User login

Our EHRs have a drug problem

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

The 21st Century Cures Act: Tearing down fortresses to put patients first

"A fortress not only protects those inside of it, but it also enslaves them to work.”

– Anthony T. Hincks

As physicians, we spend a great deal of time intending to do our best for the people we serve. We believe fundamentally in the idea that our patients come first, and we toil daily to exercise that belief. We also want our patients to feel they are driving their care as active participants along the journey. Yet time and time again, despite our greatest attempts, those efforts are stymied by the state of modern medicine;

Over the past 10 years, we have done a tremendous job of constructing expensive fortresses around patient information known as electronic health records (EHRs). Billions of dollars have been spent implementing, upgrading, and optimizing. In spite of this, physicians are increasingly frustrated by EHRs (and in many cases, long to return to the days of paper). It isn’t surprising, then, that patients are frustrated as well. We use terms such as “patient-centered care,” but patients feel like they are not in the center at all. Instead, they can find themselves feeling like complete outsiders, at the mercy of the medical juggernaut to make sure they have the appropriate information when they need it. There are several issues that contribute to the frustrations of physicians and patients, but two in particular warrant attention. The first is the diversity of Health IT systems and ongoing issues with EHR interoperability. The second is a provincial attitude surrounding transparency and medical record ownership. We will discuss both of these here, as well as recent legislation designed to advance both concerns.

We have written in previous columns about the many challenges of interoperability. Electronic health records, sold by different vendors, typically won’t “talk” to each other. In spite of years of maturation, issues of compatibility remain. Patient data locked inside of one EHR is not easily accessible by a physician using a different EHR. While efforts have been made to streamline information sharing, there are still many fortresses that cannot be breached.

Bridging the moat

The 21st Century Cures Act, enacted by Congress in December of 2016, seeks to define and require interoperability while addressing many other significant problems in health care. According to the legislation, true interoperability means that health IT should enable the secure exchange of electronic health information with other electronic record systems without special effort on the part of the user; the process should be seamless and shouldn’t be cumbersome for physicians or patients. It also must be fully supported by EHR vendors, but those vendors have been expressing significant concerns with the ways in which the act is being interpreted.

In a recent blog post, the HIMSS Electronic Health Record Association – a consortium of vendors including Epic, Allscripts, eClinicalWorks, as well as several others – expressed “significant concerns regarding timelines, ambiguous language, disincentives for innovation, and definitions related to information blocking.”1 This is not surprising, as the onus for improving interoperability falls squarely on their shoulders, and the work to get there is arduous. Regardless of one’s interpretation, the goal of the Cures act is clear: Arrive at true interoperability in the shortest period of time, while eliminating barriers that prevent patients from accessing their health records. In other words, it asks for the avoidance of “information blocking.”

Breaching the gate

Information blocking, as defined by the Cures Act, is “a practice by a health care provider, health IT developer, health information exchange, or health information network that … is likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.”2 This practice is explicitly prohibited by the legislation – and is ethically wrong – yet it continues to occur implicitly every day as it has for many years. Even if unintentional and solely because of the growing complexity of our information systems, it makes accessing health information incredibly cumbersome for patients. Even worse, attempts to improve patients’ ability to access their health records have only created additional obstacles.

HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) was designed to protect patient confidentiality and create security around protected health information. While noble in purpose, many have found it burdensome to work within the parameters set forth in the law. Physicians and patients needing legitimate access to clinical data discover endless release forms and convoluted processes standing in their way. Access to the information eventually comes in the form of reams of printed paper or faxed notes that cannot be easily consumed by or integrated into other systems.

The Meaningful Use initiative, while envisioned to improve data exchange and enhance population health, did little to help. Instead of enabling documentation efficiency and improving patient access, it promoted the proliferation of incompatible EHRs and poorly conceived patient portals. It also created heavy costs for both the federal government and physicians and was largely ineffective at producing systems whose use could be considered meaningful. The federal government paid out as much as $44,000 per physician to incentivize them to purchase medical records, while physicians often spent more than the $44,000 and, in many cases, wound up with EHRs that didn’t work well and had to be replaced.

Authors and supporters of the 21st Century Cures Act are hoping to avoid the shortcomings of prior legislation by attaching financial penalties to health care providers or IT vendors who engage in information blocking. While allowing for exceptions in appropriate cases, the law is clear: Patients deserve complete access to their medical records. While this goes against tradition, it has been proven to result in better outcomes.

Initiatives such as the OpenNotes movement have been pushing the value of full transparency for some time, and their website includes a long list of numerous examples to prove it. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated increased physician and patient satisfaction when both parties have ready access to health information. We believe that we, as physicians, should fully support the idea and lobby our EHR vendors to do the same.

It is time to tear down the impenetrable fortresses of traditional medicine, then work diligently to rebuild them with our patients safely inside.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. The Electronic Health Record Association blog

"A fortress not only protects those inside of it, but it also enslaves them to work.”

– Anthony T. Hincks

As physicians, we spend a great deal of time intending to do our best for the people we serve. We believe fundamentally in the idea that our patients come first, and we toil daily to exercise that belief. We also want our patients to feel they are driving their care as active participants along the journey. Yet time and time again, despite our greatest attempts, those efforts are stymied by the state of modern medicine;

Over the past 10 years, we have done a tremendous job of constructing expensive fortresses around patient information known as electronic health records (EHRs). Billions of dollars have been spent implementing, upgrading, and optimizing. In spite of this, physicians are increasingly frustrated by EHRs (and in many cases, long to return to the days of paper). It isn’t surprising, then, that patients are frustrated as well. We use terms such as “patient-centered care,” but patients feel like they are not in the center at all. Instead, they can find themselves feeling like complete outsiders, at the mercy of the medical juggernaut to make sure they have the appropriate information when they need it. There are several issues that contribute to the frustrations of physicians and patients, but two in particular warrant attention. The first is the diversity of Health IT systems and ongoing issues with EHR interoperability. The second is a provincial attitude surrounding transparency and medical record ownership. We will discuss both of these here, as well as recent legislation designed to advance both concerns.

We have written in previous columns about the many challenges of interoperability. Electronic health records, sold by different vendors, typically won’t “talk” to each other. In spite of years of maturation, issues of compatibility remain. Patient data locked inside of one EHR is not easily accessible by a physician using a different EHR. While efforts have been made to streamline information sharing, there are still many fortresses that cannot be breached.

Bridging the moat

The 21st Century Cures Act, enacted by Congress in December of 2016, seeks to define and require interoperability while addressing many other significant problems in health care. According to the legislation, true interoperability means that health IT should enable the secure exchange of electronic health information with other electronic record systems without special effort on the part of the user; the process should be seamless and shouldn’t be cumbersome for physicians or patients. It also must be fully supported by EHR vendors, but those vendors have been expressing significant concerns with the ways in which the act is being interpreted.

In a recent blog post, the HIMSS Electronic Health Record Association – a consortium of vendors including Epic, Allscripts, eClinicalWorks, as well as several others – expressed “significant concerns regarding timelines, ambiguous language, disincentives for innovation, and definitions related to information blocking.”1 This is not surprising, as the onus for improving interoperability falls squarely on their shoulders, and the work to get there is arduous. Regardless of one’s interpretation, the goal of the Cures act is clear: Arrive at true interoperability in the shortest period of time, while eliminating barriers that prevent patients from accessing their health records. In other words, it asks for the avoidance of “information blocking.”

Breaching the gate

Information blocking, as defined by the Cures Act, is “a practice by a health care provider, health IT developer, health information exchange, or health information network that … is likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.”2 This practice is explicitly prohibited by the legislation – and is ethically wrong – yet it continues to occur implicitly every day as it has for many years. Even if unintentional and solely because of the growing complexity of our information systems, it makes accessing health information incredibly cumbersome for patients. Even worse, attempts to improve patients’ ability to access their health records have only created additional obstacles.

HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) was designed to protect patient confidentiality and create security around protected health information. While noble in purpose, many have found it burdensome to work within the parameters set forth in the law. Physicians and patients needing legitimate access to clinical data discover endless release forms and convoluted processes standing in their way. Access to the information eventually comes in the form of reams of printed paper or faxed notes that cannot be easily consumed by or integrated into other systems.

The Meaningful Use initiative, while envisioned to improve data exchange and enhance population health, did little to help. Instead of enabling documentation efficiency and improving patient access, it promoted the proliferation of incompatible EHRs and poorly conceived patient portals. It also created heavy costs for both the federal government and physicians and was largely ineffective at producing systems whose use could be considered meaningful. The federal government paid out as much as $44,000 per physician to incentivize them to purchase medical records, while physicians often spent more than the $44,000 and, in many cases, wound up with EHRs that didn’t work well and had to be replaced.

Authors and supporters of the 21st Century Cures Act are hoping to avoid the shortcomings of prior legislation by attaching financial penalties to health care providers or IT vendors who engage in information blocking. While allowing for exceptions in appropriate cases, the law is clear: Patients deserve complete access to their medical records. While this goes against tradition, it has been proven to result in better outcomes.

Initiatives such as the OpenNotes movement have been pushing the value of full transparency for some time, and their website includes a long list of numerous examples to prove it. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated increased physician and patient satisfaction when both parties have ready access to health information. We believe that we, as physicians, should fully support the idea and lobby our EHR vendors to do the same.

It is time to tear down the impenetrable fortresses of traditional medicine, then work diligently to rebuild them with our patients safely inside.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. The Electronic Health Record Association blog

"A fortress not only protects those inside of it, but it also enslaves them to work.”

– Anthony T. Hincks

As physicians, we spend a great deal of time intending to do our best for the people we serve. We believe fundamentally in the idea that our patients come first, and we toil daily to exercise that belief. We also want our patients to feel they are driving their care as active participants along the journey. Yet time and time again, despite our greatest attempts, those efforts are stymied by the state of modern medicine;

Over the past 10 years, we have done a tremendous job of constructing expensive fortresses around patient information known as electronic health records (EHRs). Billions of dollars have been spent implementing, upgrading, and optimizing. In spite of this, physicians are increasingly frustrated by EHRs (and in many cases, long to return to the days of paper). It isn’t surprising, then, that patients are frustrated as well. We use terms such as “patient-centered care,” but patients feel like they are not in the center at all. Instead, they can find themselves feeling like complete outsiders, at the mercy of the medical juggernaut to make sure they have the appropriate information when they need it. There are several issues that contribute to the frustrations of physicians and patients, but two in particular warrant attention. The first is the diversity of Health IT systems and ongoing issues with EHR interoperability. The second is a provincial attitude surrounding transparency and medical record ownership. We will discuss both of these here, as well as recent legislation designed to advance both concerns.

We have written in previous columns about the many challenges of interoperability. Electronic health records, sold by different vendors, typically won’t “talk” to each other. In spite of years of maturation, issues of compatibility remain. Patient data locked inside of one EHR is not easily accessible by a physician using a different EHR. While efforts have been made to streamline information sharing, there are still many fortresses that cannot be breached.

Bridging the moat

The 21st Century Cures Act, enacted by Congress in December of 2016, seeks to define and require interoperability while addressing many other significant problems in health care. According to the legislation, true interoperability means that health IT should enable the secure exchange of electronic health information with other electronic record systems without special effort on the part of the user; the process should be seamless and shouldn’t be cumbersome for physicians or patients. It also must be fully supported by EHR vendors, but those vendors have been expressing significant concerns with the ways in which the act is being interpreted.

In a recent blog post, the HIMSS Electronic Health Record Association – a consortium of vendors including Epic, Allscripts, eClinicalWorks, as well as several others – expressed “significant concerns regarding timelines, ambiguous language, disincentives for innovation, and definitions related to information blocking.”1 This is not surprising, as the onus for improving interoperability falls squarely on their shoulders, and the work to get there is arduous. Regardless of one’s interpretation, the goal of the Cures act is clear: Arrive at true interoperability in the shortest period of time, while eliminating barriers that prevent patients from accessing their health records. In other words, it asks for the avoidance of “information blocking.”

Breaching the gate

Information blocking, as defined by the Cures Act, is “a practice by a health care provider, health IT developer, health information exchange, or health information network that … is likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.”2 This practice is explicitly prohibited by the legislation – and is ethically wrong – yet it continues to occur implicitly every day as it has for many years. Even if unintentional and solely because of the growing complexity of our information systems, it makes accessing health information incredibly cumbersome for patients. Even worse, attempts to improve patients’ ability to access their health records have only created additional obstacles.

HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) was designed to protect patient confidentiality and create security around protected health information. While noble in purpose, many have found it burdensome to work within the parameters set forth in the law. Physicians and patients needing legitimate access to clinical data discover endless release forms and convoluted processes standing in their way. Access to the information eventually comes in the form of reams of printed paper or faxed notes that cannot be easily consumed by or integrated into other systems.

The Meaningful Use initiative, while envisioned to improve data exchange and enhance population health, did little to help. Instead of enabling documentation efficiency and improving patient access, it promoted the proliferation of incompatible EHRs and poorly conceived patient portals. It also created heavy costs for both the federal government and physicians and was largely ineffective at producing systems whose use could be considered meaningful. The federal government paid out as much as $44,000 per physician to incentivize them to purchase medical records, while physicians often spent more than the $44,000 and, in many cases, wound up with EHRs that didn’t work well and had to be replaced.

Authors and supporters of the 21st Century Cures Act are hoping to avoid the shortcomings of prior legislation by attaching financial penalties to health care providers or IT vendors who engage in information blocking. While allowing for exceptions in appropriate cases, the law is clear: Patients deserve complete access to their medical records. While this goes against tradition, it has been proven to result in better outcomes.

Initiatives such as the OpenNotes movement have been pushing the value of full transparency for some time, and their website includes a long list of numerous examples to prove it. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated increased physician and patient satisfaction when both parties have ready access to health information. We believe that we, as physicians, should fully support the idea and lobby our EHR vendors to do the same.

It is time to tear down the impenetrable fortresses of traditional medicine, then work diligently to rebuild them with our patients safely inside.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. The Electronic Health Record Association blog

Electronic health records and the lost power of prose

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” Anton Chekhov

In March 2006, four programmers turned entrepreneurs launched Twitter. This revolutionary tool experienced a monumental growth in scale over the next 10 years from a handful of users sharing a few thousand messages (known as “tweets”) each day to a global social network of over 300 million users valued at over $25 billion dollars. In fact, on Election Day 2016, Twitter was the No. 1 source of breaking news1, and it has been used as a launchpad for everything from social activism to national revolutions.

When Twitter was first conceived, it was designed to operate through wireless phone carriers’ SMS messaging functionality (aka “via text message”). SMS messages are limited to just 160 characters, so Twitter’s creators decided to restrict tweets to 140 characters, allowing 20 characters for a username. This decision created a necessity for communication efficiency that harks back to the days of the telegraph. From the liberal use of contractions and abbreviations to the tireless search for the shortest synonyms possible, Twitter users have employed countless techniques to enable them to say more with less. While clever and creative, this extreme verbal austerity has pervaded other media as well, becoming the hallmark literary style of the current generation.

Contemporaneous with the Twitter revolution, the medical field has allowed technology to dramatically change its style of communication as well, but in the opposite way. We have become far less efficient in our use of words, yet we seem to be doing a really poor job of expressing ourselves.

Saying less with more

I was once asked to provide expert testimony in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Working in support of the defense, I endured question after question from the plaintiff’s legal team as they picked apart every aspect of the case. Of particular interest was the physician’s documentation. Sadly – yet perhaps unsurprisingly – it was poor. The defendant had clearly used an EHR template and clicked checkboxes to create his note, documenting history, physical exam, assessment, and plan without having typed a single word. While adequate for billing purposes, the note was missing any narrative that could communicate the story of what had transpired during the patient’s visit. Sure, the presenting symptoms and vital signs were there, but the no description of the patient’s appearance had been recorded? What had the physician been thinking? What unspoken messages had led the physician to make the decisions he had made?

Like Twitter, the dawn of EHRs created an entirely new form of communication, but instead of limiting the content of physicians’ notes it expanded it. Objectively, this has made for more complete notes. Subjectively, this has led to notes packed with data, yet devoid of meaningful narrative. While handwritten notes from the previous generation were brief, they included the most important elements of the patient’s history and often the physician’s thought process in forming the differential. The electronically generated notes of today are quite the opposite; they are dense, yet far from illuminating. A clinician referring back to the record might have tremendous difficulty discerning salient features amidst all of the “note bloat.”This puts the patient (and the provider, as in the case above) at risk. Details may be present, but the diagnosis will be missed without the story that ties them all together.

Writing a new chapter

Physicians hoping to create meaningful notes are often stymied by the technology at their disposal or the demands placed on their time. These issues, combined with an ever-growing number of regulatory requirements, are what led to the decay of narrative in the first place. As a result, doctors are looking for alternative ways to buck the trend and bring patients’ stories back to their medical records. These methods are often expensive or involved, but in many cases they dramatically improve quality and efficiency.

An example of a tool that allows doctors to achieve these goals is speech recognition technology. Instead of typing or clicking, physicians dictate into the EHR, creating notes that are typically richer and more akin to a story than a list of symptoms or data points. When voice-to-text is properly deployed and utilized, documentation improves along with efficiency. Alternately, many providers are now employing scribes to accompany them in the exam room and complete the medical record. Taking this step leads to more descriptive notes, better productivity, and happier providers. The use of scribes also seems to result in happier patients, who report better therapeutic interactions when their doctors aren’t typing or staring at a computer screen.

The above-mentioned methods for recording information about a patient during a visit may be too expensive or complicated for some providers, but there are other simple techniques that can be used without incurring additional cost or resources. Previsit planning is one such possibility. By reviewing patient charts in advance of appointments, physicians can look over results, identify preventive health gaps, and anticipate follow-up needs and medication refills. They can then create skeleton notes and prepopulate orders to reduce the documentation burden during the visit. While time consuming at first, physicians have reported this practice actually saves time in the long run and allows them to focus on recording the patient narrative during the visit.

Another strategy is even more simple in concept, though may seem counter-intuitive at first: get better acquainted with the electronic records system. That is, take the time to really learn and understand the tools designed to improve productivity that are available in your EHR, then use them judiciously; take advantage of templates and macros when they’ll make you more efficient yet won’t inhibit your ability to tell the patient’s story; embrace optimization but don’t compromise on narrative. By carefully choosing your words, you’ll paint a clearer picture of every patient and enable safer and more personalized care.

Reference

1. “For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media” New York Times. Nov. 8, 2016.

Breaking down blockchain: How this novel technology will unfetter health care

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

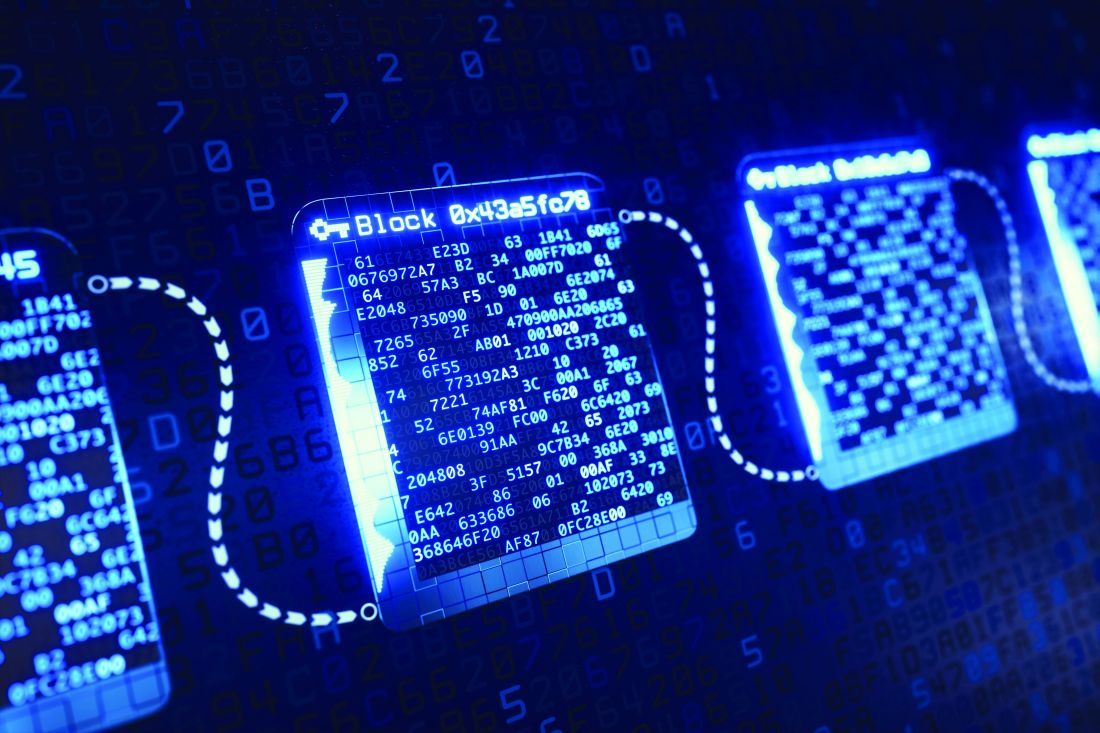

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.

The collaboration mentioned above is the latest, but certainly not the first, attempt to exploit the benefits of blockchain for health care. Other major players have already entered the game, and the field is growing quickly. While it’s easy to find their efforts admirable, corporate involvement also means there is money to be saved or made in the space. Chris Ward, head of product for PNC Treasury Management, alluded to this as he commented publicly in the press release: “This collaboration will enable health care–related data and business transactions to occur in way that addresses market demands for transparency and security, while making it easier for the patient, payer, and provider to handle payments. Using this technology, we can remove friction, duplication, and administrative costs that continue to plague the industry.”

Industry executives recognize that interoperability is still the greatest challenge facing the future of health care and are particularly sensitive to the costs of not facing the challenge successfully. Clearly, they see an investment in blockchains as an opportunity to be part of a financially beneficial solution.

Why we should care

As we’ve now covered, there are many advantages of blockchain technology. In fact, we see it as the natural evolution of the patient-centered EHR. Instead of siloed and proprietary information spread across disparate EHRs that can’t communicate, the future of data exchange will be more transparent, yet more secure. Blockchain represents a unique opportunity to democratize the availability of health care information while increasing information quality and lowering costs. It is also shaping up to be the way we’ll exchange sensitive data in the future.

Don’t believe us? Just ask any 9-year-old.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter, @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Reference

1. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2019-01-24-Aetna-Anthem-Health-Care-Service-Corporation-PNC-Bank-and-IBM-announce-collaboration-to-establish-blockchain-based-ecosystem-for-the-healthcare-industry

One evening in 2016, my 9-year-old son suggested we use Bitcoin to purchase something on the Microsoft Xbox store. Surprised by his suggestion, I was suddenly struck with two thoughts: 1) Microsoft, by accepting Bitcoin, was validating cryptocurrency as a credible form of payment, and 2) I was getting old. My 9-year-old seemed to have a better understanding of a new technology than I did, hardly the first time – or the last time – that happened. In spite of my initial feelings of defeat, I resolved not to cede victory to my son without a fight. I immediately set out to understand cryptocurrencies and, more importantly, the technology underpinning them known as blockchain.

Even just a few years ago, my ignorance of how blockchains work may have been acceptable, but it hardly seems acceptable now. Much more than just cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is beginning to affect every industry that values information sharing and security, and it is about to usher in a revolution in health care. But what are blockchains, and why are they so important?

Explaining blockchains

Blockchains were first conceptualized almost 3 decades ago, but the invention of the first blockchain as we know it today occurred in 2008 by Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of Bitcoin. Blockchains can be thought of as a way to store and communicate information while ensuring its integrity and security. Admittedly, the technology can be a bit confusing, but we’ll attempt to simplify it by focusing on a few fundamental elements.

As the name indicates, the blockchain model relies on a chain of connected blocks. Each block contains some data (which can be financial, medical, legal, or anything else) and bears a unique fingerprint known as a “hash.” Each hash is different and depends entirely on the data stored in the block. In other words, if the contents of the block change, the hash changes, creating an entirely new fingerprint. Each block on the chain also keeps a record of the hash of the previous block. This “links” the chain together, and is the first key to its robust security: If any block is tampered with, its fingerprint will change and it will no longer be linked, thus invalidating all following blocks on the chain.

Ensuring the integrity of the blockchain doesn’t stop there. Just as actual fingerprints can be spoofed by enterprising criminals, hash technology isn’t enough to provide complete security. Thus, several other security features are built into blockchains, with the most noteworthy and important being “decentralization.” This means that blockchains are not stored on any single computer. On the contrary, duplicate copies of every blockchain exist on thousands of computers around the world, creating redundancy and minimizing the vulnerability that any single chain could be tampered with. Before any change in the blockchain can be made and accepted, it must be validated by a majority of the computers storing the chain.

If this all seems perplexing, that’s because it is. Blockchains are complex and difficult to visualize. (But if you’d like a deeper understanding, there are many great YouTube videos that do a great job explaining them.) For now, just remember this: Blockchains are very secure yet highly accessible, and will be essential to how data – especially health data – are stored and communicated in the future.

Blockchains in health care

On Jan. 24, 2019, five major companies (Aetna, Anthem, Health Care Services, IBM, and PNC Bank) “announced a new collaboration to design and create a network using blockchain technology to improve transparency and interoperability in the health care industry.”1 This team of industry leaders is hoping to build the engine that will power the future and impact how health records are created, maintained, and communicated. They’ll achieve this by taking advantage of blockchain’s inclusiveness and decentralization, storing records in a manner that is safe and accessible anywhere a patient seeks care. Because of the redundancy built into blockchains, they can also ensure data integrity. Physicians will benefit from information that is easy to obtain and always accurate; patients will benefit by gaining greater access and ownership of their personal medical records.