User login

LAAOS III: Surgical LAA closure cuts AFib stroke risk by one third

Left atrial appendage occlusion performed at the time of other heart surgery reduces the risk for stroke by about one-third in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), according to results of the Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study III (LAAOS III).

At 3.8 years’ follow-up, the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 4.8% of patients randomly assigned to left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) and 7.0% of those with no occlusion. This translated into a 33% relative risk reduction (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.85; P = .001).

In a landmark analysis, the effect was present early on but was more pronounced after the first 30 days, reducing the relative risk by 42% (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.80), the researchers report.

The reduction in ongoing stroke risk was on top of oral anticoagulation (OAC) and consistent across all subgroups, Richard Whitlock, MD, PhD, professor of surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., reported in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The procedure was safe and added, on average, just 6 minutes to cardiopulmonary bypass time, according to the results, simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Any patient who comes to the operating room who fits the profile of a LAAOS III patient – so has atrial fibrillation and an elevated stroke risk based on their CHA2DS2-VASc score – the appendage should come off,” he said in an interview.

Commenting during the formal discussion, panelist Michael J. Mack, MD, of Baylor Health Care System in Houston, said, “This is potentially a game-changing, practice-changing study” but asked if there are any patients who shouldn’t undergo LAAO, such as those with heart failure (HF).

Dr. Whitlock said about 10%-15% of patients coming for heart surgery have a history of AFib and “as surgeons, you do need to individualize therapy. If you have a very frail patient, have concerns about tissue quality, you really need to think about how you would occlude the left atrial appendage or if you would occlude.”

Reassuringly, he noted, the data show no increase in HF hospitalizations and a beneficial effect on stroke among patients with HF and those with low ejection fractions, below 50%.

Observational data on surgical occlusion have been inconsistent, and current guidelines offer a weak recommendation in patients with AFib who have a contraindication to long-term anticoagulation. This is the first study to definitively prove that ischemic stroke is reduced by managing the left atrial appendage, he said in an interview.

“The previous percutaneous trials failed to demonstrate that; they demonstrated noninferiority but it was driven primarily by the avoidance of hemorrhagic events or strokes through taking patients off oral anticoagulation,” he said.

The results should translate into a class I guideline recommendation, he added. “This opens up a new paradigm of treatment for atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention in that it is really the first study that has looked at the additive effects of managing the left atrial appendage in addition to oral anticoagulation, and it’s protective on top of oral anticoagulation. That is a paradigm shift.”

In an accompanying editorial, Richard L. Page, MD, University of Vermont in Burlington, said the trial provides no insight on the possible benefit of surgical occlusion in patients unable to receive anticoagulation or with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score, but he agreed a class I recommendation is likely for the population studied.

“I hope and anticipate that the results of this paper will strengthen the guideline indications for surgical left atrial appendage occlusion and will increase the number of cardiac surgeons who routinely perform this add-on procedure,” he said. “While many already perform this procedure, cardiac surgeons should now feel more comfortable that surgical left atrial appendage occlusion is indicated and supported by high-quality randomized data.”

Unfortunately, LAAOS III does not answer the question of whether patients can come off anticoagulation, but it does show surgical occlusion provides added protection from strokes, which can be huge with atrial fibrillation, Dr. Whitlock said.

“I spoke with a patient today who is an active 66-year-old individual on a [direct oral anticoagulant], and his stroke risk has been further reduced by 30%-40%, so he was ecstatic to hear the results,” Dr. Whitlock said. “I think it’s peace of mind.”

Global, nonindustry effort

LAAOS III investigators at 105 centers in 27 countries enrolled 4,811 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (mean age, 71 years; 68% male) who had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2.

In all, 4,770 were randomly assigned to no LAAO or occlusion via the preferred technique of amputation with suture closure of the stump as well as stapler occlusion, or epicardial device closure with the AtriClip (AtriCure) or TigerPaw (Maquet Medical). The treating team, researchers, and patients were blinded to assignment.

Patients were followed every 6 months with a validated stroke questionnaire. The trial was stopped early by the data safety monitoring board after the second interim analysis.

The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.2, one-third of patients had permanent AFib, 9% had a history of stroke, and more than two-thirds underwent a valve procedure, which makes LAAOS III unique, as many previous trials excluded valvular AFib, Dr. Whitlock pointed out.

Operative outcomes in the LAAO and no-LAAO groups were as follows:

- Bypass time: mean, 119 minutes vs. 113 minutes.

- Cross-clamp time: mean, 86 minutes vs. 82 minutes.

- Chest tube output: median, 520 mL vs. 500 mL.

- Reoperation for bleeding: both, 4.0%.

- Prolonged hospitalization due to HF: 5 vs. 14 events.

- 30-day mortality: 3.7% vs 4.0%.

The primary safety outcome of HF hospitalization at 3.8 years occurred in 7.7% of patients with LAAO and 6.8% without occlusion (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.92-1.40), despite concerns that taking off the appendage could worsen HF risk by impairing renal clearance of salt and water.

“There’s observational data on either side of the fence, so it was an important endpoint that people were concerned about,” Dr. Whitlock told this news organization. “We had a data collection firm dedicated to admission for heart failure to really tease that out and, in the end, we saw no adverse effect.”

Although rates of ischemic stroke at 3.8 years were lower with LAAO than without (4.2% vs. 6.6%; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80), there was no difference in systemic embolism (0.3% for both) or death (22.6% vs. 22.5%).

In LAAOS III, fewer than 2% of the deaths were attributed to stroke, which is consistent with large stroke registries, Dr. Whitlock said. “Stroke is not what causes people with atrial fibrillation to die; it’s actually the progression on to heart failure.”

The positive effect on stroke was consistent across all subgroups, including sex, age, rheumatic heart disease, type of OAC at baseline, CHA2DS2-VASc score (≤4 vs. >4), type of surgery, history of heart failure or hypertension, and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/systemic embolism.

Panelist Anne B. Curtis, MD, State University of New York at Buffalo, expressed surprise that about half of patients at baseline were not receiving anticoagulation and questioned whether event rates varied among those who did and didn’t stay on OAC.

Dr. Whitlock noted that OAC is often underused in AFib and that analyses showed the effects were consistent whether patients were on or off anticoagulants.

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University. Dr. Whitlock reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Curtis reported consultant fees/honoraria from Abbott, Janssen, Medtronic, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi Aventis, and data safety monitoring board participation for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Left atrial appendage occlusion performed at the time of other heart surgery reduces the risk for stroke by about one-third in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), according to results of the Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study III (LAAOS III).

At 3.8 years’ follow-up, the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 4.8% of patients randomly assigned to left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) and 7.0% of those with no occlusion. This translated into a 33% relative risk reduction (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.85; P = .001).

In a landmark analysis, the effect was present early on but was more pronounced after the first 30 days, reducing the relative risk by 42% (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.80), the researchers report.

The reduction in ongoing stroke risk was on top of oral anticoagulation (OAC) and consistent across all subgroups, Richard Whitlock, MD, PhD, professor of surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., reported in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The procedure was safe and added, on average, just 6 minutes to cardiopulmonary bypass time, according to the results, simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Any patient who comes to the operating room who fits the profile of a LAAOS III patient – so has atrial fibrillation and an elevated stroke risk based on their CHA2DS2-VASc score – the appendage should come off,” he said in an interview.

Commenting during the formal discussion, panelist Michael J. Mack, MD, of Baylor Health Care System in Houston, said, “This is potentially a game-changing, practice-changing study” but asked if there are any patients who shouldn’t undergo LAAO, such as those with heart failure (HF).

Dr. Whitlock said about 10%-15% of patients coming for heart surgery have a history of AFib and “as surgeons, you do need to individualize therapy. If you have a very frail patient, have concerns about tissue quality, you really need to think about how you would occlude the left atrial appendage or if you would occlude.”

Reassuringly, he noted, the data show no increase in HF hospitalizations and a beneficial effect on stroke among patients with HF and those with low ejection fractions, below 50%.

Observational data on surgical occlusion have been inconsistent, and current guidelines offer a weak recommendation in patients with AFib who have a contraindication to long-term anticoagulation. This is the first study to definitively prove that ischemic stroke is reduced by managing the left atrial appendage, he said in an interview.

“The previous percutaneous trials failed to demonstrate that; they demonstrated noninferiority but it was driven primarily by the avoidance of hemorrhagic events or strokes through taking patients off oral anticoagulation,” he said.

The results should translate into a class I guideline recommendation, he added. “This opens up a new paradigm of treatment for atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention in that it is really the first study that has looked at the additive effects of managing the left atrial appendage in addition to oral anticoagulation, and it’s protective on top of oral anticoagulation. That is a paradigm shift.”

In an accompanying editorial, Richard L. Page, MD, University of Vermont in Burlington, said the trial provides no insight on the possible benefit of surgical occlusion in patients unable to receive anticoagulation or with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score, but he agreed a class I recommendation is likely for the population studied.

“I hope and anticipate that the results of this paper will strengthen the guideline indications for surgical left atrial appendage occlusion and will increase the number of cardiac surgeons who routinely perform this add-on procedure,” he said. “While many already perform this procedure, cardiac surgeons should now feel more comfortable that surgical left atrial appendage occlusion is indicated and supported by high-quality randomized data.”

Unfortunately, LAAOS III does not answer the question of whether patients can come off anticoagulation, but it does show surgical occlusion provides added protection from strokes, which can be huge with atrial fibrillation, Dr. Whitlock said.

“I spoke with a patient today who is an active 66-year-old individual on a [direct oral anticoagulant], and his stroke risk has been further reduced by 30%-40%, so he was ecstatic to hear the results,” Dr. Whitlock said. “I think it’s peace of mind.”

Global, nonindustry effort

LAAOS III investigators at 105 centers in 27 countries enrolled 4,811 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (mean age, 71 years; 68% male) who had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2.

In all, 4,770 were randomly assigned to no LAAO or occlusion via the preferred technique of amputation with suture closure of the stump as well as stapler occlusion, or epicardial device closure with the AtriClip (AtriCure) or TigerPaw (Maquet Medical). The treating team, researchers, and patients were blinded to assignment.

Patients were followed every 6 months with a validated stroke questionnaire. The trial was stopped early by the data safety monitoring board after the second interim analysis.

The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.2, one-third of patients had permanent AFib, 9% had a history of stroke, and more than two-thirds underwent a valve procedure, which makes LAAOS III unique, as many previous trials excluded valvular AFib, Dr. Whitlock pointed out.

Operative outcomes in the LAAO and no-LAAO groups were as follows:

- Bypass time: mean, 119 minutes vs. 113 minutes.

- Cross-clamp time: mean, 86 minutes vs. 82 minutes.

- Chest tube output: median, 520 mL vs. 500 mL.

- Reoperation for bleeding: both, 4.0%.

- Prolonged hospitalization due to HF: 5 vs. 14 events.

- 30-day mortality: 3.7% vs 4.0%.

The primary safety outcome of HF hospitalization at 3.8 years occurred in 7.7% of patients with LAAO and 6.8% without occlusion (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.92-1.40), despite concerns that taking off the appendage could worsen HF risk by impairing renal clearance of salt and water.

“There’s observational data on either side of the fence, so it was an important endpoint that people were concerned about,” Dr. Whitlock told this news organization. “We had a data collection firm dedicated to admission for heart failure to really tease that out and, in the end, we saw no adverse effect.”

Although rates of ischemic stroke at 3.8 years were lower with LAAO than without (4.2% vs. 6.6%; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80), there was no difference in systemic embolism (0.3% for both) or death (22.6% vs. 22.5%).

In LAAOS III, fewer than 2% of the deaths were attributed to stroke, which is consistent with large stroke registries, Dr. Whitlock said. “Stroke is not what causes people with atrial fibrillation to die; it’s actually the progression on to heart failure.”

The positive effect on stroke was consistent across all subgroups, including sex, age, rheumatic heart disease, type of OAC at baseline, CHA2DS2-VASc score (≤4 vs. >4), type of surgery, history of heart failure or hypertension, and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/systemic embolism.

Panelist Anne B. Curtis, MD, State University of New York at Buffalo, expressed surprise that about half of patients at baseline were not receiving anticoagulation and questioned whether event rates varied among those who did and didn’t stay on OAC.

Dr. Whitlock noted that OAC is often underused in AFib and that analyses showed the effects were consistent whether patients were on or off anticoagulants.

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University. Dr. Whitlock reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Curtis reported consultant fees/honoraria from Abbott, Janssen, Medtronic, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi Aventis, and data safety monitoring board participation for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Left atrial appendage occlusion performed at the time of other heart surgery reduces the risk for stroke by about one-third in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), according to results of the Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study III (LAAOS III).

At 3.8 years’ follow-up, the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 4.8% of patients randomly assigned to left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) and 7.0% of those with no occlusion. This translated into a 33% relative risk reduction (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-0.85; P = .001).

In a landmark analysis, the effect was present early on but was more pronounced after the first 30 days, reducing the relative risk by 42% (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42-0.80), the researchers report.

The reduction in ongoing stroke risk was on top of oral anticoagulation (OAC) and consistent across all subgroups, Richard Whitlock, MD, PhD, professor of surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., reported in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The procedure was safe and added, on average, just 6 minutes to cardiopulmonary bypass time, according to the results, simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Any patient who comes to the operating room who fits the profile of a LAAOS III patient – so has atrial fibrillation and an elevated stroke risk based on their CHA2DS2-VASc score – the appendage should come off,” he said in an interview.

Commenting during the formal discussion, panelist Michael J. Mack, MD, of Baylor Health Care System in Houston, said, “This is potentially a game-changing, practice-changing study” but asked if there are any patients who shouldn’t undergo LAAO, such as those with heart failure (HF).

Dr. Whitlock said about 10%-15% of patients coming for heart surgery have a history of AFib and “as surgeons, you do need to individualize therapy. If you have a very frail patient, have concerns about tissue quality, you really need to think about how you would occlude the left atrial appendage or if you would occlude.”

Reassuringly, he noted, the data show no increase in HF hospitalizations and a beneficial effect on stroke among patients with HF and those with low ejection fractions, below 50%.

Observational data on surgical occlusion have been inconsistent, and current guidelines offer a weak recommendation in patients with AFib who have a contraindication to long-term anticoagulation. This is the first study to definitively prove that ischemic stroke is reduced by managing the left atrial appendage, he said in an interview.

“The previous percutaneous trials failed to demonstrate that; they demonstrated noninferiority but it was driven primarily by the avoidance of hemorrhagic events or strokes through taking patients off oral anticoagulation,” he said.

The results should translate into a class I guideline recommendation, he added. “This opens up a new paradigm of treatment for atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention in that it is really the first study that has looked at the additive effects of managing the left atrial appendage in addition to oral anticoagulation, and it’s protective on top of oral anticoagulation. That is a paradigm shift.”

In an accompanying editorial, Richard L. Page, MD, University of Vermont in Burlington, said the trial provides no insight on the possible benefit of surgical occlusion in patients unable to receive anticoagulation or with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score, but he agreed a class I recommendation is likely for the population studied.

“I hope and anticipate that the results of this paper will strengthen the guideline indications for surgical left atrial appendage occlusion and will increase the number of cardiac surgeons who routinely perform this add-on procedure,” he said. “While many already perform this procedure, cardiac surgeons should now feel more comfortable that surgical left atrial appendage occlusion is indicated and supported by high-quality randomized data.”

Unfortunately, LAAOS III does not answer the question of whether patients can come off anticoagulation, but it does show surgical occlusion provides added protection from strokes, which can be huge with atrial fibrillation, Dr. Whitlock said.

“I spoke with a patient today who is an active 66-year-old individual on a [direct oral anticoagulant], and his stroke risk has been further reduced by 30%-40%, so he was ecstatic to hear the results,” Dr. Whitlock said. “I think it’s peace of mind.”

Global, nonindustry effort

LAAOS III investigators at 105 centers in 27 countries enrolled 4,811 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (mean age, 71 years; 68% male) who had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2.

In all, 4,770 were randomly assigned to no LAAO or occlusion via the preferred technique of amputation with suture closure of the stump as well as stapler occlusion, or epicardial device closure with the AtriClip (AtriCure) or TigerPaw (Maquet Medical). The treating team, researchers, and patients were blinded to assignment.

Patients were followed every 6 months with a validated stroke questionnaire. The trial was stopped early by the data safety monitoring board after the second interim analysis.

The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.2, one-third of patients had permanent AFib, 9% had a history of stroke, and more than two-thirds underwent a valve procedure, which makes LAAOS III unique, as many previous trials excluded valvular AFib, Dr. Whitlock pointed out.

Operative outcomes in the LAAO and no-LAAO groups were as follows:

- Bypass time: mean, 119 minutes vs. 113 minutes.

- Cross-clamp time: mean, 86 minutes vs. 82 minutes.

- Chest tube output: median, 520 mL vs. 500 mL.

- Reoperation for bleeding: both, 4.0%.

- Prolonged hospitalization due to HF: 5 vs. 14 events.

- 30-day mortality: 3.7% vs 4.0%.

The primary safety outcome of HF hospitalization at 3.8 years occurred in 7.7% of patients with LAAO and 6.8% without occlusion (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.92-1.40), despite concerns that taking off the appendage could worsen HF risk by impairing renal clearance of salt and water.

“There’s observational data on either side of the fence, so it was an important endpoint that people were concerned about,” Dr. Whitlock told this news organization. “We had a data collection firm dedicated to admission for heart failure to really tease that out and, in the end, we saw no adverse effect.”

Although rates of ischemic stroke at 3.8 years were lower with LAAO than without (4.2% vs. 6.6%; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80), there was no difference in systemic embolism (0.3% for both) or death (22.6% vs. 22.5%).

In LAAOS III, fewer than 2% of the deaths were attributed to stroke, which is consistent with large stroke registries, Dr. Whitlock said. “Stroke is not what causes people with atrial fibrillation to die; it’s actually the progression on to heart failure.”

The positive effect on stroke was consistent across all subgroups, including sex, age, rheumatic heart disease, type of OAC at baseline, CHA2DS2-VASc score (≤4 vs. >4), type of surgery, history of heart failure or hypertension, and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/systemic embolism.

Panelist Anne B. Curtis, MD, State University of New York at Buffalo, expressed surprise that about half of patients at baseline were not receiving anticoagulation and questioned whether event rates varied among those who did and didn’t stay on OAC.

Dr. Whitlock noted that OAC is often underused in AFib and that analyses showed the effects were consistent whether patients were on or off anticoagulants.

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University. Dr. Whitlock reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Curtis reported consultant fees/honoraria from Abbott, Janssen, Medtronic, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi Aventis, and data safety monitoring board participation for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACC 2021

Fresh look at ISCHEMIA bolsters conservative message in stable CAD

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

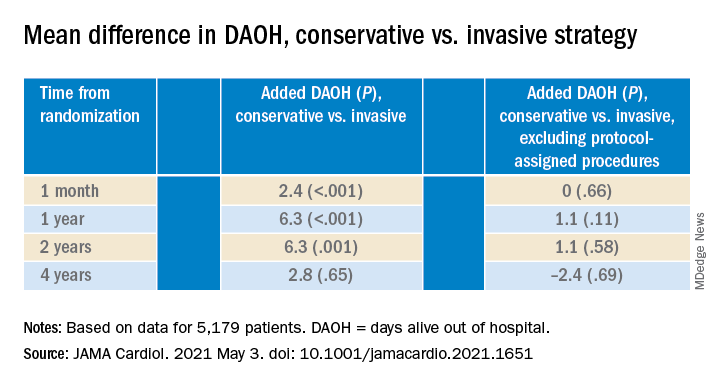

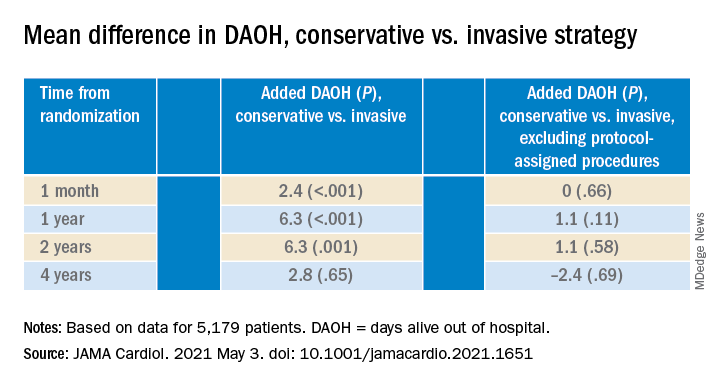

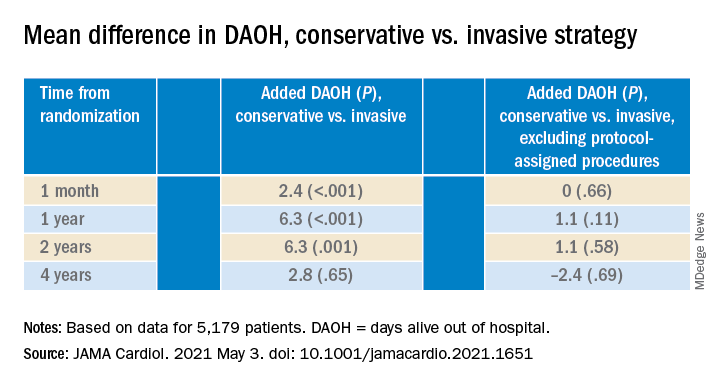

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infective endocarditis with stroke after TAVR has ‘dismal’ prognosis

Patients who suffer a stroke during hospitalization for infective endocarditis (IE) after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a dismal prognosis, with more than half dying during the index hospitalization and two-thirds within the first year, a new study shows.

The study – the first to evaluate stroke as an IE-related complication following TAVR in a large multicenter cohort – is published in the May 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors, led by David del Val, MD, Quebec Heart & Lung Institute, Quebec City, explain that IE after TAVR is a rare but serious complication associated with a high mortality rate. Neurologic events, especially stroke, remain one of the most common and potentially disabling IE-related complications, but until now, no study has attempted to evaluate the predictors of stroke and outcomes in patients with IE following TAVR.

For the current study, the authors analyzed data from the Infectious Endocarditis after TAVR International Registry, including 569 patients who developed definite IE following TAVR from 59 centers in 11 countries.

Patients who experienced a stroke during IE admission were compared with patients who did not have a stroke.

Results showed that 57 patients (10%) had a stroke during IE hospitalization, with no differences in the causative microorganism between groups. Stroke patients had higher rates of acute renal failure, systemic embolization, and persistent bacteremia.

Factors associated with a higher risk for stroke during the index IE hospitalization included stroke before IE, moderate or higher residual aortic regurgitation after TAVR, balloon-expandable valves, IE within 30 days after TAVR, and vegetation size greater than 8 mm.

The stroke rate was 3.1% in patients with none of these risk factors; 6.1% with one risk factor; 13.1% with two risk factors; 28.9% with three risk factors, and 60% with four risk factors.

“The presence of such factors (particularly in combination) may be considered for determining an earlier and more aggressive (medical or surgical) treatment in these patients,” the researchers say.

IE patients with stroke had higher rates of in-hospital mortality (54.4% vs. 28.7%) and overall mortality at 1 year (66.3% vs. 45.6%).

Surgery rates were low (25%) even in the presence of stroke and failed to improve outcomes in this population.

Noting that consensus guidelines for managing patients with IE recommend surgery along with antibiotic treatment for patients developing systemic embolism, particularly stroke, the researchers say their findings suggest that such surgery recommendations may not be extrapolated to TAVR-IE patients, and specific guidelines are warranted for this particular population.

Furthermore, the possibility of early surgery in those patients with factors increasing the risk for stroke should be evaluated in future studies.

The authors note that TAVR has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis and is currently moving toward less complex and younger patients with lower surgical risk. Despite the relatively low incidence of IE after TAVR, the number of procedures is expected to grow exponentially, increasing the number of patients at risk of developing this life-threatening complication. Therefore, detailed knowledge of this disease and its complications is essential to improve outcomes.

They point out that the 10% rate of stroke found in this study is substantially lower, compared with the largest surgical prosthetic-valve infective endocarditis registries, but they suggest that the unique clinical profile of TAVR patients may lead to an underdiagnosis of stroke, with a high proportion of elderly patients who more frequently present with nonspecific symptoms.

They conclude that “IE post-TAVR is associated with a poor prognosis with high in-hospital and late mortality rates. Our study reveals that patients with IE after TAVR complicated by stroke showed an even worse prognosis.”

“The progressive implementation of advanced imaging modalities for early IE diagnosis, especially nuclear imaging, may translate into a better prognosis in coming years. Close attention should be paid to early recognition of stroke-associated factors to improve clinical outcomes,” they add.

In an accompanying editorial, Vuyisile Nkomo, MD, Daniel DeSimone, MD, and William Miranda, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., say the current study “highlights the devastating consequences of IE after TAVR and the even worse consequences when IE was associated with stroke.”

This points to the critical importance of efforts to prevent IE with appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis and addressing potential sources of infection (for example, dental screening) before invasive cardiac procedures.

“Patient education is critical in regard to recognizing early signs and symptoms of IE. In particular, patients must be informed to obtain blood cultures with any episode of fever, as identification of bacteremia is critical in the diagnosis of IE,” the editorialists comment.

Endocarditis should also be suspected in afebrile patients with increasing transcatheter heart valve gradients or new or worsening regurgitation, they state.

Multimodality imaging is important for the early diagnosis of IE to facilitate prompt antibiotic treatment and potentially decrease the risk for IE complications, especially systemic embolization, they add.

“Despite the unequivocal advances in the safety and periprocedural complications of TAVR, IE with and without stroke in this TAVR population remains a dreadful complication,” they conclude.

Dr. Del Val was supported by a research grant from the Fundación Alfonso Martin Escudero. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who suffer a stroke during hospitalization for infective endocarditis (IE) after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a dismal prognosis, with more than half dying during the index hospitalization and two-thirds within the first year, a new study shows.

The study – the first to evaluate stroke as an IE-related complication following TAVR in a large multicenter cohort – is published in the May 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors, led by David del Val, MD, Quebec Heart & Lung Institute, Quebec City, explain that IE after TAVR is a rare but serious complication associated with a high mortality rate. Neurologic events, especially stroke, remain one of the most common and potentially disabling IE-related complications, but until now, no study has attempted to evaluate the predictors of stroke and outcomes in patients with IE following TAVR.

For the current study, the authors analyzed data from the Infectious Endocarditis after TAVR International Registry, including 569 patients who developed definite IE following TAVR from 59 centers in 11 countries.

Patients who experienced a stroke during IE admission were compared with patients who did not have a stroke.

Results showed that 57 patients (10%) had a stroke during IE hospitalization, with no differences in the causative microorganism between groups. Stroke patients had higher rates of acute renal failure, systemic embolization, and persistent bacteremia.

Factors associated with a higher risk for stroke during the index IE hospitalization included stroke before IE, moderate or higher residual aortic regurgitation after TAVR, balloon-expandable valves, IE within 30 days after TAVR, and vegetation size greater than 8 mm.

The stroke rate was 3.1% in patients with none of these risk factors; 6.1% with one risk factor; 13.1% with two risk factors; 28.9% with three risk factors, and 60% with four risk factors.

“The presence of such factors (particularly in combination) may be considered for determining an earlier and more aggressive (medical or surgical) treatment in these patients,” the researchers say.

IE patients with stroke had higher rates of in-hospital mortality (54.4% vs. 28.7%) and overall mortality at 1 year (66.3% vs. 45.6%).

Surgery rates were low (25%) even in the presence of stroke and failed to improve outcomes in this population.

Noting that consensus guidelines for managing patients with IE recommend surgery along with antibiotic treatment for patients developing systemic embolism, particularly stroke, the researchers say their findings suggest that such surgery recommendations may not be extrapolated to TAVR-IE patients, and specific guidelines are warranted for this particular population.

Furthermore, the possibility of early surgery in those patients with factors increasing the risk for stroke should be evaluated in future studies.

The authors note that TAVR has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis and is currently moving toward less complex and younger patients with lower surgical risk. Despite the relatively low incidence of IE after TAVR, the number of procedures is expected to grow exponentially, increasing the number of patients at risk of developing this life-threatening complication. Therefore, detailed knowledge of this disease and its complications is essential to improve outcomes.

They point out that the 10% rate of stroke found in this study is substantially lower, compared with the largest surgical prosthetic-valve infective endocarditis registries, but they suggest that the unique clinical profile of TAVR patients may lead to an underdiagnosis of stroke, with a high proportion of elderly patients who more frequently present with nonspecific symptoms.

They conclude that “IE post-TAVR is associated with a poor prognosis with high in-hospital and late mortality rates. Our study reveals that patients with IE after TAVR complicated by stroke showed an even worse prognosis.”

“The progressive implementation of advanced imaging modalities for early IE diagnosis, especially nuclear imaging, may translate into a better prognosis in coming years. Close attention should be paid to early recognition of stroke-associated factors to improve clinical outcomes,” they add.

In an accompanying editorial, Vuyisile Nkomo, MD, Daniel DeSimone, MD, and William Miranda, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., say the current study “highlights the devastating consequences of IE after TAVR and the even worse consequences when IE was associated with stroke.”

This points to the critical importance of efforts to prevent IE with appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis and addressing potential sources of infection (for example, dental screening) before invasive cardiac procedures.

“Patient education is critical in regard to recognizing early signs and symptoms of IE. In particular, patients must be informed to obtain blood cultures with any episode of fever, as identification of bacteremia is critical in the diagnosis of IE,” the editorialists comment.

Endocarditis should also be suspected in afebrile patients with increasing transcatheter heart valve gradients or new or worsening regurgitation, they state.

Multimodality imaging is important for the early diagnosis of IE to facilitate prompt antibiotic treatment and potentially decrease the risk for IE complications, especially systemic embolization, they add.

“Despite the unequivocal advances in the safety and periprocedural complications of TAVR, IE with and without stroke in this TAVR population remains a dreadful complication,” they conclude.

Dr. Del Val was supported by a research grant from the Fundación Alfonso Martin Escudero. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who suffer a stroke during hospitalization for infective endocarditis (IE) after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a dismal prognosis, with more than half dying during the index hospitalization and two-thirds within the first year, a new study shows.

The study – the first to evaluate stroke as an IE-related complication following TAVR in a large multicenter cohort – is published in the May 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors, led by David del Val, MD, Quebec Heart & Lung Institute, Quebec City, explain that IE after TAVR is a rare but serious complication associated with a high mortality rate. Neurologic events, especially stroke, remain one of the most common and potentially disabling IE-related complications, but until now, no study has attempted to evaluate the predictors of stroke and outcomes in patients with IE following TAVR.

For the current study, the authors analyzed data from the Infectious Endocarditis after TAVR International Registry, including 569 patients who developed definite IE following TAVR from 59 centers in 11 countries.

Patients who experienced a stroke during IE admission were compared with patients who did not have a stroke.

Results showed that 57 patients (10%) had a stroke during IE hospitalization, with no differences in the causative microorganism between groups. Stroke patients had higher rates of acute renal failure, systemic embolization, and persistent bacteremia.

Factors associated with a higher risk for stroke during the index IE hospitalization included stroke before IE, moderate or higher residual aortic regurgitation after TAVR, balloon-expandable valves, IE within 30 days after TAVR, and vegetation size greater than 8 mm.

The stroke rate was 3.1% in patients with none of these risk factors; 6.1% with one risk factor; 13.1% with two risk factors; 28.9% with three risk factors, and 60% with four risk factors.

“The presence of such factors (particularly in combination) may be considered for determining an earlier and more aggressive (medical or surgical) treatment in these patients,” the researchers say.

IE patients with stroke had higher rates of in-hospital mortality (54.4% vs. 28.7%) and overall mortality at 1 year (66.3% vs. 45.6%).

Surgery rates were low (25%) even in the presence of stroke and failed to improve outcomes in this population.

Noting that consensus guidelines for managing patients with IE recommend surgery along with antibiotic treatment for patients developing systemic embolism, particularly stroke, the researchers say their findings suggest that such surgery recommendations may not be extrapolated to TAVR-IE patients, and specific guidelines are warranted for this particular population.

Furthermore, the possibility of early surgery in those patients with factors increasing the risk for stroke should be evaluated in future studies.

The authors note that TAVR has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis and is currently moving toward less complex and younger patients with lower surgical risk. Despite the relatively low incidence of IE after TAVR, the number of procedures is expected to grow exponentially, increasing the number of patients at risk of developing this life-threatening complication. Therefore, detailed knowledge of this disease and its complications is essential to improve outcomes.

They point out that the 10% rate of stroke found in this study is substantially lower, compared with the largest surgical prosthetic-valve infective endocarditis registries, but they suggest that the unique clinical profile of TAVR patients may lead to an underdiagnosis of stroke, with a high proportion of elderly patients who more frequently present with nonspecific symptoms.

They conclude that “IE post-TAVR is associated with a poor prognosis with high in-hospital and late mortality rates. Our study reveals that patients with IE after TAVR complicated by stroke showed an even worse prognosis.”

“The progressive implementation of advanced imaging modalities for early IE diagnosis, especially nuclear imaging, may translate into a better prognosis in coming years. Close attention should be paid to early recognition of stroke-associated factors to improve clinical outcomes,” they add.

In an accompanying editorial, Vuyisile Nkomo, MD, Daniel DeSimone, MD, and William Miranda, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., say the current study “highlights the devastating consequences of IE after TAVR and the even worse consequences when IE was associated with stroke.”

This points to the critical importance of efforts to prevent IE with appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis and addressing potential sources of infection (for example, dental screening) before invasive cardiac procedures.

“Patient education is critical in regard to recognizing early signs and symptoms of IE. In particular, patients must be informed to obtain blood cultures with any episode of fever, as identification of bacteremia is critical in the diagnosis of IE,” the editorialists comment.

Endocarditis should also be suspected in afebrile patients with increasing transcatheter heart valve gradients or new or worsening regurgitation, they state.

Multimodality imaging is important for the early diagnosis of IE to facilitate prompt antibiotic treatment and potentially decrease the risk for IE complications, especially systemic embolization, they add.

“Despite the unequivocal advances in the safety and periprocedural complications of TAVR, IE with and without stroke in this TAVR population remains a dreadful complication,” they conclude.

Dr. Del Val was supported by a research grant from the Fundación Alfonso Martin Escudero. The editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

OCS heart system earns hard-won backing of FDA panel

After more than 10 hours of intense debate, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel gave its support to a premarket approval application (PMA) for the TransMedics Organ Care System (OCS) Heart system.

The OCS Heart is a portable extracorporeal perfusion and monitoring system designed to keep a donor heart in a normothermic, beating state. The “heart in a box” technology allows donor hearts to be transported across longer distances than is possible with standard cold storage, which can safely preserve donor hearts for about 4 hours.

The Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee voted 12 to 5, with 1 abstention, that the benefits of the OCS Heart System outweigh its risks.

The panel voted in favor of the OCS Heart being effective (10 yes, 6 no, and 2 abstaining) and safe (9 yes, 7 no, 2 abstaining) but not without mixed feelings.

James Blankenship, MD, a cardiologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, voted yes to all three questions but said: “If it had been compared to standard of care, I would have voted no to all three. But if it’s compared to getting an [left ventricular assist device] LVAD or not getting a heart at all, I would say the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Marc R. Katz, MD, chief of cardiothoracic surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, also gave universal support, noting that the rate of heart transplantations has been flat for years. “This is a big step forward toward being able to expand that number. Now all that said, it obviously was a less-than-perfect study and I do think there needs to be some constraints put on the utilization.”

The panel reviewed data from the single-arm OCS Heart EXPAND trial and associated EXPAND Continued Access Protocol (CAP), as well the sponsor’s first OCS Heart trial, PROCEED II.

EXPAND met its effectiveness endpoint, with 88% of donor hearts successfully transplanted, an 8% incidence of severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD) 24 hours after transplantation, and 94.6% survival at 30 days.

Data from 41 patients with 30-day follow-up in the ongoing EXPAND CAP show 91% of donor hearts were utilized, a 2.4% incidence of severe PGD, and 100% 30-day survival.

The sponsor and the FDA clashed over changes made to the trial after the PMA was submitted, the appropriateness of the effectiveness outcome, and claims by the FDA that there was substantial overlap in demographic characteristics between the extended criteria donor hearts in the EXPAND trials and the standard criteria donor hearts in PROCEED II.

TransMedics previously submitted a PMA based on PROCEED II but it noted in submitted documents that it was withdrawn because of “fundamental disagreements with FDA” on the interpretation of a post hoc analysis with United Network for Organ Sharing registry data that identified increased all-cause mortality risk but comparable cardiac-related mortality in patients with OCS hearts.

During the marathon hearing, FDA officials presented several post hoc analyses, including one stratified by donor inclusion criteria, in which 30-day survival estimates were worse in recipients of single-criterion organs than for those receiving donor organs with multiple inclusion criteria (85% vs. 91.4%). In a second analysis, 2-year point estimates of survival also trended lower with donor organs having only one extended criterion.

Reported EXPAND CAP 6- and 12-month survival estimates were 100% and 93%, respectively, which was higher than EXPAND (93% and 84%), but there was substantial censoring (>50%) at 6 months and beyond, FDA officials said.

When EXPAND and CAP data were pooled, modeled survival curves shifted upward but there was a substantial site effect, with a single site contributing 46% of data, which may affect generalizability of the results, they noted.

“I voted yes for safety, no for efficacy, and no for approval and I’d just like to say I found this to be the most difficult vote in my experience on this panel,” John Hirshfeld, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “I was very concerned that the PROCEED data suggests a possible harm, and in the absence of an interpretable comparator for the EXPAND trial, it’s really not possible to decide if there’s efficacy.”

Keith B. Allen, MD, director of surgical research at Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City (Mo.), said, “I voted no on safety; I’m not going to give the company a pass. I think their animal data was sorely lacking and a lot of issues over the last 10 years could have been addressed with some key animal studies.

“For efficacy and risk/benefit, I voted yes for both,” he said. “Had this been standard of care and only PROCEED II, I would have voted no, but I do think there are a lot of hearts that go in the bucket and this is a challenging population.”

More than a dozen physicians and patients spoke at the open public hearing about the potential for the device to expand donor heart utilization, including a recipient whose own father died while waiting on the transplant list. Only about 3 out of every 10 donated hearts are used for transplant. To ensure fair access, particularly for patients in rural areas, federal changes in 2020 mandate that organs be allocated to the sickest patients first.

Data showed that the OCS Heart System was associated with shorter waiting list times, compared with U.S. averages but longer preservation times than cold static preservation.

In all, 13% of accepted donor organs were subsequently turned down after OCS heart preservation. Lactate levels were cited as the principal reason for turn-down but, FDA officials said, the validity of using lactate as a marker for transplantability is unclear.

Pathologic analysis of OCS Heart turned-down donor hearts with stable antemortem hemodynamics, normal or near-normal anatomy and normal ventricular function by echocardiography, and autopsy findings of acute diffuse or multifocal myocardial damage “suggest that in an important proportion of cases the OCS Heart system did not provide effective organ preservation or its use caused severe myocardial damage to what might have been an acceptable graft for transplant,” said Andrew Farb, MD, chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Cardiovascular Devices.

Proposed indication

In the present PMA, the OCS Heart System is indicated for donor hearts with one or more of the following characteristics: an expected cross-clamp or ischemic time of at least 4 hours because of donor or recipient characteristics; or an expected total cross-clamp time of at least 2 hours plus one of the following risk factors: donor age 55 or older, history of cardiac arrest and downtime of at least 20 minutes, history of alcoholism, history of diabetes, donor ejection fraction of 40%-50%,history of left ventricular hypertrophy, and donor angiogram with luminal irregularities but no significant coronary artery disease

Several members voiced concern about “indication creep” should the device be approved by the FDA, and highlighted the 2-hour cross-clamp time plus wide-ranging risk factors.

“I’m a surgeon and I voted no on all three counts,” said Murray H. Kwon, MD, Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center. “As far as risk/benefit, if it was just limited to one group – the 4-hour plus – I would say yes, but if you’re going to tell me that there’s a risk/benefit for the 2-hour with the alcoholic, I don’t know how that was proved in anything.”

Dr. Kwon was also troubled by lack of proper controls and by the one quarter of patients who ended up on mechanical circulatory support in the first 30 days after transplant. “I find that highly aberrant.”

Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said the unmet need for patients with refractory, end-stage heart failure is challenging and quite emotional, but also voted no across the board, citing concerns about a lack of comparator in the EXPAND trials and overall out-of-body ischemic time.

“As it relates to risk/benefit, I thought long and hard about voting yes despite all the unknowns because of this emotion, but ultimately I voted no because of the secondary 2-hours plus alcoholism, diabetes, or minor coronary disease, in which the ischemic burden and ongoing lactate production concern me,” he said.

Although the panel decision is nonbinding, there was strong support from the committee members for a randomized, postapproval trial and more complete animal studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After more than 10 hours of intense debate, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel gave its support to a premarket approval application (PMA) for the TransMedics Organ Care System (OCS) Heart system.

The OCS Heart is a portable extracorporeal perfusion and monitoring system designed to keep a donor heart in a normothermic, beating state. The “heart in a box” technology allows donor hearts to be transported across longer distances than is possible with standard cold storage, which can safely preserve donor hearts for about 4 hours.

The Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee voted 12 to 5, with 1 abstention, that the benefits of the OCS Heart System outweigh its risks.

The panel voted in favor of the OCS Heart being effective (10 yes, 6 no, and 2 abstaining) and safe (9 yes, 7 no, 2 abstaining) but not without mixed feelings.

James Blankenship, MD, a cardiologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, voted yes to all three questions but said: “If it had been compared to standard of care, I would have voted no to all three. But if it’s compared to getting an [left ventricular assist device] LVAD or not getting a heart at all, I would say the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Marc R. Katz, MD, chief of cardiothoracic surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, also gave universal support, noting that the rate of heart transplantations has been flat for years. “This is a big step forward toward being able to expand that number. Now all that said, it obviously was a less-than-perfect study and I do think there needs to be some constraints put on the utilization.”

The panel reviewed data from the single-arm OCS Heart EXPAND trial and associated EXPAND Continued Access Protocol (CAP), as well the sponsor’s first OCS Heart trial, PROCEED II.

EXPAND met its effectiveness endpoint, with 88% of donor hearts successfully transplanted, an 8% incidence of severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD) 24 hours after transplantation, and 94.6% survival at 30 days.

Data from 41 patients with 30-day follow-up in the ongoing EXPAND CAP show 91% of donor hearts were utilized, a 2.4% incidence of severe PGD, and 100% 30-day survival.

The sponsor and the FDA clashed over changes made to the trial after the PMA was submitted, the appropriateness of the effectiveness outcome, and claims by the FDA that there was substantial overlap in demographic characteristics between the extended criteria donor hearts in the EXPAND trials and the standard criteria donor hearts in PROCEED II.

TransMedics previously submitted a PMA based on PROCEED II but it noted in submitted documents that it was withdrawn because of “fundamental disagreements with FDA” on the interpretation of a post hoc analysis with United Network for Organ Sharing registry data that identified increased all-cause mortality risk but comparable cardiac-related mortality in patients with OCS hearts.

During the marathon hearing, FDA officials presented several post hoc analyses, including one stratified by donor inclusion criteria, in which 30-day survival estimates were worse in recipients of single-criterion organs than for those receiving donor organs with multiple inclusion criteria (85% vs. 91.4%). In a second analysis, 2-year point estimates of survival also trended lower with donor organs having only one extended criterion.

Reported EXPAND CAP 6- and 12-month survival estimates were 100% and 93%, respectively, which was higher than EXPAND (93% and 84%), but there was substantial censoring (>50%) at 6 months and beyond, FDA officials said.

When EXPAND and CAP data were pooled, modeled survival curves shifted upward but there was a substantial site effect, with a single site contributing 46% of data, which may affect generalizability of the results, they noted.

“I voted yes for safety, no for efficacy, and no for approval and I’d just like to say I found this to be the most difficult vote in my experience on this panel,” John Hirshfeld, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “I was very concerned that the PROCEED data suggests a possible harm, and in the absence of an interpretable comparator for the EXPAND trial, it’s really not possible to decide if there’s efficacy.”

Keith B. Allen, MD, director of surgical research at Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City (Mo.), said, “I voted no on safety; I’m not going to give the company a pass. I think their animal data was sorely lacking and a lot of issues over the last 10 years could have been addressed with some key animal studies.

“For efficacy and risk/benefit, I voted yes for both,” he said. “Had this been standard of care and only PROCEED II, I would have voted no, but I do think there are a lot of hearts that go in the bucket and this is a challenging population.”

More than a dozen physicians and patients spoke at the open public hearing about the potential for the device to expand donor heart utilization, including a recipient whose own father died while waiting on the transplant list. Only about 3 out of every 10 donated hearts are used for transplant. To ensure fair access, particularly for patients in rural areas, federal changes in 2020 mandate that organs be allocated to the sickest patients first.

Data showed that the OCS Heart System was associated with shorter waiting list times, compared with U.S. averages but longer preservation times than cold static preservation.

In all, 13% of accepted donor organs were subsequently turned down after OCS heart preservation. Lactate levels were cited as the principal reason for turn-down but, FDA officials said, the validity of using lactate as a marker for transplantability is unclear.

Pathologic analysis of OCS Heart turned-down donor hearts with stable antemortem hemodynamics, normal or near-normal anatomy and normal ventricular function by echocardiography, and autopsy findings of acute diffuse or multifocal myocardial damage “suggest that in an important proportion of cases the OCS Heart system did not provide effective organ preservation or its use caused severe myocardial damage to what might have been an acceptable graft for transplant,” said Andrew Farb, MD, chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Cardiovascular Devices.

Proposed indication