User login

ObGyns’ status of Maintenance of Certification now public

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) sets the standards for physician Board Certification. ABMS has begun to publicly report on its Web site (www.CertificationMatters.org) the status of whether ObGyns meet the ABMS Maintenance of Certification® (ABMS MOC®) program requirements established by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG).

There are 24 ABMS Member Boards; 7 began reporting MOC status of the physicians they certify in August 2011, and ABOG is one of 11 boards that began to report MOC status in August 2012. The remaining six ABMS Member Boards expect to make MOC status available by 2014.

The results of a search show the physician’s name, the name of the ABMS Member Board(s) that certify the physician, and a “Yes”, “No,” or “Not Required” response to whether the physician is meeting the MOC requirements of that Member Board. In addition, the physician’s profile contains these features:

- His or her status of all specialty and subspecialty certificates. For example, a physician can be Board Certified in General Obstetrics and Gynecology and the subspecialty of Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

- If a physician became Board Certified before his or her Member Board(s) established their MOC program, and he or she is exempt from participating in MOC, a “Not Required” option is provided. If that physician voluntarily meets the MOC requirements of his or her Member Board(s), the profile will show a “Yes.”

Nearly 800,000 Board Certified physicians voluntarily meet specialty-specific standards beyond what is required for state licensing. Board Certification involves rigorous testing and peer evaluation designed and administered by specialists in a specific medical field. The ABMS MOC program promotes career-long learning, quality improvement activities, and self-assessment. Insurers, hospitals, quality and credentialing organizations, and the federal government recognize ABMS MOC as an important quality marker.

“As the organization that has set the gold standard in physician specialty certification for more than 75 years, this effort further demonstrates ABMS’ commitment to advance quality health care for patients,” said Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA, ABMS President and Chief Executive Officer.

Anyone can visit www.CertificationMatters.org to see if a physician is Board Certified by an ABMS Member Board.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. More doctors to publicly report Maintenance of Certification status in ABMS database [news release]. Chicago, Ill: American Board of Medical Specialties; September 6, 2012. http://www.abms.org/News_and_Events/Media_Newsroom/Releases/release_ABMSDisplayofMOCPRforCredentialers_08212012.aspx. Accessed October 15, 2012.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

<list type="bullet"> <item><para>VTE risk varies by hormone therapy formulation</para></item> <item><para>New molecular cervical cancer test based on NIH’s TERC gene marker</para></item> <item><para>An interview with PAGS course co–chairs Mickey Karram, MD, and Tommaso Falcone, MD</para></item> <item><para>Pregnant women taking antihypertensives—some shown to cause fetal risk—in increasing numbers</para></item> <item><para>Survey: Burnout is widespread among US physicians</para></item> <item><para>UPDATE: CDC publishes final recommendations—baby boomers need a one-time hep C test</para></item> <item><para>Gonorrhea treatment guidelines revised by CDC</para></item> <item><para>Implementation of ICD-10 codes delayed 1 year</para></item> </list>

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) sets the standards for physician Board Certification. ABMS has begun to publicly report on its Web site (www.CertificationMatters.org) the status of whether ObGyns meet the ABMS Maintenance of Certification® (ABMS MOC®) program requirements established by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG).

There are 24 ABMS Member Boards; 7 began reporting MOC status of the physicians they certify in August 2011, and ABOG is one of 11 boards that began to report MOC status in August 2012. The remaining six ABMS Member Boards expect to make MOC status available by 2014.

The results of a search show the physician’s name, the name of the ABMS Member Board(s) that certify the physician, and a “Yes”, “No,” or “Not Required” response to whether the physician is meeting the MOC requirements of that Member Board. In addition, the physician’s profile contains these features:

- His or her status of all specialty and subspecialty certificates. For example, a physician can be Board Certified in General Obstetrics and Gynecology and the subspecialty of Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

- If a physician became Board Certified before his or her Member Board(s) established their MOC program, and he or she is exempt from participating in MOC, a “Not Required” option is provided. If that physician voluntarily meets the MOC requirements of his or her Member Board(s), the profile will show a “Yes.”

Nearly 800,000 Board Certified physicians voluntarily meet specialty-specific standards beyond what is required for state licensing. Board Certification involves rigorous testing and peer evaluation designed and administered by specialists in a specific medical field. The ABMS MOC program promotes career-long learning, quality improvement activities, and self-assessment. Insurers, hospitals, quality and credentialing organizations, and the federal government recognize ABMS MOC as an important quality marker.

“As the organization that has set the gold standard in physician specialty certification for more than 75 years, this effort further demonstrates ABMS’ commitment to advance quality health care for patients,” said Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA, ABMS President and Chief Executive Officer.

Anyone can visit www.CertificationMatters.org to see if a physician is Board Certified by an ABMS Member Board.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) sets the standards for physician Board Certification. ABMS has begun to publicly report on its Web site (www.CertificationMatters.org) the status of whether ObGyns meet the ABMS Maintenance of Certification® (ABMS MOC®) program requirements established by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG).

There are 24 ABMS Member Boards; 7 began reporting MOC status of the physicians they certify in August 2011, and ABOG is one of 11 boards that began to report MOC status in August 2012. The remaining six ABMS Member Boards expect to make MOC status available by 2014.

The results of a search show the physician’s name, the name of the ABMS Member Board(s) that certify the physician, and a “Yes”, “No,” or “Not Required” response to whether the physician is meeting the MOC requirements of that Member Board. In addition, the physician’s profile contains these features:

- His or her status of all specialty and subspecialty certificates. For example, a physician can be Board Certified in General Obstetrics and Gynecology and the subspecialty of Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

- If a physician became Board Certified before his or her Member Board(s) established their MOC program, and he or she is exempt from participating in MOC, a “Not Required” option is provided. If that physician voluntarily meets the MOC requirements of his or her Member Board(s), the profile will show a “Yes.”

Nearly 800,000 Board Certified physicians voluntarily meet specialty-specific standards beyond what is required for state licensing. Board Certification involves rigorous testing and peer evaluation designed and administered by specialists in a specific medical field. The ABMS MOC program promotes career-long learning, quality improvement activities, and self-assessment. Insurers, hospitals, quality and credentialing organizations, and the federal government recognize ABMS MOC as an important quality marker.

“As the organization that has set the gold standard in physician specialty certification for more than 75 years, this effort further demonstrates ABMS’ commitment to advance quality health care for patients,” said Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBA, ABMS President and Chief Executive Officer.

Anyone can visit www.CertificationMatters.org to see if a physician is Board Certified by an ABMS Member Board.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Reference

1. More doctors to publicly report Maintenance of Certification status in ABMS database [news release]. Chicago, Ill: American Board of Medical Specialties; September 6, 2012. http://www.abms.org/News_and_Events/Media_Newsroom/Releases/release_ABMSDisplayofMOCPRforCredentialers_08212012.aspx. Accessed October 15, 2012.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

<list type="bullet"> <item><para>VTE risk varies by hormone therapy formulation</para></item> <item><para>New molecular cervical cancer test based on NIH’s TERC gene marker</para></item> <item><para>An interview with PAGS course co–chairs Mickey Karram, MD, and Tommaso Falcone, MD</para></item> <item><para>Pregnant women taking antihypertensives—some shown to cause fetal risk—in increasing numbers</para></item> <item><para>Survey: Burnout is widespread among US physicians</para></item> <item><para>UPDATE: CDC publishes final recommendations—baby boomers need a one-time hep C test</para></item> <item><para>Gonorrhea treatment guidelines revised by CDC</para></item> <item><para>Implementation of ICD-10 codes delayed 1 year</para></item> </list>

Reference

1. More doctors to publicly report Maintenance of Certification status in ABMS database [news release]. Chicago, Ill: American Board of Medical Specialties; September 6, 2012. http://www.abms.org/News_and_Events/Media_Newsroom/Releases/release_ABMSDisplayofMOCPRforCredentialers_08212012.aspx. Accessed October 15, 2012.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

<list type="bullet"> <item><para>VTE risk varies by hormone therapy formulation</para></item> <item><para>New molecular cervical cancer test based on NIH’s TERC gene marker</para></item> <item><para>An interview with PAGS course co–chairs Mickey Karram, MD, and Tommaso Falcone, MD</para></item> <item><para>Pregnant women taking antihypertensives—some shown to cause fetal risk—in increasing numbers</para></item> <item><para>Survey: Burnout is widespread among US physicians</para></item> <item><para>UPDATE: CDC publishes final recommendations—baby boomers need a one-time hep C test</para></item> <item><para>Gonorrhea treatment guidelines revised by CDC</para></item> <item><para>Implementation of ICD-10 codes delayed 1 year</para></item> </list>

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

(August 2012)

CASE: Adhesions complicate multiple surgeries

In early 2007, a 37-year-old woman with a history of hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, bilateral partial salpingectomy, and cholecystectomy underwent an attempted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for pelvic pain. The operation was converted to laparotomy because of severe adhesions and required several hours to complete.

After the BSO, the patient developed hydronephrosis in her left kidney secondary to an inflammatory cyst. In March 2007, a urologist placed a ureteral stent to relieve the obstruction. One month later, the patient was referred to a gynecologic oncologist for chronic pelvic pain.

On October 29, 2007, the patient underwent operative laparoscopy for adhesiolysis and appendectomy. No retroperitoneal exploration was attempted at the time. According to the operative note, the 10-mm port incision was enlarged to 3 cm to enable the surgeon to inspect the descending colon. Postoperatively, the patient reported persistent abdominal pain and fever and was admitted to the hospital for observation. Although she had a documented temperature of 102°F on October 31, with tachypnea, tachycardia, and a white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.9 x 103/μL, she was discharged home the same day.

The next morning, the patient returned to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) reporting worsening abdominal pain and shortness of breath. Her vital signs included a temperature of 95.8°F, heart rate of 135 bpm, respiration of 32 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 100/68 mm Hg. An examination revealed a tender, distended abdomen, and the patient exhibited guarding behavior upon palpation in all quadrants. Bowel sounds were hypoactive, and the WBC count was 4.2 x 103/μL. No differential count was ordered. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed free air in the abdomen, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema of the abdominal wall and chest wall.

The next day, a differential WBC count revealed bands elevated at a 25% level. A cardiac consultant diagnosed heart failure and remarked that pneumomediastinum should not occur after abdominal surgery. In the evening, the gynecologic oncologist performed a laparotomy and observed enteric contents in the abdominal cavity, as well as a defect of approximately 2 mm in the lower portion of the rectosigmoid colon. According to the operative note, the gynecologic oncologist stapled off the area below the defect and performed a descending loop colostomy.

Postoperatively, the patient remained septic, and vegetable matter was recovered from one of the drains, so a surgical consultant was called. On November 9, a general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy and found necrosis, hemorrhage, acute inflammation of the colostomy, separation of the colostomy from its sutured position on the anterior abdominal wall, and mucosa at the end of the Hartman pouch, necessitating resection of this segment of the colon back to the rectum. Numerous intra-abdominal abscesses were also drained.

Two days later, the patient returned to the OR for further abscess drainage and creation of a left end colostomy. She was discharged 1 month later.

On January 4, 2008, she went to the ER for nausea and abdominal pain. Five days later, a plastic surgeon performed extensive skin grafting on the chronically open abdominal wound. On March 12, the patient returned to the ER because of abdominal pain and was admitted for nasogastric drainage and intravenous (IV) fluids. She returned to the ER again on April 26, reporting pain. A CT scan revealed a cystic mass in the pelvis, which was drained under CT guidance. In June and July, the patient was seen in the ER three times for pain, nausea, and vomiting.

In January 2009, she underwent another laparotomy for takedown of the colostomy, lysis of adhesions, and excision of a left 4-cm pelvic cyst (pathology later revealed the cyst to be ovarian tissue). She also underwent a left-sided myocutaneous flap reconstruction of an abdominal wall defect, and a right-sided myocutaneous flap with placement of a 16 x 20–cm sheet of AlloDerm Tissue Matrix (LifeCell). She continues to experience abdominal pain and visits the ER for that reason. In March 2009, she underwent repeat drainage of a pelvic collection via CT imaging. No further follow-up is available.

Could this catastrophic course have been avoided? What might have prevented it?

Adhesions are likely after any abdominal procedure

The biggest risk factor for laparoscopy-related intestinal injury is the presence of pelvic or abdominal adhesions.1,2 Adhesions inevitably form after any intra-abdominal surgery, and new adhesions are likely with each successive intra-abdominal procedure. Even adhesiolysis leads to the formation of adhesions postoperatively.

Few reliable data suggest that adhesions cause pelvic pain, or that adhesiolysis relieves such pain.3 Furthermore, it may be impossible to predict with reasonable probability where adhesions may be located preoperatively or to know with certainty whether a portion of the intestine is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall directly below the usual subumbilical entry site. Because of the likelihood of adhesions in a patient who has undergone two or more laparotomies, it is risky to thrust a 10- to 12-mm trocar through the anterior abdominal wall below the navel.

A few variables influence the risk of injury

The trocar used in laparoscopic procedures plays a role in the risk of bowel injury. For example, relatively dull reusable devices may push nonfixed intestine away rather than penetrate the viscus. In contrast, razor-sharp disposable devices are more likely to cut into the underlying bowel.

Body habitus is also important. The obese woman is at greater risk for entry injuries, owing to physical aspects of the fatty anterior abdominal wall. When force is applied to the wall, it moves inward, toward the posterior wall, trapping intestine. In a thin woman, the abdominal wall is less elastic, so there is less excursion upon trocar entry.

Intestinal status is another variable to consider. A collapsed bowel is unlikely to be perforated by an entry trocar, whereas a thin, distended bowel is vulnerable to injury. Bowel status can be determined preoperatively using various modalities, including radiographic studies.

Careful surgical technique is imperative. Sharp dissection is always preferable to the blunt tearing of tissue, particularly in cases involving fibrous adhesions. Tearing a dense, unyielding adhesion is likely to remove a piece of intestinal wall because the tensile strength of the adhesion is typically greater than that of the viscus itself.

Thorough knowledge of pelvic anatomy is essential. It would be particularly egregious for a surgeon to mistake an adhesion for the normal peritoneal attachments of the left and sigmoid colon, or to resect the mesentery of the small bowel, believing it to be an adhesion.

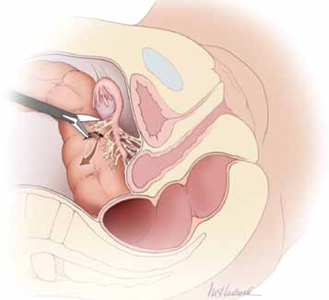

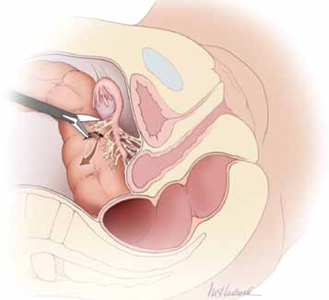

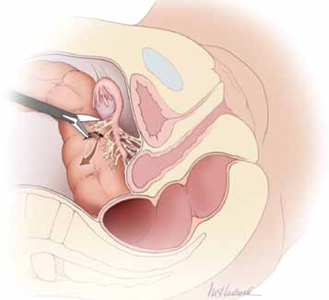

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries (FIGURE 1). Any surgeon who utilizes an energy device is obligated to protect the patient from a thermal injury—and the manufacturers of these instruments should provide reliable data on the safe use of the device, including information about the expected zone of conductive thermal spread based on power density and tissue type. As a general rule, avoid the use of monopolar electrosurgical devices for intra-abdominal dissection.

Adhesiolysis is a risky enterprise. Several studies have found a significant likelihood of bowel injury during lysis of adhesions.4-6 In two studies by Baggish, 94% of adhesiolysis-related injuries involved moderate or severe adhesions.5,6

FIGURE 1 Use of energy devices is risky near bowel

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries. In this figure, the arrow indicates leakage of fecal matter from the bowel defect.

Is laparoscopy the wisest approach?

It is important to weigh the risks of laparoscopy against the potential benefits for the patient. Surgical experience and skill are perhaps the most important variables to consider when deciding on an operative approach. A high volume of laparoscopic operations—performed by a gynecologic surgeon—should translate into a lower risk of injury to intra-abdominal structures.7 That is, the greater the number of cases performed, the lower the risk of injury.

Garry and colleagues conducted two parallel randomized trials comparing 1) laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy and 2) laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy as part of the eVALuate study.8 Laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a significantly higher rate of major complications than abdominal hysterectomy and took longer to perform. No major differences in the rate of complications were found between laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy.

In a review of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries, Brosens and colleagues found significant variations in the complication rate, depending on the experience of the surgeon—a 0.2% rate of access injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.06% for those who had performed more than 100 cases, and a 0.3% rate of operative injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.04% for more experienced surgeons.7

A few precautions can improve the safety of laparoscopy

If adhesions are known or suspected, primary laparoscopic entry should be planned for a site other than the infra-umbilical area. Options include:

- entry via the left hypochondrium in the midclavicular line

- an open procedure.

However, open laparoscopic entry does not always avert intestinal injury.9-11

If the anatomy is obscured once the abdomen has been entered safely, retroperitoneal dissection may be useful, particularly for exposure of the left colon. When it is unclear whether a structure to be incised is a loop of bowel or a distended, adherent oviduct, it is best to refrain from cutting it.

For adhesiolysis, traction and counter-traction are the techniques of choice. Dissection of intestine should always be parallel to the axis of the viscus. Remember, too, that the blood supply enters via the mesenteric margin of the intestine.

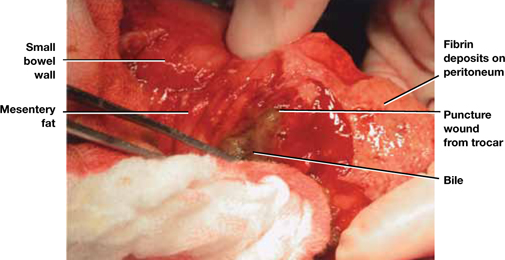

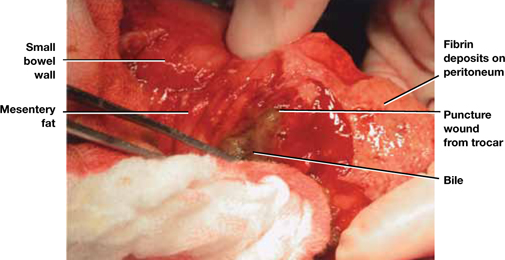

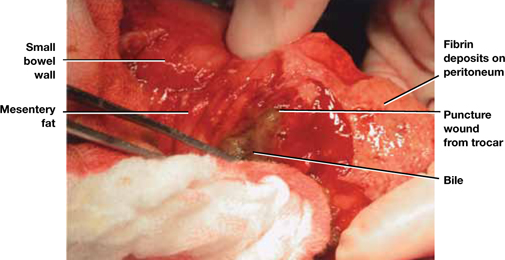

After any dissection involving the intestine, carefully inspect the bowel and describe that inspection in the operative report (FIGURE 2). If injury is suspected, consult a general surgeon and open the abdomen to permit thorough inspection of the intestines.

What the literature reveals about intestinal injury

Several published reports describe a large number of laparoscopic cases and the major attendant complications.12-16 A number of studies have focused on gastrointestinal (GI) complications associated with laparoscopic procedures, providing site-specific data.

Many injuries occur during entry

Vilos reported on 40 bowel injuries, of which 55% occurred during primary trocar entry (19 closed and three open entries).17

In a report on 62 GI injuries in 56 patients, Chapron and colleagues found that one-third occurred during the approach phase of the laparoscopy; they advocated creation of a pneumoperitoneum rather than direct trocar insertion.18

In a report from the Netherlands, 24 of 29 GI injuries occurred during the approach.2

In a review of 63 GI complications related to diagnostic and operative laparoscopy, 75% of injuries were associated with primary trocar insertion.19

Optical access trocars do not appear to be protective against bowel injury. One study of 79 complications associated with these devices found 24 bowel injuries.20

In addition, in two reports detailing 130 cases of small- and large-bowel perforations associated with laparoscopic procedures, Baggish found that 62 (77%) of small-bowel injuries and 20 (41%) of colonic injuries were entry-related.5,6

Energy devices can be problematic

In the study by Chapron and colleagues of 62 GI injuries, six were secondary to the use of electrosurgical devices, four of them involving monopolar instruments.18

In a study from Scotland, 27 of 117 (23%) of bowel injuries during laparoscopic procedures were attributable to a thermal event.21

Baggish found that 43% of operative injuries among 130 intestinal perforations were energy-related.5,6

Intraoperative diagnosis is optimal

Soderstrom reviewed 66 cases of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries and found three deaths attributable to a delay in diagnosis exceeding 72 hours.4

In a study by Vilos, the mean time for diagnosis of bowel injuries was 4 days (range, 0–23 days), with intraoperative diagnosis in only 35.7% of cases.17

In a Finnish nationwide analysis of laparoscopic complications, Harkki-Siren and Kurki found that small-bowel injuries were identified an average of 3.3 days after occurrence; when electrosurgery was involved in the injury, the average time to diagnosis was 4.8 days.22 As for large-bowel injuries, 44% were identified intraoperatively. In the remainder of cases, the average time from injury to diagnosis was 10.4 days for electrosurgical injuries and 1.3 days for injuries related to sharp dissection.

In the studies by Baggish, 82 of 130 (63%) intestinal injuries were diagnosed 48 hours or more after the operation.5,6

Baggish also made the following observations:

- The most common symptoms of intestinal injury were (in order of frequency) abdominal pain, bloating, nausea and vomiting, and fever or chills (or both). The most common signs were abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, diminished bowel sounds, and elevated or subnormal temperature.

- Sepsis was apparent (due to the onset of systemic inflammatory response syndrome) in the majority of small-bowel perforations and virtually all colonic perforations. Findings of tachycardia, tachypnea, elevated leukocyte count, and bandemia suggested sepsis syndrome.

- Radiologically observed free air was often misinterpreted by the radiologist as being consistent with residual gas from the initial laparoscopy. In reality, most—if not all—CO2 gas is absorbed within 24 hours, particularly in obese women. Early CT imaging with oral contrast leads to the most expeditious, correct diagnosis, compared with flat and upright abdominal radiographs.

- Obese women did not exhibit rebound tenderness even though subsequent operative findings revealed extensive and severe peritonitis.

- When infection occurred, it usually was polymicrobial in nature. The most frequently cultured organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, alpha and beta Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Bacteroides.

Baggish concluded that earlier diagnosis could be achieved with careful inspection of the intestine at the conclusion of each operative procedure (FIGURE 2).

Similarly, Chapron and colleagues recommended meticulous inspection of all areas where bowel lysis has been performed. “When there is the slightest doubt, carry out tests for leakage (transanal injection of 200 mL methylene blue using a Foley catheter) in order not to overlook a rectosigmoid injury which would become apparent secondarily in a context of peritonitis,” they wrote. They also suggested that the patient be educated about the signs and symptoms of intestinal injury.18

Whenever a bowel injury is visualized intraoperatively, assume that it is transmural until it is proved otherwise.

FIGURE 2 Meticulous bowel inspection can identify perforation

It is vital to inspect the bowel after any dissection that involves the intestine, being especially alert for puncture wounds caused by a trocar and small tears associated with adhesiolysis.

SOURCE: Baggish MS, Karram MM. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011:1142.

How to avoid urinary tract injuries

Along with major vessel injury and intestinal perforation, bladder and ureteral injuries are the most common complications of laparoscopic surgery. Although urinary tract injuries are rarely fatal, they can cause a range of sequelae, including urinoma, vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas, hydroureter, hydronephrosis, renal damage, and kidney atrophy.

The incidence of ureteral injury during laparoscopy ranges from less than 0.1% to 1.0%, and the incidence of bladder injury ranges from less than 0.8% to 2.0%.23-26 Investigators in Singapore described eight urologic injuries among 485 laparoscopic hysterectomies and identified several risk factors:

- previous cesarean delivery

- multiple fibroids

- severe endometriosis.27

Another set of investigators found a history of laparotomy to be a risk factor for bladder injury during laparoscopic hysterectomy.28

Rooney and colleagues studied the effect of previous cesarean delivery on the risk of injury during hysterectomy.29 Among 5,092 hysterectomies—including 433 laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomies, 3,140 abdominal procedures, and 1,539 vaginal operations—the rate of bladder injury varied by approach. Cystotomy was observed in 0.76% of abdominal hysterectomies (33% had a previous cesarean delivery), 1.3% of vaginal procedures (21% had a previous cesarean), and 1.8% of laparoscopic operations (62.5% had a previous cesarean). The odds ratio for cystotomy during hysterectomy among women with a previous cesarean delivery was 1.26 for the abdominal approach, 3.00 for the vaginal route, and 7.50 for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.29

Two studies highlight common aspects of injury

In a recent report of 75 urinary tract injuries associated with laparoscopic surgery, Baggish identified a total of 33 injuries involving the bladder and 42 of ureteral origin. Twelve of the bladder injuries were associated with the approach, and 21 were related to the surgery. In contrast, only one of the 42 ureteral injuries was related to the approach.30

Baggish also found that just under 50% of urinary tract injuries were related to the use of thermal energy, including all three vesicovaginal fistulas. Fourteen bladder lacerations occurred during separation of the bladder from the uterus during laparoscopic hysterectomy.30

Common sites of injury were at the infundibulopelvic ligament, between the infundibulopelvic ligament and the uterine vessels, and at or below the uterine vessels.30

None of the 42 ureteral injuries were diagnosed intraoperatively. In fact, 37 of these injuries were not correctly diagnosed until more than 48 hours after surgery. Two uterovaginal fistulas were also diagnosed in the late postoperative period.30

Bladder injuries were identified via cystoscopy or cystometrogram or by the instillation of methylene blue into the bladder, with observation from above for leakage. Ureteral injuries were identified by IV pyelogram, retrograde pyelogram, or attempted passage of a stent. Every ureteral injury showed up as hydroureter and hydronephrosis via pyelography.30

Grainger and colleagues reported five ureteral injuries associated with laparoscopic procedures.31 The principal symptoms were low back pain, abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and peritonitis. All five injuries were associated with endometriosis surgery, most commonly near the uterosacral ligaments.

Grainger and colleagues cited eight additional cases of injury. Three patients among the 13 total cases lost renal function, and two eventually required nephrectomy.31

How to prevent, identify, and manage urinary tract injuries

Thorough knowledge of anatomy and meticulous technique are imperative to prevent urinary tract injuries. Strategies include:

- Use sharp rather than blunt dissection.

- Know the risk factors for urinary tract injury, which include previous cesarean delivery or intra-abdominal surgery, presence of adhesions, and deep endometriosis.

- Be aware of the dangers posed by energy devices when they are used near the bladder and ureter. Even bipolar devices can cause thermal injury.

- Employ hydrodissection when there are bladder adhesions, and work nearer the uterus or vagina than the bladder, leaving a margin of tissue.

- When the ureter’s location is unclear relative to the operative site, do not hesitate to open the retroperitoneal space to observe the ureter. If necessary, dissect the ureter distally.

- Perform cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine injection at the conclusion of surgery to ensure that the ureter is not occluded.

- Be aware that peristalsis is not an indication of ureteral integrity. In fact, an obstructed ureter will pulsate more vigorously than a normal one.

- Consider preoperative ureteral catheterization, which may avert injury without increasing operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay,32 although the data are not definitive.33

- Be vigilant. Early identification of injuries reduces morbidity. In the case of ureteral obstruction, immediate stenting will usually obviate the need for ureteral implantation and nephrostomy if the obstruction is not complete.

- Intervene early to cut an obstructing suture or relieve ureteral bowing. Doing so may eliminate the obstruction altogether in many cases.

- If a laceration is found in the bladder trigone or its vicinity, always perform ureteral catheterization to help prevent the inadvertent suturing of the intravesical ureter into the repair.

- After repair of a bladder laceration, perform cystoscopy with IV injection of indigo carmine to ensure ureteral integrity.

- Use only absorbable suture in bladder repairs. I recommend 2-0 chromic catgut for the first layer, which should encompass muscularis and mucosa. Place a second layer of sutures using 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), imbricating the first layer.

- After completion of a bladder repair, instill a solution of diluted methylene blue (1 part methylene blue to 100 parts sterile water or saline) to distend the bladder, and carefully inspect the closure to ensure that it is watertight. Then place a Foley catheter for a minimum of 2 weeks. Four to 6 weeks after repair, perform a cystogram to ensure that healing is complete, with no leakage.

- Call a urologist if you are not well-versed in bladder repair, or if the ureter is injured (or injury is suspected).

- Watch for fistula formation, an inevitable outcome of untreated bladder and ureteral injury, which may occur early or late in the postoperative course.

Choose an approach wisely

Laparoscopy is a learned skill. Supervised practice generally leads to greater levels of proficiency, and repetition of the same operations improves dexterity and execution. However, laparoscopy is also an art—some people have the touch and some do not.

Although laparoscopic techniques offer many advantages, they also have shortcomings. The complications described here, and the strategies I have offered for preventing and managing them, should help gynecologic surgeons determine whether laparoscopy is the optimal route of operation, based on surgical experience, characteristics of the individual patient, and other variables.

Update: Minimally Invasive Surgery

Amy Garcia, MD (April 2012)

10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

(August 2012)

CASE: Adhesions complicate multiple surgeries

In early 2007, a 37-year-old woman with a history of hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, bilateral partial salpingectomy, and cholecystectomy underwent an attempted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for pelvic pain. The operation was converted to laparotomy because of severe adhesions and required several hours to complete.

After the BSO, the patient developed hydronephrosis in her left kidney secondary to an inflammatory cyst. In March 2007, a urologist placed a ureteral stent to relieve the obstruction. One month later, the patient was referred to a gynecologic oncologist for chronic pelvic pain.

On October 29, 2007, the patient underwent operative laparoscopy for adhesiolysis and appendectomy. No retroperitoneal exploration was attempted at the time. According to the operative note, the 10-mm port incision was enlarged to 3 cm to enable the surgeon to inspect the descending colon. Postoperatively, the patient reported persistent abdominal pain and fever and was admitted to the hospital for observation. Although she had a documented temperature of 102°F on October 31, with tachypnea, tachycardia, and a white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.9 x 103/μL, she was discharged home the same day.

The next morning, the patient returned to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) reporting worsening abdominal pain and shortness of breath. Her vital signs included a temperature of 95.8°F, heart rate of 135 bpm, respiration of 32 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 100/68 mm Hg. An examination revealed a tender, distended abdomen, and the patient exhibited guarding behavior upon palpation in all quadrants. Bowel sounds were hypoactive, and the WBC count was 4.2 x 103/μL. No differential count was ordered. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed free air in the abdomen, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema of the abdominal wall and chest wall.

The next day, a differential WBC count revealed bands elevated at a 25% level. A cardiac consultant diagnosed heart failure and remarked that pneumomediastinum should not occur after abdominal surgery. In the evening, the gynecologic oncologist performed a laparotomy and observed enteric contents in the abdominal cavity, as well as a defect of approximately 2 mm in the lower portion of the rectosigmoid colon. According to the operative note, the gynecologic oncologist stapled off the area below the defect and performed a descending loop colostomy.

Postoperatively, the patient remained septic, and vegetable matter was recovered from one of the drains, so a surgical consultant was called. On November 9, a general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy and found necrosis, hemorrhage, acute inflammation of the colostomy, separation of the colostomy from its sutured position on the anterior abdominal wall, and mucosa at the end of the Hartman pouch, necessitating resection of this segment of the colon back to the rectum. Numerous intra-abdominal abscesses were also drained.

Two days later, the patient returned to the OR for further abscess drainage and creation of a left end colostomy. She was discharged 1 month later.

On January 4, 2008, she went to the ER for nausea and abdominal pain. Five days later, a plastic surgeon performed extensive skin grafting on the chronically open abdominal wound. On March 12, the patient returned to the ER because of abdominal pain and was admitted for nasogastric drainage and intravenous (IV) fluids. She returned to the ER again on April 26, reporting pain. A CT scan revealed a cystic mass in the pelvis, which was drained under CT guidance. In June and July, the patient was seen in the ER three times for pain, nausea, and vomiting.

In January 2009, she underwent another laparotomy for takedown of the colostomy, lysis of adhesions, and excision of a left 4-cm pelvic cyst (pathology later revealed the cyst to be ovarian tissue). She also underwent a left-sided myocutaneous flap reconstruction of an abdominal wall defect, and a right-sided myocutaneous flap with placement of a 16 x 20–cm sheet of AlloDerm Tissue Matrix (LifeCell). She continues to experience abdominal pain and visits the ER for that reason. In March 2009, she underwent repeat drainage of a pelvic collection via CT imaging. No further follow-up is available.

Could this catastrophic course have been avoided? What might have prevented it?

Adhesions are likely after any abdominal procedure

The biggest risk factor for laparoscopy-related intestinal injury is the presence of pelvic or abdominal adhesions.1,2 Adhesions inevitably form after any intra-abdominal surgery, and new adhesions are likely with each successive intra-abdominal procedure. Even adhesiolysis leads to the formation of adhesions postoperatively.

Few reliable data suggest that adhesions cause pelvic pain, or that adhesiolysis relieves such pain.3 Furthermore, it may be impossible to predict with reasonable probability where adhesions may be located preoperatively or to know with certainty whether a portion of the intestine is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall directly below the usual subumbilical entry site. Because of the likelihood of adhesions in a patient who has undergone two or more laparotomies, it is risky to thrust a 10- to 12-mm trocar through the anterior abdominal wall below the navel.

A few variables influence the risk of injury

The trocar used in laparoscopic procedures plays a role in the risk of bowel injury. For example, relatively dull reusable devices may push nonfixed intestine away rather than penetrate the viscus. In contrast, razor-sharp disposable devices are more likely to cut into the underlying bowel.

Body habitus is also important. The obese woman is at greater risk for entry injuries, owing to physical aspects of the fatty anterior abdominal wall. When force is applied to the wall, it moves inward, toward the posterior wall, trapping intestine. In a thin woman, the abdominal wall is less elastic, so there is less excursion upon trocar entry.

Intestinal status is another variable to consider. A collapsed bowel is unlikely to be perforated by an entry trocar, whereas a thin, distended bowel is vulnerable to injury. Bowel status can be determined preoperatively using various modalities, including radiographic studies.

Careful surgical technique is imperative. Sharp dissection is always preferable to the blunt tearing of tissue, particularly in cases involving fibrous adhesions. Tearing a dense, unyielding adhesion is likely to remove a piece of intestinal wall because the tensile strength of the adhesion is typically greater than that of the viscus itself.

Thorough knowledge of pelvic anatomy is essential. It would be particularly egregious for a surgeon to mistake an adhesion for the normal peritoneal attachments of the left and sigmoid colon, or to resect the mesentery of the small bowel, believing it to be an adhesion.

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries (FIGURE 1). Any surgeon who utilizes an energy device is obligated to protect the patient from a thermal injury—and the manufacturers of these instruments should provide reliable data on the safe use of the device, including information about the expected zone of conductive thermal spread based on power density and tissue type. As a general rule, avoid the use of monopolar electrosurgical devices for intra-abdominal dissection.

Adhesiolysis is a risky enterprise. Several studies have found a significant likelihood of bowel injury during lysis of adhesions.4-6 In two studies by Baggish, 94% of adhesiolysis-related injuries involved moderate or severe adhesions.5,6

FIGURE 1 Use of energy devices is risky near bowel

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries. In this figure, the arrow indicates leakage of fecal matter from the bowel defect.

Is laparoscopy the wisest approach?

It is important to weigh the risks of laparoscopy against the potential benefits for the patient. Surgical experience and skill are perhaps the most important variables to consider when deciding on an operative approach. A high volume of laparoscopic operations—performed by a gynecologic surgeon—should translate into a lower risk of injury to intra-abdominal structures.7 That is, the greater the number of cases performed, the lower the risk of injury.

Garry and colleagues conducted two parallel randomized trials comparing 1) laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy and 2) laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy as part of the eVALuate study.8 Laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a significantly higher rate of major complications than abdominal hysterectomy and took longer to perform. No major differences in the rate of complications were found between laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy.

In a review of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries, Brosens and colleagues found significant variations in the complication rate, depending on the experience of the surgeon—a 0.2% rate of access injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.06% for those who had performed more than 100 cases, and a 0.3% rate of operative injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.04% for more experienced surgeons.7

A few precautions can improve the safety of laparoscopy

If adhesions are known or suspected, primary laparoscopic entry should be planned for a site other than the infra-umbilical area. Options include:

- entry via the left hypochondrium in the midclavicular line

- an open procedure.

However, open laparoscopic entry does not always avert intestinal injury.9-11

If the anatomy is obscured once the abdomen has been entered safely, retroperitoneal dissection may be useful, particularly for exposure of the left colon. When it is unclear whether a structure to be incised is a loop of bowel or a distended, adherent oviduct, it is best to refrain from cutting it.

For adhesiolysis, traction and counter-traction are the techniques of choice. Dissection of intestine should always be parallel to the axis of the viscus. Remember, too, that the blood supply enters via the mesenteric margin of the intestine.

After any dissection involving the intestine, carefully inspect the bowel and describe that inspection in the operative report (FIGURE 2). If injury is suspected, consult a general surgeon and open the abdomen to permit thorough inspection of the intestines.

What the literature reveals about intestinal injury

Several published reports describe a large number of laparoscopic cases and the major attendant complications.12-16 A number of studies have focused on gastrointestinal (GI) complications associated with laparoscopic procedures, providing site-specific data.

Many injuries occur during entry

Vilos reported on 40 bowel injuries, of which 55% occurred during primary trocar entry (19 closed and three open entries).17

In a report on 62 GI injuries in 56 patients, Chapron and colleagues found that one-third occurred during the approach phase of the laparoscopy; they advocated creation of a pneumoperitoneum rather than direct trocar insertion.18

In a report from the Netherlands, 24 of 29 GI injuries occurred during the approach.2

In a review of 63 GI complications related to diagnostic and operative laparoscopy, 75% of injuries were associated with primary trocar insertion.19

Optical access trocars do not appear to be protective against bowel injury. One study of 79 complications associated with these devices found 24 bowel injuries.20

In addition, in two reports detailing 130 cases of small- and large-bowel perforations associated with laparoscopic procedures, Baggish found that 62 (77%) of small-bowel injuries and 20 (41%) of colonic injuries were entry-related.5,6

Energy devices can be problematic

In the study by Chapron and colleagues of 62 GI injuries, six were secondary to the use of electrosurgical devices, four of them involving monopolar instruments.18

In a study from Scotland, 27 of 117 (23%) of bowel injuries during laparoscopic procedures were attributable to a thermal event.21

Baggish found that 43% of operative injuries among 130 intestinal perforations were energy-related.5,6

Intraoperative diagnosis is optimal

Soderstrom reviewed 66 cases of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries and found three deaths attributable to a delay in diagnosis exceeding 72 hours.4

In a study by Vilos, the mean time for diagnosis of bowel injuries was 4 days (range, 0–23 days), with intraoperative diagnosis in only 35.7% of cases.17

In a Finnish nationwide analysis of laparoscopic complications, Harkki-Siren and Kurki found that small-bowel injuries were identified an average of 3.3 days after occurrence; when electrosurgery was involved in the injury, the average time to diagnosis was 4.8 days.22 As for large-bowel injuries, 44% were identified intraoperatively. In the remainder of cases, the average time from injury to diagnosis was 10.4 days for electrosurgical injuries and 1.3 days for injuries related to sharp dissection.

In the studies by Baggish, 82 of 130 (63%) intestinal injuries were diagnosed 48 hours or more after the operation.5,6

Baggish also made the following observations:

- The most common symptoms of intestinal injury were (in order of frequency) abdominal pain, bloating, nausea and vomiting, and fever or chills (or both). The most common signs were abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, diminished bowel sounds, and elevated or subnormal temperature.

- Sepsis was apparent (due to the onset of systemic inflammatory response syndrome) in the majority of small-bowel perforations and virtually all colonic perforations. Findings of tachycardia, tachypnea, elevated leukocyte count, and bandemia suggested sepsis syndrome.

- Radiologically observed free air was often misinterpreted by the radiologist as being consistent with residual gas from the initial laparoscopy. In reality, most—if not all—CO2 gas is absorbed within 24 hours, particularly in obese women. Early CT imaging with oral contrast leads to the most expeditious, correct diagnosis, compared with flat and upright abdominal radiographs.

- Obese women did not exhibit rebound tenderness even though subsequent operative findings revealed extensive and severe peritonitis.

- When infection occurred, it usually was polymicrobial in nature. The most frequently cultured organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, alpha and beta Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Bacteroides.

Baggish concluded that earlier diagnosis could be achieved with careful inspection of the intestine at the conclusion of each operative procedure (FIGURE 2).

Similarly, Chapron and colleagues recommended meticulous inspection of all areas where bowel lysis has been performed. “When there is the slightest doubt, carry out tests for leakage (transanal injection of 200 mL methylene blue using a Foley catheter) in order not to overlook a rectosigmoid injury which would become apparent secondarily in a context of peritonitis,” they wrote. They also suggested that the patient be educated about the signs and symptoms of intestinal injury.18

Whenever a bowel injury is visualized intraoperatively, assume that it is transmural until it is proved otherwise.

FIGURE 2 Meticulous bowel inspection can identify perforation

It is vital to inspect the bowel after any dissection that involves the intestine, being especially alert for puncture wounds caused by a trocar and small tears associated with adhesiolysis.

SOURCE: Baggish MS, Karram MM. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011:1142.

How to avoid urinary tract injuries

Along with major vessel injury and intestinal perforation, bladder and ureteral injuries are the most common complications of laparoscopic surgery. Although urinary tract injuries are rarely fatal, they can cause a range of sequelae, including urinoma, vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas, hydroureter, hydronephrosis, renal damage, and kidney atrophy.

The incidence of ureteral injury during laparoscopy ranges from less than 0.1% to 1.0%, and the incidence of bladder injury ranges from less than 0.8% to 2.0%.23-26 Investigators in Singapore described eight urologic injuries among 485 laparoscopic hysterectomies and identified several risk factors:

- previous cesarean delivery

- multiple fibroids

- severe endometriosis.27

Another set of investigators found a history of laparotomy to be a risk factor for bladder injury during laparoscopic hysterectomy.28

Rooney and colleagues studied the effect of previous cesarean delivery on the risk of injury during hysterectomy.29 Among 5,092 hysterectomies—including 433 laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomies, 3,140 abdominal procedures, and 1,539 vaginal operations—the rate of bladder injury varied by approach. Cystotomy was observed in 0.76% of abdominal hysterectomies (33% had a previous cesarean delivery), 1.3% of vaginal procedures (21% had a previous cesarean), and 1.8% of laparoscopic operations (62.5% had a previous cesarean). The odds ratio for cystotomy during hysterectomy among women with a previous cesarean delivery was 1.26 for the abdominal approach, 3.00 for the vaginal route, and 7.50 for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.29

Two studies highlight common aspects of injury

In a recent report of 75 urinary tract injuries associated with laparoscopic surgery, Baggish identified a total of 33 injuries involving the bladder and 42 of ureteral origin. Twelve of the bladder injuries were associated with the approach, and 21 were related to the surgery. In contrast, only one of the 42 ureteral injuries was related to the approach.30

Baggish also found that just under 50% of urinary tract injuries were related to the use of thermal energy, including all three vesicovaginal fistulas. Fourteen bladder lacerations occurred during separation of the bladder from the uterus during laparoscopic hysterectomy.30

Common sites of injury were at the infundibulopelvic ligament, between the infundibulopelvic ligament and the uterine vessels, and at or below the uterine vessels.30

None of the 42 ureteral injuries were diagnosed intraoperatively. In fact, 37 of these injuries were not correctly diagnosed until more than 48 hours after surgery. Two uterovaginal fistulas were also diagnosed in the late postoperative period.30

Bladder injuries were identified via cystoscopy or cystometrogram or by the instillation of methylene blue into the bladder, with observation from above for leakage. Ureteral injuries were identified by IV pyelogram, retrograde pyelogram, or attempted passage of a stent. Every ureteral injury showed up as hydroureter and hydronephrosis via pyelography.30

Grainger and colleagues reported five ureteral injuries associated with laparoscopic procedures.31 The principal symptoms were low back pain, abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and peritonitis. All five injuries were associated with endometriosis surgery, most commonly near the uterosacral ligaments.

Grainger and colleagues cited eight additional cases of injury. Three patients among the 13 total cases lost renal function, and two eventually required nephrectomy.31

How to prevent, identify, and manage urinary tract injuries

Thorough knowledge of anatomy and meticulous technique are imperative to prevent urinary tract injuries. Strategies include:

- Use sharp rather than blunt dissection.

- Know the risk factors for urinary tract injury, which include previous cesarean delivery or intra-abdominal surgery, presence of adhesions, and deep endometriosis.

- Be aware of the dangers posed by energy devices when they are used near the bladder and ureter. Even bipolar devices can cause thermal injury.

- Employ hydrodissection when there are bladder adhesions, and work nearer the uterus or vagina than the bladder, leaving a margin of tissue.

- When the ureter’s location is unclear relative to the operative site, do not hesitate to open the retroperitoneal space to observe the ureter. If necessary, dissect the ureter distally.

- Perform cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine injection at the conclusion of surgery to ensure that the ureter is not occluded.

- Be aware that peristalsis is not an indication of ureteral integrity. In fact, an obstructed ureter will pulsate more vigorously than a normal one.

- Consider preoperative ureteral catheterization, which may avert injury without increasing operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay,32 although the data are not definitive.33

- Be vigilant. Early identification of injuries reduces morbidity. In the case of ureteral obstruction, immediate stenting will usually obviate the need for ureteral implantation and nephrostomy if the obstruction is not complete.

- Intervene early to cut an obstructing suture or relieve ureteral bowing. Doing so may eliminate the obstruction altogether in many cases.

- If a laceration is found in the bladder trigone or its vicinity, always perform ureteral catheterization to help prevent the inadvertent suturing of the intravesical ureter into the repair.

- After repair of a bladder laceration, perform cystoscopy with IV injection of indigo carmine to ensure ureteral integrity.

- Use only absorbable suture in bladder repairs. I recommend 2-0 chromic catgut for the first layer, which should encompass muscularis and mucosa. Place a second layer of sutures using 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), imbricating the first layer.

- After completion of a bladder repair, instill a solution of diluted methylene blue (1 part methylene blue to 100 parts sterile water or saline) to distend the bladder, and carefully inspect the closure to ensure that it is watertight. Then place a Foley catheter for a minimum of 2 weeks. Four to 6 weeks after repair, perform a cystogram to ensure that healing is complete, with no leakage.

- Call a urologist if you are not well-versed in bladder repair, or if the ureter is injured (or injury is suspected).

- Watch for fistula formation, an inevitable outcome of untreated bladder and ureteral injury, which may occur early or late in the postoperative course.

Choose an approach wisely

Laparoscopy is a learned skill. Supervised practice generally leads to greater levels of proficiency, and repetition of the same operations improves dexterity and execution. However, laparoscopy is also an art—some people have the touch and some do not.

Although laparoscopic techniques offer many advantages, they also have shortcomings. The complications described here, and the strategies I have offered for preventing and managing them, should help gynecologic surgeons determine whether laparoscopy is the optimal route of operation, based on surgical experience, characteristics of the individual patient, and other variables.

Update: Minimally Invasive Surgery

Amy Garcia, MD (April 2012)

10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

(August 2012)

CASE: Adhesions complicate multiple surgeries

In early 2007, a 37-year-old woman with a history of hysterectomy, adhesiolysis, bilateral partial salpingectomy, and cholecystectomy underwent an attempted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for pelvic pain. The operation was converted to laparotomy because of severe adhesions and required several hours to complete.

After the BSO, the patient developed hydronephrosis in her left kidney secondary to an inflammatory cyst. In March 2007, a urologist placed a ureteral stent to relieve the obstruction. One month later, the patient was referred to a gynecologic oncologist for chronic pelvic pain.

On October 29, 2007, the patient underwent operative laparoscopy for adhesiolysis and appendectomy. No retroperitoneal exploration was attempted at the time. According to the operative note, the 10-mm port incision was enlarged to 3 cm to enable the surgeon to inspect the descending colon. Postoperatively, the patient reported persistent abdominal pain and fever and was admitted to the hospital for observation. Although she had a documented temperature of 102°F on October 31, with tachypnea, tachycardia, and a white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.9 x 103/μL, she was discharged home the same day.

The next morning, the patient returned to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) reporting worsening abdominal pain and shortness of breath. Her vital signs included a temperature of 95.8°F, heart rate of 135 bpm, respiration of 32 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 100/68 mm Hg. An examination revealed a tender, distended abdomen, and the patient exhibited guarding behavior upon palpation in all quadrants. Bowel sounds were hypoactive, and the WBC count was 4.2 x 103/μL. No differential count was ordered. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed free air in the abdomen, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema of the abdominal wall and chest wall.

The next day, a differential WBC count revealed bands elevated at a 25% level. A cardiac consultant diagnosed heart failure and remarked that pneumomediastinum should not occur after abdominal surgery. In the evening, the gynecologic oncologist performed a laparotomy and observed enteric contents in the abdominal cavity, as well as a defect of approximately 2 mm in the lower portion of the rectosigmoid colon. According to the operative note, the gynecologic oncologist stapled off the area below the defect and performed a descending loop colostomy.

Postoperatively, the patient remained septic, and vegetable matter was recovered from one of the drains, so a surgical consultant was called. On November 9, a general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy and found necrosis, hemorrhage, acute inflammation of the colostomy, separation of the colostomy from its sutured position on the anterior abdominal wall, and mucosa at the end of the Hartman pouch, necessitating resection of this segment of the colon back to the rectum. Numerous intra-abdominal abscesses were also drained.

Two days later, the patient returned to the OR for further abscess drainage and creation of a left end colostomy. She was discharged 1 month later.

On January 4, 2008, she went to the ER for nausea and abdominal pain. Five days later, a plastic surgeon performed extensive skin grafting on the chronically open abdominal wound. On March 12, the patient returned to the ER because of abdominal pain and was admitted for nasogastric drainage and intravenous (IV) fluids. She returned to the ER again on April 26, reporting pain. A CT scan revealed a cystic mass in the pelvis, which was drained under CT guidance. In June and July, the patient was seen in the ER three times for pain, nausea, and vomiting.

In January 2009, she underwent another laparotomy for takedown of the colostomy, lysis of adhesions, and excision of a left 4-cm pelvic cyst (pathology later revealed the cyst to be ovarian tissue). She also underwent a left-sided myocutaneous flap reconstruction of an abdominal wall defect, and a right-sided myocutaneous flap with placement of a 16 x 20–cm sheet of AlloDerm Tissue Matrix (LifeCell). She continues to experience abdominal pain and visits the ER for that reason. In March 2009, she underwent repeat drainage of a pelvic collection via CT imaging. No further follow-up is available.

Could this catastrophic course have been avoided? What might have prevented it?

Adhesions are likely after any abdominal procedure

The biggest risk factor for laparoscopy-related intestinal injury is the presence of pelvic or abdominal adhesions.1,2 Adhesions inevitably form after any intra-abdominal surgery, and new adhesions are likely with each successive intra-abdominal procedure. Even adhesiolysis leads to the formation of adhesions postoperatively.

Few reliable data suggest that adhesions cause pelvic pain, or that adhesiolysis relieves such pain.3 Furthermore, it may be impossible to predict with reasonable probability where adhesions may be located preoperatively or to know with certainty whether a portion of the intestine is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall directly below the usual subumbilical entry site. Because of the likelihood of adhesions in a patient who has undergone two or more laparotomies, it is risky to thrust a 10- to 12-mm trocar through the anterior abdominal wall below the navel.

A few variables influence the risk of injury

The trocar used in laparoscopic procedures plays a role in the risk of bowel injury. For example, relatively dull reusable devices may push nonfixed intestine away rather than penetrate the viscus. In contrast, razor-sharp disposable devices are more likely to cut into the underlying bowel.

Body habitus is also important. The obese woman is at greater risk for entry injuries, owing to physical aspects of the fatty anterior abdominal wall. When force is applied to the wall, it moves inward, toward the posterior wall, trapping intestine. In a thin woman, the abdominal wall is less elastic, so there is less excursion upon trocar entry.

Intestinal status is another variable to consider. A collapsed bowel is unlikely to be perforated by an entry trocar, whereas a thin, distended bowel is vulnerable to injury. Bowel status can be determined preoperatively using various modalities, including radiographic studies.

Careful surgical technique is imperative. Sharp dissection is always preferable to the blunt tearing of tissue, particularly in cases involving fibrous adhesions. Tearing a dense, unyielding adhesion is likely to remove a piece of intestinal wall because the tensile strength of the adhesion is typically greater than that of the viscus itself.

Thorough knowledge of pelvic anatomy is essential. It would be particularly egregious for a surgeon to mistake an adhesion for the normal peritoneal attachments of the left and sigmoid colon, or to resect the mesentery of the small bowel, believing it to be an adhesion.

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries (FIGURE 1). Any surgeon who utilizes an energy device is obligated to protect the patient from a thermal injury—and the manufacturers of these instruments should provide reliable data on the safe use of the device, including information about the expected zone of conductive thermal spread based on power density and tissue type. As a general rule, avoid the use of monopolar electrosurgical devices for intra-abdominal dissection.

Adhesiolysis is a risky enterprise. Several studies have found a significant likelihood of bowel injury during lysis of adhesions.4-6 In two studies by Baggish, 94% of adhesiolysis-related injuries involved moderate or severe adhesions.5,6

FIGURE 1 Use of energy devices is risky near bowel

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries. In this figure, the arrow indicates leakage of fecal matter from the bowel defect.

Is laparoscopy the wisest approach?

It is important to weigh the risks of laparoscopy against the potential benefits for the patient. Surgical experience and skill are perhaps the most important variables to consider when deciding on an operative approach. A high volume of laparoscopic operations—performed by a gynecologic surgeon—should translate into a lower risk of injury to intra-abdominal structures.7 That is, the greater the number of cases performed, the lower the risk of injury.

Garry and colleagues conducted two parallel randomized trials comparing 1) laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy and 2) laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy as part of the eVALuate study.8 Laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a significantly higher rate of major complications than abdominal hysterectomy and took longer to perform. No major differences in the rate of complications were found between laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy.

In a review of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries, Brosens and colleagues found significant variations in the complication rate, depending on the experience of the surgeon—a 0.2% rate of access injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.06% for those who had performed more than 100 cases, and a 0.3% rate of operative injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.04% for more experienced surgeons.7

A few precautions can improve the safety of laparoscopy

If adhesions are known or suspected, primary laparoscopic entry should be planned for a site other than the infra-umbilical area. Options include:

- entry via the left hypochondrium in the midclavicular line

- an open procedure.

However, open laparoscopic entry does not always avert intestinal injury.9-11

If the anatomy is obscured once the abdomen has been entered safely, retroperitoneal dissection may be useful, particularly for exposure of the left colon. When it is unclear whether a structure to be incised is a loop of bowel or a distended, adherent oviduct, it is best to refrain from cutting it.

For adhesiolysis, traction and counter-traction are the techniques of choice. Dissection of intestine should always be parallel to the axis of the viscus. Remember, too, that the blood supply enters via the mesenteric margin of the intestine.

After any dissection involving the intestine, carefully inspect the bowel and describe that inspection in the operative report (FIGURE 2). If injury is suspected, consult a general surgeon and open the abdomen to permit thorough inspection of the intestines.

What the literature reveals about intestinal injury

Several published reports describe a large number of laparoscopic cases and the major attendant complications.12-16 A number of studies have focused on gastrointestinal (GI) complications associated with laparoscopic procedures, providing site-specific data.

Many injuries occur during entry

Vilos reported on 40 bowel injuries, of which 55% occurred during primary trocar entry (19 closed and three open entries).17

In a report on 62 GI injuries in 56 patients, Chapron and colleagues found that one-third occurred during the approach phase of the laparoscopy; they advocated creation of a pneumoperitoneum rather than direct trocar insertion.18

In a report from the Netherlands, 24 of 29 GI injuries occurred during the approach.2

In a review of 63 GI complications related to diagnostic and operative laparoscopy, 75% of injuries were associated with primary trocar insertion.19

Optical access trocars do not appear to be protective against bowel injury. One study of 79 complications associated with these devices found 24 bowel injuries.20

In addition, in two reports detailing 130 cases of small- and large-bowel perforations associated with laparoscopic procedures, Baggish found that 62 (77%) of small-bowel injuries and 20 (41%) of colonic injuries were entry-related.5,6

Energy devices can be problematic

In the study by Chapron and colleagues of 62 GI injuries, six were secondary to the use of electrosurgical devices, four of them involving monopolar instruments.18

In a study from Scotland, 27 of 117 (23%) of bowel injuries during laparoscopic procedures were attributable to a thermal event.21

Baggish found that 43% of operative injuries among 130 intestinal perforations were energy-related.5,6

Intraoperative diagnosis is optimal

Soderstrom reviewed 66 cases of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries and found three deaths attributable to a delay in diagnosis exceeding 72 hours.4

In a study by Vilos, the mean time for diagnosis of bowel injuries was 4 days (range, 0–23 days), with intraoperative diagnosis in only 35.7% of cases.17

In a Finnish nationwide analysis of laparoscopic complications, Harkki-Siren and Kurki found that small-bowel injuries were identified an average of 3.3 days after occurrence; when electrosurgery was involved in the injury, the average time to diagnosis was 4.8 days.22 As for large-bowel injuries, 44% were identified intraoperatively. In the remainder of cases, the average time from injury to diagnosis was 10.4 days for electrosurgical injuries and 1.3 days for injuries related to sharp dissection.

In the studies by Baggish, 82 of 130 (63%) intestinal injuries were diagnosed 48 hours or more after the operation.5,6

Baggish also made the following observations:

- The most common symptoms of intestinal injury were (in order of frequency) abdominal pain, bloating, nausea and vomiting, and fever or chills (or both). The most common signs were abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, diminished bowel sounds, and elevated or subnormal temperature.

- Sepsis was apparent (due to the onset of systemic inflammatory response syndrome) in the majority of small-bowel perforations and virtually all colonic perforations. Findings of tachycardia, tachypnea, elevated leukocyte count, and bandemia suggested sepsis syndrome.

- Radiologically observed free air was often misinterpreted by the radiologist as being consistent with residual gas from the initial laparoscopy. In reality, most—if not all—CO2 gas is absorbed within 24 hours, particularly in obese women. Early CT imaging with oral contrast leads to the most expeditious, correct diagnosis, compared with flat and upright abdominal radiographs.

- Obese women did not exhibit rebound tenderness even though subsequent operative findings revealed extensive and severe peritonitis.

- When infection occurred, it usually was polymicrobial in nature. The most frequently cultured organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, alpha and beta Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Bacteroides.

Baggish concluded that earlier diagnosis could be achieved with careful inspection of the intestine at the conclusion of each operative procedure (FIGURE 2).

Similarly, Chapron and colleagues recommended meticulous inspection of all areas where bowel lysis has been performed. “When there is the slightest doubt, carry out tests for leakage (transanal injection of 200 mL methylene blue using a Foley catheter) in order not to overlook a rectosigmoid injury which would become apparent secondarily in a context of peritonitis,” they wrote. They also suggested that the patient be educated about the signs and symptoms of intestinal injury.18

Whenever a bowel injury is visualized intraoperatively, assume that it is transmural until it is proved otherwise.

FIGURE 2 Meticulous bowel inspection can identify perforation

It is vital to inspect the bowel after any dissection that involves the intestine, being especially alert for puncture wounds caused by a trocar and small tears associated with adhesiolysis.

SOURCE: Baggish MS, Karram MM. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011:1142.

How to avoid urinary tract injuries

Along with major vessel injury and intestinal perforation, bladder and ureteral injuries are the most common complications of laparoscopic surgery. Although urinary tract injuries are rarely fatal, they can cause a range of sequelae, including urinoma, vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas, hydroureter, hydronephrosis, renal damage, and kidney atrophy.

The incidence of ureteral injury during laparoscopy ranges from less than 0.1% to 1.0%, and the incidence of bladder injury ranges from less than 0.8% to 2.0%.23-26 Investigators in Singapore described eight urologic injuries among 485 laparoscopic hysterectomies and identified several risk factors:

- previous cesarean delivery

- multiple fibroids

- severe endometriosis.27

Another set of investigators found a history of laparotomy to be a risk factor for bladder injury during laparoscopic hysterectomy.28

Rooney and colleagues studied the effect of previous cesarean delivery on the risk of injury during hysterectomy.29 Among 5,092 hysterectomies—including 433 laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomies, 3,140 abdominal procedures, and 1,539 vaginal operations—the rate of bladder injury varied by approach. Cystotomy was observed in 0.76% of abdominal hysterectomies (33% had a previous cesarean delivery), 1.3% of vaginal procedures (21% had a previous cesarean), and 1.8% of laparoscopic operations (62.5% had a previous cesarean). The odds ratio for cystotomy during hysterectomy among women with a previous cesarean delivery was 1.26 for the abdominal approach, 3.00 for the vaginal route, and 7.50 for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.29

Two studies highlight common aspects of injury

In a recent report of 75 urinary tract injuries associated with laparoscopic surgery, Baggish identified a total of 33 injuries involving the bladder and 42 of ureteral origin. Twelve of the bladder injuries were associated with the approach, and 21 were related to the surgery. In contrast, only one of the 42 ureteral injuries was related to the approach.30

Baggish also found that just under 50% of urinary tract injuries were related to the use of thermal energy, including all three vesicovaginal fistulas. Fourteen bladder lacerations occurred during separation of the bladder from the uterus during laparoscopic hysterectomy.30

Common sites of injury were at the infundibulopelvic ligament, between the infundibulopelvic ligament and the uterine vessels, and at or below the uterine vessels.30

None of the 42 ureteral injuries were diagnosed intraoperatively. In fact, 37 of these injuries were not correctly diagnosed until more than 48 hours after surgery. Two uterovaginal fistulas were also diagnosed in the late postoperative period.30

Bladder injuries were identified via cystoscopy or cystometrogram or by the instillation of methylene blue into the bladder, with observation from above for leakage. Ureteral injuries were identified by IV pyelogram, retrograde pyelogram, or attempted passage of a stent. Every ureteral injury showed up as hydroureter and hydronephrosis via pyelography.30

Grainger and colleagues reported five ureteral injuries associated with laparoscopic procedures.31 The principal symptoms were low back pain, abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and peritonitis. All five injuries were associated with endometriosis surgery, most commonly near the uterosacral ligaments.

Grainger and colleagues cited eight additional cases of injury. Three patients among the 13 total cases lost renal function, and two eventually required nephrectomy.31

How to prevent, identify, and manage urinary tract injuries

Thorough knowledge of anatomy and meticulous technique are imperative to prevent urinary tract injuries. Strategies include:

- Use sharp rather than blunt dissection.

- Know the risk factors for urinary tract injury, which include previous cesarean delivery or intra-abdominal surgery, presence of adhesions, and deep endometriosis.

- Be aware of the dangers posed by energy devices when they are used near the bladder and ureter. Even bipolar devices can cause thermal injury.

- Employ hydrodissection when there are bladder adhesions, and work nearer the uterus or vagina than the bladder, leaving a margin of tissue.

- When the ureter’s location is unclear relative to the operative site, do not hesitate to open the retroperitoneal space to observe the ureter. If necessary, dissect the ureter distally.

- Perform cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine injection at the conclusion of surgery to ensure that the ureter is not occluded.

- Be aware that peristalsis is not an indication of ureteral integrity. In fact, an obstructed ureter will pulsate more vigorously than a normal one.

- Consider preoperative ureteral catheterization, which may avert injury without increasing operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay,32 although the data are not definitive.33

- Be vigilant. Early identification of injuries reduces morbidity. In the case of ureteral obstruction, immediate stenting will usually obviate the need for ureteral implantation and nephrostomy if the obstruction is not complete.

- Intervene early to cut an obstructing suture or relieve ureteral bowing. Doing so may eliminate the obstruction altogether in many cases.