User login

Leadership & Professional Development: Ultra-Brief Teaching; It’s Now or Never

“The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.“

—Thomas Jefferson

Attendings, residents, and medical students identify education as a top purpose of team rounds.1 Learners report being dissatisfied with teaching on rounds most of the time.2 Time with learners is a finite resource that has become even more precious with increasing clinical demands and work hour restrictions.3 Attendings report insufficient time to teach on rounds, and often neglect teaching because of time constraints.4 What can we do to in the face of this conflict between time and teaching?

One approach to this problem is what we call “ultra-brief, deliberate teaching sessions.” These sessions, or UBDTs, led by clinicians, create dedicated time for teaching on service. UBDTs ideally occur before team rounds because, in our experience, this is when the team is most unified and focused. Our sessions are time-limited (5 minutes or less) and designed so they are applicable to clinical scenarios the team is actively facing. Other learners can also lead these sessions with faculty coaching. Sessions of germane size and scope include: (1) Focus on a single clinical question from the previous day; (2) Discuss Choosing Wisely® recommendations from a single specialty; (3) Provide a concise cognitive framework for a diagnostic or treatment dilemma (eg, draw a simple algorithm to evaluate causes of hyponatremia); (4) Review one image or electrocardiogram; (5) Present one case-based multiple-choice question; (6) Prime the team with a structured approach to a difficult conversation (eg, opioid discussions, goals of care).

As an example, if our team orders intravenous antihypertensives overnight, a UBDT session on asymptomatic hypertension would occur. The first minute may involve a discussion on the definition of hypertensive emergency versus asymptomatic hypertension. Next, we spend one minute asking learners the common causes of inpatient hypertension (eg, missed medications, pain, anxiety, withdrawal), highlighting that this warrants a bedside assessment. For two minutes, we next discuss the management options for asymptomatic hypertension with an emphasis on the avoidance of intravenous antihypertensives, tying this back to our current patient. Questions are welcomed, and a one-page summary of the major points and references is distributed during or after the talk. A repository of common topics and summaries may be a useful faculty development resource to be shared.

We have found UBDTs to be easy to implement for a variety of clinician educators. Because they are so brief and focused, they are also fun to create and share among teaching faculty. Importantly, these sessions should not delay clinical work. To ensure the avoidance of this trap, don’t select a topic that is too large or involves complex clinical reasoning, exceeds 5 minutes, or lead a UBDT session in a distracting environment or without preparation.

While we have not found a way to slow down time, UBDT sessions prior to the start of rounds can prioritize teaching, ensure the delivery of important content, and engage learners without significantly delaying clinical work. We invite you to try one!

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Ragsdale, MD, MS for his leadership and support for UBDTs.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Hulland O, Farnan J, Rabinowitz R, et al. What’s the Purpose of Rounds? A Qualitative Study Examining the Perception of Faculty and Students. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(11):892-897. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2835

2. Merritt FW, Noble MN, Prochazka AV, et al. Attending rounds: What do the all-star teachers do? Med Teach. 2017;39(1):100-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1248914

3. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041.

4. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of Bedside Teaching by an Academic Hospitalist Group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5);304-307. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.540

“The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.“

—Thomas Jefferson

Attendings, residents, and medical students identify education as a top purpose of team rounds.1 Learners report being dissatisfied with teaching on rounds most of the time.2 Time with learners is a finite resource that has become even more precious with increasing clinical demands and work hour restrictions.3 Attendings report insufficient time to teach on rounds, and often neglect teaching because of time constraints.4 What can we do to in the face of this conflict between time and teaching?

One approach to this problem is what we call “ultra-brief, deliberate teaching sessions.” These sessions, or UBDTs, led by clinicians, create dedicated time for teaching on service. UBDTs ideally occur before team rounds because, in our experience, this is when the team is most unified and focused. Our sessions are time-limited (5 minutes or less) and designed so they are applicable to clinical scenarios the team is actively facing. Other learners can also lead these sessions with faculty coaching. Sessions of germane size and scope include: (1) Focus on a single clinical question from the previous day; (2) Discuss Choosing Wisely® recommendations from a single specialty; (3) Provide a concise cognitive framework for a diagnostic or treatment dilemma (eg, draw a simple algorithm to evaluate causes of hyponatremia); (4) Review one image or electrocardiogram; (5) Present one case-based multiple-choice question; (6) Prime the team with a structured approach to a difficult conversation (eg, opioid discussions, goals of care).

As an example, if our team orders intravenous antihypertensives overnight, a UBDT session on asymptomatic hypertension would occur. The first minute may involve a discussion on the definition of hypertensive emergency versus asymptomatic hypertension. Next, we spend one minute asking learners the common causes of inpatient hypertension (eg, missed medications, pain, anxiety, withdrawal), highlighting that this warrants a bedside assessment. For two minutes, we next discuss the management options for asymptomatic hypertension with an emphasis on the avoidance of intravenous antihypertensives, tying this back to our current patient. Questions are welcomed, and a one-page summary of the major points and references is distributed during or after the talk. A repository of common topics and summaries may be a useful faculty development resource to be shared.

We have found UBDTs to be easy to implement for a variety of clinician educators. Because they are so brief and focused, they are also fun to create and share among teaching faculty. Importantly, these sessions should not delay clinical work. To ensure the avoidance of this trap, don’t select a topic that is too large or involves complex clinical reasoning, exceeds 5 minutes, or lead a UBDT session in a distracting environment or without preparation.

While we have not found a way to slow down time, UBDT sessions prior to the start of rounds can prioritize teaching, ensure the delivery of important content, and engage learners without significantly delaying clinical work. We invite you to try one!

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Ragsdale, MD, MS for his leadership and support for UBDTs.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

“The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.“

—Thomas Jefferson

Attendings, residents, and medical students identify education as a top purpose of team rounds.1 Learners report being dissatisfied with teaching on rounds most of the time.2 Time with learners is a finite resource that has become even more precious with increasing clinical demands and work hour restrictions.3 Attendings report insufficient time to teach on rounds, and often neglect teaching because of time constraints.4 What can we do to in the face of this conflict between time and teaching?

One approach to this problem is what we call “ultra-brief, deliberate teaching sessions.” These sessions, or UBDTs, led by clinicians, create dedicated time for teaching on service. UBDTs ideally occur before team rounds because, in our experience, this is when the team is most unified and focused. Our sessions are time-limited (5 minutes or less) and designed so they are applicable to clinical scenarios the team is actively facing. Other learners can also lead these sessions with faculty coaching. Sessions of germane size and scope include: (1) Focus on a single clinical question from the previous day; (2) Discuss Choosing Wisely® recommendations from a single specialty; (3) Provide a concise cognitive framework for a diagnostic or treatment dilemma (eg, draw a simple algorithm to evaluate causes of hyponatremia); (4) Review one image or electrocardiogram; (5) Present one case-based multiple-choice question; (6) Prime the team with a structured approach to a difficult conversation (eg, opioid discussions, goals of care).

As an example, if our team orders intravenous antihypertensives overnight, a UBDT session on asymptomatic hypertension would occur. The first minute may involve a discussion on the definition of hypertensive emergency versus asymptomatic hypertension. Next, we spend one minute asking learners the common causes of inpatient hypertension (eg, missed medications, pain, anxiety, withdrawal), highlighting that this warrants a bedside assessment. For two minutes, we next discuss the management options for asymptomatic hypertension with an emphasis on the avoidance of intravenous antihypertensives, tying this back to our current patient. Questions are welcomed, and a one-page summary of the major points and references is distributed during or after the talk. A repository of common topics and summaries may be a useful faculty development resource to be shared.

We have found UBDTs to be easy to implement for a variety of clinician educators. Because they are so brief and focused, they are also fun to create and share among teaching faculty. Importantly, these sessions should not delay clinical work. To ensure the avoidance of this trap, don’t select a topic that is too large or involves complex clinical reasoning, exceeds 5 minutes, or lead a UBDT session in a distracting environment or without preparation.

While we have not found a way to slow down time, UBDT sessions prior to the start of rounds can prioritize teaching, ensure the delivery of important content, and engage learners without significantly delaying clinical work. We invite you to try one!

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Ragsdale, MD, MS for his leadership and support for UBDTs.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Hulland O, Farnan J, Rabinowitz R, et al. What’s the Purpose of Rounds? A Qualitative Study Examining the Perception of Faculty and Students. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(11):892-897. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2835

2. Merritt FW, Noble MN, Prochazka AV, et al. Attending rounds: What do the all-star teachers do? Med Teach. 2017;39(1):100-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1248914

3. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041.

4. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of Bedside Teaching by an Academic Hospitalist Group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5);304-307. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.540

1. Hulland O, Farnan J, Rabinowitz R, et al. What’s the Purpose of Rounds? A Qualitative Study Examining the Perception of Faculty and Students. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(11):892-897. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2835

2. Merritt FW, Noble MN, Prochazka AV, et al. Attending rounds: What do the all-star teachers do? Med Teach. 2017;39(1):100-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1248914

3. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041.

4. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of Bedside Teaching by an Academic Hospitalist Group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5);304-307. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.540

©2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Not Salty Enough

We commend Gottenborg and Pierce on their well-written summary of the 2013 National Institutes of Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on int

The recommendations for hypotonic solutions were largely developed from theoretical research in the 1950s before the first description of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.5 Hospitalized patients are at significant risk for nonosmotic stimuli for antidiuretic hormone secretion, and hypotonic fluids increase the risk of hyponatremia, which can have catastrophic complications. We believe the pediatric evidence should be extrapolated and included with the supporting (albeit limited) adult evidence, and that when indicated, isotonic fluids should be the maintenance fluid for most hospitalized adults.3-4,6

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Gottenborg E, Pierce R. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):172-173. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3178

2. National Clinical Guideline Centre. Intravenous Fluid Therapy: Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital, London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2013 Dec. Updated May 3, 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/g174. Accessed April 6, 2019.

3. Feld LG, Neuspiel DR, Foster BA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: maintenance intravenous fluids in children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):170-171. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3083.

4. Neilson J, O’Neill F, Dawoud D, Crean P, Guideline Development G. Intravenous fluids in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h6388. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6388

5. Talbot NB, Crawford DJ, Butler AM. Medical progress; homeostatic limits to safe parenteral fluid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:1100-1108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195306252482605

6. Okada M, Egi M, Yokota Y, et al. Comparison of the incidences of hyponatremia in adult postoperative critically ill patients receiving intravenous maintenance fluids with 140 mmol/L or 35 mmol/L of sodium: retrospective before/after observational study. J Anesth. 2017;31(5):657-663 PubMed

We commend Gottenborg and Pierce on their well-written summary of the 2013 National Institutes of Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on int

The recommendations for hypotonic solutions were largely developed from theoretical research in the 1950s before the first description of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.5 Hospitalized patients are at significant risk for nonosmotic stimuli for antidiuretic hormone secretion, and hypotonic fluids increase the risk of hyponatremia, which can have catastrophic complications. We believe the pediatric evidence should be extrapolated and included with the supporting (albeit limited) adult evidence, and that when indicated, isotonic fluids should be the maintenance fluid for most hospitalized adults.3-4,6

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

We commend Gottenborg and Pierce on their well-written summary of the 2013 National Institutes of Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on int

The recommendations for hypotonic solutions were largely developed from theoretical research in the 1950s before the first description of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.5 Hospitalized patients are at significant risk for nonosmotic stimuli for antidiuretic hormone secretion, and hypotonic fluids increase the risk of hyponatremia, which can have catastrophic complications. We believe the pediatric evidence should be extrapolated and included with the supporting (albeit limited) adult evidence, and that when indicated, isotonic fluids should be the maintenance fluid for most hospitalized adults.3-4,6

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Gottenborg E, Pierce R. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):172-173. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3178

2. National Clinical Guideline Centre. Intravenous Fluid Therapy: Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital, London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2013 Dec. Updated May 3, 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/g174. Accessed April 6, 2019.

3. Feld LG, Neuspiel DR, Foster BA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: maintenance intravenous fluids in children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):170-171. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3083.

4. Neilson J, O’Neill F, Dawoud D, Crean P, Guideline Development G. Intravenous fluids in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h6388. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6388

5. Talbot NB, Crawford DJ, Butler AM. Medical progress; homeostatic limits to safe parenteral fluid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:1100-1108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195306252482605

6. Okada M, Egi M, Yokota Y, et al. Comparison of the incidences of hyponatremia in adult postoperative critically ill patients receiving intravenous maintenance fluids with 140 mmol/L or 35 mmol/L of sodium: retrospective before/after observational study. J Anesth. 2017;31(5):657-663 PubMed

1. Gottenborg E, Pierce R. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):172-173. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3178

2. National Clinical Guideline Centre. Intravenous Fluid Therapy: Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital, London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2013 Dec. Updated May 3, 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/g174. Accessed April 6, 2019.

3. Feld LG, Neuspiel DR, Foster BA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: maintenance intravenous fluids in children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):170-171. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3083.

4. Neilson J, O’Neill F, Dawoud D, Crean P, Guideline Development G. Intravenous fluids in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h6388. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6388

5. Talbot NB, Crawford DJ, Butler AM. Medical progress; homeostatic limits to safe parenteral fluid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:1100-1108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195306252482605

6. Okada M, Egi M, Yokota Y, et al. Comparison of the incidences of hyponatremia in adult postoperative critically ill patients receiving intravenous maintenance fluids with 140 mmol/L or 35 mmol/L of sodium: retrospective before/after observational study. J Anesth. 2017;31(5):657-663 PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Top Qualifications Hospitalist Leaders Seek in Candidates: Results from a National Survey

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

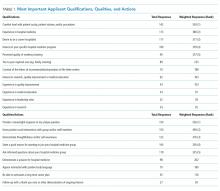

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine