User login

DRESS Syndrome Due to Cefdinir Mimicking Superinfected Eczema in a Pediatric Patient

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

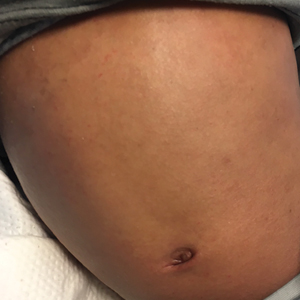

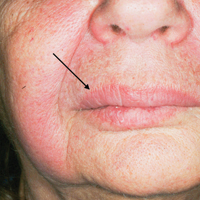

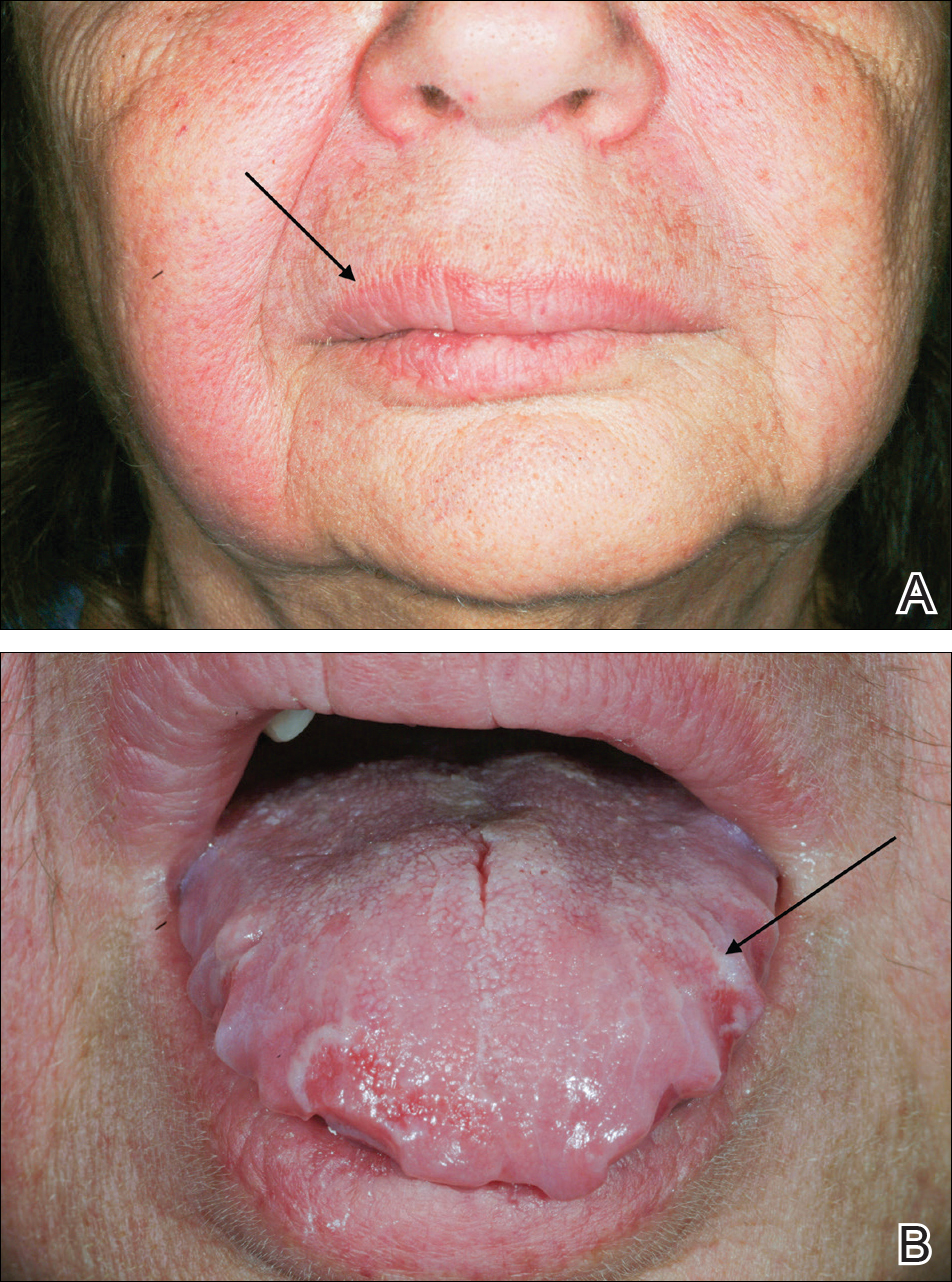

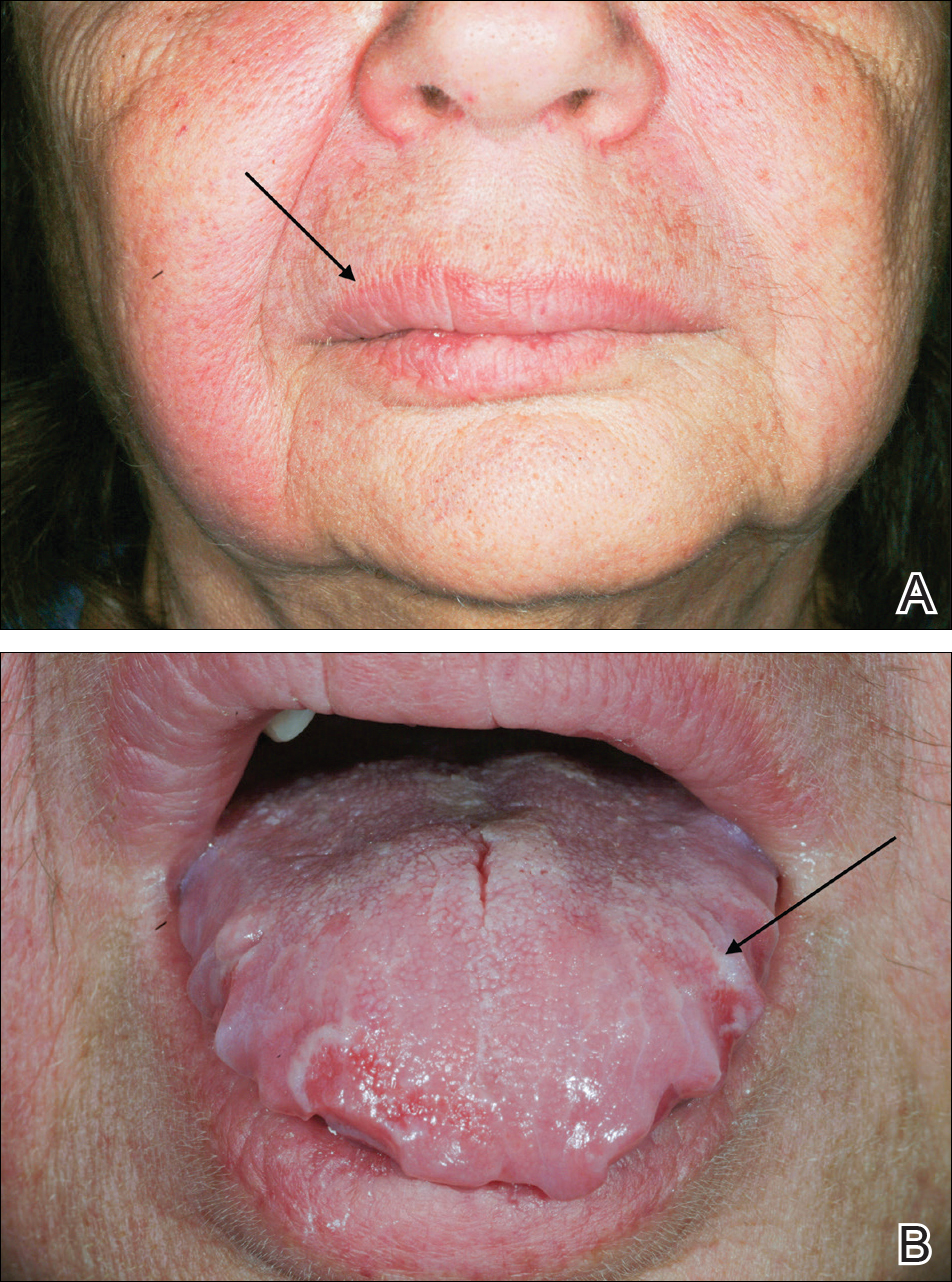

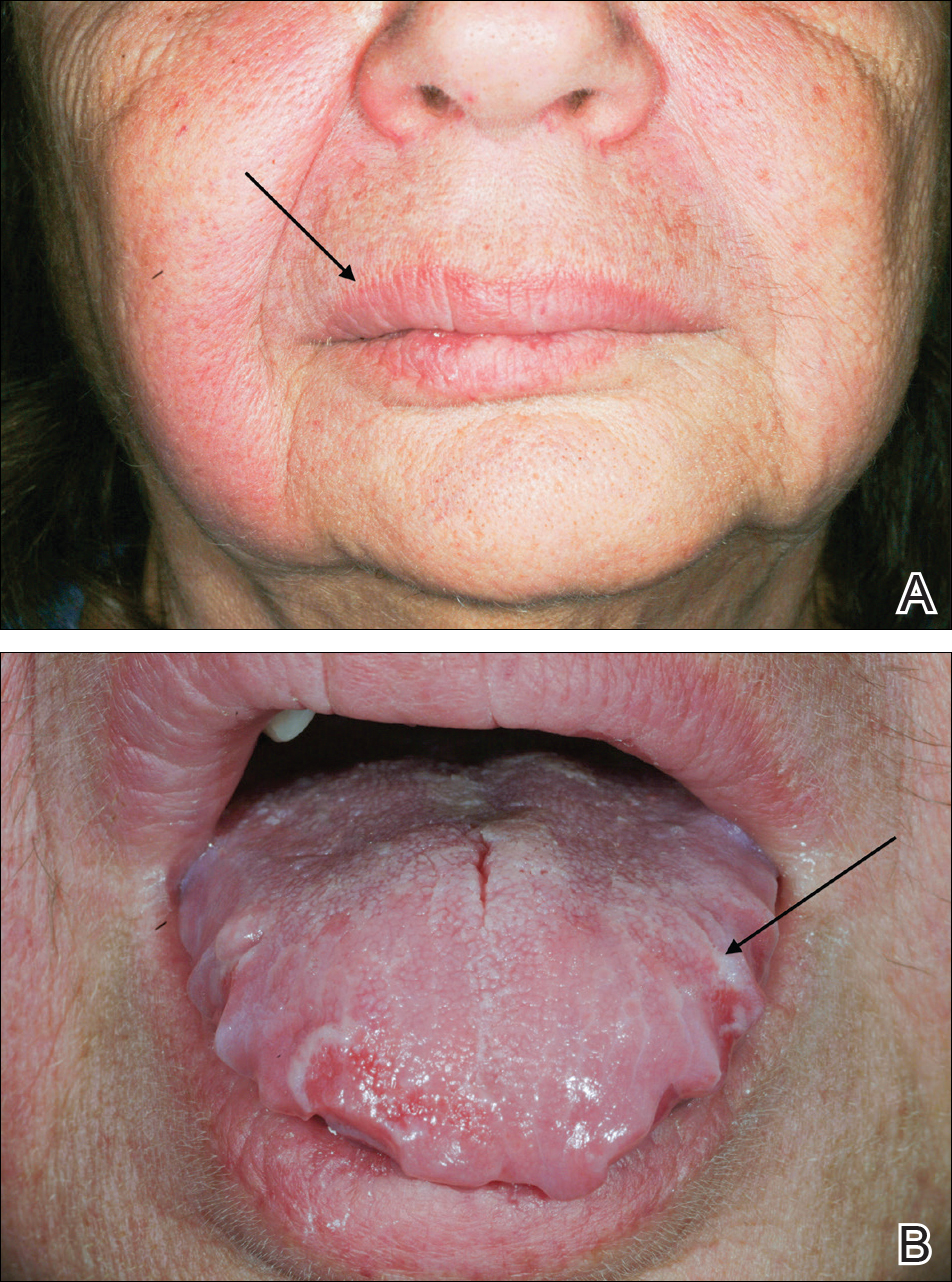

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

Practice Points

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis.

- Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality.

What Would I Tell My Intern-Year Self?

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

Physician Burnout in Dermatology

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

Tattoos: From Ancient Practice to Modern Treatment Dilemma

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

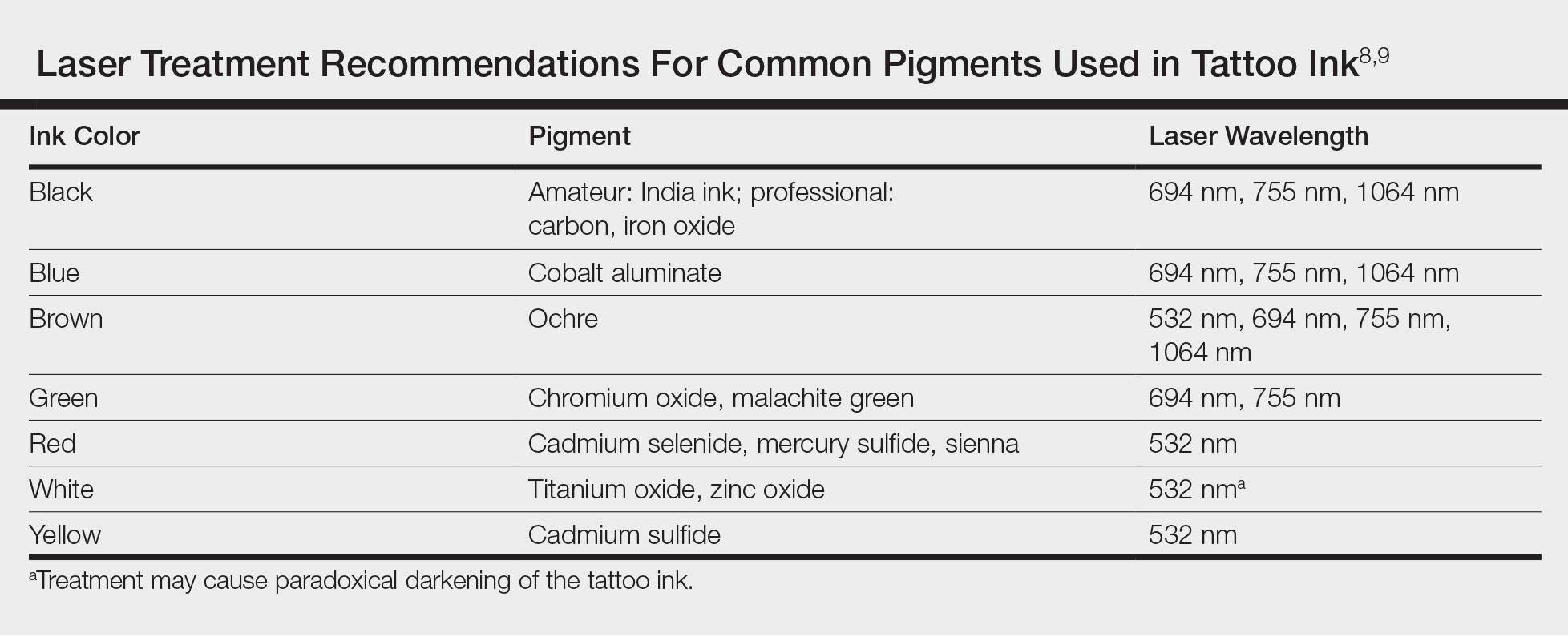

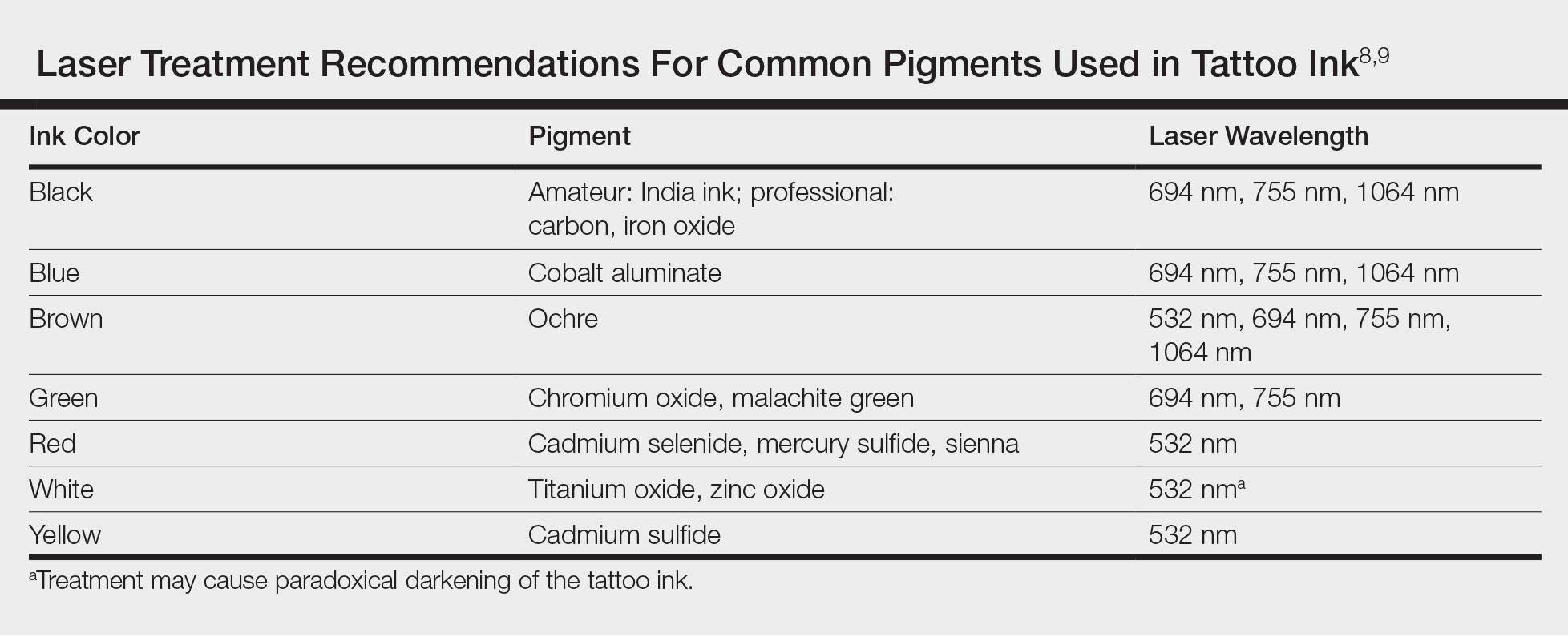

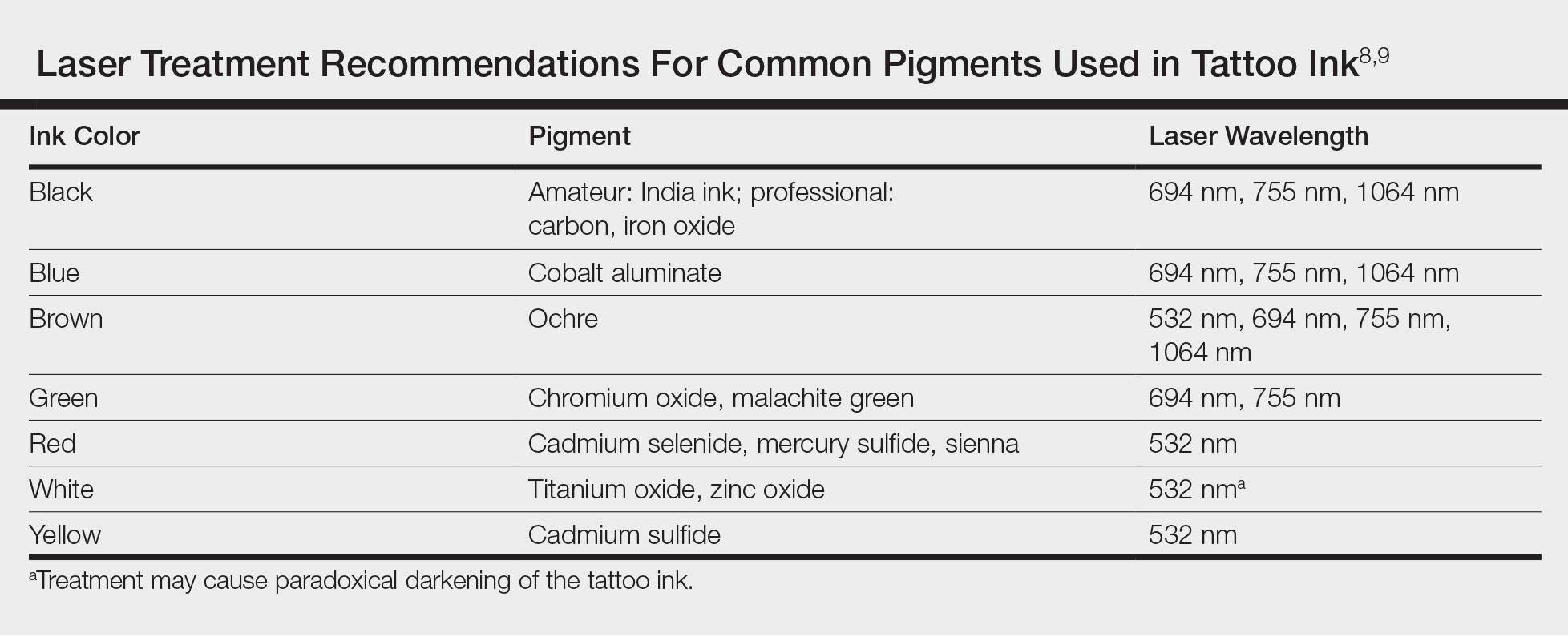

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal