User login

Heat Exposure Tied to Acute Immune Changes

In this study, blood work from volunteers was examined for immune biomarkers, and the findings mapped against environmental data.

“With rising global temperatures, the association between heat exposure and a temporarily weakened response from the immune system is a concern because temperature and humidity are known to be important environmental drivers of infectious, airborne disease transmission,” lead author Daniel W. Riggs, PhD, with the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky, said in a news release.

“In this study, even exposure to relatively modest increases in temperature were associated with acute changes in immune system functioning indexed by low-grade inflammation known to be linked to cardiovascular disorders, as well as potential secondary effects on the ability to optimally protect against infection,” said Rosalind J. Wright, MD, MPH, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Further elucidation of the effects of both acute and more prolonged heat exposures (heat waves) on immune signaling will be important given potential broad health implications beyond the heart,” said Dr. Wright, dean of public health and professor and chair, Department of Public Health, Mount Sinai Health System.

The study was presented at the American Heart Association (AHA) Epidemiology and Prevention | Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Scientific Sessions 2024.

High Temps Hard on Multiple Organs

Extreme-heat events have been shown to increase mortality, and excessive deaths due to heat waves are overwhelmingly cardiovascular in origin. Many prior studies only considered ambient temperature, which fails to capture the actual heat stress experienced by individuals, Dr. Riggs and colleagues wrote.

They designed their study to gauge how short-term heat exposures are related to markers of inflammation and the immune response.

They recruited 624 adults (mean age 49 years, 59% women) from a neighborhood in Louisville during the summer months, when median temperatures over 24 hours were 24.5 °C (76 °F).

They obtained blood samples to measure circulating cytokines and immune cells during clinic visits. Heat metrics, collected on the same day as blood draws, included 24-hour averages of temperature, net effective temperature, and the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), a metric that incorporates temperature, humidity, wind speed, and ultraviolet radiation, to determine the physiological comfort of the human body under specific weather conditions.

The results were adjusted for multiple factors, including sex, age, race, education, body mass index, smoking status, anti-inflammatory medication use, and daily air pollution (PM 2.5).

In adjusted analyses, for every five-degree increase in UTCI, there was an increase in levels of several inflammatory markers, including monocytes (4.2%), eosinophils (9.5%), natural killer T cells (9.9%), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (7.0%) and a decrease in infection-fighting B cells (−6.8%).

Study Raises Important Questions

“We’re finding that heat is associated with health effects across a wide range of organ systems and outcomes, but this study helps start to get at the ‘how,’” said Perry E. Sheffield, MD, MPH, with the Departments of Pediatrics and Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Sheffield said the study raises “important questions like, Does the timing of heat exposure matter (going in and out of air-conditioned spaces for example)? and Could some people be more vulnerable than others based on things like what they eat, whether they exercise, or their genetics?”

The study comes on the heels of a report released earlier this month from the World Meteorological Organization noting that climate change indicators reached record levels in 2023.

“The most critical challenges facing medicine are occurring at the intersection of climate and health, underscoring the urgent need to understand how climate-related factors, such as exposure to more extreme temperatures, shift key regulatory systems in our bodies to contribute to disease,” Dr. Wright told this news organization.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Dr. Riggs, Dr. Wright, and Sheffield had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In this study, blood work from volunteers was examined for immune biomarkers, and the findings mapped against environmental data.

“With rising global temperatures, the association between heat exposure and a temporarily weakened response from the immune system is a concern because temperature and humidity are known to be important environmental drivers of infectious, airborne disease transmission,” lead author Daniel W. Riggs, PhD, with the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky, said in a news release.

“In this study, even exposure to relatively modest increases in temperature were associated with acute changes in immune system functioning indexed by low-grade inflammation known to be linked to cardiovascular disorders, as well as potential secondary effects on the ability to optimally protect against infection,” said Rosalind J. Wright, MD, MPH, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Further elucidation of the effects of both acute and more prolonged heat exposures (heat waves) on immune signaling will be important given potential broad health implications beyond the heart,” said Dr. Wright, dean of public health and professor and chair, Department of Public Health, Mount Sinai Health System.

The study was presented at the American Heart Association (AHA) Epidemiology and Prevention | Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Scientific Sessions 2024.

High Temps Hard on Multiple Organs

Extreme-heat events have been shown to increase mortality, and excessive deaths due to heat waves are overwhelmingly cardiovascular in origin. Many prior studies only considered ambient temperature, which fails to capture the actual heat stress experienced by individuals, Dr. Riggs and colleagues wrote.

They designed their study to gauge how short-term heat exposures are related to markers of inflammation and the immune response.

They recruited 624 adults (mean age 49 years, 59% women) from a neighborhood in Louisville during the summer months, when median temperatures over 24 hours were 24.5 °C (76 °F).

They obtained blood samples to measure circulating cytokines and immune cells during clinic visits. Heat metrics, collected on the same day as blood draws, included 24-hour averages of temperature, net effective temperature, and the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), a metric that incorporates temperature, humidity, wind speed, and ultraviolet radiation, to determine the physiological comfort of the human body under specific weather conditions.

The results were adjusted for multiple factors, including sex, age, race, education, body mass index, smoking status, anti-inflammatory medication use, and daily air pollution (PM 2.5).

In adjusted analyses, for every five-degree increase in UTCI, there was an increase in levels of several inflammatory markers, including monocytes (4.2%), eosinophils (9.5%), natural killer T cells (9.9%), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (7.0%) and a decrease in infection-fighting B cells (−6.8%).

Study Raises Important Questions

“We’re finding that heat is associated with health effects across a wide range of organ systems and outcomes, but this study helps start to get at the ‘how,’” said Perry E. Sheffield, MD, MPH, with the Departments of Pediatrics and Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Sheffield said the study raises “important questions like, Does the timing of heat exposure matter (going in and out of air-conditioned spaces for example)? and Could some people be more vulnerable than others based on things like what they eat, whether they exercise, or their genetics?”

The study comes on the heels of a report released earlier this month from the World Meteorological Organization noting that climate change indicators reached record levels in 2023.

“The most critical challenges facing medicine are occurring at the intersection of climate and health, underscoring the urgent need to understand how climate-related factors, such as exposure to more extreme temperatures, shift key regulatory systems in our bodies to contribute to disease,” Dr. Wright told this news organization.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Dr. Riggs, Dr. Wright, and Sheffield had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In this study, blood work from volunteers was examined for immune biomarkers, and the findings mapped against environmental data.

“With rising global temperatures, the association between heat exposure and a temporarily weakened response from the immune system is a concern because temperature and humidity are known to be important environmental drivers of infectious, airborne disease transmission,” lead author Daniel W. Riggs, PhD, with the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky, said in a news release.

“In this study, even exposure to relatively modest increases in temperature were associated with acute changes in immune system functioning indexed by low-grade inflammation known to be linked to cardiovascular disorders, as well as potential secondary effects on the ability to optimally protect against infection,” said Rosalind J. Wright, MD, MPH, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Further elucidation of the effects of both acute and more prolonged heat exposures (heat waves) on immune signaling will be important given potential broad health implications beyond the heart,” said Dr. Wright, dean of public health and professor and chair, Department of Public Health, Mount Sinai Health System.

The study was presented at the American Heart Association (AHA) Epidemiology and Prevention | Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Scientific Sessions 2024.

High Temps Hard on Multiple Organs

Extreme-heat events have been shown to increase mortality, and excessive deaths due to heat waves are overwhelmingly cardiovascular in origin. Many prior studies only considered ambient temperature, which fails to capture the actual heat stress experienced by individuals, Dr. Riggs and colleagues wrote.

They designed their study to gauge how short-term heat exposures are related to markers of inflammation and the immune response.

They recruited 624 adults (mean age 49 years, 59% women) from a neighborhood in Louisville during the summer months, when median temperatures over 24 hours were 24.5 °C (76 °F).

They obtained blood samples to measure circulating cytokines and immune cells during clinic visits. Heat metrics, collected on the same day as blood draws, included 24-hour averages of temperature, net effective temperature, and the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), a metric that incorporates temperature, humidity, wind speed, and ultraviolet radiation, to determine the physiological comfort of the human body under specific weather conditions.

The results were adjusted for multiple factors, including sex, age, race, education, body mass index, smoking status, anti-inflammatory medication use, and daily air pollution (PM 2.5).

In adjusted analyses, for every five-degree increase in UTCI, there was an increase in levels of several inflammatory markers, including monocytes (4.2%), eosinophils (9.5%), natural killer T cells (9.9%), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (7.0%) and a decrease in infection-fighting B cells (−6.8%).

Study Raises Important Questions

“We’re finding that heat is associated with health effects across a wide range of organ systems and outcomes, but this study helps start to get at the ‘how,’” said Perry E. Sheffield, MD, MPH, with the Departments of Pediatrics and Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Sheffield said the study raises “important questions like, Does the timing of heat exposure matter (going in and out of air-conditioned spaces for example)? and Could some people be more vulnerable than others based on things like what they eat, whether they exercise, or their genetics?”

The study comes on the heels of a report released earlier this month from the World Meteorological Organization noting that climate change indicators reached record levels in 2023.

“The most critical challenges facing medicine are occurring at the intersection of climate and health, underscoring the urgent need to understand how climate-related factors, such as exposure to more extreme temperatures, shift key regulatory systems in our bodies to contribute to disease,” Dr. Wright told this news organization.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Dr. Riggs, Dr. Wright, and Sheffield had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Systematic Viral Testing in Emergency Departments Has Limited Benefit for General Population

Routine use of rapid respiratory virus testing in the emergency department (ED) appears to show limited benefit among patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection (ARI), according to a new study.

Rapid viral testing wasn’t associated with reduced antibiotic use, ED length of stay, or rates of ED return visits or hospitalization. However, testing was associated with a small increase in antiviral prescriptions and a small reduction in blood tests and chest x-rays.

“Our interest in studying the benefits of rapid viral testing in emergency departments comes from a commitment to diagnostic stewardship — ensuring that the right tests are administered to the right patients at the right time while also curbing overuse,” said lead author Tilmann Schober, MD, a resident in pediatric infectious disease at McGill University and Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“Following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we have seen a surge in the availability of rapid viral testing, including molecular multiplex panels,” he said. “However, the actual impact of these advancements on patient care in the ED remains uncertain.”

The study was published online on March 4, 2024, in JAMA Internal Medicine).

Rapid Viral Testing

Dr. Schober and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized clinical trials to understand whether rapid testing for respiratory viruses was associated with patient treatment in the ED.

In particular, the research team looked at whether testing in patients with suspected ARI was associated with decreased antibiotic use, ancillary tests, ED length of stay, ED return visits, hospitalization, and increased influenza antiviral treatment.

Among the trials, seven studies included molecular testing, and eight used multiplex panels, including influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza/RSV/adenovirus/parainfluenza, or a panel of 15 or more respiratory viruses. No study evaluated testing for SARS-CoV-2. The research team reported risk ratios (RRs) and risk difference estimates.

In general, routine rapid viral testing was associated with higher use of influenza antivirals (RR, 1.33) and lower use of chest radiography (RR, 0.88) and blood tests (RR, 0.81). However, the magnitude of these effects was small. For instance, to achieve one additional viral prescription, 70 patients would need to be tested, and to save one x-ray, 30 patients would need to be tested.

“This suggests that, while statistically significant, the practical impact of these secondary outcomes may not justify the extensive effort and resources involved in widespread testing,” Dr. Schober said.

In addition, there was no association between rapid testing and antibiotic use (RR, 0.99), urine testing (RR, 0.95), ED length of stay (0 h), return visits (RR, 0.93), or hospitalization (RR, 1.01).

Notably, there was no association between rapid viral testing and antibiotic use in any prespecified subgroup based on age, test method, publication date, number of viral targets, risk of bias, or industry funding, the authors said. They concluded that rapid virus testing should be reserved for patients for whom the testing will change treatment, such as high-risk patients or those with severe disease.

“It’s crucial to note that our study specifically evaluated the impact of systematic testing of patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection. Our findings do not advocate against rapid respiratory virus testing in general,” Dr. Schober said. “There is well-established evidence supporting the benefits of viral testing in certain contexts, such as hospitalized patients, to guide infection control practices or in specific high-risk populations.”

Future Research

Additional studies should look at testing among subgroups, particularly those with high-risk conditions, the study authors wrote. In addition, the research team would like to study the implementation of novel diagnostic stewardship programs as compared with well-established antibiotic stewardship programs.

“Acute respiratory tract illnesses represent one of the most common reasons for being evaluated in an acute care setting, especially in pediatrics, and these visits have traditionally resulted in excessive antibiotic prescribing, despite the etiology of the infection mostly being viral,” said Suchitra Rao, MBBS, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

Dr. Rao, who wasn’t involved with this study, has surveyed ED providers about respiratory viral testing and changes in clinical decision-making. She and colleagues found that providers most commonly changed clinical decision-making while prescribing an antiviral if influenza was detected or withholding antivirals if influenza wasn’t detected.

“Multiplex testing for respiratory viruses and atypical bacteria is becoming more widespread, with newer-generation platforms having shorter turnaround times, and offers the potential to impact point-of-care decision-making,” she said. “However, these tests are expensive, and more studies are needed to explore whether respiratory pathogen panel testing in the acute care setting has an impact in terms of reduced antibiotic use as well as other outcomes, including ED visits, health-seeking behaviors, and hospitalization.”

For instance, more recent studies around SARS-CoV-2 with newer-generation panels may make a difference, as well as multiplex panels that include numerous viral targets, she said.

“Further RCTs are required to evaluate the impact of influenza/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 panels, as well as respiratory pathogen panel testing in conjunction with antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship efforts, which have been associated with improved outcomes for other rapid molecular platforms, such as blood culture identification panels,” Rao said.

The study was funded by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center. Dr. Schober reported no disclosures, and several study authors reported grants or personal fees from companies outside of this research. Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Routine use of rapid respiratory virus testing in the emergency department (ED) appears to show limited benefit among patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection (ARI), according to a new study.

Rapid viral testing wasn’t associated with reduced antibiotic use, ED length of stay, or rates of ED return visits or hospitalization. However, testing was associated with a small increase in antiviral prescriptions and a small reduction in blood tests and chest x-rays.

“Our interest in studying the benefits of rapid viral testing in emergency departments comes from a commitment to diagnostic stewardship — ensuring that the right tests are administered to the right patients at the right time while also curbing overuse,” said lead author Tilmann Schober, MD, a resident in pediatric infectious disease at McGill University and Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“Following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we have seen a surge in the availability of rapid viral testing, including molecular multiplex panels,” he said. “However, the actual impact of these advancements on patient care in the ED remains uncertain.”

The study was published online on March 4, 2024, in JAMA Internal Medicine).

Rapid Viral Testing

Dr. Schober and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized clinical trials to understand whether rapid testing for respiratory viruses was associated with patient treatment in the ED.

In particular, the research team looked at whether testing in patients with suspected ARI was associated with decreased antibiotic use, ancillary tests, ED length of stay, ED return visits, hospitalization, and increased influenza antiviral treatment.

Among the trials, seven studies included molecular testing, and eight used multiplex panels, including influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza/RSV/adenovirus/parainfluenza, or a panel of 15 or more respiratory viruses. No study evaluated testing for SARS-CoV-2. The research team reported risk ratios (RRs) and risk difference estimates.

In general, routine rapid viral testing was associated with higher use of influenza antivirals (RR, 1.33) and lower use of chest radiography (RR, 0.88) and blood tests (RR, 0.81). However, the magnitude of these effects was small. For instance, to achieve one additional viral prescription, 70 patients would need to be tested, and to save one x-ray, 30 patients would need to be tested.

“This suggests that, while statistically significant, the practical impact of these secondary outcomes may not justify the extensive effort and resources involved in widespread testing,” Dr. Schober said.

In addition, there was no association between rapid testing and antibiotic use (RR, 0.99), urine testing (RR, 0.95), ED length of stay (0 h), return visits (RR, 0.93), or hospitalization (RR, 1.01).

Notably, there was no association between rapid viral testing and antibiotic use in any prespecified subgroup based on age, test method, publication date, number of viral targets, risk of bias, or industry funding, the authors said. They concluded that rapid virus testing should be reserved for patients for whom the testing will change treatment, such as high-risk patients or those with severe disease.

“It’s crucial to note that our study specifically evaluated the impact of systematic testing of patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection. Our findings do not advocate against rapid respiratory virus testing in general,” Dr. Schober said. “There is well-established evidence supporting the benefits of viral testing in certain contexts, such as hospitalized patients, to guide infection control practices or in specific high-risk populations.”

Future Research

Additional studies should look at testing among subgroups, particularly those with high-risk conditions, the study authors wrote. In addition, the research team would like to study the implementation of novel diagnostic stewardship programs as compared with well-established antibiotic stewardship programs.

“Acute respiratory tract illnesses represent one of the most common reasons for being evaluated in an acute care setting, especially in pediatrics, and these visits have traditionally resulted in excessive antibiotic prescribing, despite the etiology of the infection mostly being viral,” said Suchitra Rao, MBBS, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

Dr. Rao, who wasn’t involved with this study, has surveyed ED providers about respiratory viral testing and changes in clinical decision-making. She and colleagues found that providers most commonly changed clinical decision-making while prescribing an antiviral if influenza was detected or withholding antivirals if influenza wasn’t detected.

“Multiplex testing for respiratory viruses and atypical bacteria is becoming more widespread, with newer-generation platforms having shorter turnaround times, and offers the potential to impact point-of-care decision-making,” she said. “However, these tests are expensive, and more studies are needed to explore whether respiratory pathogen panel testing in the acute care setting has an impact in terms of reduced antibiotic use as well as other outcomes, including ED visits, health-seeking behaviors, and hospitalization.”

For instance, more recent studies around SARS-CoV-2 with newer-generation panels may make a difference, as well as multiplex panels that include numerous viral targets, she said.

“Further RCTs are required to evaluate the impact of influenza/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 panels, as well as respiratory pathogen panel testing in conjunction with antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship efforts, which have been associated with improved outcomes for other rapid molecular platforms, such as blood culture identification panels,” Rao said.

The study was funded by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center. Dr. Schober reported no disclosures, and several study authors reported grants or personal fees from companies outside of this research. Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Routine use of rapid respiratory virus testing in the emergency department (ED) appears to show limited benefit among patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection (ARI), according to a new study.

Rapid viral testing wasn’t associated with reduced antibiotic use, ED length of stay, or rates of ED return visits or hospitalization. However, testing was associated with a small increase in antiviral prescriptions and a small reduction in blood tests and chest x-rays.

“Our interest in studying the benefits of rapid viral testing in emergency departments comes from a commitment to diagnostic stewardship — ensuring that the right tests are administered to the right patients at the right time while also curbing overuse,” said lead author Tilmann Schober, MD, a resident in pediatric infectious disease at McGill University and Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“Following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we have seen a surge in the availability of rapid viral testing, including molecular multiplex panels,” he said. “However, the actual impact of these advancements on patient care in the ED remains uncertain.”

The study was published online on March 4, 2024, in JAMA Internal Medicine).

Rapid Viral Testing

Dr. Schober and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized clinical trials to understand whether rapid testing for respiratory viruses was associated with patient treatment in the ED.

In particular, the research team looked at whether testing in patients with suspected ARI was associated with decreased antibiotic use, ancillary tests, ED length of stay, ED return visits, hospitalization, and increased influenza antiviral treatment.

Among the trials, seven studies included molecular testing, and eight used multiplex panels, including influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza/RSV/adenovirus/parainfluenza, or a panel of 15 or more respiratory viruses. No study evaluated testing for SARS-CoV-2. The research team reported risk ratios (RRs) and risk difference estimates.

In general, routine rapid viral testing was associated with higher use of influenza antivirals (RR, 1.33) and lower use of chest radiography (RR, 0.88) and blood tests (RR, 0.81). However, the magnitude of these effects was small. For instance, to achieve one additional viral prescription, 70 patients would need to be tested, and to save one x-ray, 30 patients would need to be tested.

“This suggests that, while statistically significant, the practical impact of these secondary outcomes may not justify the extensive effort and resources involved in widespread testing,” Dr. Schober said.

In addition, there was no association between rapid testing and antibiotic use (RR, 0.99), urine testing (RR, 0.95), ED length of stay (0 h), return visits (RR, 0.93), or hospitalization (RR, 1.01).

Notably, there was no association between rapid viral testing and antibiotic use in any prespecified subgroup based on age, test method, publication date, number of viral targets, risk of bias, or industry funding, the authors said. They concluded that rapid virus testing should be reserved for patients for whom the testing will change treatment, such as high-risk patients or those with severe disease.

“It’s crucial to note that our study specifically evaluated the impact of systematic testing of patients with signs and symptoms of acute respiratory infection. Our findings do not advocate against rapid respiratory virus testing in general,” Dr. Schober said. “There is well-established evidence supporting the benefits of viral testing in certain contexts, such as hospitalized patients, to guide infection control practices or in specific high-risk populations.”

Future Research

Additional studies should look at testing among subgroups, particularly those with high-risk conditions, the study authors wrote. In addition, the research team would like to study the implementation of novel diagnostic stewardship programs as compared with well-established antibiotic stewardship programs.

“Acute respiratory tract illnesses represent one of the most common reasons for being evaluated in an acute care setting, especially in pediatrics, and these visits have traditionally resulted in excessive antibiotic prescribing, despite the etiology of the infection mostly being viral,” said Suchitra Rao, MBBS, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

Dr. Rao, who wasn’t involved with this study, has surveyed ED providers about respiratory viral testing and changes in clinical decision-making. She and colleagues found that providers most commonly changed clinical decision-making while prescribing an antiviral if influenza was detected or withholding antivirals if influenza wasn’t detected.

“Multiplex testing for respiratory viruses and atypical bacteria is becoming more widespread, with newer-generation platforms having shorter turnaround times, and offers the potential to impact point-of-care decision-making,” she said. “However, these tests are expensive, and more studies are needed to explore whether respiratory pathogen panel testing in the acute care setting has an impact in terms of reduced antibiotic use as well as other outcomes, including ED visits, health-seeking behaviors, and hospitalization.”

For instance, more recent studies around SARS-CoV-2 with newer-generation panels may make a difference, as well as multiplex panels that include numerous viral targets, she said.

“Further RCTs are required to evaluate the impact of influenza/RSV/SARS-CoV-2 panels, as well as respiratory pathogen panel testing in conjunction with antimicrobial and diagnostic stewardship efforts, which have been associated with improved outcomes for other rapid molecular platforms, such as blood culture identification panels,” Rao said.

The study was funded by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center. Dr. Schober reported no disclosures, and several study authors reported grants or personal fees from companies outside of this research. Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

New Infant RSV Antibody Treatment Shows Strong Results

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The new RSV antibody treatment for babies has been highly effective in its first season, according to a first look at data from four children’s hospitals.

Babies who received the new preventive treatment for RSV shortly after birth were 90% less likely to be severely sickened with the potentially deadly respiratory illness, according to the new estimate published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is the first real-world evaluation of Beyfortus (the generic name is nirsevimab), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last July.

RSV is a seasonal illness that affects more people — particularly infants and the elderly — in the fall and winter. Symptoms are usually mild in healthy adults, but infants are particularly at risk of getting bronchiolitis, which results in exhausting wheezing and coughing in babies due to swelling in their airways and lungs. Babies who are hospitalized may need fluids and medical devices to help them breathe.

RSV peaked this season from November to January, with more than 10,000 monthly diagnoses reported to the CDC.

The new CDC analysis was conducted among about 700 babies hospitalized for severe respiratory problems from October to the end of February. Among the babies in the study, 407 were diagnosed with RSV and 292 tested negative. The researchers found that 1% of babies in the study who were diagnosed with RSV had received Beyfortus, while the remaining babies who were positive for the virus had not.

Among the babies hospitalized for other severe respiratory problems, 18% had received Beyfortus. Overall, just 59 babies among the nearly 700 in the study received Beyfortus, perhaps reflecting the short supply of the medicine the first season it was available. The report authors noted that babies in the study who did receive Beyfortus also tended to have high-risk medical conditions.

The number of babies nationwide who received Beyfortus during this first season of availability is unclear, but a January CDC survey showed that 4 in 10 parents said their babies under 8 months old had received the treatment. The Wall Street Journal reported recently that a shortage last fall resulted from underestimated demand and from production plans that were set before the CDC decided to recommend that all infants under 8 months old receive Beyfortus if their mothers did not get a maternal vaccine that can protect infants from RSV.

Both the antibody treatment for infants and the maternal vaccine were shown in clinical trials to be about 80% effective at preventing severe illness stemming from RSV.

The authors of the latest CDC report concluded that “this early estimate supports the current nirsevimab recommendation for the prevention of severe RSV disease in infants. Infants should be protected by maternal RSV vaccination or infant receipt of nirsevimab.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Risk for Preterm Birth Stops Maternal RSV Vaccine Trial

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A phase 3 trial of a maternal vaccine candidate for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been stopped early because the risk for preterm births is higher in the candidate vaccine group than in the placebo group.

By the time enrollment was stopped on February 25, 2022 because of the safety signal of preterm birth, 5328 pregnant women had been vaccinated, about half of the intended 10,000 enrollees. Of these, 3557 received the candidate vaccine RSV prefusion F protein–based maternal vaccine, and another 1771 received a placebo.

Data from the trial, sponsored by GSK, were immediately made available when recruitment and vaccination were stopped, and investigation of the preterm birth risk followed. Results of that analysis, led by Ilse Dieussaert, IR, vice president for vaccine development at GSK in Wavre, Belgium, are published online on March 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“We have discontinued our work on this RSV maternal candidate vaccine, and we are closing out all ongoing trials with the exception of the MAT-015 follow-on study to monitor subsequent pregnancies,” a GSK spokesperson said in an interview.

The trial was conducted in pregnant women aged 18-49 years to assess the efficacy and safety of the vaccine. The women were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive the candidate vaccine or placebo between 24 and 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm Births

The primary outcomes were any or severe medically assessed RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection in infants from birth to 6 months and safety in infants from birth to 12 months.

According to the data, preterm birth occurred in 6.8% of the infants in the vaccine group and in 4.9% of those in the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08-1.74; P = .01). Neonatal death occurred in 0.4% in the vaccine group and 0.2% in the placebo group (RR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.62-7.56; P = .23).

To date, only one RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) has been approved for use during pregnancy to protect infants from RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.

“It was a very big deal that this trial was stopped, and the new candidate won’t get approval.” said Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and chief of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York.

Only One RSV Vaccine Approved in Pregnancy

Dr. Glatt pointed out the GSK vaccine is like the maternal vaccine that did get approved. “The data clearly show that there was a slight but increased risk in preterm labor,” Dr. Glatt said, “and while not as clearly shown, there was an increase in neonatal death in the group of very small numbers, but any neonatal death is of concern.”

The implications were disturbing, he added, “You’re giving this vaccine to prevent neonatal death.” Though the Pfizer vaccine that was granted approval had a very slight increase in premature birth, the risk wasn’t statistically significant, he pointed out, “and it showed similar benefits in preventing neonatal illness, which can be fatal.”

Dr. Glatt said that there is still a lingering concern with the approved vaccine, and he explained that most clinicians will give it closer to the end of the recommended time window of 34 weeks. “This way, even if there is a slight increase in premature term labor, you’re probably not going to have a serious outcome because the baby will be far enough along.”

A difference in the incidence of preterm birth between the experimental vaccine and placebo groups was predominantly found in low- and middle-income countries, according to Dieussaert’s team, “where approximately 50% of the trial population was enrolled and where the medical need for maternal RSV vaccines is the greatest.”

The RR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10) for low- and middle-income countries and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.68-1.58) for high-income countries.

“If a smaller percentage of participants from low- and middle-income countries had been enrolled in our trial, the RR for preterm birth in the vaccine group as compared with the placebo group might have been reduced in the overall trial population,” they reported.

The authors explained that the data do not reveal the cause of the higher risk for preterm birth in the vaccine group.

“We do not know what caused the signal,” the company’s spokesperson added. “GSK completed all the necessary steps of product development including preclinical toxicology studies and clinical studies in nonpregnant women prior to starting the studies in pregnant women. There were no safety signals identified in any of the earlier parts of the clinical testing. There have been no safety signals identified in the other phase 3 trials for this vaccine candidate.”

Researchers did not find a correlation between preterm births in the treatment vs control groups with gestational age at the time of vaccination or with particular vaccine clinical trial material lots, race, ethnicity, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, or time between study vaccination and delivery, the GSK spokesperson said.

The spokesperson noted that the halted vaccine is different from GSK’s currently approved adjuvanted RSV vaccine (Arexvy) for adults aged 60 years or older.

What’s Next for Other Vaccines

Maternal vaccines have been effective in preventing other diseases in infants, such as tetanus, influenza, and pertussis, but RSV is a very hard virus to make a vaccine for, Dr. Glatt shared.

The need is great to have more than one option for a maternal RSV vaccine, he added, to address any potential supply concerns.

“People have to realize how serious RSV can be in infants,” he said. “It can be a fatal disease. This can be a serious illness even in healthy children.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Postinfectious Cough: Are Treatments Ever Warranted?

Lingering postinfectious cough has been a concern across Canada this winter. , according to an overview published on February 12 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal

“It’s something a lot of patients are worried about: That lingering cough after a common cold or flu,” lead author Kevin Liang, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, told this news organization. He added that some studies show that as much as a quarter of adult patients have this complaint.

Dr. Liang and his colleagues emphasized that the diagnosis of postinfectious cough is one of exclusion. It relies on the absence of concerning physical examination findings and other “subacute cough mimics” such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

“Pertussis should be considered in patients with a paroxysmal cough, post-tussive vomiting, and inspiratory whoop,” they added. Coughs that persist beyond 8 weeks warrant further workup such as a pulmonary function test to rule out asthma or COPD. Coughs accompanied by hemoptysis, systemic symptoms, dysphagia, excessive dyspnea, or hoarseness also warrant further workup, they added. And patients with a history of smoking or recurrent pneumonia should be followed more closely.

In the absence of red flags, Dr. Liang and coauthors advised that there is no evidence supporting pharmacologic treatment, “which is associated with harms,” such as medication adverse effects, cost, strain on the medical supply chain, and the fact that pressurized metered-dose inhalers emit powerful greenhouse gases. “A lot of patients come in looking for solutions, but really, all the evidence says the over-the-counter cough syrup just doesn’t work. Or I see clinicians prescribing inhalers or different medication that can cost hundreds of dollars, and their efficacy, at least from the literature, shows that there’s really no improvement. Time and patience are the two keys to solving this,” Dr. Liang told this news organization.

Moreover, there is a distinct absence of guidelines on this topic. The College of Family Physicians of Canada’s recent literature review cited limited data supporting a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, a bronchodilator such as ipratropium-salbutamol, or an intranasal steroid if postnasal drip is suspected. However, “there’s a high risk of bias in the study they cite from using the short-acting bronchodilators, and what it ultimately says is that in most cases, this is self-resolving by around the 20-day mark,” said Dr. Liang. “Our advice is just to err on the side of caution and just provide that information piece to the patient.”

‘Significant Nuance’

Imran Satia, MD, assistant professor of respirology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, agreed that “most people who get a viral or bacterial upper or lower respiratory tract infection will get better with time, and there is very little evidence that giving steroids, antibiotics, or cough suppressants is better than waiting it out.” There is “significant nuance” in how to manage this situation, however.

“In some patients with underlying lung disease like asthma or COPD, increasing the frequency of regular inhaled steroids, bronchodilators, oral steroids, antibiotics, and chest imaging with breathing tests may be clinically warranted, and many physicians will do this,” he told this news organization. “In some patients with refractory chronic cough, there is no underlying identifiable disease, despite completing the necessary investigations. Or coughing persists despite trials of treatment for lung diseases, nasal diseases, and stomach reflux disease. This is commonly described as cough hypersensitivity syndrome, for which therapies targeting the neuronal pathways that control coughing are needed.”

Physicians should occasionally consider trying a temporary course of a short-acting bronchodilator inhaler, said Nicholas Vozoris, MD, assistant professor and clinician investigator in respirology at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. “I think that would be a reasonable first step in a case of really bad postinfectious cough,” he told this news organization. “But in general, drug treatments are not indicated.”

Environmental Concerns

Yet some things should raise clinicians’ suspicion of more complex issues.

“A pattern of recurrent colds or bronchitis with protracted coughing afterward raises strong suspicion for asthma, which can present as repeated, prolonged respiratory exacerbations,” he said. “Unless asthma is treated with appropriate inhaler therapy on a regular basis, it will unlikely come under control.”

Dr. Vozoris added that the environmental concerns over the use of metered dose inhalers (MDIs) are minimal compared with the other sources of pollution and the risks for undertreatment. “The authors are overplaying the environmental impact of MDI, in my opinion,” he said. “Physicians already have to deal with the challenging issue of suboptimal patient adherence to inhalers, and I fear that such comments may further drive that up. Furthermore, there is also an environmental footprint with not using inhalers, as patients can then experience suboptimally controlled lung disease as a result — and then present to the ER and get admitted to hospital for exacerbations of disease, where more resources and medications are used up.”

“In addition, in patients who are immunocompromised, protracted coughing after what was thought to be a cold may be associated with an “atypical” respiratory infection, such as tuberculosis, that will require special medical treatment,” Dr. Vozoris concluded.

No funding for the review of postinfectious cough was reported. Dr. Liang and Dr. Vozoris disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Satia reported receiving funding from the ERS Respire 3 Fellowship Award, BMA James Trust Award, North-West Lung Centre Charity (Manchester), NIHR CRF Manchester, Merck MSD, AstraZeneca, and GSK. Dr. Satia also has received consulting fees from Merck MSD, Genentech, and Respiplus; as well as speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck MSD, Sanofi-Regeneron. Satia has served on the following task force committees: Chronic Cough (ERS), Asthma Diagnosis and Management (ERS), NEUROCOUGH (ERS CRC), and the CTS Chronic Cough working group.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lingering postinfectious cough has been a concern across Canada this winter. , according to an overview published on February 12 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal

“It’s something a lot of patients are worried about: That lingering cough after a common cold or flu,” lead author Kevin Liang, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, told this news organization. He added that some studies show that as much as a quarter of adult patients have this complaint.

Dr. Liang and his colleagues emphasized that the diagnosis of postinfectious cough is one of exclusion. It relies on the absence of concerning physical examination findings and other “subacute cough mimics” such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

“Pertussis should be considered in patients with a paroxysmal cough, post-tussive vomiting, and inspiratory whoop,” they added. Coughs that persist beyond 8 weeks warrant further workup such as a pulmonary function test to rule out asthma or COPD. Coughs accompanied by hemoptysis, systemic symptoms, dysphagia, excessive dyspnea, or hoarseness also warrant further workup, they added. And patients with a history of smoking or recurrent pneumonia should be followed more closely.

In the absence of red flags, Dr. Liang and coauthors advised that there is no evidence supporting pharmacologic treatment, “which is associated with harms,” such as medication adverse effects, cost, strain on the medical supply chain, and the fact that pressurized metered-dose inhalers emit powerful greenhouse gases. “A lot of patients come in looking for solutions, but really, all the evidence says the over-the-counter cough syrup just doesn’t work. Or I see clinicians prescribing inhalers or different medication that can cost hundreds of dollars, and their efficacy, at least from the literature, shows that there’s really no improvement. Time and patience are the two keys to solving this,” Dr. Liang told this news organization.

Moreover, there is a distinct absence of guidelines on this topic. The College of Family Physicians of Canada’s recent literature review cited limited data supporting a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, a bronchodilator such as ipratropium-salbutamol, or an intranasal steroid if postnasal drip is suspected. However, “there’s a high risk of bias in the study they cite from using the short-acting bronchodilators, and what it ultimately says is that in most cases, this is self-resolving by around the 20-day mark,” said Dr. Liang. “Our advice is just to err on the side of caution and just provide that information piece to the patient.”

‘Significant Nuance’

Imran Satia, MD, assistant professor of respirology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, agreed that “most people who get a viral or bacterial upper or lower respiratory tract infection will get better with time, and there is very little evidence that giving steroids, antibiotics, or cough suppressants is better than waiting it out.” There is “significant nuance” in how to manage this situation, however.

“In some patients with underlying lung disease like asthma or COPD, increasing the frequency of regular inhaled steroids, bronchodilators, oral steroids, antibiotics, and chest imaging with breathing tests may be clinically warranted, and many physicians will do this,” he told this news organization. “In some patients with refractory chronic cough, there is no underlying identifiable disease, despite completing the necessary investigations. Or coughing persists despite trials of treatment for lung diseases, nasal diseases, and stomach reflux disease. This is commonly described as cough hypersensitivity syndrome, for which therapies targeting the neuronal pathways that control coughing are needed.”

Physicians should occasionally consider trying a temporary course of a short-acting bronchodilator inhaler, said Nicholas Vozoris, MD, assistant professor and clinician investigator in respirology at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. “I think that would be a reasonable first step in a case of really bad postinfectious cough,” he told this news organization. “But in general, drug treatments are not indicated.”

Environmental Concerns

Yet some things should raise clinicians’ suspicion of more complex issues.

“A pattern of recurrent colds or bronchitis with protracted coughing afterward raises strong suspicion for asthma, which can present as repeated, prolonged respiratory exacerbations,” he said. “Unless asthma is treated with appropriate inhaler therapy on a regular basis, it will unlikely come under control.”

Dr. Vozoris added that the environmental concerns over the use of metered dose inhalers (MDIs) are minimal compared with the other sources of pollution and the risks for undertreatment. “The authors are overplaying the environmental impact of MDI, in my opinion,” he said. “Physicians already have to deal with the challenging issue of suboptimal patient adherence to inhalers, and I fear that such comments may further drive that up. Furthermore, there is also an environmental footprint with not using inhalers, as patients can then experience suboptimally controlled lung disease as a result — and then present to the ER and get admitted to hospital for exacerbations of disease, where more resources and medications are used up.”

“In addition, in patients who are immunocompromised, protracted coughing after what was thought to be a cold may be associated with an “atypical” respiratory infection, such as tuberculosis, that will require special medical treatment,” Dr. Vozoris concluded.

No funding for the review of postinfectious cough was reported. Dr. Liang and Dr. Vozoris disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Satia reported receiving funding from the ERS Respire 3 Fellowship Award, BMA James Trust Award, North-West Lung Centre Charity (Manchester), NIHR CRF Manchester, Merck MSD, AstraZeneca, and GSK. Dr. Satia also has received consulting fees from Merck MSD, Genentech, and Respiplus; as well as speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck MSD, Sanofi-Regeneron. Satia has served on the following task force committees: Chronic Cough (ERS), Asthma Diagnosis and Management (ERS), NEUROCOUGH (ERS CRC), and the CTS Chronic Cough working group.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lingering postinfectious cough has been a concern across Canada this winter. , according to an overview published on February 12 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal

“It’s something a lot of patients are worried about: That lingering cough after a common cold or flu,” lead author Kevin Liang, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, told this news organization. He added that some studies show that as much as a quarter of adult patients have this complaint.

Dr. Liang and his colleagues emphasized that the diagnosis of postinfectious cough is one of exclusion. It relies on the absence of concerning physical examination findings and other “subacute cough mimics” such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

“Pertussis should be considered in patients with a paroxysmal cough, post-tussive vomiting, and inspiratory whoop,” they added. Coughs that persist beyond 8 weeks warrant further workup such as a pulmonary function test to rule out asthma or COPD. Coughs accompanied by hemoptysis, systemic symptoms, dysphagia, excessive dyspnea, or hoarseness also warrant further workup, they added. And patients with a history of smoking or recurrent pneumonia should be followed more closely.

In the absence of red flags, Dr. Liang and coauthors advised that there is no evidence supporting pharmacologic treatment, “which is associated with harms,” such as medication adverse effects, cost, strain on the medical supply chain, and the fact that pressurized metered-dose inhalers emit powerful greenhouse gases. “A lot of patients come in looking for solutions, but really, all the evidence says the over-the-counter cough syrup just doesn’t work. Or I see clinicians prescribing inhalers or different medication that can cost hundreds of dollars, and their efficacy, at least from the literature, shows that there’s really no improvement. Time and patience are the two keys to solving this,” Dr. Liang told this news organization.

Moreover, there is a distinct absence of guidelines on this topic. The College of Family Physicians of Canada’s recent literature review cited limited data supporting a trial of inhaled corticosteroids, a bronchodilator such as ipratropium-salbutamol, or an intranasal steroid if postnasal drip is suspected. However, “there’s a high risk of bias in the study they cite from using the short-acting bronchodilators, and what it ultimately says is that in most cases, this is self-resolving by around the 20-day mark,” said Dr. Liang. “Our advice is just to err on the side of caution and just provide that information piece to the patient.”

‘Significant Nuance’

Imran Satia, MD, assistant professor of respirology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, agreed that “most people who get a viral or bacterial upper or lower respiratory tract infection will get better with time, and there is very little evidence that giving steroids, antibiotics, or cough suppressants is better than waiting it out.” There is “significant nuance” in how to manage this situation, however.

“In some patients with underlying lung disease like asthma or COPD, increasing the frequency of regular inhaled steroids, bronchodilators, oral steroids, antibiotics, and chest imaging with breathing tests may be clinically warranted, and many physicians will do this,” he told this news organization. “In some patients with refractory chronic cough, there is no underlying identifiable disease, despite completing the necessary investigations. Or coughing persists despite trials of treatment for lung diseases, nasal diseases, and stomach reflux disease. This is commonly described as cough hypersensitivity syndrome, for which therapies targeting the neuronal pathways that control coughing are needed.”

Physicians should occasionally consider trying a temporary course of a short-acting bronchodilator inhaler, said Nicholas Vozoris, MD, assistant professor and clinician investigator in respirology at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. “I think that would be a reasonable first step in a case of really bad postinfectious cough,” he told this news organization. “But in general, drug treatments are not indicated.”

Environmental Concerns

Yet some things should raise clinicians’ suspicion of more complex issues.

“A pattern of recurrent colds or bronchitis with protracted coughing afterward raises strong suspicion for asthma, which can present as repeated, prolonged respiratory exacerbations,” he said. “Unless asthma is treated with appropriate inhaler therapy on a regular basis, it will unlikely come under control.”

Dr. Vozoris added that the environmental concerns over the use of metered dose inhalers (MDIs) are minimal compared with the other sources of pollution and the risks for undertreatment. “The authors are overplaying the environmental impact of MDI, in my opinion,” he said. “Physicians already have to deal with the challenging issue of suboptimal patient adherence to inhalers, and I fear that such comments may further drive that up. Furthermore, there is also an environmental footprint with not using inhalers, as patients can then experience suboptimally controlled lung disease as a result — and then present to the ER and get admitted to hospital for exacerbations of disease, where more resources and medications are used up.”

“In addition, in patients who are immunocompromised, protracted coughing after what was thought to be a cold may be associated with an “atypical” respiratory infection, such as tuberculosis, that will require special medical treatment,” Dr. Vozoris concluded.

No funding for the review of postinfectious cough was reported. Dr. Liang and Dr. Vozoris disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Satia reported receiving funding from the ERS Respire 3 Fellowship Award, BMA James Trust Award, North-West Lung Centre Charity (Manchester), NIHR CRF Manchester, Merck MSD, AstraZeneca, and GSK. Dr. Satia also has received consulting fees from Merck MSD, Genentech, and Respiplus; as well as speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck MSD, Sanofi-Regeneron. Satia has served on the following task force committees: Chronic Cough (ERS), Asthma Diagnosis and Management (ERS), NEUROCOUGH (ERS CRC), and the CTS Chronic Cough working group.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

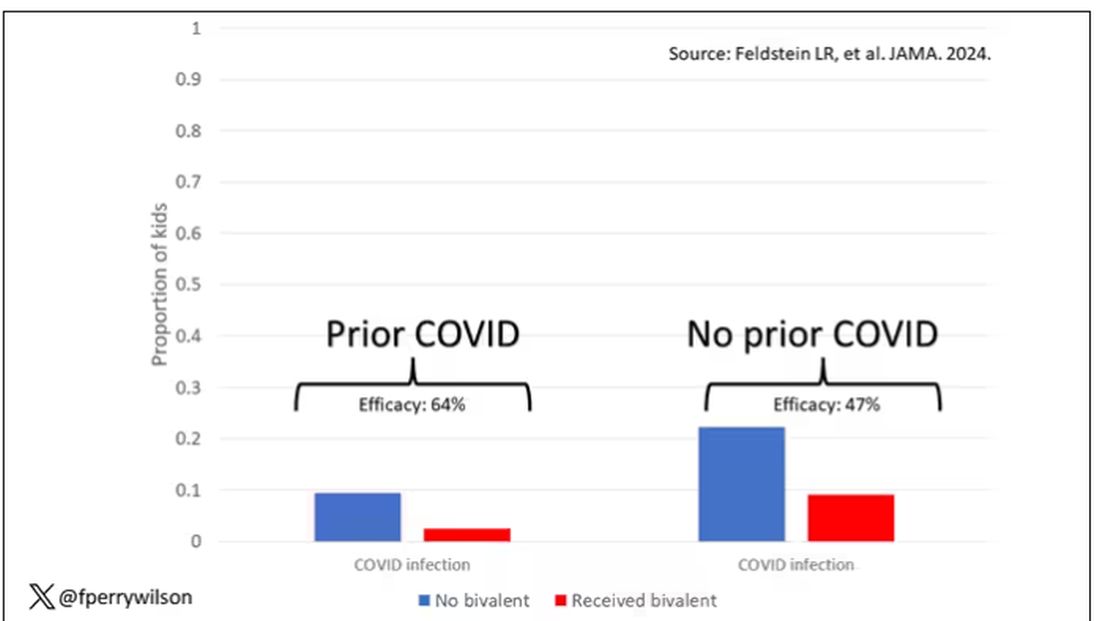

Bivalent Vaccines Protect Even Children Who’ve Had COVID

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.