User login

Progressive, pruritic eruption of firm, skin-colored papules

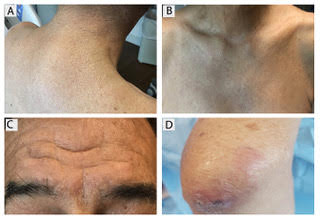

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Pink scaly rash on torso and extremities

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

A 17-year-old male with a history of Crohn's disease, well controlled on infliximab, is seen for evaluation of a pink scaly rash on the torso, upper extremities, and lower extremities. The rash began 5 months previously and has been mostly asymptomatic. The patient denies pruritus or pain at the affected areas. There is no fever or drainage from any of the sites. The patient has not undergone any treatments. He does not have a personal or family history of chronic skin conditions.

On physical exam, he is noted to have numerous pink papules and plaques with overlying scale on his trunk, as well as the dorsal aspects of bilateral hands and the plantar surfaces of bilateral feet. His skin is otherwise unremarkable.

Asymptomatic hypopigmented macules and patches

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

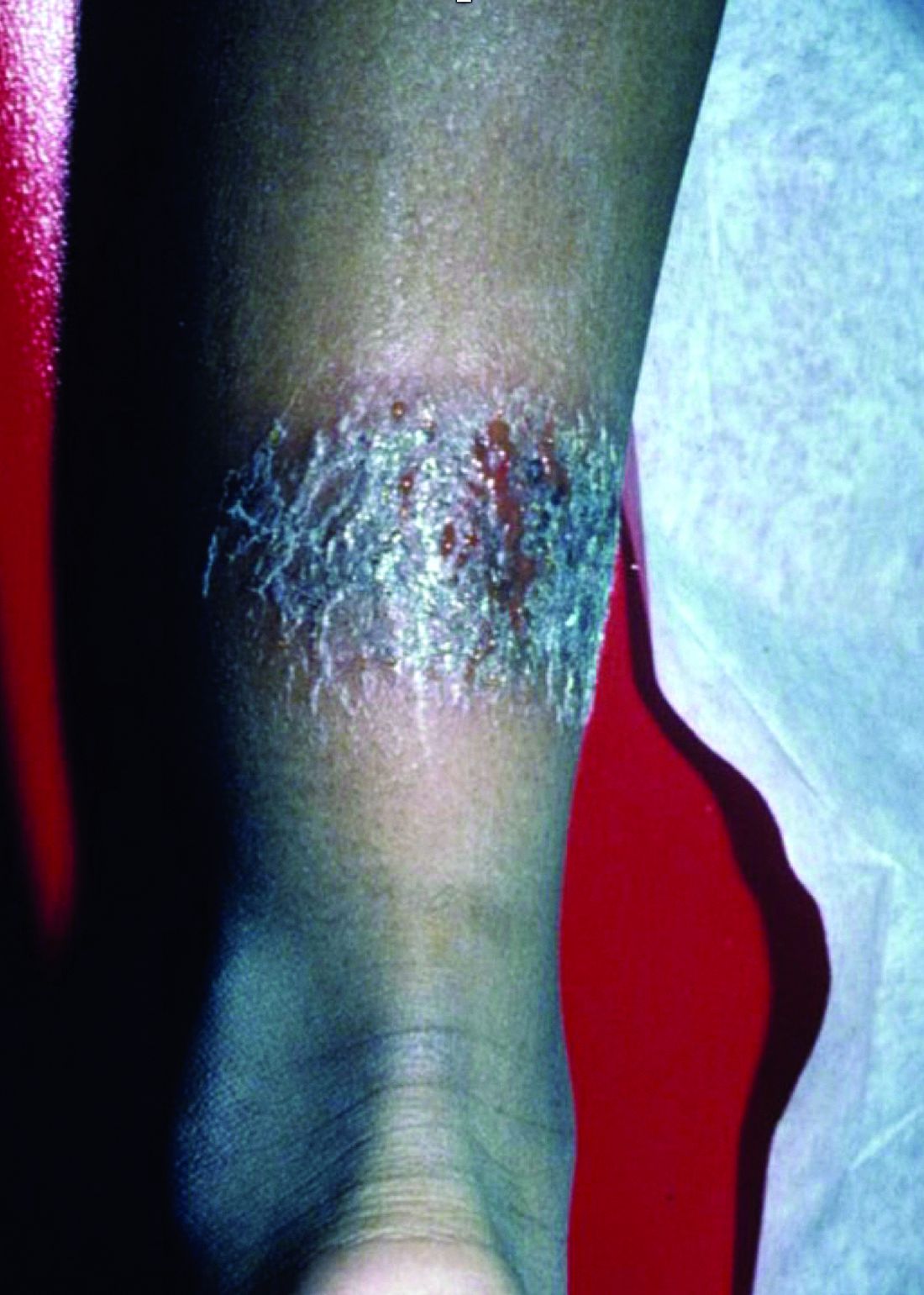

Violaceous papules on calf & foot

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

that usually presents on the distal lower extremities or feet as red to violaceous papules, patches, and plaques.

Clinically, lesions may look similar to Kaposi sarcoma (KS). It is considered to be a variant of stasis dermatitis or severe chronic venous stasis with a more exuberant vascular proliferation of preexisting vasculature. Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is thought that chronic edema, increased venous pressure, and tissue hypoxia may induce fibroblast and vascular proliferation.

It has also been described in association with vascular anomalies, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, and Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, and is caused by arteriovenous fistulae. Paralysis of lower extremities and amputation stumps are predisposing factors.

KS has four clinical variants: classic KS, African endemic KS, KS in immunocompromised patients, and AIDS-related epidemic KS. All types are caused by the human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). Violaceous lesions generally begin as macules and may progress to nodules or tumors.

Punch biopsies were performed in our patient. Histologically, thin-walled, dilated, capillary-like structures were present with a thin layer of surrounding pericytes with reactive fibrosis, hemorrhage, hemosiderin, and a scant chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The endothelial cells did not show atypia or mitotic activity. Endothelial cells were positive for CD31, CD34, and CD99. Pericytes and some of the endothelial cells were positive for actin and negative for D2-40, desmin, and HHV-8. In KS, vessels appear like slitlike or jagged spaces lined by spindled endothelial cells. Mild cytologic atypia is usually present. Endothelial cells are characteristically plump. A distinguishing feature in KS is the “promontory sign,” in which new vessels protrude into the vascular space. CD34 is usually negative and HHV-8 is positive.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali may improve when the underlying venous insufficiency is addressed with compression stockings, pumps, or vascular intervention. Laser ablation of individual lesions has been described in the literature. Dapsone, oral erythromycin, and topical corticosteroids have been reported as helpful in some patients.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Pruritic, pink to violaceous, scaly papules

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions was consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA).

The patient was diagnosed with PLEVA, also known as Mucha-Habermann disease. The true incidence of the condition is not known.

The typical presentation is an abrupt onset of pink to violaceous, scaly papules and plaques that later develop violaceous or necrotic centers, like the ones seen in our patient. The lesions more typically occur on the trunk and proximal extremities, but they may present in any other part of the body, rarely in the mucosa.1 Some patients can develop the febrile, more severe form of PLEVA called febrile, ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD), which potentially can be life threatening.

Patients with PLEVA can complain of pruritus or a burning sensation, and in some cases can have associated arthralgia and edema. The more severe form FUMHD is characterized by persistent high fevers with associated internal organ involvement such as cardiomyopathy, small vessel vasculitis, abdominal pain, arthritis, pneumonitis, and hematologic abnormalities.2 Mucosal involvement is a common finding in patients with FUMHD.

The pathogenesis of PLEVA is not very well understood. Some theories include a T-cell dyscrasia and an atypical immune response to an infection or vaccination.3,4

The differential diagnosis of PLEVA includes varicella, pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), disseminated herpes simplex infection, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Patients with varicella also present with lesions in different stages, similar to PLEVA, but the classic lesions are usually vesicular and described as dewdrops on a rose petal. The course of varicella is 1-2 weeks, compared with PLEVA where the lesions can be present for months to years.

Patients with PLC can have similar lesions to PLEVA, but the lesions rarely are necrotic. Some consider these two entities a spectrum of the same condition.5

LyP is a rare condition in children, and it is characterized by crops of pink papules and nodules that resolve within weeks. A skin biopsy may help distinguish between the two conditions because LyP lesions are characterized by atypical lymphocytes that are CD30 positive.

Children with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome present with papules and papulovesicles on the face, arms, buttocks, and legs, after an upper respiratory or GI infection. Sometimes the lesions may be hemorrhagic. Lesions resolve within weeks to months.

Hemorrhagic-crusted papules on a seborrheic and intertriginous distribution characterize Langerhans cell histiocytosis. These patients may present hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy – neither of which were present on our patient.

Children with mild PLEVA disease and who are not symptomatic may be followed without intervention. In those with more severe disease and who are symptomatic can be treated with tetracyclines such as minocycline or doxycycline or erythromycin for about 3 months.6,7 Phototherapy also is recommended as a first-line therapy. In cases that do not respond to oral antibiotics and light therapy, methotrexate can be an alternative.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;18(7):690-1.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991 Mar;8(1):51-7.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Dec;136(12):1483-6.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018 Sep;109(7):e6-10.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Mar;35(2):213-9.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Nov-Dec;29(6):719-24.

7. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15813.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions was consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA).

The patient was diagnosed with PLEVA, also known as Mucha-Habermann disease. The true incidence of the condition is not known.

The typical presentation is an abrupt onset of pink to violaceous, scaly papules and plaques that later develop violaceous or necrotic centers, like the ones seen in our patient. The lesions more typically occur on the trunk and proximal extremities, but they may present in any other part of the body, rarely in the mucosa.1 Some patients can develop the febrile, more severe form of PLEVA called febrile, ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD), which potentially can be life threatening.

Patients with PLEVA can complain of pruritus or a burning sensation, and in some cases can have associated arthralgia and edema. The more severe form FUMHD is characterized by persistent high fevers with associated internal organ involvement such as cardiomyopathy, small vessel vasculitis, abdominal pain, arthritis, pneumonitis, and hematologic abnormalities.2 Mucosal involvement is a common finding in patients with FUMHD.

The pathogenesis of PLEVA is not very well understood. Some theories include a T-cell dyscrasia and an atypical immune response to an infection or vaccination.3,4

The differential diagnosis of PLEVA includes varicella, pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), disseminated herpes simplex infection, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Patients with varicella also present with lesions in different stages, similar to PLEVA, but the classic lesions are usually vesicular and described as dewdrops on a rose petal. The course of varicella is 1-2 weeks, compared with PLEVA where the lesions can be present for months to years.

Patients with PLC can have similar lesions to PLEVA, but the lesions rarely are necrotic. Some consider these two entities a spectrum of the same condition.5

LyP is a rare condition in children, and it is characterized by crops of pink papules and nodules that resolve within weeks. A skin biopsy may help distinguish between the two conditions because LyP lesions are characterized by atypical lymphocytes that are CD30 positive.

Children with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome present with papules and papulovesicles on the face, arms, buttocks, and legs, after an upper respiratory or GI infection. Sometimes the lesions may be hemorrhagic. Lesions resolve within weeks to months.

Hemorrhagic-crusted papules on a seborrheic and intertriginous distribution characterize Langerhans cell histiocytosis. These patients may present hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy – neither of which were present on our patient.

Children with mild PLEVA disease and who are not symptomatic may be followed without intervention. In those with more severe disease and who are symptomatic can be treated with tetracyclines such as minocycline or doxycycline or erythromycin for about 3 months.6,7 Phototherapy also is recommended as a first-line therapy. In cases that do not respond to oral antibiotics and light therapy, methotrexate can be an alternative.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;18(7):690-1.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991 Mar;8(1):51-7.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Dec;136(12):1483-6.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018 Sep;109(7):e6-10.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Mar;35(2):213-9.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Nov-Dec;29(6):719-24.

7. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15813.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions was consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA).

The patient was diagnosed with PLEVA, also known as Mucha-Habermann disease. The true incidence of the condition is not known.

The typical presentation is an abrupt onset of pink to violaceous, scaly papules and plaques that later develop violaceous or necrotic centers, like the ones seen in our patient. The lesions more typically occur on the trunk and proximal extremities, but they may present in any other part of the body, rarely in the mucosa.1 Some patients can develop the febrile, more severe form of PLEVA called febrile, ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD), which potentially can be life threatening.

Patients with PLEVA can complain of pruritus or a burning sensation, and in some cases can have associated arthralgia and edema. The more severe form FUMHD is characterized by persistent high fevers with associated internal organ involvement such as cardiomyopathy, small vessel vasculitis, abdominal pain, arthritis, pneumonitis, and hematologic abnormalities.2 Mucosal involvement is a common finding in patients with FUMHD.

The pathogenesis of PLEVA is not very well understood. Some theories include a T-cell dyscrasia and an atypical immune response to an infection or vaccination.3,4

The differential diagnosis of PLEVA includes varicella, pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), disseminated herpes simplex infection, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Patients with varicella also present with lesions in different stages, similar to PLEVA, but the classic lesions are usually vesicular and described as dewdrops on a rose petal. The course of varicella is 1-2 weeks, compared with PLEVA where the lesions can be present for months to years.

Patients with PLC can have similar lesions to PLEVA, but the lesions rarely are necrotic. Some consider these two entities a spectrum of the same condition.5

LyP is a rare condition in children, and it is characterized by crops of pink papules and nodules that resolve within weeks. A skin biopsy may help distinguish between the two conditions because LyP lesions are characterized by atypical lymphocytes that are CD30 positive.

Children with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome present with papules and papulovesicles on the face, arms, buttocks, and legs, after an upper respiratory or GI infection. Sometimes the lesions may be hemorrhagic. Lesions resolve within weeks to months.

Hemorrhagic-crusted papules on a seborrheic and intertriginous distribution characterize Langerhans cell histiocytosis. These patients may present hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy – neither of which were present on our patient.

Children with mild PLEVA disease and who are not symptomatic may be followed without intervention. In those with more severe disease and who are symptomatic can be treated with tetracyclines such as minocycline or doxycycline or erythromycin for about 3 months.6,7 Phototherapy also is recommended as a first-line therapy. In cases that do not respond to oral antibiotics and light therapy, methotrexate can be an alternative.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;18(7):690-1.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991 Mar;8(1):51-7.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Dec;136(12):1483-6.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018 Sep;109(7):e6-10.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Mar;35(2):213-9.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Nov-Dec;29(6):719-24.

7. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15813.

A healthy 14-year-old female was referred urgently by her pediatrician to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash. The rash had been present for 4 weeks on her torso and proximal extremities, and had been spreading. She had been very itchy. She denied any fevers, chills, joint pain, oral or genital lesions.

She was visiting some family members in Washington State during the summer. The rash started 1 month after this visit.

The adolescent had been treated with acyclovir, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and intramuscular triamcinolone without improvement. She had been taking children's multivitamins occasionally. Her vaccinations were up-to-date. She denied any history of varicella or herpes infection. Her mom has a history of cold sores. The teen is not sexually active.

On physical examination, the girl was not in acute distress. Her vital signs were stable. She was not febrile. She had pink, scaly, and hyperpigmented papules and plaques, some of which were crusted with violaceous centers on the trunk and proximal extremities. There were no lesions on the mouth, palms, or soles. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Pneumonia with tender, dry, crusted lips

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Intense stinging and burning, followed by the development of skin lesions minutes after exposure to a plant

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Urticaria from stinging nettle

The stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is a plant that grows in the United States, Eurasia, Northern Africa, and some parts of South America. It is commonly found in patches along hiking trails and near streams. The leaves are green with a characteristic tapered tip and bear tiny spines or hairs. The spines contain substances such as histamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. Within seconds of contact with the stinging nettle, sharp stinging and burning will occur. Urticaria and pruritus may appear a few minutes later and may last up to 24 hours. The plant is eaten in some parts of the world and has been used as medicine.

The wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) is a relative of the stinging nettle that often grows in woodlands. Like the stinging nettle, the wood nettle leaves are covered with spines that sting when they come into contact with skin. However, the leaves are shorter and more oval shaped that the stinging nettle, and they lack the tapered tip that is characteristic for the stinging nettle. The reaction from the wood nettle is generally milder than that of the stinging nettle.

Plants can illicit different types of reactions in the skin: urticaria (immunologic and toxin mediated), irritant dermatitis (mechanical and chemical), phototoxic dermatitis (phytophotodermatitis), and allergic contact dermatitis. where anyone coming into contact with the hairs of the plant can be affected. Previous sensitization is not required. The reaction usually occurs immediately after exposure.

The allergic contact dermatitis seen with toxicodendron (poison ivy and poison sumac) appears 48 hours after exposure of a previously sensitized person to the plant. This type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction is known as cell-mediated hypersensitivity. Generally, no reaction is elicited upon the first exposure to the allergen. In fact, it may take years of exposure to allergens for someone to develop an allergic contact dermatitis.

The poison ivy plant can grow anywhere and is characteristically found in “leaves of three.” Skin reactions are often appear as linearly-arranged vesicles a few days after the exposure to the urushiol chemical in the sap of the plant. Poison sumac has red stems with 7-12 green, smooth leaves, and causes a similar skin reaction as poison ivy. It typically grows in wet areas.

Most stings are self-limited. Topical corticosteroid creams may be used if needed.

This case and photo were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology in Coraopolis, Pa., and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

A 2-month-old infant with a scalp rash that appeared after birth

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.