User login

Intensive surveillance after CRC resection does not improve survival

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.

There were 356 recurrences in patients initially treated for colon cancer. CEA surveillance with or without CT scan was associated with an increased incidence of secondary resection with curative intent. The rate of secondary resection was 66.3% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 59.5% in the CT plus CEA arm, 50.7% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 40.9% with standard imaging and no CEA (P = .0035).

The rates were similar among the 83 patients with recurrence after initial treatment for rectal cancer, but the between-arm differences were not significant. The rate of secondary resection with curative intent was 57.9% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 47.8% in the CT plus CEA arm, 55% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 42.9% with standard imaging and no CEA.

The research is ongoing, and the team expects to report on secondary outcomes and ancillary studies of circulating tumor DNA, among other things, in 2021.

The study is being funded by the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive. Dr. Lepage disclosed ties with Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Servier, and AAA. Dr. Price disclosed institutional research funding from Amgen and being an uncompensated adviser to Pierre-Fabre and Merck.

SOURCE: Lepage C et al. ESMO 2020, Abstract 398O.

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.

There were 356 recurrences in patients initially treated for colon cancer. CEA surveillance with or without CT scan was associated with an increased incidence of secondary resection with curative intent. The rate of secondary resection was 66.3% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 59.5% in the CT plus CEA arm, 50.7% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 40.9% with standard imaging and no CEA (P = .0035).

The rates were similar among the 83 patients with recurrence after initial treatment for rectal cancer, but the between-arm differences were not significant. The rate of secondary resection with curative intent was 57.9% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 47.8% in the CT plus CEA arm, 55% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 42.9% with standard imaging and no CEA.

The research is ongoing, and the team expects to report on secondary outcomes and ancillary studies of circulating tumor DNA, among other things, in 2021.

The study is being funded by the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive. Dr. Lepage disclosed ties with Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Servier, and AAA. Dr. Price disclosed institutional research funding from Amgen and being an uncompensated adviser to Pierre-Fabre and Merck.

SOURCE: Lepage C et al. ESMO 2020, Abstract 398O.

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.

There were 356 recurrences in patients initially treated for colon cancer. CEA surveillance with or without CT scan was associated with an increased incidence of secondary resection with curative intent. The rate of secondary resection was 66.3% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 59.5% in the CT plus CEA arm, 50.7% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 40.9% with standard imaging and no CEA (P = .0035).

The rates were similar among the 83 patients with recurrence after initial treatment for rectal cancer, but the between-arm differences were not significant. The rate of secondary resection with curative intent was 57.9% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 47.8% in the CT plus CEA arm, 55% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 42.9% with standard imaging and no CEA.

The research is ongoing, and the team expects to report on secondary outcomes and ancillary studies of circulating tumor DNA, among other things, in 2021.

The study is being funded by the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive. Dr. Lepage disclosed ties with Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Servier, and AAA. Dr. Price disclosed institutional research funding from Amgen and being an uncompensated adviser to Pierre-Fabre and Merck.

SOURCE: Lepage C et al. ESMO 2020, Abstract 398O.

FROM ESMO 2020

Trends in Colorectal Cancer Survival by Sidedness and Age in the Veterans Health Administration 2000 – 2017

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for about 10% of all cancers in the VA. Three-year survival is associated with both age at diagnosis and CRC stage. Yet, the minority of cases are detected at an early stage and the overall incidence of cancer in the VA patient population is forecast to rise. CRC survival and pathogenesis differ by tumor location Increases in CRC cases in individuals younger than fifty-years-of age and at more advanced stages have been reported in large, U.S. population-based cohorts (Meester et al., 2019). Here, we present a preliminary investigation of these trends amongst CRC patients in the VA.

METHODS: Briefly, a cohort of veteran patients (n = 40,951) was identified from 2000 – 2017 using the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR). We required all included patients to have a histologically-confirmed case of CRC as consistent with previous studies (Zullig et al., 2016) and only one registry entry. We constructed Kaplan- Meier curves and created a Cox-Proportional Hazards model to examine survival. Additional filtering by age at the date of diagnosis was used to identify patients between ages 40 and 49 and tumor location as abstracted in the VACCR. Regression analysis was used to examine trends in stage at diagnosis and in those between aged 40 and 49.

RESULTS: Our findings indicate that proximal (rightsided) colon cancer is associated with poorer survival than distal (left-sided), consistent with previous findings. During this time period, 3% of the cohort or 1,249 cases were diagnosed amongst individuals of ages 40 – 49. Regression analysis indicated differences in trends amongst VHA patients younger than fifty years of age and in stage at diagnosis. Though, the time period of this study was shorter than those previously published.

CONCLUSION: Further work is underway to identify the sources of these differences in survivorship in VHA patients, including the analysis of therapeutic regimens. This work was performed under R&D and IRB protocols reviewed approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System.

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for about 10% of all cancers in the VA. Three-year survival is associated with both age at diagnosis and CRC stage. Yet, the minority of cases are detected at an early stage and the overall incidence of cancer in the VA patient population is forecast to rise. CRC survival and pathogenesis differ by tumor location Increases in CRC cases in individuals younger than fifty-years-of age and at more advanced stages have been reported in large, U.S. population-based cohorts (Meester et al., 2019). Here, we present a preliminary investigation of these trends amongst CRC patients in the VA.

METHODS: Briefly, a cohort of veteran patients (n = 40,951) was identified from 2000 – 2017 using the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR). We required all included patients to have a histologically-confirmed case of CRC as consistent with previous studies (Zullig et al., 2016) and only one registry entry. We constructed Kaplan- Meier curves and created a Cox-Proportional Hazards model to examine survival. Additional filtering by age at the date of diagnosis was used to identify patients between ages 40 and 49 and tumor location as abstracted in the VACCR. Regression analysis was used to examine trends in stage at diagnosis and in those between aged 40 and 49.

RESULTS: Our findings indicate that proximal (rightsided) colon cancer is associated with poorer survival than distal (left-sided), consistent with previous findings. During this time period, 3% of the cohort or 1,249 cases were diagnosed amongst individuals of ages 40 – 49. Regression analysis indicated differences in trends amongst VHA patients younger than fifty years of age and in stage at diagnosis. Though, the time period of this study was shorter than those previously published.

CONCLUSION: Further work is underway to identify the sources of these differences in survivorship in VHA patients, including the analysis of therapeutic regimens. This work was performed under R&D and IRB protocols reviewed approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System.

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for about 10% of all cancers in the VA. Three-year survival is associated with both age at diagnosis and CRC stage. Yet, the minority of cases are detected at an early stage and the overall incidence of cancer in the VA patient population is forecast to rise. CRC survival and pathogenesis differ by tumor location Increases in CRC cases in individuals younger than fifty-years-of age and at more advanced stages have been reported in large, U.S. population-based cohorts (Meester et al., 2019). Here, we present a preliminary investigation of these trends amongst CRC patients in the VA.

METHODS: Briefly, a cohort of veteran patients (n = 40,951) was identified from 2000 – 2017 using the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR). We required all included patients to have a histologically-confirmed case of CRC as consistent with previous studies (Zullig et al., 2016) and only one registry entry. We constructed Kaplan- Meier curves and created a Cox-Proportional Hazards model to examine survival. Additional filtering by age at the date of diagnosis was used to identify patients between ages 40 and 49 and tumor location as abstracted in the VACCR. Regression analysis was used to examine trends in stage at diagnosis and in those between aged 40 and 49.

RESULTS: Our findings indicate that proximal (rightsided) colon cancer is associated with poorer survival than distal (left-sided), consistent with previous findings. During this time period, 3% of the cohort or 1,249 cases were diagnosed amongst individuals of ages 40 – 49. Regression analysis indicated differences in trends amongst VHA patients younger than fifty years of age and in stage at diagnosis. Though, the time period of this study was shorter than those previously published.

CONCLUSION: Further work is underway to identify the sources of these differences in survivorship in VHA patients, including the analysis of therapeutic regimens. This work was performed under R&D and IRB protocols reviewed approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System.

Transportation as a Barrier to Colorectal Cancer Care

PURPOSE: To describe the frequency of Veterans reporting and the factors associated with transportation barriers to or from colorectal cancer (CRC) care visits.

BACKGROUND: Transportation barriers limit access to healthcare services and contribute to suboptimal clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum. The relationship between patient-level characteristics, travel-related factors (e.g., mode of transportation), and transportation barriers among Veterans with CRC has been poorly described.

METHODS: Between November 2015 and September 2016, Veterans with incident stage I, II, or III CRC completed the Colorectal Cancer Patient Adherence to Survivorship Treatment survey to assess their perceived barriers to, and adherence with, recommended care. The survey measured: (1) demographics; (2) travel-related factors, including distance traveled to and convenience of care; and (3) perceived chaotic lifestyle (e.g., ability to organize, predictability of schedules) using the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. Veterans who reported “Always”, “Often”, or “Sometimes” experiencing difficulty with transportation to or from CRC care appointments were categorized as having transportation barriers.

DATA ANALYSIS: We assessed pairwise correlations between transportation barriers, travel-related factors, and chaotic lifestyle and used logistic regression to evaluate the association between the reporting of transportation barriers, distance traveled to care, and chaotic lifestyle.

RESULTS: Of the 115 Veterans included in this analysis, 21 (18%) reported transportation barriers to or from CRC care visits. A majority of Veterans who reported transportation barriers were previously married (62%), traveled more than 20 miles for care (81%), and had a chaotic lifestyle (57%). Distance to care was not strongly correlated with reporting transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.12, p=0.19), whereas a chaotic lifestyle was both positively and significantly correlated with experiencing transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.22, p=0.02). Results from the logistic regression model modestly supported the findings from the pairwise correlations, but were not statistically significant.

IMPLICATIONS: Transportation is an important barrier to or from CRC care visits, especially among Veterans who experience chaotic lifestyles. Identifying Veterans with chaotic lifestyles would allow for timely intervention (e.g., patient navigation, organizational skills training), which could result in the potential modification of observed risk factors and thus, support access to healthcare services and treatment across the cancer care continuum.

PURPOSE: To describe the frequency of Veterans reporting and the factors associated with transportation barriers to or from colorectal cancer (CRC) care visits.

BACKGROUND: Transportation barriers limit access to healthcare services and contribute to suboptimal clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum. The relationship between patient-level characteristics, travel-related factors (e.g., mode of transportation), and transportation barriers among Veterans with CRC has been poorly described.

METHODS: Between November 2015 and September 2016, Veterans with incident stage I, II, or III CRC completed the Colorectal Cancer Patient Adherence to Survivorship Treatment survey to assess their perceived barriers to, and adherence with, recommended care. The survey measured: (1) demographics; (2) travel-related factors, including distance traveled to and convenience of care; and (3) perceived chaotic lifestyle (e.g., ability to organize, predictability of schedules) using the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. Veterans who reported “Always”, “Often”, or “Sometimes” experiencing difficulty with transportation to or from CRC care appointments were categorized as having transportation barriers.

DATA ANALYSIS: We assessed pairwise correlations between transportation barriers, travel-related factors, and chaotic lifestyle and used logistic regression to evaluate the association between the reporting of transportation barriers, distance traveled to care, and chaotic lifestyle.

RESULTS: Of the 115 Veterans included in this analysis, 21 (18%) reported transportation barriers to or from CRC care visits. A majority of Veterans who reported transportation barriers were previously married (62%), traveled more than 20 miles for care (81%), and had a chaotic lifestyle (57%). Distance to care was not strongly correlated with reporting transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.12, p=0.19), whereas a chaotic lifestyle was both positively and significantly correlated with experiencing transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.22, p=0.02). Results from the logistic regression model modestly supported the findings from the pairwise correlations, but were not statistically significant.

IMPLICATIONS: Transportation is an important barrier to or from CRC care visits, especially among Veterans who experience chaotic lifestyles. Identifying Veterans with chaotic lifestyles would allow for timely intervention (e.g., patient navigation, organizational skills training), which could result in the potential modification of observed risk factors and thus, support access to healthcare services and treatment across the cancer care continuum.

PURPOSE: To describe the frequency of Veterans reporting and the factors associated with transportation barriers to or from colorectal cancer (CRC) care visits.

BACKGROUND: Transportation barriers limit access to healthcare services and contribute to suboptimal clinical outcomes across the cancer care continuum. The relationship between patient-level characteristics, travel-related factors (e.g., mode of transportation), and transportation barriers among Veterans with CRC has been poorly described.

METHODS: Between November 2015 and September 2016, Veterans with incident stage I, II, or III CRC completed the Colorectal Cancer Patient Adherence to Survivorship Treatment survey to assess their perceived barriers to, and adherence with, recommended care. The survey measured: (1) demographics; (2) travel-related factors, including distance traveled to and convenience of care; and (3) perceived chaotic lifestyle (e.g., ability to organize, predictability of schedules) using the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. Veterans who reported “Always”, “Often”, or “Sometimes” experiencing difficulty with transportation to or from CRC care appointments were categorized as having transportation barriers.

DATA ANALYSIS: We assessed pairwise correlations between transportation barriers, travel-related factors, and chaotic lifestyle and used logistic regression to evaluate the association between the reporting of transportation barriers, distance traveled to care, and chaotic lifestyle.

RESULTS: Of the 115 Veterans included in this analysis, 21 (18%) reported transportation barriers to or from CRC care visits. A majority of Veterans who reported transportation barriers were previously married (62%), traveled more than 20 miles for care (81%), and had a chaotic lifestyle (57%). Distance to care was not strongly correlated with reporting transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.12, p=0.19), whereas a chaotic lifestyle was both positively and significantly correlated with experiencing transportation barriers (Spearman’s ρ=0.22, p=0.02). Results from the logistic regression model modestly supported the findings from the pairwise correlations, but were not statistically significant.

IMPLICATIONS: Transportation is an important barrier to or from CRC care visits, especially among Veterans who experience chaotic lifestyles. Identifying Veterans with chaotic lifestyles would allow for timely intervention (e.g., patient navigation, organizational skills training), which could result in the potential modification of observed risk factors and thus, support access to healthcare services and treatment across the cancer care continuum.

The Association of Modifiable Baseline Risk Factors with a Diagnosis of Advanced Neoplasia Among an Asymptomatic Veteran Population

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines generally recommend healthy lifestyle choices for cancer prevention. However, studies have shown inconsistent associations between various risk factors and advanced neoplasia (AN) development. AIM: To identify potentially modifiable baseline dietary and lifestyle risk factors associated with AN among an asymptomatic Veteran population, while accounting for prior colonoscopic findings and varying surveillance intensity.

METHODS: We used data from a prospective colonoscopy screening study collected by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. From 1994 to 1997, 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75 received a baseline colonoscopy screening, at which time they selfreported dietary and lifestyle information. Veterans were subsequently assigned to colonoscopy surveillance regimens and followed for 10 years. AN was defined as invasive CRC or any adenoma ≥1 cm, or with villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia. To detect associations with AN diagnosis, we utilized a longitudinal joint model with two sub-models. A multivariate logistic regression modeled the longitudinal probability of AN, while a time-to-event process adjusted for survival. Here we focus on the multivariate logistic regression, representing associations of dietary and lifestyle risk factors with the odds of being diagnosed with AN.

RESULTS: Of the 3,121 Veterans, 1,915 received at least one colonoscopy following baseline screening. Among the 1,915, we detected a significant positive association with AN for current daily smokers (odds ratio (OR) 1.43, 95% CI: 1.02-2.01) compared to those with prior or no history. We found a protective effect for each 100 IU of dietary vitamin D consumed (OR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.95-0.99). We did not detect any significant associations with BMI, red meat consumption, or physical activity. We found that African American race had a lower odds of AN compared to Caucasian race (OR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.32-0.97).

CONCLUSIONS: We identified smoking status and vitamin D consumption as potentially modifiable baseline risk factors associated with AN development. While these results suggest possible points of intervention and targeted screening, more evidence is required across more diverse populations. Future efforts should focus on understanding changes in such risk factors on associations with AN for patients over time. Finally, racial differences in AN incidence merit further investigation.

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines generally recommend healthy lifestyle choices for cancer prevention. However, studies have shown inconsistent associations between various risk factors and advanced neoplasia (AN) development. AIM: To identify potentially modifiable baseline dietary and lifestyle risk factors associated with AN among an asymptomatic Veteran population, while accounting for prior colonoscopic findings and varying surveillance intensity.

METHODS: We used data from a prospective colonoscopy screening study collected by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. From 1994 to 1997, 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75 received a baseline colonoscopy screening, at which time they selfreported dietary and lifestyle information. Veterans were subsequently assigned to colonoscopy surveillance regimens and followed for 10 years. AN was defined as invasive CRC or any adenoma ≥1 cm, or with villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia. To detect associations with AN diagnosis, we utilized a longitudinal joint model with two sub-models. A multivariate logistic regression modeled the longitudinal probability of AN, while a time-to-event process adjusted for survival. Here we focus on the multivariate logistic regression, representing associations of dietary and lifestyle risk factors with the odds of being diagnosed with AN.

RESULTS: Of the 3,121 Veterans, 1,915 received at least one colonoscopy following baseline screening. Among the 1,915, we detected a significant positive association with AN for current daily smokers (odds ratio (OR) 1.43, 95% CI: 1.02-2.01) compared to those with prior or no history. We found a protective effect for each 100 IU of dietary vitamin D consumed (OR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.95-0.99). We did not detect any significant associations with BMI, red meat consumption, or physical activity. We found that African American race had a lower odds of AN compared to Caucasian race (OR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.32-0.97).

CONCLUSIONS: We identified smoking status and vitamin D consumption as potentially modifiable baseline risk factors associated with AN development. While these results suggest possible points of intervention and targeted screening, more evidence is required across more diverse populations. Future efforts should focus on understanding changes in such risk factors on associations with AN for patients over time. Finally, racial differences in AN incidence merit further investigation.

BACKGROUND: Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines generally recommend healthy lifestyle choices for cancer prevention. However, studies have shown inconsistent associations between various risk factors and advanced neoplasia (AN) development. AIM: To identify potentially modifiable baseline dietary and lifestyle risk factors associated with AN among an asymptomatic Veteran population, while accounting for prior colonoscopic findings and varying surveillance intensity.

METHODS: We used data from a prospective colonoscopy screening study collected by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. From 1994 to 1997, 3,121 asymptomatic Veterans aged 50-75 received a baseline colonoscopy screening, at which time they selfreported dietary and lifestyle information. Veterans were subsequently assigned to colonoscopy surveillance regimens and followed for 10 years. AN was defined as invasive CRC or any adenoma ≥1 cm, or with villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia. To detect associations with AN diagnosis, we utilized a longitudinal joint model with two sub-models. A multivariate logistic regression modeled the longitudinal probability of AN, while a time-to-event process adjusted for survival. Here we focus on the multivariate logistic regression, representing associations of dietary and lifestyle risk factors with the odds of being diagnosed with AN.

RESULTS: Of the 3,121 Veterans, 1,915 received at least one colonoscopy following baseline screening. Among the 1,915, we detected a significant positive association with AN for current daily smokers (odds ratio (OR) 1.43, 95% CI: 1.02-2.01) compared to those with prior or no history. We found a protective effect for each 100 IU of dietary vitamin D consumed (OR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.95-0.99). We did not detect any significant associations with BMI, red meat consumption, or physical activity. We found that African American race had a lower odds of AN compared to Caucasian race (OR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.32-0.97).

CONCLUSIONS: We identified smoking status and vitamin D consumption as potentially modifiable baseline risk factors associated with AN development. While these results suggest possible points of intervention and targeted screening, more evidence is required across more diverse populations. Future efforts should focus on understanding changes in such risk factors on associations with AN for patients over time. Finally, racial differences in AN incidence merit further investigation.

Screening Colonoscopy Findings Are Associated With Non-Colorectal Cancer Mortality

PURPOSE: Examine whether baseline colonoscopy findings are associated with non-Colorectal Cancer (CRC) mortality in a Veteran screening population.

BACKGROUND: Although screening colonoscopy findings are associated with future risk of CRC mortality, whether these findings are also associated with non- CRC mortality remains unknown.

METHODS: The Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #380 cohort is comprised of 3,121 Veterans age 50-75 who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-97. Veterans were followed for 10 years or death, as verified in electronic medical records. Those who died from CRC-specific causes were excluded from this analysis (n=18, 0.6%). Hazard ratios (HR) for risk factors on non-CRC mortality were calculated by Cox Proportional Hazard model, adjusting for demographics, baseline comorbidities, and lifestyle factors. Information on comorbidities, family history, diet, physical activity, and medications were obtained from self-reported questionnaires at baseline.

RESULTS: Of the included 3,103 Veterans, most were male (n=3,021, 96.8%), white (n=2,609, 83.6%), with a mean age of 62.9. During the 10-year follow-up period, 837 (27.0%) Veterans died from non-CRC causes. The risk of non-CRC mortality was higher in Veterans with ≥3 small adenomas (HR 1.45, p=0.02), advanced adenomas (HR 1.34, p=0.04), or CRC (HR 3.00, =0.05) on baseline colonoscopy when compared to Veterans without neoplasia. Additionally, increasing age (HR 1.07, <0.001), modified Charlson score (HR 1.57 for 3-4 points, <0.001, compared to 0-2 points) and current smoking (HR 2.09, <0.001, compared to former and non-smokers) were associated with higher non-CRC mortality. On the other hand, increasing physical activity (HR 0.88, <0.001), family history of CRC (HR 0.75, =0.02), and increased BMI (HR 0.73-0.75, <0.01) were associated with reduced non-CRC mortality. Neither race, NSAID use (including aspirin), or dietary factors impacted non-CRC mortality.

CONCLUSIONS: In a Veteran CRC screening population, we found that high-risk adenomas or CRC on baseline colonoscopy were independently associated with increased non-CRC mortality within 10 years. Future work will examine the cause-specific factors associated with non-CRC mortality in these groups to 1) identify potential high-yield strategies for tailored non-CRC mortality risk reduction during CRC screening, and 2) better determine when competing risks of non-CRC mortality outweigh the benefit of follow up colonoscopy.

PURPOSE: Examine whether baseline colonoscopy findings are associated with non-Colorectal Cancer (CRC) mortality in a Veteran screening population.

BACKGROUND: Although screening colonoscopy findings are associated with future risk of CRC mortality, whether these findings are also associated with non- CRC mortality remains unknown.

METHODS: The Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #380 cohort is comprised of 3,121 Veterans age 50-75 who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-97. Veterans were followed for 10 years or death, as verified in electronic medical records. Those who died from CRC-specific causes were excluded from this analysis (n=18, 0.6%). Hazard ratios (HR) for risk factors on non-CRC mortality were calculated by Cox Proportional Hazard model, adjusting for demographics, baseline comorbidities, and lifestyle factors. Information on comorbidities, family history, diet, physical activity, and medications were obtained from self-reported questionnaires at baseline.

RESULTS: Of the included 3,103 Veterans, most were male (n=3,021, 96.8%), white (n=2,609, 83.6%), with a mean age of 62.9. During the 10-year follow-up period, 837 (27.0%) Veterans died from non-CRC causes. The risk of non-CRC mortality was higher in Veterans with ≥3 small adenomas (HR 1.45, p=0.02), advanced adenomas (HR 1.34, p=0.04), or CRC (HR 3.00, =0.05) on baseline colonoscopy when compared to Veterans without neoplasia. Additionally, increasing age (HR 1.07, <0.001), modified Charlson score (HR 1.57 for 3-4 points, <0.001, compared to 0-2 points) and current smoking (HR 2.09, <0.001, compared to former and non-smokers) were associated with higher non-CRC mortality. On the other hand, increasing physical activity (HR 0.88, <0.001), family history of CRC (HR 0.75, =0.02), and increased BMI (HR 0.73-0.75, <0.01) were associated with reduced non-CRC mortality. Neither race, NSAID use (including aspirin), or dietary factors impacted non-CRC mortality.

CONCLUSIONS: In a Veteran CRC screening population, we found that high-risk adenomas or CRC on baseline colonoscopy were independently associated with increased non-CRC mortality within 10 years. Future work will examine the cause-specific factors associated with non-CRC mortality in these groups to 1) identify potential high-yield strategies for tailored non-CRC mortality risk reduction during CRC screening, and 2) better determine when competing risks of non-CRC mortality outweigh the benefit of follow up colonoscopy.

PURPOSE: Examine whether baseline colonoscopy findings are associated with non-Colorectal Cancer (CRC) mortality in a Veteran screening population.

BACKGROUND: Although screening colonoscopy findings are associated with future risk of CRC mortality, whether these findings are also associated with non- CRC mortality remains unknown.

METHODS: The Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #380 cohort is comprised of 3,121 Veterans age 50-75 who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-97. Veterans were followed for 10 years or death, as verified in electronic medical records. Those who died from CRC-specific causes were excluded from this analysis (n=18, 0.6%). Hazard ratios (HR) for risk factors on non-CRC mortality were calculated by Cox Proportional Hazard model, adjusting for demographics, baseline comorbidities, and lifestyle factors. Information on comorbidities, family history, diet, physical activity, and medications were obtained from self-reported questionnaires at baseline.

RESULTS: Of the included 3,103 Veterans, most were male (n=3,021, 96.8%), white (n=2,609, 83.6%), with a mean age of 62.9. During the 10-year follow-up period, 837 (27.0%) Veterans died from non-CRC causes. The risk of non-CRC mortality was higher in Veterans with ≥3 small adenomas (HR 1.45, p=0.02), advanced adenomas (HR 1.34, p=0.04), or CRC (HR 3.00, =0.05) on baseline colonoscopy when compared to Veterans without neoplasia. Additionally, increasing age (HR 1.07, <0.001), modified Charlson score (HR 1.57 for 3-4 points, <0.001, compared to 0-2 points) and current smoking (HR 2.09, <0.001, compared to former and non-smokers) were associated with higher non-CRC mortality. On the other hand, increasing physical activity (HR 0.88, <0.001), family history of CRC (HR 0.75, =0.02), and increased BMI (HR 0.73-0.75, <0.01) were associated with reduced non-CRC mortality. Neither race, NSAID use (including aspirin), or dietary factors impacted non-CRC mortality.

CONCLUSIONS: In a Veteran CRC screening population, we found that high-risk adenomas or CRC on baseline colonoscopy were independently associated with increased non-CRC mortality within 10 years. Future work will examine the cause-specific factors associated with non-CRC mortality in these groups to 1) identify potential high-yield strategies for tailored non-CRC mortality risk reduction during CRC screening, and 2) better determine when competing risks of non-CRC mortality outweigh the benefit of follow up colonoscopy.

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Surveillance Utilizing Telehealth Technology in the COVID Era

PURPOSE: Determine the feasibility of telehealth as a safe and effective modality for CRC surveillance in the post-COVID era.

BACKGROUND: CRC survivors require routine cancer surveillance for a minimum of five years as directed by NCCN Survivorship guidelines. The onset of COVID inMarch 2020 severely limited the ability to have face to face encounters with New Mexico Veterans. Combining social distancing requirements and generalized fear among Veterans made it difficult to maintain routine face to face surveillance.

METHODS: Thirty CRC survivors in the surveillance phase were evaluated using VA Video Connect (VVC) technology. Established CRC Survivorship surveillance notes were completed during the VVC visit. The documented components included COVID screening, general and CRC focused symptomatology, psychological stress, physical exam, laboratory, and radiology studies. All surveillance questions were completed. Veterans were asked to complete a self-exam with video visualization of non-sensitive anatomical regions. Digital rectal exam was deferred. Lab and radiology studies were ordered to be done at a later time in VA/CBOC. To assist with poor hearing or visual acuity, VVC communication was enhanced by utilizing screen sharing with the Veteran to review the most recent lab/radiology results, as well as PowerPoint presentations to explain anatomy, disease process, and plan for continued surveillance. Veterans were assessed for level of anxiety regarding COVID and inability to seek routine medical care.

RESULTS: Veterans and their families were extremely satisfied with the ability to “see” a provider without incurring the risk of exposure and the cost of traveling with the economic hardship of COVID. As a result, the VA did not incur travel fees for remote Veterans. VVC improved access to Veteran specialty care and decreased overall anxiety and concerns regarding possible delayed diagnosis for cancer recurrence due to missed clinic appointments.

CONCLUSIONS: VVC is a viable option for CRC surveillance, however the Veteran still requires interval physical exam, labs, and imaging. A feasible option is to alternate in-person face to face visits with VVC appointments as a means to meet the expected long-term requirements for social distancing while still providing the vital care and reassurance to our Veterans.

PURPOSE: Determine the feasibility of telehealth as a safe and effective modality for CRC surveillance in the post-COVID era.

BACKGROUND: CRC survivors require routine cancer surveillance for a minimum of five years as directed by NCCN Survivorship guidelines. The onset of COVID inMarch 2020 severely limited the ability to have face to face encounters with New Mexico Veterans. Combining social distancing requirements and generalized fear among Veterans made it difficult to maintain routine face to face surveillance.

METHODS: Thirty CRC survivors in the surveillance phase were evaluated using VA Video Connect (VVC) technology. Established CRC Survivorship surveillance notes were completed during the VVC visit. The documented components included COVID screening, general and CRC focused symptomatology, psychological stress, physical exam, laboratory, and radiology studies. All surveillance questions were completed. Veterans were asked to complete a self-exam with video visualization of non-sensitive anatomical regions. Digital rectal exam was deferred. Lab and radiology studies were ordered to be done at a later time in VA/CBOC. To assist with poor hearing or visual acuity, VVC communication was enhanced by utilizing screen sharing with the Veteran to review the most recent lab/radiology results, as well as PowerPoint presentations to explain anatomy, disease process, and plan for continued surveillance. Veterans were assessed for level of anxiety regarding COVID and inability to seek routine medical care.

RESULTS: Veterans and their families were extremely satisfied with the ability to “see” a provider without incurring the risk of exposure and the cost of traveling with the economic hardship of COVID. As a result, the VA did not incur travel fees for remote Veterans. VVC improved access to Veteran specialty care and decreased overall anxiety and concerns regarding possible delayed diagnosis for cancer recurrence due to missed clinic appointments.

CONCLUSIONS: VVC is a viable option for CRC surveillance, however the Veteran still requires interval physical exam, labs, and imaging. A feasible option is to alternate in-person face to face visits with VVC appointments as a means to meet the expected long-term requirements for social distancing while still providing the vital care and reassurance to our Veterans.

PURPOSE: Determine the feasibility of telehealth as a safe and effective modality for CRC surveillance in the post-COVID era.

BACKGROUND: CRC survivors require routine cancer surveillance for a minimum of five years as directed by NCCN Survivorship guidelines. The onset of COVID inMarch 2020 severely limited the ability to have face to face encounters with New Mexico Veterans. Combining social distancing requirements and generalized fear among Veterans made it difficult to maintain routine face to face surveillance.

METHODS: Thirty CRC survivors in the surveillance phase were evaluated using VA Video Connect (VVC) technology. Established CRC Survivorship surveillance notes were completed during the VVC visit. The documented components included COVID screening, general and CRC focused symptomatology, psychological stress, physical exam, laboratory, and radiology studies. All surveillance questions were completed. Veterans were asked to complete a self-exam with video visualization of non-sensitive anatomical regions. Digital rectal exam was deferred. Lab and radiology studies were ordered to be done at a later time in VA/CBOC. To assist with poor hearing or visual acuity, VVC communication was enhanced by utilizing screen sharing with the Veteran to review the most recent lab/radiology results, as well as PowerPoint presentations to explain anatomy, disease process, and plan for continued surveillance. Veterans were assessed for level of anxiety regarding COVID and inability to seek routine medical care.

RESULTS: Veterans and their families were extremely satisfied with the ability to “see” a provider without incurring the risk of exposure and the cost of traveling with the economic hardship of COVID. As a result, the VA did not incur travel fees for remote Veterans. VVC improved access to Veteran specialty care and decreased overall anxiety and concerns regarding possible delayed diagnosis for cancer recurrence due to missed clinic appointments.

CONCLUSIONS: VVC is a viable option for CRC surveillance, however the Veteran still requires interval physical exam, labs, and imaging. A feasible option is to alternate in-person face to face visits with VVC appointments as a means to meet the expected long-term requirements for social distancing while still providing the vital care and reassurance to our Veterans.

Atypical Cardiac Metastasis From a Typical Rectal Cancer

BACKGROUND: The heart is an unusual site of metastasis from any malignancy. The pericardium is the most frequently involved site of cardiac metastasis. Myocardial metastasis is rare and metastasis only to heart without evidence of spread anywhere else is extremely rare. Here we present a case of rectal cancer with metastasis only to heart.

CASE REPORT: A 64-year-old man was found to have a large ulcerated mass in the upper rectum, 15cm above the anal verge during colonoscopy. Biopsy of the mass revealed poorly differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma. After 5 weeks of neo adjuvant capecitabine with concurrent radiation, he underwent robotic low anterior resection (LAR) with coloanal anastomosis with loop ileostomy. Pathology revealed 5cm poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of rectum invading through muscularis propria with 7/17 lymph nodes and margins involved with adenocarcinoma. He was staged as ypT3pN2bM0 (Stage IIIC, AJCC 8th edition, 2017). Adjuvant therapy was delayed until 12 weeks from surgery due to wound dehiscence/infection. After 5 cycles of adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin, a follow up contrast CT chest/abdomen/pelvis revealed 2.3cm mass extending from pericardium to myocardium. Transesophageal echocardiogram(TEE) and cardiac MRI revealed 2 separate masses(1cm and 2cm) in the right ventricle (RV) free wall projecting into RV cavity concerning for free wall metastases. After 3 weeks, he presented to ED with shortness of breath. Transthoracic echocardiogram(TTE) showed large pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade. 1250ml of pericardial fluid was removed by pericardiocentesis and cytology revealed metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. CT chest/abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast did not show any other site of metastasis. He was started on systemic chemotherapy with Fluorouracil and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI). He has tolerated FOLFIRI for a year without recurrence of pericardial effusion.

CONCLUSION: Most cardiac metastases are associated with widely metastatic disease, but this case is unique in having only cardiac metastasis from a previously resected rectal adenocarcinoma. Although often clinically silent, cardiac metastases should be considered in any patient with cancer and new cardiac symptoms. TTE is the initial imaging test but TEE, Cardiac CT and Cardiac MRI may help further characterize and delineate the extent of cardiac disease. A multidisciplinary team to evaluate and manage the patient with cardiac metastasis is recommended.

BACKGROUND: The heart is an unusual site of metastasis from any malignancy. The pericardium is the most frequently involved site of cardiac metastasis. Myocardial metastasis is rare and metastasis only to heart without evidence of spread anywhere else is extremely rare. Here we present a case of rectal cancer with metastasis only to heart.

CASE REPORT: A 64-year-old man was found to have a large ulcerated mass in the upper rectum, 15cm above the anal verge during colonoscopy. Biopsy of the mass revealed poorly differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma. After 5 weeks of neo adjuvant capecitabine with concurrent radiation, he underwent robotic low anterior resection (LAR) with coloanal anastomosis with loop ileostomy. Pathology revealed 5cm poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of rectum invading through muscularis propria with 7/17 lymph nodes and margins involved with adenocarcinoma. He was staged as ypT3pN2bM0 (Stage IIIC, AJCC 8th edition, 2017). Adjuvant therapy was delayed until 12 weeks from surgery due to wound dehiscence/infection. After 5 cycles of adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin, a follow up contrast CT chest/abdomen/pelvis revealed 2.3cm mass extending from pericardium to myocardium. Transesophageal echocardiogram(TEE) and cardiac MRI revealed 2 separate masses(1cm and 2cm) in the right ventricle (RV) free wall projecting into RV cavity concerning for free wall metastases. After 3 weeks, he presented to ED with shortness of breath. Transthoracic echocardiogram(TTE) showed large pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade. 1250ml of pericardial fluid was removed by pericardiocentesis and cytology revealed metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. CT chest/abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast did not show any other site of metastasis. He was started on systemic chemotherapy with Fluorouracil and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI). He has tolerated FOLFIRI for a year without recurrence of pericardial effusion.

CONCLUSION: Most cardiac metastases are associated with widely metastatic disease, but this case is unique in having only cardiac metastasis from a previously resected rectal adenocarcinoma. Although often clinically silent, cardiac metastases should be considered in any patient with cancer and new cardiac symptoms. TTE is the initial imaging test but TEE, Cardiac CT and Cardiac MRI may help further characterize and delineate the extent of cardiac disease. A multidisciplinary team to evaluate and manage the patient with cardiac metastasis is recommended.

BACKGROUND: The heart is an unusual site of metastasis from any malignancy. The pericardium is the most frequently involved site of cardiac metastasis. Myocardial metastasis is rare and metastasis only to heart without evidence of spread anywhere else is extremely rare. Here we present a case of rectal cancer with metastasis only to heart.

CASE REPORT: A 64-year-old man was found to have a large ulcerated mass in the upper rectum, 15cm above the anal verge during colonoscopy. Biopsy of the mass revealed poorly differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma. After 5 weeks of neo adjuvant capecitabine with concurrent radiation, he underwent robotic low anterior resection (LAR) with coloanal anastomosis with loop ileostomy. Pathology revealed 5cm poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of rectum invading through muscularis propria with 7/17 lymph nodes and margins involved with adenocarcinoma. He was staged as ypT3pN2bM0 (Stage IIIC, AJCC 8th edition, 2017). Adjuvant therapy was delayed until 12 weeks from surgery due to wound dehiscence/infection. After 5 cycles of adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin, a follow up contrast CT chest/abdomen/pelvis revealed 2.3cm mass extending from pericardium to myocardium. Transesophageal echocardiogram(TEE) and cardiac MRI revealed 2 separate masses(1cm and 2cm) in the right ventricle (RV) free wall projecting into RV cavity concerning for free wall metastases. After 3 weeks, he presented to ED with shortness of breath. Transthoracic echocardiogram(TTE) showed large pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade. 1250ml of pericardial fluid was removed by pericardiocentesis and cytology revealed metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. CT chest/abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast did not show any other site of metastasis. He was started on systemic chemotherapy with Fluorouracil and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI). He has tolerated FOLFIRI for a year without recurrence of pericardial effusion.

CONCLUSION: Most cardiac metastases are associated with widely metastatic disease, but this case is unique in having only cardiac metastasis from a previously resected rectal adenocarcinoma. Although often clinically silent, cardiac metastases should be considered in any patient with cancer and new cardiac symptoms. TTE is the initial imaging test but TEE, Cardiac CT and Cardiac MRI may help further characterize and delineate the extent of cardiac disease. A multidisciplinary team to evaluate and manage the patient with cardiac metastasis is recommended.

Antihypertensives linked to reduced risk of colorectal cancer

Treating hypertension with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) was associated with a reduced risk for colorectal cancer, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

However, another study reported just over a year ago suggested that ACE inhibitors, but not ARBs, are associated with an increased risk for lung cancer. An expert approached for comment emphasized that both studies are observational, and, as such, they only show an association, not causation.

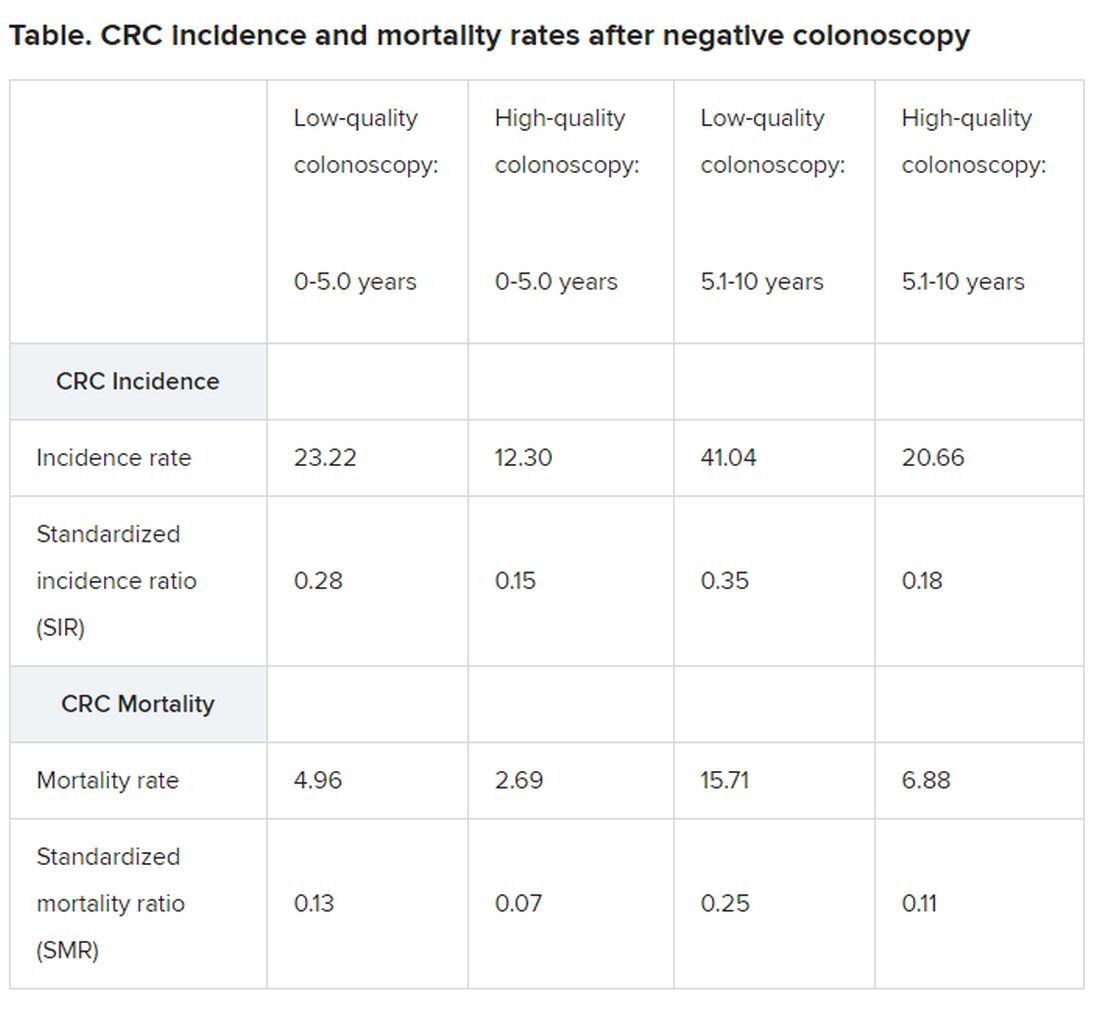

In this latest study, published online July 6 in the journal Hypertension, the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was associated with a 22% lower risk for colorectal cancer developing within 3 years after a negative baseline colonoscopy.

This is the largest study to date, with a cohort of more than 185,000 patients, to suggest a significant protective effect for these two common antihypertensive medications, the authors note. The risk of developing colorectal cancer decreased with longer duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB use, with a 5% reduction in adjusted hazard ratio risk for each year of use. However, this effect was limited to patients who had negative colonoscopies within a 3-year period and did not extend beyond that point.

Lead author Wai K. Leung, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Hong Kong, explained that they are not advising patients to take ACE inhibitors simply to prevent cancer. “Unlike aspirin and statins, the potential chemopreventive role of ACE inhibitors on cancer has never been established,” he said in an interview. “The study findings may favor the use of ACE inhibitors in the treatment of hypertension, over many other antihypertensives, in some patients for preventing colorectal cancer.”

Increased or reduced risk?

There has been considerable debate about the potential carcinogenic effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, and the relationship with “various solid organ cancer risks have been unsettled,” the authors note. Studies have produced conflicting results – showing no overall cancer risk and a modestly increased overall cancer risk – associated with these agents.

A recent study reported that ACE inhibitors, as compared with ARBs, increased risk for lung cancer by 14%. The risk for lung cancer increased by 22% among those using ACE inhibitors for 5 years, and the risk peaked at 31% for patients who took ACE inhibitors for 10 years or longer.

The lead author of that lung cancer study, Laurent Azoulay, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal, offered some thoughts on the seemingly conflicting data now being reported showing a reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer.

“In a nutshell, this study has important methodologic issues that can explain the observed findings,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Azoulay pointed out that, in the univariate model, the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was associated with a 26% increased risk of colorectal cancer. “It is only after propensity score adjustment that the effect estimate reversed in the protective direction,” he pointed out. “However, the variables included in the propensity score model were measured in the same time window as the exposure, which can lead to an overadjustment bias and generate spurious findings.”

Another issue is that the study period did not begin at the time of the exposure, but rather at a distant point after treatment initiation – in this case, colorectal cancer screening. “As such, the authors excluded patients who were previously diagnosed with colorectal cancer prior to that point, which likely included patients exposed to ACE inhibitors/ARBs,” he said. “This approach can lead to the inclusion of the ‘survivors’ for whom the risk of developing colorectal cancer is lower.

“But certainly,” Dr. Azoulay added, “this possible association should be investigated using methodologically sound approaches.”

Take-home message for physicians

Another expert emphasized the observational nature of both studies. Raymond Townsend, MD, director of the Hypertension Program and a professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said: “First and foremost, these are observational studies and cannot make inference about causality; they can only show associations.”

He pointed out that, sometimes, associations are truly present, whereas at other times, there is bias or confounding that cannot be controlled for statistically because it is “unknown.” That said, the size of this latest study is a plus, and there is a reasonable follow-up period.

“The take-home [message] for practitioners is that there may be a benefit in keeping older people on ACE inhibitors on the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer if your last colonoscopy was negative,” Dr. Townsend, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

But there are some questions that remain unanswered regarding characteristics of the cohort, Dr. Townsend noted. “Who were the people having the colonoscopy in the first place? Were they a group at higher risk? Why were some on an ACE inhibitors/ARBs and many others not?”

There are other conclusions that clinicians can glean from this. “Make a choice of treatment for a patient based on your best estimate of what will lower their blood pressure and prevent hypertension-mediated organ damage,” said Dr. Townsend, who is also an American Heart Association volunteer expert. “Keep in mind that patients hear about these studies and read unreviewed blogs on the web and so have questions.”

He emphasized that it always comes back to two things. “One is that every treatment decision is inherently a risk-benefit scenario,” he said. “And second is that most of our patients are adults, and if they choose to not be treated for their hypertension despite our best advice and reasoning with them, relinquish control and let them proceed as they wish, offering to renegotiate in the future when and if they reconsider.”

Study details

In the latest study, Dr. Leung and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study and used data from an electronic health care database of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. A total of 187,897 individuals aged 40 years and older had undergone colonoscopy between 2005 and 2013 with a negative result and were included in the analysis.

The study’s primary outcome was colorectal cancer that was diagnosed between 6 and 36 months after undergoing colonoscopy, and the median age at colonoscopy was 60.6 years. Within this population, 30,856 patients (16.4%) used ACE inhibitors/ARBs.

Between 6 months and 3 years after undergoing colonoscopy, 854 cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed, with an incidence rate of 15.2 per 10,000 person-years. The median time between colonoscopy and diagnosis was 1.2 years.

ACE inhibitor/ARB users had a median duration of 3.3 years of use within the 5-year period before their colonoscopy. Within this group, there were 169 (0.55%) cases of colorectal cancer. On univariate analysis, the crude hazard ratio (HR) of colorectal cancer and ACE inhibitor/ARB use was 1.26 (P = .008), but on propensity score regression adjustment, the adjusted HR became 0.78.

The propensity score absolute reduction in risk for users was 3.2 per 10,000 person-years versus nonusers, and stratification by subsite showed an HR of 0.77 for distal cancers and 0.83 for proximal cancers.

In a subgroup analysis, the benefits of ACE inhibitors and ARBs were seen in patients aged 55 years or older (adjusted HR, 0.79) and in those with a history of colonic polyps (adjusted HR, 0.71).

The authors also assessed if there was an association between these medications and other types of cancer. On univariate analysis, usage was associated with an increased risk of lung and prostate cancer but lower risk of breast cancer. But after propensity score regression adjustment, the associations were no longer there.

The study was funded by the Health and Medical Research Fund of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Dr. Leung has received honorarium for attending advisory board meetings of AbbVie, Takeda, and Abbott Laboratories; coauthor Esther W. Chan has received funding support from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Takeda, Janssen (a division of Johnson & Johnson); Research Grants Council of Hong Kong; Narcotics Division, Security Bureau; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, all for work unrelated to the current study. None of the other authors have disclosed relevant financial relationships. Dr. Azoulay has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Townsend is employed by Penn Medicine.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating hypertension with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) was associated with a reduced risk for colorectal cancer, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

However, another study reported just over a year ago suggested that ACE inhibitors, but not ARBs, are associated with an increased risk for lung cancer. An expert approached for comment emphasized that both studies are observational, and, as such, they only show an association, not causation.

In this latest study, published online July 6 in the journal Hypertension, the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was associated with a 22% lower risk for colorectal cancer developing within 3 years after a negative baseline colonoscopy.

This is the largest study to date, with a cohort of more than 185,000 patients, to suggest a significant protective effect for these two common antihypertensive medications, the authors note. The risk of developing colorectal cancer decreased with longer duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB use, with a 5% reduction in adjusted hazard ratio risk for each year of use. However, this effect was limited to patients who had negative colonoscopies within a 3-year period and did not extend beyond that point.

Lead author Wai K. Leung, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Hong Kong, explained that they are not advising patients to take ACE inhibitors simply to prevent cancer. “Unlike aspirin and statins, the potential chemopreventive role of ACE inhibitors on cancer has never been established,” he said in an interview. “The study findings may favor the use of ACE inhibitors in the treatment of hypertension, over many other antihypertensives, in some patients for preventing colorectal cancer.”

Increased or reduced risk?

There has been considerable debate about the potential carcinogenic effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, and the relationship with “various solid organ cancer risks have been unsettled,” the authors note. Studies have produced conflicting results – showing no overall cancer risk and a modestly increased overall cancer risk – associated with these agents.

A recent study reported that ACE inhibitors, as compared with ARBs, increased risk for lung cancer by 14%. The risk for lung cancer increased by 22% among those using ACE inhibitors for 5 years, and the risk peaked at 31% for patients who took ACE inhibitors for 10 years or longer.

The lead author of that lung cancer study, Laurent Azoulay, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal, offered some thoughts on the seemingly conflicting data now being reported showing a reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer.

“In a nutshell, this study has important methodologic issues that can explain the observed findings,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Azoulay pointed out that, in the univariate model, the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was associated with a 26% increased risk of colorectal cancer. “It is only after propensity score adjustment that the effect estimate reversed in the protective direction,” he pointed out. “However, the variables included in the propensity score model were measured in the same time window as the exposure, which can lead to an overadjustment bias and generate spurious findings.”

Another issue is that the study period did not begin at the time of the exposure, but rather at a distant point after treatment initiation – in this case, colorectal cancer screening. “As such, the authors excluded patients who were previously diagnosed with colorectal cancer prior to that point, which likely included patients exposed to ACE inhibitors/ARBs,” he said. “This approach can lead to the inclusion of the ‘survivors’ for whom the risk of developing colorectal cancer is lower.

“But certainly,” Dr. Azoulay added, “this possible association should be investigated using methodologically sound approaches.”

Take-home message for physicians

Another expert emphasized the observational nature of both studies. Raymond Townsend, MD, director of the Hypertension Program and a professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said: “First and foremost, these are observational studies and cannot make inference about causality; they can only show associations.”

He pointed out that, sometimes, associations are truly present, whereas at other times, there is bias or confounding that cannot be controlled for statistically because it is “unknown.” That said, the size of this latest study is a plus, and there is a reasonable follow-up period.

“The take-home [message] for practitioners is that there may be a benefit in keeping older people on ACE inhibitors on the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer if your last colonoscopy was negative,” Dr. Townsend, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

But there are some questions that remain unanswered regarding characteristics of the cohort, Dr. Townsend noted. “Who were the people having the colonoscopy in the first place? Were they a group at higher risk? Why were some on an ACE inhibitors/ARBs and many others not?”

There are other conclusions that clinicians can glean from this. “Make a choice of treatment for a patient based on your best estimate of what will lower their blood pressure and prevent hypertension-mediated organ damage,” said Dr. Townsend, who is also an American Heart Association volunteer expert. “Keep in mind that patients hear about these studies and read unreviewed blogs on the web and so have questions.”

He emphasized that it always comes back to two things. “One is that every treatment decision is inherently a risk-benefit scenario,” he said. “And second is that most of our patients are adults, and if they choose to not be treated for their hypertension despite our best advice and reasoning with them, relinquish control and let them proceed as they wish, offering to renegotiate in the future when and if they reconsider.”

Study details

In the latest study, Dr. Leung and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study and used data from an electronic health care database of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. A total of 187,897 individuals aged 40 years and older had undergone colonoscopy between 2005 and 2013 with a negative result and were included in the analysis.

The study’s primary outcome was colorectal cancer that was diagnosed between 6 and 36 months after undergoing colonoscopy, and the median age at colonoscopy was 60.6 years. Within this population, 30,856 patients (16.4%) used ACE inhibitors/ARBs.

Between 6 months and 3 years after undergoing colonoscopy, 854 cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed, with an incidence rate of 15.2 per 10,000 person-years. The median time between colonoscopy and diagnosis was 1.2 years.

ACE inhibitor/ARB users had a median duration of 3.3 years of use within the 5-year period before their colonoscopy. Within this group, there were 169 (0.55%) cases of colorectal cancer. On univariate analysis, the crude hazard ratio (HR) of colorectal cancer and ACE inhibitor/ARB use was 1.26 (P = .008), but on propensity score regression adjustment, the adjusted HR became 0.78.

The propensity score absolute reduction in risk for users was 3.2 per 10,000 person-years versus nonusers, and stratification by subsite showed an HR of 0.77 for distal cancers and 0.83 for proximal cancers.

In a subgroup analysis, the benefits of ACE inhibitors and ARBs were seen in patients aged 55 years or older (adjusted HR, 0.79) and in those with a history of colonic polyps (adjusted HR, 0.71).

The authors also assessed if there was an association between these medications and other types of cancer. On univariate analysis, usage was associated with an increased risk of lung and prostate cancer but lower risk of breast cancer. But after propensity score regression adjustment, the associations were no longer there.

The study was funded by the Health and Medical Research Fund of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Dr. Leung has received honorarium for attending advisory board meetings of AbbVie, Takeda, and Abbott Laboratories; coauthor Esther W. Chan has received funding support from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Takeda, Janssen (a division of Johnson & Johnson); Research Grants Council of Hong Kong; Narcotics Division, Security Bureau; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, all for work unrelated to the current study. None of the other authors have disclosed relevant financial relationships. Dr. Azoulay has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Townsend is employed by Penn Medicine.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating hypertension with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) was associated with a reduced risk for colorectal cancer, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

However, another study reported just over a year ago suggested that ACE inhibitors, but not ARBs, are associated with an increased risk for lung cancer. An expert approached for comment emphasized that both studies are observational, and, as such, they only show an association, not causation.

In this latest study, published online July 6 in the journal Hypertension, the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs was associated with a 22% lower risk for colorectal cancer developing within 3 years after a negative baseline colonoscopy.