User login

Anticoagulation Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving treatment options for preventing stroke, acute coronary events, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism in at-risk patients. The Anticoagulation Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

AHA: DAPT score helps decide whether DAPT continues

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

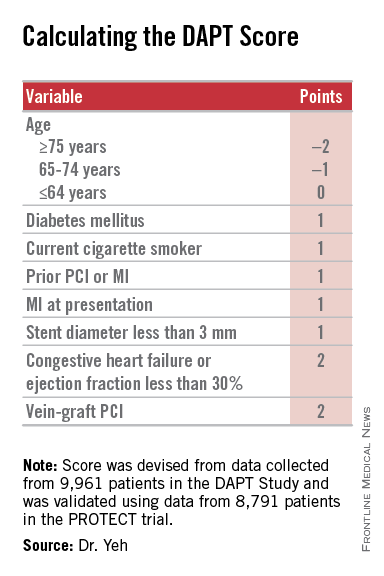

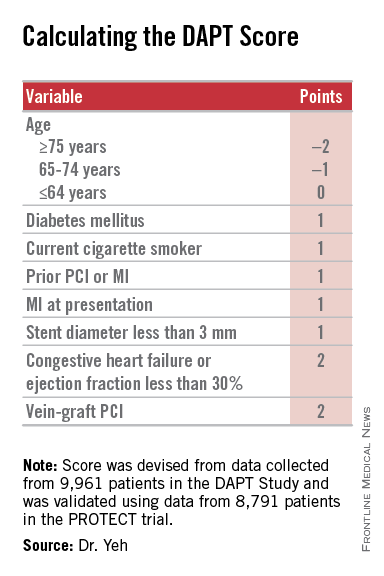

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

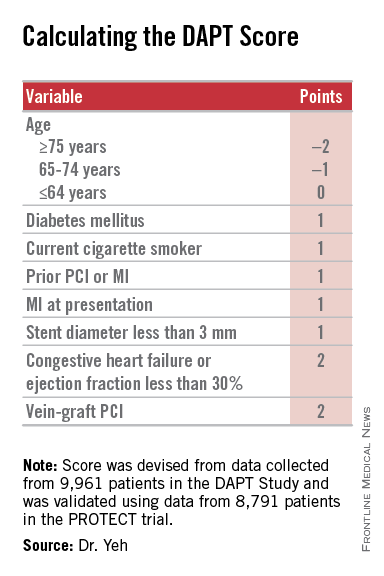

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A year after percutaneous coronary intervention, the DAPT score helps clinicians decide whether to continue dual antiplatelet therapy.

Major finding: DAPT scores of 1 or less were linked with a 2.5-fold higher risk of bleeding than ischemic events prevented by continued DAPT; scores of 2 or more were linked with an eightfold increased rate of ischemic events prevented, compared with bleeding events triggered.

Data source: The DAPT study, a multicenter, international, randomized trial that enrolled 25,682 patients.

Disclosures: The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck.

ACC/AHA guidelines upgrade multivessel PCI, downgrade thrombectomy

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: It’s best to have a cardiac arrest in Midwest

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr. Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non–trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer U.S. inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr. Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care – that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission – were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.

Hospital length of stay greater than 8 days occurred most often in the Northeast. These lengthier stays were 10%-12% less common in the other regions.

The explanation for the marked regional differences observed in this study remains unknown.

“These findings call for more efforts to identify a high-quality model of excellence that standardizes health care delivery and improves quality of care in low-performing regions,” said Dr. Albaeni.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr. Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non–trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer U.S. inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr. Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care – that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission – were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.

Hospital length of stay greater than 8 days occurred most often in the Northeast. These lengthier stays were 10%-12% less common in the other regions.

The explanation for the marked regional differences observed in this study remains unknown.

“These findings call for more efforts to identify a high-quality model of excellence that standardizes health care delivery and improves quality of care in low-performing regions,” said Dr. Albaeni.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr. Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non–trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer U.S. inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr. Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care – that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission – were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.

Hospital length of stay greater than 8 days occurred most often in the Northeast. These lengthier stays were 10%-12% less common in the other regions.

The explanation for the marked regional differences observed in this study remains unknown.

“These findings call for more efforts to identify a high-quality model of excellence that standardizes health care delivery and improves quality of care in low-performing regions,” said Dr. Albaeni.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Substantial and as-yet unexplained regional differences in survival and total hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest exist across the United States.

Major finding: Mortality among adults hospitalized after experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was 14% lower in the Midwest than in the Northeast.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2002-2012 that included 155,592 adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who survived to hospital admission.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Andexanet reverses anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors

Andexanet alfa has been found to reverse the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, according to a study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the Nov. 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 145 healthy individuals with a mean age of 58 years, patients treated first with apixaban and then given a bolus of andexanet had a 94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with a 21% reduction with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 100% of patients within 2-5 minutes.

In the patients treated with rivaroxaban, treatment with andexanet reduced anti-factor Xa activity by 92%, compared with 18% with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 96% of participants in the andexanet group, compared with 7% in the placebo group.

Adverse events associated with andexanet were minor, including constipation, feeling hot, or a strange taste in the mouth, and the effects of the andexanet also were sustained over the course of a 2-hour infusion in addition to the bolus (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510991).

“The rapid onset and offset of action of andexanet and the ability to administer it as a bolus or as a bolus plus an infusion may provide flexibility with regard to the restoration of hemostasis when urgent factor Xa inhibitor reversal is required,” Dr. Deborah M. Siegal of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and coauthors wrote.

The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters.

Factor Xa inhibitors represent an important advance in anticoagulation therapy, but concern over the lack of antidotes has tempered enthusiasm for their use among patients and physicians. Warfarin is perceived as being safer as a result of the availability of effective reversal strategies.

Although additional studies will be needed to optimize the use of andexanet and to determine its true efficacy and safety, it represents a giant step forward in our ability to control anticoagulation therapy.

Dr. Jean M. Connors is with the hematology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513258). Dr. Connors declared personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work.

Factor Xa inhibitors represent an important advance in anticoagulation therapy, but concern over the lack of antidotes has tempered enthusiasm for their use among patients and physicians. Warfarin is perceived as being safer as a result of the availability of effective reversal strategies.

Although additional studies will be needed to optimize the use of andexanet and to determine its true efficacy and safety, it represents a giant step forward in our ability to control anticoagulation therapy.

Dr. Jean M. Connors is with the hematology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513258). Dr. Connors declared personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work.

Factor Xa inhibitors represent an important advance in anticoagulation therapy, but concern over the lack of antidotes has tempered enthusiasm for their use among patients and physicians. Warfarin is perceived as being safer as a result of the availability of effective reversal strategies.

Although additional studies will be needed to optimize the use of andexanet and to determine its true efficacy and safety, it represents a giant step forward in our ability to control anticoagulation therapy.

Dr. Jean M. Connors is with the hematology division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1513258). Dr. Connors declared personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work.

Andexanet alfa has been found to reverse the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, according to a study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the Nov. 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 145 healthy individuals with a mean age of 58 years, patients treated first with apixaban and then given a bolus of andexanet had a 94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with a 21% reduction with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 100% of patients within 2-5 minutes.

In the patients treated with rivaroxaban, treatment with andexanet reduced anti-factor Xa activity by 92%, compared with 18% with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 96% of participants in the andexanet group, compared with 7% in the placebo group.

Adverse events associated with andexanet were minor, including constipation, feeling hot, or a strange taste in the mouth, and the effects of the andexanet also were sustained over the course of a 2-hour infusion in addition to the bolus (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510991).

“The rapid onset and offset of action of andexanet and the ability to administer it as a bolus or as a bolus plus an infusion may provide flexibility with regard to the restoration of hemostasis when urgent factor Xa inhibitor reversal is required,” Dr. Deborah M. Siegal of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and coauthors wrote.

The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters.

Andexanet alfa has been found to reverse the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, according to a study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the Nov. 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 145 healthy individuals with a mean age of 58 years, patients treated first with apixaban and then given a bolus of andexanet had a 94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with a 21% reduction with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 100% of patients within 2-5 minutes.

In the patients treated with rivaroxaban, treatment with andexanet reduced anti-factor Xa activity by 92%, compared with 18% with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 96% of participants in the andexanet group, compared with 7% in the placebo group.

Adverse events associated with andexanet were minor, including constipation, feeling hot, or a strange taste in the mouth, and the effects of the andexanet also were sustained over the course of a 2-hour infusion in addition to the bolus (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510991).

“The rapid onset and offset of action of andexanet and the ability to administer it as a bolus or as a bolus plus an infusion may provide flexibility with regard to the restoration of hemostasis when urgent factor Xa inhibitor reversal is required,” Dr. Deborah M. Siegal of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and coauthors wrote.

The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:Andexanet reverses the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban in healthy older adults.

Major finding: Andexanet achieved a 92%-94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with an 18%-21% reduction with placebo.

Data source: A two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study in 145 healthy individuals.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and a related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters.

Starting ACS patients on varenicline in the hospital boosted smoking quit rates

ORLANDO – Starting varenicline in smokers while hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome resulted in substantially higher smoking abstinence rates than with placebo at all time points through 6 months of follow-up in the double-blind, randomized EVITA trial.

“The ACS population is typically older, they’re long-term smokers, and they come into the hospital with a life-threatening condition. Their family is all around them. They’ve had angioplasty or CABG [coronary artery bypass graft] surgery. So they have pressure on them to stop smoking. This is a teachable moment, a window of opportunity. The public health benefit for smoking cessation in this population is huge. You can cut their risk of death and significant morbidity in half if you can get them to stop,” Dr. Mark J. Eisenberg said in presenting the EVITA results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“To our knowledge, this is the highest-risk population that’s been exposed to varenicline,” said Dr. Eisenberg, professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the cardiovascular health services research program at Jewish General Hospital in Montreal.

The primary study endpoint was continuous self-reported abstinence since baseline backed by biochemical confirmation in the form of an exhaled carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or less at week 24 as well as at all the earlier follow-up visits. The rate was 47.3% in the varenicline group, compared with 32.5% in placebo-treated controls. That placebo response rate is in line with numerous prior studies that have shown that less than one-third of smokers with ACS remain abstinent after leaving the hospital.

“Most cardiologists would say, ‘All my patients stop smoking.’ But in the clinic if you look in the patients’ pockets, you find a pack of cigarettes. They stop smoking while in hospital, but as soon as they’re discharged, the relapse rate is almost immediate. Most patients are smoking the day they get out of hospital,” according to Dr. Eisenberg.

In EVITA, the number-needed-to-treat with varenicline for 12 weeks in order to produce 1 extra nonsmoker at 6 months was 6.8 patients.

The secondary endpoint of at least a 50% reduction in the number of cigarettes per day from baseline to 6 months was met by 67.4% of the varenicline group and 55.6% of controls, with a number-needed-to-treat of 8.5, he continued.

No safety issues emerged in the study, although as Dr. Eisenberg noted, EVITA wasn’t sufficiently powered to look at safety. The only side effect more common in varenicline-treated patients was abnormal dreams, with a 12-week incidence of 15%, threefold higher than in controls, a phenomenon seen in other, larger varenicline studies as well.

The EVITA investigators plan to follow participants out to 12 months. “If we see someone who at 1 year post MI is still smoking, maybe it’s time to go after them again, perhaps with another medication or behavioral therapy,” he said.

There are no randomized clinical trials demonstrating that starting nicotine patches or bupropion in the hospital is effective for smoking cessation in the ACS population, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Eisenberg predicted this study will change clinical practice. In much the same way physicians now routinely start ACS patients on a statin, beta-blocker, and aspirin before they leave the hospital, physicians will capitalize on this opportunity to help ACS patients quit smoking as well, he said.

“The use of varenicline in ACS patients before they leave the hospital is a very important step forward. Cardiologists are increasingly comfortable with the idea of starting secondary prevention medications in the hospital, and there’s very little more important for a person with heart disease who smokes cigarettes than to help them quit smoking. It’s probably the No. 1 priority. So evidence that we can start a medication in the hospital and get more people who smoke cigarettes to quit smoking is definitely game changing, I think,” said Dr. Goff, professor of epidemiology and dean of the Colorado School of Public Health in Aurora.

Dr. Eisenberg reported receiving funding from Pfizer to perform the EVITA trial. He has also gotten honoraria from the company for providing continuing medical education talks on smoking cessation.

ORLANDO – Starting varenicline in smokers while hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome resulted in substantially higher smoking abstinence rates than with placebo at all time points through 6 months of follow-up in the double-blind, randomized EVITA trial.

“The ACS population is typically older, they’re long-term smokers, and they come into the hospital with a life-threatening condition. Their family is all around them. They’ve had angioplasty or CABG [coronary artery bypass graft] surgery. So they have pressure on them to stop smoking. This is a teachable moment, a window of opportunity. The public health benefit for smoking cessation in this population is huge. You can cut their risk of death and significant morbidity in half if you can get them to stop,” Dr. Mark J. Eisenberg said in presenting the EVITA results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“To our knowledge, this is the highest-risk population that’s been exposed to varenicline,” said Dr. Eisenberg, professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the cardiovascular health services research program at Jewish General Hospital in Montreal.

The primary study endpoint was continuous self-reported abstinence since baseline backed by biochemical confirmation in the form of an exhaled carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or less at week 24 as well as at all the earlier follow-up visits. The rate was 47.3% in the varenicline group, compared with 32.5% in placebo-treated controls. That placebo response rate is in line with numerous prior studies that have shown that less than one-third of smokers with ACS remain abstinent after leaving the hospital.

“Most cardiologists would say, ‘All my patients stop smoking.’ But in the clinic if you look in the patients’ pockets, you find a pack of cigarettes. They stop smoking while in hospital, but as soon as they’re discharged, the relapse rate is almost immediate. Most patients are smoking the day they get out of hospital,” according to Dr. Eisenberg.

In EVITA, the number-needed-to-treat with varenicline for 12 weeks in order to produce 1 extra nonsmoker at 6 months was 6.8 patients.

The secondary endpoint of at least a 50% reduction in the number of cigarettes per day from baseline to 6 months was met by 67.4% of the varenicline group and 55.6% of controls, with a number-needed-to-treat of 8.5, he continued.

No safety issues emerged in the study, although as Dr. Eisenberg noted, EVITA wasn’t sufficiently powered to look at safety. The only side effect more common in varenicline-treated patients was abnormal dreams, with a 12-week incidence of 15%, threefold higher than in controls, a phenomenon seen in other, larger varenicline studies as well.

The EVITA investigators plan to follow participants out to 12 months. “If we see someone who at 1 year post MI is still smoking, maybe it’s time to go after them again, perhaps with another medication or behavioral therapy,” he said.

There are no randomized clinical trials demonstrating that starting nicotine patches or bupropion in the hospital is effective for smoking cessation in the ACS population, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Eisenberg predicted this study will change clinical practice. In much the same way physicians now routinely start ACS patients on a statin, beta-blocker, and aspirin before they leave the hospital, physicians will capitalize on this opportunity to help ACS patients quit smoking as well, he said.

“The use of varenicline in ACS patients before they leave the hospital is a very important step forward. Cardiologists are increasingly comfortable with the idea of starting secondary prevention medications in the hospital, and there’s very little more important for a person with heart disease who smokes cigarettes than to help them quit smoking. It’s probably the No. 1 priority. So evidence that we can start a medication in the hospital and get more people who smoke cigarettes to quit smoking is definitely game changing, I think,” said Dr. Goff, professor of epidemiology and dean of the Colorado School of Public Health in Aurora.

Dr. Eisenberg reported receiving funding from Pfizer to perform the EVITA trial. He has also gotten honoraria from the company for providing continuing medical education talks on smoking cessation.

ORLANDO – Starting varenicline in smokers while hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome resulted in substantially higher smoking abstinence rates than with placebo at all time points through 6 months of follow-up in the double-blind, randomized EVITA trial.

“The ACS population is typically older, they’re long-term smokers, and they come into the hospital with a life-threatening condition. Their family is all around them. They’ve had angioplasty or CABG [coronary artery bypass graft] surgery. So they have pressure on them to stop smoking. This is a teachable moment, a window of opportunity. The public health benefit for smoking cessation in this population is huge. You can cut their risk of death and significant morbidity in half if you can get them to stop,” Dr. Mark J. Eisenberg said in presenting the EVITA results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“To our knowledge, this is the highest-risk population that’s been exposed to varenicline,” said Dr. Eisenberg, professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the cardiovascular health services research program at Jewish General Hospital in Montreal.

The primary study endpoint was continuous self-reported abstinence since baseline backed by biochemical confirmation in the form of an exhaled carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or less at week 24 as well as at all the earlier follow-up visits. The rate was 47.3% in the varenicline group, compared with 32.5% in placebo-treated controls. That placebo response rate is in line with numerous prior studies that have shown that less than one-third of smokers with ACS remain abstinent after leaving the hospital.

“Most cardiologists would say, ‘All my patients stop smoking.’ But in the clinic if you look in the patients’ pockets, you find a pack of cigarettes. They stop smoking while in hospital, but as soon as they’re discharged, the relapse rate is almost immediate. Most patients are smoking the day they get out of hospital,” according to Dr. Eisenberg.

In EVITA, the number-needed-to-treat with varenicline for 12 weeks in order to produce 1 extra nonsmoker at 6 months was 6.8 patients.

The secondary endpoint of at least a 50% reduction in the number of cigarettes per day from baseline to 6 months was met by 67.4% of the varenicline group and 55.6% of controls, with a number-needed-to-treat of 8.5, he continued.

No safety issues emerged in the study, although as Dr. Eisenberg noted, EVITA wasn’t sufficiently powered to look at safety. The only side effect more common in varenicline-treated patients was abnormal dreams, with a 12-week incidence of 15%, threefold higher than in controls, a phenomenon seen in other, larger varenicline studies as well.

The EVITA investigators plan to follow participants out to 12 months. “If we see someone who at 1 year post MI is still smoking, maybe it’s time to go after them again, perhaps with another medication or behavioral therapy,” he said.

There are no randomized clinical trials demonstrating that starting nicotine patches or bupropion in the hospital is effective for smoking cessation in the ACS population, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Eisenberg predicted this study will change clinical practice. In much the same way physicians now routinely start ACS patients on a statin, beta-blocker, and aspirin before they leave the hospital, physicians will capitalize on this opportunity to help ACS patients quit smoking as well, he said.

“The use of varenicline in ACS patients before they leave the hospital is a very important step forward. Cardiologists are increasingly comfortable with the idea of starting secondary prevention medications in the hospital, and there’s very little more important for a person with heart disease who smokes cigarettes than to help them quit smoking. It’s probably the No. 1 priority. So evidence that we can start a medication in the hospital and get more people who smoke cigarettes to quit smoking is definitely game changing, I think,” said Dr. Goff, professor of epidemiology and dean of the Colorado School of Public Health in Aurora.

Dr. Eisenberg reported receiving funding from Pfizer to perform the EVITA trial. He has also gotten honoraria from the company for providing continuing medical education talks on smoking cessation.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The number of smokers who need to be started on varenicline while hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome in order to produce one extra nonsmoker at 6 months is 6.8.

Data source: EVITA, a double-blind, randomized multicenter trial in 302 smokers hospitalized for ACS who were prospectively followed for 6 months.

Disclosures: The EVITA study was funded by Pfizer. The presenter reported receiving a grant from the company to conduct the trial, as well as honoraria for giving continuing medical education talks on smoking cessation.

Empagliflozin benefited type 2 diabetes patients with CKD

SAN DIEGO – Empagliflozin used in conjunction with standard of care significantly improved renal outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes, results from a large randomized trial showed.

“These benefits were consistent among patients with and without chronic kidney disease at baseline,” Dr. Christoph Wanner said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

Previous studies have demonstrated that in patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin, an inhibitor of the sodium glucose cotransporter 2 in the kidney, leads to significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c, weight loss, and reductions in blood pressure without increases in heart rate. Developed by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the drug was approved in 2014 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults. At the meeting Dr. Wanner presented new finding results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, which was published in September 2015. That study found that patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events who received empagliflozin, compared with placebo, had a lower rate of the primary composite cardiovascular outcome and death from any cause when the study drug was added to standard care.

For the current analysis, the researchers evaluated renal outcomes in the study participants, which consisted of new-onset or worsening nephropathy, including new onset of macroalbuminuria (defined as a urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) of greater than 300 mg/g); doubling of serum creatinine accompanied by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 45 mL/min/1.73m2 or less; initiation of renal replacement therapy; or death due to renal disease. There was also a composite outcome of doubling of serum creatinine, initiation of renal replacement therapy, or death due to renal disease.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial included 2,333 patients in the placebo group and 4,687 in the empagliflozin group who were followed for a median observation time of 3.1 years. The mean age of the study participants was 63 years and 71% were male. Compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the empagliflozin group demonstrated a 39% reduction in new-onset or worsening of nephropathy (hazard ratio, 0.61; P less than .0001). The reduction “started very early,” said Dr. Wanner, who is professor of medicine and head of nephrology at University Hospital of Wurzburg, Germany. “After 3 months you see the curves [between the placebo and treatment groups] separating.”

The impact on empagliflozin on the composite outcome of doubling of serum creatinine, initiation of renal replacement therapy, or death due to renal disease was even more profound. Compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the empagliflozin demonstrated a 46% reduced risk in the composite outcome (HR, 0.54; P = .0002).

Dr. Wanner went on to present cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Among those with an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 at baseline, the primary outcome of three-point major adverse cardiac events occurred in 176 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (15%), compared with 99 of 607 patients in the placebo group (16%; HR, 0.88). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, the primary outcome of three-point major adverse cardiac events occurred in 314 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (9%), compared with 183 of 1,726 (11%) patients in the placebo group (HR, 0.84). At the same time, the outcome of cardiovascular death occurred in 75 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (6%), compared with 48 of 607 patients in the placebo group (8%; HR, 0.78). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, cardiovascular death occurred in 97 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (3%), compared with 89 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (5%; HR, 0.53). However, there was no detectable benefit for the study medication in reducing the myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with CKD.

Among those with an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 51 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (4%), compared with 43 of 607 patients in the placebo group (7%; HR, 0.59). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 75 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (2%), compared with 52 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (3%; HR, 0.70). At the same time, all-cause mortality occurred in 115 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (9%), compared with 72 of 607 patients in the placebo group (12%; HR, 0.80). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 154 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (4%), compared with 122 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (7%; HR, 0.62).

The most common adverse events in patients with CKD related to the study drug were urinary tract infections and genital infections, but there were no detectable signals on acute kidney failure, hyperkalemia, or bone fracture.

“Empagliflozin reduces cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality, and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Wanner concluded. “Safety and tolerability of empagliflozin in patients with CKD at baseline were similar to the overall trial population and consistent with previous clinical trials.”

The study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly. Dr. Wanner disclosed numerous financial ties to industry.

SAN DIEGO – Empagliflozin used in conjunction with standard of care significantly improved renal outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes, results from a large randomized trial showed.

“These benefits were consistent among patients with and without chronic kidney disease at baseline,” Dr. Christoph Wanner said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

Previous studies have demonstrated that in patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin, an inhibitor of the sodium glucose cotransporter 2 in the kidney, leads to significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c, weight loss, and reductions in blood pressure without increases in heart rate. Developed by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the drug was approved in 2014 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults. At the meeting Dr. Wanner presented new finding results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, which was published in September 2015. That study found that patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events who received empagliflozin, compared with placebo, had a lower rate of the primary composite cardiovascular outcome and death from any cause when the study drug was added to standard care.

For the current analysis, the researchers evaluated renal outcomes in the study participants, which consisted of new-onset or worsening nephropathy, including new onset of macroalbuminuria (defined as a urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) of greater than 300 mg/g); doubling of serum creatinine accompanied by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 45 mL/min/1.73m2 or less; initiation of renal replacement therapy; or death due to renal disease. There was also a composite outcome of doubling of serum creatinine, initiation of renal replacement therapy, or death due to renal disease.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial included 2,333 patients in the placebo group and 4,687 in the empagliflozin group who were followed for a median observation time of 3.1 years. The mean age of the study participants was 63 years and 71% were male. Compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the empagliflozin group demonstrated a 39% reduction in new-onset or worsening of nephropathy (hazard ratio, 0.61; P less than .0001). The reduction “started very early,” said Dr. Wanner, who is professor of medicine and head of nephrology at University Hospital of Wurzburg, Germany. “After 3 months you see the curves [between the placebo and treatment groups] separating.”

The impact on empagliflozin on the composite outcome of doubling of serum creatinine, initiation of renal replacement therapy, or death due to renal disease was even more profound. Compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the empagliflozin demonstrated a 46% reduced risk in the composite outcome (HR, 0.54; P = .0002).

Dr. Wanner went on to present cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Among those with an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 at baseline, the primary outcome of three-point major adverse cardiac events occurred in 176 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (15%), compared with 99 of 607 patients in the placebo group (16%; HR, 0.88). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, the primary outcome of three-point major adverse cardiac events occurred in 314 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (9%), compared with 183 of 1,726 (11%) patients in the placebo group (HR, 0.84). At the same time, the outcome of cardiovascular death occurred in 75 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (6%), compared with 48 of 607 patients in the placebo group (8%; HR, 0.78). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, cardiovascular death occurred in 97 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (3%), compared with 89 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (5%; HR, 0.53). However, there was no detectable benefit for the study medication in reducing the myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with CKD.

Among those with an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 51 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (4%), compared with 43 of 607 patients in the placebo group (7%; HR, 0.59). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 75 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (2%), compared with 52 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (3%; HR, 0.70). At the same time, all-cause mortality occurred in 115 of 1,212 patients in the empagliflozin group (9%), compared with 72 of 607 patients in the placebo group (12%; HR, 0.80). Among those with an eGFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or greater at baseline, hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 154 of 3,473 patients in the empagliflozin group (4%), compared with 122 of 1,726 patients in the placebo group (7%; HR, 0.62).

The most common adverse events in patients with CKD related to the study drug were urinary tract infections and genital infections, but there were no detectable signals on acute kidney failure, hyperkalemia, or bone fracture.