User login

Naltrexone cuts hospitalization, deaths in alcohol use disorder

Naltrexone reduces the risk for hospitalization for alcohol use disorder (AUD), regardless of whether it is used alone or in conjunction with disulfiram or acamprosate, research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 10-year data on more than 125,000 Swedish residents with AUD and found that naltrexone, used as monotherapy or combined with acamprosate or disulfiram, was associated with significantly lower risk for AUD hospitalization or all-cause hospitalization in comparison with patients who did not use AUD medication. The patients ranged in age from 16 to 64 years.

By contrast, benzodiazepines and acamprosate monotherapy were associated with increased risk for AUD hospitalization.

“The take-home message for practicing clinicians would be that especially naltrexone use is associated with favorable treatment outcomes and should be utilized as part of the treatment protocol for AUD,” study investigator Milja Heikkinen, MD, specialist in forensic psychiatry and addiction medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, told this news organization.

On the other hand, “benzodiazepines should be avoided and should not be administered other than for alcohol withdrawal symptoms,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 4 in Addiction.

Real-world data

Previous research has shown that disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone, and nalmefene are efficacious in treating AUD, but most studies have been randomized controlled trials or meta-analyses, the authors write.

“Very little is known about overall health outcomes (such as risks of hospitalization and mortality) associated with specific treatments in real-world circumstances,” they write.

“The study was motivated by the fact that, although AUD is a significant public health concern, very little is known, especially about the comparative effectiveness of medications indicated in AUD,” said Dr. Heikkinen.

who had been diagnosed with AUD (62.5% men; mean [standard deviation] age, 38.1 [15.9] years). They followed the cohort over a median of 4.6 years (interquartile range, 2.1-.2 years).

During the follow-up period, roughly one-fourth of patients (25.6) underwent treatment with one or more drugs.

The main outcome measure was AUD-related hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were hospitalization for any cause and for alcohol-related somatic causes; all-cause mortality; and work disability.

Two types of analyses were conducted. The within-individual analyses, designed to eliminate selection bias, compared the use of a medication to periods during which the same individual was not using the medication.

Between-individual analyses (adjusted for sex, age, educational level, number of previous AUD-related hospitalizations, time since first AUD diagnosis, comorbidities, and use of other medications) utilized a “traditional” multivariate-adjusted Cox hazards regression model.

AUD pharmacotherapy ‘underutilized’

Close to one-fourth of patients (23.9%) experienced the main outcome event (AUD-related hospitalization) during the follow-up period.

The within-individual analysis showed that naltrexone – whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively with disulfiram or acamprosate – “was associated with a significantly lower risk of AUD-related hospitalization, compared to those time periods in which the same individual did not use any AUD medication,” the authors report.

By contrast, they state, acamprosate monotherapy and benzodiazepines were associated with a significantly higher risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

Similar results were obtained in the between-individual analysis. Longer duration of naltrexone use was associated with lower risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

The pattern was also found when the outcome was hospitalization for any cause. However, unlike the findings of the within-individual model, the second model found that acamprosate monotherapy was not associated with a higher risk for any-cause hospitalization.

Polytherapy, including combinations of the four AUD medications, as well as disulfiram monotherapy were similarly associated with lower risk for hospitalization for alcohol-related somatic causes.

Of the overall cohort, 6.2% died during the follow-up period. No association was found between disulfiram, acamprosate, nalmefene, and naltrexone use and all-cause mortality. By contrast, benzodiazepine use was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate (hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.19).

“AUD drugs are underutilized, despite AUD being a significant public health concern,” Dr. Heikkinen noted. On the other hand, benzodiazepine use is “very common.”

‘Ravages’ of benzodiazepines

Commenting on the study in an interview, John Krystal, MD, professor and chair of psychiatry and director of the Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said, “The main message from the study for practicing clinicians is that treatment works.”

Dr. Krystal, who was not involved with the study, noted that “many practicing clinicians are discouraged by the course of their patients with AUD, and this study highlights that naltrexone, perhaps in combination with other medications, may be effective in preventing hospitalization and, presumably, other hospitalization-related complications of AUD.”

Also commenting on the study, Raymond Anton, MD, professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, suggested that the “clinical knowledge of the harm of benzodiazepines in those with AUD is reinforced by these findings.”

In fact, the harm of benzodiazepines might be the study’s “most important message ... [a message that was] recently highlighted by the Netflix series “The Queen’s Gambit”, which shows the ravages of using both together, or how one leads to potential addiction with the other,” said Dr. Anton, who was not involved with the study.

The other “big take-home message is that naltrexone should be used more frequently,” said Dr. Anton, distinguished professor of psychiatry at the university and scientific director of the Charleston Alcohol Research Center. He noted that there are “recent data suggesting some clinical and genetic indicators that predict responsiveness to these medications, improving efficacy.”

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Dr. Heikkinen reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. Krystal consults for companies currently developing other treatments for AUDs and receives medications to test from AstraZeneca and Novartis for NIAAA-funded research programs. Dr. Anton has consulted for Alkermes, Lipha, and Lundbeck in the past. He is also chair of the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which is a public-private partnership partially sponsored by several companies and has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to study pharmacotherapies, including naltrexone, nalmefene, and acamprosate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Naltrexone reduces the risk for hospitalization for alcohol use disorder (AUD), regardless of whether it is used alone or in conjunction with disulfiram or acamprosate, research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 10-year data on more than 125,000 Swedish residents with AUD and found that naltrexone, used as monotherapy or combined with acamprosate or disulfiram, was associated with significantly lower risk for AUD hospitalization or all-cause hospitalization in comparison with patients who did not use AUD medication. The patients ranged in age from 16 to 64 years.

By contrast, benzodiazepines and acamprosate monotherapy were associated with increased risk for AUD hospitalization.

“The take-home message for practicing clinicians would be that especially naltrexone use is associated with favorable treatment outcomes and should be utilized as part of the treatment protocol for AUD,” study investigator Milja Heikkinen, MD, specialist in forensic psychiatry and addiction medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, told this news organization.

On the other hand, “benzodiazepines should be avoided and should not be administered other than for alcohol withdrawal symptoms,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 4 in Addiction.

Real-world data

Previous research has shown that disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone, and nalmefene are efficacious in treating AUD, but most studies have been randomized controlled trials or meta-analyses, the authors write.

“Very little is known about overall health outcomes (such as risks of hospitalization and mortality) associated with specific treatments in real-world circumstances,” they write.

“The study was motivated by the fact that, although AUD is a significant public health concern, very little is known, especially about the comparative effectiveness of medications indicated in AUD,” said Dr. Heikkinen.

who had been diagnosed with AUD (62.5% men; mean [standard deviation] age, 38.1 [15.9] years). They followed the cohort over a median of 4.6 years (interquartile range, 2.1-.2 years).

During the follow-up period, roughly one-fourth of patients (25.6) underwent treatment with one or more drugs.

The main outcome measure was AUD-related hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were hospitalization for any cause and for alcohol-related somatic causes; all-cause mortality; and work disability.

Two types of analyses were conducted. The within-individual analyses, designed to eliminate selection bias, compared the use of a medication to periods during which the same individual was not using the medication.

Between-individual analyses (adjusted for sex, age, educational level, number of previous AUD-related hospitalizations, time since first AUD diagnosis, comorbidities, and use of other medications) utilized a “traditional” multivariate-adjusted Cox hazards regression model.

AUD pharmacotherapy ‘underutilized’

Close to one-fourth of patients (23.9%) experienced the main outcome event (AUD-related hospitalization) during the follow-up period.

The within-individual analysis showed that naltrexone – whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively with disulfiram or acamprosate – “was associated with a significantly lower risk of AUD-related hospitalization, compared to those time periods in which the same individual did not use any AUD medication,” the authors report.

By contrast, they state, acamprosate monotherapy and benzodiazepines were associated with a significantly higher risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

Similar results were obtained in the between-individual analysis. Longer duration of naltrexone use was associated with lower risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

The pattern was also found when the outcome was hospitalization for any cause. However, unlike the findings of the within-individual model, the second model found that acamprosate monotherapy was not associated with a higher risk for any-cause hospitalization.

Polytherapy, including combinations of the four AUD medications, as well as disulfiram monotherapy were similarly associated with lower risk for hospitalization for alcohol-related somatic causes.

Of the overall cohort, 6.2% died during the follow-up period. No association was found between disulfiram, acamprosate, nalmefene, and naltrexone use and all-cause mortality. By contrast, benzodiazepine use was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate (hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.19).

“AUD drugs are underutilized, despite AUD being a significant public health concern,” Dr. Heikkinen noted. On the other hand, benzodiazepine use is “very common.”

‘Ravages’ of benzodiazepines

Commenting on the study in an interview, John Krystal, MD, professor and chair of psychiatry and director of the Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said, “The main message from the study for practicing clinicians is that treatment works.”

Dr. Krystal, who was not involved with the study, noted that “many practicing clinicians are discouraged by the course of their patients with AUD, and this study highlights that naltrexone, perhaps in combination with other medications, may be effective in preventing hospitalization and, presumably, other hospitalization-related complications of AUD.”

Also commenting on the study, Raymond Anton, MD, professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, suggested that the “clinical knowledge of the harm of benzodiazepines in those with AUD is reinforced by these findings.”

In fact, the harm of benzodiazepines might be the study’s “most important message ... [a message that was] recently highlighted by the Netflix series “The Queen’s Gambit”, which shows the ravages of using both together, or how one leads to potential addiction with the other,” said Dr. Anton, who was not involved with the study.

The other “big take-home message is that naltrexone should be used more frequently,” said Dr. Anton, distinguished professor of psychiatry at the university and scientific director of the Charleston Alcohol Research Center. He noted that there are “recent data suggesting some clinical and genetic indicators that predict responsiveness to these medications, improving efficacy.”

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Dr. Heikkinen reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. Krystal consults for companies currently developing other treatments for AUDs and receives medications to test from AstraZeneca and Novartis for NIAAA-funded research programs. Dr. Anton has consulted for Alkermes, Lipha, and Lundbeck in the past. He is also chair of the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which is a public-private partnership partially sponsored by several companies and has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to study pharmacotherapies, including naltrexone, nalmefene, and acamprosate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Naltrexone reduces the risk for hospitalization for alcohol use disorder (AUD), regardless of whether it is used alone or in conjunction with disulfiram or acamprosate, research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 10-year data on more than 125,000 Swedish residents with AUD and found that naltrexone, used as monotherapy or combined with acamprosate or disulfiram, was associated with significantly lower risk for AUD hospitalization or all-cause hospitalization in comparison with patients who did not use AUD medication. The patients ranged in age from 16 to 64 years.

By contrast, benzodiazepines and acamprosate monotherapy were associated with increased risk for AUD hospitalization.

“The take-home message for practicing clinicians would be that especially naltrexone use is associated with favorable treatment outcomes and should be utilized as part of the treatment protocol for AUD,” study investigator Milja Heikkinen, MD, specialist in forensic psychiatry and addiction medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, told this news organization.

On the other hand, “benzodiazepines should be avoided and should not be administered other than for alcohol withdrawal symptoms,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 4 in Addiction.

Real-world data

Previous research has shown that disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone, and nalmefene are efficacious in treating AUD, but most studies have been randomized controlled trials or meta-analyses, the authors write.

“Very little is known about overall health outcomes (such as risks of hospitalization and mortality) associated with specific treatments in real-world circumstances,” they write.

“The study was motivated by the fact that, although AUD is a significant public health concern, very little is known, especially about the comparative effectiveness of medications indicated in AUD,” said Dr. Heikkinen.

who had been diagnosed with AUD (62.5% men; mean [standard deviation] age, 38.1 [15.9] years). They followed the cohort over a median of 4.6 years (interquartile range, 2.1-.2 years).

During the follow-up period, roughly one-fourth of patients (25.6) underwent treatment with one or more drugs.

The main outcome measure was AUD-related hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were hospitalization for any cause and for alcohol-related somatic causes; all-cause mortality; and work disability.

Two types of analyses were conducted. The within-individual analyses, designed to eliminate selection bias, compared the use of a medication to periods during which the same individual was not using the medication.

Between-individual analyses (adjusted for sex, age, educational level, number of previous AUD-related hospitalizations, time since first AUD diagnosis, comorbidities, and use of other medications) utilized a “traditional” multivariate-adjusted Cox hazards regression model.

AUD pharmacotherapy ‘underutilized’

Close to one-fourth of patients (23.9%) experienced the main outcome event (AUD-related hospitalization) during the follow-up period.

The within-individual analysis showed that naltrexone – whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively with disulfiram or acamprosate – “was associated with a significantly lower risk of AUD-related hospitalization, compared to those time periods in which the same individual did not use any AUD medication,” the authors report.

By contrast, they state, acamprosate monotherapy and benzodiazepines were associated with a significantly higher risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

Similar results were obtained in the between-individual analysis. Longer duration of naltrexone use was associated with lower risk for AUD-related hospitalization.

The pattern was also found when the outcome was hospitalization for any cause. However, unlike the findings of the within-individual model, the second model found that acamprosate monotherapy was not associated with a higher risk for any-cause hospitalization.

Polytherapy, including combinations of the four AUD medications, as well as disulfiram monotherapy were similarly associated with lower risk for hospitalization for alcohol-related somatic causes.

Of the overall cohort, 6.2% died during the follow-up period. No association was found between disulfiram, acamprosate, nalmefene, and naltrexone use and all-cause mortality. By contrast, benzodiazepine use was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate (hazard ratio, 1.11; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.19).

“AUD drugs are underutilized, despite AUD being a significant public health concern,” Dr. Heikkinen noted. On the other hand, benzodiazepine use is “very common.”

‘Ravages’ of benzodiazepines

Commenting on the study in an interview, John Krystal, MD, professor and chair of psychiatry and director of the Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said, “The main message from the study for practicing clinicians is that treatment works.”

Dr. Krystal, who was not involved with the study, noted that “many practicing clinicians are discouraged by the course of their patients with AUD, and this study highlights that naltrexone, perhaps in combination with other medications, may be effective in preventing hospitalization and, presumably, other hospitalization-related complications of AUD.”

Also commenting on the study, Raymond Anton, MD, professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, suggested that the “clinical knowledge of the harm of benzodiazepines in those with AUD is reinforced by these findings.”

In fact, the harm of benzodiazepines might be the study’s “most important message ... [a message that was] recently highlighted by the Netflix series “The Queen’s Gambit”, which shows the ravages of using both together, or how one leads to potential addiction with the other,” said Dr. Anton, who was not involved with the study.

The other “big take-home message is that naltrexone should be used more frequently,” said Dr. Anton, distinguished professor of psychiatry at the university and scientific director of the Charleston Alcohol Research Center. He noted that there are “recent data suggesting some clinical and genetic indicators that predict responsiveness to these medications, improving efficacy.”

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Dr. Heikkinen reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. Krystal consults for companies currently developing other treatments for AUDs and receives medications to test from AstraZeneca and Novartis for NIAAA-funded research programs. Dr. Anton has consulted for Alkermes, Lipha, and Lundbeck in the past. He is also chair of the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which is a public-private partnership partially sponsored by several companies and has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to study pharmacotherapies, including naltrexone, nalmefene, and acamprosate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Machine learning flags key risk factors for suicide attempts

A history of suicidal behaviors or ideation, functional impairment related to mental health disorders, and socioeconomic disadvantage are the three most important risk factors predicting subsequent suicide attempts, new research suggests.

Investigators applied a machine-learning model to data on over 34,500 adults drawn from a large national survey database. After analyzing more than 2,500 survey questions, key areas were identified that yielded the most accurate predictions of who might be at risk for later suicide attempt.

These predictors included experiencing previous suicidal behaviors and ideation or functional impairment because of emotional problems, being at a younger age, having a lower educational achievement, and experiencing a recent financial crisis.

“Our machine learning model confirmed well-known risk factors of suicide attempt, including previous suicidal behavior and depression; and we also identified functional impairment, such as doing activities less carefully or accomplishing less because of emotional problems, as a new important risk,” lead author Angel Garcia de la Garza, PhD candidate in the department of biostatistics, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“We hope our results provide a novel avenue for future suicide risk assessment,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The findings were published online Jan. 6 in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Rich’ dataset

Previous research using machine learning approaches to study nonfatal suicide attempt prediction has focused on high-risk patients in clinical treatment. However, more than one-third of individuals making nonfatal suicide attempts do not receive mental health treatment, Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

To gain further insight into predictors of suicide risk in nonclinical populations, the researchers turned to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a longitudinal survey of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults.

“We wanted to extend our understanding of suicide attempt risk factors beyond high-risk clinical populations to the general adult population; and the richness of the NESARC dataset provides a unique opportunity to do so,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The NESARC surveys were conducted in two waves: Wave 1 (2001-2002) and wave 2 (2004-2005), in which participants self-reported nonfatal suicide attempts in the preceding 3 years since wave 1.

Assessment of wave 1 participants was based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSM-IV.

“This survey’s extensive assessment instrument contained a detailed evaluation of substance use, psychiatric disorders, and symptoms not routinely available in electronic health records,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

The wave 1 survey contained 2,805 separate questions. From participants’ responses, the investigators derived 180 variables for three categories: past-year, prior-to-past-year, and lifetime mental disorders.

They then identified 2,978 factors associated with suicide attempts and used a statistical method called balanced random forest to classify suicide attempts at wave 2. Each variable was accorded an “importance score” using identified wave 1 features.

The outcome variable of attempted suicide at any point during the 3 years prior to the wave 2 interview was defined by combining responses to three wave 2 questions:

- In your entire life, did you ever attempt suicide?

- If yes, how old were you the first time?

- If the most recent event occurred within the last 3 years, how old were you during the most recent time?

Suicide risk severity was classified into four groups (low, medium, high, and very high) on the basis of the top-performing risk factors.

A statistical model combining survey design and nonresponse weights enabled estimates to be representative of the U.S. population, based on the 2000 census.

Out-of-fold model prediction assessed performance of the model, using area under receiver operator curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity.

Daily functioning

Of all participants, 70.2% (n = 34,653; almost 60% women) completed wave 2 interviews. The weighted mean ages at waves 1 and 2 were 45.1 and 48.2 years, respectively.

Of wave 2 respondents, 0.6% (n = 222) attempted suicide during the preceding 3 years.

Half of those who attempted suicide within the first year were classified as “very high risk,” while 33.2% of those who attempted suicide between the first and second year and 33.3% of those who attempted suicide between the second and third year were classified as “very high risk.”

Among participants who attempted suicide between the third year and follow-up, 16.48% were classified as “very high risk.”

The model accurately captured classification of participants, even across demographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race, and income.

Younger individuals (aged 18-36 years) were at higher risk, compared with older individuals. In addition, women were at higher risk than were men, White participants were at higher risk than were non-White participants, and individuals with lower income were at greater risk than were those with higher income.

The model found that 1.8% of the U.S. population had a 10% or greater risk of a suicide attempt.

The most important risk factors identified were the three questions about previous suicidal ideation or behavior; three items from the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (feeling downhearted, doing activities less carefully, or accomplishing less because of emotional problems); younger age; lower educational achievement; and recent financial crisis.

“The clinical assessment of suicide risk typically focuses on acute suicidal symptoms, together with depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and recent stressful events,” coinvestigator Mark Olfson, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Olfson said.

Extra vigilance

Commenting on the study in an interview, April C. Foreman, PhD, an executive board member of the American Association of Suicidology, noted that some of the findings were not surprising.

“When discharging a patient from inpatient care, or seeing them in primary care, bring up mental health concerns proactively and ask whether they have ever attempted suicide or harmed themselves – even a long time ago – just as you ask about a family history of heart disease or cancer, or other health issues,” said Dr. Foreman, chief medical officer of the Kevin and Margaret Hines Foundation.

She noted that half of people who die by suicide have a primary care visit within the preceding month.

“Primary care is a great place to get a suicide history and follow the patient with extra vigilance, just as you would with any other risk factors,” Dr. Foreman said.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and its Intramural Program. The study authors and Dr. Foreman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A history of suicidal behaviors or ideation, functional impairment related to mental health disorders, and socioeconomic disadvantage are the three most important risk factors predicting subsequent suicide attempts, new research suggests.

Investigators applied a machine-learning model to data on over 34,500 adults drawn from a large national survey database. After analyzing more than 2,500 survey questions, key areas were identified that yielded the most accurate predictions of who might be at risk for later suicide attempt.

These predictors included experiencing previous suicidal behaviors and ideation or functional impairment because of emotional problems, being at a younger age, having a lower educational achievement, and experiencing a recent financial crisis.

“Our machine learning model confirmed well-known risk factors of suicide attempt, including previous suicidal behavior and depression; and we also identified functional impairment, such as doing activities less carefully or accomplishing less because of emotional problems, as a new important risk,” lead author Angel Garcia de la Garza, PhD candidate in the department of biostatistics, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“We hope our results provide a novel avenue for future suicide risk assessment,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The findings were published online Jan. 6 in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Rich’ dataset

Previous research using machine learning approaches to study nonfatal suicide attempt prediction has focused on high-risk patients in clinical treatment. However, more than one-third of individuals making nonfatal suicide attempts do not receive mental health treatment, Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

To gain further insight into predictors of suicide risk in nonclinical populations, the researchers turned to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a longitudinal survey of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults.

“We wanted to extend our understanding of suicide attempt risk factors beyond high-risk clinical populations to the general adult population; and the richness of the NESARC dataset provides a unique opportunity to do so,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The NESARC surveys were conducted in two waves: Wave 1 (2001-2002) and wave 2 (2004-2005), in which participants self-reported nonfatal suicide attempts in the preceding 3 years since wave 1.

Assessment of wave 1 participants was based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSM-IV.

“This survey’s extensive assessment instrument contained a detailed evaluation of substance use, psychiatric disorders, and symptoms not routinely available in electronic health records,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

The wave 1 survey contained 2,805 separate questions. From participants’ responses, the investigators derived 180 variables for three categories: past-year, prior-to-past-year, and lifetime mental disorders.

They then identified 2,978 factors associated with suicide attempts and used a statistical method called balanced random forest to classify suicide attempts at wave 2. Each variable was accorded an “importance score” using identified wave 1 features.

The outcome variable of attempted suicide at any point during the 3 years prior to the wave 2 interview was defined by combining responses to three wave 2 questions:

- In your entire life, did you ever attempt suicide?

- If yes, how old were you the first time?

- If the most recent event occurred within the last 3 years, how old were you during the most recent time?

Suicide risk severity was classified into four groups (low, medium, high, and very high) on the basis of the top-performing risk factors.

A statistical model combining survey design and nonresponse weights enabled estimates to be representative of the U.S. population, based on the 2000 census.

Out-of-fold model prediction assessed performance of the model, using area under receiver operator curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity.

Daily functioning

Of all participants, 70.2% (n = 34,653; almost 60% women) completed wave 2 interviews. The weighted mean ages at waves 1 and 2 were 45.1 and 48.2 years, respectively.

Of wave 2 respondents, 0.6% (n = 222) attempted suicide during the preceding 3 years.

Half of those who attempted suicide within the first year were classified as “very high risk,” while 33.2% of those who attempted suicide between the first and second year and 33.3% of those who attempted suicide between the second and third year were classified as “very high risk.”

Among participants who attempted suicide between the third year and follow-up, 16.48% were classified as “very high risk.”

The model accurately captured classification of participants, even across demographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race, and income.

Younger individuals (aged 18-36 years) were at higher risk, compared with older individuals. In addition, women were at higher risk than were men, White participants were at higher risk than were non-White participants, and individuals with lower income were at greater risk than were those with higher income.

The model found that 1.8% of the U.S. population had a 10% or greater risk of a suicide attempt.

The most important risk factors identified were the three questions about previous suicidal ideation or behavior; three items from the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (feeling downhearted, doing activities less carefully, or accomplishing less because of emotional problems); younger age; lower educational achievement; and recent financial crisis.

“The clinical assessment of suicide risk typically focuses on acute suicidal symptoms, together with depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and recent stressful events,” coinvestigator Mark Olfson, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Olfson said.

Extra vigilance

Commenting on the study in an interview, April C. Foreman, PhD, an executive board member of the American Association of Suicidology, noted that some of the findings were not surprising.

“When discharging a patient from inpatient care, or seeing them in primary care, bring up mental health concerns proactively and ask whether they have ever attempted suicide or harmed themselves – even a long time ago – just as you ask about a family history of heart disease or cancer, or other health issues,” said Dr. Foreman, chief medical officer of the Kevin and Margaret Hines Foundation.

She noted that half of people who die by suicide have a primary care visit within the preceding month.

“Primary care is a great place to get a suicide history and follow the patient with extra vigilance, just as you would with any other risk factors,” Dr. Foreman said.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and its Intramural Program. The study authors and Dr. Foreman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A history of suicidal behaviors or ideation, functional impairment related to mental health disorders, and socioeconomic disadvantage are the three most important risk factors predicting subsequent suicide attempts, new research suggests.

Investigators applied a machine-learning model to data on over 34,500 adults drawn from a large national survey database. After analyzing more than 2,500 survey questions, key areas were identified that yielded the most accurate predictions of who might be at risk for later suicide attempt.

These predictors included experiencing previous suicidal behaviors and ideation or functional impairment because of emotional problems, being at a younger age, having a lower educational achievement, and experiencing a recent financial crisis.

“Our machine learning model confirmed well-known risk factors of suicide attempt, including previous suicidal behavior and depression; and we also identified functional impairment, such as doing activities less carefully or accomplishing less because of emotional problems, as a new important risk,” lead author Angel Garcia de la Garza, PhD candidate in the department of biostatistics, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“We hope our results provide a novel avenue for future suicide risk assessment,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The findings were published online Jan. 6 in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Rich’ dataset

Previous research using machine learning approaches to study nonfatal suicide attempt prediction has focused on high-risk patients in clinical treatment. However, more than one-third of individuals making nonfatal suicide attempts do not receive mental health treatment, Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

To gain further insight into predictors of suicide risk in nonclinical populations, the researchers turned to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a longitudinal survey of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults.

“We wanted to extend our understanding of suicide attempt risk factors beyond high-risk clinical populations to the general adult population; and the richness of the NESARC dataset provides a unique opportunity to do so,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza said.

The NESARC surveys were conducted in two waves: Wave 1 (2001-2002) and wave 2 (2004-2005), in which participants self-reported nonfatal suicide attempts in the preceding 3 years since wave 1.

Assessment of wave 1 participants was based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule DSM-IV.

“This survey’s extensive assessment instrument contained a detailed evaluation of substance use, psychiatric disorders, and symptoms not routinely available in electronic health records,” Mr. Garcia de la Garza noted.

The wave 1 survey contained 2,805 separate questions. From participants’ responses, the investigators derived 180 variables for three categories: past-year, prior-to-past-year, and lifetime mental disorders.

They then identified 2,978 factors associated with suicide attempts and used a statistical method called balanced random forest to classify suicide attempts at wave 2. Each variable was accorded an “importance score” using identified wave 1 features.

The outcome variable of attempted suicide at any point during the 3 years prior to the wave 2 interview was defined by combining responses to three wave 2 questions:

- In your entire life, did you ever attempt suicide?

- If yes, how old were you the first time?

- If the most recent event occurred within the last 3 years, how old were you during the most recent time?

Suicide risk severity was classified into four groups (low, medium, high, and very high) on the basis of the top-performing risk factors.

A statistical model combining survey design and nonresponse weights enabled estimates to be representative of the U.S. population, based on the 2000 census.

Out-of-fold model prediction assessed performance of the model, using area under receiver operator curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity.

Daily functioning

Of all participants, 70.2% (n = 34,653; almost 60% women) completed wave 2 interviews. The weighted mean ages at waves 1 and 2 were 45.1 and 48.2 years, respectively.

Of wave 2 respondents, 0.6% (n = 222) attempted suicide during the preceding 3 years.

Half of those who attempted suicide within the first year were classified as “very high risk,” while 33.2% of those who attempted suicide between the first and second year and 33.3% of those who attempted suicide between the second and third year were classified as “very high risk.”

Among participants who attempted suicide between the third year and follow-up, 16.48% were classified as “very high risk.”

The model accurately captured classification of participants, even across demographic characteristics, such as age, sex, race, and income.

Younger individuals (aged 18-36 years) were at higher risk, compared with older individuals. In addition, women were at higher risk than were men, White participants were at higher risk than were non-White participants, and individuals with lower income were at greater risk than were those with higher income.

The model found that 1.8% of the U.S. population had a 10% or greater risk of a suicide attempt.

The most important risk factors identified were the three questions about previous suicidal ideation or behavior; three items from the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (feeling downhearted, doing activities less carefully, or accomplishing less because of emotional problems); younger age; lower educational achievement; and recent financial crisis.

“The clinical assessment of suicide risk typically focuses on acute suicidal symptoms, together with depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and recent stressful events,” coinvestigator Mark Olfson, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

Dr. Olfson said.

Extra vigilance

Commenting on the study in an interview, April C. Foreman, PhD, an executive board member of the American Association of Suicidology, noted that some of the findings were not surprising.

“When discharging a patient from inpatient care, or seeing them in primary care, bring up mental health concerns proactively and ask whether they have ever attempted suicide or harmed themselves – even a long time ago – just as you ask about a family history of heart disease or cancer, or other health issues,” said Dr. Foreman, chief medical officer of the Kevin and Margaret Hines Foundation.

She noted that half of people who die by suicide have a primary care visit within the preceding month.

“Primary care is a great place to get a suicide history and follow the patient with extra vigilance, just as you would with any other risk factors,” Dr. Foreman said.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and its Intramural Program. The study authors and Dr. Foreman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New evidence shows that COVID-19 invades the brain

, new animal research suggests. Investigators injected spike 1 (S1), which is found on the tufts of the “red spikes” of the virus, into mice and found that it crossed the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and was taken up not only by brain regions and the brain space but also by other organs – specifically, the lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys.

“We found that the S1 protein, which is the protein COVID-19 uses to ‘grab onto’ cells, crosses the BBB and is a good model of what the virus does when it enters the brain,” lead author William A. Banks, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“When proteins such as the S1 protein become detached from the virus, they can enter the brain and cause mayhem, causing the brain to release cytokines, which, in turn, cause inflammation and subsequent neurotoxicity,” said Dr. Banks, associate chief of staff and a researcher at the Puget Sound Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

Neurologic symptoms

COVID-19 is associated with a variety of central nervous system symptoms, including the loss of taste and smell, headaches, confusion, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage, the investigators noted.

Dr. Banks explained that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the brain by crossing the BBB, acting directly on the brain centers responsible for other body functions. The respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 may therefore result partly from the invasion of the areas of the brain responsible for respiratory functions, not only from the virus’ action at the site of the lungs.

The researchers set out to assess whether a particular viral protein – S1, which is a subunit of the viral spike protein – could cross the BBB or enter other organs when injected into mice. They found that, when intravenously injected S1 (I-S1) was cleared from the blood, tissues in multiple organs, including the lung, spleen, kidney, and liver, took it up.

Notably, uptake of I-S1 was higher in the liver, “suggesting that this protein is cleared from the blood predominantly by the liver,” Dr. Banks said. In addition, uptake by the lungs is “important, because that’s where many of the effects of the virus are,” he added.

The researchers found that I-S1 in the brains of the mice was “mostly degraded” 30 minutes following injection. “This indicates that I-S1 enters the BBB intact but is eventually degraded in the brain,” they wrote.

Moreover, by 30 minutes, more than half of the I-S1 proteins had crossed the capillary wall and had fully entered into the brain parenchymal and interstitial fluid spaces, as well as other regions.

More severe outcomes in men

The researchers then induced an inflammatory state in the mice through injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and found that inflammation increased I-S1 uptake in both the brain and the lung (where uptake was increased by 101%). “These results show that inflammation could increase S1 toxicity for lung tissue by increasing its uptake,” the authors suggested. Moreover, inflammation also increased the entry of I-S1 into the brain, “likely due to BBB disruption.”

In human beings, male sex and APOE4 genotype are risk factors for both contracting COVID-19 and having a poor outcome, the authors noted. As a result, they examined I-S1 uptake in male and female mice that expressed human APOE3 or APOE4 (induced by a mouse ApoE promoter).

Multiple-comparison tests showed that among male mice that expressed human APOE3, the “fastest I-S1 uptake” was in the olfactory bulb, liver, and kidney. Female mice displayed increased APOE3 uptake in the spleen.

“This observation might relate to the increased susceptibility of men to more severe COVID-19 outcomes,” coauthor Jacob Raber, PhD, professor, departments of behavioral neuroscience, neurology, and radiation medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in a press release.

In addition to intravenous I-S1 injection, the researchers also investigated the effects of intranasal administration. They found that, although it also entered the brain, it did so at levels roughly 10 times lower than those induced by intravenous administration.

“Frightening tricks”

Dr. Banks said his laboratory has studied the BBB in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, diabetes, and HIV. “Our experience with viruses is that they do an incredible number of things and have a frightening number of tricks,” he said. In this case, “the virus is probably causing inflammation by releasing cytokines elsewhere in the body that get into the brain through the BBB.” Conversely, “the virus itself may enter the brain by crossing the BBB and directly cause brain cells to release their own cytokines,” he added.

An additional finding of the study is that, whatever the S1 protein does in the brain is a model for what the entire virus itself does, because these proteins often bring the viruses along with them, he added.

Dr. Banks said the clinical implications of the findings are that antibodies from those who have already had COVID-19 could potentially be directed against S1. Similarly, he added, so can COVID-19 vaccines, which induce production of S1.

“When an antibody locks onto something, it prevents it from crossing the BBB,” Dr. Banks noted.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study, Howard E. Gendelman, MD, Margaret R. Larson Professor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases and professor and chair of the department of pharmacology and experimental neuroscience, University of Nebraska, Omaha, said the study is confirmatory.

“What this paper highlights, and we have known for a long time, is that COVID-19 is a systemic, not only a respiratory, disease involving many organs and tissues and can yield not only pulmonary problems but also a whole host of cardiac, brain, and kidney problems,” he said.

“So the fact that these proteins are getting in [the brain] and are able to induce a reaction in the brain itself, and this is part of the complex progressive nature of COVID-19, is an important finding,” added Dr. Gendelman, director of the center for neurodegenerative disorders at the university. He was not involved with the study.

The study was supported by the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Gendelman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new animal research suggests. Investigators injected spike 1 (S1), which is found on the tufts of the “red spikes” of the virus, into mice and found that it crossed the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and was taken up not only by brain regions and the brain space but also by other organs – specifically, the lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys.

“We found that the S1 protein, which is the protein COVID-19 uses to ‘grab onto’ cells, crosses the BBB and is a good model of what the virus does when it enters the brain,” lead author William A. Banks, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“When proteins such as the S1 protein become detached from the virus, they can enter the brain and cause mayhem, causing the brain to release cytokines, which, in turn, cause inflammation and subsequent neurotoxicity,” said Dr. Banks, associate chief of staff and a researcher at the Puget Sound Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

Neurologic symptoms

COVID-19 is associated with a variety of central nervous system symptoms, including the loss of taste and smell, headaches, confusion, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage, the investigators noted.

Dr. Banks explained that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the brain by crossing the BBB, acting directly on the brain centers responsible for other body functions. The respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 may therefore result partly from the invasion of the areas of the brain responsible for respiratory functions, not only from the virus’ action at the site of the lungs.

The researchers set out to assess whether a particular viral protein – S1, which is a subunit of the viral spike protein – could cross the BBB or enter other organs when injected into mice. They found that, when intravenously injected S1 (I-S1) was cleared from the blood, tissues in multiple organs, including the lung, spleen, kidney, and liver, took it up.

Notably, uptake of I-S1 was higher in the liver, “suggesting that this protein is cleared from the blood predominantly by the liver,” Dr. Banks said. In addition, uptake by the lungs is “important, because that’s where many of the effects of the virus are,” he added.

The researchers found that I-S1 in the brains of the mice was “mostly degraded” 30 minutes following injection. “This indicates that I-S1 enters the BBB intact but is eventually degraded in the brain,” they wrote.

Moreover, by 30 minutes, more than half of the I-S1 proteins had crossed the capillary wall and had fully entered into the brain parenchymal and interstitial fluid spaces, as well as other regions.

More severe outcomes in men

The researchers then induced an inflammatory state in the mice through injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and found that inflammation increased I-S1 uptake in both the brain and the lung (where uptake was increased by 101%). “These results show that inflammation could increase S1 toxicity for lung tissue by increasing its uptake,” the authors suggested. Moreover, inflammation also increased the entry of I-S1 into the brain, “likely due to BBB disruption.”

In human beings, male sex and APOE4 genotype are risk factors for both contracting COVID-19 and having a poor outcome, the authors noted. As a result, they examined I-S1 uptake in male and female mice that expressed human APOE3 or APOE4 (induced by a mouse ApoE promoter).

Multiple-comparison tests showed that among male mice that expressed human APOE3, the “fastest I-S1 uptake” was in the olfactory bulb, liver, and kidney. Female mice displayed increased APOE3 uptake in the spleen.

“This observation might relate to the increased susceptibility of men to more severe COVID-19 outcomes,” coauthor Jacob Raber, PhD, professor, departments of behavioral neuroscience, neurology, and radiation medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in a press release.

In addition to intravenous I-S1 injection, the researchers also investigated the effects of intranasal administration. They found that, although it also entered the brain, it did so at levels roughly 10 times lower than those induced by intravenous administration.

“Frightening tricks”

Dr. Banks said his laboratory has studied the BBB in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, diabetes, and HIV. “Our experience with viruses is that they do an incredible number of things and have a frightening number of tricks,” he said. In this case, “the virus is probably causing inflammation by releasing cytokines elsewhere in the body that get into the brain through the BBB.” Conversely, “the virus itself may enter the brain by crossing the BBB and directly cause brain cells to release their own cytokines,” he added.

An additional finding of the study is that, whatever the S1 protein does in the brain is a model for what the entire virus itself does, because these proteins often bring the viruses along with them, he added.

Dr. Banks said the clinical implications of the findings are that antibodies from those who have already had COVID-19 could potentially be directed against S1. Similarly, he added, so can COVID-19 vaccines, which induce production of S1.

“When an antibody locks onto something, it prevents it from crossing the BBB,” Dr. Banks noted.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study, Howard E. Gendelman, MD, Margaret R. Larson Professor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases and professor and chair of the department of pharmacology and experimental neuroscience, University of Nebraska, Omaha, said the study is confirmatory.

“What this paper highlights, and we have known for a long time, is that COVID-19 is a systemic, not only a respiratory, disease involving many organs and tissues and can yield not only pulmonary problems but also a whole host of cardiac, brain, and kidney problems,” he said.

“So the fact that these proteins are getting in [the brain] and are able to induce a reaction in the brain itself, and this is part of the complex progressive nature of COVID-19, is an important finding,” added Dr. Gendelman, director of the center for neurodegenerative disorders at the university. He was not involved with the study.

The study was supported by the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Gendelman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new animal research suggests. Investigators injected spike 1 (S1), which is found on the tufts of the “red spikes” of the virus, into mice and found that it crossed the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and was taken up not only by brain regions and the brain space but also by other organs – specifically, the lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys.

“We found that the S1 protein, which is the protein COVID-19 uses to ‘grab onto’ cells, crosses the BBB and is a good model of what the virus does when it enters the brain,” lead author William A. Banks, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“When proteins such as the S1 protein become detached from the virus, they can enter the brain and cause mayhem, causing the brain to release cytokines, which, in turn, cause inflammation and subsequent neurotoxicity,” said Dr. Banks, associate chief of staff and a researcher at the Puget Sound Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

Neurologic symptoms

COVID-19 is associated with a variety of central nervous system symptoms, including the loss of taste and smell, headaches, confusion, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage, the investigators noted.

Dr. Banks explained that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the brain by crossing the BBB, acting directly on the brain centers responsible for other body functions. The respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 may therefore result partly from the invasion of the areas of the brain responsible for respiratory functions, not only from the virus’ action at the site of the lungs.

The researchers set out to assess whether a particular viral protein – S1, which is a subunit of the viral spike protein – could cross the BBB or enter other organs when injected into mice. They found that, when intravenously injected S1 (I-S1) was cleared from the blood, tissues in multiple organs, including the lung, spleen, kidney, and liver, took it up.

Notably, uptake of I-S1 was higher in the liver, “suggesting that this protein is cleared from the blood predominantly by the liver,” Dr. Banks said. In addition, uptake by the lungs is “important, because that’s where many of the effects of the virus are,” he added.

The researchers found that I-S1 in the brains of the mice was “mostly degraded” 30 minutes following injection. “This indicates that I-S1 enters the BBB intact but is eventually degraded in the brain,” they wrote.

Moreover, by 30 minutes, more than half of the I-S1 proteins had crossed the capillary wall and had fully entered into the brain parenchymal and interstitial fluid spaces, as well as other regions.

More severe outcomes in men

The researchers then induced an inflammatory state in the mice through injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and found that inflammation increased I-S1 uptake in both the brain and the lung (where uptake was increased by 101%). “These results show that inflammation could increase S1 toxicity for lung tissue by increasing its uptake,” the authors suggested. Moreover, inflammation also increased the entry of I-S1 into the brain, “likely due to BBB disruption.”

In human beings, male sex and APOE4 genotype are risk factors for both contracting COVID-19 and having a poor outcome, the authors noted. As a result, they examined I-S1 uptake in male and female mice that expressed human APOE3 or APOE4 (induced by a mouse ApoE promoter).

Multiple-comparison tests showed that among male mice that expressed human APOE3, the “fastest I-S1 uptake” was in the olfactory bulb, liver, and kidney. Female mice displayed increased APOE3 uptake in the spleen.

“This observation might relate to the increased susceptibility of men to more severe COVID-19 outcomes,” coauthor Jacob Raber, PhD, professor, departments of behavioral neuroscience, neurology, and radiation medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in a press release.

In addition to intravenous I-S1 injection, the researchers also investigated the effects of intranasal administration. They found that, although it also entered the brain, it did so at levels roughly 10 times lower than those induced by intravenous administration.

“Frightening tricks”

Dr. Banks said his laboratory has studied the BBB in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, diabetes, and HIV. “Our experience with viruses is that they do an incredible number of things and have a frightening number of tricks,” he said. In this case, “the virus is probably causing inflammation by releasing cytokines elsewhere in the body that get into the brain through the BBB.” Conversely, “the virus itself may enter the brain by crossing the BBB and directly cause brain cells to release their own cytokines,” he added.

An additional finding of the study is that, whatever the S1 protein does in the brain is a model for what the entire virus itself does, because these proteins often bring the viruses along with them, he added.

Dr. Banks said the clinical implications of the findings are that antibodies from those who have already had COVID-19 could potentially be directed against S1. Similarly, he added, so can COVID-19 vaccines, which induce production of S1.

“When an antibody locks onto something, it prevents it from crossing the BBB,” Dr. Banks noted.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study, Howard E. Gendelman, MD, Margaret R. Larson Professor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases and professor and chair of the department of pharmacology and experimental neuroscience, University of Nebraska, Omaha, said the study is confirmatory.

“What this paper highlights, and we have known for a long time, is that COVID-19 is a systemic, not only a respiratory, disease involving many organs and tissues and can yield not only pulmonary problems but also a whole host of cardiac, brain, and kidney problems,” he said.

“So the fact that these proteins are getting in [the brain] and are able to induce a reaction in the brain itself, and this is part of the complex progressive nature of COVID-19, is an important finding,” added Dr. Gendelman, director of the center for neurodegenerative disorders at the university. He was not involved with the study.

The study was supported by the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Gendelman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE NEUROSCIENCE

Global experts map the latest in bipolar management

A new monograph offers a far-reaching update on research and clinical management of bipolar disorders (BDs), including epidemiology, genetics, pathogenesis, psychosocial aspects, and current and investigational therapies.

“I regard this as a ‘global state-of-the-union’ type of paper designed to bring the world up to speed regarding where we’re at and where we’re going in terms of bipolar disorder, to present the changes on the scientific and clinical fronts, and to open up a global conversation about bipolar disorder,” lead author Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, told Medscape Medical News.

“The paper is oriented toward multidisciplinary care, with particular emphasis on primary care, as well as people in healthcare administration and policy, who want a snapshot of where we’re at,” said McIntyre, who is also the head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit and director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance in Chicago, Illinois.

The article was published online December 5 in The Lancet.

Severe, complex

The authors call BPs “a complex group of severe and chronic disorders” that include both BP I and BP II disorders.

“These disorders continue to be the world’s leading causes of disability, morbidity, and mortality, which are significant and getting worse, with studies indicating that bipolar disorders are associated with a loss of roughly 10 to 20 potential years of life,” McIntyre said.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of premature death in people with BD. The second is suicide, the authors state, noting that patients with BDs are roughly 20-30 times more likely to die by suicide compared with the general population. In addition, 30%-50% have a lifetime history of suicide attempts.

BP I is “defined by the presence of a syndromal manic episode,” while BP II is “defined by the presence of a syndromal hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode,” the authors state.

Unlike the DSM-IV-TR, the DSM-5 includes “persistently increased energy or activity, along with elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” in the diagnostic criteria for mania and hypomania, “so diagnosing mania on mood instability alone is no longer sufficient,” the authors note.

In addition, clinicians “should be aware that individuals with BDs presenting with depression will often manifest symptoms of anxiety, agitation, anger-irritability, and attentional disturbance-distractibility (the four A’s), all of which are highly suggestive of mixed features,” they write.

Depression is the “predominant index presentation of BD” and “differentiating BD from major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common clinical challenge for most clinicians.”

Features suggesting a diagnosis of BD rather than MDD include earlier age of onset, phenomenology (e.g., hyperphagia, hypersomnia, psychosis), higher frequency of affective episodes, comorbidities (e.g., substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, binge eating disorders, and migraines), family history of psychopathology, nonresponse to antidepressants or induction of hypomania, mixed features, and comorbidities

The authors advise “routine and systematic screening for BDs in all patients presenting with depressive symptomatology” and recommend using the Mood Disorders Questionnaire and the Hypomania Checklist.

Additional differential diagnoses include psychiatric disorders involving impulsivity, affective instability, anxiety, cognitive disorganization, depression, and psychosis.

“Futuristic” technology

“Although the pathogenesis of BDs is unknown, approximately 70% of the risk for BDs is heritable,” the authors note. They review recent research into genetic loci associated with BDs, based on genome-wide association studies, and the role of genetics not only in BDs but also in overlapping neurologic and psychiatric conditions, insulin resistance, and endocannabinoid signaling.

Inflammatory disturbances may also be implicated, in part related to “lifestyle and environment exposures” common in BDs such as smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, and trauma, they suggest.

An “exciting new technology” analyzing “pluripotent” stem cells might illuminate the pathogenesis of BDs and mechanism of action of treatments by shedding light on mitochondrial dysfunction, McIntyre said.

“This interest in stem cells might almost be seen as futuristic. It is currently being used in the laboratory to understand the biology of BD, and it may eventually lead to the development of new therapeutics,” he added.

“Exciting” treatments

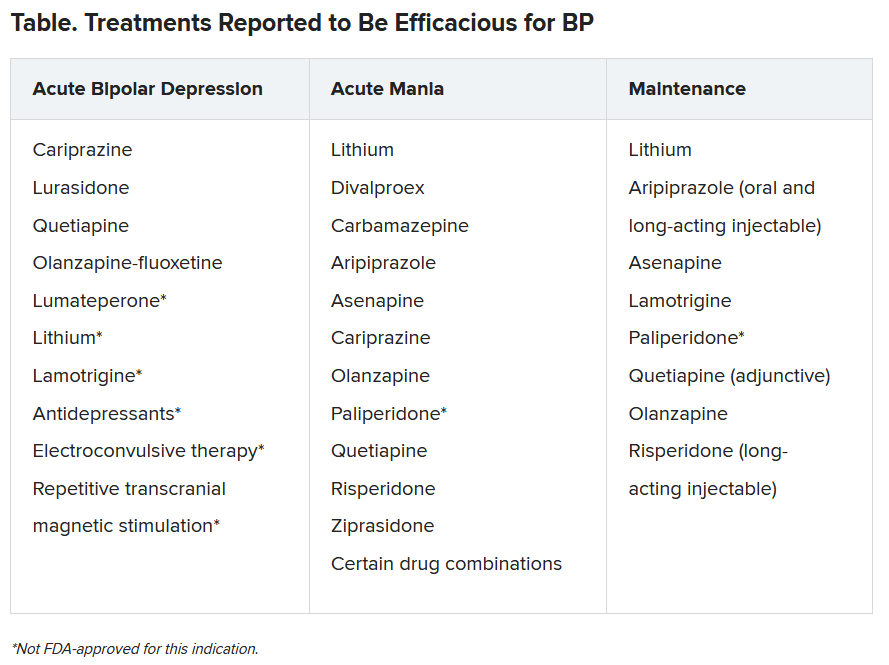

“Our expansive list of treatments and soon-to-be new treatments is very exciting,” said McIntyre.

The authors highlight “ongoing controversy regarding the safe and appropriate use of antidepressants in BD,” cautioning against potential treatment-emergent hypomania and suggesting limited circumstances when antidepressants might be administered.

Lithium remains the “gold standard mood-stabilizing agent” and is “capable of reducing suicidality,” they note.

Nonpharmacologic interventions include patient self-management, compliance, and cognitive enhancement strategies, primary prevention for psychiatric and medical comorbidity, psychosocial treatments and lifestyle interventions during maintenance, as well as surveillance for suicidality during both acute and maintenance phases.

Novel potential treatments include coenzyme Q10, N-acetyl cysteine, statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, omega-3 fatty acids, incretin-based therapies, insulin, nitrous oxide, ketamine, prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and adjunctive bright light therapy.

The authors caution that these investigational agents “cannot be considered efficacious or safe” in the treatment of BDs at present.

Call to action

Commenting for Medscape Medical News, Michael Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he is glad that this “stellar group of authors” with “worldwide psychiatric expertise” wrote the article and he hopes it “gets the readership it deserves.”

Thase, who was not an author, said, “One takeaway is that BDs together comprise one of the world’s great public health problems — probably within the top 10.”

Another “has to do with our ability to do more with the tools we have — ie, ensuring diagnosis, implementing treatment, engaging social support, and using proven therapies from both psychopharmacologic and psychosocial domains.”

McIntyre characterized the article as a “public health call to action, incorporating screening, interesting neurobiological insights, an extensive set of treatments, and cool technological capabilities for the future.”

McIntyre has reported receiving grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Disease/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation, and speaker fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Intra-Cellular, Alkermes, and Minerva, and is chief executive officer of Champignon. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Thase has reported consulting with and receiving research funding from many of the companies that manufacture/sell antidepressants and antipsychotics. He also has reported receiving royalties from the American Psychiatric Press Incorporated, Guilford Publications, Herald House, and W.W. Norton & Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new monograph offers a far-reaching update on research and clinical management of bipolar disorders (BDs), including epidemiology, genetics, pathogenesis, psychosocial aspects, and current and investigational therapies.

“I regard this as a ‘global state-of-the-union’ type of paper designed to bring the world up to speed regarding where we’re at and where we’re going in terms of bipolar disorder, to present the changes on the scientific and clinical fronts, and to open up a global conversation about bipolar disorder,” lead author Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, told Medscape Medical News.

“The paper is oriented toward multidisciplinary care, with particular emphasis on primary care, as well as people in healthcare administration and policy, who want a snapshot of where we’re at,” said McIntyre, who is also the head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit and director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance in Chicago, Illinois.

The article was published online December 5 in The Lancet.

Severe, complex

The authors call BPs “a complex group of severe and chronic disorders” that include both BP I and BP II disorders.

“These disorders continue to be the world’s leading causes of disability, morbidity, and mortality, which are significant and getting worse, with studies indicating that bipolar disorders are associated with a loss of roughly 10 to 20 potential years of life,” McIntyre said.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of premature death in people with BD. The second is suicide, the authors state, noting that patients with BDs are roughly 20-30 times more likely to die by suicide compared with the general population. In addition, 30%-50% have a lifetime history of suicide attempts.

BP I is “defined by the presence of a syndromal manic episode,” while BP II is “defined by the presence of a syndromal hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode,” the authors state.

Unlike the DSM-IV-TR, the DSM-5 includes “persistently increased energy or activity, along with elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” in the diagnostic criteria for mania and hypomania, “so diagnosing mania on mood instability alone is no longer sufficient,” the authors note.

In addition, clinicians “should be aware that individuals with BDs presenting with depression will often manifest symptoms of anxiety, agitation, anger-irritability, and attentional disturbance-distractibility (the four A’s), all of which are highly suggestive of mixed features,” they write.

Depression is the “predominant index presentation of BD” and “differentiating BD from major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common clinical challenge for most clinicians.”

Features suggesting a diagnosis of BD rather than MDD include earlier age of onset, phenomenology (e.g., hyperphagia, hypersomnia, psychosis), higher frequency of affective episodes, comorbidities (e.g., substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, binge eating disorders, and migraines), family history of psychopathology, nonresponse to antidepressants or induction of hypomania, mixed features, and comorbidities

The authors advise “routine and systematic screening for BDs in all patients presenting with depressive symptomatology” and recommend using the Mood Disorders Questionnaire and the Hypomania Checklist.

Additional differential diagnoses include psychiatric disorders involving impulsivity, affective instability, anxiety, cognitive disorganization, depression, and psychosis.

“Futuristic” technology

“Although the pathogenesis of BDs is unknown, approximately 70% of the risk for BDs is heritable,” the authors note. They review recent research into genetic loci associated with BDs, based on genome-wide association studies, and the role of genetics not only in BDs but also in overlapping neurologic and psychiatric conditions, insulin resistance, and endocannabinoid signaling.

Inflammatory disturbances may also be implicated, in part related to “lifestyle and environment exposures” common in BDs such as smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, and trauma, they suggest.

An “exciting new technology” analyzing “pluripotent” stem cells might illuminate the pathogenesis of BDs and mechanism of action of treatments by shedding light on mitochondrial dysfunction, McIntyre said.

“This interest in stem cells might almost be seen as futuristic. It is currently being used in the laboratory to understand the biology of BD, and it may eventually lead to the development of new therapeutics,” he added.

“Exciting” treatments

“Our expansive list of treatments and soon-to-be new treatments is very exciting,” said McIntyre.

The authors highlight “ongoing controversy regarding the safe and appropriate use of antidepressants in BD,” cautioning against potential treatment-emergent hypomania and suggesting limited circumstances when antidepressants might be administered.

Lithium remains the “gold standard mood-stabilizing agent” and is “capable of reducing suicidality,” they note.

Nonpharmacologic interventions include patient self-management, compliance, and cognitive enhancement strategies, primary prevention for psychiatric and medical comorbidity, psychosocial treatments and lifestyle interventions during maintenance, as well as surveillance for suicidality during both acute and maintenance phases.

Novel potential treatments include coenzyme Q10, N-acetyl cysteine, statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, omega-3 fatty acids, incretin-based therapies, insulin, nitrous oxide, ketamine, prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and adjunctive bright light therapy.

The authors caution that these investigational agents “cannot be considered efficacious or safe” in the treatment of BDs at present.

Call to action

Commenting for Medscape Medical News, Michael Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he is glad that this “stellar group of authors” with “worldwide psychiatric expertise” wrote the article and he hopes it “gets the readership it deserves.”

Thase, who was not an author, said, “One takeaway is that BDs together comprise one of the world’s great public health problems — probably within the top 10.”

Another “has to do with our ability to do more with the tools we have — ie, ensuring diagnosis, implementing treatment, engaging social support, and using proven therapies from both psychopharmacologic and psychosocial domains.”

McIntyre characterized the article as a “public health call to action, incorporating screening, interesting neurobiological insights, an extensive set of treatments, and cool technological capabilities for the future.”

McIntyre has reported receiving grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Disease/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation, and speaker fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Intra-Cellular, Alkermes, and Minerva, and is chief executive officer of Champignon. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Thase has reported consulting with and receiving research funding from many of the companies that manufacture/sell antidepressants and antipsychotics. He also has reported receiving royalties from the American Psychiatric Press Incorporated, Guilford Publications, Herald House, and W.W. Norton & Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new monograph offers a far-reaching update on research and clinical management of bipolar disorders (BDs), including epidemiology, genetics, pathogenesis, psychosocial aspects, and current and investigational therapies.

“I regard this as a ‘global state-of-the-union’ type of paper designed to bring the world up to speed regarding where we’re at and where we’re going in terms of bipolar disorder, to present the changes on the scientific and clinical fronts, and to open up a global conversation about bipolar disorder,” lead author Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, told Medscape Medical News.