User login

Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea

- The CDC no longer recommends the use of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of gonococcal infections and associated conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Consequently, only one class of drugs, the cephalosporins, is still recommended and available for the treatment of gonorrhea.

- The CDC now recommends ceftriaxone, 125 mg IM, in a single dose, as the preferred treatment.

- For patients with cephalosporin allergies, azithromycin, 2 g orally, as a single dose, remains an option. The CDC discourages widespread use, however, because of concerns about resistance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released an update to its treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted diseases, stating that fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.1 This change resulted from a progressive increase in the rate of resistance to quinolones among gonorrhea isolated from publicly funded treatment centers across the country.

The new advisory applies to all quinolones previously recommended: ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin.

Epidemiology. Gonorrhea remains common in the United States, with nearly 340,000 cases reported in 2005. Since it is under-reported, estimates are that more than 600,000 cases occur each year.2

Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum, pharynx, and adnexa. It can also cause disseminated disease that can affect joints, heart, and the meninges.

Tracking the spread of resistant cases

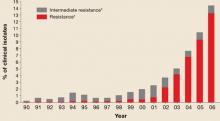

Since the early 1990s, fluoroquinolones have been one of the recommended treatments for gonorrhea because of their availability as effective, single-dose oral regimens. Fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea began to emerge at the end of the century and has progressed rapidly since. FIGURE 1 illustrates the proportion of fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea from the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) by year, from 1990 to 2006.

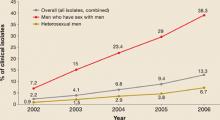

Resistance began to emerge first among gonorrhea isolates from men who have sex with men (MSM), and resistance rates among MSM continue to be higher than in heterosexual men (FIGURE 2).

Geographic trends. In 2000, the CDC recommended that quinolones should no longer be used to treat gonorrhea in persons who contracted the infection in Asia or the Pacific. In 2002, California was added to this list. In 2004, the recommendation against quinolone use was extended to all MSM in the US.

The new recommendation against general use is based on resistance surpassing 5% of total isolates.

FIGURE 1

Percentage of N gonorrhoeae isolates with intermediate resistance or resistance to ciprofloxacin

Data for 2006 are preliminary (January-June only).

* Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.125–0.500 mcg/mL.

† Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of ≥1.0 mcg/ml.

Source: Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinalones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.

MMWR Recomm Rep 2007; 56:332-336.

FIGURE 2

Progressive increase of fluoroquinolone resistance

Percent of isolates from the CDC Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project found to be resistant to fluoroquinalones, 2002 through June 2006

Source: GISP report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2005 Supplement, Gonoccal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) Annual Report 2005. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2007.

Ceftriaxone, the default treatment of choice

The loss of quinolones as a recommended gonorrhea treatment leaves only ceftriaxone, 125 mg intramuscularly (IM), as the only readily available treatment for urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. Cefixime 400 mg as a single dose is also recommended, but is not currently available in tablet form in the US. It is available as a suspension with 100 mg per 5 cc.

Other options

Possible oral options include cefpodoxime 400 mg or cefuroxime axetil 1 g. However, neither has the official endorsement of the CDC, and neither appears effective against pharyngeal infection.

Spectinomycin 2 g intramuscularly is recommended for those with cephalosporin allergy—but, like cefixime, it is not currently available in the US, and it also is not considered effective against pharyngeal infection.

Azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose is currently effective against gonorrhea and is an option for those with cephalosporin allergies. The CDC discourages its widespread use because of concerns about resistance.

New information regarding the availability of spectinomycin and cefixime can be obtained from local health departments or the CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases web site (www.cdc.gov/std).3

Recommended regimens for treatment of gonorrhea

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, and rectum* |

| Recommended regimens† |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| or |

| Cefixime‡ 400 mg in a single oral dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the pharynx* |

| Recommended regimens |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| * For all adult and adolescent patients, regardless of travel history or sexual behavior. For those allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins, or for treatment of disseminated gonococcal infections, PID, and epididymitis, see www.cdc.gov/std/treatment. |

| † Alternative regimens: Spectinomycin 2 g in a single IM dose (not currently available in US) or cephalosporin single-dose regimens. |

| Other single-dose cephalosporin regimens that are considered alternative treatment regimens against uncomplicated urogenital and anorectal gonococcal infections include ceftizoxime 500 mg IM; or cefoxitin 2 g IM, administered with probenecid 1 g orally; or cefotaxime 500 mg IM. Some evidence indicates that cefpodoxime 400 mg and cefuroxime axetil 1 g might be oral alternatives. |

| ‡ 400 mg by suspension; tablets are no longer available in the US. |

| Source: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf.2 |

Associated conditions

Treat for chlamydia if chlamydial infection is not ruled out

The CDC continues to recommend concurrent treatment for chlamydia for all persons who have gonorrhea, unless coinfection has been ruled out.

Therapies for chlamydia include azithromycin 1 g as a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days.

Pelvic inflammatory disease and epididymitis

The treatment of both pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and epididymitis include an option of ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus doxycycline for either 7 days (for epididymitis) or 10 days (for PID). There are several parenteral options for PID and disseminated gonorrhea; these can be found on the CDC’s STD web site.3

Should you always retest to ensure a cure?

It is still not necessary to retest patients who have had the recommended treatments. However, patients with persistent symptoms or rapidly recurring symptoms should be retested by cultures so that drug-resistance patterns can be checked if gonorrhea is documented.

Retest for recurrence

Consider retesting all treated patients after 3 to 6 months, since anyone with a sexually transmitted infection is at risk of being reinfected.

Summary

The ongoing challenges with the evolving resistance patterns of gonorrhea illustrate the importance of physicians accurately diagnosing gonorrhea, treating with recommended regimens, reporting positive cases to the local public health department, and assisting with partner evaluation and treatment.

1. CDC. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:332-336.Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm5614.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-11).-Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

3. Updated recommended treatment regimens for gonococcal infections and associated conditions—United States, April 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/updated-regimens.htm. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

- The CDC no longer recommends the use of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of gonococcal infections and associated conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Consequently, only one class of drugs, the cephalosporins, is still recommended and available for the treatment of gonorrhea.

- The CDC now recommends ceftriaxone, 125 mg IM, in a single dose, as the preferred treatment.

- For patients with cephalosporin allergies, azithromycin, 2 g orally, as a single dose, remains an option. The CDC discourages widespread use, however, because of concerns about resistance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released an update to its treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted diseases, stating that fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.1 This change resulted from a progressive increase in the rate of resistance to quinolones among gonorrhea isolated from publicly funded treatment centers across the country.

The new advisory applies to all quinolones previously recommended: ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin.

Epidemiology. Gonorrhea remains common in the United States, with nearly 340,000 cases reported in 2005. Since it is under-reported, estimates are that more than 600,000 cases occur each year.2

Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum, pharynx, and adnexa. It can also cause disseminated disease that can affect joints, heart, and the meninges.

Tracking the spread of resistant cases

Since the early 1990s, fluoroquinolones have been one of the recommended treatments for gonorrhea because of their availability as effective, single-dose oral regimens. Fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea began to emerge at the end of the century and has progressed rapidly since. FIGURE 1 illustrates the proportion of fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea from the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) by year, from 1990 to 2006.

Resistance began to emerge first among gonorrhea isolates from men who have sex with men (MSM), and resistance rates among MSM continue to be higher than in heterosexual men (FIGURE 2).

Geographic trends. In 2000, the CDC recommended that quinolones should no longer be used to treat gonorrhea in persons who contracted the infection in Asia or the Pacific. In 2002, California was added to this list. In 2004, the recommendation against quinolone use was extended to all MSM in the US.

The new recommendation against general use is based on resistance surpassing 5% of total isolates.

FIGURE 1

Percentage of N gonorrhoeae isolates with intermediate resistance or resistance to ciprofloxacin

Data for 2006 are preliminary (January-June only).

* Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.125–0.500 mcg/mL.

† Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of ≥1.0 mcg/ml.

Source: Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinalones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.

MMWR Recomm Rep 2007; 56:332-336.

FIGURE 2

Progressive increase of fluoroquinolone resistance

Percent of isolates from the CDC Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project found to be resistant to fluoroquinalones, 2002 through June 2006

Source: GISP report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2005 Supplement, Gonoccal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) Annual Report 2005. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2007.

Ceftriaxone, the default treatment of choice

The loss of quinolones as a recommended gonorrhea treatment leaves only ceftriaxone, 125 mg intramuscularly (IM), as the only readily available treatment for urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. Cefixime 400 mg as a single dose is also recommended, but is not currently available in tablet form in the US. It is available as a suspension with 100 mg per 5 cc.

Other options

Possible oral options include cefpodoxime 400 mg or cefuroxime axetil 1 g. However, neither has the official endorsement of the CDC, and neither appears effective against pharyngeal infection.

Spectinomycin 2 g intramuscularly is recommended for those with cephalosporin allergy—but, like cefixime, it is not currently available in the US, and it also is not considered effective against pharyngeal infection.

Azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose is currently effective against gonorrhea and is an option for those with cephalosporin allergies. The CDC discourages its widespread use because of concerns about resistance.

New information regarding the availability of spectinomycin and cefixime can be obtained from local health departments or the CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases web site (www.cdc.gov/std).3

Recommended regimens for treatment of gonorrhea

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, and rectum* |

| Recommended regimens† |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| or |

| Cefixime‡ 400 mg in a single oral dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the pharynx* |

| Recommended regimens |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| * For all adult and adolescent patients, regardless of travel history or sexual behavior. For those allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins, or for treatment of disseminated gonococcal infections, PID, and epididymitis, see www.cdc.gov/std/treatment. |

| † Alternative regimens: Spectinomycin 2 g in a single IM dose (not currently available in US) or cephalosporin single-dose regimens. |

| Other single-dose cephalosporin regimens that are considered alternative treatment regimens against uncomplicated urogenital and anorectal gonococcal infections include ceftizoxime 500 mg IM; or cefoxitin 2 g IM, administered with probenecid 1 g orally; or cefotaxime 500 mg IM. Some evidence indicates that cefpodoxime 400 mg and cefuroxime axetil 1 g might be oral alternatives. |

| ‡ 400 mg by suspension; tablets are no longer available in the US. |

| Source: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf.2 |

Associated conditions

Treat for chlamydia if chlamydial infection is not ruled out

The CDC continues to recommend concurrent treatment for chlamydia for all persons who have gonorrhea, unless coinfection has been ruled out.

Therapies for chlamydia include azithromycin 1 g as a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days.

Pelvic inflammatory disease and epididymitis

The treatment of both pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and epididymitis include an option of ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus doxycycline for either 7 days (for epididymitis) or 10 days (for PID). There are several parenteral options for PID and disseminated gonorrhea; these can be found on the CDC’s STD web site.3

Should you always retest to ensure a cure?

It is still not necessary to retest patients who have had the recommended treatments. However, patients with persistent symptoms or rapidly recurring symptoms should be retested by cultures so that drug-resistance patterns can be checked if gonorrhea is documented.

Retest for recurrence

Consider retesting all treated patients after 3 to 6 months, since anyone with a sexually transmitted infection is at risk of being reinfected.

Summary

The ongoing challenges with the evolving resistance patterns of gonorrhea illustrate the importance of physicians accurately diagnosing gonorrhea, treating with recommended regimens, reporting positive cases to the local public health department, and assisting with partner evaluation and treatment.

- The CDC no longer recommends the use of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of gonococcal infections and associated conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- Consequently, only one class of drugs, the cephalosporins, is still recommended and available for the treatment of gonorrhea.

- The CDC now recommends ceftriaxone, 125 mg IM, in a single dose, as the preferred treatment.

- For patients with cephalosporin allergies, azithromycin, 2 g orally, as a single dose, remains an option. The CDC discourages widespread use, however, because of concerns about resistance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released an update to its treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted diseases, stating that fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.1 This change resulted from a progressive increase in the rate of resistance to quinolones among gonorrhea isolated from publicly funded treatment centers across the country.

The new advisory applies to all quinolones previously recommended: ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin.

Epidemiology. Gonorrhea remains common in the United States, with nearly 340,000 cases reported in 2005. Since it is under-reported, estimates are that more than 600,000 cases occur each year.2

Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum, pharynx, and adnexa. It can also cause disseminated disease that can affect joints, heart, and the meninges.

Tracking the spread of resistant cases

Since the early 1990s, fluoroquinolones have been one of the recommended treatments for gonorrhea because of their availability as effective, single-dose oral regimens. Fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea began to emerge at the end of the century and has progressed rapidly since. FIGURE 1 illustrates the proportion of fluoroquinolone-resistant N gonorrhea from the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) by year, from 1990 to 2006.

Resistance began to emerge first among gonorrhea isolates from men who have sex with men (MSM), and resistance rates among MSM continue to be higher than in heterosexual men (FIGURE 2).

Geographic trends. In 2000, the CDC recommended that quinolones should no longer be used to treat gonorrhea in persons who contracted the infection in Asia or the Pacific. In 2002, California was added to this list. In 2004, the recommendation against quinolone use was extended to all MSM in the US.

The new recommendation against general use is based on resistance surpassing 5% of total isolates.

FIGURE 1

Percentage of N gonorrhoeae isolates with intermediate resistance or resistance to ciprofloxacin

Data for 2006 are preliminary (January-June only).

* Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of 0.125–0.500 mcg/mL.

† Demonstrating ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration of ≥1.0 mcg/ml.

Source: Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinalones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections.

MMWR Recomm Rep 2007; 56:332-336.

FIGURE 2

Progressive increase of fluoroquinolone resistance

Percent of isolates from the CDC Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project found to be resistant to fluoroquinalones, 2002 through June 2006

Source: GISP report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2005 Supplement, Gonoccal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) Annual Report 2005. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2007.

Ceftriaxone, the default treatment of choice

The loss of quinolones as a recommended gonorrhea treatment leaves only ceftriaxone, 125 mg intramuscularly (IM), as the only readily available treatment for urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. Cefixime 400 mg as a single dose is also recommended, but is not currently available in tablet form in the US. It is available as a suspension with 100 mg per 5 cc.

Other options

Possible oral options include cefpodoxime 400 mg or cefuroxime axetil 1 g. However, neither has the official endorsement of the CDC, and neither appears effective against pharyngeal infection.

Spectinomycin 2 g intramuscularly is recommended for those with cephalosporin allergy—but, like cefixime, it is not currently available in the US, and it also is not considered effective against pharyngeal infection.

Azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose is currently effective against gonorrhea and is an option for those with cephalosporin allergies. The CDC discourages its widespread use because of concerns about resistance.

New information regarding the availability of spectinomycin and cefixime can be obtained from local health departments or the CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases web site (www.cdc.gov/std).3

Recommended regimens for treatment of gonorrhea

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, and rectum* |

| Recommended regimens† |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| or |

| Cefixime‡ 400 mg in a single oral dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the pharynx* |

| Recommended regimens |

| Ceftriaxone 125 mg in a single IM dose |

| plus |

| Treatment for chlamydia if chlamydial infection has not been ruled out |

| * For all adult and adolescent patients, regardless of travel history or sexual behavior. For those allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins, or for treatment of disseminated gonococcal infections, PID, and epididymitis, see www.cdc.gov/std/treatment. |

| † Alternative regimens: Spectinomycin 2 g in a single IM dose (not currently available in US) or cephalosporin single-dose regimens. |

| Other single-dose cephalosporin regimens that are considered alternative treatment regimens against uncomplicated urogenital and anorectal gonococcal infections include ceftizoxime 500 mg IM; or cefoxitin 2 g IM, administered with probenecid 1 g orally; or cefotaxime 500 mg IM. Some evidence indicates that cefpodoxime 400 mg and cefuroxime axetil 1 g might be oral alternatives. |

| ‡ 400 mg by suspension; tablets are no longer available in the US. |

| Source: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf.2 |

Associated conditions

Treat for chlamydia if chlamydial infection is not ruled out

The CDC continues to recommend concurrent treatment for chlamydia for all persons who have gonorrhea, unless coinfection has been ruled out.

Therapies for chlamydia include azithromycin 1 g as a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days.

Pelvic inflammatory disease and epididymitis

The treatment of both pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and epididymitis include an option of ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus doxycycline for either 7 days (for epididymitis) or 10 days (for PID). There are several parenteral options for PID and disseminated gonorrhea; these can be found on the CDC’s STD web site.3

Should you always retest to ensure a cure?

It is still not necessary to retest patients who have had the recommended treatments. However, patients with persistent symptoms or rapidly recurring symptoms should be retested by cultures so that drug-resistance patterns can be checked if gonorrhea is documented.

Retest for recurrence

Consider retesting all treated patients after 3 to 6 months, since anyone with a sexually transmitted infection is at risk of being reinfected.

Summary

The ongoing challenges with the evolving resistance patterns of gonorrhea illustrate the importance of physicians accurately diagnosing gonorrhea, treating with recommended regimens, reporting positive cases to the local public health department, and assisting with partner evaluation and treatment.

1. CDC. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:332-336.Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm5614.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-11).-Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

3. Updated recommended treatment regimens for gonococcal infections and associated conditions—United States, April 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/updated-regimens.htm. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

1. CDC. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:332-336.Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm5614.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-11).-Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5511.pdf. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

3. Updated recommended treatment regimens for gonococcal infections and associated conditions—United States, April 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/updated-regimens.htm. Accessed on June 15, 2007.

Screening: New guidance on what and what not to do

One of our key responsibilities is to provide effective preventive services—and avoid performing tests of no value. Since most of us do not have time to keep up with the literature on what services and tests have and have not been proven effective, we depend on trusted authorities to make these assessments for us.

The entity with the most rigorously evidence-based approach is the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). (TABLE 1 lists the criteria for their recommendations.) Every year, this Practice Alert summarizes the new recommendations from the task force. The new recommendations in the 6 disease categories discussed here were published by the USPSTF in 2006 and the first quarter of 2007 (TABLE 2).

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Colon cancer chemoprevention

- Genetic screening for hemochromatosis

- Congenital hip dysplasia

- Elevated lead levels

- Speech delay

TABLE 1

The rigor behind the recommendations

| RECOMMENDATION | EVIDENCE | RESULTS OF THE SERVICE |

|---|---|---|

| A Strongly recommends | Good evidence |

|

| B Recommends | At least fair evidence |

|

| C No recommendation | At least fair evidence |

|

| D Recommends against | At least fair evidence |

|

| I Insufficient evidence | Insufficient to recommend for or against |

|

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

“I” means insufficient evidence

As usual, there are many screening tests that lack evidence either for or against their effectiveness. The Task Force places such tests in the “I” (insufficient evidence) category. Physicians should remember that an “I” recommendation is not the equivalent of a “D” (recommend against).

Screening implies routine testing, and no symptoms

We also need to keep in mind the difference between screening and diagnosis. Screening implies routine testing among asymptomatic patients. Screening recommendations do not apply to symptomatic patients in whom diagnostic testing may be indicated.

1. Iron deficiency anemia

The task force recommends

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women, and

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at increased risk for iron deficiency anemia.1

The task force concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months,

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at average risk for iron deficiency anemia,

- iron supplementation for nonanemic pregnant women.1

Iron deficiency anemia is linked to developmental and cognitive abnormalities in children and poorer birth outcomes in pregnant women. The task force felt that the weight of the evidence supports a set of recommendations that includes screening all pregnant women and using iron preparations for those who have deficiency, and using routine iron supplementation for at-risk infants between the ages of 6 and 12 months.

The lack of a recommendation on screening all children was based on concern about the accuracy of hemoglobin as a screening test for iron deficiency and a scarcity of evidence that universal screening results in improved outcomes. Routine iron supplementation was felt to be of proven benefit only for infants at increased risk: those from low socioeconomic backgrounds and premature and low birth weight infants.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agrees that screening should be performed in high-risk infants and all pregnant women, but recommends universal iron supplementation during pregnancy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening all infants twice (at age 9 to 12 months, and 6 months later) along with dietary interventions to prevent iron deficiency, such as: breast-feeding or the use of iron-fortified formula, and the introduction of iron-rich foods at age 6 months.

2. Colon cancer

The task force recommends against routine use of aspirin and NSAIDs to prevent colorectal cancer in individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer.2

Colon cancer is common and a common cause of cancer mortality,3 and proven secondary preventions are available. Chemoprevention is a potential method of primary prevention; it has some benefits as well as harms. The task force concluded that the documented harms exceed the potential benefits.

- Aspirin taken at the high-dose regimen (350–700 mg/day) needed to protect from colon cancer increases the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke. A lower dose of aspirin (75–350 mg/day) is used for chemoprevention in adults who are at increased risk for coronary heart disease but this does not protect against colon cancer.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer, but they also increase the risks of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal injury.

- Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors have been linked to increases in coronary artery disease.

3. Hemochromatosis

The task force recommends against routine genetic screening for hereditary hemochromatosis in the asymptomatic general population.4

Hemochromatosis is rare, and only a small proportion of those with the high-risk genotype actually develop the disease. The effectiveness of early intervention is unproven, and the potential for harm from false positives is significant.

The D recommendation does not apply to those with signs and symptoms consistent with hemochromatosis or a strong family history of the disease. Nor does it pertain to non-genetic laboratory tests to identify iron overload (although these also lack proof that they improve outcomes in the general population).

4. Congenital hip dysplasia

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants as a means to prevent adverse outcomes.5

Physical examination and ultrasonography have limited accuracy in finding hip dysplasia, and there is a high rate of natural resolution (60% to 90%) of hip abnormalities found with these tests. Both surgical and non-surgical treatments lack evidence of effectiveness and are associated with potential for harm from avascular necrosis, high costs, and complications from surgery and anesthesia.

This uncertainty applies only to asymptomatic infants—not to those who have obvious hip dislocations or other hip abnormalities.

5. Elevated lead levels

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 who are at increased risk.6

The task force recommends against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in:

- asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 years who are at average risk

- asymptomatic pregnant women.6

The reduction of lead in the environment, especially the reduction of leadbased gasoline, has resulted in a decline in elevated blood lead levels in the United States. The task force’s uncertainty regarding screening at-risk children centered around a lack of evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in decreasing blood lead levels. Other organizations that continue to recommend screening in high-risk children include the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics. The main risk factor for elevated blood lead levels is living in housing constructed before 1950.

The recommendation against screening in pregnant women was based on the low prevalence, no evidence for effectiveness of interventions to decrease lead levels, and potential harms from screening. This recommendation agrees with those of other organizations.

Speech delay

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine use of brief, formal screening instruments in primary care to detect speech and language delay in children up to 5 years of age.7

While speech delay affects 5% to 8% of children under the age of 5, and interventions can result in short-term improvements, long-term benefits have not been studied. It is also unclear whether the brief screening tools used in primary care accurately identify children who will benefit from interventions, or whether the results of early intervention are better than when difficulties are first identified by parents. Overall, the task force felt that we lack sufficient evidence to evaluate overall benefits and harms of brief formal screening tools in primary care among asymptomatic children.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 N Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012; dougco@u.arizona.edu.

1. USPSTF. Screening for iron deficiency anemia—including iron supplementation for children and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsiron.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

2. USPSTF. Routine aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

3. USPSTF. Screening for colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

4. USPSTF. Screening for hemochromatosis. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemoch.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

5. USPSTF. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshipd.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

6. USPSTF. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in childhood and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspslead.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

7. USPSTF. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschdv.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

One of our key responsibilities is to provide effective preventive services—and avoid performing tests of no value. Since most of us do not have time to keep up with the literature on what services and tests have and have not been proven effective, we depend on trusted authorities to make these assessments for us.

The entity with the most rigorously evidence-based approach is the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). (TABLE 1 lists the criteria for their recommendations.) Every year, this Practice Alert summarizes the new recommendations from the task force. The new recommendations in the 6 disease categories discussed here were published by the USPSTF in 2006 and the first quarter of 2007 (TABLE 2).

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Colon cancer chemoprevention

- Genetic screening for hemochromatosis

- Congenital hip dysplasia

- Elevated lead levels

- Speech delay

TABLE 1

The rigor behind the recommendations

| RECOMMENDATION | EVIDENCE | RESULTS OF THE SERVICE |

|---|---|---|

| A Strongly recommends | Good evidence |

|

| B Recommends | At least fair evidence |

|

| C No recommendation | At least fair evidence |

|

| D Recommends against | At least fair evidence |

|

| I Insufficient evidence | Insufficient to recommend for or against |

|

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

“I” means insufficient evidence

As usual, there are many screening tests that lack evidence either for or against their effectiveness. The Task Force places such tests in the “I” (insufficient evidence) category. Physicians should remember that an “I” recommendation is not the equivalent of a “D” (recommend against).

Screening implies routine testing, and no symptoms

We also need to keep in mind the difference between screening and diagnosis. Screening implies routine testing among asymptomatic patients. Screening recommendations do not apply to symptomatic patients in whom diagnostic testing may be indicated.

1. Iron deficiency anemia

The task force recommends

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women, and

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at increased risk for iron deficiency anemia.1

The task force concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months,

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at average risk for iron deficiency anemia,

- iron supplementation for nonanemic pregnant women.1

Iron deficiency anemia is linked to developmental and cognitive abnormalities in children and poorer birth outcomes in pregnant women. The task force felt that the weight of the evidence supports a set of recommendations that includes screening all pregnant women and using iron preparations for those who have deficiency, and using routine iron supplementation for at-risk infants between the ages of 6 and 12 months.

The lack of a recommendation on screening all children was based on concern about the accuracy of hemoglobin as a screening test for iron deficiency and a scarcity of evidence that universal screening results in improved outcomes. Routine iron supplementation was felt to be of proven benefit only for infants at increased risk: those from low socioeconomic backgrounds and premature and low birth weight infants.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agrees that screening should be performed in high-risk infants and all pregnant women, but recommends universal iron supplementation during pregnancy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening all infants twice (at age 9 to 12 months, and 6 months later) along with dietary interventions to prevent iron deficiency, such as: breast-feeding or the use of iron-fortified formula, and the introduction of iron-rich foods at age 6 months.

2. Colon cancer

The task force recommends against routine use of aspirin and NSAIDs to prevent colorectal cancer in individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer.2

Colon cancer is common and a common cause of cancer mortality,3 and proven secondary preventions are available. Chemoprevention is a potential method of primary prevention; it has some benefits as well as harms. The task force concluded that the documented harms exceed the potential benefits.

- Aspirin taken at the high-dose regimen (350–700 mg/day) needed to protect from colon cancer increases the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke. A lower dose of aspirin (75–350 mg/day) is used for chemoprevention in adults who are at increased risk for coronary heart disease but this does not protect against colon cancer.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer, but they also increase the risks of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal injury.

- Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors have been linked to increases in coronary artery disease.

3. Hemochromatosis

The task force recommends against routine genetic screening for hereditary hemochromatosis in the asymptomatic general population.4

Hemochromatosis is rare, and only a small proportion of those with the high-risk genotype actually develop the disease. The effectiveness of early intervention is unproven, and the potential for harm from false positives is significant.

The D recommendation does not apply to those with signs and symptoms consistent with hemochromatosis or a strong family history of the disease. Nor does it pertain to non-genetic laboratory tests to identify iron overload (although these also lack proof that they improve outcomes in the general population).

4. Congenital hip dysplasia

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants as a means to prevent adverse outcomes.5

Physical examination and ultrasonography have limited accuracy in finding hip dysplasia, and there is a high rate of natural resolution (60% to 90%) of hip abnormalities found with these tests. Both surgical and non-surgical treatments lack evidence of effectiveness and are associated with potential for harm from avascular necrosis, high costs, and complications from surgery and anesthesia.

This uncertainty applies only to asymptomatic infants—not to those who have obvious hip dislocations or other hip abnormalities.

5. Elevated lead levels

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 who are at increased risk.6

The task force recommends against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in:

- asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 years who are at average risk

- asymptomatic pregnant women.6

The reduction of lead in the environment, especially the reduction of leadbased gasoline, has resulted in a decline in elevated blood lead levels in the United States. The task force’s uncertainty regarding screening at-risk children centered around a lack of evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in decreasing blood lead levels. Other organizations that continue to recommend screening in high-risk children include the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics. The main risk factor for elevated blood lead levels is living in housing constructed before 1950.

The recommendation against screening in pregnant women was based on the low prevalence, no evidence for effectiveness of interventions to decrease lead levels, and potential harms from screening. This recommendation agrees with those of other organizations.

Speech delay

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine use of brief, formal screening instruments in primary care to detect speech and language delay in children up to 5 years of age.7

While speech delay affects 5% to 8% of children under the age of 5, and interventions can result in short-term improvements, long-term benefits have not been studied. It is also unclear whether the brief screening tools used in primary care accurately identify children who will benefit from interventions, or whether the results of early intervention are better than when difficulties are first identified by parents. Overall, the task force felt that we lack sufficient evidence to evaluate overall benefits and harms of brief formal screening tools in primary care among asymptomatic children.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 N Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012; dougco@u.arizona.edu.

One of our key responsibilities is to provide effective preventive services—and avoid performing tests of no value. Since most of us do not have time to keep up with the literature on what services and tests have and have not been proven effective, we depend on trusted authorities to make these assessments for us.

The entity with the most rigorously evidence-based approach is the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). (TABLE 1 lists the criteria for their recommendations.) Every year, this Practice Alert summarizes the new recommendations from the task force. The new recommendations in the 6 disease categories discussed here were published by the USPSTF in 2006 and the first quarter of 2007 (TABLE 2).

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Colon cancer chemoprevention

- Genetic screening for hemochromatosis

- Congenital hip dysplasia

- Elevated lead levels

- Speech delay

TABLE 1

The rigor behind the recommendations

| RECOMMENDATION | EVIDENCE | RESULTS OF THE SERVICE |

|---|---|---|

| A Strongly recommends | Good evidence |

|

| B Recommends | At least fair evidence |

|

| C No recommendation | At least fair evidence |

|

| D Recommends against | At least fair evidence |

|

| I Insufficient evidence | Insufficient to recommend for or against |

|

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

“I” means insufficient evidence

As usual, there are many screening tests that lack evidence either for or against their effectiveness. The Task Force places such tests in the “I” (insufficient evidence) category. Physicians should remember that an “I” recommendation is not the equivalent of a “D” (recommend against).

Screening implies routine testing, and no symptoms

We also need to keep in mind the difference between screening and diagnosis. Screening implies routine testing among asymptomatic patients. Screening recommendations do not apply to symptomatic patients in whom diagnostic testing may be indicated.

1. Iron deficiency anemia

The task force recommends

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women, and

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at increased risk for iron deficiency anemia.1

The task force concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against

- routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months,

- iron supplementation for asymptomatic children ages 6 to 12 months who are at average risk for iron deficiency anemia,

- iron supplementation for nonanemic pregnant women.1

Iron deficiency anemia is linked to developmental and cognitive abnormalities in children and poorer birth outcomes in pregnant women. The task force felt that the weight of the evidence supports a set of recommendations that includes screening all pregnant women and using iron preparations for those who have deficiency, and using routine iron supplementation for at-risk infants between the ages of 6 and 12 months.

The lack of a recommendation on screening all children was based on concern about the accuracy of hemoglobin as a screening test for iron deficiency and a scarcity of evidence that universal screening results in improved outcomes. Routine iron supplementation was felt to be of proven benefit only for infants at increased risk: those from low socioeconomic backgrounds and premature and low birth weight infants.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agrees that screening should be performed in high-risk infants and all pregnant women, but recommends universal iron supplementation during pregnancy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening all infants twice (at age 9 to 12 months, and 6 months later) along with dietary interventions to prevent iron deficiency, such as: breast-feeding or the use of iron-fortified formula, and the introduction of iron-rich foods at age 6 months.

2. Colon cancer

The task force recommends against routine use of aspirin and NSAIDs to prevent colorectal cancer in individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer.2

Colon cancer is common and a common cause of cancer mortality,3 and proven secondary preventions are available. Chemoprevention is a potential method of primary prevention; it has some benefits as well as harms. The task force concluded that the documented harms exceed the potential benefits.

- Aspirin taken at the high-dose regimen (350–700 mg/day) needed to protect from colon cancer increases the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke. A lower dose of aspirin (75–350 mg/day) is used for chemoprevention in adults who are at increased risk for coronary heart disease but this does not protect against colon cancer.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer, but they also increase the risks of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal injury.

- Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors have been linked to increases in coronary artery disease.

3. Hemochromatosis

The task force recommends against routine genetic screening for hereditary hemochromatosis in the asymptomatic general population.4

Hemochromatosis is rare, and only a small proportion of those with the high-risk genotype actually develop the disease. The effectiveness of early intervention is unproven, and the potential for harm from false positives is significant.

The D recommendation does not apply to those with signs and symptoms consistent with hemochromatosis or a strong family history of the disease. Nor does it pertain to non-genetic laboratory tests to identify iron overload (although these also lack proof that they improve outcomes in the general population).

4. Congenital hip dysplasia

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants as a means to prevent adverse outcomes.5

Physical examination and ultrasonography have limited accuracy in finding hip dysplasia, and there is a high rate of natural resolution (60% to 90%) of hip abnormalities found with these tests. Both surgical and non-surgical treatments lack evidence of effectiveness and are associated with potential for harm from avascular necrosis, high costs, and complications from surgery and anesthesia.

This uncertainty applies only to asymptomatic infants—not to those who have obvious hip dislocations or other hip abnormalities.

5. Elevated lead levels

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 who are at increased risk.6

The task force recommends against routine screening for elevated blood lead levels in:

- asymptomatic children ages 1 to 5 years who are at average risk

- asymptomatic pregnant women.6

The reduction of lead in the environment, especially the reduction of leadbased gasoline, has resulted in a decline in elevated blood lead levels in the United States. The task force’s uncertainty regarding screening at-risk children centered around a lack of evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in decreasing blood lead levels. Other organizations that continue to recommend screening in high-risk children include the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics. The main risk factor for elevated blood lead levels is living in housing constructed before 1950.

The recommendation against screening in pregnant women was based on the low prevalence, no evidence for effectiveness of interventions to decrease lead levels, and potential harms from screening. This recommendation agrees with those of other organizations.

Speech delay

The task force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine use of brief, formal screening instruments in primary care to detect speech and language delay in children up to 5 years of age.7

While speech delay affects 5% to 8% of children under the age of 5, and interventions can result in short-term improvements, long-term benefits have not been studied. It is also unclear whether the brief screening tools used in primary care accurately identify children who will benefit from interventions, or whether the results of early intervention are better than when difficulties are first identified by parents. Overall, the task force felt that we lack sufficient evidence to evaluate overall benefits and harms of brief formal screening tools in primary care among asymptomatic children.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 N Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012; dougco@u.arizona.edu.

1. USPSTF. Screening for iron deficiency anemia—including iron supplementation for children and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsiron.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

2. USPSTF. Routine aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

3. USPSTF. Screening for colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

4. USPSTF. Screening for hemochromatosis. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemoch.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

5. USPSTF. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshipd.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

6. USPSTF. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in childhood and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspslead.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

7. USPSTF. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschdv.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

1. USPSTF. Screening for iron deficiency anemia—including iron supplementation for children and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsiron.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

2. USPSTF. Routine aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

3. USPSTF. Screening for colorectal cancer. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

4. USPSTF. Screening for hemochromatosis. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemoch.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

5. USPSTF. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshipd.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

6. USPSTF. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in childhood and pregnant women. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspslead.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

7. USPSTF. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschdv.htm. Accessed on May 17, 2007.

Immunization update: Latest recommendations from the CDC

How effective is the new varicella zoster virus vaccine and when should adults receive it?

Who should recieve the new Tdap vaccine?

The answers to these and other immunization-related questions are addressed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a number of recently-issued immunization recommendations. Here, by vaccine, is a quick review of these recommendations. (Several were reviewed in a previous Practice Alert. March 2007 issue of JFPRotavirus vaccine is 74% effective in preventing all rotavirus gastroenteritis and 98% effective in preventing severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.4 It is contraindicated in those who have had a severe allergic reaction to the vaccine and should be used with caution in children with altered immunocompetence, acute gastroenteritis, and moderate-to-severe illness. Even though it’s a modified live virus, it can be used in infants even if someone in the household is pregnant or immune-deficient.

Human papilloma virus

The quadrivalent human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2006; the CDC released its recommendations for its use in March 2007.5 The vaccine should be administered routinely to all girls aged 11 to 12 and can be started as early as age 9. The vaccine should also be given to women ages 13 to 26 who have not previously received the vaccine.

HPV is responsible for over 6 million new infections per year, although only a small proportion of these infections involve types that pose high risk for cervical cancer.5,6 The virus is associated with cervical cancer, genital warts, anal cancer, and possibly oral and pharyngeal cancer. TABLE 3 shows the number of each type of cancer that occurs in the US each year and the proportion attributed to HPV. There are over 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 3700 deaths from the disease each year.7,8

The HPV vaccine is produced in yeast using recombinant DNA technology and contains virus-like products of 4 HPV subtypes (6, 11, 16, and 18) that are responsible for between 60% and 80% of cervical cancers in the US. It prevents persistent HPV infection, genital warts, and cervical, vaginal and vulvar precancerous lesions due to the 4 subtypes contained. Since the vaccine does not completely protect from cervical cancer, Pap smear testing is still recommended after vaccination.

The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in 3 doses at months 0, 2, and 6. The minimum interval between doses 1 and 2 is 4 weeks and between doses 2 and 3, 12 weeks. It is contraindicated in those with allergies to yeast and other vaccine components. It can be coadministered with other vaccines but should be deferred for moderate to severe illness. The most common side effects are pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site; fever occurs at a rate slightly above placebo. The vaccine has not been tested for safety for use in pregnancy, but inadvertent administration during pregnancy has not led to any documented adverse effects.

TABLE 3

Cancers associated with HPV—US, 2003

| CANCER | CASES | % ATTRIBUTABLE TO ONCOGENIC HPV |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix* | 11,820 | 100 |

| Anus† | 4187 | 90 |

| Vulva† | 3507 | 40 |

| Vagina† | 1070 | 40 |

| Penis† | 1059 | 40 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx† | 29,627 | ≤12 |

| *A total of 70% of these cancers are attributable to HPV types 16 or 18. | ||

| †Majority of these cancers are attributable to HPV type 16. | ||

| Sources: US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 2003. Incidence and Mortality. Altanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, and the National Cancer Institute; 2006; Parkin M. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118:3030–3044. | ||

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 55 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004. dougco@u.arizona.edu

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you up to date with new immunization recommendations? J Fam Pract 2006;55:232-234.

2. CDC. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for Use of Tdap Among HealthCare Personnel. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005;55(RR-17):1-33.

3. CDC. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: Immunization of Adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-16):1-25.

4. CDC. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-12):1-13.

5. CDC. Quadrivalent human papilloma virus vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2007;56(RR-2):1-24.

6. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 2007;297:813-819.

How effective is the new varicella zoster virus vaccine and when should adults receive it?

Who should recieve the new Tdap vaccine?

The answers to these and other immunization-related questions are addressed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a number of recently-issued immunization recommendations. Here, by vaccine, is a quick review of these recommendations. (Several were reviewed in a previous Practice Alert. March 2007 issue of JFPRotavirus vaccine is 74% effective in preventing all rotavirus gastroenteritis and 98% effective in preventing severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.4 It is contraindicated in those who have had a severe allergic reaction to the vaccine and should be used with caution in children with altered immunocompetence, acute gastroenteritis, and moderate-to-severe illness. Even though it’s a modified live virus, it can be used in infants even if someone in the household is pregnant or immune-deficient.

Human papilloma virus

The quadrivalent human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2006; the CDC released its recommendations for its use in March 2007.5 The vaccine should be administered routinely to all girls aged 11 to 12 and can be started as early as age 9. The vaccine should also be given to women ages 13 to 26 who have not previously received the vaccine.

HPV is responsible for over 6 million new infections per year, although only a small proportion of these infections involve types that pose high risk for cervical cancer.5,6 The virus is associated with cervical cancer, genital warts, anal cancer, and possibly oral and pharyngeal cancer. TABLE 3 shows the number of each type of cancer that occurs in the US each year and the proportion attributed to HPV. There are over 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 3700 deaths from the disease each year.7,8

The HPV vaccine is produced in yeast using recombinant DNA technology and contains virus-like products of 4 HPV subtypes (6, 11, 16, and 18) that are responsible for between 60% and 80% of cervical cancers in the US. It prevents persistent HPV infection, genital warts, and cervical, vaginal and vulvar precancerous lesions due to the 4 subtypes contained. Since the vaccine does not completely protect from cervical cancer, Pap smear testing is still recommended after vaccination.

The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in 3 doses at months 0, 2, and 6. The minimum interval between doses 1 and 2 is 4 weeks and between doses 2 and 3, 12 weeks. It is contraindicated in those with allergies to yeast and other vaccine components. It can be coadministered with other vaccines but should be deferred for moderate to severe illness. The most common side effects are pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site; fever occurs at a rate slightly above placebo. The vaccine has not been tested for safety for use in pregnancy, but inadvertent administration during pregnancy has not led to any documented adverse effects.

TABLE 3

Cancers associated with HPV—US, 2003

| CANCER | CASES | % ATTRIBUTABLE TO ONCOGENIC HPV |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix* | 11,820 | 100 |

| Anus† | 4187 | 90 |

| Vulva† | 3507 | 40 |

| Vagina† | 1070 | 40 |

| Penis† | 1059 | 40 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx† | 29,627 | ≤12 |

| *A total of 70% of these cancers are attributable to HPV types 16 or 18. | ||

| †Majority of these cancers are attributable to HPV type 16. | ||

| Sources: US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 2003. Incidence and Mortality. Altanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, and the National Cancer Institute; 2006; Parkin M. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118:3030–3044. | ||

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 55 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004. dougco@u.arizona.edu

How effective is the new varicella zoster virus vaccine and when should adults receive it?

Who should recieve the new Tdap vaccine?

The answers to these and other immunization-related questions are addressed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a number of recently-issued immunization recommendations. Here, by vaccine, is a quick review of these recommendations. (Several were reviewed in a previous Practice Alert. March 2007 issue of JFPRotavirus vaccine is 74% effective in preventing all rotavirus gastroenteritis and 98% effective in preventing severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.4 It is contraindicated in those who have had a severe allergic reaction to the vaccine and should be used with caution in children with altered immunocompetence, acute gastroenteritis, and moderate-to-severe illness. Even though it’s a modified live virus, it can be used in infants even if someone in the household is pregnant or immune-deficient.

Human papilloma virus

The quadrivalent human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2006; the CDC released its recommendations for its use in March 2007.5 The vaccine should be administered routinely to all girls aged 11 to 12 and can be started as early as age 9. The vaccine should also be given to women ages 13 to 26 who have not previously received the vaccine.

HPV is responsible for over 6 million new infections per year, although only a small proportion of these infections involve types that pose high risk for cervical cancer.5,6 The virus is associated with cervical cancer, genital warts, anal cancer, and possibly oral and pharyngeal cancer. TABLE 3 shows the number of each type of cancer that occurs in the US each year and the proportion attributed to HPV. There are over 11,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 3700 deaths from the disease each year.7,8

The HPV vaccine is produced in yeast using recombinant DNA technology and contains virus-like products of 4 HPV subtypes (6, 11, 16, and 18) that are responsible for between 60% and 80% of cervical cancers in the US. It prevents persistent HPV infection, genital warts, and cervical, vaginal and vulvar precancerous lesions due to the 4 subtypes contained. Since the vaccine does not completely protect from cervical cancer, Pap smear testing is still recommended after vaccination.

The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in 3 doses at months 0, 2, and 6. The minimum interval between doses 1 and 2 is 4 weeks and between doses 2 and 3, 12 weeks. It is contraindicated in those with allergies to yeast and other vaccine components. It can be coadministered with other vaccines but should be deferred for moderate to severe illness. The most common side effects are pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site; fever occurs at a rate slightly above placebo. The vaccine has not been tested for safety for use in pregnancy, but inadvertent administration during pregnancy has not led to any documented adverse effects.

TABLE 3

Cancers associated with HPV—US, 2003

| CANCER | CASES | % ATTRIBUTABLE TO ONCOGENIC HPV |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix* | 11,820 | 100 |

| Anus† | 4187 | 90 |

| Vulva† | 3507 | 40 |

| Vagina† | 1070 | 40 |

| Penis† | 1059 | 40 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx† | 29,627 | ≤12 |

| *A total of 70% of these cancers are attributable to HPV types 16 or 18. | ||

| †Majority of these cancers are attributable to HPV type 16. | ||

| Sources: US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 2003. Incidence and Mortality. Altanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, and the National Cancer Institute; 2006; Parkin M. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118:3030–3044. | ||

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 55 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004. dougco@u.arizona.edu

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you up to date with new immunization recommendations? J Fam Pract 2006;55:232-234.

2. CDC. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for Use of Tdap Among HealthCare Personnel. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005;55(RR-17):1-33.

3. CDC. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: Immunization of Adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-16):1-25.

4. CDC. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-12):1-13.

5. CDC. Quadrivalent human papilloma virus vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2007;56(RR-2):1-24.

6. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 2007;297:813-819.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you up to date with new immunization recommendations? J Fam Pract 2006;55:232-234.

2. CDC. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for Use of Tdap Among HealthCare Personnel. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005;55(RR-17):1-33.

3. CDC. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: Immunization of Adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-16):1-25.

4. CDC. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-12):1-13.

5. CDC. Quadrivalent human papilloma virus vaccine. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2007;56(RR-2):1-24.

6. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 2007;297:813-819.

Time to revise your HIV testing routine

The CDC now recommends that clinicians:

- Do HIV testing in all health care settings after the patient is notified that testing will be performed (unless the patient declines).

- Test high-risk patients annually.

- Discontinue use of a separate written consent for HIV testing, if allowed by state law. General consent for medical care should be considered sufficient.

- Drop the requirement that prevention counseling be conducted with HIV testing.

- Include HIV testing in the routine panel of prenatal screening tests for all pregnant women.

- Perform a repeat test on women in their third trimester in regions with elevated rates of HIV infection among pregnant women.

Should all adults and adolescents be screened for HIV? Do all persons at high risk deserve annual screening? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thinks so, but the US Preventive Services Task Force takes a less aggressive stance. The 2 agencies looked at the evidence and interpreted it differently—and likewise we must each decide what is best for our own patients and community.

Routine screening is one of several recently revised recommendations from the CDC (at right).1 Though the CDC has historically taken a cautious approach to HIV testing, the winds appear to be changing. The reasons:

- Risk-based screening did not reduce incidence. The previous approach—targeted counseling and testing—has not led to a decline in HIV incidence—it has hovered at around 40,000 cases per year for over a decade.2

- An estimated one fourth of HIV-positive people in the US don’t know their status, and thus are at increased risk of transmitting the disease to others.

- Risk-based screening failed to detect many who are HIV-infected because patients either don’t appreciate—or don’t want to acknowledge—their risks.3,4

- Risk-based screening failed to detect many HIV-infected pregnant women, leading to preventable infection in newborns; routine opt-out testing has been more successful.5

- Highly active antiretroviral therapy has had marked success in reducing mortality from HIV infection. Chemoprophylaxis has proven benefits for preventing certain opportunistic infections.6,7

Removing barriers to testing

The CDC is also advising clinicians that requiring pretest counseling or a separate written consent is a barrier to testing. Clinicians still should inform patients that HIV testing is being conducted and that they have a right to refuse. There is evidence, though, that making the test routine reduces its stigma and increases acceptance.8-11

Evidence also indicates that preventive counseling is very effective in reducing risky behavior among those who are HIV-positive. It’s unclear, however, whether such counseling is effective among those who are HIV-negative.12

Thus, the CDC’s new approach stresses finding those who are infected, getting them medical care, and lowering their risk of transmitting infection to others.

If a pregnant women refuses HIV testing, ask why

The new CDC recommendations take an especially aggressive approach to screening pregnant women, stating that women who refuse testing should be questioned about their reasons for refusal and counseled about the benefits of the test.

The CDC advises repeat testing in the third trimester, in areas of increased risk—which includes 20 states1—and for pregnant women with individual risk factors, as well as those who receive care in facilities with rates of infection of 1 per 1000 women screened. The CDC also urges rapid HIV testing during labor, in women who were not tested during pregnancy, and on newborns whose mothers were not tested during pregnancy or labor.

USPSTF is less aggressive

The USPSTF13 does not recommend for or against testing persons who are not at high risk (TABLE). Both the CDC and the USPSTF recognize that routine screening is probably warranted in populations with HIV prevalence of 1/1000 or greater. However, the CDC recommends routine screening in all settings until there is evidence that the site or population-specific prevalence is lower than this threshold, while the USPSTF simply states that routine screening may be warranted in populations with a prevalence above this level.

TABLE

USPSTF vs CDC recommendations on HIV testing

| GROUP | USPSTF | CDC |

|---|---|---|

| High-risk adolescents | Recommends testing, no frequency mentioned | Recommends annual testing and before starting a new sexual relationship |

| High-risk adults | Recommends testing, no frequency mentioned | Recommends annual testing as well as before starting a new sexual relationship |

| Adolescents not at high risk | No recommendation for or against | Recommends testing, no frequency mentioned, and testing before starting a new sexual relationship. |

| Adults not at high risk | No recommendation for or against | Recommends testing, no frequency mentioned. recommends testing before starting a new sexual relationship. |

| Pregnant women | Recommends testing | Recommends testing at first visit, repeat test in the third trimester in regions with high rates of HIV infection in pregnant women. |

| Written consent | Does not comment about | Recommends against |

The take-away message

It’s time to review both sets of guidelines and adopt HIV testing policies that are most appropriate for your clinical and community situation, and that meet state laws, many of which still require separate written consent and pretest counseling.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 N. Third Street #415, phoenix, AZ 85012. dougco@u.arizona.edu

1. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5514a1.htm. Accessed on March 16, 2007.

2. CDC. US HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 2001. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2001;13(2). Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasr1302.htm. Accessed on March 13, 2007.

3. Institute of Medicine No Time to Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.