User login

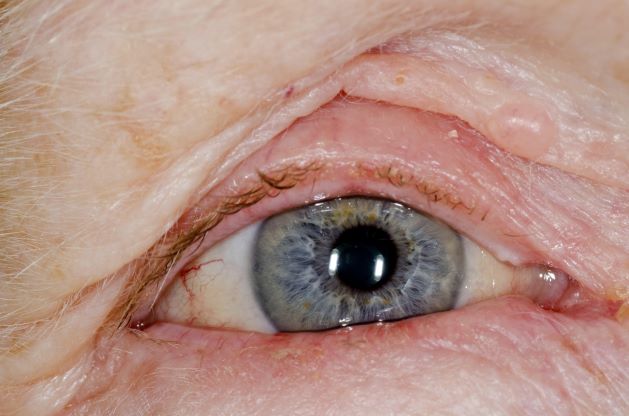

Red swollen eyelids

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammatory disorder of the eyelids that is frequently associated with bacterial colonization of the eyelid. Anatomically, it can be categorized as anterior blepharitis or posterior blepharitis. Anterior blepharitis refers to inflammation primarily positioned around the skin, eyelashes, and lash follicles and is usually further divided into staphylococcal and seborrheic variants. Posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices, meibomian glands, tarsal plate, and blepharo-conjunctival junction.

Blepharitis can be acute or chronic. It is frequently associated with systemic diseases, such as rosacea, atopy, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as ocular diseases, such as dry eye syndromes, chalazion, trichiasis, ectropion and entropion, infectious or other inflammatory conjunctivitis, and keratitis. Moreover, high rates of blepharitis have been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis.

Eye irritation, itching, erythema of the lids, flaking of the lid margins, and/or changes in the eyelashes are common presenting symptoms in patients with blepharitis. Other symptoms may include:

• Burning

• Watering

• Foreign-body sensation

• Crusting and mattering of the lashes and medial canthus

• Red lids

• Red eyes

• Photophobia

• Pain

• Decreased vision

• Visual fluctuations

• Heat, cold, alcohol, and spicy-food intolerance

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes bacterial keratitis, which is a serious ocular disorder that can lead to vision loss if not properly treated. Bacterial keratitis progresses rapidly and can result in corneal destruction within 24-48 hours with some particularly virulent bacteria. Patients with bacterial keratitis typically report rapid onset of pain, photophobia, and decreased vision.

Ocular rosacea should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of blepharitis, and the two conditions can co-occur. Patients with ocular rosacea may experience facial symptoms (eg, recurrent flushing episodes, persistent and/or recurrent midfacial erythema, papular and pustular lesions) in addition to ocular symptoms, which can range from minor irritation, foreign-body sensation, and blurry vision to severe ocular surface disruption and inflammatory keratitis.

Bacterial conjunctivitis involves inflammation of the bulbar and/or palpebral conjunctiva, whereas blepharitis involves inflammation of the eyelids only. Other conditions to consider in the diagnosis of blepharitis can be found here.

Given the unprecedented efficacy seen in clinical trials, dupilumab is emerging as a first-line therapeutic for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. However, clinicians should be alert to ocular complications among their patients with atopic dermatitis who are being treated with dupilumab. In some patients, this may be because of preexisting meibomian gland disease and ocular surface disease. After a diagnosis of ocular complications, the continued use of dupilumab should be jointly evaluated by the ophthalmologist and dermatologist or allergist on the basis of the ocular risk vs systemic benefit. Treatment for blepharitis typically includes strict eyelid hygiene and topical antibiotic ointment; oral antibiotics can be beneficial for refractory disease.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 71-year-old woman was referred for an ophthalmologic examination by her dermatologist. The patient reports recent onset of red, swollen eyelids; ocular itching; and a burning sensation. Prior medical history includes severe atopic dermatitis, type 2 diabetes, and osteoarthritis. Current medications include metformin 1000 mg/d, celecoxib 200 mg/d, and clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream twice daily. The patient began receiving subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg/once every 2 weeks about 6 weeks earlier.

Atopic Dermatitis: Phenotypes

History of AD with progressing flare

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD complicated by bacterial infection. A skin swab culture is positive for Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, xerosis, and lichenification. Individuals of all ages may be affected by AD, although it normally begins in infancy. Studies suggest that as many as 17.1% of adults and 22.6% of children are affected by AD. The disease is associated with diminished quality of life, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety. To further complicate matters, patients with AD have a significantly increased risk for recurrent skin infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

The underlying mechanisms of bacterial infection in AD are multifactorial and involve both host and bacterial factors. Factors implicated in the increased risk for infection in patients with AD include skin barrier defects, suppression of cutaneous innate immunity by type 2 inflammation, S aureus colonization, and cutaneous dysbiosis. Up to 90% of patients with AD are colonized with S aureus. It has been theorized that the host skin microbiota may play a role in protecting against S aureus colonization and infection in patients with AD. Additionally, bacterial virulence factors, such as the superantigens, proteases, and cytolytic phenol‐soluble modulins secreted by S aureus, trigger skin inflammation and may also contribute to bacterial persistence and/or epithelial penetration and infection.

Overt bacterial infection in patients with AD can be recognized by the presence of weeping lesions, honey‐colored crusts, and pustules. However, cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy are seen in both AD exacerbations and in patients with infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging. In addition, anatomical site‐ and skin type-specific features may disguise signs of infection, and the high frequency of S aureus colonization in AD makes positive skin swab culture of suspected infection an unreliable diagnostic tool.

S pyogenes is the second most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in AD (S aureus is the leading cause, although data suggest that pediatric patients are not likely to be affected by superinfections caused by methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA]). S pyogenes may cause infections in patients with AD alone or in combination with S aureus. Patients with these skin infections usually present with pustules or impetigo. The lesions may appear as punched-out erosions with scalloped borders that mimic eczema herpeticum or eczema coxsackium. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology, the presence of purulent exudate and pustules on skin examination may suggest a diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection over inflammation from dermatitis.

The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of noninfected AD is not recommended; however, systemic antibiotics can be recommended for patients with clinical evidence of bacterial infection, in addition to standard treatment for AD, including the concurrent application of topical steroids. For patients with AD who have signs and symptoms of systemic illness, hospitalization and empirical intravenous antibiotics are recommended. The antibiotic regimen should provide coverage against S aureus because this is the most frequently identified bacterial pathogen in AD.

When treating critically ill patients, treatment that provides coverage for both MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) with vancomycin and an antistaphylococcal beta-lactam is appropriate. In patients with severe but non–life-threatening infections, vancomycin may be used alone as empirical therapy, pending culture results. Clindamycin can also be considered, particularly if there is no concern for an endovascular infection and the local incidence of clindamycin resistance is less than 15%.

Bacteremia triggered by S aureus initially requires the use of a bactericidal intravenous agent. For MRSA, vancomycin is the first-line agent. Cefazolin and nafcillin are both acceptable first-line agents for MSSA, although nafcillin can cause venous irritation and phlebitis when administered peripherally. Among children with S aureus bacteremia, an oral agent to which the isolate is susceptible is appropriate, as long as there are no concerns for ongoing bacteremia or endovascular complications. Duration of therapy should be determined by the clinical response; 7-14 days is usually recommended.

For patients with AD with uncomplicated, nonpurulent skin infection, a beta-lactam antibiotic that covers both S aureus and beta-hemolytic streptococci (eg, cefazolin or cephalexin) may be appropriate pending clinical response or culture and considering local epidemiology and resistance patterns. In patients who present with a skin abscess, history of MRSA colonization, close contacts with a history of skin infections, or recent hospitalization, consideration of coverage for MRSA is recommended. Acceptable oral options for MRSA skin infections in both children and adults include clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and linezolid, assuming that the isolate is susceptible in vitro. Finally, topical mupirocin ointment for 5-10 days is an appropriate treatment for patients with AD with minor, localized skin infections such as impetigo.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier

A 9-year-old girl with a history of moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) presents with a rapidly progressing AD flare. The patient had been stable over the past 6 months with the use of daily emollients. Over the past 36-48 hours, the patient developed pruritic lesions and pustules on her knees and elbows, and erythema and scaling around the eyes. Physical examination reveals a temperature of 101.5°F (38.6°C), a heart rate of 112 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, and a blood pressure of 100/95 mm Hg. Physical findings include cutaneous erythema and warmth surrounding the affected areas, pustules with yellow fluid, and regional lymphadenopathy.

Atopic Dermatitis in the ED

Atopic Dermatitis: Clinical Outcomes

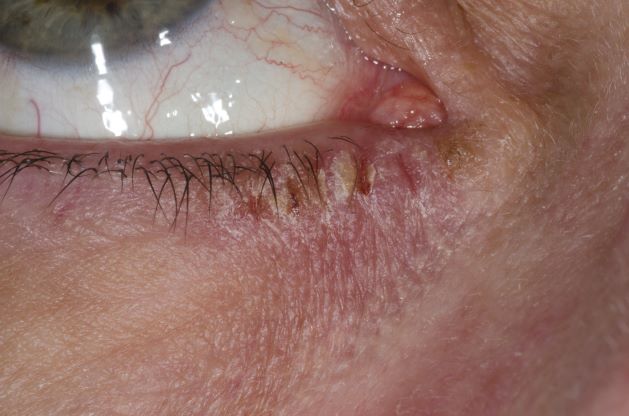

Woman with burning, itchy red eyes

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 21-year-old woman presents with burning, itchy red eyes that she rubs incessantly. On examination, she has an erythematic, scaly, pruritic rash on the upper and lower eyelids and below her eyes. She has no other outbreaks on the rest of her skin except for mild acne. A moisturizer has provided minimal relief for the itching but has not helped with the rash. She has a history of asthma, for which she uses an inhaler, and of hay fever, for which she takes an antihistamine. She also reports that she has had two episodes of conjunctivitis within the past year, which were treated with antibiotic eye drops.