User login

Need-to-know information for the 2016-2017 flu season

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) took the unusual step at its June 2016 meeting of recommending against using a currently licensed vaccine, live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), in the 2016-2017 influenza season.1 ACIP based its recommendation on surveillance data collected by the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which showed poor effectiveness by the LAIV vaccine among children and adolescents during the past 3 years.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however, has chosen not to take any action on this matter, saying on its Web site it “has determined that specific regulatory action is not warranted at this time. This determination is based on FDA’s review of manufacturing and clinical data supporting licensure … the totality of the evidence presented at the ACIP meeting, taking into account the inherent limitations of observational studies conducted to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness, as well as the well-known variability of influenza vaccine effectiveness across influenza seasons.”2

CDC data for the 2015-2016 flu season showed the effectiveness of LAIV to be just 3% among children 2 years through 17 years of age.3 The reason for this apparent lack of effectiveness is unknown. Other LAIV-effectiveness studies conducted in the 2015-2016 season—one each, in the United States, United Kingdom, and Finland—had results that differed from the CDC surveillance data, with effectiveness ranging from 46% to 58% against all strains combined.2 These results are comparable to vaccine effectiveness found in observational studies in children for both LAIV and inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV) in prior seasons.2

Vaccine manufacturers had projected that 171 to 176 million doses of flu vaccine, in all forms, would be available in the United States during the 2016-2017 season.3 LAIV accounts for about 8% of the total supply of influenza vaccine in the United States,3 and ACIP’s recommendation is not expected to create shortages of other options for the upcoming season. However, the LAIV accounts for one-third of flu vaccines administered to children, and clinicians who provide vaccinations to children have already ordered their vaccine supplies for the upcoming season. Also, it is not clear if children who have previously received the LAIV product will now accept other options for influenza vaccination—all of which involve an injection.

Whether the recommendation against LAIV will continue after this season is also unknown.

What happened during the 2015-2016 influenza season?

The 2015-2016 influenza season was relatively mild with the peak activity occurring in March, somewhat later than in previous years. The circulating influenza strains matched closely to those in the vaccine, making it more effective than the previous year’s vaccine. The predominant circulating strain was A (H1N1), accounting for 58% of illness; A (H3N2) caused 6% of cases and all B types together accounted for 34%.4 The hospitalization rate for all ages was 31.3/100,000 compared with 64.1 the year before.5 There were 85 pediatric deaths compared with 148 in 2014-2015.6

Vaccine effectiveness among all age groups and against all circulating strains was 47%.4 No major vaccine safety concerns were detected. Among those who received IIV3, there was a slight increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome of 2.6 cases per one million vaccines.7

Other recommendations for 2016-2017

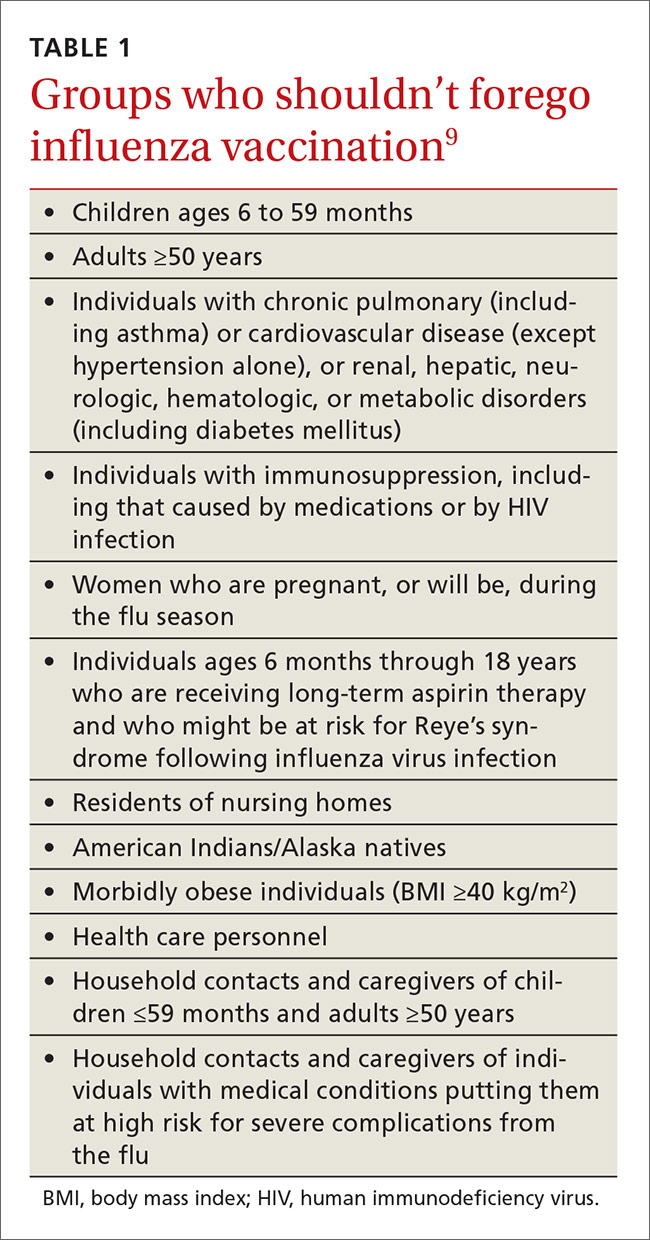

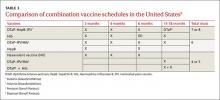

Once again, ACIP recommends influenza vaccine for all individuals 6 months and older.8 The CDC additionally specifies particular groups that should not skip vaccination given that they are at high risk of complications from influenza infection or because they could expose high-risk individuals to infection (TABLE 1).9

There will continue to be a selection of trivalent and quadrivalent influenza vaccine products in 2016-2017. Trivalent products will contain 3 viral strains: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) and B/Brisbane/60/2008.10 The quadrivalent products will contain those 3 antigens plus B/Phuket/3073/2013.10 The H3N2 strain is different from the one in last year’s vaccine. Each year, influenza experts analyze surveillance data to predict which circulating strains will predominate in North America, and these antigens constitute the vaccine formulation. The accuracy of this prediction in large part determines how effective the vaccine will be that season.

Two new vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. A quadrivalent cell culture inactivated vaccine (CCIV4), Flucelvax, was licensed in May 2016. It is prepared from virus propagated in canine kidney cells, not with an egg-based production process. It is approved for use in individuals 4 years of age and older.8 Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, was licensed in late 2015 for individuals 65 years of age and older.8 This is the first adjuvanted influenza vaccine licensed in the United States and will compete with high-dose quadrivalent vaccine for use in older adults. ACIP does not express a preference for any vaccine in this age group.

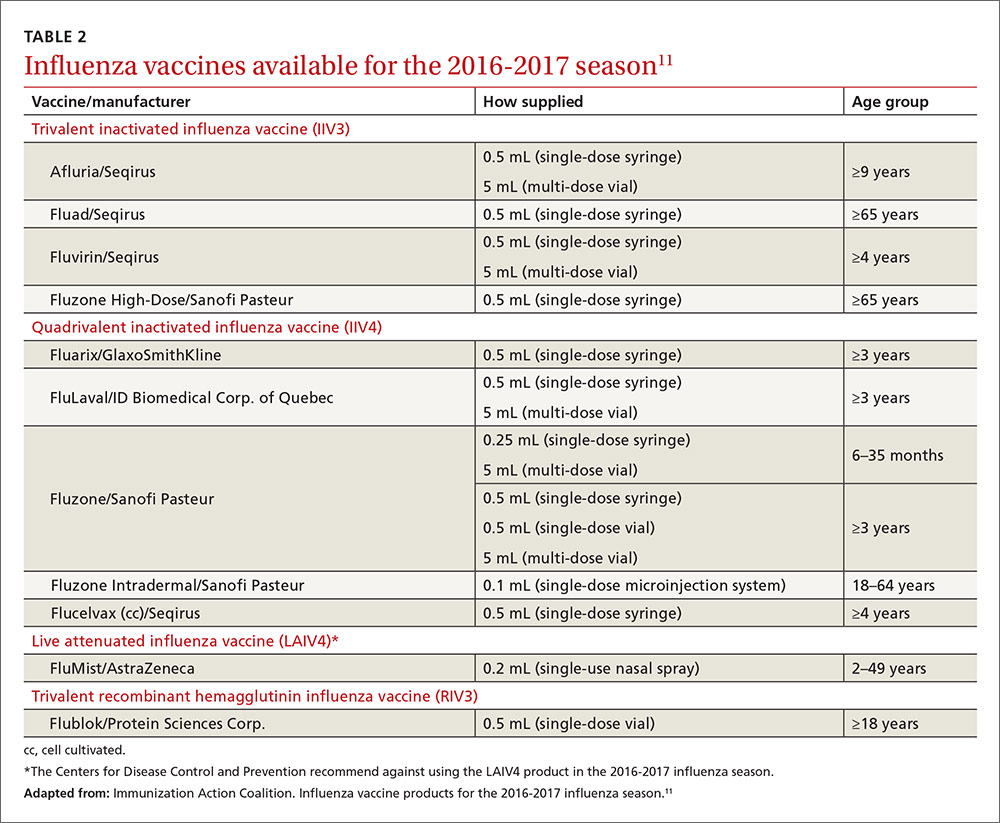

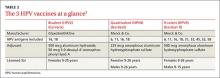

Two other vaccines should also be available by this fall: Flublok, a quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine for individuals 18 years and older, and Flulaval, a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, for individuals 6 months of age and older. TABLE 211 lists approved influenza vaccines.

Issues specific to children

Deciding how many vaccine doses children need has been further simplified. Children younger than 9 years need 2 doses if they have received fewer than 2 doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The interval between the 2 doses should be at least 4 weeks. The 2 doses do not have to be the same product; importantly, do not delay a second dose just to obtain the same product used for the first dose. Also, one dose can be trivalent and the other one quadrivalent, although this offers less-than-optimal protection against the B-virus that is only in the quadrivalent product.

Children younger than 9 years require only one dose if they have received 2 or more total doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The 2 previous doses need not have been received during the same influenza season or consecutive influenza seasons.

In children ages 6 through 23 months there is a slight increased risk of febrile seizure if the influenza vaccine is co-administered with other vaccines, specifically pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 13) and diphtheria-tetanus-acellular-pertussis (DTaP). The 3 vaccines administered at the same time result in 30 febrile seizures per 100,000 children;12 the rate is lower when influenza vaccine is co-administered with only one of the others. ACIP believes that the risk of a febrile seizure, which does no long-term harm, does not warrant delaying vaccines that could be co-administered.13

Egg allergy requires no special precautions

Evidence continues to grow that influenza vaccine products do not contain enough egg protein to cause significant problems in those with a history of egg allergies. This year’s recommendations state that no special precautions are needed regarding the anatomic site of immunization or the length of observation after administering influenza vaccine in those with a history of allergies to eggs, no matter how severe. All vaccine-administration facilities should be able to respond to any hypersensitivity reaction, and the standard waiting time for observation after all vaccinations is 15 minutes.

Antiviral medications for treatment or prevention

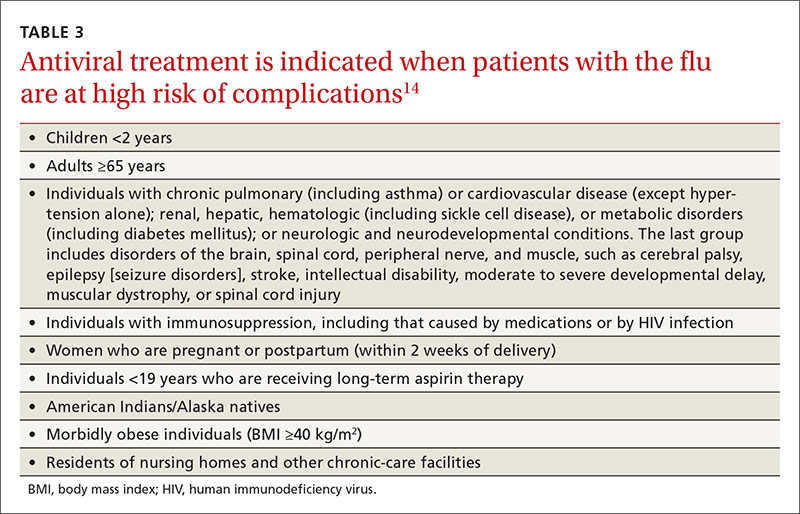

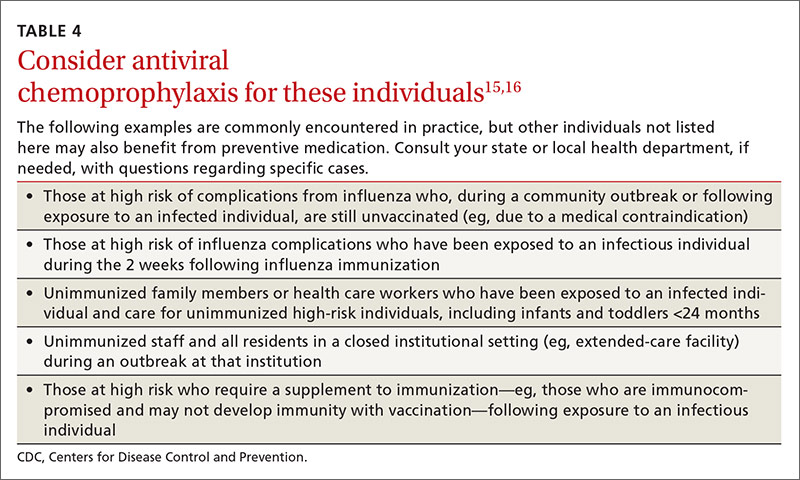

Most influenza strains circulating in 2016-2017 are expected to remain sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir, which can be used for treatment or disease prevention. A third neuraminidase inhibitor, peramivir, is available for intravenous use in adults 18 and older. Treatment is recommended for those who have confirmed or suspected influenza and are at high risk for complications (TABLE 3).14 Consideration of antiviral chemoprevention is recommended under certain circumstances (TABLE 4).15,16 The CDC influenza Web site lists recommended doses and duration for each antiviral for treatment and chemoprevention.15

1. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-54.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA information regarding FluMist quadrivalent vaccine. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm508761.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

4. Flannery B, Chung J. Influenza vaccine effectiveness, including LAIV vs IIV in children and adolescents, US Flu VE Network, 2015-2016. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-05-flannery.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Number of influenza-associated pediatric deaths by week of death. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/PedFluDeath.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

7. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2015-2016 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

8. Grohskopf L. Proposed recommendations 2016-2017 influenza season. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-08-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination: a summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vax-summary.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2016-2017.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

11. Immunization Action Coalition. Influenza vaccine products for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4072.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016.

12. Duffy J, Weintraub E, Hambidge SJ, et al. Febrile seizure risk after vaccination in children 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics. 2016;138.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood vaccines and febrile seizures. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/febrile-seizures.html. Accessed August 11, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of antivirals. Background and guidance on the use of influenza antiviral agents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

16. American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2015-2016. Pediatrics. 2015;136:792-808.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) took the unusual step at its June 2016 meeting of recommending against using a currently licensed vaccine, live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), in the 2016-2017 influenza season.1 ACIP based its recommendation on surveillance data collected by the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which showed poor effectiveness by the LAIV vaccine among children and adolescents during the past 3 years.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however, has chosen not to take any action on this matter, saying on its Web site it “has determined that specific regulatory action is not warranted at this time. This determination is based on FDA’s review of manufacturing and clinical data supporting licensure … the totality of the evidence presented at the ACIP meeting, taking into account the inherent limitations of observational studies conducted to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness, as well as the well-known variability of influenza vaccine effectiveness across influenza seasons.”2

CDC data for the 2015-2016 flu season showed the effectiveness of LAIV to be just 3% among children 2 years through 17 years of age.3 The reason for this apparent lack of effectiveness is unknown. Other LAIV-effectiveness studies conducted in the 2015-2016 season—one each, in the United States, United Kingdom, and Finland—had results that differed from the CDC surveillance data, with effectiveness ranging from 46% to 58% against all strains combined.2 These results are comparable to vaccine effectiveness found in observational studies in children for both LAIV and inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV) in prior seasons.2

Vaccine manufacturers had projected that 171 to 176 million doses of flu vaccine, in all forms, would be available in the United States during the 2016-2017 season.3 LAIV accounts for about 8% of the total supply of influenza vaccine in the United States,3 and ACIP’s recommendation is not expected to create shortages of other options for the upcoming season. However, the LAIV accounts for one-third of flu vaccines administered to children, and clinicians who provide vaccinations to children have already ordered their vaccine supplies for the upcoming season. Also, it is not clear if children who have previously received the LAIV product will now accept other options for influenza vaccination—all of which involve an injection.

Whether the recommendation against LAIV will continue after this season is also unknown.

What happened during the 2015-2016 influenza season?

The 2015-2016 influenza season was relatively mild with the peak activity occurring in March, somewhat later than in previous years. The circulating influenza strains matched closely to those in the vaccine, making it more effective than the previous year’s vaccine. The predominant circulating strain was A (H1N1), accounting for 58% of illness; A (H3N2) caused 6% of cases and all B types together accounted for 34%.4 The hospitalization rate for all ages was 31.3/100,000 compared with 64.1 the year before.5 There were 85 pediatric deaths compared with 148 in 2014-2015.6

Vaccine effectiveness among all age groups and against all circulating strains was 47%.4 No major vaccine safety concerns were detected. Among those who received IIV3, there was a slight increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome of 2.6 cases per one million vaccines.7

Other recommendations for 2016-2017

Once again, ACIP recommends influenza vaccine for all individuals 6 months and older.8 The CDC additionally specifies particular groups that should not skip vaccination given that they are at high risk of complications from influenza infection or because they could expose high-risk individuals to infection (TABLE 1).9

There will continue to be a selection of trivalent and quadrivalent influenza vaccine products in 2016-2017. Trivalent products will contain 3 viral strains: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) and B/Brisbane/60/2008.10 The quadrivalent products will contain those 3 antigens plus B/Phuket/3073/2013.10 The H3N2 strain is different from the one in last year’s vaccine. Each year, influenza experts analyze surveillance data to predict which circulating strains will predominate in North America, and these antigens constitute the vaccine formulation. The accuracy of this prediction in large part determines how effective the vaccine will be that season.

Two new vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. A quadrivalent cell culture inactivated vaccine (CCIV4), Flucelvax, was licensed in May 2016. It is prepared from virus propagated in canine kidney cells, not with an egg-based production process. It is approved for use in individuals 4 years of age and older.8 Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, was licensed in late 2015 for individuals 65 years of age and older.8 This is the first adjuvanted influenza vaccine licensed in the United States and will compete with high-dose quadrivalent vaccine for use in older adults. ACIP does not express a preference for any vaccine in this age group.

Two other vaccines should also be available by this fall: Flublok, a quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine for individuals 18 years and older, and Flulaval, a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, for individuals 6 months of age and older. TABLE 211 lists approved influenza vaccines.

Issues specific to children

Deciding how many vaccine doses children need has been further simplified. Children younger than 9 years need 2 doses if they have received fewer than 2 doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The interval between the 2 doses should be at least 4 weeks. The 2 doses do not have to be the same product; importantly, do not delay a second dose just to obtain the same product used for the first dose. Also, one dose can be trivalent and the other one quadrivalent, although this offers less-than-optimal protection against the B-virus that is only in the quadrivalent product.

Children younger than 9 years require only one dose if they have received 2 or more total doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The 2 previous doses need not have been received during the same influenza season or consecutive influenza seasons.

In children ages 6 through 23 months there is a slight increased risk of febrile seizure if the influenza vaccine is co-administered with other vaccines, specifically pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 13) and diphtheria-tetanus-acellular-pertussis (DTaP). The 3 vaccines administered at the same time result in 30 febrile seizures per 100,000 children;12 the rate is lower when influenza vaccine is co-administered with only one of the others. ACIP believes that the risk of a febrile seizure, which does no long-term harm, does not warrant delaying vaccines that could be co-administered.13

Egg allergy requires no special precautions

Evidence continues to grow that influenza vaccine products do not contain enough egg protein to cause significant problems in those with a history of egg allergies. This year’s recommendations state that no special precautions are needed regarding the anatomic site of immunization or the length of observation after administering influenza vaccine in those with a history of allergies to eggs, no matter how severe. All vaccine-administration facilities should be able to respond to any hypersensitivity reaction, and the standard waiting time for observation after all vaccinations is 15 minutes.

Antiviral medications for treatment or prevention

Most influenza strains circulating in 2016-2017 are expected to remain sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir, which can be used for treatment or disease prevention. A third neuraminidase inhibitor, peramivir, is available for intravenous use in adults 18 and older. Treatment is recommended for those who have confirmed or suspected influenza and are at high risk for complications (TABLE 3).14 Consideration of antiviral chemoprevention is recommended under certain circumstances (TABLE 4).15,16 The CDC influenza Web site lists recommended doses and duration for each antiviral for treatment and chemoprevention.15

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) took the unusual step at its June 2016 meeting of recommending against using a currently licensed vaccine, live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), in the 2016-2017 influenza season.1 ACIP based its recommendation on surveillance data collected by the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which showed poor effectiveness by the LAIV vaccine among children and adolescents during the past 3 years.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), however, has chosen not to take any action on this matter, saying on its Web site it “has determined that specific regulatory action is not warranted at this time. This determination is based on FDA’s review of manufacturing and clinical data supporting licensure … the totality of the evidence presented at the ACIP meeting, taking into account the inherent limitations of observational studies conducted to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness, as well as the well-known variability of influenza vaccine effectiveness across influenza seasons.”2

CDC data for the 2015-2016 flu season showed the effectiveness of LAIV to be just 3% among children 2 years through 17 years of age.3 The reason for this apparent lack of effectiveness is unknown. Other LAIV-effectiveness studies conducted in the 2015-2016 season—one each, in the United States, United Kingdom, and Finland—had results that differed from the CDC surveillance data, with effectiveness ranging from 46% to 58% against all strains combined.2 These results are comparable to vaccine effectiveness found in observational studies in children for both LAIV and inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV) in prior seasons.2

Vaccine manufacturers had projected that 171 to 176 million doses of flu vaccine, in all forms, would be available in the United States during the 2016-2017 season.3 LAIV accounts for about 8% of the total supply of influenza vaccine in the United States,3 and ACIP’s recommendation is not expected to create shortages of other options for the upcoming season. However, the LAIV accounts for one-third of flu vaccines administered to children, and clinicians who provide vaccinations to children have already ordered their vaccine supplies for the upcoming season. Also, it is not clear if children who have previously received the LAIV product will now accept other options for influenza vaccination—all of which involve an injection.

Whether the recommendation against LAIV will continue after this season is also unknown.

What happened during the 2015-2016 influenza season?

The 2015-2016 influenza season was relatively mild with the peak activity occurring in March, somewhat later than in previous years. The circulating influenza strains matched closely to those in the vaccine, making it more effective than the previous year’s vaccine. The predominant circulating strain was A (H1N1), accounting for 58% of illness; A (H3N2) caused 6% of cases and all B types together accounted for 34%.4 The hospitalization rate for all ages was 31.3/100,000 compared with 64.1 the year before.5 There were 85 pediatric deaths compared with 148 in 2014-2015.6

Vaccine effectiveness among all age groups and against all circulating strains was 47%.4 No major vaccine safety concerns were detected. Among those who received IIV3, there was a slight increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome of 2.6 cases per one million vaccines.7

Other recommendations for 2016-2017

Once again, ACIP recommends influenza vaccine for all individuals 6 months and older.8 The CDC additionally specifies particular groups that should not skip vaccination given that they are at high risk of complications from influenza infection or because they could expose high-risk individuals to infection (TABLE 1).9

There will continue to be a selection of trivalent and quadrivalent influenza vaccine products in 2016-2017. Trivalent products will contain 3 viral strains: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2) and B/Brisbane/60/2008.10 The quadrivalent products will contain those 3 antigens plus B/Phuket/3073/2013.10 The H3N2 strain is different from the one in last year’s vaccine. Each year, influenza experts analyze surveillance data to predict which circulating strains will predominate in North America, and these antigens constitute the vaccine formulation. The accuracy of this prediction in large part determines how effective the vaccine will be that season.

Two new vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. A quadrivalent cell culture inactivated vaccine (CCIV4), Flucelvax, was licensed in May 2016. It is prepared from virus propagated in canine kidney cells, not with an egg-based production process. It is approved for use in individuals 4 years of age and older.8 Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, was licensed in late 2015 for individuals 65 years of age and older.8 This is the first adjuvanted influenza vaccine licensed in the United States and will compete with high-dose quadrivalent vaccine for use in older adults. ACIP does not express a preference for any vaccine in this age group.

Two other vaccines should also be available by this fall: Flublok, a quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine for individuals 18 years and older, and Flulaval, a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine, for individuals 6 months of age and older. TABLE 211 lists approved influenza vaccines.

Issues specific to children

Deciding how many vaccine doses children need has been further simplified. Children younger than 9 years need 2 doses if they have received fewer than 2 doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The interval between the 2 doses should be at least 4 weeks. The 2 doses do not have to be the same product; importantly, do not delay a second dose just to obtain the same product used for the first dose. Also, one dose can be trivalent and the other one quadrivalent, although this offers less-than-optimal protection against the B-virus that is only in the quadrivalent product.

Children younger than 9 years require only one dose if they have received 2 or more total doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2016. The 2 previous doses need not have been received during the same influenza season or consecutive influenza seasons.

In children ages 6 through 23 months there is a slight increased risk of febrile seizure if the influenza vaccine is co-administered with other vaccines, specifically pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV 13) and diphtheria-tetanus-acellular-pertussis (DTaP). The 3 vaccines administered at the same time result in 30 febrile seizures per 100,000 children;12 the rate is lower when influenza vaccine is co-administered with only one of the others. ACIP believes that the risk of a febrile seizure, which does no long-term harm, does not warrant delaying vaccines that could be co-administered.13

Egg allergy requires no special precautions

Evidence continues to grow that influenza vaccine products do not contain enough egg protein to cause significant problems in those with a history of egg allergies. This year’s recommendations state that no special precautions are needed regarding the anatomic site of immunization or the length of observation after administering influenza vaccine in those with a history of allergies to eggs, no matter how severe. All vaccine-administration facilities should be able to respond to any hypersensitivity reaction, and the standard waiting time for observation after all vaccinations is 15 minutes.

Antiviral medications for treatment or prevention

Most influenza strains circulating in 2016-2017 are expected to remain sensitive to oseltamivir and zanamivir, which can be used for treatment or disease prevention. A third neuraminidase inhibitor, peramivir, is available for intravenous use in adults 18 and older. Treatment is recommended for those who have confirmed or suspected influenza and are at high risk for complications (TABLE 3).14 Consideration of antiviral chemoprevention is recommended under certain circumstances (TABLE 4).15,16 The CDC influenza Web site lists recommended doses and duration for each antiviral for treatment and chemoprevention.15

1. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-54.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA information regarding FluMist quadrivalent vaccine. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm508761.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

4. Flannery B, Chung J. Influenza vaccine effectiveness, including LAIV vs IIV in children and adolescents, US Flu VE Network, 2015-2016. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-05-flannery.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Number of influenza-associated pediatric deaths by week of death. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/PedFluDeath.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

7. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2015-2016 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

8. Grohskopf L. Proposed recommendations 2016-2017 influenza season. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-08-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination: a summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vax-summary.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2016-2017.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

11. Immunization Action Coalition. Influenza vaccine products for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4072.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016.

12. Duffy J, Weintraub E, Hambidge SJ, et al. Febrile seizure risk after vaccination in children 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics. 2016;138.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood vaccines and febrile seizures. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/febrile-seizures.html. Accessed August 11, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of antivirals. Background and guidance on the use of influenza antiviral agents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

16. American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2015-2016. Pediatrics. 2015;136:792-808.

1. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2016-17 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-54.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA information regarding FluMist quadrivalent vaccine. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm508761.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016-2017 flu season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

4. Flannery B, Chung J. Influenza vaccine effectiveness, including LAIV vs IIV in children and adolescents, US Flu VE Network, 2015-2016. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-05-flannery.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView. Number of influenza-associated pediatric deaths by week of death. Available at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/PedFluDeath.html. Accessed July 25, 2016.

7. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2015-2016 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

8. Grohskopf L. Proposed recommendations 2016-2017 influenza season. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/influenza-08-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2016.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination: a summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/vax-summary.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2016-2017.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

11. Immunization Action Coalition. Influenza vaccine products for the 2016-2017 influenza season. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4072.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016.

12. Duffy J, Weintraub E, Hambidge SJ, et al. Febrile seizure risk after vaccination in children 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics. 2016;138.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood vaccines and febrile seizures. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/febrile-seizures.html. Accessed August 11, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of antivirals. Background and guidance on the use of influenza antiviral agents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed July 13, 2016.

16. American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2015-2016. Pediatrics. 2015;136:792-808.

Colorectal cancer screening: The USPSTF’s final word

USPSTF update: Screening for abnormal blood glucose, diabetes

In December 2015, the United States Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation on screening for abnormal blood glucose and diabetes to say that clinicians should screen all adults ages 40 to 70 years who are overweight or obese as part of a cardiovascular risk assessment.1 This recommendation carries a B grade signifying a moderate certainty that a moderate net benefit will be gained by detecting impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or diabetes, and by implementing intensive lifestyle interventions. In this article, as in the Task Force recommendation, the term diabetes means type 2 diabetes. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, and overweight as a BMI >25.

How the Task Force recommendation evolved

The previous Task Force recommendation on this topic, made in 2008, advised screening only adults with hypertension because there was no evidence that any other group benefited from screening. In subsequent years, there were calls for the Task Force to revise its recommendation to bring it more in line with that of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).2 While this new recommendation does add more adults to the cohort of those the Task Force believes should be screened, it is still not totally in concert with the ADA, which recommends screening all adults 45 years or older and those who are younger if they have multiple risk factors.3

Both the Task Force and the ADA acknowledge there is no direct evidence for any benefit in screening for diabetes in the general, asymptomatic population. The Task Force, with its standard of making recommendations only when good evidence supports them, has opted to address screening for abnormal glucose levels in the context of cardiovascular risk reduction and persuasive evidence that lifestyle interventions can reduce cardiovascular risks and slow progression to diabetes.

The ADA is willing to rely on less rigorous evidence of benefit in screening, diagnosing, and treating undetected diabetes. It believes that morbidity and mortality from this pervasive chronic disease can be reduced with early detection and treatment.

Still the Task Force and ADA agree more than they differ

While it appears that significant differences exist between the recommendations of the Task Force and the ADA, a closer look shows they actually have much in common; and, as they pertain to daily practice, any remaining differences are primarily ones of emphasis. For instance, the Clinical Considerations section of the Task Force recommendation acknowledges that certain people are at increased risk for diabetes at younger ages and at a lower BMI, and that clinicians should “consider” screening them earlier than at age 40 years. The risks listed include a family history of diabetes or a personal history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome; or being African American, Hispanic, Asian American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian.

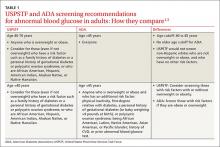

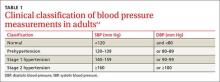

The Task Force statement seems to imply—although this is not entirely clear—that those who have these risks should also be screened if they are older than age 40 years even if they are not obese. So, although the ADA would screen everyone ages 45 and older, the Task Force would screen everyone ages 40 and older, except for non-Hispanic whites who are not overweight or obese, and who have no other risk factors. TABLE 11,3 details the Task Force and the ADA screening criteria and how they differ.

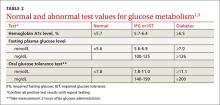

The Task Force and the ADA also agree on the 3 tests acceptable for screening and the test values that define normal glucose, IGT, IFG, and diabetes (TABLE 2).1,3 The tests are a randomly measured glycated hemoglobin level, a fasting plasma glucose level, and an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the morning after an overnight fast, with glucose measured 2 hours after a 75-g oral glucose load. If a screening result is abnormal, confirmation should be sought by repeating the same test. And both organizations suggest that, following a normal test result, the optimal interval for retesting is 3 years.

Intervening to delay progression to diabetes

For anyone with a confirmed abnormal blood glucose level, the Task Force advises referral for intensive behavioral interventions—ie, multiple counseling sessions over an extended period on a healthy diet and optimal physical activity. These types of interventions can reduce blood glucose levels and lower the risk of progression to diabetes, and can help with lowering weight, blood pressure, and lipid levels. The evidence report that preceded the recommendation pooled the results from 10 studies on lifestyle modification.4 The length of follow-up in these studies ranged from 3 to 23 years, and the number needed to treat to prevent one case of progression to diabetes ranged from about 5 to 20.4

Medications such as metformin, thiazolidinediones, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors can also reduce blood glucose levels and slow progression to diabetes. However, the Task Force says there is insufficient evidence that pharmacologic interventions have the same multifactorial benefits—weight loss or reductions in glucose levels, blood pressure, and lipid levels—as behavioral interventions.1

As for the other modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease—obesity, lack of physical activity, high lipid levels, high blood pressure, and smoking—the Task Force has developed recommendations on screening for and treating each of them,5 which supplement the recommendations discussed in this article.

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed May 20, 2016.

2. Casagrande SS, Cowie CC, Fradkin JE. Utility of the US Preventive Services Task Force criteria for diabetes screening. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:167-174.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1–S112.

4. Selph S, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. A systematic review to update the 2008 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality]. 2015. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293871/. Accessed May 20, 2016.

5. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/healthy-diet-and-physical-activity-counseling-adults-with-high-risk-of-cvd. Accessed May 20,

2016.

In December 2015, the United States Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation on screening for abnormal blood glucose and diabetes to say that clinicians should screen all adults ages 40 to 70 years who are overweight or obese as part of a cardiovascular risk assessment.1 This recommendation carries a B grade signifying a moderate certainty that a moderate net benefit will be gained by detecting impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or diabetes, and by implementing intensive lifestyle interventions. In this article, as in the Task Force recommendation, the term diabetes means type 2 diabetes. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, and overweight as a BMI >25.

How the Task Force recommendation evolved

The previous Task Force recommendation on this topic, made in 2008, advised screening only adults with hypertension because there was no evidence that any other group benefited from screening. In subsequent years, there were calls for the Task Force to revise its recommendation to bring it more in line with that of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).2 While this new recommendation does add more adults to the cohort of those the Task Force believes should be screened, it is still not totally in concert with the ADA, which recommends screening all adults 45 years or older and those who are younger if they have multiple risk factors.3

Both the Task Force and the ADA acknowledge there is no direct evidence for any benefit in screening for diabetes in the general, asymptomatic population. The Task Force, with its standard of making recommendations only when good evidence supports them, has opted to address screening for abnormal glucose levels in the context of cardiovascular risk reduction and persuasive evidence that lifestyle interventions can reduce cardiovascular risks and slow progression to diabetes.

The ADA is willing to rely on less rigorous evidence of benefit in screening, diagnosing, and treating undetected diabetes. It believes that morbidity and mortality from this pervasive chronic disease can be reduced with early detection and treatment.

Still the Task Force and ADA agree more than they differ

While it appears that significant differences exist between the recommendations of the Task Force and the ADA, a closer look shows they actually have much in common; and, as they pertain to daily practice, any remaining differences are primarily ones of emphasis. For instance, the Clinical Considerations section of the Task Force recommendation acknowledges that certain people are at increased risk for diabetes at younger ages and at a lower BMI, and that clinicians should “consider” screening them earlier than at age 40 years. The risks listed include a family history of diabetes or a personal history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome; or being African American, Hispanic, Asian American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian.

The Task Force statement seems to imply—although this is not entirely clear—that those who have these risks should also be screened if they are older than age 40 years even if they are not obese. So, although the ADA would screen everyone ages 45 and older, the Task Force would screen everyone ages 40 and older, except for non-Hispanic whites who are not overweight or obese, and who have no other risk factors. TABLE 11,3 details the Task Force and the ADA screening criteria and how they differ.

The Task Force and the ADA also agree on the 3 tests acceptable for screening and the test values that define normal glucose, IGT, IFG, and diabetes (TABLE 2).1,3 The tests are a randomly measured glycated hemoglobin level, a fasting plasma glucose level, and an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the morning after an overnight fast, with glucose measured 2 hours after a 75-g oral glucose load. If a screening result is abnormal, confirmation should be sought by repeating the same test. And both organizations suggest that, following a normal test result, the optimal interval for retesting is 3 years.

Intervening to delay progression to diabetes

For anyone with a confirmed abnormal blood glucose level, the Task Force advises referral for intensive behavioral interventions—ie, multiple counseling sessions over an extended period on a healthy diet and optimal physical activity. These types of interventions can reduce blood glucose levels and lower the risk of progression to diabetes, and can help with lowering weight, blood pressure, and lipid levels. The evidence report that preceded the recommendation pooled the results from 10 studies on lifestyle modification.4 The length of follow-up in these studies ranged from 3 to 23 years, and the number needed to treat to prevent one case of progression to diabetes ranged from about 5 to 20.4

Medications such as metformin, thiazolidinediones, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors can also reduce blood glucose levels and slow progression to diabetes. However, the Task Force says there is insufficient evidence that pharmacologic interventions have the same multifactorial benefits—weight loss or reductions in glucose levels, blood pressure, and lipid levels—as behavioral interventions.1

As for the other modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease—obesity, lack of physical activity, high lipid levels, high blood pressure, and smoking—the Task Force has developed recommendations on screening for and treating each of them,5 which supplement the recommendations discussed in this article.

In December 2015, the United States Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation on screening for abnormal blood glucose and diabetes to say that clinicians should screen all adults ages 40 to 70 years who are overweight or obese as part of a cardiovascular risk assessment.1 This recommendation carries a B grade signifying a moderate certainty that a moderate net benefit will be gained by detecting impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or diabetes, and by implementing intensive lifestyle interventions. In this article, as in the Task Force recommendation, the term diabetes means type 2 diabetes. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, and overweight as a BMI >25.

How the Task Force recommendation evolved

The previous Task Force recommendation on this topic, made in 2008, advised screening only adults with hypertension because there was no evidence that any other group benefited from screening. In subsequent years, there were calls for the Task Force to revise its recommendation to bring it more in line with that of the American Diabetes Association (ADA).2 While this new recommendation does add more adults to the cohort of those the Task Force believes should be screened, it is still not totally in concert with the ADA, which recommends screening all adults 45 years or older and those who are younger if they have multiple risk factors.3

Both the Task Force and the ADA acknowledge there is no direct evidence for any benefit in screening for diabetes in the general, asymptomatic population. The Task Force, with its standard of making recommendations only when good evidence supports them, has opted to address screening for abnormal glucose levels in the context of cardiovascular risk reduction and persuasive evidence that lifestyle interventions can reduce cardiovascular risks and slow progression to diabetes.

The ADA is willing to rely on less rigorous evidence of benefit in screening, diagnosing, and treating undetected diabetes. It believes that morbidity and mortality from this pervasive chronic disease can be reduced with early detection and treatment.

Still the Task Force and ADA agree more than they differ

While it appears that significant differences exist between the recommendations of the Task Force and the ADA, a closer look shows they actually have much in common; and, as they pertain to daily practice, any remaining differences are primarily ones of emphasis. For instance, the Clinical Considerations section of the Task Force recommendation acknowledges that certain people are at increased risk for diabetes at younger ages and at a lower BMI, and that clinicians should “consider” screening them earlier than at age 40 years. The risks listed include a family history of diabetes or a personal history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome; or being African American, Hispanic, Asian American, American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian.

The Task Force statement seems to imply—although this is not entirely clear—that those who have these risks should also be screened if they are older than age 40 years even if they are not obese. So, although the ADA would screen everyone ages 45 and older, the Task Force would screen everyone ages 40 and older, except for non-Hispanic whites who are not overweight or obese, and who have no other risk factors. TABLE 11,3 details the Task Force and the ADA screening criteria and how they differ.

The Task Force and the ADA also agree on the 3 tests acceptable for screening and the test values that define normal glucose, IGT, IFG, and diabetes (TABLE 2).1,3 The tests are a randomly measured glycated hemoglobin level, a fasting plasma glucose level, and an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the morning after an overnight fast, with glucose measured 2 hours after a 75-g oral glucose load. If a screening result is abnormal, confirmation should be sought by repeating the same test. And both organizations suggest that, following a normal test result, the optimal interval for retesting is 3 years.

Intervening to delay progression to diabetes

For anyone with a confirmed abnormal blood glucose level, the Task Force advises referral for intensive behavioral interventions—ie, multiple counseling sessions over an extended period on a healthy diet and optimal physical activity. These types of interventions can reduce blood glucose levels and lower the risk of progression to diabetes, and can help with lowering weight, blood pressure, and lipid levels. The evidence report that preceded the recommendation pooled the results from 10 studies on lifestyle modification.4 The length of follow-up in these studies ranged from 3 to 23 years, and the number needed to treat to prevent one case of progression to diabetes ranged from about 5 to 20.4

Medications such as metformin, thiazolidinediones, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors can also reduce blood glucose levels and slow progression to diabetes. However, the Task Force says there is insufficient evidence that pharmacologic interventions have the same multifactorial benefits—weight loss or reductions in glucose levels, blood pressure, and lipid levels—as behavioral interventions.1

As for the other modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease—obesity, lack of physical activity, high lipid levels, high blood pressure, and smoking—the Task Force has developed recommendations on screening for and treating each of them,5 which supplement the recommendations discussed in this article.

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed May 20, 2016.

2. Casagrande SS, Cowie CC, Fradkin JE. Utility of the US Preventive Services Task Force criteria for diabetes screening. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:167-174.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1–S112.

4. Selph S, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. A systematic review to update the 2008 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality]. 2015. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293871/. Accessed May 20, 2016.

5. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/healthy-diet-and-physical-activity-counseling-adults-with-high-risk-of-cvd. Accessed May 20,

2016.

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed May 20, 2016.

2. Casagrande SS, Cowie CC, Fradkin JE. Utility of the US Preventive Services Task Force criteria for diabetes screening. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:167-174.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1–S112.

4. Selph S, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. A systematic review to update the 2008 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality]. 2015. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293871/. Accessed May 20, 2016.

5. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/healthy-diet-and-physical-activity-counseling-adults-with-high-risk-of-cvd. Accessed May 20,

2016.

The resurgence of syphilis: New USPSTF screening recommendations

8 USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about

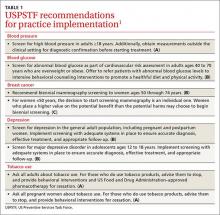

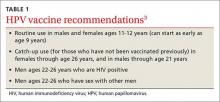

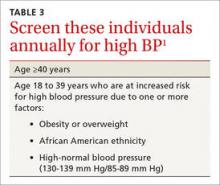

The US Preventive Services Task Force made 8 recommendations in 2015 that family physicians should implement in their practices (TABLE 11). The conditions addressed are high blood pressure, abnormal blood glucose, breast cancer, depression, and tobacco use. The Task Force also issued 13 “I” statements (TABLE 21) reflecting insufficient evidence to recommend for or against a particular intervention—once again underscoring the inadequate evidence base for many commonly-accepted practices aimed at prevention. Four such interventions were targeted toward children.

High blood pressure: Verify before starting treatment

The Task Force continues to give strong backing to the practice of screening for high blood pressure (HBP) and treating those with HBP to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease. The new recommendation, however, recognizes there is significant over-diagnosis of this condition and advises that, before starting treatment, HBP found with office measurement be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring. This topic was covered in more depth in a recent Practice Alert.2

Since cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and much of this mortality is preventable, the Task Force also has recommendations in place for screening and treatment of other risks for cardiovascular disease, including obesity, hyperlipidemia, elevated blood glucose (discussed below), and tobacco use.1

Blood glucose: Focus is now on overweight/obese individuals

The Task Force’s new recommendation for diabetes screening differs from the one made in 2008, which recommended screening for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) only in adults with hypertension. The Task Force now recommends screening for abnormal blood glucose in all obese and overweight adults between the ages of 40 and 70. The Task Force analysis is detailed3 and will be the subject of the next Practice Alert, with only the highlights described here.

The recommendation is limited to overweight and obese adults because they are most likely to have abnormal blood glucose and to benefit from interventions. Screening can be done by measuring fasting blood glucose levels, performing a glucose tolerance test, or measuring glycated hemoglobin levels. The optimal screening frequency is unknown but suggested to be every 3 years. Refer patients with abnormal screen results to an intensive behavioral counseling program that promotes healthy eating and physical activity. Those with T2DM should also receive these services and consider pharmacotherapy.

Breast cancer: Mammography advice is age dependent

The Task Force breast cancer screening recommendations, first proposed in 2015 and finalized in early 2016, essentially reaffirm those made in 2009. Women ages 50 through 74 should be screened with mammography every 2 years, and individuals younger than age 50 should make a decision to receive screening—or not—based on the known benefits and risks of mammography at their age and their personal risks and preferences.

Insufficient evidence exists to make recommendations regarding mammography for women ages 75 and up, the use of digital breast tomosynthesis as a primary screening tool, and the use of any modality to augment screening in women with dense breasts who have normal mammogram results. Details of these recommendations were described in a Practice Alert last year.4

Depression: Use screening tools designed for specific patients

The 2015 updates on screening for depression essentially reconfirm the Task Force’s previous findings and recommendations on this topic. Screening for depression is recommended for all adults, including pregnant and postpartum women,5 and adolescents starting at age 12.6 Once again, the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for depression in children younger than age 12.

Both recommendations emphasize the importance of follow-up steps after screening to ensure accurate diagnosis, adequate treatment, and appropriate follow-up. Treatment for adults and adolescents can include pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and/or psychosocial counseling. However, pharmacotherapy is not recommended for pregnant and breastfeeding women because of potential harms to the fetus and newborn.

The Task Force deems a number of screening tools acceptable. For adolescents, it suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents and the primary care version of the Beck Depression Inventory.6 For adults, the Task Force suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales, the Geriatric Depression Scale for older adults, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for postpartum and pregnant women.5

There is no known optimal frequency of screening or evidence on the value of repeated screening. The Task Force suggests one initial screen with repeated screening based on individual characteristics.

Tobacco use: Ask every adult patient about it

Preventing the harms from tobacco use is one of the most important and productive primary care interventions. The Task Force has affirmed its previous recommendation to ask all adults about tobacco use, encourage those that use tobacco to quit, and to offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions to assist with quitting.7 The new recommendations emphasize the importance of smoking cessation during pregnancy; however, because of concern about the unknown potential harms from pharmacologic interventions, they advise only behavioral therapy to assist pregnant women to quit smoking.

The Task Force also examined the potential of electronic nicotine delivery systems for smoking cessation and concluded the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation. It also concluded that the availability of other proven methods of smoking cessation make them the preferred alternatives.

Services with insufficient evidence

TABLE 21 lists the interventions that the Task Force studied this past year and found insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for or against. For adults, these “I” recommendations include screening for visual acuity disorders in older adults, screening for thyroid disorders, screening for iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy, and routinely providing iron supplementation during pregnancy.

The persistent inadequate evidence for the effectiveness of preventive services in infants and children was highlighted by the results of last year’s examination of 4 screening tests, all recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, but given an “I” recommendation by the Task Force. These included screening for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in young children (18-30 months), iron deficiency anemia in children ages 6 to 24 months, depression in those ages 11 and younger, and speech and language delay and disorders in children ages 5 or younger. (Ages noted are from the Task Force.)

The Task Force is careful to emphasize that the statement about ASD screening refers to infants and children who appear normal and for whom no concerns of ASD have been raised by their parents. Screening all young children for this disorder is problematic, according to the Task Force, because of possible over-diagnosis and unclear benefits of early intervention.8

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Published recommendations. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations. Accessed March 18, 2016.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF urges extra step before treating hypertension. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:41-44.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Abnormal blood glucose and diabetes type 2: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed March 18, 2016.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Breast cancer screening: the latest from the USPSTF. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:407-410.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Depression in adults: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/depression-in-adults-screening1. Accessed March 18, 2016.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Depression in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 18, 2016.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions1. Accessed April 7, 2016.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Autism spectrum disorder in young children: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-young-children-screening. Accessed March 18, 2016.

The US Preventive Services Task Force made 8 recommendations in 2015 that family physicians should implement in their practices (TABLE 11). The conditions addressed are high blood pressure, abnormal blood glucose, breast cancer, depression, and tobacco use. The Task Force also issued 13 “I” statements (TABLE 21) reflecting insufficient evidence to recommend for or against a particular intervention—once again underscoring the inadequate evidence base for many commonly-accepted practices aimed at prevention. Four such interventions were targeted toward children.

High blood pressure: Verify before starting treatment

The Task Force continues to give strong backing to the practice of screening for high blood pressure (HBP) and treating those with HBP to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease. The new recommendation, however, recognizes there is significant over-diagnosis of this condition and advises that, before starting treatment, HBP found with office measurement be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring. This topic was covered in more depth in a recent Practice Alert.2

Since cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and much of this mortality is preventable, the Task Force also has recommendations in place for screening and treatment of other risks for cardiovascular disease, including obesity, hyperlipidemia, elevated blood glucose (discussed below), and tobacco use.1

Blood glucose: Focus is now on overweight/obese individuals

The Task Force’s new recommendation for diabetes screening differs from the one made in 2008, which recommended screening for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) only in adults with hypertension. The Task Force now recommends screening for abnormal blood glucose in all obese and overweight adults between the ages of 40 and 70. The Task Force analysis is detailed3 and will be the subject of the next Practice Alert, with only the highlights described here.

The recommendation is limited to overweight and obese adults because they are most likely to have abnormal blood glucose and to benefit from interventions. Screening can be done by measuring fasting blood glucose levels, performing a glucose tolerance test, or measuring glycated hemoglobin levels. The optimal screening frequency is unknown but suggested to be every 3 years. Refer patients with abnormal screen results to an intensive behavioral counseling program that promotes healthy eating and physical activity. Those with T2DM should also receive these services and consider pharmacotherapy.

Breast cancer: Mammography advice is age dependent

The Task Force breast cancer screening recommendations, first proposed in 2015 and finalized in early 2016, essentially reaffirm those made in 2009. Women ages 50 through 74 should be screened with mammography every 2 years, and individuals younger than age 50 should make a decision to receive screening—or not—based on the known benefits and risks of mammography at their age and their personal risks and preferences.

Insufficient evidence exists to make recommendations regarding mammography for women ages 75 and up, the use of digital breast tomosynthesis as a primary screening tool, and the use of any modality to augment screening in women with dense breasts who have normal mammogram results. Details of these recommendations were described in a Practice Alert last year.4

Depression: Use screening tools designed for specific patients

The 2015 updates on screening for depression essentially reconfirm the Task Force’s previous findings and recommendations on this topic. Screening for depression is recommended for all adults, including pregnant and postpartum women,5 and adolescents starting at age 12.6 Once again, the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for depression in children younger than age 12.

Both recommendations emphasize the importance of follow-up steps after screening to ensure accurate diagnosis, adequate treatment, and appropriate follow-up. Treatment for adults and adolescents can include pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and/or psychosocial counseling. However, pharmacotherapy is not recommended for pregnant and breastfeeding women because of potential harms to the fetus and newborn.

The Task Force deems a number of screening tools acceptable. For adolescents, it suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents and the primary care version of the Beck Depression Inventory.6 For adults, the Task Force suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales, the Geriatric Depression Scale for older adults, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for postpartum and pregnant women.5

There is no known optimal frequency of screening or evidence on the value of repeated screening. The Task Force suggests one initial screen with repeated screening based on individual characteristics.

Tobacco use: Ask every adult patient about it

Preventing the harms from tobacco use is one of the most important and productive primary care interventions. The Task Force has affirmed its previous recommendation to ask all adults about tobacco use, encourage those that use tobacco to quit, and to offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions to assist with quitting.7 The new recommendations emphasize the importance of smoking cessation during pregnancy; however, because of concern about the unknown potential harms from pharmacologic interventions, they advise only behavioral therapy to assist pregnant women to quit smoking.

The Task Force also examined the potential of electronic nicotine delivery systems for smoking cessation and concluded the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation. It also concluded that the availability of other proven methods of smoking cessation make them the preferred alternatives.

Services with insufficient evidence

TABLE 21 lists the interventions that the Task Force studied this past year and found insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for or against. For adults, these “I” recommendations include screening for visual acuity disorders in older adults, screening for thyroid disorders, screening for iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy, and routinely providing iron supplementation during pregnancy.

The persistent inadequate evidence for the effectiveness of preventive services in infants and children was highlighted by the results of last year’s examination of 4 screening tests, all recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, but given an “I” recommendation by the Task Force. These included screening for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in young children (18-30 months), iron deficiency anemia in children ages 6 to 24 months, depression in those ages 11 and younger, and speech and language delay and disorders in children ages 5 or younger. (Ages noted are from the Task Force.)

The Task Force is careful to emphasize that the statement about ASD screening refers to infants and children who appear normal and for whom no concerns of ASD have been raised by their parents. Screening all young children for this disorder is problematic, according to the Task Force, because of possible over-diagnosis and unclear benefits of early intervention.8

The US Preventive Services Task Force made 8 recommendations in 2015 that family physicians should implement in their practices (TABLE 11). The conditions addressed are high blood pressure, abnormal blood glucose, breast cancer, depression, and tobacco use. The Task Force also issued 13 “I” statements (TABLE 21) reflecting insufficient evidence to recommend for or against a particular intervention—once again underscoring the inadequate evidence base for many commonly-accepted practices aimed at prevention. Four such interventions were targeted toward children.

High blood pressure: Verify before starting treatment

The Task Force continues to give strong backing to the practice of screening for high blood pressure (HBP) and treating those with HBP to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease. The new recommendation, however, recognizes there is significant over-diagnosis of this condition and advises that, before starting treatment, HBP found with office measurement be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring. This topic was covered in more depth in a recent Practice Alert.2

Since cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and much of this mortality is preventable, the Task Force also has recommendations in place for screening and treatment of other risks for cardiovascular disease, including obesity, hyperlipidemia, elevated blood glucose (discussed below), and tobacco use.1

Blood glucose: Focus is now on overweight/obese individuals

The Task Force’s new recommendation for diabetes screening differs from the one made in 2008, which recommended screening for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) only in adults with hypertension. The Task Force now recommends screening for abnormal blood glucose in all obese and overweight adults between the ages of 40 and 70. The Task Force analysis is detailed3 and will be the subject of the next Practice Alert, with only the highlights described here.

The recommendation is limited to overweight and obese adults because they are most likely to have abnormal blood glucose and to benefit from interventions. Screening can be done by measuring fasting blood glucose levels, performing a glucose tolerance test, or measuring glycated hemoglobin levels. The optimal screening frequency is unknown but suggested to be every 3 years. Refer patients with abnormal screen results to an intensive behavioral counseling program that promotes healthy eating and physical activity. Those with T2DM should also receive these services and consider pharmacotherapy.

Breast cancer: Mammography advice is age dependent

The Task Force breast cancer screening recommendations, first proposed in 2015 and finalized in early 2016, essentially reaffirm those made in 2009. Women ages 50 through 74 should be screened with mammography every 2 years, and individuals younger than age 50 should make a decision to receive screening—or not—based on the known benefits and risks of mammography at their age and their personal risks and preferences.

Insufficient evidence exists to make recommendations regarding mammography for women ages 75 and up, the use of digital breast tomosynthesis as a primary screening tool, and the use of any modality to augment screening in women with dense breasts who have normal mammogram results. Details of these recommendations were described in a Practice Alert last year.4

Depression: Use screening tools designed for specific patients

The 2015 updates on screening for depression essentially reconfirm the Task Force’s previous findings and recommendations on this topic. Screening for depression is recommended for all adults, including pregnant and postpartum women,5 and adolescents starting at age 12.6 Once again, the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for depression in children younger than age 12.

Both recommendations emphasize the importance of follow-up steps after screening to ensure accurate diagnosis, adequate treatment, and appropriate follow-up. Treatment for adults and adolescents can include pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and/or psychosocial counseling. However, pharmacotherapy is not recommended for pregnant and breastfeeding women because of potential harms to the fetus and newborn.

The Task Force deems a number of screening tools acceptable. For adolescents, it suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents and the primary care version of the Beck Depression Inventory.6 For adults, the Task Force suggests the Patient Health Questionnaire, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales, the Geriatric Depression Scale for older adults, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for postpartum and pregnant women.5

There is no known optimal frequency of screening or evidence on the value of repeated screening. The Task Force suggests one initial screen with repeated screening based on individual characteristics.

Tobacco use: Ask every adult patient about it

Preventing the harms from tobacco use is one of the most important and productive primary care interventions. The Task Force has affirmed its previous recommendation to ask all adults about tobacco use, encourage those that use tobacco to quit, and to offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions to assist with quitting.7 The new recommendations emphasize the importance of smoking cessation during pregnancy; however, because of concern about the unknown potential harms from pharmacologic interventions, they advise only behavioral therapy to assist pregnant women to quit smoking.