User login

Pertussis vaccination: We can do better

Resources

Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/index.html. Accessed July 6, 2018.

Resources

Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/index.html. Accessed July 6, 2018.

Resources

Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/index.html. Accessed July 6, 2018.

Vector-borne diseases: Trends and take-home points

Resources

Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in reported vectorborne disease cases—United States and territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:496-501.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Repellents: protection against mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: prevent mosquito bites. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/prevent-mosquito-bites.html. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Resources

Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in reported vectorborne disease cases—United States and territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:496-501.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Repellents: protection against mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: prevent mosquito bites. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/prevent-mosquito-bites.html. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Resources

Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in reported vectorborne disease cases—United States and territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:496-501.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Repellents: protection against mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: prevent mosquito bites. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/prevention/prevent-mosquito-bites.html. Accessed June 6, 2018.

USPSTF takes another stab at PSA screening recs

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

Carter HB. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer: revisiting the evidence. JAMA. 2018;319:1866-1868.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer screening final recommendation. Available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/. Accessed May 18, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening, 2008. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening-2008. Accessed May 15, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening. May 2012. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Accessed May 15, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

Carter HB. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer: revisiting the evidence. JAMA. 2018;319:1866-1868.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer screening final recommendation. Available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/. Accessed May 18, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening, 2008. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening-2008. Accessed May 15, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening. May 2012. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Accessed May 15, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1901-1913.

Carter HB. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer: revisiting the evidence. JAMA. 2018;319:1866-1868.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer screening final recommendation. Available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/. Accessed May 18, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening, 2008. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening-2008. Accessed May 15, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Prostate cancer: screening. May 2012. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Accessed May 15, 2018.

USPSTF offers 3 recommendations for preventing falls in older adults

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed May 8, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1696-1704.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults. Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:1705-1716.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed May 8, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1696-1704.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults. Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:1705-1716.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-interventions1. Accessed May 8, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults. US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1696-1704.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults. Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:1705-1716.

USPSTF update: New and revised recommendations

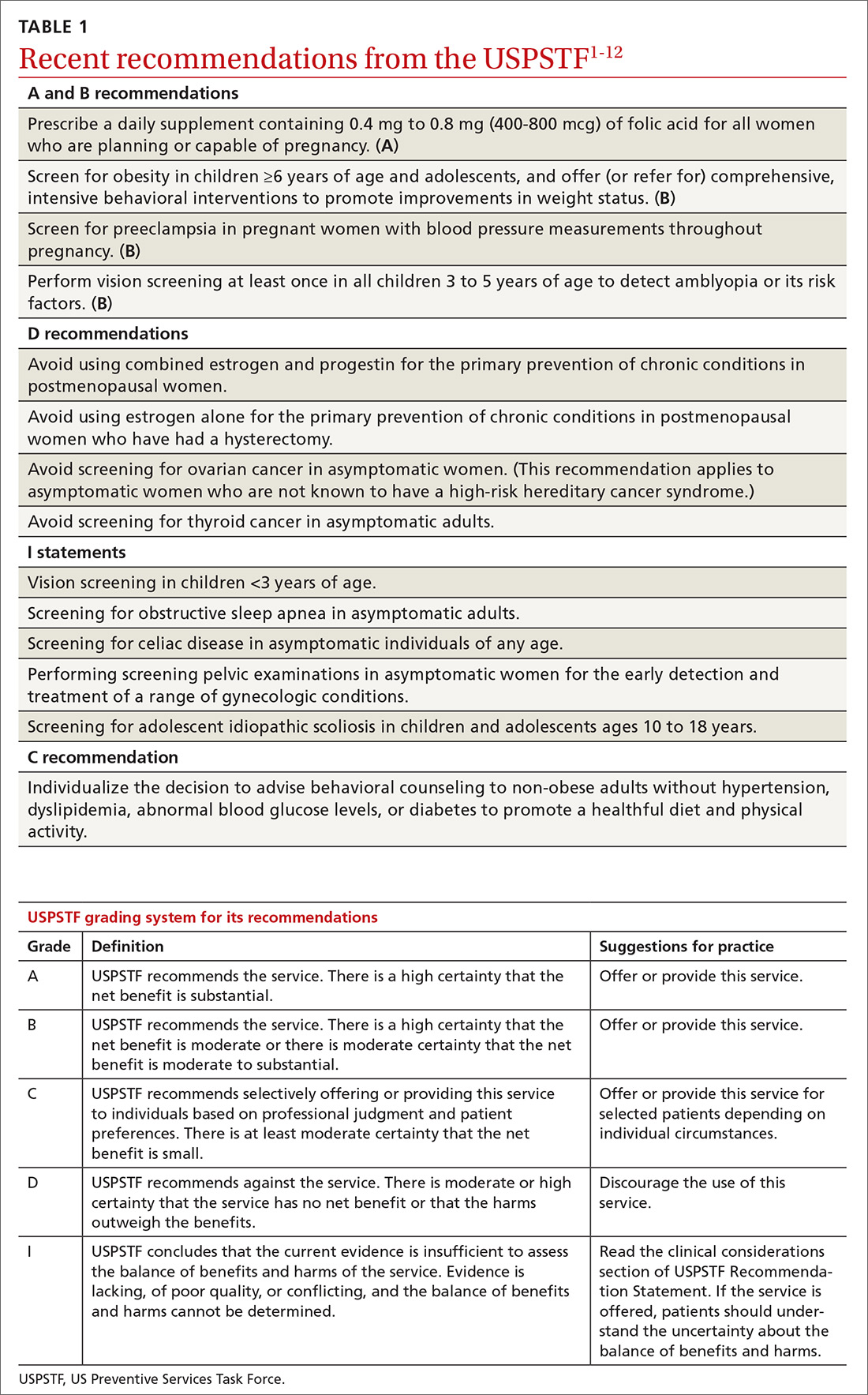

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

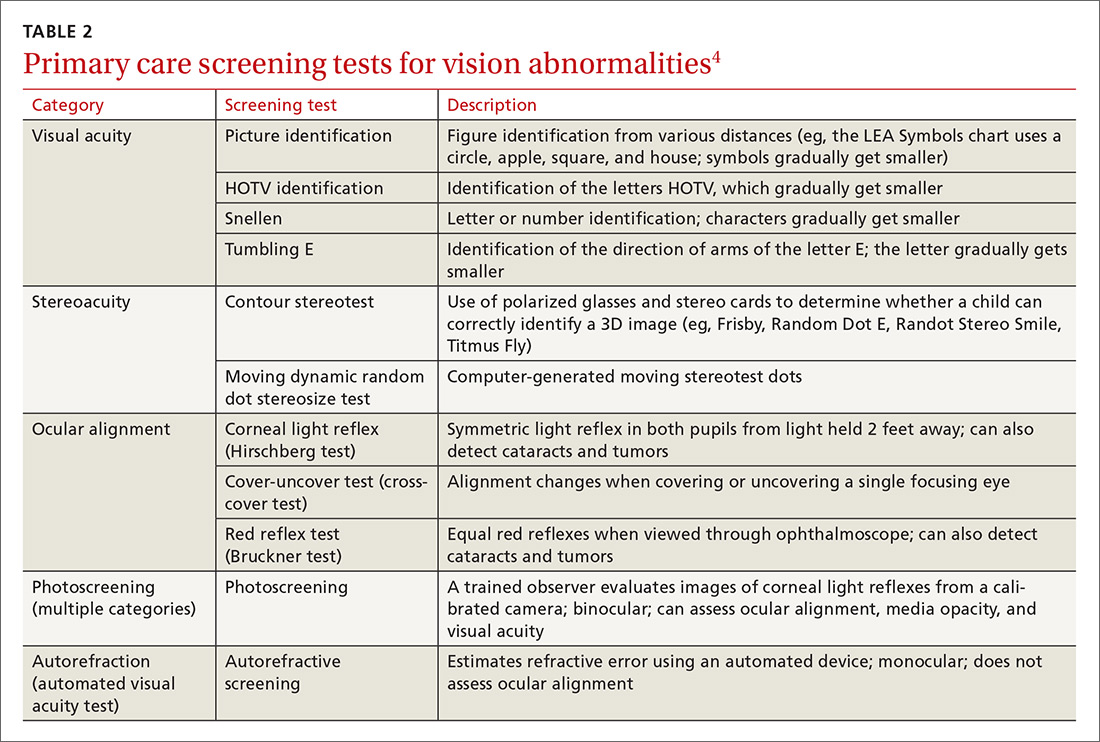

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(5):294-296,298-299.

ACP issues 4 statements on T2DM treatment targets

Resource

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Hemoglobin A1c targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy for nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a guidance statement update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2018; Mar 6. doi: 10.7326/M17-0939. [Epub ahead of print].

Resource

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Hemoglobin A1c targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy for nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a guidance statement update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2018; Mar 6. doi: 10.7326/M17-0939. [Epub ahead of print].

Resource

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Hemoglobin A1c targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy for nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a guidance statement update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2018; Mar 6. doi: 10.7326/M17-0939. [Epub ahead of print].

Why you shouldn’t screen for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women

Resources

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for ovarian cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:588-594.

- Henderson JT, Webber EM, Sawaya GF. Screening for ovarian cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:595-606.

Resources

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for ovarian cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:588-594.

- Henderson JT, Webber EM, Sawaya GF. Screening for ovarian cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:595-606.

Resources

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for ovarian cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:588-594.

- Henderson JT, Webber EM, Sawaya GF. Screening for ovarian cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:595-606.

ACIP vaccine update

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

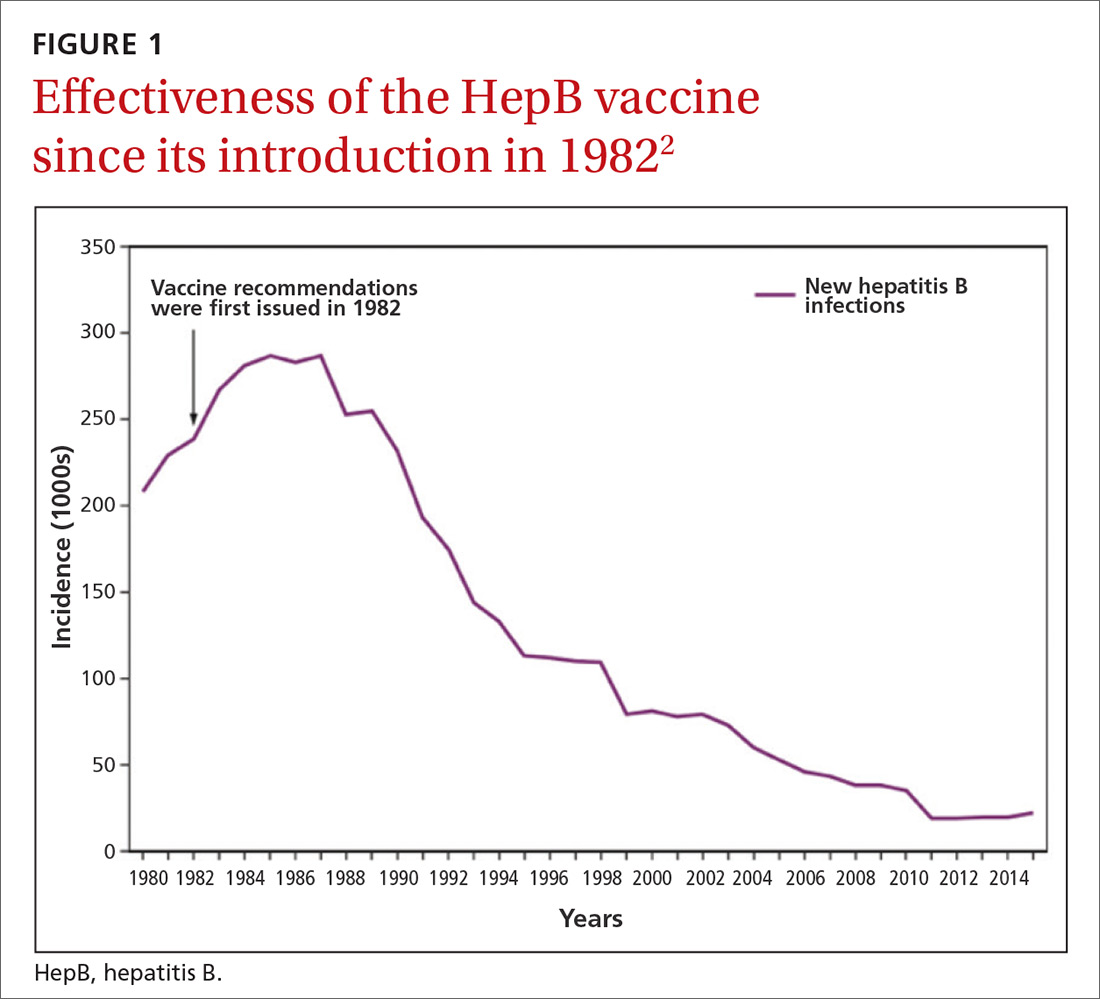

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

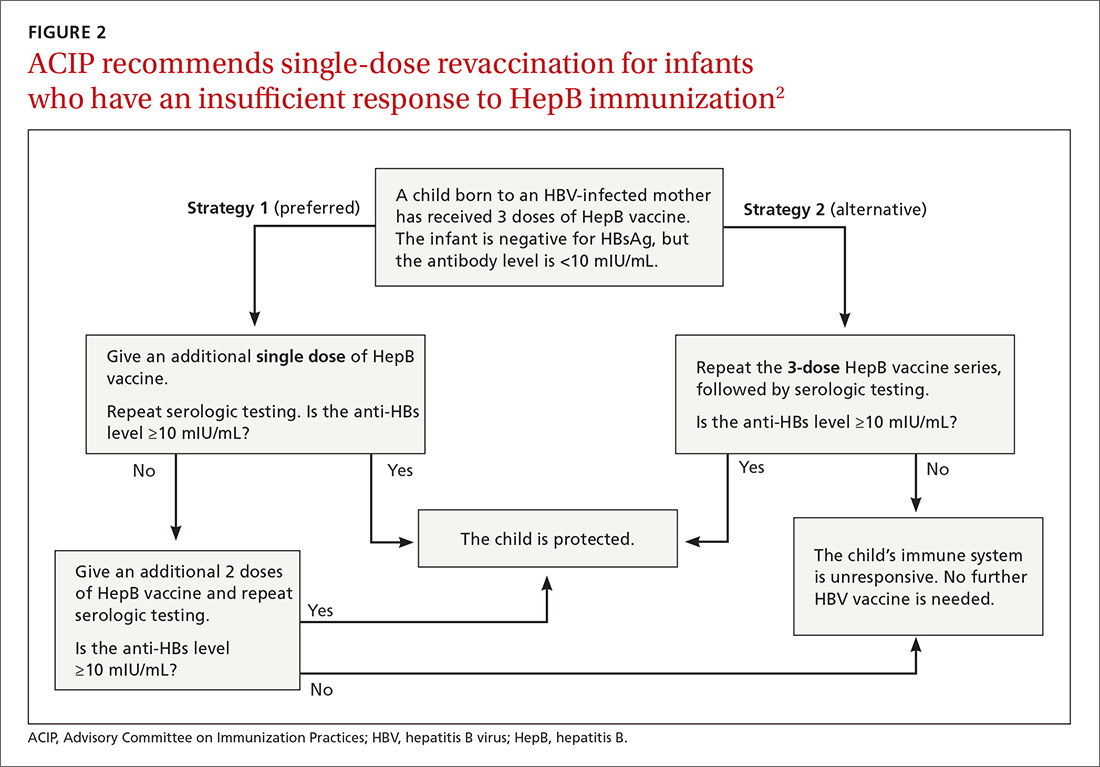

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.

6. Dooling KL. Considerations for the use of herpes zoster vaccines. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/zoster-04-dooling.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

8. Campos-Outcalt D. The new shingles vaccine: what PCPs need to know. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:audio. Available at: https://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/153168/vaccines/new-shingles-vaccine-what-pcps-need-know. Accessed January 19, 2018.

9. Marlow M. Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE): third dose of MMR vaccine. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/mumps-03-marlow-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. HEPLISAV-B [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technology Corporation; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM584762.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018.

11. Janssen R. HEPLISAV-B. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/hepatitis-02-janssen.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.