User login

The VA My Life My Story Project: Keeping Medical Students and Veterans Socially Connected While Physically Distanced

Narrative competence is the ability to acquire, interpret, and act on the stories of others.1 Developing this skill through guided medical storytelling can improve health care practitioners’ (HCPs) sense of empathy and satisfaction with their work.2 Narrative medicine experiences for medical students can foster a deeper understanding of their patients beyond illness-associated identities.3

Within narrative medicine, the “life story” is a specific technique that allows patients to share experiences through open-ended interviews that are entered into the health record.4,5 By sharing life stories, patients control a narrative encompassing more than their illness and can reinforce a sense of purpose in their lives.6 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) My Life My Story (MLMS) program gives veterans the opportunity to share their narrative with staff and volunteer interviewers. MLMS is well received by veterans, has durable positive effects for HCPs who read the stories, and has been used as a tool to teach patient-centered care to medical trainees.7-9

We created a narrative medicine curriculum at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) in which medical students interviewed veterans for the MLMS program. Medical students initially collected life stories through in-person conversation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, physical distancing regulations limited direct patient interaction for students and prompted a switch to phone and video interviews. This shift paralleled the widespread adoption of telehealth, which will persist beyond the pandemic and require teachers and learners to develop competency in forming personal connections with patients through videoconferencing.10,11

There are no published studies describing how to guide medical students (or other historians) in generating life stories without in-person patient contact. This article details the design of a medical student curriculum incorporating MLMS and the transition to remote interaction between instructors, students, and veterans during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

MLMS Program Origins

The MLMS project began at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2013 with staff and volunteer interviewers and has expanded to more than 60 VA facilities.7 In January 2020, we initiated a narrative medicine curriculum incorporating MLMS at the SFVAMC as a required component of a third-year internal medicine clerkship for medical students at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). Fifty-four medical students in 10 cohorts participated in the curriculum in 2020. The primary program objectives were for medical students to develop skills for eliciting and recording a life story and to appreciate the impact of this activity on a veteran’s experience of receiving health care. Secondary objectives were for students to understand the mission of the VA health care system and veteran demographics.

The first cohort of 6 UCSF medical students participated in MLMS during their 8-week VA clerkship. Students attended a 1-hour small group session to introduce the program and build narrative medicine skills. Preparation for this session involved listening to 2 podcast episodes introducing the VA health care system and MLMS.12,13 The session began with a short interactive discussion of veteran demographics with an emphasis on addressing assumptions students might have about the veteran population. Students were taught strategies for engaging in open-ended conversations without emphasizing illness. Each student practiced collecting a life story with a simulated patient portrayed by an instructor and received feedback from classmates and instructors.

Over the following weeks, students selected a hospitalized veteran, typically a patient they were caring for, introduced MLMS, and obtained verbal consent to participate. They conducted a 60- to 90-minute interview, wrote and organized the life story, read it to the veteran, and solicited edits. Once a final version was generated, the student provided the veteran with printed copies and offered to place the story in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Near the end of their rotation, students attended a 1-hour small group session in which they shared reflections on the experience of collecting a life story, the impact of veterans’ life experiences on their health and illness, and moments when students confronted their own stereotypes and implicit biases. Students then reviewed narrative medicine skills that are generalizable to all patient interactions.

COVID-19-Related Adaptation

In March 2020, shortly after the second student cohort began, medical students were removed from the clinical setting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 8-week clerkship was converted to a 3-week remote learning rotation. The MLMS experience was preserved by converting small group sessions to videoconferences and expanding the pool of eligible patients to include veterans who students had met on prior rotations, current inpatients, and outpatients from VA primary care clinics. Students contacted veterans after an instructor had introduced MLMS to the veteran and confirmed that the veteran was interested in participating.

Students in the second and third cohorts completed a telephone-based iteration of MLMS in which interviews and life story reviews were conducted over the telephone and printed copies mailed to the veteran. For the fourth, fifth, and sixth cohorts, MLMS was transitioned to a video-based program with inpatients. Instructors collaborated with a volunteer group supplying tablet devices to inpatients to make video calls to their families during the pandemic.14 Clerkship students coordinated with that volunteer group to interview veterans and review their stories through the tablet devices.

From July to December 2020 medical students returned to 4-week on-site clinical rotations at the SFVAMC. The program returned to the original format for cohorts 7 to 10, with students attending in-person small group sessions and conducting in-person interviews with inpatients.

Curriculum Evaluation

Students completed surveys in the week after the curriculum concluded. Survey completion was voluntary, anonymous, and had no bearing on their evaluation or grade (pass/fail only). Likert scale questions (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree) were used to assess the program (eAppendix 1). One-way analysis of variance testing was used to compare means stratified by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video). Surveys also included free-response questions asking students to highlight aspects of the program they valued or would change; responses were summarized by theme. This program evaluation was deemed exempt from review by the UCSF Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board.

Sixty-two veteran stories were collected by 54 participating students (one student was unable to complete an interview, while several students completed multiple interviews). Fifty-four (87%) veterans requested their stories be entered into the medical record.

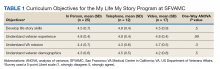

All 54 students completed the survey. Students reported that the MLMS curriculum helped them develop new skills for eliciting and recording a life story (mean [SD] 4.5 [0.7]). Most students strongly agreed that MLMS helped them understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care, with a mean (SD) score of 4.8 (0.4). After completing MLMS, students also reported a better understanding of the mission of the VA and veteran demographics with a mean (SD) score of 4.4 (0.7) and 4.3 (0.7), respectively. Stratification of survey responses by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video) revealed no statistically significant differences in evaluations (Table 1).

Fifty-two (96%) students provided responses to free-response survey questions. Students reported that they valued shifting the focus of an interview from medical history to rapport-building and patient engagement, having protected time to focus on the humanistic aspect of doctoring, and redefining healing as a process that occurs in the greater context of a patient’s life. One student reported, “We talk so much about seeing the person instead of the disease, but this is the first time that I really felt like I had the opportunity to wholeheartedly commit myself to that. It was an incredible opportunity and something I wish all medical trainees would have the chance to do.” Another student, after participating in the video version of the project, reported, “I found so much comfort in the time that I just sat and listened to another person’s story firsthand. Not only did this opportunity remind me of why I wanted to work in medicine, but also why I wanted to work with and for other people.” Thirty-three (61%) students provided constructive feedback in response to a free-response question soliciting suggestions for improvement, which guided iterative programmatic changes. For example, 3 students who completed the telephone iteration of MLMS felt that patient engagement suffered due to the lack of nonverbal cues and body language that can enhance the bond between storyteller and interviewer. This prompted a switch to video interviews beginning with the fourth cohort.

The second small group session provided space for students to reflect on their experience. During this session, students frequently referenced the unique connections they developed with veterans. Several students described feeling refreshed by these connections and that MLMS helped them recall their original commitment to become physicians. Students also discovered that the events veterans included in their stories often echoed current societal issues. For example, as social unrest and protests related to racial injustice occurred in the summer of 2020, veterans’ life stories more frequently incorporated examples of prejudice or inequities in the justice system. As the use of force by police moved to the forefront of political discourse, life stories more often included veterans’ experiences working as military and nonmilitary law enforcement. In identifying these common themes, students reported a greater appreciation of the impact of society on patients’ overall health and well-being.

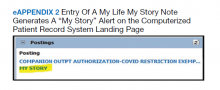

Stories were recorded as CPRS notes titled “My Story,” and completion of a note generated a “My Story” alert on the CPRS landing page at the SFVAMC (eAppendix 2). Physicians and nurses who have discovered the notes reported that patient care has been enhanced by the contextualization provided by a life story. HCPs now frequently contact MLMS instructors inquiring whether students are available to collect life stories for their patients. One physician wrote, “I learned so much from what you documented—much more than I could appreciate in my clinic visits with him. His voice comes shining through. Thank you for highlighting the humanism of medicine in the medical record.” Another physician noted, “The story captured his voice so well. I reread it over the weekend after I got the news that he died, and it helped me celebrate his life. Please tell your students how much their work means to patients, families, and the providers who care for them.”

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that a narrative medicine curriculum can help medicine clerkship students develop narrative competence through patient storytelling with a focus on a patient’s illness narrative.15 The VA MLMS program extends the patient narrative beyond health care–related experiences and encompasses their broader life story. This article adds to the MLMS and narrative medicine literature by demonstrating that the efficacy of teaching patient-centered care to medical trainees through direct interviews can be maintained in remote formats.9 The article also provides guidance for MLMS programs that wish to conduct remote veteran interviews.

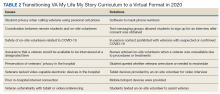

The widespread adoption of telemedicine will require trainees to develop communication skills to establish therapeutic relationships with patients both face-to-face and through videoconferencing. In order to promote this important skill across varying levels of physical distancing, narrative medicine programs should be adaptable to a virtual learning environment. As we redesigned MLMS for the remote setting, we learned several key lessons that can guide similar curricular and programmatic innovations at other institutions. For example, videoconferencing created stronger connections between the students and veterans than telephone calls. However, tablet-based video interviews also introduced many technological challenges and required on-site personnel (nurses and volunteers) to connect students, veterans, and technology. Solutions for technology and communication challenges related to the basic personnel and infrastructure needed to start and maintain a remote MLMS program are outlined in Table 2.

We are now using this experience to guide the expansion of life story curricula to other affiliated clerkship sites and other medical student rotations. We also are expanding the interviewer pool beyond medical students to VA staff and volunteers, some of whom may be restricted from direct patient contact in the future but who could participate through the remote protocols that we developed.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the participation of trainees from a single institution and a lack of assessment of the impact of MLMS on veterans. Future research could assess whether life story skills and practices are maintained after the medicine clerkship. In addition, future studies could examine veterans’ perspectives through interviews with qualitative analysis to learn how MLMS affected their experience of receiving health care.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a remote-capable life story curriculum for medical students. Shifting to a virtual MLMS curriculum requires protocols and people to link interviewers, veterans, and technology. Training for in-person interactions while being prepared for remote interviewing is essential to ensure that the MLMS experience remains available to interviewers and veterans who otherwise may never have the chance to connect. The restrictions and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic will fade, but using MLMS to virtually connect patients, providers, and students will remain an important capability and opportunity as health care shifts to more virtual interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Levine, MD, for her assistance coordinating video interviews; Thor Ringler, MS, MFA, for his assistance with manuscript review; and the veterans of the San Francisco VA Health Care System for sharing their stories.

1. Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

2. Milota MM, van Thiel GJMW, van Delden JJM. Narrative medicine as a medical education tool: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2019;41(7):802-810. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1584274

3. Garrison D, Lyness JM, Frank JB, Epstein RM. Qualitative analysis of medical student impressions of a narrative exercise in the third-year psychiatry clerkship. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):85-89. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff7a63

4. Divinsky M. Stories for life: introduction to narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(2):203-211.

5. McAdams DP, McLean KC. Narrative identity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(3):233-238. doi:10.1177 /0963721413475622

6. Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:8. Published 2015 Mar 21. doi:10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1

7. Ringler T, Ahearn EP, Wise M, Lee ER, Krahn D. Using life stories to connect veterans and providers. Fed Pract. 2015;32(6):8-14.

8. Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The My Life, My Story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

9. Nathan S, Fiore LL, Saunders S, et al. My Life, My Story: Teaching patient centered care competencies for older adults through life story work [published online ahead of print, 2019 Sep 9] [published correction appears in Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019 Oct 15;:1]. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;1-14. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1665038

10. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):859. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30424-4

11. Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January-March 2020 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Nov 13;69(45):1711]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(43):1595-1599. Published 2020 Oct 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

12. Caputo LV. Across the Street. The VA philosophy: with Dr. Goldberg. July 14, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://soundcloud.com/user-911014559/the-va-philosophy-with-dr-goldberg-1

13. Sable-Smith B. Storytelling helps hospital staff discover the person within the patient. NPR. Published June 8, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/08/729351842/storytelling-helps-hospital-staff-discover-the-person-within-the-patient

14. Ganeshan S, Hsiang E, Peng T, et al. Enabling patient communication for hospitalised patients during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Innov. 2021;7(2):316-320. doi:10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000636

15. Chretien KC, Swenson R, Yoon B, et al. Tell me your story: a pilot narrative medicine curriculum during the medicine clerkship. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1025-1028. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3211-z

Narrative competence is the ability to acquire, interpret, and act on the stories of others.1 Developing this skill through guided medical storytelling can improve health care practitioners’ (HCPs) sense of empathy and satisfaction with their work.2 Narrative medicine experiences for medical students can foster a deeper understanding of their patients beyond illness-associated identities.3

Within narrative medicine, the “life story” is a specific technique that allows patients to share experiences through open-ended interviews that are entered into the health record.4,5 By sharing life stories, patients control a narrative encompassing more than their illness and can reinforce a sense of purpose in their lives.6 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) My Life My Story (MLMS) program gives veterans the opportunity to share their narrative with staff and volunteer interviewers. MLMS is well received by veterans, has durable positive effects for HCPs who read the stories, and has been used as a tool to teach patient-centered care to medical trainees.7-9

We created a narrative medicine curriculum at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) in which medical students interviewed veterans for the MLMS program. Medical students initially collected life stories through in-person conversation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, physical distancing regulations limited direct patient interaction for students and prompted a switch to phone and video interviews. This shift paralleled the widespread adoption of telehealth, which will persist beyond the pandemic and require teachers and learners to develop competency in forming personal connections with patients through videoconferencing.10,11

There are no published studies describing how to guide medical students (or other historians) in generating life stories without in-person patient contact. This article details the design of a medical student curriculum incorporating MLMS and the transition to remote interaction between instructors, students, and veterans during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

MLMS Program Origins

The MLMS project began at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2013 with staff and volunteer interviewers and has expanded to more than 60 VA facilities.7 In January 2020, we initiated a narrative medicine curriculum incorporating MLMS at the SFVAMC as a required component of a third-year internal medicine clerkship for medical students at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). Fifty-four medical students in 10 cohorts participated in the curriculum in 2020. The primary program objectives were for medical students to develop skills for eliciting and recording a life story and to appreciate the impact of this activity on a veteran’s experience of receiving health care. Secondary objectives were for students to understand the mission of the VA health care system and veteran demographics.

The first cohort of 6 UCSF medical students participated in MLMS during their 8-week VA clerkship. Students attended a 1-hour small group session to introduce the program and build narrative medicine skills. Preparation for this session involved listening to 2 podcast episodes introducing the VA health care system and MLMS.12,13 The session began with a short interactive discussion of veteran demographics with an emphasis on addressing assumptions students might have about the veteran population. Students were taught strategies for engaging in open-ended conversations without emphasizing illness. Each student practiced collecting a life story with a simulated patient portrayed by an instructor and received feedback from classmates and instructors.

Over the following weeks, students selected a hospitalized veteran, typically a patient they were caring for, introduced MLMS, and obtained verbal consent to participate. They conducted a 60- to 90-minute interview, wrote and organized the life story, read it to the veteran, and solicited edits. Once a final version was generated, the student provided the veteran with printed copies and offered to place the story in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Near the end of their rotation, students attended a 1-hour small group session in which they shared reflections on the experience of collecting a life story, the impact of veterans’ life experiences on their health and illness, and moments when students confronted their own stereotypes and implicit biases. Students then reviewed narrative medicine skills that are generalizable to all patient interactions.

COVID-19-Related Adaptation

In March 2020, shortly after the second student cohort began, medical students were removed from the clinical setting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 8-week clerkship was converted to a 3-week remote learning rotation. The MLMS experience was preserved by converting small group sessions to videoconferences and expanding the pool of eligible patients to include veterans who students had met on prior rotations, current inpatients, and outpatients from VA primary care clinics. Students contacted veterans after an instructor had introduced MLMS to the veteran and confirmed that the veteran was interested in participating.

Students in the second and third cohorts completed a telephone-based iteration of MLMS in which interviews and life story reviews were conducted over the telephone and printed copies mailed to the veteran. For the fourth, fifth, and sixth cohorts, MLMS was transitioned to a video-based program with inpatients. Instructors collaborated with a volunteer group supplying tablet devices to inpatients to make video calls to their families during the pandemic.14 Clerkship students coordinated with that volunteer group to interview veterans and review their stories through the tablet devices.

From July to December 2020 medical students returned to 4-week on-site clinical rotations at the SFVAMC. The program returned to the original format for cohorts 7 to 10, with students attending in-person small group sessions and conducting in-person interviews with inpatients.

Curriculum Evaluation

Students completed surveys in the week after the curriculum concluded. Survey completion was voluntary, anonymous, and had no bearing on their evaluation or grade (pass/fail only). Likert scale questions (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree) were used to assess the program (eAppendix 1). One-way analysis of variance testing was used to compare means stratified by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video). Surveys also included free-response questions asking students to highlight aspects of the program they valued or would change; responses were summarized by theme. This program evaluation was deemed exempt from review by the UCSF Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board.

Sixty-two veteran stories were collected by 54 participating students (one student was unable to complete an interview, while several students completed multiple interviews). Fifty-four (87%) veterans requested their stories be entered into the medical record.

All 54 students completed the survey. Students reported that the MLMS curriculum helped them develop new skills for eliciting and recording a life story (mean [SD] 4.5 [0.7]). Most students strongly agreed that MLMS helped them understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care, with a mean (SD) score of 4.8 (0.4). After completing MLMS, students also reported a better understanding of the mission of the VA and veteran demographics with a mean (SD) score of 4.4 (0.7) and 4.3 (0.7), respectively. Stratification of survey responses by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video) revealed no statistically significant differences in evaluations (Table 1).

Fifty-two (96%) students provided responses to free-response survey questions. Students reported that they valued shifting the focus of an interview from medical history to rapport-building and patient engagement, having protected time to focus on the humanistic aspect of doctoring, and redefining healing as a process that occurs in the greater context of a patient’s life. One student reported, “We talk so much about seeing the person instead of the disease, but this is the first time that I really felt like I had the opportunity to wholeheartedly commit myself to that. It was an incredible opportunity and something I wish all medical trainees would have the chance to do.” Another student, after participating in the video version of the project, reported, “I found so much comfort in the time that I just sat and listened to another person’s story firsthand. Not only did this opportunity remind me of why I wanted to work in medicine, but also why I wanted to work with and for other people.” Thirty-three (61%) students provided constructive feedback in response to a free-response question soliciting suggestions for improvement, which guided iterative programmatic changes. For example, 3 students who completed the telephone iteration of MLMS felt that patient engagement suffered due to the lack of nonverbal cues and body language that can enhance the bond between storyteller and interviewer. This prompted a switch to video interviews beginning with the fourth cohort.

The second small group session provided space for students to reflect on their experience. During this session, students frequently referenced the unique connections they developed with veterans. Several students described feeling refreshed by these connections and that MLMS helped them recall their original commitment to become physicians. Students also discovered that the events veterans included in their stories often echoed current societal issues. For example, as social unrest and protests related to racial injustice occurred in the summer of 2020, veterans’ life stories more frequently incorporated examples of prejudice or inequities in the justice system. As the use of force by police moved to the forefront of political discourse, life stories more often included veterans’ experiences working as military and nonmilitary law enforcement. In identifying these common themes, students reported a greater appreciation of the impact of society on patients’ overall health and well-being.

Stories were recorded as CPRS notes titled “My Story,” and completion of a note generated a “My Story” alert on the CPRS landing page at the SFVAMC (eAppendix 2). Physicians and nurses who have discovered the notes reported that patient care has been enhanced by the contextualization provided by a life story. HCPs now frequently contact MLMS instructors inquiring whether students are available to collect life stories for their patients. One physician wrote, “I learned so much from what you documented—much more than I could appreciate in my clinic visits with him. His voice comes shining through. Thank you for highlighting the humanism of medicine in the medical record.” Another physician noted, “The story captured his voice so well. I reread it over the weekend after I got the news that he died, and it helped me celebrate his life. Please tell your students how much their work means to patients, families, and the providers who care for them.”

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that a narrative medicine curriculum can help medicine clerkship students develop narrative competence through patient storytelling with a focus on a patient’s illness narrative.15 The VA MLMS program extends the patient narrative beyond health care–related experiences and encompasses their broader life story. This article adds to the MLMS and narrative medicine literature by demonstrating that the efficacy of teaching patient-centered care to medical trainees through direct interviews can be maintained in remote formats.9 The article also provides guidance for MLMS programs that wish to conduct remote veteran interviews.

The widespread adoption of telemedicine will require trainees to develop communication skills to establish therapeutic relationships with patients both face-to-face and through videoconferencing. In order to promote this important skill across varying levels of physical distancing, narrative medicine programs should be adaptable to a virtual learning environment. As we redesigned MLMS for the remote setting, we learned several key lessons that can guide similar curricular and programmatic innovations at other institutions. For example, videoconferencing created stronger connections between the students and veterans than telephone calls. However, tablet-based video interviews also introduced many technological challenges and required on-site personnel (nurses and volunteers) to connect students, veterans, and technology. Solutions for technology and communication challenges related to the basic personnel and infrastructure needed to start and maintain a remote MLMS program are outlined in Table 2.

We are now using this experience to guide the expansion of life story curricula to other affiliated clerkship sites and other medical student rotations. We also are expanding the interviewer pool beyond medical students to VA staff and volunteers, some of whom may be restricted from direct patient contact in the future but who could participate through the remote protocols that we developed.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the participation of trainees from a single institution and a lack of assessment of the impact of MLMS on veterans. Future research could assess whether life story skills and practices are maintained after the medicine clerkship. In addition, future studies could examine veterans’ perspectives through interviews with qualitative analysis to learn how MLMS affected their experience of receiving health care.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a remote-capable life story curriculum for medical students. Shifting to a virtual MLMS curriculum requires protocols and people to link interviewers, veterans, and technology. Training for in-person interactions while being prepared for remote interviewing is essential to ensure that the MLMS experience remains available to interviewers and veterans who otherwise may never have the chance to connect. The restrictions and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic will fade, but using MLMS to virtually connect patients, providers, and students will remain an important capability and opportunity as health care shifts to more virtual interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Levine, MD, for her assistance coordinating video interviews; Thor Ringler, MS, MFA, for his assistance with manuscript review; and the veterans of the San Francisco VA Health Care System for sharing their stories.

Narrative competence is the ability to acquire, interpret, and act on the stories of others.1 Developing this skill through guided medical storytelling can improve health care practitioners’ (HCPs) sense of empathy and satisfaction with their work.2 Narrative medicine experiences for medical students can foster a deeper understanding of their patients beyond illness-associated identities.3

Within narrative medicine, the “life story” is a specific technique that allows patients to share experiences through open-ended interviews that are entered into the health record.4,5 By sharing life stories, patients control a narrative encompassing more than their illness and can reinforce a sense of purpose in their lives.6 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) My Life My Story (MLMS) program gives veterans the opportunity to share their narrative with staff and volunteer interviewers. MLMS is well received by veterans, has durable positive effects for HCPs who read the stories, and has been used as a tool to teach patient-centered care to medical trainees.7-9

We created a narrative medicine curriculum at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) in which medical students interviewed veterans for the MLMS program. Medical students initially collected life stories through in-person conversation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, physical distancing regulations limited direct patient interaction for students and prompted a switch to phone and video interviews. This shift paralleled the widespread adoption of telehealth, which will persist beyond the pandemic and require teachers and learners to develop competency in forming personal connections with patients through videoconferencing.10,11

There are no published studies describing how to guide medical students (or other historians) in generating life stories without in-person patient contact. This article details the design of a medical student curriculum incorporating MLMS and the transition to remote interaction between instructors, students, and veterans during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

MLMS Program Origins

The MLMS project began at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2013 with staff and volunteer interviewers and has expanded to more than 60 VA facilities.7 In January 2020, we initiated a narrative medicine curriculum incorporating MLMS at the SFVAMC as a required component of a third-year internal medicine clerkship for medical students at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). Fifty-four medical students in 10 cohorts participated in the curriculum in 2020. The primary program objectives were for medical students to develop skills for eliciting and recording a life story and to appreciate the impact of this activity on a veteran’s experience of receiving health care. Secondary objectives were for students to understand the mission of the VA health care system and veteran demographics.

The first cohort of 6 UCSF medical students participated in MLMS during their 8-week VA clerkship. Students attended a 1-hour small group session to introduce the program and build narrative medicine skills. Preparation for this session involved listening to 2 podcast episodes introducing the VA health care system and MLMS.12,13 The session began with a short interactive discussion of veteran demographics with an emphasis on addressing assumptions students might have about the veteran population. Students were taught strategies for engaging in open-ended conversations without emphasizing illness. Each student practiced collecting a life story with a simulated patient portrayed by an instructor and received feedback from classmates and instructors.

Over the following weeks, students selected a hospitalized veteran, typically a patient they were caring for, introduced MLMS, and obtained verbal consent to participate. They conducted a 60- to 90-minute interview, wrote and organized the life story, read it to the veteran, and solicited edits. Once a final version was generated, the student provided the veteran with printed copies and offered to place the story in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Near the end of their rotation, students attended a 1-hour small group session in which they shared reflections on the experience of collecting a life story, the impact of veterans’ life experiences on their health and illness, and moments when students confronted their own stereotypes and implicit biases. Students then reviewed narrative medicine skills that are generalizable to all patient interactions.

COVID-19-Related Adaptation

In March 2020, shortly after the second student cohort began, medical students were removed from the clinical setting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 8-week clerkship was converted to a 3-week remote learning rotation. The MLMS experience was preserved by converting small group sessions to videoconferences and expanding the pool of eligible patients to include veterans who students had met on prior rotations, current inpatients, and outpatients from VA primary care clinics. Students contacted veterans after an instructor had introduced MLMS to the veteran and confirmed that the veteran was interested in participating.

Students in the second and third cohorts completed a telephone-based iteration of MLMS in which interviews and life story reviews were conducted over the telephone and printed copies mailed to the veteran. For the fourth, fifth, and sixth cohorts, MLMS was transitioned to a video-based program with inpatients. Instructors collaborated with a volunteer group supplying tablet devices to inpatients to make video calls to their families during the pandemic.14 Clerkship students coordinated with that volunteer group to interview veterans and review their stories through the tablet devices.

From July to December 2020 medical students returned to 4-week on-site clinical rotations at the SFVAMC. The program returned to the original format for cohorts 7 to 10, with students attending in-person small group sessions and conducting in-person interviews with inpatients.

Curriculum Evaluation

Students completed surveys in the week after the curriculum concluded. Survey completion was voluntary, anonymous, and had no bearing on their evaluation or grade (pass/fail only). Likert scale questions (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree) were used to assess the program (eAppendix 1). One-way analysis of variance testing was used to compare means stratified by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video). Surveys also included free-response questions asking students to highlight aspects of the program they valued or would change; responses were summarized by theme. This program evaluation was deemed exempt from review by the UCSF Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board.

Sixty-two veteran stories were collected by 54 participating students (one student was unable to complete an interview, while several students completed multiple interviews). Fifty-four (87%) veterans requested their stories be entered into the medical record.

All 54 students completed the survey. Students reported that the MLMS curriculum helped them develop new skills for eliciting and recording a life story (mean [SD] 4.5 [0.7]). Most students strongly agreed that MLMS helped them understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care, with a mean (SD) score of 4.8 (0.4). After completing MLMS, students also reported a better understanding of the mission of the VA and veteran demographics with a mean (SD) score of 4.4 (0.7) and 4.3 (0.7), respectively. Stratification of survey responses by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video) revealed no statistically significant differences in evaluations (Table 1).

Fifty-two (96%) students provided responses to free-response survey questions. Students reported that they valued shifting the focus of an interview from medical history to rapport-building and patient engagement, having protected time to focus on the humanistic aspect of doctoring, and redefining healing as a process that occurs in the greater context of a patient’s life. One student reported, “We talk so much about seeing the person instead of the disease, but this is the first time that I really felt like I had the opportunity to wholeheartedly commit myself to that. It was an incredible opportunity and something I wish all medical trainees would have the chance to do.” Another student, after participating in the video version of the project, reported, “I found so much comfort in the time that I just sat and listened to another person’s story firsthand. Not only did this opportunity remind me of why I wanted to work in medicine, but also why I wanted to work with and for other people.” Thirty-three (61%) students provided constructive feedback in response to a free-response question soliciting suggestions for improvement, which guided iterative programmatic changes. For example, 3 students who completed the telephone iteration of MLMS felt that patient engagement suffered due to the lack of nonverbal cues and body language that can enhance the bond between storyteller and interviewer. This prompted a switch to video interviews beginning with the fourth cohort.

The second small group session provided space for students to reflect on their experience. During this session, students frequently referenced the unique connections they developed with veterans. Several students described feeling refreshed by these connections and that MLMS helped them recall their original commitment to become physicians. Students also discovered that the events veterans included in their stories often echoed current societal issues. For example, as social unrest and protests related to racial injustice occurred in the summer of 2020, veterans’ life stories more frequently incorporated examples of prejudice or inequities in the justice system. As the use of force by police moved to the forefront of political discourse, life stories more often included veterans’ experiences working as military and nonmilitary law enforcement. In identifying these common themes, students reported a greater appreciation of the impact of society on patients’ overall health and well-being.

Stories were recorded as CPRS notes titled “My Story,” and completion of a note generated a “My Story” alert on the CPRS landing page at the SFVAMC (eAppendix 2). Physicians and nurses who have discovered the notes reported that patient care has been enhanced by the contextualization provided by a life story. HCPs now frequently contact MLMS instructors inquiring whether students are available to collect life stories for their patients. One physician wrote, “I learned so much from what you documented—much more than I could appreciate in my clinic visits with him. His voice comes shining through. Thank you for highlighting the humanism of medicine in the medical record.” Another physician noted, “The story captured his voice so well. I reread it over the weekend after I got the news that he died, and it helped me celebrate his life. Please tell your students how much their work means to patients, families, and the providers who care for them.”

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that a narrative medicine curriculum can help medicine clerkship students develop narrative competence through patient storytelling with a focus on a patient’s illness narrative.15 The VA MLMS program extends the patient narrative beyond health care–related experiences and encompasses their broader life story. This article adds to the MLMS and narrative medicine literature by demonstrating that the efficacy of teaching patient-centered care to medical trainees through direct interviews can be maintained in remote formats.9 The article also provides guidance for MLMS programs that wish to conduct remote veteran interviews.

The widespread adoption of telemedicine will require trainees to develop communication skills to establish therapeutic relationships with patients both face-to-face and through videoconferencing. In order to promote this important skill across varying levels of physical distancing, narrative medicine programs should be adaptable to a virtual learning environment. As we redesigned MLMS for the remote setting, we learned several key lessons that can guide similar curricular and programmatic innovations at other institutions. For example, videoconferencing created stronger connections between the students and veterans than telephone calls. However, tablet-based video interviews also introduced many technological challenges and required on-site personnel (nurses and volunteers) to connect students, veterans, and technology. Solutions for technology and communication challenges related to the basic personnel and infrastructure needed to start and maintain a remote MLMS program are outlined in Table 2.

We are now using this experience to guide the expansion of life story curricula to other affiliated clerkship sites and other medical student rotations. We also are expanding the interviewer pool beyond medical students to VA staff and volunteers, some of whom may be restricted from direct patient contact in the future but who could participate through the remote protocols that we developed.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the participation of trainees from a single institution and a lack of assessment of the impact of MLMS on veterans. Future research could assess whether life story skills and practices are maintained after the medicine clerkship. In addition, future studies could examine veterans’ perspectives through interviews with qualitative analysis to learn how MLMS affected their experience of receiving health care.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a remote-capable life story curriculum for medical students. Shifting to a virtual MLMS curriculum requires protocols and people to link interviewers, veterans, and technology. Training for in-person interactions while being prepared for remote interviewing is essential to ensure that the MLMS experience remains available to interviewers and veterans who otherwise may never have the chance to connect. The restrictions and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic will fade, but using MLMS to virtually connect patients, providers, and students will remain an important capability and opportunity as health care shifts to more virtual interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Levine, MD, for her assistance coordinating video interviews; Thor Ringler, MS, MFA, for his assistance with manuscript review; and the veterans of the San Francisco VA Health Care System for sharing their stories.

1. Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

2. Milota MM, van Thiel GJMW, van Delden JJM. Narrative medicine as a medical education tool: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2019;41(7):802-810. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1584274

3. Garrison D, Lyness JM, Frank JB, Epstein RM. Qualitative analysis of medical student impressions of a narrative exercise in the third-year psychiatry clerkship. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):85-89. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff7a63

4. Divinsky M. Stories for life: introduction to narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(2):203-211.

5. McAdams DP, McLean KC. Narrative identity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(3):233-238. doi:10.1177 /0963721413475622

6. Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:8. Published 2015 Mar 21. doi:10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1

7. Ringler T, Ahearn EP, Wise M, Lee ER, Krahn D. Using life stories to connect veterans and providers. Fed Pract. 2015;32(6):8-14.

8. Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The My Life, My Story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

9. Nathan S, Fiore LL, Saunders S, et al. My Life, My Story: Teaching patient centered care competencies for older adults through life story work [published online ahead of print, 2019 Sep 9] [published correction appears in Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019 Oct 15;:1]. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;1-14. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1665038

10. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):859. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30424-4

11. Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January-March 2020 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Nov 13;69(45):1711]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(43):1595-1599. Published 2020 Oct 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

12. Caputo LV. Across the Street. The VA philosophy: with Dr. Goldberg. July 14, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://soundcloud.com/user-911014559/the-va-philosophy-with-dr-goldberg-1

13. Sable-Smith B. Storytelling helps hospital staff discover the person within the patient. NPR. Published June 8, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/08/729351842/storytelling-helps-hospital-staff-discover-the-person-within-the-patient

14. Ganeshan S, Hsiang E, Peng T, et al. Enabling patient communication for hospitalised patients during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Innov. 2021;7(2):316-320. doi:10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000636

15. Chretien KC, Swenson R, Yoon B, et al. Tell me your story: a pilot narrative medicine curriculum during the medicine clerkship. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1025-1028. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3211-z

1. Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

2. Milota MM, van Thiel GJMW, van Delden JJM. Narrative medicine as a medical education tool: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2019;41(7):802-810. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1584274

3. Garrison D, Lyness JM, Frank JB, Epstein RM. Qualitative analysis of medical student impressions of a narrative exercise in the third-year psychiatry clerkship. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):85-89. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff7a63

4. Divinsky M. Stories for life: introduction to narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(2):203-211.

5. McAdams DP, McLean KC. Narrative identity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(3):233-238. doi:10.1177 /0963721413475622

6. Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:8. Published 2015 Mar 21. doi:10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1

7. Ringler T, Ahearn EP, Wise M, Lee ER, Krahn D. Using life stories to connect veterans and providers. Fed Pract. 2015;32(6):8-14.

8. Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The My Life, My Story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

9. Nathan S, Fiore LL, Saunders S, et al. My Life, My Story: Teaching patient centered care competencies for older adults through life story work [published online ahead of print, 2019 Sep 9] [published correction appears in Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019 Oct 15;:1]. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;1-14. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1665038

10. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):859. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30424-4

11. Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January-March 2020 [published correction appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Nov 13;69(45):1711]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(43):1595-1599. Published 2020 Oct 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

12. Caputo LV. Across the Street. The VA philosophy: with Dr. Goldberg. July 14, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://soundcloud.com/user-911014559/the-va-philosophy-with-dr-goldberg-1

13. Sable-Smith B. Storytelling helps hospital staff discover the person within the patient. NPR. Published June 8, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/08/729351842/storytelling-helps-hospital-staff-discover-the-person-within-the-patient

14. Ganeshan S, Hsiang E, Peng T, et al. Enabling patient communication for hospitalised patients during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Innov. 2021;7(2):316-320. doi:10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000636

15. Chretien KC, Swenson R, Yoon B, et al. Tell me your story: a pilot narrative medicine curriculum during the medicine clerkship. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1025-1028. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3211-z