User login

Anticoagulation Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving treatment options for preventing stroke, acute coronary events, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism in at-risk patients. The Anticoagulation Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

VIDEO: New stroke guideline embraces imaging-guided thrombectomy

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

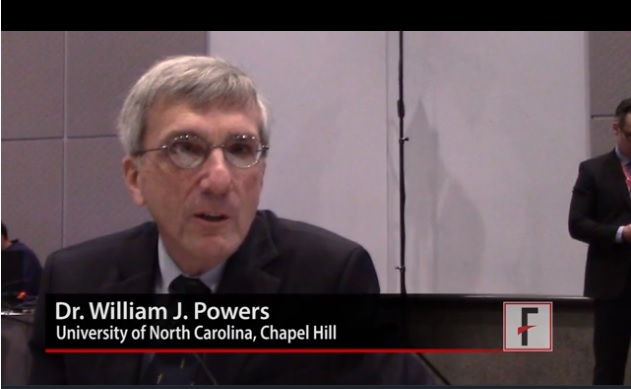

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ISC 2018

DEFUSE 3: Thrombectomy time window broadens

LOS ANGELES – The final results of the DEFUSE 3 trial are in, and the results are unequivocal: Thrombectomy performed 6-16 hours after the stroke patient was last known to be well was associated with dramatically improved outcomes in 90-day death and disability.

It has long been said that time is brain. Time is still vital, but some strokes progress at a slower rate. “We have the opportunity to treat these patients in a time window that we never thought was possible,” Gregory W. Albers, MD, said in presenting the findings at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The subjects included those with proximal middle-cerebral artery or internal-carotid artery occlusion and infarcts of 70 mL or less in size, and a ratio of the volume of ischemic tissue on perfusion imaging to infarct tissue of 1.8 or higher. Both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 used the RAPID software from iSchemaView to assess infarct volume.

The DEFUSE 3 results aren’t a surprise, as the trial was stopped early after an interim analysis showed efficacy. But they are immediately practice changing. “This will perhaps be a once in a lifetime situation where a study gets published and within 2 hours gets incorporated into new guidelines,” said Dr. Albers, lead author of the study, who is the Coyote Foundation Professor, neurology and neurological sciences, and professor, by courtesy, of neurosurgery at the Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Minutes later at the press conference, it was announced that the results of both DEFUSE 3 and DAWN had indeed been included in the guidelines.

The DEFUSE (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) 3 trial included 182 patients from 38 U.S. centers who were recruited during May 2016–May 2017. Of these, 92 were randomized to thrombectomy and standard medical therapy, and 90 to standard medical therapy only.

Patients who underwent thrombectomy were more likely to have a favorable distribution of disability scores on the modified Rankin scale at 90 days (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.77; adjusted OR, 3.36; both P less than .001). “The odds ratio [of 2.77] was the largest ever reported for a thrombectomy study,” Dr. Albers said, and the ISC audience erupted into spontaneous applause. “We couldn’t be happier,” he responded.

Nearly half (45%) of patients in the thrombectomy group scored as functionally independent at 90 days (Rankin score 0-2), compared with 17% in the medical-therapy group (risk ratio, 2.67; P less than .001). Mortality was also lower in the intervention group (14% vs. 26%; P = .05).

The rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (7% thrombectomy, 4% medical therapy only) did not differ significantly between the two groups. Serious complications occurred in 43% of patients in the thrombectomy group, compared with 53% in the medical therapy–only group (P = .018).

A subanalysis showed consistent benefit of thrombectomy, even in patients with a longer elapsed time between stroke onset and randomization, while the patients who received medical therapy had worse outcomes as more time passed. In 50 patients in the under 9-hour group, 40% of those who received thrombectomy were functionally independent at 9 weeks, compared with 28% in the medical therapy–only group. Among 72 patients in the 9- to 12-hour group, 50% were functionally independent (vs. 17%), and in the greater than 12-hour group, 42% (7%).

The study filled up rapidly, at about twice the rate that the researchers anticipated, and that suggests that the procedure could find broad use. “It shows that these patients are not difficult to find,” said Dr. Albers.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Albers has a financial stake in iSchemaView and is on the scientific advisory board for iSchemaView and Medtronic.

The DEFUSE 3 results were published online concurrently with Dr. Albers’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1713973).

SOURCE: Albers G et al. ISC 2018

LOS ANGELES – The final results of the DEFUSE 3 trial are in, and the results are unequivocal: Thrombectomy performed 6-16 hours after the stroke patient was last known to be well was associated with dramatically improved outcomes in 90-day death and disability.

It has long been said that time is brain. Time is still vital, but some strokes progress at a slower rate. “We have the opportunity to treat these patients in a time window that we never thought was possible,” Gregory W. Albers, MD, said in presenting the findings at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The subjects included those with proximal middle-cerebral artery or internal-carotid artery occlusion and infarcts of 70 mL or less in size, and a ratio of the volume of ischemic tissue on perfusion imaging to infarct tissue of 1.8 or higher. Both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 used the RAPID software from iSchemaView to assess infarct volume.

The DEFUSE 3 results aren’t a surprise, as the trial was stopped early after an interim analysis showed efficacy. But they are immediately practice changing. “This will perhaps be a once in a lifetime situation where a study gets published and within 2 hours gets incorporated into new guidelines,” said Dr. Albers, lead author of the study, who is the Coyote Foundation Professor, neurology and neurological sciences, and professor, by courtesy, of neurosurgery at the Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Minutes later at the press conference, it was announced that the results of both DEFUSE 3 and DAWN had indeed been included in the guidelines.

The DEFUSE (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) 3 trial included 182 patients from 38 U.S. centers who were recruited during May 2016–May 2017. Of these, 92 were randomized to thrombectomy and standard medical therapy, and 90 to standard medical therapy only.

Patients who underwent thrombectomy were more likely to have a favorable distribution of disability scores on the modified Rankin scale at 90 days (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.77; adjusted OR, 3.36; both P less than .001). “The odds ratio [of 2.77] was the largest ever reported for a thrombectomy study,” Dr. Albers said, and the ISC audience erupted into spontaneous applause. “We couldn’t be happier,” he responded.

Nearly half (45%) of patients in the thrombectomy group scored as functionally independent at 90 days (Rankin score 0-2), compared with 17% in the medical-therapy group (risk ratio, 2.67; P less than .001). Mortality was also lower in the intervention group (14% vs. 26%; P = .05).

The rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (7% thrombectomy, 4% medical therapy only) did not differ significantly between the two groups. Serious complications occurred in 43% of patients in the thrombectomy group, compared with 53% in the medical therapy–only group (P = .018).

A subanalysis showed consistent benefit of thrombectomy, even in patients with a longer elapsed time between stroke onset and randomization, while the patients who received medical therapy had worse outcomes as more time passed. In 50 patients in the under 9-hour group, 40% of those who received thrombectomy were functionally independent at 9 weeks, compared with 28% in the medical therapy–only group. Among 72 patients in the 9- to 12-hour group, 50% were functionally independent (vs. 17%), and in the greater than 12-hour group, 42% (7%).

The study filled up rapidly, at about twice the rate that the researchers anticipated, and that suggests that the procedure could find broad use. “It shows that these patients are not difficult to find,” said Dr. Albers.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Albers has a financial stake in iSchemaView and is on the scientific advisory board for iSchemaView and Medtronic.

The DEFUSE 3 results were published online concurrently with Dr. Albers’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1713973).

SOURCE: Albers G et al. ISC 2018

LOS ANGELES – The final results of the DEFUSE 3 trial are in, and the results are unequivocal: Thrombectomy performed 6-16 hours after the stroke patient was last known to be well was associated with dramatically improved outcomes in 90-day death and disability.

It has long been said that time is brain. Time is still vital, but some strokes progress at a slower rate. “We have the opportunity to treat these patients in a time window that we never thought was possible,” Gregory W. Albers, MD, said in presenting the findings at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The subjects included those with proximal middle-cerebral artery or internal-carotid artery occlusion and infarcts of 70 mL or less in size, and a ratio of the volume of ischemic tissue on perfusion imaging to infarct tissue of 1.8 or higher. Both DAWN and DEFUSE 3 used the RAPID software from iSchemaView to assess infarct volume.

The DEFUSE 3 results aren’t a surprise, as the trial was stopped early after an interim analysis showed efficacy. But they are immediately practice changing. “This will perhaps be a once in a lifetime situation where a study gets published and within 2 hours gets incorporated into new guidelines,” said Dr. Albers, lead author of the study, who is the Coyote Foundation Professor, neurology and neurological sciences, and professor, by courtesy, of neurosurgery at the Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center. Minutes later at the press conference, it was announced that the results of both DEFUSE 3 and DAWN had indeed been included in the guidelines.

The DEFUSE (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) 3 trial included 182 patients from 38 U.S. centers who were recruited during May 2016–May 2017. Of these, 92 were randomized to thrombectomy and standard medical therapy, and 90 to standard medical therapy only.

Patients who underwent thrombectomy were more likely to have a favorable distribution of disability scores on the modified Rankin scale at 90 days (unadjusted odds ratio, 2.77; adjusted OR, 3.36; both P less than .001). “The odds ratio [of 2.77] was the largest ever reported for a thrombectomy study,” Dr. Albers said, and the ISC audience erupted into spontaneous applause. “We couldn’t be happier,” he responded.

Nearly half (45%) of patients in the thrombectomy group scored as functionally independent at 90 days (Rankin score 0-2), compared with 17% in the medical-therapy group (risk ratio, 2.67; P less than .001). Mortality was also lower in the intervention group (14% vs. 26%; P = .05).

The rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (7% thrombectomy, 4% medical therapy only) did not differ significantly between the two groups. Serious complications occurred in 43% of patients in the thrombectomy group, compared with 53% in the medical therapy–only group (P = .018).

A subanalysis showed consistent benefit of thrombectomy, even in patients with a longer elapsed time between stroke onset and randomization, while the patients who received medical therapy had worse outcomes as more time passed. In 50 patients in the under 9-hour group, 40% of those who received thrombectomy were functionally independent at 9 weeks, compared with 28% in the medical therapy–only group. Among 72 patients in the 9- to 12-hour group, 50% were functionally independent (vs. 17%), and in the greater than 12-hour group, 42% (7%).

The study filled up rapidly, at about twice the rate that the researchers anticipated, and that suggests that the procedure could find broad use. “It shows that these patients are not difficult to find,” said Dr. Albers.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Albers has a financial stake in iSchemaView and is on the scientific advisory board for iSchemaView and Medtronic.

The DEFUSE 3 results were published online concurrently with Dr. Albers’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24; doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1713973).

SOURCE: Albers G et al. ISC 2018

REPORTING FROM ISC 2018

Key clinical point: Stroke patients with clinical imaging mismatch had significantly better 90-day disability outcomes with thrombectomy.

Major finding: The odds ratio of a favorable outcome at 90 days was 2.77.

Data source: DEFUSE 3, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial in 182 stroke patients.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Albers has a financial stake in iSchemaView and is on the scientific advisor board for iSchemaView and Medtronic.

Source: Albers G. et al. ISC 2018

New hematologic, cardiovascular system link may have therapeutic implications

ATLANTA – An intriguing link between the sex steroid hormonal milieu and platelet mitochondria has potential implications for reducing thrombosis risk.

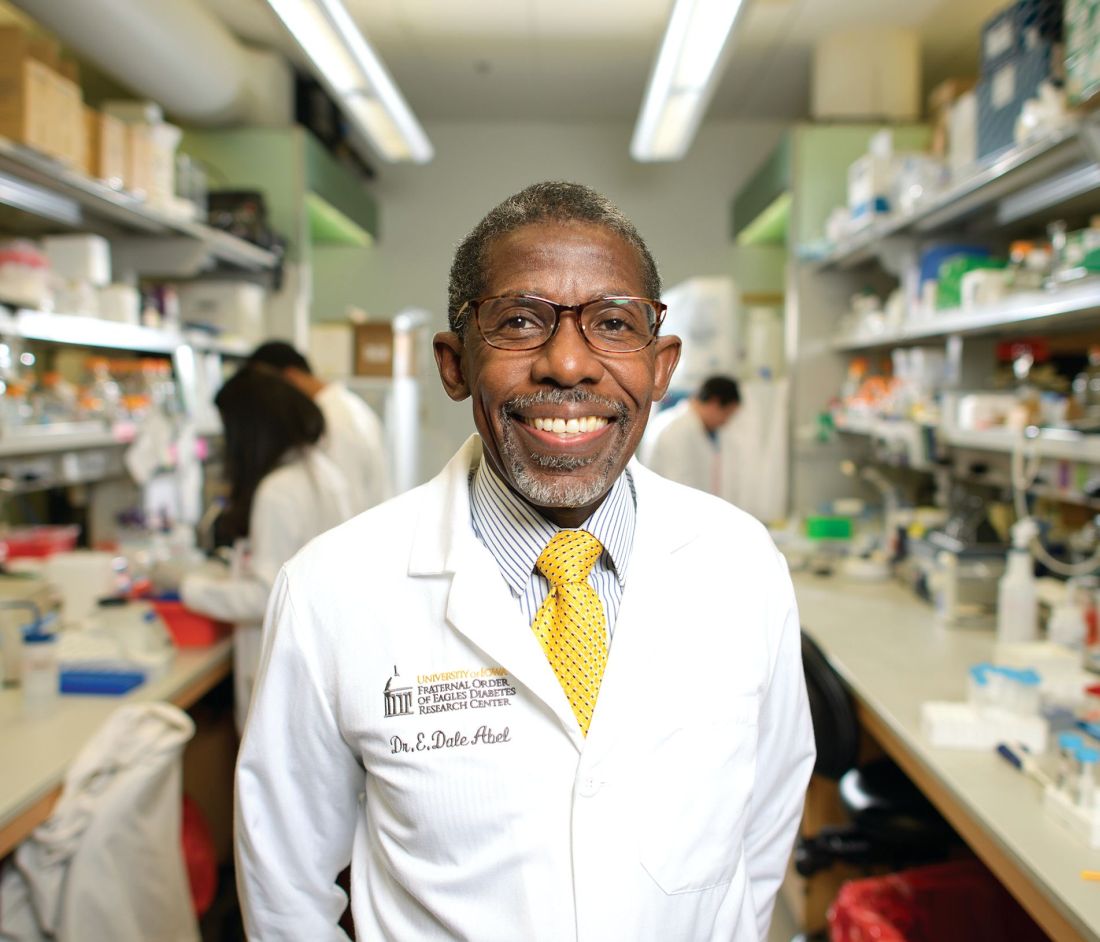

The link, which involves a mitochondrial protein known as optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), appears to play a role in the regulation of thrombosis, and provides a possible explanation for the marked differences in cardiovascular risks between men and women, according to E. Dale Abel, MD, chair of the department of internal medicine, and director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The findings could lead to risk-stratification strategies and the identification of therapeutic targets, Dr. Abel said in an interview.

OPA1 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, he explained.

“My laboratory, for a very long time, has been interested in the cardiovascular complications of diabetes, and a lot of our work has focused on the heart and on the relationship between changes in metabolism and mitochondrial biology in those complications. We got interested in platelets because of a collaboration that actually started with Dr. [Andrew] Weyrich when my lab was at the University of Utah. There was a request for proposals from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for projects that would seek to understand the increased risk of thrombosis that occurs in people with diabetes,” he said.

Specifically, Dr. Weyrich had some preliminary data showing a backup of intermediates of glucose metabolism occurring in the platelets of diabetics.

“This suggested either that there was increased import of glucose into those cells or a decreased ability of those cells to metabolize glucose,” Dr. Abel said, adding that a closer look at the expression of certain genes in platelets as they related to the risk of thrombosis showed that a number of mitochondrial genes were involved, including OPA1.

Since Dr. Abel’s lab was already involved with studying glucose metabolism and mitochondrial metabolism, and had created a number of tools for modifying alleles, which would enable the targeting of expression of some of these genes, he and his colleagues began to look closer at the role of OPA1.

“The relationship between OPA1 and platelet biology, at least based on epidemiological studies from Dr. [Jane] Freedman’s analysis of platelet RNA expression in the Framingham cohort, really seemed to suggest that this had more to do with events in females rather than males,” Dr. Abel said.

He and his colleagues then generated a mouse model in which OPA1 levels in platelets could be manipulated. The goal was to determine if such manipulation would affect platelet function or platelet biology, and also to see if the effects differed between males and females.

“Initially, we didn’t have an expectation that we would see a difference between males and females, but in retrospect, it actually fits very nicely with what the epidemiological data in humans would suggest,” he said, referring to the differences in thrombosis risk between men and women.

Mitochondria go through a process of fusion and fission; OPA1 is involved in the fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane, which has many folds known as cristae.

“These cristae are very important in the ability of mitochondria to generate energy, and OPA1 plays a very important role in maintaining the structure of these cristae,” he explained.

He and his colleagues generated mice that lacked OPA1 specifically in platelets. They then characterized the mitochondria and platelet function in these knockout mice.

“We saw that there was a difference between males and females in terms of how they responded to OPA1 deletion. Specifically, the males appeared to get more overt mitochondrial damage in terms of their structure and function, whereas the mitochondria appeared remarkably normal in females,” he said.

A look at platelet function showed that platelets in males were somewhat hyperactive, while in females they were somewhat underactive.

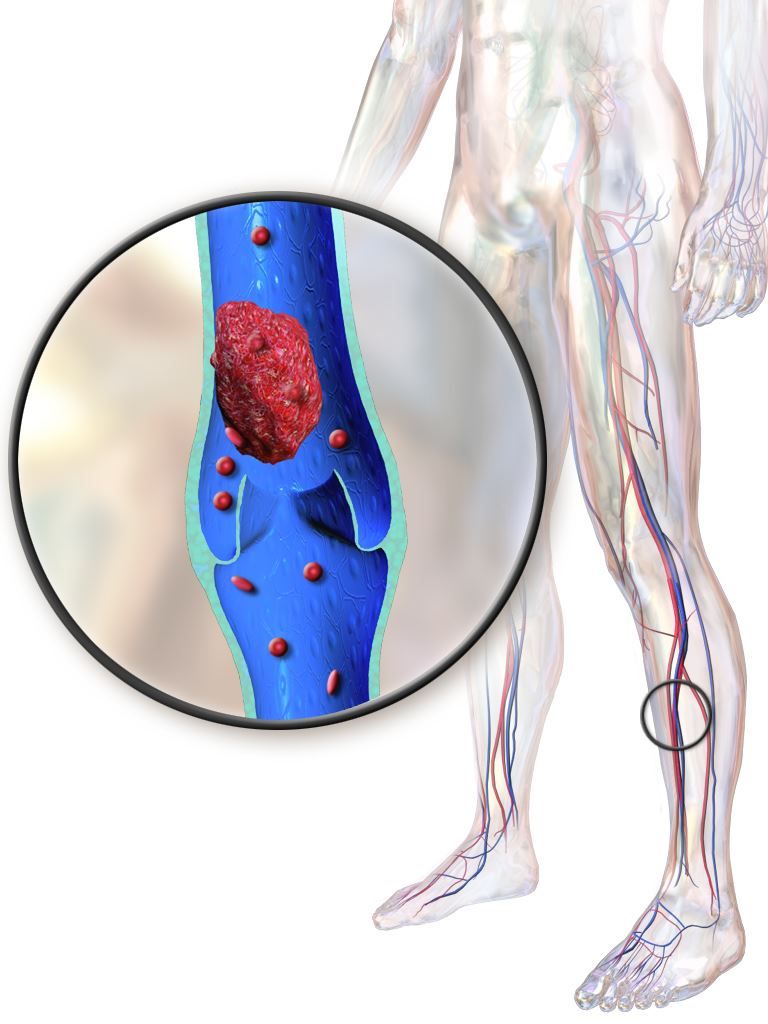

When the researchers used a model of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), more than 90% of male knockout mice developed a DVT versus 50% of wild-type controls. In contrast, there was no increase in DVT in female knockout mice relative to wild-type controls.

“So they were really opposite phenotypes in terms of platelet activity, and whenever one sees a difference between sexes in any biological variable or phenotype, you wonder if this is because of sex hormones,” he said.

This question led to a number of additional experiments.

In one of those experiments, Dr. Abel and his colleagues used a mouse model in which platelets were depleted and replaced via transfusion with platelets from another animal.

“We took male mice that were wild type and we depleted their platelets, and then we took platelets from an OPA1 deficient female and transfused these back into male mice, and took OPA1 deficient platelets from males and transfused them back into platelet-depleted female hosts. The really interesting thing in those experiments was that the phenotype switched,” he said.

That is, platelets in male mice with OPA1 deficiency, which had increased platelet activation in the male mice, became hypoactive when they were transfused into female mice. Similarly, hypoactive platelets from female mice became hyperactive when transfused into platelet-depleted male mice.

“What this told us then, is that the hormonal milieu interacts with OPA1 deficiency to modulate the function of the platelets,” he said.

Additional hormonal manipulations, involving orchiectomy in male mice to lower testosterone levels and increase estrogen levels, and ovariectomy in female mice to lower estrogen levels, showed that this could also modify platelet response.

“So we have discovered that somehow the amount of OPA1 in platelets interacts with circulating estrogens to modify the activity of platelets. This is not a trivial issue, because, as in the epidemiological study, the relationship is something that seems to be particularly true in females, and it also turned out that the OPA1 tended to track with increased cardiovascular events,” he said.

Preliminary studies involving pregnant women, looking at both the first and third trimester (when estrogen levels spike), also showed a correlation between increased platelet activity in the third trimester and higher levels of OPA1 in their platelets.

“It seems there is a relationship between OPA1 and platelets in women and estrogen levels that may then increase the risk of thrombosis. Maybe our mouse model phenotype is explained by the fact that we did the opposite: We reduced OPA1 in the platelets of females, and we actually saw that this was protective,” he said.

The findings are generating excitement, according to Dr. Weyrich, professor of internal medicine and vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was involved in the earlier studies that led Dr. Abel and his team to delve into the OPA1 research.

During a presentation of Dr. Abel’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Weyrich called the work “really, really striking,” and said the gender-specific findings are of particular importance.

“It’s something we often overlook and don’t think about, but I think it’s something that’s probably going to be more and more important as we begin to understand all types of diseases both in benign and malignant hematology,” he said.

Dr. Abel and his team plan to do their part to further that understanding. They are awaiting word on a new National Institutes of Health grant that will allow for expansion of their mouse studies into humans. Specifically, those studies will look at correlations between levels of OPA1 expression in platelets in women and history of/risk for developing a thrombotic event.

“Thrombosis is a significant problem in women who are exposed to estrogens ... and with the exception of a small number of specific genetic disorders of platelets, very little is known about what the risk factors are for this estrogen dependent increase in thrombotic risk,” he said.

What needs to be uncovered, Dr. Abel said, is whether women with the highest levels of OPA1 carry the highest risk of thrombosis.

“If we understand that, we may be in a position to stratify these women based on thrombosis risk in the setting of estrogen exposure. I think the other thing that will come out of the work, as we begin to understand the mechanisms for this relationship, is the identification of targets that we could therapeutically modulate to reduce this risk,” he added.

Eventually, as more is learned about the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between OPA1 and platelet activation, the findings might also lead to new approaches for reducing the risk of thrombosis in men, he noted.

Dr. Abel and Dr. Weyrich reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – An intriguing link between the sex steroid hormonal milieu and platelet mitochondria has potential implications for reducing thrombosis risk.

The link, which involves a mitochondrial protein known as optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), appears to play a role in the regulation of thrombosis, and provides a possible explanation for the marked differences in cardiovascular risks between men and women, according to E. Dale Abel, MD, chair of the department of internal medicine, and director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The findings could lead to risk-stratification strategies and the identification of therapeutic targets, Dr. Abel said in an interview.

OPA1 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, he explained.

“My laboratory, for a very long time, has been interested in the cardiovascular complications of diabetes, and a lot of our work has focused on the heart and on the relationship between changes in metabolism and mitochondrial biology in those complications. We got interested in platelets because of a collaboration that actually started with Dr. [Andrew] Weyrich when my lab was at the University of Utah. There was a request for proposals from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for projects that would seek to understand the increased risk of thrombosis that occurs in people with diabetes,” he said.

Specifically, Dr. Weyrich had some preliminary data showing a backup of intermediates of glucose metabolism occurring in the platelets of diabetics.

“This suggested either that there was increased import of glucose into those cells or a decreased ability of those cells to metabolize glucose,” Dr. Abel said, adding that a closer look at the expression of certain genes in platelets as they related to the risk of thrombosis showed that a number of mitochondrial genes were involved, including OPA1.

Since Dr. Abel’s lab was already involved with studying glucose metabolism and mitochondrial metabolism, and had created a number of tools for modifying alleles, which would enable the targeting of expression of some of these genes, he and his colleagues began to look closer at the role of OPA1.

“The relationship between OPA1 and platelet biology, at least based on epidemiological studies from Dr. [Jane] Freedman’s analysis of platelet RNA expression in the Framingham cohort, really seemed to suggest that this had more to do with events in females rather than males,” Dr. Abel said.

He and his colleagues then generated a mouse model in which OPA1 levels in platelets could be manipulated. The goal was to determine if such manipulation would affect platelet function or platelet biology, and also to see if the effects differed between males and females.

“Initially, we didn’t have an expectation that we would see a difference between males and females, but in retrospect, it actually fits very nicely with what the epidemiological data in humans would suggest,” he said, referring to the differences in thrombosis risk between men and women.

Mitochondria go through a process of fusion and fission; OPA1 is involved in the fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane, which has many folds known as cristae.

“These cristae are very important in the ability of mitochondria to generate energy, and OPA1 plays a very important role in maintaining the structure of these cristae,” he explained.

He and his colleagues generated mice that lacked OPA1 specifically in platelets. They then characterized the mitochondria and platelet function in these knockout mice.

“We saw that there was a difference between males and females in terms of how they responded to OPA1 deletion. Specifically, the males appeared to get more overt mitochondrial damage in terms of their structure and function, whereas the mitochondria appeared remarkably normal in females,” he said.

A look at platelet function showed that platelets in males were somewhat hyperactive, while in females they were somewhat underactive.

When the researchers used a model of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), more than 90% of male knockout mice developed a DVT versus 50% of wild-type controls. In contrast, there was no increase in DVT in female knockout mice relative to wild-type controls.

“So they were really opposite phenotypes in terms of platelet activity, and whenever one sees a difference between sexes in any biological variable or phenotype, you wonder if this is because of sex hormones,” he said.

This question led to a number of additional experiments.

In one of those experiments, Dr. Abel and his colleagues used a mouse model in which platelets were depleted and replaced via transfusion with platelets from another animal.

“We took male mice that were wild type and we depleted their platelets, and then we took platelets from an OPA1 deficient female and transfused these back into male mice, and took OPA1 deficient platelets from males and transfused them back into platelet-depleted female hosts. The really interesting thing in those experiments was that the phenotype switched,” he said.

That is, platelets in male mice with OPA1 deficiency, which had increased platelet activation in the male mice, became hypoactive when they were transfused into female mice. Similarly, hypoactive platelets from female mice became hyperactive when transfused into platelet-depleted male mice.

“What this told us then, is that the hormonal milieu interacts with OPA1 deficiency to modulate the function of the platelets,” he said.

Additional hormonal manipulations, involving orchiectomy in male mice to lower testosterone levels and increase estrogen levels, and ovariectomy in female mice to lower estrogen levels, showed that this could also modify platelet response.

“So we have discovered that somehow the amount of OPA1 in platelets interacts with circulating estrogens to modify the activity of platelets. This is not a trivial issue, because, as in the epidemiological study, the relationship is something that seems to be particularly true in females, and it also turned out that the OPA1 tended to track with increased cardiovascular events,” he said.

Preliminary studies involving pregnant women, looking at both the first and third trimester (when estrogen levels spike), also showed a correlation between increased platelet activity in the third trimester and higher levels of OPA1 in their platelets.

“It seems there is a relationship between OPA1 and platelets in women and estrogen levels that may then increase the risk of thrombosis. Maybe our mouse model phenotype is explained by the fact that we did the opposite: We reduced OPA1 in the platelets of females, and we actually saw that this was protective,” he said.

The findings are generating excitement, according to Dr. Weyrich, professor of internal medicine and vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was involved in the earlier studies that led Dr. Abel and his team to delve into the OPA1 research.

During a presentation of Dr. Abel’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Weyrich called the work “really, really striking,” and said the gender-specific findings are of particular importance.

“It’s something we often overlook and don’t think about, but I think it’s something that’s probably going to be more and more important as we begin to understand all types of diseases both in benign and malignant hematology,” he said.

Dr. Abel and his team plan to do their part to further that understanding. They are awaiting word on a new National Institutes of Health grant that will allow for expansion of their mouse studies into humans. Specifically, those studies will look at correlations between levels of OPA1 expression in platelets in women and history of/risk for developing a thrombotic event.

“Thrombosis is a significant problem in women who are exposed to estrogens ... and with the exception of a small number of specific genetic disorders of platelets, very little is known about what the risk factors are for this estrogen dependent increase in thrombotic risk,” he said.

What needs to be uncovered, Dr. Abel said, is whether women with the highest levels of OPA1 carry the highest risk of thrombosis.

“If we understand that, we may be in a position to stratify these women based on thrombosis risk in the setting of estrogen exposure. I think the other thing that will come out of the work, as we begin to understand the mechanisms for this relationship, is the identification of targets that we could therapeutically modulate to reduce this risk,” he added.

Eventually, as more is learned about the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between OPA1 and platelet activation, the findings might also lead to new approaches for reducing the risk of thrombosis in men, he noted.

Dr. Abel and Dr. Weyrich reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – An intriguing link between the sex steroid hormonal milieu and platelet mitochondria has potential implications for reducing thrombosis risk.

The link, which involves a mitochondrial protein known as optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), appears to play a role in the regulation of thrombosis, and provides a possible explanation for the marked differences in cardiovascular risks between men and women, according to E. Dale Abel, MD, chair of the department of internal medicine, and director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The findings could lead to risk-stratification strategies and the identification of therapeutic targets, Dr. Abel said in an interview.

OPA1 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, he explained.

“My laboratory, for a very long time, has been interested in the cardiovascular complications of diabetes, and a lot of our work has focused on the heart and on the relationship between changes in metabolism and mitochondrial biology in those complications. We got interested in platelets because of a collaboration that actually started with Dr. [Andrew] Weyrich when my lab was at the University of Utah. There was a request for proposals from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for projects that would seek to understand the increased risk of thrombosis that occurs in people with diabetes,” he said.

Specifically, Dr. Weyrich had some preliminary data showing a backup of intermediates of glucose metabolism occurring in the platelets of diabetics.

“This suggested either that there was increased import of glucose into those cells or a decreased ability of those cells to metabolize glucose,” Dr. Abel said, adding that a closer look at the expression of certain genes in platelets as they related to the risk of thrombosis showed that a number of mitochondrial genes were involved, including OPA1.

Since Dr. Abel’s lab was already involved with studying glucose metabolism and mitochondrial metabolism, and had created a number of tools for modifying alleles, which would enable the targeting of expression of some of these genes, he and his colleagues began to look closer at the role of OPA1.

“The relationship between OPA1 and platelet biology, at least based on epidemiological studies from Dr. [Jane] Freedman’s analysis of platelet RNA expression in the Framingham cohort, really seemed to suggest that this had more to do with events in females rather than males,” Dr. Abel said.

He and his colleagues then generated a mouse model in which OPA1 levels in platelets could be manipulated. The goal was to determine if such manipulation would affect platelet function or platelet biology, and also to see if the effects differed between males and females.

“Initially, we didn’t have an expectation that we would see a difference between males and females, but in retrospect, it actually fits very nicely with what the epidemiological data in humans would suggest,” he said, referring to the differences in thrombosis risk between men and women.

Mitochondria go through a process of fusion and fission; OPA1 is involved in the fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane, which has many folds known as cristae.

“These cristae are very important in the ability of mitochondria to generate energy, and OPA1 plays a very important role in maintaining the structure of these cristae,” he explained.

He and his colleagues generated mice that lacked OPA1 specifically in platelets. They then characterized the mitochondria and platelet function in these knockout mice.

“We saw that there was a difference between males and females in terms of how they responded to OPA1 deletion. Specifically, the males appeared to get more overt mitochondrial damage in terms of their structure and function, whereas the mitochondria appeared remarkably normal in females,” he said.

A look at platelet function showed that platelets in males were somewhat hyperactive, while in females they were somewhat underactive.

When the researchers used a model of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), more than 90% of male knockout mice developed a DVT versus 50% of wild-type controls. In contrast, there was no increase in DVT in female knockout mice relative to wild-type controls.

“So they were really opposite phenotypes in terms of platelet activity, and whenever one sees a difference between sexes in any biological variable or phenotype, you wonder if this is because of sex hormones,” he said.

This question led to a number of additional experiments.

In one of those experiments, Dr. Abel and his colleagues used a mouse model in which platelets were depleted and replaced via transfusion with platelets from another animal.

“We took male mice that were wild type and we depleted their platelets, and then we took platelets from an OPA1 deficient female and transfused these back into male mice, and took OPA1 deficient platelets from males and transfused them back into platelet-depleted female hosts. The really interesting thing in those experiments was that the phenotype switched,” he said.

That is, platelets in male mice with OPA1 deficiency, which had increased platelet activation in the male mice, became hypoactive when they were transfused into female mice. Similarly, hypoactive platelets from female mice became hyperactive when transfused into platelet-depleted male mice.

“What this told us then, is that the hormonal milieu interacts with OPA1 deficiency to modulate the function of the platelets,” he said.

Additional hormonal manipulations, involving orchiectomy in male mice to lower testosterone levels and increase estrogen levels, and ovariectomy in female mice to lower estrogen levels, showed that this could also modify platelet response.

“So we have discovered that somehow the amount of OPA1 in platelets interacts with circulating estrogens to modify the activity of platelets. This is not a trivial issue, because, as in the epidemiological study, the relationship is something that seems to be particularly true in females, and it also turned out that the OPA1 tended to track with increased cardiovascular events,” he said.

Preliminary studies involving pregnant women, looking at both the first and third trimester (when estrogen levels spike), also showed a correlation between increased platelet activity in the third trimester and higher levels of OPA1 in their platelets.

“It seems there is a relationship between OPA1 and platelets in women and estrogen levels that may then increase the risk of thrombosis. Maybe our mouse model phenotype is explained by the fact that we did the opposite: We reduced OPA1 in the platelets of females, and we actually saw that this was protective,” he said.

The findings are generating excitement, according to Dr. Weyrich, professor of internal medicine and vice president for research at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, who was involved in the earlier studies that led Dr. Abel and his team to delve into the OPA1 research.

During a presentation of Dr. Abel’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Weyrich called the work “really, really striking,” and said the gender-specific findings are of particular importance.

“It’s something we often overlook and don’t think about, but I think it’s something that’s probably going to be more and more important as we begin to understand all types of diseases both in benign and malignant hematology,” he said.

Dr. Abel and his team plan to do their part to further that understanding. They are awaiting word on a new National Institutes of Health grant that will allow for expansion of their mouse studies into humans. Specifically, those studies will look at correlations between levels of OPA1 expression in platelets in women and history of/risk for developing a thrombotic event.

“Thrombosis is a significant problem in women who are exposed to estrogens ... and with the exception of a small number of specific genetic disorders of platelets, very little is known about what the risk factors are for this estrogen dependent increase in thrombotic risk,” he said.

What needs to be uncovered, Dr. Abel said, is whether women with the highest levels of OPA1 carry the highest risk of thrombosis.

“If we understand that, we may be in a position to stratify these women based on thrombosis risk in the setting of estrogen exposure. I think the other thing that will come out of the work, as we begin to understand the mechanisms for this relationship, is the identification of targets that we could therapeutically modulate to reduce this risk,” he added.

Eventually, as more is learned about the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between OPA1 and platelet activation, the findings might also lead to new approaches for reducing the risk of thrombosis in men, he noted.

Dr. Abel and Dr. Weyrich reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASH 2017

Surgical LAA occlusion tops anticoagulation for AF thromboprotection

Surgical left atrial appendage occlusion may be just as good as anticoagulation at preventing thromboembolic events in older people with atrial fibrillation, with less risk of bleeding into the brain, according to a database review of more than 10,000 patients.

Among elderly atrial fibrillation patients who underwent heart surgery with no oral follow-up oral anticoagulation, those who had the left atrial appendage surgically occluded were 74% less likely than were those who did not to be readmitted for a major thromboembolic event within 3 years, and 68% less likely to be readmitted for a hemorrhagic stroke, researchers at Duke University in Durham, N.C., found.

“The current study demonstrated that S-LAAO [surgical left atrial appendage occlusion] was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism among patients without oral anticoagulation. In the cohort of patients discharged with oral anticoagulation, S-LAAO was not associated with [reduced] thromboembolism but was associated with a lower risk for hemorrhagic stroke presumably related to eventual discontinuation of oral anticoagulation among S-LAAO patients,” reported Daniel Friedman, MD, and his coinvestigators. The study was published Jan. 23 in JAMA.

In short, the findings suggest that shutting down the left atrial appendage in older patients offers the same stroke protection as anticoagulation, but without the bleeding risk. Given the low rates of anticoagulant use, physicians have been considering that approach for a while. Even so, it’s only been a weak (IIb) recommendation so far in AF guidelines because of the lack of evidence.

That might change soon, but “additional randomized studies comparing S-LAAO without anticoagulation [versus] systemic anticoagulation alone will be needed to define the optimal use of S-LAAO,” said Dr. Friedman, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Duke, and his colleagues. Those studies are in the works.

The team found 10,524 older patients in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database during 2011-2012, and linked them to Medicare data so they could be followed for up to 3 years. About a third of the subjects had stand-alone coronary artery bypass grafting; the rest had mitral or aortic valve repairs with or without CABG.

The investigators compared outcomes among the 37% (3,892) who had S-LAAO with outcomes among those who did not. Participants were a median of 76 years of age, 61% were men, and they were all at high risk for AF stroke.

After a mean follow-up of 2.6 years, subjects who received S-LAAO without postoperative anticoagulation had a significantly lower risk of readmission for thromboembolism – stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic embolism – compared with those who received neither S-LAAO nor anticoagulation (unadjusted rate 4.2% versus 6.0%; adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR] 0.26, 95% CI, 0.17-0.40, P less than .001).

There was no extra embolic stroke protection from S-LAAO in patients who were discharged on anticoagulation (sHR 0.88, 95% CI, 0.56-1.39; P = .59), but the risk of returning with a hemorrhagic stroke was considerably less (sHR 0.32, 95% CI, 0.17-0.57, P less than .001).

The S-LAAO group more commonly had nonparoxysmal AF, a higher ejection fraction, a lower mortality risk score, and lower rates of common stroke risks, such as diabetes, hypertension, and prior stroke. The Duke team adjusted for those and a long list of other confounders, including smoking, age, preoperative warfarin, and academic hospital status.

There were important limitations. No one knows what surgeons did to close the LAA, or how well it worked, and most patients discharged on anticoagulation were sent home on warfarin, not the newer direct oral anticoagulants.

The investigators noted that “the strongest data to date for LAAO come from randomized trials comparing warfarin with percutaneous LAAO using the WATCHMAN device” from Boston Scientific.

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality in those trials appeared to be driven by a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke and occurred despite increased rates of ischemic stroke, they said.

The current study, however, showed that S-LAAO was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism in patients without oral anticoagulation, the authors said.

The work was funded, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Friedman reported grants from Boston Scientific and Abbott. Other authors reported financial relations with those and several other companies.

SOURCE: Friedman DJ, et. al. JAMA. 2018;319(4):365-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20125.

The implications of the study may have far-reaching consequences on the best treatment to reduce both thromboembolism and hemorrhage associated with AF treatment.

There is a strong signal that S-LAAO may be equivalent to anticoagulation prophylaxis to avoid thromboembolism in certain patients. This possibility is intriguing because it suggests that S-LAAO may be as effective as anticoagulation and could potentially avoid the bleeding risks associated with anticoagulation. A reasonable hypothesis based on the authors’ findings is that ablation procedures that occlude the left atrial appendage are adequate treatments to avoid thromboembolism and to minimize postoperative anticoagulation-related hemorrhage. This somewhat novel hypothesis, if true, could avoid a significant morbidity associated with anticoagulation while providing adequate treatment for thromboembolic complications of AF.

Importantly, the results suggest that failure to perform an S-LAAO at the time of cardiac operation in patients with nonvalvular AF is associated with significantly increased intermediate-term thromboembolic risk.

Victor M. Ferraris , MD, PhD, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, made his comments in an accompanying editorial. He had no conflicts of interest.

The implications of the study may have far-reaching consequences on the best treatment to reduce both thromboembolism and hemorrhage associated with AF treatment.

There is a strong signal that S-LAAO may be equivalent to anticoagulation prophylaxis to avoid thromboembolism in certain patients. This possibility is intriguing because it suggests that S-LAAO may be as effective as anticoagulation and could potentially avoid the bleeding risks associated with anticoagulation. A reasonable hypothesis based on the authors’ findings is that ablation procedures that occlude the left atrial appendage are adequate treatments to avoid thromboembolism and to minimize postoperative anticoagulation-related hemorrhage. This somewhat novel hypothesis, if true, could avoid a significant morbidity associated with anticoagulation while providing adequate treatment for thromboembolic complications of AF.

Importantly, the results suggest that failure to perform an S-LAAO at the time of cardiac operation in patients with nonvalvular AF is associated with significantly increased intermediate-term thromboembolic risk.

Victor M. Ferraris , MD, PhD, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, made his comments in an accompanying editorial. He had no conflicts of interest.

The implications of the study may have far-reaching consequences on the best treatment to reduce both thromboembolism and hemorrhage associated with AF treatment.

There is a strong signal that S-LAAO may be equivalent to anticoagulation prophylaxis to avoid thromboembolism in certain patients. This possibility is intriguing because it suggests that S-LAAO may be as effective as anticoagulation and could potentially avoid the bleeding risks associated with anticoagulation. A reasonable hypothesis based on the authors’ findings is that ablation procedures that occlude the left atrial appendage are adequate treatments to avoid thromboembolism and to minimize postoperative anticoagulation-related hemorrhage. This somewhat novel hypothesis, if true, could avoid a significant morbidity associated with anticoagulation while providing adequate treatment for thromboembolic complications of AF.

Importantly, the results suggest that failure to perform an S-LAAO at the time of cardiac operation in patients with nonvalvular AF is associated with significantly increased intermediate-term thromboembolic risk.

Victor M. Ferraris , MD, PhD, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, made his comments in an accompanying editorial. He had no conflicts of interest.

Surgical left atrial appendage occlusion may be just as good as anticoagulation at preventing thromboembolic events in older people with atrial fibrillation, with less risk of bleeding into the brain, according to a database review of more than 10,000 patients.

Among elderly atrial fibrillation patients who underwent heart surgery with no oral follow-up oral anticoagulation, those who had the left atrial appendage surgically occluded were 74% less likely than were those who did not to be readmitted for a major thromboembolic event within 3 years, and 68% less likely to be readmitted for a hemorrhagic stroke, researchers at Duke University in Durham, N.C., found.

“The current study demonstrated that S-LAAO [surgical left atrial appendage occlusion] was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism among patients without oral anticoagulation. In the cohort of patients discharged with oral anticoagulation, S-LAAO was not associated with [reduced] thromboembolism but was associated with a lower risk for hemorrhagic stroke presumably related to eventual discontinuation of oral anticoagulation among S-LAAO patients,” reported Daniel Friedman, MD, and his coinvestigators. The study was published Jan. 23 in JAMA.

In short, the findings suggest that shutting down the left atrial appendage in older patients offers the same stroke protection as anticoagulation, but without the bleeding risk. Given the low rates of anticoagulant use, physicians have been considering that approach for a while. Even so, it’s only been a weak (IIb) recommendation so far in AF guidelines because of the lack of evidence.

That might change soon, but “additional randomized studies comparing S-LAAO without anticoagulation [versus] systemic anticoagulation alone will be needed to define the optimal use of S-LAAO,” said Dr. Friedman, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Duke, and his colleagues. Those studies are in the works.

The team found 10,524 older patients in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database during 2011-2012, and linked them to Medicare data so they could be followed for up to 3 years. About a third of the subjects had stand-alone coronary artery bypass grafting; the rest had mitral or aortic valve repairs with or without CABG.

The investigators compared outcomes among the 37% (3,892) who had S-LAAO with outcomes among those who did not. Participants were a median of 76 years of age, 61% were men, and they were all at high risk for AF stroke.

After a mean follow-up of 2.6 years, subjects who received S-LAAO without postoperative anticoagulation had a significantly lower risk of readmission for thromboembolism – stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic embolism – compared with those who received neither S-LAAO nor anticoagulation (unadjusted rate 4.2% versus 6.0%; adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR] 0.26, 95% CI, 0.17-0.40, P less than .001).

There was no extra embolic stroke protection from S-LAAO in patients who were discharged on anticoagulation (sHR 0.88, 95% CI, 0.56-1.39; P = .59), but the risk of returning with a hemorrhagic stroke was considerably less (sHR 0.32, 95% CI, 0.17-0.57, P less than .001).

The S-LAAO group more commonly had nonparoxysmal AF, a higher ejection fraction, a lower mortality risk score, and lower rates of common stroke risks, such as diabetes, hypertension, and prior stroke. The Duke team adjusted for those and a long list of other confounders, including smoking, age, preoperative warfarin, and academic hospital status.

There were important limitations. No one knows what surgeons did to close the LAA, or how well it worked, and most patients discharged on anticoagulation were sent home on warfarin, not the newer direct oral anticoagulants.

The investigators noted that “the strongest data to date for LAAO come from randomized trials comparing warfarin with percutaneous LAAO using the WATCHMAN device” from Boston Scientific.

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality in those trials appeared to be driven by a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke and occurred despite increased rates of ischemic stroke, they said.

The current study, however, showed that S-LAAO was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism in patients without oral anticoagulation, the authors said.

The work was funded, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Friedman reported grants from Boston Scientific and Abbott. Other authors reported financial relations with those and several other companies.

SOURCE: Friedman DJ, et. al. JAMA. 2018;319(4):365-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20125.

Surgical left atrial appendage occlusion may be just as good as anticoagulation at preventing thromboembolic events in older people with atrial fibrillation, with less risk of bleeding into the brain, according to a database review of more than 10,000 patients.

Among elderly atrial fibrillation patients who underwent heart surgery with no oral follow-up oral anticoagulation, those who had the left atrial appendage surgically occluded were 74% less likely than were those who did not to be readmitted for a major thromboembolic event within 3 years, and 68% less likely to be readmitted for a hemorrhagic stroke, researchers at Duke University in Durham, N.C., found.

“The current study demonstrated that S-LAAO [surgical left atrial appendage occlusion] was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism among patients without oral anticoagulation. In the cohort of patients discharged with oral anticoagulation, S-LAAO was not associated with [reduced] thromboembolism but was associated with a lower risk for hemorrhagic stroke presumably related to eventual discontinuation of oral anticoagulation among S-LAAO patients,” reported Daniel Friedman, MD, and his coinvestigators. The study was published Jan. 23 in JAMA.

In short, the findings suggest that shutting down the left atrial appendage in older patients offers the same stroke protection as anticoagulation, but without the bleeding risk. Given the low rates of anticoagulant use, physicians have been considering that approach for a while. Even so, it’s only been a weak (IIb) recommendation so far in AF guidelines because of the lack of evidence.

That might change soon, but “additional randomized studies comparing S-LAAO without anticoagulation [versus] systemic anticoagulation alone will be needed to define the optimal use of S-LAAO,” said Dr. Friedman, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Duke, and his colleagues. Those studies are in the works.

The team found 10,524 older patients in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database during 2011-2012, and linked them to Medicare data so they could be followed for up to 3 years. About a third of the subjects had stand-alone coronary artery bypass grafting; the rest had mitral or aortic valve repairs with or without CABG.

The investigators compared outcomes among the 37% (3,892) who had S-LAAO with outcomes among those who did not. Participants were a median of 76 years of age, 61% were men, and they were all at high risk for AF stroke.

After a mean follow-up of 2.6 years, subjects who received S-LAAO without postoperative anticoagulation had a significantly lower risk of readmission for thromboembolism – stroke, transient ischemic attack, or systemic embolism – compared with those who received neither S-LAAO nor anticoagulation (unadjusted rate 4.2% versus 6.0%; adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio [sHR] 0.26, 95% CI, 0.17-0.40, P less than .001).

There was no extra embolic stroke protection from S-LAAO in patients who were discharged on anticoagulation (sHR 0.88, 95% CI, 0.56-1.39; P = .59), but the risk of returning with a hemorrhagic stroke was considerably less (sHR 0.32, 95% CI, 0.17-0.57, P less than .001).

The S-LAAO group more commonly had nonparoxysmal AF, a higher ejection fraction, a lower mortality risk score, and lower rates of common stroke risks, such as diabetes, hypertension, and prior stroke. The Duke team adjusted for those and a long list of other confounders, including smoking, age, preoperative warfarin, and academic hospital status.

There were important limitations. No one knows what surgeons did to close the LAA, or how well it worked, and most patients discharged on anticoagulation were sent home on warfarin, not the newer direct oral anticoagulants.

The investigators noted that “the strongest data to date for LAAO come from randomized trials comparing warfarin with percutaneous LAAO using the WATCHMAN device” from Boston Scientific.

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality in those trials appeared to be driven by a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke and occurred despite increased rates of ischemic stroke, they said.

The current study, however, showed that S-LAAO was associated with a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism in patients without oral anticoagulation, the authors said.

The work was funded, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Friedman reported grants from Boston Scientific and Abbott. Other authors reported financial relations with those and several other companies.

SOURCE: Friedman DJ, et. al. JAMA. 2018;319(4):365-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20125.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Surgical left atrial appendage occlusion (S-LAAO) is probably just as good as anticoagulation at preventing thromboembolic events in older people with atrial fibrillation, with less risk of bleeding into the brain.

Major finding: within 3 years, and 68% less likely to be readmitted for a hemorrhagic stroke.

Study details: Database review of more than 10,000 elderly AF patients followed for up to 3 years after cardiac surgery.

Disclosures: The work was funded, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration. The authors had financial ties to Boston Scientific, Abbott, and several other companies.

Source: Friedman DJ, et. al. JAMA. 2018;319(4):365-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20125

Thrombosis risk is elevated with myeloproliferative neoplasms

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a higher rate of arterial and venous thrombosis than does the general population, with the greatest risk occurring around the time of diagnosis, according to results of a retrospective study.

Hazard ratios at 3 months after diagnosis were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls, Malin Hultcrantz, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and her coauthors reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Although previous studies have suggested patients with MPNs are at increased risk for thrombotic events, this large, population-based analysis is believed to be the first study to provide estimates of excess risk compared with matched control participants.

“These results are encouraging, and we believe that further refinement of risk scoring systems (such as by including time since MPN diagnosis and biomarkers); rethinking of recommendations for younger patients with MPNs; and emerging, more effective treatments will further improve outcomes for patients with MPNs,” the researchers wrote.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study included 9,429 Swedish patients diagnosed with MPNs between 1987 and 2009 and 35,820 matched control participants. Patient follow-up through 2010 was included in the analysis.

Thrombosis risk was highest near the time of diagnosis but decreased during the following year “likely because of effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN;”still, the risk remained elevated, the researchers wrote.

“This novel finding underlines the importance of initiating phlebotomy as well as thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment, when indicated, as soon as the MPN is diagnosed,” they added.

Arterial thrombosis hazard ratios for MPN patients, compared with control participants, were 3.0 at 3 months after diagnosis, 2.0 at 1 year, and 1.5 at 5 years. Similarly, venous thrombosis hazard ratios were 9.7 at 3 months, 4.7 at 1 year, and 3.2 at 5 years.

Thrombosis risk was elevated in all age groups and all MPN subtypes, including primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Of note, the study confirmed prior thrombosis and older age (60 years or older) as risk factors. Among patients with both of those risk factors, risk of thrombosis was increased 7-fold, according to the researchers.

Hazard ratios for thrombosis decreased during more recent time periods, suggesting a “positive effect” of improved treatment strategies, including increased use of aspirin as primary prophylaxis, better cardiovascular risk management, and better adherence to recommendations for cytoreductive treatment and phlebotomy, the researchers noted. Additionally, treatment with interferon and Janus kinase 2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, “may be effective in further reducing risk for thrombosis,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, the Swedish Research Council, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, among other sources. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hultcrantz M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-0028.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a higher rate of arterial and venous thrombosis than does the general population, with the greatest risk occurring around the time of diagnosis, according to results of a retrospective study.

Hazard ratios at 3 months after diagnosis were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls, Malin Hultcrantz, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and her coauthors reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Although previous studies have suggested patients with MPNs are at increased risk for thrombotic events, this large, population-based analysis is believed to be the first study to provide estimates of excess risk compared with matched control participants.

“These results are encouraging, and we believe that further refinement of risk scoring systems (such as by including time since MPN diagnosis and biomarkers); rethinking of recommendations for younger patients with MPNs; and emerging, more effective treatments will further improve outcomes for patients with MPNs,” the researchers wrote.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study included 9,429 Swedish patients diagnosed with MPNs between 1987 and 2009 and 35,820 matched control participants. Patient follow-up through 2010 was included in the analysis.

Thrombosis risk was highest near the time of diagnosis but decreased during the following year “likely because of effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN;”still, the risk remained elevated, the researchers wrote.

“This novel finding underlines the importance of initiating phlebotomy as well as thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment, when indicated, as soon as the MPN is diagnosed,” they added.

Arterial thrombosis hazard ratios for MPN patients, compared with control participants, were 3.0 at 3 months after diagnosis, 2.0 at 1 year, and 1.5 at 5 years. Similarly, venous thrombosis hazard ratios were 9.7 at 3 months, 4.7 at 1 year, and 3.2 at 5 years.