User login

How Does Your PICCOMPARE? A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Various PICC Materials in Pediatrics

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have evolved since their inception in the early 1970s and are used with increasing frequency for pediatric inpatients and outpatients.1-3 Emerging literature, including a meta-analysis of international observational studies,4 reports PICC failure (complications necessitating premature removal) occurs in up to 30% of PICCs, most commonly due to infection, thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture.4-7 Raffini et al.7 report the increasing incidence of pediatric PICC-related thrombosis increases morbidity and mortality8 and negatively impacts future vessel health and preservation.9

PICCs have progressed from relatively simple, silicone-based catheters with an external clamp to chemically engineered polyurethane with pressure-activated valves placed at the proximal or distal catheter hub with the intent to reduce occlusion.10 Further modernization of PICC material occurred with the incorporation of antithrombogenic (AT) material (Endexo®). These PICCs are designed to contain a nonstick polymer, which is designed to reduce the adherence of blood components (platelets and clotting factors) and inhibit thrombus formation (and hence prevent deep vein thrombosis andocclusion, as well as inhibit microbial biofilm attachment [and subsequent infection]).11

In addition to new materials, other aspects of this PICC design have been the addition of a pressure-activated safety valve (PASV®) built into the proximal hub. Pressure-activated valve technology promises to prevent catheter occlusion by reducing blood reflux into the PICC; the valve opens with pressure during infusion and aspiration and remains closed with normal venous pressure, circumventing the need for clinicians to manually clamp the PICC and reducing human error and the potential for thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture development.12 Hoffer et al.13 reported half as many occlusions of valved PICCs (3.3%) compared with nonvalved or clamped PICCs (7.1%); although not statistically significant (P = .10), perhaps due to the small sample, overall complications, including occlusion and infection, were significantly lessened with the valved PICC (35% vs 79%; P = .02). Comparatively, Pittiruti et al.14 conducted a trial of 2 types of valved PICCs with an open-ended, nonvalved PICC and found no reduction in PICC occlusion or catheter malfunction.

Today, PICC use is common for patients who require short-to-medium intravenous therapy. PICCs are increasingly recognized for their significant complications, including thrombosis and infection.15 Novel PICC technology, including the incorporation of AT material such as Endexo® and PASV®, may reduce complications; however, the clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability of these innovations have not been tested through randomized trials in pediatric patients. In accordance with Medical Research Council guidelines16 for developing interventions, we pilot tested the feasibility of the BioFlo® PICC, including intervention acceptability, compliance, recruitment, and initial estimates of effect, in anticipation of a subsequent full-scale efficacy randomized controlled trial. Our secondary aim was to compare the effectiveness of the BioFlo® PICC with Endexo® and PASV® technology in reducing PICC complications and failure.

METHODS

Design

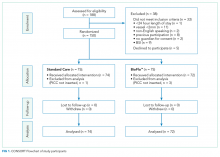

We undertook a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing the standard polyurethane PICC (with external clamp) with the BioFlo® PICC (with internal valve) in preventing catheter failure in pediatric patients. The study was prospectively registered with the Australian Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615001290583), and the research protocol was published.17

Study Setting

The study commenced in March 2016 at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in South Brisbane, Australia, a tertiary-level, specialist, pediatric teaching hospital in Queensland, Australia, providing full-spectrum health services to children and young people from birth to 18 years of age. Recruitment, including data collection, was completed in November 2016.

Sample

The target sample size was 110 participants, 50 participants per group plus 10% for potential attrition, as determined by standard pilot trial sample size recommendations.18 With ethics approval, the sample size was later increased to 150 participants in order to adequately pilot a microbiological substudy method (published separately).17 Participants were consecutively recruited if they met the inclusion criteria: PICC insertion, age <18 years, predicted hospital stay >24 hours, single-lumen PICC, and written informed consent by an English-speaking, legal parent or guardian. Patients were excluded if they had a current (<48 hours) blood stream infection (BSI), vessel size <2 mm, could not speak English without an interpreter, required a multilumen PICC, or were previously enrolled in the study.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive either of the following PICCs: (1) standard care: Cook™ polyurethane, turbo-ject, power-injectable PICC (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) or (2) comparison: BioFlo® polyurethane with Endexo® technology (AngioDynamics Inc, Queensbury, NY).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was feasibility of a full-efficacy trial established by composite analysis of the elements of eligibility (>70% of patients will be eligible), recruitment (>70% of patients will agree to enroll), retention and attrition (<15% of participants are lost to follow-up or withdraw from the study), protocol adherence (>80% of participants receive their allocated, randomly assigned study product), missing data (<10% of data are missed during data collection), parent and healthcare staff satisfaction, and PICC failure effect size estimates to allow sample size calculations.18,19 PICC failure was defined as the following complications associated with PICC removal: (1) catheter-associated BSI,8,20-22 (2) local site infection,22 (3) venous thrombosis,23 (4) occlusion,24,25 (5) PICC fracture, or (6) PICC dislodgement.25,26 Parents (or caregivers) and healthcare staff were asked to rate their level of confidence with the study product and ease of PICC removal by using a 0 to 100 numeric rating scale (NRS) of increasing confidence and/or ease. These data were collected at the time of PICC removal. Operators were also asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with the insertion equipment and ease of PICC insertion immediately upon completion of the insertion procedure (both 0-100 NRS of increasing satisfaction and/or ease). Secondary outcomes included individual PICC complications (eg, occlusion) occurring at any time point during the PICC dwell (including at removal), adverse events, pain, redness at the insertion site, and overall PICC dwell.

Study Procedures

The research nurse (ReN) screened operating theater lists for patients, obtained written informed consent, and initiated the randomization. Randomization was computer generated, and web based via Griffith University (https://www151.griffith.edu.au/random) to ensure allocation concealment until study entry. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio with computer-generated and randomly varied block sizes of 2 and 4. Data were collected by the ReN on the day of insertion, at day 1 postinsertion, then every 2 to 3 days thereafter so that PICCs were checked at least twice per week until study completion. Participants were included in the trial until 12 weeks post-PICC insertion, study withdrawal or PICC removal (whichever came first), with an additional 48 hours follow-up for infection outcomes. Patient review was face to face during the inpatient stay, with discharged patients’ follow-up occurring via outpatient clinics, hospital-in-the-home service, or telephone.

Data collection was via Research Electronic Data Capture (http://project-redcap.org/). The ReN collected data on primary and secondary outcomes by using the predefined criteria. Demographic and clinical data were collected to assess the success of randomization, describe the participant group, and display characteristics known to increase the risk of PICC complication and thrombosis. A blinded radiologist and infectious disease specialist reviewed and diagnosed thrombosis of deep veins and catheter-associated BSI outcomes, respectively.

PICC Procedures

Extensive prestudy education for 2 months prior to trial commencement was provided to all clinicians involved with the insertion and care of PICCs, including the study products. PICCs were inserted in an operating theater environment by a qualified consultant pediatric anesthetist, a senior anesthetic registrar or fellow in an approved anesthetic training program, or pediatric vascular access nurse practitioner. Ultrasound guidance was used to assess a patient’s vasculature and puncture the vessel. The operator chose the PICC size on the basis of clinical judgment of vessel size and patient needs and then inserted the allocated PICC.27 Preferred PICC tip location was the cavoatrial junction. All PICC tip positions were confirmed with a chest x-ray before use.

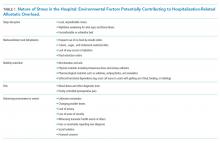

Postinsertion, PICCs were managed by local interdisciplinary clinicians in accordance with local practice guidelines.27-31 PICC care and management includes the use of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% alcohol for site antisepsis and neutral displacement needleless connectors (TUTA Pulse; Medical Australia Limited, Lidcombe, New South Wales, Australia); normal saline was used to flush after medication administration, and if the device was not in use for 6 hours or longer, heparin is instilled with securement via bordered polyurethane dressing (Tegaderm 1616; 3M, St Paul, Minnesota) and a sutureless securement device (Statlock VPPCSP; Bard, Georgia).

Statistical Analyses

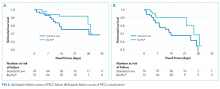

Data were exported to Stata 1532 for cleaning and analysis. Data cleaning of outlying figures and missing and implausible data was undertaken prior to analysis. Missing data were not imputed. The PICC was the unit of measurement, and all randomly assigned patients were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.33 Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to ascertain the primary outcome of feasibility for the larger trial. Incidence rates (per 1,000 catheter days) and rate ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated. The comparability of groups at baseline was described across demographic, clinical, and device characteristics. Kaplan-Meier survival curves (with log-rank tests) were used to compare PICC failure between study groups over time. Associations between baseline characteristics and failure were described by calculating hazard ratios (HRs). Univariable Cox regression was performed only due to the relatively low number of outcomes. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The Children’s Health Service District, Queensland (Human Research Ethics Committee/15/QRCH/164), and Griffith University (2016/077) Human Research Ethics Committees provided ethics and governance approval. Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, with children providing youth assent if they were 7 years or older, dependent upon cognitive ability.

RESULTS

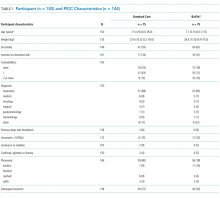

Participant and PICC Characteristics

Feasibility Outcomes

PICC Failure and Complications

As per supplementary Table 1, univariate Cox regression identified PICC failure as significantly associated with tip placement in the proximal superior vena cava (SVC) compared to the SVC–right atrium junction (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 1.17-5.82; P = .024). Reduced risk of PICC failure was significantly associated with any infusion during the dwell (continuous fluid infusion, P = .007; continuous antibiotic, P = .042; or intermittent infusion, P = .046) compared to no infusion. Other variables potentially influencing the risk of failure included PICC insertion by nurse specialist compared to consultant anesthetist (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 0.85-5.44) or registrar (HR 1.97; 95% CI, 0.57-6.77). These differences were not statistically significant; however, baseline imbalance between study groups for this variable and the feasibility design preclude absolute conclusions.

DISCUSSION

This is the first pilot feasibility trial of new PICC materials and valve design incorporated in the BioFlo® PICC in the pediatric population. The trial incorporated best practice for randomized trials, including using a concurrent control group, centralized and concealed randomization, predetermined feasibility criteria, and a registered and published trial protocol.17 As in other studies,15,24,34 PICC failure and complication prevalence was unacceptably high for this essential device. Standard care PICCs failed twice as often as the new BioFlo® PICCs (22% vs 11%), which is a clinically important difference. As researchers in a pilot study, we did not expect to detect statistically significant differences; however, we found that overall complications during the dwell occurred significantly more with the standard care than BioFlo® PICCs (P = .009).

BioFlo® PICC material offers a major advancement in PICC material through the incorporation of AT technologies into catheter materials, such as PICCs. Endexo® is a low molecular–weight, fluoro-oligomeric additive that self-locates to the top few nanometers of the material surface. When added to power-injectable polyurethane, the additive results in a strong but passive, nonstick, fluorinated surface in the base PICC material. This inhibits platelet adhesion, suppresses protein procoagulant conformation, and thereby reduces thrombus formation in medical devices. Additionally, Endexo® is not a catheter coating; rather, it is incorporated within the polyurethane of the PICC, thereby ensuring these AT properties are present on the internal, external, and cut surfaces of the PICC. If this technology can reduce complication during treatment and reduce failure from infection, thrombosis, occlusion, fracture, and dislodgement, it will improve patient outcomes considerably and lower health system costs. Previous studies investigating valve technology in PICC design to reduce occlusion have been inconclusive.12-14,35,36 Occlusion (both partial and complete) was less frequent in our study with the BioFlo® group (n = 3; 4%) compared to the standard care group (n = 6; 8%). The results of this pilot study suggest that either the Endexo® material or PASV® technology has a positive association with occlusion reduction during PICC treatment.

Thrombosis was the primary failure type for the standard care PICCs, comprising one-third of failures. All but one patient with radiologically confirmed thrombosis required the removal of the PICC prior to completion of treatment. The decision to remove the PICC or retain and treat conservatively remained with the treating team. Raffini et al.7 found thrombosis to increase in patients with one or more coexisting chronic medical condition. Slightly more standard care than BioFlo® patients were free of such comorbidities (25% vs 16%), yet standard care patients still had the higher number of thromboses (7% vs 3%). Morgenthaler and Rodriguez37 reported vascular access-associated thrombosis in pediatrics to be less common than in adults but higher in medically complex children. Worryingly, Menendez et al.38 reported pediatric thrombosis to be largely asymptomatic, so the true incidence in our study is likely higher because only radiologically confirmed thromboses were recorded.

Occlusion (partial or complete) was the predominant complication across the study, being associated with one-third of all failures. When occlusion complications during the dwell (some of which were resolved with treatment), in addition to those causing failure, were considered, this number was even greater. Occlusion complications are prevalent and costly. Smith et al.24 reported that occlusion was the most common reason for PICC removal and the most likely complication to delay treatment. Both the BioFlo® and standard care PICCs are pressure rated with good tensile strength; however, fracture occurred in 4% (n = 3) of standard care PICCs compared to no fractures in BioFlo® PICCs. Although the numbers are small, it may suggest a superior tensile strength of the BioFlo® material.

This study reinforces previously published results24,38 that PICC tip position is important and can influence complications, such as occlusion and thrombosis. In addition, we found a significant association with failure when PICCs did not have a continuous infusion. These findings reinforce the need for optimal tip location at insertion and ongoing flushing and maintenance of PICCs not used for infusions.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which was not designed to detect statistical differences in the primary outcome between groups. Despite randomization, there were slight imbalances at baseline for inserter type and leukocyte count, although these were not significantly associated with PICC failure in the Cox regression (data not shown), and thus were unlikely to influence findings. Additionally, a difference of <10% was associated with PICC tip position, favoring the BioFlo® group. PICC tip position outside the cavoatrial junction was positively associated with failure; therefore, the effect of tip positioning on outcomes is difficult to ascertain given the small sample size and feasibility nature of the study. Further study is warranted to further explore this effect. The population sampled was pediatric medical and surgical inpatients with a vessel size >2 mm attending the operating theater suite for PICC insertion, thereby limiting the study’s generalizability to adults and other populations, including neonates and those with PICCs inserted in the pediatric intensive care unit. The study could not be blinded because study products had to be visible to the clinical and research staff. However, it is unlikely that staff would intentionally sabotage PICCs to bias the study. Blinding was possible for the assessment of blood culture and ultrasound reports to diagnose infection and thrombosis. Strengths of this study included 100% protocol adherence, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

These results confirm that PICC failure is unacceptably high and suggest that the innovative BioFlo® PICC material and design holds promise to improve PICC outcomes by reducing complications and overall PICC failure. Trials of this technology are feasible, safe, and acceptable to healthcare staff and parents. Further trials are required, including in other patient populations, to definitively identify clinical, cost-effective methods to prevent PICC failure and improve reliability during treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and parents of Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital for participating in this important research. A special thank you goes to the nurses within the Vascular Assessment and Management Service and to Karen Turner, Julieta Woosley, and Anna Dean for their efforts in data collecting and ensuring protocol adherence.

Disclosure

Griffith University has received unrestricted, investigator-initiated research or educational grants to support the research of T. K., A. J. U., and C. R. M. from product manufacturers 3M, Adhezion Inc, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, Baxter, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Centurion Medical Products, Cook Medical, Entrotech, FloMedical, ICU Medical Inc, Medical Australia Limited, Medtronic, Smiths Medical, and Teleflex. Griffith University has received consultancy payments on behalf of C. R. M., A. J. U., and T. K. from manufacturers 3M, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Mayo Healthcare Inc, ResQDevices, and Smiths Medical. AngioDynamics (the BioFlo® PICC manufacturer) provided partial funds to undertake this research via an unrestricted donation to Griffith University (but not the study authors). Queensland Health provided in-kind support to fund the remainder of the trial. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Ullman AJ, Cooke M, Kleidon T, Rickard CM. Road map for improvement: point prevalence audit and survey of central venous access devices in paediatric acute care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(2):123-130. PubMed

4. Ullman AJ, Marsh N, Mihala G, Cooke M, Rickard CM. Complications of central venous access devices: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1331-e1344. PubMed

5. Barrier A, Williams DJ, Connelly M, Creech CB. Frequency of peripherally inserted central catheter complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):519-521. PubMed

6. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):429-435. PubMed

7. Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children’s hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001-1008. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

9. Moureau NL, Trick N, Nifong T, et al. Vessel health and preservation (part 1): a new evidence-based approach to vascular access selection and management. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(3):351-356. PubMed

10. Poli P, Scocca A, Di Puccio F, Gallone G, Angelini L, Calabro EM. A comparative study on the mechanical behavior of polyurethane PICCs. J Vasc Access. 2016;17(2):175-181. PubMed

11. Interface Biologics. Surface modification technology platform. 2017. http://www.interfacebiologics.com/endexo.htm. Accessed April 5, 2017.

12. Hoffer EK, Bloch RD, Borsa JJ, Santulli P, Fontaine AB, Francoeur N. Peripherally inserted central catheters with distal versus proximal valves: prospective randomized trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(10):1173-1177. PubMed

13. Hoffer EK, Borsa J, Santulli P, Bloch R, Fontaine AB. Prospective randomized comparison of valved versus nonvalved peripherally inserted central vein catheters. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(5):1393-1398. PubMed

14. Pittiruti M, Emoli A, Porta P, Marche B, DeAngelis R, Scoppettuolo G. A prospective, randomized comparison of three different types of valved and nonvalved peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(6):519-523.

15. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

16. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337. PubMed

17. Kleidon TM, Ullman AJ, Zhang L, Mihala G, Rickard CM. How does your PICCOMPARE? A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing PICC materials in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2017;(under review). PubMed

18. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(2):180-191. PubMed

19. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. PubMed

20. Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):908-918. PubMed

21. Kramer RD, Rogers MA, Conte M, Mann J, Saint S, Chopra V. Are antimicrobial peripherally inserted central catheters associated with reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infection? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(2):108-114. PubMed

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network Device Associated Module: CLABSI. 2014.

23. Lobo BL, Vaidean G, Broyles J, Reaves AB, Shorr RI. Risk of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with peripherally inserted central catheters. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):417-422. PubMed

24. Smith SN, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and Predictors of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Occlusion: The 3P-O Study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 28(5):749.e742-756.e742. PubMed

25. Chow LML, Friedman JN, MacArthur C, et al. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) fracture and embolozation in the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2003;142(2):141-144. PubMed

26. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Flanders SA, Krein SL. Vascular nursing experience, practice knowledge, and beliefs: Results from the Michigan PICC1 survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(4):269-275. PubMed

27. Frasca D, Dahyot-Fizelier C, Mimoz O. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):212. PubMed

28. Centre for Healthcare Related Infection Surveilance and Prevention and Tuberculosis Control. Guideline: Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). 2013.

29. Services Children’s Health Service. Central venous catheters: nursing care and management of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in paediatric patients. 2011. http://qheps.health.qld.gov.au/childrenshealth/resources/nursestand/docs/ns_03452.pdf. Accessed Februrary 1, 2016.

30. Services CsH. Central Venous Access Device Insertion and Management. 2014.

31. Central venous access device insertion and management. Queensland Government; 2014. http://qheps.health.qld.gov.au/childrenshealth/resources/proc/docs/proc_03450.pdf Accessed March 13, 2014.

32. StatCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12.1 College Station. 2006.

33. Rothwell PM. Factors that can affect the external validity of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(1):e9. PubMed

34. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Lee A, Krein S. Peripherally inserted central catheter-related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(6):847-854. PubMed

35. Alport B, Burbridge B, Lim H. Bard PowerPICC Solo2 vs Cook Turbo-Ject: A Tale of Two PICCs. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2012;63(4):323-328. PubMed

36. Johnston AJ, Streater CT, Noorani R, Crofts JL, Del Mundo AB, Parker RA. The effect of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) valve technology on catheter occlusion rates—the ‘ELeCTRiC’ study. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(4):421-425. PubMed

37. Morgenthaler TI, Rodriguez V. Preventing acute care-associated venous thromboembolism in adult and pediatric patients across a large healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(Suppl 2):S15-S21. PubMed

38. Menendez JJ, Verdu C, Calderon B, et al. Incidence and risk factors of superficial and deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(11):2158-2168. PubMed

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have evolved since their inception in the early 1970s and are used with increasing frequency for pediatric inpatients and outpatients.1-3 Emerging literature, including a meta-analysis of international observational studies,4 reports PICC failure (complications necessitating premature removal) occurs in up to 30% of PICCs, most commonly due to infection, thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture.4-7 Raffini et al.7 report the increasing incidence of pediatric PICC-related thrombosis increases morbidity and mortality8 and negatively impacts future vessel health and preservation.9

PICCs have progressed from relatively simple, silicone-based catheters with an external clamp to chemically engineered polyurethane with pressure-activated valves placed at the proximal or distal catheter hub with the intent to reduce occlusion.10 Further modernization of PICC material occurred with the incorporation of antithrombogenic (AT) material (Endexo®). These PICCs are designed to contain a nonstick polymer, which is designed to reduce the adherence of blood components (platelets and clotting factors) and inhibit thrombus formation (and hence prevent deep vein thrombosis andocclusion, as well as inhibit microbial biofilm attachment [and subsequent infection]).11

In addition to new materials, other aspects of this PICC design have been the addition of a pressure-activated safety valve (PASV®) built into the proximal hub. Pressure-activated valve technology promises to prevent catheter occlusion by reducing blood reflux into the PICC; the valve opens with pressure during infusion and aspiration and remains closed with normal venous pressure, circumventing the need for clinicians to manually clamp the PICC and reducing human error and the potential for thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture development.12 Hoffer et al.13 reported half as many occlusions of valved PICCs (3.3%) compared with nonvalved or clamped PICCs (7.1%); although not statistically significant (P = .10), perhaps due to the small sample, overall complications, including occlusion and infection, were significantly lessened with the valved PICC (35% vs 79%; P = .02). Comparatively, Pittiruti et al.14 conducted a trial of 2 types of valved PICCs with an open-ended, nonvalved PICC and found no reduction in PICC occlusion or catheter malfunction.

Today, PICC use is common for patients who require short-to-medium intravenous therapy. PICCs are increasingly recognized for their significant complications, including thrombosis and infection.15 Novel PICC technology, including the incorporation of AT material such as Endexo® and PASV®, may reduce complications; however, the clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability of these innovations have not been tested through randomized trials in pediatric patients. In accordance with Medical Research Council guidelines16 for developing interventions, we pilot tested the feasibility of the BioFlo® PICC, including intervention acceptability, compliance, recruitment, and initial estimates of effect, in anticipation of a subsequent full-scale efficacy randomized controlled trial. Our secondary aim was to compare the effectiveness of the BioFlo® PICC with Endexo® and PASV® technology in reducing PICC complications and failure.

METHODS

Design

We undertook a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing the standard polyurethane PICC (with external clamp) with the BioFlo® PICC (with internal valve) in preventing catheter failure in pediatric patients. The study was prospectively registered with the Australian Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615001290583), and the research protocol was published.17

Study Setting

The study commenced in March 2016 at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in South Brisbane, Australia, a tertiary-level, specialist, pediatric teaching hospital in Queensland, Australia, providing full-spectrum health services to children and young people from birth to 18 years of age. Recruitment, including data collection, was completed in November 2016.

Sample

The target sample size was 110 participants, 50 participants per group plus 10% for potential attrition, as determined by standard pilot trial sample size recommendations.18 With ethics approval, the sample size was later increased to 150 participants in order to adequately pilot a microbiological substudy method (published separately).17 Participants were consecutively recruited if they met the inclusion criteria: PICC insertion, age <18 years, predicted hospital stay >24 hours, single-lumen PICC, and written informed consent by an English-speaking, legal parent or guardian. Patients were excluded if they had a current (<48 hours) blood stream infection (BSI), vessel size <2 mm, could not speak English without an interpreter, required a multilumen PICC, or were previously enrolled in the study.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive either of the following PICCs: (1) standard care: Cook™ polyurethane, turbo-ject, power-injectable PICC (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) or (2) comparison: BioFlo® polyurethane with Endexo® technology (AngioDynamics Inc, Queensbury, NY).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was feasibility of a full-efficacy trial established by composite analysis of the elements of eligibility (>70% of patients will be eligible), recruitment (>70% of patients will agree to enroll), retention and attrition (<15% of participants are lost to follow-up or withdraw from the study), protocol adherence (>80% of participants receive their allocated, randomly assigned study product), missing data (<10% of data are missed during data collection), parent and healthcare staff satisfaction, and PICC failure effect size estimates to allow sample size calculations.18,19 PICC failure was defined as the following complications associated with PICC removal: (1) catheter-associated BSI,8,20-22 (2) local site infection,22 (3) venous thrombosis,23 (4) occlusion,24,25 (5) PICC fracture, or (6) PICC dislodgement.25,26 Parents (or caregivers) and healthcare staff were asked to rate their level of confidence with the study product and ease of PICC removal by using a 0 to 100 numeric rating scale (NRS) of increasing confidence and/or ease. These data were collected at the time of PICC removal. Operators were also asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with the insertion equipment and ease of PICC insertion immediately upon completion of the insertion procedure (both 0-100 NRS of increasing satisfaction and/or ease). Secondary outcomes included individual PICC complications (eg, occlusion) occurring at any time point during the PICC dwell (including at removal), adverse events, pain, redness at the insertion site, and overall PICC dwell.

Study Procedures

The research nurse (ReN) screened operating theater lists for patients, obtained written informed consent, and initiated the randomization. Randomization was computer generated, and web based via Griffith University (https://www151.griffith.edu.au/random) to ensure allocation concealment until study entry. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio with computer-generated and randomly varied block sizes of 2 and 4. Data were collected by the ReN on the day of insertion, at day 1 postinsertion, then every 2 to 3 days thereafter so that PICCs were checked at least twice per week until study completion. Participants were included in the trial until 12 weeks post-PICC insertion, study withdrawal or PICC removal (whichever came first), with an additional 48 hours follow-up for infection outcomes. Patient review was face to face during the inpatient stay, with discharged patients’ follow-up occurring via outpatient clinics, hospital-in-the-home service, or telephone.

Data collection was via Research Electronic Data Capture (http://project-redcap.org/). The ReN collected data on primary and secondary outcomes by using the predefined criteria. Demographic and clinical data were collected to assess the success of randomization, describe the participant group, and display characteristics known to increase the risk of PICC complication and thrombosis. A blinded radiologist and infectious disease specialist reviewed and diagnosed thrombosis of deep veins and catheter-associated BSI outcomes, respectively.

PICC Procedures

Extensive prestudy education for 2 months prior to trial commencement was provided to all clinicians involved with the insertion and care of PICCs, including the study products. PICCs were inserted in an operating theater environment by a qualified consultant pediatric anesthetist, a senior anesthetic registrar or fellow in an approved anesthetic training program, or pediatric vascular access nurse practitioner. Ultrasound guidance was used to assess a patient’s vasculature and puncture the vessel. The operator chose the PICC size on the basis of clinical judgment of vessel size and patient needs and then inserted the allocated PICC.27 Preferred PICC tip location was the cavoatrial junction. All PICC tip positions were confirmed with a chest x-ray before use.

Postinsertion, PICCs were managed by local interdisciplinary clinicians in accordance with local practice guidelines.27-31 PICC care and management includes the use of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% alcohol for site antisepsis and neutral displacement needleless connectors (TUTA Pulse; Medical Australia Limited, Lidcombe, New South Wales, Australia); normal saline was used to flush after medication administration, and if the device was not in use for 6 hours or longer, heparin is instilled with securement via bordered polyurethane dressing (Tegaderm 1616; 3M, St Paul, Minnesota) and a sutureless securement device (Statlock VPPCSP; Bard, Georgia).

Statistical Analyses

Data were exported to Stata 1532 for cleaning and analysis. Data cleaning of outlying figures and missing and implausible data was undertaken prior to analysis. Missing data were not imputed. The PICC was the unit of measurement, and all randomly assigned patients were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.33 Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to ascertain the primary outcome of feasibility for the larger trial. Incidence rates (per 1,000 catheter days) and rate ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated. The comparability of groups at baseline was described across demographic, clinical, and device characteristics. Kaplan-Meier survival curves (with log-rank tests) were used to compare PICC failure between study groups over time. Associations between baseline characteristics and failure were described by calculating hazard ratios (HRs). Univariable Cox regression was performed only due to the relatively low number of outcomes. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The Children’s Health Service District, Queensland (Human Research Ethics Committee/15/QRCH/164), and Griffith University (2016/077) Human Research Ethics Committees provided ethics and governance approval. Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, with children providing youth assent if they were 7 years or older, dependent upon cognitive ability.

RESULTS

Participant and PICC Characteristics

Feasibility Outcomes

PICC Failure and Complications

As per supplementary Table 1, univariate Cox regression identified PICC failure as significantly associated with tip placement in the proximal superior vena cava (SVC) compared to the SVC–right atrium junction (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 1.17-5.82; P = .024). Reduced risk of PICC failure was significantly associated with any infusion during the dwell (continuous fluid infusion, P = .007; continuous antibiotic, P = .042; or intermittent infusion, P = .046) compared to no infusion. Other variables potentially influencing the risk of failure included PICC insertion by nurse specialist compared to consultant anesthetist (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 0.85-5.44) or registrar (HR 1.97; 95% CI, 0.57-6.77). These differences were not statistically significant; however, baseline imbalance between study groups for this variable and the feasibility design preclude absolute conclusions.

DISCUSSION

This is the first pilot feasibility trial of new PICC materials and valve design incorporated in the BioFlo® PICC in the pediatric population. The trial incorporated best practice for randomized trials, including using a concurrent control group, centralized and concealed randomization, predetermined feasibility criteria, and a registered and published trial protocol.17 As in other studies,15,24,34 PICC failure and complication prevalence was unacceptably high for this essential device. Standard care PICCs failed twice as often as the new BioFlo® PICCs (22% vs 11%), which is a clinically important difference. As researchers in a pilot study, we did not expect to detect statistically significant differences; however, we found that overall complications during the dwell occurred significantly more with the standard care than BioFlo® PICCs (P = .009).

BioFlo® PICC material offers a major advancement in PICC material through the incorporation of AT technologies into catheter materials, such as PICCs. Endexo® is a low molecular–weight, fluoro-oligomeric additive that self-locates to the top few nanometers of the material surface. When added to power-injectable polyurethane, the additive results in a strong but passive, nonstick, fluorinated surface in the base PICC material. This inhibits platelet adhesion, suppresses protein procoagulant conformation, and thereby reduces thrombus formation in medical devices. Additionally, Endexo® is not a catheter coating; rather, it is incorporated within the polyurethane of the PICC, thereby ensuring these AT properties are present on the internal, external, and cut surfaces of the PICC. If this technology can reduce complication during treatment and reduce failure from infection, thrombosis, occlusion, fracture, and dislodgement, it will improve patient outcomes considerably and lower health system costs. Previous studies investigating valve technology in PICC design to reduce occlusion have been inconclusive.12-14,35,36 Occlusion (both partial and complete) was less frequent in our study with the BioFlo® group (n = 3; 4%) compared to the standard care group (n = 6; 8%). The results of this pilot study suggest that either the Endexo® material or PASV® technology has a positive association with occlusion reduction during PICC treatment.

Thrombosis was the primary failure type for the standard care PICCs, comprising one-third of failures. All but one patient with radiologically confirmed thrombosis required the removal of the PICC prior to completion of treatment. The decision to remove the PICC or retain and treat conservatively remained with the treating team. Raffini et al.7 found thrombosis to increase in patients with one or more coexisting chronic medical condition. Slightly more standard care than BioFlo® patients were free of such comorbidities (25% vs 16%), yet standard care patients still had the higher number of thromboses (7% vs 3%). Morgenthaler and Rodriguez37 reported vascular access-associated thrombosis in pediatrics to be less common than in adults but higher in medically complex children. Worryingly, Menendez et al.38 reported pediatric thrombosis to be largely asymptomatic, so the true incidence in our study is likely higher because only radiologically confirmed thromboses were recorded.

Occlusion (partial or complete) was the predominant complication across the study, being associated with one-third of all failures. When occlusion complications during the dwell (some of which were resolved with treatment), in addition to those causing failure, were considered, this number was even greater. Occlusion complications are prevalent and costly. Smith et al.24 reported that occlusion was the most common reason for PICC removal and the most likely complication to delay treatment. Both the BioFlo® and standard care PICCs are pressure rated with good tensile strength; however, fracture occurred in 4% (n = 3) of standard care PICCs compared to no fractures in BioFlo® PICCs. Although the numbers are small, it may suggest a superior tensile strength of the BioFlo® material.

This study reinforces previously published results24,38 that PICC tip position is important and can influence complications, such as occlusion and thrombosis. In addition, we found a significant association with failure when PICCs did not have a continuous infusion. These findings reinforce the need for optimal tip location at insertion and ongoing flushing and maintenance of PICCs not used for infusions.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which was not designed to detect statistical differences in the primary outcome between groups. Despite randomization, there were slight imbalances at baseline for inserter type and leukocyte count, although these were not significantly associated with PICC failure in the Cox regression (data not shown), and thus were unlikely to influence findings. Additionally, a difference of <10% was associated with PICC tip position, favoring the BioFlo® group. PICC tip position outside the cavoatrial junction was positively associated with failure; therefore, the effect of tip positioning on outcomes is difficult to ascertain given the small sample size and feasibility nature of the study. Further study is warranted to further explore this effect. The population sampled was pediatric medical and surgical inpatients with a vessel size >2 mm attending the operating theater suite for PICC insertion, thereby limiting the study’s generalizability to adults and other populations, including neonates and those with PICCs inserted in the pediatric intensive care unit. The study could not be blinded because study products had to be visible to the clinical and research staff. However, it is unlikely that staff would intentionally sabotage PICCs to bias the study. Blinding was possible for the assessment of blood culture and ultrasound reports to diagnose infection and thrombosis. Strengths of this study included 100% protocol adherence, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

These results confirm that PICC failure is unacceptably high and suggest that the innovative BioFlo® PICC material and design holds promise to improve PICC outcomes by reducing complications and overall PICC failure. Trials of this technology are feasible, safe, and acceptable to healthcare staff and parents. Further trials are required, including in other patient populations, to definitively identify clinical, cost-effective methods to prevent PICC failure and improve reliability during treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and parents of Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital for participating in this important research. A special thank you goes to the nurses within the Vascular Assessment and Management Service and to Karen Turner, Julieta Woosley, and Anna Dean for their efforts in data collecting and ensuring protocol adherence.

Disclosure

Griffith University has received unrestricted, investigator-initiated research or educational grants to support the research of T. K., A. J. U., and C. R. M. from product manufacturers 3M, Adhezion Inc, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, Baxter, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Centurion Medical Products, Cook Medical, Entrotech, FloMedical, ICU Medical Inc, Medical Australia Limited, Medtronic, Smiths Medical, and Teleflex. Griffith University has received consultancy payments on behalf of C. R. M., A. J. U., and T. K. from manufacturers 3M, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Mayo Healthcare Inc, ResQDevices, and Smiths Medical. AngioDynamics (the BioFlo® PICC manufacturer) provided partial funds to undertake this research via an unrestricted donation to Griffith University (but not the study authors). Queensland Health provided in-kind support to fund the remainder of the trial. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) have evolved since their inception in the early 1970s and are used with increasing frequency for pediatric inpatients and outpatients.1-3 Emerging literature, including a meta-analysis of international observational studies,4 reports PICC failure (complications necessitating premature removal) occurs in up to 30% of PICCs, most commonly due to infection, thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture.4-7 Raffini et al.7 report the increasing incidence of pediatric PICC-related thrombosis increases morbidity and mortality8 and negatively impacts future vessel health and preservation.9

PICCs have progressed from relatively simple, silicone-based catheters with an external clamp to chemically engineered polyurethane with pressure-activated valves placed at the proximal or distal catheter hub with the intent to reduce occlusion.10 Further modernization of PICC material occurred with the incorporation of antithrombogenic (AT) material (Endexo®). These PICCs are designed to contain a nonstick polymer, which is designed to reduce the adherence of blood components (platelets and clotting factors) and inhibit thrombus formation (and hence prevent deep vein thrombosis andocclusion, as well as inhibit microbial biofilm attachment [and subsequent infection]).11

In addition to new materials, other aspects of this PICC design have been the addition of a pressure-activated safety valve (PASV®) built into the proximal hub. Pressure-activated valve technology promises to prevent catheter occlusion by reducing blood reflux into the PICC; the valve opens with pressure during infusion and aspiration and remains closed with normal venous pressure, circumventing the need for clinicians to manually clamp the PICC and reducing human error and the potential for thrombosis, occlusion, and fracture development.12 Hoffer et al.13 reported half as many occlusions of valved PICCs (3.3%) compared with nonvalved or clamped PICCs (7.1%); although not statistically significant (P = .10), perhaps due to the small sample, overall complications, including occlusion and infection, were significantly lessened with the valved PICC (35% vs 79%; P = .02). Comparatively, Pittiruti et al.14 conducted a trial of 2 types of valved PICCs with an open-ended, nonvalved PICC and found no reduction in PICC occlusion or catheter malfunction.

Today, PICC use is common for patients who require short-to-medium intravenous therapy. PICCs are increasingly recognized for their significant complications, including thrombosis and infection.15 Novel PICC technology, including the incorporation of AT material such as Endexo® and PASV®, may reduce complications; however, the clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability of these innovations have not been tested through randomized trials in pediatric patients. In accordance with Medical Research Council guidelines16 for developing interventions, we pilot tested the feasibility of the BioFlo® PICC, including intervention acceptability, compliance, recruitment, and initial estimates of effect, in anticipation of a subsequent full-scale efficacy randomized controlled trial. Our secondary aim was to compare the effectiveness of the BioFlo® PICC with Endexo® and PASV® technology in reducing PICC complications and failure.

METHODS

Design

We undertook a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing the standard polyurethane PICC (with external clamp) with the BioFlo® PICC (with internal valve) in preventing catheter failure in pediatric patients. The study was prospectively registered with the Australian Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615001290583), and the research protocol was published.17

Study Setting

The study commenced in March 2016 at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in South Brisbane, Australia, a tertiary-level, specialist, pediatric teaching hospital in Queensland, Australia, providing full-spectrum health services to children and young people from birth to 18 years of age. Recruitment, including data collection, was completed in November 2016.

Sample

The target sample size was 110 participants, 50 participants per group plus 10% for potential attrition, as determined by standard pilot trial sample size recommendations.18 With ethics approval, the sample size was later increased to 150 participants in order to adequately pilot a microbiological substudy method (published separately).17 Participants were consecutively recruited if they met the inclusion criteria: PICC insertion, age <18 years, predicted hospital stay >24 hours, single-lumen PICC, and written informed consent by an English-speaking, legal parent or guardian. Patients were excluded if they had a current (<48 hours) blood stream infection (BSI), vessel size <2 mm, could not speak English without an interpreter, required a multilumen PICC, or were previously enrolled in the study.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive either of the following PICCs: (1) standard care: Cook™ polyurethane, turbo-ject, power-injectable PICC (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) or (2) comparison: BioFlo® polyurethane with Endexo® technology (AngioDynamics Inc, Queensbury, NY).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was feasibility of a full-efficacy trial established by composite analysis of the elements of eligibility (>70% of patients will be eligible), recruitment (>70% of patients will agree to enroll), retention and attrition (<15% of participants are lost to follow-up or withdraw from the study), protocol adherence (>80% of participants receive their allocated, randomly assigned study product), missing data (<10% of data are missed during data collection), parent and healthcare staff satisfaction, and PICC failure effect size estimates to allow sample size calculations.18,19 PICC failure was defined as the following complications associated with PICC removal: (1) catheter-associated BSI,8,20-22 (2) local site infection,22 (3) venous thrombosis,23 (4) occlusion,24,25 (5) PICC fracture, or (6) PICC dislodgement.25,26 Parents (or caregivers) and healthcare staff were asked to rate their level of confidence with the study product and ease of PICC removal by using a 0 to 100 numeric rating scale (NRS) of increasing confidence and/or ease. These data were collected at the time of PICC removal. Operators were also asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with the insertion equipment and ease of PICC insertion immediately upon completion of the insertion procedure (both 0-100 NRS of increasing satisfaction and/or ease). Secondary outcomes included individual PICC complications (eg, occlusion) occurring at any time point during the PICC dwell (including at removal), adverse events, pain, redness at the insertion site, and overall PICC dwell.

Study Procedures

The research nurse (ReN) screened operating theater lists for patients, obtained written informed consent, and initiated the randomization. Randomization was computer generated, and web based via Griffith University (https://www151.griffith.edu.au/random) to ensure allocation concealment until study entry. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio with computer-generated and randomly varied block sizes of 2 and 4. Data were collected by the ReN on the day of insertion, at day 1 postinsertion, then every 2 to 3 days thereafter so that PICCs were checked at least twice per week until study completion. Participants were included in the trial until 12 weeks post-PICC insertion, study withdrawal or PICC removal (whichever came first), with an additional 48 hours follow-up for infection outcomes. Patient review was face to face during the inpatient stay, with discharged patients’ follow-up occurring via outpatient clinics, hospital-in-the-home service, or telephone.

Data collection was via Research Electronic Data Capture (http://project-redcap.org/). The ReN collected data on primary and secondary outcomes by using the predefined criteria. Demographic and clinical data were collected to assess the success of randomization, describe the participant group, and display characteristics known to increase the risk of PICC complication and thrombosis. A blinded radiologist and infectious disease specialist reviewed and diagnosed thrombosis of deep veins and catheter-associated BSI outcomes, respectively.

PICC Procedures

Extensive prestudy education for 2 months prior to trial commencement was provided to all clinicians involved with the insertion and care of PICCs, including the study products. PICCs were inserted in an operating theater environment by a qualified consultant pediatric anesthetist, a senior anesthetic registrar or fellow in an approved anesthetic training program, or pediatric vascular access nurse practitioner. Ultrasound guidance was used to assess a patient’s vasculature and puncture the vessel. The operator chose the PICC size on the basis of clinical judgment of vessel size and patient needs and then inserted the allocated PICC.27 Preferred PICC tip location was the cavoatrial junction. All PICC tip positions were confirmed with a chest x-ray before use.

Postinsertion, PICCs were managed by local interdisciplinary clinicians in accordance with local practice guidelines.27-31 PICC care and management includes the use of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% alcohol for site antisepsis and neutral displacement needleless connectors (TUTA Pulse; Medical Australia Limited, Lidcombe, New South Wales, Australia); normal saline was used to flush after medication administration, and if the device was not in use for 6 hours or longer, heparin is instilled with securement via bordered polyurethane dressing (Tegaderm 1616; 3M, St Paul, Minnesota) and a sutureless securement device (Statlock VPPCSP; Bard, Georgia).

Statistical Analyses

Data were exported to Stata 1532 for cleaning and analysis. Data cleaning of outlying figures and missing and implausible data was undertaken prior to analysis. Missing data were not imputed. The PICC was the unit of measurement, and all randomly assigned patients were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.33 Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to ascertain the primary outcome of feasibility for the larger trial. Incidence rates (per 1,000 catheter days) and rate ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated. The comparability of groups at baseline was described across demographic, clinical, and device characteristics. Kaplan-Meier survival curves (with log-rank tests) were used to compare PICC failure between study groups over time. Associations between baseline characteristics and failure were described by calculating hazard ratios (HRs). Univariable Cox regression was performed only due to the relatively low number of outcomes. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The Children’s Health Service District, Queensland (Human Research Ethics Committee/15/QRCH/164), and Griffith University (2016/077) Human Research Ethics Committees provided ethics and governance approval. Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, with children providing youth assent if they were 7 years or older, dependent upon cognitive ability.

RESULTS

Participant and PICC Characteristics

Feasibility Outcomes

PICC Failure and Complications

As per supplementary Table 1, univariate Cox regression identified PICC failure as significantly associated with tip placement in the proximal superior vena cava (SVC) compared to the SVC–right atrium junction (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 1.17-5.82; P = .024). Reduced risk of PICC failure was significantly associated with any infusion during the dwell (continuous fluid infusion, P = .007; continuous antibiotic, P = .042; or intermittent infusion, P = .046) compared to no infusion. Other variables potentially influencing the risk of failure included PICC insertion by nurse specialist compared to consultant anesthetist (HR 2.61; 95% CI, 0.85-5.44) or registrar (HR 1.97; 95% CI, 0.57-6.77). These differences were not statistically significant; however, baseline imbalance between study groups for this variable and the feasibility design preclude absolute conclusions.

DISCUSSION

This is the first pilot feasibility trial of new PICC materials and valve design incorporated in the BioFlo® PICC in the pediatric population. The trial incorporated best practice for randomized trials, including using a concurrent control group, centralized and concealed randomization, predetermined feasibility criteria, and a registered and published trial protocol.17 As in other studies,15,24,34 PICC failure and complication prevalence was unacceptably high for this essential device. Standard care PICCs failed twice as often as the new BioFlo® PICCs (22% vs 11%), which is a clinically important difference. As researchers in a pilot study, we did not expect to detect statistically significant differences; however, we found that overall complications during the dwell occurred significantly more with the standard care than BioFlo® PICCs (P = .009).

BioFlo® PICC material offers a major advancement in PICC material through the incorporation of AT technologies into catheter materials, such as PICCs. Endexo® is a low molecular–weight, fluoro-oligomeric additive that self-locates to the top few nanometers of the material surface. When added to power-injectable polyurethane, the additive results in a strong but passive, nonstick, fluorinated surface in the base PICC material. This inhibits platelet adhesion, suppresses protein procoagulant conformation, and thereby reduces thrombus formation in medical devices. Additionally, Endexo® is not a catheter coating; rather, it is incorporated within the polyurethane of the PICC, thereby ensuring these AT properties are present on the internal, external, and cut surfaces of the PICC. If this technology can reduce complication during treatment and reduce failure from infection, thrombosis, occlusion, fracture, and dislodgement, it will improve patient outcomes considerably and lower health system costs. Previous studies investigating valve technology in PICC design to reduce occlusion have been inconclusive.12-14,35,36 Occlusion (both partial and complete) was less frequent in our study with the BioFlo® group (n = 3; 4%) compared to the standard care group (n = 6; 8%). The results of this pilot study suggest that either the Endexo® material or PASV® technology has a positive association with occlusion reduction during PICC treatment.

Thrombosis was the primary failure type for the standard care PICCs, comprising one-third of failures. All but one patient with radiologically confirmed thrombosis required the removal of the PICC prior to completion of treatment. The decision to remove the PICC or retain and treat conservatively remained with the treating team. Raffini et al.7 found thrombosis to increase in patients with one or more coexisting chronic medical condition. Slightly more standard care than BioFlo® patients were free of such comorbidities (25% vs 16%), yet standard care patients still had the higher number of thromboses (7% vs 3%). Morgenthaler and Rodriguez37 reported vascular access-associated thrombosis in pediatrics to be less common than in adults but higher in medically complex children. Worryingly, Menendez et al.38 reported pediatric thrombosis to be largely asymptomatic, so the true incidence in our study is likely higher because only radiologically confirmed thromboses were recorded.

Occlusion (partial or complete) was the predominant complication across the study, being associated with one-third of all failures. When occlusion complications during the dwell (some of which were resolved with treatment), in addition to those causing failure, were considered, this number was even greater. Occlusion complications are prevalent and costly. Smith et al.24 reported that occlusion was the most common reason for PICC removal and the most likely complication to delay treatment. Both the BioFlo® and standard care PICCs are pressure rated with good tensile strength; however, fracture occurred in 4% (n = 3) of standard care PICCs compared to no fractures in BioFlo® PICCs. Although the numbers are small, it may suggest a superior tensile strength of the BioFlo® material.

This study reinforces previously published results24,38 that PICC tip position is important and can influence complications, such as occlusion and thrombosis. In addition, we found a significant association with failure when PICCs did not have a continuous infusion. These findings reinforce the need for optimal tip location at insertion and ongoing flushing and maintenance of PICCs not used for infusions.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which was not designed to detect statistical differences in the primary outcome between groups. Despite randomization, there were slight imbalances at baseline for inserter type and leukocyte count, although these were not significantly associated with PICC failure in the Cox regression (data not shown), and thus were unlikely to influence findings. Additionally, a difference of <10% was associated with PICC tip position, favoring the BioFlo® group. PICC tip position outside the cavoatrial junction was positively associated with failure; therefore, the effect of tip positioning on outcomes is difficult to ascertain given the small sample size and feasibility nature of the study. Further study is warranted to further explore this effect. The population sampled was pediatric medical and surgical inpatients with a vessel size >2 mm attending the operating theater suite for PICC insertion, thereby limiting the study’s generalizability to adults and other populations, including neonates and those with PICCs inserted in the pediatric intensive care unit. The study could not be blinded because study products had to be visible to the clinical and research staff. However, it is unlikely that staff would intentionally sabotage PICCs to bias the study. Blinding was possible for the assessment of blood culture and ultrasound reports to diagnose infection and thrombosis. Strengths of this study included 100% protocol adherence, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

These results confirm that PICC failure is unacceptably high and suggest that the innovative BioFlo® PICC material and design holds promise to improve PICC outcomes by reducing complications and overall PICC failure. Trials of this technology are feasible, safe, and acceptable to healthcare staff and parents. Further trials are required, including in other patient populations, to definitively identify clinical, cost-effective methods to prevent PICC failure and improve reliability during treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and parents of Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital for participating in this important research. A special thank you goes to the nurses within the Vascular Assessment and Management Service and to Karen Turner, Julieta Woosley, and Anna Dean for their efforts in data collecting and ensuring protocol adherence.

Disclosure

Griffith University has received unrestricted, investigator-initiated research or educational grants to support the research of T. K., A. J. U., and C. R. M. from product manufacturers 3M, Adhezion Inc, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, Baxter, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Centurion Medical Products, Cook Medical, Entrotech, FloMedical, ICU Medical Inc, Medical Australia Limited, Medtronic, Smiths Medical, and Teleflex. Griffith University has received consultancy payments on behalf of C. R. M., A. J. U., and T. K. from manufacturers 3M, AngioDynamics, Bard Medical, B. Braun Medical Inc, Becton Dickinson, CareFusion, Mayo Healthcare Inc, ResQDevices, and Smiths Medical. AngioDynamics (the BioFlo® PICC manufacturer) provided partial funds to undertake this research via an unrestricted donation to Griffith University (but not the study authors). Queensland Health provided in-kind support to fund the remainder of the trial. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Ullman AJ, Cooke M, Kleidon T, Rickard CM. Road map for improvement: point prevalence audit and survey of central venous access devices in paediatric acute care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(2):123-130. PubMed

4. Ullman AJ, Marsh N, Mihala G, Cooke M, Rickard CM. Complications of central venous access devices: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1331-e1344. PubMed

5. Barrier A, Williams DJ, Connelly M, Creech CB. Frequency of peripherally inserted central catheter complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):519-521. PubMed

6. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):429-435. PubMed

7. Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children’s hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001-1008. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

9. Moureau NL, Trick N, Nifong T, et al. Vessel health and preservation (part 1): a new evidence-based approach to vascular access selection and management. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(3):351-356. PubMed

10. Poli P, Scocca A, Di Puccio F, Gallone G, Angelini L, Calabro EM. A comparative study on the mechanical behavior of polyurethane PICCs. J Vasc Access. 2016;17(2):175-181. PubMed

11. Interface Biologics. Surface modification technology platform. 2017. http://www.interfacebiologics.com/endexo.htm. Accessed April 5, 2017.

12. Hoffer EK, Bloch RD, Borsa JJ, Santulli P, Fontaine AB, Francoeur N. Peripherally inserted central catheters with distal versus proximal valves: prospective randomized trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(10):1173-1177. PubMed

13. Hoffer EK, Borsa J, Santulli P, Bloch R, Fontaine AB. Prospective randomized comparison of valved versus nonvalved peripherally inserted central vein catheters. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(5):1393-1398. PubMed

14. Pittiruti M, Emoli A, Porta P, Marche B, DeAngelis R, Scoppettuolo G. A prospective, randomized comparison of three different types of valved and nonvalved peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(6):519-523.

15. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

16. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337. PubMed

17. Kleidon TM, Ullman AJ, Zhang L, Mihala G, Rickard CM. How does your PICCOMPARE? A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing PICC materials in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2017;(under review). PubMed

18. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(2):180-191. PubMed

19. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. PubMed

20. Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):908-918. PubMed

21. Kramer RD, Rogers MA, Conte M, Mann J, Saint S, Chopra V. Are antimicrobial peripherally inserted central catheters associated with reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infection? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(2):108-114. PubMed

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network Device Associated Module: CLABSI. 2014.

23. Lobo BL, Vaidean G, Broyles J, Reaves AB, Shorr RI. Risk of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with peripherally inserted central catheters. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):417-422. PubMed

24. Smith SN, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and Predictors of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Occlusion: The 3P-O Study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 28(5):749.e742-756.e742. PubMed

25. Chow LML, Friedman JN, MacArthur C, et al. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) fracture and embolozation in the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2003;142(2):141-144. PubMed

26. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Flanders SA, Krein SL. Vascular nursing experience, practice knowledge, and beliefs: Results from the Michigan PICC1 survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(4):269-275. PubMed

27. Frasca D, Dahyot-Fizelier C, Mimoz O. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):212. PubMed

28. Centre for Healthcare Related Infection Surveilance and Prevention and Tuberculosis Control. Guideline: Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). 2013.

29. Services Children’s Health Service. Central venous catheters: nursing care and management of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in paediatric patients. 2011. http://qheps.health.qld.gov.au/childrenshealth/resources/nursestand/docs/ns_03452.pdf. Accessed Februrary 1, 2016.

30. Services CsH. Central Venous Access Device Insertion and Management. 2014.

31. Central venous access device insertion and management. Queensland Government; 2014. http://qheps.health.qld.gov.au/childrenshealth/resources/proc/docs/proc_03450.pdf Accessed March 13, 2014.

32. StatCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12.1 College Station. 2006.

33. Rothwell PM. Factors that can affect the external validity of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(1):e9. PubMed

34. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Lee A, Krein S. Peripherally inserted central catheter-related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(6):847-854. PubMed

35. Alport B, Burbridge B, Lim H. Bard PowerPICC Solo2 vs Cook Turbo-Ject: A Tale of Two PICCs. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2012;63(4):323-328. PubMed

36. Johnston AJ, Streater CT, Noorani R, Crofts JL, Del Mundo AB, Parker RA. The effect of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) valve technology on catheter occlusion rates—the ‘ELeCTRiC’ study. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(4):421-425. PubMed

37. Morgenthaler TI, Rodriguez V. Preventing acute care-associated venous thromboembolism in adult and pediatric patients across a large healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(Suppl 2):S15-S21. PubMed

38. Menendez JJ, Verdu C, Calderon B, et al. Incidence and risk factors of superficial and deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(11):2158-2168. PubMed

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Ullman AJ, Cooke M, Kleidon T, Rickard CM. Road map for improvement: point prevalence audit and survey of central venous access devices in paediatric acute care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(2):123-130. PubMed

4. Ullman AJ, Marsh N, Mihala G, Cooke M, Rickard CM. Complications of central venous access devices: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1331-e1344. PubMed

5. Barrier A, Williams DJ, Connelly M, Creech CB. Frequency of peripherally inserted central catheter complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):519-521. PubMed

6. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):429-435. PubMed

7. Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children’s hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001-1008. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

9. Moureau NL, Trick N, Nifong T, et al. Vessel health and preservation (part 1): a new evidence-based approach to vascular access selection and management. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(3):351-356. PubMed

10. Poli P, Scocca A, Di Puccio F, Gallone G, Angelini L, Calabro EM. A comparative study on the mechanical behavior of polyurethane PICCs. J Vasc Access. 2016;17(2):175-181. PubMed

11. Interface Biologics. Surface modification technology platform. 2017. http://www.interfacebiologics.com/endexo.htm. Accessed April 5, 2017.

12. Hoffer EK, Bloch RD, Borsa JJ, Santulli P, Fontaine AB, Francoeur N. Peripherally inserted central catheters with distal versus proximal valves: prospective randomized trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(10):1173-1177. PubMed

13. Hoffer EK, Borsa J, Santulli P, Bloch R, Fontaine AB. Prospective randomized comparison of valved versus nonvalved peripherally inserted central vein catheters. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(5):1393-1398. PubMed

14. Pittiruti M, Emoli A, Porta P, Marche B, DeAngelis R, Scoppettuolo G. A prospective, randomized comparison of three different types of valved and nonvalved peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(6):519-523.

15. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

16. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337. PubMed

17. Kleidon TM, Ullman AJ, Zhang L, Mihala G, Rickard CM. How does your PICCOMPARE? A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing PICC materials in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2017;(under review). PubMed

18. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(2):180-191. PubMed

19. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1. PubMed