User login

Generic, brand-name levothyroxine have similar cardiovascular outcomes

VICTORIA, B.C. – Hypothyroid patients have similar cardiovascular outcomes in the shorter term whether they take generic or brand-name levothyroxine, results of a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

Investigators led by Robert Smallridge, MD, an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic, in Jacksonville, Fla., used a large administrative database to study nearly 88,000 treatment-naive hypothyroid patients (most having benign thyroid disease) who started levothyroxine.

However, monthly total medication costs with the brand-name medication were more than twice those with the generic.

“I don’t think we are ready yet to say everybody ought to be on generic,” Dr. Smallridge said in an interview, citing the limited treatment duration captured in the study because patients switched medications or changed insurers. “But I think, at least in the short term, it’s giving us some data that we can build upon.”

He and his coinvestigators plan additional analyses looking at longer-term users, other types of thyroid hormone preparations, and the very small group of patients who had thyroid cancer.

“I primarily take care of cancer patients, and we purposely push these patients to slightly lower [thyroid-stimulating hormone levels] in general, which presumably is going to increase your risk of atrial fibrillation and could affect these events,” he said. “The numbers are somewhat smaller, clearly, but I’d like to see that explored also, to see if there is a difference between brand and generics in that subset who are probably getting a little bit more thyroid medication.”

Both hypothyroidism and its overtreatment with thyroid hormone therapy can increase cardiovascular risk, Dr. Smallridge noted.

For the study, the investigators analyzed data from a large administrative claims database (OptumLabs Data Warehouse) for the years 2006-2014. Patients having any prior use of any thyroid hormone preparation, amiodarone, or lithium were excluded. And patients were censored if they left the insurance plan, stopped treatment, or switched medication category.

The investigators identified 201,056 hypothyroid patients who started some type of thyroid hormone therapy. The majority (70.8%) started generic levothyroxine, and 22.1% started brand-name levothyroxine (Synthroid, Levoxyl, Tirosint, Unithroid). The small remaining group started another thyroid extract, triiodothyronine (T3), or a compounded preparation.

Primary care physicians were the main identifiable prescribers (60.3%), followed by endocrinologists (10.8%). “Endocrinologists tended to prescribe brand significantly more than the primary care physicians,” Dr. Smallridge said.

The investigators used propensity matching on a variety of factors (age, sex, race, census region, Charlson comorbidity index, year of index prescription, and a dozen baseline comorbidities) to compare patients starting brand-name versus generic levothyroxine. Outcomes were assessed during a median follow-up of 1 year (range, 0-9.3 years).

Event rates per 1,000 patient-years with branded versus generic levothyroxine were similar for atrial fibrillation (2.19 vs. 1.82; hazard ratio, 1.22, P = .19), myocardial infarction (1.83 vs. 2.12; HR, 0.86, P = .35), and congestive heart failure (2.00 vs. 2.27; HR, 0.88, P = .41). There was a borderline-significant difference on hospitalization for stroke, with marginally lower risk with brand-name levothyroxine (2.38 vs. 3.10; HR, 0.77; P = .05).

Findings were essentially the same in age-stratified analyses, splitting patients into subgroups younger and older than age 65.

When average 30-day costs were compared for users of branded versus generic levothyroxine, total cost for the branded drug was more than twice as high ($18.47 vs. $8.18).

“Thyroid preparations have been the most prescribed drug in the United States for several recent years. In the neighborhood of 25 million different patients a year take thyroid medications,” Dr. Smallridge said. “In terms of the dollars spent, it’s considerably less than some of the other drugs out there. But because of sheer numbers of patients, in terms of impact on health care dollars, it’s still a significant amount of money. And this is a lifelong treatment – once you go on thyroid hormones, you’re on them for life.”

The study had several strengths. “This is a very large, diverse, real-world population across the entire country with a wide range of ages,” Dr. Smallridge explained. “We got pharmacy claims documenting that they were continuing to get the refills, although we didn’t do pill counts, so we don’t know whether they were taking the medication. And a really important thing was the propensity score matching.”

At the same time, limitations included possible variations in coding and billing, and some residual confounding. “Key issues are that we need more data on longer-term follow-up, and we didn’t have lab values,” he added.

Dr. Smallridge reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Hypothyroid patients have similar cardiovascular outcomes in the shorter term whether they take generic or brand-name levothyroxine, results of a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

Investigators led by Robert Smallridge, MD, an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic, in Jacksonville, Fla., used a large administrative database to study nearly 88,000 treatment-naive hypothyroid patients (most having benign thyroid disease) who started levothyroxine.

However, monthly total medication costs with the brand-name medication were more than twice those with the generic.

“I don’t think we are ready yet to say everybody ought to be on generic,” Dr. Smallridge said in an interview, citing the limited treatment duration captured in the study because patients switched medications or changed insurers. “But I think, at least in the short term, it’s giving us some data that we can build upon.”

He and his coinvestigators plan additional analyses looking at longer-term users, other types of thyroid hormone preparations, and the very small group of patients who had thyroid cancer.

“I primarily take care of cancer patients, and we purposely push these patients to slightly lower [thyroid-stimulating hormone levels] in general, which presumably is going to increase your risk of atrial fibrillation and could affect these events,” he said. “The numbers are somewhat smaller, clearly, but I’d like to see that explored also, to see if there is a difference between brand and generics in that subset who are probably getting a little bit more thyroid medication.”

Both hypothyroidism and its overtreatment with thyroid hormone therapy can increase cardiovascular risk, Dr. Smallridge noted.

For the study, the investigators analyzed data from a large administrative claims database (OptumLabs Data Warehouse) for the years 2006-2014. Patients having any prior use of any thyroid hormone preparation, amiodarone, or lithium were excluded. And patients were censored if they left the insurance plan, stopped treatment, or switched medication category.

The investigators identified 201,056 hypothyroid patients who started some type of thyroid hormone therapy. The majority (70.8%) started generic levothyroxine, and 22.1% started brand-name levothyroxine (Synthroid, Levoxyl, Tirosint, Unithroid). The small remaining group started another thyroid extract, triiodothyronine (T3), or a compounded preparation.

Primary care physicians were the main identifiable prescribers (60.3%), followed by endocrinologists (10.8%). “Endocrinologists tended to prescribe brand significantly more than the primary care physicians,” Dr. Smallridge said.

The investigators used propensity matching on a variety of factors (age, sex, race, census region, Charlson comorbidity index, year of index prescription, and a dozen baseline comorbidities) to compare patients starting brand-name versus generic levothyroxine. Outcomes were assessed during a median follow-up of 1 year (range, 0-9.3 years).

Event rates per 1,000 patient-years with branded versus generic levothyroxine were similar for atrial fibrillation (2.19 vs. 1.82; hazard ratio, 1.22, P = .19), myocardial infarction (1.83 vs. 2.12; HR, 0.86, P = .35), and congestive heart failure (2.00 vs. 2.27; HR, 0.88, P = .41). There was a borderline-significant difference on hospitalization for stroke, with marginally lower risk with brand-name levothyroxine (2.38 vs. 3.10; HR, 0.77; P = .05).

Findings were essentially the same in age-stratified analyses, splitting patients into subgroups younger and older than age 65.

When average 30-day costs were compared for users of branded versus generic levothyroxine, total cost for the branded drug was more than twice as high ($18.47 vs. $8.18).

“Thyroid preparations have been the most prescribed drug in the United States for several recent years. In the neighborhood of 25 million different patients a year take thyroid medications,” Dr. Smallridge said. “In terms of the dollars spent, it’s considerably less than some of the other drugs out there. But because of sheer numbers of patients, in terms of impact on health care dollars, it’s still a significant amount of money. And this is a lifelong treatment – once you go on thyroid hormones, you’re on them for life.”

The study had several strengths. “This is a very large, diverse, real-world population across the entire country with a wide range of ages,” Dr. Smallridge explained. “We got pharmacy claims documenting that they were continuing to get the refills, although we didn’t do pill counts, so we don’t know whether they were taking the medication. And a really important thing was the propensity score matching.”

At the same time, limitations included possible variations in coding and billing, and some residual confounding. “Key issues are that we need more data on longer-term follow-up, and we didn’t have lab values,” he added.

Dr. Smallridge reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Hypothyroid patients have similar cardiovascular outcomes in the shorter term whether they take generic or brand-name levothyroxine, results of a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

Investigators led by Robert Smallridge, MD, an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic, in Jacksonville, Fla., used a large administrative database to study nearly 88,000 treatment-naive hypothyroid patients (most having benign thyroid disease) who started levothyroxine.

However, monthly total medication costs with the brand-name medication were more than twice those with the generic.

“I don’t think we are ready yet to say everybody ought to be on generic,” Dr. Smallridge said in an interview, citing the limited treatment duration captured in the study because patients switched medications or changed insurers. “But I think, at least in the short term, it’s giving us some data that we can build upon.”

He and his coinvestigators plan additional analyses looking at longer-term users, other types of thyroid hormone preparations, and the very small group of patients who had thyroid cancer.

“I primarily take care of cancer patients, and we purposely push these patients to slightly lower [thyroid-stimulating hormone levels] in general, which presumably is going to increase your risk of atrial fibrillation and could affect these events,” he said. “The numbers are somewhat smaller, clearly, but I’d like to see that explored also, to see if there is a difference between brand and generics in that subset who are probably getting a little bit more thyroid medication.”

Both hypothyroidism and its overtreatment with thyroid hormone therapy can increase cardiovascular risk, Dr. Smallridge noted.

For the study, the investigators analyzed data from a large administrative claims database (OptumLabs Data Warehouse) for the years 2006-2014. Patients having any prior use of any thyroid hormone preparation, amiodarone, or lithium were excluded. And patients were censored if they left the insurance plan, stopped treatment, or switched medication category.

The investigators identified 201,056 hypothyroid patients who started some type of thyroid hormone therapy. The majority (70.8%) started generic levothyroxine, and 22.1% started brand-name levothyroxine (Synthroid, Levoxyl, Tirosint, Unithroid). The small remaining group started another thyroid extract, triiodothyronine (T3), or a compounded preparation.

Primary care physicians were the main identifiable prescribers (60.3%), followed by endocrinologists (10.8%). “Endocrinologists tended to prescribe brand significantly more than the primary care physicians,” Dr. Smallridge said.

The investigators used propensity matching on a variety of factors (age, sex, race, census region, Charlson comorbidity index, year of index prescription, and a dozen baseline comorbidities) to compare patients starting brand-name versus generic levothyroxine. Outcomes were assessed during a median follow-up of 1 year (range, 0-9.3 years).

Event rates per 1,000 patient-years with branded versus generic levothyroxine were similar for atrial fibrillation (2.19 vs. 1.82; hazard ratio, 1.22, P = .19), myocardial infarction (1.83 vs. 2.12; HR, 0.86, P = .35), and congestive heart failure (2.00 vs. 2.27; HR, 0.88, P = .41). There was a borderline-significant difference on hospitalization for stroke, with marginally lower risk with brand-name levothyroxine (2.38 vs. 3.10; HR, 0.77; P = .05).

Findings were essentially the same in age-stratified analyses, splitting patients into subgroups younger and older than age 65.

When average 30-day costs were compared for users of branded versus generic levothyroxine, total cost for the branded drug was more than twice as high ($18.47 vs. $8.18).

“Thyroid preparations have been the most prescribed drug in the United States for several recent years. In the neighborhood of 25 million different patients a year take thyroid medications,” Dr. Smallridge said. “In terms of the dollars spent, it’s considerably less than some of the other drugs out there. But because of sheer numbers of patients, in terms of impact on health care dollars, it’s still a significant amount of money. And this is a lifelong treatment – once you go on thyroid hormones, you’re on them for life.”

The study had several strengths. “This is a very large, diverse, real-world population across the entire country with a wide range of ages,” Dr. Smallridge explained. “We got pharmacy claims documenting that they were continuing to get the refills, although we didn’t do pill counts, so we don’t know whether they were taking the medication. And a really important thing was the propensity score matching.”

At the same time, limitations included possible variations in coding and billing, and some residual confounding. “Key issues are that we need more data on longer-term follow-up, and we didn’t have lab values,” he added.

Dr. Smallridge reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients taking brand-name versus generic levothyroxine had similar risks of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.22; P = .19), myocardial infarction (0.86; P = .35), congestive heart failure (0.88; P = .41), and stroke (0.77; P = .05).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 87,902 propensity-matched hypothyroid patients starting generic or brand-name levothyroxine.

Disclosures: Dr. Smallridge reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Autoimmune endocrinopathies spike after celiac disease diagnosis

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Patients diagnosed with celiac disease subsequently showed a high incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies in a review of 249 patients in a longitudinal, population-based database.

The finding that celiac disease patients developed autoimmune endocrinopathies (AE) at a rate of 9.14 cases per person-year of follow-up suggests that “screening for AEs is recommended in treated celiac disease patients,” Imad Absah, MD, said at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the screening focus, and Dr. Asbah recommended a screening interval of every 2 years. Among the 14 patients in the review who developed an AE following a diagnosis of celiac disease, the two most common conditions were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4 patients) and hypothyroidism (4 patients), said Dr. Absah, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. One additional patient developed Graves disease.

He also suggested screening for type 1 diabetes in patients who show symptoms of diabetes. In the review, one patient developed type 1 diabetes following an index diagnosis of celiac disease.

His study used data collected in the Rochester Epidemiology Project on residents of Olmsted County, Minn. during 1997-2015. The database included 90 children and 159 adults less than 80 years old diagnosed with celiac disease after they entered the study. The children averaged 9 years old, and the adults averaged 32 years old; about two-thirds were girls or women.

Fifty-four of these people (22%) had been diagnosed with an AE prior to developing celiac disease, and then an additional 20 people (8%) had an incident AE during an average 5.7 years of follow-up for the children and an average 8.5 years of follow-up among the adults. Six of these 20 patients also had a different AE prior to their celiac disease diagnosis. Dr. Absah censored out these six patients and focused his analysis on the 14 patients with no AE prior to developing celiac disease. The incidence rate in both subgroups was 7%, which worked out to an overall incidence rate of 9.14 cases of AE for every person-year of follow-up in newly diagnosed patients with celiac disease.

Finding similar incidence rates among both children and adults suggests that “the length of gluten exposure prior to celiac disease did not affect the risk for an AE,” Dr. Absah said.

Dr. Absah had no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated 10/30/17.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE WORLD CONGRESS OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Following celiac disease diagnosis, the annual incidence of autoimmune endocrinopathies was 0.9%.

Data source: Review of 249 patients diagnosed with celiac disease in the Rochester Epidemiology Project database.

Disclosures: Dr. Absah had no disclosures.

Hypothyroidism carries higher surgical risk not captured by calculator

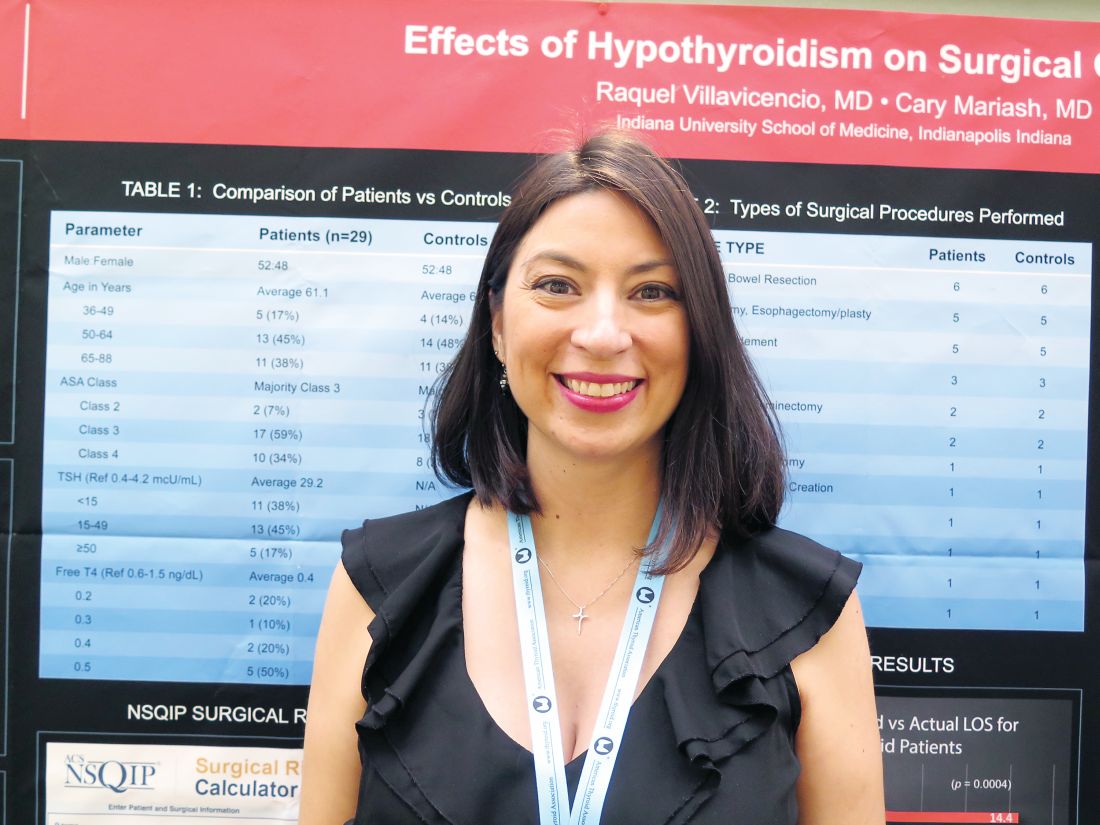

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Even with contemporary anesthesia and surgical techniques, patients who are overtly hypothyroid at the time of major surgery have a rockier course, suggests a retrospective cohort study of 58 patients in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Actual length of stay for hypothyroid patients was twice that predicted by a commonly used risk calculator, whereas actual and predicted stays aligned well for euthyroid patients. The hypothyroid group had more cases of postoperative atrial fibrillation, ileus, reintubation, and death, although numbers were too small for statistical comparison.

“This will have an impact on how we look at patients, especially from a hospital standpoint and management. That’s quite a bit longer stay and quite a bit more cost. And the longer you stay, the more complications you have, too, so it could be riskier for the patient as well,” said first author Raquel Villavicencio, MD, a fellow at Indiana University at the time of the study, and now a clinical endocrinologist at Community Hospital in Indianapolis.

“Although we don’t consider hypothyroidism an absolute contraindication to surgery, especially if it’s necessary surgery, certainly anybody who is having elective surgery should have it postponed, in our opinion, until they are rendered euthyroid,” she said. “More studies are needed to look at this a little bit closer.”

Explaining the study’s rationale, Dr. Villavicencio noted, “This was a question that came up maybe three or four times a year, where we would get a hypothyroid patient and had to decide whether or not to clear them for surgery.”

Previous studies conducted at large institutions, the Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital, had conflicting findings and were done about 30 years ago, she said. Anesthesia and surgical care have improved substantially since then, leading the investigators to hypothesize that hypothyroidism would not carry higher surgical risk today.

Dr. Villavicencio and her coinvestigator, Cary Mariash, MD, used their institutional database to identify 29 adult patients with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of greater than 10 mcU/mL alone or with a TSH level exceeding the upper limit of normal along with a free thyroxine (T4) level of less than 0.6 ng/dL who underwent surgery during 2010-2015. They matched each patient on age, sex, and surgical procedure with a control euthyroid patient.

The mean TSH level in the hypothyroid group was 29.2 mcU/mL. The majority of patients in each group – 59% of the hypothyroid group and 62% of the euthyroid group – had an American Surgical Association class of 3, denoting that this was a fairly sick population. The groups were generally similar on rates of comorbidity, except that the euthyroid patients had a slightly higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea.

In both groups, the majority of procedures were laparotomy and/or bowel resection; pharyngolaryngectomy and esophagectomy/esophagoplasty; and wound or bone debridement.

Main results showed that in the hypothyroid group, hospital length of stay predicted with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator was 6.9 days, but actual length of stay was 14.4 days (P = .0004). In contrast, in the euthyroid group, predicted length of stay was a similar at 7.1 days, and actual length of stay was statistically indistinguishable at 9.2 days (P = .1).

“Hypothyroidism is not taken into account with this calculator,” Dr. Villavicencio noted, adding that she was unaware of any surgical calculators that do.

One patient in the hypothyroid group died, compared with none in the euthyroid group. In terms of postoperative cardiac complications, two patients in the hypothyroid group experienced atrial fibrillation, and there was one case of pulseless electrical–activity arrest in each group.

The groups did not differ on incidence of hypothermia, bradycardia, hyponatremia, time to extubation, and hypotension. However, mean arterial pressure tended to be lower in the hypothyroid group (51 mm Hg) than in the euthyroid group (56 mm Hg), and the former more often needed vasopressors. Furthermore, postoperative ileus and reintubation were more common in the hypothyroid group.

“I think that there are kind of a lot of little things that add up to explain [the longer stay],” said Dr. Villavicencio, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Actual length of stay was significantly longer than calculator-predicted length of stay among hypothyroid patients (14.4 vs. 6.9 days, P = .0004) but not among euthyroid patients (9.2 vs. 7.1 days; P = .1).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 29 hypothyroid patients and 29 matched euthyroid patients undergoing major surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Villavicencio disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Patients prefer higher dose of levothyroxine despite lack of objective benefit

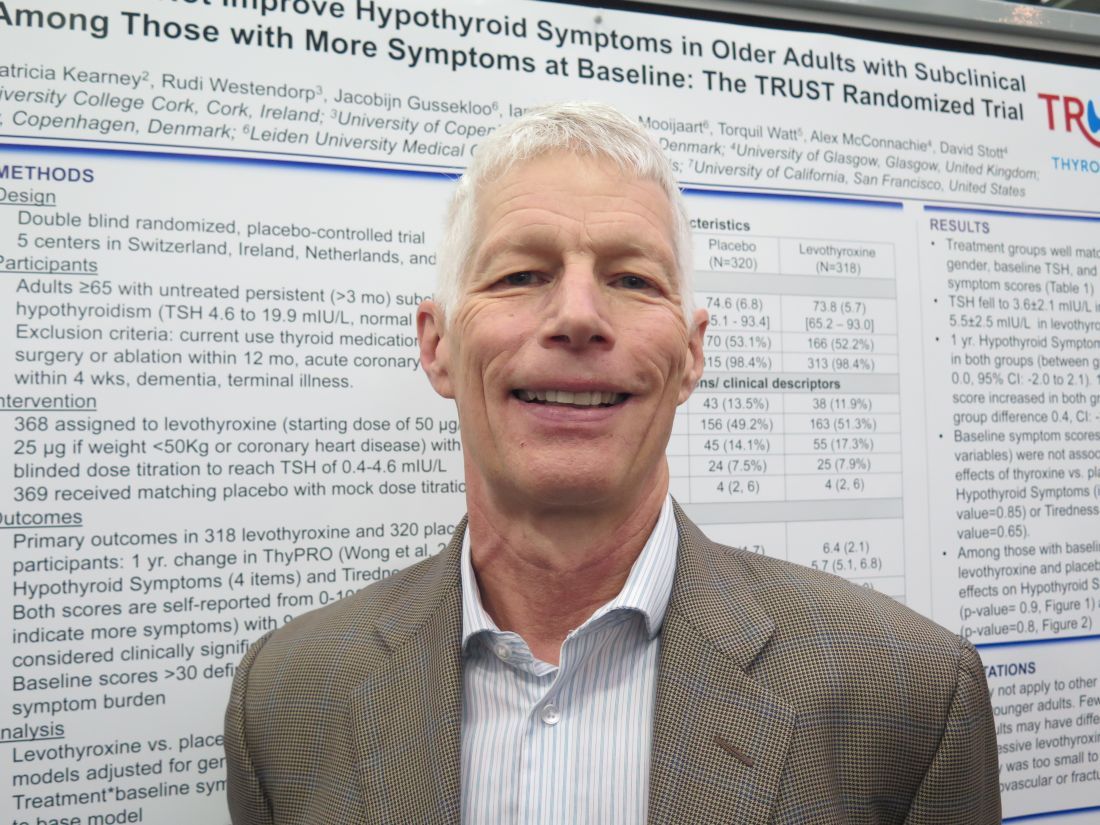

VICTORIA, B.C. – Patient perception plays a large role in subjective benefit of levothyroxine therapy for hypothyroidism, suggests a double-blind randomized controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Mood, cognition, and quality of life (QoL) did not differ whether patients’ levothyroxine dose was adjusted to achieve thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels in the low-normal, high-normal, or mildly elevated range. But despite this lack of objective benefit, the large majority of patients preferred levothyroxine doses that they perceived to be higher – whether they actually were or not.

The study was not restricted to certain groups who might have a better response to higher levothyroxine dose, she acknowledged. Two such groups are patients with more symptoms (although volunteering for the study suggested dissatisfaction with symptom control) and patients with low tri-iodothyronine (T3) levels (although about half of patients had low baseline levels).

“We encourage further research in older subjects, men, and subjects with specific symptoms, low T3 levels, or functional polymorphisms in thyroid-relevant genes,” Dr. Samuels said. “These are really difficult, expensive studies to do, and if we are going to have any hope of getting them funded and doing them, I think that we have to be much more targeted.”

One of the session co-chairs, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “I think these are really interesting data because there’s this sense among patients that their dose really affects how they feel, and this is essentially turning that on its head. It’s not really clear, then, why are these patients still maybe not feeling well.”

“It will be interesting to see more data on this and ... more about this business of checking T3 levels. Do we need to supplement with T3? I think we really don’t know that, especially in kids, but even in adults,” she added.

The other session co-chair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y., commented, “I think this study confirmed what a lot of us feel, that there is a lot of placebo effect when you treat in different ways to optimize the TSH or give T3.”

Other data reported in the session provide a possible explanation for the lack of benefit of adjusting pharmacologic therapy, suggesting that the volumes of various brain structures change with perturbations of thyroid function, he noted. “There might be true changes in the brain that affect how the patients feel. So these patients may truly not feel well. It’s just that we can’t fix it by adjusting the TSH level to very narrow margins or by adding T3,” he said.

Study details

“It is well known that overt hypothyroidism interferes with mood and a number of cognitive functions. However, neurocognitive effects of variations in thyroid function within the reference range and in mild or subclinical hypothyroidism are less clear,” Dr. Samuels noted, giving some background to the research.

“Observational studies of this question have tended to be negative but have often included less sensitive global screening tests of cognition. There are very few small-scale interventional studies,” she continued. “In the absence of conclusive data, many patients with mild hypothyroidism are started on levothyroxine to treat nonspecific quality of life, mood, or cognitive symptoms, and many additional treated patients request increased levothyroxine doses due to persistence of these symptoms.”

Dr. Samuels and her coinvestigators enrolled in the trial 138 hypothyroid but otherwise healthy patients who had been on a stable dose of levothyroxine (Synthroid and others) alone for at least 3 months and had normal TSH levels.

The patients were randomized to three groups in which clinicians adjusted levothyroxine dose every 6 weeks in blinded fashion to achieve different target TSH levels: low-normal TSH (0.34-2.50 mU/L), high-normal TSH (2.51-5.60 mU/L), or mildly elevated TSH (5.60-12.0 mU/L). Patients completed a battery of assessments at baseline and again at 6 months.

Main results confirmed that TSH targets were generally achieved, with significantly different mean TSH levels in the low-normal group (1.34 mU/L), high-normal group (3.74 mU/L), and mildly elevated group (9.74 mU/L) (P less than .05).

In crude analyses, results differed significantly across groups for only two of the dozens of measures of mood, cognition, and QoL assessed: bodily pain (26%, 11%, and 34% of patients reporting a high pain level in the low-normal, high-normal, and mildly elevated TSH groups, respectively; P = .03) and working memory on the N-Back test (86%, 58%, and 75% with a 1-back result; P = .002). However, there were no significant differences for any of the measures when analyses were repeated with statistical correction for multiple comparisons.

At the end of the study, patients were unable to say with any accuracy say whether they were receiving a dose of levothyroxine that was higher than, lower than, or unchanged from their baseline dose (P = .55 for actual vs. perceived).

However, patients preferred what they perceived to be a higher dose (P less than .001 for preferred vs. perceived). In the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was higher, the majority of patients (68%) preferred that dose, and in the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was lower, most (96%) preferred their baseline dose.

The sample size may not have been adequate to detect very small effects of changes in levothyroxine dose, acknowledged Dr. Samuels, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest. Additionally, patients were predominantly female and younger, and heterogeneous with respect to thyroid diagnosis and length of levothyroxine therapy.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Patient perception plays a large role in subjective benefit of levothyroxine therapy for hypothyroidism, suggests a double-blind randomized controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Mood, cognition, and quality of life (QoL) did not differ whether patients’ levothyroxine dose was adjusted to achieve thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels in the low-normal, high-normal, or mildly elevated range. But despite this lack of objective benefit, the large majority of patients preferred levothyroxine doses that they perceived to be higher – whether they actually were or not.

The study was not restricted to certain groups who might have a better response to higher levothyroxine dose, she acknowledged. Two such groups are patients with more symptoms (although volunteering for the study suggested dissatisfaction with symptom control) and patients with low tri-iodothyronine (T3) levels (although about half of patients had low baseline levels).

“We encourage further research in older subjects, men, and subjects with specific symptoms, low T3 levels, or functional polymorphisms in thyroid-relevant genes,” Dr. Samuels said. “These are really difficult, expensive studies to do, and if we are going to have any hope of getting them funded and doing them, I think that we have to be much more targeted.”

One of the session co-chairs, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “I think these are really interesting data because there’s this sense among patients that their dose really affects how they feel, and this is essentially turning that on its head. It’s not really clear, then, why are these patients still maybe not feeling well.”

“It will be interesting to see more data on this and ... more about this business of checking T3 levels. Do we need to supplement with T3? I think we really don’t know that, especially in kids, but even in adults,” she added.

The other session co-chair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y., commented, “I think this study confirmed what a lot of us feel, that there is a lot of placebo effect when you treat in different ways to optimize the TSH or give T3.”

Other data reported in the session provide a possible explanation for the lack of benefit of adjusting pharmacologic therapy, suggesting that the volumes of various brain structures change with perturbations of thyroid function, he noted. “There might be true changes in the brain that affect how the patients feel. So these patients may truly not feel well. It’s just that we can’t fix it by adjusting the TSH level to very narrow margins or by adding T3,” he said.

Study details

“It is well known that overt hypothyroidism interferes with mood and a number of cognitive functions. However, neurocognitive effects of variations in thyroid function within the reference range and in mild or subclinical hypothyroidism are less clear,” Dr. Samuels noted, giving some background to the research.

“Observational studies of this question have tended to be negative but have often included less sensitive global screening tests of cognition. There are very few small-scale interventional studies,” she continued. “In the absence of conclusive data, many patients with mild hypothyroidism are started on levothyroxine to treat nonspecific quality of life, mood, or cognitive symptoms, and many additional treated patients request increased levothyroxine doses due to persistence of these symptoms.”

Dr. Samuels and her coinvestigators enrolled in the trial 138 hypothyroid but otherwise healthy patients who had been on a stable dose of levothyroxine (Synthroid and others) alone for at least 3 months and had normal TSH levels.

The patients were randomized to three groups in which clinicians adjusted levothyroxine dose every 6 weeks in blinded fashion to achieve different target TSH levels: low-normal TSH (0.34-2.50 mU/L), high-normal TSH (2.51-5.60 mU/L), or mildly elevated TSH (5.60-12.0 mU/L). Patients completed a battery of assessments at baseline and again at 6 months.

Main results confirmed that TSH targets were generally achieved, with significantly different mean TSH levels in the low-normal group (1.34 mU/L), high-normal group (3.74 mU/L), and mildly elevated group (9.74 mU/L) (P less than .05).

In crude analyses, results differed significantly across groups for only two of the dozens of measures of mood, cognition, and QoL assessed: bodily pain (26%, 11%, and 34% of patients reporting a high pain level in the low-normal, high-normal, and mildly elevated TSH groups, respectively; P = .03) and working memory on the N-Back test (86%, 58%, and 75% with a 1-back result; P = .002). However, there were no significant differences for any of the measures when analyses were repeated with statistical correction for multiple comparisons.

At the end of the study, patients were unable to say with any accuracy say whether they were receiving a dose of levothyroxine that was higher than, lower than, or unchanged from their baseline dose (P = .55 for actual vs. perceived).

However, patients preferred what they perceived to be a higher dose (P less than .001 for preferred vs. perceived). In the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was higher, the majority of patients (68%) preferred that dose, and in the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was lower, most (96%) preferred their baseline dose.

The sample size may not have been adequate to detect very small effects of changes in levothyroxine dose, acknowledged Dr. Samuels, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest. Additionally, patients were predominantly female and younger, and heterogeneous with respect to thyroid diagnosis and length of levothyroxine therapy.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Patient perception plays a large role in subjective benefit of levothyroxine therapy for hypothyroidism, suggests a double-blind randomized controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Mood, cognition, and quality of life (QoL) did not differ whether patients’ levothyroxine dose was adjusted to achieve thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels in the low-normal, high-normal, or mildly elevated range. But despite this lack of objective benefit, the large majority of patients preferred levothyroxine doses that they perceived to be higher – whether they actually were or not.

The study was not restricted to certain groups who might have a better response to higher levothyroxine dose, she acknowledged. Two such groups are patients with more symptoms (although volunteering for the study suggested dissatisfaction with symptom control) and patients with low tri-iodothyronine (T3) levels (although about half of patients had low baseline levels).

“We encourage further research in older subjects, men, and subjects with specific symptoms, low T3 levels, or functional polymorphisms in thyroid-relevant genes,” Dr. Samuels said. “These are really difficult, expensive studies to do, and if we are going to have any hope of getting them funded and doing them, I think that we have to be much more targeted.”

One of the session co-chairs, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “I think these are really interesting data because there’s this sense among patients that their dose really affects how they feel, and this is essentially turning that on its head. It’s not really clear, then, why are these patients still maybe not feeling well.”

“It will be interesting to see more data on this and ... more about this business of checking T3 levels. Do we need to supplement with T3? I think we really don’t know that, especially in kids, but even in adults,” she added.

The other session co-chair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y., commented, “I think this study confirmed what a lot of us feel, that there is a lot of placebo effect when you treat in different ways to optimize the TSH or give T3.”

Other data reported in the session provide a possible explanation for the lack of benefit of adjusting pharmacologic therapy, suggesting that the volumes of various brain structures change with perturbations of thyroid function, he noted. “There might be true changes in the brain that affect how the patients feel. So these patients may truly not feel well. It’s just that we can’t fix it by adjusting the TSH level to very narrow margins or by adding T3,” he said.

Study details

“It is well known that overt hypothyroidism interferes with mood and a number of cognitive functions. However, neurocognitive effects of variations in thyroid function within the reference range and in mild or subclinical hypothyroidism are less clear,” Dr. Samuels noted, giving some background to the research.

“Observational studies of this question have tended to be negative but have often included less sensitive global screening tests of cognition. There are very few small-scale interventional studies,” she continued. “In the absence of conclusive data, many patients with mild hypothyroidism are started on levothyroxine to treat nonspecific quality of life, mood, or cognitive symptoms, and many additional treated patients request increased levothyroxine doses due to persistence of these symptoms.”

Dr. Samuels and her coinvestigators enrolled in the trial 138 hypothyroid but otherwise healthy patients who had been on a stable dose of levothyroxine (Synthroid and others) alone for at least 3 months and had normal TSH levels.

The patients were randomized to three groups in which clinicians adjusted levothyroxine dose every 6 weeks in blinded fashion to achieve different target TSH levels: low-normal TSH (0.34-2.50 mU/L), high-normal TSH (2.51-5.60 mU/L), or mildly elevated TSH (5.60-12.0 mU/L). Patients completed a battery of assessments at baseline and again at 6 months.

Main results confirmed that TSH targets were generally achieved, with significantly different mean TSH levels in the low-normal group (1.34 mU/L), high-normal group (3.74 mU/L), and mildly elevated group (9.74 mU/L) (P less than .05).

In crude analyses, results differed significantly across groups for only two of the dozens of measures of mood, cognition, and QoL assessed: bodily pain (26%, 11%, and 34% of patients reporting a high pain level in the low-normal, high-normal, and mildly elevated TSH groups, respectively; P = .03) and working memory on the N-Back test (86%, 58%, and 75% with a 1-back result; P = .002). However, there were no significant differences for any of the measures when analyses were repeated with statistical correction for multiple comparisons.

At the end of the study, patients were unable to say with any accuracy say whether they were receiving a dose of levothyroxine that was higher than, lower than, or unchanged from their baseline dose (P = .55 for actual vs. perceived).

However, patients preferred what they perceived to be a higher dose (P less than .001 for preferred vs. perceived). In the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was higher, the majority of patients (68%) preferred that dose, and in the group perceiving their end-of-study dose was lower, most (96%) preferred their baseline dose.

The sample size may not have been adequate to detect very small effects of changes in levothyroxine dose, acknowledged Dr. Samuels, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest. Additionally, patients were predominantly female and younger, and heterogeneous with respect to thyroid diagnosis and length of levothyroxine therapy.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mood, cognition, and QoL were similar across levothyroxine doses targeting various TSH levels, but patients preferred what they believed was a higher dose, even when it was not (P less than .001 for preferred vs. perceived).

Data source: A randomized trial of levothyroxine adjustment among 138 hypothyroid patients on a stable dose of the drug who had normal TSH levels.

Disclosures: Dr. Samuels disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Long-term methimazole therapy improves Graves disease remission rate

VICTORIA, B.C. – In the debate over the optimal duration of methimazole therapy for Graves disease, findings of a new randomized, controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association tip the balance in favor of long-term therapy.

The relapse rate among patients who stayed on the drug long term, for a median of 96 months, was about one-third that among patients who stopped after 18 months, reported lead investigator Fereidoun Azizi, MD, of the Endocrine Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. Patients staying on the drug long term did not experience any adverse effects during that time, although only those able to tolerate the drug initially were randomized.

There may be two explanations for this benefit of long-term therapy, according to Dr. Azizi. Long-term therapy may alter immune-related molecular signaling and cell subsets in both the thymus and periphery, ultimately shifting disease course. On the other hand, establishing and maintaining euthyroidism for a prolonged period of time may quell the autoimmune response.

“We are looking at this in depth and also at some of the [molecular factors] in order to elucidate the mechanism behind our striking findings,” he said.

One of the session cochairs, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, commented, “There is a move today away from radioactive iodine – many patients do not want radioactive iodine, and we do more surgery now because of that. So this opens up a new option that we didn’t have before.”

The other session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., noted that duration of therapy frequently comes up in her practice.

Study details

Relapse of hyperthyroidism after discontinuation of antithyroid drugs remains problematic, Dr. Azizi pointed out when introducing the study.

“Many of the major papers have noted that longer antithyroid drug treatment does not really influence remission rate of Graves, and therefore most of us treat for between 12 and 24 months with antithyroid drugs, and then we stop the medication,” he said. However, recent studies and in particular a meta-analysis (Thyroid. 2017;27:1223-31) suggest there may be an advantage of long-term therapy.

Dr. Azizi and coinvestigators recruited to their trial 302 consecutive patients from a single clinic who had untreated Graves disease and were started on methimazole (Tapazole) therapy.

The 258 patients completing 18 months of therapy were randomized to stop the drug or continue on a maintenance dose long term, for 60-120 months, on a single-blind basis. (The other 44 patients withdrew mainly because of side effects, relapse, and loss to follow-up.)

Patients in the long-term therapy group stayed on the drug for a median of 96 months. The decision about specifically when to stop in this group was guided by thyroid function test results and patients’ clinical status and preferences, according to Dr. Azizi.

The rate of relapse at 48 months after stopping methimazole was 51% among patients in the short-term therapy group but just 16% among patients in the long-term therapy group (P less than or equal to .001). “Definitely, this looks like a cure of the disease if we consider this very low incidence of relapse,” he commented.

Within the group treated long term, patients who did and did not experience relapse were statistically indistinguishable with respect to temporal trends in levels of triiodothyronine (T3), free thyroxine (T4), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb).

Additionally, the daily dose of methimazole therapy required to maintain TSH levels in the normal range fell similarly over time, to about half the initial dose, regardless of whether patients had a relapse or not.

“At the end of treatment, the majority of patients were taking less than 5 mg/day of methimazole,” Dr. Azizi reported. “Some patients needed only two or three pills of 5-mg methimazole per week, and this is very interesting to know, that after you continue, you have definitely more response to methimazole.”

Multivariate analyses showed that in the short-term therapy group, risk factors for relapse were age, sex, and end-of-therapy levels of T3, TSH, and TRAb. In the long-term therapy group, risk factors were end-of-therapy levels of free T4 and TSH.

“We are currently performing more in-depth analysis of genetic markers, including both SNPs [single nucleotide polymorphisms] and HLA [human leukocyte antigen] subtyping on these samples to assess any potential association between relapse rates and genetic background,” Dr. Azizi noted. “However, the problem is the low number of patients who have had a relapse long term.”

During the first 18 months of methimazole therapy, 16 patients had adverse effects in the first 2 months (14 had cutaneous reactions and 2 had elevation of liver enzymes). However, there were no serious complications, such as agranulocytosis.

“It’s very reassuring that after 18 months, in those who had long-term treatment, we did not see any minor or major complications throughout, up to the 120 months of treatment we have had in some of our patients,” Dr. Azizi commented.

Dr. Azizi disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – In the debate over the optimal duration of methimazole therapy for Graves disease, findings of a new randomized, controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association tip the balance in favor of long-term therapy.

The relapse rate among patients who stayed on the drug long term, for a median of 96 months, was about one-third that among patients who stopped after 18 months, reported lead investigator Fereidoun Azizi, MD, of the Endocrine Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. Patients staying on the drug long term did not experience any adverse effects during that time, although only those able to tolerate the drug initially were randomized.

There may be two explanations for this benefit of long-term therapy, according to Dr. Azizi. Long-term therapy may alter immune-related molecular signaling and cell subsets in both the thymus and periphery, ultimately shifting disease course. On the other hand, establishing and maintaining euthyroidism for a prolonged period of time may quell the autoimmune response.

“We are looking at this in depth and also at some of the [molecular factors] in order to elucidate the mechanism behind our striking findings,” he said.

One of the session cochairs, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, commented, “There is a move today away from radioactive iodine – many patients do not want radioactive iodine, and we do more surgery now because of that. So this opens up a new option that we didn’t have before.”

The other session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., noted that duration of therapy frequently comes up in her practice.

Study details

Relapse of hyperthyroidism after discontinuation of antithyroid drugs remains problematic, Dr. Azizi pointed out when introducing the study.

“Many of the major papers have noted that longer antithyroid drug treatment does not really influence remission rate of Graves, and therefore most of us treat for between 12 and 24 months with antithyroid drugs, and then we stop the medication,” he said. However, recent studies and in particular a meta-analysis (Thyroid. 2017;27:1223-31) suggest there may be an advantage of long-term therapy.

Dr. Azizi and coinvestigators recruited to their trial 302 consecutive patients from a single clinic who had untreated Graves disease and were started on methimazole (Tapazole) therapy.

The 258 patients completing 18 months of therapy were randomized to stop the drug or continue on a maintenance dose long term, for 60-120 months, on a single-blind basis. (The other 44 patients withdrew mainly because of side effects, relapse, and loss to follow-up.)

Patients in the long-term therapy group stayed on the drug for a median of 96 months. The decision about specifically when to stop in this group was guided by thyroid function test results and patients’ clinical status and preferences, according to Dr. Azizi.

The rate of relapse at 48 months after stopping methimazole was 51% among patients in the short-term therapy group but just 16% among patients in the long-term therapy group (P less than or equal to .001). “Definitely, this looks like a cure of the disease if we consider this very low incidence of relapse,” he commented.

Within the group treated long term, patients who did and did not experience relapse were statistically indistinguishable with respect to temporal trends in levels of triiodothyronine (T3), free thyroxine (T4), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb).

Additionally, the daily dose of methimazole therapy required to maintain TSH levels in the normal range fell similarly over time, to about half the initial dose, regardless of whether patients had a relapse or not.

“At the end of treatment, the majority of patients were taking less than 5 mg/day of methimazole,” Dr. Azizi reported. “Some patients needed only two or three pills of 5-mg methimazole per week, and this is very interesting to know, that after you continue, you have definitely more response to methimazole.”

Multivariate analyses showed that in the short-term therapy group, risk factors for relapse were age, sex, and end-of-therapy levels of T3, TSH, and TRAb. In the long-term therapy group, risk factors were end-of-therapy levels of free T4 and TSH.

“We are currently performing more in-depth analysis of genetic markers, including both SNPs [single nucleotide polymorphisms] and HLA [human leukocyte antigen] subtyping on these samples to assess any potential association between relapse rates and genetic background,” Dr. Azizi noted. “However, the problem is the low number of patients who have had a relapse long term.”

During the first 18 months of methimazole therapy, 16 patients had adverse effects in the first 2 months (14 had cutaneous reactions and 2 had elevation of liver enzymes). However, there were no serious complications, such as agranulocytosis.

“It’s very reassuring that after 18 months, in those who had long-term treatment, we did not see any minor or major complications throughout, up to the 120 months of treatment we have had in some of our patients,” Dr. Azizi commented.

Dr. Azizi disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – In the debate over the optimal duration of methimazole therapy for Graves disease, findings of a new randomized, controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association tip the balance in favor of long-term therapy.

The relapse rate among patients who stayed on the drug long term, for a median of 96 months, was about one-third that among patients who stopped after 18 months, reported lead investigator Fereidoun Azizi, MD, of the Endocrine Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. Patients staying on the drug long term did not experience any adverse effects during that time, although only those able to tolerate the drug initially were randomized.

There may be two explanations for this benefit of long-term therapy, according to Dr. Azizi. Long-term therapy may alter immune-related molecular signaling and cell subsets in both the thymus and periphery, ultimately shifting disease course. On the other hand, establishing and maintaining euthyroidism for a prolonged period of time may quell the autoimmune response.

“We are looking at this in depth and also at some of the [molecular factors] in order to elucidate the mechanism behind our striking findings,” he said.

One of the session cochairs, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, commented, “There is a move today away from radioactive iodine – many patients do not want radioactive iodine, and we do more surgery now because of that. So this opens up a new option that we didn’t have before.”

The other session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., noted that duration of therapy frequently comes up in her practice.

Study details

Relapse of hyperthyroidism after discontinuation of antithyroid drugs remains problematic, Dr. Azizi pointed out when introducing the study.

“Many of the major papers have noted that longer antithyroid drug treatment does not really influence remission rate of Graves, and therefore most of us treat for between 12 and 24 months with antithyroid drugs, and then we stop the medication,” he said. However, recent studies and in particular a meta-analysis (Thyroid. 2017;27:1223-31) suggest there may be an advantage of long-term therapy.

Dr. Azizi and coinvestigators recruited to their trial 302 consecutive patients from a single clinic who had untreated Graves disease and were started on methimazole (Tapazole) therapy.

The 258 patients completing 18 months of therapy were randomized to stop the drug or continue on a maintenance dose long term, for 60-120 months, on a single-blind basis. (The other 44 patients withdrew mainly because of side effects, relapse, and loss to follow-up.)

Patients in the long-term therapy group stayed on the drug for a median of 96 months. The decision about specifically when to stop in this group was guided by thyroid function test results and patients’ clinical status and preferences, according to Dr. Azizi.

The rate of relapse at 48 months after stopping methimazole was 51% among patients in the short-term therapy group but just 16% among patients in the long-term therapy group (P less than or equal to .001). “Definitely, this looks like a cure of the disease if we consider this very low incidence of relapse,” he commented.

Within the group treated long term, patients who did and did not experience relapse were statistically indistinguishable with respect to temporal trends in levels of triiodothyronine (T3), free thyroxine (T4), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb).

Additionally, the daily dose of methimazole therapy required to maintain TSH levels in the normal range fell similarly over time, to about half the initial dose, regardless of whether patients had a relapse or not.

“At the end of treatment, the majority of patients were taking less than 5 mg/day of methimazole,” Dr. Azizi reported. “Some patients needed only two or three pills of 5-mg methimazole per week, and this is very interesting to know, that after you continue, you have definitely more response to methimazole.”

Multivariate analyses showed that in the short-term therapy group, risk factors for relapse were age, sex, and end-of-therapy levels of T3, TSH, and TRAb. In the long-term therapy group, risk factors were end-of-therapy levels of free T4 and TSH.

“We are currently performing more in-depth analysis of genetic markers, including both SNPs [single nucleotide polymorphisms] and HLA [human leukocyte antigen] subtyping on these samples to assess any potential association between relapse rates and genetic background,” Dr. Azizi noted. “However, the problem is the low number of patients who have had a relapse long term.”

During the first 18 months of methimazole therapy, 16 patients had adverse effects in the first 2 months (14 had cutaneous reactions and 2 had elevation of liver enzymes). However, there were no serious complications, such as agranulocytosis.

“It’s very reassuring that after 18 months, in those who had long-term treatment, we did not see any minor or major complications throughout, up to the 120 months of treatment we have had in some of our patients,” Dr. Azizi commented.

Dr. Azizi disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Relative to peers who stopped methimazole after 18 months, patients who continued on the drug for a median of 96 months had a lower rate of relapse after discontinuation (51% vs. 16%; P less than or equal to .001).

Data source: A randomized controlled trial among 258 patients with Graves disease who were relapse free after 18 months on methimazole.

Disclosures: Dr. Azizi disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Add-on mycophenolate boosts efficacy of steroids for Graves’ orbitopathy

VICTORIA, B.C. – Adding a nonsteroidal immunosuppressant to steroid therapy improves control of active, moderate-to-severe Graves’ orbitopathy, according to findings from a randomized controlled trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

Relative to counterparts given pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone alone, patients also given oral mycophenolate were twice as likely to achieve reduction of their ophthalmic signs and symptoms, first author George J. Kahaly, MD, PhD, reported in a session on behalf of the European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO). And the combination was generally safe and well tolerated.

“Since there is a clear advantage of combination treatment in response rate, in the absence of contraindication to mycophenolate, patients with active and severe orbitopathy may be considered for combination treatment,” he proposed.

A session attendee noted that a similar recent study from China suggests that mycophenolate monotherapy achieves a very high remission rate in this patient population (Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86[2]:247-55). “Why don’t we just go for [mycophenolate] alone? Why keep pushing steroids?” he asked.

Methodology of that study was less rigorous, maintained Dr. Kahaly, who is professor of medicine and endocrinology/metabolism, chief physician of the endocrine outpatient clinic, and director of the thyroid research lab at Gutenberg University Medical Center in Mainz, Germany.

“I would say mycophenolate alone is not a powerful enough treatment to observe a response rate of 70%, 80%, 90%,” he stated. “You need more time. This is a lymphocyte-inhibiting agent, so you need the acute effect of the intravenous steroids at the beginning.”

Session cochair Angela M. Leung, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an endocrinologist at both UCLA and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, commented, “This is an intriguing study with very promising data from an active group of investigators.”

At the same time, benefit of add-on mycophenolate remains uncertain, in her opinion. “Clearly, more studies, perhaps longer-duration ones, are needed to assess the true effect and clinical efficacy,” she said.

Introducing the EUGOGO trial, Dr. Kahaly noted that European guidelines recommend intravenous methylprednisolone as first-line therapy for Graves’ orbitopathy that is moderate to severe or sight threatening (Eur Thyroid J. 2016;5:9-26). Some patients, however, do not achieve response on this therapy, and others who do achieve response then go on to experience relapse, underscoring the need for better therapies.

The combination the investigators selected pairs the anti-inflammatory activity of methylprednisolone with the antiproliferative activity of mycophenolate (CellCept), which is mainly used in the transplantation field.

The trial, funded in part by Novartis, was open to patients with Graves’ disease who had been euthyroid for at least 2 months but had untreated, active, moderate-to-severe orbitopathy with involvement of soft tissues and eye muscles. Those with optic neuropathy were excluded.

Patients were randomized to 12 weeks of once-weekly intravenous methylprednisolone either alone or with the addition of 24 weeks of twice-daily oral mycophenolate initiated at the same time.

Blinded observers assessed patients for orbitopathy response, defined as improvement in two or more of six outcome measures (eyelid swelling, clinical activity score, proptosis, lid width, diplopia, and motility) in at least one eye, without deterioration in any of the same measures in either eye.

Results showed that the 24-week rate of response was 71% with methylprednisolone plus mycophenolate and 53% with methylprednisolone alone (odds ratio, 2.16; P = .026).

Dr. Kahaly acknowledged that the rate in the monotherapy group was lower than that in some in past studies and proposed this was due to both a tightening of response criteria and more conservative steroid dosing in recent years.

Benefit was similar across patient subgroups stratified by sex, smoking history, clinical activity score, duration of orbitopathy, and level of antibodies to the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor.

The group given combination therapy also had a lower 36-week relapse rate, although this difference was not significant (4% vs. 8%; odds ratio, 0.65; P = .613). Quality-of-life scores improved in both the monotherapy group (P = .009) and the combination therapy group (P = .002).

The difference between groups in extent of proptosis was just 1 mm. “This is not enough,” he asserted, noting that teprotumumab, an investigational antibody that inhibits insulin-like growth factor I receptor, was recently found to decrease proptosis in this population by 2.7 mm (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1748-61). “This is the only drug that has led to a significant decrease of proptosis,” he noted.

“The drugs were well tolerated, and the treatment went smoothly. We didn’t have one single dropout because of drug side effects,” Dr. Kahaly reported.