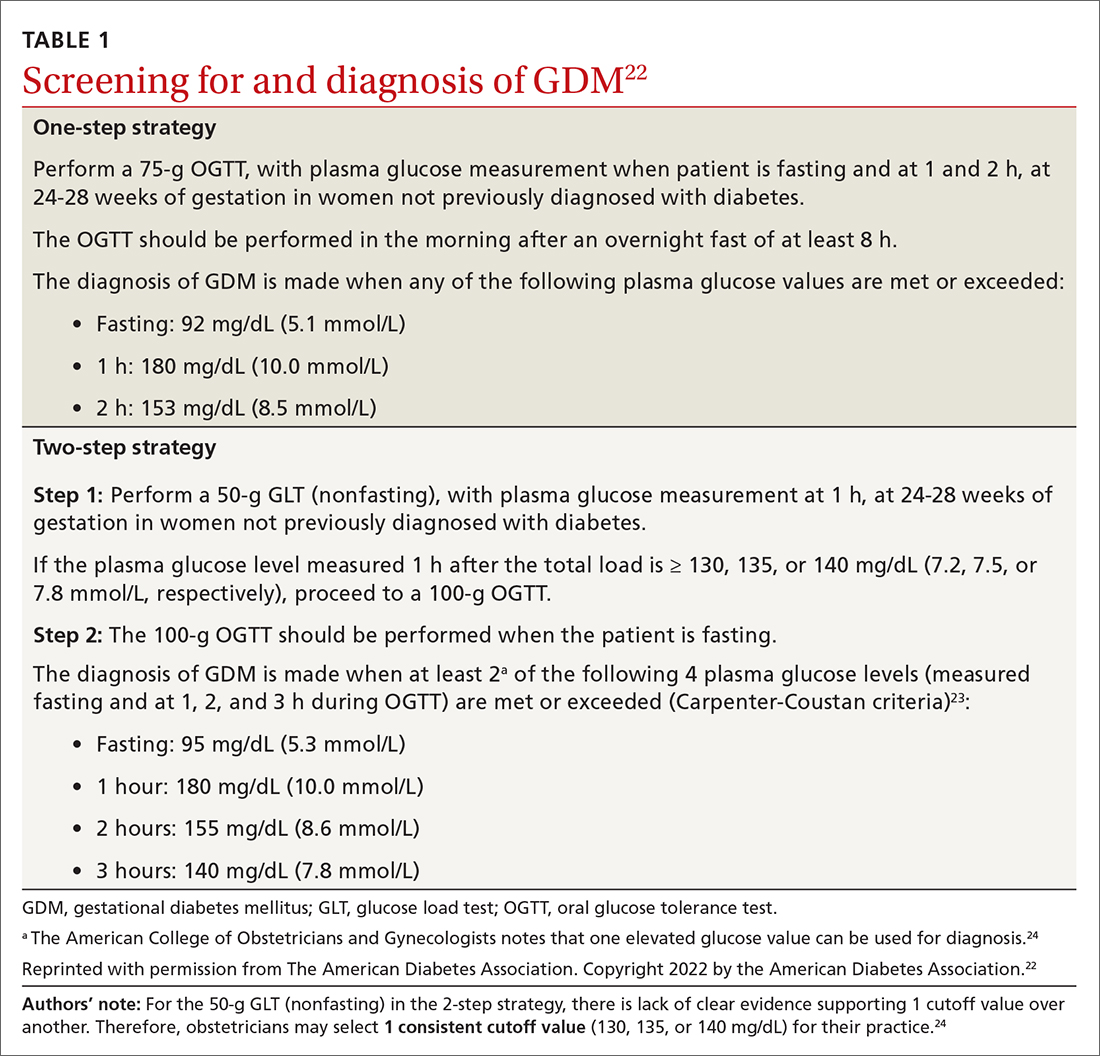

How to screen? There is ongoing discussion about what is the optimal screening method for GDM: a 1-step strategy with a fasting 75-g OGTT only, or a 2-step strategy with a 50-g non-fasting glucose load test followed by a fasting 100-g OGTT in women who do not meet the plasma glucose cutoff (TABLE 1).22-24 Hillier et al25 compared the effectiveness of these strategies in diagnosing GDM and identifying pregnancy complications for the mother and infant. They found that while the 1-step strategy resulted in a 2-fold increase in the diagnosis of GDM, it did not lead to better outcomes for mothers and infants when compared with the 2-step method.25 Currently, the majority of obstetricians (95%) prefer to use the 2-step method.24

Continue to: Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Management of GDM in most women starts with diabetes self-management education and support for therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as nutritional interventions that reduce hyperglycemia and contribute to healthy weight gain during pregnancy.20 This may include medical nutrition therapy that focuses on adequate nutrition for the mother and fetus. Currently, the recommended dietary intake for women who are pregnant (regardless of diabetes) includes a minimum of 175 g of carbohydrates, 71 g of daily protein, and at least 28 g of fiber. Further refinement of dietary intake, including carbohydrate restriction, should be done with guidance from a registered dietitian.20 If the obstetrics team does not include a registered dietitian, a referral to one may be necessary. Regular physical activity should be continued throughout pregnancy as tolerated. Social support, stress reduction, and good sleep hygiene should be encouraged as much as possible.

For successful outcomes, therapeutic lifestyle changes should be coupled with glucose monitoring. The Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus recommends that women with GDM monitor fasting blood glucose and typically 1-hour postprandial glucose. The glucose goals in GDM are as follows26:

- Fasting glucose < 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L), and either

- 1-hour postprandial glucose < 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L), or

- 2-hour postprandial glucose < 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L).

Importantly, in the second and third trimester, the A1C goal for women with GDM is 6.0%. This is lower than the more traditional A1C goal for 2 reasons: (1) increases in A1C, even within the normal range, increase adverse outcomes; and (2) pregnant women will have an increased red blood cell count turnover, which can lower the A1C.27 In a historical cohort study (n = 27,213), Abell et al28 found that women who have an A1C < 6.0% in the second and third trimester have the lowest risk of giving birth to large-for-gestational-age infants and for having preeclampsia.

Add insulin if glucose targets are not met

Most women who engage in therapeutic lifestyle change (70%-85%) can achieve an A1C < 6% and will not need to take medication to manage GDM.29 If pharmacotherapy is needed to manage glucose, insulin is the preferred treatment for all women with GDM.20 Treatment should be individualized based on the glucose trends the woman is experiencing. Common treatments include bedtime NPH if fasting hyperglycemia is most prominent and analogue insulin at mealtimes for women with prominent postprandial hyperglycemia.

Noninsulin agents such as metformin and sulfonylureas are not currently recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the American Diabetes Association for use in GDM.20,24 Despite being used for years in women with pregestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome, there is evidence that metformin crosses the placenta and fetal safety has not yet been established in RCTs. The Metformin in Gestational Diabetes: The Offspring Follow-Up (MiG TOFU) study was a longitudinal follow-up study that evaluated body composition and metabolic outcomes in children (ages 7-9 years) of women with GDM who had received metformin or insulin while pregnant.30 At age 9 years, children who were exposed to metformin weighed more and had a higher waist-to-height ratio and waist circumference than those exposed to insulin.30

Continue to: Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended...

Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended because of the risk of maternal and fetal hypoglycemia and concerns about this medication crossing the placenta.24,31,32 Specifically, in a 2015 meta-analysis and systematic review of 15 articles (n = 2509), glyburide had a higher risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and macrosomia than insulin or metformin.33 For women who cannot manage their glucose with therapeutic lifestyle changes and cannot take insulin, oral therapies may be considered if the risk-benefit ratio is balanced for that person.34

Watch for effects of poor glycemic control on mother, infant

Preeclampsia is defined as new-onset hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. The correlation between GDM and preeclampsia has partly been explained by their shared overlapping risk factors, including maternal obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and persistent hyperglycemia.35 On a biochemical level, these risk factors contribute to oxidative stress and systemic vascular dysfunction, which have been hypothesized as the underlying pathophysiology for the development of preeclampsia.35

Neonatal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight ≥ 4000 g, is a common complication that develops in 15% to 45% of infants of mothers with GDM.36 Placental transfer of glucose in mothers with hyperglycemia stimulates the secretion of neonatal insulin and the ultimate storage of the excess glucose as body fat. After delivery, the abrupt discontinuation of placental transfer of glucose to an infant who is actively secreting insulin leads to neonatal hypoglycemia, which if not detected or managed, can lead to long-term neurologic deficits, including recurrent seizures and developmental delays.37 Therefore, it is essential to screen for neonatal hypoglycemia immediately after birth and serially up to 12 hours.38

Postpartum T2D. Poor glycemic control increases the risk of increasing insulin resistance developing into T2D postpartum for mothers.39 It also increases the risk of obesity and insulin resistance later in life for the infant.40 A retrospective cohort study (n = 461) found a positive correlation between exposure to maternal GDM and elevated BMI in children ages 6 to 13 years.41 Kamana et al36 further discussed this correlation and suggested that exposure to maternal hyperglycemia in utero contributes to fetal programming of later adipose deposition. Children may develop without a notable increase in BMI until after puberty.42

Partner with specialists to improve outcomes

Although most women with GDM are managed by specialists (obstetricians, endocrinologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists),43 these patients are still seeking care from their family physicians for other complaints. These visits provide key touchpoints during pregnancy and are opportunities for PCPs to identify a pregnancy-related complication or provide additional education or referral to the obstetrician.

Continue to: Also, if you work in an area...

Also, if you work in an area where specialists are less accessible, you may be the clinician providing the majority of care to a patient with GDM. If this is the case, you’ll want to watch for the following risk factors, which should prompt a referral to specialty care:

- a previous pregnancy with GDM20

- a previous birth of an infant weighing > 4000 g44

- baseline history of hypertension45

- evidence of insulin resistance or polycystic ovary syndrome46,47

- a history of cardiovascular disease20

- a need to treat GDM with pharmacotherapy.48

Ensuring a smooth transition after the birth

Optimal communication and hand-offs throughout pregnancy and after delivery will benefit everyone. When the pregnant patient’s care has been managed by an obstetrician, it is important to address the following issues during the hand-off:

- baseline medical problems

- medical screenings and treatments in pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy screening)

- aspirin initiation, if indicated

- management of thyroid abnormalities

- management of mental health conditions

- postpartum glucose management and T2D screening postpartum

- management of complications identified during pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy).

Timing and other elements of postpartum care. The first postpartum screen should occur at 4 to 12 weeks postpartum. OGTT is recommended instead of A1C at this time because A1C may still be lowered by the increased red blood cell turnover related to pregnancy and blood loss at delivery. Because women with GDM have a 50% to 75% lifetime risk of T2D,20 patients with normal test results should be re-tested every 1 to 3 years using any of the standard screening methods (A1C, fasting glucose, or OGTT).20

After delivery it may be difficult for women to follow-up with their own personal health care because they are focused on the care of their baby. The increased use of telehealth may make postpartum follow-up visits easier to attend.

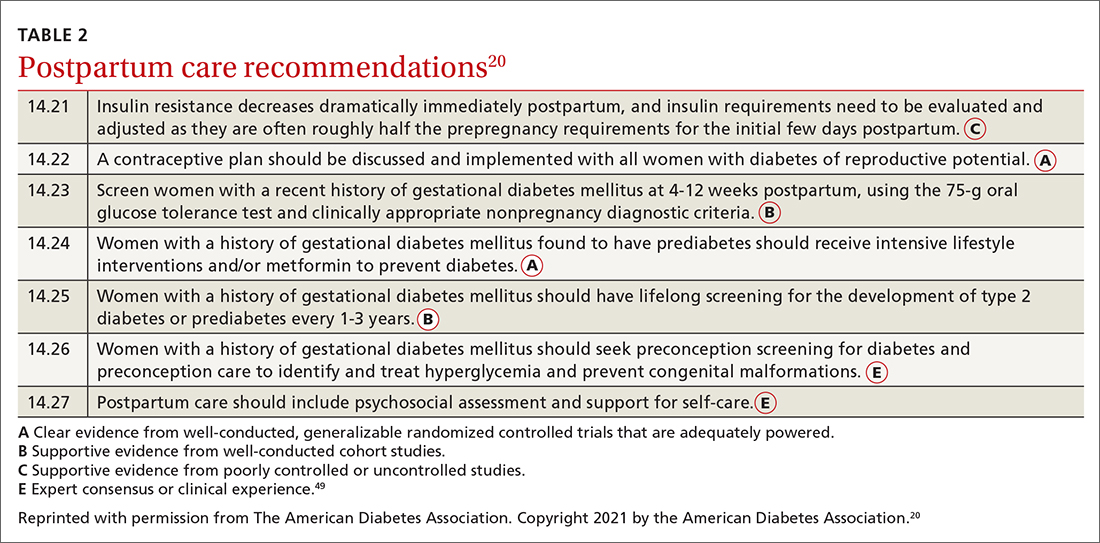

Visits present opportunities. Postpartum visits present another opportunity for PCPs to screen for diabetes and other postpartum complications, including depression and thyroid abnormalities. Visits are also an opportunity to discuss timely contraception so as to prevent an early, unplanned pregnancy. Other important aspects of postpartum care are outlined in TABLE 2.20,49

CORRESPONDENCE

Connie L. Ha, BS, OMS IV, Department of Primary Care, 1310 Club Drive, Touro University California, Vallejo, CA 94592; connie.ha@tu.edu

1. Sheiner E. Gestational diabetes mellitus: long-term consequences for the mother and child grand challenge: how to move on towards secondary prevention? Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2020. doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2020.546256

2. Angueira AR, Ludvik AE, Reddy TE, et al. New insights into gestational glucose metabolism: lessons learned from 21st century approaches. Diabetes. 2015;64:327-334. doi: 10.2337/db14-0877

3. Shou C, Wei Y-M, Wang C, et al. Updates in long-term maternal and fetal adverse effects of gestational diabetes mellitus. Maternal-Fetal Med. 2019;1:91-94. doi: 10.1097/FM9.0000000000000019

4. Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3342. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113342

5. Kulshrestha V, Agarwal N. Maternal complications in pregnancy with diabetes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(9 suppl 1):S74-S77.

6. Li Y, Ren X, He L, et al. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108044. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108044

7. Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Hacker MR, et al. Absolute risks of obstetric outcomes by maternal age at first birth: a population-based cohort. Epidemiology. 2018;29:379-387. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000818

8. Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326:660-669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7217

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed February 2, 2022. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

10. Ogunwole SM, Golden SH. Social determinants of health and structural inequities—root causes of diabetes disparities. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:11-13. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0060

11. Chen L, Pocobelli G, Yu O, et al. Early pregnancy hemoglobin A1C and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36:1045-1053. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675619

12. Osmundson S, Zhao BS, Kunz L, et al. First trimester hemoglobin A1C prediction of gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:977-982. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581055

13. Hedderson MM, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1092]. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:597-604. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cfce4f

14. Yong HY, Mohd Shariff Z, Mohd Yusof BN, et al. Independent and combined effects of age, body mass index and gestational weight gain on the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 2020;10:8486. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65251-2

15. Phelan S. Windows of opportunity for lifestyle interventions to prevent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:1291-1299. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586504

16. Koliaki C, Spinos T, Spinou M, et al. Defining the optimal dietary approach for safe, effective and sustainable weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6:73. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6030073

17. Al Wattar BH, Dodds J, Placzek A, et al. Mediterranean-style diet in pregnant women with metabolic risk factors (ESTEEM): a pragmatic multicentre randomised trial. PLOS Med. 2019;16:e1002857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002857

18. Zarogiannis S. Are novel lifestyle approaches to management of type 2 diabetes applicable to prevention and treatment of women with gestational diabetes mellitus? Global Diabetes Open Access J. 2019;1:1-14.

19. Most J, Amant MS, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690. doi: 10.1172/JCI130341

20. American Diabetes Association. 14. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S200-S210. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S014

21. McIntyre HD, Sacks DA, Barbour LA, et al. Issues with the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in early pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:53-54. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1887

22. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(suppl 1):S17-S38. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S002

23. Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768-773. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90349-0

24. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e49-e64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501

25. Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Ogasawara KK, et al. A pragmatic, randomized clinical trial of gestational diabetes screening. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:895-904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026028

26. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225

27. Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1200-1201. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1200

28. Abell SK, Boyle JA, de Courten B, et al. Impact of type 2 diabetes, obesity and glycaemic control on pregnancy outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57:308-314. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12521

29. Viana LV, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ. Dietary intervention in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on maternal and newborn outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3345-3355. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1530

30. Rowan JA, Rush EC, Plank LD, et al. Metformin in gestational diabetes: the offspring follow-up (MiG TOFU): body composition and metabolic outcomes at 7-9 years of age. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6:e000456. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000456

31. Hebert MF, Ma X, Naraharisetti SB, et al. Are we optimizing gestational diabetes treatment with glyburide? The pharmacologic basis for better clinical practice. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:607-614. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.5

32. Malek R, Davis SN. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety of glyburide for treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016;12:691-699. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2016.1187131

33. Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Solà I, et al. Glibenclamide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h102

34. Kavitha N, De S, Kanagasabai S. Oral hypoglycemic agents in pregnancy: an update. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2013;63:82-87. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0312-z

35. Weissgerber TL, Mudd LM. Preeclampsia and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0579-4

36. Kamana KC, Shakya S, Zhang H. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(suppl 2):14-20. doi: 10.1159/000371628

37. Mitanchez D, Yzydorczyk C, Simeoni U. What neonatal complications should the pediatrician be aware of in case of maternal gestational diabetes? World J Diabetes. 2015;6:734-743. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.734

38. Stanescu A, Stoicescu SM. Neonatal hypoglycemia screening in newborns from diabetic mothers—arguments and controversies. J Med Life. 2014;7(spec iss 3):51-52.

39. Kim C. Maternal outcomes and follow-up after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2014;31:292-301. doi: 10.1111/dme.12382

40. Stewart A, Malhotra A. Gestational diabetes and the neonate: challenges and solutions. Res Rep Neonatol. 2015;5:31-39. doi: 10.2147/RRN.S30971

41. Crume TL, Ogden L, West NA, et al. Association of exposure to diabetes in utero with adiposity and fat distribution in a multiethnic population of youth: the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes among Children (EPOCH) Study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:87-92. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1925-3

42. Crume TL, Ogden L, Daniels S, et al. The impact of in utero exposure to diabetes on childhood body mass index growth trajectories: the EPOCH study. J Pediatr. 2011;158:941-946. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.007

43. Levels of maternal care. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e41-e55. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003383

44. Caughey AB, Cheng YW, Stotland NE, et al. Maternal and paternal race/ethnicity are both associated with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:616.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.082

45. Yogev Y, Xenakis EM, Langer O. The association between preeclampsia and severity of gestational diabetes: the impact of glycemic control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1655-1660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.074

46. Brown J, Alwan NA, West J, et al. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD011970. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011970.pub2

47. Ceysens G, Rouiller D, Boulvain M. Exercise for the diabetic pregnant woman. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004225. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004225.pub2

48. Chawla R, Mukherjee JJ, Chawla M, et al. Expert group recommendations on the effective use of bolus insulin in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9:38. doi: 10.3390/medsci9020038

49. American Diabetes Association. Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S1-S2. doi: 10.2337/dc22-Sint

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as new-onset hyperglycemia detected in a pregnant woman after 24 weeks of gestation, affects 4% to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually1 and is a major challenge for health care professionals.2 During pregnancy, the body’s physiologic responses are altered to support the growing fetus. One of these changes is an increase in insulin resistance, which suggests that pregnancy alone increases the patient’s risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, several other factors also increase this risk, including maternal age, social barriers to care, obesity, poor weight control, and family history.

If not controlled, GDM results in poor health outcomes for the mother, such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and maternal T2D.3-5 For the infant, intrauterine exposure to persistent hyperglycemia is correlated with neonatal macrosomia, hypoglycemia, perinatal complications (eg, preterm delivery, fetal demise), and obesity and insulin resistance later in life.4

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are the patient’s main point of contact prior to pregnancy. This relationship makes PCPs a resource for the patient and specialists during and after pregnancy. In this article, we discuss risk factors and how to screen for GDM, provide an update on practice recommendations for treatment and management of GDM in primary care, and describe the effects of uncontrolled GDM.

Know the key risk factors

Prevention begins with identifying the major risk factors that contribute to the development of GDM. These include maternal age, social barriers to care, family history of prediabetes, and obesity and poor weight control.

Older age. A meta-analysis of 24 studies noted strong positive correlation between GDM risk and maternal age.6 One of the population-based cohort studies in the meta-analysis examined relationships between maternal age and pregnancy outcomes in women living in British Columbia, Canada (n = 203,414). Data suggested that the relative risk of GDM increased linearly with maternal age to 3.2, 4.2, and 4.4 among women ages ≥ 35, ≥ 40, and ≥ 45 years, respectively.7

Social barriers to care. Although the prevalence of GDM has increased over the past few decades,1 from 2011 to 2019 the increase in GDM in individuals at first live birth was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic/Latina women than in non-Hispanic White women.8 Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention further suggest that diabetes was more prevalent among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status as indicated by their level of education.9 Ogunwole et al10 suggest that racism is the root cause of these disparities and leads to long-term barriers to care (eg, socioeconomic deprivation, lack of health insurance, limited access to care, and poor health literacy), which ultimately contribute to the development of GDM and progression of diabetes. It is important for PCPs and all health professionals to be aware of these barriers so that they may practice mindfulness and deliver culturally sensitive care to patients from marginalized communities.

Family history of prediabetes. In a population-based cohort study (n = 7020), women with prediabetes (A1C, 5.7%-6.4%) were 2.8 times more likely to develop GDM compared with women with normal A1C (< 5.7%).11 Similar results were seen in a retrospective cohort study (n = 2812), in which women with prediabetes were more likely than women with a normal first trimester A1C to have GDM (29.1% vs 13.7%, respectively; adjusted relative risk = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15-1.89).12 In both studies, prediabetes was not associated with a higher risk for adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes.11,12

Continue to: While there are no current...

While there are no current guidelines for treating prediabetes in pregnancy, women diagnosed with prediabetes in 1 study were found to have significantly less weight gain during pregnancy compared with patients with normal A1C,12 suggesting there may be a benefit in early identification and intervention, although further research is needed.11 In a separate case-control study (n = 345 women with GDM; n = 800 control), high rates of gestational weight gain (> 0.41 kg/wk) were associated with an increased risk of GDM (odds ratio [OR] = 1.74; 95% CI, 1.16-2.60) compared with women with the lowest rate of gestational weight gain (0.27-0.4 kg/wk [OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 0.96-2.14]).13 Thus, it is helpful to have proactive conversations about family planning and adequate weight and glycemic control with high-risk patients to prepare for a healthy pregnancy.

Obesity and weight management. Patients who are overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI > 30) have a substantially increased risk of GDM (adjusted OR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.04-1.81), as seen in a retrospective cohort study of 1951 pregnant Malaysian women.14 Several factors have been found to contribute to successful weight control, including calorie prescription, a structured meal plan, high physical activity goals (60-90 min/d), daily weighing and monitoring of food intake, behavior therapy, and continued patient–provider contact.15

The safety, efficacy, and sustainability of weight loss with various dietary plans have been studied in individuals who are overweight and obese.16 Ultimately, energy expenditure must be greater than energy intake to promote weight loss. Conventional diets with continuous energy restriction (ie, low-fat, low-carbohydrate, and high-protein diets) have proven to be effective for short-term weight loss but data on long-term weight maintenance are limited.16 The Mediterranean diet, which is comprised mostly of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and grains—with a lower intake of meat and dairy—may reduce gestational weight gain and risk of GDM as suggested by a randomized controlled trial (RCT; n = 1252).17 Although the choice of diet is up to the patient, it is important to be aware of different diets or refer the patient to a registered dietician who can help the patient if needed.

Reduce risk with adequate weight and glycemic control

Prevention of GDM during pregnancy should focus on weight maintenance and optimal glycemic control. Two systematic reviews, one with 8 RCTs (n = 1792) and another with 5 studies (n = 539), assessed the efficacy and safety of energy-restricted dietary intervention on GDM prevention.18 The first review found a significant reduction in gestational weight gain and improved glycemic control without increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.18 The second review showed no clear difference between energy-restricted and non–energy-restricted diets on outcomes such as preeclampsia, gestational weight gain, large for gestational age, and macrosomia.18 These data suggest that while energy-restricted dietary interventions made no difference on maternal and fetal complications, they may still be safely used in pregnancy to reduce gestational weight gain and improve glycemic control.18

Once a woman is pregnant, it becomes difficult to lose weight because additional calories are needed to support a growing fetus. It is recommended that patients with healthy pregestational BMI consume an extra 200 to 300 calories/d after the first trimester. However, extra caloric intake in a woman with obesity who is pregnant leads to metabolic impairment and increased risk of diabetes for both the mother and fetus.19 Therefore, it is recommended that patients with obese pregestational BMI not consume additional calories because excess maternal fat is sufficient to support the energy needs of the growing fetus.19

Continue to: Ultimately, earlier intervention...

Ultimately, earlier intervention—prior to conception—helps patients prepare for a healthier pregnancy, resulting in better long-term outcomes. It is helpful to be familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of common approaches to weight management and to be able to refer patients to nutritionists for optimal planning. When establishing a dietary plan, consider patient-specific factors, such as cultural diets, financial and time constraints, and the patient’s readiness to make and maintain these changes. Consistent follow-up and behavioral therapy are necessary to maintain successful weight control.

There are many screening tools, but 1 is preferred in pregnancy

There are several ways to diagnose diabetes in patients who are not pregnant, including A1C, a fasting glucose test, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or random glucose testing (plus symptoms). However, the preferred method for diagnosing GDM is OGTT because it has a higher sensitivity.20 A1C, while a good measure of hyperglycemic stability, does not register hyperglycemia early enough to diagnose GDM and fasting glucose testing is less sensitive because for most women with GDM, that abnormal postprandial glucose level is the first glycemic abnormality.21

When to screen. Blood glucose levels should be checked in all pregnant women as part of their metabolic panel at the first prenatal visit. A reflex A1C for high glucose levels can be ordered based on the physician’s preference. This may help you to identify patients with prediabetes who are at risk for GDM and implement early behavioral and lifestyle changes. However, further research is needed to determine if intervention early in pregnancy can truly reduce the risk of GDM.11

Screening for GDM should be completed at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation20 because it is likely that this is when the hormonal effects of the placenta that contribute to insulin resistance set the woman up for postprandial hyperglycemia. Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the use of continuous glucose monitoring prior to 24 weeks of gestation to identify GDM.20 If persistent hyperglycemia is present before 24 weeks of gestation, it is considered evidence of a pre-existing metabolic abnormality and is diagnosed as “pregestational diabetes.” Treatment should follow guidelines established for women who had diabetes prior to pregnancy.

How to screen? There is ongoing discussion about what is the optimal screening method for GDM: a 1-step strategy with a fasting 75-g OGTT only, or a 2-step strategy with a 50-g non-fasting glucose load test followed by a fasting 100-g OGTT in women who do not meet the plasma glucose cutoff (TABLE 1).22-24 Hillier et al25 compared the effectiveness of these strategies in diagnosing GDM and identifying pregnancy complications for the mother and infant. They found that while the 1-step strategy resulted in a 2-fold increase in the diagnosis of GDM, it did not lead to better outcomes for mothers and infants when compared with the 2-step method.25 Currently, the majority of obstetricians (95%) prefer to use the 2-step method.24

Continue to: Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Management of GDM in most women starts with diabetes self-management education and support for therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as nutritional interventions that reduce hyperglycemia and contribute to healthy weight gain during pregnancy.20 This may include medical nutrition therapy that focuses on adequate nutrition for the mother and fetus. Currently, the recommended dietary intake for women who are pregnant (regardless of diabetes) includes a minimum of 175 g of carbohydrates, 71 g of daily protein, and at least 28 g of fiber. Further refinement of dietary intake, including carbohydrate restriction, should be done with guidance from a registered dietitian.20 If the obstetrics team does not include a registered dietitian, a referral to one may be necessary. Regular physical activity should be continued throughout pregnancy as tolerated. Social support, stress reduction, and good sleep hygiene should be encouraged as much as possible.

For successful outcomes, therapeutic lifestyle changes should be coupled with glucose monitoring. The Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus recommends that women with GDM monitor fasting blood glucose and typically 1-hour postprandial glucose. The glucose goals in GDM are as follows26:

- Fasting glucose < 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L), and either

- 1-hour postprandial glucose < 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L), or

- 2-hour postprandial glucose < 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L).

Importantly, in the second and third trimester, the A1C goal for women with GDM is 6.0%. This is lower than the more traditional A1C goal for 2 reasons: (1) increases in A1C, even within the normal range, increase adverse outcomes; and (2) pregnant women will have an increased red blood cell count turnover, which can lower the A1C.27 In a historical cohort study (n = 27,213), Abell et al28 found that women who have an A1C < 6.0% in the second and third trimester have the lowest risk of giving birth to large-for-gestational-age infants and for having preeclampsia.

Add insulin if glucose targets are not met

Most women who engage in therapeutic lifestyle change (70%-85%) can achieve an A1C < 6% and will not need to take medication to manage GDM.29 If pharmacotherapy is needed to manage glucose, insulin is the preferred treatment for all women with GDM.20 Treatment should be individualized based on the glucose trends the woman is experiencing. Common treatments include bedtime NPH if fasting hyperglycemia is most prominent and analogue insulin at mealtimes for women with prominent postprandial hyperglycemia.

Noninsulin agents such as metformin and sulfonylureas are not currently recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the American Diabetes Association for use in GDM.20,24 Despite being used for years in women with pregestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome, there is evidence that metformin crosses the placenta and fetal safety has not yet been established in RCTs. The Metformin in Gestational Diabetes: The Offspring Follow-Up (MiG TOFU) study was a longitudinal follow-up study that evaluated body composition and metabolic outcomes in children (ages 7-9 years) of women with GDM who had received metformin or insulin while pregnant.30 At age 9 years, children who were exposed to metformin weighed more and had a higher waist-to-height ratio and waist circumference than those exposed to insulin.30

Continue to: Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended...

Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended because of the risk of maternal and fetal hypoglycemia and concerns about this medication crossing the placenta.24,31,32 Specifically, in a 2015 meta-analysis and systematic review of 15 articles (n = 2509), glyburide had a higher risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and macrosomia than insulin or metformin.33 For women who cannot manage their glucose with therapeutic lifestyle changes and cannot take insulin, oral therapies may be considered if the risk-benefit ratio is balanced for that person.34

Watch for effects of poor glycemic control on mother, infant

Preeclampsia is defined as new-onset hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. The correlation between GDM and preeclampsia has partly been explained by their shared overlapping risk factors, including maternal obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and persistent hyperglycemia.35 On a biochemical level, these risk factors contribute to oxidative stress and systemic vascular dysfunction, which have been hypothesized as the underlying pathophysiology for the development of preeclampsia.35

Neonatal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight ≥ 4000 g, is a common complication that develops in 15% to 45% of infants of mothers with GDM.36 Placental transfer of glucose in mothers with hyperglycemia stimulates the secretion of neonatal insulin and the ultimate storage of the excess glucose as body fat. After delivery, the abrupt discontinuation of placental transfer of glucose to an infant who is actively secreting insulin leads to neonatal hypoglycemia, which if not detected or managed, can lead to long-term neurologic deficits, including recurrent seizures and developmental delays.37 Therefore, it is essential to screen for neonatal hypoglycemia immediately after birth and serially up to 12 hours.38

Postpartum T2D. Poor glycemic control increases the risk of increasing insulin resistance developing into T2D postpartum for mothers.39 It also increases the risk of obesity and insulin resistance later in life for the infant.40 A retrospective cohort study (n = 461) found a positive correlation between exposure to maternal GDM and elevated BMI in children ages 6 to 13 years.41 Kamana et al36 further discussed this correlation and suggested that exposure to maternal hyperglycemia in utero contributes to fetal programming of later adipose deposition. Children may develop without a notable increase in BMI until after puberty.42

Partner with specialists to improve outcomes

Although most women with GDM are managed by specialists (obstetricians, endocrinologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists),43 these patients are still seeking care from their family physicians for other complaints. These visits provide key touchpoints during pregnancy and are opportunities for PCPs to identify a pregnancy-related complication or provide additional education or referral to the obstetrician.

Continue to: Also, if you work in an area...

Also, if you work in an area where specialists are less accessible, you may be the clinician providing the majority of care to a patient with GDM. If this is the case, you’ll want to watch for the following risk factors, which should prompt a referral to specialty care:

- a previous pregnancy with GDM20

- a previous birth of an infant weighing > 4000 g44

- baseline history of hypertension45

- evidence of insulin resistance or polycystic ovary syndrome46,47

- a history of cardiovascular disease20

- a need to treat GDM with pharmacotherapy.48

Ensuring a smooth transition after the birth

Optimal communication and hand-offs throughout pregnancy and after delivery will benefit everyone. When the pregnant patient’s care has been managed by an obstetrician, it is important to address the following issues during the hand-off:

- baseline medical problems

- medical screenings and treatments in pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy screening)

- aspirin initiation, if indicated

- management of thyroid abnormalities

- management of mental health conditions

- postpartum glucose management and T2D screening postpartum

- management of complications identified during pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy).

Timing and other elements of postpartum care. The first postpartum screen should occur at 4 to 12 weeks postpartum. OGTT is recommended instead of A1C at this time because A1C may still be lowered by the increased red blood cell turnover related to pregnancy and blood loss at delivery. Because women with GDM have a 50% to 75% lifetime risk of T2D,20 patients with normal test results should be re-tested every 1 to 3 years using any of the standard screening methods (A1C, fasting glucose, or OGTT).20

After delivery it may be difficult for women to follow-up with their own personal health care because they are focused on the care of their baby. The increased use of telehealth may make postpartum follow-up visits easier to attend.

Visits present opportunities. Postpartum visits present another opportunity for PCPs to screen for diabetes and other postpartum complications, including depression and thyroid abnormalities. Visits are also an opportunity to discuss timely contraception so as to prevent an early, unplanned pregnancy. Other important aspects of postpartum care are outlined in TABLE 2.20,49

CORRESPONDENCE

Connie L. Ha, BS, OMS IV, Department of Primary Care, 1310 Club Drive, Touro University California, Vallejo, CA 94592; connie.ha@tu.edu

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as new-onset hyperglycemia detected in a pregnant woman after 24 weeks of gestation, affects 4% to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually1 and is a major challenge for health care professionals.2 During pregnancy, the body’s physiologic responses are altered to support the growing fetus. One of these changes is an increase in insulin resistance, which suggests that pregnancy alone increases the patient’s risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, several other factors also increase this risk, including maternal age, social barriers to care, obesity, poor weight control, and family history.

If not controlled, GDM results in poor health outcomes for the mother, such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and maternal T2D.3-5 For the infant, intrauterine exposure to persistent hyperglycemia is correlated with neonatal macrosomia, hypoglycemia, perinatal complications (eg, preterm delivery, fetal demise), and obesity and insulin resistance later in life.4

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are the patient’s main point of contact prior to pregnancy. This relationship makes PCPs a resource for the patient and specialists during and after pregnancy. In this article, we discuss risk factors and how to screen for GDM, provide an update on practice recommendations for treatment and management of GDM in primary care, and describe the effects of uncontrolled GDM.

Know the key risk factors

Prevention begins with identifying the major risk factors that contribute to the development of GDM. These include maternal age, social barriers to care, family history of prediabetes, and obesity and poor weight control.

Older age. A meta-analysis of 24 studies noted strong positive correlation between GDM risk and maternal age.6 One of the population-based cohort studies in the meta-analysis examined relationships between maternal age and pregnancy outcomes in women living in British Columbia, Canada (n = 203,414). Data suggested that the relative risk of GDM increased linearly with maternal age to 3.2, 4.2, and 4.4 among women ages ≥ 35, ≥ 40, and ≥ 45 years, respectively.7

Social barriers to care. Although the prevalence of GDM has increased over the past few decades,1 from 2011 to 2019 the increase in GDM in individuals at first live birth was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic/Latina women than in non-Hispanic White women.8 Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention further suggest that diabetes was more prevalent among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status as indicated by their level of education.9 Ogunwole et al10 suggest that racism is the root cause of these disparities and leads to long-term barriers to care (eg, socioeconomic deprivation, lack of health insurance, limited access to care, and poor health literacy), which ultimately contribute to the development of GDM and progression of diabetes. It is important for PCPs and all health professionals to be aware of these barriers so that they may practice mindfulness and deliver culturally sensitive care to patients from marginalized communities.

Family history of prediabetes. In a population-based cohort study (n = 7020), women with prediabetes (A1C, 5.7%-6.4%) were 2.8 times more likely to develop GDM compared with women with normal A1C (< 5.7%).11 Similar results were seen in a retrospective cohort study (n = 2812), in which women with prediabetes were more likely than women with a normal first trimester A1C to have GDM (29.1% vs 13.7%, respectively; adjusted relative risk = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15-1.89).12 In both studies, prediabetes was not associated with a higher risk for adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes.11,12

Continue to: While there are no current...

While there are no current guidelines for treating prediabetes in pregnancy, women diagnosed with prediabetes in 1 study were found to have significantly less weight gain during pregnancy compared with patients with normal A1C,12 suggesting there may be a benefit in early identification and intervention, although further research is needed.11 In a separate case-control study (n = 345 women with GDM; n = 800 control), high rates of gestational weight gain (> 0.41 kg/wk) were associated with an increased risk of GDM (odds ratio [OR] = 1.74; 95% CI, 1.16-2.60) compared with women with the lowest rate of gestational weight gain (0.27-0.4 kg/wk [OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 0.96-2.14]).13 Thus, it is helpful to have proactive conversations about family planning and adequate weight and glycemic control with high-risk patients to prepare for a healthy pregnancy.

Obesity and weight management. Patients who are overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI > 30) have a substantially increased risk of GDM (adjusted OR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.04-1.81), as seen in a retrospective cohort study of 1951 pregnant Malaysian women.14 Several factors have been found to contribute to successful weight control, including calorie prescription, a structured meal plan, high physical activity goals (60-90 min/d), daily weighing and monitoring of food intake, behavior therapy, and continued patient–provider contact.15

The safety, efficacy, and sustainability of weight loss with various dietary plans have been studied in individuals who are overweight and obese.16 Ultimately, energy expenditure must be greater than energy intake to promote weight loss. Conventional diets with continuous energy restriction (ie, low-fat, low-carbohydrate, and high-protein diets) have proven to be effective for short-term weight loss but data on long-term weight maintenance are limited.16 The Mediterranean diet, which is comprised mostly of vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish, and grains—with a lower intake of meat and dairy—may reduce gestational weight gain and risk of GDM as suggested by a randomized controlled trial (RCT; n = 1252).17 Although the choice of diet is up to the patient, it is important to be aware of different diets or refer the patient to a registered dietician who can help the patient if needed.

Reduce risk with adequate weight and glycemic control

Prevention of GDM during pregnancy should focus on weight maintenance and optimal glycemic control. Two systematic reviews, one with 8 RCTs (n = 1792) and another with 5 studies (n = 539), assessed the efficacy and safety of energy-restricted dietary intervention on GDM prevention.18 The first review found a significant reduction in gestational weight gain and improved glycemic control without increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.18 The second review showed no clear difference between energy-restricted and non–energy-restricted diets on outcomes such as preeclampsia, gestational weight gain, large for gestational age, and macrosomia.18 These data suggest that while energy-restricted dietary interventions made no difference on maternal and fetal complications, they may still be safely used in pregnancy to reduce gestational weight gain and improve glycemic control.18

Once a woman is pregnant, it becomes difficult to lose weight because additional calories are needed to support a growing fetus. It is recommended that patients with healthy pregestational BMI consume an extra 200 to 300 calories/d after the first trimester. However, extra caloric intake in a woman with obesity who is pregnant leads to metabolic impairment and increased risk of diabetes for both the mother and fetus.19 Therefore, it is recommended that patients with obese pregestational BMI not consume additional calories because excess maternal fat is sufficient to support the energy needs of the growing fetus.19

Continue to: Ultimately, earlier intervention...

Ultimately, earlier intervention—prior to conception—helps patients prepare for a healthier pregnancy, resulting in better long-term outcomes. It is helpful to be familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of common approaches to weight management and to be able to refer patients to nutritionists for optimal planning. When establishing a dietary plan, consider patient-specific factors, such as cultural diets, financial and time constraints, and the patient’s readiness to make and maintain these changes. Consistent follow-up and behavioral therapy are necessary to maintain successful weight control.

There are many screening tools, but 1 is preferred in pregnancy

There are several ways to diagnose diabetes in patients who are not pregnant, including A1C, a fasting glucose test, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or random glucose testing (plus symptoms). However, the preferred method for diagnosing GDM is OGTT because it has a higher sensitivity.20 A1C, while a good measure of hyperglycemic stability, does not register hyperglycemia early enough to diagnose GDM and fasting glucose testing is less sensitive because for most women with GDM, that abnormal postprandial glucose level is the first glycemic abnormality.21

When to screen. Blood glucose levels should be checked in all pregnant women as part of their metabolic panel at the first prenatal visit. A reflex A1C for high glucose levels can be ordered based on the physician’s preference. This may help you to identify patients with prediabetes who are at risk for GDM and implement early behavioral and lifestyle changes. However, further research is needed to determine if intervention early in pregnancy can truly reduce the risk of GDM.11

Screening for GDM should be completed at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation20 because it is likely that this is when the hormonal effects of the placenta that contribute to insulin resistance set the woman up for postprandial hyperglycemia. Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the use of continuous glucose monitoring prior to 24 weeks of gestation to identify GDM.20 If persistent hyperglycemia is present before 24 weeks of gestation, it is considered evidence of a pre-existing metabolic abnormality and is diagnosed as “pregestational diabetes.” Treatment should follow guidelines established for women who had diabetes prior to pregnancy.

How to screen? There is ongoing discussion about what is the optimal screening method for GDM: a 1-step strategy with a fasting 75-g OGTT only, or a 2-step strategy with a 50-g non-fasting glucose load test followed by a fasting 100-g OGTT in women who do not meet the plasma glucose cutoff (TABLE 1).22-24 Hillier et al25 compared the effectiveness of these strategies in diagnosing GDM and identifying pregnancy complications for the mother and infant. They found that while the 1-step strategy resulted in a 2-fold increase in the diagnosis of GDM, it did not lead to better outcomes for mothers and infants when compared with the 2-step method.25 Currently, the majority of obstetricians (95%) prefer to use the 2-step method.24

Continue to: Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Manage lifestyle, monitor glucose

Management of GDM in most women starts with diabetes self-management education and support for therapeutic lifestyle changes, such as nutritional interventions that reduce hyperglycemia and contribute to healthy weight gain during pregnancy.20 This may include medical nutrition therapy that focuses on adequate nutrition for the mother and fetus. Currently, the recommended dietary intake for women who are pregnant (regardless of diabetes) includes a minimum of 175 g of carbohydrates, 71 g of daily protein, and at least 28 g of fiber. Further refinement of dietary intake, including carbohydrate restriction, should be done with guidance from a registered dietitian.20 If the obstetrics team does not include a registered dietitian, a referral to one may be necessary. Regular physical activity should be continued throughout pregnancy as tolerated. Social support, stress reduction, and good sleep hygiene should be encouraged as much as possible.

For successful outcomes, therapeutic lifestyle changes should be coupled with glucose monitoring. The Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus recommends that women with GDM monitor fasting blood glucose and typically 1-hour postprandial glucose. The glucose goals in GDM are as follows26:

- Fasting glucose < 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L), and either

- 1-hour postprandial glucose < 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L), or

- 2-hour postprandial glucose < 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L).

Importantly, in the second and third trimester, the A1C goal for women with GDM is 6.0%. This is lower than the more traditional A1C goal for 2 reasons: (1) increases in A1C, even within the normal range, increase adverse outcomes; and (2) pregnant women will have an increased red blood cell count turnover, which can lower the A1C.27 In a historical cohort study (n = 27,213), Abell et al28 found that women who have an A1C < 6.0% in the second and third trimester have the lowest risk of giving birth to large-for-gestational-age infants and for having preeclampsia.

Add insulin if glucose targets are not met

Most women who engage in therapeutic lifestyle change (70%-85%) can achieve an A1C < 6% and will not need to take medication to manage GDM.29 If pharmacotherapy is needed to manage glucose, insulin is the preferred treatment for all women with GDM.20 Treatment should be individualized based on the glucose trends the woman is experiencing. Common treatments include bedtime NPH if fasting hyperglycemia is most prominent and analogue insulin at mealtimes for women with prominent postprandial hyperglycemia.

Noninsulin agents such as metformin and sulfonylureas are not currently recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the American Diabetes Association for use in GDM.20,24 Despite being used for years in women with pregestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome, there is evidence that metformin crosses the placenta and fetal safety has not yet been established in RCTs. The Metformin in Gestational Diabetes: The Offspring Follow-Up (MiG TOFU) study was a longitudinal follow-up study that evaluated body composition and metabolic outcomes in children (ages 7-9 years) of women with GDM who had received metformin or insulin while pregnant.30 At age 9 years, children who were exposed to metformin weighed more and had a higher waist-to-height ratio and waist circumference than those exposed to insulin.30

Continue to: Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended...

Sulfonylureas are no longer recommended because of the risk of maternal and fetal hypoglycemia and concerns about this medication crossing the placenta.24,31,32 Specifically, in a 2015 meta-analysis and systematic review of 15 articles (n = 2509), glyburide had a higher risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and macrosomia than insulin or metformin.33 For women who cannot manage their glucose with therapeutic lifestyle changes and cannot take insulin, oral therapies may be considered if the risk-benefit ratio is balanced for that person.34

Watch for effects of poor glycemic control on mother, infant

Preeclampsia is defined as new-onset hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. The correlation between GDM and preeclampsia has partly been explained by their shared overlapping risk factors, including maternal obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and persistent hyperglycemia.35 On a biochemical level, these risk factors contribute to oxidative stress and systemic vascular dysfunction, which have been hypothesized as the underlying pathophysiology for the development of preeclampsia.35

Neonatal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight ≥ 4000 g, is a common complication that develops in 15% to 45% of infants of mothers with GDM.36 Placental transfer of glucose in mothers with hyperglycemia stimulates the secretion of neonatal insulin and the ultimate storage of the excess glucose as body fat. After delivery, the abrupt discontinuation of placental transfer of glucose to an infant who is actively secreting insulin leads to neonatal hypoglycemia, which if not detected or managed, can lead to long-term neurologic deficits, including recurrent seizures and developmental delays.37 Therefore, it is essential to screen for neonatal hypoglycemia immediately after birth and serially up to 12 hours.38

Postpartum T2D. Poor glycemic control increases the risk of increasing insulin resistance developing into T2D postpartum for mothers.39 It also increases the risk of obesity and insulin resistance later in life for the infant.40 A retrospective cohort study (n = 461) found a positive correlation between exposure to maternal GDM and elevated BMI in children ages 6 to 13 years.41 Kamana et al36 further discussed this correlation and suggested that exposure to maternal hyperglycemia in utero contributes to fetal programming of later adipose deposition. Children may develop without a notable increase in BMI until after puberty.42

Partner with specialists to improve outcomes

Although most women with GDM are managed by specialists (obstetricians, endocrinologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists),43 these patients are still seeking care from their family physicians for other complaints. These visits provide key touchpoints during pregnancy and are opportunities for PCPs to identify a pregnancy-related complication or provide additional education or referral to the obstetrician.

Continue to: Also, if you work in an area...

Also, if you work in an area where specialists are less accessible, you may be the clinician providing the majority of care to a patient with GDM. If this is the case, you’ll want to watch for the following risk factors, which should prompt a referral to specialty care:

- a previous pregnancy with GDM20

- a previous birth of an infant weighing > 4000 g44

- baseline history of hypertension45

- evidence of insulin resistance or polycystic ovary syndrome46,47

- a history of cardiovascular disease20

- a need to treat GDM with pharmacotherapy.48

Ensuring a smooth transition after the birth

Optimal communication and hand-offs throughout pregnancy and after delivery will benefit everyone. When the pregnant patient’s care has been managed by an obstetrician, it is important to address the following issues during the hand-off:

- baseline medical problems

- medical screenings and treatments in pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy screening)

- aspirin initiation, if indicated

- management of thyroid abnormalities

- management of mental health conditions

- postpartum glucose management and T2D screening postpartum

- management of complications identified during pregnancy (retinopathy and nephropathy).

Timing and other elements of postpartum care. The first postpartum screen should occur at 4 to 12 weeks postpartum. OGTT is recommended instead of A1C at this time because A1C may still be lowered by the increased red blood cell turnover related to pregnancy and blood loss at delivery. Because women with GDM have a 50% to 75% lifetime risk of T2D,20 patients with normal test results should be re-tested every 1 to 3 years using any of the standard screening methods (A1C, fasting glucose, or OGTT).20

After delivery it may be difficult for women to follow-up with their own personal health care because they are focused on the care of their baby. The increased use of telehealth may make postpartum follow-up visits easier to attend.