User login

Career Choices: Navy Psychiatry

In this Career Choices, Siddhi Bhivandkar, MD, spoke with Captain Paulette T. Cazares, MD, MPH. Dr. Cazares is Director for Mental Health at U.S. Navy Medicine Readiness and Training Command Okinawa, Japan. She also is Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and serves as Secretary of the American Medical Women’s Association, Schaumburg, Illinois.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What made you choose the Navy psychiatry track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Cazares: I had considered a career in the Navy early on in my education, and when I was ready to apply to medical school, I saw Uniformed Services University (USU) as one of my top choices. I wasn’t 100% sure, but after a tour and my interview, I was sold on serving those who serve.

During my clinical rotations at USU, I had great experiences in inpatient and emergency psychiatry. I became fascinated with understanding all I could about brain circuitry and chemistry, and how that interacts with the environment to create or protect individuals from disease. Once I talked with some mentors, it became clear to me that I would love a career in psychiatry, and that remains true today.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the pros and cons of working in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: As a Navy psychiatrist, I have found great reward in caring for our nation’s volunteer force. I have had wonderful colleagues with whom I have deployed, and with whom I have served in both small military hospitals and large military training and academic centers. I have been able to work in research in military mental health, and feel I have specifically advanced the field of women’s mental health in the Navy.

I had 4 children while I have been on active duty, and had paid maternity leave for all of them, as well as practices that protected my choice to breastfeed and pump, even after returning to work. I have moved to areas of the country I didn’t expect to with the Navy, and my husband’s career took unexpected turns as a result. While this can be seen as a challenge, it can also be a surprisingly rewarding experience, seeing areas of our nation and world that I otherwise would not have seen. I have deployed and been away from family. While that was a challenge, my family came through it very strong, and I found myself a more humble human and a better clinician as a result of that time.

Dr. Bhivandkar: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a Navy psychiatry program?

Dr. Cazares: In considering a Navy training program, one should consider that in the military, our patient population is generally young and healthy, yet also exposed to unique occupational stressors. This means that we generally see routine mental health diagnoses, and some early-break severe cases. We do not typically follow long-term patients with chronic mental illness, because those patients tend to be medically retired from active duty service.

Continue to: We see many unique populations...

We see many unique populations that have specific health care needs, including service members who work on submarines, who are pilots or military police members, and those who handle and manage weapons. We get to learn the unique balance between serving our patients, and the units they work for and in. We see the impact of occupational stress on individuals, and are part of the multidisciplinary team that helps to build resilience in our young service members.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the career options and work settings for Navy psychiatrists?

Dr. Cazares: My peers and I have worked across both operational and multiple hospital settings, with both the US Marine Corps, as well as the US Navy. Psychiatrists can apply for fellowship, as the Navy regularly trains child and adolescent psychiatrists, as well as those who want to specialize in addiction psychiatry.

We can work in large Navy medical centers on faculty, in community-style Navy hospitals both in the United States and overseas, as well as on ships, with the Marines, or in headquarters jobs, advising on policy and the future of the military health system.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the challenges of working in this field?

Dr. Cazares: Health care and the military are both demanding career fields. Like many areas of medicine, work-life harmony is an important part of a career in Navy psychiatry. I work hard to balance my own needs, and model this for those I lead.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: Consider joining a team that offers incredible purpose. I have served wonderful patients and had incredibly impressive colleagues, and I am grateful for the choice I made to take an oath and wear the uniform.

In this Career Choices, Siddhi Bhivandkar, MD, spoke with Captain Paulette T. Cazares, MD, MPH. Dr. Cazares is Director for Mental Health at U.S. Navy Medicine Readiness and Training Command Okinawa, Japan. She also is Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and serves as Secretary of the American Medical Women’s Association, Schaumburg, Illinois.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What made you choose the Navy psychiatry track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Cazares: I had considered a career in the Navy early on in my education, and when I was ready to apply to medical school, I saw Uniformed Services University (USU) as one of my top choices. I wasn’t 100% sure, but after a tour and my interview, I was sold on serving those who serve.

During my clinical rotations at USU, I had great experiences in inpatient and emergency psychiatry. I became fascinated with understanding all I could about brain circuitry and chemistry, and how that interacts with the environment to create or protect individuals from disease. Once I talked with some mentors, it became clear to me that I would love a career in psychiatry, and that remains true today.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the pros and cons of working in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: As a Navy psychiatrist, I have found great reward in caring for our nation’s volunteer force. I have had wonderful colleagues with whom I have deployed, and with whom I have served in both small military hospitals and large military training and academic centers. I have been able to work in research in military mental health, and feel I have specifically advanced the field of women’s mental health in the Navy.

I had 4 children while I have been on active duty, and had paid maternity leave for all of them, as well as practices that protected my choice to breastfeed and pump, even after returning to work. I have moved to areas of the country I didn’t expect to with the Navy, and my husband’s career took unexpected turns as a result. While this can be seen as a challenge, it can also be a surprisingly rewarding experience, seeing areas of our nation and world that I otherwise would not have seen. I have deployed and been away from family. While that was a challenge, my family came through it very strong, and I found myself a more humble human and a better clinician as a result of that time.

Dr. Bhivandkar: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a Navy psychiatry program?

Dr. Cazares: In considering a Navy training program, one should consider that in the military, our patient population is generally young and healthy, yet also exposed to unique occupational stressors. This means that we generally see routine mental health diagnoses, and some early-break severe cases. We do not typically follow long-term patients with chronic mental illness, because those patients tend to be medically retired from active duty service.

Continue to: We see many unique populations...

We see many unique populations that have specific health care needs, including service members who work on submarines, who are pilots or military police members, and those who handle and manage weapons. We get to learn the unique balance between serving our patients, and the units they work for and in. We see the impact of occupational stress on individuals, and are part of the multidisciplinary team that helps to build resilience in our young service members.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the career options and work settings for Navy psychiatrists?

Dr. Cazares: My peers and I have worked across both operational and multiple hospital settings, with both the US Marine Corps, as well as the US Navy. Psychiatrists can apply for fellowship, as the Navy regularly trains child and adolescent psychiatrists, as well as those who want to specialize in addiction psychiatry.

We can work in large Navy medical centers on faculty, in community-style Navy hospitals both in the United States and overseas, as well as on ships, with the Marines, or in headquarters jobs, advising on policy and the future of the military health system.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the challenges of working in this field?

Dr. Cazares: Health care and the military are both demanding career fields. Like many areas of medicine, work-life harmony is an important part of a career in Navy psychiatry. I work hard to balance my own needs, and model this for those I lead.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: Consider joining a team that offers incredible purpose. I have served wonderful patients and had incredibly impressive colleagues, and I am grateful for the choice I made to take an oath and wear the uniform.

In this Career Choices, Siddhi Bhivandkar, MD, spoke with Captain Paulette T. Cazares, MD, MPH. Dr. Cazares is Director for Mental Health at U.S. Navy Medicine Readiness and Training Command Okinawa, Japan. She also is Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and serves as Secretary of the American Medical Women’s Association, Schaumburg, Illinois.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What made you choose the Navy psychiatry track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Cazares: I had considered a career in the Navy early on in my education, and when I was ready to apply to medical school, I saw Uniformed Services University (USU) as one of my top choices. I wasn’t 100% sure, but after a tour and my interview, I was sold on serving those who serve.

During my clinical rotations at USU, I had great experiences in inpatient and emergency psychiatry. I became fascinated with understanding all I could about brain circuitry and chemistry, and how that interacts with the environment to create or protect individuals from disease. Once I talked with some mentors, it became clear to me that I would love a career in psychiatry, and that remains true today.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the pros and cons of working in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: As a Navy psychiatrist, I have found great reward in caring for our nation’s volunteer force. I have had wonderful colleagues with whom I have deployed, and with whom I have served in both small military hospitals and large military training and academic centers. I have been able to work in research in military mental health, and feel I have specifically advanced the field of women’s mental health in the Navy.

I had 4 children while I have been on active duty, and had paid maternity leave for all of them, as well as practices that protected my choice to breastfeed and pump, even after returning to work. I have moved to areas of the country I didn’t expect to with the Navy, and my husband’s career took unexpected turns as a result. While this can be seen as a challenge, it can also be a surprisingly rewarding experience, seeing areas of our nation and world that I otherwise would not have seen. I have deployed and been away from family. While that was a challenge, my family came through it very strong, and I found myself a more humble human and a better clinician as a result of that time.

Dr. Bhivandkar: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a Navy psychiatry program?

Dr. Cazares: In considering a Navy training program, one should consider that in the military, our patient population is generally young and healthy, yet also exposed to unique occupational stressors. This means that we generally see routine mental health diagnoses, and some early-break severe cases. We do not typically follow long-term patients with chronic mental illness, because those patients tend to be medically retired from active duty service.

Continue to: We see many unique populations...

We see many unique populations that have specific health care needs, including service members who work on submarines, who are pilots or military police members, and those who handle and manage weapons. We get to learn the unique balance between serving our patients, and the units they work for and in. We see the impact of occupational stress on individuals, and are part of the multidisciplinary team that helps to build resilience in our young service members.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the career options and work settings for Navy psychiatrists?

Dr. Cazares: My peers and I have worked across both operational and multiple hospital settings, with both the US Marine Corps, as well as the US Navy. Psychiatrists can apply for fellowship, as the Navy regularly trains child and adolescent psychiatrists, as well as those who want to specialize in addiction psychiatry.

We can work in large Navy medical centers on faculty, in community-style Navy hospitals both in the United States and overseas, as well as on ships, with the Marines, or in headquarters jobs, advising on policy and the future of the military health system.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What are some of the challenges of working in this field?

Dr. Cazares: Health care and the military are both demanding career fields. Like many areas of medicine, work-life harmony is an important part of a career in Navy psychiatry. I work hard to balance my own needs, and model this for those I lead.

Dr. Bhivandkar: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in Navy psychiatry?

Dr. Cazares: Consider joining a team that offers incredible purpose. I have served wonderful patients and had incredibly impressive colleagues, and I am grateful for the choice I made to take an oath and wear the uniform.

Constipation: A potentially serious adverse effect of clozapine that’s often overlooked

Clozapine is the most effective second-generation antipsychotic for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. It can reduce delusions and hallucinations in patients who are unresponsive to other antipsychotic medications. Further, clozapine is the only agent known to reduce suicidal urges.1

Unfortunately, clozapine is associated with numerous adverse effects, most notably agranulocytosis, a rare but potentially fatal adverse effect that occurs in approximately 1% to 2% of patients during the first year of treatment.2 Other adverse effects associated with clozapine are weight gain, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, sialorrhea, constipation, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, myocarditis, and seizures. Among these adverse effects, constipation, which can progress to life-threatening gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility and ileus, is often overlooked. Up to 60% of patients who are administered clozapine experience constipation.3 A recent review found that potentially life-threatening clozapine-induced ileus occurred in approximately 3 per 1,000 patients, and 28 deaths have been documented.4

In this case report, I describe a patient who received clozapine and experienced constipation that led to an intestinal obstruction. I discuss the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment approaches to prevent severe constipation in patients who are prescribed clozapine.

CASE REPORT

Mr. L, age 24, has schizophrenia, depression, mild intellectual disability, and congenital human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He has had multiple unsuccessful antipsychotic trials but is compliant with highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV. After experiencing worsening aggressive behavior for a third time, Mr. L was involuntarily committed to our Crises Response Center.

Mr. L was admitted to the acute inpatient psychiatry unit. He reported having auditory hallucinations, which included whispering sounds with intermittent music, mostly at night. He also reported decreased sleep, poor appetite, and low energy, but denied feelings of depression or mania.

During the mental status examination, Mr. L was calm and cooperative, but easily distracted. He said he smoked cigarettes but denied any current alcohol or illicit drug use. Mr. L’s urine drug screen was negative.

External medication records showed Mr. L had been prescribed haloperidol, risperidone, chlorpromazine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, bupropion, sodium valproate, and topiramate, for the treatment of schizophrenia, with no significant improvement.

Continue to: On hospital Day 3, Mr. L...

On hospital Day 3, Mr. L was started on clozapine, 12.5 mg at bedtime, and titrated to 300 mg by Day 15. The clozapine was titrated slowly; initially the dose was doubled every 2 days up to 100 mg every night at bedtime, then it was increased by 50 mg every 2 to 3 days up to 300 mg every night at bedtime. A baseline complete blood count with differential confirmed that his absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was >1,500 µL, which is above the reference range. Mr. L was closely monitored for agranulocytosis and had weekly blood work for ANC. Additionally, his information was updated regularly on the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy website.

After Mr. L began the clozapine regimen, he had reduced mood lability, paranoia, and delusions; significantly improved auditory and visual hallucinations; and reduced distress. His sleep was improved, and he appeared pleasant with clear sensorium. During this period, Mr. L developed sialorrhea and was administered glycopyrrolate and prescribed diphenhydramine, as needed for sleep. Although he had been prescribed oral benztropine for extrapyramidal side effects prophylaxis, this medication was never administered to him during his stay in the hospital. He became stable on this regimen, and the treatment team started working on his discharge.

On hospital Day 20, Mr. L complained about abdominal pain. At first, the pain was localized to right upper quadrant; later, he had diffuse abdominal pain with distension. He reported that he had no bowel movement for 1 day. The treatment team instructed him to take nothing by mouth, and all antipsychotic and anticholinergic medications were held. Given Mr. L’s HIV status, the treatment team ordered liver function tests (LFTs) and an abdominal x-ray. Mr. L’s LFT results were normal and the x-ray findings were inconclusive. However, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an obstruction due to a 3.5-cm stoolball in the proximal transverse colon with fecal impaction. Mr. L was started on a saline enema, which resulted in him having 2 to 3 episodes of watery diarrhea, and his abdominal pain resolved.

Although Mr. L reported feeling better and started eating again, there were concerns about his watery bowel movement, so a repeat abdominal x-ray was ordered. The x-ray confirmed that Mr. L had a persistent bowel obstruction. Mr. L’s abdominal pain returned. At this time, the pain was diffuse and severe, and Mr. L was vomiting. Mr. L was started on a bisacodyl suppository immediately, and then twice daily as needed. Subsequently, Mr. L had a solid bowel movement and relief of all GI symptoms. Mr. L was administered docusate sodium twice daily. Repeated x-rays of the abdomen confirmed the obstructive changes of the small bowel had resolved.

Why constipation may be overlooked

Although constipation is a common adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, when it emerges during clozapine therapy, it can lead to ileus, which can be fatal. Mr. L’s case highlighted that clozapine use can cause intestinal obstruction, a condition that can deteriorate within a few hours to life-threatening ileus. The extent of fecal impaction can be masked by spurious diarrhea, as illustrated in Mr. L’s case.5 Clozapine has anti-serotonergic properties (5HT-2A antagonist) that may result in reduced intestinal nociception pain. This discrepancy between physical symptoms and the severity of illness may cause delays in diagnosis.4 As soon as the treatment team determined Mr. L was constipated, all medications with anticholinergic effects were held. Patients also may have difficulty reporting intestinal pain due to psychotic symptoms such as paranoia or thought disorder.6

Take steps to prevent constipation

To prevent constipation in patients receiving clozapine, minimize the use of systemic anticholinergic agents because of the adverse effects of this interaction. For example, in Mr. L’s case, he received both clozapine and glycopyrrolate. In addition, all patients who are prescribed clozapine should receive docusate sodium to prevent constipation. However, because docusate sodium alone is usually not sufficient, consider adding another agent. Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol 3350, are suitable additional agents. If this combination does not work, then consider senna glycoside or bisacodyl, which will increase intestinal motility and help with the flow of water into the bowel, thereby improving constipation. Bulk agents should be avoided because they can make constipation worse, especially if the patient is not drinking enough water, which is often the case with patients who have psychosis.7

Ask patients about GI symptoms

Clinicians need to observe and monitor patients who receive clozapine for signs of constipation, including the frequency and difficulty of defecation during treatment.4 It is important to ask patients about bowel function. Before starting treatment with clozapine, discuss the risks of clozapine-induced intestinal obstruction with patients and caregivers, and encourage them to report any GI symptoms. Also, provide dietary advice and recommend the as-needed use of laxatives.

1. Patchan KM, Richardson C, Vyas G, et al. The risk of suicide after clozapine discontinuation: cause for concern. Ann Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):253-256.

2. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(3):162-167.

3. Hayes G, Gibler B. Clozapine-induced constipation. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):298.

4. Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, et al. Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):759-768.

5. Drew L, Herdson P. Clozapine and constipation: a serious issue. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997; 31(1):149-150.

6. Bickerstaff LK, Harris SC, Leggett RS, et al. Pain insensitivity in schizophrenic patients: a surgical dilemma. Arch Surg. 1988;123(1):49-51.

7. Psychopharmacology Institute. How to manage adverse effects of clozapine – Part 1. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://psychopharmacologyinstitute.com/publication/how-to-manage-adverse-effects-of-clozapine-part-1-2476

Clozapine is the most effective second-generation antipsychotic for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. It can reduce delusions and hallucinations in patients who are unresponsive to other antipsychotic medications. Further, clozapine is the only agent known to reduce suicidal urges.1

Unfortunately, clozapine is associated with numerous adverse effects, most notably agranulocytosis, a rare but potentially fatal adverse effect that occurs in approximately 1% to 2% of patients during the first year of treatment.2 Other adverse effects associated with clozapine are weight gain, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, sialorrhea, constipation, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, myocarditis, and seizures. Among these adverse effects, constipation, which can progress to life-threatening gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility and ileus, is often overlooked. Up to 60% of patients who are administered clozapine experience constipation.3 A recent review found that potentially life-threatening clozapine-induced ileus occurred in approximately 3 per 1,000 patients, and 28 deaths have been documented.4

In this case report, I describe a patient who received clozapine and experienced constipation that led to an intestinal obstruction. I discuss the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment approaches to prevent severe constipation in patients who are prescribed clozapine.

CASE REPORT

Mr. L, age 24, has schizophrenia, depression, mild intellectual disability, and congenital human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He has had multiple unsuccessful antipsychotic trials but is compliant with highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV. After experiencing worsening aggressive behavior for a third time, Mr. L was involuntarily committed to our Crises Response Center.

Mr. L was admitted to the acute inpatient psychiatry unit. He reported having auditory hallucinations, which included whispering sounds with intermittent music, mostly at night. He also reported decreased sleep, poor appetite, and low energy, but denied feelings of depression or mania.

During the mental status examination, Mr. L was calm and cooperative, but easily distracted. He said he smoked cigarettes but denied any current alcohol or illicit drug use. Mr. L’s urine drug screen was negative.

External medication records showed Mr. L had been prescribed haloperidol, risperidone, chlorpromazine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, bupropion, sodium valproate, and topiramate, for the treatment of schizophrenia, with no significant improvement.

Continue to: On hospital Day 3, Mr. L...

On hospital Day 3, Mr. L was started on clozapine, 12.5 mg at bedtime, and titrated to 300 mg by Day 15. The clozapine was titrated slowly; initially the dose was doubled every 2 days up to 100 mg every night at bedtime, then it was increased by 50 mg every 2 to 3 days up to 300 mg every night at bedtime. A baseline complete blood count with differential confirmed that his absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was >1,500 µL, which is above the reference range. Mr. L was closely monitored for agranulocytosis and had weekly blood work for ANC. Additionally, his information was updated regularly on the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy website.

After Mr. L began the clozapine regimen, he had reduced mood lability, paranoia, and delusions; significantly improved auditory and visual hallucinations; and reduced distress. His sleep was improved, and he appeared pleasant with clear sensorium. During this period, Mr. L developed sialorrhea and was administered glycopyrrolate and prescribed diphenhydramine, as needed for sleep. Although he had been prescribed oral benztropine for extrapyramidal side effects prophylaxis, this medication was never administered to him during his stay in the hospital. He became stable on this regimen, and the treatment team started working on his discharge.

On hospital Day 20, Mr. L complained about abdominal pain. At first, the pain was localized to right upper quadrant; later, he had diffuse abdominal pain with distension. He reported that he had no bowel movement for 1 day. The treatment team instructed him to take nothing by mouth, and all antipsychotic and anticholinergic medications were held. Given Mr. L’s HIV status, the treatment team ordered liver function tests (LFTs) and an abdominal x-ray. Mr. L’s LFT results were normal and the x-ray findings were inconclusive. However, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an obstruction due to a 3.5-cm stoolball in the proximal transverse colon with fecal impaction. Mr. L was started on a saline enema, which resulted in him having 2 to 3 episodes of watery diarrhea, and his abdominal pain resolved.

Although Mr. L reported feeling better and started eating again, there were concerns about his watery bowel movement, so a repeat abdominal x-ray was ordered. The x-ray confirmed that Mr. L had a persistent bowel obstruction. Mr. L’s abdominal pain returned. At this time, the pain was diffuse and severe, and Mr. L was vomiting. Mr. L was started on a bisacodyl suppository immediately, and then twice daily as needed. Subsequently, Mr. L had a solid bowel movement and relief of all GI symptoms. Mr. L was administered docusate sodium twice daily. Repeated x-rays of the abdomen confirmed the obstructive changes of the small bowel had resolved.

Why constipation may be overlooked

Although constipation is a common adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, when it emerges during clozapine therapy, it can lead to ileus, which can be fatal. Mr. L’s case highlighted that clozapine use can cause intestinal obstruction, a condition that can deteriorate within a few hours to life-threatening ileus. The extent of fecal impaction can be masked by spurious diarrhea, as illustrated in Mr. L’s case.5 Clozapine has anti-serotonergic properties (5HT-2A antagonist) that may result in reduced intestinal nociception pain. This discrepancy between physical symptoms and the severity of illness may cause delays in diagnosis.4 As soon as the treatment team determined Mr. L was constipated, all medications with anticholinergic effects were held. Patients also may have difficulty reporting intestinal pain due to psychotic symptoms such as paranoia or thought disorder.6

Take steps to prevent constipation

To prevent constipation in patients receiving clozapine, minimize the use of systemic anticholinergic agents because of the adverse effects of this interaction. For example, in Mr. L’s case, he received both clozapine and glycopyrrolate. In addition, all patients who are prescribed clozapine should receive docusate sodium to prevent constipation. However, because docusate sodium alone is usually not sufficient, consider adding another agent. Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol 3350, are suitable additional agents. If this combination does not work, then consider senna glycoside or bisacodyl, which will increase intestinal motility and help with the flow of water into the bowel, thereby improving constipation. Bulk agents should be avoided because they can make constipation worse, especially if the patient is not drinking enough water, which is often the case with patients who have psychosis.7

Ask patients about GI symptoms

Clinicians need to observe and monitor patients who receive clozapine for signs of constipation, including the frequency and difficulty of defecation during treatment.4 It is important to ask patients about bowel function. Before starting treatment with clozapine, discuss the risks of clozapine-induced intestinal obstruction with patients and caregivers, and encourage them to report any GI symptoms. Also, provide dietary advice and recommend the as-needed use of laxatives.

Clozapine is the most effective second-generation antipsychotic for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. It can reduce delusions and hallucinations in patients who are unresponsive to other antipsychotic medications. Further, clozapine is the only agent known to reduce suicidal urges.1

Unfortunately, clozapine is associated with numerous adverse effects, most notably agranulocytosis, a rare but potentially fatal adverse effect that occurs in approximately 1% to 2% of patients during the first year of treatment.2 Other adverse effects associated with clozapine are weight gain, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, sialorrhea, constipation, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, myocarditis, and seizures. Among these adverse effects, constipation, which can progress to life-threatening gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility and ileus, is often overlooked. Up to 60% of patients who are administered clozapine experience constipation.3 A recent review found that potentially life-threatening clozapine-induced ileus occurred in approximately 3 per 1,000 patients, and 28 deaths have been documented.4

In this case report, I describe a patient who received clozapine and experienced constipation that led to an intestinal obstruction. I discuss the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment approaches to prevent severe constipation in patients who are prescribed clozapine.

CASE REPORT

Mr. L, age 24, has schizophrenia, depression, mild intellectual disability, and congenital human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He has had multiple unsuccessful antipsychotic trials but is compliant with highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV. After experiencing worsening aggressive behavior for a third time, Mr. L was involuntarily committed to our Crises Response Center.

Mr. L was admitted to the acute inpatient psychiatry unit. He reported having auditory hallucinations, which included whispering sounds with intermittent music, mostly at night. He also reported decreased sleep, poor appetite, and low energy, but denied feelings of depression or mania.

During the mental status examination, Mr. L was calm and cooperative, but easily distracted. He said he smoked cigarettes but denied any current alcohol or illicit drug use. Mr. L’s urine drug screen was negative.

External medication records showed Mr. L had been prescribed haloperidol, risperidone, chlorpromazine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, bupropion, sodium valproate, and topiramate, for the treatment of schizophrenia, with no significant improvement.

Continue to: On hospital Day 3, Mr. L...

On hospital Day 3, Mr. L was started on clozapine, 12.5 mg at bedtime, and titrated to 300 mg by Day 15. The clozapine was titrated slowly; initially the dose was doubled every 2 days up to 100 mg every night at bedtime, then it was increased by 50 mg every 2 to 3 days up to 300 mg every night at bedtime. A baseline complete blood count with differential confirmed that his absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was >1,500 µL, which is above the reference range. Mr. L was closely monitored for agranulocytosis and had weekly blood work for ANC. Additionally, his information was updated regularly on the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy website.

After Mr. L began the clozapine regimen, he had reduced mood lability, paranoia, and delusions; significantly improved auditory and visual hallucinations; and reduced distress. His sleep was improved, and he appeared pleasant with clear sensorium. During this period, Mr. L developed sialorrhea and was administered glycopyrrolate and prescribed diphenhydramine, as needed for sleep. Although he had been prescribed oral benztropine for extrapyramidal side effects prophylaxis, this medication was never administered to him during his stay in the hospital. He became stable on this regimen, and the treatment team started working on his discharge.

On hospital Day 20, Mr. L complained about abdominal pain. At first, the pain was localized to right upper quadrant; later, he had diffuse abdominal pain with distension. He reported that he had no bowel movement for 1 day. The treatment team instructed him to take nothing by mouth, and all antipsychotic and anticholinergic medications were held. Given Mr. L’s HIV status, the treatment team ordered liver function tests (LFTs) and an abdominal x-ray. Mr. L’s LFT results were normal and the x-ray findings were inconclusive. However, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an obstruction due to a 3.5-cm stoolball in the proximal transverse colon with fecal impaction. Mr. L was started on a saline enema, which resulted in him having 2 to 3 episodes of watery diarrhea, and his abdominal pain resolved.

Although Mr. L reported feeling better and started eating again, there were concerns about his watery bowel movement, so a repeat abdominal x-ray was ordered. The x-ray confirmed that Mr. L had a persistent bowel obstruction. Mr. L’s abdominal pain returned. At this time, the pain was diffuse and severe, and Mr. L was vomiting. Mr. L was started on a bisacodyl suppository immediately, and then twice daily as needed. Subsequently, Mr. L had a solid bowel movement and relief of all GI symptoms. Mr. L was administered docusate sodium twice daily. Repeated x-rays of the abdomen confirmed the obstructive changes of the small bowel had resolved.

Why constipation may be overlooked

Although constipation is a common adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, when it emerges during clozapine therapy, it can lead to ileus, which can be fatal. Mr. L’s case highlighted that clozapine use can cause intestinal obstruction, a condition that can deteriorate within a few hours to life-threatening ileus. The extent of fecal impaction can be masked by spurious diarrhea, as illustrated in Mr. L’s case.5 Clozapine has anti-serotonergic properties (5HT-2A antagonist) that may result in reduced intestinal nociception pain. This discrepancy between physical symptoms and the severity of illness may cause delays in diagnosis.4 As soon as the treatment team determined Mr. L was constipated, all medications with anticholinergic effects were held. Patients also may have difficulty reporting intestinal pain due to psychotic symptoms such as paranoia or thought disorder.6

Take steps to prevent constipation

To prevent constipation in patients receiving clozapine, minimize the use of systemic anticholinergic agents because of the adverse effects of this interaction. For example, in Mr. L’s case, he received both clozapine and glycopyrrolate. In addition, all patients who are prescribed clozapine should receive docusate sodium to prevent constipation. However, because docusate sodium alone is usually not sufficient, consider adding another agent. Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol 3350, are suitable additional agents. If this combination does not work, then consider senna glycoside or bisacodyl, which will increase intestinal motility and help with the flow of water into the bowel, thereby improving constipation. Bulk agents should be avoided because they can make constipation worse, especially if the patient is not drinking enough water, which is often the case with patients who have psychosis.7

Ask patients about GI symptoms

Clinicians need to observe and monitor patients who receive clozapine for signs of constipation, including the frequency and difficulty of defecation during treatment.4 It is important to ask patients about bowel function. Before starting treatment with clozapine, discuss the risks of clozapine-induced intestinal obstruction with patients and caregivers, and encourage them to report any GI symptoms. Also, provide dietary advice and recommend the as-needed use of laxatives.

1. Patchan KM, Richardson C, Vyas G, et al. The risk of suicide after clozapine discontinuation: cause for concern. Ann Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):253-256.

2. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(3):162-167.

3. Hayes G, Gibler B. Clozapine-induced constipation. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):298.

4. Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, et al. Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):759-768.

5. Drew L, Herdson P. Clozapine and constipation: a serious issue. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997; 31(1):149-150.

6. Bickerstaff LK, Harris SC, Leggett RS, et al. Pain insensitivity in schizophrenic patients: a surgical dilemma. Arch Surg. 1988;123(1):49-51.

7. Psychopharmacology Institute. How to manage adverse effects of clozapine – Part 1. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://psychopharmacologyinstitute.com/publication/how-to-manage-adverse-effects-of-clozapine-part-1-2476

1. Patchan KM, Richardson C, Vyas G, et al. The risk of suicide after clozapine discontinuation: cause for concern. Ann Clinical Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):253-256.

2. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(3):162-167.

3. Hayes G, Gibler B. Clozapine-induced constipation. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):298.

4. Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, et al. Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):759-768.

5. Drew L, Herdson P. Clozapine and constipation: a serious issue. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997; 31(1):149-150.

6. Bickerstaff LK, Harris SC, Leggett RS, et al. Pain insensitivity in schizophrenic patients: a surgical dilemma. Arch Surg. 1988;123(1):49-51.

7. Psychopharmacology Institute. How to manage adverse effects of clozapine – Part 1. Updated June 3, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://psychopharmacologyinstitute.com/publication/how-to-manage-adverse-effects-of-clozapine-part-1-2476

Death anxiety among psychiatry trainees during COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

The far-reaching effects of death anxiety

Postgraduate psychiatry training may expose one to stressful situations with adverse psychologic consequences.1 Furthermore, when caring for patients, psychiatry trainees frequently need to face issues of death and dying in the form of suicide risk assessments, grief and bereavement processes, near-death experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psycho-oncology rotations. Because these interactions are incredibly personal, the emotions they provoke inevitably affect every interaction, theoretical discussion, diagnostic work-up, and treatment plan.

How each of us experiences death anxiety is unique. For some, it could be a fear of nonexistence, ultimate loss, disruption of the flow of life, worry about leaving loved ones behind, or fear of pain or loneliness in dying. Some might fear an untimely or violent death and subsequent judgment and retributions. The literature suggests that fear of death may be at the root of various mental health problems and, if left unaddressed, may adversely impact long-term treatment outcomes.2 Despite this, many standard treatment approaches typically do not target death anxiety, which potentially contributes to a “revolving door” of mental health problems.3

American existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom, MD, cautioned psychiatrists not to “scratch where it does not itch.”4 Yet death, according to Dr. Yalom, does itch. Violent death is that caused by human intent or negligence, and is characterized by feeling helpless and terrorized at the time of dying. It may occur as an acute incident that denies the dying individual and his/her family members the time and space to prepare for the death.5 For survivors, accommodating the mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual effects of violent death is a complex process that rarely has a conclusion. It often is accompanied by survivors’ guilt, which is replayed in the form of flashbacks and nightmares.6 With this understanding, I view COVID-19 deaths as violent deaths.

Pay close attention to countertransference

As much as we influence our patients and their families, we also are profoundly influenced by them. We need to pay attention to any feelings our clinical encounters generate within us, and to carefully use these feelings in our clinical judgment, and not just make causal inferences. For instance, if a clinician thinks that a patient with suicidal ideation would be better off dead, these feelings are a reliable indicator that the patient is, indeed, at a high risk of completing suicide.7 It is our ethical and moral responsibility towards our patients to listen to our countertransference responses. The aim is to identify countertransference and use it to inform us, not to rule us. By taking an active role in managing our emotional responses in the face of loss, we can harness the spirit of resilience. This is not always as easy as it seems. We need our peers, experienced clinicians, and supervisors to help us explore our feelings, resistances, and countertransference reactions.

Strategies to combat burnout

Psychiatric trainees must be encouraged to establish and maintain rigorous plans of self-care to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Most importantly, training programs must diversify residents’ clinical exposure by providing activities that promote mental health promotion activities, scholarly endeavors, and peer support groups. This will help trainees to restore meaning and purpose in life beyond.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

1. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. What are some stressful adversities in psychiatry residency training, and how should they be managed professionally? Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):145-150.

2. Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, et al. Death anxiety across the adult years: an examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31(6):549-561.

3. Lisa I, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(7):580-593.

4. Yalom ID. Staring at the sun: being at peace with your own mortality. London, UK: Piatkus; 2011.

5. Rynearson EK, Johnson TA, Correa F. The horror and helplessness of violent death. In: Katz RS, Johnson TA (eds). When professionals weep: emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016:91-103.

6. Breggin PR. Guilt, shame, and anxiety: understanding and overcoming negative emotions. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books; 2014.

7. Katz RS, Johnson TA, (eds). When professionals weep: Emotional and countertransference responses in palliative and end-of-life care. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2016.

Virtual residency/fellowship interviews: The good, the bad, and the future

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

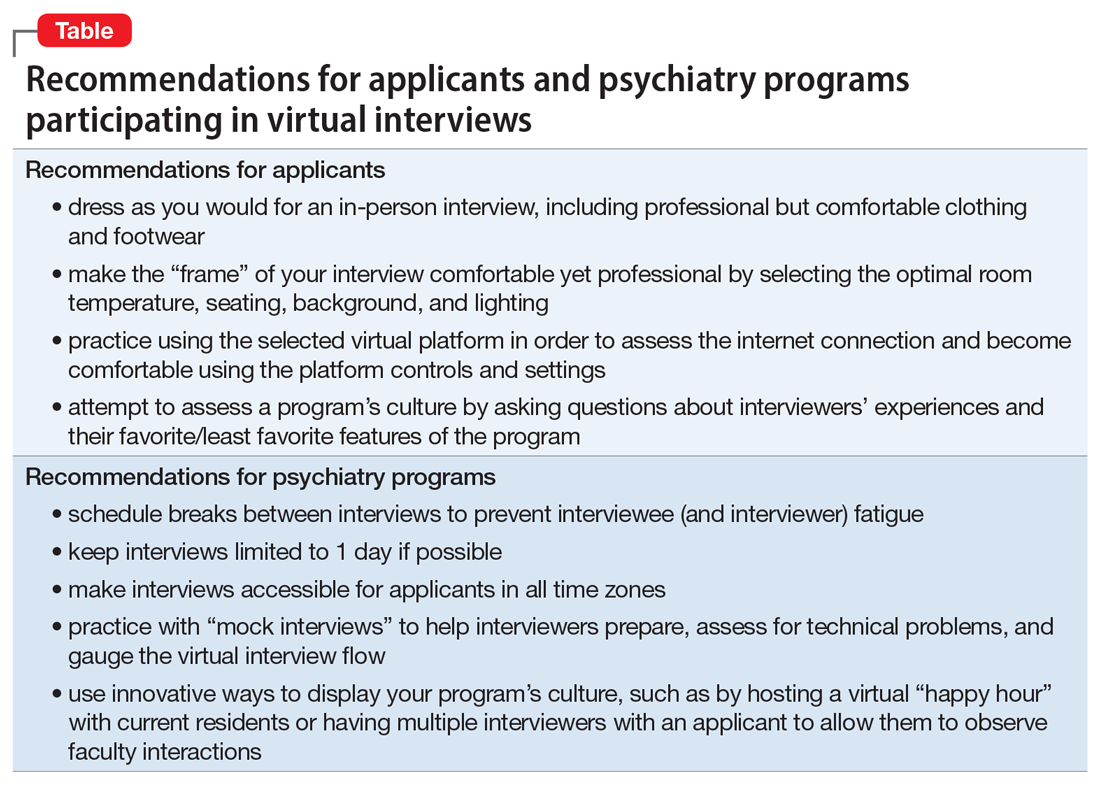

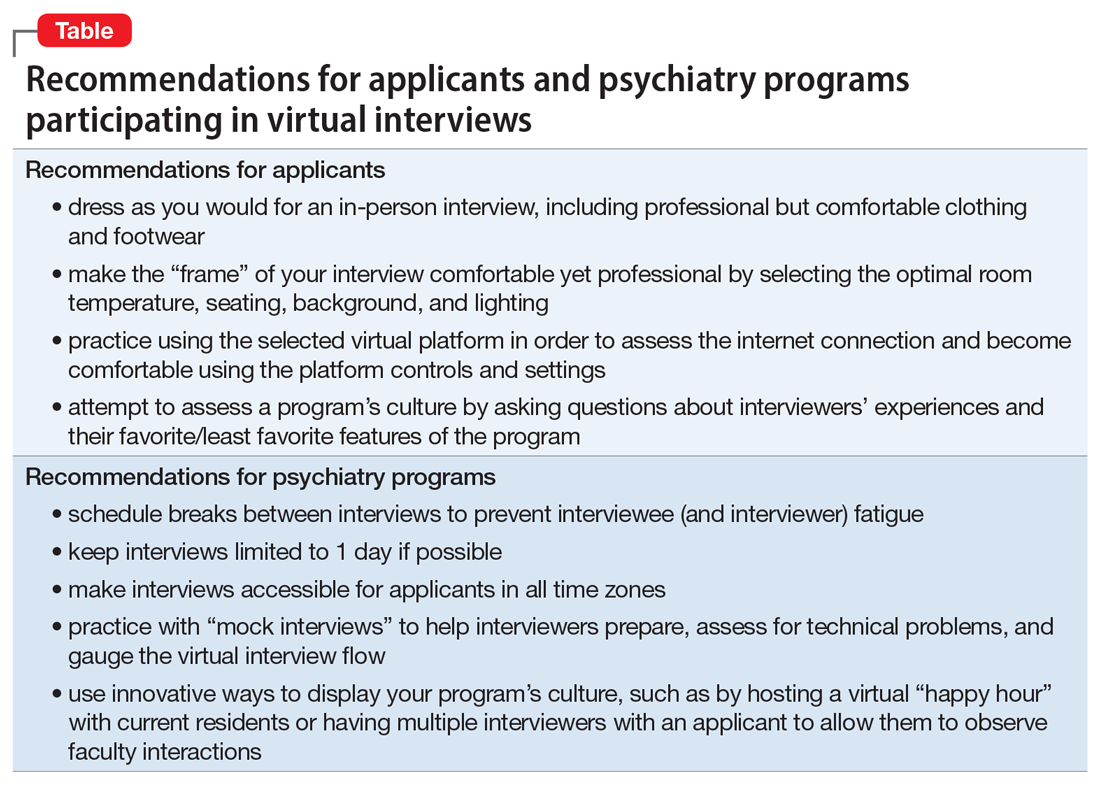

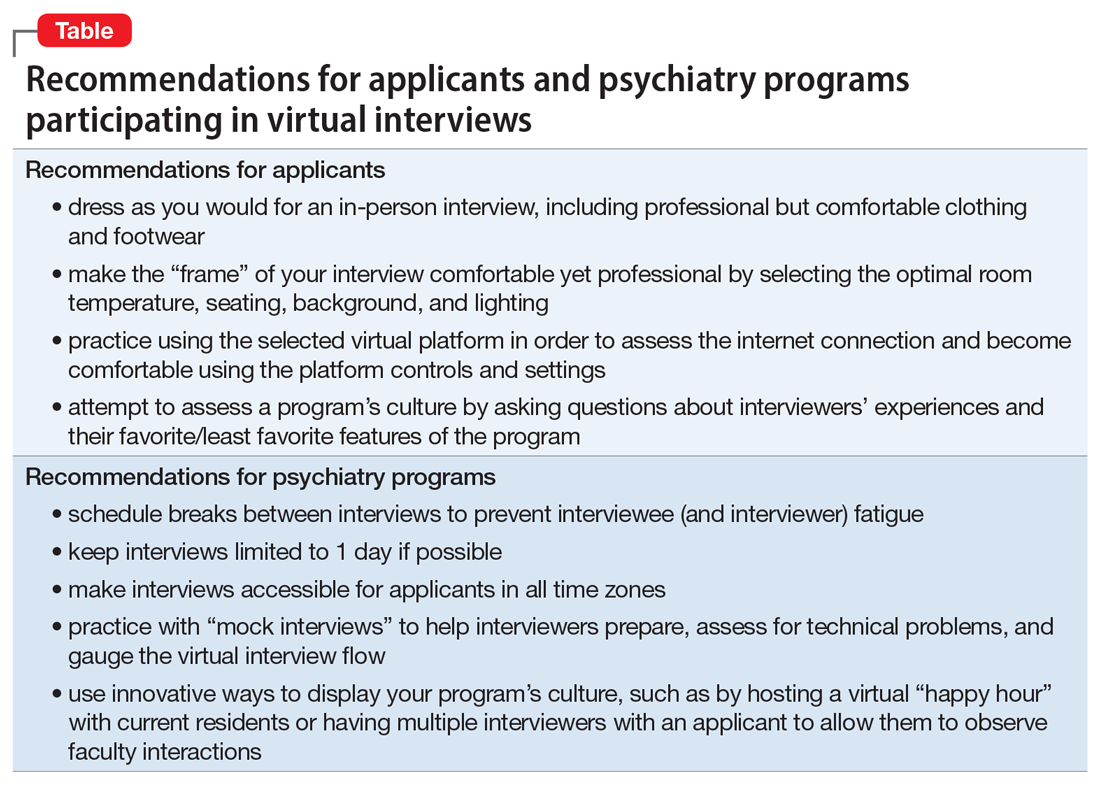

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

1. Arbuckle M, Kerlek A, Kovach J, et al. Consensus statement from the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) and the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) on the 2020-21 Residency Application Cycle. https://www.aadprt.org/application/files/8816/0017/8240/admsep_aadprt_statement_9-14-20_Rev.pdf. Published May 18, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2020.

2. Seifi A, Mirahmadizadeh A, Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238239.

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

As a psychiatry resident in the age of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many of my educational experiences have undergone adjustments. Now, as I interview for a fellowship, I see firsthand that recruitment activities have not been spared from shifting paradigms levied by the pandemic. To adhere to social distancing guidelines and limit trainee interpersonal exposure, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training recommended that all psychiatry residency interviews be conducted virtually for 2020/2021.1 Trainees and programs alike are embarking on a new frontier of virtual interviews, and it is important that we evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Because uncertainty abounds regarding when a sense of normalcy might eventually return to psychiatry residency and fellowship recruitment activities, I also provide recommendations to interviewers and interviewees who may navigate virtual recruitment in the future.

Advantages of virtual interviews

An immediately significant advantage of virtual interviews is the lack of travel, which for some applicants can be cost-prohibitive. The costs of airfare, rental vehicles, and lodging in multiple cities can add up, sometimes requiring students to budget interview travel into already-high student loans. In some cases, applicants may have limited days to interview, which makes the flexibility afforded by the lack of travel advantageous. Furthermore, navigating new locations can add to preexisting interview stress. Without travel, applicants can consider a broader set of programs and accept more interviews.

Another advantage is that virtual interviews allow interviewees latitude to shift the interview’s “frame.” Rather than sitting in an interviewer’s office, interviewees can choose a more comfortable environment for themselves, imparting a “home-field advantage” that may put them at ease. During my fellowship interviews, controlling the room temperature, using a familiar chair, and wearing comfortable shoes helped to reduce the anxiety inherent to interviewing.

Disadvantages of virtual interviews

Any new or unfamiliar experience can impart challenges. For example, applicants and interviewers must adjust to and observe different sets of etiquette during virtual interviews. These include muting microphones to avoid talking over each other, maintaining consistent eye contact, avoiding multitasking, and following up to avoid miscommunication.

Another potential problem is that virtual interviews can dampen an applicant’s ability to appreciate a program’s culture. Observing informal interactions between trainees and faculty is often as important as the formal interviews in ascertaining which programs have a supportive culture. Because my virtual fellowship interviews have generally been limited to formal one-on-one interviews, assessing program culture has become more challenging. Conversely, programs may find it difficult to grasp an applicant’s temperament and interaction style.

Virtual interviewing, while undeniably convenient in many regards, may fall prey to its own convenience. There can be disparities in the quantity, duration, and frequency of interviews. For me, the number of and time allotted for interviews has varied widely, ranging from 2.5 to 8 hours. The amount of allotted break time has also differed, with some programs providing longer breaks between interviews (30 to 60 minutes) and others offering shorter (5 to 10 minutes) or no breaks. Minimal breaks may fatigue applicants, while longer breaks may seem like wasted time. While virtual interviews may require no physical travel between offices, breaks are a necessity that should be implemented thoughtfully.

Finally, a troublesome challenge I encountered surprisingly often was unreliable internet service and other technical difficulties. Several times, my interviewers’ (or my) screen froze or shut off due to connectivity issues. This is an obstacle unique to virtual interviews that requires both a backup plan as well as patience and calm to navigate during an already taxing situation.

Continue to: What's next?

What’s next?

As applicants and programs adjust to the realities of virtual interviewing, this is likely an unfamiliar experience for all. While the benefits and shortcomings must be considered together, I, along with many of my peers,2 continue to prefer traditional in-person interviews. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes in-person interviews difficult, applicants and programs must embrace the experience of virtual interviews. However, a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages are instrumental in preempting prospective challenges. Based on my recent experiences with virtual fellowship interviews, I have created some recommendations for applicants and psychiatry programs participating in virtual recruitment (Table).

After the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, it is conceivable that the advantages of virtual interviewing may justify its continued use. For example, applicants may be able to apply to geographically diverse programs without travel expenses. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence regarding virtual interviews specifically in psychiatry training programs, but the experiences of both applicants and psychiatry programs during this atypical time will allow us to improve the process going forward, and evaluate its utility well after COVID-19 recedes.

1. Arbuckle M, Kerlek A, Kovach J, et al. Consensus statement from the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) and the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) on the 2020-21 Residency Application Cycle. https://www.aadprt.org/application/files/8816/0017/8240/admsep_aadprt_statement_9-14-20_Rev.pdf. Published May 18, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2020.

2. Seifi A, Mirahmadizadeh A, Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238239.

1. Arbuckle M, Kerlek A, Kovach J, et al. Consensus statement from the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) and the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) on the 2020-21 Residency Application Cycle. https://www.aadprt.org/application/files/8816/0017/8240/admsep_aadprt_statement_9-14-20_Rev.pdf. Published May 18, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2020.

2. Seifi A, Mirahmadizadeh A, Eslami V. Perception of medical students and residents about virtual interviews for residency applications in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0238239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238239.

COVID-19’s religious strain: Differentiating spirituality from pathology

As the world grapples with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the search for answers, comfort, how to cope, and how to make sense of it all has become paramount. People commonly turn to their faith in times of crisis, but this recent global public health emergency is unlike many have ever seen or could have imagined.1 What happens when the well-intentioned journey for spiritual insight intersects with psychiatric symptomatology? Where does the line between these phenomena get crossed? As a psychiatric resident and person who was raised in the Pentecostal faith, I have observed faith and psychopathology come to a head in the last 6 months. COVID-19 has dealt a religious strain of undocumented cases; I hope to shed light on the topic by sharing my experience of navigating the assessment and treatment plan of patients with psychiatric symptoms whose spiritual beliefs are a cornerstone of life.

Piety, or pathology?

The following approaches have helped me to identify what is driven by faith vs what is psychopathology:

While taking the patient history. Obtaining a history from a patient who professes to have strong spiritual beliefs and presents with psychiatric symptoms is similar to a standard patient interview, but pay special attention to how the patient came to the emergency department. Was there a family member, friend, or emergency medical services present at that time? During the interview, patients often appear “normal,” which may lead a clinician to question the reason for the consult, yet considering the recent events preceding the presentation will be a good place to start gathering the appropriate information for investigation.

Next, compare the patient’s recent daily functioning with his/her baseline. If this information comes solely from the patient, it may be skewed, so try to retrieve information from a collateral source. If the patient was accompanied by someone, request permission from the patient to speak with him/her. It may also be best in some instances to speak with the collateral source out of earshot of the patient. Be aware that collateral information that comes from just one source also could be biased, so search for additional contacts to help acquire a comprehensive representation of the circumstances.

Information about a patient could come from a faith leader because people often rely on their faith leaders when they are ill, in need of support, or in crisis.2 Faith leaders may have valuable information and insight into the patient and the history of the patient’s illness. In addition, diverse sources of collateral reports may be helpful because specific spiritual views and practices can vary even within one family or congregation. What may be an abnormal practice to some followers may be normal for others.3 When approaching these situations with parishioners, it is essential to maintain confidentiality.

While performing the clinical examination. As with any psychiatric diagnosis, other causative factors (metabolic and organic) need to be ruled out. Also, assess for the use of mood-altering substances. The patient may express offense or resistance to such questions, but maintain a matter-of-fact approach and explain that assessment for substance use is a routine part of the clinical examination. Approximately 18% of people in the United States with psychiatric disorders have a comorbid substance use disorder.4 However, keep in mind that a patient who refuses substance use screening is not necessarily hiding something. The road to being thorough may lead to strained rapport with the patient, and this risk must be balanced with providing the best care. As in any other clinical situation, seek evidence to both verify and clarify information without being deterred by a patient’s vocalization of spiritual tenants.

Learn about your patients’ beliefs

Do not feel defeated if you find these interviews difficult. Religion and symptomatology can overlap and fluctuate within the same faith group, which can make these types of assessments complex.5 In an effort to understand the patient more clearly, be sensitive to their spiritual practices and receptive to learning about unfamiliar spiritual beliefs. Be transparent about not knowing a specific belief or practice, and exhibit humility. Most patients are open to sharing their religious/spiritual views with a clinician who is sincere about wanting insight. Understanding the value of spiritual care is an important skill that many medical practitioners often lack.6 This understanding is especially critical when patients express worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic and how they are coping.

Continue to: Integrate your patient's spiritual requests

Integrate your patient’s spiritual requests