User login

Deprescribing: A simple method for reducing polypharmacy

CASE An 82-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, anxiety, urge urinary incontinence, constipation, and bilateral knee osteoarthritis presents to her primary care physician’s office after a fall. She reports that she visited the emergency department (ED) a week ago after falling in the middle of the night on her way to the bathroom. This is the third fall she’s had this year. On chart review, she had a blood pressure (BP) of 112/60 mm Hg and a blood glucose level of 65 mg/dL in the ED. All other testing (head imaging, chest x-ray, urinalysis) was normal. The ED physician recommended that she stop taking her lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and glipizide extended release (XL) until her follow-up appointment. Today, she asks about the need to restart these medications.

Polypharmacy is common among older adults due to a high prevalence of chronic conditions that often require multiple medications for optimal management. Cut points of 5 or 9 medications are frequently used to define polypharmacy. However, some define polypharmacy as taking a medication that lacks an indication, is ineffective, or is duplicating treatment provided by another medication.

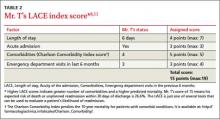

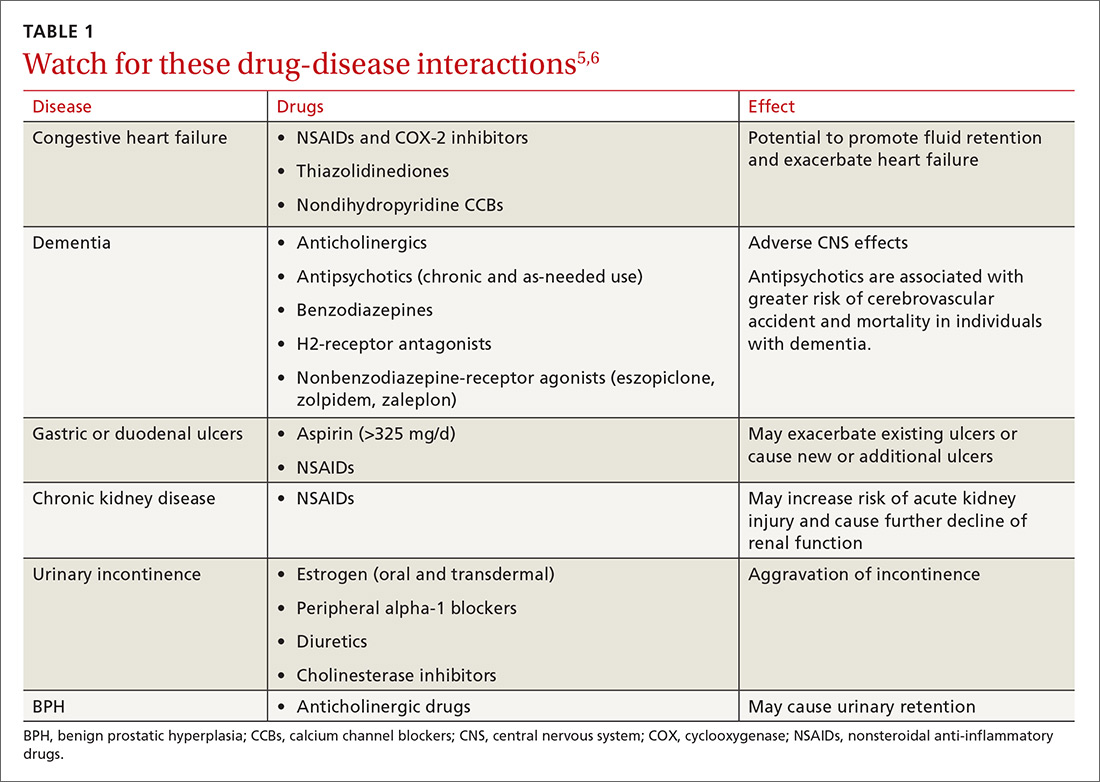

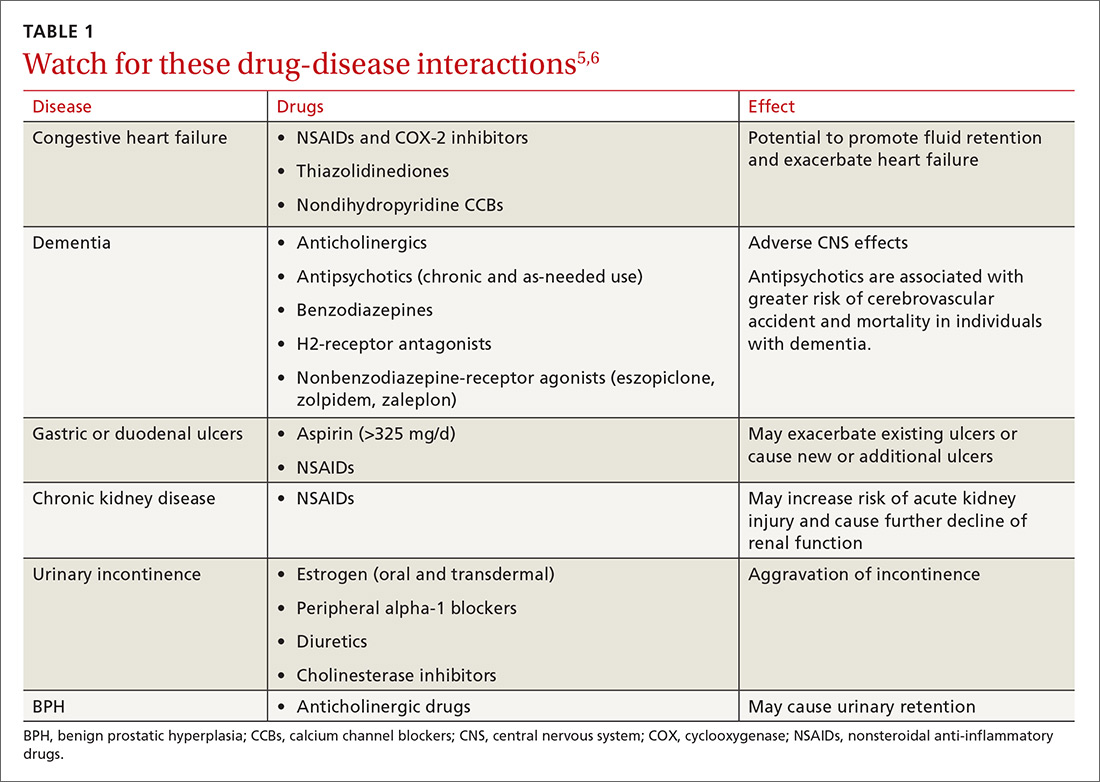

Either way, polypharmacy is associated with multiple negative consequences, including an increased risk for adverse drug events (ADEs),1-4 drug-drug and drug-disease interactions (TABLE 15,6),7 reduced functional capacity,8 multiple geriatric syndromes (TABLE 25,9-12), medication non-adherence,13 and increased mortality.14 Polypharmacy also contributes to increased health care costs for both the patient and the health care system.15

Taking a step back. Polypharmacy often results from prescribing cascades, which occur when an adverse drug effect is misinterpreted as a new medical problem, leading to the prescribing of more medication to treat the initial drug-induced symptom. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), which are medications that should be avoided in older adults and in those with certain conditions, are also more likely to be prescribed in the setting of polypharmacy.16

Deprescribing is the process of identifying and discontinuing medications that are unnecessary, ineffective, and/or inappropriate in order to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. Deprescribing is a collaborative process that involves weighing the benefits and harms of medications in the context of a patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences. This article reviews polypharmacy and discusses safe and effective deprescribing strategies for older adults in the primary care setting.

[polldaddy:9781245]

How many people on how many meds?

According to a 2016 study, 36% of community-dwelling older adults (ages 62-85 years) were taking 5 or more prescription medications in 2010 to 2011—up from 31% in 2005 to 2006.17 When one narrows the population to older adults in the United States who are hospitalized, almost half (46%) take 7 or more medications.18 Among frail, older US veterans at hospital discharge, 40% were prescribed 9 or more medications, with 44% of these patients receiving at least one unnecessary drug.19

The challenges of multimorbidity

In the United States, 80% of those 65 and older have 2 or more chronic conditions, or multimorbidity.20 Clinical practice guidelines making recommendations for the management of single conditions, such as heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes, often suggest the use of 2 or more medications to achieve optimal management and fail to provide guidance in the setting of multimorbidity. Following treatment recommendations for multiple conditions predictably leads to polypharmacy, with complicated, costly, and burdensome regimens.

Further, the research contributing to the development of clinical practice guidelines frequently excludes older adults and those with multimorbidity, reducing applicability in this population. As a result, many treatment recommendations have uncertain benefit and may be harmful in the multimorbid older patient.21

CASE In addition to the patient’s multimorbidity, she had a stroke at age 73 and has some mild residual left-sided weakness. Functionally, she is independent and able to perform her activities of daily living and her instrumental activities of daily living. She lives alone, quit smoking at age 65, and has an occasional glass of wine during family parties. The patient’s daughter and granddaughter live 2 blocks away.

Her current medications include glipizide XL 10 mg/d and lisinopril-HCTZ 20-25 mg/d, which she has temporarily discontinued at the ED doctor’s recommendation, as well as: amlodipine 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg BID, senna 8.6 mg/d, docusate 100 mg BID, furosemide 40 mg/d, and ibuprofen 600 mg/d (for knee pain). She reports taking omeprazole 20 mg/d “for almost 20 years,” even though she has not had any reflux symptoms in recent memory. After her stroke, she began taking atorvastatin 10 mg/d, aspirin 81 mg/d, and clopidogrel 75 mg/d, which she continues to take today. About a year ago, she started oxybutynin 5 mg/d for urinary incontinence, but she has not noticed significant relief. Additionally, she takes lorazepam 1 mg for insomnia most nights of the week.

A review of systems reveals issues with chronic constipation and intermittent dizziness, but is otherwise negative. The physical examination reveals a well-appearing woman with a body mass index of 26. Her temperature is 98.5° F, her heart rate is 78 beats/min and regular, her respirations are 14 breaths/min, and her BP is 117/65 mm Hg. Orthostatic testing is negative. Her heart, lung, and abdominal exams are within normal limits. Her timed up and go test is 14 seconds. Her blood glucose level today in the office after eating breakfast 2 hours ago is 135 mg/dL (normal: <140 mg/dL). Laboratory tests performed at the time of the ED visit show a creatinine level of 1.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL), a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 44 units (normal range: >60 units), a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL (normal range: 12-15.5 g/dL), and a thyroid stimulating hormone level of 1.4 mIU/L (normal range: 0.5-8.9 mIU/L). A recent hemoglobin A1C is 6.8% (normal: <5.7%), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 103 mg/dL (optimal <100 mg/dL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level is 65 mg/dL (optimal >60 mg/dL). An echocardiogram performed a year ago showed mild aortic stenosis with normal systolic and diastolic function.

Starting the deprescribing process: Several approaches to choose from

The goal of deprescribing is to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. It is a process defined as, “reviewing all current medications; identifying medications to be ceased, substituted, or reduced; planning a deprescribing regimen in partnership with the patient; and frequently reviewing and supporting the patient.”22 A medication review should include prescription, over-the-counter (OTC), and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) agents.

Until recently, studies evaluating the process of deprescribing across drug classes and disease conditions were limited, but new research is beginning to show its potential impact. After deprescribing, patients experience fewer falls and show improvements in cognition.23 While there have not yet been large randomized trials to evaluate deprescribing, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that use of patient-specific deprescribing interventions is associated with improved survival.24 Importantly, there have been no reported adverse drug withdrawal events or deaths associated with deprescribing.23

Smaller studies have reported additional benefits including decreases in health care costs, reductions in drug-drug interactions and PIMs, improvements in medication adherence, and increases in patient satisfaction.25 In addition, the removal of unnecessary medications may allow for increased consideration of prescribing appropriate medications with known benefit.25

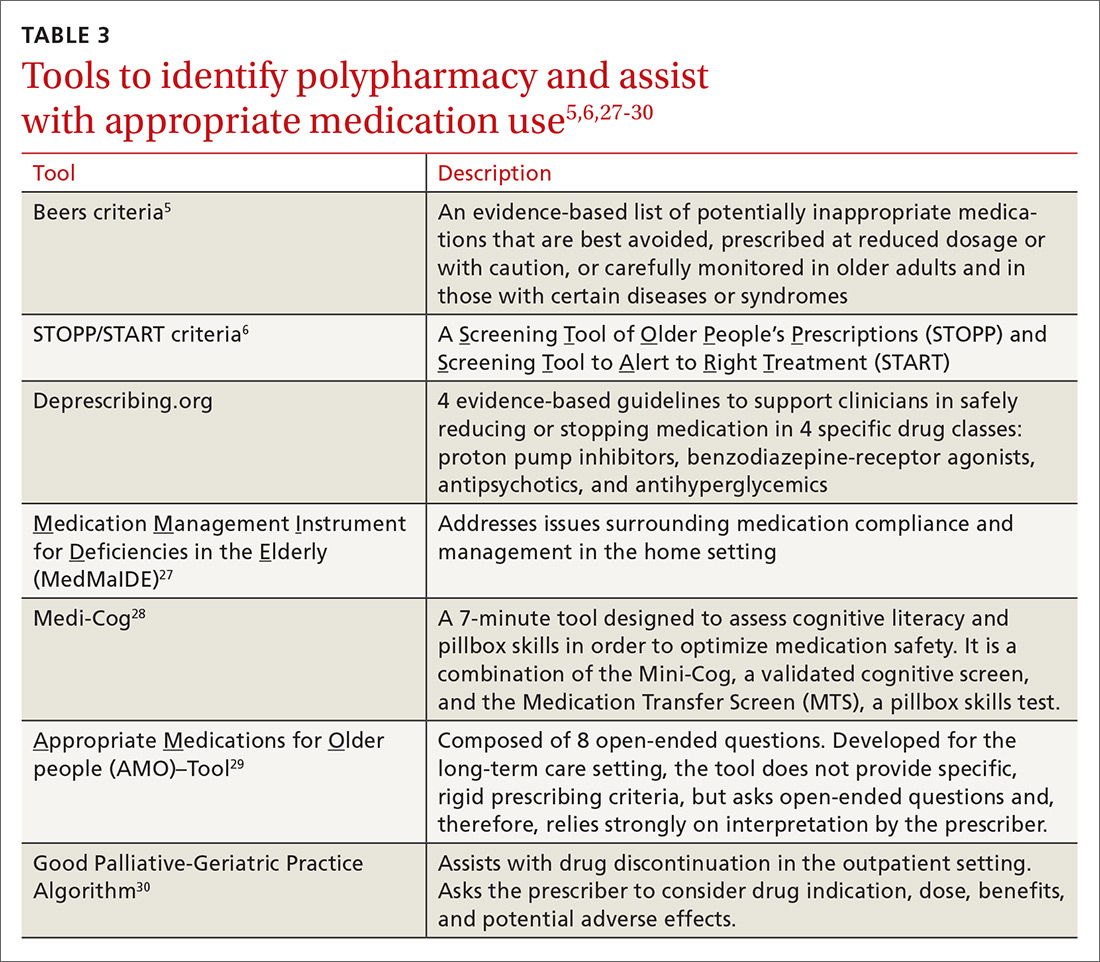

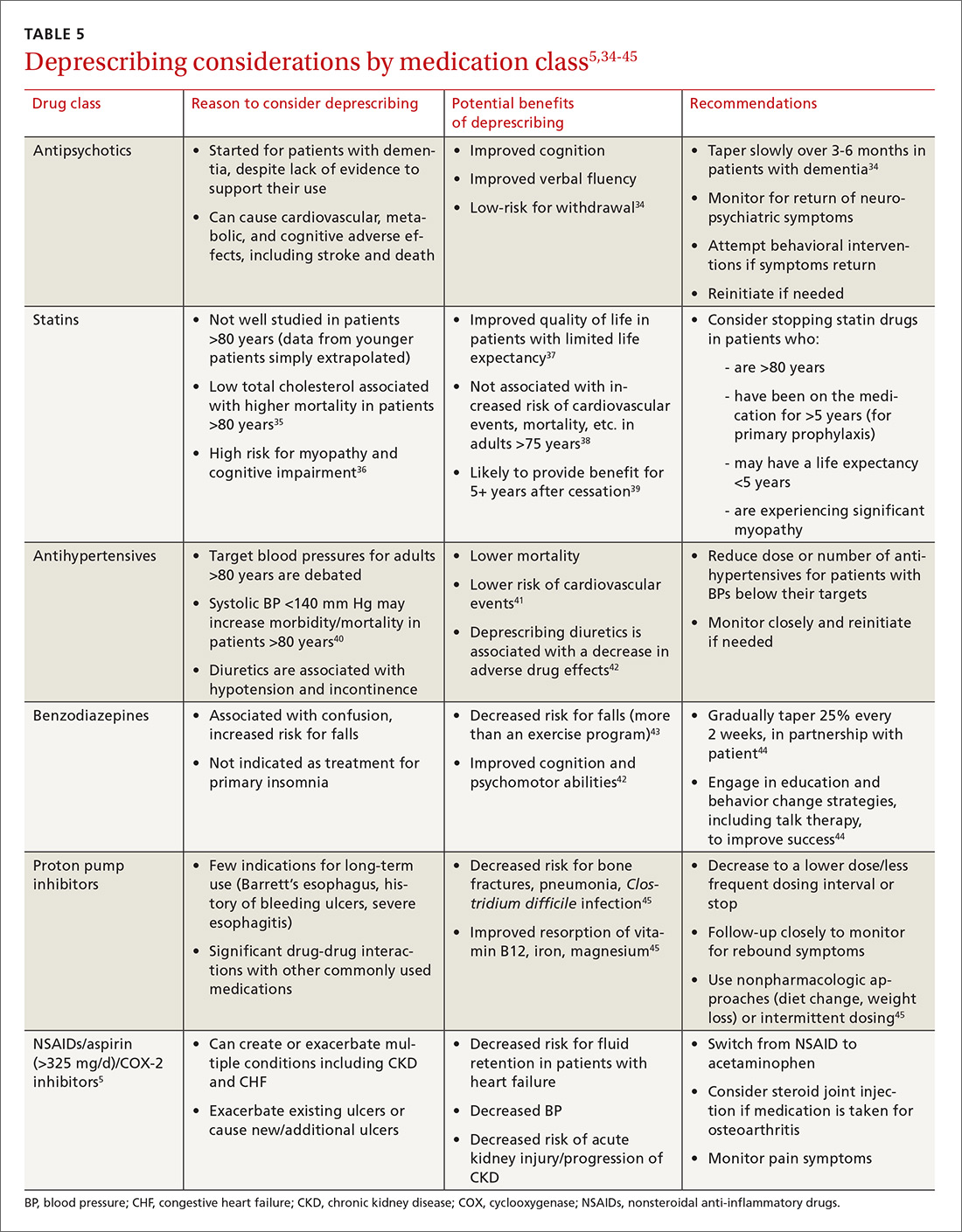

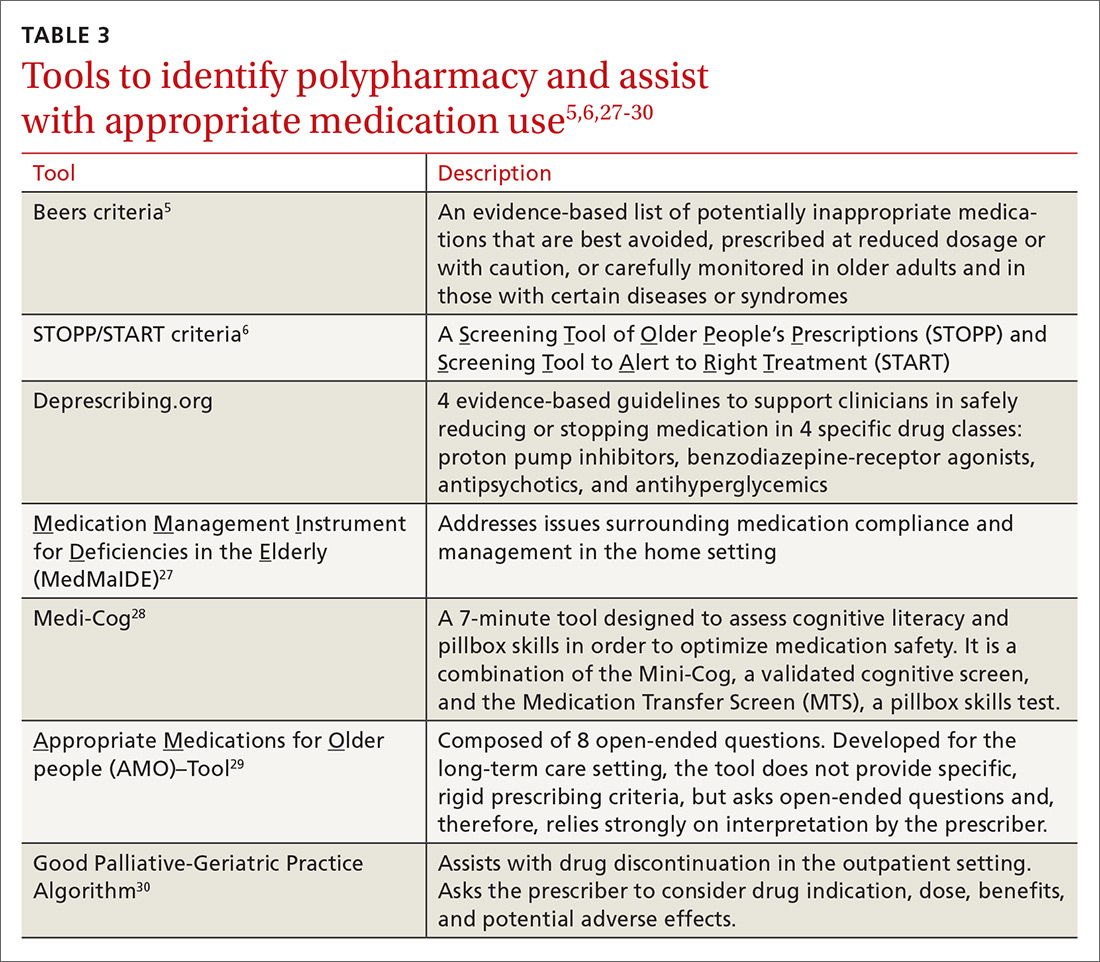

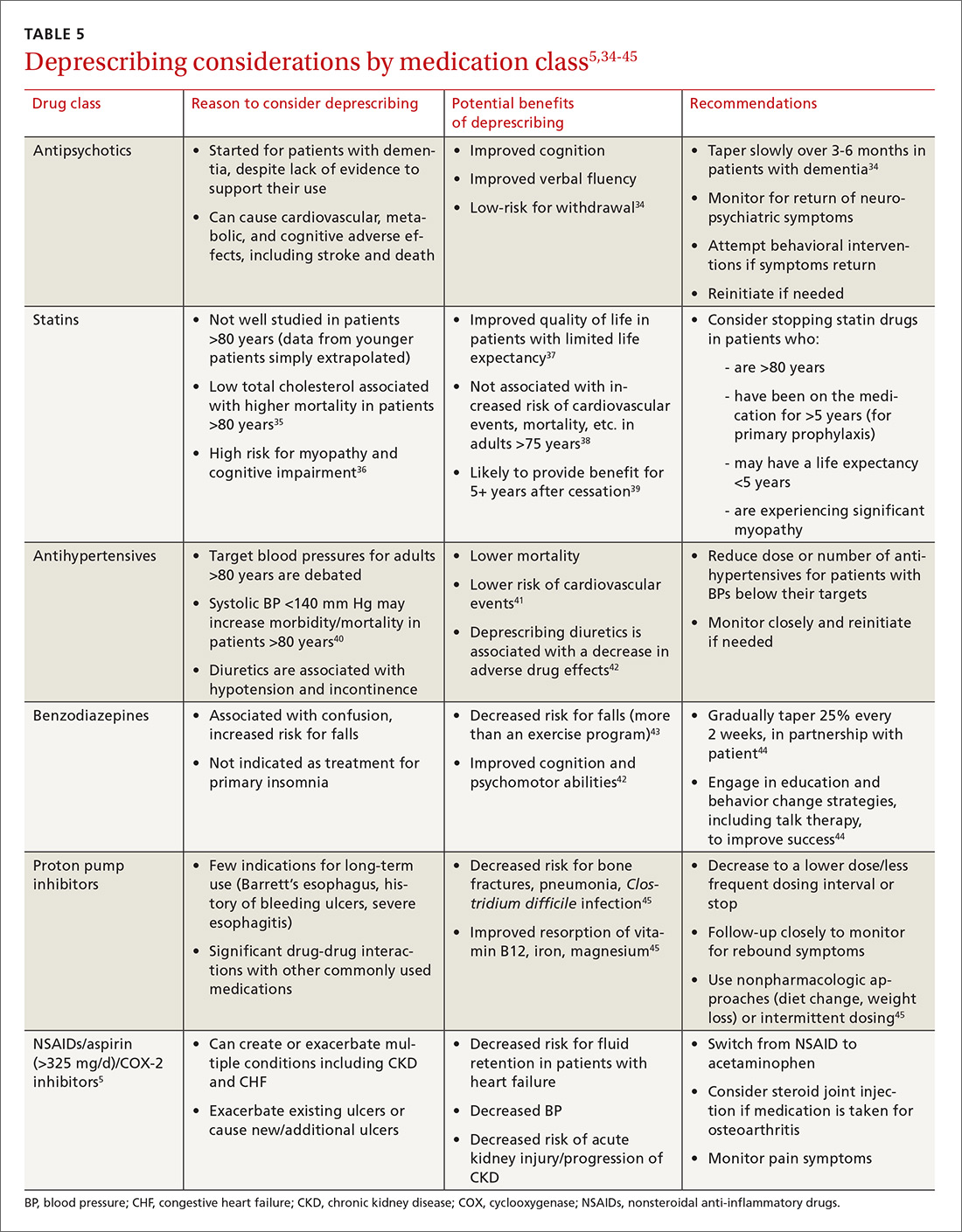

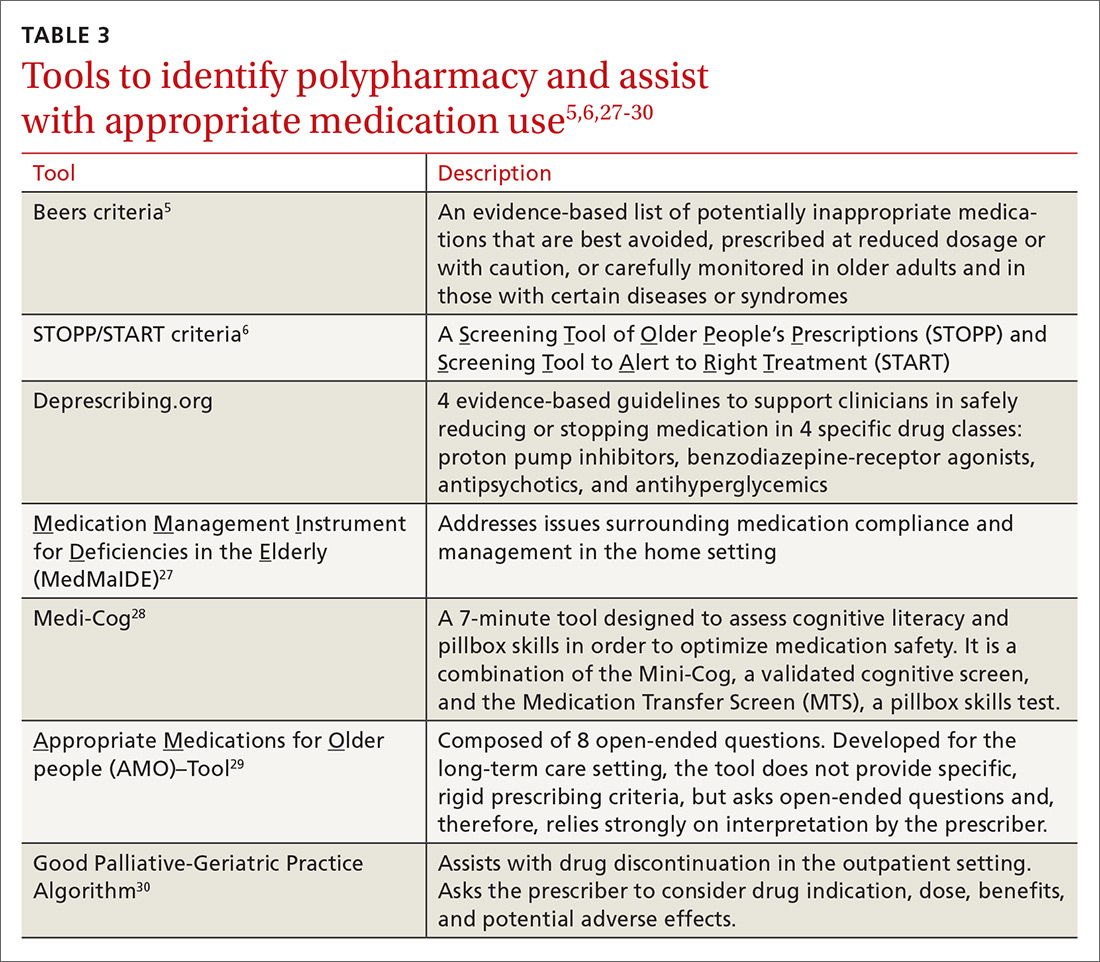

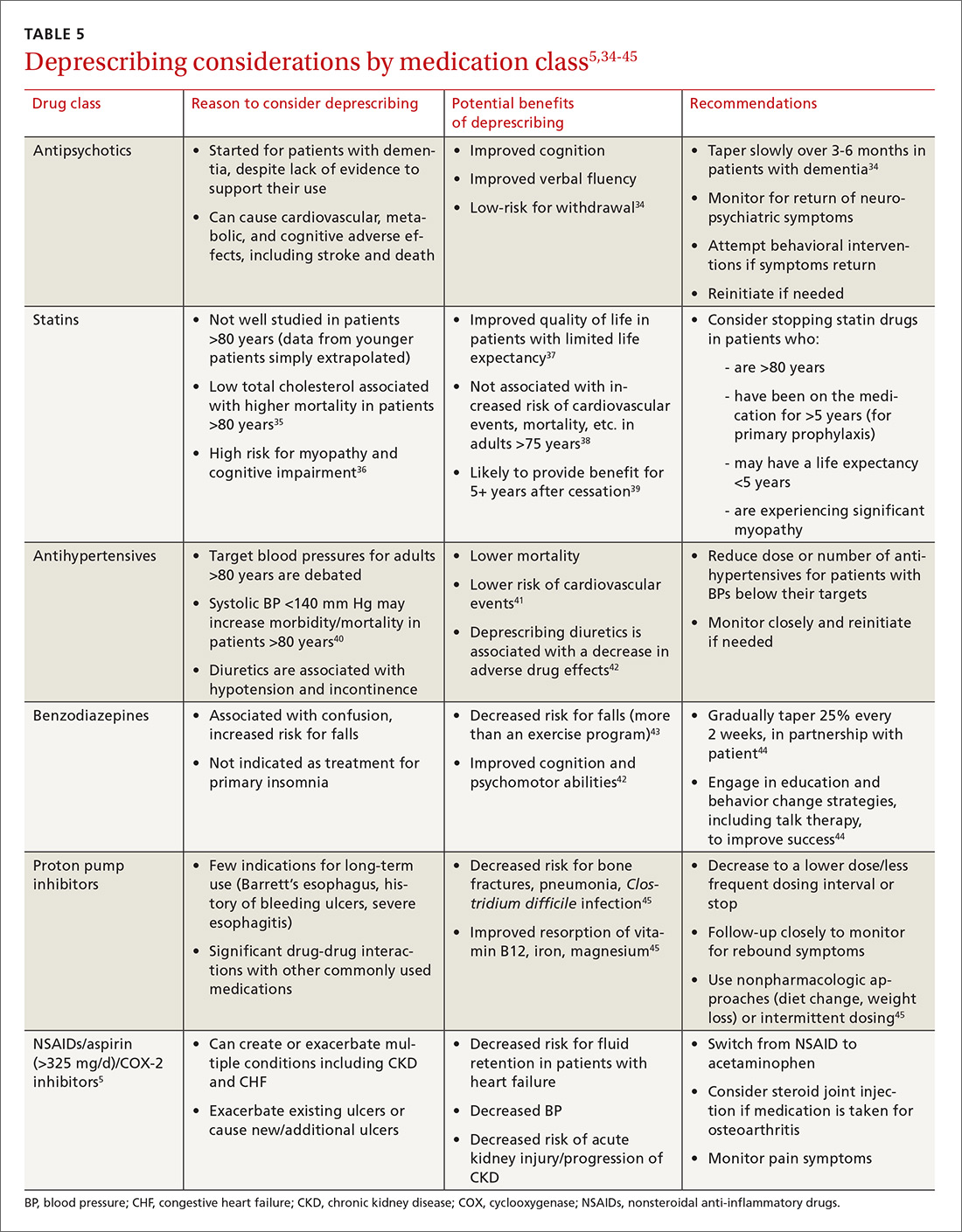

Practically speaking, every encounter between a patient and health care provider is an opportunity to reduce unnecessary medications. Electronic alert systems at pharmacies and those embedded within electronic health record (EHR) systems can also prompt a medication review and an effort to deprescribe.26 Evidence-based tools to identify polypharmacy and guide appropriate medication use are listed in TABLE 3.5,6,27-30 In addition, suggested approaches to beginning the deprescribing process are included in TABLE 4.5,31-33 And a medication class-based approach to deprescribing is provided in TABLE 5.5,34-45

Although no gold standard process exists for deprescribing, experts suggest that any deprescribing protocol should include the following steps:32,46

1. Start with a “brown bag” review of the patient’s medications.

Have the patient bring all of his/her medications in a bag to the visit; review them together or have the medication history taken by a pharmacist. Determine and discuss the indication for each medication and its effectiveness for that indication. Consider the potential benefits and harms of each medication in the context of the patient’s care goals and preferences. Assess whether the patient is taking all of the medications that have been prescribed, and identify any reasons for missed pills (eg, adverse effects, dosing regimens, understanding, cognitive issues).

2. Talk to the patient about the deprescribing process.

Talk with the patient about the risks and benefits of deprescribing, and prioritize which medications to address in the process. Prioritize the medications by balancing patient preferences with available pharmacologic evidence. If there is a lack of evidence supporting the benefits for a particular medication, consider known or suspected adverse effects, the ease or burden of the dosing regimen, the patient’s preferences and goals of care, remaining life expectancy, the time until drug benefit is appreciated, and the length of drug benefit after discontinuation.

3. Deprescribe medications.

If you are going to taper a medication, develop a schedule in partnership with the patient. Stop one medication at a time so that you can monitor for withdrawal symptoms or for the return of a condition.

Acknowledging potential barriers to deprescribing may help structure conversations and provide anticipatory guidance to patients and their families. Working to overcome these barriers will help maximize the benefits of deprescribing and help to build trust with patients.

Patient-driven barriers include fear of a condition worsening or returning, lack of a suitable alternative, lack of ongoing support to manage a particular condition, a previous bad experience with medication cessation, and influence from other care providers (eg, family, home caregivers, nurses, specialists, friends). Patients and family members sometimes cling to the hope of future effectiveness of a treatment, especially in the case of medications like donepezil for dementia.47 Utilizing a team-based and stepwise patient approach to deprescribing aims to provide hesitant patients with appropriate amounts of education and support to begin to reduce unnecessary medicines.

Provider-driven barriers include feeling uneasy about contradicting a specialist’s recommendations for initiation/continuation of specific medications, fear of causing withdrawal symptoms or disease relapse, and lack of specific data to adequately understand and assess benefits and harms in the older adult population. Primary care physicians have also acknowledged worry about discussing life expectancy and that patients will feel their care is being reduced or “downgraded.”48 Finally, there is limited time in which these complex shared decision-making conversations can take place. Thus, if medications are not causing a noticeable problem, it is often easier to just continue them.

One way to overcome some of these concerns is to consider working with a clinical pharmacist. By gaining information regarding medication-specific factors, such as half-life and expected withdrawal patterns, you can feel more confident deprescribing or continuing medications.

Additionally, communicating closely with specialists, ideally with the help of an integrated EHR, can allow you to discuss indications for particular medications or concerns about adverse effects, limited benefits, or difficulty with compliance, so that you can develop a collaborative, cohesive, and patient-centered plan. This, in turn, may improve patient understanding and compliance.

4. Create a follow-up plan.

At the time of deprescribing a medication, develop a plan with the patient for monitoring and assessment. Ensure that the patient understands which symptoms may occur in the event of drug withdrawal and which symptoms may suggest the return of a condition. Make sure that other supports are in place if needed (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, physical therapy, social support or assistance) to help ensure that medication cessation is successful.

CASE During the office visit, you advise the patient that her BP looks normal, her blood sugar is within an appropriate range, and she is lucky to have not sustained any injuries after her most recent fall. In addition to discussing the benefits of some outpatient physical therapy to help with her balance, you ask if she would like to discuss reducing her medications. She is agreeable and asks for your recommendations.

You are aware of several resources that can help you with your recommendations, among them the STOPP/START6 and Beers criteria,5 as well as the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm.30

If you were to use the STOPP/START and Beers criteria, you might consider stopping:

- lorazepam, which increases the risk of falls and confusion.

- ibuprofen, since this patient has only mild osteoarthritis pain, and ibuprofen has the potential for renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal toxicities.

- oxybutynin, because it could be contributing to the patient’s constipation and cause confusion and falls.

- furosemide, since the patient has no clinical heart failure.

- omeprazole, since the indication is unknown and the patient has no history of ulceration, esophagitis, or symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease.

After reviewing the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm,30 you might consider stopping:

- clopidogrel, as there is no clear indication for this medication in combination with aspirin in this patient.

- glipizide XL, as this patient’s A1c is below goal and this medication puts her at risk of hypoglycemia and its associated morbidities.

- metformin, as it increases her risk of lactic acidosis because her GFR is <45 units.

- docusate, as the evidence to show clear benefit in improving chronic constipation in older adults is lacking.

You tell your patient that there are multiple medications to consider stopping. In order to monitor any symptoms of withdrawal or return of a condition, it would be best to stop one at a time and follow-up closely. Since she has done well for the past week without the glipizide and lisinopril-HCTZ combination, she can remain off the glipizide and the HCTZ. Lisinopril, however, may provide renal protection in the setting of diabetes and will be continued at this time.

You ask her about adverse effects from her other medications. She indicates that the furosemide makes her run to the bathroom all the time, so she would like to try stopping it. You agree and make a plan for her to monitor her weight, watch for edema, and return in 4 weeks for a follow-up visit.

On follow-up, she is feeling well, has no edema on exam, and is happy to report her urinary incontinence has resolved. You therefore suggest her next deprescribing trial be discontinuation of her oxybutynin. She thanks you for your recommendations about her medications and heads off to her physical therapy appointment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn McGrath, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care, Thomas Jefferson University, 2422 S Broad St, 2nd Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19145; Kathryn.mcgrath@jefferson.edu.

1. Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, et al. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:901-910.

2. Nair NP, Chalmers L, Peterson GM, et al. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions–the need for a prediction tool. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:497-506.

3. Nguyen JK, Fouts MM, Kotabe SE, et al. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006; 4:36-41.

4. Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colacone A, et al. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:666-671.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213-218.

7. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:173-186.

8. Magaziner J, Cadigan DA, Fedder DO, et al. Medication use and functional decline among community-dwelling older women. J Aging Health. 1989;1:470-484.

9. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57-65.

10. Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:588-595.

11. Weiss BD. Diagnostic evaluation of urinary incontinence in geriatric patients. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:2675-2694.

12. Syed Q, Hendler KT, Koncilja K. The impact of aging and medical status on dysgeusia. Am J Med. 2016;129:753, E1-E6.

13. Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:303-312.

14. Espino DV, Bazaldua OV, Palmer RF, et al. Suboptimal medication use and mortality in an older adult community-based cohort: results from the Hispanic EPESE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:170-175.

15. Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010; 8:146-160.

16. Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516-1523.

17. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

18. Flaherty JH, Perry HM 3rd, Lynchard GS, et al. Polypharmacy and hospitalization among older home care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:554-559.

19. Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1518-1523.

20. Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple chronic conditions chartbook. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014.

21. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1-E25.

22. Woodward M. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:323-328.

23. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1648-1654.

24. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, et al. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:583-623.

25. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201:386-389.

26. Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care. 2016;8:164-171.

27. Orwig D, Brandt N, Gruber-Baldini AL. Medication management assessment for older adults in the community. Gerontologist. 2006;46:661-668.

28. Anderson K, Jue SG, Madaras-Kelly KJ. Identifying patients at risk for medication mismanagement: using cognitive screens to predict a patient’s accuracy in filling a pillbox. Consult Pharm. 2008;23:459-472.

29. Lenaerts E, De Knijf F, Schoenmakers B. Appropriate prescribing for older people: a new tool for the general practitioner. J Frailty & Aging. 2013;2:8-14.

30. Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. IMAJ. 2007;9:430-434.

31. Holmes HM, Todd A. Evidence-based deprescribing of statins in patients with advanced illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:701-702.

32. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827-834.

33. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV,Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

34. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

35. Petersen LK, Christensen K, Kragstrup J. Lipid-lowering treatment to the end? A review of observational studies and RCTs on cholesterol and mortality in 80+-year olds. Age Ageing. 2010;39:674-680.

36. Banach M, Serban MC. Discussion around statin discontinuation in older adults and patients with wasting diseases. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:396-399.

37. Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. Statin therapy in the elderly: misconceptions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1365.

38. Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, et al, for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults. The ALLHAT-LLT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. Published online May 22, 2017.

39. Sever PS, Chang CL, Gupta AK, et al. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial: 11-year mortality follow-up of the lipid-lowering arm in the U.K. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2525-2532.

40. Denardo SJ, Gong Y, Nichols WW, et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med. 2010;123:719-726.

41. Ekbom T, Lindholm LH, Oden A, et al. A 5‐year prospective, observational study of the withdrawal of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people. J Intern Med. 1994;235:581-588.

42. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:1021-1031.

43. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home‐based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850-853.

44. Pollmann AS, Murphy AL, Bergman JC, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: a scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:19.

45. Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. Can Fam Phys. 2017; 63:354-364.

46. Duncan P, Duerden M, Payne RA. Deprescribing: a primary care perspective. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:37-42.

47. Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, et al. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56.

48. Scott I, Anderson K, Freeman CR, et al. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201:390-392.

CASE An 82-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, anxiety, urge urinary incontinence, constipation, and bilateral knee osteoarthritis presents to her primary care physician’s office after a fall. She reports that she visited the emergency department (ED) a week ago after falling in the middle of the night on her way to the bathroom. This is the third fall she’s had this year. On chart review, she had a blood pressure (BP) of 112/60 mm Hg and a blood glucose level of 65 mg/dL in the ED. All other testing (head imaging, chest x-ray, urinalysis) was normal. The ED physician recommended that she stop taking her lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and glipizide extended release (XL) until her follow-up appointment. Today, she asks about the need to restart these medications.

Polypharmacy is common among older adults due to a high prevalence of chronic conditions that often require multiple medications for optimal management. Cut points of 5 or 9 medications are frequently used to define polypharmacy. However, some define polypharmacy as taking a medication that lacks an indication, is ineffective, or is duplicating treatment provided by another medication.

Either way, polypharmacy is associated with multiple negative consequences, including an increased risk for adverse drug events (ADEs),1-4 drug-drug and drug-disease interactions (TABLE 15,6),7 reduced functional capacity,8 multiple geriatric syndromes (TABLE 25,9-12), medication non-adherence,13 and increased mortality.14 Polypharmacy also contributes to increased health care costs for both the patient and the health care system.15

Taking a step back. Polypharmacy often results from prescribing cascades, which occur when an adverse drug effect is misinterpreted as a new medical problem, leading to the prescribing of more medication to treat the initial drug-induced symptom. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), which are medications that should be avoided in older adults and in those with certain conditions, are also more likely to be prescribed in the setting of polypharmacy.16

Deprescribing is the process of identifying and discontinuing medications that are unnecessary, ineffective, and/or inappropriate in order to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. Deprescribing is a collaborative process that involves weighing the benefits and harms of medications in the context of a patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences. This article reviews polypharmacy and discusses safe and effective deprescribing strategies for older adults in the primary care setting.

[polldaddy:9781245]

How many people on how many meds?

According to a 2016 study, 36% of community-dwelling older adults (ages 62-85 years) were taking 5 or more prescription medications in 2010 to 2011—up from 31% in 2005 to 2006.17 When one narrows the population to older adults in the United States who are hospitalized, almost half (46%) take 7 or more medications.18 Among frail, older US veterans at hospital discharge, 40% were prescribed 9 or more medications, with 44% of these patients receiving at least one unnecessary drug.19

The challenges of multimorbidity

In the United States, 80% of those 65 and older have 2 or more chronic conditions, or multimorbidity.20 Clinical practice guidelines making recommendations for the management of single conditions, such as heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes, often suggest the use of 2 or more medications to achieve optimal management and fail to provide guidance in the setting of multimorbidity. Following treatment recommendations for multiple conditions predictably leads to polypharmacy, with complicated, costly, and burdensome regimens.

Further, the research contributing to the development of clinical practice guidelines frequently excludes older adults and those with multimorbidity, reducing applicability in this population. As a result, many treatment recommendations have uncertain benefit and may be harmful in the multimorbid older patient.21

CASE In addition to the patient’s multimorbidity, she had a stroke at age 73 and has some mild residual left-sided weakness. Functionally, she is independent and able to perform her activities of daily living and her instrumental activities of daily living. She lives alone, quit smoking at age 65, and has an occasional glass of wine during family parties. The patient’s daughter and granddaughter live 2 blocks away.

Her current medications include glipizide XL 10 mg/d and lisinopril-HCTZ 20-25 mg/d, which she has temporarily discontinued at the ED doctor’s recommendation, as well as: amlodipine 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg BID, senna 8.6 mg/d, docusate 100 mg BID, furosemide 40 mg/d, and ibuprofen 600 mg/d (for knee pain). She reports taking omeprazole 20 mg/d “for almost 20 years,” even though she has not had any reflux symptoms in recent memory. After her stroke, she began taking atorvastatin 10 mg/d, aspirin 81 mg/d, and clopidogrel 75 mg/d, which she continues to take today. About a year ago, she started oxybutynin 5 mg/d for urinary incontinence, but she has not noticed significant relief. Additionally, she takes lorazepam 1 mg for insomnia most nights of the week.

A review of systems reveals issues with chronic constipation and intermittent dizziness, but is otherwise negative. The physical examination reveals a well-appearing woman with a body mass index of 26. Her temperature is 98.5° F, her heart rate is 78 beats/min and regular, her respirations are 14 breaths/min, and her BP is 117/65 mm Hg. Orthostatic testing is negative. Her heart, lung, and abdominal exams are within normal limits. Her timed up and go test is 14 seconds. Her blood glucose level today in the office after eating breakfast 2 hours ago is 135 mg/dL (normal: <140 mg/dL). Laboratory tests performed at the time of the ED visit show a creatinine level of 1.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL), a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 44 units (normal range: >60 units), a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL (normal range: 12-15.5 g/dL), and a thyroid stimulating hormone level of 1.4 mIU/L (normal range: 0.5-8.9 mIU/L). A recent hemoglobin A1C is 6.8% (normal: <5.7%), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 103 mg/dL (optimal <100 mg/dL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level is 65 mg/dL (optimal >60 mg/dL). An echocardiogram performed a year ago showed mild aortic stenosis with normal systolic and diastolic function.

Starting the deprescribing process: Several approaches to choose from

The goal of deprescribing is to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. It is a process defined as, “reviewing all current medications; identifying medications to be ceased, substituted, or reduced; planning a deprescribing regimen in partnership with the patient; and frequently reviewing and supporting the patient.”22 A medication review should include prescription, over-the-counter (OTC), and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) agents.

Until recently, studies evaluating the process of deprescribing across drug classes and disease conditions were limited, but new research is beginning to show its potential impact. After deprescribing, patients experience fewer falls and show improvements in cognition.23 While there have not yet been large randomized trials to evaluate deprescribing, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that use of patient-specific deprescribing interventions is associated with improved survival.24 Importantly, there have been no reported adverse drug withdrawal events or deaths associated with deprescribing.23

Smaller studies have reported additional benefits including decreases in health care costs, reductions in drug-drug interactions and PIMs, improvements in medication adherence, and increases in patient satisfaction.25 In addition, the removal of unnecessary medications may allow for increased consideration of prescribing appropriate medications with known benefit.25

Practically speaking, every encounter between a patient and health care provider is an opportunity to reduce unnecessary medications. Electronic alert systems at pharmacies and those embedded within electronic health record (EHR) systems can also prompt a medication review and an effort to deprescribe.26 Evidence-based tools to identify polypharmacy and guide appropriate medication use are listed in TABLE 3.5,6,27-30 In addition, suggested approaches to beginning the deprescribing process are included in TABLE 4.5,31-33 And a medication class-based approach to deprescribing is provided in TABLE 5.5,34-45

Although no gold standard process exists for deprescribing, experts suggest that any deprescribing protocol should include the following steps:32,46

1. Start with a “brown bag” review of the patient’s medications.

Have the patient bring all of his/her medications in a bag to the visit; review them together or have the medication history taken by a pharmacist. Determine and discuss the indication for each medication and its effectiveness for that indication. Consider the potential benefits and harms of each medication in the context of the patient’s care goals and preferences. Assess whether the patient is taking all of the medications that have been prescribed, and identify any reasons for missed pills (eg, adverse effects, dosing regimens, understanding, cognitive issues).

2. Talk to the patient about the deprescribing process.

Talk with the patient about the risks and benefits of deprescribing, and prioritize which medications to address in the process. Prioritize the medications by balancing patient preferences with available pharmacologic evidence. If there is a lack of evidence supporting the benefits for a particular medication, consider known or suspected adverse effects, the ease or burden of the dosing regimen, the patient’s preferences and goals of care, remaining life expectancy, the time until drug benefit is appreciated, and the length of drug benefit after discontinuation.

3. Deprescribe medications.

If you are going to taper a medication, develop a schedule in partnership with the patient. Stop one medication at a time so that you can monitor for withdrawal symptoms or for the return of a condition.

Acknowledging potential barriers to deprescribing may help structure conversations and provide anticipatory guidance to patients and their families. Working to overcome these barriers will help maximize the benefits of deprescribing and help to build trust with patients.

Patient-driven barriers include fear of a condition worsening or returning, lack of a suitable alternative, lack of ongoing support to manage a particular condition, a previous bad experience with medication cessation, and influence from other care providers (eg, family, home caregivers, nurses, specialists, friends). Patients and family members sometimes cling to the hope of future effectiveness of a treatment, especially in the case of medications like donepezil for dementia.47 Utilizing a team-based and stepwise patient approach to deprescribing aims to provide hesitant patients with appropriate amounts of education and support to begin to reduce unnecessary medicines.

Provider-driven barriers include feeling uneasy about contradicting a specialist’s recommendations for initiation/continuation of specific medications, fear of causing withdrawal symptoms or disease relapse, and lack of specific data to adequately understand and assess benefits and harms in the older adult population. Primary care physicians have also acknowledged worry about discussing life expectancy and that patients will feel their care is being reduced or “downgraded.”48 Finally, there is limited time in which these complex shared decision-making conversations can take place. Thus, if medications are not causing a noticeable problem, it is often easier to just continue them.

One way to overcome some of these concerns is to consider working with a clinical pharmacist. By gaining information regarding medication-specific factors, such as half-life and expected withdrawal patterns, you can feel more confident deprescribing or continuing medications.

Additionally, communicating closely with specialists, ideally with the help of an integrated EHR, can allow you to discuss indications for particular medications or concerns about adverse effects, limited benefits, or difficulty with compliance, so that you can develop a collaborative, cohesive, and patient-centered plan. This, in turn, may improve patient understanding and compliance.

4. Create a follow-up plan.

At the time of deprescribing a medication, develop a plan with the patient for monitoring and assessment. Ensure that the patient understands which symptoms may occur in the event of drug withdrawal and which symptoms may suggest the return of a condition. Make sure that other supports are in place if needed (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, physical therapy, social support or assistance) to help ensure that medication cessation is successful.

CASE During the office visit, you advise the patient that her BP looks normal, her blood sugar is within an appropriate range, and she is lucky to have not sustained any injuries after her most recent fall. In addition to discussing the benefits of some outpatient physical therapy to help with her balance, you ask if she would like to discuss reducing her medications. She is agreeable and asks for your recommendations.

You are aware of several resources that can help you with your recommendations, among them the STOPP/START6 and Beers criteria,5 as well as the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm.30

If you were to use the STOPP/START and Beers criteria, you might consider stopping:

- lorazepam, which increases the risk of falls and confusion.

- ibuprofen, since this patient has only mild osteoarthritis pain, and ibuprofen has the potential for renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal toxicities.

- oxybutynin, because it could be contributing to the patient’s constipation and cause confusion and falls.

- furosemide, since the patient has no clinical heart failure.

- omeprazole, since the indication is unknown and the patient has no history of ulceration, esophagitis, or symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease.

After reviewing the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm,30 you might consider stopping:

- clopidogrel, as there is no clear indication for this medication in combination with aspirin in this patient.

- glipizide XL, as this patient’s A1c is below goal and this medication puts her at risk of hypoglycemia and its associated morbidities.

- metformin, as it increases her risk of lactic acidosis because her GFR is <45 units.

- docusate, as the evidence to show clear benefit in improving chronic constipation in older adults is lacking.

You tell your patient that there are multiple medications to consider stopping. In order to monitor any symptoms of withdrawal or return of a condition, it would be best to stop one at a time and follow-up closely. Since she has done well for the past week without the glipizide and lisinopril-HCTZ combination, she can remain off the glipizide and the HCTZ. Lisinopril, however, may provide renal protection in the setting of diabetes and will be continued at this time.

You ask her about adverse effects from her other medications. She indicates that the furosemide makes her run to the bathroom all the time, so she would like to try stopping it. You agree and make a plan for her to monitor her weight, watch for edema, and return in 4 weeks for a follow-up visit.

On follow-up, she is feeling well, has no edema on exam, and is happy to report her urinary incontinence has resolved. You therefore suggest her next deprescribing trial be discontinuation of her oxybutynin. She thanks you for your recommendations about her medications and heads off to her physical therapy appointment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn McGrath, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care, Thomas Jefferson University, 2422 S Broad St, 2nd Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19145; Kathryn.mcgrath@jefferson.edu.

CASE An 82-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, anxiety, urge urinary incontinence, constipation, and bilateral knee osteoarthritis presents to her primary care physician’s office after a fall. She reports that she visited the emergency department (ED) a week ago after falling in the middle of the night on her way to the bathroom. This is the third fall she’s had this year. On chart review, she had a blood pressure (BP) of 112/60 mm Hg and a blood glucose level of 65 mg/dL in the ED. All other testing (head imaging, chest x-ray, urinalysis) was normal. The ED physician recommended that she stop taking her lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and glipizide extended release (XL) until her follow-up appointment. Today, she asks about the need to restart these medications.

Polypharmacy is common among older adults due to a high prevalence of chronic conditions that often require multiple medications for optimal management. Cut points of 5 or 9 medications are frequently used to define polypharmacy. However, some define polypharmacy as taking a medication that lacks an indication, is ineffective, or is duplicating treatment provided by another medication.

Either way, polypharmacy is associated with multiple negative consequences, including an increased risk for adverse drug events (ADEs),1-4 drug-drug and drug-disease interactions (TABLE 15,6),7 reduced functional capacity,8 multiple geriatric syndromes (TABLE 25,9-12), medication non-adherence,13 and increased mortality.14 Polypharmacy also contributes to increased health care costs for both the patient and the health care system.15

Taking a step back. Polypharmacy often results from prescribing cascades, which occur when an adverse drug effect is misinterpreted as a new medical problem, leading to the prescribing of more medication to treat the initial drug-induced symptom. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), which are medications that should be avoided in older adults and in those with certain conditions, are also more likely to be prescribed in the setting of polypharmacy.16

Deprescribing is the process of identifying and discontinuing medications that are unnecessary, ineffective, and/or inappropriate in order to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. Deprescribing is a collaborative process that involves weighing the benefits and harms of medications in the context of a patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences. This article reviews polypharmacy and discusses safe and effective deprescribing strategies for older adults in the primary care setting.

[polldaddy:9781245]

How many people on how many meds?

According to a 2016 study, 36% of community-dwelling older adults (ages 62-85 years) were taking 5 or more prescription medications in 2010 to 2011—up from 31% in 2005 to 2006.17 When one narrows the population to older adults in the United States who are hospitalized, almost half (46%) take 7 or more medications.18 Among frail, older US veterans at hospital discharge, 40% were prescribed 9 or more medications, with 44% of these patients receiving at least one unnecessary drug.19

The challenges of multimorbidity

In the United States, 80% of those 65 and older have 2 or more chronic conditions, or multimorbidity.20 Clinical practice guidelines making recommendations for the management of single conditions, such as heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes, often suggest the use of 2 or more medications to achieve optimal management and fail to provide guidance in the setting of multimorbidity. Following treatment recommendations for multiple conditions predictably leads to polypharmacy, with complicated, costly, and burdensome regimens.

Further, the research contributing to the development of clinical practice guidelines frequently excludes older adults and those with multimorbidity, reducing applicability in this population. As a result, many treatment recommendations have uncertain benefit and may be harmful in the multimorbid older patient.21

CASE In addition to the patient’s multimorbidity, she had a stroke at age 73 and has some mild residual left-sided weakness. Functionally, she is independent and able to perform her activities of daily living and her instrumental activities of daily living. She lives alone, quit smoking at age 65, and has an occasional glass of wine during family parties. The patient’s daughter and granddaughter live 2 blocks away.

Her current medications include glipizide XL 10 mg/d and lisinopril-HCTZ 20-25 mg/d, which she has temporarily discontinued at the ED doctor’s recommendation, as well as: amlodipine 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg BID, senna 8.6 mg/d, docusate 100 mg BID, furosemide 40 mg/d, and ibuprofen 600 mg/d (for knee pain). She reports taking omeprazole 20 mg/d “for almost 20 years,” even though she has not had any reflux symptoms in recent memory. After her stroke, she began taking atorvastatin 10 mg/d, aspirin 81 mg/d, and clopidogrel 75 mg/d, which she continues to take today. About a year ago, she started oxybutynin 5 mg/d for urinary incontinence, but she has not noticed significant relief. Additionally, she takes lorazepam 1 mg for insomnia most nights of the week.

A review of systems reveals issues with chronic constipation and intermittent dizziness, but is otherwise negative. The physical examination reveals a well-appearing woman with a body mass index of 26. Her temperature is 98.5° F, her heart rate is 78 beats/min and regular, her respirations are 14 breaths/min, and her BP is 117/65 mm Hg. Orthostatic testing is negative. Her heart, lung, and abdominal exams are within normal limits. Her timed up and go test is 14 seconds. Her blood glucose level today in the office after eating breakfast 2 hours ago is 135 mg/dL (normal: <140 mg/dL). Laboratory tests performed at the time of the ED visit show a creatinine level of 1.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL), a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 44 units (normal range: >60 units), a hemoglobin level of 9.8 g/dL (normal range: 12-15.5 g/dL), and a thyroid stimulating hormone level of 1.4 mIU/L (normal range: 0.5-8.9 mIU/L). A recent hemoglobin A1C is 6.8% (normal: <5.7%), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 103 mg/dL (optimal <100 mg/dL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level is 65 mg/dL (optimal >60 mg/dL). An echocardiogram performed a year ago showed mild aortic stenosis with normal systolic and diastolic function.

Starting the deprescribing process: Several approaches to choose from

The goal of deprescribing is to reduce polypharmacy and improve health outcomes. It is a process defined as, “reviewing all current medications; identifying medications to be ceased, substituted, or reduced; planning a deprescribing regimen in partnership with the patient; and frequently reviewing and supporting the patient.”22 A medication review should include prescription, over-the-counter (OTC), and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) agents.

Until recently, studies evaluating the process of deprescribing across drug classes and disease conditions were limited, but new research is beginning to show its potential impact. After deprescribing, patients experience fewer falls and show improvements in cognition.23 While there have not yet been large randomized trials to evaluate deprescribing, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that use of patient-specific deprescribing interventions is associated with improved survival.24 Importantly, there have been no reported adverse drug withdrawal events or deaths associated with deprescribing.23

Smaller studies have reported additional benefits including decreases in health care costs, reductions in drug-drug interactions and PIMs, improvements in medication adherence, and increases in patient satisfaction.25 In addition, the removal of unnecessary medications may allow for increased consideration of prescribing appropriate medications with known benefit.25

Practically speaking, every encounter between a patient and health care provider is an opportunity to reduce unnecessary medications. Electronic alert systems at pharmacies and those embedded within electronic health record (EHR) systems can also prompt a medication review and an effort to deprescribe.26 Evidence-based tools to identify polypharmacy and guide appropriate medication use are listed in TABLE 3.5,6,27-30 In addition, suggested approaches to beginning the deprescribing process are included in TABLE 4.5,31-33 And a medication class-based approach to deprescribing is provided in TABLE 5.5,34-45

Although no gold standard process exists for deprescribing, experts suggest that any deprescribing protocol should include the following steps:32,46

1. Start with a “brown bag” review of the patient’s medications.

Have the patient bring all of his/her medications in a bag to the visit; review them together or have the medication history taken by a pharmacist. Determine and discuss the indication for each medication and its effectiveness for that indication. Consider the potential benefits and harms of each medication in the context of the patient’s care goals and preferences. Assess whether the patient is taking all of the medications that have been prescribed, and identify any reasons for missed pills (eg, adverse effects, dosing regimens, understanding, cognitive issues).

2. Talk to the patient about the deprescribing process.

Talk with the patient about the risks and benefits of deprescribing, and prioritize which medications to address in the process. Prioritize the medications by balancing patient preferences with available pharmacologic evidence. If there is a lack of evidence supporting the benefits for a particular medication, consider known or suspected adverse effects, the ease or burden of the dosing regimen, the patient’s preferences and goals of care, remaining life expectancy, the time until drug benefit is appreciated, and the length of drug benefit after discontinuation.

3. Deprescribe medications.

If you are going to taper a medication, develop a schedule in partnership with the patient. Stop one medication at a time so that you can monitor for withdrawal symptoms or for the return of a condition.

Acknowledging potential barriers to deprescribing may help structure conversations and provide anticipatory guidance to patients and their families. Working to overcome these barriers will help maximize the benefits of deprescribing and help to build trust with patients.

Patient-driven barriers include fear of a condition worsening or returning, lack of a suitable alternative, lack of ongoing support to manage a particular condition, a previous bad experience with medication cessation, and influence from other care providers (eg, family, home caregivers, nurses, specialists, friends). Patients and family members sometimes cling to the hope of future effectiveness of a treatment, especially in the case of medications like donepezil for dementia.47 Utilizing a team-based and stepwise patient approach to deprescribing aims to provide hesitant patients with appropriate amounts of education and support to begin to reduce unnecessary medicines.

Provider-driven barriers include feeling uneasy about contradicting a specialist’s recommendations for initiation/continuation of specific medications, fear of causing withdrawal symptoms or disease relapse, and lack of specific data to adequately understand and assess benefits and harms in the older adult population. Primary care physicians have also acknowledged worry about discussing life expectancy and that patients will feel their care is being reduced or “downgraded.”48 Finally, there is limited time in which these complex shared decision-making conversations can take place. Thus, if medications are not causing a noticeable problem, it is often easier to just continue them.

One way to overcome some of these concerns is to consider working with a clinical pharmacist. By gaining information regarding medication-specific factors, such as half-life and expected withdrawal patterns, you can feel more confident deprescribing or continuing medications.

Additionally, communicating closely with specialists, ideally with the help of an integrated EHR, can allow you to discuss indications for particular medications or concerns about adverse effects, limited benefits, or difficulty with compliance, so that you can develop a collaborative, cohesive, and patient-centered plan. This, in turn, may improve patient understanding and compliance.

4. Create a follow-up plan.

At the time of deprescribing a medication, develop a plan with the patient for monitoring and assessment. Ensure that the patient understands which symptoms may occur in the event of drug withdrawal and which symptoms may suggest the return of a condition. Make sure that other supports are in place if needed (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, physical therapy, social support or assistance) to help ensure that medication cessation is successful.

CASE During the office visit, you advise the patient that her BP looks normal, her blood sugar is within an appropriate range, and she is lucky to have not sustained any injuries after her most recent fall. In addition to discussing the benefits of some outpatient physical therapy to help with her balance, you ask if she would like to discuss reducing her medications. She is agreeable and asks for your recommendations.

You are aware of several resources that can help you with your recommendations, among them the STOPP/START6 and Beers criteria,5 as well as the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm.30

If you were to use the STOPP/START and Beers criteria, you might consider stopping:

- lorazepam, which increases the risk of falls and confusion.

- ibuprofen, since this patient has only mild osteoarthritis pain, and ibuprofen has the potential for renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal toxicities.

- oxybutynin, because it could be contributing to the patient’s constipation and cause confusion and falls.

- furosemide, since the patient has no clinical heart failure.

- omeprazole, since the indication is unknown and the patient has no history of ulceration, esophagitis, or symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease.

After reviewing the Good Geriatric-Palliative Algorithm,30 you might consider stopping:

- clopidogrel, as there is no clear indication for this medication in combination with aspirin in this patient.

- glipizide XL, as this patient’s A1c is below goal and this medication puts her at risk of hypoglycemia and its associated morbidities.

- metformin, as it increases her risk of lactic acidosis because her GFR is <45 units.

- docusate, as the evidence to show clear benefit in improving chronic constipation in older adults is lacking.

You tell your patient that there are multiple medications to consider stopping. In order to monitor any symptoms of withdrawal or return of a condition, it would be best to stop one at a time and follow-up closely. Since she has done well for the past week without the glipizide and lisinopril-HCTZ combination, she can remain off the glipizide and the HCTZ. Lisinopril, however, may provide renal protection in the setting of diabetes and will be continued at this time.

You ask her about adverse effects from her other medications. She indicates that the furosemide makes her run to the bathroom all the time, so she would like to try stopping it. You agree and make a plan for her to monitor her weight, watch for edema, and return in 4 weeks for a follow-up visit.

On follow-up, she is feeling well, has no edema on exam, and is happy to report her urinary incontinence has resolved. You therefore suggest her next deprescribing trial be discontinuation of her oxybutynin. She thanks you for your recommendations about her medications and heads off to her physical therapy appointment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn McGrath, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care, Thomas Jefferson University, 2422 S Broad St, 2nd Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19145; Kathryn.mcgrath@jefferson.edu.

1. Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, et al. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:901-910.

2. Nair NP, Chalmers L, Peterson GM, et al. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions–the need for a prediction tool. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:497-506.

3. Nguyen JK, Fouts MM, Kotabe SE, et al. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006; 4:36-41.

4. Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colacone A, et al. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:666-671.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213-218.

7. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:173-186.

8. Magaziner J, Cadigan DA, Fedder DO, et al. Medication use and functional decline among community-dwelling older women. J Aging Health. 1989;1:470-484.

9. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57-65.

10. Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:588-595.

11. Weiss BD. Diagnostic evaluation of urinary incontinence in geriatric patients. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:2675-2694.

12. Syed Q, Hendler KT, Koncilja K. The impact of aging and medical status on dysgeusia. Am J Med. 2016;129:753, E1-E6.

13. Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:303-312.

14. Espino DV, Bazaldua OV, Palmer RF, et al. Suboptimal medication use and mortality in an older adult community-based cohort: results from the Hispanic EPESE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:170-175.

15. Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010; 8:146-160.

16. Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516-1523.

17. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

18. Flaherty JH, Perry HM 3rd, Lynchard GS, et al. Polypharmacy and hospitalization among older home care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:554-559.

19. Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1518-1523.

20. Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple chronic conditions chartbook. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014.

21. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1-E25.

22. Woodward M. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:323-328.

23. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1648-1654.

24. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, et al. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:583-623.

25. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201:386-389.

26. Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care. 2016;8:164-171.

27. Orwig D, Brandt N, Gruber-Baldini AL. Medication management assessment for older adults in the community. Gerontologist. 2006;46:661-668.

28. Anderson K, Jue SG, Madaras-Kelly KJ. Identifying patients at risk for medication mismanagement: using cognitive screens to predict a patient’s accuracy in filling a pillbox. Consult Pharm. 2008;23:459-472.

29. Lenaerts E, De Knijf F, Schoenmakers B. Appropriate prescribing for older people: a new tool for the general practitioner. J Frailty & Aging. 2013;2:8-14.

30. Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. IMAJ. 2007;9:430-434.

31. Holmes HM, Todd A. Evidence-based deprescribing of statins in patients with advanced illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:701-702.

32. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827-834.

33. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV,Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

34. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

35. Petersen LK, Christensen K, Kragstrup J. Lipid-lowering treatment to the end? A review of observational studies and RCTs on cholesterol and mortality in 80+-year olds. Age Ageing. 2010;39:674-680.

36. Banach M, Serban MC. Discussion around statin discontinuation in older adults and patients with wasting diseases. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:396-399.

37. Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. Statin therapy in the elderly: misconceptions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1365.

38. Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, et al, for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults. The ALLHAT-LLT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. Published online May 22, 2017.

39. Sever PS, Chang CL, Gupta AK, et al. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial: 11-year mortality follow-up of the lipid-lowering arm in the U.K. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2525-2532.

40. Denardo SJ, Gong Y, Nichols WW, et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med. 2010;123:719-726.

41. Ekbom T, Lindholm LH, Oden A, et al. A 5‐year prospective, observational study of the withdrawal of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people. J Intern Med. 1994;235:581-588.

42. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:1021-1031.

43. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home‐based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850-853.

44. Pollmann AS, Murphy AL, Bergman JC, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: a scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:19.

45. Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. Can Fam Phys. 2017; 63:354-364.

46. Duncan P, Duerden M, Payne RA. Deprescribing: a primary care perspective. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:37-42.

47. Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, et al. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56.

48. Scott I, Anderson K, Freeman CR, et al. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201:390-392.

1. Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, et al. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:901-910.

2. Nair NP, Chalmers L, Peterson GM, et al. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions–the need for a prediction tool. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:497-506.

3. Nguyen JK, Fouts MM, Kotabe SE, et al. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006; 4:36-41.

4. Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colacone A, et al. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:666-671.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213-218.

7. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:173-186.

8. Magaziner J, Cadigan DA, Fedder DO, et al. Medication use and functional decline among community-dwelling older women. J Aging Health. 1989;1:470-484.

9. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57-65.

10. Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:588-595.

11. Weiss BD. Diagnostic evaluation of urinary incontinence in geriatric patients. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:2675-2694.

12. Syed Q, Hendler KT, Koncilja K. The impact of aging and medical status on dysgeusia. Am J Med. 2016;129:753, E1-E6.

13. Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:303-312.

14. Espino DV, Bazaldua OV, Palmer RF, et al. Suboptimal medication use and mortality in an older adult community-based cohort: results from the Hispanic EPESE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:170-175.

15. Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010; 8:146-160.

16. Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516-1523.

17. Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:473-482.

18. Flaherty JH, Perry HM 3rd, Lynchard GS, et al. Polypharmacy and hospitalization among older home care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:554-559.

19. Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1518-1523.

20. Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple chronic conditions chartbook. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014.

21. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1-E25.

22. Woodward M. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:323-328.

23. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1648-1654.

24. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, et al. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:583-623.

25. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201:386-389.

26. Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care. 2016;8:164-171.

27. Orwig D, Brandt N, Gruber-Baldini AL. Medication management assessment for older adults in the community. Gerontologist. 2006;46:661-668.

28. Anderson K, Jue SG, Madaras-Kelly KJ. Identifying patients at risk for medication mismanagement: using cognitive screens to predict a patient’s accuracy in filling a pillbox. Consult Pharm. 2008;23:459-472.

29. Lenaerts E, De Knijf F, Schoenmakers B. Appropriate prescribing for older people: a new tool for the general practitioner. J Frailty & Aging. 2013;2:8-14.

30. Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. IMAJ. 2007;9:430-434.

31. Holmes HM, Todd A. Evidence-based deprescribing of statins in patients with advanced illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:701-702.

32. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827-834.

33. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV,Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

34. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726.

35. Petersen LK, Christensen K, Kragstrup J. Lipid-lowering treatment to the end? A review of observational studies and RCTs on cholesterol and mortality in 80+-year olds. Age Ageing. 2010;39:674-680.

36. Banach M, Serban MC. Discussion around statin discontinuation in older adults and patients with wasting diseases. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:396-399.

37. Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. Statin therapy in the elderly: misconceptions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1365.

38. Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, et al, for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults. The ALLHAT-LLT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. Published online May 22, 2017.

39. Sever PS, Chang CL, Gupta AK, et al. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial: 11-year mortality follow-up of the lipid-lowering arm in the U.K. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2525-2532.

40. Denardo SJ, Gong Y, Nichols WW, et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med. 2010;123:719-726.

41. Ekbom T, Lindholm LH, Oden A, et al. A 5‐year prospective, observational study of the withdrawal of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people. J Intern Med. 1994;235:581-588.

42. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:1021-1031.

43. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home‐based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850-853.

44. Pollmann AS, Murphy AL, Bergman JC, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: a scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:19.

45. Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. Can Fam Phys. 2017; 63:354-364.

46. Duncan P, Duerden M, Payne RA. Deprescribing: a primary care perspective. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:37-42.

47. Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, et al. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56.

48. Scott I, Anderson K, Freeman CR, et al. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201:390-392.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2017;66(7):436-445.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Avoid medications that are inappropriate for older adults because of adverse effects, lack of efficacy, and/or potential for interactions. A

› Discontinue medications when the harms outweigh the benefits in the context of the patient’s care goals, life expectancy, and/or preferences. C

› Utilize resources such as the STOPP/START and Beers criteria to help you decide where to begin the deprescribing process. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Strategies to help reduce hospital readmissions

› Use risk stratification methods such as the Probability of Repeated Admission (Pra) or the LACE index to identify patients at high risk for readmission. B

› Take steps to ensure that follow-up appointments are made within the first one to 2 weeks of discharge, depending on the patient’s risk of readmission. C

› Reconcile preadmission and postdischarge medications to identify discrepancies and possible interactions. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Charles T, age 74, has a 3-year history of myocardial infarction (MI) and congestive heart failure (CHF) and a 10-year his-tory of type 2 diabetes with retinopathy. You have cared for him in the outpatient setting for 8 years. You are notified that he is in the emergency department (ED) and being admitted to the hospital, again. This is his third ED visit in the past 3 months; he was hospitalized for 6 days during his last admission 3 weeks ago.

What should you do with this information? How can you best communicate with the admitting team?

Hospital readmissions are widespread, costly, and often avoidable. Nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries discharged from hospitals are rehospitalized within 30 days, and 34% are rehospitalized within 90 days.1 For patients with conditions like CHF, the rate of readmission within 30 days approaches 25%.2 The estimated cost to Medicare for unplanned rehospitalizations in 2004 was $17.4 billion.1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services penalizes hospitals for high rates of readmission within 30 days of discharge for patients with CHF, MI, and pneumonia.

“Avoidable” hospitalizations are those that may be prevented by effective outpatient management and improved care coordination. Although efforts to reduce readmissions have focused on improving the discharge process, family physicians (FPs) can play a central role in reducing readmissions. This article describes key approaches that FPs can take to address this important issue. Because patients ages ≥65 years consistently have the highest rate of hospital readmissions,1 we will focus on this population.

Multiple complex factors are associated with hospital readmissions

Characteristics of the patient, physician, and health care setting contribute to potentially avoidable readmissions (TABLE 1).3,4

Medical conditions and comorbidities associated with high rates of rehospitalization include CHF, acute MI, pneumonia, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. However, a recent study found that a diverse range of conditions, frequently differing from the index cause of hospitalization, were responsible for 30-day readmissions of Medicare patients.5

Identifying those at high risk: Why and how

Determining which patients are at highest risk for readmission enables health care teams to match the intensity of interventions to the individual’s likelihood of readmission. However, current readmission risk prediction models remain a work in progress6 and few models have been tested in the outpatient setting. Despite numerous limitations, it’s still important to focus resources more efficiently. Thus, we recommend using risk stratification tools to identify patients at high risk for readmission.

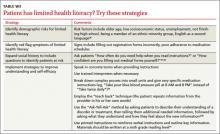

Many risk stratification methods use data from electronic medical records (EMRs) and administrative databases or self-reported data from patients.7 Risk prediction tools that are relatively simple and easy to administer or generate through EMRs—such as the Probability of Repeated Admission (Pra),8 the LACE (Length of stay, acuity of the admission, comorbidities, ED visits in the previous 6 months) index,9 or the Community Assessment Risk Screen (CARS)10—may be best for use in the primary care setting. These tools generally identify key risk factors, such as prior health care utilization, presence of specific conditions such as heart disease or cognitive impairment, self-reported health status, absence of a caregiver, and/or need for assistance with daily routines.