User login

Comparison of Shave and Punch Biopsy Utilization Among Dermatology Practices

In 2019, the 2 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for skin biopsies (11100 and 11101) were replaced with 6 new CPT codes that specify biopsy technique and associated procedural complexity. 1,2 Prior to the coding changes, all biopsies were reimbursed at the same payment level, but a punch biopsy (11104; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $133.29) is now reimbursed more than a shave biopsy (11102; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $106.42). 3 We sought to evaluate whether the decrease in reimbursement for shave biopsies and concurrent increase in reimbursement for punch biopsies led to a shift from shave to punch biopsy utilization.

Methods

We examined shave and punch biopsies submitted for pathologic examination at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Massachusetts General Physician’s Organization (all in Boston, Massachusetts), and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), in May 2018 vs May 2019 (four months after new codes were implemented). This study was approved by Partners HealthCare (Boston, Massachusetts) and the University of Pennsylvania institutional review boards.

We included shave and punch biopsies of skin performed by physician dermatologists and mid-level providers (ie, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) at dermatology practices. All biopsies performed by a technique other than shave or punch, unspecified biopsy type, consultation cases, nonskin biopsies (eg, mucosa), and biopsies performed at nondermatology practices were excluded. We also excluded biopsies by providers who were not present during both study periods to account for provider mix.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate for changes in the ratio of shave to punch biopsy utilization over time, we performed χ2 tests. Because care practices may differ between private and academic settings as well as between physicians and mid-level providers, we performed subgroup analyses by practice setting and provider type.4

Results

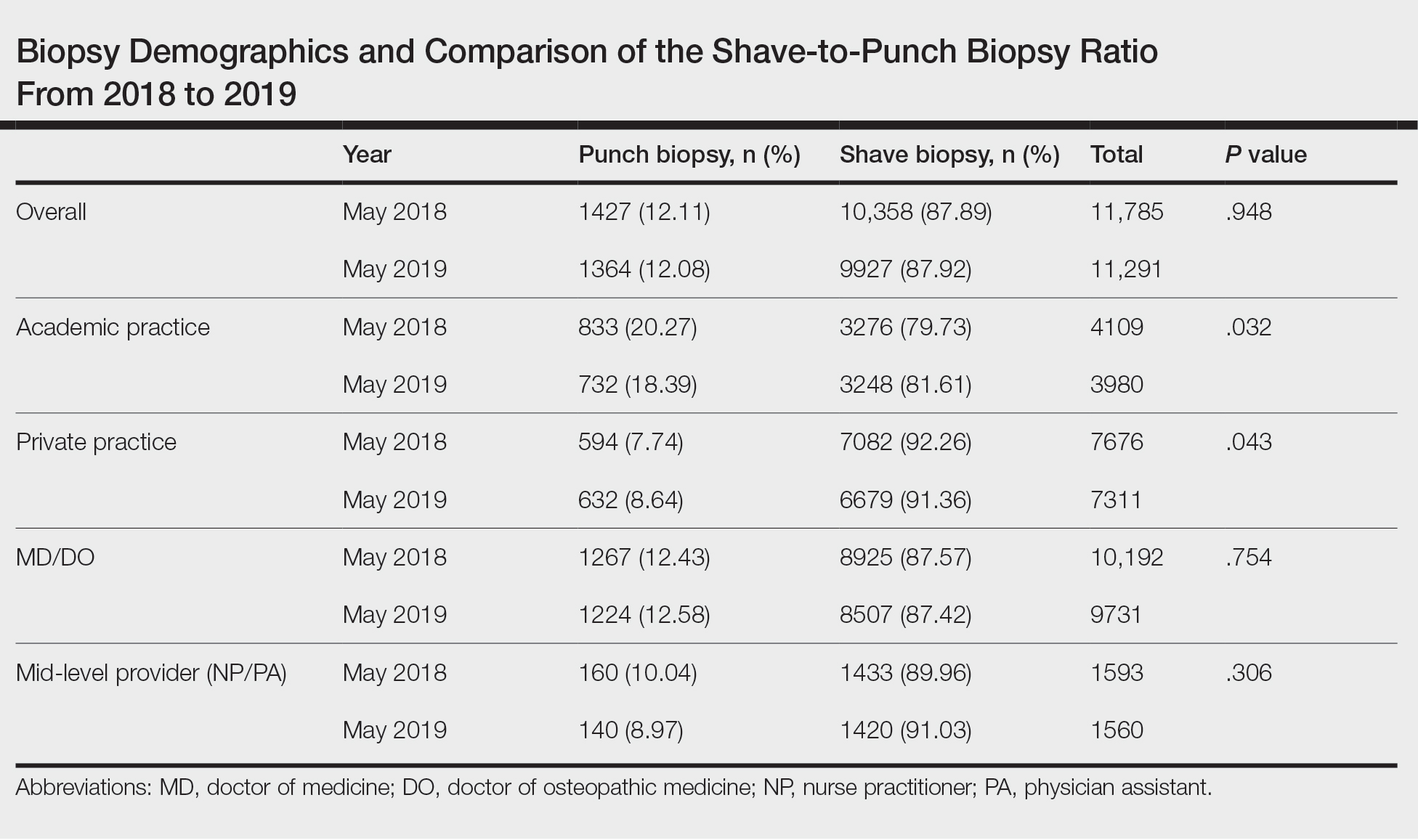

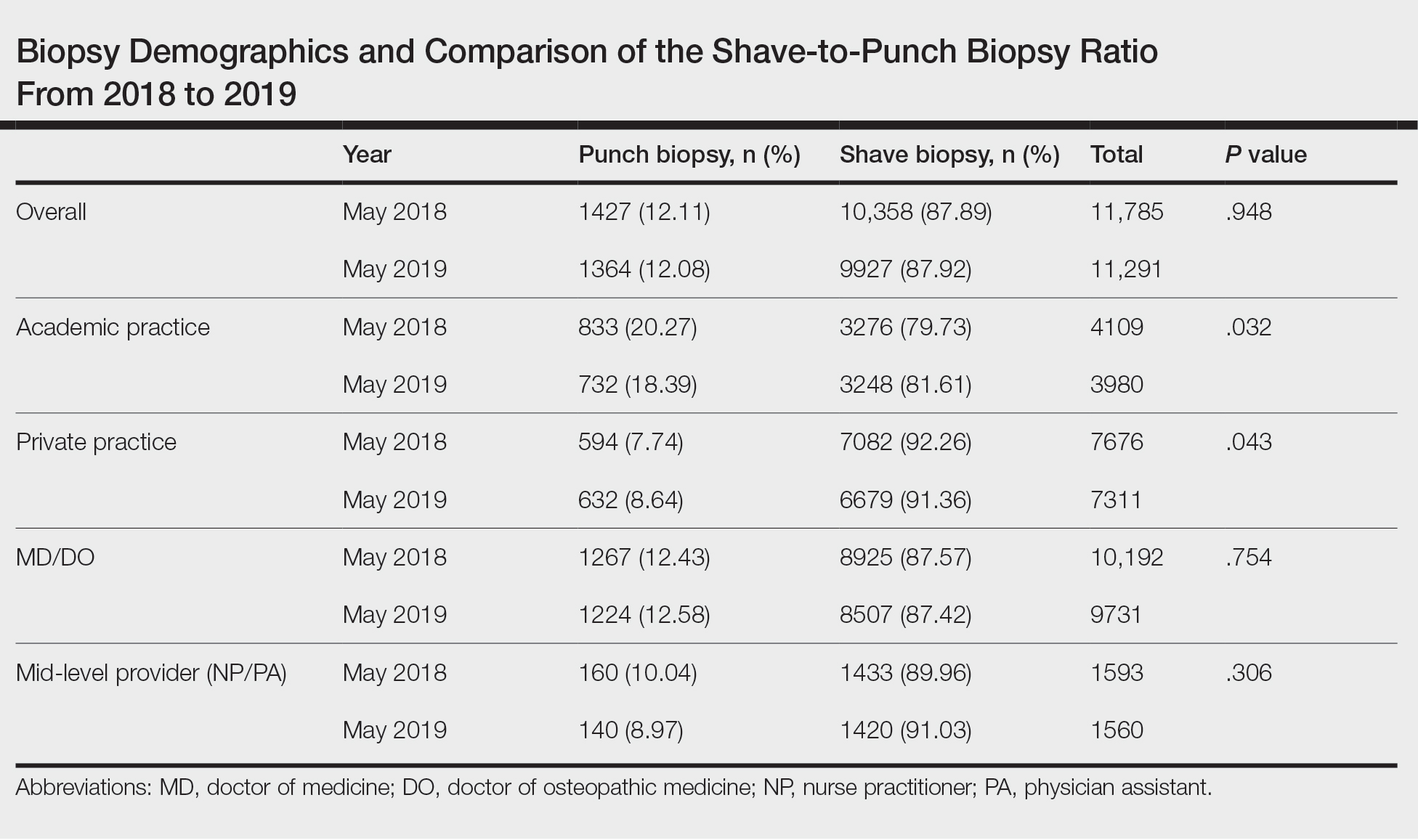

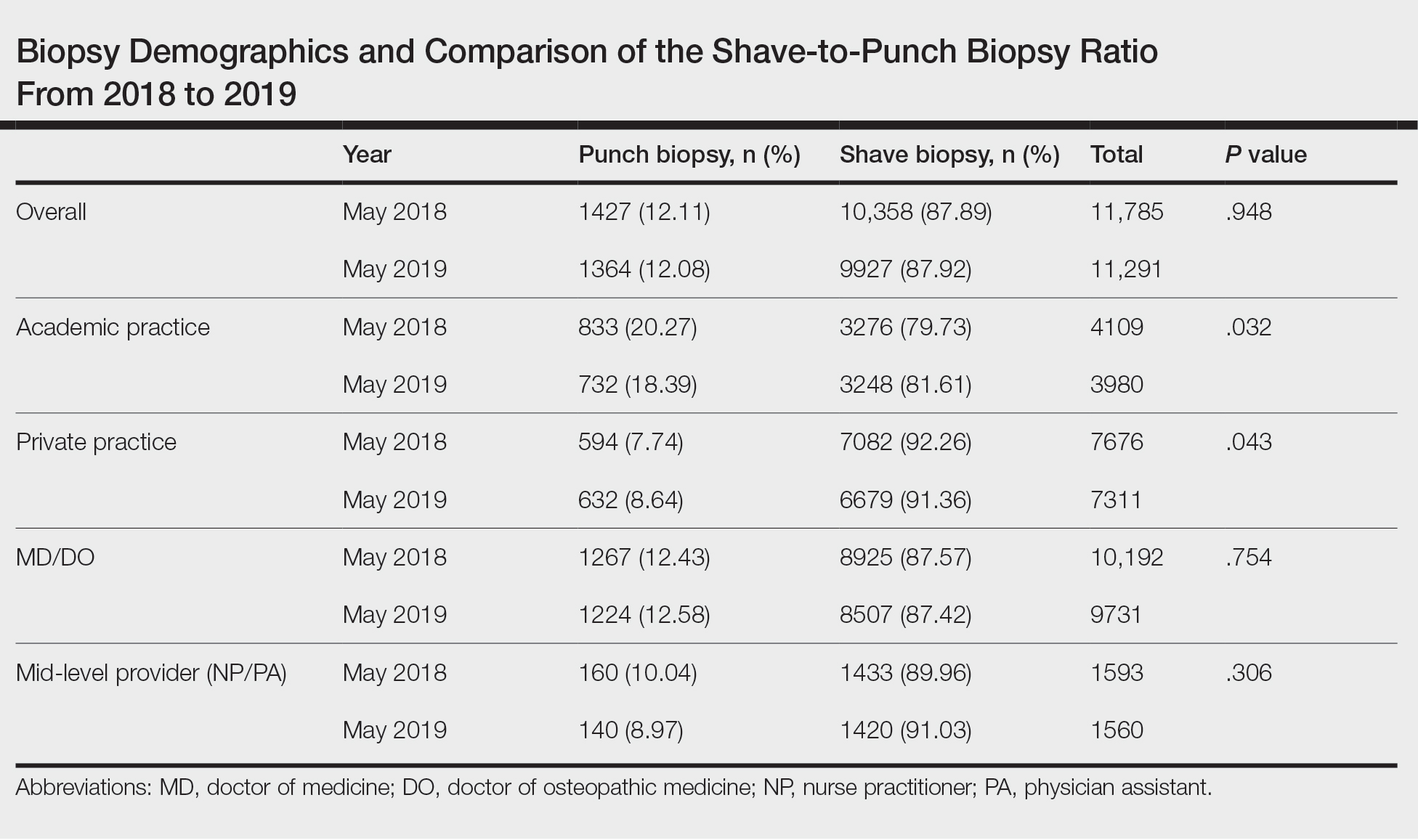

We identified 11,785 biopsies (12.11% of which were punch) submitted for pathologic examination in May 2018 compared to 11,291 biopsies (12.08% of which were punch) in May 2019 (Table). The overall use of punch biopsies relative to shave biopsies did not change between the years. There was a relative decrease in punch biopsy use among academic practices (−1.88%; P=.032) and a relative increase in punch biopsy use among private practices (+0.90%; P=.043). Provider type was not associated with differing utilization of biopsy type.

Comment

Overall, there was not a considerable shift in utilization behavior from shave to punch biopsies after the introduction of new coding changes. However, our study does demonstrate a small yet significant increase in punch biopsy utilization among private practices, and a decrease among academic practices. Although the change in biopsy utilization behavior is small in magnitude, it may have a substantial impact when extrapolated to behavior across the entire United States.

We were unable to assess additional factors, such as clinical diagnosis, body site, and cosmetic concerns, that may impact biopsy type selection in this study. Although we included multiple study sites to improve generalizability, our findings may not be representative of all biopsies performed in the dermatology setting. The baseline difference in relative punch biopsy use in academic vs private practices may reflect differences in patient populations and chief concerns, but assuming these features are stable over a 1-year time period, our findings should remain valid. Future studies should focus on qualitative evaluations of physician decision-making and evaluate whether similar trends persist over time.

Conclusion

Skin biopsy utilization trends among differing practice and provider types should continue to be monitored to assess for longitudinal trends in utilization within the context of updated billing codes and associated reimbursements.

- Grider D. 2019 CPT® coding for skin biopsies. ICD10 monitor website. September 17, 2018. Updated January 7, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.icd10monitor.com/2019-cpt-coding-for-skin-biopsies 2.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Search the physician fee schedule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

In 2019, the 2 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for skin biopsies (11100 and 11101) were replaced with 6 new CPT codes that specify biopsy technique and associated procedural complexity. 1,2 Prior to the coding changes, all biopsies were reimbursed at the same payment level, but a punch biopsy (11104; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $133.29) is now reimbursed more than a shave biopsy (11102; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $106.42). 3 We sought to evaluate whether the decrease in reimbursement for shave biopsies and concurrent increase in reimbursement for punch biopsies led to a shift from shave to punch biopsy utilization.

Methods

We examined shave and punch biopsies submitted for pathologic examination at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Massachusetts General Physician’s Organization (all in Boston, Massachusetts), and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), in May 2018 vs May 2019 (four months after new codes were implemented). This study was approved by Partners HealthCare (Boston, Massachusetts) and the University of Pennsylvania institutional review boards.

We included shave and punch biopsies of skin performed by physician dermatologists and mid-level providers (ie, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) at dermatology practices. All biopsies performed by a technique other than shave or punch, unspecified biopsy type, consultation cases, nonskin biopsies (eg, mucosa), and biopsies performed at nondermatology practices were excluded. We also excluded biopsies by providers who were not present during both study periods to account for provider mix.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate for changes in the ratio of shave to punch biopsy utilization over time, we performed χ2 tests. Because care practices may differ between private and academic settings as well as between physicians and mid-level providers, we performed subgroup analyses by practice setting and provider type.4

Results

We identified 11,785 biopsies (12.11% of which were punch) submitted for pathologic examination in May 2018 compared to 11,291 biopsies (12.08% of which were punch) in May 2019 (Table). The overall use of punch biopsies relative to shave biopsies did not change between the years. There was a relative decrease in punch biopsy use among academic practices (−1.88%; P=.032) and a relative increase in punch biopsy use among private practices (+0.90%; P=.043). Provider type was not associated with differing utilization of biopsy type.

Comment

Overall, there was not a considerable shift in utilization behavior from shave to punch biopsies after the introduction of new coding changes. However, our study does demonstrate a small yet significant increase in punch biopsy utilization among private practices, and a decrease among academic practices. Although the change in biopsy utilization behavior is small in magnitude, it may have a substantial impact when extrapolated to behavior across the entire United States.

We were unable to assess additional factors, such as clinical diagnosis, body site, and cosmetic concerns, that may impact biopsy type selection in this study. Although we included multiple study sites to improve generalizability, our findings may not be representative of all biopsies performed in the dermatology setting. The baseline difference in relative punch biopsy use in academic vs private practices may reflect differences in patient populations and chief concerns, but assuming these features are stable over a 1-year time period, our findings should remain valid. Future studies should focus on qualitative evaluations of physician decision-making and evaluate whether similar trends persist over time.

Conclusion

Skin biopsy utilization trends among differing practice and provider types should continue to be monitored to assess for longitudinal trends in utilization within the context of updated billing codes and associated reimbursements.

In 2019, the 2 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for skin biopsies (11100 and 11101) were replaced with 6 new CPT codes that specify biopsy technique and associated procedural complexity. 1,2 Prior to the coding changes, all biopsies were reimbursed at the same payment level, but a punch biopsy (11104; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $133.29) is now reimbursed more than a shave biopsy (11102; national nonfacility Medicare payment, $106.42). 3 We sought to evaluate whether the decrease in reimbursement for shave biopsies and concurrent increase in reimbursement for punch biopsies led to a shift from shave to punch biopsy utilization.

Methods

We examined shave and punch biopsies submitted for pathologic examination at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Massachusetts General Physician’s Organization (all in Boston, Massachusetts), and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), in May 2018 vs May 2019 (four months after new codes were implemented). This study was approved by Partners HealthCare (Boston, Massachusetts) and the University of Pennsylvania institutional review boards.

We included shave and punch biopsies of skin performed by physician dermatologists and mid-level providers (ie, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) at dermatology practices. All biopsies performed by a technique other than shave or punch, unspecified biopsy type, consultation cases, nonskin biopsies (eg, mucosa), and biopsies performed at nondermatology practices were excluded. We also excluded biopsies by providers who were not present during both study periods to account for provider mix.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate for changes in the ratio of shave to punch biopsy utilization over time, we performed χ2 tests. Because care practices may differ between private and academic settings as well as between physicians and mid-level providers, we performed subgroup analyses by practice setting and provider type.4

Results

We identified 11,785 biopsies (12.11% of which were punch) submitted for pathologic examination in May 2018 compared to 11,291 biopsies (12.08% of which were punch) in May 2019 (Table). The overall use of punch biopsies relative to shave biopsies did not change between the years. There was a relative decrease in punch biopsy use among academic practices (−1.88%; P=.032) and a relative increase in punch biopsy use among private practices (+0.90%; P=.043). Provider type was not associated with differing utilization of biopsy type.

Comment

Overall, there was not a considerable shift in utilization behavior from shave to punch biopsies after the introduction of new coding changes. However, our study does demonstrate a small yet significant increase in punch biopsy utilization among private practices, and a decrease among academic practices. Although the change in biopsy utilization behavior is small in magnitude, it may have a substantial impact when extrapolated to behavior across the entire United States.

We were unable to assess additional factors, such as clinical diagnosis, body site, and cosmetic concerns, that may impact biopsy type selection in this study. Although we included multiple study sites to improve generalizability, our findings may not be representative of all biopsies performed in the dermatology setting. The baseline difference in relative punch biopsy use in academic vs private practices may reflect differences in patient populations and chief concerns, but assuming these features are stable over a 1-year time period, our findings should remain valid. Future studies should focus on qualitative evaluations of physician decision-making and evaluate whether similar trends persist over time.

Conclusion

Skin biopsy utilization trends among differing practice and provider types should continue to be monitored to assess for longitudinal trends in utilization within the context of updated billing codes and associated reimbursements.

- Grider D. 2019 CPT® coding for skin biopsies. ICD10 monitor website. September 17, 2018. Updated January 7, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.icd10monitor.com/2019-cpt-coding-for-skin-biopsies 2.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Search the physician fee schedule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Grider D. 2019 CPT® coding for skin biopsies. ICD10 monitor website. September 17, 2018. Updated January 7, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.icd10monitor.com/2019-cpt-coding-for-skin-biopsies 2.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Search the physician fee schedule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that skin biopsy billing codes and reimbursements were changed in 2019 to reflect their level of complexity, which may impact how often each type of biopsy is used.

- Even small shifts in biopsy utilization behavior among dermatologists in the context of reimbursement changes can have a large impact on net reimbursements.