User login

How Media Coverage of Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss Has Impacted Prescribing Habits

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Practice Points

- Low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions have increased due to rising attention to its efficacy and safety.

- Media outlets can have a powerful effect on prescribing habits of physicians.

- Physicians should be aware of media trends to help direct patient education.

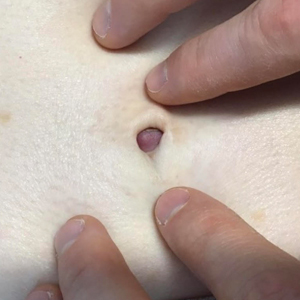

Asymptomatic Umbilical Nodule

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

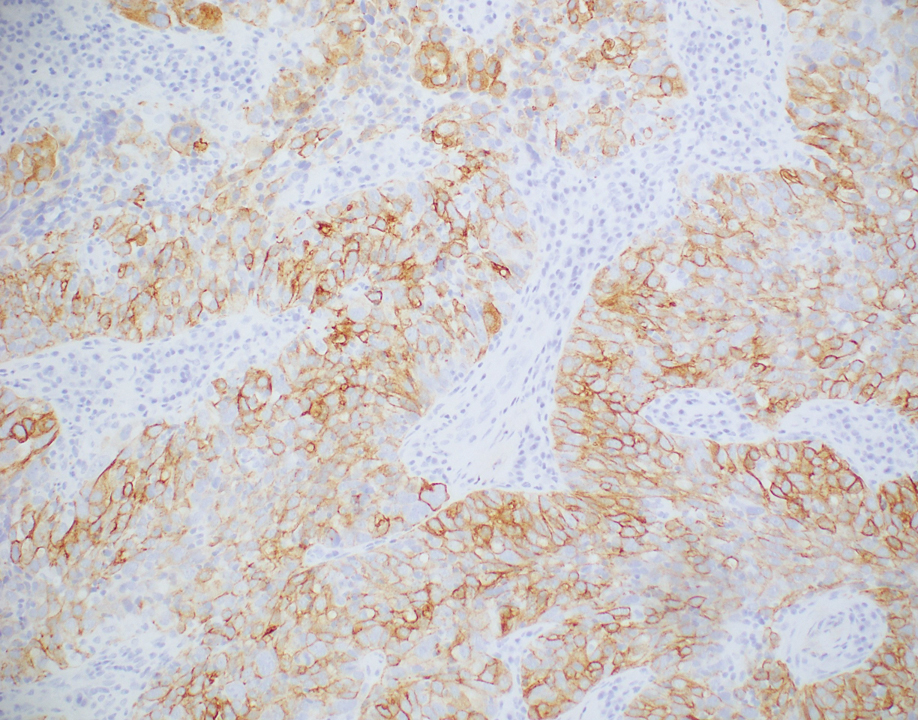

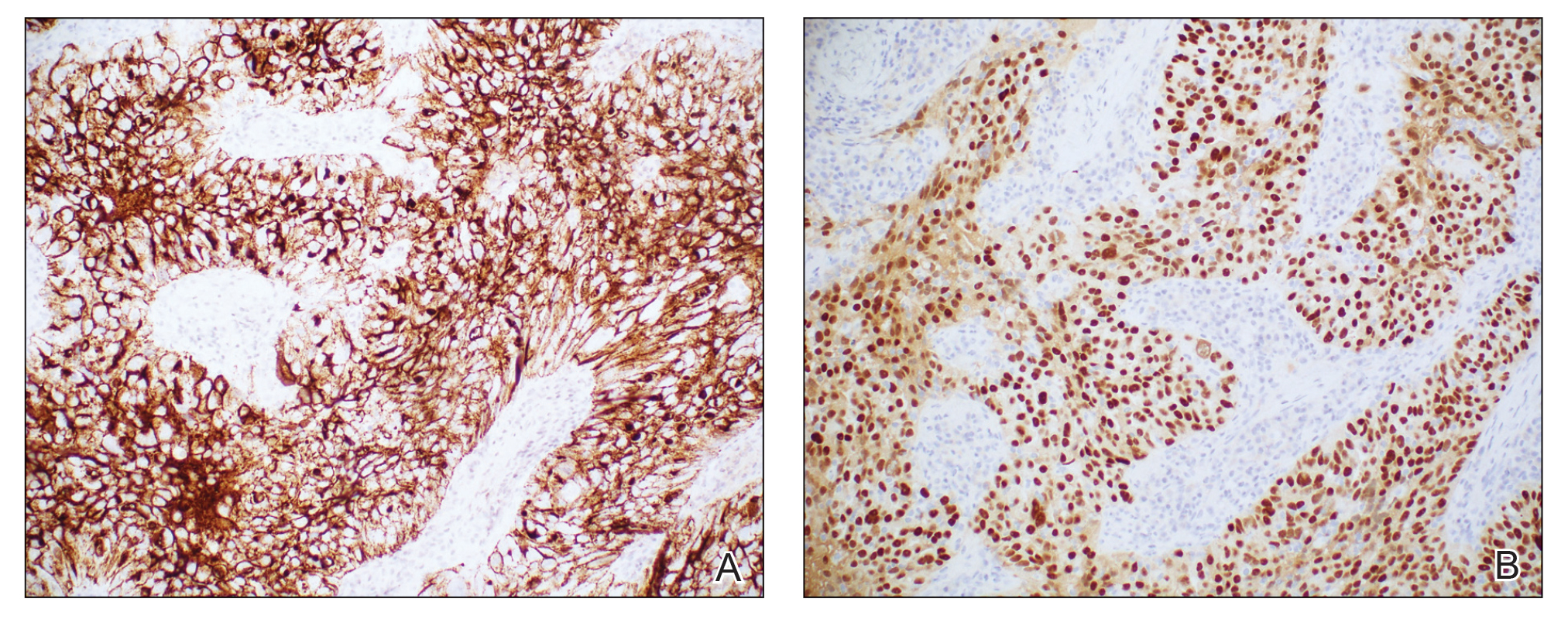

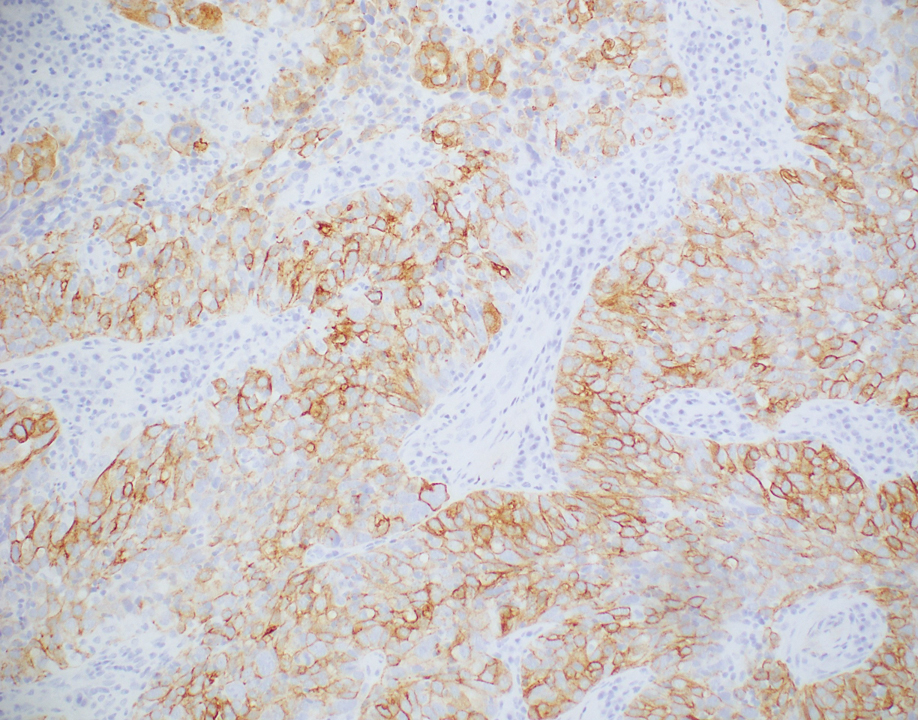

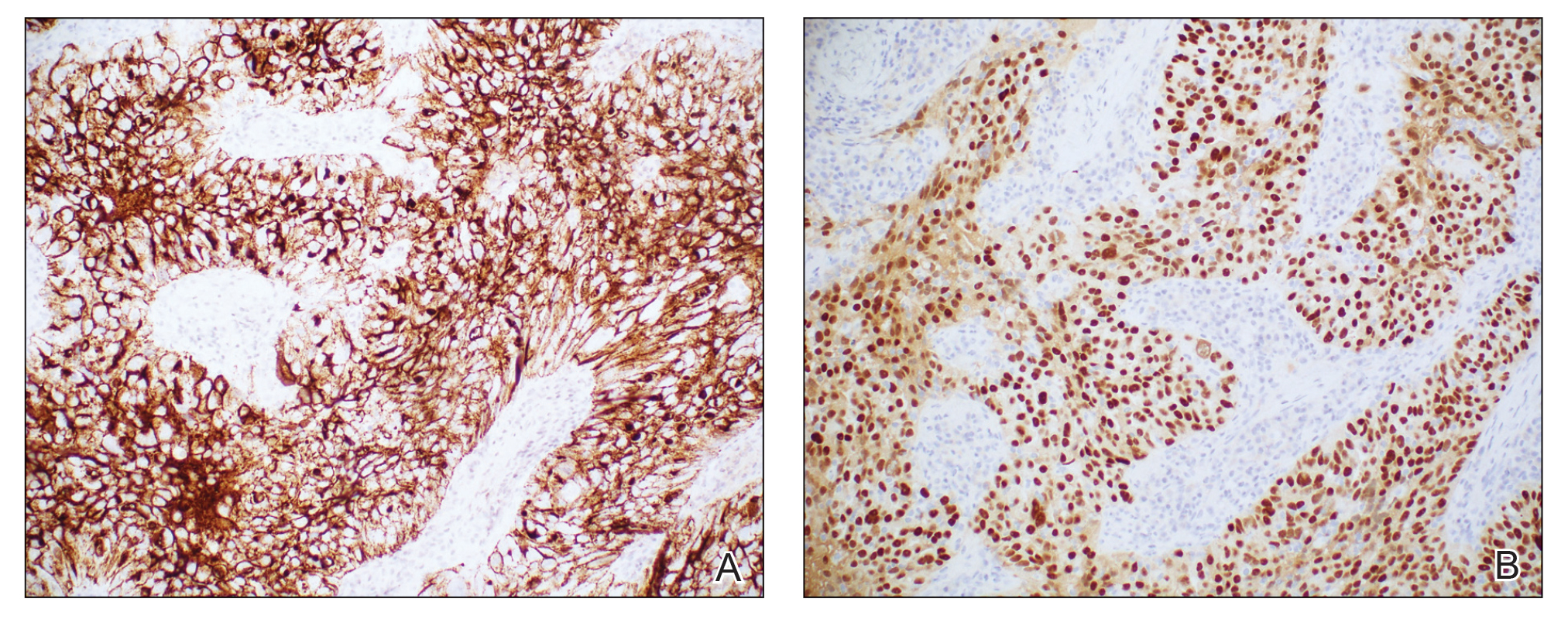

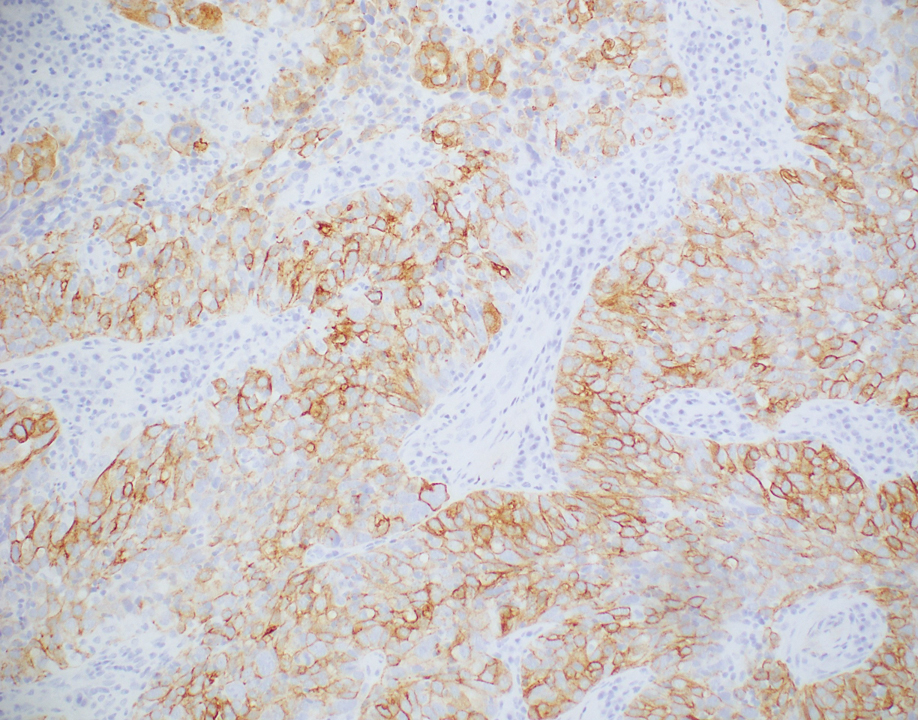

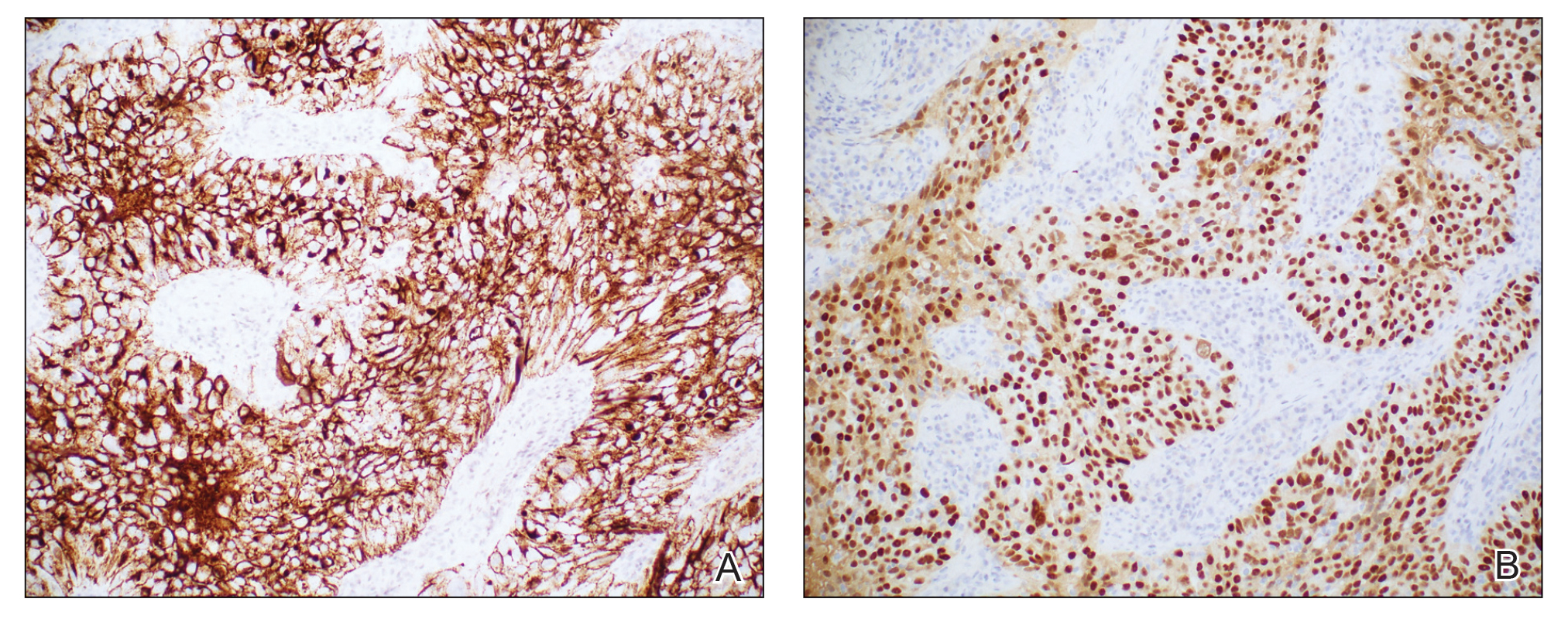

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

A 64-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our dermatology clinic with an intermittent eczematous rash around the eyelids of 3 months’ duration. While performing a total-body skin examination, a firm pink nodule with a smooth surface incidentally was discovered on the umbilicus. The patient was uncertain when the lesion first appeared and denied any associated symptoms including pain and bleeding. Additionally, a lymph node examination revealed right inguinal lymphadenopathy. Upon further questioning, she reported worsening muscle weakness, fatigue, night sweats, and an unintentional weight loss of 10 pounds. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was obtained for routine histopathology.

Comment on “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site”

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.