User login

HIV: 3 cases that hid in plain sight

› Rule out human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia. A

› Consider HIV testing in patients with herpes zoster, even for those who do not have risk factors for HIV. B

› Recognize that fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders are some of ways in which a patient with HIV infection may present. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Roberta K, age 35, was referred by her family physician (FP) to a hematologist in November 2007 after her FP noted a platelet count of 63,000/mcL on a screening complete blood count (CBC; normal, 150,000-400,000/mcL). Ms. K also had asthma, hypothyroidism, depression, and migraine headaches. She was given a diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and started on oral prednisone. Her platelet count improved and she was maintained on prednisone 7.5 to 10 mg/d over the next 5 years with periodic dosage increases whenever her platelet count dropped below 50,000/mcL. She saw her FP for regular medical care 3 to 4 times a year and by a hematologist every 6 months.

In April 2012, Ms. K sought treatment from her FP for an acute painful rash consistent with herpes zoster involving the left C5-C6 dermatomes. Due to severe pain and secondary infection, she was admitted to the hospital. During the hospitalization, the inpatient team caring for her obtained a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, which was positive. Her only HIV risk factor was that she’d had 3 lifetime male sex partners.

Ms. K’s initial CD4+ T-cell count was 224 cells/mm3 (normal, nonimmunocompromised adult, 500–1,2001) and her percentage of CD4+ T-cells was 21% (normal, 30%-60%2). Her HIV RNA level was 71,587 copies/mL; the goal of HIV treatment typically is to get this down to <200 copies/mL. She was started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) consisting of fixed-dose emtricitabine/rilpivirine/

tenofovir (200 mg/25 mg/300 mg) and was weaned off prednisone. Six months after starting ART, her CD4+ T-cell count was 450 cells/mm3 and her HIV RNA level was <20 copies/mL. Her most recent platelet count was 148,000/mcL.

The correct diagnosis: Thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

CASE 2 › Christian M, age 40, presented to his FP in February 2010 with worsening cough and shortness of breath that he’d had for 4 weeks. He said he had unintentionally lost 20 pounds since the beginning of the year. He had no medical history of note, but had seen his FP on several occasions over the past few years for treatment of acute minor illnesses and an employment physical. He’d had no occupational exposures that might have affected his lungs, and he did not smoke.

He was initially diagnosed with bronchitis and treated with an oral antibiotic. Two weeks later, his symptoms persisted and Mr. M’s FP referred him to a pulmonologist. A chest x-ray showed an “interstitial process possibly consistent with pneumonia” for which the pulmonologist prescribed levofloxacin and oral prednisone for 10 days. At the follow-up visit, Mr. M had clinically improved. The diagnosis noted by the pulmonologist was “probably viral vs atypical pneumonia.”

Approximately 3 weeks later, in April 2010, Mr. M presented to the emergency department (ED) after several days of fever, cough, and worsening shortness of breath. A chest x-ray showed an interstitial pneumonitis that had worsened since the prior radiography. His pulse oximetry was 87% on room air.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities. The patient was admitted to the hospital and the next day underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. A Gomori methenamine silver stain for Pneumocystis jirovecii was positive, as was an HIV serology. Mr. M’s only reported risk factor for HIV was heterosexual contact. He had been in a stable relationship for over 14 years.

His baseline CD4+ T-cell count was 5 cells/mm3 (1%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies/mL. Several weeks later, Mr. M’s spouse tested positive for HIV. Her CD4+ T-cell count was 45 cells/mm3 (10%) and her viral load was 23,258 copies/mL. Although she was asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, Ms. M was soon started on the same ART regimen as her husband.

The correct diagnosis: Pneumocystis pneumonia with symptoms of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) wasting syndrome.

CASE 3 › Michael L, age 66, was seen by his FP in September 2010 for “preoperative clearance” for elbow surgery. He was in good health but had a platelet count of 67,000/mcL. For unclear reasons, the surgery was cancelled; Mr. L was supposed to be referred to a hematologist for the thrombocytopenia, but this consultation never occurred. The patient did not return to his FP until April 2012, when he complained of feeling “lightheaded and dizzy” for the past few weeks. His examination was remarkable only for mild orthostatic hypotension and he was diagnosed with “dehydration.”

He returned to the office in July 2012 with similar symptoms and a 12-pound weight loss since his last visit. He also complained of short-term memory problems. Lab testing was done and included a chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and CBC, all of which were normal except for a hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 2.4/mcL, and a platelet count of 119,000/mcL. The patient was advised to get a follow-up CBC in one month, but this was not done.

Mr. L returned in November 2012, again complaining of intermittent lightheadedness and fatigue, and said he had been experiencing “mouth sores.” He was given a diagnosis of “probable oral herpes infection” and treated with oral acyclovir. No lab studies were performed.

Mr. L was brought to the ED in February 2013 with fever and mental status changes that had developed over 2 to 3 days. According to a family member, he had also complained of headache for the previous 2 weeks.

A CT scan of his head was normal and he underwent a lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid revealed a white blood cell count of 270/mcL, glucose of 62 mg/dL, and protein of 15 mg/dL. A gram stain was negative, but an India ink stain was positive for encapsulated yeast forms consistent with Cryptococcus. Mr. L was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis and treated with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine. An HIV serology was positive. His CD4+ T-cell count was 8 cells/mm3 (3%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies /mL.

He was discharged from the hospital after 2 weeks and transitioned to oral fluconazole 400 mg/d for the meningitis. One week after discharge, he was started on an ART regimen of darunavir 800 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, and fixed-dose tenofovir/emtricitabine (200 mg/300 mg).

After 6 months of ART, he showed significant clinical improvement, his HIV-RNA level was <20 copies/mL and his CD4+ T-cell count was 136 cells/mm3 (12%). His female partner of 11 years tested negative for HIV.

The correct diagnosis: Cryptococcal meningitis; thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

These 3 cases illustrate what clinicians who treat patients with HIV/AIDS have observed for many years: Physicians often fail to diagnose patients with HIV infection in a timely fashion. HIV can be missed when patients present with clinical signs of immune suppression, such as herpes zoster, as well as when they present with AIDS-defining illnesses such as lymphoma or recurrent pneumonia. Late diagnosis of HIV—typically defined as diagnosis when a patient’s CD4+ T-cell count is <200 cells/mm3—increases morbidity and mortality, as well as health care costs.3

Historically, late HIV testing has been very common in the United States. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report noted that from 1996 to 2005, 38% of patients diagnosed in 34 states had an AIDS diagnosis within one year of testing positive for HIV.4 Chin et al5 performed a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in an HIV clinic in North Carolina between November 2008 and November 2011. The median CD4+ T-cell count at time of diagnosis was 313 cells/mm3 and one-third of patients had a count of <50 cells/mm3. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend ART for all patients diagnosed with HIV infection regardless of CD4+ T-cell count.

The mean number of health care visits in the year before diagnosis was 2.75 (range 0-20). These visits occurred in both primary care settings and the ED. Approximately one-third of patients had complained of HIV-associated signs and symptoms, including recurrent respiratory tract infections, unexplained persistent fevers, and generalized lymphadenopathy prior to diagnosis.

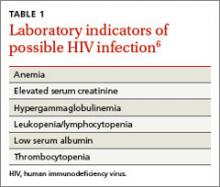

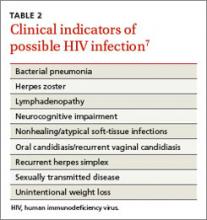

FPs must remain cognizant of the many diverse clinical presentations of patients with HIV/AIDS, including fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders (TABLE 16 and TABLE 27). In the 3 cases described here, the specific conditions the treatment teams failed to identify as indicators of HIV infection were thrombocytopenia, pneumocystis pneumonia, herpes zoster, and cryptococcal meningitis.

Thrombocytopenia has many causes, including infection, medications, lymphoproliferative disorders, liver disease, and connective tissue diseases. However, low platelet counts are often seen in individuals with HIV infection.

Before the introduction of ART, the incidence of thrombocytopenia in HIV patients was 40%.8 Since then, this condition is less common, but HIV should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia or making a diagnosis of “idiopathic thrombocytopenia” (as was Ms. K’s initial diagnosis).

The incidence of cytopenias in general correlates directly with the degree of immunosuppression. However, isolated hematologic abnormalities, including anemia and leukopenia, may be the initial presentation of HIV infection.9 As a result, HIV must be considered in the assessment of all patients who present with any hematologic abnormality.

Pneumocystis pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii has been a longtime AIDS-defining illness and is the most common opportunistic infection in patients with advanced HIV infection.10 A slow, indolent course is common, with symptoms of cough and dyspnea progressing over weeks to months (as observed in Mr. M). Radiographs will show diffuse or isolated ground-glass opacities. Partial improvement is sometimes seen in patients with unknown HIV infection who are treated with short courses of prednisone and antibiotics.11 Patients with untreated HIV infection and CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/mm3 will develop worsening hypoxemia and, in some cases, fulminant respiratory failure.

Herpes zoster is common in older adults and often indicates a weakened immune system. The incidence of zoster among adults with HIV is more than 15-fold higher than it is among age-matched varicella-zoster virus-infected immunocompetent people.12 A study from the early 1990s noted that nearly 30 cases per year were observed for every 1000 HIV-infected adults.12

Zoster tends to occur in patients with CD4+ counts >200 mm3. If HIV is not diagnosed when a patient presents with zoster, it may be several years before the CD4+ T-cell count declines to a level at which the patient will experience an opportunistic infection or malignancy. A diagnosis of herpes zoster should prompt you to consider HIV and test for infection, even in patients who do not have risk factors associated with HIV, as was the case with Ms. K.

Cryptococcal meningitis. Infections caused by Cryptococcus neoformans are now relatively infrequent in the United States but remain a major cause of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in the developing world.13 Symptoms of cryptococcal meningitis, such as those observed in Mr. L, usually begin in an indolent fashion over one to 2 weeks. The most common presenting symptoms are fever, headache, and malaise. Nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and vomiting occur in only about 25% of patients.13 Mortality remains high for this infection if it is not treated aggressively.

Implement routine HIV screening, avoid “framing bias”

Prompt diagnosis of HIV infection is essential for several reasons. For one, it lowers the risk of life-threatening opportunistic infections and malignancies. For another, it can help to prevent transmission of HIV infection to partners and contacts.

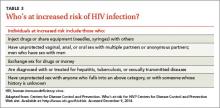

Historically, HIV testing had been considered primarily for individuals with certain high-risk factors that increase their likelihood of infection (TABLE 3). However, in 2006, recognizing that risk-based testing failed to identify a significant number of people with HIV, the CDC began to recommend opt-out routine HIV screening for all adolescents and adults ages 13 to 64 years.14 In November 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued similar recommendations.15

In fact, routine screening would have likely led to earlier identification of HIV in 2 of the 3 patients in the cases described here. However, only 54% of US adults ages 18 to 64 years report ever having been tested for HIV, and among the 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States, approximately 15% do not know they are infected.16

Physicians are frequently subject to “framing bias” in which diagnostic capabilities are limited to how we perceive individual patients. Finn et al11 reported a case of a 65-year-old “grandfather” with COPD who was eventually diagnosed with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and subsequently found to be HIV-infected, with a CD4+ T-cell count of 5 cells/mm3. A similar case involving an 81-year-old patient was reported in the literature in 2009 and raised the question of whether patients older than the currently recommended age of 64 years should also undergo routine screening for HIV.17

The 3 patients described here illustrate a similar framing bias in that none of the physicians who cared for them in an outpatient setting considered their patient to be at risk for HIV infection.

To avoid this type of bias, we must remain vigilant in assessing risk factors for HIV infection while obtaining a patient’s medical history. However, even under ideal circumstances, our patients may not be forthcoming about their sexual behavior or drug use. Moreover, many others may be unaware that they were exposed to HIV. Consequently, FPs and other primary care providers should continue to incorporate routine HIV screening into their practices but also remember specific HIV risk factors and clinical indicators of disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Lancaster General Hospital Comprehensive Care for HIV, 554 North Duke Street, 3rd Floor, Lancaster, PA 17602; jtkirchn@lghealth.org

1. AIDS.gov. CD4 count. AIDS.gov Web site. Available at: http://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/understand-your-test-results/cd4-count/. Accessed December 9, 2014.

2. International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. CD4 cell tests. AIDS InfoNet Web site. Available at: http://www.aidsinfonet.org/uploaded/factsheets/13_eng_124.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2014.

3. Farnham PG, Gopalappa C, Sansom SL, et al. Updates of lifetime costs of care and quality-of-life estimates for HIV-infected persons in the United States: late versus early diagnosis and entry into care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013; 64:183-189.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Late HIV testing - 34 states, 1996-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:661-665.

5. Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, et al. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013; 27:392-397.

6. Northfelt DW. Hematologic manifestations of HIV. University of California San Francisco HIV Insite Web site. Available at: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-00&doc=kb-04-01-09. Accessed December 10, 2014.

7. Damery S, Nichols L, Holder R, et al. Assessing the predictive value of HIV indicator conditions in general practice: a case-control study using the THIN database. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e370-e377.

8. Morris L, Distenfeld A, Amorosi E, et al. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(6 pt 1):714-717.

9. Friel TJ, Scadden DT. Hematologic manifestations of HIV infection: Anemia. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hematologic-manifestations-of-hiv-infection-anemia. Accessed December 10, 2014.

10. Gilroy SA, Bennett NJ. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 32:775-782.

11. Finn KM, Ginns LC, Robbins GK, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2014. A 65-year-old man with dyspnea and progressively worsening lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:2521-2530.

12. Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, et al. Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1153-1156.

13. Sloan DJ, Parris V. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology and therapeutic options. Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 6:169-182.

14. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-17.

15. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51-60.

16. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/hiv-testing-in-the-united-states/. Accessed December 2, 2014.

17. Stone VE, Bounds BC, Muse VV, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 29-2009. An 81-year-old man with weight loss, odynophagia, and failure to thrive. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1189-1198.

› Rule out human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia. A

› Consider HIV testing in patients with herpes zoster, even for those who do not have risk factors for HIV. B

› Recognize that fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders are some of ways in which a patient with HIV infection may present. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Roberta K, age 35, was referred by her family physician (FP) to a hematologist in November 2007 after her FP noted a platelet count of 63,000/mcL on a screening complete blood count (CBC; normal, 150,000-400,000/mcL). Ms. K also had asthma, hypothyroidism, depression, and migraine headaches. She was given a diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and started on oral prednisone. Her platelet count improved and she was maintained on prednisone 7.5 to 10 mg/d over the next 5 years with periodic dosage increases whenever her platelet count dropped below 50,000/mcL. She saw her FP for regular medical care 3 to 4 times a year and by a hematologist every 6 months.

In April 2012, Ms. K sought treatment from her FP for an acute painful rash consistent with herpes zoster involving the left C5-C6 dermatomes. Due to severe pain and secondary infection, she was admitted to the hospital. During the hospitalization, the inpatient team caring for her obtained a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, which was positive. Her only HIV risk factor was that she’d had 3 lifetime male sex partners.

Ms. K’s initial CD4+ T-cell count was 224 cells/mm3 (normal, nonimmunocompromised adult, 500–1,2001) and her percentage of CD4+ T-cells was 21% (normal, 30%-60%2). Her HIV RNA level was 71,587 copies/mL; the goal of HIV treatment typically is to get this down to <200 copies/mL. She was started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) consisting of fixed-dose emtricitabine/rilpivirine/

tenofovir (200 mg/25 mg/300 mg) and was weaned off prednisone. Six months after starting ART, her CD4+ T-cell count was 450 cells/mm3 and her HIV RNA level was <20 copies/mL. Her most recent platelet count was 148,000/mcL.

The correct diagnosis: Thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

CASE 2 › Christian M, age 40, presented to his FP in February 2010 with worsening cough and shortness of breath that he’d had for 4 weeks. He said he had unintentionally lost 20 pounds since the beginning of the year. He had no medical history of note, but had seen his FP on several occasions over the past few years for treatment of acute minor illnesses and an employment physical. He’d had no occupational exposures that might have affected his lungs, and he did not smoke.

He was initially diagnosed with bronchitis and treated with an oral antibiotic. Two weeks later, his symptoms persisted and Mr. M’s FP referred him to a pulmonologist. A chest x-ray showed an “interstitial process possibly consistent with pneumonia” for which the pulmonologist prescribed levofloxacin and oral prednisone for 10 days. At the follow-up visit, Mr. M had clinically improved. The diagnosis noted by the pulmonologist was “probably viral vs atypical pneumonia.”

Approximately 3 weeks later, in April 2010, Mr. M presented to the emergency department (ED) after several days of fever, cough, and worsening shortness of breath. A chest x-ray showed an interstitial pneumonitis that had worsened since the prior radiography. His pulse oximetry was 87% on room air.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities. The patient was admitted to the hospital and the next day underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. A Gomori methenamine silver stain for Pneumocystis jirovecii was positive, as was an HIV serology. Mr. M’s only reported risk factor for HIV was heterosexual contact. He had been in a stable relationship for over 14 years.

His baseline CD4+ T-cell count was 5 cells/mm3 (1%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies/mL. Several weeks later, Mr. M’s spouse tested positive for HIV. Her CD4+ T-cell count was 45 cells/mm3 (10%) and her viral load was 23,258 copies/mL. Although she was asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, Ms. M was soon started on the same ART regimen as her husband.

The correct diagnosis: Pneumocystis pneumonia with symptoms of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) wasting syndrome.

CASE 3 › Michael L, age 66, was seen by his FP in September 2010 for “preoperative clearance” for elbow surgery. He was in good health but had a platelet count of 67,000/mcL. For unclear reasons, the surgery was cancelled; Mr. L was supposed to be referred to a hematologist for the thrombocytopenia, but this consultation never occurred. The patient did not return to his FP until April 2012, when he complained of feeling “lightheaded and dizzy” for the past few weeks. His examination was remarkable only for mild orthostatic hypotension and he was diagnosed with “dehydration.”

He returned to the office in July 2012 with similar symptoms and a 12-pound weight loss since his last visit. He also complained of short-term memory problems. Lab testing was done and included a chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and CBC, all of which were normal except for a hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 2.4/mcL, and a platelet count of 119,000/mcL. The patient was advised to get a follow-up CBC in one month, but this was not done.

Mr. L returned in November 2012, again complaining of intermittent lightheadedness and fatigue, and said he had been experiencing “mouth sores.” He was given a diagnosis of “probable oral herpes infection” and treated with oral acyclovir. No lab studies were performed.

Mr. L was brought to the ED in February 2013 with fever and mental status changes that had developed over 2 to 3 days. According to a family member, he had also complained of headache for the previous 2 weeks.

A CT scan of his head was normal and he underwent a lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid revealed a white blood cell count of 270/mcL, glucose of 62 mg/dL, and protein of 15 mg/dL. A gram stain was negative, but an India ink stain was positive for encapsulated yeast forms consistent with Cryptococcus. Mr. L was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis and treated with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine. An HIV serology was positive. His CD4+ T-cell count was 8 cells/mm3 (3%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies /mL.

He was discharged from the hospital after 2 weeks and transitioned to oral fluconazole 400 mg/d for the meningitis. One week after discharge, he was started on an ART regimen of darunavir 800 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, and fixed-dose tenofovir/emtricitabine (200 mg/300 mg).

After 6 months of ART, he showed significant clinical improvement, his HIV-RNA level was <20 copies/mL and his CD4+ T-cell count was 136 cells/mm3 (12%). His female partner of 11 years tested negative for HIV.

The correct diagnosis: Cryptococcal meningitis; thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

These 3 cases illustrate what clinicians who treat patients with HIV/AIDS have observed for many years: Physicians often fail to diagnose patients with HIV infection in a timely fashion. HIV can be missed when patients present with clinical signs of immune suppression, such as herpes zoster, as well as when they present with AIDS-defining illnesses such as lymphoma or recurrent pneumonia. Late diagnosis of HIV—typically defined as diagnosis when a patient’s CD4+ T-cell count is <200 cells/mm3—increases morbidity and mortality, as well as health care costs.3

Historically, late HIV testing has been very common in the United States. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report noted that from 1996 to 2005, 38% of patients diagnosed in 34 states had an AIDS diagnosis within one year of testing positive for HIV.4 Chin et al5 performed a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in an HIV clinic in North Carolina between November 2008 and November 2011. The median CD4+ T-cell count at time of diagnosis was 313 cells/mm3 and one-third of patients had a count of <50 cells/mm3. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend ART for all patients diagnosed with HIV infection regardless of CD4+ T-cell count.

The mean number of health care visits in the year before diagnosis was 2.75 (range 0-20). These visits occurred in both primary care settings and the ED. Approximately one-third of patients had complained of HIV-associated signs and symptoms, including recurrent respiratory tract infections, unexplained persistent fevers, and generalized lymphadenopathy prior to diagnosis.

FPs must remain cognizant of the many diverse clinical presentations of patients with HIV/AIDS, including fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders (TABLE 16 and TABLE 27). In the 3 cases described here, the specific conditions the treatment teams failed to identify as indicators of HIV infection were thrombocytopenia, pneumocystis pneumonia, herpes zoster, and cryptococcal meningitis.

Thrombocytopenia has many causes, including infection, medications, lymphoproliferative disorders, liver disease, and connective tissue diseases. However, low platelet counts are often seen in individuals with HIV infection.

Before the introduction of ART, the incidence of thrombocytopenia in HIV patients was 40%.8 Since then, this condition is less common, but HIV should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia or making a diagnosis of “idiopathic thrombocytopenia” (as was Ms. K’s initial diagnosis).

The incidence of cytopenias in general correlates directly with the degree of immunosuppression. However, isolated hematologic abnormalities, including anemia and leukopenia, may be the initial presentation of HIV infection.9 As a result, HIV must be considered in the assessment of all patients who present with any hematologic abnormality.

Pneumocystis pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii has been a longtime AIDS-defining illness and is the most common opportunistic infection in patients with advanced HIV infection.10 A slow, indolent course is common, with symptoms of cough and dyspnea progressing over weeks to months (as observed in Mr. M). Radiographs will show diffuse or isolated ground-glass opacities. Partial improvement is sometimes seen in patients with unknown HIV infection who are treated with short courses of prednisone and antibiotics.11 Patients with untreated HIV infection and CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/mm3 will develop worsening hypoxemia and, in some cases, fulminant respiratory failure.

Herpes zoster is common in older adults and often indicates a weakened immune system. The incidence of zoster among adults with HIV is more than 15-fold higher than it is among age-matched varicella-zoster virus-infected immunocompetent people.12 A study from the early 1990s noted that nearly 30 cases per year were observed for every 1000 HIV-infected adults.12

Zoster tends to occur in patients with CD4+ counts >200 mm3. If HIV is not diagnosed when a patient presents with zoster, it may be several years before the CD4+ T-cell count declines to a level at which the patient will experience an opportunistic infection or malignancy. A diagnosis of herpes zoster should prompt you to consider HIV and test for infection, even in patients who do not have risk factors associated with HIV, as was the case with Ms. K.

Cryptococcal meningitis. Infections caused by Cryptococcus neoformans are now relatively infrequent in the United States but remain a major cause of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in the developing world.13 Symptoms of cryptococcal meningitis, such as those observed in Mr. L, usually begin in an indolent fashion over one to 2 weeks. The most common presenting symptoms are fever, headache, and malaise. Nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and vomiting occur in only about 25% of patients.13 Mortality remains high for this infection if it is not treated aggressively.

Implement routine HIV screening, avoid “framing bias”

Prompt diagnosis of HIV infection is essential for several reasons. For one, it lowers the risk of life-threatening opportunistic infections and malignancies. For another, it can help to prevent transmission of HIV infection to partners and contacts.

Historically, HIV testing had been considered primarily for individuals with certain high-risk factors that increase their likelihood of infection (TABLE 3). However, in 2006, recognizing that risk-based testing failed to identify a significant number of people with HIV, the CDC began to recommend opt-out routine HIV screening for all adolescents and adults ages 13 to 64 years.14 In November 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued similar recommendations.15

In fact, routine screening would have likely led to earlier identification of HIV in 2 of the 3 patients in the cases described here. However, only 54% of US adults ages 18 to 64 years report ever having been tested for HIV, and among the 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States, approximately 15% do not know they are infected.16

Physicians are frequently subject to “framing bias” in which diagnostic capabilities are limited to how we perceive individual patients. Finn et al11 reported a case of a 65-year-old “grandfather” with COPD who was eventually diagnosed with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and subsequently found to be HIV-infected, with a CD4+ T-cell count of 5 cells/mm3. A similar case involving an 81-year-old patient was reported in the literature in 2009 and raised the question of whether patients older than the currently recommended age of 64 years should also undergo routine screening for HIV.17

The 3 patients described here illustrate a similar framing bias in that none of the physicians who cared for them in an outpatient setting considered their patient to be at risk for HIV infection.

To avoid this type of bias, we must remain vigilant in assessing risk factors for HIV infection while obtaining a patient’s medical history. However, even under ideal circumstances, our patients may not be forthcoming about their sexual behavior or drug use. Moreover, many others may be unaware that they were exposed to HIV. Consequently, FPs and other primary care providers should continue to incorporate routine HIV screening into their practices but also remember specific HIV risk factors and clinical indicators of disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Lancaster General Hospital Comprehensive Care for HIV, 554 North Duke Street, 3rd Floor, Lancaster, PA 17602; jtkirchn@lghealth.org

› Rule out human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia. A

› Consider HIV testing in patients with herpes zoster, even for those who do not have risk factors for HIV. B

› Recognize that fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders are some of ways in which a patient with HIV infection may present. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Roberta K, age 35, was referred by her family physician (FP) to a hematologist in November 2007 after her FP noted a platelet count of 63,000/mcL on a screening complete blood count (CBC; normal, 150,000-400,000/mcL). Ms. K also had asthma, hypothyroidism, depression, and migraine headaches. She was given a diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and started on oral prednisone. Her platelet count improved and she was maintained on prednisone 7.5 to 10 mg/d over the next 5 years with periodic dosage increases whenever her platelet count dropped below 50,000/mcL. She saw her FP for regular medical care 3 to 4 times a year and by a hematologist every 6 months.

In April 2012, Ms. K sought treatment from her FP for an acute painful rash consistent with herpes zoster involving the left C5-C6 dermatomes. Due to severe pain and secondary infection, she was admitted to the hospital. During the hospitalization, the inpatient team caring for her obtained a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, which was positive. Her only HIV risk factor was that she’d had 3 lifetime male sex partners.

Ms. K’s initial CD4+ T-cell count was 224 cells/mm3 (normal, nonimmunocompromised adult, 500–1,2001) and her percentage of CD4+ T-cells was 21% (normal, 30%-60%2). Her HIV RNA level was 71,587 copies/mL; the goal of HIV treatment typically is to get this down to <200 copies/mL. She was started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) consisting of fixed-dose emtricitabine/rilpivirine/

tenofovir (200 mg/25 mg/300 mg) and was weaned off prednisone. Six months after starting ART, her CD4+ T-cell count was 450 cells/mm3 and her HIV RNA level was <20 copies/mL. Her most recent platelet count was 148,000/mcL.

The correct diagnosis: Thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

CASE 2 › Christian M, age 40, presented to his FP in February 2010 with worsening cough and shortness of breath that he’d had for 4 weeks. He said he had unintentionally lost 20 pounds since the beginning of the year. He had no medical history of note, but had seen his FP on several occasions over the past few years for treatment of acute minor illnesses and an employment physical. He’d had no occupational exposures that might have affected his lungs, and he did not smoke.

He was initially diagnosed with bronchitis and treated with an oral antibiotic. Two weeks later, his symptoms persisted and Mr. M’s FP referred him to a pulmonologist. A chest x-ray showed an “interstitial process possibly consistent with pneumonia” for which the pulmonologist prescribed levofloxacin and oral prednisone for 10 days. At the follow-up visit, Mr. M had clinically improved. The diagnosis noted by the pulmonologist was “probably viral vs atypical pneumonia.”

Approximately 3 weeks later, in April 2010, Mr. M presented to the emergency department (ED) after several days of fever, cough, and worsening shortness of breath. A chest x-ray showed an interstitial pneumonitis that had worsened since the prior radiography. His pulse oximetry was 87% on room air.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities. The patient was admitted to the hospital and the next day underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. A Gomori methenamine silver stain for Pneumocystis jirovecii was positive, as was an HIV serology. Mr. M’s only reported risk factor for HIV was heterosexual contact. He had been in a stable relationship for over 14 years.

His baseline CD4+ T-cell count was 5 cells/mm3 (1%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies/mL. Several weeks later, Mr. M’s spouse tested positive for HIV. Her CD4+ T-cell count was 45 cells/mm3 (10%) and her viral load was 23,258 copies/mL. Although she was asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, Ms. M was soon started on the same ART regimen as her husband.

The correct diagnosis: Pneumocystis pneumonia with symptoms of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) wasting syndrome.

CASE 3 › Michael L, age 66, was seen by his FP in September 2010 for “preoperative clearance” for elbow surgery. He was in good health but had a platelet count of 67,000/mcL. For unclear reasons, the surgery was cancelled; Mr. L was supposed to be referred to a hematologist for the thrombocytopenia, but this consultation never occurred. The patient did not return to his FP until April 2012, when he complained of feeling “lightheaded and dizzy” for the past few weeks. His examination was remarkable only for mild orthostatic hypotension and he was diagnosed with “dehydration.”

He returned to the office in July 2012 with similar symptoms and a 12-pound weight loss since his last visit. He also complained of short-term memory problems. Lab testing was done and included a chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and CBC, all of which were normal except for a hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 2.4/mcL, and a platelet count of 119,000/mcL. The patient was advised to get a follow-up CBC in one month, but this was not done.

Mr. L returned in November 2012, again complaining of intermittent lightheadedness and fatigue, and said he had been experiencing “mouth sores.” He was given a diagnosis of “probable oral herpes infection” and treated with oral acyclovir. No lab studies were performed.

Mr. L was brought to the ED in February 2013 with fever and mental status changes that had developed over 2 to 3 days. According to a family member, he had also complained of headache for the previous 2 weeks.

A CT scan of his head was normal and he underwent a lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid revealed a white blood cell count of 270/mcL, glucose of 62 mg/dL, and protein of 15 mg/dL. A gram stain was negative, but an India ink stain was positive for encapsulated yeast forms consistent with Cryptococcus. Mr. L was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis and treated with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine. An HIV serology was positive. His CD4+ T-cell count was 8 cells/mm3 (3%) and his HIV RNA level was >500,000 copies /mL.

He was discharged from the hospital after 2 weeks and transitioned to oral fluconazole 400 mg/d for the meningitis. One week after discharge, he was started on an ART regimen of darunavir 800 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, and fixed-dose tenofovir/emtricitabine (200 mg/300 mg).

After 6 months of ART, he showed significant clinical improvement, his HIV-RNA level was <20 copies/mL and his CD4+ T-cell count was 136 cells/mm3 (12%). His female partner of 11 years tested negative for HIV.

The correct diagnosis: Cryptococcal meningitis; thrombocytopenia secondary to HIV infection.

These 3 cases illustrate what clinicians who treat patients with HIV/AIDS have observed for many years: Physicians often fail to diagnose patients with HIV infection in a timely fashion. HIV can be missed when patients present with clinical signs of immune suppression, such as herpes zoster, as well as when they present with AIDS-defining illnesses such as lymphoma or recurrent pneumonia. Late diagnosis of HIV—typically defined as diagnosis when a patient’s CD4+ T-cell count is <200 cells/mm3—increases morbidity and mortality, as well as health care costs.3

Historically, late HIV testing has been very common in the United States. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report noted that from 1996 to 2005, 38% of patients diagnosed in 34 states had an AIDS diagnosis within one year of testing positive for HIV.4 Chin et al5 performed a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in an HIV clinic in North Carolina between November 2008 and November 2011. The median CD4+ T-cell count at time of diagnosis was 313 cells/mm3 and one-third of patients had a count of <50 cells/mm3. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend ART for all patients diagnosed with HIV infection regardless of CD4+ T-cell count.

The mean number of health care visits in the year before diagnosis was 2.75 (range 0-20). These visits occurred in both primary care settings and the ED. Approximately one-third of patients had complained of HIV-associated signs and symptoms, including recurrent respiratory tract infections, unexplained persistent fevers, and generalized lymphadenopathy prior to diagnosis.

FPs must remain cognizant of the many diverse clinical presentations of patients with HIV/AIDS, including fatigue, weight loss, unexplained rashes, and hematologic disorders (TABLE 16 and TABLE 27). In the 3 cases described here, the specific conditions the treatment teams failed to identify as indicators of HIV infection were thrombocytopenia, pneumocystis pneumonia, herpes zoster, and cryptococcal meningitis.

Thrombocytopenia has many causes, including infection, medications, lymphoproliferative disorders, liver disease, and connective tissue diseases. However, low platelet counts are often seen in individuals with HIV infection.

Before the introduction of ART, the incidence of thrombocytopenia in HIV patients was 40%.8 Since then, this condition is less common, but HIV should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for thrombocytopenia or making a diagnosis of “idiopathic thrombocytopenia” (as was Ms. K’s initial diagnosis).

The incidence of cytopenias in general correlates directly with the degree of immunosuppression. However, isolated hematologic abnormalities, including anemia and leukopenia, may be the initial presentation of HIV infection.9 As a result, HIV must be considered in the assessment of all patients who present with any hematologic abnormality.

Pneumocystis pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii has been a longtime AIDS-defining illness and is the most common opportunistic infection in patients with advanced HIV infection.10 A slow, indolent course is common, with symptoms of cough and dyspnea progressing over weeks to months (as observed in Mr. M). Radiographs will show diffuse or isolated ground-glass opacities. Partial improvement is sometimes seen in patients with unknown HIV infection who are treated with short courses of prednisone and antibiotics.11 Patients with untreated HIV infection and CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/mm3 will develop worsening hypoxemia and, in some cases, fulminant respiratory failure.

Herpes zoster is common in older adults and often indicates a weakened immune system. The incidence of zoster among adults with HIV is more than 15-fold higher than it is among age-matched varicella-zoster virus-infected immunocompetent people.12 A study from the early 1990s noted that nearly 30 cases per year were observed for every 1000 HIV-infected adults.12

Zoster tends to occur in patients with CD4+ counts >200 mm3. If HIV is not diagnosed when a patient presents with zoster, it may be several years before the CD4+ T-cell count declines to a level at which the patient will experience an opportunistic infection or malignancy. A diagnosis of herpes zoster should prompt you to consider HIV and test for infection, even in patients who do not have risk factors associated with HIV, as was the case with Ms. K.

Cryptococcal meningitis. Infections caused by Cryptococcus neoformans are now relatively infrequent in the United States but remain a major cause of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in the developing world.13 Symptoms of cryptococcal meningitis, such as those observed in Mr. L, usually begin in an indolent fashion over one to 2 weeks. The most common presenting symptoms are fever, headache, and malaise. Nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and vomiting occur in only about 25% of patients.13 Mortality remains high for this infection if it is not treated aggressively.

Implement routine HIV screening, avoid “framing bias”

Prompt diagnosis of HIV infection is essential for several reasons. For one, it lowers the risk of life-threatening opportunistic infections and malignancies. For another, it can help to prevent transmission of HIV infection to partners and contacts.

Historically, HIV testing had been considered primarily for individuals with certain high-risk factors that increase their likelihood of infection (TABLE 3). However, in 2006, recognizing that risk-based testing failed to identify a significant number of people with HIV, the CDC began to recommend opt-out routine HIV screening for all adolescents and adults ages 13 to 64 years.14 In November 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued similar recommendations.15

In fact, routine screening would have likely led to earlier identification of HIV in 2 of the 3 patients in the cases described here. However, only 54% of US adults ages 18 to 64 years report ever having been tested for HIV, and among the 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States, approximately 15% do not know they are infected.16

Physicians are frequently subject to “framing bias” in which diagnostic capabilities are limited to how we perceive individual patients. Finn et al11 reported a case of a 65-year-old “grandfather” with COPD who was eventually diagnosed with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and subsequently found to be HIV-infected, with a CD4+ T-cell count of 5 cells/mm3. A similar case involving an 81-year-old patient was reported in the literature in 2009 and raised the question of whether patients older than the currently recommended age of 64 years should also undergo routine screening for HIV.17

The 3 patients described here illustrate a similar framing bias in that none of the physicians who cared for them in an outpatient setting considered their patient to be at risk for HIV infection.

To avoid this type of bias, we must remain vigilant in assessing risk factors for HIV infection while obtaining a patient’s medical history. However, even under ideal circumstances, our patients may not be forthcoming about their sexual behavior or drug use. Moreover, many others may be unaware that they were exposed to HIV. Consequently, FPs and other primary care providers should continue to incorporate routine HIV screening into their practices but also remember specific HIV risk factors and clinical indicators of disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Lancaster General Hospital Comprehensive Care for HIV, 554 North Duke Street, 3rd Floor, Lancaster, PA 17602; jtkirchn@lghealth.org

1. AIDS.gov. CD4 count. AIDS.gov Web site. Available at: http://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/understand-your-test-results/cd4-count/. Accessed December 9, 2014.

2. International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. CD4 cell tests. AIDS InfoNet Web site. Available at: http://www.aidsinfonet.org/uploaded/factsheets/13_eng_124.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2014.

3. Farnham PG, Gopalappa C, Sansom SL, et al. Updates of lifetime costs of care and quality-of-life estimates for HIV-infected persons in the United States: late versus early diagnosis and entry into care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013; 64:183-189.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Late HIV testing - 34 states, 1996-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:661-665.

5. Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, et al. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013; 27:392-397.

6. Northfelt DW. Hematologic manifestations of HIV. University of California San Francisco HIV Insite Web site. Available at: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-00&doc=kb-04-01-09. Accessed December 10, 2014.

7. Damery S, Nichols L, Holder R, et al. Assessing the predictive value of HIV indicator conditions in general practice: a case-control study using the THIN database. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e370-e377.

8. Morris L, Distenfeld A, Amorosi E, et al. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(6 pt 1):714-717.

9. Friel TJ, Scadden DT. Hematologic manifestations of HIV infection: Anemia. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hematologic-manifestations-of-hiv-infection-anemia. Accessed December 10, 2014.

10. Gilroy SA, Bennett NJ. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 32:775-782.

11. Finn KM, Ginns LC, Robbins GK, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2014. A 65-year-old man with dyspnea and progressively worsening lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:2521-2530.

12. Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, et al. Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1153-1156.

13. Sloan DJ, Parris V. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology and therapeutic options. Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 6:169-182.

14. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-17.

15. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51-60.

16. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/hiv-testing-in-the-united-states/. Accessed December 2, 2014.

17. Stone VE, Bounds BC, Muse VV, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 29-2009. An 81-year-old man with weight loss, odynophagia, and failure to thrive. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1189-1198.

1. AIDS.gov. CD4 count. AIDS.gov Web site. Available at: http://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/understand-your-test-results/cd4-count/. Accessed December 9, 2014.

2. International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. CD4 cell tests. AIDS InfoNet Web site. Available at: http://www.aidsinfonet.org/uploaded/factsheets/13_eng_124.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2014.

3. Farnham PG, Gopalappa C, Sansom SL, et al. Updates of lifetime costs of care and quality-of-life estimates for HIV-infected persons in the United States: late versus early diagnosis and entry into care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013; 64:183-189.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Late HIV testing - 34 states, 1996-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:661-665.

5. Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, et al. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013; 27:392-397.

6. Northfelt DW. Hematologic manifestations of HIV. University of California San Francisco HIV Insite Web site. Available at: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-00&doc=kb-04-01-09. Accessed December 10, 2014.

7. Damery S, Nichols L, Holder R, et al. Assessing the predictive value of HIV indicator conditions in general practice: a case-control study using the THIN database. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e370-e377.

8. Morris L, Distenfeld A, Amorosi E, et al. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(6 pt 1):714-717.

9. Friel TJ, Scadden DT. Hematologic manifestations of HIV infection: Anemia. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hematologic-manifestations-of-hiv-infection-anemia. Accessed December 10, 2014.

10. Gilroy SA, Bennett NJ. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 32:775-782.

11. Finn KM, Ginns LC, Robbins GK, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2014. A 65-year-old man with dyspnea and progressively worsening lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:2521-2530.

12. Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, et al. Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1153-1156.

13. Sloan DJ, Parris V. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology and therapeutic options. Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 6:169-182.

14. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-17.

15. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51-60.

16. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/hiv-testing-in-the-united-states/. Accessed December 2, 2014.

17. Stone VE, Bounds BC, Muse VV, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 29-2009. An 81-year-old man with weight loss, odynophagia, and failure to thrive. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1189-1198.

HIV screening: How we can do better

› Screen all adolescents and adults ages 15 to 65 years for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A

› Screen younger adolescents and older adults who are at increased risk for HIV infection on an annual basis. A

› Screen all pregnant women for HIV infection, including those who are in labor and who are untested or whose HIV status is unknown. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For the first 15 years of the epidemic, human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDs) was uniformly fatal. Between 1981 and 1996, approximately 362,000 people in the United States succumbed to the disease.1 That began to change in the mid 1990s, though, when highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) came into routine use. From that point forward, HIV became a chronic, manageable disease for most patients; an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States are now living with HIV infection.2

Unfortunately, the number of new infections continues to grow. There are more than 50,000 new infections in the United States each year,2 and an estimated approximately 200,000 people have it but are undiagnosed, leading to further spread of the disease.3 The Office of National AIDS Policy has issued a National HIV/AIDS Strategy that seeks to reduce new infections by 25% in 2015, in part by identifying people with the disease who do not know their HIV status.4

But screening still has not gotten the uptake by clinicians that health officials would like.

Lack of awareness by physicians? Or an unwillingness of patients?

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began recommending routine HIV screening for individuals between the ages of 13 and 64, with patients given the ability to opt out of such testing.5 That same year, the CDC also removed some prior barriers to testing, such as requiring written consent and pretest counseling. But as of 2009, fewer than 50% of US adults had ever been tested for HIV6—possibly the result of physicians being unaware of the guidelines, patients being unwilling to be tested, and/or reimbursement issues.

Conflicting recommendations may have played a role. When the CDC released its 2006 recommendations, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) felt there was insufficient evidence to support routine HIV screening and issued a grade C recommendation. At that time, the USPSTF recommended that only high-risk individuals and pregnant women be tested (A recommendation, meaning there was high certainty that the net benefit was substantial).

However, in April 2013, based on new evidence regarding the clinical and public health benefits of early identification of HIV infection and subsequent treatment, the USPSTF updated its recommendations. The USPSTF now encourages clinicians to screen all adolescents and adults age 15 to 65 years for HIV (A recommendation).7 Shortly thereafter, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) also endorsed routine HIV screening, although the AAFP calls for such screening to begin at age 18.8

Insurance now covers it… A USPSTF A recommendation carries significant health policy implications because the Affordable Care Act requires private and public health insurance plans to cover preventive services recommended by USPSTF.9

Integrating screening into your practice

Serologic tests have come a long way. The first HIV antibody test was an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) that was introduced in 1985 and used mainly to screen the blood supply. This first-generation EIA identified only immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to HIV type 1 (HIV-1). More sensitive and specific second- and third-generation EIAs have since been developed to detect both IgG and IgM antibodies, as well as antibodies to HIV-2. The third-generation assays also can detect antibodies as soon as 3 weeks after infection.

The fourth-generation EIAs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 201010 and are the first step in the CDC’s current HIV diagnostic testing algorithm. These tests can detect HIV-1/HIV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies and also p24 antigen, which is present within 7 days of the appearance of HIV RNA.11 The fourth-generation assay allows for reliable detection within about 2 weeks of infection (FIGURE 1).10

Rapid HIV tests are also an option.12 These tests can detect IgG and IgM antibodies in samples of saliva, whole blood, serum, and plasma. Results of rapid tests usually are available in 20 to 30 minutes and allow physicians to give patients the results while they are still in the office. In 2013 the FDA approved a combination p24 antigen/antibody rapid HIV assay that according to the manufacturer can detect infection earlier than other currently available rapid tests.13

When rapid tests are most useful. Rapid tests can be particularly useful for testing women presenting in labor who have not been screened for HIV as part of prenatal care. They also can be used to determine the need for postexposure prophylaxis in the event of a needlestick injury. According to manufacturer’s data, the sensitivity of rapid tests ranges from 99.3% to 100% and specificity from 99.7% to 99.9%.12 However, in real-world experience these numbers have been slightly lower.12 By comparison, the sensitivity and specificity of the fourth-generation EIAs are 99.4% and 99.5%, respectively.14

The downside... A disadvantage of rapid HIV testing is that under current FDA-approval status and CDC guidance, tests performed on oral fluid must have serologic confirmation. In addition, patients tested during the “window period” of seroconversion (after infection occurs but before antibodies are detectable) will test negative with rapid HIV tests and must be reminded that repeat testing should be done within 4 to 6 weeks of their last potential exposure to the virus. In high-prevalence settings such as urban emergency departments (EDs), rapid HIV tests have detected a significant number of new infections.15 However, ED physicians and urgent care providers have been reluctant to perform HIV tests due to the lack of follow-up for most patients treated in these settings.

Over-the-counter (OTC) tests. Approved by the FDA in 2012, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test is the only available OTC test for use at home. Patients can go to the company’s Web site at www.oraquick.com to learn more about HIV and testing, and the company offers 24-hour phone support. It’s not clear how many patients are taking advantage of this home testing option. The test costs approximately $40 and several studies suggest that this price may deter patients from using it.16 In addition, it is not clear how patients who test positive using an OTC test will access medical care or get appropriate medical follow-up.

New testing algorithm eliminates Western blot

Historically, a patient with a reactive (positive) EIA result would undergo the Western blot assay as a confirmatory test. Although the Western blot for HIV is highly specific (99.7%), it tests only for the IgG antibody. This could lead to a false negative test in a patient in whom IgG seroconversion has not yet occurred. Additionally, the time for HIV confirmation with the Western blot often is one week or longer.

Recently, the CDC has made available for public comment a diagnostic algorithm that removes the Western blot as a recommended test (FIGURE 2).17 This algorithm replaces the Western blot with an assay to differentiate HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. Patients for whom this test is negative should undergo additional testing for HIV RNA to determine if HIV-1 is present. Positive HIV RNA would indicate acute or more recent infection. Studies suggest that this new algorithm is better than the existing algorithm at detecting HIV infections, and many reference labs have already adapted it.17,18

Choosing your words carefully when giving patients their results

Patients can be given the results of a rapid HIV test during their visit, but a positive result on a rapid test should be confirmed by serologic testing. When speaking with a patient who tests positive on a rapid test, consider using the phrase “preliminary positive” results. This allows the patient to more easily process the results, knowing that a confirmatory blood draw will be done. State laws vary regarding how patients can receive HIV test results. Most states allow negative serologic test results to be given over the telephone (or electronically). For positive tests, it is preferable to give these results at a face-to-face consultation so that you can ensure the patient will have access to medical care. For more on HIV testing and lab reporting laws by state, see http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/index.html.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Family and Community Medicine, Lancaster General Hospital, 555 N. Duke Street #3555, Lancaster, PA 17602; jtkirchn@lghealth.org

1. amFAR. Thirty years of HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of an epidemic. amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research Web site. Available at: http://www.amfar.org/thirty-years-of-hiv/aids-snapshots-of-anepidemic. Accessed May 9, 2014.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2011. Vol. 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed October 19, 2013.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: At a glance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed May 9, 2014.

4. The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/ AIDS Strategy for the United States. AIDS.gov Web site. Available at: http://aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2013.

5. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17;quiz CE1-CE4.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: HIV testing and diagnosis among adults-- United States, 2001-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1550-1555.

7. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51-60.

8. Brown M. AAFP, USPSTF recommend routine HIV screening but differ on age to begin. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20130429hivscreenrecs.html. Accessed August 17, 2013.

9. Bayer R, Oppenheimer GM. Routine HIV testing, public health, and the USPSTF--an end to the debate. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:881-884

10. Cornett JK, Kirn TJ. Laboratory diagnosis of HIV in adults: a review of current methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:712-718.

11. Baron EJ, Miller MJ, Weinstein MP, et al. A guide to the utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM)(a). Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e22-e121.

12. Delaney KP, Branson BM, Uniyal A, et al. Evaluation of the performance characteristics of 6 rapid HIV antibody tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:257-263.

13. FDA. FDA approves first rapid diagnostic test to detect both HIV-1 antigen and HIV-1/2 antibodies [press release]. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm364480.htm. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; August 8, 2013. Accessed October 26, 2013.

14. Chavez P, Wesolowski L, Patel P, et al. Evaluation of the performance of the Abbott ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo Assay. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:S51-S55.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Rapid HIV testing in emergency departments—three U.S. sites, January 2005-March 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:597-601.

16. Napierala Mavedzenge S, Baggaley R, Corbett EL. A review of self-testing for HIV: research and policy priorities in a new era of HIV prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:126-138.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Detection of acute HIV infection in two evaluations of a new HIV diagnostic testing algorithm - United States, 2011-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:489-494.

18. Nasrullah M, Wesolowski LG, Meyer WA 3rd, et al. Performance of a fourth-generation HIV screening assay and an alternative HIV diagnostic testing algorithm. AIDS. 2013;27:731-737.

› Screen all adolescents and adults ages 15 to 65 years for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A

› Screen younger adolescents and older adults who are at increased risk for HIV infection on an annual basis. A

› Screen all pregnant women for HIV infection, including those who are in labor and who are untested or whose HIV status is unknown. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For the first 15 years of the epidemic, human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDs) was uniformly fatal. Between 1981 and 1996, approximately 362,000 people in the United States succumbed to the disease.1 That began to change in the mid 1990s, though, when highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) came into routine use. From that point forward, HIV became a chronic, manageable disease for most patients; an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States are now living with HIV infection.2

Unfortunately, the number of new infections continues to grow. There are more than 50,000 new infections in the United States each year,2 and an estimated approximately 200,000 people have it but are undiagnosed, leading to further spread of the disease.3 The Office of National AIDS Policy has issued a National HIV/AIDS Strategy that seeks to reduce new infections by 25% in 2015, in part by identifying people with the disease who do not know their HIV status.4

But screening still has not gotten the uptake by clinicians that health officials would like.

Lack of awareness by physicians? Or an unwillingness of patients?

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began recommending routine HIV screening for individuals between the ages of 13 and 64, with patients given the ability to opt out of such testing.5 That same year, the CDC also removed some prior barriers to testing, such as requiring written consent and pretest counseling. But as of 2009, fewer than 50% of US adults had ever been tested for HIV6—possibly the result of physicians being unaware of the guidelines, patients being unwilling to be tested, and/or reimbursement issues.

Conflicting recommendations may have played a role. When the CDC released its 2006 recommendations, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) felt there was insufficient evidence to support routine HIV screening and issued a grade C recommendation. At that time, the USPSTF recommended that only high-risk individuals and pregnant women be tested (A recommendation, meaning there was high certainty that the net benefit was substantial).

However, in April 2013, based on new evidence regarding the clinical and public health benefits of early identification of HIV infection and subsequent treatment, the USPSTF updated its recommendations. The USPSTF now encourages clinicians to screen all adolescents and adults age 15 to 65 years for HIV (A recommendation).7 Shortly thereafter, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) also endorsed routine HIV screening, although the AAFP calls for such screening to begin at age 18.8

Insurance now covers it… A USPSTF A recommendation carries significant health policy implications because the Affordable Care Act requires private and public health insurance plans to cover preventive services recommended by USPSTF.9

Integrating screening into your practice

Serologic tests have come a long way. The first HIV antibody test was an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) that was introduced in 1985 and used mainly to screen the blood supply. This first-generation EIA identified only immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to HIV type 1 (HIV-1). More sensitive and specific second- and third-generation EIAs have since been developed to detect both IgG and IgM antibodies, as well as antibodies to HIV-2. The third-generation assays also can detect antibodies as soon as 3 weeks after infection.

The fourth-generation EIAs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 201010 and are the first step in the CDC’s current HIV diagnostic testing algorithm. These tests can detect HIV-1/HIV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies and also p24 antigen, which is present within 7 days of the appearance of HIV RNA.11 The fourth-generation assay allows for reliable detection within about 2 weeks of infection (FIGURE 1).10

Rapid HIV tests are also an option.12 These tests can detect IgG and IgM antibodies in samples of saliva, whole blood, serum, and plasma. Results of rapid tests usually are available in 20 to 30 minutes and allow physicians to give patients the results while they are still in the office. In 2013 the FDA approved a combination p24 antigen/antibody rapid HIV assay that according to the manufacturer can detect infection earlier than other currently available rapid tests.13

When rapid tests are most useful. Rapid tests can be particularly useful for testing women presenting in labor who have not been screened for HIV as part of prenatal care. They also can be used to determine the need for postexposure prophylaxis in the event of a needlestick injury. According to manufacturer’s data, the sensitivity of rapid tests ranges from 99.3% to 100% and specificity from 99.7% to 99.9%.12 However, in real-world experience these numbers have been slightly lower.12 By comparison, the sensitivity and specificity of the fourth-generation EIAs are 99.4% and 99.5%, respectively.14

The downside... A disadvantage of rapid HIV testing is that under current FDA-approval status and CDC guidance, tests performed on oral fluid must have serologic confirmation. In addition, patients tested during the “window period” of seroconversion (after infection occurs but before antibodies are detectable) will test negative with rapid HIV tests and must be reminded that repeat testing should be done within 4 to 6 weeks of their last potential exposure to the virus. In high-prevalence settings such as urban emergency departments (EDs), rapid HIV tests have detected a significant number of new infections.15 However, ED physicians and urgent care providers have been reluctant to perform HIV tests due to the lack of follow-up for most patients treated in these settings.

Over-the-counter (OTC) tests. Approved by the FDA in 2012, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test is the only available OTC test for use at home. Patients can go to the company’s Web site at www.oraquick.com to learn more about HIV and testing, and the company offers 24-hour phone support. It’s not clear how many patients are taking advantage of this home testing option. The test costs approximately $40 and several studies suggest that this price may deter patients from using it.16 In addition, it is not clear how patients who test positive using an OTC test will access medical care or get appropriate medical follow-up.

New testing algorithm eliminates Western blot

Historically, a patient with a reactive (positive) EIA result would undergo the Western blot assay as a confirmatory test. Although the Western blot for HIV is highly specific (99.7%), it tests only for the IgG antibody. This could lead to a false negative test in a patient in whom IgG seroconversion has not yet occurred. Additionally, the time for HIV confirmation with the Western blot often is one week or longer.

Recently, the CDC has made available for public comment a diagnostic algorithm that removes the Western blot as a recommended test (FIGURE 2).17 This algorithm replaces the Western blot with an assay to differentiate HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. Patients for whom this test is negative should undergo additional testing for HIV RNA to determine if HIV-1 is present. Positive HIV RNA would indicate acute or more recent infection. Studies suggest that this new algorithm is better than the existing algorithm at detecting HIV infections, and many reference labs have already adapted it.17,18

Choosing your words carefully when giving patients their results

Patients can be given the results of a rapid HIV test during their visit, but a positive result on a rapid test should be confirmed by serologic testing. When speaking with a patient who tests positive on a rapid test, consider using the phrase “preliminary positive” results. This allows the patient to more easily process the results, knowing that a confirmatory blood draw will be done. State laws vary regarding how patients can receive HIV test results. Most states allow negative serologic test results to be given over the telephone (or electronically). For positive tests, it is preferable to give these results at a face-to-face consultation so that you can ensure the patient will have access to medical care. For more on HIV testing and lab reporting laws by state, see http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/index.html.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey T. Kirchner, DO, FAAFP, AAHIVS, Family and Community Medicine, Lancaster General Hospital, 555 N. Duke Street #3555, Lancaster, PA 17602; jtkirchn@lghealth.org

› Screen all adolescents and adults ages 15 to 65 years for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A

› Screen younger adolescents and older adults who are at increased risk for HIV infection on an annual basis. A

› Screen all pregnant women for HIV infection, including those who are in labor and who are untested or whose HIV status is unknown. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For the first 15 years of the epidemic, human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDs) was uniformly fatal. Between 1981 and 1996, approximately 362,000 people in the United States succumbed to the disease.1 That began to change in the mid 1990s, though, when highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) came into routine use. From that point forward, HIV became a chronic, manageable disease for most patients; an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States are now living with HIV infection.2

Unfortunately, the number of new infections continues to grow. There are more than 50,000 new infections in the United States each year,2 and an estimated approximately 200,000 people have it but are undiagnosed, leading to further spread of the disease.3 The Office of National AIDS Policy has issued a National HIV/AIDS Strategy that seeks to reduce new infections by 25% in 2015, in part by identifying people with the disease who do not know their HIV status.4

But screening still has not gotten the uptake by clinicians that health officials would like.

Lack of awareness by physicians? Or an unwillingness of patients?

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began recommending routine HIV screening for individuals between the ages of 13 and 64, with patients given the ability to opt out of such testing.5 That same year, the CDC also removed some prior barriers to testing, such as requiring written consent and pretest counseling. But as of 2009, fewer than 50% of US adults had ever been tested for HIV6—possibly the result of physicians being unaware of the guidelines, patients being unwilling to be tested, and/or reimbursement issues.