User login

Multiple Fungating Plaques on the Face, Arms, and Legs

Multiple Fungating Plaques on the Face, Arms, and Legs

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox

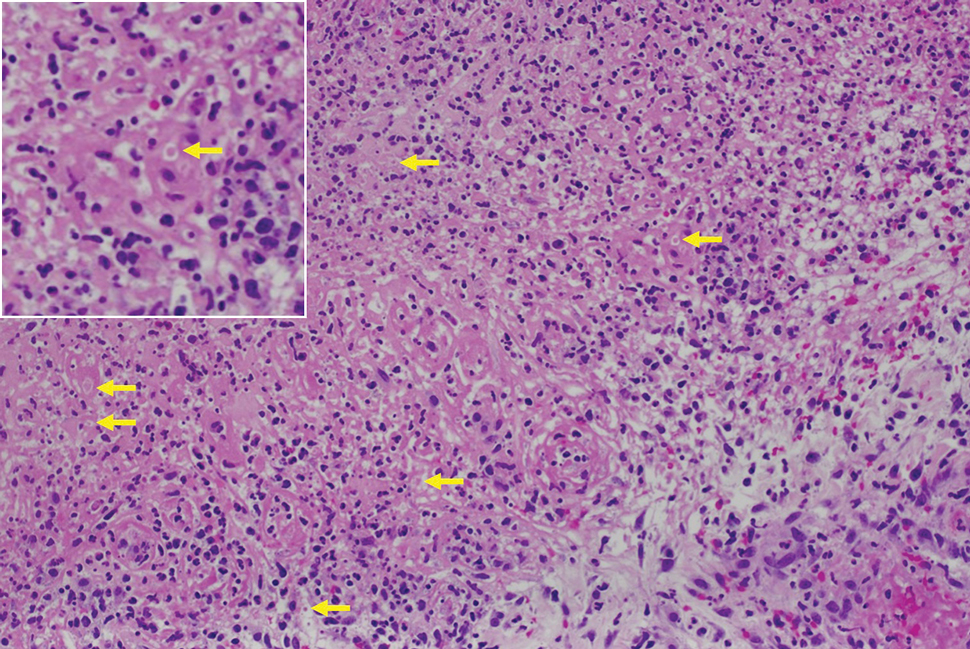

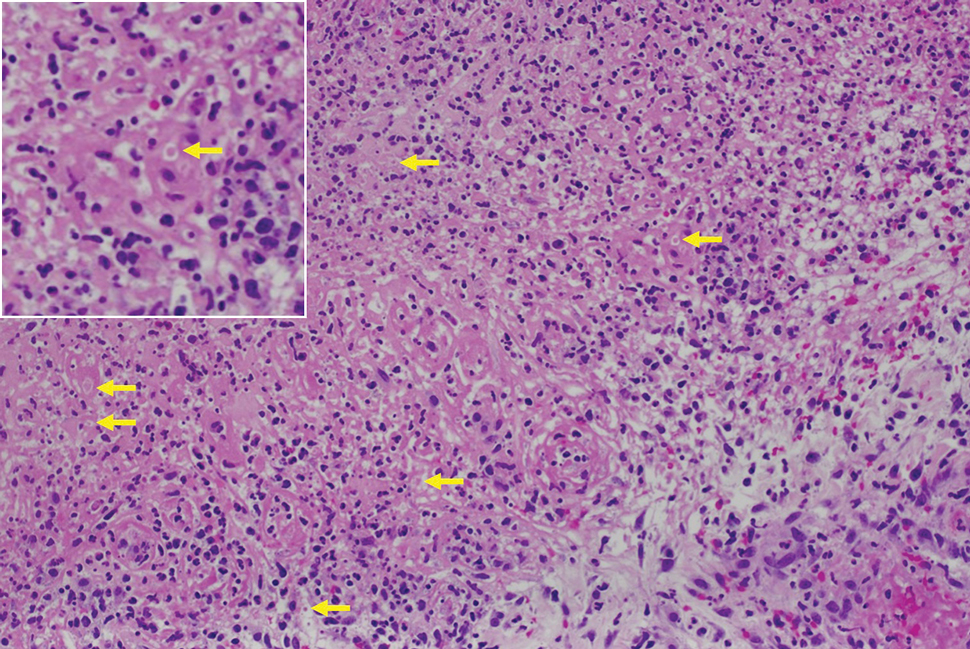

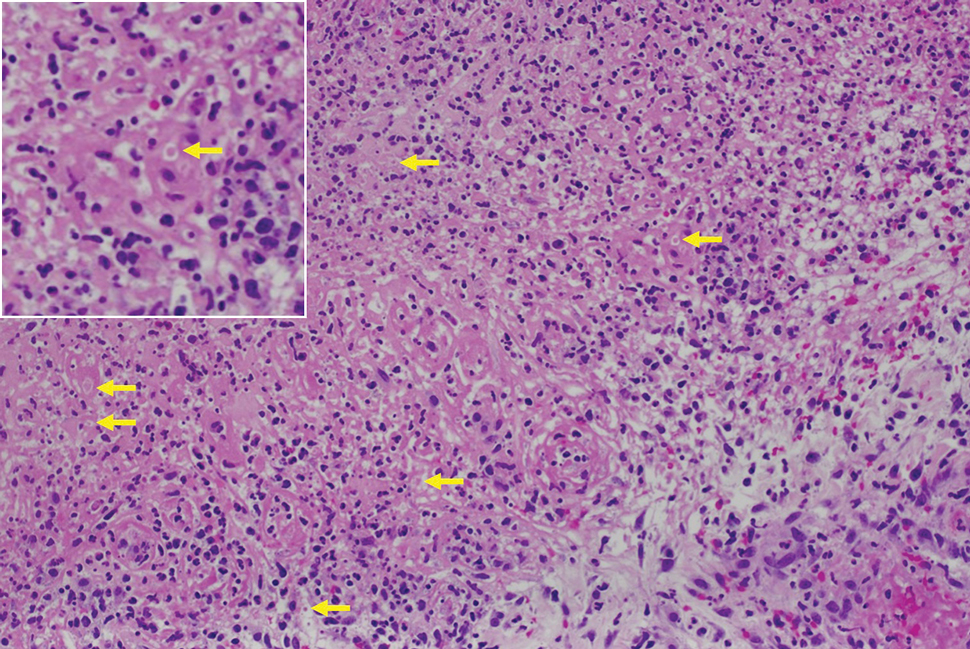

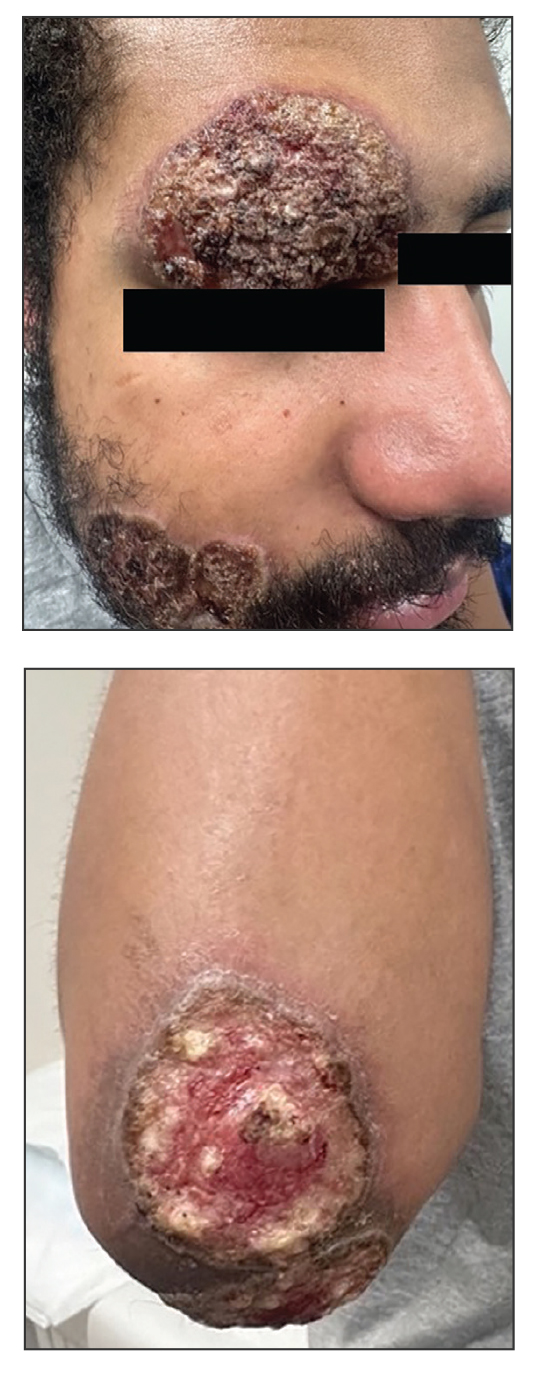

Histologic examination demonstrated dense aggregates of necrotic cellular debris composed of karyorrhectic nuclear fragments intermixed with neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions also were observed (Figure 1). The bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial histologic special stains and cultures were negative. Three weeks after the initial visit with dermatology, the patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening symptoms of fever, chills, and painful erythema surrounding the skin lesions. Serology and viral workup revealed a positive mpox polymerase chain reaction test, suggesting a diagnosis of mpox. Following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocol, the patient was started on oral tecovirimat 200 mg twice daily for 3 weeks and intravenous infusions of cidofovir 345 mg once weekly for 2 weeks. After treatment was initiated, the skin lesions showed rapid improvement (Figure 2), and he was discharged from the hospital after finishing the second dose of cidofovir. Four months after the initial dermatology consultation, the lesions had resolved completely with residual scarring. At that time, the patient had full movement of the right eye.

shows higher digital magnification of eosinophilic inclusions observed throughout the biopsy specimen (original magnification ×400).

Mpox virus is a member of the Poxviridae family of zoonotic viruses, which are transmitted from animals to humans. The mpox virus is brick-shaped (rectangular) and has a genome of linear double-stranded DNA encoding 180 proteins.1 Primates and rodents are the typical host reservoirs for viral circulation of mpox.2 Animal-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with mucous membranes, bodily fluids, or tissues of an infected animal. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with infected mucous membranes, bodily fluids, respiratory droplets, and contaminated fomites.2

Symptoms typically occur within 1 week of exposure to the mpox virus. Prodromal symptoms of fever, sore throat, body aches, and headaches last for 3 days.1 Many patients experience a facial rash that spreads to the arms and legs over a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The rash initially manifests as small papules that progress to painful pustules and vesicles measuring 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter.3 The mpox virus is transmitted through these skin lesions until they crust over and re-epithelialize.1 The case fatality rate for mpox infection remains low (0.18%).4

Mpox outbreaks mainly were limited to central and western Africa prior to 2022. From May 17, 2022, through October 6, 2022, 26,384 cases of mpox were reported in the United States.5 During this outbreak, immunocompromised patients diagnosed with HIV and men who have sex with men were disproportionately affected.5

Due to the similarities between the smallpox virus and other orthopoxviruses, certain smallpox vaccines have been indicated for pre-exposure prophylaxis.6 The efficacy of prophylactic vaccination is believed to stem from the production of neutralizing antibodies that are cross-protective against other orthopoxviruses, including mpox.7 The 2 vaccines approved in the United States for mpox prophylaxis are JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, which are both live attenuated vaccines. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for patients at risk for severe disease, including men who have sex with men, individuals diagnosed with HIV or other immunosuppressive disorders, and individuals with recent diagnoses of one or more sexually transmitted diseases.8

Most mpox cases resolve within 2 to 4 weeks and only require supportive care (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical steroids, topical anesthetics) to treat pain.8 For patients at risk for severe disease, antiviral medications are warranted. Tecovirimat, brincidofovir, and cidofovir are antiviral medications used to treat smallpox that are thought to be effective against mpox.8,9 Tecovirimat and cidofovir have been shown to be effective against mpox in animal trials, but randomized or nonrandomized trials have not been performed in humans.9-11 Tecovirimat currently is available for the treatment of severe mpox in patients who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Investigational New Drug protocol; for these patients, a 200-mg course is administered orally or intravenously every 12 hours for 2 weeks.8

- Lu J, Xing H, Wang C, et al. Mpox (formerly monkeypox): pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:458. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01675-

- Lim CK, Roberts J, Moso M, et al. Mpox diagnostics: review of current and emerging technologies. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28429. doi:10.1002/jmv.28429

- Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1:8. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed1010008

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox) World Health Organization. Published April 18, 2023. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Kava CM, Rohraff DM, Wallace B, et al. Epidemiologic features of the monkeypox outbreak and the public health response—United States, May 17–October 6, 2022. 2022:1449-1456. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7145a4.htm?s_cid=mm7145a4_w

- Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, et al. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957-963. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01742-y

- Edghill-Smith Y, Golding H, Manischewitz J, et al. Smallpox vaccine-induced antibodies are necessary and sufficient for protection against monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2005;11:740-747. doi:10.1038 /nm1261

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 18, 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/treatment.html

- Mitja O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, et al. Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023;401:60-74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X

- Huggins J, Goff A, Hensley L, et al. Nonhuman primates are protected from smallpox virus or monkeypox virus challenges by the antiviral drug ST-246. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2620-2625. doi:10.1128/aac.00021-09

- Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:44-53. doi:10.1056 /nejmoa1705688

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox

Histologic examination demonstrated dense aggregates of necrotic cellular debris composed of karyorrhectic nuclear fragments intermixed with neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions also were observed (Figure 1). The bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial histologic special stains and cultures were negative. Three weeks after the initial visit with dermatology, the patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening symptoms of fever, chills, and painful erythema surrounding the skin lesions. Serology and viral workup revealed a positive mpox polymerase chain reaction test, suggesting a diagnosis of mpox. Following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocol, the patient was started on oral tecovirimat 200 mg twice daily for 3 weeks and intravenous infusions of cidofovir 345 mg once weekly for 2 weeks. After treatment was initiated, the skin lesions showed rapid improvement (Figure 2), and he was discharged from the hospital after finishing the second dose of cidofovir. Four months after the initial dermatology consultation, the lesions had resolved completely with residual scarring. At that time, the patient had full movement of the right eye.

shows higher digital magnification of eosinophilic inclusions observed throughout the biopsy specimen (original magnification ×400).

Mpox virus is a member of the Poxviridae family of zoonotic viruses, which are transmitted from animals to humans. The mpox virus is brick-shaped (rectangular) and has a genome of linear double-stranded DNA encoding 180 proteins.1 Primates and rodents are the typical host reservoirs for viral circulation of mpox.2 Animal-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with mucous membranes, bodily fluids, or tissues of an infected animal. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with infected mucous membranes, bodily fluids, respiratory droplets, and contaminated fomites.2

Symptoms typically occur within 1 week of exposure to the mpox virus. Prodromal symptoms of fever, sore throat, body aches, and headaches last for 3 days.1 Many patients experience a facial rash that spreads to the arms and legs over a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The rash initially manifests as small papules that progress to painful pustules and vesicles measuring 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter.3 The mpox virus is transmitted through these skin lesions until they crust over and re-epithelialize.1 The case fatality rate for mpox infection remains low (0.18%).4

Mpox outbreaks mainly were limited to central and western Africa prior to 2022. From May 17, 2022, through October 6, 2022, 26,384 cases of mpox were reported in the United States.5 During this outbreak, immunocompromised patients diagnosed with HIV and men who have sex with men were disproportionately affected.5

Due to the similarities between the smallpox virus and other orthopoxviruses, certain smallpox vaccines have been indicated for pre-exposure prophylaxis.6 The efficacy of prophylactic vaccination is believed to stem from the production of neutralizing antibodies that are cross-protective against other orthopoxviruses, including mpox.7 The 2 vaccines approved in the United States for mpox prophylaxis are JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, which are both live attenuated vaccines. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for patients at risk for severe disease, including men who have sex with men, individuals diagnosed with HIV or other immunosuppressive disorders, and individuals with recent diagnoses of one or more sexually transmitted diseases.8

Most mpox cases resolve within 2 to 4 weeks and only require supportive care (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical steroids, topical anesthetics) to treat pain.8 For patients at risk for severe disease, antiviral medications are warranted. Tecovirimat, brincidofovir, and cidofovir are antiviral medications used to treat smallpox that are thought to be effective against mpox.8,9 Tecovirimat and cidofovir have been shown to be effective against mpox in animal trials, but randomized or nonrandomized trials have not been performed in humans.9-11 Tecovirimat currently is available for the treatment of severe mpox in patients who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Investigational New Drug protocol; for these patients, a 200-mg course is administered orally or intravenously every 12 hours for 2 weeks.8

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox

Histologic examination demonstrated dense aggregates of necrotic cellular debris composed of karyorrhectic nuclear fragments intermixed with neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions also were observed (Figure 1). The bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial histologic special stains and cultures were negative. Three weeks after the initial visit with dermatology, the patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening symptoms of fever, chills, and painful erythema surrounding the skin lesions. Serology and viral workup revealed a positive mpox polymerase chain reaction test, suggesting a diagnosis of mpox. Following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocol, the patient was started on oral tecovirimat 200 mg twice daily for 3 weeks and intravenous infusions of cidofovir 345 mg once weekly for 2 weeks. After treatment was initiated, the skin lesions showed rapid improvement (Figure 2), and he was discharged from the hospital after finishing the second dose of cidofovir. Four months after the initial dermatology consultation, the lesions had resolved completely with residual scarring. At that time, the patient had full movement of the right eye.

shows higher digital magnification of eosinophilic inclusions observed throughout the biopsy specimen (original magnification ×400).

Mpox virus is a member of the Poxviridae family of zoonotic viruses, which are transmitted from animals to humans. The mpox virus is brick-shaped (rectangular) and has a genome of linear double-stranded DNA encoding 180 proteins.1 Primates and rodents are the typical host reservoirs for viral circulation of mpox.2 Animal-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with mucous membranes, bodily fluids, or tissues of an infected animal. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with infected mucous membranes, bodily fluids, respiratory droplets, and contaminated fomites.2

Symptoms typically occur within 1 week of exposure to the mpox virus. Prodromal symptoms of fever, sore throat, body aches, and headaches last for 3 days.1 Many patients experience a facial rash that spreads to the arms and legs over a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The rash initially manifests as small papules that progress to painful pustules and vesicles measuring 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter.3 The mpox virus is transmitted through these skin lesions until they crust over and re-epithelialize.1 The case fatality rate for mpox infection remains low (0.18%).4

Mpox outbreaks mainly were limited to central and western Africa prior to 2022. From May 17, 2022, through October 6, 2022, 26,384 cases of mpox were reported in the United States.5 During this outbreak, immunocompromised patients diagnosed with HIV and men who have sex with men were disproportionately affected.5

Due to the similarities between the smallpox virus and other orthopoxviruses, certain smallpox vaccines have been indicated for pre-exposure prophylaxis.6 The efficacy of prophylactic vaccination is believed to stem from the production of neutralizing antibodies that are cross-protective against other orthopoxviruses, including mpox.7 The 2 vaccines approved in the United States for mpox prophylaxis are JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, which are both live attenuated vaccines. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for patients at risk for severe disease, including men who have sex with men, individuals diagnosed with HIV or other immunosuppressive disorders, and individuals with recent diagnoses of one or more sexually transmitted diseases.8

Most mpox cases resolve within 2 to 4 weeks and only require supportive care (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical steroids, topical anesthetics) to treat pain.8 For patients at risk for severe disease, antiviral medications are warranted. Tecovirimat, brincidofovir, and cidofovir are antiviral medications used to treat smallpox that are thought to be effective against mpox.8,9 Tecovirimat and cidofovir have been shown to be effective against mpox in animal trials, but randomized or nonrandomized trials have not been performed in humans.9-11 Tecovirimat currently is available for the treatment of severe mpox in patients who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Investigational New Drug protocol; for these patients, a 200-mg course is administered orally or intravenously every 12 hours for 2 weeks.8

- Lu J, Xing H, Wang C, et al. Mpox (formerly monkeypox): pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:458. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01675-

- Lim CK, Roberts J, Moso M, et al. Mpox diagnostics: review of current and emerging technologies. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28429. doi:10.1002/jmv.28429

- Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1:8. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed1010008

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox) World Health Organization. Published April 18, 2023. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Kava CM, Rohraff DM, Wallace B, et al. Epidemiologic features of the monkeypox outbreak and the public health response—United States, May 17–October 6, 2022. 2022:1449-1456. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7145a4.htm?s_cid=mm7145a4_w

- Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, et al. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957-963. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01742-y

- Edghill-Smith Y, Golding H, Manischewitz J, et al. Smallpox vaccine-induced antibodies are necessary and sufficient for protection against monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2005;11:740-747. doi:10.1038 /nm1261

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 18, 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/treatment.html

- Mitja O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, et al. Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023;401:60-74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X

- Huggins J, Goff A, Hensley L, et al. Nonhuman primates are protected from smallpox virus or monkeypox virus challenges by the antiviral drug ST-246. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2620-2625. doi:10.1128/aac.00021-09

- Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:44-53. doi:10.1056 /nejmoa1705688

- Lu J, Xing H, Wang C, et al. Mpox (formerly monkeypox): pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:458. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01675-

- Lim CK, Roberts J, Moso M, et al. Mpox diagnostics: review of current and emerging technologies. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28429. doi:10.1002/jmv.28429

- Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1:8. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed1010008

- World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox) World Health Organization. Published April 18, 2023. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- Kava CM, Rohraff DM, Wallace B, et al. Epidemiologic features of the monkeypox outbreak and the public health response—United States, May 17–October 6, 2022. 2022:1449-1456. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7145a4.htm?s_cid=mm7145a4_w

- Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, et al. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957-963. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01742-y

- Edghill-Smith Y, Golding H, Manischewitz J, et al. Smallpox vaccine-induced antibodies are necessary and sufficient for protection against monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2005;11:740-747. doi:10.1038 /nm1261

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox treatment information for healthcare professionals. Updated June 18, 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/treatment.html

- Mitja O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, et al. Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023;401:60-74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X

- Huggins J, Goff A, Hensley L, et al. Nonhuman primates are protected from smallpox virus or monkeypox virus challenges by the antiviral drug ST-246. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2620-2625. doi:10.1128/aac.00021-09

- Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:44-53. doi:10.1056 /nejmoa1705688

Multiple Fungating Plaques on the Face, Arms, and Legs

Multiple Fungating Plaques on the Face, Arms, and Legs

A 27-year-old man presented to his primary care physician after he was struck in the head by a tree branch while working outside. The next day, ulcerating lesions emerged on the right supraorbital ridge, along with subjective fevers, chills, fatigue, and shortness of breath. The patient reported a history of unprotected sexual intercourse with a male partner who was HIV positive. His medical history included syphilis status posttreatment with a course of 5 penicillin injections, hepatitis C, and HIV diagnosed one month prior to presentation (CD4 count, 169 cells/mm3 [reference range, 500-1500 cells/mm3]). A punch biopsy performed by the primary care physician revealed suppurative granulomatous inflammation, and the patient was prescribed antibiotics with mild improvement. He then was referred to dermatology for further evaluation of the ulcerating lesions.

Three months after the initial trauma, the patient presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple large fungating plaques affecting multiple sites on the face (top), arms (bottom), and legs. Physical examination revealed large circinate verrucous plaques involving the right supraorbital ridge and eyelid. The patient was unable to fully open the right eye. Similar plaques also were observed on the right malar cheek, arms, and feet. Four 5-mm punch biopsies from lesions on the right elbow and left ankle were obtained with fungal and bacterial cultures.

A 63-year-old male presented for evaluation of worsening genital lesions and associated swelling

.1 Clinically, ENV presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, cobblestone-like patches, plaques, and nodules with associated nonpitting edema of the affected body area.1 Secondary bacterial infections are common and often worsen the clinical course. The etiology of ENV involves chronic lymphatic obstruction and venous insufficiency, with additional risk factors including obesity, chronic lymphedema, bacterial infection, surgery or trauma, neoplasia, radiation, congestive heart failure, or scleroderma.2,3 While most commonly presenting on the lower extremities, cases have been reported involving the abdomen, sacrum, ears, buttocks, and penoscrotal area.1,2

Regardless of location, the pathogenesis of ENV remains the same. Chronic lymphatic obstruction results in accumulation and lymphostasis of protein-rich dermal fluid, which subsequently precipitates fibroblast proliferation and activation, suppression of the local immune response and development of recurrent lymphangitis, chronic inflammation, and potential secondary bacterial infection.2,4

There is no standard of care for the treatment and management of ENV and recurrence is common. Interventions often involve those used for chronic lymphedema – including leg elevation, compression stockings or devices, skin hygiene, and lymphatic pumping.2,3 Medical management with topical and oral retinoids has been reported, as well as emphasis on weight loss and infection control.1,4 Surgical intervention is often reserved for refractory cases that fail to respond to more conservative management, or severe presentations resulting in extensive functional and aesthetic impairment. Less commonly reported treatment modalities include lymphaticovenular anastomosis and ablative carbon dioxide laser use, although this latter intervention demonstrated minimal improvement in this patient.5,6

Penoscrotal ENV is a rare form of ENV affecting the genital region of males, often resulting in significant disfigurement, functional impairment, and psychosocial distress. Penoscrotal elephantiasis can be idiopathic, due to filarial infections, scleroinflammatory stricture of the urethra, Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and lymphostasis secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions such as streptococcal infections, radiotherapy, surgery, chronic venous stasis, or Kaposi sarcoma.7

In addition, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has been documented multiple times in the literature in association with the development of ENV, detailing lymphatic scarring secondary to chronic inguinal HS as the main pathogenic factor.8,9

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for penoscrotal ENV, which not only improves functionality and cosmesis, but also aids in prevention of rare malignant sequelae, such as lymphangiosarcoma.10 Such interventions can involve lymphangioplasty to aid in lymphatic drainage or excision of the mass and subcutaneous tissue with full-thickness skin grafting for reconstruction.7 Collaboration between urology, plastic surgery, and dermatology is often essential to obtain adequate care with satisfactory outcomes and minimal recurrence for patients with this uncommon condition.

This case and photo were submitted by Marlee Hill, a medical student at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City; and Michael Franzetti, MD, and Jeffrey McBride, MD, department of dermatology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Donna Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hadian Y et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Dec 15;25(12):13030/qt6rn1s8ff.

2. Judge N and Kilic A. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2016 Nov 13;10(2):32-4.

3. Dean SM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64(6):1104-10.

4. Sisto K and Khachemoune A. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(3):141-6.

5. Motegi S et al. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):147-51.

6. Robinson CG et al. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(6):611-3.

7. Koualla S et al. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2023 Apr 10;S0294-1260(23)00035-3.

8. Lelonek E et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021 Feb 11;101(2):adv00389.

9. Good LM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 May;64(5):993-4.

10. Cerri A et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Oct-Nov;8(7):511-4.

.1 Clinically, ENV presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, cobblestone-like patches, plaques, and nodules with associated nonpitting edema of the affected body area.1 Secondary bacterial infections are common and often worsen the clinical course. The etiology of ENV involves chronic lymphatic obstruction and venous insufficiency, with additional risk factors including obesity, chronic lymphedema, bacterial infection, surgery or trauma, neoplasia, radiation, congestive heart failure, or scleroderma.2,3 While most commonly presenting on the lower extremities, cases have been reported involving the abdomen, sacrum, ears, buttocks, and penoscrotal area.1,2

Regardless of location, the pathogenesis of ENV remains the same. Chronic lymphatic obstruction results in accumulation and lymphostasis of protein-rich dermal fluid, which subsequently precipitates fibroblast proliferation and activation, suppression of the local immune response and development of recurrent lymphangitis, chronic inflammation, and potential secondary bacterial infection.2,4

There is no standard of care for the treatment and management of ENV and recurrence is common. Interventions often involve those used for chronic lymphedema – including leg elevation, compression stockings or devices, skin hygiene, and lymphatic pumping.2,3 Medical management with topical and oral retinoids has been reported, as well as emphasis on weight loss and infection control.1,4 Surgical intervention is often reserved for refractory cases that fail to respond to more conservative management, or severe presentations resulting in extensive functional and aesthetic impairment. Less commonly reported treatment modalities include lymphaticovenular anastomosis and ablative carbon dioxide laser use, although this latter intervention demonstrated minimal improvement in this patient.5,6

Penoscrotal ENV is a rare form of ENV affecting the genital region of males, often resulting in significant disfigurement, functional impairment, and psychosocial distress. Penoscrotal elephantiasis can be idiopathic, due to filarial infections, scleroinflammatory stricture of the urethra, Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and lymphostasis secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions such as streptococcal infections, radiotherapy, surgery, chronic venous stasis, or Kaposi sarcoma.7

In addition, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has been documented multiple times in the literature in association with the development of ENV, detailing lymphatic scarring secondary to chronic inguinal HS as the main pathogenic factor.8,9

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for penoscrotal ENV, which not only improves functionality and cosmesis, but also aids in prevention of rare malignant sequelae, such as lymphangiosarcoma.10 Such interventions can involve lymphangioplasty to aid in lymphatic drainage or excision of the mass and subcutaneous tissue with full-thickness skin grafting for reconstruction.7 Collaboration between urology, plastic surgery, and dermatology is often essential to obtain adequate care with satisfactory outcomes and minimal recurrence for patients with this uncommon condition.

This case and photo were submitted by Marlee Hill, a medical student at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City; and Michael Franzetti, MD, and Jeffrey McBride, MD, department of dermatology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Donna Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hadian Y et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Dec 15;25(12):13030/qt6rn1s8ff.

2. Judge N and Kilic A. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2016 Nov 13;10(2):32-4.

3. Dean SM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64(6):1104-10.

4. Sisto K and Khachemoune A. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(3):141-6.

5. Motegi S et al. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):147-51.

6. Robinson CG et al. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(6):611-3.

7. Koualla S et al. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2023 Apr 10;S0294-1260(23)00035-3.

8. Lelonek E et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021 Feb 11;101(2):adv00389.

9. Good LM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 May;64(5):993-4.

10. Cerri A et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Oct-Nov;8(7):511-4.

.1 Clinically, ENV presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, cobblestone-like patches, plaques, and nodules with associated nonpitting edema of the affected body area.1 Secondary bacterial infections are common and often worsen the clinical course. The etiology of ENV involves chronic lymphatic obstruction and venous insufficiency, with additional risk factors including obesity, chronic lymphedema, bacterial infection, surgery or trauma, neoplasia, radiation, congestive heart failure, or scleroderma.2,3 While most commonly presenting on the lower extremities, cases have been reported involving the abdomen, sacrum, ears, buttocks, and penoscrotal area.1,2

Regardless of location, the pathogenesis of ENV remains the same. Chronic lymphatic obstruction results in accumulation and lymphostasis of protein-rich dermal fluid, which subsequently precipitates fibroblast proliferation and activation, suppression of the local immune response and development of recurrent lymphangitis, chronic inflammation, and potential secondary bacterial infection.2,4

There is no standard of care for the treatment and management of ENV and recurrence is common. Interventions often involve those used for chronic lymphedema – including leg elevation, compression stockings or devices, skin hygiene, and lymphatic pumping.2,3 Medical management with topical and oral retinoids has been reported, as well as emphasis on weight loss and infection control.1,4 Surgical intervention is often reserved for refractory cases that fail to respond to more conservative management, or severe presentations resulting in extensive functional and aesthetic impairment. Less commonly reported treatment modalities include lymphaticovenular anastomosis and ablative carbon dioxide laser use, although this latter intervention demonstrated minimal improvement in this patient.5,6

Penoscrotal ENV is a rare form of ENV affecting the genital region of males, often resulting in significant disfigurement, functional impairment, and psychosocial distress. Penoscrotal elephantiasis can be idiopathic, due to filarial infections, scleroinflammatory stricture of the urethra, Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and lymphostasis secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions such as streptococcal infections, radiotherapy, surgery, chronic venous stasis, or Kaposi sarcoma.7

In addition, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has been documented multiple times in the literature in association with the development of ENV, detailing lymphatic scarring secondary to chronic inguinal HS as the main pathogenic factor.8,9

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for penoscrotal ENV, which not only improves functionality and cosmesis, but also aids in prevention of rare malignant sequelae, such as lymphangiosarcoma.10 Such interventions can involve lymphangioplasty to aid in lymphatic drainage or excision of the mass and subcutaneous tissue with full-thickness skin grafting for reconstruction.7 Collaboration between urology, plastic surgery, and dermatology is often essential to obtain adequate care with satisfactory outcomes and minimal recurrence for patients with this uncommon condition.

This case and photo were submitted by Marlee Hill, a medical student at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City; and Michael Franzetti, MD, and Jeffrey McBride, MD, department of dermatology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Donna Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hadian Y et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Dec 15;25(12):13030/qt6rn1s8ff.

2. Judge N and Kilic A. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2016 Nov 13;10(2):32-4.

3. Dean SM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64(6):1104-10.

4. Sisto K and Khachemoune A. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(3):141-6.

5. Motegi S et al. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):147-51.

6. Robinson CG et al. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(6):611-3.

7. Koualla S et al. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2023 Apr 10;S0294-1260(23)00035-3.

8. Lelonek E et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021 Feb 11;101(2):adv00389.

9. Good LM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 May;64(5):993-4.

10. Cerri A et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Oct-Nov;8(7):511-4.