User login

GI Doc Empowers Female Patients ‘To Be Themselves’

Pooja Singhal, MD, AGAF, will never forget the time a female patient came in for gastroesophageal reflux disease and dysphagia treatment, revealing that she had already gone through multiple gastroenterologists to help diagnose and treat her ailments.

“We spent a whole visit talking about it,” said Dr. Singhal, a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, and obesity medicine specialist at Oklahoma Gastro Health and Wellness in Oklahoma City. During the exam, she discovered that her middle-aged patient was wearing an adult diaper for diarrhea and leakage.

Previous GI doctors told the patient they couldn’t help her and that she had to live with these symptoms. “I was just so shocked. I told her: This is not normal. Let’s talk more about it. Let’s figure out how we can manage it,” said Dr. Singhal, who has spent her career advocating for more education about GI conditions.

There are real barriers to patients opening up and sharing their symptoms, especially if they’re female. while ensuring that the correct knowledge gets across to the public, said Dr. Singhal.

An alumna of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program, Dr. Singhal has served as the private practice course director for AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop. She is a also a four-time recipient of the SCOPY award for her work in raising community awareness of colorectal cancer prevention in Oklahoma. In an interview, she discussed the critical role women GI doctors play in assisting the unique needs of female patients, and why it takes a village of doctors to treat the complexities of GI disorders.

Why did you choose GI, and more specifically, what brought about your interest in women’s GI issues?

GI is simply the best field. While I was doing my rotation in GI as a resident, I was enthralled and humbled that the field of gastroenterology offered an opportunity to prevent cancer. Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer related deaths, and when I realized that we could do these micro-interventions during a procedure to remove polyps that could potentially turn into cancer — or give us an opportunity to remove carcinoma in situ — that’s what really inspired me and piqued my interest in GI. As I continued to learn and explore GI more, I appreciated the opportunity the field gave us in terms of using both sides of our brains equally, the right side and the left side.

I love the diagnostic part of medicine. You have this privilege to be able to diagnose so many different diseases and perform procedures using technical skills, exploring everything from the esophagus, liver, pancreas, small bowel, and colon.

But what I really appreciate about gastroenterology is how it’s piqued my interest in women’s digestive health. How it became very close to my heart is really from my patients. I’ve learned a lot from my patients throughout the years. When I was much younger, I don’t know if I really appreciated the vulnerability it takes as a woman to go to a physician and talk about hemorrhoids and diarrhea.

One of the comments I often receive is: ‘Oh, thank God you’re a female GI. I can be myself. I can share something personal and you would understand.’

Your practice places a specific emphasis on health and wellness. Can you provide some examples of how you incorporate wellness into treatment?

I feel like wellness is very commonplace now. To me, the definition of wellness is about practicing healthy habits to attain your maximum potential, both physically and mentally — to feel the best you can. My practice specifically tries to achieve that goal by placing a strong emphasis on education and communication. We provide journals where patients can keep track of their symptoms. We encourage a lot of discussion during visits, where we talk about GI diseases and how to prevent them, or to prevent them from happening again. If you’re going to do a hemorrhoid treatment that offers hemorrhoid banding, we talk about it in detail with the patient; we don’t just do the procedure.

We have a dietitian on staff for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, IBS. Some of our older patients have pelvic organ prolapse and fecal incontinence. We have a pelvic floor therapist and a urogynecologist, and we work very closely with ob-gyn teams. My practice also takes pride in communicating with primary care physicians. We’ve had patients who have had memory loss or dementia or are grieving the loss of a loved one. And we prioritize communicating and treating patients as a whole and not focusing on just their GI symptoms.

As an advocate for community education on GI disorders, where is education lacking in this field?

I think education is lacking because there is an information delivery gap. I feel the public consumes information in the form of short social media reels. The attention span is so short and any scientific information, especially around diseases, can be scary and overwhelming. Whereas I think a lot of the medical community still interacts and exchanges information in terms of journals and publications. So, we are not really trained necessarily to talk about diseases in very simple terms.

We need more advocacy efforts on Capitol Hill. AGA has been good about doing advocacy work. I had an opportunity to go to Capitol Hill a couple of times and really advocate for policy around obesity medicine coverage and procedure coverage. I was fortunate to learn so much about healthcare policy, but it also made me appreciate that there are a lot of gaps in terms of understanding common medical diseases.

You’re trained in the Orbera Intragastric balloon system for weight reduction. How does this procedure differentiate from other bariatric procedures?

Intragastric balloon is Food and Drug Administration approved for weight loss. It’s a temporary medical device, so it’s reversible. No. 2, it’s a nonsurgical intervention, so it’s usually done in an outpatient setting. We basically place a deflated gastric balloon endoscopically, similar to an upper endoscopy method. We take a pin endoscope, a deflated balloon, which is made of medical-grade material, and we inflate it with adequate fluid. The concept is when the balloon is inflated, it provides satiety. It reduces the amount of space in the stomach for food. It slows down how quickly the food is going to leave. So you feel full much of the time. And it also helps decrease a hormone called ghrelin, which is responsible for hunger. It can make a big difference when people are gaining weight and in that category of overweight before they progress to obese.

As I tell everybody, obesity is a chronic lifelong disease that is very complex and requires lifelong efforts. So, it’s truly a journey. What’s made this procedure a success is follow-up and the continued efforts of dietitians and counseling and incorporating physical exercise, because maintenance of that weight loss is also very important. Our goal is always sustained weight loss and not just short-term weight loss.

As the practice course director for the AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop, can you tell me how this course came about? What does the workshop cover?

This workshop is a brainchild of AGA. This will be the third year of having these workshops. It’s been divided into regional workshops, so more people can attend. But it arose from the recognition that there is a need to have a support system, a forum where discussions on navigating career and life transitions with grace can happen, and more resources for success can be provided.

There is so much power in learning from shared experiences. And I think that was huge, to realize that we are not alone. We can celebrate our achievements together and acknowledge our challenges together, and then come together to brainstorm and innovate to solve problems and advocate for health equity.

You’ve been involved with community, non-profit organizations like the Homeless Alliance in Oklahoma City. How has this work enriched your life outside of medicine?

I feel like we sometimes get tunnel vision, talking to people in the same line of work. It was extremely important for me to broaden my horizons by learning from people outside of the medical community and from organizations like Homeless Alliance, which allowed me a platform to understand what my community needs. It’s an incredible organization that helps provide shelter not only for human beings, but also pets. The freezing temperatures over the last few months provided unique challenges like overflow in homeless shelters. I’ve learned so many things, such as how to ask for grants and how to allocate those funds. It has been absolutely enriching to me to learn about my community needs and see what an amazing difference people in the community are making.

Pooja Singhal, MD, AGAF, will never forget the time a female patient came in for gastroesophageal reflux disease and dysphagia treatment, revealing that she had already gone through multiple gastroenterologists to help diagnose and treat her ailments.

“We spent a whole visit talking about it,” said Dr. Singhal, a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, and obesity medicine specialist at Oklahoma Gastro Health and Wellness in Oklahoma City. During the exam, she discovered that her middle-aged patient was wearing an adult diaper for diarrhea and leakage.

Previous GI doctors told the patient they couldn’t help her and that she had to live with these symptoms. “I was just so shocked. I told her: This is not normal. Let’s talk more about it. Let’s figure out how we can manage it,” said Dr. Singhal, who has spent her career advocating for more education about GI conditions.

There are real barriers to patients opening up and sharing their symptoms, especially if they’re female. while ensuring that the correct knowledge gets across to the public, said Dr. Singhal.

An alumna of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program, Dr. Singhal has served as the private practice course director for AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop. She is a also a four-time recipient of the SCOPY award for her work in raising community awareness of colorectal cancer prevention in Oklahoma. In an interview, she discussed the critical role women GI doctors play in assisting the unique needs of female patients, and why it takes a village of doctors to treat the complexities of GI disorders.

Why did you choose GI, and more specifically, what brought about your interest in women’s GI issues?

GI is simply the best field. While I was doing my rotation in GI as a resident, I was enthralled and humbled that the field of gastroenterology offered an opportunity to prevent cancer. Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer related deaths, and when I realized that we could do these micro-interventions during a procedure to remove polyps that could potentially turn into cancer — or give us an opportunity to remove carcinoma in situ — that’s what really inspired me and piqued my interest in GI. As I continued to learn and explore GI more, I appreciated the opportunity the field gave us in terms of using both sides of our brains equally, the right side and the left side.

I love the diagnostic part of medicine. You have this privilege to be able to diagnose so many different diseases and perform procedures using technical skills, exploring everything from the esophagus, liver, pancreas, small bowel, and colon.

But what I really appreciate about gastroenterology is how it’s piqued my interest in women’s digestive health. How it became very close to my heart is really from my patients. I’ve learned a lot from my patients throughout the years. When I was much younger, I don’t know if I really appreciated the vulnerability it takes as a woman to go to a physician and talk about hemorrhoids and diarrhea.

One of the comments I often receive is: ‘Oh, thank God you’re a female GI. I can be myself. I can share something personal and you would understand.’

Your practice places a specific emphasis on health and wellness. Can you provide some examples of how you incorporate wellness into treatment?

I feel like wellness is very commonplace now. To me, the definition of wellness is about practicing healthy habits to attain your maximum potential, both physically and mentally — to feel the best you can. My practice specifically tries to achieve that goal by placing a strong emphasis on education and communication. We provide journals where patients can keep track of their symptoms. We encourage a lot of discussion during visits, where we talk about GI diseases and how to prevent them, or to prevent them from happening again. If you’re going to do a hemorrhoid treatment that offers hemorrhoid banding, we talk about it in detail with the patient; we don’t just do the procedure.

We have a dietitian on staff for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, IBS. Some of our older patients have pelvic organ prolapse and fecal incontinence. We have a pelvic floor therapist and a urogynecologist, and we work very closely with ob-gyn teams. My practice also takes pride in communicating with primary care physicians. We’ve had patients who have had memory loss or dementia or are grieving the loss of a loved one. And we prioritize communicating and treating patients as a whole and not focusing on just their GI symptoms.

As an advocate for community education on GI disorders, where is education lacking in this field?

I think education is lacking because there is an information delivery gap. I feel the public consumes information in the form of short social media reels. The attention span is so short and any scientific information, especially around diseases, can be scary and overwhelming. Whereas I think a lot of the medical community still interacts and exchanges information in terms of journals and publications. So, we are not really trained necessarily to talk about diseases in very simple terms.

We need more advocacy efforts on Capitol Hill. AGA has been good about doing advocacy work. I had an opportunity to go to Capitol Hill a couple of times and really advocate for policy around obesity medicine coverage and procedure coverage. I was fortunate to learn so much about healthcare policy, but it also made me appreciate that there are a lot of gaps in terms of understanding common medical diseases.

You’re trained in the Orbera Intragastric balloon system for weight reduction. How does this procedure differentiate from other bariatric procedures?

Intragastric balloon is Food and Drug Administration approved for weight loss. It’s a temporary medical device, so it’s reversible. No. 2, it’s a nonsurgical intervention, so it’s usually done in an outpatient setting. We basically place a deflated gastric balloon endoscopically, similar to an upper endoscopy method. We take a pin endoscope, a deflated balloon, which is made of medical-grade material, and we inflate it with adequate fluid. The concept is when the balloon is inflated, it provides satiety. It reduces the amount of space in the stomach for food. It slows down how quickly the food is going to leave. So you feel full much of the time. And it also helps decrease a hormone called ghrelin, which is responsible for hunger. It can make a big difference when people are gaining weight and in that category of overweight before they progress to obese.

As I tell everybody, obesity is a chronic lifelong disease that is very complex and requires lifelong efforts. So, it’s truly a journey. What’s made this procedure a success is follow-up and the continued efforts of dietitians and counseling and incorporating physical exercise, because maintenance of that weight loss is also very important. Our goal is always sustained weight loss and not just short-term weight loss.

As the practice course director for the AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop, can you tell me how this course came about? What does the workshop cover?

This workshop is a brainchild of AGA. This will be the third year of having these workshops. It’s been divided into regional workshops, so more people can attend. But it arose from the recognition that there is a need to have a support system, a forum where discussions on navigating career and life transitions with grace can happen, and more resources for success can be provided.

There is so much power in learning from shared experiences. And I think that was huge, to realize that we are not alone. We can celebrate our achievements together and acknowledge our challenges together, and then come together to brainstorm and innovate to solve problems and advocate for health equity.

You’ve been involved with community, non-profit organizations like the Homeless Alliance in Oklahoma City. How has this work enriched your life outside of medicine?

I feel like we sometimes get tunnel vision, talking to people in the same line of work. It was extremely important for me to broaden my horizons by learning from people outside of the medical community and from organizations like Homeless Alliance, which allowed me a platform to understand what my community needs. It’s an incredible organization that helps provide shelter not only for human beings, but also pets. The freezing temperatures over the last few months provided unique challenges like overflow in homeless shelters. I’ve learned so many things, such as how to ask for grants and how to allocate those funds. It has been absolutely enriching to me to learn about my community needs and see what an amazing difference people in the community are making.

Pooja Singhal, MD, AGAF, will never forget the time a female patient came in for gastroesophageal reflux disease and dysphagia treatment, revealing that she had already gone through multiple gastroenterologists to help diagnose and treat her ailments.

“We spent a whole visit talking about it,” said Dr. Singhal, a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, and obesity medicine specialist at Oklahoma Gastro Health and Wellness in Oklahoma City. During the exam, she discovered that her middle-aged patient was wearing an adult diaper for diarrhea and leakage.

Previous GI doctors told the patient they couldn’t help her and that she had to live with these symptoms. “I was just so shocked. I told her: This is not normal. Let’s talk more about it. Let’s figure out how we can manage it,” said Dr. Singhal, who has spent her career advocating for more education about GI conditions.

There are real barriers to patients opening up and sharing their symptoms, especially if they’re female. while ensuring that the correct knowledge gets across to the public, said Dr. Singhal.

An alumna of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program, Dr. Singhal has served as the private practice course director for AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop. She is a also a four-time recipient of the SCOPY award for her work in raising community awareness of colorectal cancer prevention in Oklahoma. In an interview, she discussed the critical role women GI doctors play in assisting the unique needs of female patients, and why it takes a village of doctors to treat the complexities of GI disorders.

Why did you choose GI, and more specifically, what brought about your interest in women’s GI issues?

GI is simply the best field. While I was doing my rotation in GI as a resident, I was enthralled and humbled that the field of gastroenterology offered an opportunity to prevent cancer. Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer related deaths, and when I realized that we could do these micro-interventions during a procedure to remove polyps that could potentially turn into cancer — or give us an opportunity to remove carcinoma in situ — that’s what really inspired me and piqued my interest in GI. As I continued to learn and explore GI more, I appreciated the opportunity the field gave us in terms of using both sides of our brains equally, the right side and the left side.

I love the diagnostic part of medicine. You have this privilege to be able to diagnose so many different diseases and perform procedures using technical skills, exploring everything from the esophagus, liver, pancreas, small bowel, and colon.

But what I really appreciate about gastroenterology is how it’s piqued my interest in women’s digestive health. How it became very close to my heart is really from my patients. I’ve learned a lot from my patients throughout the years. When I was much younger, I don’t know if I really appreciated the vulnerability it takes as a woman to go to a physician and talk about hemorrhoids and diarrhea.

One of the comments I often receive is: ‘Oh, thank God you’re a female GI. I can be myself. I can share something personal and you would understand.’

Your practice places a specific emphasis on health and wellness. Can you provide some examples of how you incorporate wellness into treatment?

I feel like wellness is very commonplace now. To me, the definition of wellness is about practicing healthy habits to attain your maximum potential, both physically and mentally — to feel the best you can. My practice specifically tries to achieve that goal by placing a strong emphasis on education and communication. We provide journals where patients can keep track of their symptoms. We encourage a lot of discussion during visits, where we talk about GI diseases and how to prevent them, or to prevent them from happening again. If you’re going to do a hemorrhoid treatment that offers hemorrhoid banding, we talk about it in detail with the patient; we don’t just do the procedure.

We have a dietitian on staff for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, IBS. Some of our older patients have pelvic organ prolapse and fecal incontinence. We have a pelvic floor therapist and a urogynecologist, and we work very closely with ob-gyn teams. My practice also takes pride in communicating with primary care physicians. We’ve had patients who have had memory loss or dementia or are grieving the loss of a loved one. And we prioritize communicating and treating patients as a whole and not focusing on just their GI symptoms.

As an advocate for community education on GI disorders, where is education lacking in this field?

I think education is lacking because there is an information delivery gap. I feel the public consumes information in the form of short social media reels. The attention span is so short and any scientific information, especially around diseases, can be scary and overwhelming. Whereas I think a lot of the medical community still interacts and exchanges information in terms of journals and publications. So, we are not really trained necessarily to talk about diseases in very simple terms.

We need more advocacy efforts on Capitol Hill. AGA has been good about doing advocacy work. I had an opportunity to go to Capitol Hill a couple of times and really advocate for policy around obesity medicine coverage and procedure coverage. I was fortunate to learn so much about healthcare policy, but it also made me appreciate that there are a lot of gaps in terms of understanding common medical diseases.

You’re trained in the Orbera Intragastric balloon system for weight reduction. How does this procedure differentiate from other bariatric procedures?

Intragastric balloon is Food and Drug Administration approved for weight loss. It’s a temporary medical device, so it’s reversible. No. 2, it’s a nonsurgical intervention, so it’s usually done in an outpatient setting. We basically place a deflated gastric balloon endoscopically, similar to an upper endoscopy method. We take a pin endoscope, a deflated balloon, which is made of medical-grade material, and we inflate it with adequate fluid. The concept is when the balloon is inflated, it provides satiety. It reduces the amount of space in the stomach for food. It slows down how quickly the food is going to leave. So you feel full much of the time. And it also helps decrease a hormone called ghrelin, which is responsible for hunger. It can make a big difference when people are gaining weight and in that category of overweight before they progress to obese.

As I tell everybody, obesity is a chronic lifelong disease that is very complex and requires lifelong efforts. So, it’s truly a journey. What’s made this procedure a success is follow-up and the continued efforts of dietitians and counseling and incorporating physical exercise, because maintenance of that weight loss is also very important. Our goal is always sustained weight loss and not just short-term weight loss.

As the practice course director for the AGA’s Midwest Women in GI Workshop, can you tell me how this course came about? What does the workshop cover?

This workshop is a brainchild of AGA. This will be the third year of having these workshops. It’s been divided into regional workshops, so more people can attend. But it arose from the recognition that there is a need to have a support system, a forum where discussions on navigating career and life transitions with grace can happen, and more resources for success can be provided.

There is so much power in learning from shared experiences. And I think that was huge, to realize that we are not alone. We can celebrate our achievements together and acknowledge our challenges together, and then come together to brainstorm and innovate to solve problems and advocate for health equity.

You’ve been involved with community, non-profit organizations like the Homeless Alliance in Oklahoma City. How has this work enriched your life outside of medicine?

I feel like we sometimes get tunnel vision, talking to people in the same line of work. It was extremely important for me to broaden my horizons by learning from people outside of the medical community and from organizations like Homeless Alliance, which allowed me a platform to understand what my community needs. It’s an incredible organization that helps provide shelter not only for human beings, but also pets. The freezing temperatures over the last few months provided unique challenges like overflow in homeless shelters. I’ve learned so many things, such as how to ask for grants and how to allocate those funds. It has been absolutely enriching to me to learn about my community needs and see what an amazing difference people in the community are making.

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

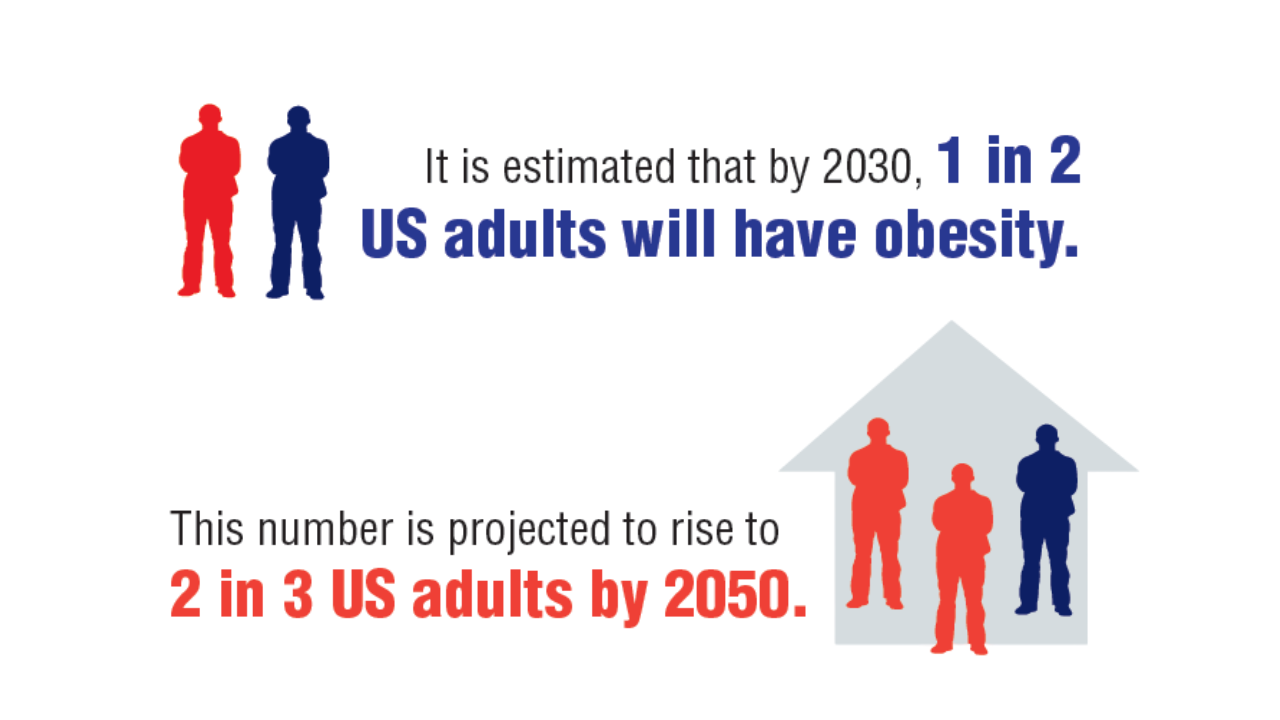

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

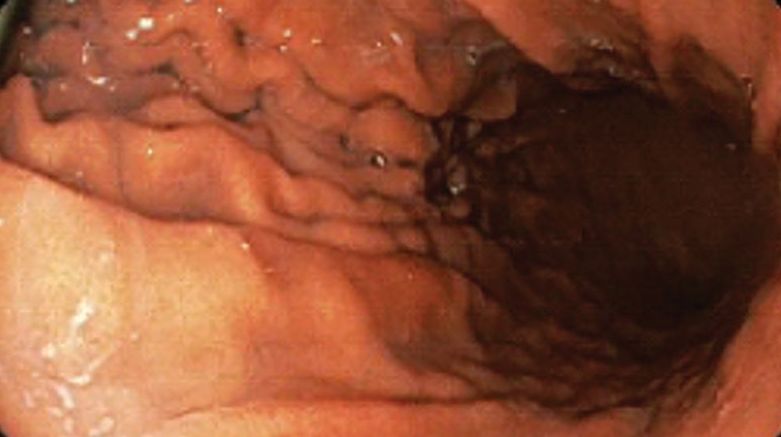

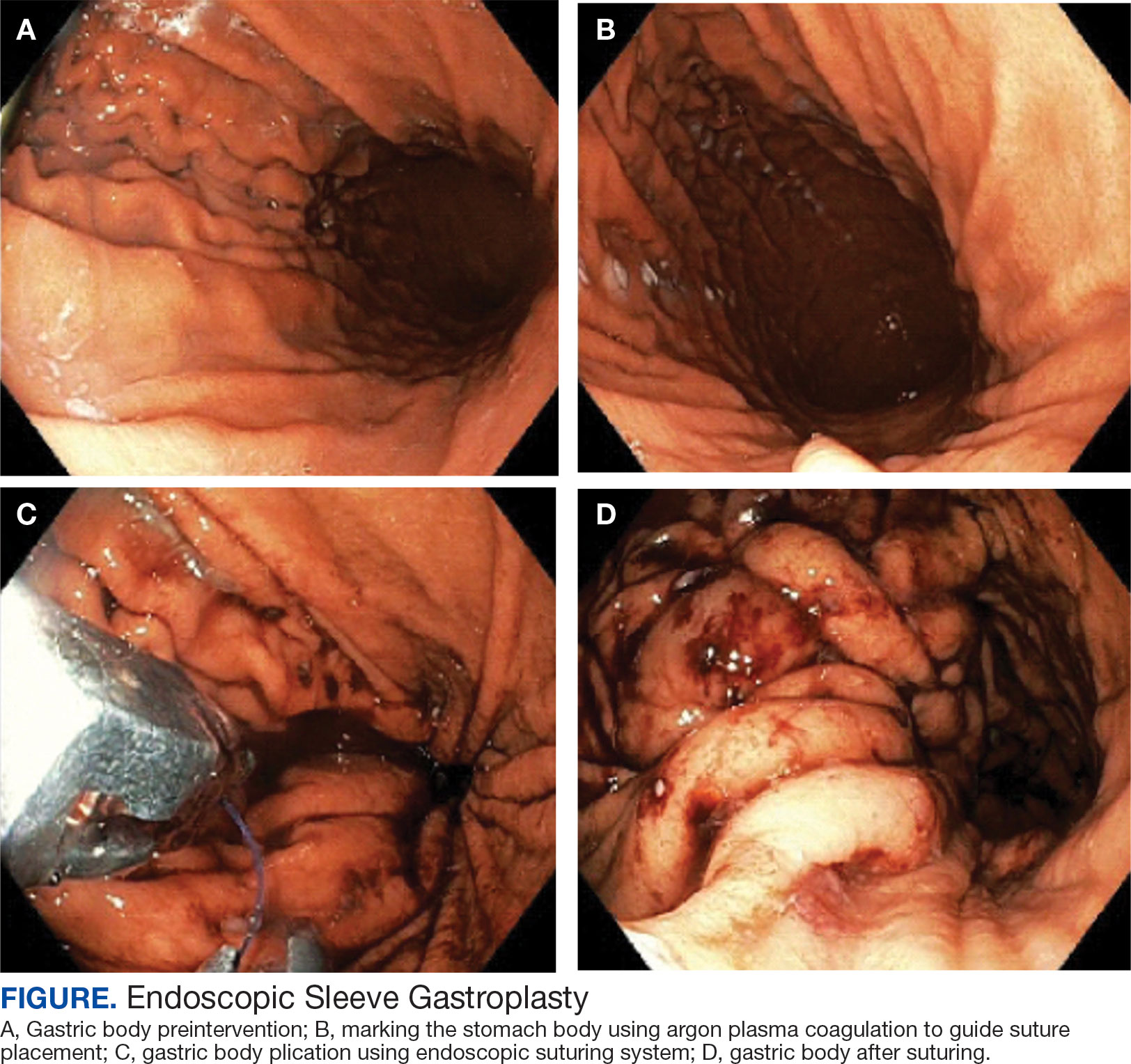

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

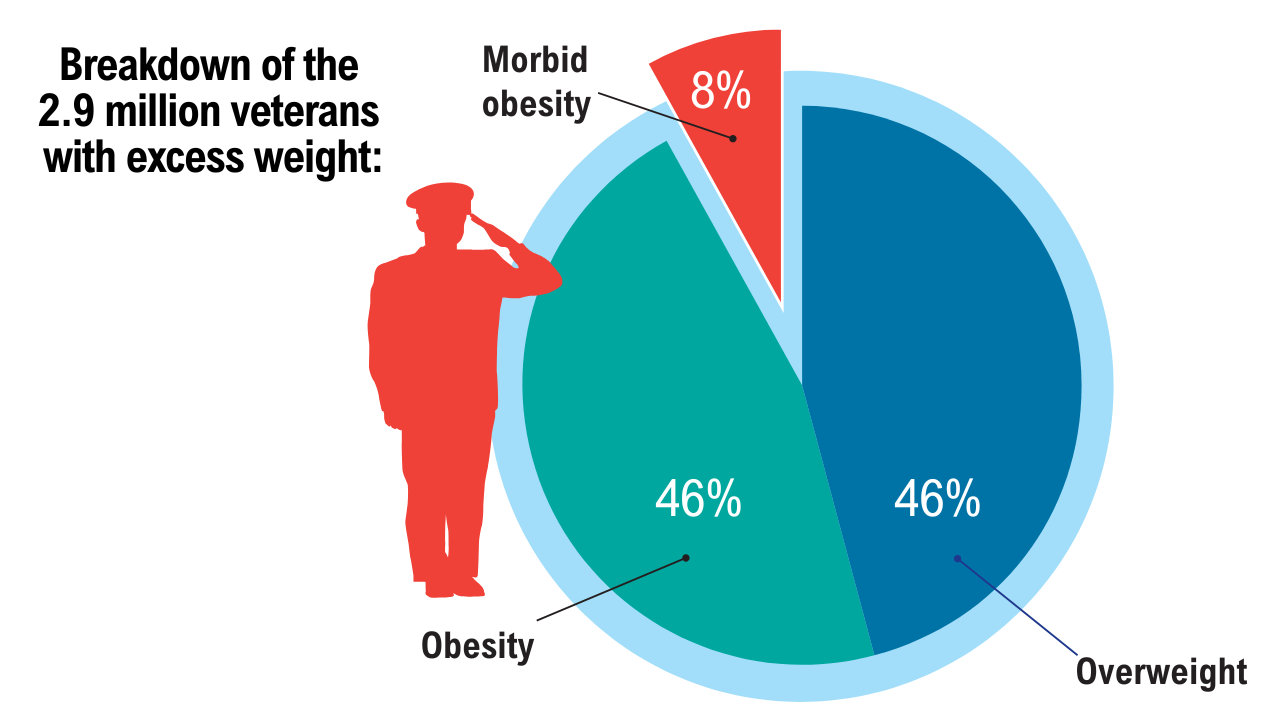

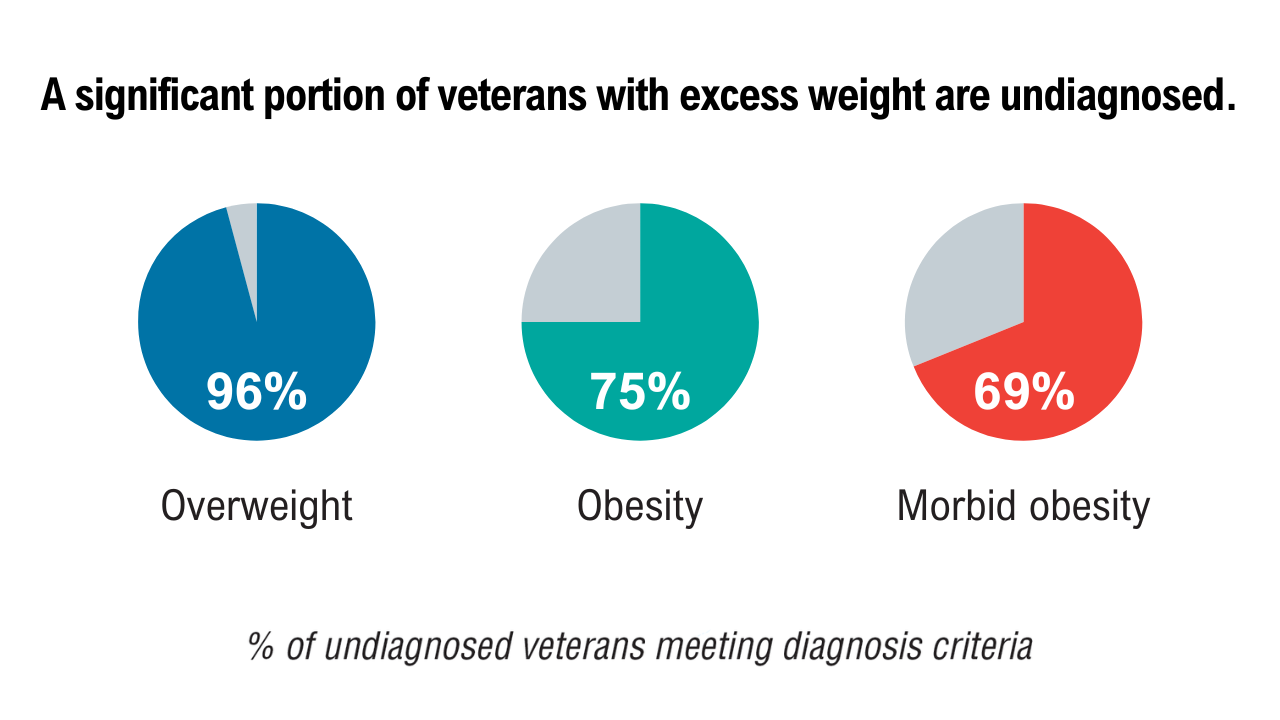

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

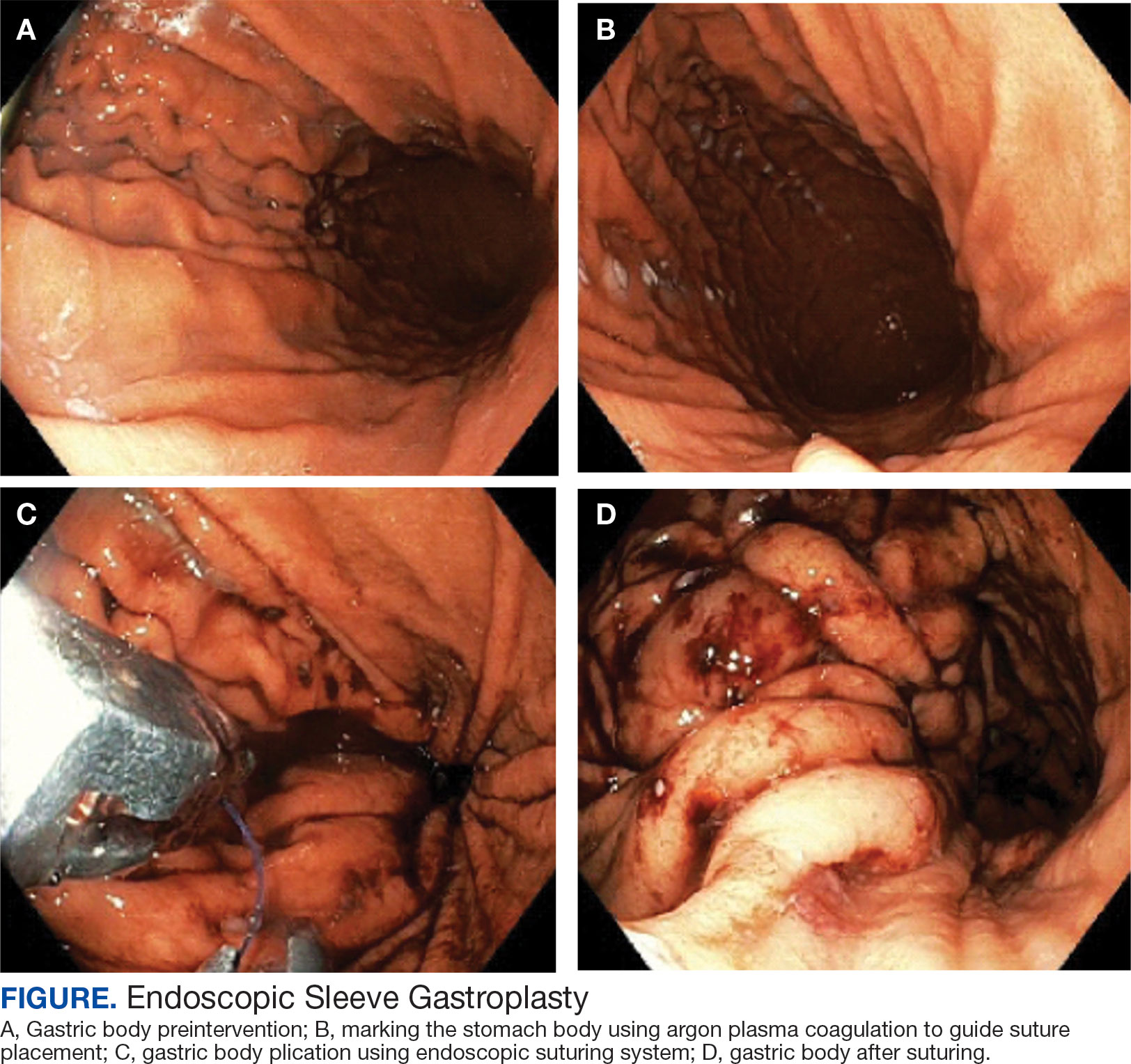

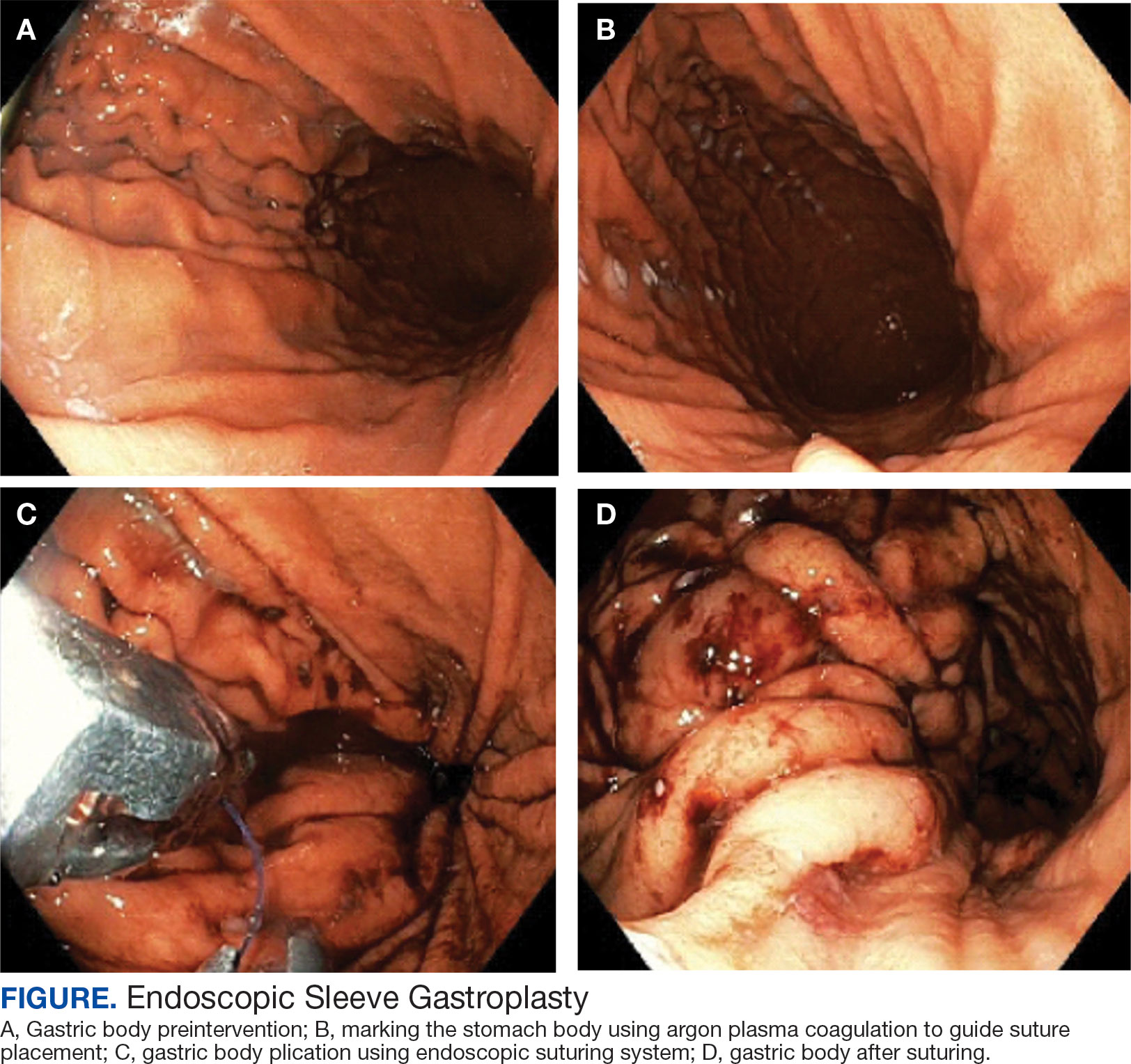

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

GLP-1 Use After Bariatric Surgery on the Rise

, a large retrospective cohort study showed.

GLP-1 initiation was also more common among women, those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy, and those with lower postoperative weight loss as measured by BMI.

“Some patients do not lose as much weight as expected, or they regain weight after a few years. In such cases, GLP-1 therapies are emerging as an important option for weight management,” said principal investigator Hemalkumar Mehta, PhD, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

“We also noted many personal stories circulating on social media in which patients shared their experiences using GLP-1 after bariatric surgery,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

But when the researchers reviewed the scientific literature, they found no published evidence on GLP-1 use in this setting and little or no data on outcomes with the newer drugs such as semaglutide and tirzepatide. “This gap motivated us to conduct the current study,” said Mehta. The study was published in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers analyzed data from a national multicenter database of electronic health records of approximately 113 million US adults to characterize the use of and factors associated with GLP-1 initiation after bariatric surgery.

Among 112,858 individuals undergoing bariatric surgery during the study period, the mean age was 45.2 years, and 78.9% were women.

By self-report race, 1.1% were Asian, 22.1% were Black or African American, 64.2% were White individuals, and 12.6% reported belonging to other races (American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or unknown).

A total of 15,749 individuals (14%) initiated GLP-1s post-surgery, with 3391 (21.5%) beginning within 2 years of surgery and the remainder initiating during postsurgical years 3-4 (32.3%), 5-6 (25.2%), or later (21%).

Notably, the proportion of GLP-1 use increased more in the more recent cohort, from 1.7% in the January 2015-December 2019 cohort to 12.6% from June 2020 to May 2025.

Differences Between Users and Nonusers

Those who initiated GLP-1s differed significantly from those who did not: GLP-1 users vs nonusers were younger (mean age, 44.9 years vs 45.2 years), and use was more common among women vs men (15.1% vs 9.7%), among Black or African American vs White patients (15.8% vs 13.5%), and among those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (14.9% vs 12.1%).

Looked at another way, women (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.61), those undergoing sleeve gastrectomy (aHR, 1.42), and those with type 2 diabetes (aHR, 1.34) were more likely to initiate GLP-1s than their counterparts.

The overall median presurgical BMI was 42. On analyzing obesity classification based on BMI, the researchers found that the chances of GLP-1 use were 1.73 times higher among class 1 obesity patients (BMI, 30.0-34.9), 2.19 times higher among class 2 obesity patients (BMI, 35.0-39.9), and 2.69 times higher among patients with class 3 obesity (BMI ≥ 40) than among overweight patients (BMI, 25.0-29.9).

The median post-surgery BMI for GLP-1 users at drug initiation was 36.7. Each one-unit increase in postsurgical BMI was associated with an 8% increase in the likelihood of GLP-1 initiation (aHR, 1.08).

“Importantly, our study did not specifically evaluate the effectiveness of GLP-1 therapy on weight loss after surgery,” Mehta noted. That issue and others, such as optimal timing for initiating GLP-1s, are currently under investigation.

In a related editorial, Kate Lauer, MD, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and colleagues noted that the study had several limitations. It relied on data prior to the USFDA approvals of semaglutide and tirzepatide, the two most prescribed GLP-1s currently, potentially limiting its applicability to current practice.

Furthermore, the prescribing data did not capture dose, titration schedules, or adherence, which are “critical for understanding treatment efficacy,” they wrote. “Nonetheless, the findings highlight two important trends: (1) GLP-1s are being increasingly used as an adjunct after bariatric surgery, and (2) there is substantial variability in the timing of their initiation.”

‘Logical’ to Use GLP-1s Post Surgery

Commenting on the study findings for GI & Hepatology News, Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, who was not involved in the study, said, “I think it is perfectly logical to use GLP-1s in patients who have had bariatric surgery.”

In this study, weight loss in those who took GLP-1s was about 12% (from a median BMI of 42 pre-surgery to 36.7 when a GLP-1 was initiated), which is significantly less than average, Aronne noted. “The patients still had Class 2 obesity.”

“Obesity is the same as other metabolic diseases,” he added. “We have to use common sense and good medical judgment when treating patients. If surgery isn’t completely effective and weight loss is inadequate, I would recommend medications.”

Of note, his team has found that lower doses of GLP-1s are required in those who have had surgery than in those who have not. “My opinion is that patients who have undergone bariatric surgery seem to be more sensitive to the medications than the average patient, but this hasn’t been carefully studied.”

To prepare patients for the possible use of GLP1s post-surgery, he suggested telling those with very high BMI that “they may need medication in addition to the procedure in order to get the best result.”

Mehta added, “Ultimately, the decision to start GLP-1s after surgery is shared between patients and clinicians. Given the amount of media coverage on GLP-1 therapies, it is not surprising that more patients are initiating these discussions with their doctors.”

Mehta is supported by the US National Institute on Aging and reported receiving grants from the institute for this study; no other funding was reported. Lauer reported receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large retrospective cohort study showed.

GLP-1 initiation was also more common among women, those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy, and those with lower postoperative weight loss as measured by BMI.

“Some patients do not lose as much weight as expected, or they regain weight after a few years. In such cases, GLP-1 therapies are emerging as an important option for weight management,” said principal investigator Hemalkumar Mehta, PhD, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

“We also noted many personal stories circulating on social media in which patients shared their experiences using GLP-1 after bariatric surgery,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

But when the researchers reviewed the scientific literature, they found no published evidence on GLP-1 use in this setting and little or no data on outcomes with the newer drugs such as semaglutide and tirzepatide. “This gap motivated us to conduct the current study,” said Mehta. The study was published in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers analyzed data from a national multicenter database of electronic health records of approximately 113 million US adults to characterize the use of and factors associated with GLP-1 initiation after bariatric surgery.

Among 112,858 individuals undergoing bariatric surgery during the study period, the mean age was 45.2 years, and 78.9% were women.

By self-report race, 1.1% were Asian, 22.1% were Black or African American, 64.2% were White individuals, and 12.6% reported belonging to other races (American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or unknown).

A total of 15,749 individuals (14%) initiated GLP-1s post-surgery, with 3391 (21.5%) beginning within 2 years of surgery and the remainder initiating during postsurgical years 3-4 (32.3%), 5-6 (25.2%), or later (21%).

Notably, the proportion of GLP-1 use increased more in the more recent cohort, from 1.7% in the January 2015-December 2019 cohort to 12.6% from June 2020 to May 2025.

Differences Between Users and Nonusers

Those who initiated GLP-1s differed significantly from those who did not: GLP-1 users vs nonusers were younger (mean age, 44.9 years vs 45.2 years), and use was more common among women vs men (15.1% vs 9.7%), among Black or African American vs White patients (15.8% vs 13.5%), and among those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (14.9% vs 12.1%).

Looked at another way, women (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.61), those undergoing sleeve gastrectomy (aHR, 1.42), and those with type 2 diabetes (aHR, 1.34) were more likely to initiate GLP-1s than their counterparts.

The overall median presurgical BMI was 42. On analyzing obesity classification based on BMI, the researchers found that the chances of GLP-1 use were 1.73 times higher among class 1 obesity patients (BMI, 30.0-34.9), 2.19 times higher among class 2 obesity patients (BMI, 35.0-39.9), and 2.69 times higher among patients with class 3 obesity (BMI ≥ 40) than among overweight patients (BMI, 25.0-29.9).

The median post-surgery BMI for GLP-1 users at drug initiation was 36.7. Each one-unit increase in postsurgical BMI was associated with an 8% increase in the likelihood of GLP-1 initiation (aHR, 1.08).

“Importantly, our study did not specifically evaluate the effectiveness of GLP-1 therapy on weight loss after surgery,” Mehta noted. That issue and others, such as optimal timing for initiating GLP-1s, are currently under investigation.

In a related editorial, Kate Lauer, MD, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and colleagues noted that the study had several limitations. It relied on data prior to the USFDA approvals of semaglutide and tirzepatide, the two most prescribed GLP-1s currently, potentially limiting its applicability to current practice.

Furthermore, the prescribing data did not capture dose, titration schedules, or adherence, which are “critical for understanding treatment efficacy,” they wrote. “Nonetheless, the findings highlight two important trends: (1) GLP-1s are being increasingly used as an adjunct after bariatric surgery, and (2) there is substantial variability in the timing of their initiation.”

‘Logical’ to Use GLP-1s Post Surgery

Commenting on the study findings for GI & Hepatology News, Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, who was not involved in the study, said, “I think it is perfectly logical to use GLP-1s in patients who have had bariatric surgery.”

In this study, weight loss in those who took GLP-1s was about 12% (from a median BMI of 42 pre-surgery to 36.7 when a GLP-1 was initiated), which is significantly less than average, Aronne noted. “The patients still had Class 2 obesity.”

“Obesity is the same as other metabolic diseases,” he added. “We have to use common sense and good medical judgment when treating patients. If surgery isn’t completely effective and weight loss is inadequate, I would recommend medications.”

Of note, his team has found that lower doses of GLP-1s are required in those who have had surgery than in those who have not. “My opinion is that patients who have undergone bariatric surgery seem to be more sensitive to the medications than the average patient, but this hasn’t been carefully studied.”

To prepare patients for the possible use of GLP1s post-surgery, he suggested telling those with very high BMI that “they may need medication in addition to the procedure in order to get the best result.”

Mehta added, “Ultimately, the decision to start GLP-1s after surgery is shared between patients and clinicians. Given the amount of media coverage on GLP-1 therapies, it is not surprising that more patients are initiating these discussions with their doctors.”

Mehta is supported by the US National Institute on Aging and reported receiving grants from the institute for this study; no other funding was reported. Lauer reported receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large retrospective cohort study showed.

GLP-1 initiation was also more common among women, those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy, and those with lower postoperative weight loss as measured by BMI.

“Some patients do not lose as much weight as expected, or they regain weight after a few years. In such cases, GLP-1 therapies are emerging as an important option for weight management,” said principal investigator Hemalkumar Mehta, PhD, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

“We also noted many personal stories circulating on social media in which patients shared their experiences using GLP-1 after bariatric surgery,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

But when the researchers reviewed the scientific literature, they found no published evidence on GLP-1 use in this setting and little or no data on outcomes with the newer drugs such as semaglutide and tirzepatide. “This gap motivated us to conduct the current study,” said Mehta. The study was published in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers analyzed data from a national multicenter database of electronic health records of approximately 113 million US adults to characterize the use of and factors associated with GLP-1 initiation after bariatric surgery.

Among 112,858 individuals undergoing bariatric surgery during the study period, the mean age was 45.2 years, and 78.9% were women.

By self-report race, 1.1% were Asian, 22.1% were Black or African American, 64.2% were White individuals, and 12.6% reported belonging to other races (American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or unknown).

A total of 15,749 individuals (14%) initiated GLP-1s post-surgery, with 3391 (21.5%) beginning within 2 years of surgery and the remainder initiating during postsurgical years 3-4 (32.3%), 5-6 (25.2%), or later (21%).

Notably, the proportion of GLP-1 use increased more in the more recent cohort, from 1.7% in the January 2015-December 2019 cohort to 12.6% from June 2020 to May 2025.

Differences Between Users and Nonusers

Those who initiated GLP-1s differed significantly from those who did not: GLP-1 users vs nonusers were younger (mean age, 44.9 years vs 45.2 years), and use was more common among women vs men (15.1% vs 9.7%), among Black or African American vs White patients (15.8% vs 13.5%), and among those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (14.9% vs 12.1%).