User login

How academic medical centers can build a sustainable economic clinical model

Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) have been given unique responsibilities to care for patients, educate future clinicians, and bring innovative research to the bedside. Over the last few decades, this tripartite mission has served the United States well, and payers (Federal, State, and commercial) have been willing to underwrite these missions with overt and covert financial subsidies. As cost containment efforts have escalated, the traditional business model of AMCs has been challenged. In this issue, Dr Anil Rustgi and I offer some insights into how AMCs must alter their business model to be sustainable in our new world of accountable care, cost containment, and clinical integration.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Academic medicine, including academic gastrointestinal (GI) medicine, has been founded and has flourished on the tripartite missions of research, teaching/education, and patient care. Academic medical centers (AMCs) have unique and historical responsibilities to translate research discoveries into innovative patient care and train the next generation of physicians in both medical sciences and health care delivery. In this era of fiscal constraint, there are current and anticipated challenges, which are triggered by reductions in the National Institutes of Health budget, implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), federal budget constraints ("Sequestration"), and the increasingly complex relationship between health care systems, insurance companies, regulatory entities, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical device companies. In direct and indirect fashions, these events will force leaders of academic GI divisions to reexamine the business infrastructures of their division\'s clinical practice. Such plasticity and adaptation will serve to invigorate academic medicine and its multifaceted roles. The financial and clinical pressures emerging as a result of the current wave of health care reform have been defined in previous articles within this section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, including descriptions of the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice,"1 general descriptions of health care reform,2,3 and specific pressures on AMCs.4

Sources of revenue for academic gastrointestinal divisions

Changes to the business model of academic GI divisions must remain consistent with the deep-rooted tripartite commitments of AMCs. One of the greatest challenges facing many division chiefs today is to remain true to research and teaching missions when their sources of revenue becomes increasingly dependent on clinical productivity. Currently, sources of revenue for a GI division include research grant support, philanthropy, partnerships with industry, and clinical revenue. In many AMCs, clinical revenue now exceeds all other sources of funding, a fact that underscores the importance of building a robust and sustainable clinical enterprise.

Research revenue

Research grant support emanates traditionally from the National Institutes of Health, but there are other sources as well, including but not restricted to federal agencies (eg, Department of Defense, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control, among others), national specialty societies (eg, American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of GI Endoscopy, American College of Gastroenterology), and private foundations (eg, Crohn\'s and Colitis Foundation of America). Grant support tends to target different stages of career: trainees, those making the transition from a mentored phase to an independent phase, and established investigators.

Philanthropy and industry partnerships

Academic GI divisions rely on contributions from philanthropy and partnerships with industry, but these are not fixed amounts in a predictable fashion. Depending on the amount of philanthropy, donations may result in endowments that are interest-bearing (eg, endowed chairs for faculty or for research/education) or gift accounts ("spend as you go"). Partnerships with industry, both pharmaceutical and medical device, have been and remain an important source of support for research, education, and training. New regulations within the PPACA have altered these relationships substantially. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act, Section 6002 of PPACA, was created to provide transparency in physicians\' interactions with medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological industries. As of August 1, 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid requires drug and device manufacturers to track (at a provider level) payments and other transfers of value exceeding $10 (single instance) or $100 (aggregate during 1 year) provided to physicians and teaching hospitals, with payments posted on a public Web site. This topic is beyond the scope of this article but is an important area that should be understood by all gastroenterologists.5

Clinical revenue

For many AMCs, clinical revenue has become the single largest source of funding for the School of Medicine. GI revenues are generated by professional billings from office and hospital-based consultations, management of established patients, and endoscopic procedures performed in a variety of practice settings (inpatient endoscopy units, hospital outpatient departments, and ambulatory endoscopy centers [AECs]). Technical revenues (monies paid to facilities as opposed to the professional fees paid to providers) associated with procedures (usually much larger than professional fees on a per service unit basis) almost always track to hospitals because many of the procedures are hospital-based or performed in hospital-funded (and owned) AECs.

Progressive GI divisions often have developed their own AECs and are able to model a financial partnership with their AMCs that combines professional and technical reimbursement in a collaborative manner. Gastroenterology benefits also from "niche" areas of health care delivery in AMCs, namely transplant hepatology, interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, oncology, and esophagology.

Some of the ability to augment GI programs has evolved from new models of revenue sharing between hospital systems and GI divisions that are based on income from AECs plus other "technical fees" such as revenue from biologic medication infusion. Technical fees (also called facility fees) are the monies paid to endoscopy labs, clinics, or hospitals in distinction to the "professional fee," which is reimbursement to providers for their medical services. Downstream revenue attributable to transplant hepatology has helped to redefine the close relationship between GI divisions and hospitals, where applicable. Practice ownership in AECs has helped transform GI health care economics not only in community-based gastroenterology but also in academic gastroenterology. Where AMCs adopt practice models that parallel community practice, such as the development of AECs, there is convergence of financial and clinical goals between AMCs and community gastroenterology. This comes during a time when community practices are increasingly concerned about long-term security as independent practices especially as health care reform progresses. This combination of factors has led some AMCs to develop closer alliances with community GI practices in their region.

There are several models of cooperation between academic GI faculty and community practices. The "loosest" affiliation occurs when the AMC creates a facilitated referral process targeted to key community practices in return for lending the AMC "brand" to the practice. Closer partnerships might include a shared inpatient service, professional service agreement, co-management of clinical service lines, or joint-venture arrangements to build and manage AECs.

A number of practices have realized advantages of full merger and have negotiated a pathway to becoming clinical faculty members. The AMC typically provides the shared electronic medical record (EMR) and assumes full responsibility for practice operations and office staff. With this arrangement, practices typically enjoy higher managed care rates, immediate buyout of hard assets (such as an AEC and infusion services), and the professional fulfillment attendant to becoming an academic clinician and educator.6

Emerging economic pressures

Training and education for GI fellows continue to be of paramount importance to GI divisions. There are more than 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited GI fellowships across the United States, but the number of fellows emerging from 3-year fellowship training has remained relatively constant during the last 10-15 years. Fellowship has been modified by the integration of advanced (fourth year) fellowships that align with the niche areas of gastroenterology: transplant hepatology (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited), interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel diseases, esophagology/motility, and potentially oncology. Typically, the mix of financial support for GI fellowship training, a not insignificant cost for academic gastroenterology, involves National Institutes of Health T32 training grants (for the research component of GI fellowship), Graduate Medical Education support, and clinical revenue (directly from the GI budget and indirectly from the hospital budget). Occasionally, unrestricted industry support may help, especially in the advanced GI fellowships.

Traditionally, AMCs have been able to command higher managed care rates compared with nonacademic hospital systems to account for time related to clinical care delivered by an attending physician as he or she teaches medical students, residents, and fellows in the art and science of medicine or technical skills related to endoscopic procedures or surgery. This situation is changing rapidly as cost pressures force both state and commercial payers to bring increasing scrutiny to total cost of care negotiations.

Currently, an overriding concern for purchasers of health care is cost. Purchasers of health care are increasingly carving out narrowed provider networks that are based largely on cost, a situation that may leave some AMCs excluded from large groups of patients.7

We are witnessing an extraordinary downward pressure on reimbursement for all medical services from every type of payer. There also is an emerging shift to value-based reimbursement where revenue for medical services is linked to patient outcomes. As this trend continues, AMCs may need to compete directly with integrated delivery networks (IDNs) that are emerging as an increasingly dominant care delivery model characterized by close clinical and financial linkage among primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary services1 in areas where this is relevant.

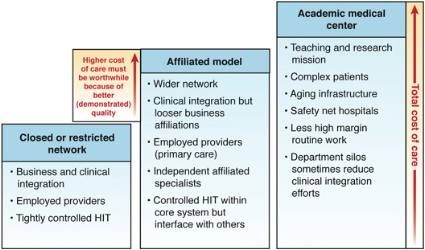

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of the total cost of care among three major types of IDNs. IDNs that are "closed," meaning all aspects of care are contained within a single financial umbrella (eg, Kaiser Permanente), control costs by owning and aggressively managing all aspects of care delivery (primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary facilities). They usually have an enterprise-wide EMR that simplifies transmission of information (1 patient, 1 chart). Few patients are referred outside the IDN, and the total cost of care for a purchaser of health benefits can be low in comparison with other regional delivery networks (Figure 1).

Another IDN model comprises partially owned (or employed) providers and hospitals but affiliations with independent specialty groups. The fact that all providers are not employed and often have different EMRs compared with the core hospital system adds additional costs. The third type of IDN includes AMCs that increase costs compared with other IDNs because of the fundamental missions of research and teaching. Despite the importance of their tripartite missions, some AMCs are being forced to compete for market share with well-managed closed network IDNs. Consequently, increased costs must be balanced by clearly defined added value that would be important to purchasers and individual patients alike.

Finally, as state and federal exchanges mature (2014 and beyond), the health care purchasing market will shift from a "wholesale" to a "retail" viewpoint where decisions about joining health systems will increasingly be at the level of individual patients. Exchanges organize price and quality information about regional provider networks in a manner that allows individuals to choose their providers with greater price and quality transparency. If AMCs in these mature markets are out of network or too costly, patient co-pays and deductibles will preclude large segments of patients from seeking their care at those centers.

In regions of the country where purchasers have organized to negotiate health care contracts, narrow provider networks and highly managed referral patterns have specifically excluded some well-known (but expensive) tertiary and quaternary referral centers. Examples of AMCs that have been excluded from significant provider networks can be found already in mature managed care markets such as California, Minnesota, and Massachusetts. Dr Martin Brotman articulated these concepts in unambiguous terms during his Presidential Plenary presentation at Digestive Disease Week® 2013. (An interview with Dr Brotman can be accessed on YouTube, available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hquW3NZtnxM).

Five steps that will help AMCs survive

Because of the changes we have defined, what are the key steps that AMC GI divisions can implement now to help build a sustainable practice model? There are five basic suggested steps that may be useful.

Focus on patient-centered care

As health care delivery moves to a patient-centered model, demands on faculty have changed. Clinical faculty members now are expected to be accessible to patients, complete medical records promptly, and follow lab and biopsy results in a timely manner. Federal and commercial payers both are developing robust Web sites that distinguish quality and cost at a provider level. This unprecedented focus on transparency of practice will affect all gastroenterologists equally, no matter what their practice setting.GI divisions must respond to these changes by building a robust clinical infrastructure to help support academic faculty, while allowing time for research and educational activities combined with an information technology platform that facilitates collection of performance and value metrics. Many AMCs structure care around specific patient conditions and have developed Centers of Excellence that provide cutting edge, coordinated care for populations of patients (inflammatory bowel disease, foregut disorders, hepatology, for example).

Enhance clinical efficiency

Economic pressure on AMCs is growing rapidly, so division funds will increasingly be tied directly to clinical productivity of faculty. GI divisions can develop or augment efficient clinical enterprises by focusing on easy and rapid patient access, development of clinical service lines that distinguish faculty from community physicians, efficient endoscopy practices, and other measurable activities that enhance and expand clinical service. Much of this redesign will require joint investment shared by GI divisions and their hospital systems.

Align incentives

AMCs typically have multiple distinct entities such as a school of medicine, a health care delivery network, individual hospitals, a medical faculty practice, departments (eg, medicine, surgery), and individual divisions (eg, GI, renal, endocrine). By aligning incentives, maximizing the strengths and efficiencies of each entity, and developing a coordinated financial plan, AMCs can compete in regional markets. If AMCs are to succeed in the increasingly competitive health care market, there must be coordination and alignment at financial, governance, and operational levels in addition to the AMC working toward true clinical integration.

Operate at the speed of business

The pace of change at AMCs may be challenging. As we move to value-based reimbursement and note the emergence of large IDNs, barriers to clinical integration and financial alignment must be reduced swiftly. Aggregation of business processes, practice management, information transfer, and data collection and analysis all must be accomplished quickly. AMCs will meet this challenge with the type of intellectual tour de force we have witnessed during the last generation as applied to translational medical research. AMCs will lead in fields such as personalized medicine (pharmacogenomics, microbiome, cancer genetics), and through their clinical integration efforts they will emerge as leaders in coordinated population management as well.

Break down barriers between academic medical centers and community practice

American medicine has bifurcated care between AMCs that provide tertiary and quaternary care and community gastroenterology that provides primary and secondary care, although AMCs now are engaging in primary and secondary care as well. In a world where financial and outcome accountability for populations now will be paramount, cooperation along the entire spectrum of medical care will be needed. Traditional barriers between AMCs and community practices are beginning to fall as true integration of care emerges as a strategy for a sustainable IDN.

Academic gastroenterology: Looking forward

Academic gastroenterology comprises a unique blend of science and medicine. Certainly, there are deeply rooted traditions, many of which foster individual creativity and curiosity and provide a platform for diverse pathways and diversity. However, challenges exist, and open and transparent planning is necessary to meet and surmount these challenges. Successful AMCs will rise to these challenges.

References

1. Allen J.I. The road ahead. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 692-6.

2. Dorn S.D. Gastroenterology in a new era of accountability: Part 3 – accountable care organizations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:750-3.

3. Sheen E., Dorn S.D., Brill J.V., et al. Healthcare reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

4. Taylor I.L., Clinchy R.M. The Affordable Care Act and academic medical centers. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 828-30.

5. American Gastroenterological Association. Update on the physician payment Sunshine Act Final Rule. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/journals-publications/news/update-on-the-physician-payment-sunshine-act-final-rule. Accessed June 23, 2013.

6. Fink J.N., Libby D.E. Integration without employment. Healthcare Financial Management 2012;66: 54-62.

7. Daly R. Narrow negotiations. Modern Healthcare May 6, 2013;14.

Dr. Rustgi is professor Division of Gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Dr. Allen is clinical chief of gastroenterology and hepatology and professor at the Yale School of Medicine. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) have been given unique responsibilities to care for patients, educate future clinicians, and bring innovative research to the bedside. Over the last few decades, this tripartite mission has served the United States well, and payers (Federal, State, and commercial) have been willing to underwrite these missions with overt and covert financial subsidies. As cost containment efforts have escalated, the traditional business model of AMCs has been challenged. In this issue, Dr Anil Rustgi and I offer some insights into how AMCs must alter their business model to be sustainable in our new world of accountable care, cost containment, and clinical integration.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Academic medicine, including academic gastrointestinal (GI) medicine, has been founded and has flourished on the tripartite missions of research, teaching/education, and patient care. Academic medical centers (AMCs) have unique and historical responsibilities to translate research discoveries into innovative patient care and train the next generation of physicians in both medical sciences and health care delivery. In this era of fiscal constraint, there are current and anticipated challenges, which are triggered by reductions in the National Institutes of Health budget, implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), federal budget constraints ("Sequestration"), and the increasingly complex relationship between health care systems, insurance companies, regulatory entities, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical device companies. In direct and indirect fashions, these events will force leaders of academic GI divisions to reexamine the business infrastructures of their division\'s clinical practice. Such plasticity and adaptation will serve to invigorate academic medicine and its multifaceted roles. The financial and clinical pressures emerging as a result of the current wave of health care reform have been defined in previous articles within this section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, including descriptions of the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice,"1 general descriptions of health care reform,2,3 and specific pressures on AMCs.4

Sources of revenue for academic gastrointestinal divisions

Changes to the business model of academic GI divisions must remain consistent with the deep-rooted tripartite commitments of AMCs. One of the greatest challenges facing many division chiefs today is to remain true to research and teaching missions when their sources of revenue becomes increasingly dependent on clinical productivity. Currently, sources of revenue for a GI division include research grant support, philanthropy, partnerships with industry, and clinical revenue. In many AMCs, clinical revenue now exceeds all other sources of funding, a fact that underscores the importance of building a robust and sustainable clinical enterprise.

Research revenue

Research grant support emanates traditionally from the National Institutes of Health, but there are other sources as well, including but not restricted to federal agencies (eg, Department of Defense, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control, among others), national specialty societies (eg, American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of GI Endoscopy, American College of Gastroenterology), and private foundations (eg, Crohn\'s and Colitis Foundation of America). Grant support tends to target different stages of career: trainees, those making the transition from a mentored phase to an independent phase, and established investigators.

Philanthropy and industry partnerships

Academic GI divisions rely on contributions from philanthropy and partnerships with industry, but these are not fixed amounts in a predictable fashion. Depending on the amount of philanthropy, donations may result in endowments that are interest-bearing (eg, endowed chairs for faculty or for research/education) or gift accounts ("spend as you go"). Partnerships with industry, both pharmaceutical and medical device, have been and remain an important source of support for research, education, and training. New regulations within the PPACA have altered these relationships substantially. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act, Section 6002 of PPACA, was created to provide transparency in physicians\' interactions with medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological industries. As of August 1, 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid requires drug and device manufacturers to track (at a provider level) payments and other transfers of value exceeding $10 (single instance) or $100 (aggregate during 1 year) provided to physicians and teaching hospitals, with payments posted on a public Web site. This topic is beyond the scope of this article but is an important area that should be understood by all gastroenterologists.5

Clinical revenue

For many AMCs, clinical revenue has become the single largest source of funding for the School of Medicine. GI revenues are generated by professional billings from office and hospital-based consultations, management of established patients, and endoscopic procedures performed in a variety of practice settings (inpatient endoscopy units, hospital outpatient departments, and ambulatory endoscopy centers [AECs]). Technical revenues (monies paid to facilities as opposed to the professional fees paid to providers) associated with procedures (usually much larger than professional fees on a per service unit basis) almost always track to hospitals because many of the procedures are hospital-based or performed in hospital-funded (and owned) AECs.

Progressive GI divisions often have developed their own AECs and are able to model a financial partnership with their AMCs that combines professional and technical reimbursement in a collaborative manner. Gastroenterology benefits also from "niche" areas of health care delivery in AMCs, namely transplant hepatology, interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, oncology, and esophagology.

Some of the ability to augment GI programs has evolved from new models of revenue sharing between hospital systems and GI divisions that are based on income from AECs plus other "technical fees" such as revenue from biologic medication infusion. Technical fees (also called facility fees) are the monies paid to endoscopy labs, clinics, or hospitals in distinction to the "professional fee," which is reimbursement to providers for their medical services. Downstream revenue attributable to transplant hepatology has helped to redefine the close relationship between GI divisions and hospitals, where applicable. Practice ownership in AECs has helped transform GI health care economics not only in community-based gastroenterology but also in academic gastroenterology. Where AMCs adopt practice models that parallel community practice, such as the development of AECs, there is convergence of financial and clinical goals between AMCs and community gastroenterology. This comes during a time when community practices are increasingly concerned about long-term security as independent practices especially as health care reform progresses. This combination of factors has led some AMCs to develop closer alliances with community GI practices in their region.

There are several models of cooperation between academic GI faculty and community practices. The "loosest" affiliation occurs when the AMC creates a facilitated referral process targeted to key community practices in return for lending the AMC "brand" to the practice. Closer partnerships might include a shared inpatient service, professional service agreement, co-management of clinical service lines, or joint-venture arrangements to build and manage AECs.

A number of practices have realized advantages of full merger and have negotiated a pathway to becoming clinical faculty members. The AMC typically provides the shared electronic medical record (EMR) and assumes full responsibility for practice operations and office staff. With this arrangement, practices typically enjoy higher managed care rates, immediate buyout of hard assets (such as an AEC and infusion services), and the professional fulfillment attendant to becoming an academic clinician and educator.6

Emerging economic pressures

Training and education for GI fellows continue to be of paramount importance to GI divisions. There are more than 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited GI fellowships across the United States, but the number of fellows emerging from 3-year fellowship training has remained relatively constant during the last 10-15 years. Fellowship has been modified by the integration of advanced (fourth year) fellowships that align with the niche areas of gastroenterology: transplant hepatology (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited), interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel diseases, esophagology/motility, and potentially oncology. Typically, the mix of financial support for GI fellowship training, a not insignificant cost for academic gastroenterology, involves National Institutes of Health T32 training grants (for the research component of GI fellowship), Graduate Medical Education support, and clinical revenue (directly from the GI budget and indirectly from the hospital budget). Occasionally, unrestricted industry support may help, especially in the advanced GI fellowships.

Traditionally, AMCs have been able to command higher managed care rates compared with nonacademic hospital systems to account for time related to clinical care delivered by an attending physician as he or she teaches medical students, residents, and fellows in the art and science of medicine or technical skills related to endoscopic procedures or surgery. This situation is changing rapidly as cost pressures force both state and commercial payers to bring increasing scrutiny to total cost of care negotiations.

Currently, an overriding concern for purchasers of health care is cost. Purchasers of health care are increasingly carving out narrowed provider networks that are based largely on cost, a situation that may leave some AMCs excluded from large groups of patients.7

We are witnessing an extraordinary downward pressure on reimbursement for all medical services from every type of payer. There also is an emerging shift to value-based reimbursement where revenue for medical services is linked to patient outcomes. As this trend continues, AMCs may need to compete directly with integrated delivery networks (IDNs) that are emerging as an increasingly dominant care delivery model characterized by close clinical and financial linkage among primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary services1 in areas where this is relevant.

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of the total cost of care among three major types of IDNs. IDNs that are "closed," meaning all aspects of care are contained within a single financial umbrella (eg, Kaiser Permanente), control costs by owning and aggressively managing all aspects of care delivery (primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary facilities). They usually have an enterprise-wide EMR that simplifies transmission of information (1 patient, 1 chart). Few patients are referred outside the IDN, and the total cost of care for a purchaser of health benefits can be low in comparison with other regional delivery networks (Figure 1).

Another IDN model comprises partially owned (or employed) providers and hospitals but affiliations with independent specialty groups. The fact that all providers are not employed and often have different EMRs compared with the core hospital system adds additional costs. The third type of IDN includes AMCs that increase costs compared with other IDNs because of the fundamental missions of research and teaching. Despite the importance of their tripartite missions, some AMCs are being forced to compete for market share with well-managed closed network IDNs. Consequently, increased costs must be balanced by clearly defined added value that would be important to purchasers and individual patients alike.

Finally, as state and federal exchanges mature (2014 and beyond), the health care purchasing market will shift from a "wholesale" to a "retail" viewpoint where decisions about joining health systems will increasingly be at the level of individual patients. Exchanges organize price and quality information about regional provider networks in a manner that allows individuals to choose their providers with greater price and quality transparency. If AMCs in these mature markets are out of network or too costly, patient co-pays and deductibles will preclude large segments of patients from seeking their care at those centers.

In regions of the country where purchasers have organized to negotiate health care contracts, narrow provider networks and highly managed referral patterns have specifically excluded some well-known (but expensive) tertiary and quaternary referral centers. Examples of AMCs that have been excluded from significant provider networks can be found already in mature managed care markets such as California, Minnesota, and Massachusetts. Dr Martin Brotman articulated these concepts in unambiguous terms during his Presidential Plenary presentation at Digestive Disease Week® 2013. (An interview with Dr Brotman can be accessed on YouTube, available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hquW3NZtnxM).

Five steps that will help AMCs survive

Because of the changes we have defined, what are the key steps that AMC GI divisions can implement now to help build a sustainable practice model? There are five basic suggested steps that may be useful.

Focus on patient-centered care

As health care delivery moves to a patient-centered model, demands on faculty have changed. Clinical faculty members now are expected to be accessible to patients, complete medical records promptly, and follow lab and biopsy results in a timely manner. Federal and commercial payers both are developing robust Web sites that distinguish quality and cost at a provider level. This unprecedented focus on transparency of practice will affect all gastroenterologists equally, no matter what their practice setting.GI divisions must respond to these changes by building a robust clinical infrastructure to help support academic faculty, while allowing time for research and educational activities combined with an information technology platform that facilitates collection of performance and value metrics. Many AMCs structure care around specific patient conditions and have developed Centers of Excellence that provide cutting edge, coordinated care for populations of patients (inflammatory bowel disease, foregut disorders, hepatology, for example).

Enhance clinical efficiency

Economic pressure on AMCs is growing rapidly, so division funds will increasingly be tied directly to clinical productivity of faculty. GI divisions can develop or augment efficient clinical enterprises by focusing on easy and rapid patient access, development of clinical service lines that distinguish faculty from community physicians, efficient endoscopy practices, and other measurable activities that enhance and expand clinical service. Much of this redesign will require joint investment shared by GI divisions and their hospital systems.

Align incentives

AMCs typically have multiple distinct entities such as a school of medicine, a health care delivery network, individual hospitals, a medical faculty practice, departments (eg, medicine, surgery), and individual divisions (eg, GI, renal, endocrine). By aligning incentives, maximizing the strengths and efficiencies of each entity, and developing a coordinated financial plan, AMCs can compete in regional markets. If AMCs are to succeed in the increasingly competitive health care market, there must be coordination and alignment at financial, governance, and operational levels in addition to the AMC working toward true clinical integration.

Operate at the speed of business

The pace of change at AMCs may be challenging. As we move to value-based reimbursement and note the emergence of large IDNs, barriers to clinical integration and financial alignment must be reduced swiftly. Aggregation of business processes, practice management, information transfer, and data collection and analysis all must be accomplished quickly. AMCs will meet this challenge with the type of intellectual tour de force we have witnessed during the last generation as applied to translational medical research. AMCs will lead in fields such as personalized medicine (pharmacogenomics, microbiome, cancer genetics), and through their clinical integration efforts they will emerge as leaders in coordinated population management as well.

Break down barriers between academic medical centers and community practice

American medicine has bifurcated care between AMCs that provide tertiary and quaternary care and community gastroenterology that provides primary and secondary care, although AMCs now are engaging in primary and secondary care as well. In a world where financial and outcome accountability for populations now will be paramount, cooperation along the entire spectrum of medical care will be needed. Traditional barriers between AMCs and community practices are beginning to fall as true integration of care emerges as a strategy for a sustainable IDN.

Academic gastroenterology: Looking forward

Academic gastroenterology comprises a unique blend of science and medicine. Certainly, there are deeply rooted traditions, many of which foster individual creativity and curiosity and provide a platform for diverse pathways and diversity. However, challenges exist, and open and transparent planning is necessary to meet and surmount these challenges. Successful AMCs will rise to these challenges.

References

1. Allen J.I. The road ahead. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 692-6.

2. Dorn S.D. Gastroenterology in a new era of accountability: Part 3 – accountable care organizations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:750-3.

3. Sheen E., Dorn S.D., Brill J.V., et al. Healthcare reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

4. Taylor I.L., Clinchy R.M. The Affordable Care Act and academic medical centers. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 828-30.

5. American Gastroenterological Association. Update on the physician payment Sunshine Act Final Rule. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/journals-publications/news/update-on-the-physician-payment-sunshine-act-final-rule. Accessed June 23, 2013.

6. Fink J.N., Libby D.E. Integration without employment. Healthcare Financial Management 2012;66: 54-62.

7. Daly R. Narrow negotiations. Modern Healthcare May 6, 2013;14.

Dr. Rustgi is professor Division of Gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Dr. Allen is clinical chief of gastroenterology and hepatology and professor at the Yale School of Medicine. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) have been given unique responsibilities to care for patients, educate future clinicians, and bring innovative research to the bedside. Over the last few decades, this tripartite mission has served the United States well, and payers (Federal, State, and commercial) have been willing to underwrite these missions with overt and covert financial subsidies. As cost containment efforts have escalated, the traditional business model of AMCs has been challenged. In this issue, Dr Anil Rustgi and I offer some insights into how AMCs must alter their business model to be sustainable in our new world of accountable care, cost containment, and clinical integration.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Academic medicine, including academic gastrointestinal (GI) medicine, has been founded and has flourished on the tripartite missions of research, teaching/education, and patient care. Academic medical centers (AMCs) have unique and historical responsibilities to translate research discoveries into innovative patient care and train the next generation of physicians in both medical sciences and health care delivery. In this era of fiscal constraint, there are current and anticipated challenges, which are triggered by reductions in the National Institutes of Health budget, implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), federal budget constraints ("Sequestration"), and the increasingly complex relationship between health care systems, insurance companies, regulatory entities, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical device companies. In direct and indirect fashions, these events will force leaders of academic GI divisions to reexamine the business infrastructures of their division\'s clinical practice. Such plasticity and adaptation will serve to invigorate academic medicine and its multifaceted roles. The financial and clinical pressures emerging as a result of the current wave of health care reform have been defined in previous articles within this section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, including descriptions of the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice,"1 general descriptions of health care reform,2,3 and specific pressures on AMCs.4

Sources of revenue for academic gastrointestinal divisions

Changes to the business model of academic GI divisions must remain consistent with the deep-rooted tripartite commitments of AMCs. One of the greatest challenges facing many division chiefs today is to remain true to research and teaching missions when their sources of revenue becomes increasingly dependent on clinical productivity. Currently, sources of revenue for a GI division include research grant support, philanthropy, partnerships with industry, and clinical revenue. In many AMCs, clinical revenue now exceeds all other sources of funding, a fact that underscores the importance of building a robust and sustainable clinical enterprise.

Research revenue

Research grant support emanates traditionally from the National Institutes of Health, but there are other sources as well, including but not restricted to federal agencies (eg, Department of Defense, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control, among others), national specialty societies (eg, American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of GI Endoscopy, American College of Gastroenterology), and private foundations (eg, Crohn\'s and Colitis Foundation of America). Grant support tends to target different stages of career: trainees, those making the transition from a mentored phase to an independent phase, and established investigators.

Philanthropy and industry partnerships

Academic GI divisions rely on contributions from philanthropy and partnerships with industry, but these are not fixed amounts in a predictable fashion. Depending on the amount of philanthropy, donations may result in endowments that are interest-bearing (eg, endowed chairs for faculty or for research/education) or gift accounts ("spend as you go"). Partnerships with industry, both pharmaceutical and medical device, have been and remain an important source of support for research, education, and training. New regulations within the PPACA have altered these relationships substantially. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act, Section 6002 of PPACA, was created to provide transparency in physicians\' interactions with medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological industries. As of August 1, 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid requires drug and device manufacturers to track (at a provider level) payments and other transfers of value exceeding $10 (single instance) or $100 (aggregate during 1 year) provided to physicians and teaching hospitals, with payments posted on a public Web site. This topic is beyond the scope of this article but is an important area that should be understood by all gastroenterologists.5

Clinical revenue

For many AMCs, clinical revenue has become the single largest source of funding for the School of Medicine. GI revenues are generated by professional billings from office and hospital-based consultations, management of established patients, and endoscopic procedures performed in a variety of practice settings (inpatient endoscopy units, hospital outpatient departments, and ambulatory endoscopy centers [AECs]). Technical revenues (monies paid to facilities as opposed to the professional fees paid to providers) associated with procedures (usually much larger than professional fees on a per service unit basis) almost always track to hospitals because many of the procedures are hospital-based or performed in hospital-funded (and owned) AECs.

Progressive GI divisions often have developed their own AECs and are able to model a financial partnership with their AMCs that combines professional and technical reimbursement in a collaborative manner. Gastroenterology benefits also from "niche" areas of health care delivery in AMCs, namely transplant hepatology, interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, oncology, and esophagology.

Some of the ability to augment GI programs has evolved from new models of revenue sharing between hospital systems and GI divisions that are based on income from AECs plus other "technical fees" such as revenue from biologic medication infusion. Technical fees (also called facility fees) are the monies paid to endoscopy labs, clinics, or hospitals in distinction to the "professional fee," which is reimbursement to providers for their medical services. Downstream revenue attributable to transplant hepatology has helped to redefine the close relationship between GI divisions and hospitals, where applicable. Practice ownership in AECs has helped transform GI health care economics not only in community-based gastroenterology but also in academic gastroenterology. Where AMCs adopt practice models that parallel community practice, such as the development of AECs, there is convergence of financial and clinical goals between AMCs and community gastroenterology. This comes during a time when community practices are increasingly concerned about long-term security as independent practices especially as health care reform progresses. This combination of factors has led some AMCs to develop closer alliances with community GI practices in their region.

There are several models of cooperation between academic GI faculty and community practices. The "loosest" affiliation occurs when the AMC creates a facilitated referral process targeted to key community practices in return for lending the AMC "brand" to the practice. Closer partnerships might include a shared inpatient service, professional service agreement, co-management of clinical service lines, or joint-venture arrangements to build and manage AECs.

A number of practices have realized advantages of full merger and have negotiated a pathway to becoming clinical faculty members. The AMC typically provides the shared electronic medical record (EMR) and assumes full responsibility for practice operations and office staff. With this arrangement, practices typically enjoy higher managed care rates, immediate buyout of hard assets (such as an AEC and infusion services), and the professional fulfillment attendant to becoming an academic clinician and educator.6

Emerging economic pressures

Training and education for GI fellows continue to be of paramount importance to GI divisions. There are more than 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited GI fellowships across the United States, but the number of fellows emerging from 3-year fellowship training has remained relatively constant during the last 10-15 years. Fellowship has been modified by the integration of advanced (fourth year) fellowships that align with the niche areas of gastroenterology: transplant hepatology (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited), interventional endoscopy, inflammatory bowel diseases, esophagology/motility, and potentially oncology. Typically, the mix of financial support for GI fellowship training, a not insignificant cost for academic gastroenterology, involves National Institutes of Health T32 training grants (for the research component of GI fellowship), Graduate Medical Education support, and clinical revenue (directly from the GI budget and indirectly from the hospital budget). Occasionally, unrestricted industry support may help, especially in the advanced GI fellowships.

Traditionally, AMCs have been able to command higher managed care rates compared with nonacademic hospital systems to account for time related to clinical care delivered by an attending physician as he or she teaches medical students, residents, and fellows in the art and science of medicine or technical skills related to endoscopic procedures or surgery. This situation is changing rapidly as cost pressures force both state and commercial payers to bring increasing scrutiny to total cost of care negotiations.

Currently, an overriding concern for purchasers of health care is cost. Purchasers of health care are increasingly carving out narrowed provider networks that are based largely on cost, a situation that may leave some AMCs excluded from large groups of patients.7

We are witnessing an extraordinary downward pressure on reimbursement for all medical services from every type of payer. There also is an emerging shift to value-based reimbursement where revenue for medical services is linked to patient outcomes. As this trend continues, AMCs may need to compete directly with integrated delivery networks (IDNs) that are emerging as an increasingly dominant care delivery model characterized by close clinical and financial linkage among primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary services1 in areas where this is relevant.

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of the total cost of care among three major types of IDNs. IDNs that are "closed," meaning all aspects of care are contained within a single financial umbrella (eg, Kaiser Permanente), control costs by owning and aggressively managing all aspects of care delivery (primary and specialty providers, hospitals, and ancillary facilities). They usually have an enterprise-wide EMR that simplifies transmission of information (1 patient, 1 chart). Few patients are referred outside the IDN, and the total cost of care for a purchaser of health benefits can be low in comparison with other regional delivery networks (Figure 1).

Another IDN model comprises partially owned (or employed) providers and hospitals but affiliations with independent specialty groups. The fact that all providers are not employed and often have different EMRs compared with the core hospital system adds additional costs. The third type of IDN includes AMCs that increase costs compared with other IDNs because of the fundamental missions of research and teaching. Despite the importance of their tripartite missions, some AMCs are being forced to compete for market share with well-managed closed network IDNs. Consequently, increased costs must be balanced by clearly defined added value that would be important to purchasers and individual patients alike.

Finally, as state and federal exchanges mature (2014 and beyond), the health care purchasing market will shift from a "wholesale" to a "retail" viewpoint where decisions about joining health systems will increasingly be at the level of individual patients. Exchanges organize price and quality information about regional provider networks in a manner that allows individuals to choose their providers with greater price and quality transparency. If AMCs in these mature markets are out of network or too costly, patient co-pays and deductibles will preclude large segments of patients from seeking their care at those centers.

In regions of the country where purchasers have organized to negotiate health care contracts, narrow provider networks and highly managed referral patterns have specifically excluded some well-known (but expensive) tertiary and quaternary referral centers. Examples of AMCs that have been excluded from significant provider networks can be found already in mature managed care markets such as California, Minnesota, and Massachusetts. Dr Martin Brotman articulated these concepts in unambiguous terms during his Presidential Plenary presentation at Digestive Disease Week® 2013. (An interview with Dr Brotman can be accessed on YouTube, available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hquW3NZtnxM).

Five steps that will help AMCs survive

Because of the changes we have defined, what are the key steps that AMC GI divisions can implement now to help build a sustainable practice model? There are five basic suggested steps that may be useful.

Focus on patient-centered care

As health care delivery moves to a patient-centered model, demands on faculty have changed. Clinical faculty members now are expected to be accessible to patients, complete medical records promptly, and follow lab and biopsy results in a timely manner. Federal and commercial payers both are developing robust Web sites that distinguish quality and cost at a provider level. This unprecedented focus on transparency of practice will affect all gastroenterologists equally, no matter what their practice setting.GI divisions must respond to these changes by building a robust clinical infrastructure to help support academic faculty, while allowing time for research and educational activities combined with an information technology platform that facilitates collection of performance and value metrics. Many AMCs structure care around specific patient conditions and have developed Centers of Excellence that provide cutting edge, coordinated care for populations of patients (inflammatory bowel disease, foregut disorders, hepatology, for example).

Enhance clinical efficiency

Economic pressure on AMCs is growing rapidly, so division funds will increasingly be tied directly to clinical productivity of faculty. GI divisions can develop or augment efficient clinical enterprises by focusing on easy and rapid patient access, development of clinical service lines that distinguish faculty from community physicians, efficient endoscopy practices, and other measurable activities that enhance and expand clinical service. Much of this redesign will require joint investment shared by GI divisions and their hospital systems.

Align incentives

AMCs typically have multiple distinct entities such as a school of medicine, a health care delivery network, individual hospitals, a medical faculty practice, departments (eg, medicine, surgery), and individual divisions (eg, GI, renal, endocrine). By aligning incentives, maximizing the strengths and efficiencies of each entity, and developing a coordinated financial plan, AMCs can compete in regional markets. If AMCs are to succeed in the increasingly competitive health care market, there must be coordination and alignment at financial, governance, and operational levels in addition to the AMC working toward true clinical integration.

Operate at the speed of business

The pace of change at AMCs may be challenging. As we move to value-based reimbursement and note the emergence of large IDNs, barriers to clinical integration and financial alignment must be reduced swiftly. Aggregation of business processes, practice management, information transfer, and data collection and analysis all must be accomplished quickly. AMCs will meet this challenge with the type of intellectual tour de force we have witnessed during the last generation as applied to translational medical research. AMCs will lead in fields such as personalized medicine (pharmacogenomics, microbiome, cancer genetics), and through their clinical integration efforts they will emerge as leaders in coordinated population management as well.

Break down barriers between academic medical centers and community practice

American medicine has bifurcated care between AMCs that provide tertiary and quaternary care and community gastroenterology that provides primary and secondary care, although AMCs now are engaging in primary and secondary care as well. In a world where financial and outcome accountability for populations now will be paramount, cooperation along the entire spectrum of medical care will be needed. Traditional barriers between AMCs and community practices are beginning to fall as true integration of care emerges as a strategy for a sustainable IDN.

Academic gastroenterology: Looking forward

Academic gastroenterology comprises a unique blend of science and medicine. Certainly, there are deeply rooted traditions, many of which foster individual creativity and curiosity and provide a platform for diverse pathways and diversity. However, challenges exist, and open and transparent planning is necessary to meet and surmount these challenges. Successful AMCs will rise to these challenges.

References

1. Allen J.I. The road ahead. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 692-6.

2. Dorn S.D. Gastroenterology in a new era of accountability: Part 3 – accountable care organizations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:750-3.

3. Sheen E., Dorn S.D., Brill J.V., et al. Healthcare reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

4. Taylor I.L., Clinchy R.M. The Affordable Care Act and academic medical centers. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10: 828-30.

5. American Gastroenterological Association. Update on the physician payment Sunshine Act Final Rule. Available at: http://www.gastro.org/journals-publications/news/update-on-the-physician-payment-sunshine-act-final-rule. Accessed June 23, 2013.

6. Fink J.N., Libby D.E. Integration without employment. Healthcare Financial Management 2012;66: 54-62.

7. Daly R. Narrow negotiations. Modern Healthcare May 6, 2013;14.

Dr. Rustgi is professor Division of Gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Dr. Allen is clinical chief of gastroenterology and hepatology and professor at the Yale School of Medicine. The authors disclose no conflicts.