User login

Celiac disease appears to double COVID-19 hospitalization risk

, a single-center U.S. study shows.

Vaccination against COVID-19 reduced the risk for hospitalization by almost half for both groups, however, the study finds.

“To our knowledge this is the first study that demonstrated a vaccination effect on mitigation of the risk of hospitalization in celiac disease patients with COVID-19 infection,” write Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, director, Celiac Disease Program, Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and colleagues.

Despite the increased risk for hospitalization among patients with celiac disease, there were no significant differences between those with and without the condition with respect to intensive care unit requirement, mortality, or thrombosis, the researchers found.

The findings suggest that celiac disease patients with COVID-19 are “not inherently at greater risk for more severe outcomes,” they wrote.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Comparing outcomes

Although it has been shown that patients with celiac disease have increased susceptibility to viral illnesses, research to date has found similar COVID-19 incidence and outcomes, including hospitalization, between patients with celiac disease and the general population, the researchers wrote.

However, the impact of COVID-19 vaccination is less clear, so the researchers set out to compare the frequency of COVID-19–related outcomes between patients with and without celiac disease before and after vaccination.

Through an analysis of patient medical records, researchers found 171,763 patients diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 at their institution between March 1, 2020, and Jan 1, 2022. Of them, 110 adults had biopsy-proven celiac disease.

The median time from biopsy diagnosis of celiac disease to COVID-19 was 217 months, 66.3% of patients were documented to be following a gluten-free diet, and tissue transglutaminase IgA was positive in 46.2% at the time of COVID-19.

The celiac group was matched by age, ethnicity, sex, and date of COVID-19 diagnosis with a control group of 220 adults without a clinical diagnosis of celiac disease. The two cohorts had similar rates of comorbid obesity, type 2 diabetes, preexisting lung disease, and tobacco use.

Patients with celiac disease were significantly more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than were the control participants, at 24% vs. 11% (hazard ratio, 2.1; P = .009), the researchers wrote.

However, hospitalized patients with celiac disease were less likely to require supplementary oxygen than were the control participants, at 63% vs. 84%.

Vaccination rates for COVID-19 were similar between the two groups, at 64.5% among patients with celiac disease and 70% in the control group. Vaccination was associated with a lower risk for hospitalization on multivariate analysis (HR, 0.53; P = .026).

There was no significant difference in hospitalization rates between vaccinated patients with celiac disease and vaccinated patients in the control group (odds ratio, 1.12; P = .79), the team reported.

The secondary outcomes of ICU requirement, mortality, and thrombosis were minimal in both groups, the researchers wrote.

Vaccination’s importance

The different findings regarding hospitalization risk among patients with celiac disease between this study and previous research are likely due to earlier studies not accounting for vaccination status, the researchers wrote.

“This study shows significantly different rates of hospitalization among patients with [celiac disease] depending on their vaccination status, with strong evidence for mitigation of hospitalization risk through vaccination,” they added.

“Vaccination against COVID-19 should be strongly recommended in patients with celiac disease,” the researchers concluded.

No funding was declared. Dr. Rubio-Tapia reported a relationship with Takeda. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a single-center U.S. study shows.

Vaccination against COVID-19 reduced the risk for hospitalization by almost half for both groups, however, the study finds.

“To our knowledge this is the first study that demonstrated a vaccination effect on mitigation of the risk of hospitalization in celiac disease patients with COVID-19 infection,” write Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, director, Celiac Disease Program, Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and colleagues.

Despite the increased risk for hospitalization among patients with celiac disease, there were no significant differences between those with and without the condition with respect to intensive care unit requirement, mortality, or thrombosis, the researchers found.

The findings suggest that celiac disease patients with COVID-19 are “not inherently at greater risk for more severe outcomes,” they wrote.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Comparing outcomes

Although it has been shown that patients with celiac disease have increased susceptibility to viral illnesses, research to date has found similar COVID-19 incidence and outcomes, including hospitalization, between patients with celiac disease and the general population, the researchers wrote.

However, the impact of COVID-19 vaccination is less clear, so the researchers set out to compare the frequency of COVID-19–related outcomes between patients with and without celiac disease before and after vaccination.

Through an analysis of patient medical records, researchers found 171,763 patients diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 at their institution between March 1, 2020, and Jan 1, 2022. Of them, 110 adults had biopsy-proven celiac disease.

The median time from biopsy diagnosis of celiac disease to COVID-19 was 217 months, 66.3% of patients were documented to be following a gluten-free diet, and tissue transglutaminase IgA was positive in 46.2% at the time of COVID-19.

The celiac group was matched by age, ethnicity, sex, and date of COVID-19 diagnosis with a control group of 220 adults without a clinical diagnosis of celiac disease. The two cohorts had similar rates of comorbid obesity, type 2 diabetes, preexisting lung disease, and tobacco use.

Patients with celiac disease were significantly more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than were the control participants, at 24% vs. 11% (hazard ratio, 2.1; P = .009), the researchers wrote.

However, hospitalized patients with celiac disease were less likely to require supplementary oxygen than were the control participants, at 63% vs. 84%.

Vaccination rates for COVID-19 were similar between the two groups, at 64.5% among patients with celiac disease and 70% in the control group. Vaccination was associated with a lower risk for hospitalization on multivariate analysis (HR, 0.53; P = .026).

There was no significant difference in hospitalization rates between vaccinated patients with celiac disease and vaccinated patients in the control group (odds ratio, 1.12; P = .79), the team reported.

The secondary outcomes of ICU requirement, mortality, and thrombosis were minimal in both groups, the researchers wrote.

Vaccination’s importance

The different findings regarding hospitalization risk among patients with celiac disease between this study and previous research are likely due to earlier studies not accounting for vaccination status, the researchers wrote.

“This study shows significantly different rates of hospitalization among patients with [celiac disease] depending on their vaccination status, with strong evidence for mitigation of hospitalization risk through vaccination,” they added.

“Vaccination against COVID-19 should be strongly recommended in patients with celiac disease,” the researchers concluded.

No funding was declared. Dr. Rubio-Tapia reported a relationship with Takeda. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a single-center U.S. study shows.

Vaccination against COVID-19 reduced the risk for hospitalization by almost half for both groups, however, the study finds.

“To our knowledge this is the first study that demonstrated a vaccination effect on mitigation of the risk of hospitalization in celiac disease patients with COVID-19 infection,” write Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, director, Celiac Disease Program, Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and colleagues.

Despite the increased risk for hospitalization among patients with celiac disease, there were no significant differences between those with and without the condition with respect to intensive care unit requirement, mortality, or thrombosis, the researchers found.

The findings suggest that celiac disease patients with COVID-19 are “not inherently at greater risk for more severe outcomes,” they wrote.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Comparing outcomes

Although it has been shown that patients with celiac disease have increased susceptibility to viral illnesses, research to date has found similar COVID-19 incidence and outcomes, including hospitalization, between patients with celiac disease and the general population, the researchers wrote.

However, the impact of COVID-19 vaccination is less clear, so the researchers set out to compare the frequency of COVID-19–related outcomes between patients with and without celiac disease before and after vaccination.

Through an analysis of patient medical records, researchers found 171,763 patients diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 at their institution between March 1, 2020, and Jan 1, 2022. Of them, 110 adults had biopsy-proven celiac disease.

The median time from biopsy diagnosis of celiac disease to COVID-19 was 217 months, 66.3% of patients were documented to be following a gluten-free diet, and tissue transglutaminase IgA was positive in 46.2% at the time of COVID-19.

The celiac group was matched by age, ethnicity, sex, and date of COVID-19 diagnosis with a control group of 220 adults without a clinical diagnosis of celiac disease. The two cohorts had similar rates of comorbid obesity, type 2 diabetes, preexisting lung disease, and tobacco use.

Patients with celiac disease were significantly more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than were the control participants, at 24% vs. 11% (hazard ratio, 2.1; P = .009), the researchers wrote.

However, hospitalized patients with celiac disease were less likely to require supplementary oxygen than were the control participants, at 63% vs. 84%.

Vaccination rates for COVID-19 were similar between the two groups, at 64.5% among patients with celiac disease and 70% in the control group. Vaccination was associated with a lower risk for hospitalization on multivariate analysis (HR, 0.53; P = .026).

There was no significant difference in hospitalization rates between vaccinated patients with celiac disease and vaccinated patients in the control group (odds ratio, 1.12; P = .79), the team reported.

The secondary outcomes of ICU requirement, mortality, and thrombosis were minimal in both groups, the researchers wrote.

Vaccination’s importance

The different findings regarding hospitalization risk among patients with celiac disease between this study and previous research are likely due to earlier studies not accounting for vaccination status, the researchers wrote.

“This study shows significantly different rates of hospitalization among patients with [celiac disease] depending on their vaccination status, with strong evidence for mitigation of hospitalization risk through vaccination,” they added.

“Vaccination against COVID-19 should be strongly recommended in patients with celiac disease,” the researchers concluded.

No funding was declared. Dr. Rubio-Tapia reported a relationship with Takeda. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Integrating intestinal ultrasound into inflammatory bowel disease training and practice in the United States

Evolving endpoints and treat-to-target strategies in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incorporate a need for more frequent assessments of the disease, including objective measures of inflammation.1,2 Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is a noninvasive, well-tolerated,3 repeatable, point-of-care (POC) test that is highly sensitive and specific in detection of bowel inflammation, transmural healing,4,5 and response to therapy in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).6-8 As IUS is taking hold in the United States, there is a great need to teach the next generation of gastroenterologists about its value, how to incorporate it into clinical practice, and how to become appropriately trained and maintain competency.

Why incorporate IUS in the United States now?

As IBD management has evolved, so has the appreciation for the value of bedside IUS as a tool that addresses very real needs for the field. Unlike other parts of the world in which ultrasound skills are part of the training curriculum, this has not been the case in internal medicine and gastroenterology training in the United States. In addition, there have been no specific billing codes or clear renumeration processes outlined for IUS,9 nor have there been any local training opportunities. Because of these challenges, it was not until recently that several leaders in IBD in the United States championed the potential of this technology and incorporated it into IBD management. Subsequently, a number of gastroenterologists have been trained and are now leading the effort to disseminate this tool throughout the United States. A consequence of these efforts resulted in support from the Helmsley Charitable Trust (Helmsley) and the creation of the Intestinal Ultrasound Group of the United States and Canada to address the gaps unique to North America as well as to strengthen the quality of IUS research through collaborations across the continent.

What is IUS, and when is it performed?

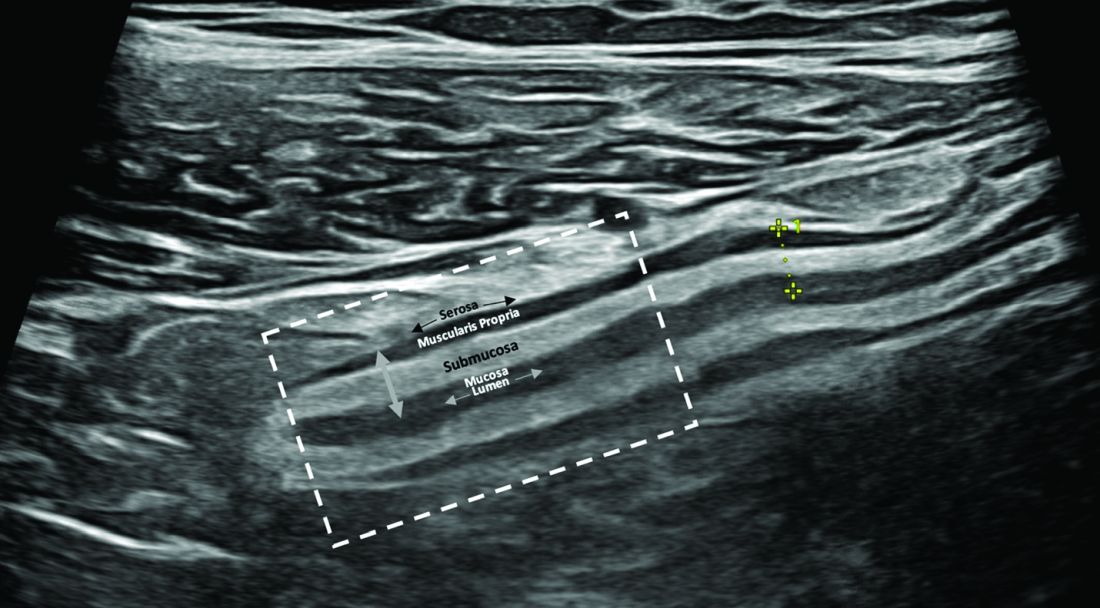

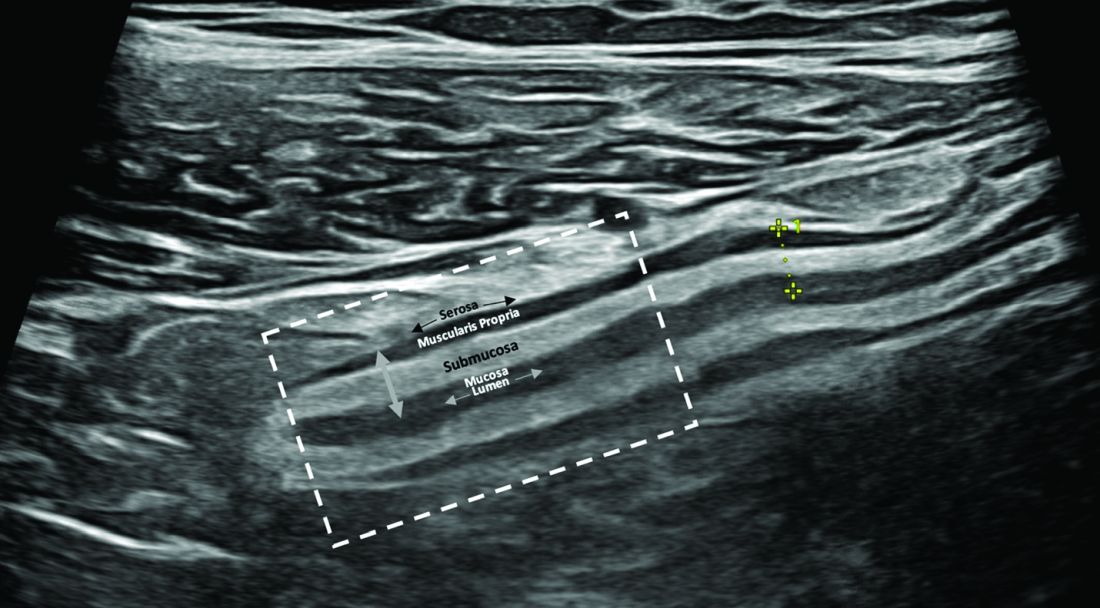

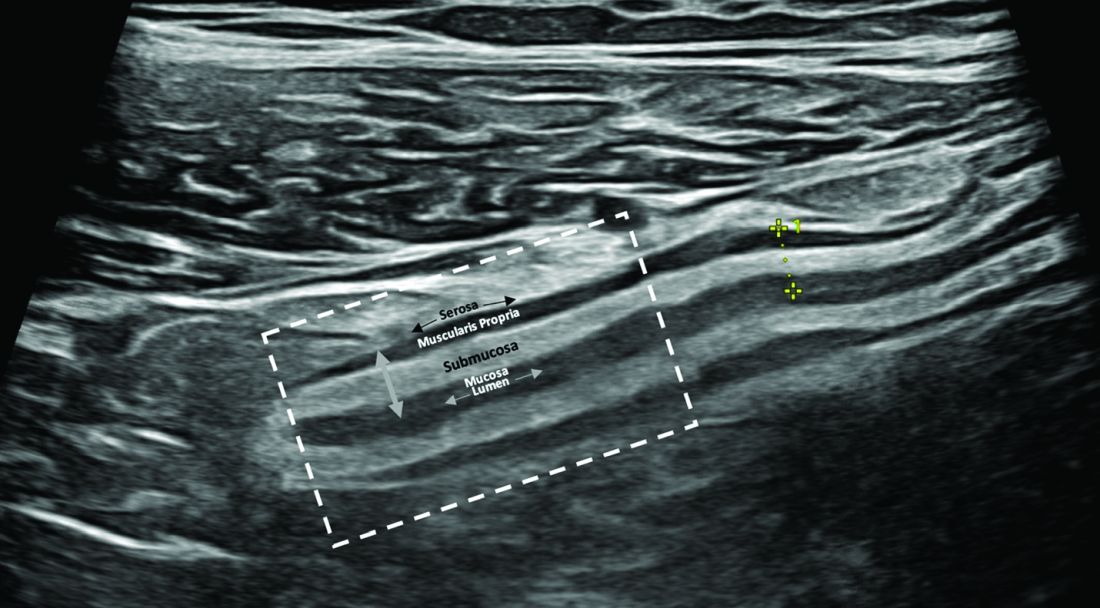

IUS is a sonographic exam performed by a gastroenterology-trained professional who scans the abdominal wall (and perineum when the rectum and perineal disease is evaluated), using both a convex low-frequency probe and linear high-frequency probe to evaluate the small intestine, colon, and rectum. The bowel is composed of five layers with alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers: the mucosal-lumen interface (not a true part of the bowel wall), deep mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. (Figure)

The most sensitive parameter for assessment of IBD activity is bowel wall thickness (≤ 3 mm in the small bowel and colon and ≤ 4 mm in the rectum are considered normal in adults).8,10 The second key parameter is the assessment of vascularization, in which presence of hyperemia suggests active disease.11 There are a number of indices to quantify hyperemia, with the most widely used being the Limberg score.12 Additional parameters include assessment of loss of the delineation of the bowel wall layers (loss of stratification signifies active inflammation), increased thickness of the submucosa,13 increased mesenteric fatty proliferation (with increased inflammation, mesenteric fat proliferation will appear as a hyperechoic area surrounding the bowel), lymphadenopathy, bowel strictures, and extramural complications such as fistulae and abscess. Shear wave elastography may be an effective way to differentiate severe fibrotic strictures, but this is an area that requires more investigation.14

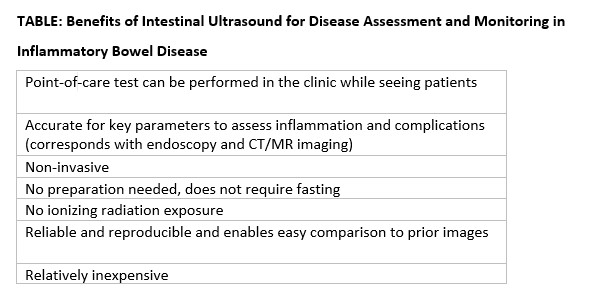

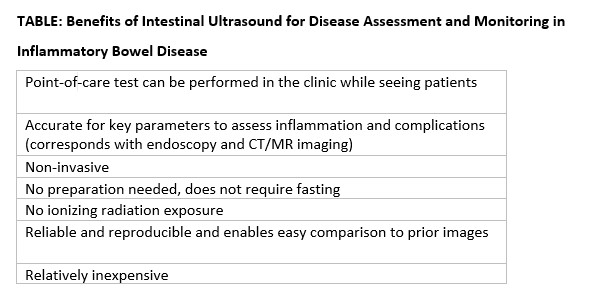

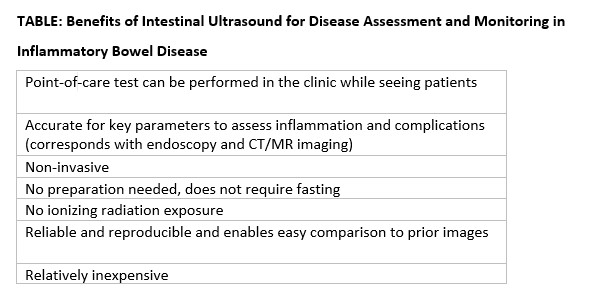

IUS has been shown to be an excellent tool in not only assessing disease activity and disease complication (with higher sensitivity than the Harvey-Bradshaw Index, serum C-reactive protein),15 but, unique to IUS, can provide early prediction of response in moderate to severe active UC.6,7 This has also been shown with transperineal ultrasound in patients with UC, with the ability to predict response to therapy as early as 1 week from induction therapy.16 Furthermore, it can be used to assess transmural healing, which has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes in Crohn’s patient, such as lower rates of hospitalizations, surgery, medication escalation, and need for corticosteroids.17 IUS is associated with great patient satisfaction and greater understanding of disease-related symptoms when the patient sees the inflammation of the bowel. (Table)

How can you get trained in IUS?

Training in IUS varies across the globe, from incorporation of IUS into the standard training curriculum to available training programs that can be followed and attended outside of medical training. In the United States, interested gastroenterologists can now be trained by becoming a member of the International Bowel Ultrasound Group (IBUS Group) and applying to the workshops now available. The IBUS Group has developed an IUS-specific training curriculum over the last 16 years, which is comprised of three modules: a 2-day hands-on workshop (Module 1) with final examination of theoretical competency, a preceptorship at an “expert center” with an experienced sonographer for a total of 4 weeks to complete 40 supervised IUS examinations (Module 2), and didactics and a final examination (Module 3). Also with support from Helmsley, the first Module 1 to be offered in the United States was hosted at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York in 2022, the second was hosted at the University of Chicago in March 2023, and the third is planned to take place at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles in March 2024.18 With the growing interest and demand for IUS training in the United States, U.S. experts are working to develop new training options that will be less time consuming, scalable, and still provide appropriate training and competency assessment.

How do you integrate IUS into your practice?

The keys to integrating IUS are a section chief or practice manager’s support of a trainee or faculty member for both funding of equipment and protected time for training and building of the program, as well as a permissive environment and collegial relationship with radiology. An ultrasound machine and additional transducers may range in price from $50,000-$120,000. Funding may be a limiting step for many, however. A detailed business plan is imperative to the success and investment of funds in an IUS program. With current billing practices in place that include ”limited abdominal ultrasound” (76705) and “Doppler ultrasound of the abdomen” (93975),19 reimbursement should include a technical fee, professional fee, and if in a hospital-based clinic, a facility fee. IUS pro-fee combined with technical fee is reimbursed at approximately 0.80 relative value units. When possible, the facility fee is included for approximately $800 per IUS visit. For billing and compliance with HIPAA, all billed IUS images must be stored in a durable and accessible format. It is recommended that the images and cine loops be digitally stored to the same or similar platform used by radiologists at the same institution. This requires early communication with the local information technology department for the connection of an ultrasound machine to the storage platform and/or electronic health record. Reporting results should be standardized with unique or otherwise available IUS templates, which also satisfy all billing components.9 The flow for incorporation of IUS into practice can be at the same time patients are seen during their visit, or alternatively, in a dedicated IUS clinic in which patients are referred by other providers and scheduled back to back.

Conclusions

In summary, the confluence of treat-to-target strategies in IBD, new treatment options in IBD, and successful efforts to translate IUS training and billing practices to the United States portends a great future for the field and for our patients.

Dr. Cleveland and Dr. Rubin, of the University of Chicago’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, are speakers for Samsung/Boston Imaging.

References

1. Turner D et al. Gastroenterology. Apr 2021;160(5):1570-83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031

2. Hart AL and Rubin DT. Gastroenterology. Apr 2022;162(5):1367-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.013

3. Rajagopalan A et al. JGH Open. Apr 2020;4(2):267-72. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12268

4. Calabrese E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Apr 2022;20(4):e711-22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.030

5. Ripolles T et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Oct 2016;22(10):2465-73. doi10.1097/MIB.0000000000000882

6. Maaser C et al. Gut. Sep 2020;69(9):1629-36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319451

7. Ilvemark J et al. J Crohns Colitis. Nov 23 2022;16(11):1725-34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac083

8. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jun 2020;51(12):1373-83. doi: 10.1111/apt.15767

9. Dolinger MT et al. Guide to Intestinal Ultrasound Credentialing, Documentation, and Billing for Gastroenterologists in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023.

10. Maconi G et al. Ultraschall Med. Jun 2018;39(3):304-17. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125329

11. Sasaki T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Mar 2014;49(3):295-301. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.871744

12. Limberg B. Z Gastroenterol. Jun 1999;37(6):495-508.

13. Miyoshi J et al. J Gastroenterol. Feb 2022;57(2):82-9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01847-3

14. Chen YJ et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Sep 15 2018;24(10):2183-90. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy115

15. Kucharzik T et al. Apr 2017;15(4):535-42e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040

16. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. May 2022;55(10):1320-9. doi: 10.1111/apt.16817

17. Vaughan R et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jul 2022;56(1):84-94. doi: 10.1111/apt.16892

18. International Bowel Ultrasound Group. https://ibus-group.org/

19. American Medical Association. CPT (Current Procedural Terminology). https://www.ama-assn.org/amaone/cpt-current-procedural-terminology

Evolving endpoints and treat-to-target strategies in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incorporate a need for more frequent assessments of the disease, including objective measures of inflammation.1,2 Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is a noninvasive, well-tolerated,3 repeatable, point-of-care (POC) test that is highly sensitive and specific in detection of bowel inflammation, transmural healing,4,5 and response to therapy in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).6-8 As IUS is taking hold in the United States, there is a great need to teach the next generation of gastroenterologists about its value, how to incorporate it into clinical practice, and how to become appropriately trained and maintain competency.

Why incorporate IUS in the United States now?

As IBD management has evolved, so has the appreciation for the value of bedside IUS as a tool that addresses very real needs for the field. Unlike other parts of the world in which ultrasound skills are part of the training curriculum, this has not been the case in internal medicine and gastroenterology training in the United States. In addition, there have been no specific billing codes or clear renumeration processes outlined for IUS,9 nor have there been any local training opportunities. Because of these challenges, it was not until recently that several leaders in IBD in the United States championed the potential of this technology and incorporated it into IBD management. Subsequently, a number of gastroenterologists have been trained and are now leading the effort to disseminate this tool throughout the United States. A consequence of these efforts resulted in support from the Helmsley Charitable Trust (Helmsley) and the creation of the Intestinal Ultrasound Group of the United States and Canada to address the gaps unique to North America as well as to strengthen the quality of IUS research through collaborations across the continent.

What is IUS, and when is it performed?

IUS is a sonographic exam performed by a gastroenterology-trained professional who scans the abdominal wall (and perineum when the rectum and perineal disease is evaluated), using both a convex low-frequency probe and linear high-frequency probe to evaluate the small intestine, colon, and rectum. The bowel is composed of five layers with alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers: the mucosal-lumen interface (not a true part of the bowel wall), deep mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. (Figure)

The most sensitive parameter for assessment of IBD activity is bowel wall thickness (≤ 3 mm in the small bowel and colon and ≤ 4 mm in the rectum are considered normal in adults).8,10 The second key parameter is the assessment of vascularization, in which presence of hyperemia suggests active disease.11 There are a number of indices to quantify hyperemia, with the most widely used being the Limberg score.12 Additional parameters include assessment of loss of the delineation of the bowel wall layers (loss of stratification signifies active inflammation), increased thickness of the submucosa,13 increased mesenteric fatty proliferation (with increased inflammation, mesenteric fat proliferation will appear as a hyperechoic area surrounding the bowel), lymphadenopathy, bowel strictures, and extramural complications such as fistulae and abscess. Shear wave elastography may be an effective way to differentiate severe fibrotic strictures, but this is an area that requires more investigation.14

IUS has been shown to be an excellent tool in not only assessing disease activity and disease complication (with higher sensitivity than the Harvey-Bradshaw Index, serum C-reactive protein),15 but, unique to IUS, can provide early prediction of response in moderate to severe active UC.6,7 This has also been shown with transperineal ultrasound in patients with UC, with the ability to predict response to therapy as early as 1 week from induction therapy.16 Furthermore, it can be used to assess transmural healing, which has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes in Crohn’s patient, such as lower rates of hospitalizations, surgery, medication escalation, and need for corticosteroids.17 IUS is associated with great patient satisfaction and greater understanding of disease-related symptoms when the patient sees the inflammation of the bowel. (Table)

How can you get trained in IUS?

Training in IUS varies across the globe, from incorporation of IUS into the standard training curriculum to available training programs that can be followed and attended outside of medical training. In the United States, interested gastroenterologists can now be trained by becoming a member of the International Bowel Ultrasound Group (IBUS Group) and applying to the workshops now available. The IBUS Group has developed an IUS-specific training curriculum over the last 16 years, which is comprised of three modules: a 2-day hands-on workshop (Module 1) with final examination of theoretical competency, a preceptorship at an “expert center” with an experienced sonographer for a total of 4 weeks to complete 40 supervised IUS examinations (Module 2), and didactics and a final examination (Module 3). Also with support from Helmsley, the first Module 1 to be offered in the United States was hosted at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York in 2022, the second was hosted at the University of Chicago in March 2023, and the third is planned to take place at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles in March 2024.18 With the growing interest and demand for IUS training in the United States, U.S. experts are working to develop new training options that will be less time consuming, scalable, and still provide appropriate training and competency assessment.

How do you integrate IUS into your practice?

The keys to integrating IUS are a section chief or practice manager’s support of a trainee or faculty member for both funding of equipment and protected time for training and building of the program, as well as a permissive environment and collegial relationship with radiology. An ultrasound machine and additional transducers may range in price from $50,000-$120,000. Funding may be a limiting step for many, however. A detailed business plan is imperative to the success and investment of funds in an IUS program. With current billing practices in place that include ”limited abdominal ultrasound” (76705) and “Doppler ultrasound of the abdomen” (93975),19 reimbursement should include a technical fee, professional fee, and if in a hospital-based clinic, a facility fee. IUS pro-fee combined with technical fee is reimbursed at approximately 0.80 relative value units. When possible, the facility fee is included for approximately $800 per IUS visit. For billing and compliance with HIPAA, all billed IUS images must be stored in a durable and accessible format. It is recommended that the images and cine loops be digitally stored to the same or similar platform used by radiologists at the same institution. This requires early communication with the local information technology department for the connection of an ultrasound machine to the storage platform and/or electronic health record. Reporting results should be standardized with unique or otherwise available IUS templates, which also satisfy all billing components.9 The flow for incorporation of IUS into practice can be at the same time patients are seen during their visit, or alternatively, in a dedicated IUS clinic in which patients are referred by other providers and scheduled back to back.

Conclusions

In summary, the confluence of treat-to-target strategies in IBD, new treatment options in IBD, and successful efforts to translate IUS training and billing practices to the United States portends a great future for the field and for our patients.

Dr. Cleveland and Dr. Rubin, of the University of Chicago’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, are speakers for Samsung/Boston Imaging.

References

1. Turner D et al. Gastroenterology. Apr 2021;160(5):1570-83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031

2. Hart AL and Rubin DT. Gastroenterology. Apr 2022;162(5):1367-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.013

3. Rajagopalan A et al. JGH Open. Apr 2020;4(2):267-72. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12268

4. Calabrese E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Apr 2022;20(4):e711-22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.030

5. Ripolles T et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Oct 2016;22(10):2465-73. doi10.1097/MIB.0000000000000882

6. Maaser C et al. Gut. Sep 2020;69(9):1629-36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319451

7. Ilvemark J et al. J Crohns Colitis. Nov 23 2022;16(11):1725-34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac083

8. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jun 2020;51(12):1373-83. doi: 10.1111/apt.15767

9. Dolinger MT et al. Guide to Intestinal Ultrasound Credentialing, Documentation, and Billing for Gastroenterologists in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023.

10. Maconi G et al. Ultraschall Med. Jun 2018;39(3):304-17. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125329

11. Sasaki T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Mar 2014;49(3):295-301. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.871744

12. Limberg B. Z Gastroenterol. Jun 1999;37(6):495-508.

13. Miyoshi J et al. J Gastroenterol. Feb 2022;57(2):82-9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01847-3

14. Chen YJ et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Sep 15 2018;24(10):2183-90. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy115

15. Kucharzik T et al. Apr 2017;15(4):535-42e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040

16. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. May 2022;55(10):1320-9. doi: 10.1111/apt.16817

17. Vaughan R et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jul 2022;56(1):84-94. doi: 10.1111/apt.16892

18. International Bowel Ultrasound Group. https://ibus-group.org/

19. American Medical Association. CPT (Current Procedural Terminology). https://www.ama-assn.org/amaone/cpt-current-procedural-terminology

Evolving endpoints and treat-to-target strategies in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incorporate a need for more frequent assessments of the disease, including objective measures of inflammation.1,2 Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is a noninvasive, well-tolerated,3 repeatable, point-of-care (POC) test that is highly sensitive and specific in detection of bowel inflammation, transmural healing,4,5 and response to therapy in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).6-8 As IUS is taking hold in the United States, there is a great need to teach the next generation of gastroenterologists about its value, how to incorporate it into clinical practice, and how to become appropriately trained and maintain competency.

Why incorporate IUS in the United States now?

As IBD management has evolved, so has the appreciation for the value of bedside IUS as a tool that addresses very real needs for the field. Unlike other parts of the world in which ultrasound skills are part of the training curriculum, this has not been the case in internal medicine and gastroenterology training in the United States. In addition, there have been no specific billing codes or clear renumeration processes outlined for IUS,9 nor have there been any local training opportunities. Because of these challenges, it was not until recently that several leaders in IBD in the United States championed the potential of this technology and incorporated it into IBD management. Subsequently, a number of gastroenterologists have been trained and are now leading the effort to disseminate this tool throughout the United States. A consequence of these efforts resulted in support from the Helmsley Charitable Trust (Helmsley) and the creation of the Intestinal Ultrasound Group of the United States and Canada to address the gaps unique to North America as well as to strengthen the quality of IUS research through collaborations across the continent.

What is IUS, and when is it performed?

IUS is a sonographic exam performed by a gastroenterology-trained professional who scans the abdominal wall (and perineum when the rectum and perineal disease is evaluated), using both a convex low-frequency probe and linear high-frequency probe to evaluate the small intestine, colon, and rectum. The bowel is composed of five layers with alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers: the mucosal-lumen interface (not a true part of the bowel wall), deep mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. (Figure)

The most sensitive parameter for assessment of IBD activity is bowel wall thickness (≤ 3 mm in the small bowel and colon and ≤ 4 mm in the rectum are considered normal in adults).8,10 The second key parameter is the assessment of vascularization, in which presence of hyperemia suggests active disease.11 There are a number of indices to quantify hyperemia, with the most widely used being the Limberg score.12 Additional parameters include assessment of loss of the delineation of the bowel wall layers (loss of stratification signifies active inflammation), increased thickness of the submucosa,13 increased mesenteric fatty proliferation (with increased inflammation, mesenteric fat proliferation will appear as a hyperechoic area surrounding the bowel), lymphadenopathy, bowel strictures, and extramural complications such as fistulae and abscess. Shear wave elastography may be an effective way to differentiate severe fibrotic strictures, but this is an area that requires more investigation.14

IUS has been shown to be an excellent tool in not only assessing disease activity and disease complication (with higher sensitivity than the Harvey-Bradshaw Index, serum C-reactive protein),15 but, unique to IUS, can provide early prediction of response in moderate to severe active UC.6,7 This has also been shown with transperineal ultrasound in patients with UC, with the ability to predict response to therapy as early as 1 week from induction therapy.16 Furthermore, it can be used to assess transmural healing, which has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes in Crohn’s patient, such as lower rates of hospitalizations, surgery, medication escalation, and need for corticosteroids.17 IUS is associated with great patient satisfaction and greater understanding of disease-related symptoms when the patient sees the inflammation of the bowel. (Table)

How can you get trained in IUS?

Training in IUS varies across the globe, from incorporation of IUS into the standard training curriculum to available training programs that can be followed and attended outside of medical training. In the United States, interested gastroenterologists can now be trained by becoming a member of the International Bowel Ultrasound Group (IBUS Group) and applying to the workshops now available. The IBUS Group has developed an IUS-specific training curriculum over the last 16 years, which is comprised of three modules: a 2-day hands-on workshop (Module 1) with final examination of theoretical competency, a preceptorship at an “expert center” with an experienced sonographer for a total of 4 weeks to complete 40 supervised IUS examinations (Module 2), and didactics and a final examination (Module 3). Also with support from Helmsley, the first Module 1 to be offered in the United States was hosted at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York in 2022, the second was hosted at the University of Chicago in March 2023, and the third is planned to take place at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles in March 2024.18 With the growing interest and demand for IUS training in the United States, U.S. experts are working to develop new training options that will be less time consuming, scalable, and still provide appropriate training and competency assessment.

How do you integrate IUS into your practice?

The keys to integrating IUS are a section chief or practice manager’s support of a trainee or faculty member for both funding of equipment and protected time for training and building of the program, as well as a permissive environment and collegial relationship with radiology. An ultrasound machine and additional transducers may range in price from $50,000-$120,000. Funding may be a limiting step for many, however. A detailed business plan is imperative to the success and investment of funds in an IUS program. With current billing practices in place that include ”limited abdominal ultrasound” (76705) and “Doppler ultrasound of the abdomen” (93975),19 reimbursement should include a technical fee, professional fee, and if in a hospital-based clinic, a facility fee. IUS pro-fee combined with technical fee is reimbursed at approximately 0.80 relative value units. When possible, the facility fee is included for approximately $800 per IUS visit. For billing and compliance with HIPAA, all billed IUS images must be stored in a durable and accessible format. It is recommended that the images and cine loops be digitally stored to the same or similar platform used by radiologists at the same institution. This requires early communication with the local information technology department for the connection of an ultrasound machine to the storage platform and/or electronic health record. Reporting results should be standardized with unique or otherwise available IUS templates, which also satisfy all billing components.9 The flow for incorporation of IUS into practice can be at the same time patients are seen during their visit, or alternatively, in a dedicated IUS clinic in which patients are referred by other providers and scheduled back to back.

Conclusions

In summary, the confluence of treat-to-target strategies in IBD, new treatment options in IBD, and successful efforts to translate IUS training and billing practices to the United States portends a great future for the field and for our patients.

Dr. Cleveland and Dr. Rubin, of the University of Chicago’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, are speakers for Samsung/Boston Imaging.

References

1. Turner D et al. Gastroenterology. Apr 2021;160(5):1570-83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031

2. Hart AL and Rubin DT. Gastroenterology. Apr 2022;162(5):1367-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.013

3. Rajagopalan A et al. JGH Open. Apr 2020;4(2):267-72. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12268

4. Calabrese E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Apr 2022;20(4):e711-22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.030

5. Ripolles T et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Oct 2016;22(10):2465-73. doi10.1097/MIB.0000000000000882

6. Maaser C et al. Gut. Sep 2020;69(9):1629-36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319451

7. Ilvemark J et al. J Crohns Colitis. Nov 23 2022;16(11):1725-34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac083

8. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jun 2020;51(12):1373-83. doi: 10.1111/apt.15767

9. Dolinger MT et al. Guide to Intestinal Ultrasound Credentialing, Documentation, and Billing for Gastroenterologists in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023.

10. Maconi G et al. Ultraschall Med. Jun 2018;39(3):304-17. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125329

11. Sasaki T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Mar 2014;49(3):295-301. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.871744

12. Limberg B. Z Gastroenterol. Jun 1999;37(6):495-508.

13. Miyoshi J et al. J Gastroenterol. Feb 2022;57(2):82-9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01847-3

14. Chen YJ et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Sep 15 2018;24(10):2183-90. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy115

15. Kucharzik T et al. Apr 2017;15(4):535-42e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040

16. Sagami S et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. May 2022;55(10):1320-9. doi: 10.1111/apt.16817

17. Vaughan R et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Jul 2022;56(1):84-94. doi: 10.1111/apt.16892

18. International Bowel Ultrasound Group. https://ibus-group.org/

19. American Medical Association. CPT (Current Procedural Terminology). https://www.ama-assn.org/amaone/cpt-current-procedural-terminology

Does CRC risk in IBD extend to close family members?

new research suggests.

In a large Swedish study, a history of IBD among first-degree relatives was not associated with an increased risk of CRC, even when considering various characteristics of IBD and CRC history.

The findings suggest that extra screening for CRC may not be needed for children, siblings, or parents of those with IBD, say the study authors, led by Kai Wang, MD, PhD, with Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. The findings strengthen the theory that it’s inflammation or atypism of the colon of people with IBD that confers the increased CRC risk.

“There is nothing in this study that changes our existing practice,” said Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MD, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who was not involved in the research. “It is already the thought that inflammation in IBD increases risk of cancer,” which would not increase CRC risk among family members.

The study appeared in the International Journal of Cancer.

Patients with IBD are known to be at increased risk for CRC. However, the association between family history of IBD and CRC risk remains less clear. Current CRC screening recommendations are the same for patients who have family members with IBD and for those who do not.

The Swedish nationwide case-control study included 69,659 individuals with CRC, of whom 1,599 (2.3%) had IBD, and 343,032 matched control persons who did not have CRC, of whom 1,477 (0.4%) had IBD.

Overall, 2.2% of CRC case patients and control patients had at least one first-degree relative who had a history of IBD.

After adjusting for family history of CRC, the authors did not find an increase in risk for CRC among first-degree relatives of people with IBD (odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.02).

The null association was consistently observed regardless of IBD subtype (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), the number of first-degree relatives with IBD, age at first IBD diagnosis, maximum location or extent of IBD, or type of relative (parent, sibling, or offspring). The null association remained for early-onset CRC diagnosed before age 50.

Overall, these findings suggest that IBD and CRC may not have substantial familial clustering or shared genetic susceptibility and provide “robust evidence that a family history of IBD did not increase the risk of CRC, supporting use of the same routine CRC screening strategy in offspring, siblings, and parents of IBD patients as in the general population,” Dr. Wang and colleagues conclude.

This “well-done” study is one of the largest to date to evaluate first-degree relatives of IBD patients and their risk of CRC, said Shannon Chang, MD, with NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, who wasn’t involved in the research.

The findings are reassuring, as the authors assessed several factors and found that family members of patients with IBD are not at higher risk for CRC, compared with the general population, Dr. Chang added.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, ALF funding, the Swedish Research Council, and the Swedish Cancer Foundation. Dr. Wang, Dr. Chang, and Dr. Ananthakrishnan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In a large Swedish study, a history of IBD among first-degree relatives was not associated with an increased risk of CRC, even when considering various characteristics of IBD and CRC history.

The findings suggest that extra screening for CRC may not be needed for children, siblings, or parents of those with IBD, say the study authors, led by Kai Wang, MD, PhD, with Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. The findings strengthen the theory that it’s inflammation or atypism of the colon of people with IBD that confers the increased CRC risk.

“There is nothing in this study that changes our existing practice,” said Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MD, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who was not involved in the research. “It is already the thought that inflammation in IBD increases risk of cancer,” which would not increase CRC risk among family members.

The study appeared in the International Journal of Cancer.

Patients with IBD are known to be at increased risk for CRC. However, the association between family history of IBD and CRC risk remains less clear. Current CRC screening recommendations are the same for patients who have family members with IBD and for those who do not.

The Swedish nationwide case-control study included 69,659 individuals with CRC, of whom 1,599 (2.3%) had IBD, and 343,032 matched control persons who did not have CRC, of whom 1,477 (0.4%) had IBD.

Overall, 2.2% of CRC case patients and control patients had at least one first-degree relative who had a history of IBD.

After adjusting for family history of CRC, the authors did not find an increase in risk for CRC among first-degree relatives of people with IBD (odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.02).

The null association was consistently observed regardless of IBD subtype (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), the number of first-degree relatives with IBD, age at first IBD diagnosis, maximum location or extent of IBD, or type of relative (parent, sibling, or offspring). The null association remained for early-onset CRC diagnosed before age 50.

Overall, these findings suggest that IBD and CRC may not have substantial familial clustering or shared genetic susceptibility and provide “robust evidence that a family history of IBD did not increase the risk of CRC, supporting use of the same routine CRC screening strategy in offspring, siblings, and parents of IBD patients as in the general population,” Dr. Wang and colleagues conclude.

This “well-done” study is one of the largest to date to evaluate first-degree relatives of IBD patients and their risk of CRC, said Shannon Chang, MD, with NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, who wasn’t involved in the research.

The findings are reassuring, as the authors assessed several factors and found that family members of patients with IBD are not at higher risk for CRC, compared with the general population, Dr. Chang added.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, ALF funding, the Swedish Research Council, and the Swedish Cancer Foundation. Dr. Wang, Dr. Chang, and Dr. Ananthakrishnan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In a large Swedish study, a history of IBD among first-degree relatives was not associated with an increased risk of CRC, even when considering various characteristics of IBD and CRC history.

The findings suggest that extra screening for CRC may not be needed for children, siblings, or parents of those with IBD, say the study authors, led by Kai Wang, MD, PhD, with Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. The findings strengthen the theory that it’s inflammation or atypism of the colon of people with IBD that confers the increased CRC risk.

“There is nothing in this study that changes our existing practice,” said Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MD, MPH, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who was not involved in the research. “It is already the thought that inflammation in IBD increases risk of cancer,” which would not increase CRC risk among family members.

The study appeared in the International Journal of Cancer.

Patients with IBD are known to be at increased risk for CRC. However, the association between family history of IBD and CRC risk remains less clear. Current CRC screening recommendations are the same for patients who have family members with IBD and for those who do not.

The Swedish nationwide case-control study included 69,659 individuals with CRC, of whom 1,599 (2.3%) had IBD, and 343,032 matched control persons who did not have CRC, of whom 1,477 (0.4%) had IBD.

Overall, 2.2% of CRC case patients and control patients had at least one first-degree relative who had a history of IBD.

After adjusting for family history of CRC, the authors did not find an increase in risk for CRC among first-degree relatives of people with IBD (odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.02).

The null association was consistently observed regardless of IBD subtype (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), the number of first-degree relatives with IBD, age at first IBD diagnosis, maximum location or extent of IBD, or type of relative (parent, sibling, or offspring). The null association remained for early-onset CRC diagnosed before age 50.

Overall, these findings suggest that IBD and CRC may not have substantial familial clustering or shared genetic susceptibility and provide “robust evidence that a family history of IBD did not increase the risk of CRC, supporting use of the same routine CRC screening strategy in offspring, siblings, and parents of IBD patients as in the general population,” Dr. Wang and colleagues conclude.

This “well-done” study is one of the largest to date to evaluate first-degree relatives of IBD patients and their risk of CRC, said Shannon Chang, MD, with NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, who wasn’t involved in the research.

The findings are reassuring, as the authors assessed several factors and found that family members of patients with IBD are not at higher risk for CRC, compared with the general population, Dr. Chang added.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, ALF funding, the Swedish Research Council, and the Swedish Cancer Foundation. Dr. Wang, Dr. Chang, and Dr. Ananthakrishnan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CANCER

AGA guideline defines role of biomarkers in ulcerative colitis

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has released a new clinical practice guideline defining the role of biomarkers in monitoring and managing ulcerative colitis (UC).

, reported lead guideline panelist Siddharth Singh, MD, of University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and colleagues.

“[I]n routine clinical practice, repeated endoscopic assessment is invasive, expensive, and may be impractical,” the panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “There is an important need for understanding how noninvasive biomarkers may serve as accurate and reliable surrogates for endoscopic assessment of inflammation and whether they can be more readily implemented in a UC care pathway.”

After reviewing relevant randomized controlled trials and observational studies, Dr. Singh and colleagues issued seven conditional recommendations, three of which concern patients in symptomatic remission, and four of which apply to patients with symptomatically active UC.

“The key take-home message is that the routine measurement of noninvasive biomarkers in addition to assessment of patient reported symptoms is critical in evaluating the disease burden of UC,” said Jordan E. Axelrad, MD, MPH, director of clinical and translational research at NYU Langone Health’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, New York. “Many of these recommendations regarding the assessment of disease activity beyond symptoms alone are widely accepted, particularity at tertiary IBD centers; however, this guideline serves to formalize and structure the recommendations, with appropriate test cutoff values, in a simple UC care pathway.”

Recommendations for patients in symptomatic remission

For patients in remission, the guideline advises monitoring both symptoms and biomarkers, with biomarkers measured every 6-12 months.

Asymptomatic patients with normal biomarkers can skip routine endoscopy to evaluate disease activity, according to the guideline, but those with abnormal fecal calprotectin, fecal lactoferrin, or serum C-reactive protein (CRP) are candidates for endoscopic assessment instead of empiric treatment adjustment. Patients may still need periodic colonoscopy for dysplasia surveillance.

“The most important pearl [from the guideline] is that fecal calprotectin less than 150 mcg/g, normal fecal lactoferrin, or normal CRP, can be used to rule out active inflammation in patients in symptomatic remission,” according to Dr. Axelrad.

The guideline suggests that the two fecal biomarkers “may be optimal for monitoring and may be particularly useful in patients where biomarkers have historically correlated with endoscopic disease activity.” In contrast, normal CRP may be insufficient to rule out moderate to severe endoscopic inflammation in patients who recently entered remission following treatment adjustment.

While abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic patients are sufficient cause for endoscopy, the guideline also suggests that retesting in 3-6 months is a reasonable alternative. If biomarkers are again elevated, then endoscopic evaluation should be considered.

Recommendations for patients with symptomatically active disease

The recommendations for patients with symptomatically active UC follow a similar pathway. The guideline advises an evaluation strategy combining symptoms and biomarkers instead of symptoms alone.

For example, patients with moderate to severe symptoms suggestive of flare and elevated biomarkers are candidates for treatment adjustment without endoscopy.

Still, patient preferences should be considered, Dr. Singh and colleagues noted.

“Patients who place greater value in confirming inflammation, particularly when making significant treatment decisions (such as starting or switching immunosuppressive therapies), and lesser value on the inconvenience of endoscopy, may choose to pursue endoscopic evaluation before treatment adjustment,” they wrote.

For patients with mild symptoms, endoscopy is generally recommended, according to the guideline, unless the patient recently had moderate to severe symptoms and has improved after treatment adjustment; in that case, biomarkers can be used to fine-tune therapy without the need for endoscopy.

Again, providers should engage in shared-decision making, the guideline advises. Patients with mild symptoms but no biomarker results may reasonably elect to undergo endoscopy prior to testing biomarkers, while patients with mild symptoms and normal biomarkers may reasonably elect to retest biomarkers in 3-6 months.

Data remain insufficient to recommend biomarkers over endoscopy

Dr. Singh and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting an insufficient level of direct evidence necessary to recommend a biomarker-based treat-to-target strategy over endoscopy-based monitoring strategy, despite indirect evidence suggesting this may be the case.

“[T]here have not been any studies comparing a biomarker-based strategy with an endoscopy-based strategy for assessment and monitoring of endoscopic remission,” they wrote. “This was identified as a knowledge gap by the panel.”

The authors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, AbbVie, Lilly, and others. Dr. Axelrad disclosed relationships with Janssen, AbbVie, Pfizer, and others.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has released a new clinical practice guideline defining the role of biomarkers in monitoring and managing ulcerative colitis (UC).

, reported lead guideline panelist Siddharth Singh, MD, of University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and colleagues.

“[I]n routine clinical practice, repeated endoscopic assessment is invasive, expensive, and may be impractical,” the panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “There is an important need for understanding how noninvasive biomarkers may serve as accurate and reliable surrogates for endoscopic assessment of inflammation and whether they can be more readily implemented in a UC care pathway.”

After reviewing relevant randomized controlled trials and observational studies, Dr. Singh and colleagues issued seven conditional recommendations, three of which concern patients in symptomatic remission, and four of which apply to patients with symptomatically active UC.

“The key take-home message is that the routine measurement of noninvasive biomarkers in addition to assessment of patient reported symptoms is critical in evaluating the disease burden of UC,” said Jordan E. Axelrad, MD, MPH, director of clinical and translational research at NYU Langone Health’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, New York. “Many of these recommendations regarding the assessment of disease activity beyond symptoms alone are widely accepted, particularity at tertiary IBD centers; however, this guideline serves to formalize and structure the recommendations, with appropriate test cutoff values, in a simple UC care pathway.”

Recommendations for patients in symptomatic remission

For patients in remission, the guideline advises monitoring both symptoms and biomarkers, with biomarkers measured every 6-12 months.

Asymptomatic patients with normal biomarkers can skip routine endoscopy to evaluate disease activity, according to the guideline, but those with abnormal fecal calprotectin, fecal lactoferrin, or serum C-reactive protein (CRP) are candidates for endoscopic assessment instead of empiric treatment adjustment. Patients may still need periodic colonoscopy for dysplasia surveillance.

“The most important pearl [from the guideline] is that fecal calprotectin less than 150 mcg/g, normal fecal lactoferrin, or normal CRP, can be used to rule out active inflammation in patients in symptomatic remission,” according to Dr. Axelrad.

The guideline suggests that the two fecal biomarkers “may be optimal for monitoring and may be particularly useful in patients where biomarkers have historically correlated with endoscopic disease activity.” In contrast, normal CRP may be insufficient to rule out moderate to severe endoscopic inflammation in patients who recently entered remission following treatment adjustment.

While abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic patients are sufficient cause for endoscopy, the guideline also suggests that retesting in 3-6 months is a reasonable alternative. If biomarkers are again elevated, then endoscopic evaluation should be considered.

Recommendations for patients with symptomatically active disease

The recommendations for patients with symptomatically active UC follow a similar pathway. The guideline advises an evaluation strategy combining symptoms and biomarkers instead of symptoms alone.

For example, patients with moderate to severe symptoms suggestive of flare and elevated biomarkers are candidates for treatment adjustment without endoscopy.

Still, patient preferences should be considered, Dr. Singh and colleagues noted.

“Patients who place greater value in confirming inflammation, particularly when making significant treatment decisions (such as starting or switching immunosuppressive therapies), and lesser value on the inconvenience of endoscopy, may choose to pursue endoscopic evaluation before treatment adjustment,” they wrote.

For patients with mild symptoms, endoscopy is generally recommended, according to the guideline, unless the patient recently had moderate to severe symptoms and has improved after treatment adjustment; in that case, biomarkers can be used to fine-tune therapy without the need for endoscopy.

Again, providers should engage in shared-decision making, the guideline advises. Patients with mild symptoms but no biomarker results may reasonably elect to undergo endoscopy prior to testing biomarkers, while patients with mild symptoms and normal biomarkers may reasonably elect to retest biomarkers in 3-6 months.

Data remain insufficient to recommend biomarkers over endoscopy

Dr. Singh and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting an insufficient level of direct evidence necessary to recommend a biomarker-based treat-to-target strategy over endoscopy-based monitoring strategy, despite indirect evidence suggesting this may be the case.

“[T]here have not been any studies comparing a biomarker-based strategy with an endoscopy-based strategy for assessment and monitoring of endoscopic remission,” they wrote. “This was identified as a knowledge gap by the panel.”

The authors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, AbbVie, Lilly, and others. Dr. Axelrad disclosed relationships with Janssen, AbbVie, Pfizer, and others.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has released a new clinical practice guideline defining the role of biomarkers in monitoring and managing ulcerative colitis (UC).

, reported lead guideline panelist Siddharth Singh, MD, of University of California San Diego, La Jolla, Calif., and colleagues.

“[I]n routine clinical practice, repeated endoscopic assessment is invasive, expensive, and may be impractical,” the panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “There is an important need for understanding how noninvasive biomarkers may serve as accurate and reliable surrogates for endoscopic assessment of inflammation and whether they can be more readily implemented in a UC care pathway.”

After reviewing relevant randomized controlled trials and observational studies, Dr. Singh and colleagues issued seven conditional recommendations, three of which concern patients in symptomatic remission, and four of which apply to patients with symptomatically active UC.

“The key take-home message is that the routine measurement of noninvasive biomarkers in addition to assessment of patient reported symptoms is critical in evaluating the disease burden of UC,” said Jordan E. Axelrad, MD, MPH, director of clinical and translational research at NYU Langone Health’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, New York. “Many of these recommendations regarding the assessment of disease activity beyond symptoms alone are widely accepted, particularity at tertiary IBD centers; however, this guideline serves to formalize and structure the recommendations, with appropriate test cutoff values, in a simple UC care pathway.”

Recommendations for patients in symptomatic remission

For patients in remission, the guideline advises monitoring both symptoms and biomarkers, with biomarkers measured every 6-12 months.

Asymptomatic patients with normal biomarkers can skip routine endoscopy to evaluate disease activity, according to the guideline, but those with abnormal fecal calprotectin, fecal lactoferrin, or serum C-reactive protein (CRP) are candidates for endoscopic assessment instead of empiric treatment adjustment. Patients may still need periodic colonoscopy for dysplasia surveillance.

“The most important pearl [from the guideline] is that fecal calprotectin less than 150 mcg/g, normal fecal lactoferrin, or normal CRP, can be used to rule out active inflammation in patients in symptomatic remission,” according to Dr. Axelrad.

The guideline suggests that the two fecal biomarkers “may be optimal for monitoring and may be particularly useful in patients where biomarkers have historically correlated with endoscopic disease activity.” In contrast, normal CRP may be insufficient to rule out moderate to severe endoscopic inflammation in patients who recently entered remission following treatment adjustment.

While abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic patients are sufficient cause for endoscopy, the guideline also suggests that retesting in 3-6 months is a reasonable alternative. If biomarkers are again elevated, then endoscopic evaluation should be considered.

Recommendations for patients with symptomatically active disease

The recommendations for patients with symptomatically active UC follow a similar pathway. The guideline advises an evaluation strategy combining symptoms and biomarkers instead of symptoms alone.

For example, patients with moderate to severe symptoms suggestive of flare and elevated biomarkers are candidates for treatment adjustment without endoscopy.

Still, patient preferences should be considered, Dr. Singh and colleagues noted.

“Patients who place greater value in confirming inflammation, particularly when making significant treatment decisions (such as starting or switching immunosuppressive therapies), and lesser value on the inconvenience of endoscopy, may choose to pursue endoscopic evaluation before treatment adjustment,” they wrote.

For patients with mild symptoms, endoscopy is generally recommended, according to the guideline, unless the patient recently had moderate to severe symptoms and has improved after treatment adjustment; in that case, biomarkers can be used to fine-tune therapy without the need for endoscopy.

Again, providers should engage in shared-decision making, the guideline advises. Patients with mild symptoms but no biomarker results may reasonably elect to undergo endoscopy prior to testing biomarkers, while patients with mild symptoms and normal biomarkers may reasonably elect to retest biomarkers in 3-6 months.

Data remain insufficient to recommend biomarkers over endoscopy

Dr. Singh and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting an insufficient level of direct evidence necessary to recommend a biomarker-based treat-to-target strategy over endoscopy-based monitoring strategy, despite indirect evidence suggesting this may be the case.

“[T]here have not been any studies comparing a biomarker-based strategy with an endoscopy-based strategy for assessment and monitoring of endoscopic remission,” they wrote. “This was identified as a knowledge gap by the panel.”

The authors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, AbbVie, Lilly, and others. Dr. Axelrad disclosed relationships with Janssen, AbbVie, Pfizer, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

New influx of Humira biosimilars may not drive immediate change

Gastroenterologists in 2023 will have more tools in their arsenal to treat patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. As many as 8-10 adalimumab biosimilars are anticipated to come on the market this year, giving mainstay drug Humira some vigorous competition.

Three scenarios will drive adalimumab biosimilar initiation: Insurance preference for the initial treatment of a newly diagnosed condition, a change in a patient’s insurance plan, or an insurance-mandated switch, said Edward C. Oldfield IV, MD, assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School’s division of gastroenterology in Norfolk.

“Outside of these scenarios, I would encourage patients to remain on their current biologic so long as cost and accessibility remain stable,” said Dr. Oldfield.

Many factors will contribute to the success of biosimilars. Will physicians be prescribing them? How are biosimilars placed on formularies and will they be given preferred status? How will manufacturers price their biosimilars? “We have to wait and see to get the answers to these questions,” said Steven Newmark, JD, MPA, chief legal officer and director of policy, Global Healthy Living Foundation/CreakyJoints, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in New York.

Prescribing biosimilars is no different than prescribing originator biologics, so providers should know how to use them, said Mr. Newmark. “Most important will be the availability of patient-friendly resources that providers can share with their patients to provide education about and confidence in using biosimilars,” he added.

Overall, biosimilars are a good thing, said Dr. Oldfield. “In the long run they should bring down costs and increase access to medications for our patients.”

Others are skeptical that the adalimumab biosimilars will save patients much money.

Biosimilar laws were created to lower costs. However, if a patient with insurance pays only $5 a month out of pocket for Humira – a drug that normally costs $7,000 without coverage – it’s unlikely they would want to switch unless there’s comparable savings from the biosimilar, said Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, medical director of the Digestive Health Center and professor of medicine at Northwestern Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Like generics, Humira biosimilars may face some initial backlash, said Dr. Hanauer.

2023 broadens scope of adalimumab treatments

The American Gastroenterological Association describes a biosimilar as something that’s “highly similar to, but not an exact copy of, a biologic reference product already approved” by the Food and Drug Administration. Congress under the 2010 Affordable Care Act created a special, abbreviated pathway to approval for biosimilars.

AbbVie’s Humira, the global revenue for which exceeded $20 billion in 2021, has long dominated the U.S. market on injectable treatments for autoimmune diseases. The popular drug faces some competition in 2023, however, following a series of legal settlements that allowed AbbVie competitors to release their own adalimumab biosimilars.

“So far, we haven’t seen biosimilars live up to their potential in the U.S. in the inflammatory space,” said Mr. Newmark. This may change, however. Previously, biosimilars have required infusion, which demanded more time, commitment, and travel from patients. “The new set of forthcoming Humira biosimilars are injectables, an administration method preferred by patients,” he said.

The FDA will approve a biosimilar if it determines that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product, and that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological and reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product.

The agency to date has approved 8 adalimumab biosimilars. These include: Idacio (adalimumab-aacf, Fresenius Kabi); Amjevita (adalimumab-atto, Amgen); Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd, Organon); Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm, Boehringer Ingelheim); Yusimry (adalimumab-aqvh from Coherus BioSciences); Hulio (adalimumab-fkjp; Mylan/Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics); Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz, Sandoz), and Abrilada (adalimumab-afzb, Pfizer).

“While FDA doesn’t formally track when products come to market, we know based on published reports that application holders for many of the currently FDA-approved biosimilars plan to market this year, starting with Amjevita being the first adalimumab biosimilar launched” in January, said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars at the agency.

At press time, two other companies (Celltrion and Alvotech/Teva) were awaiting FDA approval for their adalimumab biosimilar drugs.

Among the eight approved drugs, Cyltezo is the only one that has a designation for interchangeability with Humira.

An interchangeable biosimilar may be substituted at the pharmacy without the intervention of the prescriber – much like generics are substituted, depending on state laws, said Dr. Yim. “However, in terms of safety and effectiveness, FDA’s standards for approval mean that biosimilar or interchangeable biosimilar products can be used in place of the reference product they were compared to.”

FDA-approved biosimilars undergo a rigorous evaluation for safety, effectiveness, and quality for their approved conditions of use, she continued. “Therefore, patients and health care providers can rely on a biosimilar to be as safe and effective for its approved uses as the original biological product.”

Remicade as a yardstick

Gastroenterologists dealt with this situation once before, when Remicade (infliximab) biosimilars came on the market in 2016, noted Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease and Surgery Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

Remicade and Humira are both tumor necrosis factor inhibitors with the same mechanism of action and many of the same indications. “We already had that experience with Remicade and biosimilar switch 2 or 3 years ago. Now we’re talking about Humira,” said Dr. Regueiro.

Most GI doctors have prescribed one of the more common infliximab biosimilars (Inflectra or Renflexis), noted Dr. Oldfield.

Cardinal Health, which recently surveyed 300 gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, and dermatologists about adalimumab biosimilars, found that gastroenterologists had the highest comfort level in prescribing them. Their top concern, however, was changing a patient from adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar.

For most patients, Dr. Oldfield sees the Humira reference biologic and biosimilar as equivalent.

However, he said he would change a patient’s drug only if there were a good reason or if his hand was forced by insurance. He would not make the change for a patient who recently began induction with the reference biologic or a patient with highly active clinical disease.

“While there is limited data to support this, I would also have some qualms about changing a patient from reference biologic to a biosimilar if they previously had immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure due to antibody development with a biologic and were currently doing well on their new biologic,” he said.

Those with a new ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s diagnosis who are initiating a biologic for the first time might consider a biosimilar. If a patient is transitioning from a reference biologic to a biosimilar, “I would want to make that change during a time of stable remission and with the recognition that the switch is not a temporary switch, but a long-term switch,” he continued.

A paper that reviewed 23 observational studies of adalimumab and other biosimilars found that switching biosimilars was safe and effective. But if possible, patients should minimize the number of switches until more robust long-term data are available, added Dr. Oldfield.

If a patient is apprehensive about switching to a new therapy, “one may need to be cognizant of the ‘nocebo’ effect in which there is an unexplained or unfavorable therapeutic effect after switching,” he said.

Other gastroenterologists voiced similar reservations about switching. “I won’t use an adalimumab biosimilar unless the patient requests it, the insurance requires it, or there is a cost advantage for the patient such that they prefer it,” said Doug Wolf, MD, an Atlanta gastroenterologist.

“There is no medical treatment advantage to a biosimilar, especially if switching from Humira,” added Dr. Wolf.

Insurance will guide treatment

Once a drug is approved for use by the FDA, that drug will be available in all 50 states. “Different private insurance formularies, as well as state Medicaid formularies, might affect the actual ability of patients to receive such drugs,” said Mr. Newmark.

Patients should consult with their providers and insurance companies to see what therapies are available, he advised.

Dr. Hanauer anticipates some headaches arising for patients and doctors alike when negotiating for a specific drug.

Cyltezo may be the only biosimilar interchangeable with Humira, but the third-party pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) could negotiate for one of the noninterchangeable ones. “On a yearly basis they could switch their preference,” said Dr. Hanauer.

In the Cardinal Health survey, more than 60% of respondents said they would feel comfortable prescribing an adalimumab biosimilar only with an interchangeability designation.

A PBM may offer a patient Cyltezo if it’s cheaper than Humira. If the patient insists on staying on Humira, then they’ll have to pay more for that drug on their payer’s formulary, said Dr. Hanauer. In a worst-case scenario, a physician may have to appeal on a patient’s behalf to get Humira if the insurer offers only the biosimilar.

Taking that step to appeal is a major hassle for the physician, and leads to extra back door costs as well, said Dr. Hanauer.

Humira manufacturer AbbVie, in turn, may offer discounts and rebates to the PBMs to put Humira on their formulary. “That’s the AbbVie negotiating power. It’s not that the cost is going to be that much different. It’s going to be that there are rebates and discounts that are going to make the cost different,” he added.

As a community physician, Dr. Oldfield has specific concerns about accessibility.

The ever-increasing burden of insurance documentation and prior authorization means it can take weeks or months to get these medications approved. “The addition of new biosimilars is a welcome entrance if it can get patients the medications they need when they need it,” he said.

When it comes to prescribing biologics, many physicians rely on ancillary staff for assistance. It’s a team effort to sift through all the paperwork, observed Dr. Oldfield.