User login

Should CMS Allow Access to Patient-Protected Medicare Data for Public Reporting?

PRO

Observational, database studies provide a powerful QI supplement

The proposed rules by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which will allow access to patient-protected Medicare data, will provide for greater transparency and for data that could be utilized toward comparative-effectiveness research (CER). Thus, these rules have the potential to improve the quality of healthcare and impact patient safety.

The Institute of Medicine in December 1999 issued its now-famous article “To Err is Human,” which reported that medical errors cause up to 98,000 deaths and more than 1 million injuries each year in the U.S.6 However, the evidence shows minimal impact on improving patient safety in the past 10 years.

A retrospective study of 10 North Carolina hospitals reported in the New England Journal of Medicine by Landrigan and colleagues found that harms resulting from medical care remained extremely common, with little evidence for improvement.7 It also is estimated that it takes 17 years on average for clinical research to become incorporated into the majority of clinical practices.8 Although the randomized control trial (RCT) is unquestionably the best research tool to explore simple components of clinical care (i.e. tests, drugs, and procedures), its translation into daily clinical practice remains difficult.

Improving the process of care leading to quality remains an extremely difficult proposition based on such sociological issues as resistance to change, the need for interdisciplinary teamwork, level of support staff, economic factors, information retrieval inadequacies, and, most important, the complexity of patients with multiple comorbidities that do not fit the parameters of the RCT.

Don Berwick, MD, the lead author in the landmark IOM report and currently CMS administrator, has stated “in such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn.”9 Factors that cause this chasm include:10

- Too narrowly focused RCT;

- More required resources, including financial and personnel support with RCT, compared with usually clinical practices;

- Lack of collaboration between academic medical center researchers and community clinicians; and

- Lack of expertise and experience to undertake quality improvement in healthcare.

CER has received a $1.1 billion investment with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to provide evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of various treatment options.11 As part of this research to improve IOM’s goals to improve healthcare, better evidence is desperately needed to cross the translational gap between clinical research and the bedside.12 Observational outcome studies based on registries or databases derived primarily from clinical care can provide a powerful supplement to quality improvement.13

Thus, the ability to combine Medicare claims with other data through the Availability of Medicare Data for Performance Measurement would supply a wealth of information to potentially impact quality. As a cautionary note, safeguards such as provider review and appeal, monitoring the validity of the information, and only using the data for quality improvement are vital.

Dr. Holder is medical director of hospitalist services and chief medical information officer at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital. He is a member of Team Hospitalist.

CON

Unanswered questions, risks make CMS plan a bad idea

On June 8, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a rule to allow “qualified entities” access to patient-protected Medicare data for provider performance publication. CMS allowed 60 days for public comment and a start date of Jan. 1, 2012. But this controversial rule appeared with short notice, little discussion, and abbreviated opportunity for comment.

CMS maintains this rule will result in higher quality and more cost-effective care. Considering the present volume of data published on multiple performance parameters for both hospitals and providers, it would seem prudent to have solid data for efficacy prior to implementing more required reporting and costs to the industry.1,2,3

Physicians and hospitals will have 30 days to review and verify three years of CMS claims data before it is released. The burden and cost of review will be borne by the private practices involved.1 This process will impose added administrative costs, and it is unlikely three years of data can be carefully reviewed in just 30 days. If practitioners find the review too cumbersome and expensive, which is likely, they will forgo review, putting the accuracy of the data in question.

Quality data already is published for both physicians and hospitals. Is there evidence this process will significantly increase transparency? Adding more layers of administrative work for both CMS and caregivers—higher overhead without defined benefit—seems an ill-conceived idea. From an evidence-based-practice standpoint, where is the evidence that this rule will improve “quality” and make care “cost-effective”? Have the risks (added bureaucracy, increased overhead, questionable data) and benefits (added transparency) been evaluated?

Additionally, it is unclear who will be monitoring the quality of the data published and who will provide oversight for the “entities” to ensure these data are fairly and accurately presented. Who will pay for this oversight, and what recourse will be afforded physicians and hospitals that feel they have been wronged?4,5

The “qualified entities” will pay CMS to cover their cost of providing data, raising concerns that this practice could evolve into patient-data “purchasing.” Although it is likely the selected entities will be industry leaders (or at least initially) with the capability to protect data, is this not another opportunity for misuse or corruption in the system?

Other issues not clearly addressed include the nature of the patient-protected information and who will interpret this data in a clinical context. How will these data be adjusted for patient comorbidities and case mix, or will the data be published without regard to these important confounders?1,3

Publishing clinical data for quality assurance and feedback purposes is essential for quality care. Transparency has increased consumer confidence in the healthcare system and, indeed, has increased the healthcare system’s responsiveness to quality concerns. Granting the benefits of transparency, published data must be precise, accurate, and managed with good oversight in order to ensure the process does not target providers or skew results. Another program, especially one being fast-tracked and making once-protected patient information available to unspecified entities, raises many questions. Who will be watching these agencies for a clear interpretation? Is this yet another layer of CMS bureaucracy? In an era of evidence-based medicine, where is the evidence that this program will improve the system for the better?

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

References

- Under the magnifying glass (again): CMS proposes new access to Medicare data for public provider performance reports. Bass, Berry and Sims website. Available at: http://www.bassberry.com/communicationscenter/newsletters/. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Controversial rule to allow access to Medicare data. Modern Health website. Available at: http://www.modernHealthcare.com. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Physician report cards must give correct grades. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/09/05/edsa0905.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- OIG identifies huge lapses in hospital security, shifts its focus from CMS to OCR. Atlantic Information Services Inc. website. Available at: http://www.AISHealth.com. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Berry M. Insurers mishandle 1 in 5 claims, AMA finds. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/07/04/prl20704.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To error is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press; 1999.

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001:13.

- Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184.

- Ting HH, Shojania KG, Montori VM, Bradley EH. Quality improvement science and action. Circulation. 2009;119:1962-1974.

- Committee on Comparative Research Prioritization. Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington: National Academy Press; 2009.

- Sullivan P, Goldman D. The promise of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2011;305(4):400-401.

- Washington AE, Lipstein SH. The patient-centered outcomes research institute: promoting better information, decisions and health. Sept. 28, 2011; DOI: 10.10.1056/NEJMp1109407.

PRO

Observational, database studies provide a powerful QI supplement

The proposed rules by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which will allow access to patient-protected Medicare data, will provide for greater transparency and for data that could be utilized toward comparative-effectiveness research (CER). Thus, these rules have the potential to improve the quality of healthcare and impact patient safety.

The Institute of Medicine in December 1999 issued its now-famous article “To Err is Human,” which reported that medical errors cause up to 98,000 deaths and more than 1 million injuries each year in the U.S.6 However, the evidence shows minimal impact on improving patient safety in the past 10 years.

A retrospective study of 10 North Carolina hospitals reported in the New England Journal of Medicine by Landrigan and colleagues found that harms resulting from medical care remained extremely common, with little evidence for improvement.7 It also is estimated that it takes 17 years on average for clinical research to become incorporated into the majority of clinical practices.8 Although the randomized control trial (RCT) is unquestionably the best research tool to explore simple components of clinical care (i.e. tests, drugs, and procedures), its translation into daily clinical practice remains difficult.

Improving the process of care leading to quality remains an extremely difficult proposition based on such sociological issues as resistance to change, the need for interdisciplinary teamwork, level of support staff, economic factors, information retrieval inadequacies, and, most important, the complexity of patients with multiple comorbidities that do not fit the parameters of the RCT.

Don Berwick, MD, the lead author in the landmark IOM report and currently CMS administrator, has stated “in such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn.”9 Factors that cause this chasm include:10

- Too narrowly focused RCT;

- More required resources, including financial and personnel support with RCT, compared with usually clinical practices;

- Lack of collaboration between academic medical center researchers and community clinicians; and

- Lack of expertise and experience to undertake quality improvement in healthcare.

CER has received a $1.1 billion investment with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to provide evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of various treatment options.11 As part of this research to improve IOM’s goals to improve healthcare, better evidence is desperately needed to cross the translational gap between clinical research and the bedside.12 Observational outcome studies based on registries or databases derived primarily from clinical care can provide a powerful supplement to quality improvement.13

Thus, the ability to combine Medicare claims with other data through the Availability of Medicare Data for Performance Measurement would supply a wealth of information to potentially impact quality. As a cautionary note, safeguards such as provider review and appeal, monitoring the validity of the information, and only using the data for quality improvement are vital.

Dr. Holder is medical director of hospitalist services and chief medical information officer at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital. He is a member of Team Hospitalist.

CON

Unanswered questions, risks make CMS plan a bad idea

On June 8, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a rule to allow “qualified entities” access to patient-protected Medicare data for provider performance publication. CMS allowed 60 days for public comment and a start date of Jan. 1, 2012. But this controversial rule appeared with short notice, little discussion, and abbreviated opportunity for comment.

CMS maintains this rule will result in higher quality and more cost-effective care. Considering the present volume of data published on multiple performance parameters for both hospitals and providers, it would seem prudent to have solid data for efficacy prior to implementing more required reporting and costs to the industry.1,2,3

Physicians and hospitals will have 30 days to review and verify three years of CMS claims data before it is released. The burden and cost of review will be borne by the private practices involved.1 This process will impose added administrative costs, and it is unlikely three years of data can be carefully reviewed in just 30 days. If practitioners find the review too cumbersome and expensive, which is likely, they will forgo review, putting the accuracy of the data in question.

Quality data already is published for both physicians and hospitals. Is there evidence this process will significantly increase transparency? Adding more layers of administrative work for both CMS and caregivers—higher overhead without defined benefit—seems an ill-conceived idea. From an evidence-based-practice standpoint, where is the evidence that this rule will improve “quality” and make care “cost-effective”? Have the risks (added bureaucracy, increased overhead, questionable data) and benefits (added transparency) been evaluated?

Additionally, it is unclear who will be monitoring the quality of the data published and who will provide oversight for the “entities” to ensure these data are fairly and accurately presented. Who will pay for this oversight, and what recourse will be afforded physicians and hospitals that feel they have been wronged?4,5

The “qualified entities” will pay CMS to cover their cost of providing data, raising concerns that this practice could evolve into patient-data “purchasing.” Although it is likely the selected entities will be industry leaders (or at least initially) with the capability to protect data, is this not another opportunity for misuse or corruption in the system?

Other issues not clearly addressed include the nature of the patient-protected information and who will interpret this data in a clinical context. How will these data be adjusted for patient comorbidities and case mix, or will the data be published without regard to these important confounders?1,3

Publishing clinical data for quality assurance and feedback purposes is essential for quality care. Transparency has increased consumer confidence in the healthcare system and, indeed, has increased the healthcare system’s responsiveness to quality concerns. Granting the benefits of transparency, published data must be precise, accurate, and managed with good oversight in order to ensure the process does not target providers or skew results. Another program, especially one being fast-tracked and making once-protected patient information available to unspecified entities, raises many questions. Who will be watching these agencies for a clear interpretation? Is this yet another layer of CMS bureaucracy? In an era of evidence-based medicine, where is the evidence that this program will improve the system for the better?

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

References

- Under the magnifying glass (again): CMS proposes new access to Medicare data for public provider performance reports. Bass, Berry and Sims website. Available at: http://www.bassberry.com/communicationscenter/newsletters/. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Controversial rule to allow access to Medicare data. Modern Health website. Available at: http://www.modernHealthcare.com. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Physician report cards must give correct grades. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/09/05/edsa0905.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- OIG identifies huge lapses in hospital security, shifts its focus from CMS to OCR. Atlantic Information Services Inc. website. Available at: http://www.AISHealth.com. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Berry M. Insurers mishandle 1 in 5 claims, AMA finds. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/07/04/prl20704.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To error is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press; 1999.

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001:13.

- Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184.

- Ting HH, Shojania KG, Montori VM, Bradley EH. Quality improvement science and action. Circulation. 2009;119:1962-1974.

- Committee on Comparative Research Prioritization. Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington: National Academy Press; 2009.

- Sullivan P, Goldman D. The promise of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2011;305(4):400-401.

- Washington AE, Lipstein SH. The patient-centered outcomes research institute: promoting better information, decisions and health. Sept. 28, 2011; DOI: 10.10.1056/NEJMp1109407.

PRO

Observational, database studies provide a powerful QI supplement

The proposed rules by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which will allow access to patient-protected Medicare data, will provide for greater transparency and for data that could be utilized toward comparative-effectiveness research (CER). Thus, these rules have the potential to improve the quality of healthcare and impact patient safety.

The Institute of Medicine in December 1999 issued its now-famous article “To Err is Human,” which reported that medical errors cause up to 98,000 deaths and more than 1 million injuries each year in the U.S.6 However, the evidence shows minimal impact on improving patient safety in the past 10 years.

A retrospective study of 10 North Carolina hospitals reported in the New England Journal of Medicine by Landrigan and colleagues found that harms resulting from medical care remained extremely common, with little evidence for improvement.7 It also is estimated that it takes 17 years on average for clinical research to become incorporated into the majority of clinical practices.8 Although the randomized control trial (RCT) is unquestionably the best research tool to explore simple components of clinical care (i.e. tests, drugs, and procedures), its translation into daily clinical practice remains difficult.

Improving the process of care leading to quality remains an extremely difficult proposition based on such sociological issues as resistance to change, the need for interdisciplinary teamwork, level of support staff, economic factors, information retrieval inadequacies, and, most important, the complexity of patients with multiple comorbidities that do not fit the parameters of the RCT.

Don Berwick, MD, the lead author in the landmark IOM report and currently CMS administrator, has stated “in such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn.”9 Factors that cause this chasm include:10

- Too narrowly focused RCT;

- More required resources, including financial and personnel support with RCT, compared with usually clinical practices;

- Lack of collaboration between academic medical center researchers and community clinicians; and

- Lack of expertise and experience to undertake quality improvement in healthcare.

CER has received a $1.1 billion investment with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to provide evidence on the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of various treatment options.11 As part of this research to improve IOM’s goals to improve healthcare, better evidence is desperately needed to cross the translational gap between clinical research and the bedside.12 Observational outcome studies based on registries or databases derived primarily from clinical care can provide a powerful supplement to quality improvement.13

Thus, the ability to combine Medicare claims with other data through the Availability of Medicare Data for Performance Measurement would supply a wealth of information to potentially impact quality. As a cautionary note, safeguards such as provider review and appeal, monitoring the validity of the information, and only using the data for quality improvement are vital.

Dr. Holder is medical director of hospitalist services and chief medical information officer at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital. He is a member of Team Hospitalist.

CON

Unanswered questions, risks make CMS plan a bad idea

On June 8, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed a rule to allow “qualified entities” access to patient-protected Medicare data for provider performance publication. CMS allowed 60 days for public comment and a start date of Jan. 1, 2012. But this controversial rule appeared with short notice, little discussion, and abbreviated opportunity for comment.

CMS maintains this rule will result in higher quality and more cost-effective care. Considering the present volume of data published on multiple performance parameters for both hospitals and providers, it would seem prudent to have solid data for efficacy prior to implementing more required reporting and costs to the industry.1,2,3

Physicians and hospitals will have 30 days to review and verify three years of CMS claims data before it is released. The burden and cost of review will be borne by the private practices involved.1 This process will impose added administrative costs, and it is unlikely three years of data can be carefully reviewed in just 30 days. If practitioners find the review too cumbersome and expensive, which is likely, they will forgo review, putting the accuracy of the data in question.

Quality data already is published for both physicians and hospitals. Is there evidence this process will significantly increase transparency? Adding more layers of administrative work for both CMS and caregivers—higher overhead without defined benefit—seems an ill-conceived idea. From an evidence-based-practice standpoint, where is the evidence that this rule will improve “quality” and make care “cost-effective”? Have the risks (added bureaucracy, increased overhead, questionable data) and benefits (added transparency) been evaluated?

Additionally, it is unclear who will be monitoring the quality of the data published and who will provide oversight for the “entities” to ensure these data are fairly and accurately presented. Who will pay for this oversight, and what recourse will be afforded physicians and hospitals that feel they have been wronged?4,5

The “qualified entities” will pay CMS to cover their cost of providing data, raising concerns that this practice could evolve into patient-data “purchasing.” Although it is likely the selected entities will be industry leaders (or at least initially) with the capability to protect data, is this not another opportunity for misuse or corruption in the system?

Other issues not clearly addressed include the nature of the patient-protected information and who will interpret this data in a clinical context. How will these data be adjusted for patient comorbidities and case mix, or will the data be published without regard to these important confounders?1,3

Publishing clinical data for quality assurance and feedback purposes is essential for quality care. Transparency has increased consumer confidence in the healthcare system and, indeed, has increased the healthcare system’s responsiveness to quality concerns. Granting the benefits of transparency, published data must be precise, accurate, and managed with good oversight in order to ensure the process does not target providers or skew results. Another program, especially one being fast-tracked and making once-protected patient information available to unspecified entities, raises many questions. Who will be watching these agencies for a clear interpretation? Is this yet another layer of CMS bureaucracy? In an era of evidence-based medicine, where is the evidence that this program will improve the system for the better?

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

References

- Under the magnifying glass (again): CMS proposes new access to Medicare data for public provider performance reports. Bass, Berry and Sims website. Available at: http://www.bassberry.com/communicationscenter/newsletters/. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Controversial rule to allow access to Medicare data. Modern Health website. Available at: http://www.modernHealthcare.com. Accessed Aug. 31, 2011.

- Physician report cards must give correct grades. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/09/05/edsa0905.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- OIG identifies huge lapses in hospital security, shifts its focus from CMS to OCR. Atlantic Information Services Inc. website. Available at: http://www.AISHealth.com. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Berry M. Insurers mishandle 1 in 5 claims, AMA finds. American Medical News website. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2011/07/04/prl20704.htm. Accessed Sept. 12, 2011.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To error is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press; 1999.

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124-2134.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001:13.

- Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184.

- Ting HH, Shojania KG, Montori VM, Bradley EH. Quality improvement science and action. Circulation. 2009;119:1962-1974.

- Committee on Comparative Research Prioritization. Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington: National Academy Press; 2009.

- Sullivan P, Goldman D. The promise of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2011;305(4):400-401.

- Washington AE, Lipstein SH. The patient-centered outcomes research institute: promoting better information, decisions and health. Sept. 28, 2011; DOI: 10.10.1056/NEJMp1109407.

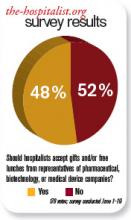

Should hospitalists accept gifts from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotech companies?

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

Should Patients Be Informed of Better Care Elsewhere?

Editors’ note: Hospitalists face difficult decisions every day, including situations that don’t always have clear-cut answers. Beginning with this month’s “HM Debate,” The Hospitalist stares down the tough questions and presents all sides of the issues. This month’s question: You are discharging a patient after treatment for a non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). The cardiology team recommends nonemergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for the patient’s three-vessel disease. You set up a referral for surgery, but you know the CABG morbidity and mortality rates are higher at your hospital than at a hospital 30 miles away. Should you disclose this information to your patient?

PRO

If you would tell your relative, you should tell your patient

If a patient at your hospital needs surgery or another invasive intervention, are you obligated to inform them of your hospital’s record with that procedure—particularly if the record is not as good as the one of the hospital down the street? Should loyalty to your hospital trump the risk to the patient?

In our scenario, the patient is being referred for elective surgery, and it is known that the cardiovascular team at a neighboring hospital has a better record for this procedure. It is the hospitalist’s job to present this information to the patient so that an intelligent and informed decision can be made. If the hospitalist believes the outcomes data, then an obligation exists to share that information with the patient.

If the data are subtle, one might argue that confusing the patient with more levels of decision-making is unnecessary. On the other hand, if data on performance outcomes between two institutions are clear, it presents an ethical position.

Let us assume the hospitalist is aware of poor outcomes in coronary bypass surgery at their hospital. Perhaps the mortality rates were unusually high and the hospitalist knew external consultants were brought in to identify the problems. Would you refer your patient for bypass surgery in that situation? A better question might be: Would you let a family member undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in your hospital? Probably not. So if you would inform a family member, shouldn’t you tell your patient?

A situation like this occurred in September 2005 at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester. Media coverage was intense, and statistics showed that thoracic surgery mortality at UMass was the highest in the state two years running. The service at the hospital was closed temporarily.1 Extensive reorganization, adoption of QI protocols, and development of oversight committees resulted in much-improved patient outcomes when the program reopened a few weeks later.

The higher-than-expected complication rate had persisted at UMass for four years before the closure and reorganization. One wonders if hospitalists and cardiologists suspected a problem with surgical outcomes before the hospital was thrust into the national spotlight. Is it our job to know our hospital’s track record in surgery and invasive procedures? Yes, it probably is. This is why a hospital’s quality-assurance committee is so important. As keeper of the outcomes data, the committee is charged with sounding an alarm when a problem is brewing.

Tech-savvy patients have access to detailed reporting on performance measures for hospitals and physicians. Interpretation of the data can be complex. High surgical complication rates might be the result of a higher-than-expected patient acuity mix—patients who were older and sicker than usual—and may not represent a system or surgeon problem. Hospitalists need to guide patients through the interpretation of this data.

Patients trust their physicians. They trust that hospitalists will provide the best advice and make recommendations with their interests at heart. To not do so violates the public trust in physicians as patient advocates. Required by law, transparency of hospital quality data is the basis of a truthful relationship between the healthcare system and the public.

HM’s reputation will be tarnished if patients perceive that the physicians are more interested in the well-being of the hospital than the well-being of the patients.

Reference

- Kowalczyk L, Smith S. Hospital halts heart surgeries due to deaths. Boston Globe Web site. Available at: www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2005/09/22/hospital_halts_heart_surgeries_due_to_deaths. Accessed March 31, 2009.

CON

Outcome disclosure is impractical, unnecessary

At first glance, disclosing information about better outcomes at another hospital seems reasonable—even ethically obligatory. However, there are several competing interests, and in the end, the existing precedent for requiring reasonable disclosure in informed consent makes more sense.

The first issue is practicality. How much is a hospitalist obligated to know, and what degree of difference must be disclosed? In the case example, the hospitalist knows better outcomes are available at a nearby facility. However, if a duty to disclose this information exists, it can’t be limited to the information that an individual hospitalist has available to them. If such a duty exists, there is a corresponding burden on providers to have consistent and accurate information to disclose. If disclosure of differing outcomes is the ethical standard, then the reasonable disclosure needs to meet some uniform criteria for when a differing outcome rises to the level that the disclosure is compelled.

Data exist for pneumonia outcomes, readmission rates, and medication errors, as well as data for physicians relative to their colleagues. The fact that a hospitalist might have incidental knowledge of differing outcomes is not sufficient to create an ethical obligation, but there must be some uniformity to a disclosure requirement.

It is easy to envision a hospitalist spending as much time disclosing outcomes data as disclosing medical information and prognosis in the process of obtaining informed consent. Hospitalists can’t be expected to manage all of that information, much less make a meaningful disclosure. Physicians’ information-management skills should focus on medical knowledge—not outcomes data.

The test case has more implications for the professionalism of the hospitalist. Ultimately, they should act in the best interest of the patient. The recommended course of treatment should maximize benefit and minimize harm. Enough information should be provided that the patient can participate in weighing risks and benefits. The hospitalist needs to decide if it is unsafe to perform the procedure at their institution, and if so, the patient should be referred out. If there is a small but real benefit to having the procedure done elsewhere, the hospitalist cannot be responsible for determining what threshold of incremental benefit warrants disclosure. Existing ethical responsibilities to protect the patient and act in their best interests already addresses the issues of disparate outcomes more effectively than a blanket disclosure policy. Patients need to trust their hospitalists, and we need to be worthy of that trust.

Mandating disclosure of better outcomes would create a conflict of interest for physicians and hospitals. This conflict would be difficult to manage. Large referral centers exist because physicians recognize their own limits and act in patients’ best interests. Requiring a new level of disclosure would mean that many hospitals (save for an elite few) would recommend patients go elsewhere a substantial part of the time.

Conflicts of interest usually are managed more than eliminated, and the current management of the tension between caring for a patient personally and referring them out based on a perception of the patient’s need for a higher level of care achieves a reasonable and balanced result. Disrupting this result with a mandated level of disclosure will result in disruption of a functional process.

Measured disclosure of relevant information is a good thing. A high level of communication and shared decision-making between physicians and patients is a good thing. Discussion of disparate outcomes may be an ethically important part of a treatment plan, but saying it is advisable in all cases is unnecessary, unmanageable, and inadvisable.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Society of Hospital Medicine or The Hospitalist.

Editors’ note: Hospitalists face difficult decisions every day, including situations that don’t always have clear-cut answers. Beginning with this month’s “HM Debate,” The Hospitalist stares down the tough questions and presents all sides of the issues. This month’s question: You are discharging a patient after treatment for a non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). The cardiology team recommends nonemergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for the patient’s three-vessel disease. You set up a referral for surgery, but you know the CABG morbidity and mortality rates are higher at your hospital than at a hospital 30 miles away. Should you disclose this information to your patient?

PRO

If you would tell your relative, you should tell your patient

If a patient at your hospital needs surgery or another invasive intervention, are you obligated to inform them of your hospital’s record with that procedure—particularly if the record is not as good as the one of the hospital down the street? Should loyalty to your hospital trump the risk to the patient?

In our scenario, the patient is being referred for elective surgery, and it is known that the cardiovascular team at a neighboring hospital has a better record for this procedure. It is the hospitalist’s job to present this information to the patient so that an intelligent and informed decision can be made. If the hospitalist believes the outcomes data, then an obligation exists to share that information with the patient.

If the data are subtle, one might argue that confusing the patient with more levels of decision-making is unnecessary. On the other hand, if data on performance outcomes between two institutions are clear, it presents an ethical position.

Let us assume the hospitalist is aware of poor outcomes in coronary bypass surgery at their hospital. Perhaps the mortality rates were unusually high and the hospitalist knew external consultants were brought in to identify the problems. Would you refer your patient for bypass surgery in that situation? A better question might be: Would you let a family member undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in your hospital? Probably not. So if you would inform a family member, shouldn’t you tell your patient?

A situation like this occurred in September 2005 at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester. Media coverage was intense, and statistics showed that thoracic surgery mortality at UMass was the highest in the state two years running. The service at the hospital was closed temporarily.1 Extensive reorganization, adoption of QI protocols, and development of oversight committees resulted in much-improved patient outcomes when the program reopened a few weeks later.

The higher-than-expected complication rate had persisted at UMass for four years before the closure and reorganization. One wonders if hospitalists and cardiologists suspected a problem with surgical outcomes before the hospital was thrust into the national spotlight. Is it our job to know our hospital’s track record in surgery and invasive procedures? Yes, it probably is. This is why a hospital’s quality-assurance committee is so important. As keeper of the outcomes data, the committee is charged with sounding an alarm when a problem is brewing.

Tech-savvy patients have access to detailed reporting on performance measures for hospitals and physicians. Interpretation of the data can be complex. High surgical complication rates might be the result of a higher-than-expected patient acuity mix—patients who were older and sicker than usual—and may not represent a system or surgeon problem. Hospitalists need to guide patients through the interpretation of this data.

Patients trust their physicians. They trust that hospitalists will provide the best advice and make recommendations with their interests at heart. To not do so violates the public trust in physicians as patient advocates. Required by law, transparency of hospital quality data is the basis of a truthful relationship between the healthcare system and the public.

HM’s reputation will be tarnished if patients perceive that the physicians are more interested in the well-being of the hospital than the well-being of the patients.

Reference

- Kowalczyk L, Smith S. Hospital halts heart surgeries due to deaths. Boston Globe Web site. Available at: www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2005/09/22/hospital_halts_heart_surgeries_due_to_deaths. Accessed March 31, 2009.

CON

Outcome disclosure is impractical, unnecessary

At first glance, disclosing information about better outcomes at another hospital seems reasonable—even ethically obligatory. However, there are several competing interests, and in the end, the existing precedent for requiring reasonable disclosure in informed consent makes more sense.

The first issue is practicality. How much is a hospitalist obligated to know, and what degree of difference must be disclosed? In the case example, the hospitalist knows better outcomes are available at a nearby facility. However, if a duty to disclose this information exists, it can’t be limited to the information that an individual hospitalist has available to them. If such a duty exists, there is a corresponding burden on providers to have consistent and accurate information to disclose. If disclosure of differing outcomes is the ethical standard, then the reasonable disclosure needs to meet some uniform criteria for when a differing outcome rises to the level that the disclosure is compelled.

Data exist for pneumonia outcomes, readmission rates, and medication errors, as well as data for physicians relative to their colleagues. The fact that a hospitalist might have incidental knowledge of differing outcomes is not sufficient to create an ethical obligation, but there must be some uniformity to a disclosure requirement.

It is easy to envision a hospitalist spending as much time disclosing outcomes data as disclosing medical information and prognosis in the process of obtaining informed consent. Hospitalists can’t be expected to manage all of that information, much less make a meaningful disclosure. Physicians’ information-management skills should focus on medical knowledge—not outcomes data.

The test case has more implications for the professionalism of the hospitalist. Ultimately, they should act in the best interest of the patient. The recommended course of treatment should maximize benefit and minimize harm. Enough information should be provided that the patient can participate in weighing risks and benefits. The hospitalist needs to decide if it is unsafe to perform the procedure at their institution, and if so, the patient should be referred out. If there is a small but real benefit to having the procedure done elsewhere, the hospitalist cannot be responsible for determining what threshold of incremental benefit warrants disclosure. Existing ethical responsibilities to protect the patient and act in their best interests already addresses the issues of disparate outcomes more effectively than a blanket disclosure policy. Patients need to trust their hospitalists, and we need to be worthy of that trust.

Mandating disclosure of better outcomes would create a conflict of interest for physicians and hospitals. This conflict would be difficult to manage. Large referral centers exist because physicians recognize their own limits and act in patients’ best interests. Requiring a new level of disclosure would mean that many hospitals (save for an elite few) would recommend patients go elsewhere a substantial part of the time.

Conflicts of interest usually are managed more than eliminated, and the current management of the tension between caring for a patient personally and referring them out based on a perception of the patient’s need for a higher level of care achieves a reasonable and balanced result. Disrupting this result with a mandated level of disclosure will result in disruption of a functional process.

Measured disclosure of relevant information is a good thing. A high level of communication and shared decision-making between physicians and patients is a good thing. Discussion of disparate outcomes may be an ethically important part of a treatment plan, but saying it is advisable in all cases is unnecessary, unmanageable, and inadvisable.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Society of Hospital Medicine or The Hospitalist.

Editors’ note: Hospitalists face difficult decisions every day, including situations that don’t always have clear-cut answers. Beginning with this month’s “HM Debate,” The Hospitalist stares down the tough questions and presents all sides of the issues. This month’s question: You are discharging a patient after treatment for a non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). The cardiology team recommends nonemergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for the patient’s three-vessel disease. You set up a referral for surgery, but you know the CABG morbidity and mortality rates are higher at your hospital than at a hospital 30 miles away. Should you disclose this information to your patient?

PRO

If you would tell your relative, you should tell your patient

If a patient at your hospital needs surgery or another invasive intervention, are you obligated to inform them of your hospital’s record with that procedure—particularly if the record is not as good as the one of the hospital down the street? Should loyalty to your hospital trump the risk to the patient?

In our scenario, the patient is being referred for elective surgery, and it is known that the cardiovascular team at a neighboring hospital has a better record for this procedure. It is the hospitalist’s job to present this information to the patient so that an intelligent and informed decision can be made. If the hospitalist believes the outcomes data, then an obligation exists to share that information with the patient.

If the data are subtle, one might argue that confusing the patient with more levels of decision-making is unnecessary. On the other hand, if data on performance outcomes between two institutions are clear, it presents an ethical position.

Let us assume the hospitalist is aware of poor outcomes in coronary bypass surgery at their hospital. Perhaps the mortality rates were unusually high and the hospitalist knew external consultants were brought in to identify the problems. Would you refer your patient for bypass surgery in that situation? A better question might be: Would you let a family member undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in your hospital? Probably not. So if you would inform a family member, shouldn’t you tell your patient?

A situation like this occurred in September 2005 at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester. Media coverage was intense, and statistics showed that thoracic surgery mortality at UMass was the highest in the state two years running. The service at the hospital was closed temporarily.1 Extensive reorganization, adoption of QI protocols, and development of oversight committees resulted in much-improved patient outcomes when the program reopened a few weeks later.

The higher-than-expected complication rate had persisted at UMass for four years before the closure and reorganization. One wonders if hospitalists and cardiologists suspected a problem with surgical outcomes before the hospital was thrust into the national spotlight. Is it our job to know our hospital’s track record in surgery and invasive procedures? Yes, it probably is. This is why a hospital’s quality-assurance committee is so important. As keeper of the outcomes data, the committee is charged with sounding an alarm when a problem is brewing.

Tech-savvy patients have access to detailed reporting on performance measures for hospitals and physicians. Interpretation of the data can be complex. High surgical complication rates might be the result of a higher-than-expected patient acuity mix—patients who were older and sicker than usual—and may not represent a system or surgeon problem. Hospitalists need to guide patients through the interpretation of this data.

Patients trust their physicians. They trust that hospitalists will provide the best advice and make recommendations with their interests at heart. To not do so violates the public trust in physicians as patient advocates. Required by law, transparency of hospital quality data is the basis of a truthful relationship between the healthcare system and the public.

HM’s reputation will be tarnished if patients perceive that the physicians are more interested in the well-being of the hospital than the well-being of the patients.

Reference

- Kowalczyk L, Smith S. Hospital halts heart surgeries due to deaths. Boston Globe Web site. Available at: www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2005/09/22/hospital_halts_heart_surgeries_due_to_deaths. Accessed March 31, 2009.

CON

Outcome disclosure is impractical, unnecessary

At first glance, disclosing information about better outcomes at another hospital seems reasonable—even ethically obligatory. However, there are several competing interests, and in the end, the existing precedent for requiring reasonable disclosure in informed consent makes more sense.

The first issue is practicality. How much is a hospitalist obligated to know, and what degree of difference must be disclosed? In the case example, the hospitalist knows better outcomes are available at a nearby facility. However, if a duty to disclose this information exists, it can’t be limited to the information that an individual hospitalist has available to them. If such a duty exists, there is a corresponding burden on providers to have consistent and accurate information to disclose. If disclosure of differing outcomes is the ethical standard, then the reasonable disclosure needs to meet some uniform criteria for when a differing outcome rises to the level that the disclosure is compelled.

Data exist for pneumonia outcomes, readmission rates, and medication errors, as well as data for physicians relative to their colleagues. The fact that a hospitalist might have incidental knowledge of differing outcomes is not sufficient to create an ethical obligation, but there must be some uniformity to a disclosure requirement.

It is easy to envision a hospitalist spending as much time disclosing outcomes data as disclosing medical information and prognosis in the process of obtaining informed consent. Hospitalists can’t be expected to manage all of that information, much less make a meaningful disclosure. Physicians’ information-management skills should focus on medical knowledge—not outcomes data.

The test case has more implications for the professionalism of the hospitalist. Ultimately, they should act in the best interest of the patient. The recommended course of treatment should maximize benefit and minimize harm. Enough information should be provided that the patient can participate in weighing risks and benefits. The hospitalist needs to decide if it is unsafe to perform the procedure at their institution, and if so, the patient should be referred out. If there is a small but real benefit to having the procedure done elsewhere, the hospitalist cannot be responsible for determining what threshold of incremental benefit warrants disclosure. Existing ethical responsibilities to protect the patient and act in their best interests already addresses the issues of disparate outcomes more effectively than a blanket disclosure policy. Patients need to trust their hospitalists, and we need to be worthy of that trust.

Mandating disclosure of better outcomes would create a conflict of interest for physicians and hospitals. This conflict would be difficult to manage. Large referral centers exist because physicians recognize their own limits and act in patients’ best interests. Requiring a new level of disclosure would mean that many hospitals (save for an elite few) would recommend patients go elsewhere a substantial part of the time.

Conflicts of interest usually are managed more than eliminated, and the current management of the tension between caring for a patient personally and referring them out based on a perception of the patient’s need for a higher level of care achieves a reasonable and balanced result. Disrupting this result with a mandated level of disclosure will result in disruption of a functional process.

Measured disclosure of relevant information is a good thing. A high level of communication and shared decision-making between physicians and patients is a good thing. Discussion of disparate outcomes may be an ethically important part of a treatment plan, but saying it is advisable in all cases is unnecessary, unmanageable, and inadvisable.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Society of Hospital Medicine or The Hospitalist.

Town & Gown

Centers of academia and learning have been physically located within urban communities since the time of the ancient Greeks. During the Middle Ages, church-supported universities were established in Italian cities, in Paris, and in Britain at Oxford. Typically, the university community resided in a sequestered segment of the city. As a result of financial endowment and protection granted by the Church, they were largely independent of civil laws and regulations.

In the Middle Ages, students and teachers wore gowns over their attire for warmth in the drafty libraries as well as to identify themselves as scholars; hence the distinction of “town,” a term referring to the townspeople, from “gown,” the people associated with the university.1 For a host of reasons, the traditional relationship between the local community and associated centers of academia has been one of suspicion and hostility.

Establishing Alliances

Over the years, better communication and cooperation between the academic communities and their host cities has eased some of these tensions and—in some cases—has resulted in positive and cordial relationships. Some academic institutions endeavor to contribute to the general community by providing access to evening study events and lectures and by inviting the community to participate in fine arts performances.

These overtures are welcome, but it is important to recognize the potential for universities to exert a dominating influence within a community. The impact of a university on the local community can vary, depending on the size and reputation of the university as well as the size of the town. A large, powerful university has a more profound influence when it is located in a moderate-size city (one with a population less than 250,000) than if it is located in a major metropolitan community. In this situation, the onus is upon the university to recognize its position with respect to the local community and its obligation to contribute to the general societal good.

Most universities recognize the value of establishing strong alliances and trusting relationships with their host communities. Located in Gainesville, Fla., a city with a population of 186,000, the University of Florida is a large university with a major medical school and a 576-bed teaching hospital. In response to community concerns about neighborhood issues, the university’s president appointed a University of Florida Town/Gown Task Force to identify problems and make recommendations to initiate change.2 The task force members included individuals representing the student body, the university faculty, and various representatives of the local community.

Other universities also recognize the importance of working together for the common good. Situated in a town of 13,000, South Carolina’s Clemson University, which has 17,100 students, developed a town-and-gown symposium in 2006 called Community Is a Contact Sport: Universities and Cities Reaching Common Ground. Designed to address neighborhood issues, it also provided a forum for concerns, as well as an opportunity for conflict resolution (www.clemson.edu/town-gown).

From Concern to Conflict

The conflict escalates on multiple levels when town-and-gown issues are set in the context of academic versus private practice medicine. University physicians and community doctors compete for the same patient population. Primary care physicians across the country have complained that when they refer their patients to academic teaching hospitals for specialized care, the patients are absorbed by the university hospitals. They complain that they are not afforded the courtesy of a follow-up letter, nor does the patient return to their care when the acute event is resolved.3 Private practice physicians and community-based hospitals provide important services and are necessary within any community. When the local, private medical community becomes concerned that a university-based medical center seeks to usurp their patients and their livelihood, a heated conflict may ensue.

University-based, research-oriented academic medical centers, with training programs involved in cutting edge technology and highly specialized patient care services, are clearly a positive adjunct to any local community’s—or state’s, for that matter—capability to provide top-notch patient care and services. No one can deny the benefits afforded by this level of expertise. Problems arise when university-based medical centers set a powerful and lustful gaze upon the medical community at large.

During the 1990s, large medical centers across the country bought up community hospitals and medical practices. At that time, and continuing into the present, office overhead—building costs, liability insurance, personnel costs—for private practice groups has often exceeded the ability of these primary care groups to survive. Not unexpectedly, once incorporated into the system, these practices are used to support the subspecialty services at the university medical center, bypassing the community-based subspecialty physicians.

Additionally, large, academic medical centers set up funded and university-supported subspecialty groups that compete head-on with independent practitioners. Private practitioners view these circumstances as stacked competition. The primary-care doctor’s decision in selecting a subspecialty doctor for a patient is no longer based on service, timeliness, and competence, but is instead a result of proscribed referral patterns delineated by the academic institution. Discriminatory referral patterns—not based on merit—result in local discontent, frustration, and unhealthy competition.

Short-Term Savings, Long-Term Loss

These issues are complex. A case can always be made to consolidate resources at the university hospital and avoid duplication of services by stripping away departments in the community hospitals. If pursued to its logical end, this operational model effectively starves community hospitals until they evolve into low acuity, “feeder” stations for the main academic hospital facility. On paper, this plan presents economic advantages. In practice, it not only deprives the metropolitan area of community-based hospital options, but it also results in a dwindling population base and the general decline and disenchantment of the local medical community. As the medical community contracts, so does the patient-base referral radius.

University-owned community hospitals are subject to the discretion of the university medical center. Decision making is attributed to maximum utilization of resources and certification of need, but most observers see the basic principle as economic: ways of garnering a larger portion of the healthcare dollar in the university coffers. Services and even departments provided by community hospitals are likewise subject to the benevolence of the university medical system. Hospitals function like living organisms: If a department such as pediatrics is withdrawn, the hospital continues—but with a limp. Few children can be seen and evaluated in the emergency department; likewise, high-risk obstetrics must be transferred to a major university hospital because the patient may need a neonatal intensive care unit. Hospitalists and internists who happen to be double boarded in medicine and pediatrics steer away from hospitals without a pediatric department. The changes are subtle but, over time, the effects of the loss are apparent.

Hospitalists need to be cognizant of these issues when pursuing employment opportunities. Many career-minded hospitalists seek employment in community-based, full-service hospitals with university medical center affiliations. This combination can provide the best of both worlds: autonomy, opportunities for growth and development, and opportunities for working with house staff and teaching. Checking the status of the relationship between the community hospital and the affiliated university medical center may be an important factor in pre-contract negotiations and decision-making for career hospitalists.

The Bottom Line

The turf battle between community medicine and academic medicine is primarily one of economics. Interesting parallels may be drawn between this conflict and the teachings of Adam Smith. Prior to Smith, economic theory was based on the idea that every dollar you have is one less dollar for me. Smith proposed an entirely different concept: If I help you earn dollars, the economic house will grow, and I, too, will make more dollars, and then you will make more dollars. In this way, the entire system generates more than anyone could have previously imagined. This economic concept extrapolates well to the present discussion of the university medical center versus community medicine.

University health systems do not seem to realize that real growth happens when communities grow together. A robust and vibrant community hospital supports a university medical center with more vigor than an anemic, waning, and disenchanted community hospital that perceives its woes as a result of the powerful—and perhaps dogmatic—university health system. There are enough patients to grow both systems together—the patient base radius grows wider with cooperation and growth—but this cannot happen if the university engenders distrust among local practitioners and the local community. This is a situation that will either be win-win or lose-lose.

Although the crux of the conflict is economic, other aspects of town-and-gown medicine can contribute to better cooperation and understanding. Some academic medical centers have explored ways to incorporate local physicians in university-based clinical trials. These programs offer cutting edge medicine and an opportunity to participate in intellectually stimulating work; at the same time, physicians retain their private practices.

This research opportunity is being offered and supported by a number of academic institutions, including Columbia-Presbyterian in New York City, Duke in Durham, N.C., Partners HealthCare in Boston, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and Washington University (St. Louis, Mo.).4 This is a good-faith start in mending the relationship between the academic and private medical sectors. To achieve a lasting positive relationship, community physicians must trust the academic community to respect their autonomy and to recognize that they have the right to provide full-service care to their patients and to serve their patients without the fear of being unfairly disenfranchised.

The lack of integration of the academic medical community and private practitioners of medicine—the proverbial town and gown—is an old dilemma. It is time to lay it to rest. The solutions are straightforward. Empowering community hospitals and physicians will not diminish the influence of university-based hospitals, nor will there be loss of reimbursement. Just the opposite will occur. In the end, with cooperation, everyone wins; with adversarial actions, all parties lose, especially the patients. TH

Dr. Brezina is a member of the consulting clinical faculty at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

References

- Town and gown in the Middle Ages. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Town_and_gown. Last accessed March 29, 2007.

- University of Florida Web site. Town/gown task force. Available at: www.facilities.ufl.edu/cp/towngown.htm. Last accessed March 29, 2007.

- Adams D, Croasdale M. Town and gown: turning rivalries into relationships [American Medical News Web site]. January 13, 2003. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2003/01/13/prsa0113.htm. Last accessed March 20, 2007.

- Maguire P. Marriage of town and gown brings clinical research to busy practices [ACP-ASIM Observer Web site]. February 2001. Available at: www.acponline.org/journals/news/feb01/clinresearch.htm. Last accessed March 20, 2007.

Centers of academia and learning have been physically located within urban communities since the time of the ancient Greeks. During the Middle Ages, church-supported universities were established in Italian cities, in Paris, and in Britain at Oxford. Typically, the university community resided in a sequestered segment of the city. As a result of financial endowment and protection granted by the Church, they were largely independent of civil laws and regulations.

In the Middle Ages, students and teachers wore gowns over their attire for warmth in the drafty libraries as well as to identify themselves as scholars; hence the distinction of “town,” a term referring to the townspeople, from “gown,” the people associated with the university.1 For a host of reasons, the traditional relationship between the local community and associated centers of academia has been one of suspicion and hostility.

Establishing Alliances

Over the years, better communication and cooperation between the academic communities and their host cities has eased some of these tensions and—in some cases—has resulted in positive and cordial relationships. Some academic institutions endeavor to contribute to the general community by providing access to evening study events and lectures and by inviting the community to participate in fine arts performances.

These overtures are welcome, but it is important to recognize the potential for universities to exert a dominating influence within a community. The impact of a university on the local community can vary, depending on the size and reputation of the university as well as the size of the town. A large, powerful university has a more profound influence when it is located in a moderate-size city (one with a population less than 250,000) than if it is located in a major metropolitan community. In this situation, the onus is upon the university to recognize its position with respect to the local community and its obligation to contribute to the general societal good.

Most universities recognize the value of establishing strong alliances and trusting relationships with their host communities. Located in Gainesville, Fla., a city with a population of 186,000, the University of Florida is a large university with a major medical school and a 576-bed teaching hospital. In response to community concerns about neighborhood issues, the university’s president appointed a University of Florida Town/Gown Task Force to identify problems and make recommendations to initiate change.2 The task force members included individuals representing the student body, the university faculty, and various representatives of the local community.

Other universities also recognize the importance of working together for the common good. Situated in a town of 13,000, South Carolina’s Clemson University, which has 17,100 students, developed a town-and-gown symposium in 2006 called Community Is a Contact Sport: Universities and Cities Reaching Common Ground. Designed to address neighborhood issues, it also provided a forum for concerns, as well as an opportunity for conflict resolution (www.clemson.edu/town-gown).

From Concern to Conflict

The conflict escalates on multiple levels when town-and-gown issues are set in the context of academic versus private practice medicine. University physicians and community doctors compete for the same patient population. Primary care physicians across the country have complained that when they refer their patients to academic teaching hospitals for specialized care, the patients are absorbed by the university hospitals. They complain that they are not afforded the courtesy of a follow-up letter, nor does the patient return to their care when the acute event is resolved.3 Private practice physicians and community-based hospitals provide important services and are necessary within any community. When the local, private medical community becomes concerned that a university-based medical center seeks to usurp their patients and their livelihood, a heated conflict may ensue.

University-based, research-oriented academic medical centers, with training programs involved in cutting edge technology and highly specialized patient care services, are clearly a positive adjunct to any local community’s—or state’s, for that matter—capability to provide top-notch patient care and services. No one can deny the benefits afforded by this level of expertise. Problems arise when university-based medical centers set a powerful and lustful gaze upon the medical community at large.