User login

Update in Hospital Medicine relays important findings

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Avoid presumptions with LGBTQ+ patients

More than 11 million individuals in the United States identify as LGBTQ+, and data show that this population has a shorter life expectancy and increased rates of suicide, violence, and cardiovascular disease, according to Keshav Khanijow, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and Nicole Rosendale, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

More than half of these individuals report experiencing discrimination, and one in three transgendered individuals have reported prejudice when visiting a doctor or health clinic, they said in a presentation at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“It is impossible to know how someone identifies by gender just by looking at them,” Dr. Rosendale emphasized.

However, attention to terminology, use of affirming language and documentation, and attention to clinical considerations can help LGBTQ+ patients feel comfortable in the health care setting.

Ask, don’t assume

Do ask patients how they identify themselves, Dr. Khanijow said. It is important to ask about sexual orientation as part of a social history. One big “Don’t” in terminology is to avoid the use of the term “homosexual,” he added. Although the description “homosexual” began as a scientific term, it has become associated with pathology, rather than identity, and is often used by hate groups. Also, do not assume sexual orientation based on a patient’s partner.

Always ask about sexual orientation before assuming it, and include that information in documentation. Dr. Khanijow used an example of a “one-liner” case of a 45-year-old male who self-identifies as “queer” and presents with a migraine. The most appropriate version would be “45yoM who identifies as queer with PMHx Migraines presents with Headache,” Dr. Khanijow said. However, as a clinician, consider why you are including sexual orientation in the one-liner. If there isn’t any real reason to include it (such as stress related to coming out, increased risk for other conditions) it may not be necessary in all visits.

Transgender considerations

Dr. Khanijow shared some specific considerations for the transgender/nonbinary population.

In terms of gender, “it is most respectful to identify the patient as they would like to be identified,” he said.

Ask how they identify their gender, including their preferred pronouns, and be sure to note this identification in their documents, he said. Be vigilant in addressing a transgender patient correctly. Mistakes happen, and when they do, correct yourself, apologize succinctly and move on.

Clinical challenges

Research on LGBTQ+ health is limited, and these individuals are often grouped into a single category despite diverse experiences, Dr. Rosendale said. Another limitation in LGBTQ+ research is that some studies assess based on identity (such as gay, lesbian, bisexual) while others assess behavior (studies of men who have sex with men).

Dr. Rosendale went on to highlight several important clinical concerns for the LGBTQ+ population. Compared with the general population, lesbian women are at higher risk for breast cancer, and gay men are at increased risk for prostate, colon, and testicular cancers. Potential heart disease risk factors of physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking are more prevalent among lesbian women, and tobacco and alcohol use are more prevalent among gay men, and men who have sex with men are at increased risk for STIs.

Clinicians also should be aware that “bisexual individuals face worse health outcomes than their lesbian, gay, and heterosexual counterparts,” Dr. Rosendale said.

LGBTQ+ patients often use hormone therapy, so clinicians should be aware of some potential adverse effects, Dr. Rosendale said. For example, trans women on gender-affirming estrogen therapy may have increased cardiovascular risks including incident MI, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular mortality, compared with cisgender women.

In trans men, testosterone use has not been definitively linked to cardiovascular risk, although patients may show small changes in systolic blood pressure, lipid profiles, and blood glucose, Dr. Rosendale noted.

In-hospital issues

Inpatient and critical care of transgender and LGBTQ+ patients may have unique psychosocial considerations in hospital care, Dr. Rosendale said. To provide some guidance, a document on “Transgender-Affirming Hospital Policies” has been developed jointly by Lamda Legal, the Human Rights Campaign, the law firm of Hogan Lovells, and the New York City Bar.

Best practices noted in the document include rooming transgender individuals according to their identity, and recognizing that these patients may experience additional stress while an inpatient if personal clothing or other means of gender expression are replaced during the hospital stay, Dr. Rosendale noted.

Finally, clinicians seeing LGBTQ+ patients in an acute care setting should keep in mind that socioeconomic disparities may limit access to outpatient care, and that this population has higher rates of unemployment, exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Rosendale said. In addition, she advised clinicians to be aware that LGBTQ+ people may experience discrimination in rehabilitation centers, and their surrogate decision makers may be individuals other than family members.

Dr. Khanijow and Dr. Rosendale had no financial conflicts to disclose.

More than 11 million individuals in the United States identify as LGBTQ+, and data show that this population has a shorter life expectancy and increased rates of suicide, violence, and cardiovascular disease, according to Keshav Khanijow, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and Nicole Rosendale, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

More than half of these individuals report experiencing discrimination, and one in three transgendered individuals have reported prejudice when visiting a doctor or health clinic, they said in a presentation at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“It is impossible to know how someone identifies by gender just by looking at them,” Dr. Rosendale emphasized.

However, attention to terminology, use of affirming language and documentation, and attention to clinical considerations can help LGBTQ+ patients feel comfortable in the health care setting.

Ask, don’t assume

Do ask patients how they identify themselves, Dr. Khanijow said. It is important to ask about sexual orientation as part of a social history. One big “Don’t” in terminology is to avoid the use of the term “homosexual,” he added. Although the description “homosexual” began as a scientific term, it has become associated with pathology, rather than identity, and is often used by hate groups. Also, do not assume sexual orientation based on a patient’s partner.

Always ask about sexual orientation before assuming it, and include that information in documentation. Dr. Khanijow used an example of a “one-liner” case of a 45-year-old male who self-identifies as “queer” and presents with a migraine. The most appropriate version would be “45yoM who identifies as queer with PMHx Migraines presents with Headache,” Dr. Khanijow said. However, as a clinician, consider why you are including sexual orientation in the one-liner. If there isn’t any real reason to include it (such as stress related to coming out, increased risk for other conditions) it may not be necessary in all visits.

Transgender considerations

Dr. Khanijow shared some specific considerations for the transgender/nonbinary population.

In terms of gender, “it is most respectful to identify the patient as they would like to be identified,” he said.

Ask how they identify their gender, including their preferred pronouns, and be sure to note this identification in their documents, he said. Be vigilant in addressing a transgender patient correctly. Mistakes happen, and when they do, correct yourself, apologize succinctly and move on.

Clinical challenges

Research on LGBTQ+ health is limited, and these individuals are often grouped into a single category despite diverse experiences, Dr. Rosendale said. Another limitation in LGBTQ+ research is that some studies assess based on identity (such as gay, lesbian, bisexual) while others assess behavior (studies of men who have sex with men).

Dr. Rosendale went on to highlight several important clinical concerns for the LGBTQ+ population. Compared with the general population, lesbian women are at higher risk for breast cancer, and gay men are at increased risk for prostate, colon, and testicular cancers. Potential heart disease risk factors of physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking are more prevalent among lesbian women, and tobacco and alcohol use are more prevalent among gay men, and men who have sex with men are at increased risk for STIs.

Clinicians also should be aware that “bisexual individuals face worse health outcomes than their lesbian, gay, and heterosexual counterparts,” Dr. Rosendale said.

LGBTQ+ patients often use hormone therapy, so clinicians should be aware of some potential adverse effects, Dr. Rosendale said. For example, trans women on gender-affirming estrogen therapy may have increased cardiovascular risks including incident MI, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular mortality, compared with cisgender women.

In trans men, testosterone use has not been definitively linked to cardiovascular risk, although patients may show small changes in systolic blood pressure, lipid profiles, and blood glucose, Dr. Rosendale noted.

In-hospital issues

Inpatient and critical care of transgender and LGBTQ+ patients may have unique psychosocial considerations in hospital care, Dr. Rosendale said. To provide some guidance, a document on “Transgender-Affirming Hospital Policies” has been developed jointly by Lamda Legal, the Human Rights Campaign, the law firm of Hogan Lovells, and the New York City Bar.

Best practices noted in the document include rooming transgender individuals according to their identity, and recognizing that these patients may experience additional stress while an inpatient if personal clothing or other means of gender expression are replaced during the hospital stay, Dr. Rosendale noted.

Finally, clinicians seeing LGBTQ+ patients in an acute care setting should keep in mind that socioeconomic disparities may limit access to outpatient care, and that this population has higher rates of unemployment, exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Rosendale said. In addition, she advised clinicians to be aware that LGBTQ+ people may experience discrimination in rehabilitation centers, and their surrogate decision makers may be individuals other than family members.

Dr. Khanijow and Dr. Rosendale had no financial conflicts to disclose.

More than 11 million individuals in the United States identify as LGBTQ+, and data show that this population has a shorter life expectancy and increased rates of suicide, violence, and cardiovascular disease, according to Keshav Khanijow, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and Nicole Rosendale, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

More than half of these individuals report experiencing discrimination, and one in three transgendered individuals have reported prejudice when visiting a doctor or health clinic, they said in a presentation at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“It is impossible to know how someone identifies by gender just by looking at them,” Dr. Rosendale emphasized.

However, attention to terminology, use of affirming language and documentation, and attention to clinical considerations can help LGBTQ+ patients feel comfortable in the health care setting.

Ask, don’t assume

Do ask patients how they identify themselves, Dr. Khanijow said. It is important to ask about sexual orientation as part of a social history. One big “Don’t” in terminology is to avoid the use of the term “homosexual,” he added. Although the description “homosexual” began as a scientific term, it has become associated with pathology, rather than identity, and is often used by hate groups. Also, do not assume sexual orientation based on a patient’s partner.

Always ask about sexual orientation before assuming it, and include that information in documentation. Dr. Khanijow used an example of a “one-liner” case of a 45-year-old male who self-identifies as “queer” and presents with a migraine. The most appropriate version would be “45yoM who identifies as queer with PMHx Migraines presents with Headache,” Dr. Khanijow said. However, as a clinician, consider why you are including sexual orientation in the one-liner. If there isn’t any real reason to include it (such as stress related to coming out, increased risk for other conditions) it may not be necessary in all visits.

Transgender considerations

Dr. Khanijow shared some specific considerations for the transgender/nonbinary population.

In terms of gender, “it is most respectful to identify the patient as they would like to be identified,” he said.

Ask how they identify their gender, including their preferred pronouns, and be sure to note this identification in their documents, he said. Be vigilant in addressing a transgender patient correctly. Mistakes happen, and when they do, correct yourself, apologize succinctly and move on.

Clinical challenges

Research on LGBTQ+ health is limited, and these individuals are often grouped into a single category despite diverse experiences, Dr. Rosendale said. Another limitation in LGBTQ+ research is that some studies assess based on identity (such as gay, lesbian, bisexual) while others assess behavior (studies of men who have sex with men).

Dr. Rosendale went on to highlight several important clinical concerns for the LGBTQ+ population. Compared with the general population, lesbian women are at higher risk for breast cancer, and gay men are at increased risk for prostate, colon, and testicular cancers. Potential heart disease risk factors of physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking are more prevalent among lesbian women, and tobacco and alcohol use are more prevalent among gay men, and men who have sex with men are at increased risk for STIs.

Clinicians also should be aware that “bisexual individuals face worse health outcomes than their lesbian, gay, and heterosexual counterparts,” Dr. Rosendale said.

LGBTQ+ patients often use hormone therapy, so clinicians should be aware of some potential adverse effects, Dr. Rosendale said. For example, trans women on gender-affirming estrogen therapy may have increased cardiovascular risks including incident MI, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular mortality, compared with cisgender women.

In trans men, testosterone use has not been definitively linked to cardiovascular risk, although patients may show small changes in systolic blood pressure, lipid profiles, and blood glucose, Dr. Rosendale noted.

In-hospital issues

Inpatient and critical care of transgender and LGBTQ+ patients may have unique psychosocial considerations in hospital care, Dr. Rosendale said. To provide some guidance, a document on “Transgender-Affirming Hospital Policies” has been developed jointly by Lamda Legal, the Human Rights Campaign, the law firm of Hogan Lovells, and the New York City Bar.

Best practices noted in the document include rooming transgender individuals according to their identity, and recognizing that these patients may experience additional stress while an inpatient if personal clothing or other means of gender expression are replaced during the hospital stay, Dr. Rosendale noted.

Finally, clinicians seeing LGBTQ+ patients in an acute care setting should keep in mind that socioeconomic disparities may limit access to outpatient care, and that this population has higher rates of unemployment, exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Rosendale said. In addition, she advised clinicians to be aware that LGBTQ+ people may experience discrimination in rehabilitation centers, and their surrogate decision makers may be individuals other than family members.

Dr. Khanijow and Dr. Rosendale had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Correlating hospitalist work schedules with patient outcomes

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Family-involved interventions reduce postoperative delirium

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Depression screening after ACS does not change outcomes

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Cardiac rehab after cardiac valve surgery associated with reduced mortality

Background: National guidelines recommend CR after CVS. However, neither enrollment in CR nor its benefits have been well described in this population.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Enrolled Medicare beneficiaries residing in the United States in 2014.

Synopsis: There were 41,369 Medicare patients who underwent CVS and met the study requirements; of these, 43.2% enrolled in CR programs. Those who had concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery or who resided in the Midwest region of the United States were more likely to enroll in CR. Asian, black, and Hispanic patients were less likely to enroll in CR. Enrollment in CR after CVS was associated with a decreased risk of 1-year hospitalization (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.69). CR utilization was also associated with a decrease in 1-year mortality after CVS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.35-0.44).

Enrollment rates in CR after CVS were lower than that of heart transplant patients, but higher than that for patients with systolic heart failure or after CABG. Major study limitations were the lack of generalizability to younger patients because all patients examined were older than 64 years.

Bottom line: Racial and geographic factors influence the rate of enrollment in CR for patients undergoing CVS. All patients should be encouraged to participate in CR after CVS because it is associated with reduced 1-year mortality and risk of hospitalization.

Citation: Patel DK et. al. Association of cardiac rehabilitation with decreased hospitalization and mortality risk after cardiac valve surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4032.

Dr. Babbel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: National guidelines recommend CR after CVS. However, neither enrollment in CR nor its benefits have been well described in this population.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Enrolled Medicare beneficiaries residing in the United States in 2014.

Synopsis: There were 41,369 Medicare patients who underwent CVS and met the study requirements; of these, 43.2% enrolled in CR programs. Those who had concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery or who resided in the Midwest region of the United States were more likely to enroll in CR. Asian, black, and Hispanic patients were less likely to enroll in CR. Enrollment in CR after CVS was associated with a decreased risk of 1-year hospitalization (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.69). CR utilization was also associated with a decrease in 1-year mortality after CVS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.35-0.44).

Enrollment rates in CR after CVS were lower than that of heart transplant patients, but higher than that for patients with systolic heart failure or after CABG. Major study limitations were the lack of generalizability to younger patients because all patients examined were older than 64 years.

Bottom line: Racial and geographic factors influence the rate of enrollment in CR for patients undergoing CVS. All patients should be encouraged to participate in CR after CVS because it is associated with reduced 1-year mortality and risk of hospitalization.

Citation: Patel DK et. al. Association of cardiac rehabilitation with decreased hospitalization and mortality risk after cardiac valve surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4032.

Dr. Babbel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: National guidelines recommend CR after CVS. However, neither enrollment in CR nor its benefits have been well described in this population.

Study design: Observational cohort study.

Setting: Enrolled Medicare beneficiaries residing in the United States in 2014.

Synopsis: There were 41,369 Medicare patients who underwent CVS and met the study requirements; of these, 43.2% enrolled in CR programs. Those who had concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery or who resided in the Midwest region of the United States were more likely to enroll in CR. Asian, black, and Hispanic patients were less likely to enroll in CR. Enrollment in CR after CVS was associated with a decreased risk of 1-year hospitalization (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.69). CR utilization was also associated with a decrease in 1-year mortality after CVS (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.35-0.44).

Enrollment rates in CR after CVS were lower than that of heart transplant patients, but higher than that for patients with systolic heart failure or after CABG. Major study limitations were the lack of generalizability to younger patients because all patients examined were older than 64 years.

Bottom line: Racial and geographic factors influence the rate of enrollment in CR for patients undergoing CVS. All patients should be encouraged to participate in CR after CVS because it is associated with reduced 1-year mortality and risk of hospitalization.

Citation: Patel DK et. al. Association of cardiac rehabilitation with decreased hospitalization and mortality risk after cardiac valve surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4032.

Dr. Babbel is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Virtual is the new real

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

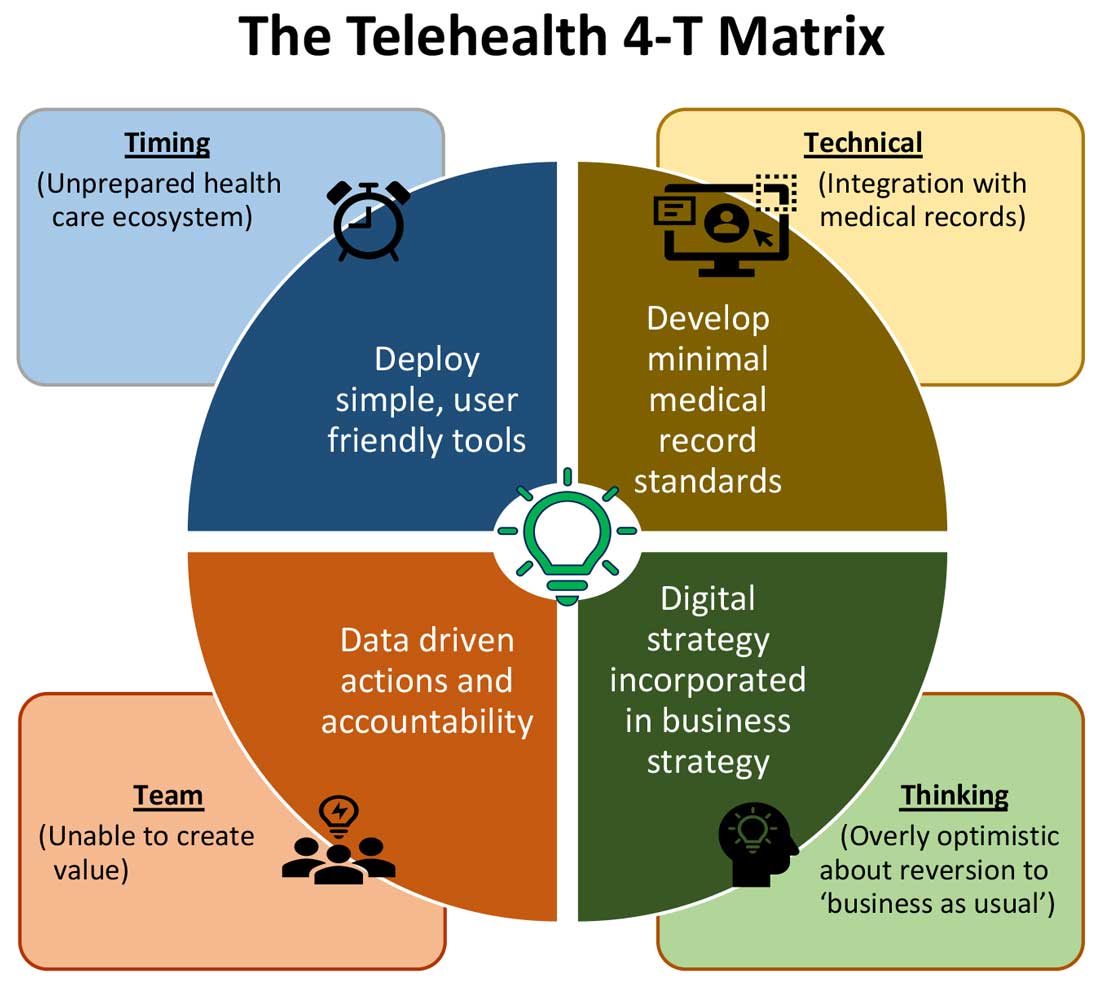

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking

In most U.S. hospitals, inpatient health care is equally distributed between nonprocedure and procedure-based services. Hospitals resorted to suspension of nonemergent procedures to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19. This was further compounded by many patients’ self-selection to defer care, an abrupt reduction in the influx of patients from the referral base because of suboptimally operating ambulatory care services, leading to low hospital occupancy.

Hospitals across the nation have gone through a massive short-term financial crunch and unfavorable cash-flow forecast, which prompted a paradoxical work-force reduction. While some argue that it may be akin to strategic myopia, the authors believed that such a response is strategically imperative to keep the hospital afloat. It is reasonable to attribute the paucity of innovation to constrained resources, and health systems are simply staying overly optimistic about “weathering the storm” and reverting soon to “business as usual.” The technological framework necessary for deploying a telehealth solution often comes with a price. Financially challenged hospital systems rarely exercise any capital-intensive activities. By contrast, telehealth adoption by ambulatory care can result in quicker resumption of patient care in community settings. A lack of operational and infrastructure synchrony between ambulatory and in-hospital systems has failed to capture telehealth-driven inpatient volume. For example, direct admissions from ambulatory telehealth referrals was a missed opportunity in several places. Referrals for labs, diagnostic tests, and other allied services could have helped hospitals offset their fixed costs. Similarly, work flows related to discharge and postdischarge follow up rarely embrace telehealth tools or telehealth care pathways. A brisk change in the health care ecosystem is partly responsible for this.

Digital strategy needs to be incorporated into business strategy. For the reasons already discussed, telehealth technology is not a “nice to have” anymore, but a “must have.” At present, providers are of the opinion that about 20% of their patient services can be delivered via a telehealth platform. Similar trends are observed among patients, as a new modality of access to care is increasingly beneficial to them. Telehealth must be incorporated in standardized hospital work flows. Use of telehealth for preoperative clearance will greatly minimize same-day surgery cancellations. Given the potential shortage in resources, telehealth adoption for inpatient consultations will help systems conserve personal protective equipment, minimize the risk of staff exposure to COVID-19, and improve efficiency.

Digital strategy also prompts the reengineering of care delivery.10 Excessive and unused physical capacity can be converted into digital care hubs. Health maintenance, prevention, health promotion, health education, and chronic disease management not only can serve a variety of patient groups but can also help address the “last-mile problem” in health care. A successful digital strategy usually has three important components – Commitment: Hospital leadership is committed to include digital transformation as a strategic objective; Cost: Digital strategy is added as a line item in the budget; and Control: Measurable metrics are put in place to monitor the performance, impact, and influence of the digital strategy.

Conclusion

For decades, most U.S. health systems occupied the periphery of technological transformation when compared to the rest of the service industry. While most health systems took a heroic approach to the adoption of telehealth during COVID-19, despite being unprepared, the need for a systematic telehealth deployment is far from being adequately fulfilled. The COVID-19 pandemic brought permanent changes to several business disciplines globally. Given the impact of the pandemic on the health and overall wellbeing of American society, the U.S. health care industry must leave no stone unturned in its quest for transformation.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark, and is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Prasad is medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management, and physician advisory services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi, both in Jackson.

References

1. Finnegan M. “Telehealth booms amid COVID-19 crisis.” Computerworld. 2020 Apr 27. www.computerworld.com/article/3540315/telehealth-booms-amid-covid-19-crisis-virtual-care-is-here-to-stay.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

2. Department of Health & Human Services. “OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency.” 2020 Mar 17. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. “Health Expenditures.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

4. Bestsennyy O et al. “Telehealth: A post–COVID-19 reality?” McKinsey & Company. 2020 May 29. www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

5. Melnick ER et al. The Association Between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout Among U.S. Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 March;95(3):476-87.

6. Hirko KA et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Nov;27(11):1816-8. .

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. “Study Examines Telehealth, Rural Disparities in Pandemic.” 2020 July 30. www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20200730ruraltelehealth.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 15.

8. Kurlander J et al. “Virtual Visits: Telehealth and Older Adults.” National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2019 Oct. hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151376.

9. American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2019. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf.

10. Smith AC et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020 Jun;26(5):309-13.

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

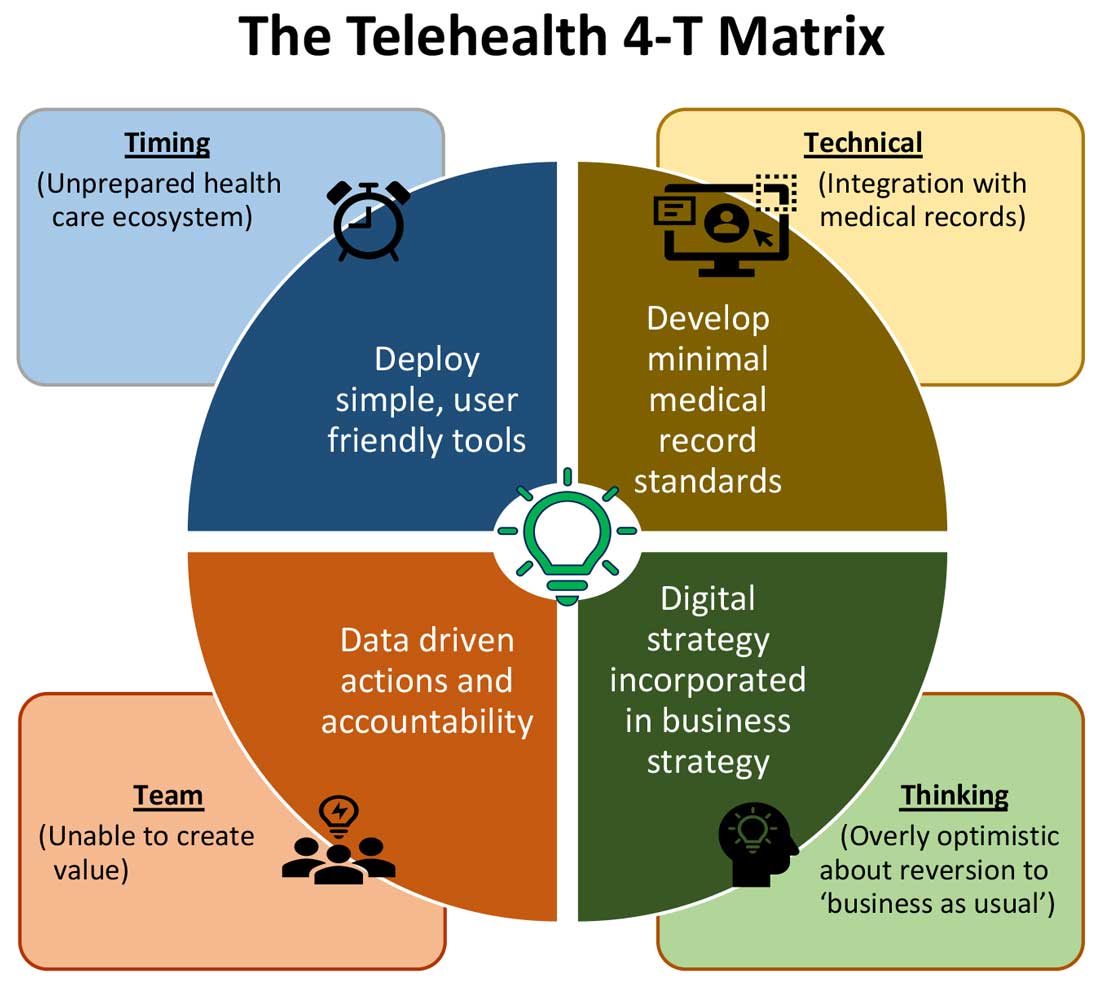

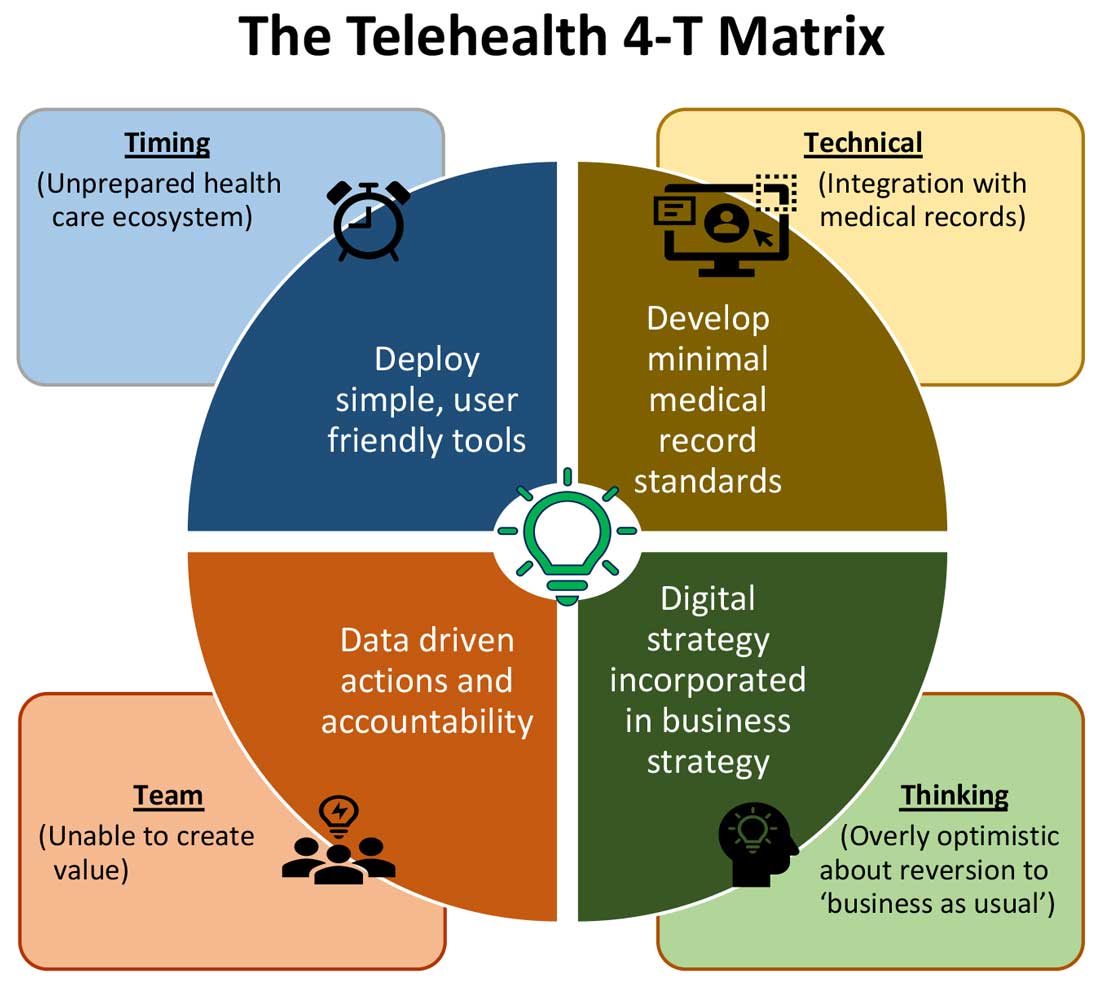

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.