User login

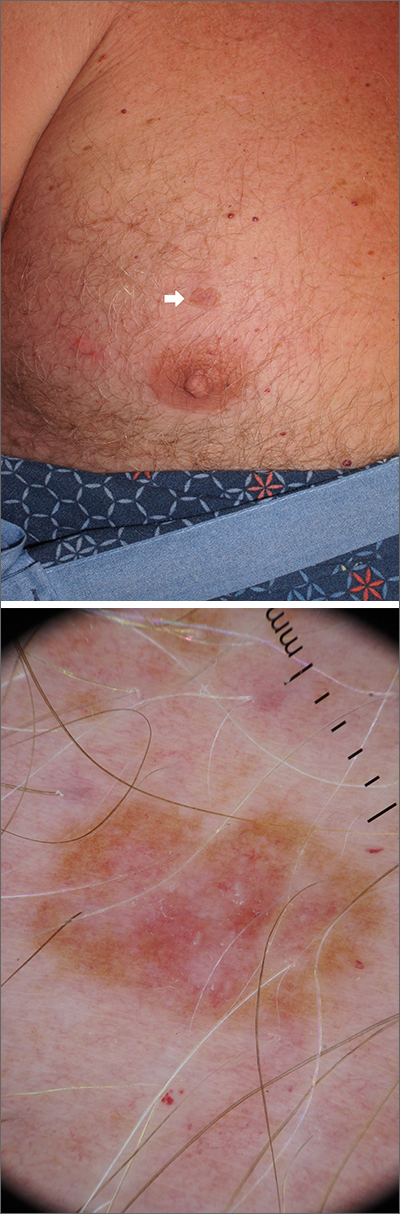

Rash and edema

Lab work was ordered and came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Patients also often have associated facial or acral edema (72%).1 Children with significant edema of the feet may find walking difficult, which should not be confused with arthritis or arthralgias.

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing. When performed, laboratory studies—including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis—are routinely normal. The differential diagnosis in this case included erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis.1,2,4

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved, and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

This case was adapted from: Cook JS, Angles A, Morley E. Urticaria and edema in a 2-year-old boy. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:353-355.

Photos courtesy of Jeffrey S. Cook, MD, FAAFP

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

Lab work was ordered and came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Patients also often have associated facial or acral edema (72%).1 Children with significant edema of the feet may find walking difficult, which should not be confused with arthritis or arthralgias.

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing. When performed, laboratory studies—including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis—are routinely normal. The differential diagnosis in this case included erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis.1,2,4

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved, and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

This case was adapted from: Cook JS, Angles A, Morley E. Urticaria and edema in a 2-year-old boy. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:353-355.

Photos courtesy of Jeffrey S. Cook, MD, FAAFP

Lab work was ordered and came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Patients also often have associated facial or acral edema (72%).1 Children with significant edema of the feet may find walking difficult, which should not be confused with arthritis or arthralgias.

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing. When performed, laboratory studies—including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis—are routinely normal. The differential diagnosis in this case included erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis.1,2,4

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved, and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

This case was adapted from: Cook JS, Angles A, Morley E. Urticaria and edema in a 2-year-old boy. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:353-355.

Photos courtesy of Jeffrey S. Cook, MD, FAAFP

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

Blisters on arms and legs

This patient was given a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Although there were a number of clues that pointed to this diagnosis, confirming that this was the case required 2 biopsies and a blood draw. (More on this in a bit.)

Although rare and potentially lethal, bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Patients present with tense bullae over limited or widespread areas of the skin. The pathogenesis includes development of autoimmune antibodies that target important proteins (BP180 and BP230) that bind basal epidermal keratinocytes to the dermis. When weakened by inflammation at these sites, the skin delaminates at the dermal-epidermal junction, while the cells of the epidermis continue to bind to each other. This leads to itching, hive-like wheals, and tense fluid-filled bullae.

The differential diagnosis of an acute or semi-acute bullous disease includes bullous pemphigoid, IgA pemphigoid, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and Senear-Usher syndrome. In this case, the large tense bullae suggested bullous pemphigoid over the other diagnoses.

Initial diagnosis requires 2 biopsies be performed: One at the edge of a bulla for a standard pathologic exam to identify the skin level at which the bulla is forming, and another biopsy of skin near the site of inflammation (5-10 mm away) to be sent for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) in Michel’s medium or Zeus medium. In bullous pemphigoid, the separation is at the dermal-epidermal junction, and IgG and C3 are found in the DIF in the same location. There are a couple ways to differentiate this disorder from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—a similar blistering disorder in which autoantibodies attack collagen at the dermal-epidermal junction. A common approach is to send a patient’s serum for indirect immunofluorescence. This is done because it is impossible to distinguish between the 2 clinically.

While bullous pemphigoid has historically been treated with high-dose prednisone, it is more common now to treat with whole-body topical clobetasol and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day to avoid the adverse effects of the prednisone. Other immunosuppressive options, such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine, can provide the potency of prednisone with a more favorable long-term safety profile. Rituximab infusions are another very powerful and durable option in refractory or severe cases.1

This patient was treated with topical clobetasol and doxycycline 100 mg twice a day, but he had incomplete clearance after 2 to 3 weeks. At that point, mycophenolate mofetil was added to the regimen and was titrated up to 1000 mg twice daily. When clearance occurred, the clobetasol was discontinued and the mycophenolate mofetil was titrated down to 250 mg/d; the patient continues to maintain clearance at this dose. He continues on doxycycline 100 mg bid.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Ruggiero A, Megna M, Villani A, et al. Strategies to improve outcomes of bullous pemphigoid: a comprehensive review of clinical presentations, diagnosis, and patients' assessment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:661-673. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267573

This patient was given a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Although there were a number of clues that pointed to this diagnosis, confirming that this was the case required 2 biopsies and a blood draw. (More on this in a bit.)

Although rare and potentially lethal, bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Patients present with tense bullae over limited or widespread areas of the skin. The pathogenesis includes development of autoimmune antibodies that target important proteins (BP180 and BP230) that bind basal epidermal keratinocytes to the dermis. When weakened by inflammation at these sites, the skin delaminates at the dermal-epidermal junction, while the cells of the epidermis continue to bind to each other. This leads to itching, hive-like wheals, and tense fluid-filled bullae.

The differential diagnosis of an acute or semi-acute bullous disease includes bullous pemphigoid, IgA pemphigoid, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and Senear-Usher syndrome. In this case, the large tense bullae suggested bullous pemphigoid over the other diagnoses.

Initial diagnosis requires 2 biopsies be performed: One at the edge of a bulla for a standard pathologic exam to identify the skin level at which the bulla is forming, and another biopsy of skin near the site of inflammation (5-10 mm away) to be sent for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) in Michel’s medium or Zeus medium. In bullous pemphigoid, the separation is at the dermal-epidermal junction, and IgG and C3 are found in the DIF in the same location. There are a couple ways to differentiate this disorder from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—a similar blistering disorder in which autoantibodies attack collagen at the dermal-epidermal junction. A common approach is to send a patient’s serum for indirect immunofluorescence. This is done because it is impossible to distinguish between the 2 clinically.

While bullous pemphigoid has historically been treated with high-dose prednisone, it is more common now to treat with whole-body topical clobetasol and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day to avoid the adverse effects of the prednisone. Other immunosuppressive options, such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine, can provide the potency of prednisone with a more favorable long-term safety profile. Rituximab infusions are another very powerful and durable option in refractory or severe cases.1

This patient was treated with topical clobetasol and doxycycline 100 mg twice a day, but he had incomplete clearance after 2 to 3 weeks. At that point, mycophenolate mofetil was added to the regimen and was titrated up to 1000 mg twice daily. When clearance occurred, the clobetasol was discontinued and the mycophenolate mofetil was titrated down to 250 mg/d; the patient continues to maintain clearance at this dose. He continues on doxycycline 100 mg bid.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

This patient was given a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Although there were a number of clues that pointed to this diagnosis, confirming that this was the case required 2 biopsies and a blood draw. (More on this in a bit.)

Although rare and potentially lethal, bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Patients present with tense bullae over limited or widespread areas of the skin. The pathogenesis includes development of autoimmune antibodies that target important proteins (BP180 and BP230) that bind basal epidermal keratinocytes to the dermis. When weakened by inflammation at these sites, the skin delaminates at the dermal-epidermal junction, while the cells of the epidermis continue to bind to each other. This leads to itching, hive-like wheals, and tense fluid-filled bullae.

The differential diagnosis of an acute or semi-acute bullous disease includes bullous pemphigoid, IgA pemphigoid, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and Senear-Usher syndrome. In this case, the large tense bullae suggested bullous pemphigoid over the other diagnoses.

Initial diagnosis requires 2 biopsies be performed: One at the edge of a bulla for a standard pathologic exam to identify the skin level at which the bulla is forming, and another biopsy of skin near the site of inflammation (5-10 mm away) to be sent for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) in Michel’s medium or Zeus medium. In bullous pemphigoid, the separation is at the dermal-epidermal junction, and IgG and C3 are found in the DIF in the same location. There are a couple ways to differentiate this disorder from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—a similar blistering disorder in which autoantibodies attack collagen at the dermal-epidermal junction. A common approach is to send a patient’s serum for indirect immunofluorescence. This is done because it is impossible to distinguish between the 2 clinically.

While bullous pemphigoid has historically been treated with high-dose prednisone, it is more common now to treat with whole-body topical clobetasol and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day to avoid the adverse effects of the prednisone. Other immunosuppressive options, such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine, can provide the potency of prednisone with a more favorable long-term safety profile. Rituximab infusions are another very powerful and durable option in refractory or severe cases.1

This patient was treated with topical clobetasol and doxycycline 100 mg twice a day, but he had incomplete clearance after 2 to 3 weeks. At that point, mycophenolate mofetil was added to the regimen and was titrated up to 1000 mg twice daily. When clearance occurred, the clobetasol was discontinued and the mycophenolate mofetil was titrated down to 250 mg/d; the patient continues to maintain clearance at this dose. He continues on doxycycline 100 mg bid.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Ruggiero A, Megna M, Villani A, et al. Strategies to improve outcomes of bullous pemphigoid: a comprehensive review of clinical presentations, diagnosis, and patients' assessment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:661-673. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267573

1. Ruggiero A, Megna M, Villani A, et al. Strategies to improve outcomes of bullous pemphigoid: a comprehensive review of clinical presentations, diagnosis, and patients' assessment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:661-673. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267573

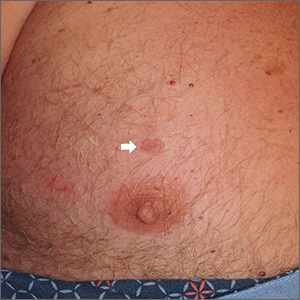

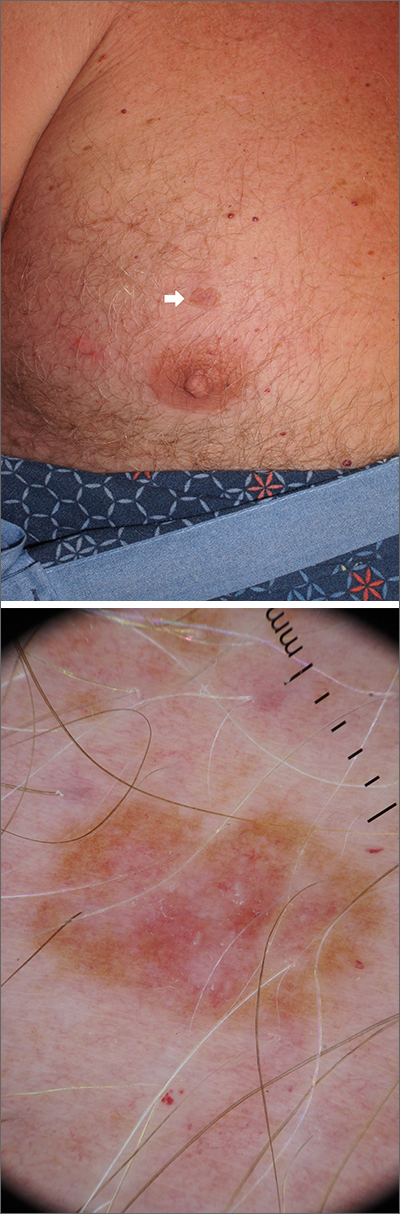

Solitary abdominal papule

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

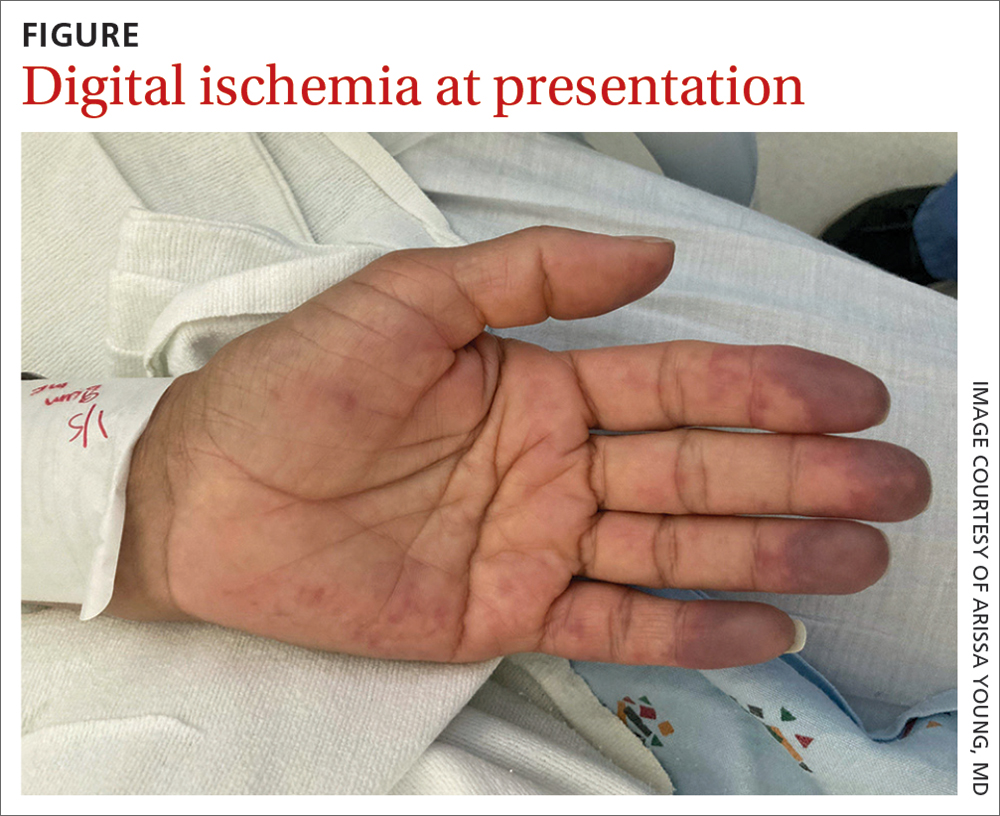

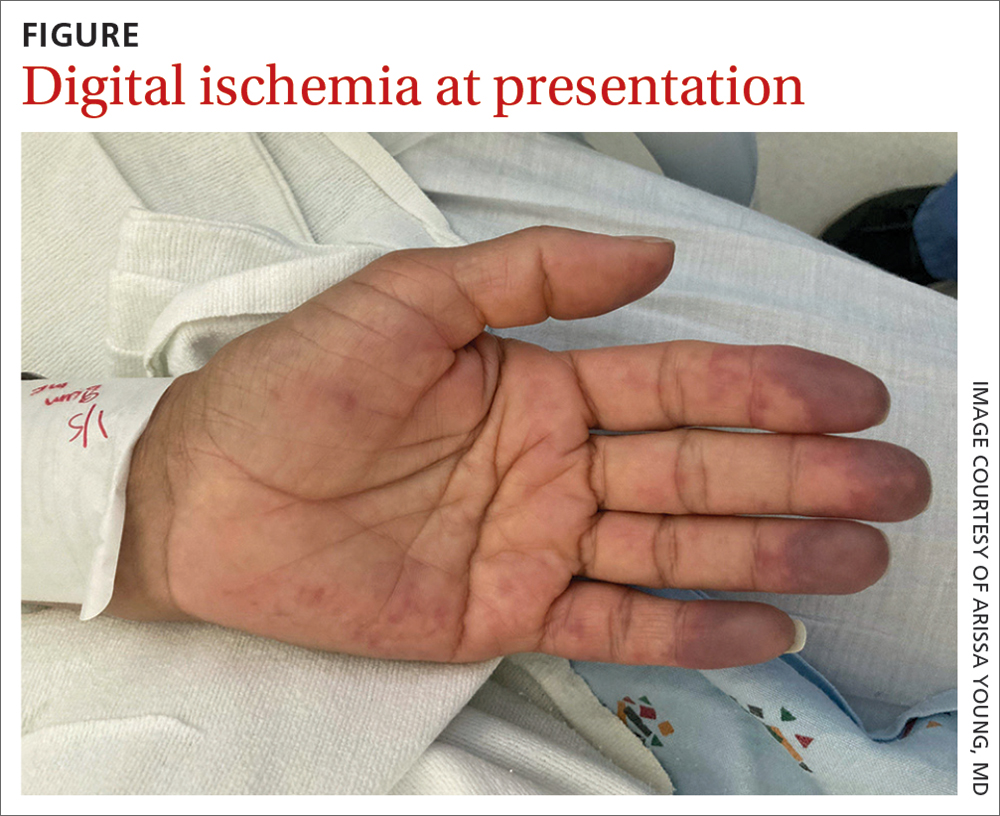

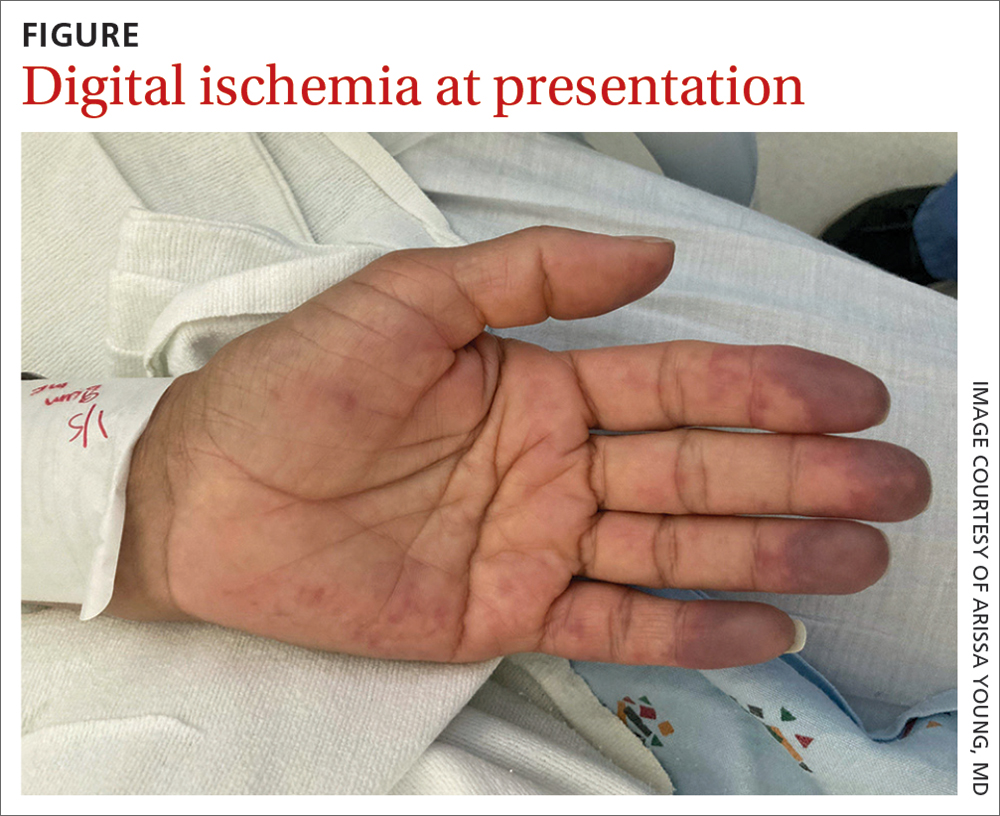

Painful blue fingers

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

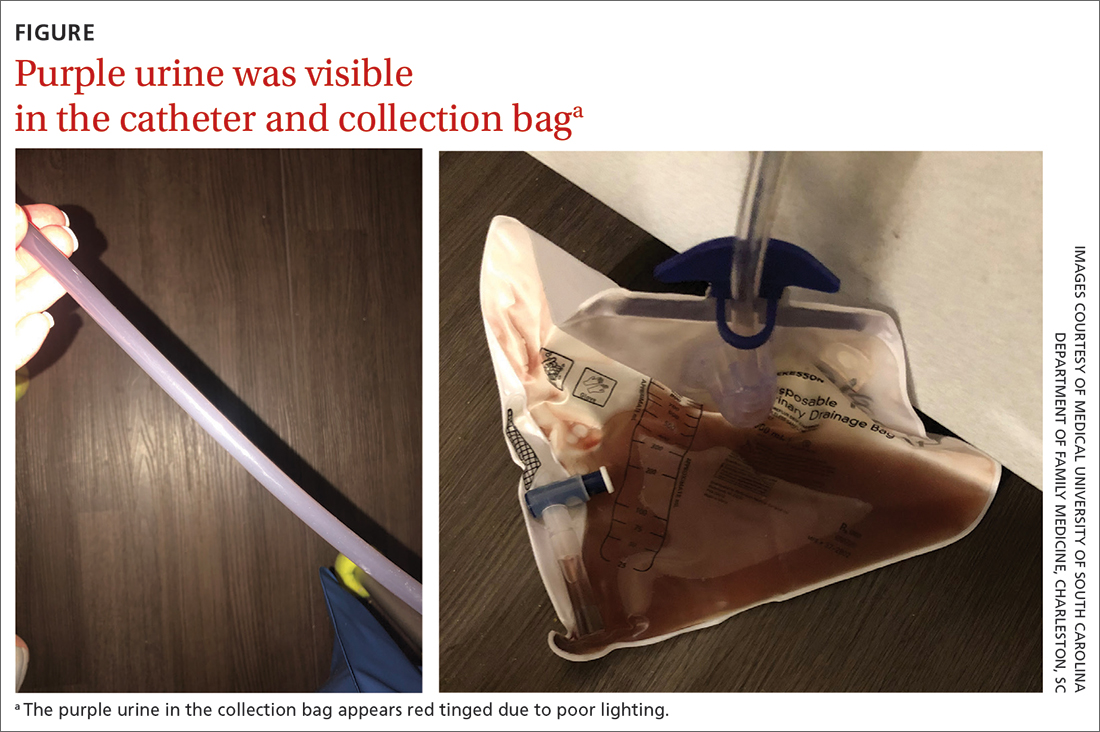

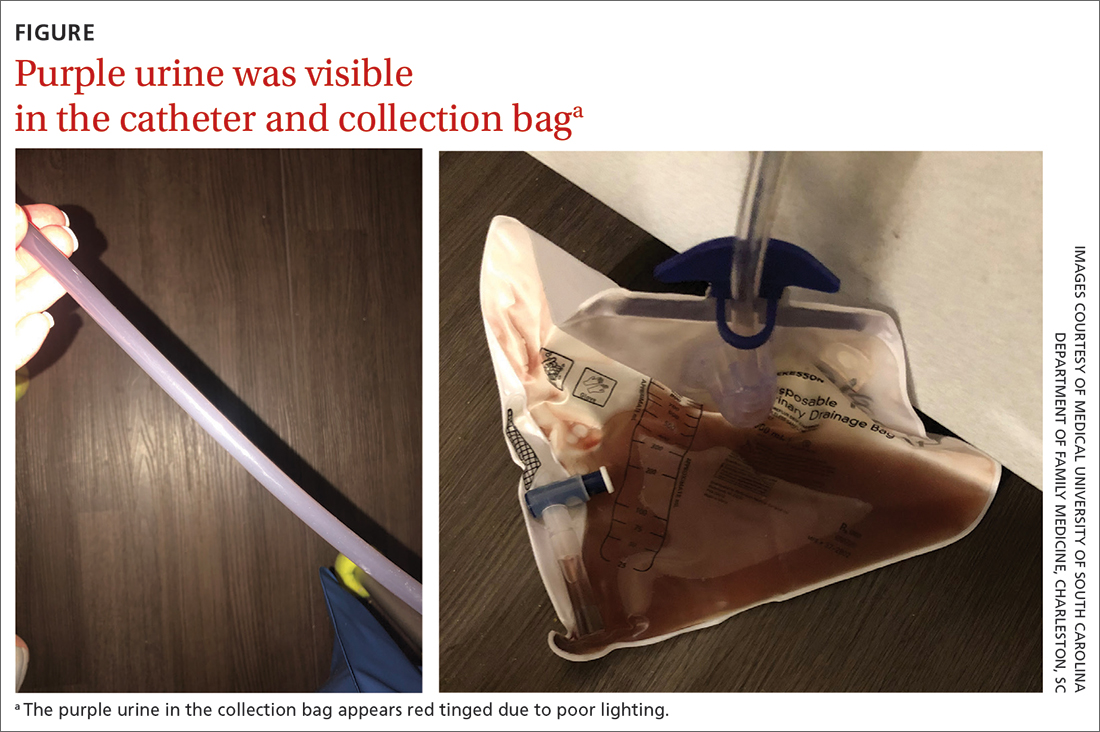

Catheterized urine color change

Physical examination revealed an older man whose vital signs were normal and who had a regular heart rate and rhythm. He denied any pain, and his abdomen was soft and nontender with normal bowel sounds. There was no suprapubic or costovertebral angle tenderness, and his urinary catheter was correctly placed. His urine output was within normal limits, but the urine in the catheter and collection bag was purple.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for mild cognitive impairment, BPH, and hypertension. A urine culture was significant for > 100,000 CFU/mL pan-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Purple urine bag syndrome

The diagnosis of purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) was made based on the patient’s clinical presentation and medical history. PUBS is generally a benign condition that can occur in patients who have urinary catheters for prolonged periods of time and urinary tract infections (UTIs), often with constipation.1

PUBS was first described in the literature in 1978.2 Its prevalence has been estimated to be 9.8% in long-term wards and higher in patients with chronic catheters.3-5 PUBS is reported more often in institutionalized older women, although it has been documented in men as well.1 Risk factors include having a chronic indwelling urinary catheter; alkaline urine; the use of plastic, polyvinylchloride urine bags3; chronic constipation6; renal failure4,5; and dementia.1 In many cases, patients with PUBS have been found to have stable vitals and lack systemic symptoms, such as fever, that could indicate an infection.1,5

The pathogenesis of PUBS has been associated with tryptophan.3 Gut bacteria metabolize tryptophan to indole, which is converted to indoxyl sulfate in the liver.3,7 Then certain bacteria associated with UTIs, including Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Providencia spp, Enterococcus faecalis, and Klebsiella,5-7 which contain indoxyl phosphatase and sulfatase enzymes, can convert indoxyl sulfate into indirubin (red) and indigo (blue) compounds; this results in a purple hue in the urine seen in a Foley catheter and bag.

Differential is generally limited to medication and food consumption

Clinical presentation and a detailed history and review of medication and/or food ingestion may distinguish PUBS from other conditions.

Medications and foods, such as rifampicin or beets, may discolor urine and need to be ruled out as a cause with a thorough history.3

Cyanide toxicity in those taking vitamin B12can result in purple-tinged urine.8 Signs and symptoms can alsoinclude reddening of the skin, dyspnea, nausea, headache, erythema at the injection site, and a modest increase in blood pressure.8

Identify the infection and treat as needed

There have been some case reports regarding the progression of PUBS to Fournier gangrene,4 but such cases are rare and associated with immunocompromised patients.9 PUBS is generally a benign condition associated with UTIs. Management involves identifying the underlying infection, treating with antibiotics if indicated (ie, patient is symptomatic or immunocompromised),3 providing proper treatment of constipation if needed, and replacing the Foley catheter.4 Some studies suggest that simply exchanging the catheter may resolve PUBS, particularly in asymptomatic patients.5

In light of his complicated urologic history, our patient was treated with a 10-day course of renally dosed intravenous cefepime (500 mg every 24 hours based on calculated creatine clearance of 21 mL/min) and Foley exchange. The patient’s urine color returned to normal after Foley exchange and 24 hours of antibiotics. His kidney function continued to improve and normalized by the time he was discharged from the facility approximately 2 weeks later.

1. Goyal A, Vikas G, Jindal J. Purple urine bag syndrome: series of nine cases and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:PR01-PR03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/34951.12202

2. Barlow GB, Dickson JAS. Purple urine bags. Lancet. 1978;28:220-221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90667-0

3. Richardson-May J. Single case of purple urine bag syndrome in an elderly woman with stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215465. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215465

4. Khan F, Chaudhry MA, Qureshi N, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome: an alarming hue? A brief review of the literature. Int J Nephrol. 2011;2011:419213. doi: 10.4061/2011/419213

5. Ben-Chetrit E, Munter G. Purple urine. JAMA. 2012;307:193-194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1997

6. Al Montasir A, Al Mustaque A. Purple urine bag syndrome. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:104-105. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109970

7. Dealler SF, Hawkey PM, Millar MR. Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes the purple urine bag syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2152-2156. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2152-2156.1988

8. Hudson M, Cashin BV, Matlock AG, et al. A man with purple urine. Hydroxocobalamin-induced chromaturia. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50:77. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.626782

9. Tasi Y-M, Huang M-S, Yang C-J, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome, not always a benign process. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:895-897. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.01.030

Physical examination revealed an older man whose vital signs were normal and who had a regular heart rate and rhythm. He denied any pain, and his abdomen was soft and nontender with normal bowel sounds. There was no suprapubic or costovertebral angle tenderness, and his urinary catheter was correctly placed. His urine output was within normal limits, but the urine in the catheter and collection bag was purple.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for mild cognitive impairment, BPH, and hypertension. A urine culture was significant for > 100,000 CFU/mL pan-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Purple urine bag syndrome

The diagnosis of purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) was made based on the patient’s clinical presentation and medical history. PUBS is generally a benign condition that can occur in patients who have urinary catheters for prolonged periods of time and urinary tract infections (UTIs), often with constipation.1

PUBS was first described in the literature in 1978.2 Its prevalence has been estimated to be 9.8% in long-term wards and higher in patients with chronic catheters.3-5 PUBS is reported more often in institutionalized older women, although it has been documented in men as well.1 Risk factors include having a chronic indwelling urinary catheter; alkaline urine; the use of plastic, polyvinylchloride urine bags3; chronic constipation6; renal failure4,5; and dementia.1 In many cases, patients with PUBS have been found to have stable vitals and lack systemic symptoms, such as fever, that could indicate an infection.1,5

The pathogenesis of PUBS has been associated with tryptophan.3 Gut bacteria metabolize tryptophan to indole, which is converted to indoxyl sulfate in the liver.3,7 Then certain bacteria associated with UTIs, including Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Providencia spp, Enterococcus faecalis, and Klebsiella,5-7 which contain indoxyl phosphatase and sulfatase enzymes, can convert indoxyl sulfate into indirubin (red) and indigo (blue) compounds; this results in a purple hue in the urine seen in a Foley catheter and bag.

Differential is generally limited to medication and food consumption

Clinical presentation and a detailed history and review of medication and/or food ingestion may distinguish PUBS from other conditions.

Medications and foods, such as rifampicin or beets, may discolor urine and need to be ruled out as a cause with a thorough history.3

Cyanide toxicity in those taking vitamin B12can result in purple-tinged urine.8 Signs and symptoms can alsoinclude reddening of the skin, dyspnea, nausea, headache, erythema at the injection site, and a modest increase in blood pressure.8

Identify the infection and treat as needed

There have been some case reports regarding the progression of PUBS to Fournier gangrene,4 but such cases are rare and associated with immunocompromised patients.9 PUBS is generally a benign condition associated with UTIs. Management involves identifying the underlying infection, treating with antibiotics if indicated (ie, patient is symptomatic or immunocompromised),3 providing proper treatment of constipation if needed, and replacing the Foley catheter.4 Some studies suggest that simply exchanging the catheter may resolve PUBS, particularly in asymptomatic patients.5

In light of his complicated urologic history, our patient was treated with a 10-day course of renally dosed intravenous cefepime (500 mg every 24 hours based on calculated creatine clearance of 21 mL/min) and Foley exchange. The patient’s urine color returned to normal after Foley exchange and 24 hours of antibiotics. His kidney function continued to improve and normalized by the time he was discharged from the facility approximately 2 weeks later.

Physical examination revealed an older man whose vital signs were normal and who had a regular heart rate and rhythm. He denied any pain, and his abdomen was soft and nontender with normal bowel sounds. There was no suprapubic or costovertebral angle tenderness, and his urinary catheter was correctly placed. His urine output was within normal limits, but the urine in the catheter and collection bag was purple.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for mild cognitive impairment, BPH, and hypertension. A urine culture was significant for > 100,000 CFU/mL pan-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Purple urine bag syndrome

The diagnosis of purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) was made based on the patient’s clinical presentation and medical history. PUBS is generally a benign condition that can occur in patients who have urinary catheters for prolonged periods of time and urinary tract infections (UTIs), often with constipation.1

PUBS was first described in the literature in 1978.2 Its prevalence has been estimated to be 9.8% in long-term wards and higher in patients with chronic catheters.3-5 PUBS is reported more often in institutionalized older women, although it has been documented in men as well.1 Risk factors include having a chronic indwelling urinary catheter; alkaline urine; the use of plastic, polyvinylchloride urine bags3; chronic constipation6; renal failure4,5; and dementia.1 In many cases, patients with PUBS have been found to have stable vitals and lack systemic symptoms, such as fever, that could indicate an infection.1,5

The pathogenesis of PUBS has been associated with tryptophan.3 Gut bacteria metabolize tryptophan to indole, which is converted to indoxyl sulfate in the liver.3,7 Then certain bacteria associated with UTIs, including Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Providencia spp, Enterococcus faecalis, and Klebsiella,5-7 which contain indoxyl phosphatase and sulfatase enzymes, can convert indoxyl sulfate into indirubin (red) and indigo (blue) compounds; this results in a purple hue in the urine seen in a Foley catheter and bag.

Differential is generally limited to medication and food consumption

Clinical presentation and a detailed history and review of medication and/or food ingestion may distinguish PUBS from other conditions.

Medications and foods, such as rifampicin or beets, may discolor urine and need to be ruled out as a cause with a thorough history.3

Cyanide toxicity in those taking vitamin B12can result in purple-tinged urine.8 Signs and symptoms can alsoinclude reddening of the skin, dyspnea, nausea, headache, erythema at the injection site, and a modest increase in blood pressure.8

Identify the infection and treat as needed

There have been some case reports regarding the progression of PUBS to Fournier gangrene,4 but such cases are rare and associated with immunocompromised patients.9 PUBS is generally a benign condition associated with UTIs. Management involves identifying the underlying infection, treating with antibiotics if indicated (ie, patient is symptomatic or immunocompromised),3 providing proper treatment of constipation if needed, and replacing the Foley catheter.4 Some studies suggest that simply exchanging the catheter may resolve PUBS, particularly in asymptomatic patients.5

In light of his complicated urologic history, our patient was treated with a 10-day course of renally dosed intravenous cefepime (500 mg every 24 hours based on calculated creatine clearance of 21 mL/min) and Foley exchange. The patient’s urine color returned to normal after Foley exchange and 24 hours of antibiotics. His kidney function continued to improve and normalized by the time he was discharged from the facility approximately 2 weeks later.

1. Goyal A, Vikas G, Jindal J. Purple urine bag syndrome: series of nine cases and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:PR01-PR03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/34951.12202

2. Barlow GB, Dickson JAS. Purple urine bags. Lancet. 1978;28:220-221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90667-0

3. Richardson-May J. Single case of purple urine bag syndrome in an elderly woman with stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215465. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215465

4. Khan F, Chaudhry MA, Qureshi N, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome: an alarming hue? A brief review of the literature. Int J Nephrol. 2011;2011:419213. doi: 10.4061/2011/419213

5. Ben-Chetrit E, Munter G. Purple urine. JAMA. 2012;307:193-194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1997

6. Al Montasir A, Al Mustaque A. Purple urine bag syndrome. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:104-105. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109970

7. Dealler SF, Hawkey PM, Millar MR. Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes the purple urine bag syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2152-2156. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2152-2156.1988

8. Hudson M, Cashin BV, Matlock AG, et al. A man with purple urine. Hydroxocobalamin-induced chromaturia. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50:77. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.626782

9. Tasi Y-M, Huang M-S, Yang C-J, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome, not always a benign process. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:895-897. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.01.030

1. Goyal A, Vikas G, Jindal J. Purple urine bag syndrome: series of nine cases and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:PR01-PR03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/34951.12202

2. Barlow GB, Dickson JAS. Purple urine bags. Lancet. 1978;28:220-221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90667-0

3. Richardson-May J. Single case of purple urine bag syndrome in an elderly woman with stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215465. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215465

4. Khan F, Chaudhry MA, Qureshi N, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome: an alarming hue? A brief review of the literature. Int J Nephrol. 2011;2011:419213. doi: 10.4061/2011/419213

5. Ben-Chetrit E, Munter G. Purple urine. JAMA. 2012;307:193-194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1997

6. Al Montasir A, Al Mustaque A. Purple urine bag syndrome. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:104-105. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109970

7. Dealler SF, Hawkey PM, Millar MR. Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes the purple urine bag syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2152-2156. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2152-2156.1988

8. Hudson M, Cashin BV, Matlock AG, et al. A man with purple urine. Hydroxocobalamin-induced chromaturia. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50:77. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.626782

9. Tasi Y-M, Huang M-S, Yang C-J, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome, not always a benign process. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:895-897. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.01.030

Widespread flaky red skin

This patient had erythroderma, which involves widespread erythema and scaling of the majority of the skin. Erythroderma can be caused by severe variants of several skin disorders, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and psoriasis. In this case, a punch biopsy from the forearm was most consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis.

Erythrodermic psoriasis is a rare subtype of psoriasis and most often develops as an exacerbation of preexisting plaque psoriasis and is defined by erythema, scale, and desquamation covering 75% to 90% of the body surface.1 The alteration in the skin negatively affects heat exchange and hemodynamics and can be life threatening. Many cases develop as a rebound reaction in patients with preexisting psoriasis treated with systemic steroids that are discontinued. Patients with dehydration, poor urinary output, hypotension, or significant weakness may benefit from supportive inpatient care while treatment is initiated.1

Initial treatment options for patients with erythrodermic psoriasis include biologics and steroid-sparing immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and acitretin. While a patient awaits the initiation of a definitive therapy, topical triamcinolone 0.1% may be applied over the entire skin surface twice daily and covered with 2 layers of scrubs or pajamas. The pair closest to the skin should be slightly damp and the outer pair should be dry to help retain heat. These are referred to as wet wraps or wet pajama wraps.

The patient described here was hemodynamically stable and was allowed to initiate wet pajama wrap therapy at home while awaiting initiation of adalimumab as an outpatient. He has improved dramatically with adalimumab given subcutaneously every 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Lo Y, Tsai TF. Updates on the treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:59-73. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S288345

This patient had erythroderma, which involves widespread erythema and scaling of the majority of the skin. Erythroderma can be caused by severe variants of several skin disorders, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and psoriasis. In this case, a punch biopsy from the forearm was most consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis.

Erythrodermic psoriasis is a rare subtype of psoriasis and most often develops as an exacerbation of preexisting plaque psoriasis and is defined by erythema, scale, and desquamation covering 75% to 90% of the body surface.1 The alteration in the skin negatively affects heat exchange and hemodynamics and can be life threatening. Many cases develop as a rebound reaction in patients with preexisting psoriasis treated with systemic steroids that are discontinued. Patients with dehydration, poor urinary output, hypotension, or significant weakness may benefit from supportive inpatient care while treatment is initiated.1

Initial treatment options for patients with erythrodermic psoriasis include biologics and steroid-sparing immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and acitretin. While a patient awaits the initiation of a definitive therapy, topical triamcinolone 0.1% may be applied over the entire skin surface twice daily and covered with 2 layers of scrubs or pajamas. The pair closest to the skin should be slightly damp and the outer pair should be dry to help retain heat. These are referred to as wet wraps or wet pajama wraps.

The patient described here was hemodynamically stable and was allowed to initiate wet pajama wrap therapy at home while awaiting initiation of adalimumab as an outpatient. He has improved dramatically with adalimumab given subcutaneously every 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

This patient had erythroderma, which involves widespread erythema and scaling of the majority of the skin. Erythroderma can be caused by severe variants of several skin disorders, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and psoriasis. In this case, a punch biopsy from the forearm was most consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis.

Erythrodermic psoriasis is a rare subtype of psoriasis and most often develops as an exacerbation of preexisting plaque psoriasis and is defined by erythema, scale, and desquamation covering 75% to 90% of the body surface.1 The alteration in the skin negatively affects heat exchange and hemodynamics and can be life threatening. Many cases develop as a rebound reaction in patients with preexisting psoriasis treated with systemic steroids that are discontinued. Patients with dehydration, poor urinary output, hypotension, or significant weakness may benefit from supportive inpatient care while treatment is initiated.1

Initial treatment options for patients with erythrodermic psoriasis include biologics and steroid-sparing immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and acitretin. While a patient awaits the initiation of a definitive therapy, topical triamcinolone 0.1% may be applied over the entire skin surface twice daily and covered with 2 layers of scrubs or pajamas. The pair closest to the skin should be slightly damp and the outer pair should be dry to help retain heat. These are referred to as wet wraps or wet pajama wraps.

The patient described here was hemodynamically stable and was allowed to initiate wet pajama wrap therapy at home while awaiting initiation of adalimumab as an outpatient. He has improved dramatically with adalimumab given subcutaneously every 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Lo Y, Tsai TF. Updates on the treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:59-73. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S288345

1. Lo Y, Tsai TF. Updates on the treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:59-73. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S288345

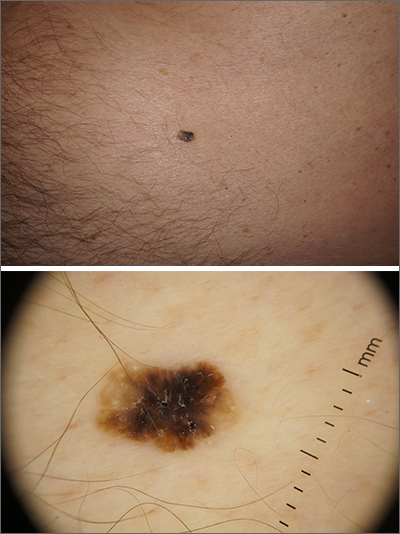

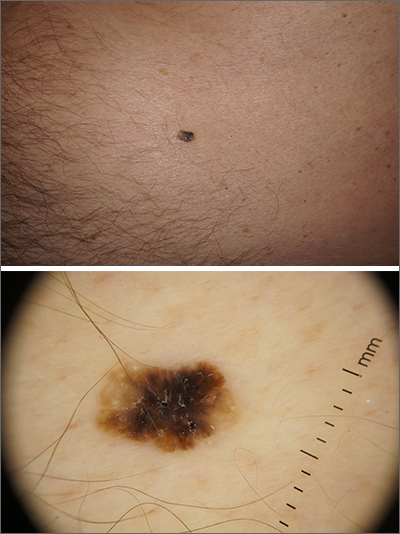

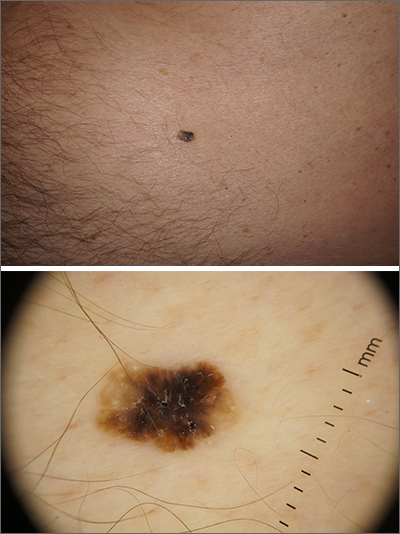

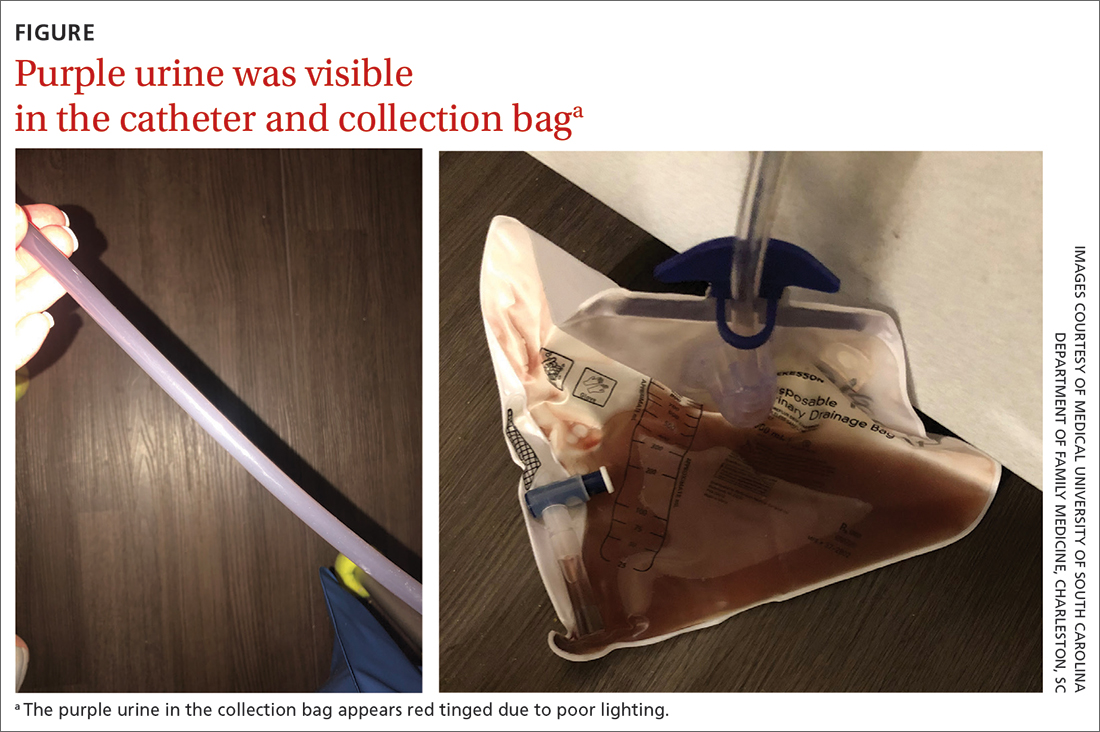

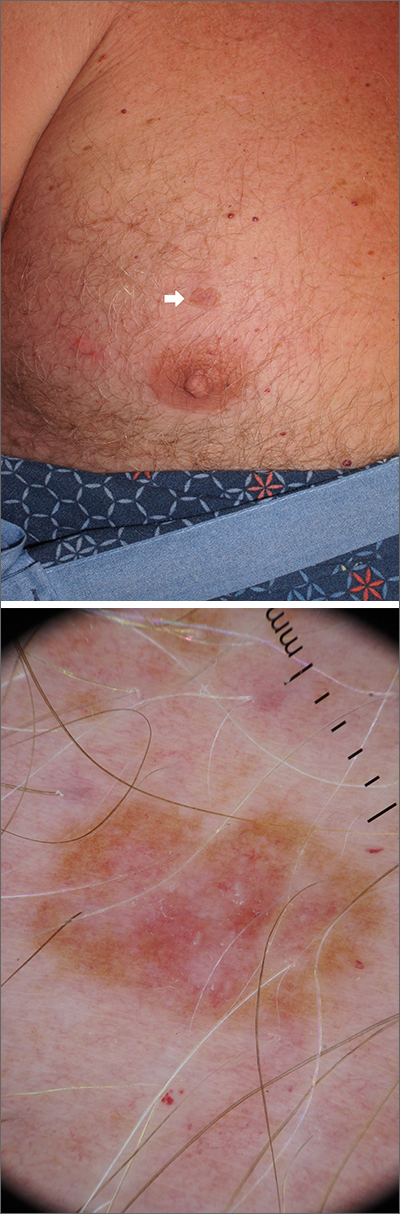

Chest lesion

A scoop shave biopsy was performed, including at least a 1-mm margin of normal-looking skin. Pathology was consistent with melanoma in situ.

Melanoma in situ, also called Stage 0 melanoma, is defined by atypical melanocytes that have not begun to invade the dermis and, therefore, have a Breslow thickness of 0 mm. While invasive melanoma is responsible for the largest number of skin cancer deaths in the United States (estimated to be 7990 in 2023), melanoma in situ maintains a very high cure rate when treated appropriately.1

Dermoscopy can help differentiate melanoma from benign nevi or other benign skin lesions. In this case, dermoscopy revealed a fine pigment network at the periphery that indicated this lesion was made up of melanocytes. There were also atypical vascular markings (the milky red color) in the center. Taken together, these findings were strongly indicative of melanoma.

Standard of care for melanoma in situ is a wide local excision with a margin of 5 to 10 mm. Melanoma in situ does not require sentinel lymph node biopsy. However, a lymph node biopsy would have been necessary if the melanoma had been ≥ 1 mm in thickness or if it had been ≥ 0.8 mm in thickness with higher-risk features, such as an increased number of mitoses per high-power field on pathology. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is emerging as an alternative method to wide local excision to treat melanoma in situ. However, it can only be done in specialized centers that can do rapid immunohistochemical staining on frozen sections. MMS is especially useful in cosmetically sensitive areas of the body and in areas where the true size of the melanoma in situ is unclear.

This patient subsequently underwent a wide local excision in the office with a margin of 6 mm. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not performed. The patient will continue with skin surveillance consisting of full skin exams 3 to 4 times in the first year of diagnosis, then twice annually for Years 2 to 5. He will then come in for annual skin exams after that.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2023. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed February 20, 2023. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

A scoop shave biopsy was performed, including at least a 1-mm margin of normal-looking skin. Pathology was consistent with melanoma in situ.

Melanoma in situ, also called Stage 0 melanoma, is defined by atypical melanocytes that have not begun to invade the dermis and, therefore, have a Breslow thickness of 0 mm. While invasive melanoma is responsible for the largest number of skin cancer deaths in the United States (estimated to be 7990 in 2023), melanoma in situ maintains a very high cure rate when treated appropriately.1

Dermoscopy can help differentiate melanoma from benign nevi or other benign skin lesions. In this case, dermoscopy revealed a fine pigment network at the periphery that indicated this lesion was made up of melanocytes. There were also atypical vascular markings (the milky red color) in the center. Taken together, these findings were strongly indicative of melanoma.

Standard of care for melanoma in situ is a wide local excision with a margin of 5 to 10 mm. Melanoma in situ does not require sentinel lymph node biopsy. However, a lymph node biopsy would have been necessary if the melanoma had been ≥ 1 mm in thickness or if it had been ≥ 0.8 mm in thickness with higher-risk features, such as an increased number of mitoses per high-power field on pathology. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is emerging as an alternative method to wide local excision to treat melanoma in situ. However, it can only be done in specialized centers that can do rapid immunohistochemical staining on frozen sections. MMS is especially useful in cosmetically sensitive areas of the body and in areas where the true size of the melanoma in situ is unclear.

This patient subsequently underwent a wide local excision in the office with a margin of 6 mm. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not performed. The patient will continue with skin surveillance consisting of full skin exams 3 to 4 times in the first year of diagnosis, then twice annually for Years 2 to 5. He will then come in for annual skin exams after that.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.