User login

Newer 3D lung models starting to remake research

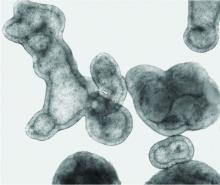

Pulmonologist-scientist Veena B. Antony, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, grows “pulmospheres” in her lab. The tiny spheres, about 1 mL in diameter, contain cells representing all of the cell types in a lung struck with pulmonary fibrosis.

They are a three-dimensional model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) that can be used to study the behavior of invasive myofibroblasts and to predict in vivo responsiveness to antifibrotic drugs;

“The utility is extensive, including looking at the impact of early-life exposures on mid-life lung disease. We can ask all kinds of questions and answer them much faster, and with more accuracy, than with any 2D model,” said Dr. Antony, also professor of environmental health sciences and director of UAB’s program for environmental and translational medicine.

“The future of 3D modeling of the lung will happen step by step ... but we’re right at the edge of a prime explosion of information coming from these models, in all kinds of lung diseases,” she said.

Two-dimensional model systems – mainly monolayer cell cultures where cells adhere to and grow on a plate – cannot approximate the variety of cell types and architecture found in tissue, nor can they recapitulate cell-cell communication, biochemical cues, and other factors that are key to lung development and the pathogenesis of disease.

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres resemble what have come to be known as organoids – 3D tissue cultures emanating from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or adult stem cells, in which multiple cell types self-organize, usually while suspended in natural or synthetic extracellular matrix (with or without a scaffold of some kind).

Lung-on-a-chip

In lung-on-a-chip (LOC) models, multiple cell types are seeded into miniature chambers, or “chips,” that contain networks of microfabricated channels designed to deliver and remove fluids, chemical cues, oxygen, and biomechanical forces. LOCs and other organs-on-chips – also called tissues-on-chips – can be continuously perfused and are highly structured and precisely controlled.

It’s the organs-on-chip model – or potential fusions of the organoid and organs-on-chip models – that will likely impact drug development. Almost 9 out of 10 investigational drugs fail in clinical trials – approximately 60% because of lack of efficacy and 30% because of toxicity. More reliable and predictive preclinical investigation is key, said Danilo A. Tagle, PhD, director of the Office of Special Initiatives in the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, of the National Institutes of Health.

“We have so many candidate drugs that go through preclinical safety testing, and that do relatively well in animal studies of efficacy, but then fail in clinical trials,” Dr. Tagle said. “We need better preclinical models.”

In its 10 years of life, the Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program led by the NCATS – and funded by the NIH and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – has shown that organs-on-chips can be used to model disease and to predict both the safety and efficacy of clinical compounds, he said.

Lung organoids

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres emanate not from stem cells but from primary tissue obtained from diseased lung. “We reconstitute the lung cells in single-cell suspensions, and then we allow them to come back together to form lung tissue,” she said. The pulmospheres take about 3 days to grow.

In a study published 5 years ago of pulmospheres of 20 patients with IPF and 9 control subjects, Dr. Antony and colleagues quantitated invasiveness and found “remarkable” differences in the invasiveness of IPF pulmospheres following exposure to the Food and Drug Administration–approved antifibrotic drugs nintedanib and pirfenidone. Some pulmospheres responded to one or the other drug, some to both, and two to neither – findings that Dr. Antony said offer hope for the goals of personalizing therapy and assessing new drugs.

Moreover, clinical disease progression correlated with invasiveness of the pulmospheres, showing that the organoid-like structures “do give us a model that [reflects] what’s happening in the clinical setting,” she said. (Lung tissue for the study was obtained via video-assisted thoracic surgery biopsy of IPF patients and from failed donor lung explants, but bronchoscopic forceps biopsies have become a useful method for obtaining tissue.)

The pulmospheres are not yet in clinical use, Dr. Antony said, but her lab is testing other fibrosis modifiers and continuing to use the model as a research tool.

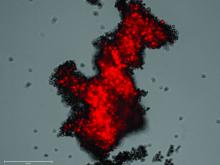

One state to the east, at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., Amanda Linkous, PhD, grows “branching lung organoids” and brain organoids to study the biology of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

“We want to understand how [SCLC] cells change in the primary organ site, compared with metastatic sites like the brain. ... Are different transcription factors expressed [for instance] depending on where the tumor is growing?” said Dr. Linkous, scientific center manager of the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Systems Biology of SCLC at Vanderbilt. “Then we hope to start drug screening within the next year.”

Her lung organoids take shape from either human embryonic stem cells or iPSCs. Within commercially available media, the cells mature through several stages of differentiation, forming definitive endoderm, anterior foregut endoderm, and then circular lung bud structures – the latter of which are then placed into droplets of Matrigel, an extracellular matrix gel.

“In the Matrigel droplets, the lung bud cells will develop proximal and distal-like branching structures that express things like EPCAM, MUC1, SOX2, SOX9, and NKX2.1 – key markers that you should see in a more mature lung microenvironment,” she said. Tumor cells from established SCLC cell lines will then easily invade the branching lung organoid.

Dr. Linkous said she has found her organoid models highly reproducible and values their long-lasting nature – especially for future drug screening. “We can keep organoids going for months at a time,” said Dr. Linkous, a research associate professor in Vanderbilt’s department of biochemistry.

Like Dr. Antony, she envisions personalizing treatment in the future. “SCLC is a very heterogeneous tumor with many different cell types, so what works for one patient may not work well at all for another patient,” she said.

As recently as 5 years ago, “many in the cancer field would have been resistant to moving away from mouse models,” Dr. Linkous noted. “But preclinical studies in mice often don’t pan out in the clinic ... so we’re moving toward a human microenvironment to study human disease.”

The greatest challenge, Dr. Linkous and Dr. Antony said, lies in integrating both vascular blood flow and air into these models. “We just don’t have that combination as of yet,” Dr. Antony said.

LOC models

One of the first LOC models – and a galvanizing event for organs-on-chips more broadly – was a 1- to 2-cm–long model of the alveolar-capillary interface developed at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Microchannels ran alongside a porous membrane coated with extracellular matrix, with alveolar cells seeded on one side and lung endothelial cells on the other side. When a vacuum was applied rhythmically to the channels, the cell-lined membrane stretched and relaxed, mimicking breathing movements.

Lead investigator Dongeun (Dan) Huh, PhD, then a postdoctoral student working with Donald E. Ingber, MD, PhD, founding director of the institute, ran tests showing that the model could reproduce organ-level responses to bacteria and inflammatory cytokines, as well as to silica nanoparticles. The widely cited paper was published in 2010 (Science. 2010;328[5986]:1662-8), and was followed by another study published in 2012 (Sci Transl Med. 2012;4[159]:159ra147) that used the LOC device to reproduce drug toxicity–induced pulmonary edema. “Here we were demonstrating for the first time that we could use the lung-on-chip to model human lung disease,” said Dr. Huh, who started his own lab at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in 2013.

Since then, “as a field we’ve come a long way in modeling the complexity of human lung tissues ... with more advanced devices that can be used to mimic different parts of the lung and different processes, like immune responses in asthma and viral infections,” said Dr. Huh, “and with several studies using primary human cells taken from lung disease patients.”

Among Dr. Huh’s latest devices, built with NIH funding, is an asthma-on-a-chip device. Lung cells isolated from asthma patients are grown in a microfabricated device to create multilayered airway tissue, with airspace, that contains a fully differentiated epithelium and a vascularized stroma. “We can compress the entire engineered area of asthmatic human tissue in a lateral direction to mimic bronchoconstriction that happens during an asthma attack,” he said.

A paper soon to be published will describe how “abnormal pathophysiologic compressive forces due to bronchoconstriction in asthmatic lungs can make the lungs fibrotic, and how those mechanical forces also can induce increased vascularity,” said Dr. Huh, associate professor in the university’s department of bioengineering. “The increased vascular density can also change the phenotype of blood vessels in asthmatic airways.”

Dr. Huh also has an $8.3 million contract with the government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority to study how chlorine gas damages lung tissues and identify biomarkers of chlorine gas–induced lung injury, with the goal of developing therapeutics.

Dr. Ingber and associates have developed a device modeling cystic fibrosis (CF). The chip is lined with primary human CF bronchial epithelial cells grown under an air-liquid interface and interfaced with primary lung microvascular endothelium that are exposed to fluid flow.

The chip reproduced, “with high fidelity, many of the structural, biochemical, and pathophysiological features of the human CF lung airway and its response to pathogens and circulating immune cells in vitro,” Dr. Ingber and colleagues reported (J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21:605-15).

Government investment in tissue chips

Efforts to commercialize organs-on-chip platforms and translate them for nonengineers have also picked in recent years. Several companies in the United States (including Emulate, a Wyss start-up) and in Europe now offer microengineered lung tissue models that can be used for research and drug testing. And some large pharmaceutical companies, said Dr. Tagle, have begun integrating tissue chip technology into their drug development programs.

The FDA, meanwhile, “has come to embrace the technology and see its promise,” Dr. Tagle said. An FDA pilot program announced in 2021 – called ISTAND (Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs) – allows for tissue chip data to be submitted, as standalone data, for some drug applications.

The first 5 years of the government’s Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program focused on safety and toxicity, and it “was successful in that model organ systems were able to capture the human response that [had been missed in] animal models,” he said.

For example, when a liver-tissue model was used to test several compounds that had passed animal testing for toxicity/safety but then failed in human clinical trials – killing some of the participants – the model showed a 100% sensitivity and a 87% specificity in predicting the human response, said Dr. Tagle, who recently coauthored a review on the future of organs-on-chips (Nature Reviews I Drug Discovery. 2021;20:345-61).

The second 5 years of the program, currently winding down, have focused on efficacy – the ability of organs-on-chip models to recreate the pathophysiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, influenza, and other diseases, so that potential drugs can be assessed. In 2020, with extra support from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, NCATS funded academic labs to use organs-on-chip technology to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 and potential therapeutics.

Dr. Ingbar was one of the grantees. His team screened a number of FDA-approved drugs for potential repurposing using a bronchial-airway-on-a-chip and compared results with 2D model systems (Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:815-29). Amodiaquine inhibited infection in the 3D model and is now in phase 2 COVID trials. Several other drugs showed effectiveness in a 2D model but not in the chip.

Now, in a next phase of study at NCATS, coined Clinical Trials on a Chip, the center has awarded $35.5 million for investigators to test candidate therapies, often in parallel to ongoing clinical trials. The hope is that organs-on-chips can improve clinical trial design, from enrollment criteria and patient stratification to endpoints and the use of biomarkers. And in his lab, Dr. Huh is now engineering a shift to “organoids-on-a-chip” that combines the best features of each approach. “The idea,” he said, “is to grow organoids, and maintain the organoids in the microengineered systems where we can control their environment better ... and apply cues to allow them to develop into even more realistic tissues.”

Drs. Antony, Linkous, and Tagle reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Huh is a co-founder of Vivodyne Inc, and owns shares in Vivodyne Inc. and Emulate Inc.

Pulmonologist-scientist Veena B. Antony, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, grows “pulmospheres” in her lab. The tiny spheres, about 1 mL in diameter, contain cells representing all of the cell types in a lung struck with pulmonary fibrosis.

They are a three-dimensional model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) that can be used to study the behavior of invasive myofibroblasts and to predict in vivo responsiveness to antifibrotic drugs;

“The utility is extensive, including looking at the impact of early-life exposures on mid-life lung disease. We can ask all kinds of questions and answer them much faster, and with more accuracy, than with any 2D model,” said Dr. Antony, also professor of environmental health sciences and director of UAB’s program for environmental and translational medicine.

“The future of 3D modeling of the lung will happen step by step ... but we’re right at the edge of a prime explosion of information coming from these models, in all kinds of lung diseases,” she said.

Two-dimensional model systems – mainly monolayer cell cultures where cells adhere to and grow on a plate – cannot approximate the variety of cell types and architecture found in tissue, nor can they recapitulate cell-cell communication, biochemical cues, and other factors that are key to lung development and the pathogenesis of disease.

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres resemble what have come to be known as organoids – 3D tissue cultures emanating from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or adult stem cells, in which multiple cell types self-organize, usually while suspended in natural or synthetic extracellular matrix (with or without a scaffold of some kind).

Lung-on-a-chip

In lung-on-a-chip (LOC) models, multiple cell types are seeded into miniature chambers, or “chips,” that contain networks of microfabricated channels designed to deliver and remove fluids, chemical cues, oxygen, and biomechanical forces. LOCs and other organs-on-chips – also called tissues-on-chips – can be continuously perfused and are highly structured and precisely controlled.

It’s the organs-on-chip model – or potential fusions of the organoid and organs-on-chip models – that will likely impact drug development. Almost 9 out of 10 investigational drugs fail in clinical trials – approximately 60% because of lack of efficacy and 30% because of toxicity. More reliable and predictive preclinical investigation is key, said Danilo A. Tagle, PhD, director of the Office of Special Initiatives in the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, of the National Institutes of Health.

“We have so many candidate drugs that go through preclinical safety testing, and that do relatively well in animal studies of efficacy, but then fail in clinical trials,” Dr. Tagle said. “We need better preclinical models.”

In its 10 years of life, the Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program led by the NCATS – and funded by the NIH and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – has shown that organs-on-chips can be used to model disease and to predict both the safety and efficacy of clinical compounds, he said.

Lung organoids

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres emanate not from stem cells but from primary tissue obtained from diseased lung. “We reconstitute the lung cells in single-cell suspensions, and then we allow them to come back together to form lung tissue,” she said. The pulmospheres take about 3 days to grow.

In a study published 5 years ago of pulmospheres of 20 patients with IPF and 9 control subjects, Dr. Antony and colleagues quantitated invasiveness and found “remarkable” differences in the invasiveness of IPF pulmospheres following exposure to the Food and Drug Administration–approved antifibrotic drugs nintedanib and pirfenidone. Some pulmospheres responded to one or the other drug, some to both, and two to neither – findings that Dr. Antony said offer hope for the goals of personalizing therapy and assessing new drugs.

Moreover, clinical disease progression correlated with invasiveness of the pulmospheres, showing that the organoid-like structures “do give us a model that [reflects] what’s happening in the clinical setting,” she said. (Lung tissue for the study was obtained via video-assisted thoracic surgery biopsy of IPF patients and from failed donor lung explants, but bronchoscopic forceps biopsies have become a useful method for obtaining tissue.)

The pulmospheres are not yet in clinical use, Dr. Antony said, but her lab is testing other fibrosis modifiers and continuing to use the model as a research tool.

One state to the east, at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., Amanda Linkous, PhD, grows “branching lung organoids” and brain organoids to study the biology of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

“We want to understand how [SCLC] cells change in the primary organ site, compared with metastatic sites like the brain. ... Are different transcription factors expressed [for instance] depending on where the tumor is growing?” said Dr. Linkous, scientific center manager of the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Systems Biology of SCLC at Vanderbilt. “Then we hope to start drug screening within the next year.”

Her lung organoids take shape from either human embryonic stem cells or iPSCs. Within commercially available media, the cells mature through several stages of differentiation, forming definitive endoderm, anterior foregut endoderm, and then circular lung bud structures – the latter of which are then placed into droplets of Matrigel, an extracellular matrix gel.

“In the Matrigel droplets, the lung bud cells will develop proximal and distal-like branching structures that express things like EPCAM, MUC1, SOX2, SOX9, and NKX2.1 – key markers that you should see in a more mature lung microenvironment,” she said. Tumor cells from established SCLC cell lines will then easily invade the branching lung organoid.

Dr. Linkous said she has found her organoid models highly reproducible and values their long-lasting nature – especially for future drug screening. “We can keep organoids going for months at a time,” said Dr. Linkous, a research associate professor in Vanderbilt’s department of biochemistry.

Like Dr. Antony, she envisions personalizing treatment in the future. “SCLC is a very heterogeneous tumor with many different cell types, so what works for one patient may not work well at all for another patient,” she said.

As recently as 5 years ago, “many in the cancer field would have been resistant to moving away from mouse models,” Dr. Linkous noted. “But preclinical studies in mice often don’t pan out in the clinic ... so we’re moving toward a human microenvironment to study human disease.”

The greatest challenge, Dr. Linkous and Dr. Antony said, lies in integrating both vascular blood flow and air into these models. “We just don’t have that combination as of yet,” Dr. Antony said.

LOC models

One of the first LOC models – and a galvanizing event for organs-on-chips more broadly – was a 1- to 2-cm–long model of the alveolar-capillary interface developed at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Microchannels ran alongside a porous membrane coated with extracellular matrix, with alveolar cells seeded on one side and lung endothelial cells on the other side. When a vacuum was applied rhythmically to the channels, the cell-lined membrane stretched and relaxed, mimicking breathing movements.

Lead investigator Dongeun (Dan) Huh, PhD, then a postdoctoral student working with Donald E. Ingber, MD, PhD, founding director of the institute, ran tests showing that the model could reproduce organ-level responses to bacteria and inflammatory cytokines, as well as to silica nanoparticles. The widely cited paper was published in 2010 (Science. 2010;328[5986]:1662-8), and was followed by another study published in 2012 (Sci Transl Med. 2012;4[159]:159ra147) that used the LOC device to reproduce drug toxicity–induced pulmonary edema. “Here we were demonstrating for the first time that we could use the lung-on-chip to model human lung disease,” said Dr. Huh, who started his own lab at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in 2013.

Since then, “as a field we’ve come a long way in modeling the complexity of human lung tissues ... with more advanced devices that can be used to mimic different parts of the lung and different processes, like immune responses in asthma and viral infections,” said Dr. Huh, “and with several studies using primary human cells taken from lung disease patients.”

Among Dr. Huh’s latest devices, built with NIH funding, is an asthma-on-a-chip device. Lung cells isolated from asthma patients are grown in a microfabricated device to create multilayered airway tissue, with airspace, that contains a fully differentiated epithelium and a vascularized stroma. “We can compress the entire engineered area of asthmatic human tissue in a lateral direction to mimic bronchoconstriction that happens during an asthma attack,” he said.

A paper soon to be published will describe how “abnormal pathophysiologic compressive forces due to bronchoconstriction in asthmatic lungs can make the lungs fibrotic, and how those mechanical forces also can induce increased vascularity,” said Dr. Huh, associate professor in the university’s department of bioengineering. “The increased vascular density can also change the phenotype of blood vessels in asthmatic airways.”

Dr. Huh also has an $8.3 million contract with the government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority to study how chlorine gas damages lung tissues and identify biomarkers of chlorine gas–induced lung injury, with the goal of developing therapeutics.

Dr. Ingber and associates have developed a device modeling cystic fibrosis (CF). The chip is lined with primary human CF bronchial epithelial cells grown under an air-liquid interface and interfaced with primary lung microvascular endothelium that are exposed to fluid flow.

The chip reproduced, “with high fidelity, many of the structural, biochemical, and pathophysiological features of the human CF lung airway and its response to pathogens and circulating immune cells in vitro,” Dr. Ingber and colleagues reported (J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21:605-15).

Government investment in tissue chips

Efforts to commercialize organs-on-chip platforms and translate them for nonengineers have also picked in recent years. Several companies in the United States (including Emulate, a Wyss start-up) and in Europe now offer microengineered lung tissue models that can be used for research and drug testing. And some large pharmaceutical companies, said Dr. Tagle, have begun integrating tissue chip technology into their drug development programs.

The FDA, meanwhile, “has come to embrace the technology and see its promise,” Dr. Tagle said. An FDA pilot program announced in 2021 – called ISTAND (Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs) – allows for tissue chip data to be submitted, as standalone data, for some drug applications.

The first 5 years of the government’s Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program focused on safety and toxicity, and it “was successful in that model organ systems were able to capture the human response that [had been missed in] animal models,” he said.

For example, when a liver-tissue model was used to test several compounds that had passed animal testing for toxicity/safety but then failed in human clinical trials – killing some of the participants – the model showed a 100% sensitivity and a 87% specificity in predicting the human response, said Dr. Tagle, who recently coauthored a review on the future of organs-on-chips (Nature Reviews I Drug Discovery. 2021;20:345-61).

The second 5 years of the program, currently winding down, have focused on efficacy – the ability of organs-on-chip models to recreate the pathophysiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, influenza, and other diseases, so that potential drugs can be assessed. In 2020, with extra support from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, NCATS funded academic labs to use organs-on-chip technology to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 and potential therapeutics.

Dr. Ingbar was one of the grantees. His team screened a number of FDA-approved drugs for potential repurposing using a bronchial-airway-on-a-chip and compared results with 2D model systems (Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:815-29). Amodiaquine inhibited infection in the 3D model and is now in phase 2 COVID trials. Several other drugs showed effectiveness in a 2D model but not in the chip.

Now, in a next phase of study at NCATS, coined Clinical Trials on a Chip, the center has awarded $35.5 million for investigators to test candidate therapies, often in parallel to ongoing clinical trials. The hope is that organs-on-chips can improve clinical trial design, from enrollment criteria and patient stratification to endpoints and the use of biomarkers. And in his lab, Dr. Huh is now engineering a shift to “organoids-on-a-chip” that combines the best features of each approach. “The idea,” he said, “is to grow organoids, and maintain the organoids in the microengineered systems where we can control their environment better ... and apply cues to allow them to develop into even more realistic tissues.”

Drs. Antony, Linkous, and Tagle reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Huh is a co-founder of Vivodyne Inc, and owns shares in Vivodyne Inc. and Emulate Inc.

Pulmonologist-scientist Veena B. Antony, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, grows “pulmospheres” in her lab. The tiny spheres, about 1 mL in diameter, contain cells representing all of the cell types in a lung struck with pulmonary fibrosis.

They are a three-dimensional model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) that can be used to study the behavior of invasive myofibroblasts and to predict in vivo responsiveness to antifibrotic drugs;

“The utility is extensive, including looking at the impact of early-life exposures on mid-life lung disease. We can ask all kinds of questions and answer them much faster, and with more accuracy, than with any 2D model,” said Dr. Antony, also professor of environmental health sciences and director of UAB’s program for environmental and translational medicine.

“The future of 3D modeling of the lung will happen step by step ... but we’re right at the edge of a prime explosion of information coming from these models, in all kinds of lung diseases,” she said.

Two-dimensional model systems – mainly monolayer cell cultures where cells adhere to and grow on a plate – cannot approximate the variety of cell types and architecture found in tissue, nor can they recapitulate cell-cell communication, biochemical cues, and other factors that are key to lung development and the pathogenesis of disease.

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres resemble what have come to be known as organoids – 3D tissue cultures emanating from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or adult stem cells, in which multiple cell types self-organize, usually while suspended in natural or synthetic extracellular matrix (with or without a scaffold of some kind).

Lung-on-a-chip

In lung-on-a-chip (LOC) models, multiple cell types are seeded into miniature chambers, or “chips,” that contain networks of microfabricated channels designed to deliver and remove fluids, chemical cues, oxygen, and biomechanical forces. LOCs and other organs-on-chips – also called tissues-on-chips – can be continuously perfused and are highly structured and precisely controlled.

It’s the organs-on-chip model – or potential fusions of the organoid and organs-on-chip models – that will likely impact drug development. Almost 9 out of 10 investigational drugs fail in clinical trials – approximately 60% because of lack of efficacy and 30% because of toxicity. More reliable and predictive preclinical investigation is key, said Danilo A. Tagle, PhD, director of the Office of Special Initiatives in the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, of the National Institutes of Health.

“We have so many candidate drugs that go through preclinical safety testing, and that do relatively well in animal studies of efficacy, but then fail in clinical trials,” Dr. Tagle said. “We need better preclinical models.”

In its 10 years of life, the Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program led by the NCATS – and funded by the NIH and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – has shown that organs-on-chips can be used to model disease and to predict both the safety and efficacy of clinical compounds, he said.

Lung organoids

Dr. Antony’s pulmospheres emanate not from stem cells but from primary tissue obtained from diseased lung. “We reconstitute the lung cells in single-cell suspensions, and then we allow them to come back together to form lung tissue,” she said. The pulmospheres take about 3 days to grow.

In a study published 5 years ago of pulmospheres of 20 patients with IPF and 9 control subjects, Dr. Antony and colleagues quantitated invasiveness and found “remarkable” differences in the invasiveness of IPF pulmospheres following exposure to the Food and Drug Administration–approved antifibrotic drugs nintedanib and pirfenidone. Some pulmospheres responded to one or the other drug, some to both, and two to neither – findings that Dr. Antony said offer hope for the goals of personalizing therapy and assessing new drugs.

Moreover, clinical disease progression correlated with invasiveness of the pulmospheres, showing that the organoid-like structures “do give us a model that [reflects] what’s happening in the clinical setting,” she said. (Lung tissue for the study was obtained via video-assisted thoracic surgery biopsy of IPF patients and from failed donor lung explants, but bronchoscopic forceps biopsies have become a useful method for obtaining tissue.)

The pulmospheres are not yet in clinical use, Dr. Antony said, but her lab is testing other fibrosis modifiers and continuing to use the model as a research tool.

One state to the east, at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., Amanda Linkous, PhD, grows “branching lung organoids” and brain organoids to study the biology of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

“We want to understand how [SCLC] cells change in the primary organ site, compared with metastatic sites like the brain. ... Are different transcription factors expressed [for instance] depending on where the tumor is growing?” said Dr. Linkous, scientific center manager of the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Systems Biology of SCLC at Vanderbilt. “Then we hope to start drug screening within the next year.”

Her lung organoids take shape from either human embryonic stem cells or iPSCs. Within commercially available media, the cells mature through several stages of differentiation, forming definitive endoderm, anterior foregut endoderm, and then circular lung bud structures – the latter of which are then placed into droplets of Matrigel, an extracellular matrix gel.

“In the Matrigel droplets, the lung bud cells will develop proximal and distal-like branching structures that express things like EPCAM, MUC1, SOX2, SOX9, and NKX2.1 – key markers that you should see in a more mature lung microenvironment,” she said. Tumor cells from established SCLC cell lines will then easily invade the branching lung organoid.

Dr. Linkous said she has found her organoid models highly reproducible and values their long-lasting nature – especially for future drug screening. “We can keep organoids going for months at a time,” said Dr. Linkous, a research associate professor in Vanderbilt’s department of biochemistry.

Like Dr. Antony, she envisions personalizing treatment in the future. “SCLC is a very heterogeneous tumor with many different cell types, so what works for one patient may not work well at all for another patient,” she said.

As recently as 5 years ago, “many in the cancer field would have been resistant to moving away from mouse models,” Dr. Linkous noted. “But preclinical studies in mice often don’t pan out in the clinic ... so we’re moving toward a human microenvironment to study human disease.”

The greatest challenge, Dr. Linkous and Dr. Antony said, lies in integrating both vascular blood flow and air into these models. “We just don’t have that combination as of yet,” Dr. Antony said.

LOC models

One of the first LOC models – and a galvanizing event for organs-on-chips more broadly – was a 1- to 2-cm–long model of the alveolar-capillary interface developed at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Microchannels ran alongside a porous membrane coated with extracellular matrix, with alveolar cells seeded on one side and lung endothelial cells on the other side. When a vacuum was applied rhythmically to the channels, the cell-lined membrane stretched and relaxed, mimicking breathing movements.

Lead investigator Dongeun (Dan) Huh, PhD, then a postdoctoral student working with Donald E. Ingber, MD, PhD, founding director of the institute, ran tests showing that the model could reproduce organ-level responses to bacteria and inflammatory cytokines, as well as to silica nanoparticles. The widely cited paper was published in 2010 (Science. 2010;328[5986]:1662-8), and was followed by another study published in 2012 (Sci Transl Med. 2012;4[159]:159ra147) that used the LOC device to reproduce drug toxicity–induced pulmonary edema. “Here we were demonstrating for the first time that we could use the lung-on-chip to model human lung disease,” said Dr. Huh, who started his own lab at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in 2013.

Since then, “as a field we’ve come a long way in modeling the complexity of human lung tissues ... with more advanced devices that can be used to mimic different parts of the lung and different processes, like immune responses in asthma and viral infections,” said Dr. Huh, “and with several studies using primary human cells taken from lung disease patients.”

Among Dr. Huh’s latest devices, built with NIH funding, is an asthma-on-a-chip device. Lung cells isolated from asthma patients are grown in a microfabricated device to create multilayered airway tissue, with airspace, that contains a fully differentiated epithelium and a vascularized stroma. “We can compress the entire engineered area of asthmatic human tissue in a lateral direction to mimic bronchoconstriction that happens during an asthma attack,” he said.

A paper soon to be published will describe how “abnormal pathophysiologic compressive forces due to bronchoconstriction in asthmatic lungs can make the lungs fibrotic, and how those mechanical forces also can induce increased vascularity,” said Dr. Huh, associate professor in the university’s department of bioengineering. “The increased vascular density can also change the phenotype of blood vessels in asthmatic airways.”

Dr. Huh also has an $8.3 million contract with the government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority to study how chlorine gas damages lung tissues and identify biomarkers of chlorine gas–induced lung injury, with the goal of developing therapeutics.

Dr. Ingber and associates have developed a device modeling cystic fibrosis (CF). The chip is lined with primary human CF bronchial epithelial cells grown under an air-liquid interface and interfaced with primary lung microvascular endothelium that are exposed to fluid flow.

The chip reproduced, “with high fidelity, many of the structural, biochemical, and pathophysiological features of the human CF lung airway and its response to pathogens and circulating immune cells in vitro,” Dr. Ingber and colleagues reported (J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21:605-15).

Government investment in tissue chips

Efforts to commercialize organs-on-chip platforms and translate them for nonengineers have also picked in recent years. Several companies in the United States (including Emulate, a Wyss start-up) and in Europe now offer microengineered lung tissue models that can be used for research and drug testing. And some large pharmaceutical companies, said Dr. Tagle, have begun integrating tissue chip technology into their drug development programs.

The FDA, meanwhile, “has come to embrace the technology and see its promise,” Dr. Tagle said. An FDA pilot program announced in 2021 – called ISTAND (Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs) – allows for tissue chip data to be submitted, as standalone data, for some drug applications.

The first 5 years of the government’s Tissue Chip for Drug Screening Program focused on safety and toxicity, and it “was successful in that model organ systems were able to capture the human response that [had been missed in] animal models,” he said.

For example, when a liver-tissue model was used to test several compounds that had passed animal testing for toxicity/safety but then failed in human clinical trials – killing some of the participants – the model showed a 100% sensitivity and a 87% specificity in predicting the human response, said Dr. Tagle, who recently coauthored a review on the future of organs-on-chips (Nature Reviews I Drug Discovery. 2021;20:345-61).

The second 5 years of the program, currently winding down, have focused on efficacy – the ability of organs-on-chip models to recreate the pathophysiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, influenza, and other diseases, so that potential drugs can be assessed. In 2020, with extra support from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, NCATS funded academic labs to use organs-on-chip technology to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 and potential therapeutics.

Dr. Ingbar was one of the grantees. His team screened a number of FDA-approved drugs for potential repurposing using a bronchial-airway-on-a-chip and compared results with 2D model systems (Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:815-29). Amodiaquine inhibited infection in the 3D model and is now in phase 2 COVID trials. Several other drugs showed effectiveness in a 2D model but not in the chip.

Now, in a next phase of study at NCATS, coined Clinical Trials on a Chip, the center has awarded $35.5 million for investigators to test candidate therapies, often in parallel to ongoing clinical trials. The hope is that organs-on-chips can improve clinical trial design, from enrollment criteria and patient stratification to endpoints and the use of biomarkers. And in his lab, Dr. Huh is now engineering a shift to “organoids-on-a-chip” that combines the best features of each approach. “The idea,” he said, “is to grow organoids, and maintain the organoids in the microengineered systems where we can control their environment better ... and apply cues to allow them to develop into even more realistic tissues.”

Drs. Antony, Linkous, and Tagle reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Huh is a co-founder of Vivodyne Inc, and owns shares in Vivodyne Inc. and Emulate Inc.

Brodalumab suicide risk similar to other biologics, postmarket study finds

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved brodalumab (Siliq) in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with a boxed warning for suicidal ideation and behavior and an associated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program indicating an increased risk of suicidality.

Half a decade later, “the available worldwide data do not support the notion that brodalumab has a unique risk of increased suicides,” senior investigator John Koo, MD, and coinvestigators at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in a preproof article in JAAD International, noting that postmarketing data are “often considered a better reflection of real-world outcomes than clinical trials.”

The researchers extracted data through the end of 2021 on the number of completed suicides for brodalumab and ten other biologics approved for psoriasis from the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), an international publicly available database. The researchers included suicide data on the biologics for all indications.

The authors contacted pharmaceutical companies to determine the total number of patients prescribed each drug, securing mostly “best estimates” data on 5 of the 11 biologics available for psoriasis. The researchers then calculated the number of completed suicides per total number of prescribed patients.

For brodalumab, across 20,871 total prescriptions, there was only one verifiable suicide. It occurred in a Japanese man with terminal cancer and no nearby relatives 36 days after his first dose. The suicide rate for brodalumab was similar to that of ixekizumab, secukinumab, infliximab, and adalimumab.

“Brodalumab is a very efficacious agent and may have the fastest onset of action, yet its usage is minimal compared to the other agents because of this ‘black box’ warning ... despite the fact that it’s the least expensive of any biologic,” Dr. Koo, professor of dermatology and director of the Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. Koo, who is board-certified in both dermatology and psychiatry, said he believes the boxed warning was never warranted. All three of the verified completed suicides that occurred during clinical trials of brodalumab for psoriasis were in people who had underlying psychiatric disorders or significant stressors, such as going to jail in one case, and depression and significant isolation in another, he said.

(An analysis of psychiatric adverse events during the psoriasis clinical trials, involving more than 4,000 patients, was published online Oct. 4, 2017, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of research and teledermatology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not involved in the research, said the new data is reassuring.

“We sometimes put it into context [in thinking and counseling about risk] that in the trials for brodalumab, the number of suicide attempts [versus completed suicides] was not an outlier,” he said. “But it’s hard to know what to make of that, so this piece of knowledge that the postmarketing data show there’s no safety signal should give people a lot of reassurance.”

Dr. Han said he has used the medication, a fully human anti-interleukin 17 receptor A monoclonal antibody, in many patients who “have not done so well on other biologics and it’s been a lifesaver ... a couple who have switched over have maintained the longest level of clearance they’ve had with anything. It’s quite striking.”

The efficacy stems at least partly from its mechanism of blocking all cytokines in the IL-17 family – including those involved in the “feedback loops that perpetuate psoriasis” – rather than just one as other biologics do, Dr. Han said.

Usage of the drug has been hindered by the black box warning and REMS program, not only because of the extra steps required and hesitation potentially evoked, but because samples are not available, and because the “formulary access is not what it could have been otherwise,” he noted.

The Siliq REMS patient enrollment form requires patients to pledge awareness of the fact that suicidal thoughts and behaviors have occurred in treated patients and that they should seek medical attention if they experience suicidal thoughts or new or worsening depression, anxiety, or other mood changes. Prescribers must be certified with the program and must pledge on each enrollment form that they have counseled their patients.

The box warning states that there is no established causal association between treatment with brodalumab and increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors (SIB).

Individuals with psoriasis are an “already vulnerable population” who have been shown in reviews and meta-analyses to have a higher prevalence of depression and a higher risk of SIB than those without the disease, Dr. Koo and colleagues wrote in a narrative review published in Cutis .

Regardless of therapy, they wrote in the review, dermatologists should assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of current depression and SIB, referring patients as necessary to primary care or mental health care.

In the psoriasis trials, brodalumab treatment appeared to improve symptoms of depression and anxiety – a finding consistent with the effects reported for other biologic therapies, they wrote.

The first author on the newly published preproof is Samuel Yeroushalmi, BS, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington.

Siliq is marketed by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Koo disclosed that he is an adviser/consultant/speaker for numerous pharmaceutical companies, but not those that were involved in the development of brodalumab. Dr. Han said he has relationships with numerous companies, including those that have developed brodalumab and other biologic agents used for psoriasis. The authors declared funding sources as none.

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved brodalumab (Siliq) in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with a boxed warning for suicidal ideation and behavior and an associated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program indicating an increased risk of suicidality.

Half a decade later, “the available worldwide data do not support the notion that brodalumab has a unique risk of increased suicides,” senior investigator John Koo, MD, and coinvestigators at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in a preproof article in JAAD International, noting that postmarketing data are “often considered a better reflection of real-world outcomes than clinical trials.”

The researchers extracted data through the end of 2021 on the number of completed suicides for brodalumab and ten other biologics approved for psoriasis from the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), an international publicly available database. The researchers included suicide data on the biologics for all indications.

The authors contacted pharmaceutical companies to determine the total number of patients prescribed each drug, securing mostly “best estimates” data on 5 of the 11 biologics available for psoriasis. The researchers then calculated the number of completed suicides per total number of prescribed patients.

For brodalumab, across 20,871 total prescriptions, there was only one verifiable suicide. It occurred in a Japanese man with terminal cancer and no nearby relatives 36 days after his first dose. The suicide rate for brodalumab was similar to that of ixekizumab, secukinumab, infliximab, and adalimumab.

“Brodalumab is a very efficacious agent and may have the fastest onset of action, yet its usage is minimal compared to the other agents because of this ‘black box’ warning ... despite the fact that it’s the least expensive of any biologic,” Dr. Koo, professor of dermatology and director of the Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. Koo, who is board-certified in both dermatology and psychiatry, said he believes the boxed warning was never warranted. All three of the verified completed suicides that occurred during clinical trials of brodalumab for psoriasis were in people who had underlying psychiatric disorders or significant stressors, such as going to jail in one case, and depression and significant isolation in another, he said.

(An analysis of psychiatric adverse events during the psoriasis clinical trials, involving more than 4,000 patients, was published online Oct. 4, 2017, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of research and teledermatology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not involved in the research, said the new data is reassuring.

“We sometimes put it into context [in thinking and counseling about risk] that in the trials for brodalumab, the number of suicide attempts [versus completed suicides] was not an outlier,” he said. “But it’s hard to know what to make of that, so this piece of knowledge that the postmarketing data show there’s no safety signal should give people a lot of reassurance.”

Dr. Han said he has used the medication, a fully human anti-interleukin 17 receptor A monoclonal antibody, in many patients who “have not done so well on other biologics and it’s been a lifesaver ... a couple who have switched over have maintained the longest level of clearance they’ve had with anything. It’s quite striking.”

The efficacy stems at least partly from its mechanism of blocking all cytokines in the IL-17 family – including those involved in the “feedback loops that perpetuate psoriasis” – rather than just one as other biologics do, Dr. Han said.

Usage of the drug has been hindered by the black box warning and REMS program, not only because of the extra steps required and hesitation potentially evoked, but because samples are not available, and because the “formulary access is not what it could have been otherwise,” he noted.

The Siliq REMS patient enrollment form requires patients to pledge awareness of the fact that suicidal thoughts and behaviors have occurred in treated patients and that they should seek medical attention if they experience suicidal thoughts or new or worsening depression, anxiety, or other mood changes. Prescribers must be certified with the program and must pledge on each enrollment form that they have counseled their patients.

The box warning states that there is no established causal association between treatment with brodalumab and increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors (SIB).

Individuals with psoriasis are an “already vulnerable population” who have been shown in reviews and meta-analyses to have a higher prevalence of depression and a higher risk of SIB than those without the disease, Dr. Koo and colleagues wrote in a narrative review published in Cutis .

Regardless of therapy, they wrote in the review, dermatologists should assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of current depression and SIB, referring patients as necessary to primary care or mental health care.

In the psoriasis trials, brodalumab treatment appeared to improve symptoms of depression and anxiety – a finding consistent with the effects reported for other biologic therapies, they wrote.

The first author on the newly published preproof is Samuel Yeroushalmi, BS, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington.

Siliq is marketed by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Koo disclosed that he is an adviser/consultant/speaker for numerous pharmaceutical companies, but not those that were involved in the development of brodalumab. Dr. Han said he has relationships with numerous companies, including those that have developed brodalumab and other biologic agents used for psoriasis. The authors declared funding sources as none.

.

The Food and Drug Administration approved brodalumab (Siliq) in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with a boxed warning for suicidal ideation and behavior and an associated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program indicating an increased risk of suicidality.

Half a decade later, “the available worldwide data do not support the notion that brodalumab has a unique risk of increased suicides,” senior investigator John Koo, MD, and coinvestigators at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in a preproof article in JAAD International, noting that postmarketing data are “often considered a better reflection of real-world outcomes than clinical trials.”

The researchers extracted data through the end of 2021 on the number of completed suicides for brodalumab and ten other biologics approved for psoriasis from the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), an international publicly available database. The researchers included suicide data on the biologics for all indications.

The authors contacted pharmaceutical companies to determine the total number of patients prescribed each drug, securing mostly “best estimates” data on 5 of the 11 biologics available for psoriasis. The researchers then calculated the number of completed suicides per total number of prescribed patients.

For brodalumab, across 20,871 total prescriptions, there was only one verifiable suicide. It occurred in a Japanese man with terminal cancer and no nearby relatives 36 days after his first dose. The suicide rate for brodalumab was similar to that of ixekizumab, secukinumab, infliximab, and adalimumab.

“Brodalumab is a very efficacious agent and may have the fastest onset of action, yet its usage is minimal compared to the other agents because of this ‘black box’ warning ... despite the fact that it’s the least expensive of any biologic,” Dr. Koo, professor of dermatology and director of the Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. Koo, who is board-certified in both dermatology and psychiatry, said he believes the boxed warning was never warranted. All three of the verified completed suicides that occurred during clinical trials of brodalumab for psoriasis were in people who had underlying psychiatric disorders or significant stressors, such as going to jail in one case, and depression and significant isolation in another, he said.

(An analysis of psychiatric adverse events during the psoriasis clinical trials, involving more than 4,000 patients, was published online Oct. 4, 2017, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of research and teledermatology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not involved in the research, said the new data is reassuring.

“We sometimes put it into context [in thinking and counseling about risk] that in the trials for brodalumab, the number of suicide attempts [versus completed suicides] was not an outlier,” he said. “But it’s hard to know what to make of that, so this piece of knowledge that the postmarketing data show there’s no safety signal should give people a lot of reassurance.”

Dr. Han said he has used the medication, a fully human anti-interleukin 17 receptor A monoclonal antibody, in many patients who “have not done so well on other biologics and it’s been a lifesaver ... a couple who have switched over have maintained the longest level of clearance they’ve had with anything. It’s quite striking.”

The efficacy stems at least partly from its mechanism of blocking all cytokines in the IL-17 family – including those involved in the “feedback loops that perpetuate psoriasis” – rather than just one as other biologics do, Dr. Han said.

Usage of the drug has been hindered by the black box warning and REMS program, not only because of the extra steps required and hesitation potentially evoked, but because samples are not available, and because the “formulary access is not what it could have been otherwise,” he noted.

The Siliq REMS patient enrollment form requires patients to pledge awareness of the fact that suicidal thoughts and behaviors have occurred in treated patients and that they should seek medical attention if they experience suicidal thoughts or new or worsening depression, anxiety, or other mood changes. Prescribers must be certified with the program and must pledge on each enrollment form that they have counseled their patients.

The box warning states that there is no established causal association between treatment with brodalumab and increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors (SIB).

Individuals with psoriasis are an “already vulnerable population” who have been shown in reviews and meta-analyses to have a higher prevalence of depression and a higher risk of SIB than those without the disease, Dr. Koo and colleagues wrote in a narrative review published in Cutis .

Regardless of therapy, they wrote in the review, dermatologists should assess for any history of depression and SIB, and evaluate for signs and symptoms of current depression and SIB, referring patients as necessary to primary care or mental health care.

In the psoriasis trials, brodalumab treatment appeared to improve symptoms of depression and anxiety – a finding consistent with the effects reported for other biologic therapies, they wrote.

The first author on the newly published preproof is Samuel Yeroushalmi, BS, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington.

Siliq is marketed by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Koo disclosed that he is an adviser/consultant/speaker for numerous pharmaceutical companies, but not those that were involved in the development of brodalumab. Dr. Han said he has relationships with numerous companies, including those that have developed brodalumab and other biologic agents used for psoriasis. The authors declared funding sources as none.

Litifilimab meets primary endpoint in phase 2 lupus trial

Treatment with the humanized monoclonal antibody litifilimab for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) led to greater improvements in joint manifestations than did placebo in an international phase 2 trial that reflects keen interest in targeting type 1 interferon and the innate immune system.

Litifilimab was associated with an approximately three-joint reduction in the number of swollen and tender joints, compared with placebo, over 24 weeks in the study, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study was the first part of the LILAC trial, a two-part, phase 2 study. The second part involved cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) with or without systemic manifestations. Treatment led to improvements in skin disease, as measured by Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index–Activity (CLASI-A) scores. It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigational drug targets blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA2). The antigen is expressed solely on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), which accumulate in skin lesions and organs of patients with SLE. When the antibody binds to BDCA2, “the synthesis of a variety of cytokines is shut down – type 1 interferons, type 3 interferons, TNF [tumor necrosis factor], and [other cytokines and chemokines] made by the pDCs,” Richard A. Furie, MD, lead author of the article, said in an interview.

In a phase 1 trial involving patients with SLE and CLE, the drug’s biologic activity was shown by a dampened interferon signature in blood and modulated type 1 interferon-induced proteins in the skin, he and his coinvestigators noted.

Dr. Furie is chief of rheumatology at Northwell Health and professor of medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell and at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Uniondale, New York.

Impact on the joints

The primary analysis in the SLE trial involved 102 patients who had SLE, arthritis, and active skin disease. The patients received litifilimab 450 mg or placebo, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. The patients were required to have at least four tender joints and at least four swollen joints, and these active joints had to be those classically involved in lupus arthritis.

The mean (± standard deviation) baseline number of active joints was 19 ± 8.4 in the litifilimab group and 21.6 ± 8.5 in placebo group. From baseline to week 24, the least-squares mean (± standard deviation) change in the total number of active joints was –15.0 ± 1.2 with litifilimab and –11.6 ± 1.3 with placebo (mean difference, –3.4; 95% confidence interval, –6.7 to -0.2; P = .04).

Most of the secondary endpoints did not support the results of the primary analysis. However, improvement was seen in the SLE Responder Index (SRI-4) – a three-component global index that Dr. Furie and others developed in 2009 using data from the phase 2 SLE trial of belimumab (Benlysta).

The composite index, used in the phase 3 trial of belimumab, captures improvement in disease activity without a worsening of the condition overall or new significant disease activity in other domains. “It’s a dichotomous measure – either you’re a responder or not,” Dr. Furie said in the interview.

Response on the SRI-4 was defined as a reduction of at least 4 points from baseline in the SLEDAI-2K score (the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index), no new disease activity as measured by one score of A (severe) or more than one score of B (moderate) on the BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) index, and no increase of 0.3 points or more on the Physician’s Global Assessment.

A total of 56% of the patients in the litifilimab group showed responses on the SRI-4 at week 24, compared with 29% in the placebo group (least-squares mean difference, 26.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.5-43.2). This is “a robust response” that is much greater than the effect size seen in the phase 3 trial of belimumab or in research on anifrolumab (Saphnelo). Both of those drugs are approved for SLE, Dr. Furie said. “We’ll need to see if it’s reproduced in phase 3.”

There’s “little question that litifilimab works for the skin,” Dr. Furie noted. In the second part of the LILAC study, which focused on CLE, litifilimab demonstrated efficacy, and the SLE trial lends more support. Among several secondary endpoints evaluating skin-related disease activity, a reduction of at least 7 points from baseline in the CLASI-A score (a clinically relevant threshold) occurred in 56% of the litifilimab group and 34% of the placebo group.

The trial was conducted at 55 centers in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the United States. The SLE part of the study began as a dose-ranging study aimed at evaluating cutaneous lupus activity, but owing to “slow enrollment and to allow an assessment of the effect of litifilimab on arthritis in SLE,” the protocol and primary endpoint were amended before the trial data were unblinded to evaluate only the 450-mg dose among participants with active arthritis and skin disease (at least one active skin lesion), the investigators explained.

Background therapy for SLE was allowed if the therapy was initiated at least 12 weeks before randomization and if dose levels were stable through the trial period. Glucocorticoids had to be tapered to ≤ 10 mg/day according to a specified regimen.

Making progress for lupus

Jane E. Salmon, MD, director of the Lupus and APS Center of Excellence and codirector of the Mary Kirkland Center for Lupus Research at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, who was not involved in the research, said in an email that she is “cautiously optimistic, because in SLE, successful phase 2 trials too often are followed by unsuccessful phase 3 trials.”

Blocking the production of type 1 interferon by pDCs implicated in SLE pathogenesis has the theoretical advantage of preserving type 1 interferon critical to protection from viruses, she noted. Herpes infections were reported among patients who received litifilimab, but rates were not increased, compared with placebo.

Diversity is an important priority in further research, Dr. Salmon said.

Daniel J. Wallace, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, similarly pointed out in an editorial that accompanied the SLE phase 2 trial that while Black patients make up one-third of the U.S. population with lupus, only about 10% of study participants whose race and ethnicity was reported were Black). (Race was not reported by sites in Europe.)

The results of the LILAC trials “encourage further exploration of interventions that affect upstream lupus inflammatory pathways in the innate immune system in lupus,” Dr. Wallace wrote. He noted that lupus has “lagged behind its rheumatic cousins,” such as rheumatoid arthritis and vasculitis, in drug development.

Developing endpoints and study designs for SLE trials has been challenging, at least partly because it is a multisystem disease, Dr. Furie said. “But we’re making progress.”

Anifrolumab, a type 1 interferon receptor monoclonal antibody that was approved for SLE in July 2021, “may have a broader effect on type 1 interferons,” he noted, while litifilimab “may have a broader effect on proinflammatory cytokines, at least those expressed by pDCs.”

Biogen, the sponsor of the LILAC trial, is currently enrolling patients in phase 3 studies – TOPAZ-1 and TOPAZ-2 – to evaluate litifilimab in SLE over a 52-week period. The company also plans to start a pivotal study of the drug in CLE later this year, according to a press release.

Six coauthors are employees of Biogen; five, including Dr. Furie, reported serving as a consultant to the company; one served on a data and safety monitoring board for Biogen; and Dr. Salmon owns stock in the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with the humanized monoclonal antibody litifilimab for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) led to greater improvements in joint manifestations than did placebo in an international phase 2 trial that reflects keen interest in targeting type 1 interferon and the innate immune system.

Litifilimab was associated with an approximately three-joint reduction in the number of swollen and tender joints, compared with placebo, over 24 weeks in the study, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study was the first part of the LILAC trial, a two-part, phase 2 study. The second part involved cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) with or without systemic manifestations. Treatment led to improvements in skin disease, as measured by Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index–Activity (CLASI-A) scores. It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigational drug targets blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA2). The antigen is expressed solely on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), which accumulate in skin lesions and organs of patients with SLE. When the antibody binds to BDCA2, “the synthesis of a variety of cytokines is shut down – type 1 interferons, type 3 interferons, TNF [tumor necrosis factor], and [other cytokines and chemokines] made by the pDCs,” Richard A. Furie, MD, lead author of the article, said in an interview.

In a phase 1 trial involving patients with SLE and CLE, the drug’s biologic activity was shown by a dampened interferon signature in blood and modulated type 1 interferon-induced proteins in the skin, he and his coinvestigators noted.

Dr. Furie is chief of rheumatology at Northwell Health and professor of medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell and at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Uniondale, New York.

Impact on the joints

The primary analysis in the SLE trial involved 102 patients who had SLE, arthritis, and active skin disease. The patients received litifilimab 450 mg or placebo, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. The patients were required to have at least four tender joints and at least four swollen joints, and these active joints had to be those classically involved in lupus arthritis.

The mean (± standard deviation) baseline number of active joints was 19 ± 8.4 in the litifilimab group and 21.6 ± 8.5 in placebo group. From baseline to week 24, the least-squares mean (± standard deviation) change in the total number of active joints was –15.0 ± 1.2 with litifilimab and –11.6 ± 1.3 with placebo (mean difference, –3.4; 95% confidence interval, –6.7 to -0.2; P = .04).

Most of the secondary endpoints did not support the results of the primary analysis. However, improvement was seen in the SLE Responder Index (SRI-4) – a three-component global index that Dr. Furie and others developed in 2009 using data from the phase 2 SLE trial of belimumab (Benlysta).

The composite index, used in the phase 3 trial of belimumab, captures improvement in disease activity without a worsening of the condition overall or new significant disease activity in other domains. “It’s a dichotomous measure – either you’re a responder or not,” Dr. Furie said in the interview.

Response on the SRI-4 was defined as a reduction of at least 4 points from baseline in the SLEDAI-2K score (the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index), no new disease activity as measured by one score of A (severe) or more than one score of B (moderate) on the BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) index, and no increase of 0.3 points or more on the Physician’s Global Assessment.

A total of 56% of the patients in the litifilimab group showed responses on the SRI-4 at week 24, compared with 29% in the placebo group (least-squares mean difference, 26.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.5-43.2). This is “a robust response” that is much greater than the effect size seen in the phase 3 trial of belimumab or in research on anifrolumab (Saphnelo). Both of those drugs are approved for SLE, Dr. Furie said. “We’ll need to see if it’s reproduced in phase 3.”

There’s “little question that litifilimab works for the skin,” Dr. Furie noted. In the second part of the LILAC study, which focused on CLE, litifilimab demonstrated efficacy, and the SLE trial lends more support. Among several secondary endpoints evaluating skin-related disease activity, a reduction of at least 7 points from baseline in the CLASI-A score (a clinically relevant threshold) occurred in 56% of the litifilimab group and 34% of the placebo group.

The trial was conducted at 55 centers in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the United States. The SLE part of the study began as a dose-ranging study aimed at evaluating cutaneous lupus activity, but owing to “slow enrollment and to allow an assessment of the effect of litifilimab on arthritis in SLE,” the protocol and primary endpoint were amended before the trial data were unblinded to evaluate only the 450-mg dose among participants with active arthritis and skin disease (at least one active skin lesion), the investigators explained.

Background therapy for SLE was allowed if the therapy was initiated at least 12 weeks before randomization and if dose levels were stable through the trial period. Glucocorticoids had to be tapered to ≤ 10 mg/day according to a specified regimen.

Making progress for lupus

Jane E. Salmon, MD, director of the Lupus and APS Center of Excellence and codirector of the Mary Kirkland Center for Lupus Research at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, who was not involved in the research, said in an email that she is “cautiously optimistic, because in SLE, successful phase 2 trials too often are followed by unsuccessful phase 3 trials.”

Blocking the production of type 1 interferon by pDCs implicated in SLE pathogenesis has the theoretical advantage of preserving type 1 interferon critical to protection from viruses, she noted. Herpes infections were reported among patients who received litifilimab, but rates were not increased, compared with placebo.

Diversity is an important priority in further research, Dr. Salmon said.

Daniel J. Wallace, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, similarly pointed out in an editorial that accompanied the SLE phase 2 trial that while Black patients make up one-third of the U.S. population with lupus, only about 10% of study participants whose race and ethnicity was reported were Black). (Race was not reported by sites in Europe.)

The results of the LILAC trials “encourage further exploration of interventions that affect upstream lupus inflammatory pathways in the innate immune system in lupus,” Dr. Wallace wrote. He noted that lupus has “lagged behind its rheumatic cousins,” such as rheumatoid arthritis and vasculitis, in drug development.

Developing endpoints and study designs for SLE trials has been challenging, at least partly because it is a multisystem disease, Dr. Furie said. “But we’re making progress.”

Anifrolumab, a type 1 interferon receptor monoclonal antibody that was approved for SLE in July 2021, “may have a broader effect on type 1 interferons,” he noted, while litifilimab “may have a broader effect on proinflammatory cytokines, at least those expressed by pDCs.”

Biogen, the sponsor of the LILAC trial, is currently enrolling patients in phase 3 studies – TOPAZ-1 and TOPAZ-2 – to evaluate litifilimab in SLE over a 52-week period. The company also plans to start a pivotal study of the drug in CLE later this year, according to a press release.

Six coauthors are employees of Biogen; five, including Dr. Furie, reported serving as a consultant to the company; one served on a data and safety monitoring board for Biogen; and Dr. Salmon owns stock in the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with the humanized monoclonal antibody litifilimab for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) led to greater improvements in joint manifestations than did placebo in an international phase 2 trial that reflects keen interest in targeting type 1 interferon and the innate immune system.

Litifilimab was associated with an approximately three-joint reduction in the number of swollen and tender joints, compared with placebo, over 24 weeks in the study, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The study was the first part of the LILAC trial, a two-part, phase 2 study. The second part involved cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) with or without systemic manifestations. Treatment led to improvements in skin disease, as measured by Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index–Activity (CLASI-A) scores. It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigational drug targets blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA2). The antigen is expressed solely on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), which accumulate in skin lesions and organs of patients with SLE. When the antibody binds to BDCA2, “the synthesis of a variety of cytokines is shut down – type 1 interferons, type 3 interferons, TNF [tumor necrosis factor], and [other cytokines and chemokines] made by the pDCs,” Richard A. Furie, MD, lead author of the article, said in an interview.

In a phase 1 trial involving patients with SLE and CLE, the drug’s biologic activity was shown by a dampened interferon signature in blood and modulated type 1 interferon-induced proteins in the skin, he and his coinvestigators noted.

Dr. Furie is chief of rheumatology at Northwell Health and professor of medicine at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell and at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Uniondale, New York.

Impact on the joints

The primary analysis in the SLE trial involved 102 patients who had SLE, arthritis, and active skin disease. The patients received litifilimab 450 mg or placebo, administered subcutaneously, at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. The patients were required to have at least four tender joints and at least four swollen joints, and these active joints had to be those classically involved in lupus arthritis.

The mean (± standard deviation) baseline number of active joints was 19 ± 8.4 in the litifilimab group and 21.6 ± 8.5 in placebo group. From baseline to week 24, the least-squares mean (± standard deviation) change in the total number of active joints was –15.0 ± 1.2 with litifilimab and –11.6 ± 1.3 with placebo (mean difference, –3.4; 95% confidence interval, –6.7 to -0.2; P = .04).

Most of the secondary endpoints did not support the results of the primary analysis. However, improvement was seen in the SLE Responder Index (SRI-4) – a three-component global index that Dr. Furie and others developed in 2009 using data from the phase 2 SLE trial of belimumab (Benlysta).

The composite index, used in the phase 3 trial of belimumab, captures improvement in disease activity without a worsening of the condition overall or new significant disease activity in other domains. “It’s a dichotomous measure – either you’re a responder or not,” Dr. Furie said in the interview.

Response on the SRI-4 was defined as a reduction of at least 4 points from baseline in the SLEDAI-2K score (the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index), no new disease activity as measured by one score of A (severe) or more than one score of B (moderate) on the BILAG (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group) index, and no increase of 0.3 points or more on the Physician’s Global Assessment.