User login

Top Qualifications Hospitalist Leaders Seek in Candidates: Results from a National Survey

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

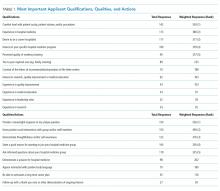

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalists Need to Rethink the Way They Evaluate Students

Delivering feedback is a fundamental skill in medicine. Feedback ensures trainees remain on track to meet expected goals and standards. At some point in our careers, all of us have been on the receiving end of feedback. Many of us have likely had the opportunity to provide feedback to students or junior residents during our training. Moving from the role of trainee to supervisor presents a unique set of challenges and responsibilities to the young hospitalist.

Despite an extensive amount published on feedback, translation from theory to practice remains challenging.1 When surveyed, medical students and residents commonly perceive they do not receive enough feedback.2 Conversely, attendees of faculty development courses frequently indicate their greatest need is learning how to give feedback more effectively.3 Why does this performance gap exist?

The Issues

Careful exploration of our current training model reveals several systemic barriers to effective feedback. For one, many faculty members who supervise trainees are not formally trained educators. As such, they may lack the proper skills set to deliver feedback.1 Additionally, lack of time is often cited in the pressure to complete both clinical and academic duties within a packed workday. If learners aren’t directly observed by their supervisors, the impact and quality of feedback substantially diminishes.4 Likewise, if feedback is not embedded in the local culture and expected by both educator and learner, it can be perceived as a burden rather than a valuable exercise.

Feedback can evoke deep, sometimes subconscious emotional responses in both supervisor and recipient. During verbal interactions with trainees, dialogue tends to assume positive or neutral tones regardless of content.5 To avoid bruising a young learner’s ego, a well-intentioned educator may talk around the actual problem, using indirect statements in an attempt to “soften the blow.” Fearing a negative evaluation, the student may support and reinforce the teacher’s avoidance, further obscuring the message being sent. This concept is known as “vanishing feedback” and is a common barrier to the delivery of effective feedback.4 Educators additionally may shy away from giving constructive feedback because they fear reprisal on teaching evaluations.

Mounting evidence shows physicians, as a whole, tend to overestimate their abilities, and many are not skilled at self-assessment.6 When physician-learners receive feedback incongruent with their own self-perceptions, it may trigger feelings of anger, sadness, guilt, or self-doubt, which may block the receipt of any useful information. The so-called “millennial generation effect,” describing current medical school graduates, may further compound this issue. Millennials are “raised with an emphasis on being special; a previous absence of a balanced focus on weakness may present a barrier to accepting the validity of negative feedback.”1,5 As such, certain learners may intentionally avoid feedback as a method of self-preservation.

A New Approach

Many of us were taught to use the “feedback sandwich,” in which two positive statements surround a single negative corrective comment. This model, however, has some notable weaknesses. Given the ratio of positive to negative statements, educators may concentrate too heavily on the positive, diluting any constructive criticism and leaving learners with a false impression. Alternatively, trainees may learn to ignore positive comments while waiting for the other shoe to drop. As such, any initial positivity may feel insincere and artificial.7

Instead, we advocate using the “reflective feedback conversation,” a model that begins with self-assessment and places the onus on learners to identify their strengths and weaknesses.7 For example, a trainee might remark, “I struggle with controlling my temper when I am stressed.” The educator might reinforce that comment by stating, “I noticed you raised your voice last week when talking with the nurse because she forgot to administer Lasix.” To conclude the conversation, the teacher and student discuss shared goal setting and mutually agree on future improvements. Notably, this model does not facilitate conversation about problems a learner fails to detect. Hence, the educator must be prepared to deliver feedback outside of the learner’s own assessment.

Here are our favorite tips and tricks for delivering effective feedback:

- Establish a positive learning climate. Educators must partner with learners to generate an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect.1,3,4,8 An example of how to ally with learners is to announce early on, “As a teacher, I really value feedback. As such, I plan on giving feedback throughout the rotation because I want you to be the best doctor you can possibly be.”

- Require reflection. Effective feedback hinges on learners’ ability to self-assess.2,5,7 One approach is starting each feedback session with a simple open-ended question, such as, “How do you think you are doing?” Alternatively, you could be more specific, such as, “How do you think you did in managing the patient’s electrolytes when he went into diabetic ketoacidosis?”

- Be prompt. Feedback should be timely.1,4,7,8 An important distinction between feedback and evaluation is that feedback is formative, enabling learners to make needed changes before the end of a course, whereas evaluation is summative and presents a distinct judgment.1,4 If feedback is withheld until the end of the rotation, learners will not have an opportunity to remediate behaviors.

- Take advantage of different formats. Try a brief, concrete suggestion on the fly. A statement that might occur on bedside rounds is, “Allow me to show you a better technique to measure the liver span.” Or use a teachable event, such as a medical error or a particularly challenging case. Pulling interns aside after they deliver sobering news is a great opportunity to provide feedback in a semiformal fashion. Finally, formal sit-down feedback should be scheduled halfway through each rotation to ensure learners are on track and to address any major issues, such as professionalism or an inadequate clinical performance.2

- Be specific. Focus on behaviors and examples rather than judgments.1,2,4,7,8 For example, we have all experienced the inattentive student. Instead of framing feedback as, “It seems like you don’t care about medicine because you weren’t paying attention on rounds,” one could say, “I noticed you were fidgeting and looking at your phone during Aaron’s presentation.” Feedback should be based on firsthand observations and should be descriptive, utilizing neutral language.

- Avoid information overload. Feedback is best consumed in small snacks rather than an all-you-can-eat buffet.1,7 Your goal should not be to completely overhaul a learner but rather to focus on a few observable, correctable behaviors.

- Be empathetic. To make negative feedback less threatening, take yourself off the pedestal. An example of this could be saying, “As a third-year medical student, I struggled to remember all the right questions to ask, so performing a thorough review of systems helped me to catch the things I would miss.”

- Confirm understanding. It is important to know the learner has heard the feedback and to conclude the session with an action plan.

Just as hospitals engage in continuous quality improvement, as professionals, we should all strive for continuous self-improvement. Giving and receiving feedback is critical to personal growth. It is our hope that by using these tips, all of us will improve, creating a new generation of providers who give effective and useful feedback.

References

- Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154-158. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1.

- Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 Pt 1):1185-1188.

- Hewson MG, Little ML. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(2):111-116.

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-781.

- Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330-1331.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102.

- Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961.

- Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):787-791.

Delivering feedback is a fundamental skill in medicine. Feedback ensures trainees remain on track to meet expected goals and standards. At some point in our careers, all of us have been on the receiving end of feedback. Many of us have likely had the opportunity to provide feedback to students or junior residents during our training. Moving from the role of trainee to supervisor presents a unique set of challenges and responsibilities to the young hospitalist.

Despite an extensive amount published on feedback, translation from theory to practice remains challenging.1 When surveyed, medical students and residents commonly perceive they do not receive enough feedback.2 Conversely, attendees of faculty development courses frequently indicate their greatest need is learning how to give feedback more effectively.3 Why does this performance gap exist?

The Issues

Careful exploration of our current training model reveals several systemic barriers to effective feedback. For one, many faculty members who supervise trainees are not formally trained educators. As such, they may lack the proper skills set to deliver feedback.1 Additionally, lack of time is often cited in the pressure to complete both clinical and academic duties within a packed workday. If learners aren’t directly observed by their supervisors, the impact and quality of feedback substantially diminishes.4 Likewise, if feedback is not embedded in the local culture and expected by both educator and learner, it can be perceived as a burden rather than a valuable exercise.

Feedback can evoke deep, sometimes subconscious emotional responses in both supervisor and recipient. During verbal interactions with trainees, dialogue tends to assume positive or neutral tones regardless of content.5 To avoid bruising a young learner’s ego, a well-intentioned educator may talk around the actual problem, using indirect statements in an attempt to “soften the blow.” Fearing a negative evaluation, the student may support and reinforce the teacher’s avoidance, further obscuring the message being sent. This concept is known as “vanishing feedback” and is a common barrier to the delivery of effective feedback.4 Educators additionally may shy away from giving constructive feedback because they fear reprisal on teaching evaluations.

Mounting evidence shows physicians, as a whole, tend to overestimate their abilities, and many are not skilled at self-assessment.6 When physician-learners receive feedback incongruent with their own self-perceptions, it may trigger feelings of anger, sadness, guilt, or self-doubt, which may block the receipt of any useful information. The so-called “millennial generation effect,” describing current medical school graduates, may further compound this issue. Millennials are “raised with an emphasis on being special; a previous absence of a balanced focus on weakness may present a barrier to accepting the validity of negative feedback.”1,5 As such, certain learners may intentionally avoid feedback as a method of self-preservation.

A New Approach

Many of us were taught to use the “feedback sandwich,” in which two positive statements surround a single negative corrective comment. This model, however, has some notable weaknesses. Given the ratio of positive to negative statements, educators may concentrate too heavily on the positive, diluting any constructive criticism and leaving learners with a false impression. Alternatively, trainees may learn to ignore positive comments while waiting for the other shoe to drop. As such, any initial positivity may feel insincere and artificial.7

Instead, we advocate using the “reflective feedback conversation,” a model that begins with self-assessment and places the onus on learners to identify their strengths and weaknesses.7 For example, a trainee might remark, “I struggle with controlling my temper when I am stressed.” The educator might reinforce that comment by stating, “I noticed you raised your voice last week when talking with the nurse because she forgot to administer Lasix.” To conclude the conversation, the teacher and student discuss shared goal setting and mutually agree on future improvements. Notably, this model does not facilitate conversation about problems a learner fails to detect. Hence, the educator must be prepared to deliver feedback outside of the learner’s own assessment.

Here are our favorite tips and tricks for delivering effective feedback:

- Establish a positive learning climate. Educators must partner with learners to generate an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect.1,3,4,8 An example of how to ally with learners is to announce early on, “As a teacher, I really value feedback. As such, I plan on giving feedback throughout the rotation because I want you to be the best doctor you can possibly be.”

- Require reflection. Effective feedback hinges on learners’ ability to self-assess.2,5,7 One approach is starting each feedback session with a simple open-ended question, such as, “How do you think you are doing?” Alternatively, you could be more specific, such as, “How do you think you did in managing the patient’s electrolytes when he went into diabetic ketoacidosis?”

- Be prompt. Feedback should be timely.1,4,7,8 An important distinction between feedback and evaluation is that feedback is formative, enabling learners to make needed changes before the end of a course, whereas evaluation is summative and presents a distinct judgment.1,4 If feedback is withheld until the end of the rotation, learners will not have an opportunity to remediate behaviors.

- Take advantage of different formats. Try a brief, concrete suggestion on the fly. A statement that might occur on bedside rounds is, “Allow me to show you a better technique to measure the liver span.” Or use a teachable event, such as a medical error or a particularly challenging case. Pulling interns aside after they deliver sobering news is a great opportunity to provide feedback in a semiformal fashion. Finally, formal sit-down feedback should be scheduled halfway through each rotation to ensure learners are on track and to address any major issues, such as professionalism or an inadequate clinical performance.2

- Be specific. Focus on behaviors and examples rather than judgments.1,2,4,7,8 For example, we have all experienced the inattentive student. Instead of framing feedback as, “It seems like you don’t care about medicine because you weren’t paying attention on rounds,” one could say, “I noticed you were fidgeting and looking at your phone during Aaron’s presentation.” Feedback should be based on firsthand observations and should be descriptive, utilizing neutral language.

- Avoid information overload. Feedback is best consumed in small snacks rather than an all-you-can-eat buffet.1,7 Your goal should not be to completely overhaul a learner but rather to focus on a few observable, correctable behaviors.

- Be empathetic. To make negative feedback less threatening, take yourself off the pedestal. An example of this could be saying, “As a third-year medical student, I struggled to remember all the right questions to ask, so performing a thorough review of systems helped me to catch the things I would miss.”

- Confirm understanding. It is important to know the learner has heard the feedback and to conclude the session with an action plan.

Just as hospitals engage in continuous quality improvement, as professionals, we should all strive for continuous self-improvement. Giving and receiving feedback is critical to personal growth. It is our hope that by using these tips, all of us will improve, creating a new generation of providers who give effective and useful feedback.

References

- Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154-158. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1.

- Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 Pt 1):1185-1188.

- Hewson MG, Little ML. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(2):111-116.

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-781.

- Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330-1331.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102.

- Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961.

- Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):787-791.

Delivering feedback is a fundamental skill in medicine. Feedback ensures trainees remain on track to meet expected goals and standards. At some point in our careers, all of us have been on the receiving end of feedback. Many of us have likely had the opportunity to provide feedback to students or junior residents during our training. Moving from the role of trainee to supervisor presents a unique set of challenges and responsibilities to the young hospitalist.

Despite an extensive amount published on feedback, translation from theory to practice remains challenging.1 When surveyed, medical students and residents commonly perceive they do not receive enough feedback.2 Conversely, attendees of faculty development courses frequently indicate their greatest need is learning how to give feedback more effectively.3 Why does this performance gap exist?

The Issues

Careful exploration of our current training model reveals several systemic barriers to effective feedback. For one, many faculty members who supervise trainees are not formally trained educators. As such, they may lack the proper skills set to deliver feedback.1 Additionally, lack of time is often cited in the pressure to complete both clinical and academic duties within a packed workday. If learners aren’t directly observed by their supervisors, the impact and quality of feedback substantially diminishes.4 Likewise, if feedback is not embedded in the local culture and expected by both educator and learner, it can be perceived as a burden rather than a valuable exercise.

Feedback can evoke deep, sometimes subconscious emotional responses in both supervisor and recipient. During verbal interactions with trainees, dialogue tends to assume positive or neutral tones regardless of content.5 To avoid bruising a young learner’s ego, a well-intentioned educator may talk around the actual problem, using indirect statements in an attempt to “soften the blow.” Fearing a negative evaluation, the student may support and reinforce the teacher’s avoidance, further obscuring the message being sent. This concept is known as “vanishing feedback” and is a common barrier to the delivery of effective feedback.4 Educators additionally may shy away from giving constructive feedback because they fear reprisal on teaching evaluations.

Mounting evidence shows physicians, as a whole, tend to overestimate their abilities, and many are not skilled at self-assessment.6 When physician-learners receive feedback incongruent with their own self-perceptions, it may trigger feelings of anger, sadness, guilt, or self-doubt, which may block the receipt of any useful information. The so-called “millennial generation effect,” describing current medical school graduates, may further compound this issue. Millennials are “raised with an emphasis on being special; a previous absence of a balanced focus on weakness may present a barrier to accepting the validity of negative feedback.”1,5 As such, certain learners may intentionally avoid feedback as a method of self-preservation.

A New Approach

Many of us were taught to use the “feedback sandwich,” in which two positive statements surround a single negative corrective comment. This model, however, has some notable weaknesses. Given the ratio of positive to negative statements, educators may concentrate too heavily on the positive, diluting any constructive criticism and leaving learners with a false impression. Alternatively, trainees may learn to ignore positive comments while waiting for the other shoe to drop. As such, any initial positivity may feel insincere and artificial.7

Instead, we advocate using the “reflective feedback conversation,” a model that begins with self-assessment and places the onus on learners to identify their strengths and weaknesses.7 For example, a trainee might remark, “I struggle with controlling my temper when I am stressed.” The educator might reinforce that comment by stating, “I noticed you raised your voice last week when talking with the nurse because she forgot to administer Lasix.” To conclude the conversation, the teacher and student discuss shared goal setting and mutually agree on future improvements. Notably, this model does not facilitate conversation about problems a learner fails to detect. Hence, the educator must be prepared to deliver feedback outside of the learner’s own assessment.

Here are our favorite tips and tricks for delivering effective feedback:

- Establish a positive learning climate. Educators must partner with learners to generate an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect.1,3,4,8 An example of how to ally with learners is to announce early on, “As a teacher, I really value feedback. As such, I plan on giving feedback throughout the rotation because I want you to be the best doctor you can possibly be.”

- Require reflection. Effective feedback hinges on learners’ ability to self-assess.2,5,7 One approach is starting each feedback session with a simple open-ended question, such as, “How do you think you are doing?” Alternatively, you could be more specific, such as, “How do you think you did in managing the patient’s electrolytes when he went into diabetic ketoacidosis?”

- Be prompt. Feedback should be timely.1,4,7,8 An important distinction between feedback and evaluation is that feedback is formative, enabling learners to make needed changes before the end of a course, whereas evaluation is summative and presents a distinct judgment.1,4 If feedback is withheld until the end of the rotation, learners will not have an opportunity to remediate behaviors.

- Take advantage of different formats. Try a brief, concrete suggestion on the fly. A statement that might occur on bedside rounds is, “Allow me to show you a better technique to measure the liver span.” Or use a teachable event, such as a medical error or a particularly challenging case. Pulling interns aside after they deliver sobering news is a great opportunity to provide feedback in a semiformal fashion. Finally, formal sit-down feedback should be scheduled halfway through each rotation to ensure learners are on track and to address any major issues, such as professionalism or an inadequate clinical performance.2

- Be specific. Focus on behaviors and examples rather than judgments.1,2,4,7,8 For example, we have all experienced the inattentive student. Instead of framing feedback as, “It seems like you don’t care about medicine because you weren’t paying attention on rounds,” one could say, “I noticed you were fidgeting and looking at your phone during Aaron’s presentation.” Feedback should be based on firsthand observations and should be descriptive, utilizing neutral language.

- Avoid information overload. Feedback is best consumed in small snacks rather than an all-you-can-eat buffet.1,7 Your goal should not be to completely overhaul a learner but rather to focus on a few observable, correctable behaviors.

- Be empathetic. To make negative feedback less threatening, take yourself off the pedestal. An example of this could be saying, “As a third-year medical student, I struggled to remember all the right questions to ask, so performing a thorough review of systems helped me to catch the things I would miss.”

- Confirm understanding. It is important to know the learner has heard the feedback and to conclude the session with an action plan.

Just as hospitals engage in continuous quality improvement, as professionals, we should all strive for continuous self-improvement. Giving and receiving feedback is critical to personal growth. It is our hope that by using these tips, all of us will improve, creating a new generation of providers who give effective and useful feedback.

References

- Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154-158. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1.

- Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12 Pt 1):1185-1188.

- Hewson MG, Little ML. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(2):111-116.

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-781.

- Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330-1331.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102.

- Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961.

- Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):787-791.

Tips for Hospitalists to Understand, Promote Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction—“the patient experience”—is given great weight by hospitals and the public alike. Physicians have always aspired to take excellent care of patients. What has changed is that assessments of the patient experience are now being used to measure and report the quality of our care. Although there are many venues for patients to share their opinions, including reviews and online ratings, only the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey is standardized and allows for comparisons nationwide.

Given that HCAHPS is the standard by which hospitals, health systems, and individual hospitalists are judged, it is vital for us to understand the core drivers of measured patient experience—especially the factors within our control. Armed with this knowledge, we can more effectively promote a positive experience within our daily patient care.

Understanding HCAHPS

HCAHPS (H-caps) is a national, standardized, and publicly reported survey of patients’ experiences in the hospital. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed and piloted the survey in 2002 and launched it in October 2006, with results first published in March 2008 on the Hospital Compare website.

The survey must be administered to a random sample of hospital inpatients 48 hours to six weeks after discharge, and it is offered in multiple languages, either by phone or mail. Twenty-one core questions cover seven composites (communication with doctors, communication with nurses, responsiveness of hospital staff, pain control, communication about new medications, discharge information and planning, and cleanliness/quietness) and two global items (patients’ overall rating of the hospital and likelihood to recommend it to family and friends). There are several additional questions adjusting for patient mix between hospitals, as well as any supplementary questions desired by individual hospitals.1

With the exception of the two global items, all core HCAHPS questions ask “how often” a patient experienced a particular aspect of hospital care. Possible answers are “Always,” “Usually,” “Sometimes,” or “Never”; credit is given to the hospital only for a “top box” score of “Always.” The three questions that are most applicable to hospitalists make up the “communication with doctors” composite; they focus on the quality of physician-patient communication:

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?

Importance to Hospitalists

A tremendous amount is tied to HCAHPS scores: hospital reimbursement from CMS (through value-based purchasing), hospital rating and “brand,” patients’ choice of hospital, and, in some cases, hospitalist performance bonuses. Hospitals and health systems therefore emphasize HCAHPS heavily. This emphasis has sparked some controversy, particularly surrounding the risk that inappropriate medical decisions (e.g. prescribing antimicrobials or pain medications when not indicated) will be made in order to generate higher patient satisfaction scores. Given the evidence that physicians’ biomedical skill and interpersonal qualities are equally important in determining patient satisfaction, however, we can remain optimistic that time spent explaining the rationale for appropriate medical care is highly valued by patients.2,3

The more satisfied patients are with the care they receive, the more likely they are to continue to seek care from the same provider, hospital, and/or clinic. Improved continuity can help increase adherence, improve patient safety, and decrease healthcare costs. Positive healthcare experiences are also correlated with improved patient compliance with treatment regimens and medical advice, which will lead to better outcomes.

We must also recognize that both the patient experience and physician-patient communication impact clinical care. First, a positive patient experience is linked to higher continuity of care.4 The more satisfied patients are with the care they receive, the more likely they are to continue to seek care from the same provider, hospital, and/or clinic. Improved continuity can help increase adherence, improve patient safety, and decrease healthcare costs. Positive healthcare experiences are also correlated with improved patient compliance with treatment regimens and medical advice, which will lead to better outcomes.5,6

Additionally, higher patient satisfaction is associated with decreased readmission rates. An analysis of more than 2,500 hospitals demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between lower 30-day risk-standardized readmission rates, higher patient satisfaction with discharge planning, and higher overall patient satisfaction with care.7

Furthermore, high quality physician-patient communication has been linked to improved health outcomes. A meta-analysis of 21 separate studies evaluating the effect of communication on health outcomes demonstrated a direct positive correlation with five outcome measures—emotional health, symptom resolution, functional status, physiologic measures (blood pressure and glycemic control), and pain control.8

Finally, higher patient satisfaction and improved physician-patient communication are inversely correlated with medical malpractice risk.9,10

Current data regarding the effect of patient satisfaction on mortality and healthcare utilization/expenditures are conflicting. Jaipaul and Rosenthal found that higher patient satisfaction was associated with decreased mortality.11 Conversely, Fenton and colleagues found an association between high patient satisfaction and both increased mortality and higher healthcare utilization/costs.12 More long-term data will be helpful in clarifying this question.

For hospitalists, the importance of patient satisfaction might reach beyond its clinical impact. Both new residency graduates and more seasoned hospitalists will find that their personal HCAHPS scores can either be highlighted as a strength or work to their detriment when they apply for new positions. Many physicians find that they are asked about their patient satisfaction scores during job interviews. Being knowledgeable about both the patient experience and whether your patients perceive you positively can be an asset.

What Influences Patient Satisfaction, and How Do We Promote It?

Studies show that excellent medical care and strong interpersonal qualities are equally important influences on patients’ satisfaction with physicians.2,3 Having a high quality interaction with their doctor—during which patients feel that they are valued and listened to, that their opinions are taken into consideration, and that they have received a clear explanation—is more important to patients than having a lengthy visit with their provider.13

Consequently, interventions that focus on improving the humanistic aspects of our care and enhancing the quality of our communication will be the most effective strategies for improving patient satisfaction. Remembering to practice empathy for our patients in the midst of our very busy and stressful workdays is an excellent start. We can also utilize the following proven practices for enhancing physician-patient communication:

- Sit down at the bedside;

- Use patient-centered communication techniques, such as asking open-ended questions, using the teach-back method and shared decision-making, and avoiding jargon;

- Clearly outline the plan for the day and explain how it fits into the overall goal of the hospitalization;

- Invite questions; and

- Utilize patient whiteboards.

In addition, demonstrating to patients that we collaborate and effectively communicate with the rest of the healthcare team can also enhance their experience.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, patient satisfaction should not be regarded as an extraneous amenity for our patients or as a necessary evil to placate hospital administrators. Instead, improving our patients’ hospital experience can help improve their overall care and health.

Strong physician-patient partnerships and high patient satisfaction increase continuity of care and adherence to treatment, while also resulting in better health outcomes and decreased hospital readmission rates. Furthermore, if hospitalists emphasize a positive patient experience by fostering effective communication and positive relationships, they can also decrease their malpractice risk.

We must therefore find ways to foster patient satisfaction while maintaining safe, effective, quality-driven patient care. Emphasizing humanism and communication, while providing safe and high quality care, is the optimal way to promote patient satisfaction. In this way, we can improve not only the patient experience but also health outcomes.

Dr. Bergin is an academic hospitalist for the internal medicine residency program at Banner-University Medical Center Phoenix in Arizona and a clinical assistant professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. Dr. O’Malley is the internal medicine residency program director at Banner and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. She currently serves as SHM’s representative on the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Education Redesign Advisory Board. Dr. Donahue is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCAHPS Fact Sheet (CAHPS Hospital Survey) – August 2013. Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2015.

- Matthews DA, Sledge WH, Lieberman PB. Evaluation of intern performance by medical inpatients. Am J Med. 1987;83(5):938-944.

- Matthews DA, Feinstein AR. A new instrument for patients’ ratings of physician performance in the hospital setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):14-22.

- Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Change H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching doctors: Predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):130-136.

- DeMatteo MR. Enhancing patient adherence to medical recommendations. JAMA. 1994:271(1):79, 83.

- Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(3):213-220.

- Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

- Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423-1433.

- Tan SY. Issues in medical malpractice IX. Doctors most prone to lawsuits. Hawaii Med J. 2007;66(3):78-79.

- Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice: Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(12):1365-1370.

- Jaipaul CK, Rosenthal GE. Do hospitals with lower mortality have higher patient satisfaction? A regional analysis of patients with medical diagnoses. Am J Med Qual. 2003;18(2):59-65.

- Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405-411.

- Blanden AR, Rohr RE. Cognitive interview techniques reveal specific behaviors and issues that could affect patient satisfaction relative to hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):E1-6.

Patient satisfaction—“the patient experience”—is given great weight by hospitals and the public alike. Physicians have always aspired to take excellent care of patients. What has changed is that assessments of the patient experience are now being used to measure and report the quality of our care. Although there are many venues for patients to share their opinions, including reviews and online ratings, only the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey is standardized and allows for comparisons nationwide.

Given that HCAHPS is the standard by which hospitals, health systems, and individual hospitalists are judged, it is vital for us to understand the core drivers of measured patient experience—especially the factors within our control. Armed with this knowledge, we can more effectively promote a positive experience within our daily patient care.

Understanding HCAHPS

HCAHPS (H-caps) is a national, standardized, and publicly reported survey of patients’ experiences in the hospital. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed and piloted the survey in 2002 and launched it in October 2006, with results first published in March 2008 on the Hospital Compare website.

The survey must be administered to a random sample of hospital inpatients 48 hours to six weeks after discharge, and it is offered in multiple languages, either by phone or mail. Twenty-one core questions cover seven composites (communication with doctors, communication with nurses, responsiveness of hospital staff, pain control, communication about new medications, discharge information and planning, and cleanliness/quietness) and two global items (patients’ overall rating of the hospital and likelihood to recommend it to family and friends). There are several additional questions adjusting for patient mix between hospitals, as well as any supplementary questions desired by individual hospitals.1

With the exception of the two global items, all core HCAHPS questions ask “how often” a patient experienced a particular aspect of hospital care. Possible answers are “Always,” “Usually,” “Sometimes,” or “Never”; credit is given to the hospital only for a “top box” score of “Always.” The three questions that are most applicable to hospitalists make up the “communication with doctors” composite; they focus on the quality of physician-patient communication:

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?

Importance to Hospitalists

A tremendous amount is tied to HCAHPS scores: hospital reimbursement from CMS (through value-based purchasing), hospital rating and “brand,” patients’ choice of hospital, and, in some cases, hospitalist performance bonuses. Hospitals and health systems therefore emphasize HCAHPS heavily. This emphasis has sparked some controversy, particularly surrounding the risk that inappropriate medical decisions (e.g. prescribing antimicrobials or pain medications when not indicated) will be made in order to generate higher patient satisfaction scores. Given the evidence that physicians’ biomedical skill and interpersonal qualities are equally important in determining patient satisfaction, however, we can remain optimistic that time spent explaining the rationale for appropriate medical care is highly valued by patients.2,3

The more satisfied patients are with the care they receive, the more likely they are to continue to seek care from the same provider, hospital, and/or clinic. Improved continuity can help increase adherence, improve patient safety, and decrease healthcare costs. Positive healthcare experiences are also correlated with improved patient compliance with treatment regimens and medical advice, which will lead to better outcomes.