User login

Native tissue repair of POP: Surgical techniques to improve outcomes

“Take pride in your surgical work. Do it in such a way that you would be willing to sign your name to it…the operation was performed by me.”

—Raymond A. Lee, MD

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently ordered companies to cease selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair (but not for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or for abdominal sacrocolpopexy).1,2 The FDA is also requiring companies preparing premarket approval applications for mesh products for the treatment of transvaginal POP to continue safety and efficacy follow-up in existing section 522 postmarket surveillance studies.3

It is, therefore, incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to understand the surgical options that remain and perfect their surgical approach to POP to optimize patient outcomes. POP may be performed transvaginally or transabdominally, with each approach offering its own set of risks and benefits. The ability to perform both effectively allows the surgeon to tailor the approach to the condition and circumstances encountered. It is also important to realize that “cures” are elusive in POP surgery. While we can frequently alleviate patient symptoms and improve quality of life, a lifelong “cure” is an unrealistic goal for most prolapse procedures.

This article focuses on transvaginal native tissue repair,4 specifically the Mayo approach.

Watch video here

Vaginal surgery fundamentals

Before we explore the details of the Mayo technique, let’s review some basic principles of vaginal surgery. First, it is important to make a good clinical diagnosis so that you know which compartments (apex, anterior, or posterior) are involved. Although single compartment defects exist, multicompartment defects are far more common. Failing to recognize all compartment defects often results in incomplete repair, which can mean recurrent prolapse and additional interventions.

Second, exposure is critical when performing surgery by any route. You must be able to see your surgical field completely in order to properly execute your surgical approach. Table height, lighting, and retraction are all important to surgical success.

Lastly, it is important to know how to effectively execute your intended procedure. Native tissue repair is often criticized for having a high failure rate. It makes sense that mesh augmentation offers greater durability of a repair, but an effective native tissue repair will also effectively treat the majority of patients. An ineffective repair does not benefit the patient and contributes to high failure rates.

- Mesh slings for urinary incontinence and mesh use in sacrocolpopexy have not been banned by the FDA.

- Apical support is helpful to all other compartment support.

- Fixing the fascial defect between the base of the bladder and the apex will improve your anterior compartment outcomes.

- Monitor vaginal caliber throughout your posterior compartment repair.

Vaginal apex repairs

Data from the OPTIMAL trial suggest that uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous ligament fixation are equally effective in treating apical prolapse.5 Our preference is a McCall culdoplasty (uterosacral ligament plication). It allows direct visualization (internally or externally) to place apical support stitches and plicates the ligaments in the midline of the vaginal cuff to help prevent enterocele protrusion. DeLancey has described the levels of support in the female pelvis and places importance on apical support.6 Keep in mind that anterior and posterior compartment prolapse is often accompanied by apical prolapse. Therefore, treating the apex is critical for overall success.

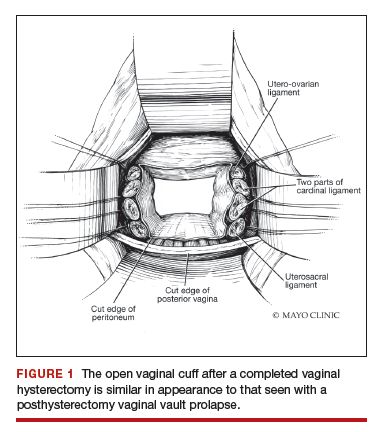

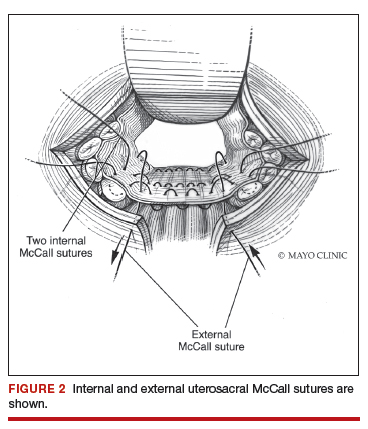

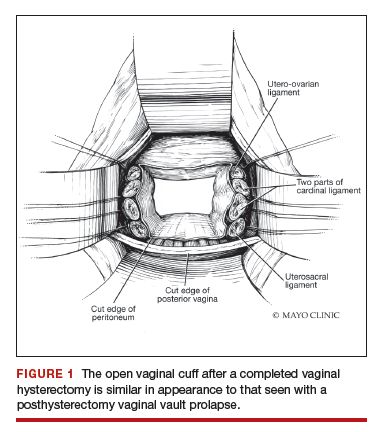

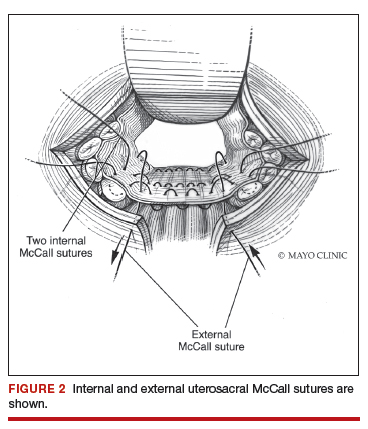

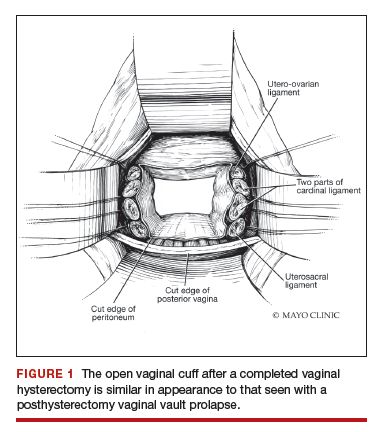

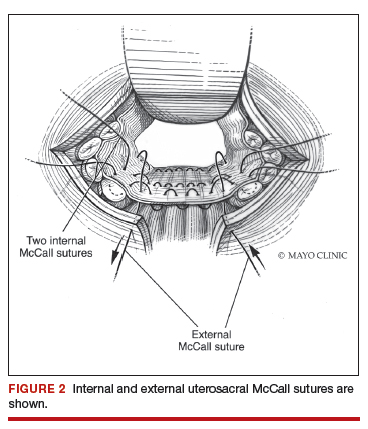

External vs internal McCall sutures: My technique. Envision the open vaginal cuff after completing a vaginal hysterectomy or after opening the vaginal cuff for a posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse (FIGURE 1). External (suture placed through the vaginal cuff epithelium into the peritoneal cavity, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and ultimately brought back out through the posterior cuff and tied) or internal (suture placed in the intraperitoneal space, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and tied internally) McCall sutures can be utilized (FIGURE 2). I prefer a combination of both. I use 0-polyglactin for external sutures, as the sutures will ultimately dissolve and not remain in the vaginal cavity. I usually place at least 2 external sutures with the lowest suture on the vaginal cuff being the deepest uterosacral stitch. Each subsequent suture is placed closer to the vaginal cuff and closer to the ends of the ligamentous stumps, starting deepest and working back toward the cuff with each stitch. I place 1 or 2 internal sutures (delayed absorbable or permanent) between my 2 external sutures. Because these sutures will be tied internally and located in the intraperitoneal space, permanent sutures may be used.

Avoiding ureteral injury: Tips for cystoscopy. A known risk of performing uterosacral ligament stitches is kinking or injury to the ureter. Therefore, cystoscopy is mandatory when performing this procedure. I tie one suture at a time starting with the internal sutures. I then perform cystoscopy after each suture tying. If I do not get ureteral spill after tying the suture, I remove and replace the suture and repeat cystoscopy until normal bilateral ureteral spill is achieved.

Key points for uterosacral ligament suspension. Achieving apical support at this point gives me the ability to build my anterior and posterior repair procedures off of this support. It is critical when performing uterosacral ligament suspension that you define the space between the ureter and rectum on each side. (Elevation of the cardinal pedicle and medial retraction of the rectum facilitate this.) The ligament runs down toward the sacrum when the patient is supine. You must follow that trajectory to be successful and avoid injury. One must also be careful not to be too deep on the ligament, as plication at that level may cause defecatory dysfunction.

Continue to: Anterior compartment repairs...

Anterior compartment repairs

The anterior compartment seems the most susceptible to forces within the pelvis and is a common site of prolapse. Many theories exist as to what causes a cystocele—distension, displacement, detachment, etc. While paravaginal defects exist, I believe that most cystoceles arise horizontally at the base of the bladder as the anterior endopelvic fascia detaches from the apex or cervix. The tissue then attenuates as the hernia progresses.

For surgical success: Make certain your repair addresses re-establishing continuity of the anterior endopelvic fascia with the fascia and ligaments at the vaginal apex; it will increase your success in treating anterior compartment prolapse.

We prefer to mobilize the epithelium in the midline from the vaginal apex to the mid‑urethra (if performing a midurethral sling, we stop short of the bladder neck and perform a separate suburethral incision). When incising the epithelium in the midline, the underlying fascia is also split in the midline, creating a midline defect. Once the epithelium is split and mobilized laterally off the underlying fascia, we can begin reconstruction.

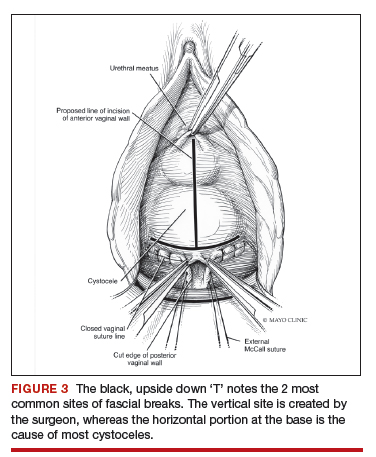

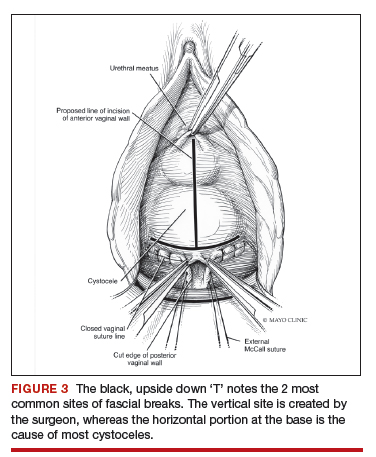

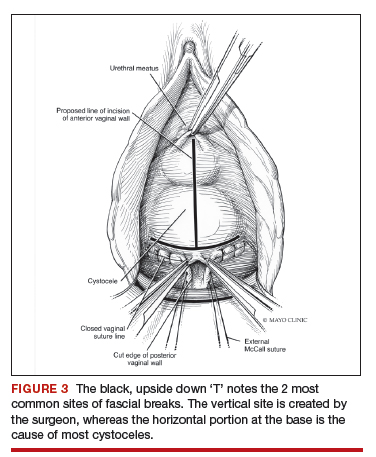

The midline fascial defect that was just created is closed with a running 2-0 polyglactin from just beneath the bladder neck down to and including the fascia and uterosacral ligaments at the apex. This is accomplished in an upside down ‘T’ orientation (FIGURE 3). It is critical that the fascia is reunited at the base or you will leave the patient with a hernia.

For surgical success: To check intraoperatively that the fascia is reunited at the base, try to place an index finger between the base of the cystocele repair and the apex. If you can insert your finger, that is where the hernia still exists. If you meet resistance with your finger, you are palpating reunification of the anterior and apical fascia.

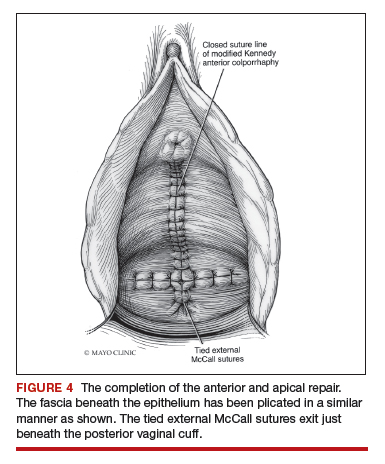

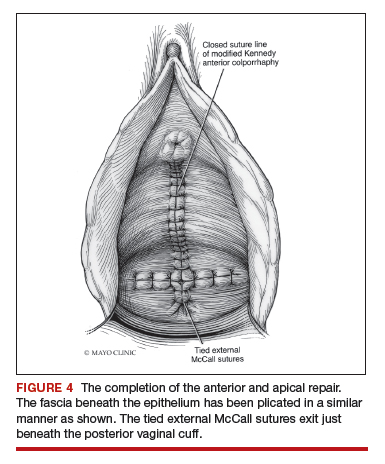

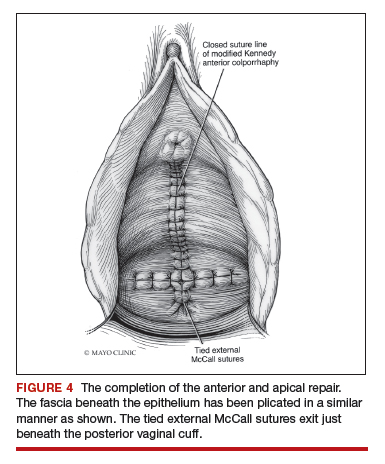

Technique for Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. If the patient has mild incontinence that does not require a sling procedure, we now complete the second portion of the anterior repair starting with a Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. Utilizing interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture, vertical bites are taken periurethrally, starting at the midurethra and then the bladder neck. This nicely supports the urethra and proximal bladder neck and is very helpful for mild incontinence or for prophylactic benefit. Then starting beneath the bladder neck, the fascia is plicated again in the midline, reinforcing the suture line of the inverse ‘T’ with 2-0 polyglactin. The redundant epithelium is trimmed and reapproximated with interrupted 2-0 polyglactin (FIGURE 4). We tend to be more aggressive by adding the Kelly-Kennedy plication, which can lead to temporary voiding delay. We offer placement of a suprapubic catheter at the time of surgery or self-intermittent catherization.

Lastly, given that we have just dissected and then plicated the tissues beneath the bladder, I like to perform cystoscopy to be certain the bladder has not been violated. It is also important not to over-plicate the anterior fascia so that the sutures shear through the fascia and weaken the support or narrow the vaginal lumen.

Continue to: Posterior compartment repairs...

Posterior compartment repairs

Like with the anterior compartment, opinions differ as to the site of posterior compartment prolapse. Midline, lateral, distal, and site-specific defects and surgical approaches have been described. Research suggests that there is no benefit to the use of mesh in the posterior compartment.7 It is very important to recognize that over-plication of the posterior compartment can lead to narrowing/stricture and dyspareunia. Therefore, monitor vaginal caliber throughout repair of the posterior compartment.

Although we believe that a midline defect in the endopelvic fascia is primarily responsible for rectoceles, we also appreciate that the fascia must be reconstructed all the way to the perineal body and that narrowing the genital hiatus is very important and often underappreciated (FIGURE 5). Thus, perineal reconstruction is universally performed. I will emphasize again that reconstruction must be performed while also monitoring vaginal caliber. If it is too tight with the patient under anesthesia, it will be too tight when the patient recovers. Avoidance is the best option. If the patient does not desire a functional vagina (eg, an elderly patient), then narrowing is a desired goal.

Perineal reconstruction technique and tips for success

A retractor at 12 o’clock to support the apex and anterior wall can be helpful for visualization in the posterior compartment. We start with a v-shaped incision on the perineum. The width is determined by how much you want to build up the perineum and narrow the vagina (the wider the incision, the more building up of the perineal body and vaginal narrowing). A strip of epithelium is then mobilized in the midline (be careful not to excise too much). This dissection is carried all the way up the midline to just short of the tied apical suspension sutures at the posterior vaginal apex. The posterior dissection tends to be the most vascular in my experience.

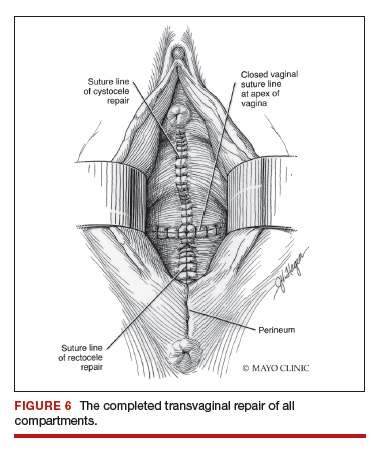

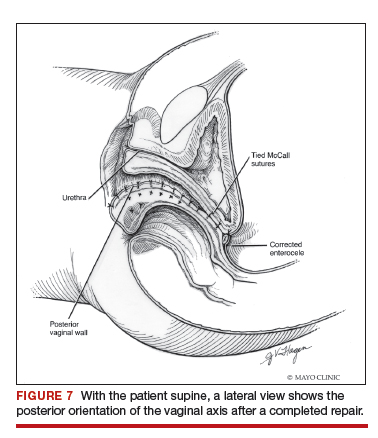

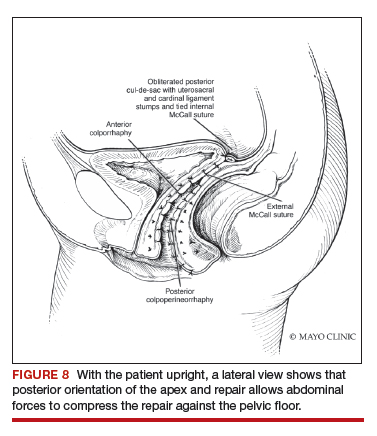

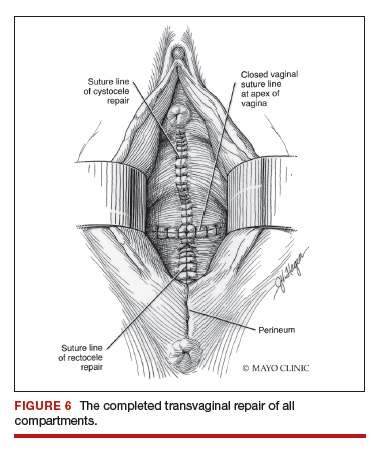

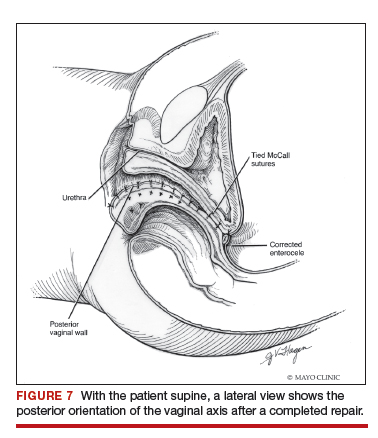

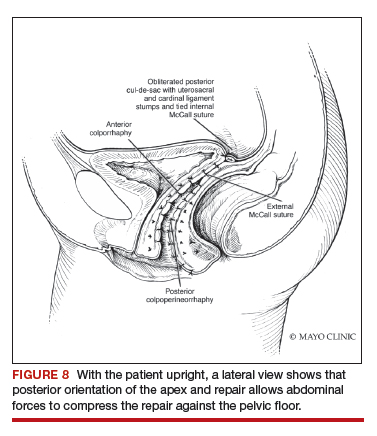

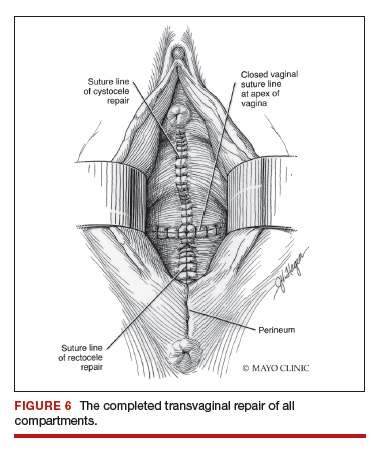

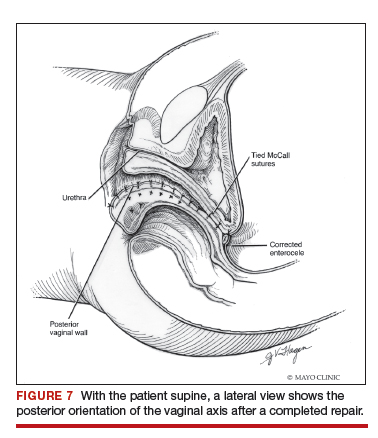

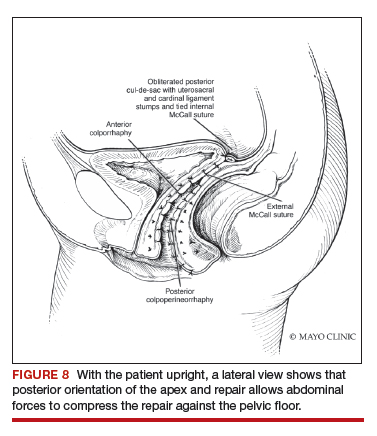

Utilize cautery to obtain hemostasis along your dissection margins while protecting the underlying rectum. We have not found it necessary to dissect the posterior epithelium off the underlying fascia (that is an option at this point, however, if you feel more comfortable doing this). With an index finger in the vagina, compressing the rectum posteriorly, interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture is placed through the epithelium and underlying fascia (avoiding the rectum) on one side, then the other, and then tied. The next sutures are placed utilizing the same technique, and the caliber of the vagina is noted with the placement of each suture (if it is too tight, then remove and replace the suture and recheck). It is important to realize you want to plicate the fascia in the midline and not perform an aggressive levatorplasty that could lead to muscle pain. Additionally, each suture should get the same purchase of tissue on each side, and the spacing of each suture should be uniform, like rungs on a ladder. Ultimately, the repair is carried down to the hymenal ring. At this point, the perineal reconstruction is performed, plicating the perineal body in the midline with deeper horizontal sutures and then closing the perineal skin with interrupted or subcuticular sutures (FIGURE 6). Completion of these repairs should orient the vagina toward the hollow of the sacrum (FIGURE 7), allowing downward forces to compress the vaginal supports posteriorly onto the pelvic floor instead of forcing it out the vaginal lumen (FIGURE 8).

Our patients generally stay in the hospital overnight, and we place a vaginal pack to provide topical pressure throughout the vagina overnight. We tell patients no lifting more than 15 lb and no intercourse for 6 weeks. While we do not tend to use hydrodissection in our repairs, it is a perfectly acceptable option.

Continue to: Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques...

Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques

Given the recent FDA ban on the sale of transvaginal mesh for POP and the public’s negative perception of mesh (based often on misleading information in the media), it is incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to invest in learning or relearning effective native tissue techniques for the transvaginal treatment of POP. While not perfect, they offer an effective nonmesh treatment option for many of our patients.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. . Published April 16, 2019. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecological surgical mesh implants. . Published July 10, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Effective date of requirement for premarket approval for surgical mesh for transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/01/05/2015-33163/effective-date-of-requirement-for-premarket-approval-for-surgical-mesh-for-transvaginal-pelvic-organ. Published January 5, 2016. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- Lee RA. Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA; 1992.

- Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1554-1565.

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 part 1):1717-1728.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762- 1771.

“Take pride in your surgical work. Do it in such a way that you would be willing to sign your name to it…the operation was performed by me.”

—Raymond A. Lee, MD

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently ordered companies to cease selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair (but not for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or for abdominal sacrocolpopexy).1,2 The FDA is also requiring companies preparing premarket approval applications for mesh products for the treatment of transvaginal POP to continue safety and efficacy follow-up in existing section 522 postmarket surveillance studies.3

It is, therefore, incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to understand the surgical options that remain and perfect their surgical approach to POP to optimize patient outcomes. POP may be performed transvaginally or transabdominally, with each approach offering its own set of risks and benefits. The ability to perform both effectively allows the surgeon to tailor the approach to the condition and circumstances encountered. It is also important to realize that “cures” are elusive in POP surgery. While we can frequently alleviate patient symptoms and improve quality of life, a lifelong “cure” is an unrealistic goal for most prolapse procedures.

This article focuses on transvaginal native tissue repair,4 specifically the Mayo approach.

Watch video here

Vaginal surgery fundamentals

Before we explore the details of the Mayo technique, let’s review some basic principles of vaginal surgery. First, it is important to make a good clinical diagnosis so that you know which compartments (apex, anterior, or posterior) are involved. Although single compartment defects exist, multicompartment defects are far more common. Failing to recognize all compartment defects often results in incomplete repair, which can mean recurrent prolapse and additional interventions.

Second, exposure is critical when performing surgery by any route. You must be able to see your surgical field completely in order to properly execute your surgical approach. Table height, lighting, and retraction are all important to surgical success.

Lastly, it is important to know how to effectively execute your intended procedure. Native tissue repair is often criticized for having a high failure rate. It makes sense that mesh augmentation offers greater durability of a repair, but an effective native tissue repair will also effectively treat the majority of patients. An ineffective repair does not benefit the patient and contributes to high failure rates.

- Mesh slings for urinary incontinence and mesh use in sacrocolpopexy have not been banned by the FDA.

- Apical support is helpful to all other compartment support.

- Fixing the fascial defect between the base of the bladder and the apex will improve your anterior compartment outcomes.

- Monitor vaginal caliber throughout your posterior compartment repair.

Vaginal apex repairs

Data from the OPTIMAL trial suggest that uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous ligament fixation are equally effective in treating apical prolapse.5 Our preference is a McCall culdoplasty (uterosacral ligament plication). It allows direct visualization (internally or externally) to place apical support stitches and plicates the ligaments in the midline of the vaginal cuff to help prevent enterocele protrusion. DeLancey has described the levels of support in the female pelvis and places importance on apical support.6 Keep in mind that anterior and posterior compartment prolapse is often accompanied by apical prolapse. Therefore, treating the apex is critical for overall success.

External vs internal McCall sutures: My technique. Envision the open vaginal cuff after completing a vaginal hysterectomy or after opening the vaginal cuff for a posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse (FIGURE 1). External (suture placed through the vaginal cuff epithelium into the peritoneal cavity, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and ultimately brought back out through the posterior cuff and tied) or internal (suture placed in the intraperitoneal space, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and tied internally) McCall sutures can be utilized (FIGURE 2). I prefer a combination of both. I use 0-polyglactin for external sutures, as the sutures will ultimately dissolve and not remain in the vaginal cavity. I usually place at least 2 external sutures with the lowest suture on the vaginal cuff being the deepest uterosacral stitch. Each subsequent suture is placed closer to the vaginal cuff and closer to the ends of the ligamentous stumps, starting deepest and working back toward the cuff with each stitch. I place 1 or 2 internal sutures (delayed absorbable or permanent) between my 2 external sutures. Because these sutures will be tied internally and located in the intraperitoneal space, permanent sutures may be used.

Avoiding ureteral injury: Tips for cystoscopy. A known risk of performing uterosacral ligament stitches is kinking or injury to the ureter. Therefore, cystoscopy is mandatory when performing this procedure. I tie one suture at a time starting with the internal sutures. I then perform cystoscopy after each suture tying. If I do not get ureteral spill after tying the suture, I remove and replace the suture and repeat cystoscopy until normal bilateral ureteral spill is achieved.

Key points for uterosacral ligament suspension. Achieving apical support at this point gives me the ability to build my anterior and posterior repair procedures off of this support. It is critical when performing uterosacral ligament suspension that you define the space between the ureter and rectum on each side. (Elevation of the cardinal pedicle and medial retraction of the rectum facilitate this.) The ligament runs down toward the sacrum when the patient is supine. You must follow that trajectory to be successful and avoid injury. One must also be careful not to be too deep on the ligament, as plication at that level may cause defecatory dysfunction.

Continue to: Anterior compartment repairs...

Anterior compartment repairs

The anterior compartment seems the most susceptible to forces within the pelvis and is a common site of prolapse. Many theories exist as to what causes a cystocele—distension, displacement, detachment, etc. While paravaginal defects exist, I believe that most cystoceles arise horizontally at the base of the bladder as the anterior endopelvic fascia detaches from the apex or cervix. The tissue then attenuates as the hernia progresses.

For surgical success: Make certain your repair addresses re-establishing continuity of the anterior endopelvic fascia with the fascia and ligaments at the vaginal apex; it will increase your success in treating anterior compartment prolapse.

We prefer to mobilize the epithelium in the midline from the vaginal apex to the mid‑urethra (if performing a midurethral sling, we stop short of the bladder neck and perform a separate suburethral incision). When incising the epithelium in the midline, the underlying fascia is also split in the midline, creating a midline defect. Once the epithelium is split and mobilized laterally off the underlying fascia, we can begin reconstruction.

The midline fascial defect that was just created is closed with a running 2-0 polyglactin from just beneath the bladder neck down to and including the fascia and uterosacral ligaments at the apex. This is accomplished in an upside down ‘T’ orientation (FIGURE 3). It is critical that the fascia is reunited at the base or you will leave the patient with a hernia.

For surgical success: To check intraoperatively that the fascia is reunited at the base, try to place an index finger between the base of the cystocele repair and the apex. If you can insert your finger, that is where the hernia still exists. If you meet resistance with your finger, you are palpating reunification of the anterior and apical fascia.

Technique for Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. If the patient has mild incontinence that does not require a sling procedure, we now complete the second portion of the anterior repair starting with a Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. Utilizing interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture, vertical bites are taken periurethrally, starting at the midurethra and then the bladder neck. This nicely supports the urethra and proximal bladder neck and is very helpful for mild incontinence or for prophylactic benefit. Then starting beneath the bladder neck, the fascia is plicated again in the midline, reinforcing the suture line of the inverse ‘T’ with 2-0 polyglactin. The redundant epithelium is trimmed and reapproximated with interrupted 2-0 polyglactin (FIGURE 4). We tend to be more aggressive by adding the Kelly-Kennedy plication, which can lead to temporary voiding delay. We offer placement of a suprapubic catheter at the time of surgery or self-intermittent catherization.

Lastly, given that we have just dissected and then plicated the tissues beneath the bladder, I like to perform cystoscopy to be certain the bladder has not been violated. It is also important not to over-plicate the anterior fascia so that the sutures shear through the fascia and weaken the support or narrow the vaginal lumen.

Continue to: Posterior compartment repairs...

Posterior compartment repairs

Like with the anterior compartment, opinions differ as to the site of posterior compartment prolapse. Midline, lateral, distal, and site-specific defects and surgical approaches have been described. Research suggests that there is no benefit to the use of mesh in the posterior compartment.7 It is very important to recognize that over-plication of the posterior compartment can lead to narrowing/stricture and dyspareunia. Therefore, monitor vaginal caliber throughout repair of the posterior compartment.

Although we believe that a midline defect in the endopelvic fascia is primarily responsible for rectoceles, we also appreciate that the fascia must be reconstructed all the way to the perineal body and that narrowing the genital hiatus is very important and often underappreciated (FIGURE 5). Thus, perineal reconstruction is universally performed. I will emphasize again that reconstruction must be performed while also monitoring vaginal caliber. If it is too tight with the patient under anesthesia, it will be too tight when the patient recovers. Avoidance is the best option. If the patient does not desire a functional vagina (eg, an elderly patient), then narrowing is a desired goal.

Perineal reconstruction technique and tips for success

A retractor at 12 o’clock to support the apex and anterior wall can be helpful for visualization in the posterior compartment. We start with a v-shaped incision on the perineum. The width is determined by how much you want to build up the perineum and narrow the vagina (the wider the incision, the more building up of the perineal body and vaginal narrowing). A strip of epithelium is then mobilized in the midline (be careful not to excise too much). This dissection is carried all the way up the midline to just short of the tied apical suspension sutures at the posterior vaginal apex. The posterior dissection tends to be the most vascular in my experience.

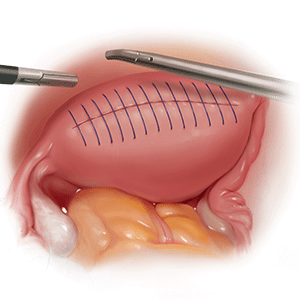

Utilize cautery to obtain hemostasis along your dissection margins while protecting the underlying rectum. We have not found it necessary to dissect the posterior epithelium off the underlying fascia (that is an option at this point, however, if you feel more comfortable doing this). With an index finger in the vagina, compressing the rectum posteriorly, interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture is placed through the epithelium and underlying fascia (avoiding the rectum) on one side, then the other, and then tied. The next sutures are placed utilizing the same technique, and the caliber of the vagina is noted with the placement of each suture (if it is too tight, then remove and replace the suture and recheck). It is important to realize you want to plicate the fascia in the midline and not perform an aggressive levatorplasty that could lead to muscle pain. Additionally, each suture should get the same purchase of tissue on each side, and the spacing of each suture should be uniform, like rungs on a ladder. Ultimately, the repair is carried down to the hymenal ring. At this point, the perineal reconstruction is performed, plicating the perineal body in the midline with deeper horizontal sutures and then closing the perineal skin with interrupted or subcuticular sutures (FIGURE 6). Completion of these repairs should orient the vagina toward the hollow of the sacrum (FIGURE 7), allowing downward forces to compress the vaginal supports posteriorly onto the pelvic floor instead of forcing it out the vaginal lumen (FIGURE 8).

Our patients generally stay in the hospital overnight, and we place a vaginal pack to provide topical pressure throughout the vagina overnight. We tell patients no lifting more than 15 lb and no intercourse for 6 weeks. While we do not tend to use hydrodissection in our repairs, it is a perfectly acceptable option.

Continue to: Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques...

Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques

Given the recent FDA ban on the sale of transvaginal mesh for POP and the public’s negative perception of mesh (based often on misleading information in the media), it is incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to invest in learning or relearning effective native tissue techniques for the transvaginal treatment of POP. While not perfect, they offer an effective nonmesh treatment option for many of our patients.

“Take pride in your surgical work. Do it in such a way that you would be willing to sign your name to it…the operation was performed by me.”

—Raymond A. Lee, MD

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently ordered companies to cease selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair (but not for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or for abdominal sacrocolpopexy).1,2 The FDA is also requiring companies preparing premarket approval applications for mesh products for the treatment of transvaginal POP to continue safety and efficacy follow-up in existing section 522 postmarket surveillance studies.3

It is, therefore, incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to understand the surgical options that remain and perfect their surgical approach to POP to optimize patient outcomes. POP may be performed transvaginally or transabdominally, with each approach offering its own set of risks and benefits. The ability to perform both effectively allows the surgeon to tailor the approach to the condition and circumstances encountered. It is also important to realize that “cures” are elusive in POP surgery. While we can frequently alleviate patient symptoms and improve quality of life, a lifelong “cure” is an unrealistic goal for most prolapse procedures.

This article focuses on transvaginal native tissue repair,4 specifically the Mayo approach.

Watch video here

Vaginal surgery fundamentals

Before we explore the details of the Mayo technique, let’s review some basic principles of vaginal surgery. First, it is important to make a good clinical diagnosis so that you know which compartments (apex, anterior, or posterior) are involved. Although single compartment defects exist, multicompartment defects are far more common. Failing to recognize all compartment defects often results in incomplete repair, which can mean recurrent prolapse and additional interventions.

Second, exposure is critical when performing surgery by any route. You must be able to see your surgical field completely in order to properly execute your surgical approach. Table height, lighting, and retraction are all important to surgical success.

Lastly, it is important to know how to effectively execute your intended procedure. Native tissue repair is often criticized for having a high failure rate. It makes sense that mesh augmentation offers greater durability of a repair, but an effective native tissue repair will also effectively treat the majority of patients. An ineffective repair does not benefit the patient and contributes to high failure rates.

- Mesh slings for urinary incontinence and mesh use in sacrocolpopexy have not been banned by the FDA.

- Apical support is helpful to all other compartment support.

- Fixing the fascial defect between the base of the bladder and the apex will improve your anterior compartment outcomes.

- Monitor vaginal caliber throughout your posterior compartment repair.

Vaginal apex repairs

Data from the OPTIMAL trial suggest that uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous ligament fixation are equally effective in treating apical prolapse.5 Our preference is a McCall culdoplasty (uterosacral ligament plication). It allows direct visualization (internally or externally) to place apical support stitches and plicates the ligaments in the midline of the vaginal cuff to help prevent enterocele protrusion. DeLancey has described the levels of support in the female pelvis and places importance on apical support.6 Keep in mind that anterior and posterior compartment prolapse is often accompanied by apical prolapse. Therefore, treating the apex is critical for overall success.

External vs internal McCall sutures: My technique. Envision the open vaginal cuff after completing a vaginal hysterectomy or after opening the vaginal cuff for a posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse (FIGURE 1). External (suture placed through the vaginal cuff epithelium into the peritoneal cavity, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and ultimately brought back out through the posterior cuff and tied) or internal (suture placed in the intraperitoneal space, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and tied internally) McCall sutures can be utilized (FIGURE 2). I prefer a combination of both. I use 0-polyglactin for external sutures, as the sutures will ultimately dissolve and not remain in the vaginal cavity. I usually place at least 2 external sutures with the lowest suture on the vaginal cuff being the deepest uterosacral stitch. Each subsequent suture is placed closer to the vaginal cuff and closer to the ends of the ligamentous stumps, starting deepest and working back toward the cuff with each stitch. I place 1 or 2 internal sutures (delayed absorbable or permanent) between my 2 external sutures. Because these sutures will be tied internally and located in the intraperitoneal space, permanent sutures may be used.

Avoiding ureteral injury: Tips for cystoscopy. A known risk of performing uterosacral ligament stitches is kinking or injury to the ureter. Therefore, cystoscopy is mandatory when performing this procedure. I tie one suture at a time starting with the internal sutures. I then perform cystoscopy after each suture tying. If I do not get ureteral spill after tying the suture, I remove and replace the suture and repeat cystoscopy until normal bilateral ureteral spill is achieved.

Key points for uterosacral ligament suspension. Achieving apical support at this point gives me the ability to build my anterior and posterior repair procedures off of this support. It is critical when performing uterosacral ligament suspension that you define the space between the ureter and rectum on each side. (Elevation of the cardinal pedicle and medial retraction of the rectum facilitate this.) The ligament runs down toward the sacrum when the patient is supine. You must follow that trajectory to be successful and avoid injury. One must also be careful not to be too deep on the ligament, as plication at that level may cause defecatory dysfunction.

Continue to: Anterior compartment repairs...

Anterior compartment repairs

The anterior compartment seems the most susceptible to forces within the pelvis and is a common site of prolapse. Many theories exist as to what causes a cystocele—distension, displacement, detachment, etc. While paravaginal defects exist, I believe that most cystoceles arise horizontally at the base of the bladder as the anterior endopelvic fascia detaches from the apex or cervix. The tissue then attenuates as the hernia progresses.

For surgical success: Make certain your repair addresses re-establishing continuity of the anterior endopelvic fascia with the fascia and ligaments at the vaginal apex; it will increase your success in treating anterior compartment prolapse.

We prefer to mobilize the epithelium in the midline from the vaginal apex to the mid‑urethra (if performing a midurethral sling, we stop short of the bladder neck and perform a separate suburethral incision). When incising the epithelium in the midline, the underlying fascia is also split in the midline, creating a midline defect. Once the epithelium is split and mobilized laterally off the underlying fascia, we can begin reconstruction.

The midline fascial defect that was just created is closed with a running 2-0 polyglactin from just beneath the bladder neck down to and including the fascia and uterosacral ligaments at the apex. This is accomplished in an upside down ‘T’ orientation (FIGURE 3). It is critical that the fascia is reunited at the base or you will leave the patient with a hernia.

For surgical success: To check intraoperatively that the fascia is reunited at the base, try to place an index finger between the base of the cystocele repair and the apex. If you can insert your finger, that is where the hernia still exists. If you meet resistance with your finger, you are palpating reunification of the anterior and apical fascia.

Technique for Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. If the patient has mild incontinence that does not require a sling procedure, we now complete the second portion of the anterior repair starting with a Kelly-Kennedy bladder neck plication. Utilizing interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture, vertical bites are taken periurethrally, starting at the midurethra and then the bladder neck. This nicely supports the urethra and proximal bladder neck and is very helpful for mild incontinence or for prophylactic benefit. Then starting beneath the bladder neck, the fascia is plicated again in the midline, reinforcing the suture line of the inverse ‘T’ with 2-0 polyglactin. The redundant epithelium is trimmed and reapproximated with interrupted 2-0 polyglactin (FIGURE 4). We tend to be more aggressive by adding the Kelly-Kennedy plication, which can lead to temporary voiding delay. We offer placement of a suprapubic catheter at the time of surgery or self-intermittent catherization.

Lastly, given that we have just dissected and then plicated the tissues beneath the bladder, I like to perform cystoscopy to be certain the bladder has not been violated. It is also important not to over-plicate the anterior fascia so that the sutures shear through the fascia and weaken the support or narrow the vaginal lumen.

Continue to: Posterior compartment repairs...

Posterior compartment repairs

Like with the anterior compartment, opinions differ as to the site of posterior compartment prolapse. Midline, lateral, distal, and site-specific defects and surgical approaches have been described. Research suggests that there is no benefit to the use of mesh in the posterior compartment.7 It is very important to recognize that over-plication of the posterior compartment can lead to narrowing/stricture and dyspareunia. Therefore, monitor vaginal caliber throughout repair of the posterior compartment.

Although we believe that a midline defect in the endopelvic fascia is primarily responsible for rectoceles, we also appreciate that the fascia must be reconstructed all the way to the perineal body and that narrowing the genital hiatus is very important and often underappreciated (FIGURE 5). Thus, perineal reconstruction is universally performed. I will emphasize again that reconstruction must be performed while also monitoring vaginal caliber. If it is too tight with the patient under anesthesia, it will be too tight when the patient recovers. Avoidance is the best option. If the patient does not desire a functional vagina (eg, an elderly patient), then narrowing is a desired goal.

Perineal reconstruction technique and tips for success

A retractor at 12 o’clock to support the apex and anterior wall can be helpful for visualization in the posterior compartment. We start with a v-shaped incision on the perineum. The width is determined by how much you want to build up the perineum and narrow the vagina (the wider the incision, the more building up of the perineal body and vaginal narrowing). A strip of epithelium is then mobilized in the midline (be careful not to excise too much). This dissection is carried all the way up the midline to just short of the tied apical suspension sutures at the posterior vaginal apex. The posterior dissection tends to be the most vascular in my experience.

Utilize cautery to obtain hemostasis along your dissection margins while protecting the underlying rectum. We have not found it necessary to dissect the posterior epithelium off the underlying fascia (that is an option at this point, however, if you feel more comfortable doing this). With an index finger in the vagina, compressing the rectum posteriorly, interrupted 1-0 polyglactin suture is placed through the epithelium and underlying fascia (avoiding the rectum) on one side, then the other, and then tied. The next sutures are placed utilizing the same technique, and the caliber of the vagina is noted with the placement of each suture (if it is too tight, then remove and replace the suture and recheck). It is important to realize you want to plicate the fascia in the midline and not perform an aggressive levatorplasty that could lead to muscle pain. Additionally, each suture should get the same purchase of tissue on each side, and the spacing of each suture should be uniform, like rungs on a ladder. Ultimately, the repair is carried down to the hymenal ring. At this point, the perineal reconstruction is performed, plicating the perineal body in the midline with deeper horizontal sutures and then closing the perineal skin with interrupted or subcuticular sutures (FIGURE 6). Completion of these repairs should orient the vagina toward the hollow of the sacrum (FIGURE 7), allowing downward forces to compress the vaginal supports posteriorly onto the pelvic floor instead of forcing it out the vaginal lumen (FIGURE 8).

Our patients generally stay in the hospital overnight, and we place a vaginal pack to provide topical pressure throughout the vagina overnight. We tell patients no lifting more than 15 lb and no intercourse for 6 weeks. While we do not tend to use hydrodissection in our repairs, it is a perfectly acceptable option.

Continue to: Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques...

Commit to knowledge of native tissue techniques

Given the recent FDA ban on the sale of transvaginal mesh for POP and the public’s negative perception of mesh (based often on misleading information in the media), it is incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to invest in learning or relearning effective native tissue techniques for the transvaginal treatment of POP. While not perfect, they offer an effective nonmesh treatment option for many of our patients.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. . Published April 16, 2019. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecological surgical mesh implants. . Published July 10, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Effective date of requirement for premarket approval for surgical mesh for transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/01/05/2015-33163/effective-date-of-requirement-for-premarket-approval-for-surgical-mesh-for-transvaginal-pelvic-organ. Published January 5, 2016. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- Lee RA. Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA; 1992.

- Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1554-1565.

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 part 1):1717-1728.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762- 1771.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. . Published April 16, 2019. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecological surgical mesh implants. . Published July 10, 2019. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Effective date of requirement for premarket approval for surgical mesh for transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/01/05/2015-33163/effective-date-of-requirement-for-premarket-approval-for-surgical-mesh-for-transvaginal-pelvic-organ. Published January 5, 2016. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- Lee RA. Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA; 1992.

- Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1554-1565.

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 part 1):1717-1728.

- Paraiso MF, Barber MD, Muir TW, et al. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1762- 1771.

Excision of abdominal wall endometriosis

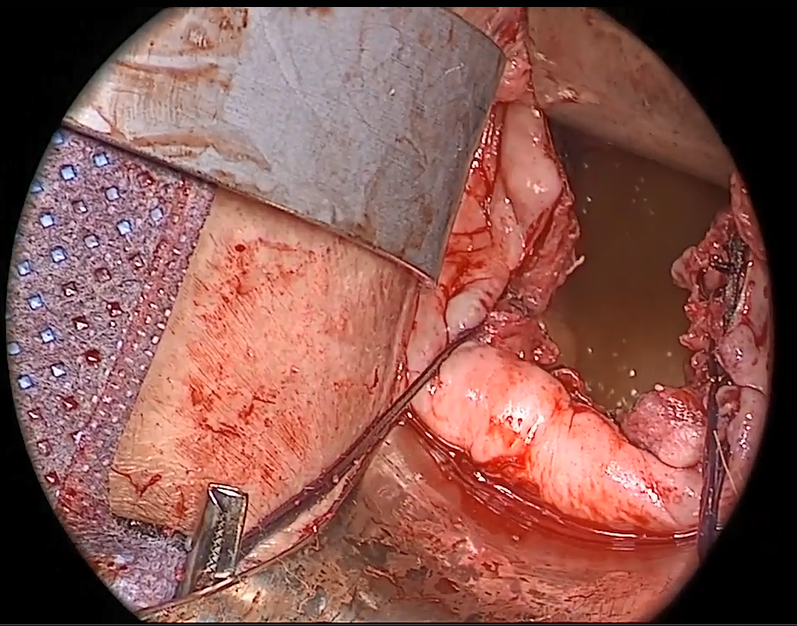

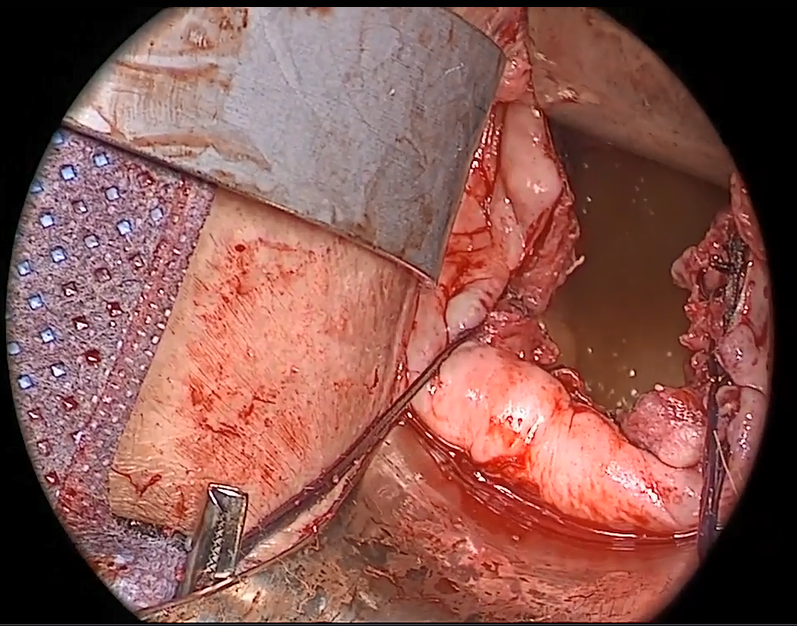

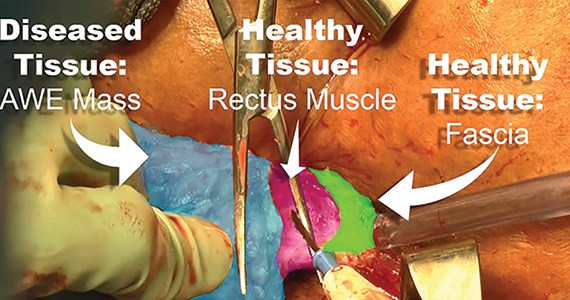

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

Minilaparotomy: Minimally invasive approach to abdominal myomectomy

A minilaparotomy is loosely defined as a laparotomy measuring between 4 cm and 6 cm. For the appropriate surgical candidate, a minilaparotomy is a useful alternative to laparotomy or laparoscopy, especially for large pathology.1 Benefits of minilaparotomy include improved pain management and postoperative recovery, as well as improved cosmetic outcome, with comparable blood loss and operative time.2,3

In this video, we illustrate the key surgical steps of a minilaparotomy for the removal of large fibroids. These steps include:

- strategic vertical skin incision

- use of a self-retaining retractor

- infiltrate myometrium with dilute vasopressin

- strategic hysterotomy

- use of tenaculum for upward traction

- 10# blade scalpels for the “lemon wedge” coring technique

- layered closure.

Minilaparotomy myomectomy can be an excellent minimally invasive alternative to a traditional “full laparotomy” for women with large fibroids.

We hope that you find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via minilaparotomy assistance for the massively enlarged adnexal mass

- Pelosi MA 2nd, Pelosi MA 3rd. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: a non-endoscopic minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. Surg Technol Int. 2004;13:157-167.

- Fanafani F, Fagotti A, Longo R. Minilaparotomy in the management of benign gynecologic disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;119:232-236.

- Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy: a minimally invasive alternative for major gynecologic abdominal surgery. Perm J. 2005;9:41-45.

A minilaparotomy is loosely defined as a laparotomy measuring between 4 cm and 6 cm. For the appropriate surgical candidate, a minilaparotomy is a useful alternative to laparotomy or laparoscopy, especially for large pathology.1 Benefits of minilaparotomy include improved pain management and postoperative recovery, as well as improved cosmetic outcome, with comparable blood loss and operative time.2,3

In this video, we illustrate the key surgical steps of a minilaparotomy for the removal of large fibroids. These steps include:

- strategic vertical skin incision

- use of a self-retaining retractor

- infiltrate myometrium with dilute vasopressin

- strategic hysterotomy

- use of tenaculum for upward traction

- 10# blade scalpels for the “lemon wedge” coring technique

- layered closure.

Minilaparotomy myomectomy can be an excellent minimally invasive alternative to a traditional “full laparotomy” for women with large fibroids.

We hope that you find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via minilaparotomy assistance for the massively enlarged adnexal mass

A minilaparotomy is loosely defined as a laparotomy measuring between 4 cm and 6 cm. For the appropriate surgical candidate, a minilaparotomy is a useful alternative to laparotomy or laparoscopy, especially for large pathology.1 Benefits of minilaparotomy include improved pain management and postoperative recovery, as well as improved cosmetic outcome, with comparable blood loss and operative time.2,3

In this video, we illustrate the key surgical steps of a minilaparotomy for the removal of large fibroids. These steps include:

- strategic vertical skin incision

- use of a self-retaining retractor

- infiltrate myometrium with dilute vasopressin

- strategic hysterotomy

- use of tenaculum for upward traction

- 10# blade scalpels for the “lemon wedge” coring technique

- layered closure.

Minilaparotomy myomectomy can be an excellent minimally invasive alternative to a traditional “full laparotomy” for women with large fibroids.

We hope that you find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via minilaparotomy assistance for the massively enlarged adnexal mass

- Pelosi MA 2nd, Pelosi MA 3rd. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: a non-endoscopic minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. Surg Technol Int. 2004;13:157-167.

- Fanafani F, Fagotti A, Longo R. Minilaparotomy in the management of benign gynecologic disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;119:232-236.

- Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy: a minimally invasive alternative for major gynecologic abdominal surgery. Perm J. 2005;9:41-45.

- Pelosi MA 2nd, Pelosi MA 3rd. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: a non-endoscopic minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. Surg Technol Int. 2004;13:157-167.

- Fanafani F, Fagotti A, Longo R. Minilaparotomy in the management of benign gynecologic disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;119:232-236.

- Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy: a minimally invasive alternative for major gynecologic abdominal surgery. Perm J. 2005;9:41-45.

A patient with severe adenomyosis requests uterine-sparing surgery

CASE

A 28-year-old patient presents for evaluation and management of her chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia. She previously tried ibuprofen with no pain relief. She also tried oral and long-acting reversible contraceptives but continued to be symptomatic. She underwent pelvic sonography, which demonstrated a large globular uterus with myometrial thickening and myometrial cysts with increased hypervascularity. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging indicated a thickened junctional zone. Feeling she had exhausted medical manegement options with no significant improvement, she desired surgical treatment, but wanted to retain her future fertility. As a newlywed, she and her husband were planning on building a family so she desired to retain her uterus for potential future pregnancy.

How would you address this patient’s disruptive symptoms, while affirming her long-term plans by choosing the proper intervention?

Adenomyosis is characterized by endometrial-like glands and stroma deep within the myometrium of the uterus and generally is classified as diffuse or focal. This common, benign gynecologic condition is known to cause enlargement of the uterus secondary to stimulation of ectopic endometrial-like cells.1-3 Although the true incidence of adenomyosis is unknown because of the difficulty of making the diagnosis, prevalence has been variously reported at 6% to 70% among reproductive-aged women.4,5

In this review, we first examine the clinical presentation and diagnosis of adenomyosis. We then discuss clinical indications for, and surgical techniques of, adenomyomectomy, including our preferred uterine-sparing approach for focal disease or when the patient wants to preserve fertility: video laparoscopic resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when indicated.

Treatment evolved in a century and a half

Adenomyosis was first described more than 150 years ago; historically, hysterectomy was the mainstay of treatment.2,6 Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis has been reported since the early 1950s.6-8 Surgical treatment initially became more widespread following the introduction of wedge resection, which allowed for partial excision of adenomyotic nodules.9

More recent developments in diagnostic technologies and capabilities have allowed for the emergence of additional uterine-sparing and minimally invasive surgical treatment options for adenomyosis.3,10 Although the use of laparoscopic approaches is limited because a high level of technical skill is required to undertake these procedures, such approaches are becoming increasingly important as more and more patients seek fertility conservation.11-13

How does adenomyosis present?

Adenomyosis symptoms commonly consist of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea, affecting approximately 40% to 60% and 15% to 30% of patients with the condition, respectively.14 These symptoms are considered nonspecific because they are also associated with other uterine abnormalities.15 Although menorrhagia is not associated with extent of disease, dysmenorrhea is associated with both the number and depth of adenomyotic foci.14

Other symptoms reported with adenomyosis include chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, as well as infertility. Note, however, that a large percentage of patients are asymptomatic.16,17

On physical examination, patients commonly exhibit a diffusely enlarged, globular uterus. This finding is secondary to uniform hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the myometrium, caused by stimulation of ectopic endometrial cells.2 A subset of patients experience significant uterine tenderness.18 Other common findings associated with adenomyosis include uterine abnormalities, such as leiomyomata, endometriosis, and endometrial polyps.

Continue to: Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential...

Two-pronged route to diagnosis and a differential

Histology

Adenomyosis is definitively diagnosed based on histologic findings of endometrial-like tissue within the myometrium. Historically, histologic analysis was performed on specimens following hysterectomy but, more recently, has utilized specimens obtained from hysteroscopic and laparoscopic myometrial biopsies.19 Importantly, although hysteroscopic and laparoscopic biopsies are taken under direct visualization, there are no pathognomonic signs for adenomyosis; a diagnosis can therefore be missed if adenomyosis is not present at biopsied sites.1 The sensitivity of random biopsy at laparoscopy has been found to be as low as 2% to as high as 56%.20

Imaging

Imaging can be helpful in clinical decision making and to guide the differential diagnosis. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is often the first mode of imaging used for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic pain. Diagnosis by TVUS is difficult because the modality is operator dependent and standard diagnostic criteria are lacking.5

The most commonly reported ultrasonographic features of adenomyosis are21,22:

- a globally enlarged uterus

- asymmetry

- myometrial thickening with heterogeneity

- poorly defined foci of hyperechoic regions, surrounded by hypoechoic areas that correspond to smooth-muscle hyperplasia

- myometrial cysts.

Doppler ultrasound examination in patients with adenomyosis reveals increased flow to the myometrium without evidence of large blood vessels.

3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasonography. Integration of 3-D ultrasonography has allowed for identification of the thicker junctional zone that suggests adenomyosis. In a systematic review of the accuracy of TVUS, investigators reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 2-dimensional ultrasonography of 83.8% and 63.9%, respectively, and a pooled sensitivity and specificity for 3-dimensional ultrasonography of 88.9% and 56.0%, respectively.22

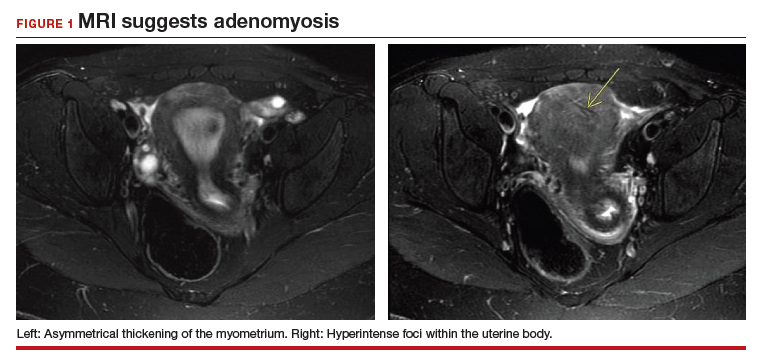

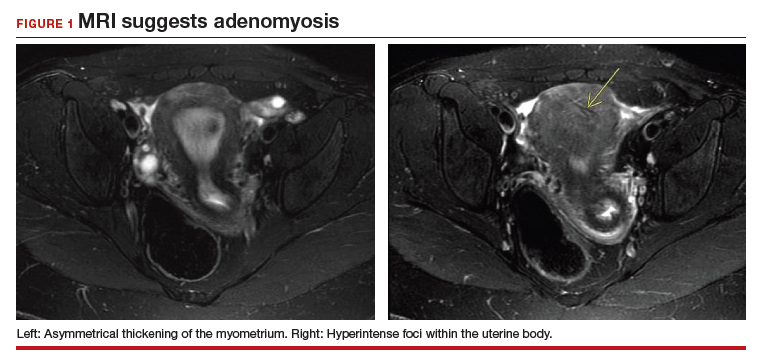

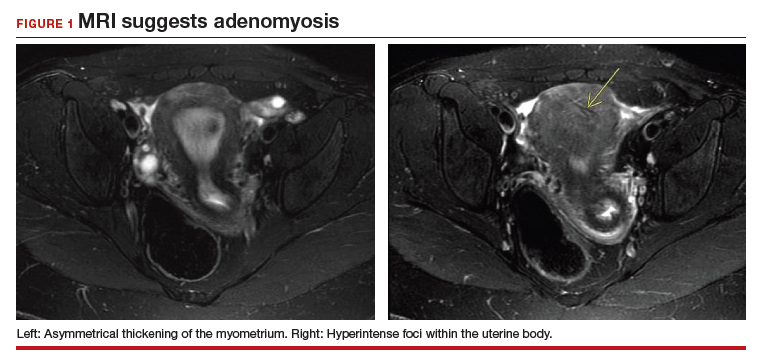

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also used in the evaluation of adenomyosis. Although MRI is considered a more accurate diagnostic modality because it is not operator dependent, expense often prohibits its use in the work-up of abnormal uterine bleeding and chronic pelvic pain.2,23

The most commonly reported MRI findings in adenomyosis include a globular or asymmetric uterus, heterogeneity of myometrial signal intensity, and thickening of the junctional zone24 (FIGURE 1). In a systematic review, researchers reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 89%, respectively, for the diagnosis of adenomyosis using MRI.25

Approaches to treatment

Medical management

No medical therapies or guidelines specific to the treatment of adenomyosis exist.9 Often, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are employed to combat cramping and pain associated with increased prostaglandin levels.26 A systematic review found that NSAIDs are significantly better at treating dysmenorrhea than placebo alone.26

Moreover, adenomyosis is an estrogen-dependent disease; consequently, many medical treatments are targeted at suppressing the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly used (off-label) for this effect include combined or progestin-only oral contraceptive pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, danazol, and aromatase inhibitors.

Use of a GnRH agonist, such as leuprolide, is limited to a short course (<6 months) because menopausal-like symptoms, such as hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and loss of bone-mineral density, can develop.16 Symptoms of adenomyosis often return upon cessation of hormonal treatment.1

Novel therapies are under investigation, including GnRH antagonists, selective progesterone-receptor modulators, and antiplatelet therapy.27

Although there are few data showing the effectiveness of medical therapy on adenomyosis-specific outcomes, medications are particularly useful in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who may prefer not to undergo surgery. Furthermore, medical therapy has considerable use in conjunction with surgical intervention; a prospective observational study showed that women who underwent GnRH agonist treatment following surgery had significantly greater improvement of their dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, compared with those who underwent surgery only.28 In addition, preoperative administration of a GnRH agonist or danazol several months prior to surgery has been shown to reduce uterine vascularity and, thus, blood loss at surgery.29,30

- Adenomyosis is common and benign, but remains underdiagnosed because of a nonspecific clinical presentation and lack of standardized diagnostic criteria.

- Adenomyosis can cause significant associated morbidity: dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.

- High clinical suspicion warrants evaluation by imaging.

- Medical management is largely aimed at ameliorating symptoms.

- A patient who does not respond to medical treatment or does not desire pregnancy has a variety of surgical options; the extent of disease and the patient’s wish for uterine preservation guide the selection of surgical technique.

- Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment but, in patients who want to avoid radical resection, techniques developed for laparotomy are available, to allow conservative resection using laparoscopy.

- Ideally, surgery is performed using a combined laparoscopy and minilaparotomy approach, after appropriate imaging.

Continue to: Surgery

Surgery

The objective of surgical management is to ameliorate symptoms in a conservative manner, by excision or cytoreduction of adenomyotic lesions, while preserving, even improving, fertility.3,11,31 The choice of procedure depends, ultimately, on the location and extent of disease, the patient’s desire for uterine preservation and fertility, and surgical skill.3

Historically, hysterectomy was used to treat adenomyosis; for patients declining fertility preservation, hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment. Since the early 1950s, several techniques for laparotomic reduction have been developed. Surgeries that achieve partial reduction include:

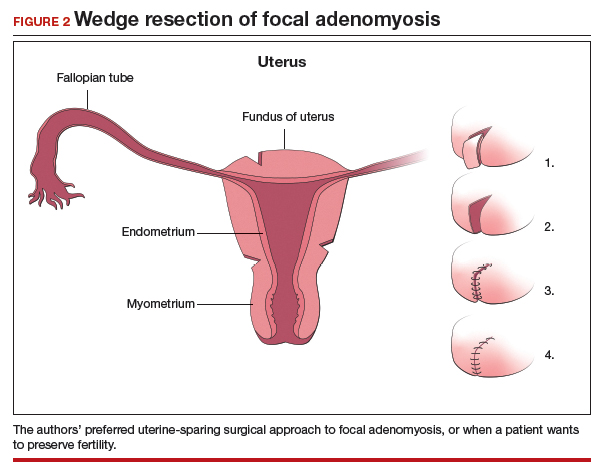

Wedge resection of the uterine wall entails removal of the seromuscular layer at the identified location of adenomyotic tissue, with subsequent repair of the remaining muscular and serosal layers surrounding the wound.3,32 Because adenomyotic tissue can remain on either side of the incision in wedge resection, clinical improvement in symptoms of dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia are modest, and recurrence is possible.7

Modified reduction surgery. Modifications of reduction surgery include slicing adenomyotic tissue using microsurgery and partial excision.33

Transverse-H incision of the uterine wall involves a transverse incision on the uterine fundus, separating serosa and myometrium, followed by removal of diseased tissue using an electrosurgical scalpel or scissors. Tensionless suturing is used to close the myometrial layers in 1 or 2 layers to establish hemostasis and close the defect; serosal flaps are closed with subserosal interrupted sutures.34 Data show that, following surgery with this technique, 21.4% to 38.7% of patients who attempt conception achieve clinical pregnancy.7

Complete, conservative resection in cases of diffuse and focal adenomyosis is possible using the triple-flap method, in which total resection is achieved by removing diseased myometrium until healthy, soft tissue—with normal texture, color, and vascularity—is reached.2 Repair with this technique reduces the risk of uterine rupture by reconstructing the uterine wall using a muscle flap prepared by metroplasty.7 In a study of 64 women who underwent triple-flap resection, a clinical pregnancy rate of 74% and a live birth rate of 52% were reported.7

Minimally invasive approaches. Although several techniques have been developed for focal excision of adenomyosis by laparotomy,7 the trend has been toward minimally invasive surgery, which reduces estimated blood loss, decreases length of stay, and reduces adhesion formation—all without a statistically significant difference in long-term clinical outcomes, compared to other techniques.35-39 Furthermore, enhanced visualization of pelvic organs provided by laparoscopy is vital in the case of adenomyosis.3,31

How our group approaches surgical management. A challenge in laparoscopic surgery of adenomyosis is extraction of an extensive amount of diseased tissue. In 1994, our group described the use of simultaneous operative laparoscopy and minilaparotomy technique as an effective and safe alternative to laparotomy in the treatment of myomectomy6; the surgical principles of that approach are applied to adenomyomectomy. The technique involves treatment of pelvic pathology with laparoscopy, removal of tissue through the minilaparotomy incision, and repair of the uterine wall defect in layers.

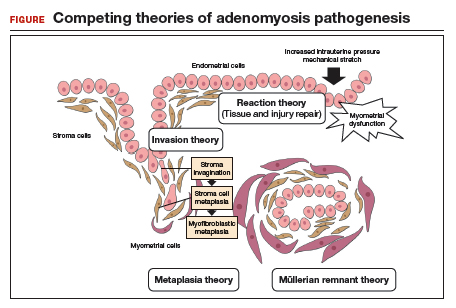

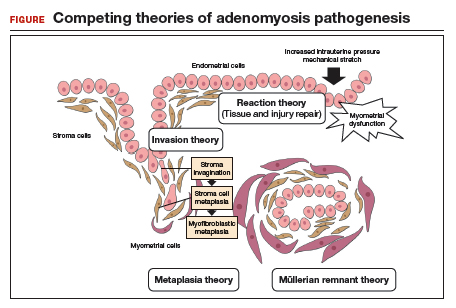

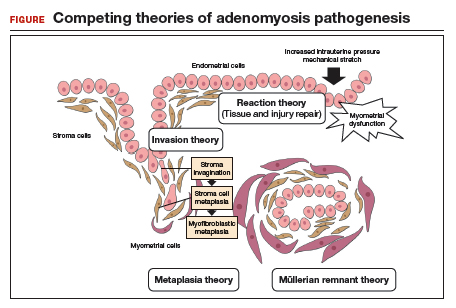

How adenomyosis originates is not fully understood. Several theories have been proposed, however (including, more prominently, the first 2 below):

Invasion theory. The endometrial basalis layer invaginates and invades the myometrium1,2 (FIGURE); the etiology of invagination remains unknown.

Reaction theory. Myometrial weakness or dysfunction, brought on by trauma from previous uterine surgery or pregnancy, could predispose uterine musculature to deep invasion.3

Metaplasia theory. Adenomyosis is a result of metaplasia of pluripotent Müllerian rests.

Müllerian remnant theory. Related to the Müllerian metaplasia theory, adenomyosis is formed de novo from 1) adult stem cells located in the endometrial basalis that is involved in the cyclic regeneration of the endometrium4-6 or 2) adult stem cells displaced from bone marrow.7,8

Once adenomyosis is established, it is thought to progress by epithelial–mesenchymal transition,2 a process by which epithelial cells become highly motile mesenchymal cells that are capable of migration and invasion, due to loss of cell–cell adhesion properties.9

References

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.2016; 23:164-185.

- García-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, et al. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril.2018;109:371-379.

- Ferenczy A. Pathophysiology of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:312-322.

- Gargett CE. Uterine stem cells: what is the evidence? Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:87-101.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1738-1750.

- Schwab KE, Chan RWS, Gargett CE. Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(Suppl 2):1124-1130.

- Sasson IE, Taylor HS. Stem cells and the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:106-115.

- Du H, Taylor HS. Stem cells and female reproduction. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:126-139.

- Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438-1449.

Continue to: In 57 women who underwent…

In 57 women who underwent this procedure, the mean operative time was 127 minutes; average estimated blood loss was 267 mL.40 Overall, laparoscopy with minilaparotomy was found to be a less technically difficult technique for laparoscopic myomectomy; allowed better closure of the uterine defect; and might have required less time to perform.3

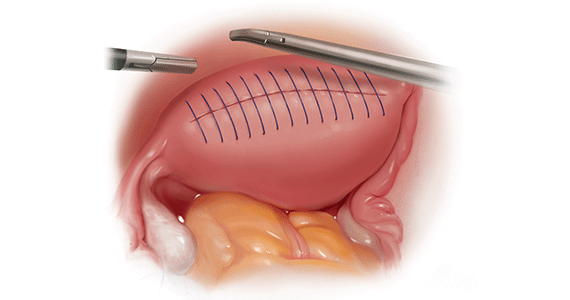

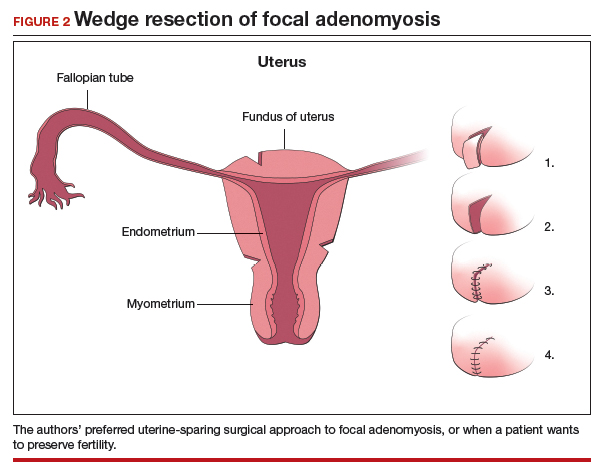

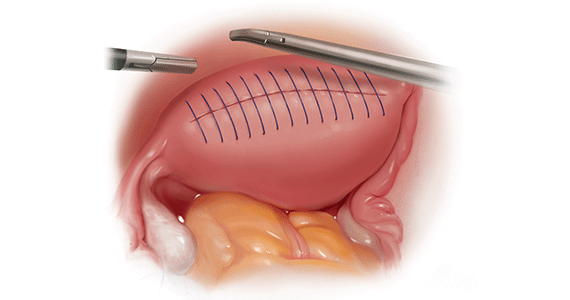

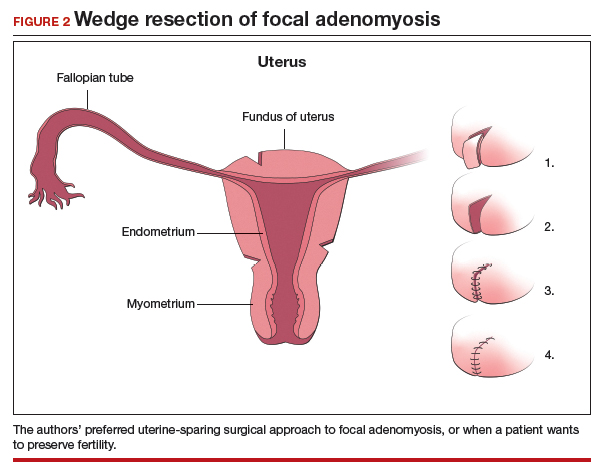

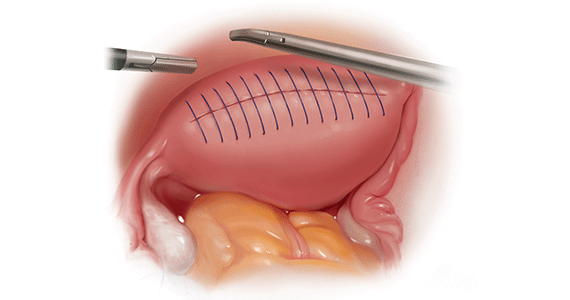

We therefore advocate video laparoscopic wedge resection with or without robotic assistance, aided by minilaparotomy when necessary for safe removal of larger adenomyomas, as the preferred uterine-sparing surgical approach for focal adenomyosis or when the patient wants to preserve fertility (FIGURE 2). We think that this technique allows focal adenomyosis to be treated by wedge resection of the diseased myometrium, with subsequent closure of the remaining myometrial defect using a barbed V-Loc (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) delayed absorbable suture in layers (FIGURE 3). Minilaparotomy can be utilized when indicated to aid removal of the resected myometrial specimen.

In our extensive experience, we have found that this technique provides significant relief of symptoms and improvements in fertility outcomes while minimizing surgical morbidity.

CASE Resolved

The patient underwent successful wedge resection of her adenomyosis by laparoscopy. She experienced nearly complete resolution of her symptoms of dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and pelvic pain. She retained good uterine integrity. Three years later, she and her husband became parents when she delivered their first child by cesarean delivery at full term. After she completed childbearing, she ultimately opted for minimally invasive hysterectomy.

The authors would like to acknowledge Mailinh Vu, MD, Fellow at Camran Nezhat Institute, for reviewing and editing this article.

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:428-437.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Azziz R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:221-235.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

- Rokitansky C. Ueber Uterusdrsen-Neubildung in Uterus- und Ovarial-Sarcomen. Gesellschaft der Ärzte in Wien. 1860;16:1-4.

- Osada H. Uterine adenomyosis and adenomyoma: the surgical approach. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:406-417.

- Van Praagh I. Conservative surgical treatment for adenomyosis uteri in young women: local excision and metroplasty. Can Med Assoc J. 1965;93:1174-1175.

- Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans MM. Introduction: Uterine adenomyosis, another enigmatic disease of our time. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:369-370.

- Nishida M, Takano K, Arai Y, et al. Conservative surgical management for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:715-719.

- Abbott JA. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-A)--Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:68-81.

- Matalliotakis IM, Katsikis IK, Panidis DK. Adenomyosis: what is the impact on fertility? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:261-264.

- Devlieger R, D'Hooghe T, Timmerman D. Uterine adenomyosis in the infertility clinic. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:139-147.

- Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A. Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:688-691.

- Weiss G, Maseelall P, Schott LL, et al. Adenomyosis a variant, not a disease? Evidence from hysterectomized menopausal women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2009;91:201-206.

- Huang F, Kung FT, Chang SY, et al. Effects of short-course buserelin therapy on adenomyosis. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:741-744.

- Benson RC, Sneeden VD. Adenomyosis: a reappraisal of symptomatology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;76:1044-1061.

- Shrestha A, Sedai LB. Understanding clinical features of adenomyosis: a case control study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14:176-179.

- Fernández C, Ricci P, Fernández E. Adenomyosis visualized during hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:555-556.

- Brosens JJ, Barker FG. The role of myometrial needle biopsies in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1347-1349.

- Van den Bosch T, Van Schoubroeck D. Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:16-24.

- Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Ribeiro J, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:257-264.

- Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433.

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, et al. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception. 2007;76:195-199.

- Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89:1374-1384.

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001751.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:398-405.

- Wang PH, Liu WM, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:876-885.

- Wood C, Maher P, Woods R. Laparoscopic surgical techniques for endometriosis and adenomyosis. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2000;6:153-168.

- Wang CJ, Yuen LT, Chang SD, et al. Use of laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery to treat infertile women with localized adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:462.e5-e8.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Sun A, Luo M, Wang W, et al. Characteristics and efficacy of modified adenomyomectomy in the treatment of uterine adenomyoma. Chin Med J. 2011;124:1322-1326.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanotti F, et al. Surgery: Fertility after conservative surgery for adenomyomas. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1708-1710.

- Fujishita A, Masuzaki H, Khan KN, et al. Modified reduction surgery for adenomyosis. A preliminary report of the transverse H incision technique. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;57:132-138.

- Operative Laparoscopy Study Group. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second-look procedures. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:700-704.

- Luciano AA, Maier DB, Koch EI, et al. A comparative study of postoperative adhesions following laser surgery by laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the rabbit model. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:220-224.