User login

Validation of a multidisciplinary infrastructure to capture adverse events in a high-volume endoscopy unit

This month’s article concerns postprocedure complications, a topic of increasing importance as we move to “value-based” reimbursement. Most practices and health systems do not have a routine process to identify complications and we have underestimated them in the past. In the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Final Rule (published in the Federal Register November 2014 – entitled CMS-1613-FC) a new measure for both the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and the Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting Program was described. Beginning in calendar year 2018, measure OP-32 will be Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate after Outpatient Colonoscopy and will be required for submission to CMS. Thus, our endoscopy units will need to understand how they might measure and reduce postprocedure complications. Dr. Francis and her colleagues have given us a choice of methods to collect such information.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Safety is one of the most important determinants of quality in endoscopy and adverse event tracking is an effective way to monitor the safety of a procedural practice.1 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)/American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy recommends the use of a formal protocol for tracking adverse events,2,3 but provides little guidance about how this can be accomplished successfully.

Adverse events have costs associated with them. There is the real human cost of pain and suffering, but there are health care utilization costs as well. As such, adverse event rates are one outcome measure that could be part of the definition of value for a practice4 and likely will play a role in value-based purchasing.

Tracking adverse events is challenging. The best way to track adverse events might be via direct contact with the patient at a postprocedure interval beyond the window of time when an adverse event could take place, but not so remote as to hamper memory of an event.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Many authorities consider this the gold standard for event identification, but it is difficult to accomplish because it requires dedicated personnel and resources. An alternative, low-cost, sustainable means for identifying adverse events that approximates the data from direct patient contact would be attractive.

Such a program might require an infrastructure encompassing a variety of different reporting mechanisms to compensate for the lack of direct patient contact and the limitations of any individual form of reporting.14 For example, a process that relies solely on reporting from within the health care system that performed the procedure is limited to identifying patients who return to the same system for care of an adverse event. For our referral center, such a unimodal approach could miss a significant proportion of events because many of our patients live outside of our local-regional catchment area. Likewise, a system that relies solely on voluntary reporting by health care providers is limited by the providers having the time and inclination to consistently report adverse events when they encounter them.

With these issues in mind, our Gastroenterology Quality Committee created a multidisciplinary infrastructure (MDI) to track adverse events associated with our endoscopic practice. Our infrastructure uses the following. First, endoscopy nurse reporting of adverse events during or immediately after gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Our nursing staff have paper reporting cards and a voice mail event line, both of which can be used to report anything they believe is an adverse event to our Gastroenterology Quality Office. Second, an institutional website link that can be used by any health care worker in our system to electronically report an adverse event. Third, weekly electronic reminders to report adverse events that are sent to all physicians (attendings and fellows) assigned to hospital duties for gastroenterology services. Fourth, an endoscopic complication card provided to all patients at the time of their endoscopy for them to return (in a business reply envelope) if they experience an adverse event (Figure 1: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). Fifth, an automated reporting system that identifies all patients who are admitted, for any reason, to our hospitals within 7 days of an endoscopic procedure. This process does not identify emergency room visits that do not result in a hospital admission.

Although we assumed our MDI used to track adverse events was robust, it had not been validated with another method. Our objective was to validate our MDI process of capturing adverse events by comparing it with direct patient contact via telephone.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minn.). We performed a prospective study to compare two mechanisms for identifying the number, type, and severity of adverse events associated with all types of inpatient and outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures.

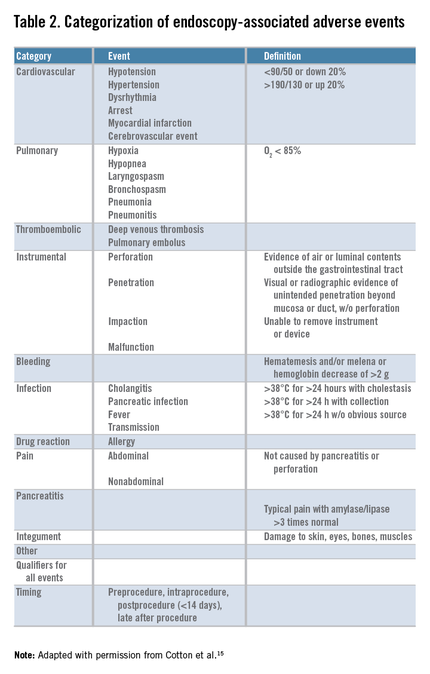

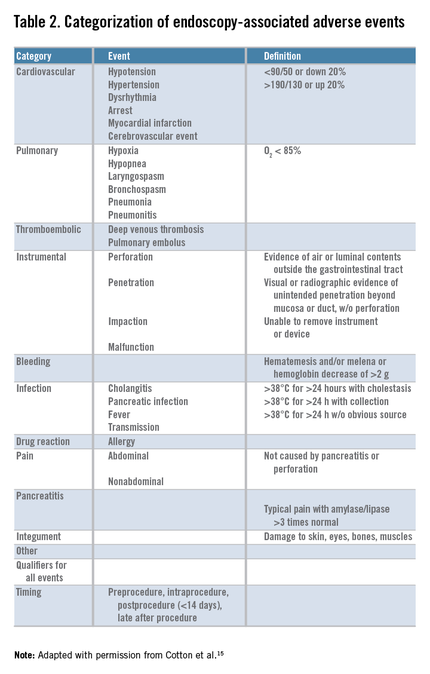

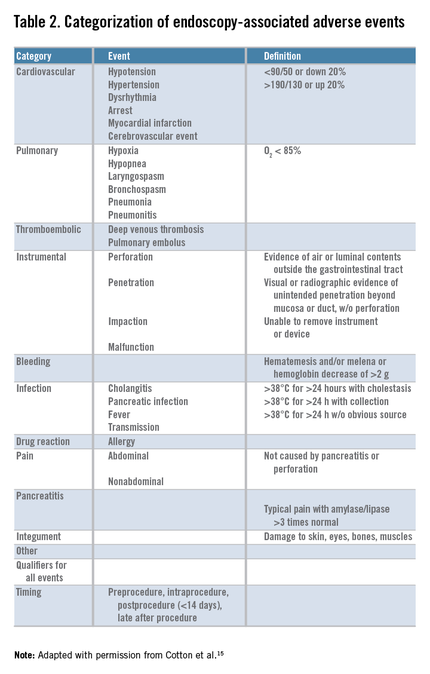

We first initiated enhanced tracking of endoscopic adverse events in 2008, using a multimodal infrastructure that has matured since then to include the variety of sources outlined earlier. Based on the lexicon for endoscopic adverse events proposed by a recent ASGE workgroup,15 we consider an adverse event to be one that prevents the completion of the planned procedure and/or results in another procedure, subsequent medical consultation or admission to the hospital, or prolongation of an existing hospital stay. This includes obvious complications such as perforation, postpolypectomy bleeding, and post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. It also includes some less obvious situations, such as bleeding severe enough to prompt the patient to seek medical care even if an intervention is not required, and abdominal pain that leads a patient to be admitted to the hospital even if a source of pain is not identified. We also used the same group’s recommendations for grading their severity and categorizing the events (Table 1, Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext).15

In the comparative study we then attempted to contact patients by telephone who had an endoscopic procedure performed between July 26, 2011, and December 29, 2011. Three full-time study personnel contacted patients between 14 and 90 days after their procedure to inquire about adverse events that may have resulted from endoscopy. During this time, we continued our existing MDI for tracking adverse events. Events considered adverse were those plausibly associated with the procedure and severe enough for the patient to seek medical attention.

Patient contact

Our research personnel attempted to contact, by telephone, patients who had a gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure in one of our endoscopy units after at least 14 and no more than 90 days to inquire about the occurrence of adverse events. A scripted interview (Appendix A: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext) was used and calls were made only during business hours (between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.).

Our institution uses strict guidelines for patient contact. When a telephone call is not answered, our personnel may only leave a message stating that they are calling from the Mayo Clinic and provide a telephone number for a return call. They are not allowed to say what the call is regarding. Study personnel may make only three telephone calls before they must stop attempts to contact a patient.

Written consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board, so once a patient was contacted they could consent and be interviewed over the telephone. However, to include their information participants were required to return a signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) consent form. Without receiving a signed HIPAA consent form, the data collected for inclusion in the study could not be used.

Sample size calculation

Complications from gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures are rare events. For the purposes of our study, we believed it was important to find even small differences in the ability of the two modalities to identify adverse events. We powered this study to detect a 5% difference between the two capture mechanisms, which required a sample size of 9,894 procedures.

Statistical analysis

We compared the proportion of patients with adverse events as well as the type and severity of the events associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy, as identified by direct patient contact by telephone, with the proportion, type, and severity of events identified through our MDI, using the chi-square statistic for larger sample sizes (e.g., the proportion of overall adverse events in each tracking mechanism group) and the Fisher exact test for smaller sample sizes (e.g., comparing the type of adverse event in each tracking mechanism group). We used both an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis.

Costs

The study was funded by an ASGE research grant for $60,000. A total of $55,000 was spent on study personnel salary and benefits, and the sole responsibility of the study personnel was to contact patients by telephone. As stated previously, three full-time personnel contacted patients by telephone to query them about adverse events every business day for 5 months. The remaining $5000 was spent on statistical design, data entry and analysis, and administration of the study personnel.

The MDI arm of the study already was integrated into the practice. The nurse reporting was part of the job description for our nursing staff and did not require any extra hours or personnel. This also was true for physician reporting. The institutional website link and weekly electronic reminders were put into place by a medical secretary and did not require additional salary support. We estimate that it took an hour of secretarial time to create the website link and to set up weekly e-mail reminders to staff. The endoscopic complication cards that were given to all patients and returned by some of the patients cost $968 during the study period. The automated process for hospital admissions had been created previously by the infection control group in our practice. These data already were being tracked, we simply had it fed to our Quality group in the Division of Gastroenterology in addition to infection control. The upfront costs of setting up that system are not known to the authors. For our practice, registered nurses who were in a Back to Work program after injuries performed the database entry tasks with no additional salary support from our group. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. The adverse event tracking infrastructure was administered and analyzed by both a quality analyst and a staff gastroenterologist.

Results

During the study period, 11,710 endoscopic procedures (5,075 colonoscopies, 627 flexible sigmoidoscopies, 4,450 esophagogastroduodenoscopies, 117 double balloon enteroscopy, 470 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies, 761 endoscopic ultrasounds, and 210 percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) were performed on 9,683 patients. Patient calls were made by three full-time study personnel. They made at least one telephone call to 1,999 patients (20.6% of all patients in the study period), and ultimately made contact with 1,690 patients (84.5% of those who were called). Of the 1,999 patients called, 1,131 (56.6%) were called once, 530 (26.5%) were called twice, and 338 (16.9%) were called 3 times, for a total of 3,205 calls. For the intention-to-treat analysis, we used 9,683 as the denominator, because our intention was to reach all 9,683 patients. For the per-protocol analysis, we used 1,999 as the denominator, representing the number of patients called 1 or more times.

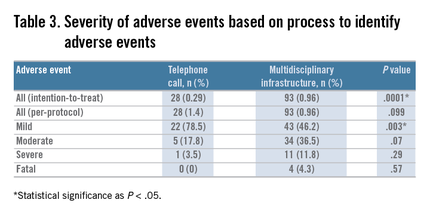

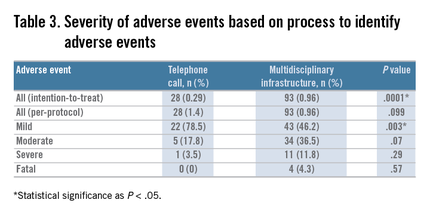

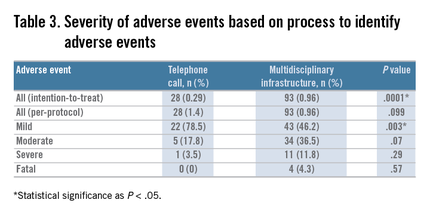

Twenty-eight true adverse events were identified through the telephone contact method. By using the ASGE grading system (Table 1), 22 (78.5%) were graded as mild, 5 (17.8%) as moderate, and 1 (3.5%) as severe. By comparison, our adverse event tracking MDI identified 93 adverse events. Of these, 43 (46.2%) were mild (P = .003), 34 (36.5%) were moderate (P = .07), 12 (12.9%) were severe (P = .29), and 4 (4.3%) were fatal (P = .57) (Table 3).Telephone query identified pain in 16 patients (57%), bleeding in 6 (21.4%), cardiovascular events in 2 (7.1%), infection in 1 (3.5%), pulmonary in 1 (3.5%), and instrumental (perforation) in 1 (3.5%) (based on the ASGE classification system) (Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). By comparison, MDI event tracking identified pain in 19 (20.4%; P = .0006), bleeding in 16 (17.2%; P = .5871), cardiovascular events in 17 (18.2%; P = .237), instrumental in 16 (17.2%; P = .117), pancreatitis in 6 (6.5%; P = .33), pulmonary in 6 (6.5%; P = 1.00), infection in 4 (4.3%; P = 1.00), integument in 3 (3.2%; P = 1.00), and other in 4 (4.3%; P = .5723).

Only 7 events were detected by both methods; the direct patient contact method detected 21 unique cases and the MDI detected 86 unique cases. Together, the two methods identified 107 (1.1%) adverse events over the study period.

The MDI event tracking method had many avenues for reporting adverse events. Of those reported, 73 (78%) were reported by one source, 17 (18.3%) were reported by two sources, and 3 (3.2%) were reported by three or more sources. Of the 73 events that were reported by a single source, 45.2% were reported by physicians within our practice, 28.7% were reported by our automated reporting system, 21.9% were reported by gastroenterology nursing, and 4.2% were reported by patients returning their endoscopic complication cards (Figure 2).

When using the intention-to-treat analysis we found a significantly higher capture rate for adverse events in the MDI method vs. the telephone contact method (P = .0001). The statistical power for the intention-to-treat analysis was 100%. When using the per-protocol analysis, we found no significant difference (P = .099) between the two methods. The statistical power for the per-protocol analysis was 80.7%.

Discussion

Our gastroenterology professional societies have recommended that adverse events associated with endoscopic procedures be identified and tracked to ensure quality and safety in an endoscopic practice2,3,16,17,18 and to identify trends in a practice or provider that might require intervention or improvement.

Tracking adverse events is no easy task. In the past, there has been an assumption that the best way to identify adverse events is by direct patient contact either by telephone, follow-up visits, or mailings.8,10,11,12,19

All of these methods are time and cost intensive. It is our impression that few practices have developed formal programs for tracking adverse events, likely because of these barriers.

This study showed that a multidisciplinary infrastructure to track endoscopic adverse events in a high-volume endoscopy center performs at least as well as a program designed to contact patients directly via telephone, using both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses. Furthermore, there was a trend toward capturing more severe adverse events (including fatalities) with the MDI vs. the direct patient contact method.

The costs associated with our internal infrastructure include the cost of the endoscopic complication cards (approximately $1,000 for the study period) and the personnel to enter adverse events into a database. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. We acknowledge that this infrastructure does use some resources and is not no-cost. However, many experts agree that quality improvement and reporting processes require dedicated resources that should be considered part of the cost of practice.1

There were some important limitations to this study. We did not try other methods of directly contacting patients after their procedures to identify adverse events. We did not use direct mailings, and we did not arrange for follow-up visits in our unit after every procedure. In our practice, doing so is not feasible, although we recognize that for many practices this may be a viable process to assist in adverse event tracking. We also did not use an electronic mailing system because, at the time the study was conducted, there was not a secure patient portal to do so, an obstacle that has since been cleared. Had these elements been part of the study protocol, we likely would have captured more adverse events.

Our study did not include a claims analysis. Although our health system does not use claims analysis to track adverse events, we recognize that many systems have an insurance arm or payer partner that may provide adverse event data based on claims. Medicare claims analysis suggests a higher rate of complications than shown with either one of the processes presented here. A claims process to identify adverse events should identify events no matter where the patient presents for care and also would identify patients who have events as part of the procedural preparation process (e.g., complications of colon purge or hypoglycemia in diabetic patients). In the future, it is likely that the best tracking of adverse events will be via claims data, and it is also this information that will be used to identify high-value endoscopy units. A significant problem we encountered was that our study personnel were able to contact only a portion (17.5%) of the patients we had intended for them to contact. We grossly underestimated the challenges of contacting patients by telephone during regular business hours (a limitation of our institution). Our study personnel also were surprised with the length of time they were kept on the phone with study participants when they did make contact. Although we provided instructions to stick to the telephone interview script, participants often would stray from the subject of the interview and discuss issues such as upcoming appointments, messages they wanted conveyed to their providers, or feedback about their experience. As a result of these issues, we were not able to contact as many patients as required by our a priori sample size calculation. However, the statistical power for the per-protocol analysis (which included only those patients for whom there was an attempt to be contacted: 1,999 patients) was 80.7%.

The funding for this study was directed solely at salary support for the personnel conducting the telephone interviews, and when those funds were exhausted, the study was closed, which is why we were forced to accept the low proportion of patients contacted by telephone.

There are several ways this may have affected our study results. First, patients who can be contacted during business hours may be different from those who could not be contacted. Certainly, if a patient is in the hospital or deceased, contact by telephone would not be successful. This notion is supported by our data, which shows a trend toward adverse events that were identified in the telephone query group being of a lower severity than those identified with the MDI.

Second, the inability to connect by telephone with most of the patients who underwent a procedure may have biased our results in favor of the MDI, assuming that the MDI could capture events in the 82.5% of those patients not contacted by telephone.

It is disappointing that contacting patients directly by telephone was more of a challenge than we anticipated, but it underscores the reality that this one modality may not be sufficient for an adverse event tracking program.

It should be noted that only seven adverse events overlapped between the two systems, which indicates that they were complementary. Not only did we learn that querying by telephone likely is not enough as a singular modality for adverse event tracking, we also learned that our MDI could use another method of contacting patients directly. Our practice does not have the resources to employ personnel to contact all patients by telephone postprocedurally (because we perform approximately 150 procedures daily), so another modality could be considered, such as an electronic mailing to patients, which could be automated and nearly without cost.

This study showed a method, besides direct patient contact, that can track adverse events effectively, in a way that many practices can adopt. We believe our practice has benefited from this infrastructure, not only because of our ability to track adverse events and use trends to improve our practice,20,21 but also because it has promoted a distinct cultural shift toward a focus on quality and safety. Our professional societies and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have focused on adverse event tracking as an attempt to develop a culture of reporting and transparency. In this study, two-thirds of all the adverse events identified were reported by physicians (including fellows) or nurses in our own practice. To us, this shows that we not only have developed a viable program for adverse event tracking but that we have created a culture in which providers feel encouraged and empowered to report and discuss quality and safety.

References

1. Petersen, B.T. Quality improvement for the ambulatory surgery center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:911-8.

2. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:864-5.

3. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S1-2

4. Gellad, Z.F., Thompson, C.P., Taheri, J. Endoscopy unit efficiency: quality redefined. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;11:1046-9e1.

5. Freeman, M.L., Nelson, D.B., Sherman, S., et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:909-18.

6. Ko, C.W., Dominitz, J.A. Complications of colonoscopy: magnitude and management. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2010;20:659-71.

7. Loperfido, S., Angelini, G., Benedetti, G., et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1998;48:1-10.

8. Mahnke, D., Chen, Y.K., Antillon, M.R., et al. A prospective study of complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound in an ambulatory endoscopy center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;4:924-30.

9. Masci, E., Toti, G., Mariani, A. et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-23.

10. Penaloza-Ramirez, A., Leal-Buitrago, C., Rodriguez-Hernandez, A. Adverse events of ERCP at San Jose Hospital of Bogota (Colombia). Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2009;101:837-49.

11. Sieg, A., Hachmoeller-Eisenbach, U., Eisenbach, T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: a survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:620-7.

12. Warren, J.L., Klabunde, C.N., Mariotto, A.B., et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:849-57. (W152)

13. Zubarik, R., Eisen, G., Mastropietro, C., et al. Prospective analysis of complications 30 days after outpatient upper endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1539-45.

14. Francis, D.L. Automated processes to improve the quality and safety in an endoscopic practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:540-3.

15. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L., et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

16. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., et al. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:886-91.

17. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:866-72.

18. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-28.

19. O’Toole, D., Palazzo, L., Arotcarena, R., et al. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:470-4.

20. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Bryant-Sendek, D.M., et al. Quality improvement project eliminates falls in recovery area of high volume endoscopy unit. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011;20:170-3.

21. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Sanderson, S.O. A quality initiative to decrease pathology specimen-labeling errors using radiofrequency identification in a high-volume endoscopy center. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:972-5.

Dr. Francis is associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.; Dr. Kane is professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Ms.Prabhakar is a quality improvement advisor, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Dr. Petersen is a professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. This study was funded by an American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Crystal Award. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

This month’s article concerns postprocedure complications, a topic of increasing importance as we move to “value-based” reimbursement. Most practices and health systems do not have a routine process to identify complications and we have underestimated them in the past. In the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Final Rule (published in the Federal Register November 2014 – entitled CMS-1613-FC) a new measure for both the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and the Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting Program was described. Beginning in calendar year 2018, measure OP-32 will be Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate after Outpatient Colonoscopy and will be required for submission to CMS. Thus, our endoscopy units will need to understand how they might measure and reduce postprocedure complications. Dr. Francis and her colleagues have given us a choice of methods to collect such information.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Safety is one of the most important determinants of quality in endoscopy and adverse event tracking is an effective way to monitor the safety of a procedural practice.1 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)/American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy recommends the use of a formal protocol for tracking adverse events,2,3 but provides little guidance about how this can be accomplished successfully.

Adverse events have costs associated with them. There is the real human cost of pain and suffering, but there are health care utilization costs as well. As such, adverse event rates are one outcome measure that could be part of the definition of value for a practice4 and likely will play a role in value-based purchasing.

Tracking adverse events is challenging. The best way to track adverse events might be via direct contact with the patient at a postprocedure interval beyond the window of time when an adverse event could take place, but not so remote as to hamper memory of an event.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Many authorities consider this the gold standard for event identification, but it is difficult to accomplish because it requires dedicated personnel and resources. An alternative, low-cost, sustainable means for identifying adverse events that approximates the data from direct patient contact would be attractive.

Such a program might require an infrastructure encompassing a variety of different reporting mechanisms to compensate for the lack of direct patient contact and the limitations of any individual form of reporting.14 For example, a process that relies solely on reporting from within the health care system that performed the procedure is limited to identifying patients who return to the same system for care of an adverse event. For our referral center, such a unimodal approach could miss a significant proportion of events because many of our patients live outside of our local-regional catchment area. Likewise, a system that relies solely on voluntary reporting by health care providers is limited by the providers having the time and inclination to consistently report adverse events when they encounter them.

With these issues in mind, our Gastroenterology Quality Committee created a multidisciplinary infrastructure (MDI) to track adverse events associated with our endoscopic practice. Our infrastructure uses the following. First, endoscopy nurse reporting of adverse events during or immediately after gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Our nursing staff have paper reporting cards and a voice mail event line, both of which can be used to report anything they believe is an adverse event to our Gastroenterology Quality Office. Second, an institutional website link that can be used by any health care worker in our system to electronically report an adverse event. Third, weekly electronic reminders to report adverse events that are sent to all physicians (attendings and fellows) assigned to hospital duties for gastroenterology services. Fourth, an endoscopic complication card provided to all patients at the time of their endoscopy for them to return (in a business reply envelope) if they experience an adverse event (Figure 1: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). Fifth, an automated reporting system that identifies all patients who are admitted, for any reason, to our hospitals within 7 days of an endoscopic procedure. This process does not identify emergency room visits that do not result in a hospital admission.

Although we assumed our MDI used to track adverse events was robust, it had not been validated with another method. Our objective was to validate our MDI process of capturing adverse events by comparing it with direct patient contact via telephone.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minn.). We performed a prospective study to compare two mechanisms for identifying the number, type, and severity of adverse events associated with all types of inpatient and outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures.

We first initiated enhanced tracking of endoscopic adverse events in 2008, using a multimodal infrastructure that has matured since then to include the variety of sources outlined earlier. Based on the lexicon for endoscopic adverse events proposed by a recent ASGE workgroup,15 we consider an adverse event to be one that prevents the completion of the planned procedure and/or results in another procedure, subsequent medical consultation or admission to the hospital, or prolongation of an existing hospital stay. This includes obvious complications such as perforation, postpolypectomy bleeding, and post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. It also includes some less obvious situations, such as bleeding severe enough to prompt the patient to seek medical care even if an intervention is not required, and abdominal pain that leads a patient to be admitted to the hospital even if a source of pain is not identified. We also used the same group’s recommendations for grading their severity and categorizing the events (Table 1, Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext).15

In the comparative study we then attempted to contact patients by telephone who had an endoscopic procedure performed between July 26, 2011, and December 29, 2011. Three full-time study personnel contacted patients between 14 and 90 days after their procedure to inquire about adverse events that may have resulted from endoscopy. During this time, we continued our existing MDI for tracking adverse events. Events considered adverse were those plausibly associated with the procedure and severe enough for the patient to seek medical attention.

Patient contact

Our research personnel attempted to contact, by telephone, patients who had a gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure in one of our endoscopy units after at least 14 and no more than 90 days to inquire about the occurrence of adverse events. A scripted interview (Appendix A: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext) was used and calls were made only during business hours (between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.).

Our institution uses strict guidelines for patient contact. When a telephone call is not answered, our personnel may only leave a message stating that they are calling from the Mayo Clinic and provide a telephone number for a return call. They are not allowed to say what the call is regarding. Study personnel may make only three telephone calls before they must stop attempts to contact a patient.

Written consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board, so once a patient was contacted they could consent and be interviewed over the telephone. However, to include their information participants were required to return a signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) consent form. Without receiving a signed HIPAA consent form, the data collected for inclusion in the study could not be used.

Sample size calculation

Complications from gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures are rare events. For the purposes of our study, we believed it was important to find even small differences in the ability of the two modalities to identify adverse events. We powered this study to detect a 5% difference between the two capture mechanisms, which required a sample size of 9,894 procedures.

Statistical analysis

We compared the proportion of patients with adverse events as well as the type and severity of the events associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy, as identified by direct patient contact by telephone, with the proportion, type, and severity of events identified through our MDI, using the chi-square statistic for larger sample sizes (e.g., the proportion of overall adverse events in each tracking mechanism group) and the Fisher exact test for smaller sample sizes (e.g., comparing the type of adverse event in each tracking mechanism group). We used both an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis.

Costs

The study was funded by an ASGE research grant for $60,000. A total of $55,000 was spent on study personnel salary and benefits, and the sole responsibility of the study personnel was to contact patients by telephone. As stated previously, three full-time personnel contacted patients by telephone to query them about adverse events every business day for 5 months. The remaining $5000 was spent on statistical design, data entry and analysis, and administration of the study personnel.

The MDI arm of the study already was integrated into the practice. The nurse reporting was part of the job description for our nursing staff and did not require any extra hours or personnel. This also was true for physician reporting. The institutional website link and weekly electronic reminders were put into place by a medical secretary and did not require additional salary support. We estimate that it took an hour of secretarial time to create the website link and to set up weekly e-mail reminders to staff. The endoscopic complication cards that were given to all patients and returned by some of the patients cost $968 during the study period. The automated process for hospital admissions had been created previously by the infection control group in our practice. These data already were being tracked, we simply had it fed to our Quality group in the Division of Gastroenterology in addition to infection control. The upfront costs of setting up that system are not known to the authors. For our practice, registered nurses who were in a Back to Work program after injuries performed the database entry tasks with no additional salary support from our group. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. The adverse event tracking infrastructure was administered and analyzed by both a quality analyst and a staff gastroenterologist.

Results

During the study period, 11,710 endoscopic procedures (5,075 colonoscopies, 627 flexible sigmoidoscopies, 4,450 esophagogastroduodenoscopies, 117 double balloon enteroscopy, 470 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies, 761 endoscopic ultrasounds, and 210 percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) were performed on 9,683 patients. Patient calls were made by three full-time study personnel. They made at least one telephone call to 1,999 patients (20.6% of all patients in the study period), and ultimately made contact with 1,690 patients (84.5% of those who were called). Of the 1,999 patients called, 1,131 (56.6%) were called once, 530 (26.5%) were called twice, and 338 (16.9%) were called 3 times, for a total of 3,205 calls. For the intention-to-treat analysis, we used 9,683 as the denominator, because our intention was to reach all 9,683 patients. For the per-protocol analysis, we used 1,999 as the denominator, representing the number of patients called 1 or more times.

Twenty-eight true adverse events were identified through the telephone contact method. By using the ASGE grading system (Table 1), 22 (78.5%) were graded as mild, 5 (17.8%) as moderate, and 1 (3.5%) as severe. By comparison, our adverse event tracking MDI identified 93 adverse events. Of these, 43 (46.2%) were mild (P = .003), 34 (36.5%) were moderate (P = .07), 12 (12.9%) were severe (P = .29), and 4 (4.3%) were fatal (P = .57) (Table 3).Telephone query identified pain in 16 patients (57%), bleeding in 6 (21.4%), cardiovascular events in 2 (7.1%), infection in 1 (3.5%), pulmonary in 1 (3.5%), and instrumental (perforation) in 1 (3.5%) (based on the ASGE classification system) (Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). By comparison, MDI event tracking identified pain in 19 (20.4%; P = .0006), bleeding in 16 (17.2%; P = .5871), cardiovascular events in 17 (18.2%; P = .237), instrumental in 16 (17.2%; P = .117), pancreatitis in 6 (6.5%; P = .33), pulmonary in 6 (6.5%; P = 1.00), infection in 4 (4.3%; P = 1.00), integument in 3 (3.2%; P = 1.00), and other in 4 (4.3%; P = .5723).

Only 7 events were detected by both methods; the direct patient contact method detected 21 unique cases and the MDI detected 86 unique cases. Together, the two methods identified 107 (1.1%) adverse events over the study period.

The MDI event tracking method had many avenues for reporting adverse events. Of those reported, 73 (78%) were reported by one source, 17 (18.3%) were reported by two sources, and 3 (3.2%) were reported by three or more sources. Of the 73 events that were reported by a single source, 45.2% were reported by physicians within our practice, 28.7% were reported by our automated reporting system, 21.9% were reported by gastroenterology nursing, and 4.2% were reported by patients returning their endoscopic complication cards (Figure 2).

When using the intention-to-treat analysis we found a significantly higher capture rate for adverse events in the MDI method vs. the telephone contact method (P = .0001). The statistical power for the intention-to-treat analysis was 100%. When using the per-protocol analysis, we found no significant difference (P = .099) between the two methods. The statistical power for the per-protocol analysis was 80.7%.

Discussion

Our gastroenterology professional societies have recommended that adverse events associated with endoscopic procedures be identified and tracked to ensure quality and safety in an endoscopic practice2,3,16,17,18 and to identify trends in a practice or provider that might require intervention or improvement.

Tracking adverse events is no easy task. In the past, there has been an assumption that the best way to identify adverse events is by direct patient contact either by telephone, follow-up visits, or mailings.8,10,11,12,19

All of these methods are time and cost intensive. It is our impression that few practices have developed formal programs for tracking adverse events, likely because of these barriers.

This study showed that a multidisciplinary infrastructure to track endoscopic adverse events in a high-volume endoscopy center performs at least as well as a program designed to contact patients directly via telephone, using both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses. Furthermore, there was a trend toward capturing more severe adverse events (including fatalities) with the MDI vs. the direct patient contact method.

The costs associated with our internal infrastructure include the cost of the endoscopic complication cards (approximately $1,000 for the study period) and the personnel to enter adverse events into a database. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. We acknowledge that this infrastructure does use some resources and is not no-cost. However, many experts agree that quality improvement and reporting processes require dedicated resources that should be considered part of the cost of practice.1

There were some important limitations to this study. We did not try other methods of directly contacting patients after their procedures to identify adverse events. We did not use direct mailings, and we did not arrange for follow-up visits in our unit after every procedure. In our practice, doing so is not feasible, although we recognize that for many practices this may be a viable process to assist in adverse event tracking. We also did not use an electronic mailing system because, at the time the study was conducted, there was not a secure patient portal to do so, an obstacle that has since been cleared. Had these elements been part of the study protocol, we likely would have captured more adverse events.

Our study did not include a claims analysis. Although our health system does not use claims analysis to track adverse events, we recognize that many systems have an insurance arm or payer partner that may provide adverse event data based on claims. Medicare claims analysis suggests a higher rate of complications than shown with either one of the processes presented here. A claims process to identify adverse events should identify events no matter where the patient presents for care and also would identify patients who have events as part of the procedural preparation process (e.g., complications of colon purge or hypoglycemia in diabetic patients). In the future, it is likely that the best tracking of adverse events will be via claims data, and it is also this information that will be used to identify high-value endoscopy units. A significant problem we encountered was that our study personnel were able to contact only a portion (17.5%) of the patients we had intended for them to contact. We grossly underestimated the challenges of contacting patients by telephone during regular business hours (a limitation of our institution). Our study personnel also were surprised with the length of time they were kept on the phone with study participants when they did make contact. Although we provided instructions to stick to the telephone interview script, participants often would stray from the subject of the interview and discuss issues such as upcoming appointments, messages they wanted conveyed to their providers, or feedback about their experience. As a result of these issues, we were not able to contact as many patients as required by our a priori sample size calculation. However, the statistical power for the per-protocol analysis (which included only those patients for whom there was an attempt to be contacted: 1,999 patients) was 80.7%.

The funding for this study was directed solely at salary support for the personnel conducting the telephone interviews, and when those funds were exhausted, the study was closed, which is why we were forced to accept the low proportion of patients contacted by telephone.

There are several ways this may have affected our study results. First, patients who can be contacted during business hours may be different from those who could not be contacted. Certainly, if a patient is in the hospital or deceased, contact by telephone would not be successful. This notion is supported by our data, which shows a trend toward adverse events that were identified in the telephone query group being of a lower severity than those identified with the MDI.

Second, the inability to connect by telephone with most of the patients who underwent a procedure may have biased our results in favor of the MDI, assuming that the MDI could capture events in the 82.5% of those patients not contacted by telephone.

It is disappointing that contacting patients directly by telephone was more of a challenge than we anticipated, but it underscores the reality that this one modality may not be sufficient for an adverse event tracking program.

It should be noted that only seven adverse events overlapped between the two systems, which indicates that they were complementary. Not only did we learn that querying by telephone likely is not enough as a singular modality for adverse event tracking, we also learned that our MDI could use another method of contacting patients directly. Our practice does not have the resources to employ personnel to contact all patients by telephone postprocedurally (because we perform approximately 150 procedures daily), so another modality could be considered, such as an electronic mailing to patients, which could be automated and nearly without cost.

This study showed a method, besides direct patient contact, that can track adverse events effectively, in a way that many practices can adopt. We believe our practice has benefited from this infrastructure, not only because of our ability to track adverse events and use trends to improve our practice,20,21 but also because it has promoted a distinct cultural shift toward a focus on quality and safety. Our professional societies and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have focused on adverse event tracking as an attempt to develop a culture of reporting and transparency. In this study, two-thirds of all the adverse events identified were reported by physicians (including fellows) or nurses in our own practice. To us, this shows that we not only have developed a viable program for adverse event tracking but that we have created a culture in which providers feel encouraged and empowered to report and discuss quality and safety.

References

1. Petersen, B.T. Quality improvement for the ambulatory surgery center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:911-8.

2. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:864-5.

3. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S1-2

4. Gellad, Z.F., Thompson, C.P., Taheri, J. Endoscopy unit efficiency: quality redefined. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;11:1046-9e1.

5. Freeman, M.L., Nelson, D.B., Sherman, S., et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:909-18.

6. Ko, C.W., Dominitz, J.A. Complications of colonoscopy: magnitude and management. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2010;20:659-71.

7. Loperfido, S., Angelini, G., Benedetti, G., et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1998;48:1-10.

8. Mahnke, D., Chen, Y.K., Antillon, M.R., et al. A prospective study of complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound in an ambulatory endoscopy center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;4:924-30.

9. Masci, E., Toti, G., Mariani, A. et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-23.

10. Penaloza-Ramirez, A., Leal-Buitrago, C., Rodriguez-Hernandez, A. Adverse events of ERCP at San Jose Hospital of Bogota (Colombia). Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2009;101:837-49.

11. Sieg, A., Hachmoeller-Eisenbach, U., Eisenbach, T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: a survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:620-7.

12. Warren, J.L., Klabunde, C.N., Mariotto, A.B., et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:849-57. (W152)

13. Zubarik, R., Eisen, G., Mastropietro, C., et al. Prospective analysis of complications 30 days after outpatient upper endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1539-45.

14. Francis, D.L. Automated processes to improve the quality and safety in an endoscopic practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:540-3.

15. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L., et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

16. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., et al. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:886-91.

17. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:866-72.

18. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-28.

19. O’Toole, D., Palazzo, L., Arotcarena, R., et al. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:470-4.

20. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Bryant-Sendek, D.M., et al. Quality improvement project eliminates falls in recovery area of high volume endoscopy unit. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011;20:170-3.

21. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Sanderson, S.O. A quality initiative to decrease pathology specimen-labeling errors using radiofrequency identification in a high-volume endoscopy center. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:972-5.

Dr. Francis is associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.; Dr. Kane is professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Ms.Prabhakar is a quality improvement advisor, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Dr. Petersen is a professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. This study was funded by an American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Crystal Award. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

This month’s article concerns postprocedure complications, a topic of increasing importance as we move to “value-based” reimbursement. Most practices and health systems do not have a routine process to identify complications and we have underestimated them in the past. In the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Final Rule (published in the Federal Register November 2014 – entitled CMS-1613-FC) a new measure for both the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and the Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting Program was described. Beginning in calendar year 2018, measure OP-32 will be Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate after Outpatient Colonoscopy and will be required for submission to CMS. Thus, our endoscopy units will need to understand how they might measure and reduce postprocedure complications. Dr. Francis and her colleagues have given us a choice of methods to collect such information.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Safety is one of the most important determinants of quality in endoscopy and adverse event tracking is an effective way to monitor the safety of a procedural practice.1 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)/American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy recommends the use of a formal protocol for tracking adverse events,2,3 but provides little guidance about how this can be accomplished successfully.

Adverse events have costs associated with them. There is the real human cost of pain and suffering, but there are health care utilization costs as well. As such, adverse event rates are one outcome measure that could be part of the definition of value for a practice4 and likely will play a role in value-based purchasing.

Tracking adverse events is challenging. The best way to track adverse events might be via direct contact with the patient at a postprocedure interval beyond the window of time when an adverse event could take place, but not so remote as to hamper memory of an event.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Many authorities consider this the gold standard for event identification, but it is difficult to accomplish because it requires dedicated personnel and resources. An alternative, low-cost, sustainable means for identifying adverse events that approximates the data from direct patient contact would be attractive.

Such a program might require an infrastructure encompassing a variety of different reporting mechanisms to compensate for the lack of direct patient contact and the limitations of any individual form of reporting.14 For example, a process that relies solely on reporting from within the health care system that performed the procedure is limited to identifying patients who return to the same system for care of an adverse event. For our referral center, such a unimodal approach could miss a significant proportion of events because many of our patients live outside of our local-regional catchment area. Likewise, a system that relies solely on voluntary reporting by health care providers is limited by the providers having the time and inclination to consistently report adverse events when they encounter them.

With these issues in mind, our Gastroenterology Quality Committee created a multidisciplinary infrastructure (MDI) to track adverse events associated with our endoscopic practice. Our infrastructure uses the following. First, endoscopy nurse reporting of adverse events during or immediately after gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Our nursing staff have paper reporting cards and a voice mail event line, both of which can be used to report anything they believe is an adverse event to our Gastroenterology Quality Office. Second, an institutional website link that can be used by any health care worker in our system to electronically report an adverse event. Third, weekly electronic reminders to report adverse events that are sent to all physicians (attendings and fellows) assigned to hospital duties for gastroenterology services. Fourth, an endoscopic complication card provided to all patients at the time of their endoscopy for them to return (in a business reply envelope) if they experience an adverse event (Figure 1: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). Fifth, an automated reporting system that identifies all patients who are admitted, for any reason, to our hospitals within 7 days of an endoscopic procedure. This process does not identify emergency room visits that do not result in a hospital admission.

Although we assumed our MDI used to track adverse events was robust, it had not been validated with another method. Our objective was to validate our MDI process of capturing adverse events by comparing it with direct patient contact via telephone.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minn.). We performed a prospective study to compare two mechanisms for identifying the number, type, and severity of adverse events associated with all types of inpatient and outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures.

We first initiated enhanced tracking of endoscopic adverse events in 2008, using a multimodal infrastructure that has matured since then to include the variety of sources outlined earlier. Based on the lexicon for endoscopic adverse events proposed by a recent ASGE workgroup,15 we consider an adverse event to be one that prevents the completion of the planned procedure and/or results in another procedure, subsequent medical consultation or admission to the hospital, or prolongation of an existing hospital stay. This includes obvious complications such as perforation, postpolypectomy bleeding, and post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. It also includes some less obvious situations, such as bleeding severe enough to prompt the patient to seek medical care even if an intervention is not required, and abdominal pain that leads a patient to be admitted to the hospital even if a source of pain is not identified. We also used the same group’s recommendations for grading their severity and categorizing the events (Table 1, Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext).15

In the comparative study we then attempted to contact patients by telephone who had an endoscopic procedure performed between July 26, 2011, and December 29, 2011. Three full-time study personnel contacted patients between 14 and 90 days after their procedure to inquire about adverse events that may have resulted from endoscopy. During this time, we continued our existing MDI for tracking adverse events. Events considered adverse were those plausibly associated with the procedure and severe enough for the patient to seek medical attention.

Patient contact

Our research personnel attempted to contact, by telephone, patients who had a gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure in one of our endoscopy units after at least 14 and no more than 90 days to inquire about the occurrence of adverse events. A scripted interview (Appendix A: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext) was used and calls were made only during business hours (between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.).

Our institution uses strict guidelines for patient contact. When a telephone call is not answered, our personnel may only leave a message stating that they are calling from the Mayo Clinic and provide a telephone number for a return call. They are not allowed to say what the call is regarding. Study personnel may make only three telephone calls before they must stop attempts to contact a patient.

Written consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board, so once a patient was contacted they could consent and be interviewed over the telephone. However, to include their information participants were required to return a signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) consent form. Without receiving a signed HIPAA consent form, the data collected for inclusion in the study could not be used.

Sample size calculation

Complications from gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures are rare events. For the purposes of our study, we believed it was important to find even small differences in the ability of the two modalities to identify adverse events. We powered this study to detect a 5% difference between the two capture mechanisms, which required a sample size of 9,894 procedures.

Statistical analysis

We compared the proportion of patients with adverse events as well as the type and severity of the events associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy, as identified by direct patient contact by telephone, with the proportion, type, and severity of events identified through our MDI, using the chi-square statistic for larger sample sizes (e.g., the proportion of overall adverse events in each tracking mechanism group) and the Fisher exact test for smaller sample sizes (e.g., comparing the type of adverse event in each tracking mechanism group). We used both an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis.

Costs

The study was funded by an ASGE research grant for $60,000. A total of $55,000 was spent on study personnel salary and benefits, and the sole responsibility of the study personnel was to contact patients by telephone. As stated previously, three full-time personnel contacted patients by telephone to query them about adverse events every business day for 5 months. The remaining $5000 was spent on statistical design, data entry and analysis, and administration of the study personnel.

The MDI arm of the study already was integrated into the practice. The nurse reporting was part of the job description for our nursing staff and did not require any extra hours or personnel. This also was true for physician reporting. The institutional website link and weekly electronic reminders were put into place by a medical secretary and did not require additional salary support. We estimate that it took an hour of secretarial time to create the website link and to set up weekly e-mail reminders to staff. The endoscopic complication cards that were given to all patients and returned by some of the patients cost $968 during the study period. The automated process for hospital admissions had been created previously by the infection control group in our practice. These data already were being tracked, we simply had it fed to our Quality group in the Division of Gastroenterology in addition to infection control. The upfront costs of setting up that system are not known to the authors. For our practice, registered nurses who were in a Back to Work program after injuries performed the database entry tasks with no additional salary support from our group. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. The adverse event tracking infrastructure was administered and analyzed by both a quality analyst and a staff gastroenterologist.

Results

During the study period, 11,710 endoscopic procedures (5,075 colonoscopies, 627 flexible sigmoidoscopies, 4,450 esophagogastroduodenoscopies, 117 double balloon enteroscopy, 470 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies, 761 endoscopic ultrasounds, and 210 percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) were performed on 9,683 patients. Patient calls were made by three full-time study personnel. They made at least one telephone call to 1,999 patients (20.6% of all patients in the study period), and ultimately made contact with 1,690 patients (84.5% of those who were called). Of the 1,999 patients called, 1,131 (56.6%) were called once, 530 (26.5%) were called twice, and 338 (16.9%) were called 3 times, for a total of 3,205 calls. For the intention-to-treat analysis, we used 9,683 as the denominator, because our intention was to reach all 9,683 patients. For the per-protocol analysis, we used 1,999 as the denominator, representing the number of patients called 1 or more times.

Twenty-eight true adverse events were identified through the telephone contact method. By using the ASGE grading system (Table 1), 22 (78.5%) were graded as mild, 5 (17.8%) as moderate, and 1 (3.5%) as severe. By comparison, our adverse event tracking MDI identified 93 adverse events. Of these, 43 (46.2%) were mild (P = .003), 34 (36.5%) were moderate (P = .07), 12 (12.9%) were severe (P = .29), and 4 (4.3%) were fatal (P = .57) (Table 3).Telephone query identified pain in 16 patients (57%), bleeding in 6 (21.4%), cardiovascular events in 2 (7.1%), infection in 1 (3.5%), pulmonary in 1 (3.5%), and instrumental (perforation) in 1 (3.5%) (based on the ASGE classification system) (Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). By comparison, MDI event tracking identified pain in 19 (20.4%; P = .0006), bleeding in 16 (17.2%; P = .5871), cardiovascular events in 17 (18.2%; P = .237), instrumental in 16 (17.2%; P = .117), pancreatitis in 6 (6.5%; P = .33), pulmonary in 6 (6.5%; P = 1.00), infection in 4 (4.3%; P = 1.00), integument in 3 (3.2%; P = 1.00), and other in 4 (4.3%; P = .5723).

Only 7 events were detected by both methods; the direct patient contact method detected 21 unique cases and the MDI detected 86 unique cases. Together, the two methods identified 107 (1.1%) adverse events over the study period.

The MDI event tracking method had many avenues for reporting adverse events. Of those reported, 73 (78%) were reported by one source, 17 (18.3%) were reported by two sources, and 3 (3.2%) were reported by three or more sources. Of the 73 events that were reported by a single source, 45.2% were reported by physicians within our practice, 28.7% were reported by our automated reporting system, 21.9% were reported by gastroenterology nursing, and 4.2% were reported by patients returning their endoscopic complication cards (Figure 2).

When using the intention-to-treat analysis we found a significantly higher capture rate for adverse events in the MDI method vs. the telephone contact method (P = .0001). The statistical power for the intention-to-treat analysis was 100%. When using the per-protocol analysis, we found no significant difference (P = .099) between the two methods. The statistical power for the per-protocol analysis was 80.7%.

Discussion

Our gastroenterology professional societies have recommended that adverse events associated with endoscopic procedures be identified and tracked to ensure quality and safety in an endoscopic practice2,3,16,17,18 and to identify trends in a practice or provider that might require intervention or improvement.

Tracking adverse events is no easy task. In the past, there has been an assumption that the best way to identify adverse events is by direct patient contact either by telephone, follow-up visits, or mailings.8,10,11,12,19

All of these methods are time and cost intensive. It is our impression that few practices have developed formal programs for tracking adverse events, likely because of these barriers.

This study showed that a multidisciplinary infrastructure to track endoscopic adverse events in a high-volume endoscopy center performs at least as well as a program designed to contact patients directly via telephone, using both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses. Furthermore, there was a trend toward capturing more severe adverse events (including fatalities) with the MDI vs. the direct patient contact method.

The costs associated with our internal infrastructure include the cost of the endoscopic complication cards (approximately $1,000 for the study period) and the personnel to enter adverse events into a database. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. We acknowledge that this infrastructure does use some resources and is not no-cost. However, many experts agree that quality improvement and reporting processes require dedicated resources that should be considered part of the cost of practice.1

There were some important limitations to this study. We did not try other methods of directly contacting patients after their procedures to identify adverse events. We did not use direct mailings, and we did not arrange for follow-up visits in our unit after every procedure. In our practice, doing so is not feasible, although we recognize that for many practices this may be a viable process to assist in adverse event tracking. We also did not use an electronic mailing system because, at the time the study was conducted, there was not a secure patient portal to do so, an obstacle that has since been cleared. Had these elements been part of the study protocol, we likely would have captured more adverse events.

Our study did not include a claims analysis. Although our health system does not use claims analysis to track adverse events, we recognize that many systems have an insurance arm or payer partner that may provide adverse event data based on claims. Medicare claims analysis suggests a higher rate of complications than shown with either one of the processes presented here. A claims process to identify adverse events should identify events no matter where the patient presents for care and also would identify patients who have events as part of the procedural preparation process (e.g., complications of colon purge or hypoglycemia in diabetic patients). In the future, it is likely that the best tracking of adverse events will be via claims data, and it is also this information that will be used to identify high-value endoscopy units. A significant problem we encountered was that our study personnel were able to contact only a portion (17.5%) of the patients we had intended for them to contact. We grossly underestimated the challenges of contacting patients by telephone during regular business hours (a limitation of our institution). Our study personnel also were surprised with the length of time they were kept on the phone with study participants when they did make contact. Although we provided instructions to stick to the telephone interview script, participants often would stray from the subject of the interview and discuss issues such as upcoming appointments, messages they wanted conveyed to their providers, or feedback about their experience. As a result of these issues, we were not able to contact as many patients as required by our a priori sample size calculation. However, the statistical power for the per-protocol analysis (which included only those patients for whom there was an attempt to be contacted: 1,999 patients) was 80.7%.

The funding for this study was directed solely at salary support for the personnel conducting the telephone interviews, and when those funds were exhausted, the study was closed, which is why we were forced to accept the low proportion of patients contacted by telephone.

There are several ways this may have affected our study results. First, patients who can be contacted during business hours may be different from those who could not be contacted. Certainly, if a patient is in the hospital or deceased, contact by telephone would not be successful. This notion is supported by our data, which shows a trend toward adverse events that were identified in the telephone query group being of a lower severity than those identified with the MDI.

Second, the inability to connect by telephone with most of the patients who underwent a procedure may have biased our results in favor of the MDI, assuming that the MDI could capture events in the 82.5% of those patients not contacted by telephone.

It is disappointing that contacting patients directly by telephone was more of a challenge than we anticipated, but it underscores the reality that this one modality may not be sufficient for an adverse event tracking program.

It should be noted that only seven adverse events overlapped between the two systems, which indicates that they were complementary. Not only did we learn that querying by telephone likely is not enough as a singular modality for adverse event tracking, we also learned that our MDI could use another method of contacting patients directly. Our practice does not have the resources to employ personnel to contact all patients by telephone postprocedurally (because we perform approximately 150 procedures daily), so another modality could be considered, such as an electronic mailing to patients, which could be automated and nearly without cost.

This study showed a method, besides direct patient contact, that can track adverse events effectively, in a way that many practices can adopt. We believe our practice has benefited from this infrastructure, not only because of our ability to track adverse events and use trends to improve our practice,20,21 but also because it has promoted a distinct cultural shift toward a focus on quality and safety. Our professional societies and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have focused on adverse event tracking as an attempt to develop a culture of reporting and transparency. In this study, two-thirds of all the adverse events identified were reported by physicians (including fellows) or nurses in our own practice. To us, this shows that we not only have developed a viable program for adverse event tracking but that we have created a culture in which providers feel encouraged and empowered to report and discuss quality and safety.

References

1. Petersen, B.T. Quality improvement for the ambulatory surgery center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:911-8.

2. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:864-5.

3. Bjorkman, D.J., Popp, J.W. Jr. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S1-2

4. Gellad, Z.F., Thompson, C.P., Taheri, J. Endoscopy unit efficiency: quality redefined. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;11:1046-9e1.

5. Freeman, M.L., Nelson, D.B., Sherman, S., et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:909-18.

6. Ko, C.W., Dominitz, J.A. Complications of colonoscopy: magnitude and management. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2010;20:659-71.

7. Loperfido, S., Angelini, G., Benedetti, G., et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1998;48:1-10.

8. Mahnke, D., Chen, Y.K., Antillon, M.R., et al. A prospective study of complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound in an ambulatory endoscopy center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;4:924-30.

9. Masci, E., Toti, G., Mariani, A. et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-23.

10. Penaloza-Ramirez, A., Leal-Buitrago, C., Rodriguez-Hernandez, A. Adverse events of ERCP at San Jose Hospital of Bogota (Colombia). Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2009;101:837-49.

11. Sieg, A., Hachmoeller-Eisenbach, U., Eisenbach, T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: a survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:620-7.

12. Warren, J.L., Klabunde, C.N., Mariotto, A.B., et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:849-57. (W152)

13. Zubarik, R., Eisen, G., Mastropietro, C., et al. Prospective analysis of complications 30 days after outpatient upper endoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1539-45.

14. Francis, D.L. Automated processes to improve the quality and safety in an endoscopic practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:540-3.

15. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L., et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

16. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., et al. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:886-91.

17. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;101:866-72.

18. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-28.

19. O’Toole, D., Palazzo, L., Arotcarena, R., et al. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:470-4.

20. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Bryant-Sendek, D.M., et al. Quality improvement project eliminates falls in recovery area of high volume endoscopy unit. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011;20:170-3.

21. Francis, D.L., Prabhakar, S., Sanderson, S.O. A quality initiative to decrease pathology specimen-labeling errors using radiofrequency identification in a high-volume endoscopy center. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:972-5.

Dr. Francis is associate professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.; Dr. Kane is professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Ms.Prabhakar is a quality improvement advisor, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn; Dr. Petersen is a professor of medicine, department of gastroenterology and hepatology; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. This study was funded by an American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Crystal Award. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.