User login

A nodule on a woman’s face

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymphocytoma cutis

- Amelanotic melanoma

- Pyogenic granuloma

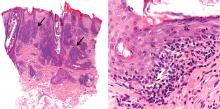

A: The correct answer is lymphocytoma cutis. The differential diagnosis of a pink papule on the face of a middle-aged person includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, lymphocytoma cutis, metastatic disease, certain infections, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, connective tissue disease, and some adnexal tumors. Histologic study is a useful diagnostic aid in this context.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cutaneous malignant neoplasm, and although these tumors rarely metastasize, they are capable of gross tissue destruction, particularly those lesions arising on the face. Clinically, this tumor presents as a shiny, pearly nodule with telangiectasias on the surface, as in our patient, but skin biopsy shows large basaloid lobules of varying shape and size forming a relatively circumscribed mass with a “palisade” around the rim of the lobule.

Squamous cell carcinoma manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and elevated, indurate borders, but also as plaques or nodules. The clinical diagnosis should be confirmed with skin biopsy, which reveals atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and horn pearl formation, depending on the differentiation of the tumor.

Amelanotic melanoma is nonpigmented and appears as a pink nodule mimicking basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic study is necessary for the diagnosis, and shows an atypical proliferation of melanocytic cells in the epidermis and dermis.

Pyogenic granuloma is a very common benign vascular lesion considered to be a hyperplastic process or a vascular neoplasm. The lesion typically presents as a red or bluish papule or polyp that bleeds easily, and a reddish homogeneous area surrounded by a white “collarette” is found in most cases. Histologic features of an early lesion resemble granulation tissue and include lobules of capillaries and venules that often radiate from larger, more central vessels.

LYMPHOCYTOMA CUTIS: KEY FEATURES

Lymphocytoma cutis (pseudolymphoma) is a benign reactive polyclonal and inflammatory disorder that most frequently includes B lymphocytes, with a smaller population of T lymphocytes. It infiltrates the skin and resembles rudimentary germinal follicles, as in the present case. The lesion usually presents as an asymptomatic red-brown or violet papule or nodule, 3 mm to 5 cm in diameter, most often on the face, chest, or upper extremities.1 The lesion may be solitary, as in our patient, but lesions may also be grouped or numerous and widespread. It is three times more common in women than in men. It may resolve spontaneously, but it may also recur.

In Europe, lymphocytoma cutis occurs most often in B burgdorferi infection after a tick bite. Lymphocytoma cutis occurs in 1.3% of cases of B burgdorferi infection,2 although other infectious, physical, or chemical agents may produce the same reaction pattern. Tattooing (particularly red areas), acupuncture, vaccination, arthropod reactions, hyposensitization antigen reaction, and ingestion of drug have been implicated in this form of lymphoid hyperplasia.3,4

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES

Lymphocytoma cutis can be challenging to diagnose, and although it can be suspected clinically, incisional biopsy is usually necessary in order to differentiate it from cutaneous B lymphoma.5

The infiltrate is predominantly nodular (> 90%) and located in the upper and mid dermis (“top heavy”) in lymphocytoma cutis, whereas it can be nodular or diffuse in cutaneous B lymphoma, with sharply demarcated borders that are convex rather than concave. Lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are sometimes present, and the interfollicular cellular population is polymorphic in lymphocytoma cutis (lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils). In lymphocytoma cutis, cells express the phenotype of mature B lymphocytes (CD20, CD79a) and show regular and sharply demarcated networks of CD21+ follicular dendritic cells, whereas in cutaneous B lymphoma these networks are irregular. Light chains are usually polyclonal, although monoclonal populations of B cell in cases of cutaneous lymphocytoma cutis have been described. Extracutaneous involvement is possible in cutaneous B lymphoma but is usually absent in lymphocytoma cutis.

Lymphocytoma cutis typically involutes over a period of months, even with no treatment, as it did in our patient. Otherwise, there are different therapeutic options, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, surgery, and cryosurgery.6 Photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid is an effective and safe modality for the treatment of lymphocytoma cutis and may be cosmetically beneficial.7

- Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38:877–895.

- Albrecht S, Hofstadter S, Artsob H, Chaban O, From L. Lymphadenosis benigna cutis resulting from Borrelia infection (Borrelia lymphocytoma). J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24:621–625.

- Peretz E, Grunwald MH, Cagnano E, Halevy S. Follicular B-cell pseudolymphoma. Australas J Dermatol 2000; 41:48–49.

- Hermes B, Haas N, Grabbe J, Czarnetzki BM. Foreign-body granuloma and IgE-pseudolymphoma after multiple bee stings. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130:780–784.

- Kerl H, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Diagnostic criteria of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Keio J Med 2001; 50:269–273.

- Kuflik AS, Schwartz RA. Lymphocytoma cutis: a series of five patients successfully treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:449–452.

- Takeda H, Kaneko T, Harada K, Matsuzaki Y, Nakano H, Hanada K. Successful treatment of lymphadenosis benigna cutis with topical photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid. Dermatology 2005; 211:264–266.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymphocytoma cutis

- Amelanotic melanoma

- Pyogenic granuloma

A: The correct answer is lymphocytoma cutis. The differential diagnosis of a pink papule on the face of a middle-aged person includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, lymphocytoma cutis, metastatic disease, certain infections, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, connective tissue disease, and some adnexal tumors. Histologic study is a useful diagnostic aid in this context.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cutaneous malignant neoplasm, and although these tumors rarely metastasize, they are capable of gross tissue destruction, particularly those lesions arising on the face. Clinically, this tumor presents as a shiny, pearly nodule with telangiectasias on the surface, as in our patient, but skin biopsy shows large basaloid lobules of varying shape and size forming a relatively circumscribed mass with a “palisade” around the rim of the lobule.

Squamous cell carcinoma manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and elevated, indurate borders, but also as plaques or nodules. The clinical diagnosis should be confirmed with skin biopsy, which reveals atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and horn pearl formation, depending on the differentiation of the tumor.

Amelanotic melanoma is nonpigmented and appears as a pink nodule mimicking basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic study is necessary for the diagnosis, and shows an atypical proliferation of melanocytic cells in the epidermis and dermis.

Pyogenic granuloma is a very common benign vascular lesion considered to be a hyperplastic process or a vascular neoplasm. The lesion typically presents as a red or bluish papule or polyp that bleeds easily, and a reddish homogeneous area surrounded by a white “collarette” is found in most cases. Histologic features of an early lesion resemble granulation tissue and include lobules of capillaries and venules that often radiate from larger, more central vessels.

LYMPHOCYTOMA CUTIS: KEY FEATURES

Lymphocytoma cutis (pseudolymphoma) is a benign reactive polyclonal and inflammatory disorder that most frequently includes B lymphocytes, with a smaller population of T lymphocytes. It infiltrates the skin and resembles rudimentary germinal follicles, as in the present case. The lesion usually presents as an asymptomatic red-brown or violet papule or nodule, 3 mm to 5 cm in diameter, most often on the face, chest, or upper extremities.1 The lesion may be solitary, as in our patient, but lesions may also be grouped or numerous and widespread. It is three times more common in women than in men. It may resolve spontaneously, but it may also recur.

In Europe, lymphocytoma cutis occurs most often in B burgdorferi infection after a tick bite. Lymphocytoma cutis occurs in 1.3% of cases of B burgdorferi infection,2 although other infectious, physical, or chemical agents may produce the same reaction pattern. Tattooing (particularly red areas), acupuncture, vaccination, arthropod reactions, hyposensitization antigen reaction, and ingestion of drug have been implicated in this form of lymphoid hyperplasia.3,4

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES

Lymphocytoma cutis can be challenging to diagnose, and although it can be suspected clinically, incisional biopsy is usually necessary in order to differentiate it from cutaneous B lymphoma.5

The infiltrate is predominantly nodular (> 90%) and located in the upper and mid dermis (“top heavy”) in lymphocytoma cutis, whereas it can be nodular or diffuse in cutaneous B lymphoma, with sharply demarcated borders that are convex rather than concave. Lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are sometimes present, and the interfollicular cellular population is polymorphic in lymphocytoma cutis (lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils). In lymphocytoma cutis, cells express the phenotype of mature B lymphocytes (CD20, CD79a) and show regular and sharply demarcated networks of CD21+ follicular dendritic cells, whereas in cutaneous B lymphoma these networks are irregular. Light chains are usually polyclonal, although monoclonal populations of B cell in cases of cutaneous lymphocytoma cutis have been described. Extracutaneous involvement is possible in cutaneous B lymphoma but is usually absent in lymphocytoma cutis.

Lymphocytoma cutis typically involutes over a period of months, even with no treatment, as it did in our patient. Otherwise, there are different therapeutic options, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, surgery, and cryosurgery.6 Photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid is an effective and safe modality for the treatment of lymphocytoma cutis and may be cosmetically beneficial.7

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymphocytoma cutis

- Amelanotic melanoma

- Pyogenic granuloma

A: The correct answer is lymphocytoma cutis. The differential diagnosis of a pink papule on the face of a middle-aged person includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, lymphocytoma cutis, metastatic disease, certain infections, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, connective tissue disease, and some adnexal tumors. Histologic study is a useful diagnostic aid in this context.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cutaneous malignant neoplasm, and although these tumors rarely metastasize, they are capable of gross tissue destruction, particularly those lesions arising on the face. Clinically, this tumor presents as a shiny, pearly nodule with telangiectasias on the surface, as in our patient, but skin biopsy shows large basaloid lobules of varying shape and size forming a relatively circumscribed mass with a “palisade” around the rim of the lobule.

Squamous cell carcinoma manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and elevated, indurate borders, but also as plaques or nodules. The clinical diagnosis should be confirmed with skin biopsy, which reveals atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and horn pearl formation, depending on the differentiation of the tumor.

Amelanotic melanoma is nonpigmented and appears as a pink nodule mimicking basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic study is necessary for the diagnosis, and shows an atypical proliferation of melanocytic cells in the epidermis and dermis.

Pyogenic granuloma is a very common benign vascular lesion considered to be a hyperplastic process or a vascular neoplasm. The lesion typically presents as a red or bluish papule or polyp that bleeds easily, and a reddish homogeneous area surrounded by a white “collarette” is found in most cases. Histologic features of an early lesion resemble granulation tissue and include lobules of capillaries and venules that often radiate from larger, more central vessels.

LYMPHOCYTOMA CUTIS: KEY FEATURES

Lymphocytoma cutis (pseudolymphoma) is a benign reactive polyclonal and inflammatory disorder that most frequently includes B lymphocytes, with a smaller population of T lymphocytes. It infiltrates the skin and resembles rudimentary germinal follicles, as in the present case. The lesion usually presents as an asymptomatic red-brown or violet papule or nodule, 3 mm to 5 cm in diameter, most often on the face, chest, or upper extremities.1 The lesion may be solitary, as in our patient, but lesions may also be grouped or numerous and widespread. It is three times more common in women than in men. It may resolve spontaneously, but it may also recur.

In Europe, lymphocytoma cutis occurs most often in B burgdorferi infection after a tick bite. Lymphocytoma cutis occurs in 1.3% of cases of B burgdorferi infection,2 although other infectious, physical, or chemical agents may produce the same reaction pattern. Tattooing (particularly red areas), acupuncture, vaccination, arthropod reactions, hyposensitization antigen reaction, and ingestion of drug have been implicated in this form of lymphoid hyperplasia.3,4

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES

Lymphocytoma cutis can be challenging to diagnose, and although it can be suspected clinically, incisional biopsy is usually necessary in order to differentiate it from cutaneous B lymphoma.5

The infiltrate is predominantly nodular (> 90%) and located in the upper and mid dermis (“top heavy”) in lymphocytoma cutis, whereas it can be nodular or diffuse in cutaneous B lymphoma, with sharply demarcated borders that are convex rather than concave. Lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are sometimes present, and the interfollicular cellular population is polymorphic in lymphocytoma cutis (lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils). In lymphocytoma cutis, cells express the phenotype of mature B lymphocytes (CD20, CD79a) and show regular and sharply demarcated networks of CD21+ follicular dendritic cells, whereas in cutaneous B lymphoma these networks are irregular. Light chains are usually polyclonal, although monoclonal populations of B cell in cases of cutaneous lymphocytoma cutis have been described. Extracutaneous involvement is possible in cutaneous B lymphoma but is usually absent in lymphocytoma cutis.

Lymphocytoma cutis typically involutes over a period of months, even with no treatment, as it did in our patient. Otherwise, there are different therapeutic options, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, surgery, and cryosurgery.6 Photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid is an effective and safe modality for the treatment of lymphocytoma cutis and may be cosmetically beneficial.7

- Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38:877–895.

- Albrecht S, Hofstadter S, Artsob H, Chaban O, From L. Lymphadenosis benigna cutis resulting from Borrelia infection (Borrelia lymphocytoma). J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24:621–625.

- Peretz E, Grunwald MH, Cagnano E, Halevy S. Follicular B-cell pseudolymphoma. Australas J Dermatol 2000; 41:48–49.

- Hermes B, Haas N, Grabbe J, Czarnetzki BM. Foreign-body granuloma and IgE-pseudolymphoma after multiple bee stings. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130:780–784.

- Kerl H, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Diagnostic criteria of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Keio J Med 2001; 50:269–273.

- Kuflik AS, Schwartz RA. Lymphocytoma cutis: a series of five patients successfully treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:449–452.

- Takeda H, Kaneko T, Harada K, Matsuzaki Y, Nakano H, Hanada K. Successful treatment of lymphadenosis benigna cutis with topical photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid. Dermatology 2005; 211:264–266.

- Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38:877–895.

- Albrecht S, Hofstadter S, Artsob H, Chaban O, From L. Lymphadenosis benigna cutis resulting from Borrelia infection (Borrelia lymphocytoma). J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24:621–625.

- Peretz E, Grunwald MH, Cagnano E, Halevy S. Follicular B-cell pseudolymphoma. Australas J Dermatol 2000; 41:48–49.

- Hermes B, Haas N, Grabbe J, Czarnetzki BM. Foreign-body granuloma and IgE-pseudolymphoma after multiple bee stings. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130:780–784.

- Kerl H, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Diagnostic criteria of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Keio J Med 2001; 50:269–273.

- Kuflik AS, Schwartz RA. Lymphocytoma cutis: a series of five patients successfully treated with cryosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:449–452.

- Takeda H, Kaneko T, Harada K, Matsuzaki Y, Nakano H, Hanada K. Successful treatment of lymphadenosis benigna cutis with topical photodynamic therapy with delta-aminolevulinic acid. Dermatology 2005; 211:264–266.

An erythematous plaque on the nose

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.