User login

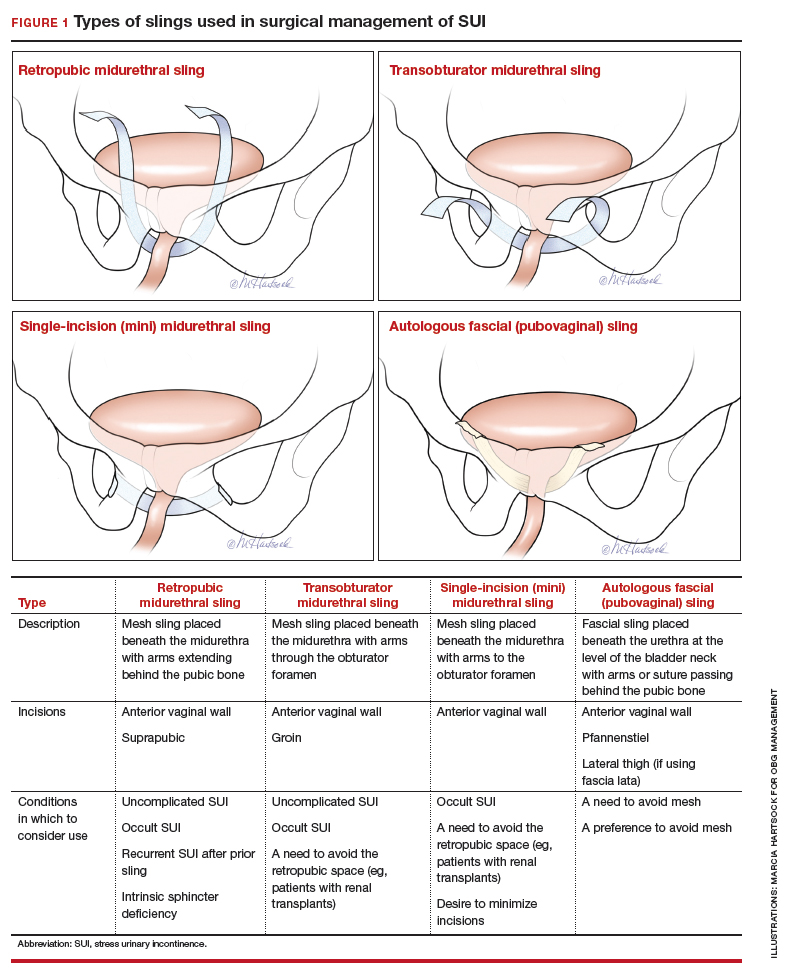

Exploring options for POP treatment: Patient selection, surgical approaches, and ways to manage risks

A number of presentations at the 2019 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium (Las Vegas, Nevada, December 12-14, 2019) focused on pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair, including anatomic considerations, the evolution of surgical procedures, and transvaginal repair. OBG M

Nonsurgical approaches for POP: A good option for the right patient

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS: What are the nonsurgical options for POP?

Mark D. Walters, MD: Women who have prolapse could, of course, choose to continue to live with the prolapse. If they desire treatment, however, the main nonsurgical option is a combination of pessary use, possibly with some estrogen, and possibly with pelvic muscle exercises. Women who have a well-fitting pessary can be managed satisfactorily for years. If possible, women should be taught to take the pessary in and out on a regular basis to minimize their long-term complications.

Dr. Gebhart: How can nonsurgical treatment options be maximized?

Beri M. Ridgeway, MD: It depends on patient commitment. This is important to assess at the first visit when you are making management decisions, because if someone is not going to attend physical therapy or not going to continue to do the exercises, the expectation for the outcome is not going to be great.

Also, if a patient feels very uncomfortable using a pessary and really does not want it, I am fine proceeding with surgery as a first-line treatment. If the patient is committed, the ideal is to educate her and connect her with the right people, either a pelvic floor physical therapist or someone in your office who will encourage her and manage pessary use.

Dr. Gebhart: It goes back to assessing patient goals and expectations.

Mickey M. Karram, MD: If you have a patient who is a good candidate for a pessary—say she has a well-supported distal vagina and maybe a cervical prolapse or an apical prolapse—and you can fit a small pessary that will sit in the upper vagina in a comfortable fashion, it is worthwhile to explain to the patient that she is a really good candidate for this option. By contrast, someone who has a wide genital hiatus and a large rectocele will not have good success with a pessary.

Dr. Gebhart: That is important: Choose your nonsurgical patients well, those who will respond to therapy and maybe not get frustrated with it.

Dr. Walters: A problem I see is that some people are good at fitting a pessary, but they do not teach how to use it very well. When I see the patient back, she says, “What’s my long term on the pessary?” I say, “If we teach you to take it in and out, you are less likely to have any problems with it, and then you can manage it for years that way. Otherwise, you have to keep visiting a practitioner to change it and that is not necessarily a good long-term option.” At the very first visit, I teach them what a pessary is, its purpose, and how to maintain it themselves. I think that gives patients the best chance for long-term satisfaction.

Dr. Gebhart: Surgery is always an option if pessary management is not satisfactory.

Dr. Ridgeway: I also tell patients, especially those uncertain about using a pessary, “Worst case, you spend a little time to figure this out, but if it works, you can avoid surgery. If it doesn’t—the risks are very low and you perhaps wasted some time—but at least you’ll know you tried the conservative management.”

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey made an excellent point earlier that it can be a diagnostic treatment strategy as well.

Dr. Karram: If you are concerned about the prolapse worsening or negatively impacting a functional problem related to the bladder or bowel, it is good to place a pessary for a short period of time. This can potentially give you an idea of how your surgery will impact a patient’s bladder or bowel function.

Continue to: Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach...

Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach

Dr. Gebhart: Would you elaborate on the surgical options for managing POP?

Dr. Walters: For women with prolapse who decide they want to have surgery, the woman and the surgeon need to make a number of decisions. Some of these include whether the uterus, if present, needs to be removed; whether the woman would like to maintain sexual function or not; whether the repair would best be done vaginally only with native tissue suturing, vaginally with some augmentation (although that is not likely in the United States at this time), or through the abdomen, usually laparoscopically or robotically with a mesh-augmented sacrocolpopexy repair.

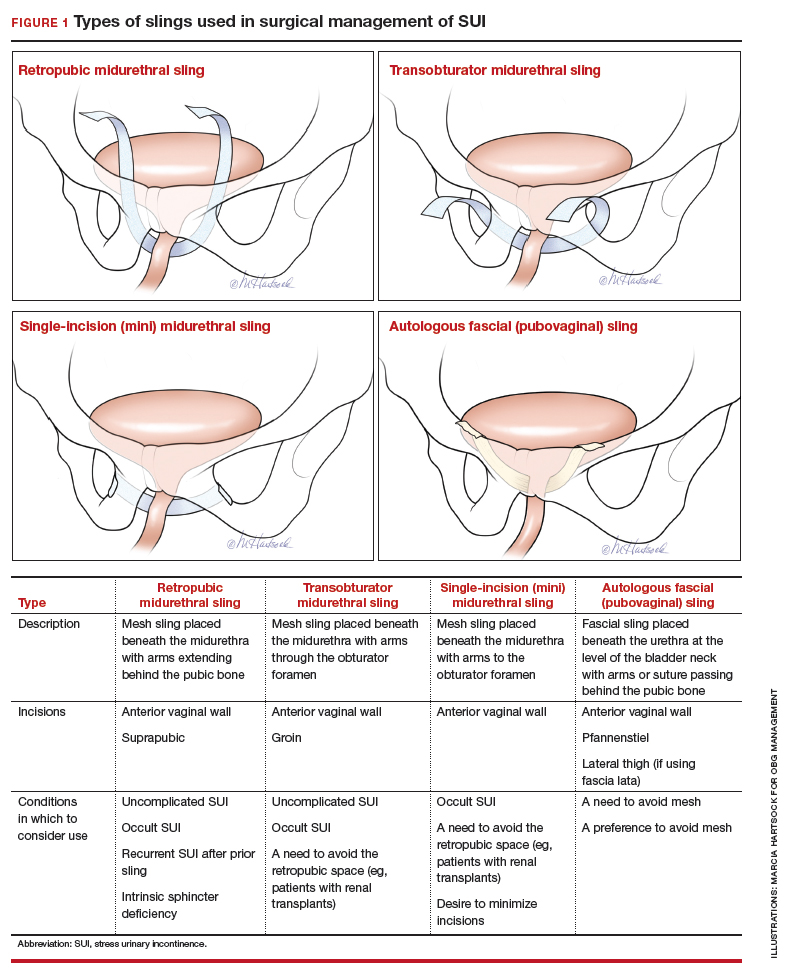

Also, we must decide whether to do additional cystocele and rectocele repairs and whether to add slings for stress incontinence, which can coexist or could develop after the prolapse repair. A lot of different decisions need to be made when choosing a prolapse repair for different women.

Dr. Ridgeway: It is shared decision-making with the patient. You need to understand her goals, the degree of prolapse, whether she has contraindications to uterine preservation, and how much risk she is willing to take.

Fundamentals of the clinical evaluation

Dr. Gebhart: For a woman who wants to manage her prolapse surgically, let us consider some fundamentals of clinical diagnosis. Take me through your office evaluation of the patient reporting prolapse symptoms—her history, yes, but from a physical exam standpoint, what is important?

Dr. Karram: You want to know if this is a primary prolapse or recurrent prolapse. You want to distinguish the various segments of the pelvic floor that are prolapsing and try to quantitate that in whatever way you would like. A standardized quantification system is useful, but you should have a system within your practice that you can standardize. Then, determine if there are coexisting functional derangements and how those are being impacted by the prolapse, because that is very important.

Take a good history, and identify how badly the prolapse bothers the patient and affects her quality of life. Understand how much she is willing to do about it. Does she just want to know what it is and has no interest in a surgical intervention, versus something she definitely wants to get corrected? Then do whatever potential testing around the bladder, and bowel, based on any functional derangements and finally determine interest in maintaining sexual function. Once all this information is obtained, a detailed discussion of surgical options can be undertaken.

Dr. Gebhart: What are your clinical pearls for a patient who has prolapse and does not describe any incontinence, voiding dysfunction, or defecatory symptoms? Do we need imaging testing of any sort or is the physical exam adequate for assessing prolapse?

Dr. Walters: When you do the standardized examination of the prolapse, it is important to measure how much prolapse affects the anterior wall of the apex and/or cervix and the posterior wall. Then note that in your notes and plan your surgery accordingly.

It is useful to have the patient fully bear down and then make your measurements; then, especially if she has a full bladder, have her cough while you hold up the prolapse with a speculum or your hand to see if she has stress urinary incontinence.

Continue to: I agree that to diagnose prolapse...

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that to diagnose prolapse, it is physical exam alone. I would not recommend any significant testing other than testing for the potential for stress incontinence.

Dr. Gebhart: Is it necessary to use the POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system) in a nonacademic private practice setting? Or are other systems, like a Baden-Walker scoring system, adequate in the everyday practice of the experienced generalist?

Dr. Walters: The Baden-Walker system actually is adequate for use in everyday practice. However, Baden-Walker is an outdated measurement system that really is not taught anymore. I think that as older physicians finish and newer doctors come in, no one will even know what Baden-Walker is.

It is better to go ahead and start learning the POP-Q system. Everyone has electronic charts now and if you learn to use the POP-Q, you can do it very quickly and get a grading system for your chart that is reproducible for everyone.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most important thing is to assess all 3 compartments and document the amount of prolapse of each compartment. A modified POP-Q is often adequate. To do this, perform a split speculum exam and use the hymen as the reference. Zero is at the hymen, +1 is 1 cm beyond the hyman. Covering the rectum, how much does the anterior compartment prolapse in reference to the hymen? Covering the anterior compartment, get an idea of what is happening posteriorly. And the crux of any decision in my mind is what is happening at the apex or to the uterus/cervix if it is still present. It is really important to document at least those 3 compartments.

Dr. Karram: I agree. The POP-Q is the ideal, but I don’t think generalists are motivated to use it. It is very important, though, to have some anatomic landmarks, as already mentioned by Dr. Ridgeway.

Choose a surgical approach based on the clinical situation

Dr. Gebhart: How do you choose the surgical approach for someone with prolapse?

Dr. Karram: Most surgeons do what they think they do best. I have spent the majority of my career operating through the vagina, and most of that involves native tissue repairs. I almost always will do a primary prolapse through the vagina and not consider augmentation except in rare circumstances. A recurrent prolapse, a prolapsed shortened vagina, scarring, or a situation that is not straightforward has to be individualized. My basic intervention initially is almost always vaginally with native tissue.

Dr. Ridgeway: For a primary prolapse repair, I also will almost always use native tissue repair as firstline. Whether that is with hysterectomy or without, most people in the long term do very well with that. At least 70% of my repairs are done with a native tissue approach.

For a woman who has a significant prolapse posthysterectomy, especially of the anterior wall or with recurrent prolapse, I offer a laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. The only other time I offer that as a primary approach would be for a younger woman with very significant prolapse. In that case, I will review risks and benefits with the patient and, using shared decision-making, offer either a native tissue repair or a sacrocolpopexy. For that patient, no matter what you do, given that she has many years to live, the chances are that she will likely need a second intervention.

Dr. Gebhart: Mark, how do you choose an approach for prolapse?

Dr. Walters: I do things pretty much the way Dr. Karram and Dr. Ridgeway do. For women who have a primary prolapse, I usually take a vaginal approach, and for recurrences I frequently do sacrocolpopexy with mesh or I refer to one of my partners who does more laparoscopic or robotic sacrocolpopexy.

Whether the patient needs a hysterectomy or not is evolving. Traditionally, hysterectomy is almost always done at the first prolapse repair. That is being reassessed in the United States to match what is happening in some other countries. It is possible to do nice primary prolapse repair vaginally or laparoscopically and leave the uterus in, in selected women who desire that.

Continue to: Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option...

Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option

Dr. Gebhart: What led up to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) market removal of mesh for transvaginal repair of POP?

Dr. Ridgeway: To clarify, it was not a recall—a word that many people use—it was an order to stop producing and distributing surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of POP.1 There is a very long history. Transvaginal mesh was introduced with the goal of improving prolapse anatomic and subjective outcomes. Over the last 13 years or so, there were adverse events that led to FDA public health notifications. Consequently, these devices were reclassified, and now require additional testing prior to approval. The newest transvaginal mesh kits were studied.

These 522 studies were completed recently and needed to show superior outcomes because, historically, the risks associated with transvaginal mesh compared to those associated with native tissue repairs are higher: higher reoperation rates, higher rates of other complications, and very minimal improvements in subjective and objective outcomes. Data were presented to the FDA, and it was deemed that these mesh kits did not improve outcomes significantly compared with native tissue repairs.

Dr. Karram: Beri, you stated that very accurately. The pro-mesh advocates were taken back by the idea that the FDA made this recommendation without allowing the outcomes to be followed longer.

Dr. Gebhart: My understanding is that the FDA had a timeline where they had to do a report and the studies had not matured to that end point; thus, they had to go with the data they had even though the studies were not completed. I think they are requesting that they be completed.

Dr. Ridgeway: Additional data will be available, some through the 522 studies, others through randomized controlled trials in which patients were already enrolled and had surgery. As far as I know, I do not think that the decision will be reversed.

Continue to: Native tissue repair and failure risk...

Native tissue repair and failure risk

Dr. Gebhart: I hear a lot that native tissue repairs fail. Mickey, as you do a lot of vaginal surgery, what are your thoughts? Should you use augmentation of some sort because native tissue fails?

Dr. Karram: There is going to be a failure rate with whatever surgery you do. I think that the failure rate with native tissue is somewhat overstated. I think a lot of that dates back to some of the things that were being promoted by mesh advocates. Initially, there was a lot of cherry-picking of native tissue data in some of those studies to promote the idea that the recurrent prolapse rates were 40% to 80%. We certainly do not see that in our patient population.

Based on our 5-year data, we have a recurrence rate of about 15% and a reoperation rate of less than 10%. That is the best I can quote based on our data. We have not followed patients longer than 5 years.

I can’t do much better than that with an augmentation; even if I get another 5% or 10% better anatomic outcome, that will be at the expense of some erosions and other complications specific to the mesh. I do think that the native tissue failure rate being promoted by a lot of individuals is a higher failure rate than what we are seeing.

Dr. Gebhart: What do you think, Mark?

Dr. Walters: Large cohort studies both at your institution, Mayo Clinic, and ours at the Cleveland Clinic mirror what Dr. Karram said, in that we have a reoperation rate somewhere between 8% and 15%. Of course, we have some failures that are stage 2 failures where patients choose not to have another operation. In general, a 10% or 12% reoperation rate at 5 to 7 years is acceptable.

Native tissue repairs probably fail at the apex a little more than mesh sacrocolpopexy. Mesh sacrocolpopexy, depending on what else you do with that operation, may have more distal vaginal failures, rates like distal rectoceles and more de novo stress urinary incontinence than we probably get with native tissue. I get some failures of the apex with native tissue repairs, but I am okay with using sacrocolpopexy as the second-line therapy in those patients.

Hysteropexy technique and pros and cons

Dr. Gebhart: Is hysteropexy a fad, or is there something to this?

Dr. Ridgeway: I do not think it is a fad. Women do feel strongly about this, and we now have data supporting this choice: randomized controlled trials of hysterectomy and prolapse repair versus hysteropexy with comparable outcomes at the short and medium term.2

The outcomes are similar, but as we said, outcomes for all prolapse repair types are not perfect. We have recurrences with sacrocolpopexy, native tissue repair, and hysteropexy. We need more data on types of hysteropexy and long-term outcomes for uterine preservation.

Dr. Walters: We have been discussing what patients think of their uterus, and some patients have very strong opinions. Some prefer to have a hysterectomy because then they don’t need to worry about cancer or do screening for cancer, and they are very happy with that. Other women with the same kind of prolapse prefer not to have a hysterectomy because philosophically they think they are better off keeping their organs. Since satisfaction is an outcome, it is useful to know what the patient wants and what she thinks about the surgical procedure.

Dr. Gebhart: For hysteropexy, do the data show that suture or a mesh augment provide an advantage one way or the other? Do we know that yet?

Dr. Walters: No, there are not enough studies with suture. There are only a few very good studies with suture hysteropexy, and they are mostly sacrospinous suture hysteropexies. Only a few studies look at mesh hysteropexy (with the Uphold device that was put on hold), or with variations of uterosacral support using strips of mesh, mostly done in other countries.

A point I want to add, if native tissue repairs fail at the apex more, why don’t you just always do sacrocolpopexy? One reason is because it might have a little higher complication rate due to the abdominal access and the fact that you are putting mesh in. If you have, for example, a 4% complication rate with the mesh but you get a better cure rate, those things balance out, and the woman may not be that much better off because of the extra complications. You have to assess the pro and con with each patient to pick what is best for her—either a more durable repair with a mesh or a little safer repair with native tissue.

Continue to: Women feel very strongly about risk...

Dr. Ridgeway: Women feel very strongly about risk. Within the same clinic I will have similar patients, and I say, “Probably in the long term this one may last a little longer but the surgery takes longer and it has a little higher complication rate.” One patient will say, “I’m not worried about the risk, I want what’s going to last the longest,” whereas a very similar patient will say, “Why would anyone pick the higher-risk operation? I want the lower risk that probably will last a long time.”

Dr. Gebhart: Beri, who should not have a hysteropexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: The biggest factor would be someone who has ever had postmenopausal bleeding. From our data, we know that if they have even had a work-up with benign results, the risk of unanticipated pathology is high. I do not recommend hysteropexy for anyone who has had postmenopausal bleeding.

For a premenopausal woman who has irregular bleeding, I also do not recommend it, because you just do not know what that future will hold. If a patient has anatomic abnormalities like large fibroids, I would not recommend it either. I would like patients to have had standard cervical cancer screening without any abnormalities for about 10 years or so.

Dr. Gebhart: What about prior cervical dysplasia?

Dr. Ridgeway: If a patient had ASCUS or low-grade dysplasia decades ago, has been normal for at least 10 years, and is currently negative for human papillomavirus, I have no problem.

Dr. Gebhart: How about women at high genetic risk for cancer?

Dr. Ridgeway: If they are at high risk for endometrial cancer, I would not recommend hysteropexy. If they are going to need an oophorectomy and/or salpingectomy for risk reduction during prolapse treatment, I usually perform a hysterectomy.

Plan surgical steps and prepare for “what if’s”

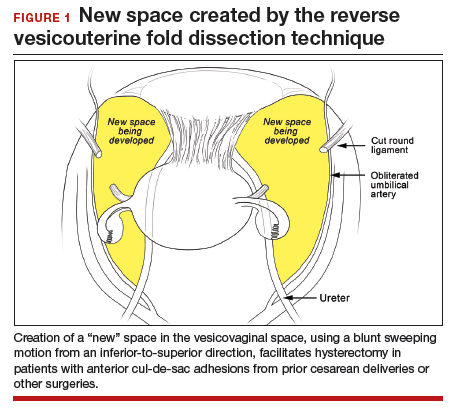

Dr. Gebhart: What tips can you provide, either regarding the evaluation or something you do surgically, that are important in a transvaginal native tissue repair?

Dr. Karram: If you have a case of posthysterectomy apical prolapse, that you think is an indication for sacrocolpopexy, in reality these are very good candidates for either sacrospinous or uterosacral suspensions. I prefer a uterosacral suspension as I feel there is less distortion of the vaginal apex compared to a sacrospinous suspension.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most critical step is setting up the OR and positioning the patient. That sets up the case for success, preventing struggles during the case. I use a high lithotomy, with careful positioning of course, but I use candy cane stirrups so that I can have an instrument stand in front of me and not struggle during the case.

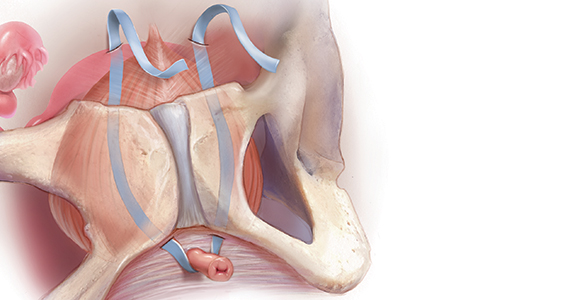

Dr. Walters: My tip for everyone who is doing native tissue surgery, whether it is high McCall colpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension or sacrocolpopexy, would be to really learn well the anatomy of each operation, including how close the ureter is, where the risk for bleeding is, and where the risk for nerve damage is.

The complications for each of these surgeries are slightly different, but there is a small risk of kinking the ureter with both uterosacral ligament suspension and the McCall, so you should do a cystoscopy as part of that operation. If you do a sacrospinous ligament suspension, use an instrument that can get a stitch into a ligament—not too close to the ischial spine and not too close to the sacrum—to avoid the risk of damage to major nerves and blood vessels and to minimize buttock and leg pain.

Continue to: Another tip is to understand...

Dr. Karram: Another tip is to understand that you are going to have potential complications intraoperatively. Think through those presurgically. You do not want to start thinking about these things and making decisions as they are happening. For example, what if I do a uterosacral suspension and I don’t see efflux of urine from the ureter? What am I going to do, and how long am I going to wait before I intervene? If I do a sacrospinous and I start to see a lot of bleeding from that area, what am I going to do? My plan would be, “I will pack the area, get extra suction, etc.” Thinking these ideas through before they occur is very helpful.

Dr. Gebhart: That is critical, to have an algorithm or a scheme in your mind. You want to think through it before it occurs because you are not always thinking as clearly when things are not going well.

I would say get good at physical examination skills in the office, then have a plan for the OR based on what you see in the office. If what is going on with the prolapse is not completely investigated and other issues are not addressed, then failure results because you did not make the diagnosis. Certainly, modify the procedure according to what you find intraoperatively, but follow through.

Indications and tips for sacrocolpopexy

Dr. Gebhart: What are the indications for sacrocolpopexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: Indications include recurrent apical prolapse, posthysterectomy prolapse, or severe prolapse in someone quite young. It is a fantastic operation with overall low risks, but this needs to be discussed with the patient.

Dr. Walters: There are some unusual circumstances—for example, the woman has a short prolapsed vagina, usually after a prior surgery—in which the best repair is a bridging piece of mesh, usually done laparoscopically, because those operations cannot be done very well vaginally to obtain a durable result.

Dr. Karram: I agree. I do not think that all recurrent prolapses mandate a sacrocolpopexy. You need to individualize, but in general the short prolapsed vagina and patients who are very young are at high risk for a recurrence.

Dr. Gebhart: An older patient might be a very good candidate, even if she had recurrence from another vaginal repair.

Beri, does the patient with a high body mass index need augmentation?

Dr. Ridgeway: That is a great question, and this has to be individualized because, while heavier patients can benefit from augmentation, in a very heavy patient, getting into that abdomen has its own set of challenges. Anatomically they get a better repair with a mesh-augmented repair like a sacrocolpopexy, but they do have increased risks. That is important to acknowledge and clarify with the patient.

Dr. Gebhart: Any surgical tip you might offer on sacrocolpopexy?

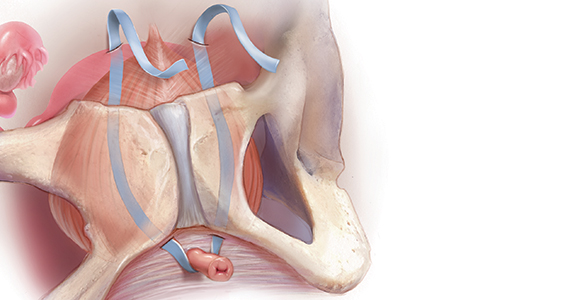

Dr. Ridgeway: Perform the operation in the same way you would an open procedure. Meaning, use the same materials, the same sutures, the same placement, and the same type of dissection in order to obtain results similar to those with an open operation. Using your assistants to manipulate the vagina and rectum is important, as well as exposure and typical careful surgical technique.

Dr. Gebhart: What is important about the placement of sutures on the anterior longitudinal ligament, and what do you need to be cognizant of?

Dr. Ridgeway: Be careful of that left common iliac vein that is a little more medial than you would expect and of the middle sacral artery, and try to differentiate between L5 and S1. In an ideal circumstance, place the suture at S1 or L5 but not the inner disc space, which is the area to avoid placement.

Historically, the recommendation is S1. Some people do L5 because of some pull out strength studies, but also because it is easier, and sometimes in that area of the anterior longitudinal ligament is much better. The key is to do enough dissection and use haptic feedback, especially with conventional laparoscopy or an open approach, to avoid placing sutures through the disc space, as there is some concern that it increases the risk for discitis or osteomyelitis in that area.

Continue to: We also have found...

Dr. Gebhart: We also have found that if you have a combined surgery with colorectal colleagues, like a rectal prolapse repair, there is a little higher risk of discitis.

Dr. Ridgeway: In my own practice I saw a combined case with a rectopexy in someone who had a biologic mesh erosion. When we reviewed the literature, a number of reported cases of discitis had either an early post-op or concurrent urinary tract infection or vaginal infection that likely predisposed them to an infection that traveled up the material.

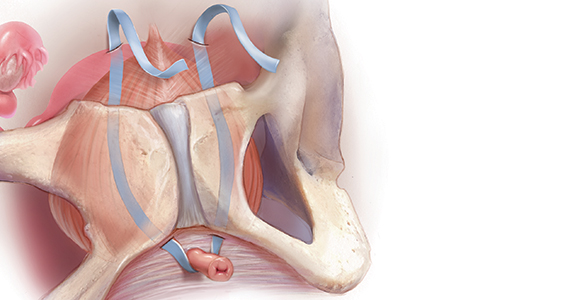

Dr. Karram: My final comment is that a sacrocolpopexy is not a few stitches or a little mesh right at the apex. If the patient has an isolated enterocele, okay, but it is a wide mesh for a reason and it should connect to the endopelvic fascia anteriorly, posteriorly. It is a mistake to suture just a little bit of the cuff and grab it and think, “I’ve done a colpopexy” when the procedure has not been executed as it should be.

Dr. Gebhart: I want to thank our expert panel and OBG M

Continue to: Some procedures call for cystoscopy...

Dr. Gebhart: Is cystoscopy necessary in patients undergoing native tissue repair or abdominal approaches to prolapse, and should the experienced generalist have this skill?

Dr. Walters: If you are going to do prolapse surgery or surgery for stress urinary incontinence, you need to learn to do cystoscopy. Almost all specialists in urogynecology and urology would do a cystoscopy at the time of a native tissue prolapse repair, a mesh-augmented prolapse repair, or a sling procedure. Whether a generalist doing simple hysterectomies needs to do cystoscopy is controversial, and it is probably based on risk assessment of the kind of hysterectomy being done. Definitely, if you are doing prolapse repair, you probably should be doing cystoscopy at the same time.

Dr. Karram: I would take it further. For certain procedures, cystoscopy is standard of care. For example, if you are doing anything around the uterosacral ligaments, whether a McCall culdoplasty or uterosacral suspension, it is standard of care. It would be a difficult medical-legal defense issue if it was not done in those cases.

To Mark’s point, it is controversial whether universal cystoscopy should be performed on every hysterectomy or every anterior to posterior repair. We are not there yet, but certainly it is in your best interest to have a very low threshold, so if you think about doing cystoscopy, you should probably do it.

Dr. Gebhart: Is cystoscopy needed in sacrocolpopexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: We know from our own data that the risk of lower urinary tract injury is very low with sacrocolpopexy. Having said that, I agree with the position statement of the American Urogynecologic Society that says, “Universal cystoscopy should be performed at the time of all pelvic reconstruction surgeries, with the exception of operations solely for posterior compartment defects.”1

Dr. Gebhart: The reality is that we just want to identify if there is a problem or not at the time of the surgery. It does not mean you have to manage it. You could get your partner, your urologist, or another person with expertise to come in to help you.

Dr. Ridgeway: Absolutely, because intraoperative identification and treatment will prevent many unfavorable outcomes in the postoperative period.

Reference

1. Cohen SA, Carberry CL, Smilen SW. American Urogynecologic Society Consensus Statement: cystoscopy at the time of prolapse repair. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:258-259.

Dr. Gebhart: If a patient is a smoker and/or utilizes tobacco and you think she is a candidate for a sacrocolpopexy, are there any special considerations? How would you counsel that patient?

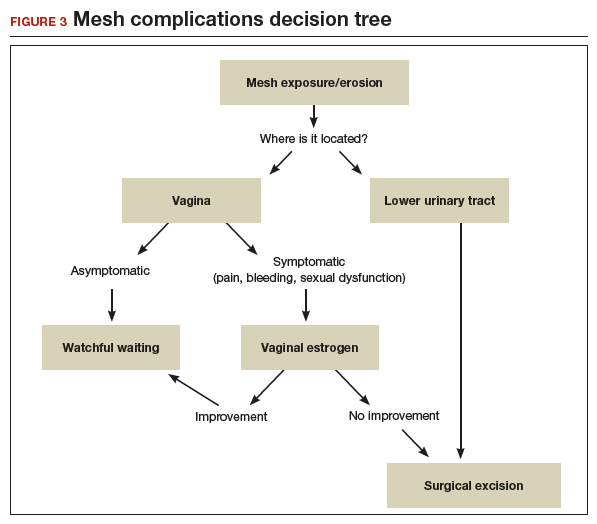

Dr. Walters: The risk of mesh erosion is high enough that I would try to not do any mesh prolapse repair in a woman who was a smoker, especially a heavy smoker. A more common situation is, would I put a polypropylene midurethral sling in that patient? I usually am willing to do that because it is still the best option compared with the no-mesh options. In a patient who would be a good candidate for sacrocolpopexy, I can usually do a no-mesh surgery and keep the risk low. I could always give the woman an option to quit smoking, but that tends not to be successful.

Dr. Gebhart: What is the risk of using mesh in a smoker?

Dr. Walters: An increased risk of erosion through the vaginal walls. I am not sure of the magnitude of risk, maybe 2 or 3 times higher. That is high enough that I probably would not take the risk except in unusual circumstances.

Dr. Ridgeway: A good amount of data show increased risk of mesh exposure for smokers. Those patients also tend to have a higher risk of prolapse recurrence because of coughing. Sacrocolpopexy is not my favorite operation to do in a smoker. I will work with the patient to quit, but often if it is the right operation, I will do it, with preoperative estrogen and appropriate conseling.

Dr. Gebhart: Is there still a role for vaginal mesh? While it is no longer being sold in the United States, could you fashion your own mesh for a prolapse procedure?

Dr. Walters: I can do pretty much everything I need to do without adding transvaginal mesh, and if I need a meshaugmented repair, then I would go with the sacrocolpopexy route. Having said that, data for hysteropexy do show that a mesh-augmented hysteropexy could have some advantages, whether you do it with a kit or some fashioned pieces of mesh. Most of the experiences with this are outside of the United States, so we need much more standardization of technique and tracking to answer that question.

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey, what are your thoughts regarding someone who thinks, “Mesh has been good for me, I want to stay with that. I’m going to cut my own mesh”? Are they assuming some liability now that companies are no longer marketing mesh for vaginal repair?

Dr. Karram: Unfortunately, I really think they are. It would be easy to be put in a legal corner and asked, the FDA felt that this should be pulled off the market, why are you still utilizing it? At the end of the day, what the FDA said was not inaccurate.

The studies have not shown a significant better outcome with mesh, and it is an extra intervention that, again, in the best of hands is going to have some issues. That is a dilemma many surgeons faced because they felt that that was their main way of treating prolapse—”they took away my way of successfully treating patients for years.” I do think it increases their medical-legal liability.

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that it does increase medical-legal liability, and I can’t imagine a situation in which I would offer that. Dr. Gebhart: There are risks with all procedures, including slings for stress incontinence, but sling use is appropriate in appropriately counseled patients.

Dr. Ridgeway: Correct. I feel very strongly that the risk profile for the midurethral sling is very different from that for transvaginal mesh. Very large data sets in large groups of people support that the outcomes are favorable and the risk profile is low. Having said that, slings are not risk free, but living with severe incontinence is not risk free either.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action to protect women's health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-action-protect-womens-health-orders-manufacturers-surgical-mesh-intended-transvaginal. April 16, 2019. Accessed January 14, 2020.

- Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: multicentre randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h3717.

A number of presentations at the 2019 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium (Las Vegas, Nevada, December 12-14, 2019) focused on pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair, including anatomic considerations, the evolution of surgical procedures, and transvaginal repair. OBG M

Nonsurgical approaches for POP: A good option for the right patient

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS: What are the nonsurgical options for POP?

Mark D. Walters, MD: Women who have prolapse could, of course, choose to continue to live with the prolapse. If they desire treatment, however, the main nonsurgical option is a combination of pessary use, possibly with some estrogen, and possibly with pelvic muscle exercises. Women who have a well-fitting pessary can be managed satisfactorily for years. If possible, women should be taught to take the pessary in and out on a regular basis to minimize their long-term complications.

Dr. Gebhart: How can nonsurgical treatment options be maximized?

Beri M. Ridgeway, MD: It depends on patient commitment. This is important to assess at the first visit when you are making management decisions, because if someone is not going to attend physical therapy or not going to continue to do the exercises, the expectation for the outcome is not going to be great.

Also, if a patient feels very uncomfortable using a pessary and really does not want it, I am fine proceeding with surgery as a first-line treatment. If the patient is committed, the ideal is to educate her and connect her with the right people, either a pelvic floor physical therapist or someone in your office who will encourage her and manage pessary use.

Dr. Gebhart: It goes back to assessing patient goals and expectations.

Mickey M. Karram, MD: If you have a patient who is a good candidate for a pessary—say she has a well-supported distal vagina and maybe a cervical prolapse or an apical prolapse—and you can fit a small pessary that will sit in the upper vagina in a comfortable fashion, it is worthwhile to explain to the patient that she is a really good candidate for this option. By contrast, someone who has a wide genital hiatus and a large rectocele will not have good success with a pessary.

Dr. Gebhart: That is important: Choose your nonsurgical patients well, those who will respond to therapy and maybe not get frustrated with it.

Dr. Walters: A problem I see is that some people are good at fitting a pessary, but they do not teach how to use it very well. When I see the patient back, she says, “What’s my long term on the pessary?” I say, “If we teach you to take it in and out, you are less likely to have any problems with it, and then you can manage it for years that way. Otherwise, you have to keep visiting a practitioner to change it and that is not necessarily a good long-term option.” At the very first visit, I teach them what a pessary is, its purpose, and how to maintain it themselves. I think that gives patients the best chance for long-term satisfaction.

Dr. Gebhart: Surgery is always an option if pessary management is not satisfactory.

Dr. Ridgeway: I also tell patients, especially those uncertain about using a pessary, “Worst case, you spend a little time to figure this out, but if it works, you can avoid surgery. If it doesn’t—the risks are very low and you perhaps wasted some time—but at least you’ll know you tried the conservative management.”

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey made an excellent point earlier that it can be a diagnostic treatment strategy as well.

Dr. Karram: If you are concerned about the prolapse worsening or negatively impacting a functional problem related to the bladder or bowel, it is good to place a pessary for a short period of time. This can potentially give you an idea of how your surgery will impact a patient’s bladder or bowel function.

Continue to: Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach...

Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach

Dr. Gebhart: Would you elaborate on the surgical options for managing POP?

Dr. Walters: For women with prolapse who decide they want to have surgery, the woman and the surgeon need to make a number of decisions. Some of these include whether the uterus, if present, needs to be removed; whether the woman would like to maintain sexual function or not; whether the repair would best be done vaginally only with native tissue suturing, vaginally with some augmentation (although that is not likely in the United States at this time), or through the abdomen, usually laparoscopically or robotically with a mesh-augmented sacrocolpopexy repair.

Also, we must decide whether to do additional cystocele and rectocele repairs and whether to add slings for stress incontinence, which can coexist or could develop after the prolapse repair. A lot of different decisions need to be made when choosing a prolapse repair for different women.

Dr. Ridgeway: It is shared decision-making with the patient. You need to understand her goals, the degree of prolapse, whether she has contraindications to uterine preservation, and how much risk she is willing to take.

Fundamentals of the clinical evaluation

Dr. Gebhart: For a woman who wants to manage her prolapse surgically, let us consider some fundamentals of clinical diagnosis. Take me through your office evaluation of the patient reporting prolapse symptoms—her history, yes, but from a physical exam standpoint, what is important?

Dr. Karram: You want to know if this is a primary prolapse or recurrent prolapse. You want to distinguish the various segments of the pelvic floor that are prolapsing and try to quantitate that in whatever way you would like. A standardized quantification system is useful, but you should have a system within your practice that you can standardize. Then, determine if there are coexisting functional derangements and how those are being impacted by the prolapse, because that is very important.

Take a good history, and identify how badly the prolapse bothers the patient and affects her quality of life. Understand how much she is willing to do about it. Does she just want to know what it is and has no interest in a surgical intervention, versus something she definitely wants to get corrected? Then do whatever potential testing around the bladder, and bowel, based on any functional derangements and finally determine interest in maintaining sexual function. Once all this information is obtained, a detailed discussion of surgical options can be undertaken.

Dr. Gebhart: What are your clinical pearls for a patient who has prolapse and does not describe any incontinence, voiding dysfunction, or defecatory symptoms? Do we need imaging testing of any sort or is the physical exam adequate for assessing prolapse?

Dr. Walters: When you do the standardized examination of the prolapse, it is important to measure how much prolapse affects the anterior wall of the apex and/or cervix and the posterior wall. Then note that in your notes and plan your surgery accordingly.

It is useful to have the patient fully bear down and then make your measurements; then, especially if she has a full bladder, have her cough while you hold up the prolapse with a speculum or your hand to see if she has stress urinary incontinence.

Continue to: I agree that to diagnose prolapse...

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that to diagnose prolapse, it is physical exam alone. I would not recommend any significant testing other than testing for the potential for stress incontinence.

Dr. Gebhart: Is it necessary to use the POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system) in a nonacademic private practice setting? Or are other systems, like a Baden-Walker scoring system, adequate in the everyday practice of the experienced generalist?

Dr. Walters: The Baden-Walker system actually is adequate for use in everyday practice. However, Baden-Walker is an outdated measurement system that really is not taught anymore. I think that as older physicians finish and newer doctors come in, no one will even know what Baden-Walker is.

It is better to go ahead and start learning the POP-Q system. Everyone has electronic charts now and if you learn to use the POP-Q, you can do it very quickly and get a grading system for your chart that is reproducible for everyone.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most important thing is to assess all 3 compartments and document the amount of prolapse of each compartment. A modified POP-Q is often adequate. To do this, perform a split speculum exam and use the hymen as the reference. Zero is at the hymen, +1 is 1 cm beyond the hyman. Covering the rectum, how much does the anterior compartment prolapse in reference to the hymen? Covering the anterior compartment, get an idea of what is happening posteriorly. And the crux of any decision in my mind is what is happening at the apex or to the uterus/cervix if it is still present. It is really important to document at least those 3 compartments.

Dr. Karram: I agree. The POP-Q is the ideal, but I don’t think generalists are motivated to use it. It is very important, though, to have some anatomic landmarks, as already mentioned by Dr. Ridgeway.

Choose a surgical approach based on the clinical situation

Dr. Gebhart: How do you choose the surgical approach for someone with prolapse?

Dr. Karram: Most surgeons do what they think they do best. I have spent the majority of my career operating through the vagina, and most of that involves native tissue repairs. I almost always will do a primary prolapse through the vagina and not consider augmentation except in rare circumstances. A recurrent prolapse, a prolapsed shortened vagina, scarring, or a situation that is not straightforward has to be individualized. My basic intervention initially is almost always vaginally with native tissue.

Dr. Ridgeway: For a primary prolapse repair, I also will almost always use native tissue repair as firstline. Whether that is with hysterectomy or without, most people in the long term do very well with that. At least 70% of my repairs are done with a native tissue approach.

For a woman who has a significant prolapse posthysterectomy, especially of the anterior wall or with recurrent prolapse, I offer a laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. The only other time I offer that as a primary approach would be for a younger woman with very significant prolapse. In that case, I will review risks and benefits with the patient and, using shared decision-making, offer either a native tissue repair or a sacrocolpopexy. For that patient, no matter what you do, given that she has many years to live, the chances are that she will likely need a second intervention.

Dr. Gebhart: Mark, how do you choose an approach for prolapse?

Dr. Walters: I do things pretty much the way Dr. Karram and Dr. Ridgeway do. For women who have a primary prolapse, I usually take a vaginal approach, and for recurrences I frequently do sacrocolpopexy with mesh or I refer to one of my partners who does more laparoscopic or robotic sacrocolpopexy.

Whether the patient needs a hysterectomy or not is evolving. Traditionally, hysterectomy is almost always done at the first prolapse repair. That is being reassessed in the United States to match what is happening in some other countries. It is possible to do nice primary prolapse repair vaginally or laparoscopically and leave the uterus in, in selected women who desire that.

Continue to: Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option...

Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option

Dr. Gebhart: What led up to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) market removal of mesh for transvaginal repair of POP?

Dr. Ridgeway: To clarify, it was not a recall—a word that many people use—it was an order to stop producing and distributing surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of POP.1 There is a very long history. Transvaginal mesh was introduced with the goal of improving prolapse anatomic and subjective outcomes. Over the last 13 years or so, there were adverse events that led to FDA public health notifications. Consequently, these devices were reclassified, and now require additional testing prior to approval. The newest transvaginal mesh kits were studied.

These 522 studies were completed recently and needed to show superior outcomes because, historically, the risks associated with transvaginal mesh compared to those associated with native tissue repairs are higher: higher reoperation rates, higher rates of other complications, and very minimal improvements in subjective and objective outcomes. Data were presented to the FDA, and it was deemed that these mesh kits did not improve outcomes significantly compared with native tissue repairs.

Dr. Karram: Beri, you stated that very accurately. The pro-mesh advocates were taken back by the idea that the FDA made this recommendation without allowing the outcomes to be followed longer.

Dr. Gebhart: My understanding is that the FDA had a timeline where they had to do a report and the studies had not matured to that end point; thus, they had to go with the data they had even though the studies were not completed. I think they are requesting that they be completed.

Dr. Ridgeway: Additional data will be available, some through the 522 studies, others through randomized controlled trials in which patients were already enrolled and had surgery. As far as I know, I do not think that the decision will be reversed.

Continue to: Native tissue repair and failure risk...

Native tissue repair and failure risk

Dr. Gebhart: I hear a lot that native tissue repairs fail. Mickey, as you do a lot of vaginal surgery, what are your thoughts? Should you use augmentation of some sort because native tissue fails?

Dr. Karram: There is going to be a failure rate with whatever surgery you do. I think that the failure rate with native tissue is somewhat overstated. I think a lot of that dates back to some of the things that were being promoted by mesh advocates. Initially, there was a lot of cherry-picking of native tissue data in some of those studies to promote the idea that the recurrent prolapse rates were 40% to 80%. We certainly do not see that in our patient population.

Based on our 5-year data, we have a recurrence rate of about 15% and a reoperation rate of less than 10%. That is the best I can quote based on our data. We have not followed patients longer than 5 years.

I can’t do much better than that with an augmentation; even if I get another 5% or 10% better anatomic outcome, that will be at the expense of some erosions and other complications specific to the mesh. I do think that the native tissue failure rate being promoted by a lot of individuals is a higher failure rate than what we are seeing.

Dr. Gebhart: What do you think, Mark?

Dr. Walters: Large cohort studies both at your institution, Mayo Clinic, and ours at the Cleveland Clinic mirror what Dr. Karram said, in that we have a reoperation rate somewhere between 8% and 15%. Of course, we have some failures that are stage 2 failures where patients choose not to have another operation. In general, a 10% or 12% reoperation rate at 5 to 7 years is acceptable.

Native tissue repairs probably fail at the apex a little more than mesh sacrocolpopexy. Mesh sacrocolpopexy, depending on what else you do with that operation, may have more distal vaginal failures, rates like distal rectoceles and more de novo stress urinary incontinence than we probably get with native tissue. I get some failures of the apex with native tissue repairs, but I am okay with using sacrocolpopexy as the second-line therapy in those patients.

Hysteropexy technique and pros and cons

Dr. Gebhart: Is hysteropexy a fad, or is there something to this?

Dr. Ridgeway: I do not think it is a fad. Women do feel strongly about this, and we now have data supporting this choice: randomized controlled trials of hysterectomy and prolapse repair versus hysteropexy with comparable outcomes at the short and medium term.2

The outcomes are similar, but as we said, outcomes for all prolapse repair types are not perfect. We have recurrences with sacrocolpopexy, native tissue repair, and hysteropexy. We need more data on types of hysteropexy and long-term outcomes for uterine preservation.

Dr. Walters: We have been discussing what patients think of their uterus, and some patients have very strong opinions. Some prefer to have a hysterectomy because then they don’t need to worry about cancer or do screening for cancer, and they are very happy with that. Other women with the same kind of prolapse prefer not to have a hysterectomy because philosophically they think they are better off keeping their organs. Since satisfaction is an outcome, it is useful to know what the patient wants and what she thinks about the surgical procedure.

Dr. Gebhart: For hysteropexy, do the data show that suture or a mesh augment provide an advantage one way or the other? Do we know that yet?

Dr. Walters: No, there are not enough studies with suture. There are only a few very good studies with suture hysteropexy, and they are mostly sacrospinous suture hysteropexies. Only a few studies look at mesh hysteropexy (with the Uphold device that was put on hold), or with variations of uterosacral support using strips of mesh, mostly done in other countries.

A point I want to add, if native tissue repairs fail at the apex more, why don’t you just always do sacrocolpopexy? One reason is because it might have a little higher complication rate due to the abdominal access and the fact that you are putting mesh in. If you have, for example, a 4% complication rate with the mesh but you get a better cure rate, those things balance out, and the woman may not be that much better off because of the extra complications. You have to assess the pro and con with each patient to pick what is best for her—either a more durable repair with a mesh or a little safer repair with native tissue.

Continue to: Women feel very strongly about risk...

Dr. Ridgeway: Women feel very strongly about risk. Within the same clinic I will have similar patients, and I say, “Probably in the long term this one may last a little longer but the surgery takes longer and it has a little higher complication rate.” One patient will say, “I’m not worried about the risk, I want what’s going to last the longest,” whereas a very similar patient will say, “Why would anyone pick the higher-risk operation? I want the lower risk that probably will last a long time.”

Dr. Gebhart: Beri, who should not have a hysteropexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: The biggest factor would be someone who has ever had postmenopausal bleeding. From our data, we know that if they have even had a work-up with benign results, the risk of unanticipated pathology is high. I do not recommend hysteropexy for anyone who has had postmenopausal bleeding.

For a premenopausal woman who has irregular bleeding, I also do not recommend it, because you just do not know what that future will hold. If a patient has anatomic abnormalities like large fibroids, I would not recommend it either. I would like patients to have had standard cervical cancer screening without any abnormalities for about 10 years or so.

Dr. Gebhart: What about prior cervical dysplasia?

Dr. Ridgeway: If a patient had ASCUS or low-grade dysplasia decades ago, has been normal for at least 10 years, and is currently negative for human papillomavirus, I have no problem.

Dr. Gebhart: How about women at high genetic risk for cancer?

Dr. Ridgeway: If they are at high risk for endometrial cancer, I would not recommend hysteropexy. If they are going to need an oophorectomy and/or salpingectomy for risk reduction during prolapse treatment, I usually perform a hysterectomy.

Plan surgical steps and prepare for “what if’s”

Dr. Gebhart: What tips can you provide, either regarding the evaluation or something you do surgically, that are important in a transvaginal native tissue repair?

Dr. Karram: If you have a case of posthysterectomy apical prolapse, that you think is an indication for sacrocolpopexy, in reality these are very good candidates for either sacrospinous or uterosacral suspensions. I prefer a uterosacral suspension as I feel there is less distortion of the vaginal apex compared to a sacrospinous suspension.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most critical step is setting up the OR and positioning the patient. That sets up the case for success, preventing struggles during the case. I use a high lithotomy, with careful positioning of course, but I use candy cane stirrups so that I can have an instrument stand in front of me and not struggle during the case.

Dr. Walters: My tip for everyone who is doing native tissue surgery, whether it is high McCall colpopexy or uterosacral ligament suspension or sacrocolpopexy, would be to really learn well the anatomy of each operation, including how close the ureter is, where the risk for bleeding is, and where the risk for nerve damage is.

The complications for each of these surgeries are slightly different, but there is a small risk of kinking the ureter with both uterosacral ligament suspension and the McCall, so you should do a cystoscopy as part of that operation. If you do a sacrospinous ligament suspension, use an instrument that can get a stitch into a ligament—not too close to the ischial spine and not too close to the sacrum—to avoid the risk of damage to major nerves and blood vessels and to minimize buttock and leg pain.

Continue to: Another tip is to understand...

Dr. Karram: Another tip is to understand that you are going to have potential complications intraoperatively. Think through those presurgically. You do not want to start thinking about these things and making decisions as they are happening. For example, what if I do a uterosacral suspension and I don’t see efflux of urine from the ureter? What am I going to do, and how long am I going to wait before I intervene? If I do a sacrospinous and I start to see a lot of bleeding from that area, what am I going to do? My plan would be, “I will pack the area, get extra suction, etc.” Thinking these ideas through before they occur is very helpful.

Dr. Gebhart: That is critical, to have an algorithm or a scheme in your mind. You want to think through it before it occurs because you are not always thinking as clearly when things are not going well.

I would say get good at physical examination skills in the office, then have a plan for the OR based on what you see in the office. If what is going on with the prolapse is not completely investigated and other issues are not addressed, then failure results because you did not make the diagnosis. Certainly, modify the procedure according to what you find intraoperatively, but follow through.

Indications and tips for sacrocolpopexy

Dr. Gebhart: What are the indications for sacrocolpopexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: Indications include recurrent apical prolapse, posthysterectomy prolapse, or severe prolapse in someone quite young. It is a fantastic operation with overall low risks, but this needs to be discussed with the patient.

Dr. Walters: There are some unusual circumstances—for example, the woman has a short prolapsed vagina, usually after a prior surgery—in which the best repair is a bridging piece of mesh, usually done laparoscopically, because those operations cannot be done very well vaginally to obtain a durable result.

Dr. Karram: I agree. I do not think that all recurrent prolapses mandate a sacrocolpopexy. You need to individualize, but in general the short prolapsed vagina and patients who are very young are at high risk for a recurrence.

Dr. Gebhart: An older patient might be a very good candidate, even if she had recurrence from another vaginal repair.

Beri, does the patient with a high body mass index need augmentation?

Dr. Ridgeway: That is a great question, and this has to be individualized because, while heavier patients can benefit from augmentation, in a very heavy patient, getting into that abdomen has its own set of challenges. Anatomically they get a better repair with a mesh-augmented repair like a sacrocolpopexy, but they do have increased risks. That is important to acknowledge and clarify with the patient.

Dr. Gebhart: Any surgical tip you might offer on sacrocolpopexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: Perform the operation in the same way you would an open procedure. Meaning, use the same materials, the same sutures, the same placement, and the same type of dissection in order to obtain results similar to those with an open operation. Using your assistants to manipulate the vagina and rectum is important, as well as exposure and typical careful surgical technique.

Dr. Gebhart: What is important about the placement of sutures on the anterior longitudinal ligament, and what do you need to be cognizant of?

Dr. Ridgeway: Be careful of that left common iliac vein that is a little more medial than you would expect and of the middle sacral artery, and try to differentiate between L5 and S1. In an ideal circumstance, place the suture at S1 or L5 but not the inner disc space, which is the area to avoid placement.

Historically, the recommendation is S1. Some people do L5 because of some pull out strength studies, but also because it is easier, and sometimes in that area of the anterior longitudinal ligament is much better. The key is to do enough dissection and use haptic feedback, especially with conventional laparoscopy or an open approach, to avoid placing sutures through the disc space, as there is some concern that it increases the risk for discitis or osteomyelitis in that area.

Continue to: We also have found...

Dr. Gebhart: We also have found that if you have a combined surgery with colorectal colleagues, like a rectal prolapse repair, there is a little higher risk of discitis.

Dr. Ridgeway: In my own practice I saw a combined case with a rectopexy in someone who had a biologic mesh erosion. When we reviewed the literature, a number of reported cases of discitis had either an early post-op or concurrent urinary tract infection or vaginal infection that likely predisposed them to an infection that traveled up the material.

Dr. Karram: My final comment is that a sacrocolpopexy is not a few stitches or a little mesh right at the apex. If the patient has an isolated enterocele, okay, but it is a wide mesh for a reason and it should connect to the endopelvic fascia anteriorly, posteriorly. It is a mistake to suture just a little bit of the cuff and grab it and think, “I’ve done a colpopexy” when the procedure has not been executed as it should be.

Dr. Gebhart: I want to thank our expert panel and OBG M

Continue to: Some procedures call for cystoscopy...

Dr. Gebhart: Is cystoscopy necessary in patients undergoing native tissue repair or abdominal approaches to prolapse, and should the experienced generalist have this skill?

Dr. Walters: If you are going to do prolapse surgery or surgery for stress urinary incontinence, you need to learn to do cystoscopy. Almost all specialists in urogynecology and urology would do a cystoscopy at the time of a native tissue prolapse repair, a mesh-augmented prolapse repair, or a sling procedure. Whether a generalist doing simple hysterectomies needs to do cystoscopy is controversial, and it is probably based on risk assessment of the kind of hysterectomy being done. Definitely, if you are doing prolapse repair, you probably should be doing cystoscopy at the same time.

Dr. Karram: I would take it further. For certain procedures, cystoscopy is standard of care. For example, if you are doing anything around the uterosacral ligaments, whether a McCall culdoplasty or uterosacral suspension, it is standard of care. It would be a difficult medical-legal defense issue if it was not done in those cases.

To Mark’s point, it is controversial whether universal cystoscopy should be performed on every hysterectomy or every anterior to posterior repair. We are not there yet, but certainly it is in your best interest to have a very low threshold, so if you think about doing cystoscopy, you should probably do it.

Dr. Gebhart: Is cystoscopy needed in sacrocolpopexy?

Dr. Ridgeway: We know from our own data that the risk of lower urinary tract injury is very low with sacrocolpopexy. Having said that, I agree with the position statement of the American Urogynecologic Society that says, “Universal cystoscopy should be performed at the time of all pelvic reconstruction surgeries, with the exception of operations solely for posterior compartment defects.”1

Dr. Gebhart: The reality is that we just want to identify if there is a problem or not at the time of the surgery. It does not mean you have to manage it. You could get your partner, your urologist, or another person with expertise to come in to help you.

Dr. Ridgeway: Absolutely, because intraoperative identification and treatment will prevent many unfavorable outcomes in the postoperative period.

Reference

1. Cohen SA, Carberry CL, Smilen SW. American Urogynecologic Society Consensus Statement: cystoscopy at the time of prolapse repair. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:258-259.

Dr. Gebhart: If a patient is a smoker and/or utilizes tobacco and you think she is a candidate for a sacrocolpopexy, are there any special considerations? How would you counsel that patient?

Dr. Walters: The risk of mesh erosion is high enough that I would try to not do any mesh prolapse repair in a woman who was a smoker, especially a heavy smoker. A more common situation is, would I put a polypropylene midurethral sling in that patient? I usually am willing to do that because it is still the best option compared with the no-mesh options. In a patient who would be a good candidate for sacrocolpopexy, I can usually do a no-mesh surgery and keep the risk low. I could always give the woman an option to quit smoking, but that tends not to be successful.

Dr. Gebhart: What is the risk of using mesh in a smoker?

Dr. Walters: An increased risk of erosion through the vaginal walls. I am not sure of the magnitude of risk, maybe 2 or 3 times higher. That is high enough that I probably would not take the risk except in unusual circumstances.

Dr. Ridgeway: A good amount of data show increased risk of mesh exposure for smokers. Those patients also tend to have a higher risk of prolapse recurrence because of coughing. Sacrocolpopexy is not my favorite operation to do in a smoker. I will work with the patient to quit, but often if it is the right operation, I will do it, with preoperative estrogen and appropriate conseling.

Dr. Gebhart: Is there still a role for vaginal mesh? While it is no longer being sold in the United States, could you fashion your own mesh for a prolapse procedure?

Dr. Walters: I can do pretty much everything I need to do without adding transvaginal mesh, and if I need a meshaugmented repair, then I would go with the sacrocolpopexy route. Having said that, data for hysteropexy do show that a mesh-augmented hysteropexy could have some advantages, whether you do it with a kit or some fashioned pieces of mesh. Most of the experiences with this are outside of the United States, so we need much more standardization of technique and tracking to answer that question.

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey, what are your thoughts regarding someone who thinks, “Mesh has been good for me, I want to stay with that. I’m going to cut my own mesh”? Are they assuming some liability now that companies are no longer marketing mesh for vaginal repair?

Dr. Karram: Unfortunately, I really think they are. It would be easy to be put in a legal corner and asked, the FDA felt that this should be pulled off the market, why are you still utilizing it? At the end of the day, what the FDA said was not inaccurate.

The studies have not shown a significant better outcome with mesh, and it is an extra intervention that, again, in the best of hands is going to have some issues. That is a dilemma many surgeons faced because they felt that that was their main way of treating prolapse—”they took away my way of successfully treating patients for years.” I do think it increases their medical-legal liability.

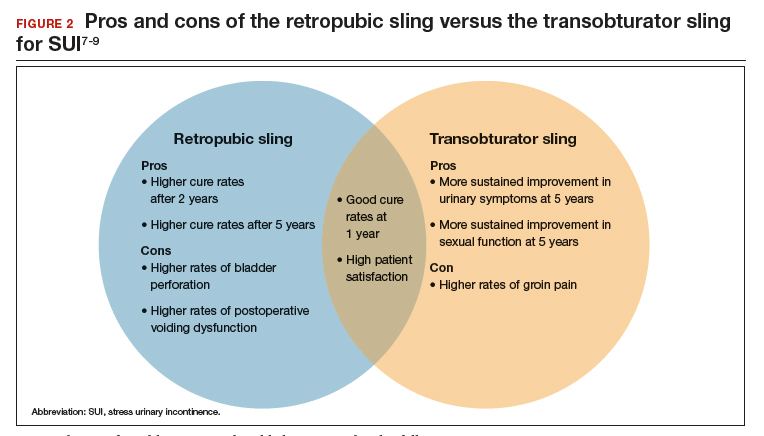

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that it does increase medical-legal liability, and I can’t imagine a situation in which I would offer that. Dr. Gebhart: There are risks with all procedures, including slings for stress incontinence, but sling use is appropriate in appropriately counseled patients.

Dr. Ridgeway: Correct. I feel very strongly that the risk profile for the midurethral sling is very different from that for transvaginal mesh. Very large data sets in large groups of people support that the outcomes are favorable and the risk profile is low. Having said that, slings are not risk free, but living with severe incontinence is not risk free either.

A number of presentations at the 2019 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium (Las Vegas, Nevada, December 12-14, 2019) focused on pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair, including anatomic considerations, the evolution of surgical procedures, and transvaginal repair. OBG M

Nonsurgical approaches for POP: A good option for the right patient

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS: What are the nonsurgical options for POP?

Mark D. Walters, MD: Women who have prolapse could, of course, choose to continue to live with the prolapse. If they desire treatment, however, the main nonsurgical option is a combination of pessary use, possibly with some estrogen, and possibly with pelvic muscle exercises. Women who have a well-fitting pessary can be managed satisfactorily for years. If possible, women should be taught to take the pessary in and out on a regular basis to minimize their long-term complications.

Dr. Gebhart: How can nonsurgical treatment options be maximized?

Beri M. Ridgeway, MD: It depends on patient commitment. This is important to assess at the first visit when you are making management decisions, because if someone is not going to attend physical therapy or not going to continue to do the exercises, the expectation for the outcome is not going to be great.

Also, if a patient feels very uncomfortable using a pessary and really does not want it, I am fine proceeding with surgery as a first-line treatment. If the patient is committed, the ideal is to educate her and connect her with the right people, either a pelvic floor physical therapist or someone in your office who will encourage her and manage pessary use.

Dr. Gebhart: It goes back to assessing patient goals and expectations.

Mickey M. Karram, MD: If you have a patient who is a good candidate for a pessary—say she has a well-supported distal vagina and maybe a cervical prolapse or an apical prolapse—and you can fit a small pessary that will sit in the upper vagina in a comfortable fashion, it is worthwhile to explain to the patient that she is a really good candidate for this option. By contrast, someone who has a wide genital hiatus and a large rectocele will not have good success with a pessary.

Dr. Gebhart: That is important: Choose your nonsurgical patients well, those who will respond to therapy and maybe not get frustrated with it.

Dr. Walters: A problem I see is that some people are good at fitting a pessary, but they do not teach how to use it very well. When I see the patient back, she says, “What’s my long term on the pessary?” I say, “If we teach you to take it in and out, you are less likely to have any problems with it, and then you can manage it for years that way. Otherwise, you have to keep visiting a practitioner to change it and that is not necessarily a good long-term option.” At the very first visit, I teach them what a pessary is, its purpose, and how to maintain it themselves. I think that gives patients the best chance for long-term satisfaction.

Dr. Gebhart: Surgery is always an option if pessary management is not satisfactory.

Dr. Ridgeway: I also tell patients, especially those uncertain about using a pessary, “Worst case, you spend a little time to figure this out, but if it works, you can avoid surgery. If it doesn’t—the risks are very low and you perhaps wasted some time—but at least you’ll know you tried the conservative management.”

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey made an excellent point earlier that it can be a diagnostic treatment strategy as well.

Dr. Karram: If you are concerned about the prolapse worsening or negatively impacting a functional problem related to the bladder or bowel, it is good to place a pessary for a short period of time. This can potentially give you an idea of how your surgery will impact a patient’s bladder or bowel function.

Continue to: Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach...

Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach

Dr. Gebhart: Would you elaborate on the surgical options for managing POP?

Dr. Walters: For women with prolapse who decide they want to have surgery, the woman and the surgeon need to make a number of decisions. Some of these include whether the uterus, if present, needs to be removed; whether the woman would like to maintain sexual function or not; whether the repair would best be done vaginally only with native tissue suturing, vaginally with some augmentation (although that is not likely in the United States at this time), or through the abdomen, usually laparoscopically or robotically with a mesh-augmented sacrocolpopexy repair.

Also, we must decide whether to do additional cystocele and rectocele repairs and whether to add slings for stress incontinence, which can coexist or could develop after the prolapse repair. A lot of different decisions need to be made when choosing a prolapse repair for different women.

Dr. Ridgeway: It is shared decision-making with the patient. You need to understand her goals, the degree of prolapse, whether she has contraindications to uterine preservation, and how much risk she is willing to take.

Fundamentals of the clinical evaluation

Dr. Gebhart: For a woman who wants to manage her prolapse surgically, let us consider some fundamentals of clinical diagnosis. Take me through your office evaluation of the patient reporting prolapse symptoms—her history, yes, but from a physical exam standpoint, what is important?

Dr. Karram: You want to know if this is a primary prolapse or recurrent prolapse. You want to distinguish the various segments of the pelvic floor that are prolapsing and try to quantitate that in whatever way you would like. A standardized quantification system is useful, but you should have a system within your practice that you can standardize. Then, determine if there are coexisting functional derangements and how those are being impacted by the prolapse, because that is very important.

Take a good history, and identify how badly the prolapse bothers the patient and affects her quality of life. Understand how much she is willing to do about it. Does she just want to know what it is and has no interest in a surgical intervention, versus something she definitely wants to get corrected? Then do whatever potential testing around the bladder, and bowel, based on any functional derangements and finally determine interest in maintaining sexual function. Once all this information is obtained, a detailed discussion of surgical options can be undertaken.

Dr. Gebhart: What are your clinical pearls for a patient who has prolapse and does not describe any incontinence, voiding dysfunction, or defecatory symptoms? Do we need imaging testing of any sort or is the physical exam adequate for assessing prolapse?

Dr. Walters: When you do the standardized examination of the prolapse, it is important to measure how much prolapse affects the anterior wall of the apex and/or cervix and the posterior wall. Then note that in your notes and plan your surgery accordingly.

It is useful to have the patient fully bear down and then make your measurements; then, especially if she has a full bladder, have her cough while you hold up the prolapse with a speculum or your hand to see if she has stress urinary incontinence.

Continue to: I agree that to diagnose prolapse...

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that to diagnose prolapse, it is physical exam alone. I would not recommend any significant testing other than testing for the potential for stress incontinence.

Dr. Gebhart: Is it necessary to use the POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system) in a nonacademic private practice setting? Or are other systems, like a Baden-Walker scoring system, adequate in the everyday practice of the experienced generalist?

Dr. Walters: The Baden-Walker system actually is adequate for use in everyday practice. However, Baden-Walker is an outdated measurement system that really is not taught anymore. I think that as older physicians finish and newer doctors come in, no one will even know what Baden-Walker is.

It is better to go ahead and start learning the POP-Q system. Everyone has electronic charts now and if you learn to use the POP-Q, you can do it very quickly and get a grading system for your chart that is reproducible for everyone.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most important thing is to assess all 3 compartments and document the amount of prolapse of each compartment. A modified POP-Q is often adequate. To do this, perform a split speculum exam and use the hymen as the reference. Zero is at the hymen, +1 is 1 cm beyond the hyman. Covering the rectum, how much does the anterior compartment prolapse in reference to the hymen? Covering the anterior compartment, get an idea of what is happening posteriorly. And the crux of any decision in my mind is what is happening at the apex or to the uterus/cervix if it is still present. It is really important to document at least those 3 compartments.

Dr. Karram: I agree. The POP-Q is the ideal, but I don’t think generalists are motivated to use it. It is very important, though, to have some anatomic landmarks, as already mentioned by Dr. Ridgeway.

Choose a surgical approach based on the clinical situation

Dr. Gebhart: How do you choose the surgical approach for someone with prolapse?

Dr. Karram: Most surgeons do what they think they do best. I have spent the majority of my career operating through the vagina, and most of that involves native tissue repairs. I almost always will do a primary prolapse through the vagina and not consider augmentation except in rare circumstances. A recurrent prolapse, a prolapsed shortened vagina, scarring, or a situation that is not straightforward has to be individualized. My basic intervention initially is almost always vaginally with native tissue.

Dr. Ridgeway: For a primary prolapse repair, I also will almost always use native tissue repair as firstline. Whether that is with hysterectomy or without, most people in the long term do very well with that. At least 70% of my repairs are done with a native tissue approach.

For a woman who has a significant prolapse posthysterectomy, especially of the anterior wall or with recurrent prolapse, I offer a laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. The only other time I offer that as a primary approach would be for a younger woman with very significant prolapse. In that case, I will review risks and benefits with the patient and, using shared decision-making, offer either a native tissue repair or a sacrocolpopexy. For that patient, no matter what you do, given that she has many years to live, the chances are that she will likely need a second intervention.

Dr. Gebhart: Mark, how do you choose an approach for prolapse?

Dr. Walters: I do things pretty much the way Dr. Karram and Dr. Ridgeway do. For women who have a primary prolapse, I usually take a vaginal approach, and for recurrences I frequently do sacrocolpopexy with mesh or I refer to one of my partners who does more laparoscopic or robotic sacrocolpopexy.

Whether the patient needs a hysterectomy or not is evolving. Traditionally, hysterectomy is almost always done at the first prolapse repair. That is being reassessed in the United States to match what is happening in some other countries. It is possible to do nice primary prolapse repair vaginally or laparoscopically and leave the uterus in, in selected women who desire that.

Continue to: Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option...

Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option

Dr. Gebhart: What led up to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) market removal of mesh for transvaginal repair of POP?