User login

A resident’s guide to lithium

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

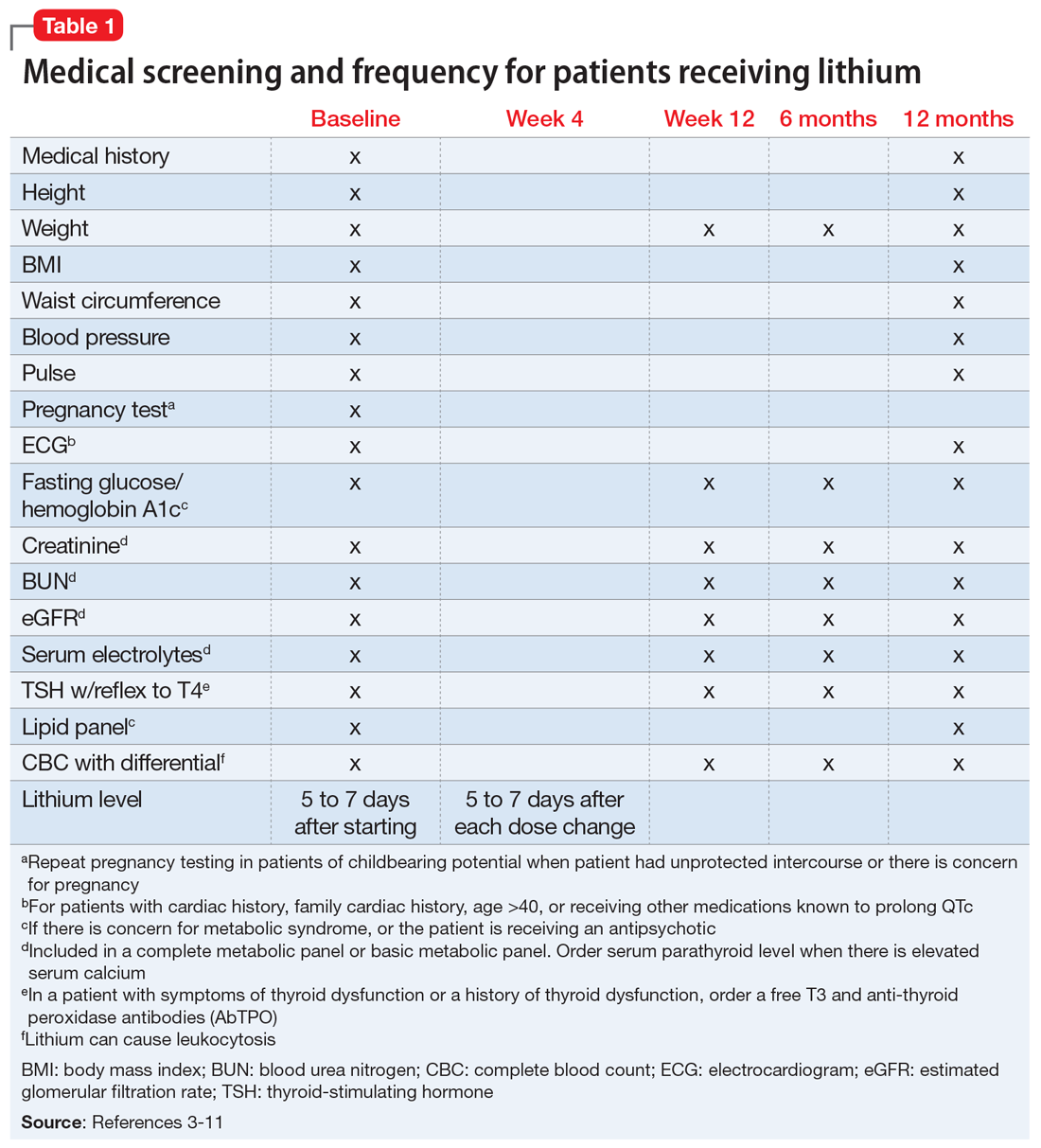

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Racial inequity in medical education and psychiatry

The ground trembled, trees shook, and voices echoed throughout the city. I looked around in awe as the dew from my breath settled on the tip of my nose, dampening my face mask. Thousands of people with varying backgrounds, together in recognition that while the arc of the moral universe is long, it cannot bend towards justice without our help. The pain, suffering, and anger of the protestors was palpable, their chants vibrating deep in my chest, all against the backdrop of the historic Los Angeles City Hall, with rows of police officers and National Guard troops on its lawn. The countless recent racially motivated attacks and murders had driven people from all walks of life to protest for an end to systemic racism. I listened to people tell stories and challenge each other to comprehend the depths of the trauma that led us to this moment, and I went home that day curious about the history of racism in medicine.

Medicine’s roots in slavery

The uncomfortable truth is that medicine in America has some of its earliest roots in slavery. In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Evans et al1 wrote “Slaves provided economic security for physicians and clinical material that permitted the expansion of medical research, improvement of medical care, and enhancement of medical training.”1

In the 1830s, medical schools would publicize abundant access to “black clinical subjects” as a recruitment method. The Savannah Medical Journal, for example, proudly stated that Savannah Medical College had a Black patient census that “provided abundant clinical opportunities for studying disease.”2 The dehumanization of Black people was pervasive, and while racism in medical education today may be less overt because the Black community is no longer sought after as “clinical material,” discrimination continues. Ebede and Papier3 found that patients of color are extremely underrepresented in images used in medical education.

How were trainees learning to recognize clinical findings in dark-skinned patients? Was this ultimately slowing the identification and treatment of diseases in such populations?

Racism in psychiatry

In a 2020 article in Psychiatric News, American Psychiatric Association (APA) president Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, provided shocking insight into the history of racism in American psychiatry.4 In 1773, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg, Virginia, became the first public freestanding psychiatric hospital in British North America.4 The hospital would only accept Black patients if their admission did not interfere with the admission of White patients. Some clinicians also believed that insanity could not occur in Black people due to their “primitive nature.”4 John Galt, physician head of the hospital from 1841 to 1862 and one of the APA’s founding fathers, believed that Black people were “immune” to insanity because they did not experience the “mental excitement” that the free population experienced daily. Further, Benjamin Rush, considered the father of American psychiatry, was adamant that black skin itself was actually a disease, called negritude, and the only treatment involved turning a Black person white.4

The blasphemy is endless. John Calhoun, former vice president of the APA in the 1840s, stated “The African is incapable of self care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is mercy to him to give this guardianship and protection from mental health.”4

How could a population that was owned, sold, beaten, chained, raped, and ultimately dehumanized not develop mental illness? Race was weaponized by the powerful in order to deny the inalienable rights of Black people. Dr. Geller summarized these atrocities perfectly: “…during [the APA’s first 40 years] … Association members did not debate segregation by race. A few members said it shall be so, and the rest were silent—silent for a very long time.”4

While I train as a resident psychiatrist, I am learning the value of cultural sensitivity and the importance of truly understanding the background of all my patients in order to effectively treat mental illness. George Floyd’s murder is the most recent death that has shed light on systemic racism and the challenges that are largely unique to the Black community and their mental health. I recognize that combating disparities in mental health requires an honest and often uncomfortable reckoning with the role that systemic racism has played in creating these health disparities. While the trauma inflicted by centuries of injustice cannot be corrected overnight, it is our responsibility to confront these biases and barriers in medicine on a daily basis as we strive to create a more equitable society.

1. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, et al. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med. 2020;353:274-276.

2. Washington HA. Medical apartheid: the dark history of medical experimentation on back Americans from colonial times to the present, 1st ed. Paw Prints; 2010.

3. Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687-690.

4. Geller J. Structural racism in American psychiatry and APA: part 1. Published June 23, 2020. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.7a18

The ground trembled, trees shook, and voices echoed throughout the city. I looked around in awe as the dew from my breath settled on the tip of my nose, dampening my face mask. Thousands of people with varying backgrounds, together in recognition that while the arc of the moral universe is long, it cannot bend towards justice without our help. The pain, suffering, and anger of the protestors was palpable, their chants vibrating deep in my chest, all against the backdrop of the historic Los Angeles City Hall, with rows of police officers and National Guard troops on its lawn. The countless recent racially motivated attacks and murders had driven people from all walks of life to protest for an end to systemic racism. I listened to people tell stories and challenge each other to comprehend the depths of the trauma that led us to this moment, and I went home that day curious about the history of racism in medicine.

Medicine’s roots in slavery

The uncomfortable truth is that medicine in America has some of its earliest roots in slavery. In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Evans et al1 wrote “Slaves provided economic security for physicians and clinical material that permitted the expansion of medical research, improvement of medical care, and enhancement of medical training.”1

In the 1830s, medical schools would publicize abundant access to “black clinical subjects” as a recruitment method. The Savannah Medical Journal, for example, proudly stated that Savannah Medical College had a Black patient census that “provided abundant clinical opportunities for studying disease.”2 The dehumanization of Black people was pervasive, and while racism in medical education today may be less overt because the Black community is no longer sought after as “clinical material,” discrimination continues. Ebede and Papier3 found that patients of color are extremely underrepresented in images used in medical education.

How were trainees learning to recognize clinical findings in dark-skinned patients? Was this ultimately slowing the identification and treatment of diseases in such populations?

Racism in psychiatry

In a 2020 article in Psychiatric News, American Psychiatric Association (APA) president Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, provided shocking insight into the history of racism in American psychiatry.4 In 1773, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg, Virginia, became the first public freestanding psychiatric hospital in British North America.4 The hospital would only accept Black patients if their admission did not interfere with the admission of White patients. Some clinicians also believed that insanity could not occur in Black people due to their “primitive nature.”4 John Galt, physician head of the hospital from 1841 to 1862 and one of the APA’s founding fathers, believed that Black people were “immune” to insanity because they did not experience the “mental excitement” that the free population experienced daily. Further, Benjamin Rush, considered the father of American psychiatry, was adamant that black skin itself was actually a disease, called negritude, and the only treatment involved turning a Black person white.4

The blasphemy is endless. John Calhoun, former vice president of the APA in the 1840s, stated “The African is incapable of self care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is mercy to him to give this guardianship and protection from mental health.”4

How could a population that was owned, sold, beaten, chained, raped, and ultimately dehumanized not develop mental illness? Race was weaponized by the powerful in order to deny the inalienable rights of Black people. Dr. Geller summarized these atrocities perfectly: “…during [the APA’s first 40 years] … Association members did not debate segregation by race. A few members said it shall be so, and the rest were silent—silent for a very long time.”4

While I train as a resident psychiatrist, I am learning the value of cultural sensitivity and the importance of truly understanding the background of all my patients in order to effectively treat mental illness. George Floyd’s murder is the most recent death that has shed light on systemic racism and the challenges that are largely unique to the Black community and their mental health. I recognize that combating disparities in mental health requires an honest and often uncomfortable reckoning with the role that systemic racism has played in creating these health disparities. While the trauma inflicted by centuries of injustice cannot be corrected overnight, it is our responsibility to confront these biases and barriers in medicine on a daily basis as we strive to create a more equitable society.

The ground trembled, trees shook, and voices echoed throughout the city. I looked around in awe as the dew from my breath settled on the tip of my nose, dampening my face mask. Thousands of people with varying backgrounds, together in recognition that while the arc of the moral universe is long, it cannot bend towards justice without our help. The pain, suffering, and anger of the protestors was palpable, their chants vibrating deep in my chest, all against the backdrop of the historic Los Angeles City Hall, with rows of police officers and National Guard troops on its lawn. The countless recent racially motivated attacks and murders had driven people from all walks of life to protest for an end to systemic racism. I listened to people tell stories and challenge each other to comprehend the depths of the trauma that led us to this moment, and I went home that day curious about the history of racism in medicine.

Medicine’s roots in slavery

The uncomfortable truth is that medicine in America has some of its earliest roots in slavery. In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Evans et al1 wrote “Slaves provided economic security for physicians and clinical material that permitted the expansion of medical research, improvement of medical care, and enhancement of medical training.”1

In the 1830s, medical schools would publicize abundant access to “black clinical subjects” as a recruitment method. The Savannah Medical Journal, for example, proudly stated that Savannah Medical College had a Black patient census that “provided abundant clinical opportunities for studying disease.”2 The dehumanization of Black people was pervasive, and while racism in medical education today may be less overt because the Black community is no longer sought after as “clinical material,” discrimination continues. Ebede and Papier3 found that patients of color are extremely underrepresented in images used in medical education.

How were trainees learning to recognize clinical findings in dark-skinned patients? Was this ultimately slowing the identification and treatment of diseases in such populations?

Racism in psychiatry

In a 2020 article in Psychiatric News, American Psychiatric Association (APA) president Jeffrey Geller, MD, MPH, provided shocking insight into the history of racism in American psychiatry.4 In 1773, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg, Virginia, became the first public freestanding psychiatric hospital in British North America.4 The hospital would only accept Black patients if their admission did not interfere with the admission of White patients. Some clinicians also believed that insanity could not occur in Black people due to their “primitive nature.”4 John Galt, physician head of the hospital from 1841 to 1862 and one of the APA’s founding fathers, believed that Black people were “immune” to insanity because they did not experience the “mental excitement” that the free population experienced daily. Further, Benjamin Rush, considered the father of American psychiatry, was adamant that black skin itself was actually a disease, called negritude, and the only treatment involved turning a Black person white.4

The blasphemy is endless. John Calhoun, former vice president of the APA in the 1840s, stated “The African is incapable of self care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is mercy to him to give this guardianship and protection from mental health.”4

How could a population that was owned, sold, beaten, chained, raped, and ultimately dehumanized not develop mental illness? Race was weaponized by the powerful in order to deny the inalienable rights of Black people. Dr. Geller summarized these atrocities perfectly: “…during [the APA’s first 40 years] … Association members did not debate segregation by race. A few members said it shall be so, and the rest were silent—silent for a very long time.”4

While I train as a resident psychiatrist, I am learning the value of cultural sensitivity and the importance of truly understanding the background of all my patients in order to effectively treat mental illness. George Floyd’s murder is the most recent death that has shed light on systemic racism and the challenges that are largely unique to the Black community and their mental health. I recognize that combating disparities in mental health requires an honest and often uncomfortable reckoning with the role that systemic racism has played in creating these health disparities. While the trauma inflicted by centuries of injustice cannot be corrected overnight, it is our responsibility to confront these biases and barriers in medicine on a daily basis as we strive to create a more equitable society.

1. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, et al. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med. 2020;353:274-276.

2. Washington HA. Medical apartheid: the dark history of medical experimentation on back Americans from colonial times to the present, 1st ed. Paw Prints; 2010.

3. Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687-690.

4. Geller J. Structural racism in American psychiatry and APA: part 1. Published June 23, 2020. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.7a18

1. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, et al. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med. 2020;353:274-276.

2. Washington HA. Medical apartheid: the dark history of medical experimentation on back Americans from colonial times to the present, 1st ed. Paw Prints; 2010.

3. Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687-690.

4. Geller J. Structural racism in American psychiatry and APA: part 1. Published June 23, 2020. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.7a18

Virtual supervision during the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has fundamentally changed our way of life. It has affected everything from how we go to the grocery store, attend school, worship, and spend time with our loved ones. As vaccinations are becoming available, there’s hope for a time when we can all enjoy a mask-free life again. Despite this, many of us are beginning to sense that the precautions and technology employed in response to COVID-19, and some of the lessons learned as a result, are likely to stay in place long after the virus has been controlled.

Working remotely through audio and visual synchronous communication is now becoming the norm throughout the American workplace and educational system. Hospitals and graduate medical education programs are not exempt from this trend. For at least the foreseeable future, gone are the days of “unsocially distanced” bedside rounds in which 5 to 10 residents and medical students gather around with their attending as a case is presented in front of an agreeable patient.

My experience with ‘virtual’ supervision

Telemedicine has played a key role in the practice of health care during this pandemic, but little has been written about “telesupervision” of residents in the hospital setting. An unprecedented virtual approach to supervising emergency medicine residents was trialed at the University of Alabama a few months prior to my experience with it. This was found to be quite effective and well-received by all involved parties.1

I am a PGY-2 psychiatry resident at ChristianaCare, a large multisite hospital system with more than 1,200 beds that serves the health care needs of Delaware and the surrounding areas. I recently had a novel educational experience working on a busy addiction medicine consult service. On the first day of this rotation, I met with my attending, Dr. Terry Horton, to discuss how the month would proceed. Together we developed a strategy for him to supervise me virtually.

Our arrangement was efficient and simple: I began each day by donning my surgical mask and protective eyewear and reviewing patients that had been placed on the consult list. Dr. Horton and I would have a conversation via telephone early in the morning to discuss the tasks that needed to be completed for the day. I would see and evaluate patients in the standard face-to-face way. After developing a treatment strategy, I contacted Dr. Horton on the phone, presented the patient, shared my plan, and gained information from his experienced perspective.

Then we saw the patient “together.” We used an iPad and Microsoft Teams video conferencing software. The information shared was protected using Microsoft Teams accounts, which were secured with profiles created by our institutional accounts. The iPad was placed on a rolling tripod, and the patient was able to converse with Dr. Horton as though he was physically in the room. I was there to facilitate the call, address any technical issues, and conduct any aspects of a physical exam that could only be done in person. After discussing any other changes to the treatment plan, I placed all medication orders, shared relevant details with nursing staff and other clinicians, wrote my progress note, and rolled my “attending on a stick” over to the next patient. Meanwhile, Dr. Horton was free to respond to pages or any other issues while I worked.

This description of my workflow is not very different from life before the virus. Based on informal feedback gathered from patients, the experience was overall positive. A physician is present; patients feel well cared for, and they look forward to visits and a virtual presence. This virtual approach not only spared unnecessary physical contact, reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure, it also promoted efficiency.

Continue to: Fortunately, our hospital...

Fortunately, our hospital is surrounded by a solid telecommunications infrastructure. This experience would be limited in more remote areas of the country. At times, sound quality was an issue, which can be especially problematic for certain patients.

Certain psychosocial implications of the pandemic, including (but not limited to)social isolation and financial hardship, are often associated with increased substance use, and early data support the hypothesis that substance use has increased during this period.2 Delaware seems to be included in the national trend. As such, our already-busy service is being stretched even further. Dr. Horton receives calls and is providing critical recommendations continuously throughout the day for multiple hospitals as well as for his outpatient practice. He used to spend a great deal of time traveling between different sites. With increasing need for his expertise, this model became increasingly difficult to practice. Our new model of attending supervision is welcomed in some settings because the attending can virtually be in multiple places at the same time.

For me, this experience has been positive. For a physician in training, virtual rounding can provide a critical balance of autonomy and support. I felt free on the rotation to make my own decisions, but I also did not feel like I was left to care for complicated cases on my own. Furthermore, my education did not suffer. In actuality, the experience enabled me to excel in my training. An attending physician was there for the important steps of plan formulation, but solo problem-solving opportunities were more readily available without his physical presence.

Aside from the medical lessons learned, I believe the participation has given me a glimpse of the future of medical training, health care delivery, and life in the increasingly digital post−COVID-19 world.

Hopefully, my experience will be helpful for other hospital systems as they continue to provide high-quality care to patients and education/training to their resident physicians in the face of the pandemic and the changing landscape of health care.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Mustafa Mufti, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Program Director; Rachel Bronsther, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Associate Program Director; and Terry Horton, MD, ChristianaCare Addiction Medicine, for their assistance with this article.

1. Schrading WA, Pigott D, Thompson L. Virtual remote attending supervision in an academic emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):266-269.

2. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has fundamentally changed our way of life. It has affected everything from how we go to the grocery store, attend school, worship, and spend time with our loved ones. As vaccinations are becoming available, there’s hope for a time when we can all enjoy a mask-free life again. Despite this, many of us are beginning to sense that the precautions and technology employed in response to COVID-19, and some of the lessons learned as a result, are likely to stay in place long after the virus has been controlled.

Working remotely through audio and visual synchronous communication is now becoming the norm throughout the American workplace and educational system. Hospitals and graduate medical education programs are not exempt from this trend. For at least the foreseeable future, gone are the days of “unsocially distanced” bedside rounds in which 5 to 10 residents and medical students gather around with their attending as a case is presented in front of an agreeable patient.

My experience with ‘virtual’ supervision

Telemedicine has played a key role in the practice of health care during this pandemic, but little has been written about “telesupervision” of residents in the hospital setting. An unprecedented virtual approach to supervising emergency medicine residents was trialed at the University of Alabama a few months prior to my experience with it. This was found to be quite effective and well-received by all involved parties.1

I am a PGY-2 psychiatry resident at ChristianaCare, a large multisite hospital system with more than 1,200 beds that serves the health care needs of Delaware and the surrounding areas. I recently had a novel educational experience working on a busy addiction medicine consult service. On the first day of this rotation, I met with my attending, Dr. Terry Horton, to discuss how the month would proceed. Together we developed a strategy for him to supervise me virtually.

Our arrangement was efficient and simple: I began each day by donning my surgical mask and protective eyewear and reviewing patients that had been placed on the consult list. Dr. Horton and I would have a conversation via telephone early in the morning to discuss the tasks that needed to be completed for the day. I would see and evaluate patients in the standard face-to-face way. After developing a treatment strategy, I contacted Dr. Horton on the phone, presented the patient, shared my plan, and gained information from his experienced perspective.

Then we saw the patient “together.” We used an iPad and Microsoft Teams video conferencing software. The information shared was protected using Microsoft Teams accounts, which were secured with profiles created by our institutional accounts. The iPad was placed on a rolling tripod, and the patient was able to converse with Dr. Horton as though he was physically in the room. I was there to facilitate the call, address any technical issues, and conduct any aspects of a physical exam that could only be done in person. After discussing any other changes to the treatment plan, I placed all medication orders, shared relevant details with nursing staff and other clinicians, wrote my progress note, and rolled my “attending on a stick” over to the next patient. Meanwhile, Dr. Horton was free to respond to pages or any other issues while I worked.

This description of my workflow is not very different from life before the virus. Based on informal feedback gathered from patients, the experience was overall positive. A physician is present; patients feel well cared for, and they look forward to visits and a virtual presence. This virtual approach not only spared unnecessary physical contact, reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure, it also promoted efficiency.

Continue to: Fortunately, our hospital...

Fortunately, our hospital is surrounded by a solid telecommunications infrastructure. This experience would be limited in more remote areas of the country. At times, sound quality was an issue, which can be especially problematic for certain patients.

Certain psychosocial implications of the pandemic, including (but not limited to)social isolation and financial hardship, are often associated with increased substance use, and early data support the hypothesis that substance use has increased during this period.2 Delaware seems to be included in the national trend. As such, our already-busy service is being stretched even further. Dr. Horton receives calls and is providing critical recommendations continuously throughout the day for multiple hospitals as well as for his outpatient practice. He used to spend a great deal of time traveling between different sites. With increasing need for his expertise, this model became increasingly difficult to practice. Our new model of attending supervision is welcomed in some settings because the attending can virtually be in multiple places at the same time.

For me, this experience has been positive. For a physician in training, virtual rounding can provide a critical balance of autonomy and support. I felt free on the rotation to make my own decisions, but I also did not feel like I was left to care for complicated cases on my own. Furthermore, my education did not suffer. In actuality, the experience enabled me to excel in my training. An attending physician was there for the important steps of plan formulation, but solo problem-solving opportunities were more readily available without his physical presence.

Aside from the medical lessons learned, I believe the participation has given me a glimpse of the future of medical training, health care delivery, and life in the increasingly digital post−COVID-19 world.

Hopefully, my experience will be helpful for other hospital systems as they continue to provide high-quality care to patients and education/training to their resident physicians in the face of the pandemic and the changing landscape of health care.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Mustafa Mufti, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Program Director; Rachel Bronsther, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Associate Program Director; and Terry Horton, MD, ChristianaCare Addiction Medicine, for their assistance with this article.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has fundamentally changed our way of life. It has affected everything from how we go to the grocery store, attend school, worship, and spend time with our loved ones. As vaccinations are becoming available, there’s hope for a time when we can all enjoy a mask-free life again. Despite this, many of us are beginning to sense that the precautions and technology employed in response to COVID-19, and some of the lessons learned as a result, are likely to stay in place long after the virus has been controlled.

Working remotely through audio and visual synchronous communication is now becoming the norm throughout the American workplace and educational system. Hospitals and graduate medical education programs are not exempt from this trend. For at least the foreseeable future, gone are the days of “unsocially distanced” bedside rounds in which 5 to 10 residents and medical students gather around with their attending as a case is presented in front of an agreeable patient.

My experience with ‘virtual’ supervision

Telemedicine has played a key role in the practice of health care during this pandemic, but little has been written about “telesupervision” of residents in the hospital setting. An unprecedented virtual approach to supervising emergency medicine residents was trialed at the University of Alabama a few months prior to my experience with it. This was found to be quite effective and well-received by all involved parties.1

I am a PGY-2 psychiatry resident at ChristianaCare, a large multisite hospital system with more than 1,200 beds that serves the health care needs of Delaware and the surrounding areas. I recently had a novel educational experience working on a busy addiction medicine consult service. On the first day of this rotation, I met with my attending, Dr. Terry Horton, to discuss how the month would proceed. Together we developed a strategy for him to supervise me virtually.

Our arrangement was efficient and simple: I began each day by donning my surgical mask and protective eyewear and reviewing patients that had been placed on the consult list. Dr. Horton and I would have a conversation via telephone early in the morning to discuss the tasks that needed to be completed for the day. I would see and evaluate patients in the standard face-to-face way. After developing a treatment strategy, I contacted Dr. Horton on the phone, presented the patient, shared my plan, and gained information from his experienced perspective.

Then we saw the patient “together.” We used an iPad and Microsoft Teams video conferencing software. The information shared was protected using Microsoft Teams accounts, which were secured with profiles created by our institutional accounts. The iPad was placed on a rolling tripod, and the patient was able to converse with Dr. Horton as though he was physically in the room. I was there to facilitate the call, address any technical issues, and conduct any aspects of a physical exam that could only be done in person. After discussing any other changes to the treatment plan, I placed all medication orders, shared relevant details with nursing staff and other clinicians, wrote my progress note, and rolled my “attending on a stick” over to the next patient. Meanwhile, Dr. Horton was free to respond to pages or any other issues while I worked.

This description of my workflow is not very different from life before the virus. Based on informal feedback gathered from patients, the experience was overall positive. A physician is present; patients feel well cared for, and they look forward to visits and a virtual presence. This virtual approach not only spared unnecessary physical contact, reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure, it also promoted efficiency.

Continue to: Fortunately, our hospital...

Fortunately, our hospital is surrounded by a solid telecommunications infrastructure. This experience would be limited in more remote areas of the country. At times, sound quality was an issue, which can be especially problematic for certain patients.

Certain psychosocial implications of the pandemic, including (but not limited to)social isolation and financial hardship, are often associated with increased substance use, and early data support the hypothesis that substance use has increased during this period.2 Delaware seems to be included in the national trend. As such, our already-busy service is being stretched even further. Dr. Horton receives calls and is providing critical recommendations continuously throughout the day for multiple hospitals as well as for his outpatient practice. He used to spend a great deal of time traveling between different sites. With increasing need for his expertise, this model became increasingly difficult to practice. Our new model of attending supervision is welcomed in some settings because the attending can virtually be in multiple places at the same time.

For me, this experience has been positive. For a physician in training, virtual rounding can provide a critical balance of autonomy and support. I felt free on the rotation to make my own decisions, but I also did not feel like I was left to care for complicated cases on my own. Furthermore, my education did not suffer. In actuality, the experience enabled me to excel in my training. An attending physician was there for the important steps of plan formulation, but solo problem-solving opportunities were more readily available without his physical presence.

Aside from the medical lessons learned, I believe the participation has given me a glimpse of the future of medical training, health care delivery, and life in the increasingly digital post−COVID-19 world.

Hopefully, my experience will be helpful for other hospital systems as they continue to provide high-quality care to patients and education/training to their resident physicians in the face of the pandemic and the changing landscape of health care.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Mustafa Mufti, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Program Director; Rachel Bronsther, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Associate Program Director; and Terry Horton, MD, ChristianaCare Addiction Medicine, for their assistance with this article.

1. Schrading WA, Pigott D, Thompson L. Virtual remote attending supervision in an academic emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):266-269.

2. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

1. Schrading WA, Pigott D, Thompson L. Virtual remote attending supervision in an academic emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):266-269.

2. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

Finding fulfillment in a psychiatry clinical teaching role

On my third day as a PGY-4 junior attending on the inpatient psychiatric ward, 2 new PGY-1 residents, 2 medical students, and I stood in the wee hours of the morning, preparing to meet with our attending to begin rounds. I took the opportunity to discuss potential antipsychotic selection for one of our patients. I questioned the students to gauge their level of knowledge on antipsychotics in general, and did some “thinking out loud” about what our possible options could be. We discussed which antipsychotics are considered “weight-neutral” and which ones require caloric intake for adequate absorption. We discussed what other laboratory tests we should consider upon initiating the hypothetical medication. While discussing these things, I was suddenly taken aback to see that every member of my team was diligently taking notes and hanging on my every word!

Lessons from my teaching experiences

Taking on the role of junior attending has made me reflect on a few things about the transition that I will undergo at the end of this year, from resident to attending. First, teaching makes me keen to really sharpen my own knowledge, so that I can provide accurate information with confidence and ease. Making valid clinical decisions is a basic attending skill, but eloquently explaining clinical decisions to trainees with varying levels of background knowledge is a unique teaching attending necessity.