User login

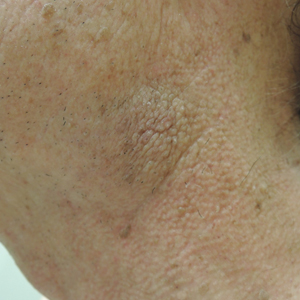

Minimally Hyperpigmented Plaque With Skin Thickening on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Fiddler's Neck

A thorough patient history revealed that the patient was retired and played violin regularly in the local orchestra. Fiddler's neck, or violin hickey, is an uncommon physical examination finding and often is considered a badge of honor by musicians who develop it. Fiddler's neck is a hobby-related callus seen in highly dedicated violin and viola players, and in some circles, it is known as a mark of greatness. In one instance, members of the public were asked to display a violin hickey before they were allowed to play a $3.5 million violin on public display in London, England.1 Fiddler's neck is a benign submandibular lesion caused by pressure and friction on the skin from extensive time spent playing the instrument. The primary cause is thought to be mechanical, but it is not fully understood why the lesion occurs in some musicians and not others, regardless of playing time.1 This submandibular fiddler's neck is distinct from a similarly named supraclavicular lesion, which represents an allergic contact dermatitis to the nickel bracket of the instrument's chin rest and presents with eczematous scale and/or vesicles.2,3 Submandibular fiddler's neck presents with some combination of erythema, edema, lichenification, and scarring just below the angle of the jaw. Occasionally, papules, pustules, and even cyst formation may be noted. Lesions are sometimes mistaken for malignancy or lymphedema. Therefore, a thorough history and clinical expertise are important, as surgical excision should be avoided.2

Depending on presentation, the differential diagnosis also may include malignant melanoma due to irregular pigmentation, branchial cleft cyst or sialolithiasis due to location and texture, or a tumor of the salivary gland.

Management of fiddler's neck may include topical steroids, neck or instrument padding, or decreased playing time. However, the lesion often is worn with pride, seen as a testament to the musician's dedication, and reassurance generally is most appropriate.1

- Roberts C. How to prevent or even cure a violin hickey. Strings. February 1, 2011. https://stringsmagazine.com/how-to-prevent-or-even-cure-a-violin-hickey/. Accessed January 31, 2020.

- Myint CW, Rutt AL, Sataloff RT. Fiddler's neck: a review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:76-79.

- Jue MS, Kim YS, Ro YS. Fiddler's neck accompanied by allergic contact dermatitis to nickel in a viola player. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:88-90.

The Diagnosis: Fiddler's Neck

A thorough patient history revealed that the patient was retired and played violin regularly in the local orchestra. Fiddler's neck, or violin hickey, is an uncommon physical examination finding and often is considered a badge of honor by musicians who develop it. Fiddler's neck is a hobby-related callus seen in highly dedicated violin and viola players, and in some circles, it is known as a mark of greatness. In one instance, members of the public were asked to display a violin hickey before they were allowed to play a $3.5 million violin on public display in London, England.1 Fiddler's neck is a benign submandibular lesion caused by pressure and friction on the skin from extensive time spent playing the instrument. The primary cause is thought to be mechanical, but it is not fully understood why the lesion occurs in some musicians and not others, regardless of playing time.1 This submandibular fiddler's neck is distinct from a similarly named supraclavicular lesion, which represents an allergic contact dermatitis to the nickel bracket of the instrument's chin rest and presents with eczematous scale and/or vesicles.2,3 Submandibular fiddler's neck presents with some combination of erythema, edema, lichenification, and scarring just below the angle of the jaw. Occasionally, papules, pustules, and even cyst formation may be noted. Lesions are sometimes mistaken for malignancy or lymphedema. Therefore, a thorough history and clinical expertise are important, as surgical excision should be avoided.2

Depending on presentation, the differential diagnosis also may include malignant melanoma due to irregular pigmentation, branchial cleft cyst or sialolithiasis due to location and texture, or a tumor of the salivary gland.

Management of fiddler's neck may include topical steroids, neck or instrument padding, or decreased playing time. However, the lesion often is worn with pride, seen as a testament to the musician's dedication, and reassurance generally is most appropriate.1

The Diagnosis: Fiddler's Neck

A thorough patient history revealed that the patient was retired and played violin regularly in the local orchestra. Fiddler's neck, or violin hickey, is an uncommon physical examination finding and often is considered a badge of honor by musicians who develop it. Fiddler's neck is a hobby-related callus seen in highly dedicated violin and viola players, and in some circles, it is known as a mark of greatness. In one instance, members of the public were asked to display a violin hickey before they were allowed to play a $3.5 million violin on public display in London, England.1 Fiddler's neck is a benign submandibular lesion caused by pressure and friction on the skin from extensive time spent playing the instrument. The primary cause is thought to be mechanical, but it is not fully understood why the lesion occurs in some musicians and not others, regardless of playing time.1 This submandibular fiddler's neck is distinct from a similarly named supraclavicular lesion, which represents an allergic contact dermatitis to the nickel bracket of the instrument's chin rest and presents with eczematous scale and/or vesicles.2,3 Submandibular fiddler's neck presents with some combination of erythema, edema, lichenification, and scarring just below the angle of the jaw. Occasionally, papules, pustules, and even cyst formation may be noted. Lesions are sometimes mistaken for malignancy or lymphedema. Therefore, a thorough history and clinical expertise are important, as surgical excision should be avoided.2

Depending on presentation, the differential diagnosis also may include malignant melanoma due to irregular pigmentation, branchial cleft cyst or sialolithiasis due to location and texture, or a tumor of the salivary gland.

Management of fiddler's neck may include topical steroids, neck or instrument padding, or decreased playing time. However, the lesion often is worn with pride, seen as a testament to the musician's dedication, and reassurance generally is most appropriate.1

- Roberts C. How to prevent or even cure a violin hickey. Strings. February 1, 2011. https://stringsmagazine.com/how-to-prevent-or-even-cure-a-violin-hickey/. Accessed January 31, 2020.

- Myint CW, Rutt AL, Sataloff RT. Fiddler's neck: a review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:76-79.

- Jue MS, Kim YS, Ro YS. Fiddler's neck accompanied by allergic contact dermatitis to nickel in a viola player. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:88-90.

- Roberts C. How to prevent or even cure a violin hickey. Strings. February 1, 2011. https://stringsmagazine.com/how-to-prevent-or-even-cure-a-violin-hickey/. Accessed January 31, 2020.

- Myint CW, Rutt AL, Sataloff RT. Fiddler's neck: a review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:76-79.

- Jue MS, Kim YS, Ro YS. Fiddler's neck accompanied by allergic contact dermatitis to nickel in a viola player. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:88-90.

A 74-year-old man with a history of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma presented for an annual skin examination and displayed asymptomatic stable thickening of skin on the left side of the neck below the jawline of several years' duration. Physical examination revealed a 4×2-cm minimally hyperpigmented plaque with skin thickening and a pebbly appearing surface on the left lateral neck just inferior to the angle of the mandible.

Unilateral Papules on the Face

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

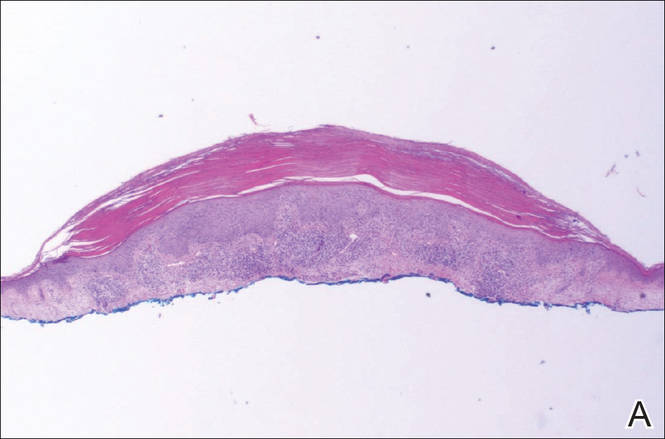

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

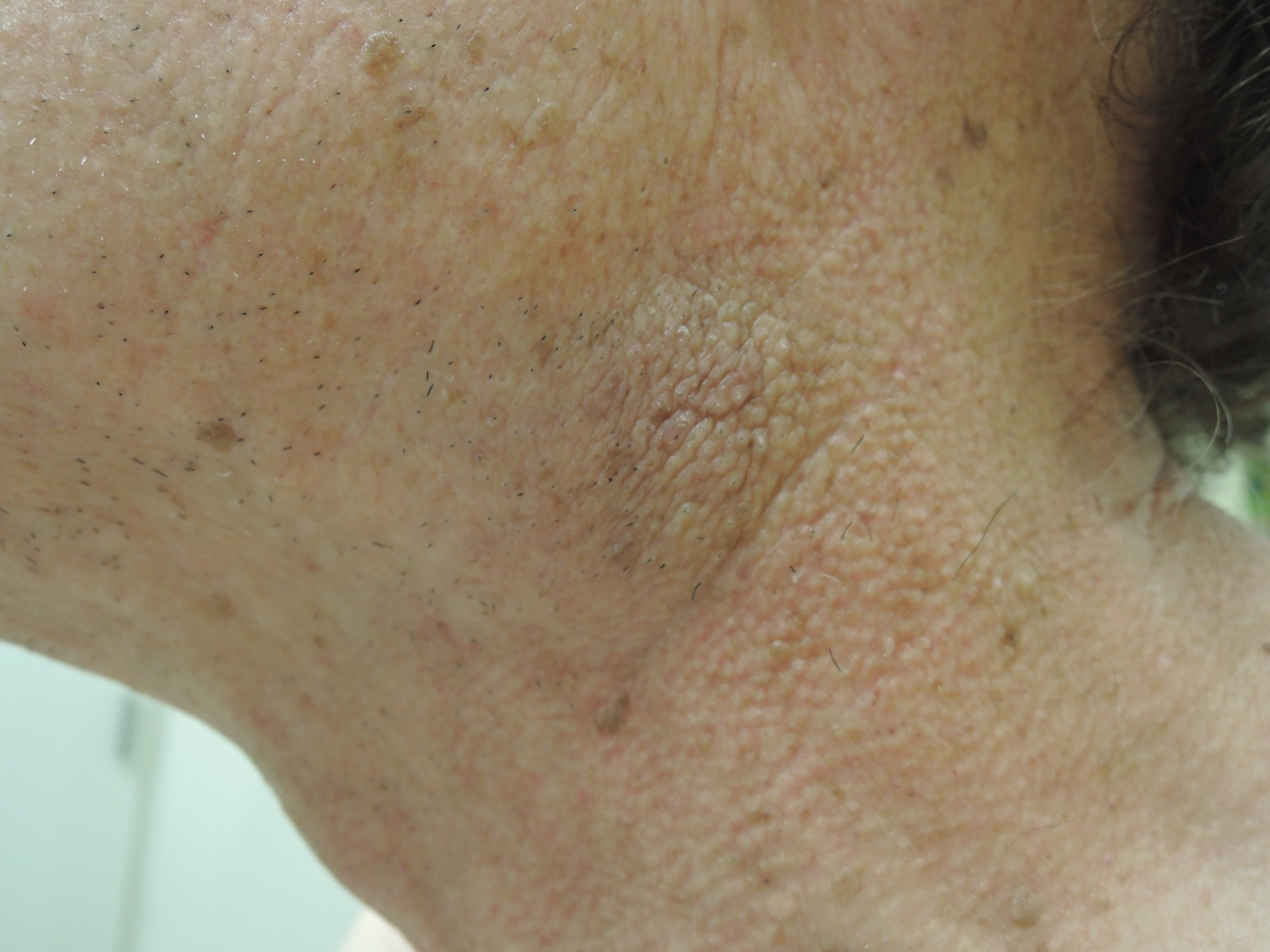

An 18-year-old woman presented with a progressive appearance of firm, red-brown, asymptomatic, 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped papules on the right cheek that developed over the course of 2 years. She had 10 lesions that covered a 2.2 ×4-cm area on the right medial cheek. No similar-appearing lesions were detectable on a full-body skin examination, and no periungual tumors, café au lait macules, or shagreen patches were noted. A full-body skin examination using a Wood lamp revealed 1 small hypopigmented macule on the right second finger. The patient had a history of treatment-refractory migraines; magnetic resonance imaging 5 years prior to the current presentation revealed a nonspecific lesion in the left parietal gyrus. There was no personal or family history of seizures, cognitive delay, kidney disease, or ocular disease. Punch biopsy of a facial lesion was performed for histopathologic correlation.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Stinkbug Staining

The Diagnosis: Stinkbug Staining

After discussing management options with the patient including biopsy, we decided that we would photograph the lesion and follow-up in clinic. While dressing, the patient discovered the source of the pigment, a stinkbug, stuck to the corresponding area of the sock.

The brown marmorated stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys)(Figure) is a member of the Pentatomidae family. This insect is native to East Asia and has become an invasive species in the United States. Their presence has recently increased in the eastern United States and they have become an important agricultural pest as well as a household nuisance. Stinkbugs most commonly interact with humans during the fall and winter months when they enter homes because of cooler temperatures outdoors. They can fit into many unexpected places because of their thin profile.1

Stinkbugs earned their name because of their defensive release of a malodorous chemical. This chemical is comprised of trans-2-decenal and trans-2-octenal, which are both aldehydes and are chemically related to formaldehyde. Based on the material safety data sheet, trans-2-decenal also may be responsible for the orange-brown color seen on the patient’s skin.2 Contact dermatitis caused by direct excretion of this chemical onto human skin has been reported3; anecdotal reports of irritation in agricultural workers have been noted. Stinkbugs are becoming a more common household and agricultural pest and should be recognized as possible causes of some presentations in the dermatology clinic.

- Nielsen AL, Hamilton GC. Seasonal occurrence and impact of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in tree fruit. J Econ Entomol. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Material safety data sheet: trans-2-Decenal. https://fscimage.fishersci.com/msds/45077.htm. Published October 24, 1998. Updated November 20, 2008. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- Anderson BE, Miller JJ, Adams DR. Irritant contact dermatitis to the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Dermatitis. 2012;23:170-172.

The Diagnosis: Stinkbug Staining

After discussing management options with the patient including biopsy, we decided that we would photograph the lesion and follow-up in clinic. While dressing, the patient discovered the source of the pigment, a stinkbug, stuck to the corresponding area of the sock.

The brown marmorated stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys)(Figure) is a member of the Pentatomidae family. This insect is native to East Asia and has become an invasive species in the United States. Their presence has recently increased in the eastern United States and they have become an important agricultural pest as well as a household nuisance. Stinkbugs most commonly interact with humans during the fall and winter months when they enter homes because of cooler temperatures outdoors. They can fit into many unexpected places because of their thin profile.1

Stinkbugs earned their name because of their defensive release of a malodorous chemical. This chemical is comprised of trans-2-decenal and trans-2-octenal, which are both aldehydes and are chemically related to formaldehyde. Based on the material safety data sheet, trans-2-decenal also may be responsible for the orange-brown color seen on the patient’s skin.2 Contact dermatitis caused by direct excretion of this chemical onto human skin has been reported3; anecdotal reports of irritation in agricultural workers have been noted. Stinkbugs are becoming a more common household and agricultural pest and should be recognized as possible causes of some presentations in the dermatology clinic.

The Diagnosis: Stinkbug Staining

After discussing management options with the patient including biopsy, we decided that we would photograph the lesion and follow-up in clinic. While dressing, the patient discovered the source of the pigment, a stinkbug, stuck to the corresponding area of the sock.

The brown marmorated stinkbug (Halyomorpha halys)(Figure) is a member of the Pentatomidae family. This insect is native to East Asia and has become an invasive species in the United States. Their presence has recently increased in the eastern United States and they have become an important agricultural pest as well as a household nuisance. Stinkbugs most commonly interact with humans during the fall and winter months when they enter homes because of cooler temperatures outdoors. They can fit into many unexpected places because of their thin profile.1

Stinkbugs earned their name because of their defensive release of a malodorous chemical. This chemical is comprised of trans-2-decenal and trans-2-octenal, which are both aldehydes and are chemically related to formaldehyde. Based on the material safety data sheet, trans-2-decenal also may be responsible for the orange-brown color seen on the patient’s skin.2 Contact dermatitis caused by direct excretion of this chemical onto human skin has been reported3; anecdotal reports of irritation in agricultural workers have been noted. Stinkbugs are becoming a more common household and agricultural pest and should be recognized as possible causes of some presentations in the dermatology clinic.

- Nielsen AL, Hamilton GC. Seasonal occurrence and impact of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in tree fruit. J Econ Entomol. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Material safety data sheet: trans-2-Decenal. https://fscimage.fishersci.com/msds/45077.htm. Published October 24, 1998. Updated November 20, 2008. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- Anderson BE, Miller JJ, Adams DR. Irritant contact dermatitis to the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Dermatitis. 2012;23:170-172.

- Nielsen AL, Hamilton GC. Seasonal occurrence and impact of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in tree fruit. J Econ Entomol. 2009;102:1133-1140.

- Material safety data sheet: trans-2-Decenal. https://fscimage.fishersci.com/msds/45077.htm. Published October 24, 1998. Updated November 20, 2008. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- Anderson BE, Miller JJ, Adams DR. Irritant contact dermatitis to the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Dermatitis. 2012;23:170-172.

A 56-year-old woman presented at the clinic for a total-body skin examination. A pigmented lesion was found on the medial aspect of the left first toe during the examination. The patient did not recognize this spot as a long-standing nevus. The area was scrubbed vigorously with an alcohol swab, which did not change the pigment. Clinically the lesion was concerning for an atypical nevus. Dermoscopic examination showed an unusual pattern with pigment deposition in ridges and on furrows.

Erythematous Scaly Papules on the Shins and Calves

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

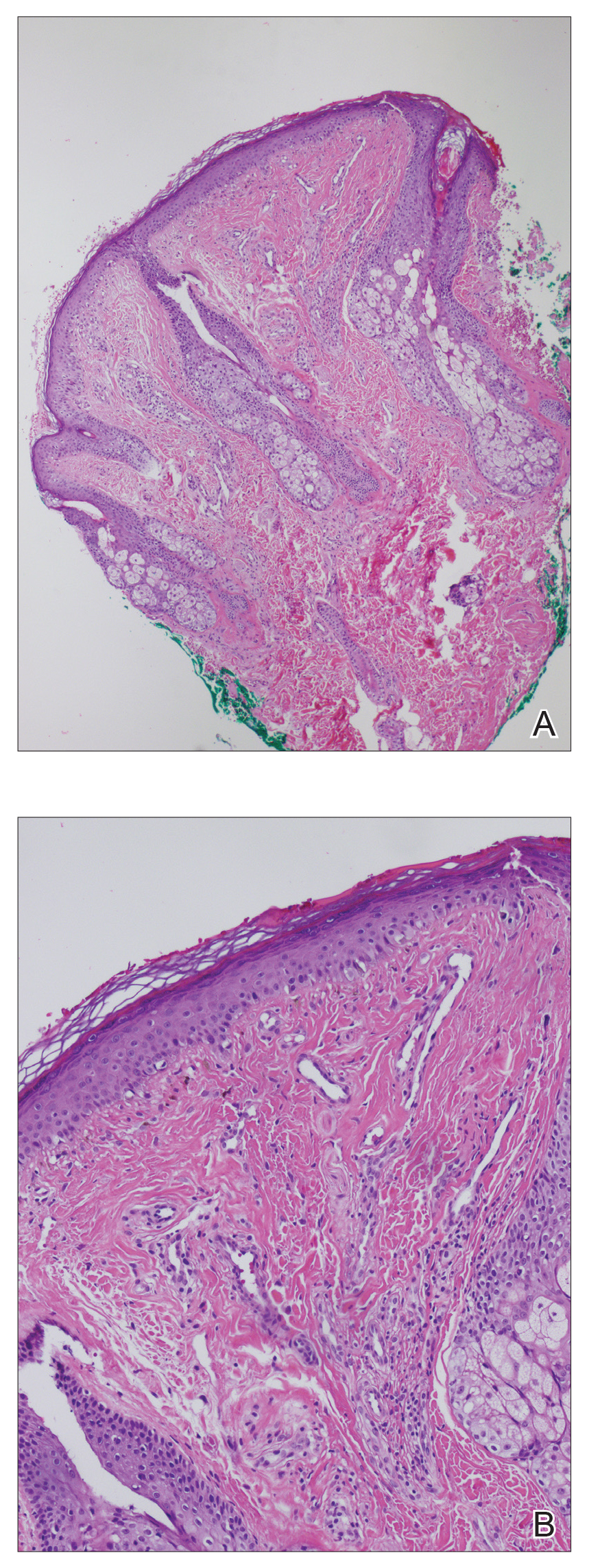

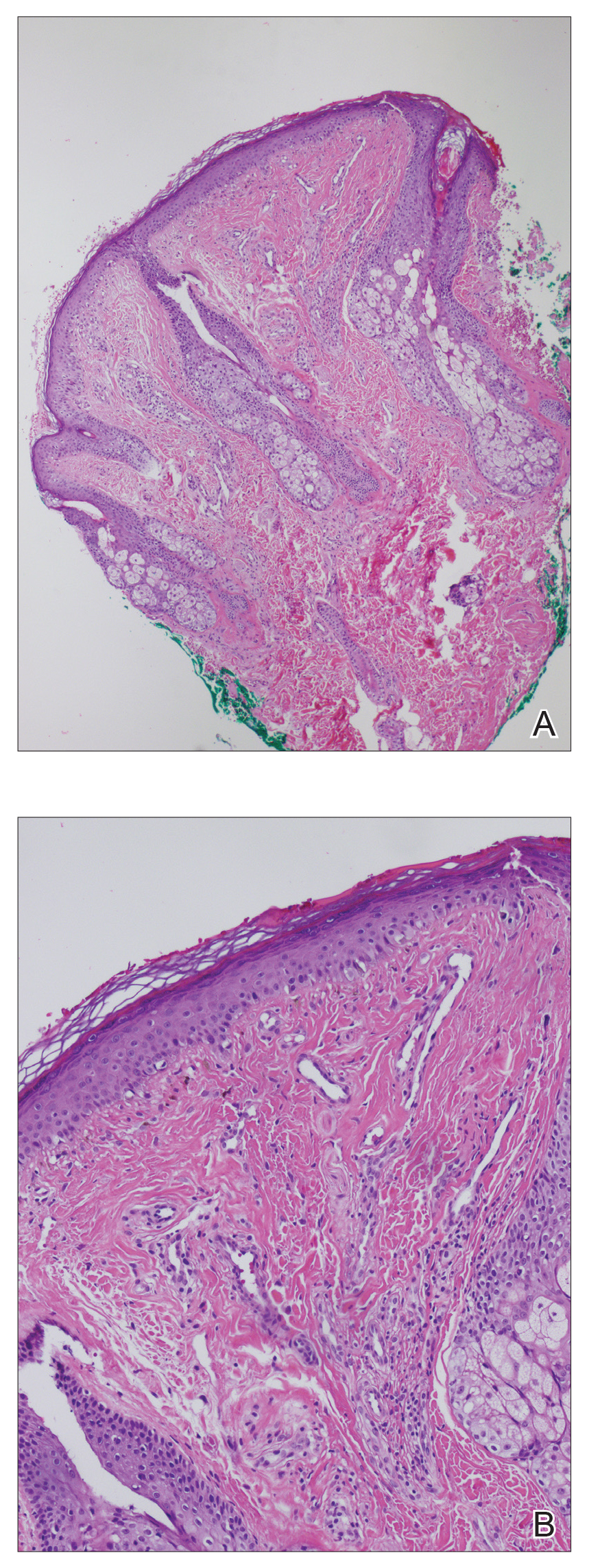

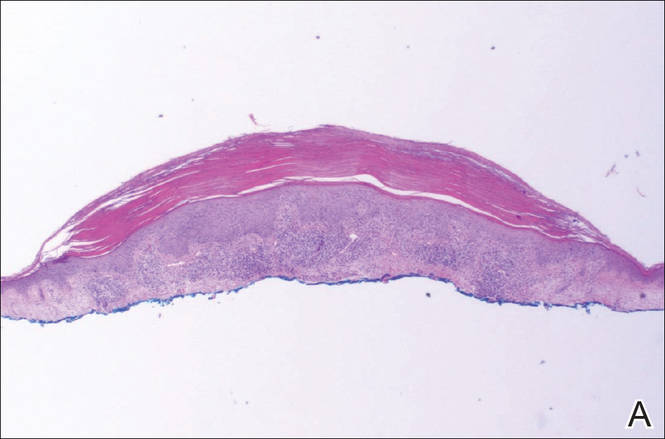

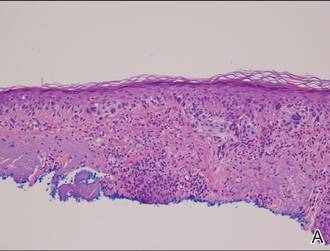

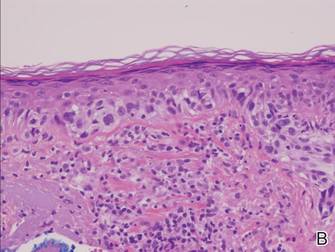

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Jawline

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

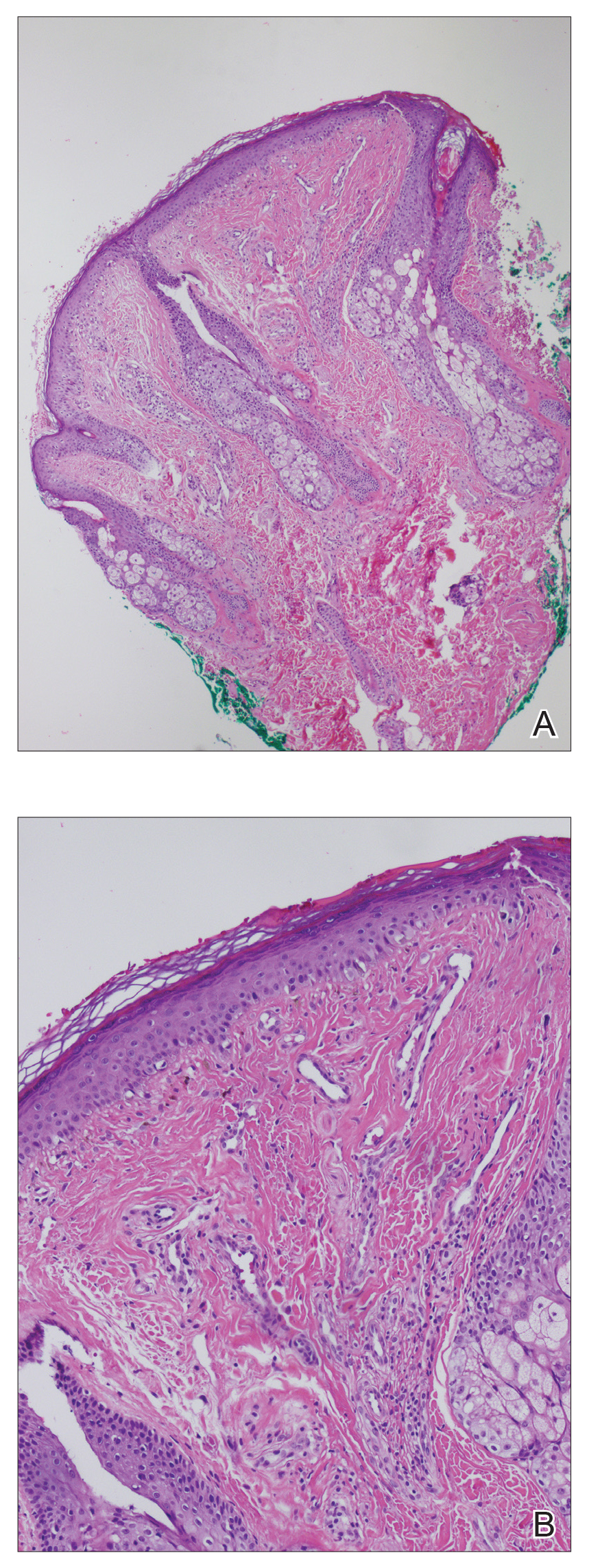

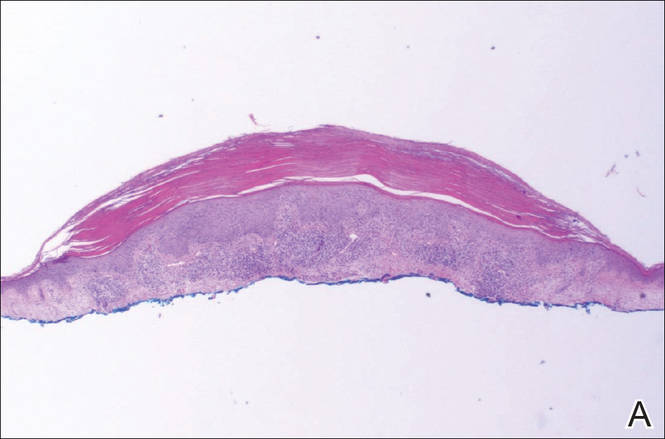

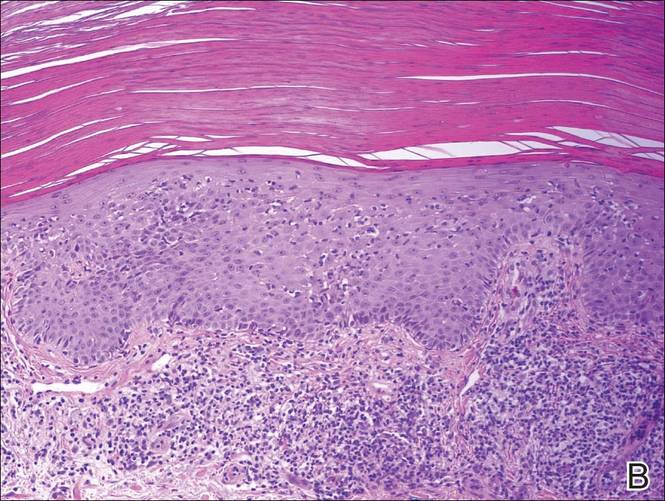

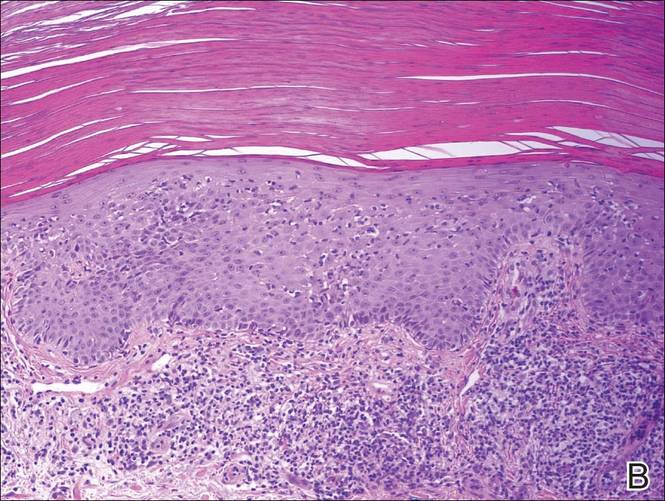

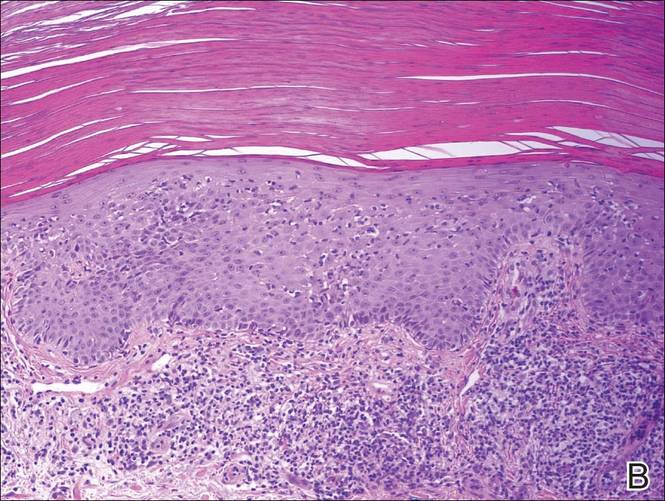

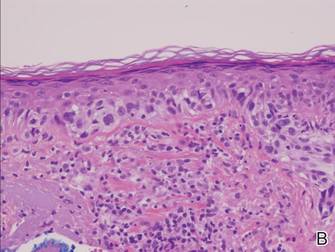

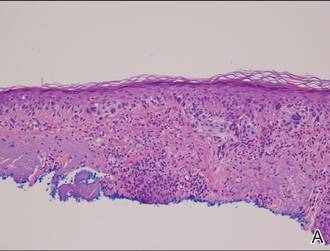

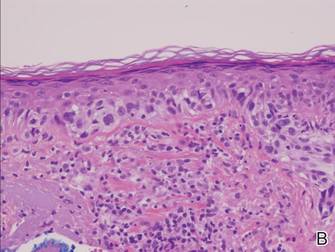

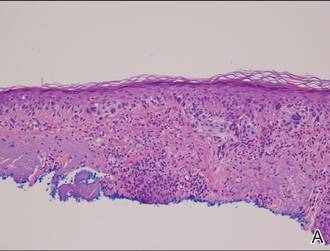

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

Atypia of the individual melanocytes.

Melan-A stain highlighted the density and confluence of melanocytes within the epidermis.

Three scouting punch biopsies were performed along the periphery of the lesion.

A 70-year-old white woman with a history of basal cell carcinoma presented with a 2.7×1.9-cm ill-defined, erythematous, scaly patch along the left side of the jawline. Ten months prior to presentation, the lesion appeared as a grayish macule that was clinically diagnosed as a pigmented actinic keratosis and was treated with cryotherapy with resolution noted at 6-month follow-up. Differential diagnosis of the current lesion included actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A shave biopsy was performed.

Tender Thumbnail Papule

The Diagnosis: Myxoid Cyst

Myxoid cysts, often called ganglion cysts or mucous cysts, are smooth translucent nodules that arise between the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal joint and proximal nail fold.1 Lesions often have an associated distal depression or groove on the affected fingernail and typically appear on the middle and index fingers between the fourth and seventh decades of life.2,3 Acute lesions may present as tender nodules, whereas gradually developing lesions tend to be painless.3 Trauma to the distal interphalangeal joint, degenerative processes, and osteoarthritis may increase hyaluronic acid production and allow synovial fluid to escape the joint space, accumulating in the surrounding tissue. Subungual localization of a mucous cyst is rare and may be difficult to diagnose.4 The differential diagnosis includes benign and malignant tumors such as periungual fibroma, glomus tumor, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma.5 Our patient declined treatment with cryotherapy or intralesional steroid injection and drainage. He was referred to the orthopedic surgery department for surgical removal of the cyst and imaging studies. Radiographs of the right thumb revealed severe osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint, demonstrating the association of digital mucous cysts.

1. Karrer S, Hohenleutner U, Szeimies RM, et al. Treatment of a digital mucous cyst with a carbon dioxide laser. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:224-225.

2. Brown RE, Zook EG, Russell RC. Fingernail deformities secondary to ganglions of the distal interphalangeal joint (mucous cysts). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:718-725.

3. de Berker D, Goettman S, Baran R. Subungual myxoid cysts: clinical manifestations and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:394-398.

4. Lin YC, Wu TH, Scher RK. Nail changes and association of osteoarthritis in digital myxoid cyst. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

5. Kivanc-Altunay I, Kumbasar E, Gokdemir G. Unusual localization of multiple myxoid (mucous) cysts of toes. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:23.

The Diagnosis: Myxoid Cyst

Myxoid cysts, often called ganglion cysts or mucous cysts, are smooth translucent nodules that arise between the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal joint and proximal nail fold.1 Lesions often have an associated distal depression or groove on the affected fingernail and typically appear on the middle and index fingers between the fourth and seventh decades of life.2,3 Acute lesions may present as tender nodules, whereas gradually developing lesions tend to be painless.3 Trauma to the distal interphalangeal joint, degenerative processes, and osteoarthritis may increase hyaluronic acid production and allow synovial fluid to escape the joint space, accumulating in the surrounding tissue. Subungual localization of a mucous cyst is rare and may be difficult to diagnose.4 The differential diagnosis includes benign and malignant tumors such as periungual fibroma, glomus tumor, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma.5 Our patient declined treatment with cryotherapy or intralesional steroid injection and drainage. He was referred to the orthopedic surgery department for surgical removal of the cyst and imaging studies. Radiographs of the right thumb revealed severe osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint, demonstrating the association of digital mucous cysts.

The Diagnosis: Myxoid Cyst

Myxoid cysts, often called ganglion cysts or mucous cysts, are smooth translucent nodules that arise between the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal joint and proximal nail fold.1 Lesions often have an associated distal depression or groove on the affected fingernail and typically appear on the middle and index fingers between the fourth and seventh decades of life.2,3 Acute lesions may present as tender nodules, whereas gradually developing lesions tend to be painless.3 Trauma to the distal interphalangeal joint, degenerative processes, and osteoarthritis may increase hyaluronic acid production and allow synovial fluid to escape the joint space, accumulating in the surrounding tissue. Subungual localization of a mucous cyst is rare and may be difficult to diagnose.4 The differential diagnosis includes benign and malignant tumors such as periungual fibroma, glomus tumor, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma.5 Our patient declined treatment with cryotherapy or intralesional steroid injection and drainage. He was referred to the orthopedic surgery department for surgical removal of the cyst and imaging studies. Radiographs of the right thumb revealed severe osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal joint, demonstrating the association of digital mucous cysts.

1. Karrer S, Hohenleutner U, Szeimies RM, et al. Treatment of a digital mucous cyst with a carbon dioxide laser. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:224-225.

2. Brown RE, Zook EG, Russell RC. Fingernail deformities secondary to ganglions of the distal interphalangeal joint (mucous cysts). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:718-725.

3. de Berker D, Goettman S, Baran R. Subungual myxoid cysts: clinical manifestations and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:394-398.

4. Lin YC, Wu TH, Scher RK. Nail changes and association of osteoarthritis in digital myxoid cyst. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

5. Kivanc-Altunay I, Kumbasar E, Gokdemir G. Unusual localization of multiple myxoid (mucous) cysts of toes. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:23.

1. Karrer S, Hohenleutner U, Szeimies RM, et al. Treatment of a digital mucous cyst with a carbon dioxide laser. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:224-225.

2. Brown RE, Zook EG, Russell RC. Fingernail deformities secondary to ganglions of the distal interphalangeal joint (mucous cysts). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:718-725.

3. de Berker D, Goettman S, Baran R. Subungual myxoid cysts: clinical manifestations and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:394-398.

4. Lin YC, Wu TH, Scher RK. Nail changes and association of osteoarthritis in digital myxoid cyst. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

5. Kivanc-Altunay I, Kumbasar E, Gokdemir G. Unusual localization of multiple myxoid (mucous) cysts of toes. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:23.

A 71-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with mild tenderness and disfigurement of the right thumbnail of 6 months’ duration. The patient reported trauma to his thumb from closing a window on it during the time between onset of symptoms and presentation to the dermatology clinic. On physical examination the right thumbnail was atrophic with a flesh-colored papule involving the proximal nail bed. The nail plate overlying the papule was thinned by the underlying growth and there was a linear groove extending from the papule to the end of the nail. A biopsy was recommended for diagnosis and lidocaine was injected into the proximal aspect of the nail fold for local anesthesia. The lidocaine filled the papule, resulting in increased subungual pressure that caused the lesion to rupture through the nail plate, extruding a clear mucoid substance.

Encephalopathy despite thiamine repletion during alcohol withdrawal

Managing a patient with chronic alcohol abuse who is beginning to withdraw is a situation in which to expect the unexpected.

A 61-year-old man with a 40-year history of alcohol abuse was admitted to the hospital after presenting with a 6-month history of weakness and increasing frequency of falls, as well as a 2-day history of myalgias and fatigue. He had anorexia and chronic diarrhea, and he reported an unintentional 100-lb weight loss over the past year. He consumed at least three to five alcoholic drinks daily, including a daily “eye-opener,” and his diet was essentially devoid of meat, bread, fruits, and vegetables. His last drink had been on the morning of admission.

On physical examination, his vital signs were notable for marked orthostatic hypotension. He had angular cheilitis, an erythematous, scaly facial rash, and poorly healing severe sunburn on the dorsal surface of the left forearm, acquired 1 month earlier after minimal sun exposure while driving his car (Figure 1).

The neurologic examination noted decreased sensation in a stocking distribution, reduced proprioception in both great toes, and an intention tremor. His upper extremities were slightly hyperreflexic, he had down-going toes, he did not have clonus, and his gait was wide-based.

Laboratory results were notable for mild anemia, with an elevated mean corpuscular volume of 109.2 fL and a normal thyrotropin level. Urinalysis and urine culture were normal. Stool testing for Clostridium difficile toxin was negative. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable.