User login

The Hospitalist only

How To Avoid Medicare Denials for Critical-Care Billing

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

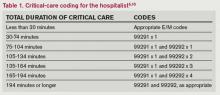

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Feds Extend HIPAA Obligations, Violation Penalties

On Jan. 17, 2013, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an omnibus Final Rule implementing various provisions of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, or HITECH, Act. The Final Rule revises the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the interim final Breach Notification Rule.

The HITECH Act, which took effect as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, expanded the obligations of covered entities and business associates to protect the confidentiality and security of protected health information (PHI).

Under HIPAA, “covered entities” may disclose PHI to “business associates,” and permit business associates to create and receive PHI on behalf of the covered entity, subject to the terms of a business-associate agreement between the parties. A “covered entity” is defined as a health plan, healthcare clearinghouse, or healthcare provider (e.g. physician practice or hospital) that transmits health information electronically. In general, the HIPAA regulations have traditionally defined a “business associate” as a person (other than a member of the covered entity’s workforce) or entity who, on behalf of a covered entity, performs a function or activity involving the use or disclosure of PHI, such as the performance of financial, legal, actuarial, accounting, consulting, data aggregation, management, administrative, or accreditation services to or for a covered entity.

Prior to the HITECH Act, business associates were contractually obligated to maintain the privacy and security of PHI but could not be sanctioned for failing to comply with HIPAA. The HITECH Act expands those obligations and exposure of business associates by:

- Applying many of the privacy and security standards to business associates;

- Subjecting business associates to the breach-notification requirements; and

- Imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations.

In addition, the HITECH Act strengthened the penalties and enforcement mechanisms under HIPAA and required periodic audits to ensure that covered entities and business associates are compliant.

Expansion of Breach-Notification Requirements

The Final Rule expands the breach-notification obligations of covered entities and business associates by revising the definition of “breach” and the risk-assessment process for determining whether notification is required. A use or disclosure of unsecured PHI that is not permitted under the Privacy Rule is presumed to be a breach (and therefore requires notification to the individual, OCR, and possibly the media) unless the incident satisfies an exception, or the covered entity or business associate demonstrates a low probability that PHI has been compromised.1 This risk analysis is based on at least the following four factors:

- The nature and extent of the PHI, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

- The unauthorized person who used or accessed the PHI;

- Whether the PHI was actually acquired or viewed; and

- The extent to which the risk is mitigated (e.g. by obtaining reliable assurances by a recipient of PHI that the information will be destroyed or will not be used or disclosed).

Expansion of Business-Associate Obligations

The Final Rule implements the HITECH Act’s expansion of business associates’ HIPAA obligations by applying the Privacy and Security Rules directly to business associates and by imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations. It also extends obligations and potential penalties to subcontractors of business associates if a business associate delegates a function, activity, or service to the subcontractor, and the subcontractor creates, receives, maintains, or transmits PHI on behalf of the business associate. Any business associate that delegates a function involving the use or disclosure of PHI to a subcontractor will be required to enter into a business-associate agreement with the subcontractor.

Additional Provisions

The Final Rule addresses the following additional issues by:

- Requiring covered entities to modify their Notices of Privacy Practices;

- Allowing individuals to obtain a copy of PHI in an electronic format if the covered entity uses an electronic health record;

- Restricting marketing activities;

- Allowing covered entities to disclose relevant PHI of a deceased person to a family member, close friend, or other person designated by the deceased, unless the disclosure is inconsistent with the deceased person’s known prior expressed preference;

- Requiring covered entities to agree to an individual’s request to restrict disclosure of PHI to a health plan when the individual (or someone other than the health plan) pays for the healthcare item or service in full;

- Revising the definition of PHI to exclude information about a person who has been deceased for more than 50 years;

- Prohibiting the sale of PHI without authorization from the individual, and adding a requirement of authorization in order for a covered entity to receive remuneration for disclosing PHI;

- Clarifying OCR’s view that covered entities are allowed to send electronic PHI to individuals in unencrypted e-mails only after notifying the individual of the risk;

- Prohibiting health plans from using or disclosing genetic information for underwriting, as required by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA);

- Allowing disclosure of proof of immunization to schools if agreed by the parent, guardian, or individual;

- Permitting compound authorizations for clinical-research studies; and

- Revising the Enforcement Rule (which was previously revised in 2009 as an interim Final Rule), which:

- Requires the secretary of HHS to investigate a HIPAA complaint if a preliminary investigation indicates a possible violation due to willful neglect;

- Permits HHS to disclose PHI to other government agencies (including state attorneys general) for civil or criminal law-enforcement purposes; and

- Revises standards for determining the levels of civil money penalties.

Effective Date, Compliance Date

Although most provisions of the Final Rule became effective on March 26, many provisions impacting covered entities and business associates (including subcontractors) required compliance by Sept. 23. However, if certain conditions are met, the Final Rule allows additional time to revise business associate agreements to make them compliant. In particular, transition provisions will allow covered entities and business associates to continue to operate under existing business-associate agreements for up to one year beyond the compliance date (until Sept. 22, 2014) if the business-associate agreement:

- Is in writing;

- Is in place prior to Jan. 25, 2013 (the publication date of the Final Rule);

- Is compliant with the Privacy and Security Rules, in effect immediately prior to Jan. 25, 2013; and

- Is not modified or renewed.

This additional time for grandfathered business-associate agreements applies only to the written-documentation requirement. Covered entities, business associates and subcontractors will be required to comply with all other HIPAA requirements beginning on the compliance date, even if the business-associate agreement qualifies for grandfathered status

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at sharris@mcdonaldhopkins.com.

Footnote

The exceptions relate to (i) unintentional, good-faith access, acquisition or use by members of the covered entity’s or business associate’s workforce, (ii) inadvertent disclosure limited to persons with authorized access and not resulting in further unpermitted use or disclosure, and (iii) good-faith belief that the unauthorized recipient would be unable to retain the PHI.

On Jan. 17, 2013, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an omnibus Final Rule implementing various provisions of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, or HITECH, Act. The Final Rule revises the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the interim final Breach Notification Rule.

The HITECH Act, which took effect as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, expanded the obligations of covered entities and business associates to protect the confidentiality and security of protected health information (PHI).

Under HIPAA, “covered entities” may disclose PHI to “business associates,” and permit business associates to create and receive PHI on behalf of the covered entity, subject to the terms of a business-associate agreement between the parties. A “covered entity” is defined as a health plan, healthcare clearinghouse, or healthcare provider (e.g. physician practice or hospital) that transmits health information electronically. In general, the HIPAA regulations have traditionally defined a “business associate” as a person (other than a member of the covered entity’s workforce) or entity who, on behalf of a covered entity, performs a function or activity involving the use or disclosure of PHI, such as the performance of financial, legal, actuarial, accounting, consulting, data aggregation, management, administrative, or accreditation services to or for a covered entity.

Prior to the HITECH Act, business associates were contractually obligated to maintain the privacy and security of PHI but could not be sanctioned for failing to comply with HIPAA. The HITECH Act expands those obligations and exposure of business associates by:

- Applying many of the privacy and security standards to business associates;

- Subjecting business associates to the breach-notification requirements; and

- Imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations.

In addition, the HITECH Act strengthened the penalties and enforcement mechanisms under HIPAA and required periodic audits to ensure that covered entities and business associates are compliant.

Expansion of Breach-Notification Requirements

The Final Rule expands the breach-notification obligations of covered entities and business associates by revising the definition of “breach” and the risk-assessment process for determining whether notification is required. A use or disclosure of unsecured PHI that is not permitted under the Privacy Rule is presumed to be a breach (and therefore requires notification to the individual, OCR, and possibly the media) unless the incident satisfies an exception, or the covered entity or business associate demonstrates a low probability that PHI has been compromised.1 This risk analysis is based on at least the following four factors:

- The nature and extent of the PHI, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

- The unauthorized person who used or accessed the PHI;

- Whether the PHI was actually acquired or viewed; and

- The extent to which the risk is mitigated (e.g. by obtaining reliable assurances by a recipient of PHI that the information will be destroyed or will not be used or disclosed).

Expansion of Business-Associate Obligations

The Final Rule implements the HITECH Act’s expansion of business associates’ HIPAA obligations by applying the Privacy and Security Rules directly to business associates and by imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations. It also extends obligations and potential penalties to subcontractors of business associates if a business associate delegates a function, activity, or service to the subcontractor, and the subcontractor creates, receives, maintains, or transmits PHI on behalf of the business associate. Any business associate that delegates a function involving the use or disclosure of PHI to a subcontractor will be required to enter into a business-associate agreement with the subcontractor.

Additional Provisions

The Final Rule addresses the following additional issues by:

- Requiring covered entities to modify their Notices of Privacy Practices;

- Allowing individuals to obtain a copy of PHI in an electronic format if the covered entity uses an electronic health record;

- Restricting marketing activities;

- Allowing covered entities to disclose relevant PHI of a deceased person to a family member, close friend, or other person designated by the deceased, unless the disclosure is inconsistent with the deceased person’s known prior expressed preference;

- Requiring covered entities to agree to an individual’s request to restrict disclosure of PHI to a health plan when the individual (or someone other than the health plan) pays for the healthcare item or service in full;

- Revising the definition of PHI to exclude information about a person who has been deceased for more than 50 years;

- Prohibiting the sale of PHI without authorization from the individual, and adding a requirement of authorization in order for a covered entity to receive remuneration for disclosing PHI;

- Clarifying OCR’s view that covered entities are allowed to send electronic PHI to individuals in unencrypted e-mails only after notifying the individual of the risk;

- Prohibiting health plans from using or disclosing genetic information for underwriting, as required by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA);

- Allowing disclosure of proof of immunization to schools if agreed by the parent, guardian, or individual;

- Permitting compound authorizations for clinical-research studies; and

- Revising the Enforcement Rule (which was previously revised in 2009 as an interim Final Rule), which:

- Requires the secretary of HHS to investigate a HIPAA complaint if a preliminary investigation indicates a possible violation due to willful neglect;

- Permits HHS to disclose PHI to other government agencies (including state attorneys general) for civil or criminal law-enforcement purposes; and

- Revises standards for determining the levels of civil money penalties.

Effective Date, Compliance Date

Although most provisions of the Final Rule became effective on March 26, many provisions impacting covered entities and business associates (including subcontractors) required compliance by Sept. 23. However, if certain conditions are met, the Final Rule allows additional time to revise business associate agreements to make them compliant. In particular, transition provisions will allow covered entities and business associates to continue to operate under existing business-associate agreements for up to one year beyond the compliance date (until Sept. 22, 2014) if the business-associate agreement:

- Is in writing;

- Is in place prior to Jan. 25, 2013 (the publication date of the Final Rule);

- Is compliant with the Privacy and Security Rules, in effect immediately prior to Jan. 25, 2013; and

- Is not modified or renewed.

This additional time for grandfathered business-associate agreements applies only to the written-documentation requirement. Covered entities, business associates and subcontractors will be required to comply with all other HIPAA requirements beginning on the compliance date, even if the business-associate agreement qualifies for grandfathered status

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at sharris@mcdonaldhopkins.com.

Footnote

The exceptions relate to (i) unintentional, good-faith access, acquisition or use by members of the covered entity’s or business associate’s workforce, (ii) inadvertent disclosure limited to persons with authorized access and not resulting in further unpermitted use or disclosure, and (iii) good-faith belief that the unauthorized recipient would be unable to retain the PHI.

On Jan. 17, 2013, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an omnibus Final Rule implementing various provisions of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, or HITECH, Act. The Final Rule revises the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the interim final Breach Notification Rule.

The HITECH Act, which took effect as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, expanded the obligations of covered entities and business associates to protect the confidentiality and security of protected health information (PHI).

Under HIPAA, “covered entities” may disclose PHI to “business associates,” and permit business associates to create and receive PHI on behalf of the covered entity, subject to the terms of a business-associate agreement between the parties. A “covered entity” is defined as a health plan, healthcare clearinghouse, or healthcare provider (e.g. physician practice or hospital) that transmits health information electronically. In general, the HIPAA regulations have traditionally defined a “business associate” as a person (other than a member of the covered entity’s workforce) or entity who, on behalf of a covered entity, performs a function or activity involving the use or disclosure of PHI, such as the performance of financial, legal, actuarial, accounting, consulting, data aggregation, management, administrative, or accreditation services to or for a covered entity.

Prior to the HITECH Act, business associates were contractually obligated to maintain the privacy and security of PHI but could not be sanctioned for failing to comply with HIPAA. The HITECH Act expands those obligations and exposure of business associates by:

- Applying many of the privacy and security standards to business associates;

- Subjecting business associates to the breach-notification requirements; and

- Imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations.

In addition, the HITECH Act strengthened the penalties and enforcement mechanisms under HIPAA and required periodic audits to ensure that covered entities and business associates are compliant.

Expansion of Breach-Notification Requirements

The Final Rule expands the breach-notification obligations of covered entities and business associates by revising the definition of “breach” and the risk-assessment process for determining whether notification is required. A use or disclosure of unsecured PHI that is not permitted under the Privacy Rule is presumed to be a breach (and therefore requires notification to the individual, OCR, and possibly the media) unless the incident satisfies an exception, or the covered entity or business associate demonstrates a low probability that PHI has been compromised.1 This risk analysis is based on at least the following four factors:

- The nature and extent of the PHI, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

- The unauthorized person who used or accessed the PHI;

- Whether the PHI was actually acquired or viewed; and

- The extent to which the risk is mitigated (e.g. by obtaining reliable assurances by a recipient of PHI that the information will be destroyed or will not be used or disclosed).

Expansion of Business-Associate Obligations

The Final Rule implements the HITECH Act’s expansion of business associates’ HIPAA obligations by applying the Privacy and Security Rules directly to business associates and by imposing civil and criminal penalties on business associates for HIPAA violations. It also extends obligations and potential penalties to subcontractors of business associates if a business associate delegates a function, activity, or service to the subcontractor, and the subcontractor creates, receives, maintains, or transmits PHI on behalf of the business associate. Any business associate that delegates a function involving the use or disclosure of PHI to a subcontractor will be required to enter into a business-associate agreement with the subcontractor.

Additional Provisions

The Final Rule addresses the following additional issues by:

- Requiring covered entities to modify their Notices of Privacy Practices;

- Allowing individuals to obtain a copy of PHI in an electronic format if the covered entity uses an electronic health record;

- Restricting marketing activities;

- Allowing covered entities to disclose relevant PHI of a deceased person to a family member, close friend, or other person designated by the deceased, unless the disclosure is inconsistent with the deceased person’s known prior expressed preference;

- Requiring covered entities to agree to an individual’s request to restrict disclosure of PHI to a health plan when the individual (or someone other than the health plan) pays for the healthcare item or service in full;

- Revising the definition of PHI to exclude information about a person who has been deceased for more than 50 years;

- Prohibiting the sale of PHI without authorization from the individual, and adding a requirement of authorization in order for a covered entity to receive remuneration for disclosing PHI;

- Clarifying OCR’s view that covered entities are allowed to send electronic PHI to individuals in unencrypted e-mails only after notifying the individual of the risk;

- Prohibiting health plans from using or disclosing genetic information for underwriting, as required by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA);

- Allowing disclosure of proof of immunization to schools if agreed by the parent, guardian, or individual;

- Permitting compound authorizations for clinical-research studies; and

- Revising the Enforcement Rule (which was previously revised in 2009 as an interim Final Rule), which:

- Requires the secretary of HHS to investigate a HIPAA complaint if a preliminary investigation indicates a possible violation due to willful neglect;

- Permits HHS to disclose PHI to other government agencies (including state attorneys general) for civil or criminal law-enforcement purposes; and

- Revises standards for determining the levels of civil money penalties.

Effective Date, Compliance Date

Although most provisions of the Final Rule became effective on March 26, many provisions impacting covered entities and business associates (including subcontractors) required compliance by Sept. 23. However, if certain conditions are met, the Final Rule allows additional time to revise business associate agreements to make them compliant. In particular, transition provisions will allow covered entities and business associates to continue to operate under existing business-associate agreements for up to one year beyond the compliance date (until Sept. 22, 2014) if the business-associate agreement:

- Is in writing;

- Is in place prior to Jan. 25, 2013 (the publication date of the Final Rule);

- Is compliant with the Privacy and Security Rules, in effect immediately prior to Jan. 25, 2013; and

- Is not modified or renewed.

This additional time for grandfathered business-associate agreements applies only to the written-documentation requirement. Covered entities, business associates and subcontractors will be required to comply with all other HIPAA requirements beginning on the compliance date, even if the business-associate agreement qualifies for grandfathered status

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at sharris@mcdonaldhopkins.com.

Footnote

The exceptions relate to (i) unintentional, good-faith access, acquisition or use by members of the covered entity’s or business associate’s workforce, (ii) inadvertent disclosure limited to persons with authorized access and not resulting in further unpermitted use or disclosure, and (iii) good-faith belief that the unauthorized recipient would be unable to retain the PHI.

Hospitalist Compensation Models Evolve Toward Production, Performance-Based Variables

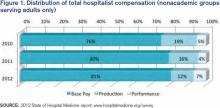

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

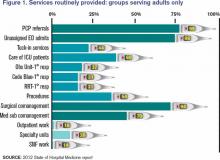

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalist Groups Extract New Solutions Via Data Mining

One hospital wanted to reduce readmissions among patients with congestive heart failure. Another hoped to improve upon its sepsis mortality rates. A third sought to determine whether its doctors were providing cost-effective care for pneumonia patients. All of them adopted the same type of technology to help identify a solution.

As the healthcare industry tilts toward accountable care, pay for performance and an increasingly

cost-conscious mindset, hospitalists and other providers are tapping into a fast-growing analytical tool collectively known as data mining to help make sense of the growing mounds of information. Although no single technology can be considered a cure-all, HM leaders are so optimistic about data mining’s potential to address cost, outcome, and performance issues that some have labeled it a “game changer” for hospitalists.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer at North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, Ga., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, says he can’t overstate the importance of hospitalists’ involvement in physician data mining. “From my perspective, we’re looking to hospitalists to help drive this quality-utilization bandwagon, to be the real leaders in it,” he says. With the tremendous value that can be generated through understanding and using the information, “it’s good for your group and can be good to your hospital as a whole.”

So what is data mining? The technology fully emerged in the mid-1990s as a way to help scientists analyze large and often disparate bodies of data, present relevant information in new ways, and illuminate previously unknown relationships.1 In the healthcare industry, early adopters realized that the insights gleaned from data mining could help inform their clinical decision-making; organizations used the new tools to help predict health insurance fraud and identify at-risk patients, for example.

Cynthia Burghard, research director of Accountable Care IT Strategies at IDC Health Insights in Framingham, Mass., says researchers in academic medical centers initially conducted most of the clinical analytical work. Within the past few years, however, the increasing availability of data has allowed more hospitals to begin analyzing chronic disease, readmissions, and other areas of concern. In addition, Burghard says, new tools based on natural language processing are giving hospitals better access to unstructured clinical data, such as notes written by doctors and nurses.

“What I’m seeing both in my surveys as well as in conversations with hospitals is that analytics is the top of the investment priority for both hospitals and health plans,” Burghard says. According to IDC estimates, total spending for clinical analytics in the U.S. reached $3.7 billion in 2012 and is expected to grow to $5.14 billion by 2016. Much of the growth, she notes, is being driven by healthcare reform. “If your mandate is to manage populations of patients, it behooves you to know who those patients are and what their illnesses are, and to monitor what you’re doing for them,” she says.

Practice Improvement

Accordingly, a major goal of all this data-mining technology is to change practice behavior in a way that achieves the triple aim of improving quality of care, controlling costs, and bettering patient outcomes.

A growing number of companies are releasing tools that can compile and analyze the separate bits of information captured from claims and billing systems, Medicare reporting requirements, internal benchmarks, and other sources. Unlike passive data sources, such as Medicare’s Hospital Compare website, more active analytics can help their users zoom down to the level of an individual doctor or patient, pan out to the level of a hospitalist group, or expand out even more for a broader comparison among peer institutions.

Some newer data-mining tools with names like CRIMSON, Truven, Iodine, and Imagine are billing themselves as hospitalist-friendly performance-improvement aids and giving individual providers the ability to access and analyze the data themselves. A few of these applications can even provide real-time data via mobile devices (see “Physician Performance Aids,”).

Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the HM service at Alegent Creighton Health in Omaha, Neb., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, sees the biggest potential of this data-mining technology in its ability to help drive practice consistency. “You can use the database to analyze practice patterns of large groups, or even individuals, and see where variability exists,” he says. “And then, based on that, you can analyze why the variability exists and begin to address whether it’s variability that’s clinically indicated or not.”

When Alegent Creighton Health was scrutinizing the care of its pneumonia patients, for example, officials could compare the number of chest X-rays per pneumonia patient by hospital or across the entire CRIMSON database. At a deeper level, the officials could see how often individual providers ordered the tests compared to their peers. For outliers, they could follow up to determine whether the variability was warranted.

As champions of process improvement, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists can make particularly good use of database analytics. “It’s part of the process of making hospitalists invaluable to their hospitals and their systems,” he says. “Part of that is building up expertise on process improvement and safety, and familiarity with these kinds of tools is one thing that will help us do that.”

North Fulton Hospital used CRIMSON to analyze how its doctors care for patients with sepsis and to establish new benchmarks. Dr. Godamunne says the tools allowed the hospital to track its doctors’ progress over time and identify potential problems. “If a patient with sepsis is staying too long, you can see who admitted the patient and see if, a few months ago, the same physician was having similar problems,” he says. Similarly, the hospital was able to track the top DRGs resulting in excess length of stay among patients, to identify potential bottlenecks in the care and discharge processes.

Some tools require only two-day training sessions for basic proficiency, though more advanced manipulations often require a bigger commitment, like the 12-week training session that Dr. Godamunne completed. That training included one hour of online learning and one hour of homework every week, and most of the cases highlighted during his coursework, he says, focused on hospitalists—another sign of the major role he believes HM will play in harnessing data to improve performance quality.

—Thomas Frederickson, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, hospital medicine service, Alegent Creighton Health, Omaha, Neb., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Slow—Construction Ahead

The best information is meaningful, individualized, and timely, says Steven Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM, system chairman for hospital medicine and medical director of regional business development at Ochsner Health System in New Orleans. “If you get something back six months after you’ve delivered the care, you’ll have a limited opportunity to improve, versus if you get it back in a week or two, or ideally, in real time,” says Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Management Committee.

In examining length of stay, Dr. Deitelzweig says doctors could use data mining to look at time-stamped elements of patient flow and the timeliness of provider response: how patients go through the ED, and when they receive written orders or lab results. “It could be really powerful, and right now it’s a little bit of a black hole,” he says.

Based on her conversations with hospital executives and leaders, however, Burghard cautions that some real-time mobile applications, although technologically impressive, may be less useful or necessary in practice. “If it’s performance measurement, why do you need that in real time? It’s not going to change your behavior in the moment,” she says. “What you may want to get is an alert that your patient, who is in the hospital, has had some sort of negative event.”

Data mining has other potential limitations. “There’s always going to be questions of attribution, and you need to have clinical knowledge of your location,” Dr. Godamunne says. And data mining is only as good as the data that have been documented, underscoring the importance of securing provider cooperation.

Dr. Frederickson says physician acceptance, in fact, might be one of the biggest obstacles—a major reason why he recommends introducing the technology slowly and explaining why and how it will be used. If introduced too quickly and without adequate explanation about what a hospital or health system hopes to accomplish, he says, “there certainly is the potential for suspicion.” The key, he says, is to emphasize that the tools provide a valuable mechanism for gleaning new insights into doctors’ practice patterns, “not something that’s going to be used against them.”

Paul Roscoe, CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Advisory Board Company's Crimson division, agrees that personally engaging physicians is essential for a good return on investment in analytical tools like his company’s suite of CRIMSON products. “If you can’t work with the physicians to get them to understand the data and actively use the data in their practice patterns, it becomes a bit meaningless,” he says.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer, North Fulton Hospital, Roswell, Ga., SHM Practice Management Committee member

Roscoe sees big opportunities in prospectively examining information while a patient is still in the hospital and when a change of course by providers could avert a bad outcome. “Suggesting a set of interventions that they could do differently is really the value-add,” he says. But he cautions that those suggestions must be worded carefully to avoid alienating physicians.

“If doctors don’t feel like they’re being judged, they’ll engage with you,” Roscoe says.

Similar nuances can affect how users perceive the tools themselves. After hearing feedback from members that the words “data mining” didn’t conjure trust and confidence, the Advisory Board Company dropped the phrase altogether in favor of “data analytics,” “physician engagement,” and similar descriptors. “It’s simple things like that that can very quickly either turn a physician on or off,” Roscoe says.

Once users take the time to understand data-mining tools and how they can be properly harnessed, advocates say, the technology can lead to a host of unanticipated benefits. When a hospital bills the federal government for a Medicare patient, for example, it must submit an HCC code that describes the patient’s condition. By doing a better job of mining the data, Burghard says, a hospital can more accurately reflect that patient’s contdition. For example, if a hospital is treating a diabetic who comes in with a broken leg, the hospital could receive a lower payment rate if it does not properly identify and record both conditions.

And by using the tools prospectively, Burghard says, “I think there’s the opportunity to make a quantum leap from what we’re doing today. We usually just report on facts, and usually retrospectively. With some of the new technology that’s available, the healthcare industry can begin to do discovery analytics—you’re identifying insights, patterns, and relationships.”

Better integration of computerized physician order entry with data-mining ports, Dr. Godamunne predicts, will allow for much better attribution and finer parsing of the data. As the transparency increases, though, hospitalists will have to adapt to a new reality in which stronger analytical tools may point out individual outliers. And that level of detail, in turn, will require some hospitalists to justify why they’re different than their peers.

Even so, Roscoe says, he’s found that hospitalists are very open to using data to improve performance and that they make up a high percentage of CRIMSON users. “There isn’t a physician group that is in a better position to help drive this quality- and data-driven culture,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Reference

One hospital wanted to reduce readmissions among patients with congestive heart failure. Another hoped to improve upon its sepsis mortality rates. A third sought to determine whether its doctors were providing cost-effective care for pneumonia patients. All of them adopted the same type of technology to help identify a solution.

As the healthcare industry tilts toward accountable care, pay for performance and an increasingly

cost-conscious mindset, hospitalists and other providers are tapping into a fast-growing analytical tool collectively known as data mining to help make sense of the growing mounds of information. Although no single technology can be considered a cure-all, HM leaders are so optimistic about data mining’s potential to address cost, outcome, and performance issues that some have labeled it a “game changer” for hospitalists.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, chief medical officer at North Fulton Hospital in Roswell, Ga., and a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee, says he can’t overstate the importance of hospitalists’ involvement in physician data mining. “From my perspective, we’re looking to hospitalists to help drive this quality-utilization bandwagon, to be the real leaders in it,” he says. With the tremendous value that can be generated through understanding and using the information, “it’s good for your group and can be good to your hospital as a whole.”

So what is data mining? The technology fully emerged in the mid-1990s as a way to help scientists analyze large and often disparate bodies of data, present relevant information in new ways, and illuminate previously unknown relationships.1 In the healthcare industry, early adopters realized that the insights gleaned from data mining could help inform their clinical decision-making; organizations used the new tools to help predict health insurance fraud and identify at-risk patients, for example.

Cynthia Burghard, research director of Accountable Care IT Strategies at IDC Health Insights in Framingham, Mass., says researchers in academic medical centers initially conducted most of the clinical analytical work. Within the past few years, however, the increasing availability of data has allowed more hospitals to begin analyzing chronic disease, readmissions, and other areas of concern. In addition, Burghard says, new tools based on natural language processing are giving hospitals better access to unstructured clinical data, such as notes written by doctors and nurses.

“What I’m seeing both in my surveys as well as in conversations with hospitals is that analytics is the top of the investment priority for both hospitals and health plans,” Burghard says. According to IDC estimates, total spending for clinical analytics in the U.S. reached $3.7 billion in 2012 and is expected to grow to $5.14 billion by 2016. Much of the growth, she notes, is being driven by healthcare reform. “If your mandate is to manage populations of patients, it behooves you to know who those patients are and what their illnesses are, and to monitor what you’re doing for them,” she says.

Practice Improvement