User login

Emergency Imaging: Atraumatic Leg Pain

Case

A 96-year-old woman with a medical history of sciatica, vertigo, osteoporosis, and dementia presented with atraumatic right leg pain. She stated that the pain, which began 4 weeks prior to presentation, started in her right groin. The patient’s primary care physician diagnosed her with tendonitis, and prescribed acetaminophen/codeine and naproxen sodium for the pain. However, the patient’s pain progressively worsened to the point where she was no longer able to ambulate or bear weight on her right hip, prompting this visit to the ED.

On physical examination, the patient’s right hip was tender to palpation without any signs of physical deformity of the lower extremity. Upon hip flexion, she grimaced and communicated her pain.

Radiographs and computed tomography images taken of the right hip, femur, and pelvis demonstrated low-bone mineral density without fracture.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

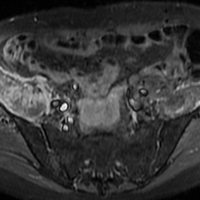

Axial and coronal edema-sensitive images of the pelvis demonstrated edema (increased signal) within the right psoas, iliacus, and iliopsoas muscles (red arrows, Figures 2a-2c), which were in contrast to the normal pelvic muscles on the left side (white arrows, Figures 2a-2c).

Iliopsoas Musculotendinous Unit

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit consists of the psoas major, the psoas minor, and the iliacus, with the psoas minor absent in 40% to 50% of cases.1,2 The iliacus muscle arises from the iliac wing and inserts with the psoas tendon onto the lesser trochanter of the femur. These muscles function as primary flexors of the thigh and trunk, as well as lateral flexors of the lower vertebral column.2

Signs and Symptoms

In non-sports-related injuries, iliopsoas tendon tears typically occur in elderly female patients—even in the absence of any trauma or known predisposing factors. Patients with iliopsoas tears typically present with hip or groin pain, and weakness with hip flexion, which clinically may mimic hip or sacral fracture. An anterior thigh mass or ecchymosis may also be present. Complete tear of the iliopsoas tendon usually occurs at or near the distal insertion at the lesser trochanter, and is often associated with proximal retraction of the tendon to the level of the femoral head.1

Imaging Studies

Iliopsoas tendon injury is best evaluated with MRI, particularly with fluid-sensitive sequences. Patients with iliopsoas tendon tears have abnormal signal in the muscle belly, likely related to edema and hemorrhage, and hematoma or fluid around the torn tendon and at the site of retraction. In pediatric patients, iliopsoas injury is typically an avulsion of the lesser trochanter prior to fusion of the apophysis.3,4 In adult patients with avulsion of the lesser trochanter, this injury is regarded as a sign of metastatic disease until proven otherwise.5

Treatment

Patients with iliopsoas tendon rupture are treated conservatively with rest, ice, and physical therapy (PT). Preservation of the distal muscular insertion of the lateral portion of the iliacus muscle is thought to play a role in positive clinical outcomes.3

The patient in this case was admitted to the hospital and treated for pain with standing acetaminophen, tramadol as needed, and a lidocaine patch. After attending multiple inpatient PT sessions, she was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

1. Bergman G. MRI Web clinic – October 2015: Iliopsoas tendinopathy. Radsource. http://radsource.us/iliopsoas-tendinopathy/. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Van Dyke JA, Holley HC, Anderson SD. Review of iliopsoas anatomy and pathology. Radiographics. 1987;7(1):53-84. doi:10.1148/radiographics.7.1.3448631.

3. Lecouvet FE, Demondion X, Leemrijse T, Vande Berg BC, Devogelaer JP, Malghem J. Spontaneous rupture of the distal iliopsoas tendon: clinical and imaging findings, with anatomic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(11):2341-2346. doi:10.1007/s00330-005-2811-0.

4. Bui KL, Ilaslan H, Recht M, Sundaram M. Iliopsoas injury: an MRI study of patterns and prevalence correlated with clinical findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):245-249. doi:10.1007/s00256-007-0414-3.

5. James SL, Davies AM. Atraumatic avulsion of the lesser trochanter as an indicator of tumour infiltration. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(2):512-514.

Case

A 96-year-old woman with a medical history of sciatica, vertigo, osteoporosis, and dementia presented with atraumatic right leg pain. She stated that the pain, which began 4 weeks prior to presentation, started in her right groin. The patient’s primary care physician diagnosed her with tendonitis, and prescribed acetaminophen/codeine and naproxen sodium for the pain. However, the patient’s pain progressively worsened to the point where she was no longer able to ambulate or bear weight on her right hip, prompting this visit to the ED.

On physical examination, the patient’s right hip was tender to palpation without any signs of physical deformity of the lower extremity. Upon hip flexion, she grimaced and communicated her pain.

Radiographs and computed tomography images taken of the right hip, femur, and pelvis demonstrated low-bone mineral density without fracture.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

Axial and coronal edema-sensitive images of the pelvis demonstrated edema (increased signal) within the right psoas, iliacus, and iliopsoas muscles (red arrows, Figures 2a-2c), which were in contrast to the normal pelvic muscles on the left side (white arrows, Figures 2a-2c).

Iliopsoas Musculotendinous Unit

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit consists of the psoas major, the psoas minor, and the iliacus, with the psoas minor absent in 40% to 50% of cases.1,2 The iliacus muscle arises from the iliac wing and inserts with the psoas tendon onto the lesser trochanter of the femur. These muscles function as primary flexors of the thigh and trunk, as well as lateral flexors of the lower vertebral column.2

Signs and Symptoms

In non-sports-related injuries, iliopsoas tendon tears typically occur in elderly female patients—even in the absence of any trauma or known predisposing factors. Patients with iliopsoas tears typically present with hip or groin pain, and weakness with hip flexion, which clinically may mimic hip or sacral fracture. An anterior thigh mass or ecchymosis may also be present. Complete tear of the iliopsoas tendon usually occurs at or near the distal insertion at the lesser trochanter, and is often associated with proximal retraction of the tendon to the level of the femoral head.1

Imaging Studies

Iliopsoas tendon injury is best evaluated with MRI, particularly with fluid-sensitive sequences. Patients with iliopsoas tendon tears have abnormal signal in the muscle belly, likely related to edema and hemorrhage, and hematoma or fluid around the torn tendon and at the site of retraction. In pediatric patients, iliopsoas injury is typically an avulsion of the lesser trochanter prior to fusion of the apophysis.3,4 In adult patients with avulsion of the lesser trochanter, this injury is regarded as a sign of metastatic disease until proven otherwise.5

Treatment

Patients with iliopsoas tendon rupture are treated conservatively with rest, ice, and physical therapy (PT). Preservation of the distal muscular insertion of the lateral portion of the iliacus muscle is thought to play a role in positive clinical outcomes.3

The patient in this case was admitted to the hospital and treated for pain with standing acetaminophen, tramadol as needed, and a lidocaine patch. After attending multiple inpatient PT sessions, she was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

Case

A 96-year-old woman with a medical history of sciatica, vertigo, osteoporosis, and dementia presented with atraumatic right leg pain. She stated that the pain, which began 4 weeks prior to presentation, started in her right groin. The patient’s primary care physician diagnosed her with tendonitis, and prescribed acetaminophen/codeine and naproxen sodium for the pain. However, the patient’s pain progressively worsened to the point where she was no longer able to ambulate or bear weight on her right hip, prompting this visit to the ED.

On physical examination, the patient’s right hip was tender to palpation without any signs of physical deformity of the lower extremity. Upon hip flexion, she grimaced and communicated her pain.

Radiographs and computed tomography images taken of the right hip, femur, and pelvis demonstrated low-bone mineral density without fracture.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

Axial and coronal edema-sensitive images of the pelvis demonstrated edema (increased signal) within the right psoas, iliacus, and iliopsoas muscles (red arrows, Figures 2a-2c), which were in contrast to the normal pelvic muscles on the left side (white arrows, Figures 2a-2c).

Iliopsoas Musculotendinous Unit

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit consists of the psoas major, the psoas minor, and the iliacus, with the psoas minor absent in 40% to 50% of cases.1,2 The iliacus muscle arises from the iliac wing and inserts with the psoas tendon onto the lesser trochanter of the femur. These muscles function as primary flexors of the thigh and trunk, as well as lateral flexors of the lower vertebral column.2

Signs and Symptoms

In non-sports-related injuries, iliopsoas tendon tears typically occur in elderly female patients—even in the absence of any trauma or known predisposing factors. Patients with iliopsoas tears typically present with hip or groin pain, and weakness with hip flexion, which clinically may mimic hip or sacral fracture. An anterior thigh mass or ecchymosis may also be present. Complete tear of the iliopsoas tendon usually occurs at or near the distal insertion at the lesser trochanter, and is often associated with proximal retraction of the tendon to the level of the femoral head.1

Imaging Studies

Iliopsoas tendon injury is best evaluated with MRI, particularly with fluid-sensitive sequences. Patients with iliopsoas tendon tears have abnormal signal in the muscle belly, likely related to edema and hemorrhage, and hematoma or fluid around the torn tendon and at the site of retraction. In pediatric patients, iliopsoas injury is typically an avulsion of the lesser trochanter prior to fusion of the apophysis.3,4 In adult patients with avulsion of the lesser trochanter, this injury is regarded as a sign of metastatic disease until proven otherwise.5

Treatment

Patients with iliopsoas tendon rupture are treated conservatively with rest, ice, and physical therapy (PT). Preservation of the distal muscular insertion of the lateral portion of the iliacus muscle is thought to play a role in positive clinical outcomes.3

The patient in this case was admitted to the hospital and treated for pain with standing acetaminophen, tramadol as needed, and a lidocaine patch. After attending multiple inpatient PT sessions, she was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

1. Bergman G. MRI Web clinic – October 2015: Iliopsoas tendinopathy. Radsource. http://radsource.us/iliopsoas-tendinopathy/. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Van Dyke JA, Holley HC, Anderson SD. Review of iliopsoas anatomy and pathology. Radiographics. 1987;7(1):53-84. doi:10.1148/radiographics.7.1.3448631.

3. Lecouvet FE, Demondion X, Leemrijse T, Vande Berg BC, Devogelaer JP, Malghem J. Spontaneous rupture of the distal iliopsoas tendon: clinical and imaging findings, with anatomic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(11):2341-2346. doi:10.1007/s00330-005-2811-0.

4. Bui KL, Ilaslan H, Recht M, Sundaram M. Iliopsoas injury: an MRI study of patterns and prevalence correlated with clinical findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):245-249. doi:10.1007/s00256-007-0414-3.

5. James SL, Davies AM. Atraumatic avulsion of the lesser trochanter as an indicator of tumour infiltration. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(2):512-514.

1. Bergman G. MRI Web clinic – October 2015: Iliopsoas tendinopathy. Radsource. http://radsource.us/iliopsoas-tendinopathy/. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Van Dyke JA, Holley HC, Anderson SD. Review of iliopsoas anatomy and pathology. Radiographics. 1987;7(1):53-84. doi:10.1148/radiographics.7.1.3448631.

3. Lecouvet FE, Demondion X, Leemrijse T, Vande Berg BC, Devogelaer JP, Malghem J. Spontaneous rupture of the distal iliopsoas tendon: clinical and imaging findings, with anatomic correlations. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(11):2341-2346. doi:10.1007/s00330-005-2811-0.

4. Bui KL, Ilaslan H, Recht M, Sundaram M. Iliopsoas injury: an MRI study of patterns and prevalence correlated with clinical findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):245-249. doi:10.1007/s00256-007-0414-3.

5. James SL, Davies AM. Atraumatic avulsion of the lesser trochanter as an indicator of tumour infiltration. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(2):512-514.

Emergency Imaging: Left Periorbital Swelling

Case

A 3-year-old boy was brought to the ED by his parents for evaluation of left periorbital swelling. A few days prior to presentation, the child was seen at an outpatient center where he was diagnosed with preseptal cellulitis and given an oral antibiotic. However, even after receiving three doses of the antibiotic, the periorbital swelling and redness around the child’s eye worsened, prompting this visit to the ED.

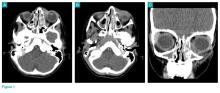

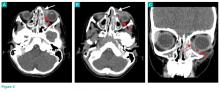

Physical examination revealed edema and erythema both above and below the left eye, with associated tenderness to palpation. A contrast-enhanced maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan, with special attention to the orbits, was ordered; representative images are shown (Figure 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

The CT images of the orbits demonstrated edema in the superficial left eyelid (white arrows, Figure 2a and 2b) and left deep orbital septum (red arrows, Figure 2a-2c). A peripherally enhancing fluid collection centered in the left nasolacrimal gland was present (red asterisks, Figure 2b and 2c) with mild mass effect on the left globe. Opacification was also noted within the paranasal sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a-2c). Together these findings indicated sinusitis with dacryocystitis and orbital cellulitis.

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is an infection or inflammation of the lacrimal sac, usually developing secondary to blockage of the nasolacrimal duct. Orbital cellulitis is an infection involving the contents of the orbit, including the fat and ocular muscles. Orbital cellulitis should not be confused with preseptal cellulitis, which is an infection involving the eyelid occurring posterior to the orbital septum. While both of these conditions are more common in children than in adults, preseptal cellulitis is much more common than orbital cellulitis.

Preseptal Cellulitis

Preseptal cellulitis is typically due to local trauma, local skin infection, or dacryocystitis.1 Preseptal cellulitis rarely extends into the orbit, though a minority of cases have been reported in patients with concomitant dacryocystitis.2 Orbital cellulitis most commonly results from paranasal sinus disease, particularly of the ethmoid sinus, which is only separated from the orbit by the thin lamina papyracea.3 While both preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis can cause eyelid swelling and erythema, preseptal cellulitis is typically a mild condition. Orbital cellulitis, however, is a serious medical emergency that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to avoid loss of vision and intracranial complications, such as venous thrombosis and empyema.3

Imaging Studies

Although the clinical features of orbital cellulitis (eg, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, pain with ocular movement) can sometimes distinguish it from preseptal cellulitis, imaging studies are helpful to confirm the diagnosis.4 As previously noted, prompt recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of orbital cellulitis are essential to avoid serious complications.

Computed tomography has a high specificity and sensitivity in detecting the extension of infection into the orbit and associated complications such as subperiosteal or intracranial abscess. For patients in whom intravenous (IV) contrast is contraindicated or who wish to avoid ionizing radiation, magnetic resonance imaging is a useful alternate modality, and diffusion-weighted imaging is particularly sensitive in diagnosing abscess.5

Treatment

1. Baring DE, Hilmi OJ. An evidence based review of periorbital cellulitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(1):57-64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02258.x.

2. Kikkawa DO, Heinz GW, Martin RT, Nunery WN, Eiseman AS. Orbital cellulitis and abscess secondary to dacryocystitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(8):1096-1099.

3. Mathew AV, Craig E, Al-Mahmoud R, et al. Paediatric post-septal and pre-septal cellulitis: 10 years’ experience at a tertiary-level children’s hospital. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1033):20130503. doi:10.1259/bjr.20130503.

4. Rudloe TF, Harper MB, Prabhu SP, Rahbar R, Vanderveen D, Kimia AA. Acute periorbital infections: who needs emergent imaging? Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e719-e726. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1709.

5. Sepahdari AR, Aakalu VK, Kapur R, et al. MRI of orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess: the role of diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(3):W244-W250. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1838.

6. Ho CF, Huang YC, Wang CJ, Chiu CH, Lin TY. Clinical analysis of computed tomography-staged orbital cellulitis in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40(6):518-524.

Case

A 3-year-old boy was brought to the ED by his parents for evaluation of left periorbital swelling. A few days prior to presentation, the child was seen at an outpatient center where he was diagnosed with preseptal cellulitis and given an oral antibiotic. However, even after receiving three doses of the antibiotic, the periorbital swelling and redness around the child’s eye worsened, prompting this visit to the ED.

Physical examination revealed edema and erythema both above and below the left eye, with associated tenderness to palpation. A contrast-enhanced maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan, with special attention to the orbits, was ordered; representative images are shown (Figure 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

The CT images of the orbits demonstrated edema in the superficial left eyelid (white arrows, Figure 2a and 2b) and left deep orbital septum (red arrows, Figure 2a-2c). A peripherally enhancing fluid collection centered in the left nasolacrimal gland was present (red asterisks, Figure 2b and 2c) with mild mass effect on the left globe. Opacification was also noted within the paranasal sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a-2c). Together these findings indicated sinusitis with dacryocystitis and orbital cellulitis.

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is an infection or inflammation of the lacrimal sac, usually developing secondary to blockage of the nasolacrimal duct. Orbital cellulitis is an infection involving the contents of the orbit, including the fat and ocular muscles. Orbital cellulitis should not be confused with preseptal cellulitis, which is an infection involving the eyelid occurring posterior to the orbital septum. While both of these conditions are more common in children than in adults, preseptal cellulitis is much more common than orbital cellulitis.

Preseptal Cellulitis

Preseptal cellulitis is typically due to local trauma, local skin infection, or dacryocystitis.1 Preseptal cellulitis rarely extends into the orbit, though a minority of cases have been reported in patients with concomitant dacryocystitis.2 Orbital cellulitis most commonly results from paranasal sinus disease, particularly of the ethmoid sinus, which is only separated from the orbit by the thin lamina papyracea.3 While both preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis can cause eyelid swelling and erythema, preseptal cellulitis is typically a mild condition. Orbital cellulitis, however, is a serious medical emergency that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to avoid loss of vision and intracranial complications, such as venous thrombosis and empyema.3

Imaging Studies

Although the clinical features of orbital cellulitis (eg, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, pain with ocular movement) can sometimes distinguish it from preseptal cellulitis, imaging studies are helpful to confirm the diagnosis.4 As previously noted, prompt recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of orbital cellulitis are essential to avoid serious complications.

Computed tomography has a high specificity and sensitivity in detecting the extension of infection into the orbit and associated complications such as subperiosteal or intracranial abscess. For patients in whom intravenous (IV) contrast is contraindicated or who wish to avoid ionizing radiation, magnetic resonance imaging is a useful alternate modality, and diffusion-weighted imaging is particularly sensitive in diagnosing abscess.5

Treatment

Case

A 3-year-old boy was brought to the ED by his parents for evaluation of left periorbital swelling. A few days prior to presentation, the child was seen at an outpatient center where he was diagnosed with preseptal cellulitis and given an oral antibiotic. However, even after receiving three doses of the antibiotic, the periorbital swelling and redness around the child’s eye worsened, prompting this visit to the ED.

Physical examination revealed edema and erythema both above and below the left eye, with associated tenderness to palpation. A contrast-enhanced maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan, with special attention to the orbits, was ordered; representative images are shown (Figure 1a-1c).

What is the diagnosis?

Answer

The CT images of the orbits demonstrated edema in the superficial left eyelid (white arrows, Figure 2a and 2b) and left deep orbital septum (red arrows, Figure 2a-2c). A peripherally enhancing fluid collection centered in the left nasolacrimal gland was present (red asterisks, Figure 2b and 2c) with mild mass effect on the left globe. Opacification was also noted within the paranasal sinuses (white asterisks, Figure 2a-2c). Together these findings indicated sinusitis with dacryocystitis and orbital cellulitis.

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is an infection or inflammation of the lacrimal sac, usually developing secondary to blockage of the nasolacrimal duct. Orbital cellulitis is an infection involving the contents of the orbit, including the fat and ocular muscles. Orbital cellulitis should not be confused with preseptal cellulitis, which is an infection involving the eyelid occurring posterior to the orbital septum. While both of these conditions are more common in children than in adults, preseptal cellulitis is much more common than orbital cellulitis.

Preseptal Cellulitis

Preseptal cellulitis is typically due to local trauma, local skin infection, or dacryocystitis.1 Preseptal cellulitis rarely extends into the orbit, though a minority of cases have been reported in patients with concomitant dacryocystitis.2 Orbital cellulitis most commonly results from paranasal sinus disease, particularly of the ethmoid sinus, which is only separated from the orbit by the thin lamina papyracea.3 While both preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis can cause eyelid swelling and erythema, preseptal cellulitis is typically a mild condition. Orbital cellulitis, however, is a serious medical emergency that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to avoid loss of vision and intracranial complications, such as venous thrombosis and empyema.3

Imaging Studies

Although the clinical features of orbital cellulitis (eg, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, pain with ocular movement) can sometimes distinguish it from preseptal cellulitis, imaging studies are helpful to confirm the diagnosis.4 As previously noted, prompt recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of orbital cellulitis are essential to avoid serious complications.

Computed tomography has a high specificity and sensitivity in detecting the extension of infection into the orbit and associated complications such as subperiosteal or intracranial abscess. For patients in whom intravenous (IV) contrast is contraindicated or who wish to avoid ionizing radiation, magnetic resonance imaging is a useful alternate modality, and diffusion-weighted imaging is particularly sensitive in diagnosing abscess.5

Treatment

1. Baring DE, Hilmi OJ. An evidence based review of periorbital cellulitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(1):57-64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02258.x.

2. Kikkawa DO, Heinz GW, Martin RT, Nunery WN, Eiseman AS. Orbital cellulitis and abscess secondary to dacryocystitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(8):1096-1099.

3. Mathew AV, Craig E, Al-Mahmoud R, et al. Paediatric post-septal and pre-septal cellulitis: 10 years’ experience at a tertiary-level children’s hospital. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1033):20130503. doi:10.1259/bjr.20130503.

4. Rudloe TF, Harper MB, Prabhu SP, Rahbar R, Vanderveen D, Kimia AA. Acute periorbital infections: who needs emergent imaging? Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e719-e726. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1709.

5. Sepahdari AR, Aakalu VK, Kapur R, et al. MRI of orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess: the role of diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(3):W244-W250. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1838.

6. Ho CF, Huang YC, Wang CJ, Chiu CH, Lin TY. Clinical analysis of computed tomography-staged orbital cellulitis in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40(6):518-524.

1. Baring DE, Hilmi OJ. An evidence based review of periorbital cellulitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(1):57-64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02258.x.

2. Kikkawa DO, Heinz GW, Martin RT, Nunery WN, Eiseman AS. Orbital cellulitis and abscess secondary to dacryocystitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(8):1096-1099.

3. Mathew AV, Craig E, Al-Mahmoud R, et al. Paediatric post-septal and pre-septal cellulitis: 10 years’ experience at a tertiary-level children’s hospital. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1033):20130503. doi:10.1259/bjr.20130503.

4. Rudloe TF, Harper MB, Prabhu SP, Rahbar R, Vanderveen D, Kimia AA. Acute periorbital infections: who needs emergent imaging? Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e719-e726. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1709.

5. Sepahdari AR, Aakalu VK, Kapur R, et al. MRI of orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess: the role of diffusion-weighted imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(3):W244-W250. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1838.

6. Ho CF, Huang YC, Wang CJ, Chiu CH, Lin TY. Clinical analysis of computed tomography-staged orbital cellulitis in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40(6):518-524.

Emergency Imaging: Multiple Comorbidities With Fever and Nonproductive Cough

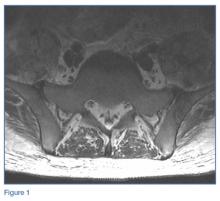

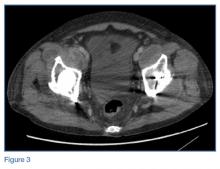

Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with a left shift. Chest radiographs were negative for pneumonia. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the lumbar spine was obtained to evaluate for diskitis osteomyelitis. A radiograph of the pelvis was also obtained to evaluate the patient’s THAs, and a computed tomography scan (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained for further evaluation. Representative CT, radiographic, and MRI images are shown at left (Figures 1-3).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Answer

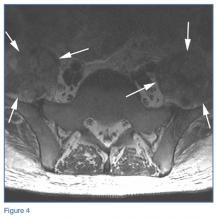

The MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated no evidence of diskitis osteomyelitis. However, T2-weighted axial images showed enlarged heterogeneous bilateral psoas muscles with bright signal, indicating the presence of fluid (white arrows, Figure 4).

On the pelvic radiographs, both femoral heads appeared off-center within the acetabular cups (red arrows, Figure 5). This eccentric positioning indicated wear of the polyethylene in the THAs that normally occupies the space between the acetabular cup and the femoral head. In addition, focal lucency in the right acetabulum indicated breakdown of the bone, a condition referred to as osteolysis (white asterisk, Figure 5).

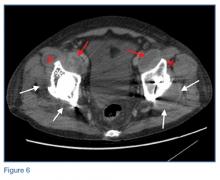

An abdominopelvic CT scan with contrast was performed and confirmed the findings of polyethylene wear and osteolysis. The CT scan also demonstrated large bilateral hip joint effusions (white arrows, Figure 6), decompressed along distended bilateral iliopsoas bursae (red asterisks, Figure 6), and communicating with the bilateral psoas muscle collections (red arrows, Figure 6).

Osteolysis With Iliopsoas Bursitis

Bursae are fluid-filled sacs lined by synovial tissue located throughout the body to reduce friction at sites of movement between muscles, bones, and tendons. Bursitis develops when these sacs become inflamed and/or infected and fill with fluid. The iliopsoas bursa lies between the anterior capsule of the hip and the psoas tendon, iliacus tendon, and muscle fibers.1,2 This bursa frequently communicates with the hip joint.3,4 Iliopsoas bursal distension has been reported following THA in the setting of polyethylene wear,5 and aseptic bursitis is a commonly seen incidental finding at the time of revision surgery.6

In this patient, long-standing polyethylene-induced synovitis had markedly expanded the hip joints and iliopsoas bursae, eventually resulting in superinfection, which accounted for the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment

Based on the imaging findings, interventional radiology services were contacted. The interventional radiologist drained the bilateral psoas abscesses. Cultures of the fluid were positive for both methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA). The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of MRSA and MSSA with intravenous antibiotic therapy. He recovered from the infection and was discharged on hospital day 2, with instructions to follow up with an orthopedic surgeon to discuss eventual revision of the bilateral THAs.

1. Chandler SB. The iliopsoas bursa in man. Anatom Record. 1934;58(3),235-240. doi:10.1002/ar.1090580304.

2. Tatu L, Parratte B, Vuillier F, Diop M, Monnier G. Descriptive anatomy of the femoral portion of the iliopsoas muscle. Anatomical basis of anterior snapping of the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23(6):371-374.

3. Meaney JF, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Etherington R, Ritchie DA, McCall IW, Whitehouse GH. Ilio-psoas bursa enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1992;45(3):161-168.

4. Warren R, Kaye JJ, Salvati EA. Arthrographic demonstration of an enlarged iliopsoas bursa complicating osteoarthritis of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(3):413-415.

5. Cheung YM, Gupte CM, Beverly MJ. Iliopsoas bursitis following total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(10):720-723. Epub 2004 Oct 23. doi:10.1007/s00402-004-0751-9.

6. Howie DW, Cain CM, Cornish BL. Pseudo-abscess of the psoas bursa in failed double-cup arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:29-32.

Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with a left shift. Chest radiographs were negative for pneumonia. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the lumbar spine was obtained to evaluate for diskitis osteomyelitis. A radiograph of the pelvis was also obtained to evaluate the patient’s THAs, and a computed tomography scan (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained for further evaluation. Representative CT, radiographic, and MRI images are shown at left (Figures 1-3).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Answer

The MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated no evidence of diskitis osteomyelitis. However, T2-weighted axial images showed enlarged heterogeneous bilateral psoas muscles with bright signal, indicating the presence of fluid (white arrows, Figure 4).

On the pelvic radiographs, both femoral heads appeared off-center within the acetabular cups (red arrows, Figure 5). This eccentric positioning indicated wear of the polyethylene in the THAs that normally occupies the space between the acetabular cup and the femoral head. In addition, focal lucency in the right acetabulum indicated breakdown of the bone, a condition referred to as osteolysis (white asterisk, Figure 5).

An abdominopelvic CT scan with contrast was performed and confirmed the findings of polyethylene wear and osteolysis. The CT scan also demonstrated large bilateral hip joint effusions (white arrows, Figure 6), decompressed along distended bilateral iliopsoas bursae (red asterisks, Figure 6), and communicating with the bilateral psoas muscle collections (red arrows, Figure 6).

Osteolysis With Iliopsoas Bursitis

Bursae are fluid-filled sacs lined by synovial tissue located throughout the body to reduce friction at sites of movement between muscles, bones, and tendons. Bursitis develops when these sacs become inflamed and/or infected and fill with fluid. The iliopsoas bursa lies between the anterior capsule of the hip and the psoas tendon, iliacus tendon, and muscle fibers.1,2 This bursa frequently communicates with the hip joint.3,4 Iliopsoas bursal distension has been reported following THA in the setting of polyethylene wear,5 and aseptic bursitis is a commonly seen incidental finding at the time of revision surgery.6

In this patient, long-standing polyethylene-induced synovitis had markedly expanded the hip joints and iliopsoas bursae, eventually resulting in superinfection, which accounted for the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment

Based on the imaging findings, interventional radiology services were contacted. The interventional radiologist drained the bilateral psoas abscesses. Cultures of the fluid were positive for both methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA). The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of MRSA and MSSA with intravenous antibiotic therapy. He recovered from the infection and was discharged on hospital day 2, with instructions to follow up with an orthopedic surgeon to discuss eventual revision of the bilateral THAs.

Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with a left shift. Chest radiographs were negative for pneumonia. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the lumbar spine was obtained to evaluate for diskitis osteomyelitis. A radiograph of the pelvis was also obtained to evaluate the patient’s THAs, and a computed tomography scan (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained for further evaluation. Representative CT, radiographic, and MRI images are shown at left (Figures 1-3).

What is the suspected diagnosis?

Answer

The MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated no evidence of diskitis osteomyelitis. However, T2-weighted axial images showed enlarged heterogeneous bilateral psoas muscles with bright signal, indicating the presence of fluid (white arrows, Figure 4).

On the pelvic radiographs, both femoral heads appeared off-center within the acetabular cups (red arrows, Figure 5). This eccentric positioning indicated wear of the polyethylene in the THAs that normally occupies the space between the acetabular cup and the femoral head. In addition, focal lucency in the right acetabulum indicated breakdown of the bone, a condition referred to as osteolysis (white asterisk, Figure 5).

An abdominopelvic CT scan with contrast was performed and confirmed the findings of polyethylene wear and osteolysis. The CT scan also demonstrated large bilateral hip joint effusions (white arrows, Figure 6), decompressed along distended bilateral iliopsoas bursae (red asterisks, Figure 6), and communicating with the bilateral psoas muscle collections (red arrows, Figure 6).

Osteolysis With Iliopsoas Bursitis

Bursae are fluid-filled sacs lined by synovial tissue located throughout the body to reduce friction at sites of movement between muscles, bones, and tendons. Bursitis develops when these sacs become inflamed and/or infected and fill with fluid. The iliopsoas bursa lies between the anterior capsule of the hip and the psoas tendon, iliacus tendon, and muscle fibers.1,2 This bursa frequently communicates with the hip joint.3,4 Iliopsoas bursal distension has been reported following THA in the setting of polyethylene wear,5 and aseptic bursitis is a commonly seen incidental finding at the time of revision surgery.6

In this patient, long-standing polyethylene-induced synovitis had markedly expanded the hip joints and iliopsoas bursae, eventually resulting in superinfection, which accounted for the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment

Based on the imaging findings, interventional radiology services were contacted. The interventional radiologist drained the bilateral psoas abscesses. Cultures of the fluid were positive for both methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA). The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of MRSA and MSSA with intravenous antibiotic therapy. He recovered from the infection and was discharged on hospital day 2, with instructions to follow up with an orthopedic surgeon to discuss eventual revision of the bilateral THAs.

1. Chandler SB. The iliopsoas bursa in man. Anatom Record. 1934;58(3),235-240. doi:10.1002/ar.1090580304.

2. Tatu L, Parratte B, Vuillier F, Diop M, Monnier G. Descriptive anatomy of the femoral portion of the iliopsoas muscle. Anatomical basis of anterior snapping of the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23(6):371-374.

3. Meaney JF, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Etherington R, Ritchie DA, McCall IW, Whitehouse GH. Ilio-psoas bursa enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1992;45(3):161-168.

4. Warren R, Kaye JJ, Salvati EA. Arthrographic demonstration of an enlarged iliopsoas bursa complicating osteoarthritis of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(3):413-415.

5. Cheung YM, Gupte CM, Beverly MJ. Iliopsoas bursitis following total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(10):720-723. Epub 2004 Oct 23. doi:10.1007/s00402-004-0751-9.

6. Howie DW, Cain CM, Cornish BL. Pseudo-abscess of the psoas bursa in failed double-cup arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:29-32.

1. Chandler SB. The iliopsoas bursa in man. Anatom Record. 1934;58(3),235-240. doi:10.1002/ar.1090580304.

2. Tatu L, Parratte B, Vuillier F, Diop M, Monnier G. Descriptive anatomy of the femoral portion of the iliopsoas muscle. Anatomical basis of anterior snapping of the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23(6):371-374.

3. Meaney JF, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Etherington R, Ritchie DA, McCall IW, Whitehouse GH. Ilio-psoas bursa enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1992;45(3):161-168.

4. Warren R, Kaye JJ, Salvati EA. Arthrographic demonstration of an enlarged iliopsoas bursa complicating osteoarthritis of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(3):413-415.

5. Cheung YM, Gupte CM, Beverly MJ. Iliopsoas bursitis following total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(10):720-723. Epub 2004 Oct 23. doi:10.1007/s00402-004-0751-9.

6. Howie DW, Cain CM, Cornish BL. Pseudo-abscess of the psoas bursa in failed double-cup arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:29-32.