User login

Order errors not reduced with limiting number of open records

Background: An estimated 600,000 patients in U.S. hospitals had an order placed in their record that was meant for another patient in 2016. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the Joint Commission recommend that EHRs limit the number of open records to one at a time based on expert opinion only. There is wide variation in the number of open records allowed among EHRs across the United States currently.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Large health system in New York.

Synopsis: There were 3,356 clinicians (inpatient, outpatient, ED) randomized in a 1:1 ratio into either a restricted group (one open record at a time) or an unrestricted group (up to four open records at a time). In this study, 12,140,298 orders, in 4,486,631 order sessions, were analyzed with the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder (RAR) measure to identify wrong-patient orders. The proportion of wrong-patient order sessions were 90.7 vs. 88.0 per 100,000 order sessions for the restricted versus unrestricted groups (odds ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.20). There were no statistically significant differences in wrong-patient order sessions between the restricted and unrestricted groups in any clinical setting examined (inpatient, outpatient, ED).

Despite the ability to have up to four open records at one time in the unrestricted group, 66% of the order sessions were completed with only one record open in that group. This limited the power of the study to detect a difference in risk of order errors between the restricted and unrestricted groups.

Bottom line: Limiting clinicians to only one open record did not reduce the proportion of wrong-patient orders, compared with allowing up to four open records concurrently.

Citation: Adelman JS et al. Effect of restriction of the number of concurrently open records in an electronic health record on wrong-patient order errors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;32(18):1780-7.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: An estimated 600,000 patients in U.S. hospitals had an order placed in their record that was meant for another patient in 2016. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the Joint Commission recommend that EHRs limit the number of open records to one at a time based on expert opinion only. There is wide variation in the number of open records allowed among EHRs across the United States currently.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Large health system in New York.

Synopsis: There were 3,356 clinicians (inpatient, outpatient, ED) randomized in a 1:1 ratio into either a restricted group (one open record at a time) or an unrestricted group (up to four open records at a time). In this study, 12,140,298 orders, in 4,486,631 order sessions, were analyzed with the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder (RAR) measure to identify wrong-patient orders. The proportion of wrong-patient order sessions were 90.7 vs. 88.0 per 100,000 order sessions for the restricted versus unrestricted groups (odds ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.20). There were no statistically significant differences in wrong-patient order sessions between the restricted and unrestricted groups in any clinical setting examined (inpatient, outpatient, ED).

Despite the ability to have up to four open records at one time in the unrestricted group, 66% of the order sessions were completed with only one record open in that group. This limited the power of the study to detect a difference in risk of order errors between the restricted and unrestricted groups.

Bottom line: Limiting clinicians to only one open record did not reduce the proportion of wrong-patient orders, compared with allowing up to four open records concurrently.

Citation: Adelman JS et al. Effect of restriction of the number of concurrently open records in an electronic health record on wrong-patient order errors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;32(18):1780-7.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: An estimated 600,000 patients in U.S. hospitals had an order placed in their record that was meant for another patient in 2016. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the Joint Commission recommend that EHRs limit the number of open records to one at a time based on expert opinion only. There is wide variation in the number of open records allowed among EHRs across the United States currently.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Large health system in New York.

Synopsis: There were 3,356 clinicians (inpatient, outpatient, ED) randomized in a 1:1 ratio into either a restricted group (one open record at a time) or an unrestricted group (up to four open records at a time). In this study, 12,140,298 orders, in 4,486,631 order sessions, were analyzed with the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder (RAR) measure to identify wrong-patient orders. The proportion of wrong-patient order sessions were 90.7 vs. 88.0 per 100,000 order sessions for the restricted versus unrestricted groups (odds ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.20). There were no statistically significant differences in wrong-patient order sessions between the restricted and unrestricted groups in any clinical setting examined (inpatient, outpatient, ED).

Despite the ability to have up to four open records at one time in the unrestricted group, 66% of the order sessions were completed with only one record open in that group. This limited the power of the study to detect a difference in risk of order errors between the restricted and unrestricted groups.

Bottom line: Limiting clinicians to only one open record did not reduce the proportion of wrong-patient orders, compared with allowing up to four open records concurrently.

Citation: Adelman JS et al. Effect of restriction of the number of concurrently open records in an electronic health record on wrong-patient order errors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;32(18):1780-7.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Hospital vs. outpatient management comparable for elderly syncope patients

Background: In the United States, there are over 1 million visits to EDs for syncope with a greater than 50% hospitalization rate for older adult patients. There remains uncertainty around which patients without an identified cause for the syncope could be discharged from the ED and managed as an outpatient.

Study design: Propensity score analysis.

Setting: EDs from 11 nonprofit academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Prospective data for 2,492 patients aged 60 years and older who did not have an identified cause in the ED for their presenting complaint of syncope were included in the propensity score analysis resulting in a sample size of 1,064 with 532 patients in each of the discharged and hospitalized groups. There was no significant difference in risk of 30-day post-ED serious adverse events between the hospitalized patients (4.89%; 95% confidence interval, 3.06%-6.72%) and discharged patients (2.82%; 95% CI, 1.41%-4.23%; risk difference 2.07%; 95% CI, –0.24% to 4.38%). There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality post–ED visit.

These results show no clinical benefit in hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope after ED evaluation suggesting that it would be reasonable to proceed with outpatient management and evaluation of these patients.

Bottom line: Consider discharging older patients home from the ED who do not have high risk factors and no identified cause of their syncope.

Citation: Probst MA et al. Clinical benefit of hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope: A propensity-matched analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;74(2):260-9.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: In the United States, there are over 1 million visits to EDs for syncope with a greater than 50% hospitalization rate for older adult patients. There remains uncertainty around which patients without an identified cause for the syncope could be discharged from the ED and managed as an outpatient.

Study design: Propensity score analysis.

Setting: EDs from 11 nonprofit academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Prospective data for 2,492 patients aged 60 years and older who did not have an identified cause in the ED for their presenting complaint of syncope were included in the propensity score analysis resulting in a sample size of 1,064 with 532 patients in each of the discharged and hospitalized groups. There was no significant difference in risk of 30-day post-ED serious adverse events between the hospitalized patients (4.89%; 95% confidence interval, 3.06%-6.72%) and discharged patients (2.82%; 95% CI, 1.41%-4.23%; risk difference 2.07%; 95% CI, –0.24% to 4.38%). There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality post–ED visit.

These results show no clinical benefit in hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope after ED evaluation suggesting that it would be reasonable to proceed with outpatient management and evaluation of these patients.

Bottom line: Consider discharging older patients home from the ED who do not have high risk factors and no identified cause of their syncope.

Citation: Probst MA et al. Clinical benefit of hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope: A propensity-matched analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;74(2):260-9.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: In the United States, there are over 1 million visits to EDs for syncope with a greater than 50% hospitalization rate for older adult patients. There remains uncertainty around which patients without an identified cause for the syncope could be discharged from the ED and managed as an outpatient.

Study design: Propensity score analysis.

Setting: EDs from 11 nonprofit academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Prospective data for 2,492 patients aged 60 years and older who did not have an identified cause in the ED for their presenting complaint of syncope were included in the propensity score analysis resulting in a sample size of 1,064 with 532 patients in each of the discharged and hospitalized groups. There was no significant difference in risk of 30-day post-ED serious adverse events between the hospitalized patients (4.89%; 95% confidence interval, 3.06%-6.72%) and discharged patients (2.82%; 95% CI, 1.41%-4.23%; risk difference 2.07%; 95% CI, –0.24% to 4.38%). There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality post–ED visit.

These results show no clinical benefit in hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope after ED evaluation suggesting that it would be reasonable to proceed with outpatient management and evaluation of these patients.

Bottom line: Consider discharging older patients home from the ED who do not have high risk factors and no identified cause of their syncope.

Citation: Probst MA et al. Clinical benefit of hospitalization for older adults with unexplained syncope: A propensity-matched analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;74(2):260-9.

Dr. Field is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum Developing After Chest Tube Placement in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

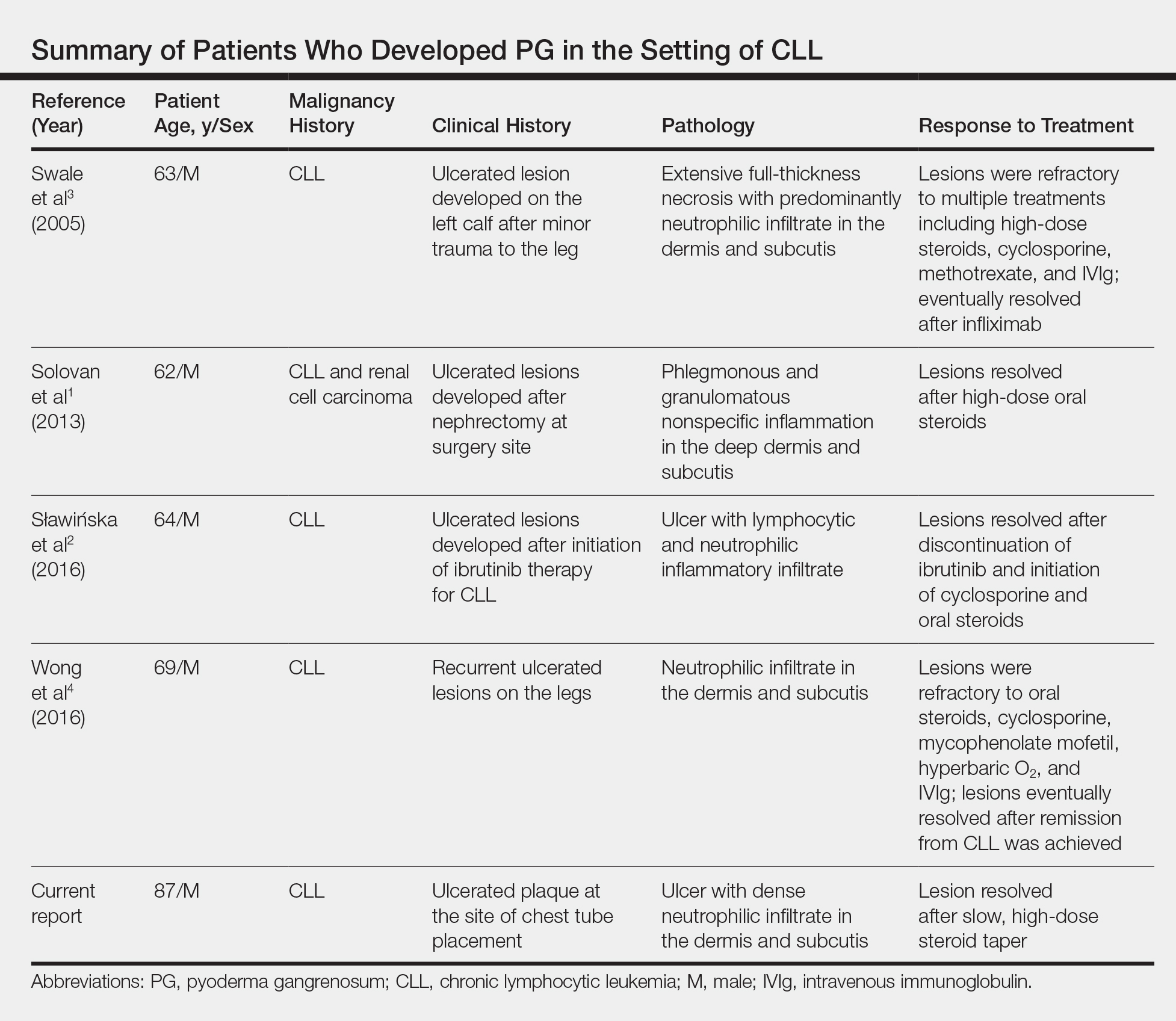

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

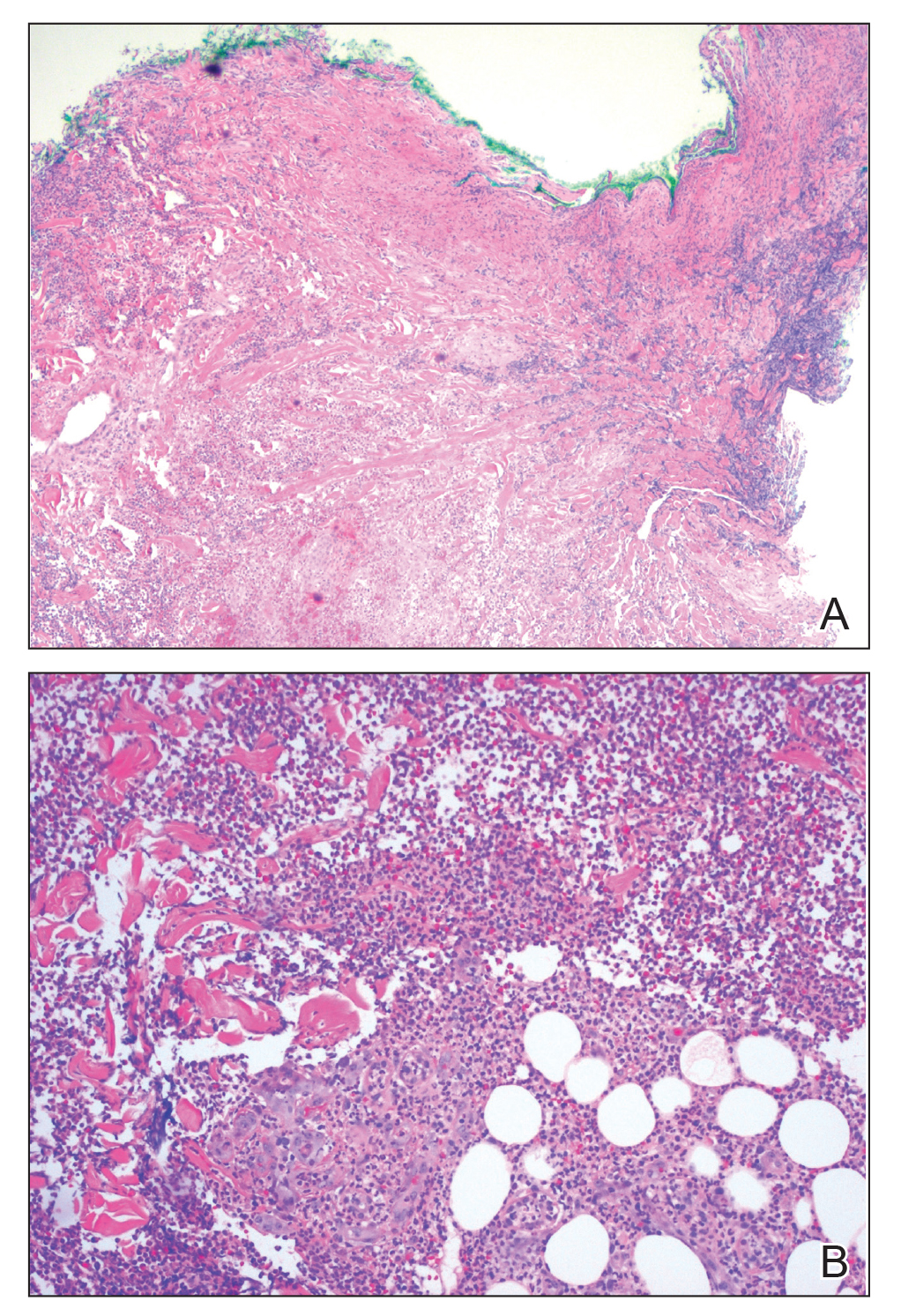

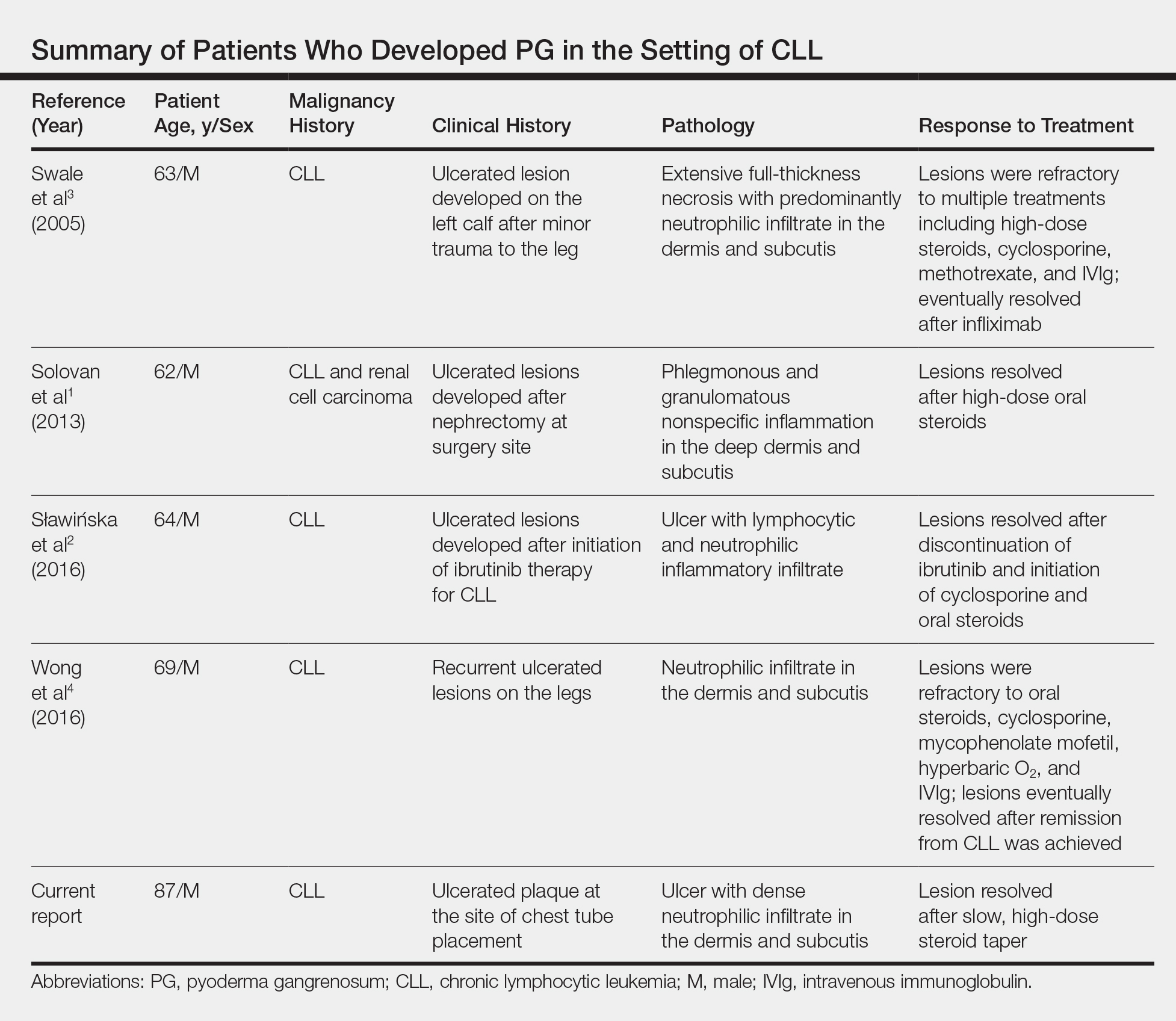

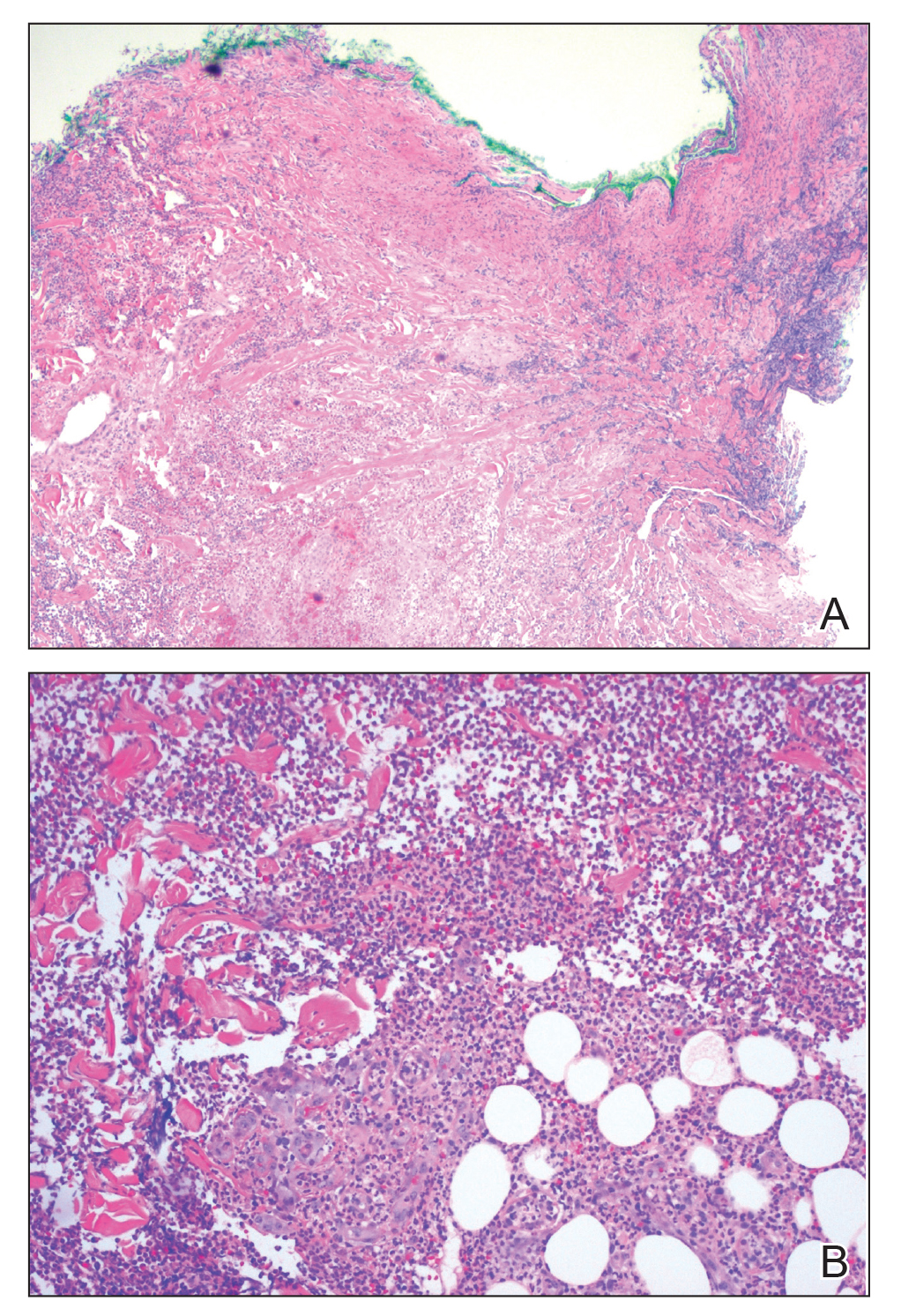

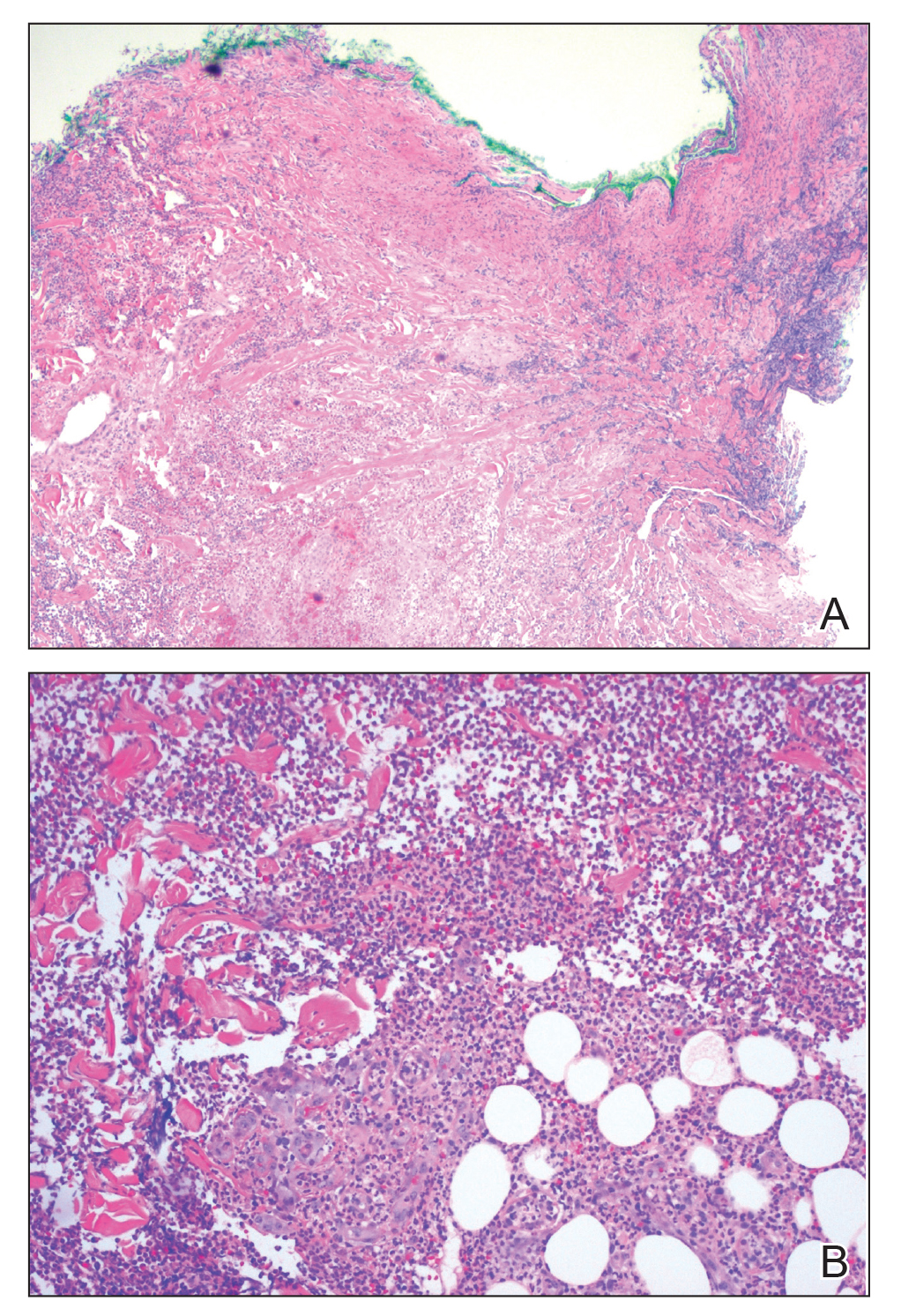

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

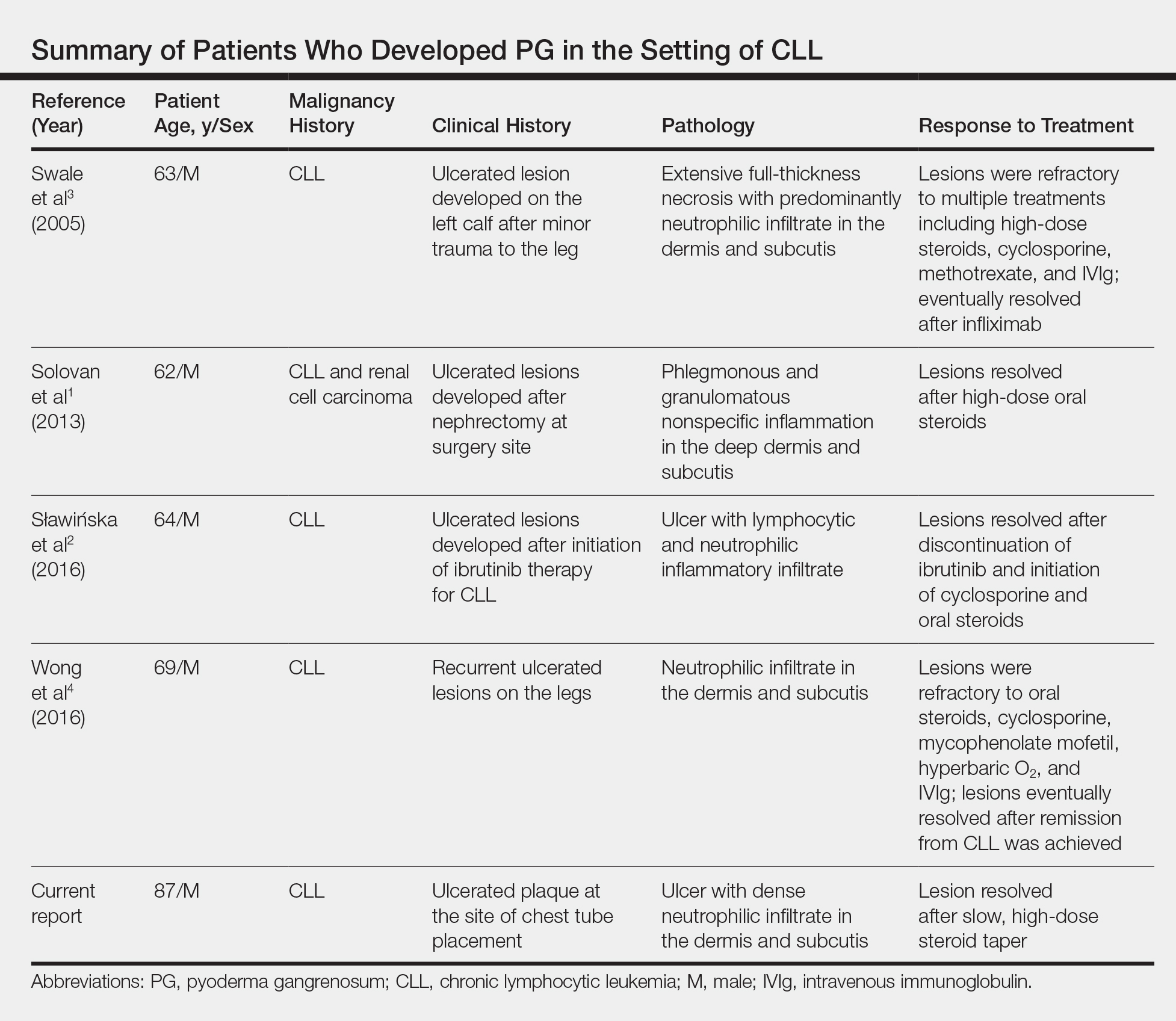

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

Practice Points

- The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process.

- Surgical debridement would further exacerbate PG, making proper diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis of paramount importance to avoid treatments that could have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

- Cutaneous findings are seen in one-quarter of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum is commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease but also can be seen in many hematologic malignancies. Physicians should be aware of this association to ensure these patients are diagnosed properly.